Chapter 27: The Pursuit to Madang

THE Australian operations along the Rai Coast and in the Finisterre Mountains in the early part of 1944 were being undertaken as a result of a policy directive for the summer of 1943-1944 issued by General Blamey on 23rd December. Blamey had warned that “the operational role of the Australian Military Forces engaged in forward operations in New Guinea will be taken over by USA forces in accordance with plans now being prepared. Aggressive operations will be continued and reliefs necessary to maintain the initiative will be made by GOC New Guinea Force until Commander, USA Forces, takes over responsibility.” The reliefs would be effected gradually, first on the Huon Peninsula and second in the Ramu Valley. “As relieved, and subject to operational or emergency requirements,” the 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions would be allocated to I Australian Corps and would return to the mainland for training and rehabilitation. Three militia divisions – 3rd, 5th and 11th – would be allocated to II Australian Corps for garrison duties, training and rehabilitation in New Guinea and on the mainland. The already depleted III Australian Corps in Western Australia would be further reduced by one infantry brigade which would be transferred to the 3rd. Division at Atherton. Blamey instructed that movement of units to the mainland should begin immediately “in accordance with the principle of earliest relief for longest service in New Guinea”, and that “the force remaining at the conclusion of the relief will be an Army Corps of approximately two full jungle divisions plus base troops required for maintenance”.

Thus the role of the Australian Army in 1944 would be small in comparison with the one it had played in the previous two years when it had carried the main burden of the fight against the Japanese in the South-West Pacific.

At this stage, on 22nd January 1944, the War Cabinet decided to present to General MacArthur a revised statement of the combat forces to be assigned to him – the first such statement since the original one of 18th April 1942. The new statement set out the forces assigned in greater detail than hitherto, specifying individual brigades; as far as the army was concerned, it again gave control of all mobile operational formations to MacArthur, but provided that future assignments should be specifically made by the Government. Thus, if a new brigade or division was formed it would be necessary to assign it individually to MacArthur.

In New Guinea the main body of the retreating Japanese divisions was marching westward along the coastal route, and a smaller column consisting principally of the III/238th Battalion was using an exhausting inland route from Nambariwa to Nokopo. From Gali 2 the route would lead round the American beach-head at Saidor through Nokopo and

Tarikngan. Here, as mentioned, was a covering force of about 2,000 men under Major-General Nakai, comprising the III/239th Battalion and five companies of the 78th Regiment.

For the Rai Coast advance Major-General Ramsay of the 5th Division would have in the forward area only the 8th Brigade (4th, 30th and 35th Battalions); the 4th and 29th Brigades were to remain in rear areas. The commander of the 8th Brigade, Brigadier Cameron, was the only officer now commanding a brigade who had not served in the Middle East. He had returned from the war of 1914-18 as an infantry lieutenant, and had led the 8th Brigade since May 1940.

Ramsay’s intention was to “advance to make contact with the US forces at Saidor”. He estimated that an enemy force of not more than 3,000 troops was in the area between Sio and Saidor, that their morale and health were low, and that organised resistance was unlikely. Behind his statement that “US forces have established a bridgehead at Saidor extending approx five miles in the direction of Sio, but are not expected to extend further in this direction”, there may have been a suggestion that the 32nd American Division was losing a golden opportunity by letting the retreating 20th and 51st Japanese Divisions bypass them. And on 17th February General Morshead wrote in a letter to Blamey that the Saidor force appeared not to have made “any appreciable effort” to cut off the retreating Japanese.

Besides the 8th Brigade the main units taking part in the advance were the veteran company of Papuans, the 23rd Battery (short 25-pounders) from the 2/12th Field Regiment, the 2/13th and 8th Field Companies, and a detachment of the 2/8th Field Ambulance. Because of the difficulties of supply not more than one battalion group would be used forward of Kelanoa and the remainder of the brigade would occupy “healthy areas” at Kelanoa. The maximum use would be made of the Papuans to precede the forward battalion, and, as subsequent maintenance of the striking force would depend on the selection of suitable beaches, land reconnaissance parties from the American 2nd Engineer Special Brigade would accompany it.

On 19th January Cameron’s headquarters and the 4th Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Crosky1) began to arrive at Sio and Nambariwa. In the 4th, as in many more-experienced units before it, there was a certain amount of nervousness known colloquially as “itchy finger” on the first few nights. On the night of the 21st–22nd January the forward platoon imagined that they saw some Japanese and opened fire. The “Japanese” were their own men, two of whom were killed and two wounded. The raw 8th Brigade, however, had the benefit of tlae skill and experience of the Papuan company. The Papuans were in their element as hunters and were busy looking for scattered bands of Japanese. They would have been disappointed had they been recalled (as was intended at one stage) and, as events turned out, two companies of Papuans could probably have

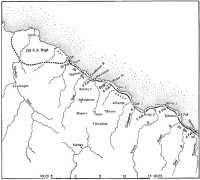

The 8th Brigade’s pursuit along the Rai Coast

advanced to Saidor quicker and with less effort than any brigade of Australians.

On the 22nd a native reported that there were about seven Japanese in the hills South-west of Sio Mission. A small patrol of Papuans, under Corporal Bengari, whose reputation was similar to that of the best of Gurkhas, immediately set out and arrived on the outskirts of the village of Lembangando on the night of the 24th. He sent forward a local native who said on his return that another 22 Japanese had now arrived. Next morning Bengari and his five companions ambushed the enemy force and killed every one without the Japanese firing a shot. Another Papuan patrol to Vincke Point found 20 dead Japanese on the track and killed one other on their return journey to Sio. Thus, even before the advance began, the Papuans had cleared the way as far as the end of the first bound planned by Cameron; he had ordered that the 4th Battalion, preceded by the Papuans, would begin on 25th January a series of daily bounds, designed to take them to the Timbe River in six days. It was planned that the 4th Battalion would advance to Malasanga, the 30th thence to Gali, and the 35th would then take over and link with the Americans in Saidor. General Berryman signalled to Ramsay on the 25th: “Consider brigade rather over cautious but do not propose to push them yet.”2

It would be difficult to find sheltered beach-heads because the northwest monsoon would blow until the middle of February, causing sudden flooding of the rivers and rough seas which would limit barge landing points to areas protected from the North-west. The terrain of the Rai Coast

consisted of a coastal belt whose width varied from about a mile to almost nothing, cut by many rivers and swamps. The whole operation would obviously be governed by supplies moved by sea. The Australians would thus, once again, depend upon their well-tried friends, the American boatmen of the 532nd EBSR, of whom only one company remained with them.

Because of the terrain the advance could be at most on a company front, probably mainly on a platoon front with Papuans scouting ahead. Behind these forward troops was an imposing array of headquarters: behind the one leading battalion a brigade commander, behind him a divisional commander, behind him a corps commander, and behind him a force commander. Two of these might well have been removed from the chain of command and the task allotted to a brigade group directly under the command of New Guinea Force – an arrangement that was, in effect, adopted later with regard to this very brigade.

The advance began on the 25th when the Papuans in the van arrived at the Kwama River soon after midday. Near a possible ford was the heap of dead bodies previously discovered. As they tried to cross the river a Japanese hiding among these bodies began to fire at them and was dealt with. When the battalion arrived the river was neck-deep and running at about 10 knots, and although one platoon crossed on an improvised bridge the river then washed the bridge away and further attempts to cross were unsuccessful.

The airmen of No. 4 Squadron, flying low in their Boomerangs and Wirraways, were scouring the area ahead of the advance so thoroughly that they often counted the number of corpses and reported the expressions on the faces of retreating Japanese. A typical example of the work of the pilots during the pursuit is contained in a reconnaissance report of 26th January. Skimming over the Kwama the pilots waved to the Australians below and were answered. The information from their aerial reconnaissance gave the Australians, when they finally crossed the river, almost an assurance that there would be no opposition and that they could press on quickly to make up for lost time. The airmen saw no Japanese although they did see a group of natives at a river-mouth wearing red lap-laps. They reported empty villages, five parachutes hanging in trees – an indication that the Japanese may have tried, in desperation, to supply their retreating army from the air – “very slight recent usage” along the main tracks, possibly because of the heavy rain, several clearings where Japanese might have been about to set up camp and then decided otherwise, and caves in the area from Kiari to Sigawa where the defeated 51st Japanese Division had come to rest after escaping from Lae and Salamaua.

The battalion crossed the falling Kwama on the afternoon of the 26th. Next day it moved rapidly to the Asiwa River, and reached the Kiari area on the 28th, and on the 29th Singor. Each day at this stage the Papuans were killing 12 to 15 Japanese, and finding similar numbers of corpses. Supply difficulties caused delay, and the advance was slowed because of

corps and divisional instructions that artillery support was to be immediately available. This necessitated the permanent allotment of barges to the artillery and so far there were not enough barges to supply even the infantry. The engineers were having difficulty in making river crossings, partly because it was so hard to move forward the engineering equipment required. For instance, when the Kwama’s bridge was washed away the troops beyond the river, but well behind the leading barge point, found supplies very short and there were other difficulties along the supply route: the increasing length of signal communications, the uncertainty of wireless communications, and the marshy country west of Kiari which prevented the use of motor transport and placed an additional strain on the barges.

The fifth bound – Malasanga – was reached in the afternoon of the 30th, and on the 31st the Papuans and Australians advanced to Crossing-town. The men were now on three-quarter rations. More troops were concentrating in the Singor area on the 31st, thus increasing the ration shortage. Among the arrivals were the 30th Battalion, a section of the 2/4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment and the 64th Battery of the 2/14th Field Regiment (Lieut-Colonel Hone3), with its regimental headquarters,4 which arrived to relieve the 23rd Battery of the 2/12th Field Regiment.

After a confused start the 4th Battalion had reached its objective only one day behind schedule without, however, being able to catch the retreating enemy. The advance obviously could not be continued until rations became available, and early on 1st February Cameron cancelled the advance for that day. Along the coast behind the forward troops floods had washed away bridges over the Mongo, Asiwa and Romba Rivers. Jeeps and bulldozers were therefore isolated and their crews, like the forward troops, were almost without rations. The Papuans, having been without proper food for the last three days, camped and waited. Rough seas, flooded rivers, broken bridges and lack of supplies continued to delay the advance until 3rd February when Lieut-Colonel Parry-Okeden’s 30th Battalion set off from Singor to take over from the 4th Battalion at Crossingtown. Meanwhile the Papuans reached Nemau. Supplies were dropped from the air on the 4th and the recovery was 82 per cent.

The 30th Battalion on the 4th reached Nemau and on the 5th Butubutu, where the next supply beach was established. Increasing numbers of dead were now being found along the route and the inland trails-52 on the 4th. On the 5th came orders that all commanders must make every endeavour to capture prisoners, and with this in view Cameron called off the Papuans from leading the advance and sent the leading Papuan platoon to reconnoitre the inland trails while the infantry led the advance on the right. Final arrangements were made on the 5th for

The 8th Brigade’s advance to Saidor

linking the Americans and Australians. Major Watch of Ramsay’s staff, with a section from the 30th Battalion, was to move to Saidor by barge, go to the American outpost at Yagomai, cross the Yaut River on the 10th, and meet the 30th Battalion advancing west. Communications between Watch’s section and the forward elements of the 30th Battalion would be maintained by wireless or alternatively by Very lights. No. 4 Squadron would report the positions of the advancing Australians.

The beginning of the next bound on 6th February was temporarily held up because of the difficulty of moving the artillery forward. Finally Ramsay agreed that the advance should continue without it, and the 30th Battalion marched along a very muddy track and reached Roinji 1. There was no contact with the fleeing enemy who were then estimated to be between 24 and 48 hours ahead. The pursuers began to catch up on the 7th when the 30th Battalion advanced to Roinji 2 along a track littered with 60 enemy dead. In the afternoon the Papuans, now carrying two days’ rations, resumed the lead and reached Gali 1. Twenty-four Japanese were killed that day by the 30th Battalion and the Papuans, and three prisoners were taken.

Watch, on the 6th, signalled Ramsay about the locations of the forward American posts and also that an American patrol to Yagomai had captured two prisoners on the east bank of the Yaut River on that day. Late on the 7th he signalled that one of the prisoners taken on the Yaut River said that there were no Japanese between Gali and Yagomai.

On 8th February, the first opposition from the Japanese rearguard was met near Weber Point. For the first time in the advance therefore the leading platoon put on a formal attack, killing five Japanese and having two men wounded. During this day 53 Japanese were killed in a running fight and four were taken prisoner. By nightfall on the 9th the leading company was 2,000 yards west of Malalamai and 3,500 yards from the American outpost at Yagomai. Sixty-one Japanese were killed and 9 prisoners taken in the day.

At 10.30 a.m. on 10th February the leading platoon met the section from the 30th Battalion which had been sent into the Saidor area and which had been joined by two Americans at Yagomai. Soon after this junction Cameron and his brigade major, Gregory,5 arrived at Yagomai by gunboat and awaited the arrival of the remainder of the 30th. By the end of the day one company of the 30th was at Seure with patrols already among the Americans in the Sel area.6

Cameron was now instructed to mop up Japanese forces South-east of the Yaut River. It was decided that the 5th Division would not operate west of the Yaut, which would be the boundary with the Saidor force, but would clear first the Tapen area and then the Nokopo area. The task of patrolling these areas was given to Lieut-Colonel Rae’s7 35th Battalion which would be meeting the enemy for the first time. The country over which the 35th Battalion was to operate was extremely rugged and little was known of it. The battalion arrived in barges which back-loaded the 30th Battalion to Kelanoa. The advance began on the 14th when Captain Farmer’s8 company, accompanied by a section of Papuans, moved off from Gali 2 towards Ruange. It was deserted but patrols looking for water killed three Japanese, and between Bwana and Ruange next day the Papuans killed 31. A column under Major Delbridge9 which set off on the 15th towards Kufuku found 11 dead Japanese and the Papuans killed 9. Next day Delbridge reached Kufuku, counting 30 dead on the way.

In this way the advance continued along both the main tracks. On the outskirts of Gabutamon, on the 18th, the leading platoon found that it was occupied and immediately attacked, killing 40 Japanese and finding at least as many dead in the village. Sneaking up to the outskirts of Tapen in the early afternoon of the 18th Farmer discovered that the enemy had a force of at least 100 there. He decided to gain full advantage of surprise and concentrated fire by sending in first those of his men who had automatic weapons, followed by riflemen, while the Papuans moved round the flanks to mop up in the gardens. With a savage burst of automatic fire the Australians charged Tapen. For the first time the 35th Battalion came under fire. One section was pinned down at first by this enemy fire but, for the loss of one man wounded, Farmer’s men killed 52 Japanese. The Papuans on the flanks killed another 51 Japanese, Corporal Bengari and two other Papuans accounting for 43 of them. There were still Japanese round the Tapen area on the 19th when the Papuans killed 39 more, mainly escapers from the previous day’s engagement.10

A patrol sent out from Gabutamon on the 20th to investigate the track towards Moam and Tapen, was often forced to crawl on hands and knees along the muddy, slippery tracks winding along the ridges. About 1,500 yards south of Gabutamon the patrol reached the bottom of a 100-foot chasm along which the track wound for a short distance before going straight up the slope. Broken rope ladders, swinging from the top of the cliff, showed how the Japanese had climbed out of the chasm – or tried to. In a macabre heap beneath the swaying ropes were the decomposing and smashed bodies of about 80 Japanese who had apparently been so weak that they could not haul themselves up.

By the 21st Farmer had a fair indication that Wandiluk would be occupied and was ordered to attack it. The track was now the worst encountered. The mud and water were frequently waist-deep, and the track was very narrow. Farmer considered that his estimate of 80 dead along the track was conservative. Most of these had probably died of sickness, exhaustion or starvation, but cold may have killed some for, in these mountains, the nights were intensely cold and there were heavy frosts. In Wandiluk 40 Japanese were killed, not counting 7 wounded who staggered away and jumped to their death into a steep gorge at the lower end of the village, and in the surrounding gardens 10 more were killed.

From the 22nd the pursuit was largely carried on by the Papuans. Other than patrolling by the Papuans farther south into the pitiless mountains towards Nokopo, the 8th Brigade had now really completed its task. From 20th January until the end of February, the brigade had killed 734 Japanese, had found 1,793 dead and taken 48 prisoners; the Australians and Papuans had lost 3 killed and 5 wounded. Such casualties, added to those inflicted on the 51st Division in the Salamaua and Lae

campaigns and in its subsequent retreat over the mountains, and on the 20th Division in the Huon Peninsula campaign, gave a fair indication of the plight of the XVIH Japanese Army, which now had only two unscathed regiments of its original nine.

In a letter to Blamey on 21st March Berryman wrote: “About 8,000 semi-starved, ill equipped and dispirited Japanese bypassed Saidor. It was disappointing that the fruits of victory were not fully reaped, and that once again the remnants of 51st Division escaped our clutches.” By 26th February American observers overlooking Tarikngan, south of Saidor, reported that they had counted 3,469 Japanese passing through there in small disorganised groups. The number which actually did pass through must have been far greater.

The chase was almost over when Berryman and Ramsay visited Cameron on 26th February. The 532nd EBSR was to concentrate in the Finschhafen area by 1st March for other operations with the Americans and only a few American barges would be available to the 8th Brigade thereafter. The plan was now to withdraw to the Kelanoa area in preparation for a move farther south to Kiligia, to concentrate the Papuans at Weber Point, and send forward a small patrol to Nokopo. The men of the 8th Brigade and the Papuan Battalion could not leave the wretched area quickly enough. At the beginning of March the brigade began to concentrate round Kiligia, and early in March the Papuans were withdrawn to a camp north of the Song River except for small detachments which patrolled the Rai Coast at intervals.

On 18th January Vasey had received a note from Morshead’s headquarters in Port Moresby giving notice of the forthcoming relief of the 7th Division’s headquarters by the 11th Division’s. Vasey flew to Port Moresby on the 26th to discuss the relief. He had already decided to change over his two brigades and give the 15th the task of patrolling forward from Kankiryo Saddle, but sickness prevented him from supervising the change-over.

From the 9th to 21st February the relief took place. The 58th/59th Battalion relieved the 2/10th in the right-hand sector from 4100 through Crater Hill and Kankiryo Saddle to Cam’s Hill, with the task of patrolling the area east of Cam’s Hill, the headwaters of the Mosa River, and forward along the upper Mindjim River Valley to Paipa 2. The 57th/60th relieved the 2/9th on the left with positions on the 4100 Feature, the Protheros and Shaggy Ridge, and the task of patrolling forward from Canning’s Saddle along the high ground west of the Mindjim. The 24th Battalion relieved the 2/12th in reserve.

The country facing the Australians beyond Kankiryo Saddle was formidable. The jagged Finisterre mountains tumbled away towards the sea, about 20 miles away as the crow flies but treble that distance as the soldier plods, and through the mountains the Japanese motor road was reported to follow the valley of the Mindjim down to the coast at Bogadjim. “The country in the Finisterre Ranges is rugged, steep, precipitous

and covered with dense rain forest. It rains heavily almost every day thus making living conditions uncomfortable. By day it is hot, by night three blankets are necessary. There is, therefore, a constant battle with mud, slush, rain and cold. To allow freedom of movement over this mud it was necessary to corduroy every track in the area.”11 The actual Kankiryo Saddle was an ideal holding position as approaches from the north, east and west were precipitous. It formed a link between the high ground of Crater Hill and the 4100 Feature on the right or east, and the Protheros on the left or west; the whole massive feature was shaped like an H with Kankiryo Saddle the crosspiece.

On the right flank Lieutenant Brewster12 with a small patrol from the 58th/59th investigated the valley of the Mosa River as far as Amuson, and returned after four days, on 20th February, to report the area clear. In the central area a patrol from the 57th/60th on the 23rd brushed with an enemy patrol near Saipa 2, which the guns of the 4th Field Regiment then bombarded. On the 28th a patrol from the 57th/60th, led by Lieutenant Besier,13 attacked Saipa 2 three times with supporting artillery fire, but all attempts to enter the village were repulsed.

When there seemed to be no sign of movement on the right flank in the Kabenau Valley, Brigadier Hammer on 26th February instructed Major Newman, temporarily in command of the 58th/59th, to establish a company patrol base at Amuson and send out a “platoon recce patrol” to the coast in the Mindjim-Melamu area. Besides gathering information about the enemy and the country the patrol was to establish observation posts overlooking Astrolabe Bay; these would operate from a forward base at Nangapo. Captain Cuthbertson14 was given the task of establishing these bases which he did early in March. Hammer also secured permission to send the whole of the 57th/60th into the Paipa area in preparation for an attack on Saipa 2.

While this was going on two battalions of the 32nd American Division from Saidor landed on 5th March at Yalau Plantation between Saidor and Bogadjim. It was a full-scale landing with 54 craft unloading 1,348 troops in the first nine waves, but there was very little opposition and the landing was made without incident. Patrolling east and west from Yalau the Americans killed a few Japanese and found many dead. By the 9th they reached the Bau Plantation where they brushed with a small party of Japanese. Attempts to cross the Kambara River during the next few days were unsuccessful because of the opposition of a band of about 40 Japanese. On the 11th Hammer was instructed to send a patrol to Yangalum four days later to join an American patrol believed to be moving forward from the Bau Plantation. To reach Yangalum the Americans would have to cross two large rivers, the Kambara and the Guabe.

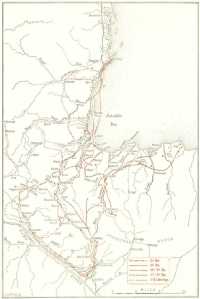

Across the Finisterres to Madang

In Vasey’s absence Chilton commanded the division. Cummings, temporarily commanding the 18th Brigade, now determined to straighten his line by having the 2/12th Battalion capture Ward’s Village on the left to coincide with the 57th/60th’s attack on Saipa 2. When the 2/12th Battalion found Ward’s Village unoccupied on 12th March Chilton decided that the 15th Brigade could move a battalion along the Mindjim Valley to Yokopi without becoming involved in a major conflict. By 9.30 on the night of the 12th the 57th/60th was moving forward, and next day found Saipa 2 abandoned. There was plenty of evidence of good shooting by the artillery, including Major Stevenson’s15 2nd Mountain Battery, now in the Cameron’s Knoll area.

By the 14th the 57th/60th Battalion was concentrated at Yokopi, where the Japanese road began. It was well formed, with a firm red-gravel surface. To achieve this swift advance the battalion moved by night and, during the day, stores, supplies, and ammunition were carried up and signal line was laid. The wisdom of a decision by Hammer to maintain seven days’ reserve at Kankiryo Saddle was now apparent for, without it, the battalion could not have advanced 17 miles without native carriers. On the afternoon of the 14th the leading platoon regained contact with the Japanese just north of Daumoina at the junction of the Mindjim with a stream flowing in from the west and also with the suspected mule track shown on the map. The Japanese were occupying the high ground overlooking this junction and could easily command the approaches along the road and the river. When leading his platoon straight along the road towards the Japanese Lieutenant Sinclair16 was killed. Rather than batter at this formidable position Hammer ordered Colonel Marston to reorganise round Yokopi, keep contact with the enemy and build up reserves.

The Australians were now based in a wide semi-circle round Bogadjim. On 16th March Chilton redefined the division’s role “in the light of the present situation”. While the 18th Brigade was to watch the 15th Brigade’s immediate left flank from the high ground between the lower Evapia and Mene Rivers, and the commando troop at Faita17 the far left flank, the 15th Brigade would garrison Kankiryo Saddle, keep contact with the enemy along the Bogadjim Road and patrol along the Kabenau River towards Astrolabe Bay to join the Americans. Finally, the 15th Brigade would “provide a firm base for patrolling, by employing at the discretion of the commander, a force not exceeding one battalion forward of Kankiryo up to and inclusive of Yokopi”. The order was splendidly ambiguous as far as the local commanders were concerned, and managed to overcome the ban placed by higher authority on any advance across the Finisterres to the coast: Hammer could not go beyond Yokopi but, at the same time, he was to maintain contact with the enemy along the Bogadjim Road – and they were already farther back than Yokopi.

The country between the leading company of the 57th/60th and the Japanese rearguard at the mule track junction was very rough and heavily timbered. About 170 of the 500 native carriers available had been allotted to the 58th/59th Battalion in the Nangapo area near the coast, and as the remainder were required to maintain the lines of communication to Kankiryo Saddle, it was necessary for the men of the 57th/60th, other than those in the leading company who were patrolling, to help the 24th Battalion to carry supplies forward. Hammer now decided that, before he could resume the advance, the supply route from the Saddle to the 57th/60th Battalion must be developed. Thus the sappers of the 15th Field Company were given the task of building Saipa, Yokopi and Daumoina into staging areas. They corduroyed the track forward from the Saddle to Saipa 2 and began another jeep track from Guy’s Post to Mainstream designed to shorten the native carry to the Saddle and thus enable the natives to carry along the route twice daily instead of once.

For almost a fortnight the patrols of the 57th/60th made little impression on the Japanese rearguard. The 3800 Feature, which overlooked the Australian positions at Yokopi and Daumoina, seemed to be the main Japanese position and here they hung on. Hammer anticipated, however, that the constant patrolling and bombardment would have its effect, and, on the 27th, ordered the 57th/60th to patrol vigorously “as it is thought that the enemy has now withdrawn”. He was right; when patrols reached the mule track junction on the 28th they found that the enemy had gone. It began to seem that the enemy might now be about to withdraw from the Finisterres after their long and determined stand. The two broken Japanese divisions were now no longer in immediate danger of being caught along the Rai Coast or trapped by an advance across the Finisterres.

Hammer now ordered Marston to clap on all possible speed and chase the enemy. He believed that the next line of resistance would be at Yaula and he wished to get there before the Japanese could dig in. The advance was resumed and by 4 p.m. on the 30th contact was regained when the leading troops came under fire from a bridge (No. 22) over the Kofebi and from points on the road where it wound steeply up from the river towards Yaula, four hours march away. Major Connell,18 commanding the leading company, decided to cross the Kofebi, bypassing the next two bridges (Nos. 22 and 21A), attack the Japanese from the rear and then press on to Yaula. A small party under Lieutenant Maddison19 was left to protect the native carriers. The bypassing was successful and Lieutenant Berman’s20 platoon continued towards Yaula while the remainder of the company proceeded to clear the road behind. At the nearest bridge (21A), however, these came under heavy fire and four men were hit. Maddison’s group then came under fire from the Kofebi bridge and from a gun in

Yaula, with the result that the carriers went bush. One gun of the 2nd Mountain Battery, which had been dragged forward to Daumoina, fired back into Yaula and Kwato. It was now dark. At 7.45 the line between company and battalion was cut. The Japanese, pinched between Connell and Maddison, began to make off to Yaula into which the solitary Australian mountain gun fired all night.

At dusk Berman’s platoon had been within 600 yards of Yaula with Lieutenant Passlow’s21 400 yards behind and the third platoon and company headquarters a corresponding distance farther back. After dark Berman’s platoon was strongly counter-attacked. His communications severed, Berman nevertheless hung on although he knew nothing of what was happening in the rear. Passlow, however, moved his platoon up to within 200 yards of the forward platoon and himself crept forward to discuss the attack with Berman. While he was there another party of Japanese attacked his platoon. Throughout the night the Japanese continued their attacks but were driven back with probably about 40 casualties. With communications severed and with no rations, Berman and Passlow decided to withdraw intact to Mabelebu, which they did before the night was over. It later appeared that the Japanese had not planned a counter-attack but had merely been withdrawing from the flanks of the advance. Having reached the road where it was occupied by the two leading platoons, they had decided to fight their way out and had done so, with heavy casualties to themselves.

On 1st April the leading company took up a defensive position in the Mabelebu area. Marston, whose headquarters were also at Mabelebu, brought a second company forward. Patrols probed forward during the next few days.

Meanwhile patrols from the 2/2nd Commando Squadron had been harrying the Japanese from the left flank. Captain Nisbet led out the largest patrol (a troop plus a section) yet sent out by the squadron in over nine months of continuous patrolling. By 17th March a patrol base was established at Jappa, and next day about eight Japanese coming from the North-east towards Jappa walked into one of Nisbet’s booby-traps and several were hit. On the 19th and again on the 22nd the patrol met opposition from enemy parties along the track towards Oromuge.22 Farther west Lieutenant Doig’s patrols from Faita were scouring the western area round Topopo and Aminik and skirmishing with enemy outposts. Lieutenant Adams’ patrol through Kesa on the 22nd found the general Mataloi area abandoned, but discovered a strongly held position on the 2900 Feature behind Mataloi 1. After making half a dozen attempts in the next few days to get into this position the patrol withdrew. The enemy could be found nowhere else in this area. On 30th March 12 Bostons bombed and strafed the position and, after the raid, a patrol reported that Mataloi 1 was empty.

The 2/2nd Squadron exploited this situation rapidly. The 57th/60th Battalion was on its way north, towards Yaula, when a squadron patrol led by Lieutenant Fox23 set out North-east from Mataloi 1 towards the same objective. On the morning of 4th April, Fox’s patrol entered Yaula, and soon the vanguard of the 57th/60th joined him.

Thus the evacuation of Yaula by the Japanese was hurried not only by the pressure of the 57th/60th Battalion along the main road, but by the patrolling of the 2/2nd Squadron on the left flank (the 2/6th had now left for home). Yaula was occupied by the 57th/60th and one company immediately took over the advance, reaching Kwato late that night.

Along the Bogadjim Road, which wound its way over the range, often forming a ledge with a drop of 300 feet or so on one side, were signs of a hasty Japanese withdrawal. Thirty-seven 3-ton trucks, one 10-horsepower sedan, 14 jungle carts, one rotary engine, one 75-mm mountain gun, 3 heavy machine-guns, 4 light machine-guns, 3 mortars, 3 flame-throwers and much miscellaneous engineer and ordnance stores were captured in the rapid advance of the battalion. The Yaula area had undoubtedly been an important Japanese stores depot for it was honeycombed with tracks showing evidence of heavy use. On the 5th the leading company reached Aiyau and patrols set out towards the Bogadjim Plantation.

On the right flank the 58th/59th in the valley of the Kabenau had been patrolling from Nangapo. Major Newman was now mainly interested in linking up with the American forces from Saidor who were presumably patrolling west towards the valley of the Kabenau. The rendezvous was fixed at Arawum but a patrol under Lieutenant Brewster waited there from the 16th to the 18th March without seeing any signs of the Americans. He was therefore ordered, two days later, to take sufficient rations and patrol from Yangalum to Kul 2 where the Americans were believed to be.

An accidental meeting had already taken place between the patrols of the two Allies. An American reconnaissance patrol was being towed in a rubber boat by a PT boat with the object of landing at Male and seeing if the Japanese were at Bogadjim. Off Garagassi Point the tow rope broke and the Americans rowed to shore in their rubber boat which they deflated and hid in the bush near Melamu. Moving inland for about a mile they turned west and nearing the Kaliko Track met Lieutenant Norrie’s24 patrol of the 58th/59th Battalion and accompanied the Australians to Barum, where the Americans were given supplies and a guide; moving via Wenga, they reached Jamjam on the 18th and found no signs of the enemy. On this day at noon about 30 Japanese with three machine-guns and a mortar attacked Norrie’s position at Barum. The situation would have been serious had it not been for Sergeant Matheson25 and

his two men who had remained behind at Kaliko and managed to bear the first brunt of the attack and warn those at Barum. The Australians were forced to withdraw to a feature just north of Nangapo where natives came to them and told them that four of the attacking enemy had been killed and there were some stretcher cases. On the 19th Boomerangs strafed Barum and reported that it was empty, a fact which was confirmed at 2 p.m. by a small patrol from Nangapo.

The Americans moved on the 20th to Yangalum and next day set out for Kul 2, along almost exactly the same route as that taken by Brewster, who had departed on 20th March. Brewster reached Kul 2 on 21st March where he joined the Americans from Saidor and remained with them until the 26th. In this period he went to Saidor where he met Major-General William H. Gill, the commander of the 32nd American Division, gave him information about the area east of the Kabenau River and learnt of the American intentions and dispositions. Brewster then returned to Yangalum having carried out an important and lengthy linking patrol-35 miles each way.

As patrolling in the valley of the Kabenau forward from Nangapo was so strenuous, Lieutenant Fraser’s26 company took over from Cuthbertson’s on 22nd March.

Now began a game of hide and seek which lasted from 22 Mar until 11 Apr 44 (wrote Hammer in his report). It became apparent that the Jap force in the Melamu–Bonggu area was a flank protection to his main delaying force in the Mindjim Valley. Thus, when 58/59 Aust Inf Bn appeared in strength patrolling in that area, the Jap was not sure of our intention. He therefore patrolled vigorously and widely to discover our intentions. 58/59 Aust Inf Bn on the other hand avoided contact as their task was purely reconnaissance.

Several patrols just missed one another in the Wenga, Barum, Damun, Rereo and Redu areas. There were also several clashes. For instance, on 26th March, reports from local natives and police boys indicated that the Japanese were again approaching Barum, which had become the main trouble area, from the direction of Damun just to the north. Both sides engaged one another with fire, particularly mortar bombs, but the brush was a cursory one with neither side gaining any advantage. Exchange of fire and a few sporadic attacks by the Japanese continued for about five hours from 5 p.m. While Corporal Tremellen,27 in the leading section, was moving among his weapon-pits, with a Bren gun in his left hand and two magazines in his right, he was attacked but, not being able to bring his Bren into action, he bashed the Japanese over the head with the Bren magazines. This Japanese thus had the distinction of probably being the only one to be killed by the Bren magazine rather than what was inside it.

For the remainder of the month Fraser patrolled towards the coast and the Mindjim Valley. In the Barum area there were almost daily skirmishes

but by the end of the month the Japanese withdrew north. On 1st April the luluai of Male sent a native to Barum to report that, in the valley of the Kier River, he had met a Japanese patrol which asked to be shown the track to Barum. The luluai had replied that the only track to Barum was from Kaliko on the coast. The Japanese had therefore returned north along the river. At 2 p.m. Lieutenant Forster28 led out a patrol from Barum towards Kaliko but, three-quarters of an hour along the track, they ran into an ambush in which Forster and three men were killed, three were wounded and several weapons were lost.

Patrols by the 58th/59th Battalion on the right flank as well as the 2/2nd Commando Squadron on the left undoubtedly worried the enemy and helped to speed his withdrawal before the 57th/60th Battalion along the Bogadjim Road. By 4th April when Yaula was occupied the Australians were pointing like an arrow-head at Bogadjim; the point was the 57th/60th and the sides the 58th/59th Battalion and the 2/2nd Commando Squadron.

General Morshead had decided that it was time to rest the 7th Divisional Headquarters. Major-General A. J. Boase and his 11th Divisional Headquarters therefore on 8th April assumed responsibility for all units in the Ramu Valley and the Finisterres.29

Morshead was now sure that there was no need to maintain more than one brigade in the area, and suggested on 9th April that it would be possible to withdraw the 18th Brigade, yet not bring the 6th Brigade forward to relieve it as he had intended in February. On the same day he wrote to Brisbane seeking further definition of his responsibility in regard to the Bogadjim area. Blamey had already in February reminded Morshead that the 7th Division’s tasks remained as defined in the New Guinea Force instruction of 3rd November 1943, and on 3rd April 1944 LHQ had signalled that these “still appear applicable”. In his letter on the 9th Morshead gave the present disposition of the two forward battalions of the 15th Brigade and continued:

GHQ Operational Instruction No. 46 of 28 Mar [for the Hollandia operation] ... states New Guinea Force will “continue pressure against the Japanese in the Bogadjim area”. GHQ communiqué No. 723 of 2 Apr stated, “our ground forces advancing towards Bogadjim are nearing Yaula 11 miles to the South-west”, and ABC news reports (presumably emanating from and passed by GHQ) indicate that the objective of Australian troops in the area is Bogadjim, though undue regard need not necessarily be given to these reports. But they do accord with the role specified in GHQ Operation Instruction No. 46.

Morshead went on to say that it was planned to establish a strong base at Yaula and push forward from there. “Apart from tactical considerations,” he wrote, “the breaking of contact would lower the present

high morale of 11 Aust Div units and would deprive them of an opportunity to gain valuable experience in jungle warfare.”

Blamey embarked for the United States and England with the Prime Minister on 5th April and did not return to Australia until 27th June. There is no record of any reply to Morshead’s request for this redefinition. There was probably no need for one. The 15th Brigade was now close to Bogadjim. Indeed, there was a Nelson touch about the Australians’ advance over the Finisterres, for it had been made despite orders that no such advance should be made.

While I Corps was at Atherton Lieut-General Herring had retired and, on 10th February, Major-General Savige had been appointed to command I Corps, Major-General Robertson succeeding him in command of the 3rd Division. When recommending Savige’s appointment Blamey had written to the Minister for the Army:

Two officers have been considered for this vacancy – Major-General S. G. Savige and Major-General G. A. Vasey. Both have been very successful in command in New Guinea operations, and I have some difficulty in determining the recommendations to be submitted, since each is capable and very worthy of advancement to higher responsibilities. Having regard to their respective careers, however, I recommend that Major-General S. G. Savige be appointed.

The significance of Blamey’s final sentence is a matter for speculation. It could hardly refer to past careers since Vasey’s experience in command was wider than that of Berryman, a contemporary who had recently become a corps commander, and no less than Savige’s.30

The LHQ signal of 3rd April warning of the changeover of corps headquarters was occasioned, as usual, by the Commander-in-Chief’s desire to give as much experience as possible to all his main headquarters, and also to prevent any of them becoming stale because of too prolonged a spell in the tropics. In accordance with his directive of 23rd December 1943, moreover, I Corps was to consist of the AIF divisions now in Australia, and II Corps of the 3rd, 5th, and 11th Divisions. Blamey decided that the personnel of I Corps should relieve that of II Corps. Thus Berryman and his staff returned to Atherton and Savige and his staff took over in New Guinea; but the corps at Atherton was still called I and the corps in New Guinea II.

There were other changes in the senior commands in the early months of 1944. From 1st March Lieut-General Lavarack became Head of the Military Mission at Washington and Lieut-General V. A. H. Sturdee, who had been in Washington since September 1942, replaced him as commander of the First Army. Lieut-General Bennett, commanding the dwindling III Corps in Western Australia, asked Blamey whether he was

to be given a command in the field and, having been informed by Blamey that he would not, applied for return to civil life. The request was granted, and a few months later Bennett published a book about the campaign in Malaya.

A visitor to Port Moresby in April was Major-General Dewing of the United Kingdom Army liaison mission. He had just returned from a tour of certain areas in New Guinea believed to be suitable for training and acclimatising British divisions to jungle warfare.31

In addition the British Army in India was showing increased interest in learning from the experiences of the Australians. On 25th June 1944 General Auchinleck wrote to General Blamey thanking him for having the officers from India mentioned earlier and forecasting that

we shall soon be asking you for a large number of officers for duty with the Fourteenth Army and in India, if you can spare them. We need them badly – I believe the number is over 600.

As mentioned, a few Australian officers had been sent to India in 1943 to pass on the lessons of the experiences in New Guinea, among them being Brigadier Lloyd. Lieut-Colonel Ford,32 a leading malariologist, went to India in June 1944, four engineer officers had gone in January 1944, one instructor for a jungle warfare school in April 1944. But it was not until October 1944 that a substantial group of regimental officers of the sort who should have gone early in 1943 arrived in India.33

The plan to send “a large number” of junior officers to the Fourteenth Army in Burma encountered a hitch when on 24th January 1944 Blamey found that his Staff Duties Branch had agreed that no guarantee would

be given that an officer arriving in India would be accepted and that two Indian Army Lieut-colonels were in Australia as a selection board. He wired Auchinleck that the proposal that Australian officers should be subject to selection by a non-Australian authority was “obnoxious and unacceptable” and the selection board could not function. Auchinleck agreed, employment of officers selected by an Australian board was guaranteed, and one Indian Army colonel was attached to the board as adviser. Before these officers, 168 in all, had been selected, Blamey received news that the army in Burma would welcome a far larger contingent. Air Vice-Marshal Cole34 who was attached to the Air Command, South-East Asia, from the RAAF, wrote that he had met the commander of the Fourteenth Army, General Slim,35 who had said that he required urgently about 400 young Australian officers as company and platoon commanders. Also the head of the Airborne Operations Division had asked for trained airborne troops from Australia. Blamey replied that the number of officers already being sent to India had been fixed by the Government and was the ultimate that could be spared “having regard to our commitments and the manpower situation generally”. As for the airborne troops, all Australian forces had been assigned to the South-West Pacific Area.

Meanwhile, in New Guinea, the 15th Brigade had been pressing on towards Bogadjim. Marston of the 57th/60th sent his leading company forward from Yaula on 4th April, and on the 6th contact was regained when the Japanese, entrenched near Bridge 6 on the Bogadjim Road, dispersed several Australian patrols. On 8th April – the day the 11th Division took command36 – Marston ordered Major McCall, the leading company commander, to clear the enemy from Bridge 6 and occupy the high ground beyond at Bauak. About the same time Marston ordered deep patrols on the right flank into the Bogadjim Plantation and on the left to Bwai on the Gori River.

As Hammer was certain that the Japanese were on the run along the main Bogadjim Road, he found it difficult to understand why they were still maintaining a force of more than a company between the Mindjim and Kabenau Rivers. To be on the safe side therefore he ordered the 57th/60th and 58th/59th Battalions to “make contact” at Alibu 1 in order to guard against the unlikely threat of a Japanese thrust up the Mindjim while the main attack on Bridge 6 went in.

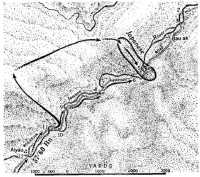

10th–11th April

On the 9th Lieutenant Brookes37 returned from a five-day patrol down the Mindjim Valley through Jamjam into the Bogadjim Plantation. He had stayed there on the night of the 7th–8th April and found no signs of the Japanese. The Bogadjim natives, who were not particularly friendly, told Brookes that there were no Japanese in the general area. While at Bogadjim Brookes’ patrol was fired on by what he was convinced was American artillery and strafed by an American aircraft.

The attack on the 10th on the enemy position at Bridge 6 – two steep heavily-timbered spurs running down from each side of the Ioworo River and making a defile – was described by Hammer as “a textbook operation and in actual fact it developed perfectly”. One platoon advanced down the road to “fix” the enemy positions while the remainder of the company encircled the enemy position, to come in from the high ground to the north. In the first encounter the leading platoon lost two men killed and two wounded. While it engaged the enemy with fire the rest of the company with Lieutenant Jackson’s38 platoon in the lead clambered into position and,’ later in the day, clashed with the enemy in a garden area on one of the spurs. For a while the Japanese held on, but the pressure of the Australians and the accurate fire from Private Hillberg’s39 Bren in an exposed position in the enemy’s rear forced them to withdraw. Towards dusk an Australian patrol moved down a track towards the road where a small Japanese band was found to be still resisting with machine-gun fire. The Australians did not attack for they were sure that the enemy would disappear during the night. As expected there were no signs of the Japanese next morning at Bridge 6 – only bloody bandages and bloodstains on the tracks to remind the Australians of yesterday’s fight. McCall occupied the area and sent patrols forward to Bauak, the last high ground overlooking Bogadjim.

On the 12th two patrols from the 57th/60th led by Captain Fox40 and Lieutenant Atkinson41 set out for the Erima and Bogadjim areas

respectively. At 1 p.m. on the 13th Atkinson entered a deserted Bogadjim and reconnoitred the tracks on both sides of it to the Gori and Mindjim Rivers. There was much evidence that Bogadjim had been an important base, for many trucks, an engineer dump and a signals centre were found there. The Angau representative with Atkinson immediately set about his task of resuming relations with the local natives, many of whom were dressed in Japanese clothes. On the 15th an American patrol of six men from the east joined forces with Atkinson in Bogadjim.

From Bogadjim Marston’s patrols then investigated the line of the Nuru River from Bauri east to Balama; and the three tracks leading north from the Bogadjim Road were probed. By the 15th Fox’s patrol had reached Erima, and reported that there were about 1,000 yards of abandoned beach defences between there and the mouth of the Gori. On the 17th the BBC and ABC announced that “Bogadjim has been captured by an Australian infantry battalion of an Australian infantry brigade which had fought with distinction in the Salamaua campaign and which had been in New Guinea for 13 months”.42

There was little left for the Australian flanking units to do. The 58th/59th Battalion was gradually withdrawn from the valley of the Kabenau and returned to Kankiryo Saddle by 28th April, thus releasing their native carriers to help supply the distant 57th/60th Battalion. On the left flank the 2/2nd Commando Squadron returned to the Kesawai area by the end of April, after Lieutenant Curran had led a ten-day patrol into the Jappa-Oromuge-Topopo-Aminik-Kamusi area, from which he returned with the news from the natives that the Japanese had left the western area for Madang three weeks previously. During this period also the first battalion of the 18th Brigade – the 2/10th – was flown to Lae ready to return to Australia.

Far behind the spearhead of the 15th Brigade, and as though to emphasise the lost cause of the XVIII Japanese Army, there was a flurry northeast of Kaiapit. As a result of an Angau report that there were some enemy in the Wantoat area, a platoon from the 11th Division Carrier Company (which had relieved the 6th Machine Gun Battalion at Gusap), accompanied by the company commander, Major Armstrong,43 was flown

to Kaiapit on the 15th and ferried thence by Cub to Wantoat. Advancing along the Ikwap Track the platoon learnt that the Japanese were in Tabut. Surrounding the village the Australians attacked at dusk. Four Japanese were killed and two escaped. Next day one of the stragglers was speared by a native and on the 16th Armstrong led a patrol to the upper reaches of the Wantoat River where four Japanese were seen with about 20 natives, squatting in the river bed. Warrant-Officer Seale of Angau sent his police boys to mingle with these natives and at a prearranged signal the police boys grabbed the Japanese and overpowered them. Thus Armstrong returned with four times as many prisoners as the 7th Division had been able to capture in several months. Two of the prisoners were from the 20th Division’s engineers and two from the 238th Regiment.

Other offensives were now imminent and for one of these the 32nd American Division at Saidor was required. On 13th April MacArthur’s headquarters instructed that a brigade group of the 5th Australian Division would relieve the Americans at Saidor as soon as possible. General Ramsay then warned the 8th Brigade to prepare to move to Saidor whence it would maintain contact with the Japanese withdrawing to Hansa Bay and Wewak. The 15th Brigade would move across from the Ramu and come under Ramsay’s command. On the 17th Savige was instructed that the 5th Division should occupy Madang but that the 15th Brigade should be used operationally only in an emergency. On the 22nd the headquarters of the 8th Brigade, portions of the 30th Battalion and “A” Company of the Papuan Battalion were flown to Saidor. Next day the 32nd American Division made available 12 LCMs which carried these 300-odd troops to Bogadjim. The remainder of the 30th Battalion and part of the 35th arrived at Saidor by air on the 23rd.

Although Madang might well be empty, like Salamaua and Lae before it, Hammer was anxious to get there first. While the order for the relief at Saidor and the subsequent advance to the west was passing down the line from MacArthur’s GHQ, General Boase, Brigadier Hammer, Colonels Smith and Marston and Major Travers, with Lieutenant Leahy44 as guide, were marching over the Finisterres to the north coast. When the party reached Bridge 6 on the 20th, Boase, who astonished the younger men by the fast pace he maintained, received a signal that the 5th Division would take charge of the Madang operations. The plan was that the 30th Battalion would occupy Madang. Hammer immediately secured Boase’s permission to dispatch patrols to Amele and Madang. On the 21st Boase met Lieut-Colonel Kyngdon,45 of Ramsay’s staff, at Bogadjim and discussed Ramsay’s tentative plan whereby the 15th Brigade would march over the Finisterres to the north coast. The administrative

difficulties of such a move were pointed out and it was also suggested that it might be preferable to wait until the 57th/60th crossed the Gogol River and fully reconnoitred the area south of Madang for suitable areas where the 8th Brigade could land.

Already on the 20th the 57th/60th was probing north along the coast towards the Gogol River and North-west towards Amele Mission. Dumps of ammunition and all manner of stores and equipment were found in the swampy Bogadjim area and to the north. A patrol to Balama found 16 trucks damaged by air strafing, and on the 21st a patrol to Malaga Hook found six 6-wheeled vehicles. A patrol led by Captain Fox reached Amele without incident on the 24th and returned through Bili Bili on the coast.

Meanwhile a patrol led by Lieutenant Atkinson was instructed to find out if Madang and its airfield were occupied. With 13 men he boarded an American PT boat at 10.45 a.m. on the 22nd. There were several officers and batmen from various headquarters hoping to be there for the kill, and these accompanied the 14 Australians and 14 Americans to Malaga Hook where a landing was made soon after noon. Atkinson found the Gogol a major obstacle. He therefore signalled with a Very pistol to the boat standing off shore. After discussion it was decided that the Americans and a small party from the 8th Brigade which had moved along the coast would rejoin the boat, which would return at noon next day with crossing equipment.

As the boat did not arrive by noon on the 23rd, and as wireless communications had failed Atkinson led half his patrol south and met the signallers laying telephone line near Erima. Information was passed back to his headquarters and he returned to rendezvous with the boat. On the way back a despondent and sick straggler from the 79th Regiment was captured. He also had been unable to cross the Gogol which he had reached five days before and was looking for food when he saw Atkinson’s men. He said that his companions had left the area about a month ago. Returning to the Gogol Atkinson found that the other half of his patrol had unsuccessfully attempted to wade across the river. On returning to the south bank Sergeant Dick46 shot two crocodiles between 12 and 15 feet long. The PT boat arrived at 5 p.m., landed a small party of Americans, took off the prisoner and gave Atkinson a message that over 100 troops would be landing at Bili Bili next day. A dinghy was left for the crossing of the Gogol, which was now urgent.

At dawn on the 24th the patrol tried to cross but the current was too strong. Twenty minutes later when two PT boats were seen near the mouth of the Gogol Atkinson sent out a message in the dinghy asking to be ferried to Bili Bili. By 8.45 a.m. his patrol was aboard. Just at this time four LCMs and a tender on the way north from Bogadjim passed the two boats. The LCMs contained Lieut-Colonel Parry-Okeden’s headquarters and one company of the 30th Battalion, together with the brigade

major, Nicholls,47 who was to reconnoitre the Madang area for 8th Brigade headquarters. Atkinson’s patrol was transferred to an LCM and at 9.20 a.m. landed with the 30th Battalion at Ort just south of the Gum River.

Parry-Okeden had no objection to Atkinson attaching his patrol to the 30th Battalion. Indeed it was appropriate that representatives of both the brigades which had finally cleared the Japanese from the Huon Peninsula should be together for the last triumph. At 12.30 p.m. the junction of the Madang and Alexishafen Roads was reached. While a platoon from the 30th Battalion moved along the road towards the airfield a second platoon accompanied Atkinson in a cautious advance towards Madang. During the advance a mountain gun fired a dozen shells, and there was a sudden burst of machine-gun fire and a couple of grenade explosions from somewhere in the Wagol area. The machine-gun fire did not appear to be directed at the Australians and the shells from the gun landed out to sea. In all probability this was the final defiant gesture by the rearguard of the XV III Army as it left its great base of Madang which had been in Japanese hands since 1942. As the Australians continued along the Madang Road they saw about ten figures at a distance of about 1,000 yards running North-west. After investigating all the side tracks the patrol from the 57th/60th Battalion and a platoon of the 30th entered a deserted Madang at 4.20 p.m. on 24th April. At 5.30 eight LCMs nosed into the harbour to land Brigadier Cameron and the vanguard of the 8th Brigade.

Madang had been heavily hit by Allied air attacks and possibly some demolitions had been carried out by the retreating Japanese. The airfield was cratered and temporarily unserviceable; the harbour was littered with wrecks, but although the two wharves were damaged they could be repaired and Liberty ships could enter the harbour.

The occupation of Madang rang down the curtain on the Huon Peninsula and Ramu Valley campaigns. Quickened planning for the future and further changes in command were pending, ready to meet the changed circumstances in which for six months only a small part of the Australian Army would be in contact with the enemy.

Before his journey to England General Blamey had already decided to return to the old organisation whereby New Guinea Force and Corps Headquarters in New Guinea were amalgamated. On 25th February he had written to Berryman:–

I have not been able to obtain a final decision in relation to commands, etc., necessitated by your campaign recently terminated, although the recommendations were made to the Government prior to the beginning of the campaign. This has been influenced to some extent by the pressure of politicians such as Foll, Page, and particularly Cameron.

He informed Morshead on 3rd March, however, that Morshead himself would return to the Second Army, personnel of New Guinea Force

Headquarters would be sent to other appointments, and II Corps Headquarters would become NGF Headquarters. Thus, on 6th May Savige’s II Corps Headquarters, which had moved from Finschhafen to Lae in preparation for the change, was designated “Headquarters, New Guinea Force” and he became responsible for all Australian activities in New Guinea. In July Morshead was transferred from Second Army to command of the AIF Corps – actually a far more important task – and Berryman became “Chief of Staff, Advanced Land Headquarters”.

The build up of the 5th Division (4th, 8th and 15th Brigades) in the Madang-Bogadjim area continued as fast as limited shipping and air facilities permitted. While the Papuans patrolled to the west from Madang, detachments from the 30th Battalion landed on small islands off the coast and two companies advanced towards Alexishafen. The enemy had sown many land mines, and before the Pioneers started delousing them the 30th Battalion lost 5 killed and 3 wounded from mine explosions. The battalion entered a deserted Alexishafen on 26th April. On the 27th Savige informed Ramsay that only one battalion would be needed at Saidor, and that apart from patrols no major units in the Alexishafen area would move north of the Murnass River. Ramsay was warned that his planning should take into account New Guinea Force’s decision to establish a Base Sub-Area at Madang capable of meeting the requirements of a force of 35,000. Next day Ramsay issued orders that the 8th Brigade would be forward in the Alexishafen area, the 4th and 15th Brigades (less the 24th Battalion destined for Saidor) in reserve about Madang.

In March and April there had been sweeping changes in the organisation and policy of the Japanese forces along their southern front. The headquarters of the Japanese Second Area Army under General Korechika Anami had arrived in Davao, Mindanao, from Manchuria in late November 1943. Anami controlled Lieut-General Fusataro Teshima’s newly-arrived II Army based at Manokwari and Lieut-General Kenzo Kitano’s XIX Army based at Ambon. The Second Area Army was responsible for the area from 140 degrees east longitude west to Macassar Strait and south from 5 degrees north latitude. Thus Hollandia and Australian New Guinea remained the responsibility of General Imamura’s Eighth Area Army. The Admiralties campaign (described in the next chapter) caused a sweeping change in command, for the Eighth Area Army and XVII Army were then cut off. On 14th March General Imamura was ordered to hold out as best he could, and the XVIII Army and IV Air Army were transferred to the Second Area Army, whose boundary was moved east to 147 degrees east longitude.

The Japanese forces facing the Allies in the South-West Pacific Area had been augmented in recent months. Thus in April Count Terauchi’s Southern Army Headquarters, then in Manila, controlled the Second Area Army (150,000 men), the XIV Army in the Philippines (45,000 troops), the XXXI Army in the Pacific islands (50,000 troops), and the 14th Division and other troops in the Palaus (30,000) now based on Menado. Under the Second Area Army were the II Army in western New Guinea and the Halmaheras (32nd, 35th, and 36th Divisions, about 50,000 men), the XIX Army in the rest of the Netherlands East Indies (5th, 46th, 48th Divisions, about 50,000 men) and the XVIII Army (20th, 41st, 51st Divisions, 50,000 to 55,000 men). The isolated Eighth Area Army (140,000 including naval troops) was now directly under Imperial General Headquarters and controlled the XVII Army (6th Division and other troops) and the 17th and 38th Divisions.

At this time the XVIII Army was reorganising at Madang and beyond, and General Adachi was hoping to hold the area between Madang and Hansa Bay. He was ordered instead to pull back west as quickly as possible to Wewak, Aitape and Hollandia, which was to be developed into a major base. The withdrawal as far as Wewak was already under way in March when rearguard companies of the 78th and 239th Regiments were still delaying the American advance west from Saidor and the Australian advance north over the Finisterres. The general picture during March was that the 51st Division was concentrating in the Wewak area, the 20th Division in the Hansa Bay-Aitape area and the 41st Division the Madang–Bogadjim area. The 41st Division was deployed with the 237th Regiment north from Madang, the 238th Regiment between the Gum and Gogol Rivers and the 239th Regiment, assisted by elements of the 78th, responsible for the defence of the southern approaches.

As the Australians pressed closer to Bogadjim and Madang in April, the XVIII Army began a slow withdrawal. When, on 25th March, General Adachi received the orders to withdraw and concentrate at Hollandia, he instructed the 41st Division to hold Madang by rearguard action until the end of April. At the same time he sent the main body of the division to Hansa Bay to relieve the 20th Division, which would then move on to Wewak and Aitape, allowing the 51st to advance to Hollandia in July or August.

The next chapter will explain how the 8th Australian Brigade, advancing from Madang to the Sepik, met only the stragglers of the trapped army. Even with better and more alert planning by Adachi’s staff, however, it is doubtful whether the XVIII Army could have reached Hollandia before the invasion of that base. In April there were still 30,000 men east of the Sepik, and only 770 were being ferried across that river each day. The obstacles to its march were the marshes of the Ramu and Sepik River basins, the mud, the swarms of mosquitoes, the fast river currents and the attacks of Allied planes and naval craft.48 At Lae and at Salamaua the elements had aided the Japanese retreat; thereafter they were pitiless.