Chapter 13: The Fall of Lae

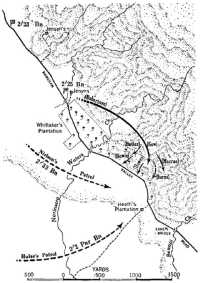

EAST of Lae on 6th September the weather continued to favour the advance. On the right flank the 2/13th Battalion moved east from its base on Yellow Beach and, despite orders to stop at the Buhem River, Lieut-Colonel Colvin sent two companies across the river and along the coast towards the overgrown Hopoi airfield which he occupied without opposition that afternoon. On the main front west of Red Beach the 26th Brigade was about to receive its baptism of Japanese fire. The commander of this brigade, Brigadier Whitehead, was a former regular soldier whose restless and critical mind had led him to leave the army soon after World War I, in which he had commanded a machine-gun company. He had formed the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion in 1940, and commanded the 2/32nd Battalion in the El Alamein operations until September 1942 when he was promoted to his present appointment.

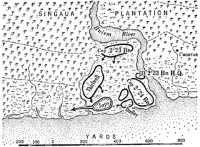

Just before the 2/23rd Battalion was about to move forward early on the 6th, Corporal Fairlie and Lance-Corporal Schram, wet and exhausted, arrived in time to warn that a Japanese company was approaching. The leading Australian company (Captain Dudley’s) was warned to expect an ambush and, 100 yards along the beach, the company was fired on.

Dudley promptly attacked and drove the foremost enemy troops back about 40 yards through dense undergrowth. Major McRae next sent out Captain Thirlwell’s1 company to go North-along the Buiem and then west for about 250 yards before turning south and closing in behind the enemy. While Thirlwell was cutting a track through the dense jungle and reporting his progress by means of three walkie-talkie sets placed along his route Dudley’s men and the Japanese remained close to one another, both pinned down by heavy fire.

At 10.30 a.m., after enemy mortar fire had inflicted 16 casualties on the 2/17th Battalion behind McRae’s position, Dudley sent Lieutenant Atkinson’s2 platoon into the attack. Effective use of grenades drove the enemy back another 40 yards and there the Japanese and Australians were again both pinned down. With the possibility of a stalemate developing, McRae sent in a third company to join in the assault, but the Japanese apparently guessed or heard the moves being made to encircle them and decided to withdraw. At 12.40 p.m. Thirlwell reported that he was in contact with about 80 enemy withdrawing to the west along the coast. Although some casualties were inflicted on them, the Japanese overran Thirlwell’s southern positions and withdrew to the west across the little creek which the Australians were guarding. Not only had they

6th September

temporarily escaped, but they now pinned down the company from the flank.

Anxious to wipe out the remaining Japanese, McRae at 1 p.m. ordered the two encircling companies to advance south to the coast with the little creek as a boundary between them. At the same time Dudley advanced west for 200 yards until shortage of ammunition stopped him. His two platoons killed 20 Japanese during this advance, including two who committed suicide by clasping grenades to their chests.

There was a surprise in store for about 60 escaping Japanese. As they struggled back towards Lae they were intercepted about 2 p.m. by Sergeant Lawrie’s lightly equipped platoon west of the mouth of the Bunga River. Between this time and last light on the 6th this courageous and determined NCO inspired his men to resist six attacks by the frantic enemy who found they could not use the track which the tiny Australian force was holding so grimly. The Japanese attacks were heralded by bugle calls and shouts thus warning the Australians where and when to expect them. The fighting was close and fierce and the bayonet was used to eke out the Australians’ slender ammunition supplies. Lawrie alone killed ten Japanese before the mauled enemy remnants infiltrated past his position towards the west. With four men dead and one wounded Lawrie waited until after dark before moving east to join his battalion, which he did half an hour before midnight.

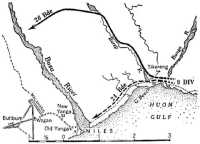

Meanwhile General Wootten had been urging his other troops west. His headquarters was established at Aluki 1 where the 2/48th Battalion remained in reserve. The three battalions (2/28th, 2/32nd, 2/43rd) of the 24th Brigade advanced west through the kunai, mangroves and jungle of the hot coastal plain, and camped between Apo and Aluki where the 2/32nd Battalion was detached as an additional divisional reserve. After conferring with Wootten, Brigadier Evans with his staff pushed on to Apo Fishing Village where they made arrangements for the 24th Brigade to take over the coastal advance and free the 26th for the northern advance in accordance with Wootten’s orders on the 5th.

Brigadier Evans was a keen and able citizen soldier, and a Melbourne architect. He had been first commissioned in 1924, and by 1939 was commanding the 57th/60th Battalion. In 1940 he had helped to form “Albury’s Own” – the 2/23rd Battalion – and had led it from its formation through

the siege of Tobruk and part of the battle of El Alamein. He was appointed to command the brigade near the end of the El Alamein operations.

On both the 5th and 6th Japanese aircraft bombed Red Beach, the Aluki Track and the amphibian craft plying between the beaches, but this did little to hinder the movement of stores. Soon after midnight on the 6th–7th September 5 LCVs and 3 LCMs landed stores from Red Beach at Apo Fishing Village to alleviate the severe ration and ammunition shortage among forward troops and, by shortening the supply lines, to enable the advance to gather momentum. That night the rain poured down, soaking men and equipment, filling weapon-pits, and forcing the troops to perch like bedraggled fowls on logs or anything else above ground level. There were anxious thoughts about crossing the Busu.

Through mud and slush the advance continued on the 7th. Before dawn an LCV and an LCM landed stores on the beach south of Singaua Plantation where the 26th and 24th Brigades, each now with only two battalions, picked up supplies before moving west. Leading the advance the 2/24th Battalion reached the Burep at 11 a.m. followed by the 2/23rd, the 2/4th Independent Company and a Papuan platoon. A rumour that the Japanese were in Tikereng caused the 2/24th to advance cautiously until the cause of the rumour turned out to be Captain Cudlipp’s3 company of the 2/23rd awaiting the arrival of the remainder of the battalion. The 2/24th followed by brigade headquarters and the 2/23rd then moved rapidly North-west up the Burep and camped about five miles from the coast. Wootten had originally intended that the 24th Brigade would relieve the 26th after the Busu had been crossed, but opposition encountered at Singaua Plantation and expected at the Busu dictated relief farther east at the Burep where the 2/28th Battalion relieved the 2/23rd.

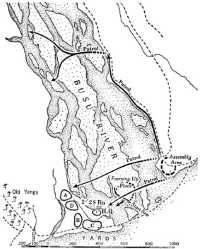

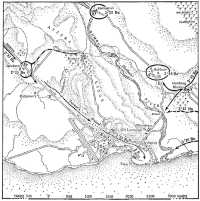

Orders for 8th September were that the two forward brigades should cross the Busu. Again heavy rain fell during the night until dawn, making marching very difficult. The two leading battalions-2/24th on the north and the 2/28th on the coast – advanced towards the Busu. The 2/24th had to cut a track, and to ensure the security of the advance and the compactness of his battalion, Lieut-Colonel Gillespie decided that companies should cut parallel tracks on each side of the main one. This reduced movement to a snail-like pace of about 300 yards an hour and prevented the battalion from quite reaching the Busu on 8th September. Captain Garvey’s4 2/4th Independent Company, under Whitehead’s command, passed through the 2/23rd Battalion that morning, followed the course of the Burep north to the foothills, and thence scrub-bashed through thick jungle to the west trying to discover whether it would be possible to make a jeep track from the Burep to a large kunai patch east of the Busu.

8th September

Along the coast the 2/28th reached the east bank of the Busu at 4 p.m. on the 8th. Towards evening two Japanese were seen on the other side. Lieut-Colonel Norman5 of the 2/28th therefore expected that an attempt to cross the river would be opposed. Swollen by heavy rains the Busu was a formidable obstacle. Up from its mouth it was between 600 and 800 yards wide and flowing in several channels. In the main and westernmost channel the river was moving between 10 and 12 knots and was 5 to 6 feet deep. Wading seemed out of the question.

All activity on the 9th centred upon crossing the Busu. At 6 a.m. the leading platoon of the 2/24th Battalion arrived near the river. The battalion was not encouraged by what it saw even though no Japanese were seen on the opposite bank. The flooded river was flowing at 13 knots, much faster than at its mouth, and was divided into three channels 65 feet, 95 feet, and 40 feet wide, and varying in depth from one to seven feet. The strongest swimmers without clothes might be able to reach the other bank if they were not dashed against protruding rocks but naked they would not be much use against any Japanese awaiting them. While patrols reconnoitred for better crossing places Gillespie realised that bridging and ropes would be necessary.6

A patrol of the 2/23rd later in the day reported seeing an enemy patrol on the opposite bank north of the proposed crossing of the Busu. To the north again the 2/4th Independent Company reported that it would be “impossible” to make a jeep track to the kunai patch, and on the extreme north one of its platoons crossed the Sankwep River and moved north along the east bank of the Busu towards the kunda bridge.

Near the mouth of the swirling river the 2/28th received orders on the afternoon of the 8th to establish a base on the west bank at dawn

on the 9th. Reconnaissance patrols before dawn on the 9th reported that there was no suitable crossing for 1,000 yards from the mouth.

After dawn Lieutenant Rooke’s7 patrol attempted to cross near the mouth and although it reached the large island in the centre of the Busu’s mouth Rooke found that he could go no farther. About 8.40 a.m. Norman ordered Captain Lyon8 to attempt the crossing by sending one platoon across via the sandbank at the mouth, while the remainder of the company covered the crossing with fire from Rooke’s island. The platoon made the attempt at 9.15 a.m., but when one of the forward scouts was killed and another wounded by enemy fire Lyon withdrew the platoon while the Australians’ mortars bombarded the western bank.

Wootten was disturbed at the unexpected delay and realised that, unless the crossings were quickly secured, “the Japs, knowing our situation will fortify banks and strongly oppose us”. He therefore ordered Whitehead and Evans to seize bridgeheads over the Busu not later than first light on the 10th. These orders reached Norman at 12.50 p.m. on the 9th, and he determined that, as there was no other way of crossing, his battalion would walk from bank to bank.

Second in command of the 2/32nd Battalion was Major Mollard9 who had lived in Lae for two years before the war. Early in the afternoon of the 9th Evans sent him to the 2/28th Battalion to answer any questions asked by Norman and his staff. The main question which Norman asked him was “Where do we cross?” Mollard pointed out that the natives always crossed at the mouth (or at the spot where the 26th Brigade was trying to cross). Norman decided against this advice and ordered a crossing higher up for reasons later described in a broadcast talk:10

My personal reconnaissance indicated the best approach to be directly across from the island. Patrols had been unable to find anything better upstream within our right boundary and the bar could not be considered. Not only was it used by the Japanese, as indicated by footprints, but troops crossing there would be so strung out, on a front of one or two men, as to render them most vulnerable to enemy fire. ... Owing to the island and a slight bend, there appeared to be a drift in the current towards the far bank, very little further downstream. Also, the far bank rose abruptly giving protection to anything below. This would permit some reorganisation before the troops went over the top.

Coolly Norman informed his company commanders that the battalion would assemble on the east bank, form up on Rooke’s island, and cross the last channel of the Busu in four extended lines starting at 5.30 p.m. Norman chose this time because he believed it to be the enemy’s “rice time”. So, in the afternoon, the battalion waded to the island, keeping as well concealed as possible, although an alert enemy on the western bank could not have failed to observe the preparations. Half an hour before the starting time the artillery was used for the first time when

9th September

22 rounds from the troop of 25-pounders already at the Burep11 were fired on to suspected enemy positions west of the mouth of the Busu.

Two minutes before time Lieutenant Hannah12 led his company from the forming-up place on the island to the start-line on the island’s far edge. As his men, in a long line and without hesitation, stepped into the swirling water the other companies moved one after another to the start-line at two-minute intervals. It was an incredible crossing. The men were swept off their feet by the fierce current, which snatched weapons from some of them, but most were swirled towards the west bank where they grasped overhanging boughs and kunai.

Meanwhile Lyon’s company was stepping into the river, and the same story was repeated as the human corks bobbed to the other side. Those who reached the far bank first turned to help their comrades, formed human chains out into the river, and held out branches and weapons to be grasped. It was harder for Norman’s headquarters and the third and fourth companies because they saw men swept away in front of them, but the lines never faltered. Seeing the difficulties and the congestion ahead, the last company, followed by the main part of battalion headquarters, swung right incline, entered the river 100 yards higher up, formed a chain and reached the western bank north of the battalion’s position. Describing the crossing Mollard wrote later: “It looked for all the world as though a giant hand was snatching them across to the far bank so fast did they travel the intervening distance.”

The battalion had surprised the enemy who had not considered it possible for a crossing to be made except along the bar at the mouth.

Consequently, most of the enemy fire was directed there, and by the time they began firing on the lines of men it was too late as they were almost hidden beneath the high western bank. Great good fortune also favoured the 2/28th and indeed it was fitting that it should. Where the battalion hit the west bank there was a bend in the river, and it was this unexpected help from nature which probably prevented the battalion from being swept out to sea.

On the far bank Hannah was the first man across, and soon other bedraggled men were struggling up the western bank behind him to form the bridgehead. About 150 yards ahead Corporal May13 saw an enemy machine-gun post 100 yards inland from the beach which was doing most of the firing along the bar. He advanced alone, hurling a grenade and firing his Owen, and wiped out the post, thus saving many Australian lives.

Describing the happenings on the far side a chronicler wrote:

It was inevitable that there should be some confusion on the far bank. The companies had set out in orderly manner, but the river swept them into mixed groups along the bank. Darkness and heavy rain rendered difficult the task of reassembling and exploiting. ... [Hannah] with numerous desert patrols in his record, had managed to keep most of his men together, as they were first across, and by orders shouted down to subordinate officers and men other company commanders were able to draw a large percentage of their troops together. Cries of “‘A’ Company here!” “Where’s ‘C’ Company?” and so on were heard on all sides as men trampled countless paths through the kunai.14

Obviously such a crossing could not be made without cost, but for the results achieved, the cost was small. Thirty men had been carried towards the sea and did not make the crossing. Of these, 13 were drowned, and the remainder were saved by the bar where the water was only 3 feet deep. Under heavy enemy fire, these shivering men hid behind the scanty vegetation on the bar until they were rescued six hours later by their own Pioneers and Captain Buring’s15 company of the 2/43rd Battalion.

By 6.30 p.m. the company commanders had reorganised their scattered platoons and occupied a bridgehead 150 yards deep and 650 yards long. Swamps and darkness prevented Lyon on the north and Hannah on the south from advancing to the small creek west of the Busu. Then the rain came again and fell heavily throughout the night. “The reaction of the river crossing and the fact that the men had no protection of any kind might have reacted very unfavourably had they not been so fit and morale so high,” wrote their commander in his report.

Twenty-five per cent of automatic weapons and about 80 rifles had been lost in the crossing and ammunition and signal equipment had been damaged. As it was imperative to re-establish communications with brigade

headquarters, Norman’s Intelligence sergeant, Crouchley,16 although slightly wounded, swam back across the river and told Evans what had happened. Evans did his best to replace the lost weapons and sent up supplies of ammunition to the east bank where Buring was organising dumps ready to be sent across and attempting to establish telephone communication with Norman. By 11.30 p.m. Norman’s battalion headquarters was connected with Buring’s company largely due to the efforts of Private Trenoworth17 of the 2/28th and Private Swift18 of the 2/43rd, both of whom swam the river with telephone line. The achievements of Crouchley, Trenoworth and Swift were all the more meritorious because the torrential rain had caused the Busu to rise another foot.

Thus Norman had established his bridgehead before first light on the 10th. There were many individual acts of gallantry during the crossing. Most Australian soldiers who fought in the South-West Pacific would agree that they would rather face an aroused enemy than an angry Nature. It took a cold and calculated form of courage for the West Australians to walk into the raging Busu on 9th September 1943, particularly because, as in every unit, there were some men who could not swim.

Rain continued on the 10th, making the tracks unsuitable even for jeeps, and causing the 2/28th Battalion to wonder how it had ever crossed the flooded river behind it, and the 2/24th Battalion to wonder how it ever would. The diarist of the 2/32nd, which was marching along the coast to rejoin its brigade, described the men as “drowned rats” and eulogised the cup of tea and biscuits provided by the Salvation Army at the Burep crossing: “To this noble institution the battalion once again tenders its thanks for another demonstration of practical Christianity.” Such an addition to rations was very welcome for most battalions were short of food. One battalion diarist described the ration situation as “totally inadequate and men are now definitely experiencing hunger all the time”.19

This situation was not due to any omission on the part of Rear-Admiral Barbey’s Task Force, which was regularly supplying the beaches, or to any want of enthusiasm on the part of the Shore Battalion, but to the general divisional shortage and to the difficulty of delivering rations to forward troops over long, sodden land supply lines. Canned heat issued to some battalions on the 10th helped to make the frugal meals more appetising and at least enabled the men to have a hot dish.

Apart from shortages, the ration scale as laid down was inadequate for an operation which lasted as long as the Lae one. All brigades had protested when the ration scale had been outlined at Milne Bay. They were told, however, that it was the scale used by the 7th Division in its previous operations in New Guinea. “However,” wrote Whitehead later, “the 7th Division had learned their lesson and the Division went into the Markham Valley operation with a ration scale completely different and much more adequate than that laid down for the 9th Division.” The intention was that the scale should apply only for the first few days; in fact it lasted throughout the campaign.

An officer of the 2/23rd Battalion (Captain Lovell20) who was something of a cartoonist produced a comic strip about the battalion’s experiences with rations and included one telling picture in which a Japanese was broadcasting the fact that there were 20,000 Australians lost and starving in the jungle around Lae. The cartoonist had added, “Who the Hell says we are lost?”

In spite of the weather and hunger the two forward brigades pressed on with their task on the 10th. In the northern foothills Lieutenant Hart’s”21 and Lieutenant Cox’s22 platoons from the Independent Company bridged and crossed the Sankwep River near its junction with the Busu, while the third platoon remained south of the junction to carry rations. Advancing up the east bank of the Busu, Hart saw four Japanese moving up the west bank and sent two sections hurrying north to meet them, if they tried to cross the kunda bridge. Allowing them to cross the river Lieutenant Staples’23 section then killed all four. Hart sent back the captured equipment, continued his advance and camped near Musom 2 in company with a Papuan section.

To the south Whitehead was urging the provision of engineer stores for bridging the Busu, the 2/24th Battalion was making unsuccessful attempts to cross the river, the 2/23rd Battalion was waiting, and the 2/48th Battalion was assisting the 2/7th Field Company to corduroy the jeep track from the Burep to the Busu as well as carry forward twelve miles of signal cable on mile reels each weighing 80 pounds.24

Heavy rain had caused the river to rise and render foolhardy any attempt by the 2/24th Battalion to wade across. When, at midday, a small party of engineers from the 2/7th Field Company arrived with rubber boats and rope, Sapper Amos25 and another man swam the flooded river

with a cable attached to a three-inch rope, but the cable broke.26 Warrant Officer McCallum27 then swam the river with another cable attached to the rope, and the three men secured it to the far bank. No sooner had they done so than the Japanese, who had received ample warning of the battalion’s intention to cross, fired on them from a village on the western bank, killing Amos and forcing the other two men to hide. For forty minutes the 2/24th fired on the Japanese village. The hope of crossing unopposed had now vanished.

Several different methods of crossing were tried during the afternoon. Lieutenant Braimbridge28 and one of his sections entered four of the engineers’ boats which had been tied end to end and attached by loops to the rope across the river, but the current swamped the boats when 30 feet from the near shore. Other attempts to cross by towing boats containing equipment along the rope, and by crossing hand over hand along the rope, were abandoned because of enemy fire. McCallum and the surviving engineer finally swam back, McCallum reaching the east bank one mile downstream. As dusk came, a hold-fast was dug on the island in the Busu to facilitate swinging a boat across on the pendulum principle.29 Again at night, it rained heavily.

In the swampy triangle formed by the western bank of the Busu and the small creek Colonel Norman issued his orders at 6 a.m. on the 10th for an attack on the Japanese who were sharing the triangle. Between 11 a.m. and midday small parties of enemy tried to infiltrate past Captain Newbery’s30 left flank positions on the coast. At midday the enemy fiercely attacked the left flank, using the beach as their line of advance and causing casualties with grenades. Largely because of the quick thinking of Sergeant MacGregor31 who occupied the only slight rise from which the beach was fully visible, the enemy attack was beaten off. Although exposed to the enemy the gallant MacGregor refused to budge, even after he was mortally wounded, until the Japanese had been repulsed.

Hannah, meanwhile, was meeting no opposition in his advance down the west bank of the creek and at 2.20 p.m. reported that he was nearing the coast. Along the beach Newbery’s company, particularly Lieutenant Brooks’32 platoon, was under heavy fire from an enemy force in a swamp to the west. Brooks obtained permission to attack the Japanese ahead, and while the advance of the other companies was halted Brooks’ platoon,

strengthened by a detachment from another platoon, advanced into the swamp. Waist deep, with tall tangled kunai and mangroves growing above, and heavily outnumbered, Brooks and his men attacked the enemy positions on several small islands. With great dash and determination the platoon overran these islands and almost annihilated the Japanese perched on them. For the loss of 4 men killed and 17 wounded Brooks’ human amphibians killed 63 Japanese and captured much equipment including eight automatics. After this brief and severe clash the platoon withdrew and re-formed, and it was found that several men were missing. In near darkness the platoon returned to look for any wounded. It was already difficult to tell enemy casualties from their own in the swamp and with the light fading, but several were brought back. At one point, right on the beach line, Private Leonard33 was lying, shot through the head, completely encircled by bodies of dead Japanese. Leonard had been a champion axeman, and it was almost as though he had been armed with an axe, not an Owen gun, so complete and so close was the circle of bodies.

As early as 7th August, General Herring had conferred with General Wootten about moving the 4th Brigade to take over the beach-head areas after the landing. On the 10th Admiral Barbey had agreed that he could transport another brigade, and now, on 5th September, the commander of the 4th Brigade, Brigadier C. R. V. Edgar, in Milne Bay received a warning order that his brigade was on six hours’ notice to move by sea. In six LSTs and six LCIs the brigade left Milne Bay on the 9th, spent the night in Buna harbour, and arrived off Red Beach at 10.30 p.m. on the 10th. An hour after midnight headquarters and the three battalions – the 22nd, 29th/46th and 37th/52nd – were ashore.

North-west of Lae the Nadzab area was a hive of Allied activity. The diarist of the 2/6th Field Company wrote a terse and vivid description of the work on the vital Nadzab airfield:

Work begins at 0700 – an all-in go. Paratroops, sappers, pioneers and natives all cutting grass flat out. The cut grass is burned on the strip. At 0940 a Cub plane with Colonel Woodbury lands. The first three transport planes land at 1100 hours before the strip is quite completely cut, and nearly run down many of the motley throng. At 1400 planes start landing and continue until 1700 – about 40 planes come in. Clouds of black dust everywhere and all concerned look like “Boongs”. The CRE arrives. ... Still no sign of the enemy. One transport plane overruns end of strip and smashes a wheel on the stumps.

So the 6th passed at Nadzab in a swirl of black dust. The Douglas transports which landed among the workers on the rough airfield contained mainly American and Australian engineers under the command of General Vasey’s chief engineer, Lieut-Colonel Tompson. Engineer equipment which arrived in the transports belonged mainly to Colonel Woodbury’s 871st American Airborne Engineer Battalion from Tsili Tsili. Anti-aircraft guns were also carried on these first flights from Port Moresby

and Tsili Tsili. No infantry arrived at Nadzab on the 6th although divisional headquarters and the 2/25th Battalion were flown to Tsili Tsili in the morning. Bad weather over the Owen Stanleys prevented any more flying from Port Moresby.

On the 7th, however, reveille for the battle headquarters of the 25th Brigade and for the 2/33rd Battalion was sounded at 3.30 a.m. Soon afterwards the battalion moved to the marshalling park in three groups of trucks for emplaning at Jackson’s, Ward’s and Durand’s airfields. Eighteen trucks were directed to the marshalling park set aside for trucks going to Durand’s airfield.

At 4.20 a.m., still in darkness, a Liberator carrying eleven airmen and loaded with four 500-lb. bombs and 2,800 gallons of petrol took off from Jackson’s. It flew so low over trucks moving slowly from the marshalling area towards Jackson’s that the men in the trucks instinctively ducked; the flare of the exhausts momentarily lit up the crouching men and a few jumped from the trucks in sudden alarm. “You could have lit a smoke from the port exhausts,” said one soldier afterwards. In the marshalling park several men noticed that the bomber seemed to be flying very low, when suddenly the port wing apparently touched a branch of a tree. The bomber then crashed squarely into two more trees. Two loud explosions immediately occurred, parts of the plane flew in all directions, and burning petrol was sprayed over a large area. For a few seconds the whole area was lit by an intense glare.

Five trucks containing members of the 2/33rd Battalion and the 158th General Transport Company were hit by the crashing plane and caught fire, and every soldier in these trucks, which contained mainly Captain Ferguson’s34 company, was either killed or injured. Fifteen were killed outright, 44 died of injuries, and 92 were injured but survived. All members of the Liberator’s crew were killed. Immediately after the crash and the explosion of three of the Liberator’s bombs the victims’ comrades attempted to extricate the injured and the dead but the fierce blaze in the trucks compelled them to remain impotent and stunned bystanders. Several injured men with their clothes and equipment on fire got through the blaze themselves and were given first aid. Captain Seddon promptly obtained fire fighting equipment and called medical assistance and ambulances which raced the injured to hospitals.

Ammunition continued to explode and the fires to blaze for an hour, while the remainder of the battalion emplaned, according to schedule. Time could not be wasted, for weather over the Owen Stanleys usually made flying unsafe in the afternoon. Saddened by the freak tragedy, 540 members of the 2/33rd and brigade headquarters were flown to Tsili Tsili. By 12.30 p.m. the weather had closed in over the mountains. During the day 59 transport planes arrived at Nadzab.

By 10 a.m. on 8th September after the remainder of the 2/25th Battalion and part of the 2/33rd had been ferried from Tsili Tsili to

Nadzab, Vasey gave Brigadier Eather the task of advancing down the Markham Valley towards Lae. Aerial reconnaissance at first light had disclosed no sign of the enemy between Nadzab and Heath’s Plantation.

The 2/31st Battalion and the larger part of Eather’s headquarters took off from Port Moresby at 12.25 p.m. but at this late hour it was a gamble whether the planes could negotiate the mountains. At 1.50 p.m. the flight returned to Port Moresby, driven back by bad weather. On the 8th 112 transports landed but Vasey was annoyed because the planes were not arriving in the proper sequence. To General Berryman35 he signalled that he considered “contents of planes and sequence of arrival here my responsibility”, and that he strenuously objected to “any variation my movement plan which is designed for operations against Lae”. “Request you advise 5 AF accordingly and not interrupt operational plan. ... Rome was not built in a day.” Berryman would have been less than human had he not resented the rebuke and he noted of Vasey’s attitude, “It does not go down with the staff here.” Wisely, however, he did not reply and Vasey’s plane schedule was henceforth adhered to.36

At 7 a.m. on the 9th Major Robertson’s37 company of the 2/25th Battalion led the 25th Brigade’s advance down the Markham Valley from the Gabmatzung area. It had been the lot of the 25th Brigade to fight in difficult country, first in the mountains of Syria and then in the Owen Stanleys and round Buna. In common with his colleagues in the 7th Division, the commander – Brigadier Eather – was no stranger to jungle warfare, having led the brigade in the Papuan campaign. His battalion commanders – R. H. Marson of the 2/25th, E. M. Robson of the 2/31st and T. R. W. Cotton of the 2/33rd – had all led companies in the Syrian campaign and had served with the units they now commanded in the Papuan operations.

By midday the battalion had occupied Old Munum. Patrols forward to Yalu in the afternoon confirmed an aerial report that there were now no Japanese in the area, although there were signs of their presence about two days previously. Later on the 9th the remainder of the 2/33rd Battalion was ferried across from Tsili Tsili. Once again bad weather prevented the 2/31st leaving Port Moresby although 116 transports landed at Nadzab. The heavy rain which had made the Busu River such an obstacle for the 9th Division, and had aided the Japanese fighting for Salamaua by flooding the river in front of the 5th Division, now made the Nadzab airfield unserviceable and prevented any aircraft landing on the 10th.

By 8 a.m. that day the 2/25th Battalion resumed the advance towards Lae. Captain F. B. Haydon’s company was 200 yards past the junction of the Markham Valley Road and the track to Jensen’s Plantation when, at 1 p.m., it was fired on. Withdrawing to the track and road junction Haydon sent out three small patrols to try to find the enemy – one north to Jensen’s and along the foothills to Jenyns’ Plantation; a second along the left-hand side of the track; and the third along the right-hand side. When crossing a creek the leader of the middle patrol, Lance-Corporal Littler,38 was wounded. Corporal Brockhurst39 then led out five men to bring in Littler. While attending to the wounded man nine Japanese opened fire on Brockhurst’s little band from behind and another enemy patrol fired from the front. Brockhurst attended to Littler’s wounds while his party returned the fire. He then entered the fight and shot two Japanese, after which he found a safe route back to Haydon’s perimeter.

South of the Markham, meanwhile, Wampit Force was attempting to pinpoint enemy positions at Markham Point, mainly round the area of the Southern, Central and River Ambushes. On the 8th Lieutenant Baber’s patrol reached 100 yards south of the River Ambush where they heard enemy voices. Another patrol exchanged shots with the enemy near the River Ambush.

At 5.30 p.m. that day Lieutenant Childs and Private Walker crawled back to the Golden Stairs. Childs, who was wounded in both legs, and Walker, wounded in an arm and a leg, had been unable to rise from the ground. During their laborious and painful crawl through enemy lines from the evening of the 4th their wounds had become flyblown. Fortunately Childs had been able to use his hands to make detailed notes of enemy dispositions and to shoot with a pistol a prowling Japanese who attempted to strangle him. From information which the two men had gathered it seemed to Colonel Smith that the River Ambush might not now be occupied by the enemy. Patrolling for the next two days was therefore directed towards finding whether it would be possible to break the enemy lines near the river, but torrential rain and poor visibility prevented any worthwhile progress.

Herring now asked Vasey what assistance could best be rendered by Wampit Force. Vasey replied on the 10th that he considered that its best role would be to prevent the 200-odd Japanese at Markham Point from crossing the river to help the defenders of Heath’s Plantation. Smith therefore received orders from Herring stressing the importance of preventing the enemy escaping across the river. As further frontal attacks on an alert and entrenched enemy at Markham Point would cause needless casualties Smith made several requests for an air attack on Markham Point, so that his men could attack “on its heels”.

East of Lae on 11th September the 4th Brigade began to relieve the scattered 20th; and the 2/17th Battalion was placed on an hour’s notice to move to the Busu to form a firm base for the 26th Brigade when it eventually crossed the flooded river.

On the right flank of the division Hart’s platoon of the 2/4th Independent Company in the Musom 2 area had explicit orders not to cross the Busu nor to go beyond Musom 2. At the kunda bridge itself Lieutenant Cox’s platoon was guarding the crossing. On the 11th his sentries allowed a Japanese accompanied by two natives to cross the bridge from the west bank and then sent police boys to catch them. An hour later (at 3 p.m.) about 15 Japanese and 20 natives carrying rations approached the bridge. Cox held his fire until the Japanese began to cross. Although the Australians’ opening bursts were not quite on the target, two Japanese fell into the river and two were killed near the bridge. Next day Cox’s platoon noticed the Japanese digging in on the western bank. At 3.20 p.m. when another enemy party came up from the south and talked with the Japanese already there Cox opened up with his three Brens and caused casualties.

To the south the 2/24th Battalion, aided by Major Dawson’s40 2/7th Field Company, continued their attempts to bridge the Busu. The battalion’s Pioneer platoon began bridging the first stream of the Busu using logs placed on stone pylons. Later in the morning the engineers began preparations to cross by swinging one of the two recently-arrived folding boats from the hold-fast on the pendulum. Despite enemy mortar and small arms fire from the western bank during the afternoon, which caused seven casualties, the engineers launched the folding boat at 7 p.m. The first attempt with the empty boat was successful, but when it was being pulled back from the far shore it swamped. The hold-fast line then failed, and the boat, held only by the 3-inch rope attached to the bow, was brought ashore some distance downstream.

While the engineers made preparations to cross the third stream by “kedged raft”, Colonel Gillespie and Dawson decided that the second stream must also be crossed by a log bridge. Alas, the river rose 2 feet 6 inches by midnight and washed away the Pioneers’ first log bridge marooning on the island an infantry platoon and some sappers. These were rescued with difficulty and all attempts to bridge the river were abandoned for the night.

The 12th September was as frustrating as the 11th. The river was falling and the log bridge across the first stream was built again during the morning. The engineers persevered with the folding boat but eventually it sank. Using a tractor, which had arrived before the heavy rains made the jeep track from the Burep impassable, working parties hauled logs to the bank and manhandled them to the sandbank. The first log was too short and the second on being launched swung round, tearing away the pylon and part of the bank. When the log again swung round after

an extension had been fastened to it, and when it was apparent that there were no larger logs in the area, the disgusted workers gave up attempts for the night. Summing up the day’s activities of his engineers Dawson noted: “Attempt at kedging fails – consider SBG [small box girder] real answer for main river. Chase stores all day – no result except more [folding boats], so will attempt kedging again.”

At 1 p.m. on the 12th a 2/23rd Battalion patrol found a likely crossing place about 3,000 yards north of the 2/24th where the river was between 70 and 100 feet wide. A large tree when felled might reach across the main stream, which flowed along the near bank, to an island in the centre whence the second stream could be waded. Whitehead then instructed McRae to send a company to cross there. The company arrived about dusk and felled the tree but it did not span the river.

Added to the frustration of being forced to halt for so long the troops in this area were hungry. Six LCMs were caught in a sudden storm on the unsheltered coast and were broached on the night 11th–12th September, but the remainder helped to establish dumps at the new “D” Beach west of the mouth of the Busu. Attempts to build up supply dumps at “D” and “G” Beaches and at the jeep-head on the Burep were handicapped by what Wootten later described as a “most distinct reluctance on the part of the Navy to put into ‘G’ Beach”.41 Stores hastily dumped ashore at Red Beach had therefore to be carried forward to the new beaches. It was only because the hard-working small craft made three trips a night from Red Beach that supplies, though inadequate, were kept up to the forward brigades. Under battle conditions novel to it, the “Q” side of the 9th Division tried its hardest to supply the forward troops. One error which would not have been committed in a more experienced jungle formation was the failure to send forward the mosquito nets and groundsheet rolls of the 2/17th Battalion “despite every effort and repeated requests by Brigade and its staff”. The medical officer of the 2/23rd Battalion, Captain Davies,42 scribbled a note to McRae on the 11th that rations were “quite inadequate considering the strenuous physical exertion involved”. Continuing, he wrote: “Symptoms of malaria and vague dyspepsia are frequent and men are constantly complaining of weakness and inability to stand up to the work. Unless the quantity of food is increased the men will not be able to carry on under existing conditions.”

The company of the 2/23rd which had been in the ill-fated landing craft at the landing was again the butt of misfortune on the 12th when a lone enemy shell burst in a tree killing Lieutenant Triplett,43 and wounding 11, including Lieutenant Hipsley44 (who remained on duty as company commander) and Captain Davies, who died later. Farther to the east the

gun area on the Burep was attacked by 12 enemy bombers which inflicted 21 casualties.

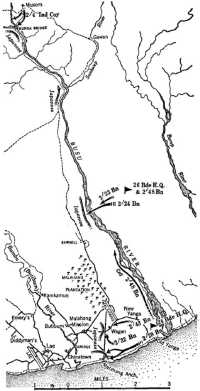

On the coast Brigadier Evans had more cheerful news, although he was disappointed when informed that he must not let the 2/32nd Battalion pass through the 2/28th and resume the coastal advance. Wootten was unwilling that this battalion, until recently his divisional reserve, should be committed so soon. A clash of temperaments between Wootten and Evans was now becoming evident. Wootten was urging Evans on faster, and Evans felt that the services of one of his battalions was being denied him and the others were doing all humanly possible in the face of a stubborn enemy and a turbulent Nature. Evans believed that, if he could have only two small landing craft to move his troops in bounds along the coast and so avoid the slogging march along the coastal flats, the advance would be expedited. Wootten, however, had to reserve his few small craft for the movement of supplies for both brigades. Evans had been forced to strip the 2/43rd Battalion of weapons and ferry them over the Busu on the afternoon of the 11th by rope and punt to the 2/28th Battalion at a time when the better course would have been to use an LCVP Evans, however, arranged with the American boatmen to lend him an LCVP for a few trips which enabled him to equip the 2/28th Battalion properly again and get the 2/43rd moving inland. “If I could have used two boats under Brigade command,” wrote Evans later, “our advance would have been faster and I would have been first into Lae.” Wootten wrote later: “Had supplies been landed by the Navy on forward beaches as desired by me, small craft could probably have been made available to Evans.”

The 2/32nd Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Scott45) began to cross on 12th September. The river rose and carried away the steel cable and the ferry ceased for six hours. Three LCVs took over the ferrying. One of these, commanded by Lieutenant Henderson E. McPherson (2 ESB), kept shuttling troops across for 48 hours although it had its rudder shot away and had to improvise another. By the afternoon of the 12th the 2/32nd was ready to take over the bridgehead.

At dawn on the 12th the 24th Brigade was advancing towards Lae in the form of a prong – the 2/43rd on the right towards Old Yanga and the 2/28th along the coast towards Malahang Anchorage. While Captain Catchlove’s46 company of the 2/43rd Battalion patrolled towards New Yanga, Captain Gordon’s47 advanced along the road towards Old Yanga. During the morning both these companies met and dispersed enemy standing patrols, and at 2.30 p.m. a patrol reported that New Yanga appeared unoccupied.

At 3.35 p.m. Catchlove was organising his company on the outskirts of New Yanga ready for an attack, when unexpected and heavy firing came from the direction of a hut. The surprised South Australians were unable to make any impression on the Japanese defenders. They bombarded New Yanga with mortars and many of the 525 shells fired by the two batteries of 25-pounders at the Burep landed on New Yanga. In spite of this a second infantry attack by Captain Siekmann’s48 company of the 2/43rd met the same reception as Catchlove’s and both crestfallen companies, having suffered 22 casualties, were withdrawn to an area half way between Old Yanga and New Yanga.

By the 12th Brigadier Goodwin’s49 artillery was increasing its volume of fire. Targets on this day included the Lae and Malahang airfields. There were now fourteen 25-pounders of the 2/12th and 2/6th Regiments in action along the east bank of the Burep, and the 14th Field Regiment had arrived at Red Beach on the night 10th–11th September. A troop of two 155-mm guns (1917 model) from the 2/6th Regiment arrived at “G” Beach at 2 a.m. on 13th September and both guns were ready for action by 3 p.m. on the 15th.50

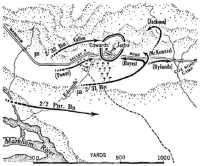

On 11th September, for the third day running, aircraft were unable to land at Nadzab, and thus the 25th Brigade still lacked its third battalion and the advance proper could not begin. While the remainder of the 2/25th Battalion moved along the Markham Valley Road, Captain Hay-don’s company was patrolling the area between Jensen’s and Jenyns’ Plantations, and brushed with the enemy occupying Jenyns’ Track. Advancing along the north bank of the Markham from Narakapor, roughly parallel with the 2/25th Battalion, the 2/2nd Pioneers met little serious opposition. In the afternoon Lieutenant Hulse’s51 platoon dispersed a small enemy patrol and enabled the advance to continue without interruption to a position opposite Markham Point.

South of the Pioneers, across the river, Colonel Smith decided that Wampit Force would prevent the enemy crossing from Markham Point by attacking simultaneously the River and Southern Ambushes. At 4.30 p.m. the 24th Battalion’s mortars fired 126 bombs including 8 rounds of smoke. When the mortar fire ceased the leading platoon attacked the River Ambush position, but the Japanese had moved forward during the bombardment, the mortar smoke was behind them, and they had little difficulty in repulsing the attack. Against the Southern Ambush the leading platoon commander had arranged for the MMGs to fire a short burst when in position whereupon he would fire his Owen as a signal for

the troops to move forward and for the MMGs to give supporting fire. The platoon commander waited on the signal from the MMGs who waited for the signal from the platoon commander; and so time went on, the impetus petered out, and the attack was postponed.

For the 12th Vasey ordered Eather with the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion under command to advance on Lae. On this day, when the 2/31st Battalion at length arrived in many of the 130 planes which landed on the two Nadzab airfields, the 25th Brigade began to meet stiffening opposition. By the time the rest of the 2/25th Battalion joined Haydon at 10.10 a.m., the company had inflicted 37 casualties in its three days of skirmishing with the enemy. Colonel Marson at 1.10 p.m. sent Robertson’s company, accompanied by an observation post officer (Lieutenant Stokes52) from the 54th Battery round the left flank to attack the enemy company reported on Jenyns’ Track. At 3 p.m. it crossed the creek, and advanced through Jenyns’.

An hour later Robertson reached Jenyns’ Track behind the main enemy position after dispersing a small patrol. Cut off from the next plantation (Whittaker’s) by Robertson’s company, the encircled Japanese attacked fiercely but were repulsed by the Australians, who suffered eight casualties. The enemy suffered about 30 casualties, some caused by the artillery. At dusk Robertson established a perimeter defence near the junction of the main track and Jenyns’ Track with Captain Gow’s53 company in support.

On the 12th a patrol of the 2/2nd Pioneers reached Heath’s Track where it crossed the Narinsera Waters; a second, trying to cut a track towards Jenyns’, found the tangled growth almost impenetrable, and a third along the Markham found four folding boats and a new outboard motor near Markham Point. As Colonel Lang’s men watched the Markham racing east in a 600-yards-wide flood they marvelled that they had ever been able to cross it. The fate of Lae might well have been different had Z-day been delayed. As it was, the much smaller but flooded Busu was holding up one division while adverse weather had delayed a build up of supplies for another for three days.

On the 12th Smith’s four platoons round Markham Point made another attempt to capture their objective. The force was now commanded by Captain Bunbury,54 who decided to capture some of the Southern Ambush’s pill-boxes as a “leg in for future grenade exploitation”. Soon after first light the leading platoon used log frames to traverse the minefields but it was caught in heavy cross fire from the enemy who had heavily reinforced the position. The attack was repulsed and two men were killed, including the leading platoon commander, Lieutenant Richards.55 “It is considered,” wrote the battalion diarist with some justification, “that a

further ground attack without support will not be successful and application has again been made for a synchronised air and artillery attack.” With an abundance of air support available to the two AIF divisions, a small modicum might well have been spared to soften up an elaborate defensive position before Wampit Force was asked to advance over cleared fields of fire to attack the strong position. It was not until Smith visited Vasey and asked for his aid that air and artillery support were arranged.

Wootten’s main anxiety was how to keep his troops supplied. Signalling Herring on the 13th he protested against the dumping of stores at Red Beach instead of his forward beaches, pointing out that an LCT (carrying field guns) had already safely beached on “G” Beach.

Under these circumstances (he added) it is considered practicable to beach 3 LCTs on each of G and D Beaches. ESB craft available for forward maintenance from Red Beach are only 3 LCMs and 7 LCVs that arrived night 12/13. All others broached by heavy surf and badly damaged. Land maintenance impossible. Therefore for successful conduct of operations LCTs with re-supply must repeat must discharge on forward beaches as required.

Despite these supply difficulties Wootten ordered the 26th Brigade to cross the river and advance on a two-battalion front, one towards Kam-kamun and Malahang Mission and the other through the sawmill to the north end of the Malahang airfield and Malahang Mission. On the southern front the 24th Brigade would advance with one battalion through New Yanga and Wagan, another along the coast towards Malahang Anchorage, and a third would “mask” the south end of Malahang airfield.

Even high in the mountains the Busu was difficult to cross, despite the fact that local natives informed the 2/4th Independent Company that it was possible to wade across when it had not rained for 24 hours beforehand. At dawn on the 13th Lieutenant Hart sent Lieutenant Staples’ section to attempt to wade across upstream from the kunda bridge. As Staples led his men into the river at first light he was dragged in by the current and whirled out of sight, but finally managed to clamber out 300 or 400 yards downstream; while lying exhausted on the left bank he was wounded by a sniper. The remainder of the section were swept off their feet and scattered along the near bank of the river. Hoping that the Japanese had left the area, Hart then ordered Lieutenant Trevaldwyn’s56 section to cross the river on the kunda bridge, while the rest of the platoon gave covering fire. The Japanese now did what the Australians had done to them previously and allowed some of the section across before opening fire. Before this heavy fire cut the frail bridge to ribbons seven men, including the badly wounded Lance-Corporal Haly,57 were marooned on the far side; others, including Trevaldwyn, were knocked off the bridge into the river and three men were killed.

This desperate situation for the seven men would have been worse but for the cool courage of Private Jaggar58 who attacked and destroyed two enemy machine-gun nests and a mortar post, killing several Japanese and capturing much equipment. Thereafter the small group was forced to crouch all day by the western bank.

Hart attempted to aid his beleaguered men by sending out patrols to cross upstream or downstream, but they were unsuccessful. A message was therefore fired to the stranded party in a hand grenade fired from a rifle cup discharger telling them to try to return under cover of darkness. After dusk the men destroyed the captured enemy equipment (including two LMGs, one mortar and one rifle) or threw it into the river, and then tried to swim across. Jaggar was an excellent swimmer and managed to get Haly across, but two men were swirled away and disappeared. The other men crossed after being swept down the river. The platoon had lost six killed or drowned and several wounded. The pity was that, if allowed to, the platoon could have crossed without opposition on the 10th and 11th and possibly early on the 12th. It was not until the enemy had dug in on the far bank that Hart was given orders to cross. Also, if permitted to patrol extensively beyond Musom 2 on these three days, when they were chafing on the bit, Hart’s men would almost certainly have found the main enemy crossing of the Busu; and long-range patrolling was the specialty of an Independent Company.

On the 13th the sappers and the 2/24th Battalion worked very hard attempting to bridge the river for the 26th Brigade, but once again luck and the Busu were against them. By 4 in the morning another attempt at kedging had failed, but at “G” Beach an SBG and more folding boats arrived an hour later and were sent along the Burep and jeep track towards the Busu. Soon after dawn timber-cutting parties began searching for bigger logs to bridge the second stream, but although two 90-foot logs were felled and dragged to the river they were not long enough.

At 11 a.m. the sappers, supported by artillery and small arms fire, prepared to make a crossing with the small box girder and a kedge of two folding boats. Unfortunately the SBG missed the far bank by three feet, the nose twisted and the girder was washed away and lost. The SBG was retained by a tail line although the raft collapsed in midstream. At 4 p.m. more girders, which now had top priority in movement from the beaches, arrived and the sappers prepared for a more deliberate effort at night using an extra box section and counterweight.

By 11.15 p.m. the SBG was across the second stream and was being secured and decked, despite casualties caused by fire from the far bank. Reconnaissance parties from the sapper platoons led by Lieutenants Rushton59 and Kermode,60 who had been working continuously on

the crossing for about 36 hours, went over the bridge to seek a ford over the last stream and patrols returned soon after midnight to report that the third stream would need bridging by logs. The logs were dragged across the two streams while the SBG was handrailed. “2/24th Battalion becoming very impatient,” noted Dawson.

Doubtful whether a crossing would ever be made, Whitehead, early on the 13th, asked Wootten for permission to send about 120 men to cross the Busu at its mouth and advance north to secure the bank opposite the 2/24th Battalion. An hour later Lieut-Colonel Ainslie61 of the 2/48th ordered a company back by the jeep road to the mouth of the Busu. The company crossed at the 24th Brigade’s crossing at midday and began advancing north but jungle, kunai and swamp slowed progress, and communications were unsure.

Unlike the 26th Brigade, the 24th was in a position to attempt to carry out Wootten’s orders for the 13th. The 2/43rd Battalion found New Yanga unoccupied and camped for the night about half way between New Yanga and Wagan. Along the coastal track between “D” Beach and Malahang Anchorage the 2/28th Battalion was encountering stiff resistance on the 13th. The Japanese infiltrated the forward positions of the battalion soon after midnight on the 12th–13th. When the advance resumed in the morning Lieutenant Connor’s62 platoon at 11.20 a.m. encountered an enemy force entrenched at the track junction 1,000 yards east of Malahang Anchorage. Connor and Corporal Torrent63 went ahead of the platoon and attacked three foxholes. Torrent killed six of the enemy including an officer, but heavy fire prevented the platoon advancing. Because the platoon’s grenades were damp and therefore ineffective Torrent dashed back to the company and brought forward all the grenades he could carry. When he returned he found that Connor had been killed and he then assumed command of the platoon. Aided by another platoon on the right flank Torrent’s men killed twelve more Japanese. At 3.30 p.m. Torrent advanced to the track junction which the remaining enemy had abandoned, thus enabling the advance to continue.

As the division advanced the enemy hit back with his many guns stationed around Lae. On the 13th a stray 75-mm shell had killed two men including the artillery observer with the 2/23rd Battalion, Captain Henty;64 on the 14th enemy shelling increased and the idea crossed the mind of one battalion’s diarist that the Japanese might be using all their artillery ammunition in a final bombardment before withdrawing. As the enemy guns inflicted about 50 casualties on the 14th, mainly among the American amphibian engineers along the coast,65 it would be reasonable to assume

14th September

that the 22 Australian field guns66 now along the Burep would inflict equally heavy if not greater casualties.

As the 2/4th Independent Company had been unable to find a crossing north or south of the kunda bridge Captain Garvey sent his third platoon south to cross in the wake of Whitehead’s brigade. Another report about Japanese moving north along the west bank of the Busu came from Private Mannion,67 who, although wounded and marooned west of the kunda bridge on the 13th, had swum the river at its junction with the Sankwep and told of seeing 100 Japanese on the opposite track.

The troops and their leaders were understandably becoming exasperated. With Wootten urging him on from behind, Whitehead said that more attention should have been paid to his early request for an SBG, when he could have crossed without opposition. He considered that artillery was being pushed forward to do a job which could have been done with mortars. This, of course, was not an entirely just picture, but the SBG could doubtless have been hurried forward earlier.

After five days of frustration, however, the 26th Brigade was at last able to cross the Busu when the sappers finished bridging the third channel at first light on the 14th. At 6.30 a.m. the leading company of the 2/24th

Battalion – Captain McNamara’s68 – crossed the log and girder bridges, and climbed the western bank, 30 feet high. As Lieutenant King’s69 platoon began to move upstream it saw the Japanese about to enter their weapon-pits after having apparently slept in a near-by village. At the edge of the jungle the platoon was fired on and King was wounded. Lieutenant Stevens’70 platoon, moving to the South-west, was also fired on from the jungle fringe, but here the Japanese speedily withdrew in face of the Australians’ advance. Lieutenant Braimbridge’s platoon now went to the assistance of King’s, intending to outflank the northern enemy position, but its advance was stopped when heavy enemy fire from the left flank wounded Braimbridge and forced his platoon to ground.

The task of Captain Finlay’s71 company, which began to cross the river, was more difficult than McNamara’s, for the Japanese were now thoroughly alert. Supported by fire from one platoon Finlay sent the other two across; they suffered 12 casualties in doing so. Seventy yards down the third stream a signaller crossed and tied a cable to the other side. Finlay decided to continue the crossing at this point and Lieutenant Inkster72 swam across with a light rope pulling a heavier one which he attached to a tree. While Finlay and six men were tightening the rope, a mortar bomb fell among them inflicting six casualties, including Finlay, wounded.73 At 1.30 p.m. Signalman Mitchell.74 ran the gauntlet by taking a new signals line across to McNamara. For the next two hours the men of the supporting platoon dashed across singly to join the company, now commanded by Lieutenant Thomas.75 When Thomas advanced against the enemy positions four hours later he found them abandoned. The remainder of the battalion then crossed without opposition, followed by the 2/23rd and 2/ 48th.76

On the coast the 24th Brigade continued to advance against stubborn opposition. Several patrols from the 2/43rd approached Wagan on the 14th but were fired on each time. One patrol lost its two forward scouts killed by an unseen enemy when trying to encircle the village. Lieut-Colonel Joshua77 then sent Captain Grant’s78 company to capture the cross-

roads South-west of Wagan and thus cut the Japanese off from Lae, but the company met fire from a nest of machine-guns, and was unable to capture the track junction by a direct assault or by an encircling move through the dense undergrowth.

The 2/32nd Battalion entered the fight for the first time on the 14th. Relieved by the 2/17th early in the morning it set out along the coastal track. After hearing a report from Lieutenant Rice79 of the Papuan company that one of his patrols had inflicted four casualties on the Japanese who were occupying a village about half way between Wagan and Mala-hang Anchorage, Brigadier Evans instructed Scott of the 2/32nd to capture the village. While issuing orders for the advance Scott’s headquarters was shelled and Scott was slightly wounded. One and a half hours later Lieutenant Denness’80 company preceded by a Papuan section met the Japanese south of the village.

“Fixing” the enemy with one platoon, Denness sent Lieutenant Day’s81 platoon round the right flank and his third platoon round the left. Sniped at from the tree tops and from an abandoned truck Day’s platoon suffered heavy casualties, Day himself being shot through the spine. Warrant Officer Dalziel82 tried to drag him out but was killed when success seemed near. Day was then killed by a grenade and Sergeant McCallum83 took over. By this time Denness reported that the situation was “pretty warm”, and requested mortar bombardment of the well-concealed enemy positions.

Denness withdrew for the mortar shoot and Captain Davies84 company prepared to capitalise on the twelve 3-inch and ten 2-inch bombs fired. Davies formed up his company and at 4.15 p.m. Lieutenant Scott’s85 platoon went straight in on a frontal attack, supported by machine-gun fire from the flanking platoons. Meeting heavy and sustained fire after 30 yards the platoon suffered six casualties including Scott, wounded, and was pinned down on the edge of the clearing. Davies then brought up the other two platoons on the flanks. Under their covering fire, the first platoon now led by Sergeant Bell86 advanced again through the open. Seeing that an enemy machine-gun slightly to one flank was inflicting casualties Bell moved ahead of his men and coolly attacked and destroyed it.

The heavy enemy fire caused Davies to ask for support from Denness’ company, which readily came forward and supported each of the forward

platoons with one of its own. As the Japanese began to waver Bell’s platoon pushed home the attack and pursued them through the village. Lieutenant Garnsey’s87 platoon on the left had been in a better position to support Bell’s advance and the three Brens did valuable work. When Garnsey began to advance, his platoon ran into heavy machine-gun fire. Trying to silence the machine-guns Corporal Kendrick88 went forward towards them firing, but before he could reach them he was mortally wounded. When one of the Bren gunners became a casualty Private Armitage,89 who had only recently joined the battalion, took over the Bren and kept it in action. The platoon then advanced, mopping up snipers, as well as fowls destined for the cooking pot.

At dusk the two companies had captured the village and road to the west and dug in south of the road and track junction. In a very creditable introduction to jungle warfare the 2/32nd Battalion had killed at least 70 Japanese for the loss of 33 casualties, including 10 killed. “It would seem,” wrote the battalion diarist, “that the rising sun has moved to the western sky insofar as Lae is concerned.” He did not know how right he was.

Advancing towards Malahang Anchorage on the 14th Norman of the 2/28th planned to give the impression of continuing along the coast with one company (Newbery’s) while the other three infiltrated to cut the road behind the Japanese. Patrols to find routes for the three company attacks set out soon after first light. At 9.15 a.m. Lieutenant Hindley’s90 patrol killed 12 Japanese without loss and at 12.40 p.m. it killed another 14. Lieutenant Hannah’s company found two abandoned 75-mm dual-purpose guns north of the anchorage early in the afternoon. By 3.50 p.m. the two leading encircling companies (Hannah’s and Lyon’s) were in position after passing through difficult country and suffering a few casualties from sporadic enemy fire. Newbery’s company edged forward to the eastern side of the anchorage against determined opposition at a bottleneck between the sea and a creek. As the company found it almost impossible to encircle this position, Norman ordered its withdrawal. North of the anchorage the other three companies were astride the road by dusk. By sheer tenacity they had infiltrated round the enemy positions through swamp and virtually sealed the anchorage’s fate.

At Nadzab the aerial build-up continued; 165 planes arrived on the 13th and 106 on the 14th. General Vasey ordered Brigadier Eather to continue the advance on Heath’s Plantation on the 13th. Eather gave his battalion commanders their tasks: the 2/25th would apply pressure to Whittaker’s Plantation at daylight; the 2/33rd would move round the

south, establish a road-block at Heath’s and advance back towards Whittaker’s; and the 2/31st would be prepared to lead the advance on Lae, once this opposition was overcome. By last light on the 12th Captain Gow’s company of the 2/25th had moved round the left flank of Major Robertson’s, at the track and road junction North-west of Whittaker’s. Early on the 13th Colonel Marson ordered Gow’s company followed by Captain W. G. Butler’s to advance through the overgrown plantation on a compass bearing for Heath’s and to hit the enemy with everything they had.

Half an hour later (8.30 a.m.) Robertson’s company began to advance warily down the Markham Valley Road, and at 9.30 a.m. it met a strongly-entrenched enemy force at Whittaker’s bridge. It was pinned down although Sergeant Jones’91 platoon on the left of the bridge was able to report enemy movements. Robertson called for artillery support but Lieutenant Stokes, the forward artillery officer, protested that the Australians were too close to the Japanese and that artillery fire would be dangerous. Robertson replied, “We are well dug in; have a go at it, you’ll do them more damage than you will us.”92 Several shells were fired but when one dropped short Stokes told Robertson that he would have to find some other way to knock out the enemy position. Robertson tried a mortar, but because he was so close to the bridge he found that even more dangerous than the gun.

The two northern companies moved slowly through difficult country cut by small streams. For the first time each company had walkie-talkie sets which enabled them to keep in touch with one another during their advance. Soon some well-beaten enemy tracks were crossed and the general air of tenseness reflected the knowledge that trouble might break at any moment. When the leading platoon (Lieutenant Howes93) reported that the going was becoming rougher, Gow reluctantly forsook the higher ground and swung down towards the Markham Valley Road through a re-entrant. A few minutes later Japanese voices were heard ahead. The platoon advanced for about 50 yards feeling very exposed in an avenue between cocoa trees. Soon after 10 a.m. two sections were pinned down by fire, having suffered casualties. The third section (Corporal Francis’94) then attacked but was held up. Francis seized the Bren from his mortally wounded gunner and relieved some of the enemy pressure before he too was wounded. With his whole platoon pinned down Howes requested assistance on his left flank where the opposition was heaviest.

Gow sent Lieutenant Burns95 platoon to attack on Howes’ left. The leading section under Corporal Richards96 fanned out in an extended line

while Burns’ second section under Corporal Sawers97 filled the gap between Richards and the platoon on the right. When both these sections met heavy fire Burns sent his third section (Corporal Duckham98) in on the left flank and adjoining the track which cut the Markham Valley Road. Soon this section also was pinned down.

Gow tried again and sent in his last platoon (Lieutenant Macrae99) on Burns’ left, along a ridge from which the heaviest fire was falling on the two other platoons. Whereas the two leading platoons had struck the enemy’s forward defences, Macrae entered through the “back door” and attacked what appeared to be the Japanese headquarters. Sergeant Hill100 killed three Japanese as the platoon cleared the ridge and wiped out one machine-gun post. As Gow had now run out of troops Marson placed one of Butler’s platoons (Lieutenant Howie101) under his command to move along the ridge to the right of Howes and clear out the enemy.

Meanwhile, the two pinned platoons were doing their best to wipe out the opposition ahead. Burns’ platoon had suffered eight casualties including one section commander, Corporal Sawers, killed and another, Corporal Richards, wounded. Richards was lying out in front down the forward slope of a small rise and was doing his best to observe the enemy machine-guns and direct fire at them.

During this time Privates Kelliher102 and Bickle103 were lying in a dip. Kelliher said to his companion, “I’d better go and bring him [Richards] in.” Hurling his and Bickle’s last grenades at the machine-gun post he killed some of the enemy but not all. He then grabbed a Bren gun from a wounded gunner and dashed forward firing until the magazine was emptied. Returning he got another magazine, went forward again, fired it from a lying-down position and silenced the machine-gun post. Under fire from another enemy position Kelliher then carried the wounded Richards to safety.104

Entering the fight on Gow’s right flank in the wake of Howie’s platoon, Butler’s company attacked down the ridge in a South-westerly direction towards the main track in the early afternoon. Against stiff opposition the company made only slight progress before being stopped; it dug in for the night in a plantation drain with one platoon about 50 yards from the Markham Valley Road. The two companies were about half a mile east of Robertson’s company at Whittaker’s bridge. The battalion had

13th September

suffered 26 casualties on the 13th, including 10 killed, but it was estimated that the Japanese had lost about 100. Gow’s wounded were carried out on stretchers at night by the light of lanterns.

During the afternoon while both companies were slowly inching forward it became evident that Macrae had overrun an important headquarters. In one hut was a wireless set, and other equipment captured included a machine-gun and a bullet-proof vest. More important, some documents and maps were captured. Macrae sent these to Gow who noted that one map of the Markham Valley and Lae showed markings which appeared to be enemy positions. From this he judged the documents to be important and sent them rapidly back through various channels to translators where “a most uninteresting paper in appearance”, as Gow called it, caused no little excitement.

It was not until after midday when Macrae’s platoon had captured the Japanese headquarters that Eather gave the 2/33rd Battalion the green light to find a route round the right flank into Heath’s. Lieutenant Nielson105 then led a patrol through the dense overgrown plantation seeking a suitable route, while the remainder of the battalion prepared to move forward.

Patrols from the 2/2nd Pioneers were very active on the 13th. One of them, led by Lieutenant D. O. Smith, cut a track north from the Markham towards the Markham Valley Road and near Edwards’ Plantation. Another, led by Lieutenant Hulse, cut a track north towards Heath’s. By 10.45 a.m. Hulse’s patrol was close to Whittaker’s, and at 3.30 p.m. it entered Heath’s, deserted except for Nielson’s patrol from the 2/33rd Battalion. Both patrols found Heath’s devastated by aerial bombardment.

By 4 p.m. Nielson returned to his battalion having found a suitable route to Heath’s while Hulse combed the area collecting documents.

Hulse’s patrol was followed into Heath’s by Colonel Lang and three men. When he realised that the patrol had cut off the enemy who were bitterly defending the Whittaker’s area against the 2/25th, Lang decided to occupy Heath’s for the night and summoned Lieutenant Coles’106 platoon. Before it could arrive Hulse’s patrol was attacked by a small enemy force from the west. Largely due to the reports of Lance-Corporal Egan,107 who climbed a tree in full view of the enemy, Hulse was able to repulse this enemy force surrounding him on three sides. The Japanese approached within 50 yards of Egan’s tree but he emulated many Japanese snipers before him by shooting the leading enemy and driving the others to cover. Soon Coles’ platoon arrived and occupied Heath’s for the night.

For 14th September General Vasey ordered the capture of Edwards’ Plantation. At 6 a.m. a patrol led by Corporal Duckham from Gow’s company joined Robertson’s company and reported no Japanese in between. After an artillery bombardment Robertson’s company moved forward and found no Japanese at Whittaker’s bridge. Much equipment was found, including 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, 37-mm anti-tank guns, heavy machine-guns, 85-mm mortars and a large quantity of ammunition and stores, some still in grease packing. By this stage Brigadier Eather was confident that the Japanese were pulling out and urged greater speed. He overtook the leading company in his jeep, and, finding the pace too slow, ordered Robertson to withdraw his flanking patrols and push on. By 8.30 a.m. Robertson joined Coles’ platoon of Pioneers in Heath’s Plantation, which had not been entered by the Japanese in their withdrawal from Whit-taker’s. Robertson continued to advance; half an hour after entering Heath’s his leading platoon commander, Lieutenant Weitemeyer,108 was killed by fire from an enemy position at Lane’s bridge.

By 10.15 a.m. the 2/33rd had passed through the remainder of the 2/25th at the junction of Heath’s Track and the Markham Valley Road. As Cotton had only three rifle companies because of the disaster to the fourth one at Port Moresby, Eather directed Lang to lend a company to Cotton. After relieving Robertson’s company of the 2/25th near the bridge, Cotton decided to encircle the enemy position and sent one company to the right and one to the left. The third infantry company also moved round to the left in support; and Captain Garrard’s company of Pioneers took over near the bridge. Soon after midday, as the companies began to close in, Lieutenant Carroll109 of the 2/4th Field Regiment directed the shelling of the bridge position for 20 minutes. For the next 15 minutes Mitchells strafed the track ahead of the 2/33rd. It was difficult for artillery or aircraft to bombard accurately such a Japanese position which,

like most defensive positions in the plantations area, was situated among the jungle-clad foothills of the Atzera Range.

The attacking companies helped to bring the Japanese casualties inflicted by the 25th Brigade to about 300. South of the road Lieutenant Johnston’s110 platoon was held up by machine-gun fire. When Johnston was wounded the company commander’s batman, Private Burns,111 dashed to his aid under heavy fire and dragged him to safety. On the northern flank another platoon commander, Lieutenant Scotchmer,112 was wounded, but by 1.30 p.m. the Japanese were driven from their positions on the bridge.

Determined to maintain the pressure on the retreating enemy Cotton sent two infantry companies (Captains Weale113 and H. D. Cullen) and Garrard’s company of Pioneers to maintain contact. At 2.50 p.m. the leading portions of these three companies met another enemy force at the southern turn of the Markham Valley Road west of Edwards’. Mainly on the northern side of the road the companies fought a very heavy engagement watched by General Vasey who liked nothing better than to leave his headquarters and watch the fight from the front line. Again and again in New Guinea campaigns Australian troops were cheered by the sight of Vasey’s conspicuous red cap in the front line with them.

A very troublesome machine-gun was holding up the Pioneers’ advance until Corporal Hucker114 moved ahead of his platoon and turned the tables on the Japanese by pinning them down with his Bren. Under cover of his fire his platoon found a more favourable position and was able to destroy the pocket of resistance. Weale’s and Garrard’s companies were now very heavily engaged. Cotton sent orders to Cullen to attack forthwith across the track to assist the other companies. Cullen led his company in a dashing attack to drive the Japanese from their point of vantage. By 4.15 p.m. the Japanese, yelling but unable to withstand the constant pressure, withdrew, leaving a large amount of equipment behind.