Chapter 1: The Final Phase Begins

IN August and September 1944 the Allied Staffs expected organised German resistance to collapse before the end of the year, but by October it was evident that this hope would not be realised, and that the German Army would survive into the summer of 1945.1 At the beginning of December General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Allied armies had reached the upper Rhine, the Russians were at Warsaw, Budapest and Belgrade, and in Italy an Allied army was pressing towards the Po. There were some 70 Allied divisions on the Western Front and soon 87 would be deployed for the final offensive; in Italy some 24 Allied divisions faced 27 German and Fascist divisions. About 180 Russian divisions, many greatly depleted, were along the Eastern Front.

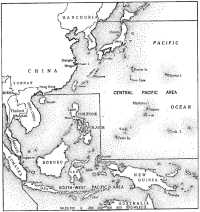

In the Far East Japanese armies in Burma were being thrust back from the Chindwin River and were carrying out a successful offensive against Allied airfields in south China; elsewhere their forces had suffered severe defeats. In September 1944 the advance of the Allied forces in the South-West and Central Pacific had reached Morotai, the Palaus and the Marianas. South of this line three Japanese armies lay isolated: one in New Britain, New Ireland and Bougainville; one on the mainland of Australian New Guinea; and one in Dutch New Guinea. The next Allied moves were to be an attack by General Douglas MacArthur’s South-West Pacific forces against Mindanao, and by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Pacific Ocean forces against Yap. On 13th September, however, while the British and American leaders were at Quebec considering plans for the defeat of Japan, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff received through Admiral Nimitz a proposal by his subordinate, Admiral William F. Halsey, that Halsey’s attack on Yap and MacArthur’s on Mindanao be cancelled and instead MacArthur should invade Leyte not on 20th December as planned but as soon as possible. Halsey proposed that his XXIV Corps, then embarking at Hawaii to attack Yap, should be placed at MacArthur’s disposal to help on Leyte.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff sought MacArthur’s views. He was then in a cruiser watching the invasion of Morotai and wireless silence was being preserved. However, his staff sent a reply to the Joint Chiefs in MacArthur’s name stating that he was willing to land on Leyte on 20th October. Thus on 19th October an immense fleet, including six capital ships, 18 escort aircraft carriers, 258 transports and a multitude of smaller craft, was off the coast of Leyte, with the large aircraft carriers in support. The transports carried the Sixth American Army, then comprising two corps.2

The American plan was to land X Corps (1st Cavalry and 24th Divisions) near Tacloban on the north-east coast and XXIV Corps (7th and 96th Divisions) at Dulag farther south. Between these two towns were four airfields. The defending force in the Philippines was commanded by General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Fourteenth Area Army whose headquarters were at Manila, where Field Marshal Count Terauchi commanding the whole Southern Army had also established his headquarters in April 1944.3 Yamashita controlled in Luzon an army of four divisions, and in the southern islands the XXXV Army, with the 16th Division on Leyte, 30th and 100th on Mindanao, and the newly-constituted 102nd distributed among the islands to the west. The defenders of Leyte numbered about 27,000.4

There was little opposition to the landing because the Japanese had decided to withdraw their main forces from the beaches and concentrate for a counter-attack. They delivered fairly heavy attacks on the beachheads in the first few days, and then opened a counter-offensive on an imposing scale: their main fleet arrived in the western Philippines with the object of sending its main force through San Bernardino Strait and a smaller force through Surigao Strait to destroy the American convoys, while at the same time a diversionary force steamed south from Formosa. On the 24th the opposing carrier-borne aircraft clashed, an American cruiser was mortally hit and a Japanese battleship sunk. That evening the diversionary force was sighted and Admiral Halsey set off in pursuit with his main force. In the night the American Seventh Fleet decisively defeated the Japanese force thrusting through the Surigao Strait, but San Bernardino Strait was left unguarded as a result of Halsey’s departure northward, and the main Japanese fleet passed through unnoticed and descended upon Vice-Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, whose only carriers were of the small escort type. The Japanese battleships sank one carrier, and their aircraft and a submarine damaged other ships, but American carrier aircraft attacked vigorously. The Japanese admiral, overestimating the force opposing him, turned northward just when, in the opinion of the American admirals, a resounding success was within his grasp. In response to Kinkaid’s appeals Halsey broke off and turned south but was too late to intercept the main Japanese battleship force before it steamed back through San Bernardino Strait.

The heavy bombers now took up the pursuit and sank and damaged some vessels. In the various engagements the Japanese had lost 3 battleships, 4 carriers, 10 cruisers, and 11 destroyers. The Americans had lost 3 carriers and 4 smaller warships. It was a great but not an overwhelming victory. Indeed Japanese suicide aircraft now began to cause keen anxiety.

South-West Pacific Area, December 1944

On the 29th and 30th they severely damaged three carriers; and from 29th October to 4th November delivered heavy attacks on the invaders’ ships and airfields, and continued to strike although in dwindling force in the following weeks.

Meanwhile the Japanese had brought forward army reinforcements and by 11th November had put ashore on Leyte all or most of the 102nd Division, the 30th, the 1st and the 26th (the last two from China). MacArthur landed the 32nd American Division on 14th November and the 11th Airborne and 77th by the 23rd, and thus had seven divisions ashore to oppose five Japanese.

The movement of these troops to Leyte had cost the Japanese heavily in transports and naval vessels sunk by air attack, and after bringing in part of their 8th Division from Manila early in December they ceased trying to reinforce. By the fourth week of December the Japanese army on Leyte was disintegrating. At that stage the Japanese losses were estimated at 56,000 killed; the Americans had lost 3,049 killed or missing.

The American and British Navies now dominated both the Pacific and Indian Oceans and, within the range of their aircraft, the skies above. Of 12 battleships which Japan had possessed when war began or had completed since, only 5 remained; of 20 aircraft carriers (excluding escort carriers) only 5; of 18 heavy cruisers only 6; of 22 light cruisers only 5. The United States Navy on the other hand had greatly increased in the past three years, and possessed, in December 1944, 23 battleships, 24 carriers, 16 heavy and 42 light cruisers. Most of these ships were in the Pacific, where the Australian Navy added a contingent of 4 cruisers and considerable flotillas of smaller ships. A British Pacific Fleet, including the two most modern British battleships and 4 large carriers, was now based on Ceylon.

In the Pacific, up to December 1944, 30 Allied divisions had been in operations – 23 American divisions (including 4 of Marines), 6 Australian and one New Zealand. In Burma 13 British Empire divisions – 8 Indian, 3 African and 2 British – were deployed, and there were 4 small Chinese divisions with 2 American regiments attached. The armies of General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz, now poised for the final blows, were together about one-third as large as General Eisenhower’s in France would soon be; Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten’s in north Burma about half as strong as Field Marshal Alexander’s in Italy.

In November American long-range bombers from bases in the Marianas had thrice attacked Tokyo. As bases closer to Japan were seized and developed, such attacks on Japanese cities would be intensified. Some American leaders hoped that the destruction of cities from the air might persuade the Japanese Government to surrender before American lives had been lost in an assault on the Japanese mainland.

The success of the Allied operations in Europe had brought to the fore the question of re-deploying the British forces once the first main strategical

objective – the defeat of Germany – had been achieved. To record the discussions and plans concerning the roles of this and other forces in the Pacific in 1945 it is necessary to go back to 1943. In South-East Asia, then and later, the main military burden was being carried by Indian troops; in the South-West Pacific during 1942 and 1943 by Australian troops and, since the first quarter of 1944, by Americans. If Germany soon collapsed where could room be found in the Asiatic war for forces flying the Union Jack? Preparation of detailed plans for a redeployment of British forces had begun in London in 1943, and the question had been debated and finally decided during 1944.

In September 1943 when the surrender of the Italian Navy made it possible soon to employ the greater part of the Mediterranean Fleet elsewhere, the British Prime Minister, Mr Churchill, was in the United States. He suggested that the Eastern Fleet in the Indian Ocean should be reinforced and, as a first step, that the reinforcements should proceed through the Panama Canal to the Pacific and there spend at least four months gaining experience under American orders.5

As a result of discussions at an Allied conference in Cairo in November 1943 the British Chiefs of Staff decided that as soon as possible after the defeat of Germany, then assumed for planning purposes to have taken place by 1st October 1944, the British Fleet should be sent to the Pacific – the main theatre of operations against Japan – and that they should aim at providing also four British divisions based on Australia for service in the Pacific zone. The main British effort on land in 1944 would be made, however, in South-East Asia.

On 30th December the British Chiefs drafted a telegram describing these plans for the information of the Australian and New Zealand Governments and sent it to Mr Churchill, then in Morocco, for approval. This opened “a long and complicated debate which was to end only in September 1944, after involving the Prime Minister and the British Chiefs of Staff in perhaps their most serious disagreement of the war”.6 It is briefly recorded here because from time to time the Australian Government and its military advisers were involved.

Mr Churchill wished the main British effort to be made from the Indian Ocean against Malaya and the Indies. He contended that a Sumatran operation offered greater promise than the plan for sending the British forces to the Pacific. Incidentally he suggested that to base the forces on Australia would involve excessively heavy demands for shipping. Churchill was strongly supported in his insistence on concentration in the Bay of Bengal by the Foreign Office which, on 21st February, presented a memorandum which concluded that

if the [Pacific] strategy ... is accepted, and if there is to be no major British role in the Far Eastern war, then it is no exaggeration to say that the solidarity of the

British Commonwealth and its influence in the maintenance of peace in the Far East will be irretrievably damaged.7

On the other hand, so far as Australia was concerned, the Prime Minister, Mr Curtin, had made it known to visiting British authorities late in November 1943 that he hoped to see Britain represented in the Pacific, and had caused them to believe that he would welcome the formation of a British Commonwealth Command in the South-West Pacific as a partner to the American command there; or alternatively that the boundaries of South-East Asia Command might be revised to include part of the South-West Pacific Area and Australian forces included in Admiral Mount-batten’s command.8

On 3rd March Churchill sent the members of the Defence Committee a memorandum9 (dated 29th February) clearly setting out the problem. In the course of it he wrote:

The two alternatives open are:

A. To send a detachment of the British Fleet during the present year to act with the United States in the Pacific and to increase the strength of this detachment as fast as possible, having regard to the progress of the war against Germany. This fleet would be followed at the end of the German war, or perhaps even before it, by four British divisions which would be based on, say, Sydney and would operate with the Australian forces on the left or southern flank of the main American advance against the Philippines, Formosa and ultimately Japan. ...

B. To keep the centre of gravity of the British war against Japan in the Bay of Bengal for at least 18 months from now and to conduct amphibious operations on a considerable scale against the Andamans, Nicobars and, above all, Sumatra as resources become available.

The British Chiefs of Staff favour “A”, and made an agreement at Cairo after brief discussions with the United States Chiefs of Staff that this should be accepted “as a basis for investigation”. Neither I nor the Foreign Secretary was aware of these discussions, though I certainly approved the report by the Combined Chiefs of Staff in which they were mentioned.

Admiral Mountbatten and the South-East Asia Command are in favour of “B”, which is perhaps not unnatural since “A” involves the practical elimination of the South-East Asia Command and the immediate closing down of all amphibious plans in the Bay of Bengal.

Churchill added that the Chiefs of Staff considered that British forces based in Australia would be a valuable contribution to the main American operations and would “produce good results upon Australian sentiment towards the Mother Country”, and that successful operations in the Pacific would cause Malaya and the Indies to “fall easily into our hands”. On the other hand, he pointed out, the Pacific strategy would involve the division of British forces, would place out of offensive action very large forces in the Indian theatre, render idle big bases there and in the Middle East and vastly lengthen the British line of communication. Mr Churchill pointed also to a difficult political question concerning the future of

Britain’s Malayan possessions. “If the Japanese should withdraw from them or make peace as the result of the main American thrust, the United States Government would after the victory feel greatly strengthened in its view that all possessions in the East Indian Archipelago should be placed under some international body upon which the United States would exercise a decisive control. They would feel with conviction: ‘We won the victory and liberated these places, and we must have the dominating say in their future and derive full profit from their produce, especially oil.’ Against this last the British Chiefs of Staff urge that nothing in their plan excludes our attacking the Japanese in Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies in due course from the Pacific.”

Churchill added that he would ask President Roosevelt whether American operations in the Pacific really required a detachment of the British Fleet there in 1944 and 1945. He himself deprecated “a hasty decision to abandon the Indian theatre and the prospect of amphibious operations across the Bay of Bengal”.

The Chiefs of Staff, in a memorandum presented five days later, expressed disagreement with Churchill’s definition of the alternatives. To them it was a choice between a Pacific strategy aimed at obtaining a footing in Japan’s inner zone at the earliest possible moment and a Bay of Bengal strategy that could not begin until about six months after Germany’s defeat and would be an independent British contribution to the war against Japan. Whatever contribution Britain made, the major credit for the defeat of Japan would go to the Americans. A deadlock seemed to have been reached. General Ismay, Mr Churchill’s Chief of Staff, on 4th March warned Churchill of the danger that the Chiefs of Staff would resign, an event that would be “little short of catastrophic” on the eve of the invasion of Europe.

The Australian Government, meanwhile, was wondering what was being done about the decisions reached at the Cairo conference in November, and Mr Curtin sent an inquiry to Mr Churchill on 4th March. Churchill called a conference for 8th March to decide on a reply to this embarrassing question. As a result, on the 11th, Churchill sent a telegram to Curtin in which he said that two broad conceptions were being examined: one that the main weight of the British effort should be directed across the Indian Ocean and brought to bear against the Malay barrier in a west to east thrust using India as the main base; the other that the bulk of the naval forces, together with certain land and air forces, should operate from east to west on the left flank of the United States forces in the South Pacific, with Australia and not India as their main base. He added that before reaching firm conclusions the relative base potentialities of India and Australia should be known, and suggested that Britain should send small parties of administrative experts to Australia.

This proposal ran counter to a principle which the Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Army, General Sir Thomas Blamey, had maintained since 1942, not always with success, that it was not in accordance with long-accepted principles of Imperial defence for one partner in the British

Commonwealth to send independent staffs on military missions to another partner. He considered that such staffs should be integrated into the local staff. The main liaison groups between the South-West Pacific forces (and the Australian Army in particular) and the War Office were then a liaison staff with the Australian Army headed by Major-General R. H. Dewing, and Mr Churchill’s personal representative at General MacArthur’s headquarters, who was Lieut-General H. Lumsden. The Dewing mission had been appointed in November 1942. Blamey had then objected to it on the ground mentioned above, and on other grounds. In November 1943 he had written to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Brooke, on the subject. The letter said:

I have been somewhat disturbed of late at the trend of relationships between the Headquarters of the various military forces of the Empire, and particularly between ourselves and WO. These relationships were laid down originally at the Imperial Conference in 1909, and had been developed steadily until recent years. The pivot of all our relationships was the Imperial General Staff, and although this conception has tended to weaken, the results of its formation still remain, to the immense advantage of the whole of the forces of the Empire.

The main principles that have been enunciated under the aegis of the Imperial General Staff, and determined at various Imperial Conferences, have led to the development of the Empire land forces on identical lines. The result is that throughout the Empire the Army has a common doctrine of war; a common system of organisation, both in relation to the command and staff system, and the organisation of units and formations; common principles and methods of training; and common equipment. The immense advantages of these were demonstrated in the first world war, and again when Empire forces were assembled in Egypt and in Britain in the early days of the present war. Unless the key centre from which these principles radiate, namely, the Imperial General Staff, is maintained, the tendency to drift into differences, already noticeable, will become more and more accentuated. This I believe will be greatly to the detriment of the Imperial Forces jointly and separately.

The tendency in our relations now is to organise Military Missions as opposed to the General Staff conception. While the establishment of Military Missions is probably as good an arrangement as can be made between allied countries, I am perfectly certain that the advantages of combined staffs, of which the Imperial General Staff is the main trunk for the Empire, is a much better solution, and will give greater strength and cohesion to the British Forces, and will ensure the maintenance of the principles already agreed upon at Imperial Conferences.

It is not possible for a Military Mission to get inside the thought of the forces of the country to which it is allocated, because it is itself external to the thinking organisation of the forces of that country. The only way to reach the highest plane in military relationships, for representatives of one portion of the Empire serving in any other part, is to ensure that they shall be part of the organic whole of that portion of the Empire in which they may be employed.

It is probable that Australia was the first to cause a crack in the true relationship. This was due to the fact that it was necessary for us to maintain an agency in England for the procurement of equipment. ... In its original conception this mission was an off-shoot and was under the control of the Australian representative of the Imperial General Staff at the War Office. Its development, however, has been somewhat away from this.

When Major-General Dewing made a short visit to England, I discussed with him the nature of the British Military Mission here. I have no doubt that he told you that I expressed my opinion as adverse to the change from the Imperial General Staff conception to that of the Military Mission. I also discussed with him – and I understand he raised with you – the question of whether it might be possible to allocate one or two senior officers about the rank of Brigadier from UK to

Australia, and reciprocally from Australia to UK On mature consideration, however, I do not think that such an arrangement is convenient with the existence of Missions charged with the function of representation, as such officers would find themselves owing allegiance locally to two masters.

The matter has again come to the fore owing to the decision of the Australian Government to establish a High Commissioner in India. Lieut-General Sir Iven Mackay, who has been chosen for the appointment, has asked for a Military Attaché on his staff. I am opposing the suggestion as I feel sure that the present direct communication as between Armies is much more elastic, rapid and confidential than the allocation of a Military Attaché to the High Commissioner could ever be. Moreover it introduces a further centrifugal move at a time when we should be drawing together.

Our tendency at present is to shape our ends in a manner more suited to allied forces rather than to the forces of an entity of which we are integral parts, and I feel that we are going on diverging instead of converging lines.

I should be very glad to hear your views on the matters in question, for I am strongly persuaded that the more closely bound are the Empire forces during the war, the more unified will be the outlook of the Empire Governments in determining matters of common interest in the post-war period.

The letter illustrates two trends in Blamey’s thinking, consistently maintained in these years: first, that the United Kingdom and the Dominions should cooperate in military affairs as close and equal partners; second, that the links between the forces of the Empire should not be weakened as an outcome of intimate wartime association with those of the United States.

Brooke deferred a firm expression of opinion on the problem Blamey had raised until it had been discussed by the Dominion Prime Ministers at a meeting to be held early in 1944.

After consulting Blamey, the Chiefs of Staff and MacArthur, Curtin replied to Churchill’s telegram of 11th March that substantial information about facilities in Australia had already been provided by them to the Admiralty, War Office and Air Ministry, detailed information had been supplied to the Lethbridge Mission,10 and other sources of information were readily available through the Australian Service representatives in London and the United Kingdom Army and Air Force Liaison Staff in Australia.11 The experience of the Australian Staffs in providing base organisations and maintenance for large forces on the mainland and in New Guinea should enable them, in collaboration with the United Kingdom Liaison Staff, to prepare tentative plans. United Kingdom representatives would be welcome but it might be preferable to defer them until plans had progressed further when “best results would probably be obtained by sending representatives of the staffs and advance parties of the Forces concerned”. General MacArthur would gladly furnish any opinions that might be desired on the operational aspect of base potentialities of Australia and the operation of forces therefrom. Curtin concluded:

British forces could ... operate in the South-West Pacific Area only by being assigned to the Commander-in-Chief in accordance with the terms of his directive. A separate system of command could not be established. Furthermore, the base

facilities on the mainland are under the control of the Commander, Allied Land Forces, who is also Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces, the Australian Chief of the Naval Staff and the Australian Chief of the Air Staff ... information should be furnished by these sources and the administrative experts sent to Australia should be attached to the staffs of the respective Australian Services.

Blamey, who foresaw the possibility that the United Kingdom leaders might wish to establish a separate command in the area, was the main author of this final paragraph.12

On 30th March the Australian Army Representative in London, Lieut-General Smart,13 cabled to Blamey’s Chief of the General Staff, Lieut-General Northcott, that the general effect of the Australian reply was thought in London to be somewhat discouraging; it was realised that existing machinery could provide the necessary information but it would be of value to have British officers in London who had seen Australia and discussed the problem on the spot. He understood that it was now proposed to send smaller parties to confer with Australian commanders and with General Dewing.

On 13th March President Roosevelt had replied to Mr Churchill’s inquiry, mentioned earlier, by saying that there would be no operation in the Pacific in 1944 that would be adversely affected by the absence of a British Fleet detachment, and it did not appear that such a detachment would be needed before the (northern) summer of 1945. He added the opinion that, in view of a recent move of the Japanese main fleet to Singapore,

unless we have unexpected bad luck in the Pacific your naval force will be of more value to our common effort by remaining in the Indian Ocean.

On 20th March Churchill ruled that the Bay of Bengal policy must be maintained and a reconnaissance mission sent to Australia to study potential bases. The Bay of Bengal policy received a rebuff, however, on 21st March when the American Chiefs of Staff stated that once their forces had succeeded in the Formosa–Luzon area the strategic value of operations in Malaya and the Indies would be reduced, and they could not agree to support an operation against Sumatra or any similar operation involving large amphibious commitments in the South-East Asia Command.

The Americans’ views were influenced by their wish to establish in China a strategic air force which would bomb Japan and its approaches; to them the Bay of Bengal policy seemed a move in the wrong direction and one which might divert resources from the thrust towards China from northern Burma. They proposed that the Combined Chiefs should order Admiral Mountbatten to concentrate on seizing certain bases in northern Burma before the monsoon. The British Chiefs of Staff disapproved of the Sumatran operation, but had no faith in operations towards China.

Admiral Mountbatten said that he did not think that the operations proposed by the Americans would succeed. Complex discussions followed; the American Chiefs were not persuaded.

Early in April a most unpractical policy came under detailed consideration in London: the joint planners were told to investigate the possibilities of establishing bases in northern and western Australia and “the general strategic concept of an advance on the general line Timor–Celebes-Borneo–Saigon”. Within a few days this request in similar but not identical terms reached the planners from both the Prime Minister and the Chiefs of Staff independently.

Thus there were now four proposals in the field: the American leaders wished the main British effort in Asia to be in northern Burma and towards China, in whose military potentialities they had great faith; the British Prime Minister demanded concentration on an eastward drive against the lost colonies of Malaya and the Indies; the British Chiefs of Staff wished a strong British task force to join the Americans in the Pacific; both Churchill (to whom the Chiefs of Staff would not yield) and the Chiefs of Staff (whose plan was not welcomed by the American Chiefs) were now considering a compromise plan – a thrust northward from north Australia.

For planning purposes the target date for this “middle strategy” was fixed at March 1945. The tentative plans provided for an advance to Ambon, by-passing Timor, thence to northern Borneo, perhaps via Menado in Celebes, and on to either Saigon and Malaya or Hong Kong and the China coast at the end of 1945 or early in 1946. The planners pointed out, however, that northern Borneo could be gained more quickly and more economically by passing north of New Guinea and using staging points and sea communications already in Allied hands. Thus there was now a fifth possible policy: an advance to Borneo along the established South-West Pacific route.

The inquiry whether India or Australia had most to offer as the main base was proceeding. The British Chiefs of Staff still wished to send their own missions to examine Australian potentialities. And the Admiralty had already sent Rear-Admiral C. S. Daniel and a staff to the South-West Pacific Area, but Curtin’s cablegram of 22nd March caused Churchill to delay Daniel’s arrival and it was not until 28th April that he was given permission to make the last lap of his journey to Australia.

At this stage consideration of the proposal to send a larger United Kingdom group to make inquiries in Australia was postponed until the conference of Dominion Prime Ministers was held in London early in May. General Blamey accompanied Mr Curtin to London and, on 5th May he, Admiral Sir Ragnar Colvin and Air Vice-Marshal H. N. Wrigley discussed the problem of the British contingent for the Pacific with the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff.14 Blamey and his staff tried to find out what the British intentions were, but without much success at that stage.

It was pointed out by the British Chiefs that no British forces could reach the Pacific area before 1945. General MacArthur considered that, after the recapture of the Philippines, the American Navy would control the advance towards Japan while he advanced westward to Borneo. The correct strategy in this phase might be a converging offensive through the Strait of Malacca and across the Bay of Bengal; another possible pincer movement might be developed by other forces under MacArthur operating from north and north-west Australia by way of Timor.

Blamey informed the conference that probably six Australian divisions would be required in forthcoming operations, three to capture Halmahera and three to occupy New Guinea. The British Chiefs of Staff expected that some six British divisions and about 20 air squadrons would be available for the Far East after the collapse of Germany.

At a meeting of the Defence Committee on 10th May a detailed statement of the British forces available for a Pacific strategy and the estimated dates on which they would become operational (assuming that Germany had been defeated by the end of 1944) was presented. It pictured a fleet of 4 battleships, 4 fleet carriers, 10 cruisers and corresponding other vessels being operational late in 1944, and being increased to a fleet of 6 battleships, 5 fleet carriers, 5 light carriers and 25 cruisers late in 1945. Two infantry divisions might arrive from India in January and March 1945 and 3 from European theatres in February, March and April 1945 respectively. The air force would eventually contain 157 squadrons, including 63 RAAF squadrons (among them being 11 Australian squadrons from Europe and the Middle East), 16 RNZAF, and 78 RAF squadrons.

In these discussions three main considerations were uppermost in the minds of the Australian leaders: the desire to have Great Britain strongly represented in the Pacific, a resolve not to upset the command arrangements developed in the past two years, and anxiety lest plans should be made that were beyond the capacity of Australia’s manpower.

On 17th May Curtin, in a memorandum to Churchill, raised “the question of the procedure to be followed in order to resolve this question, which is of vital importance to British prestige in the Pacific and to the form and nature of the Australian war effort”. Australia did not possess the manpower and material needed to meet all the demands being made on her. He instanced the fact that, at October 1943, United States demands were involving the employment of 75,000 Australians and the figure was expected to reach 100,000 by June 1944; reciprocal Lend-Lease would reach nearly £100,000,000 in 1944. It was presumed that if additional forces were sent to Australia the United Nations would make good the deficiencies which Australia could not supply. The first step, he added, should be a decision by the Combined Chiefs whether the proposed additional forces were to be sent to the Pacific. If they were, Australia would have to begin planning, particularly planning food production. Finally he noted that any variation of the decision whereby the Australian forces had been assigned to the Commander-in-Chief, South-West Pacific

Area could be made only on the recommendation of the Combined Chiefs of Staff and with the approval of the Australian Government. Meanwhile Admiral Daniel on 10th May had cabled to the Admiralty that he could see no reason why the whole proposed naval force could not be supported by Australia by mid-1945.

On 22nd May the British Chiefs of Staff agreed with Blamey that the British reconnaissance parties to go to Australia should be integrated with the Australian Staff and not operate as an independent mission. These parties were to include 17 naval officers, 12 army officers and 4 RAF officers, including those already in Australia.

Mr Curtin had taken with him to London and Washington a proposal that the combat forces of the Australian Army should be reduced to six infantry divisions and two armoured brigades. General MacArthur had already agreed to this proposal, and in Washington, on his return journey, Curtin obtained the approval of the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

On 30th June the representatives of the British Services, led by Daniel, presented to the Australian Chiefs of Staff a revised statement of the requirements of the British forces which it was intended to base in Australia. The estimates were based on the assumption that Germany would be defeated by 1st October 1944. The fleet to be based on Australia was now to include at the outset 2 or 3 battleships, 2 or 3 large carriers, 10 cruisers and corresponding numbers of smaller vessels, and be increased to 4 battleships, a total of 28 carriers of all types, 12 cruisers, 88 LSTs and other craft.

It was assumed by the planners, Daniel said, that the British military force to be based in Australia would include five divisions, two tank brigades, some commandos and base troops, the whole force totalling, say, 225,000. It was estimated that 40,000 base troops would arrive from India in February 1945, one division from the Mediterranean in March, two divisions from India and one from England in April, and a division from England in May. The dispatch of the divisions from India was conditional on the situation in Burma permitting it. The divisions were to be ready for operations at various dates between August and October.

The Australian Chiefs of Staff advised the Government that the accommodation of these forces, which would finally total 675,000 – equal to about one-tenth of the Australian population – would make heavy demands on materials and labour. (It was as though an additional force of about 5,000,000 were, within a year, to be disembarked in the United Kingdom, or a force of 12,000,000 disembarked in the United States.) A labour force increasing to 26,000 by February would be needed to carry out the necessary building program. To relieve the load to be carried by the railways some 100,000 tons of additional coastal shipping would be needed, and 12,500 men to operate ports and railways. The whole project would depend to a large extent on whether enough coal was available. Probably 15 additional air transport squadrons would be needed. The Chiefs of Staff said that it was essential that a decision about the United Kingdom

plans should be made by mid-September so that the necessary work could begin in time. A detailed study of the Australian proposals for accommodating and supplying the proposed forces was prepared; it occupies more than 200 printed pages.

The conclusions reached at the Prime Minister’s discussions in London and Washington were set out in an agendum presented to the Australian Advisory War Council and War Cabinet on 5th July and approved by both bodies. In this agendum Curtin quoted from the record of his final discussion with Churchill which ran: “Mr Curtin said it was impossible for him, in the absence of any discussion with his colleagues ... to commit himself to any changes in the Command arrangements in the South-West Pacific Area. He referred to the history of those Command arrangements. ... The [Pacific War Council in London] had, to all intents and purposes, ceased to exist, and the Washington body was completely defunct. He therefore had had to deal with General MacArthur as an Allied Commander with Headquarters established in Australia. He feared that there was a danger of the gravest misunderstandings with the United States if Australian Forces were taken away from General MacArthur’s direct command and placed under a new Commander.”

After the conference in London the British Chiefs of Staff prepared a revised “middle-strategy” plan according to which three Australian divisions supported by a British fleet would attack Ambon. They proposed also that the command arrangements in the South-West Pacific should be altered: that area should become subordinate to the Combined Chiefs instead of the Joint Chiefs, and the British and Dominion forces should operate as “a distinct Command with British Commanders under General MacArthur’s supreme direction”. They added, however, that this arrangement should be left open to reconsideration at a later date.

At this stage the British Chiefs of Staff learnt that the American time-table was being accelerated to such an extent that the Americans might be in Formosa by the time the Australians, if the “middle strategy” was adopted, were in Ambon. The American Chiefs of Staff now advised the British to concentrate on an offensive from the west against the Netherlands Indies, with Ceylon and not Darwin as the main base; the British Chiefs recommended that an Imperial force should be placed under MacArthur’s direction to secure oil installations and air bases in northern Borneo. The difference between Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff was still unresolved after seven months of debate. On 17th July Churchill summoned Mountbatten to London, intending, after discussion with him, to give a final decision.

In June Mountbatten had been directed to concentrate on the north Burma strategy desired by the Americans. He was to develop the air link with China in order to provide more oil and other stores for the forces in China, and was to prepare to develop overland communications with China. During July the Japanese, defeated at Imphal, were in full retreat towards Tiddim and the Chindwin. It seemed that in Burma the tide had turned. After keen discussion it was agreed between the British and

American staffs on 8th September that a plan of Mountbatten’s to clear northern Burma to a line Kalewa–Shwebo–Lashio should be adopted and in mid-March 1945 a seaborne and airborne attack on Rangoon should be undertaken.

Meanwhile on 4th July Mr Curtin had sent a telegram to Mr Churchill in which he said that the increasing pace of the American advance might make it unnecessary for large-scale military operations to be undertaken by British Commonwealth forces, but that General MacArthur’s weakness at sea could be overcome only by the use of British naval forces.

It not only would contribute in great measure to the acceleration of the operations, but would be the naval spearhead in a large portion of this campaign (Curtin added). It is the only effective means for placing the Union Jack in the Pacific alongside the Australian and American flags. It would evoke great public enthusiasm in Australia and contribute greatly to the restoration of Empire prestige in the Far East ... the pace of events here demands immediate action. ... Britain’s war record in relation to her resources is so magnificent that it will bear favourable comparison with any other nation, even if circumstances and the speed of the American program preclude her making an early contribution of land and air forces.

On 12th August Curtin again pressed Churchill for the early dispatch of a British naval force to the Pacific, emphasising that the need was not for a large contribution of sea, land and air forces at some future time but for a naval force as soon as possible. “I am deeply concerned,” cabled Curtin, “at the position which would arise in our Far East if any considerable American opinion were to maintain that America fought a war on principle in the Far East and won it relatively unaided while the other Allies, including ourselves, did very little towards recovering our lost property.”

On 9th August the British leaders had decided to inform the American Chiefs of Staff that they wished a British fleet to share in the operations against the mainland of Japan or Formosa, but that if this offer was declined in favour of support of MacArthur’s operations by the British Fleet they should propose “the formation of a British Empire task force under a British commander, consisting of British, Australian and New Zealand land, sea and air forces, to operate under General MacArthur’s Supreme Command”. In this event they suggested that control of operations in the South-West Pacific Area should be on the same footing as control of operations in South-East Asia Command except that the American Chiefs of Staff should be the channel of communication for the South-West Pacific Area and the British for South-East Asia Command: that was to say that the South-West Pacific Area should come under the control of the Combined Chiefs and thus Britain would be able to influence it directly.

On 23rd August Churchill replied to Curtin, repeating a cablegram that he had just sent to Washington outlining these conclusions. This cablegram pointed out that the Japanese had increased their strength in Burma from four and a half to ten divisions, and stated that the capture of Myitkyina (which had fallen to Lieut-General Joseph W. Stilwell’s American-Chinese force on 3rd August) ruled out “as was always foreseen, any purely

Central Pacific Area

defensive policy in north Burma”. It was necessary, he said, to protect the air link to China and support the further construction of the Burma Road and the pipe line to Yunnan. Admiral Mountbatten, Churchill added, had put forward alternative plans: either to continue the north Burma operations, or to capture Rangoon by an airborne attack, open that port and support the later operations by sea, at the same time cutting the communications of the Japanese armies in north Burma. The British leaders favoured the second course, and were asking the Combined Chiefs of Staff to provide resources for the operations against Rangoon. Meanwhile, the cablegram added, a British fleet was being built up in the Bay of Bengal most of which would not be needed for the operations outlined. By mid-1945 it could take part in the operations leading to the final assault on Japan. But if the American Chiefs of Staff were unwilling to accept this

contribution the British Government would discuss as an alternative the “British Empire task force under a British Commander” mentioned above.

Curtin protested strongly against the alternative proposal for British participation, reminding Churchill, on 1st September, that on several occasions he had emphasised that Australia had a deep interest in preserving the existing command arrangements in the South-West Pacific. Government and Opposition leaders were agreed that they should not be varied. He should have been consulted before the new proposal for a British-led British and Dominion force had gone to Washington.

Churchill replied that it had not been suggested that Australian troops should be taken away from General MacArthur. “On the contrary, we have suggested sending to Australia a British naval force which would be combined with the Australian and New Zealand forces already on the spot into a British and Dominion task force under General MacArthur’s direct command.” Thus the phrase “under a British commander” was now omitted, and did not recur in later discussion of the subject15 Churchill added that it was the practice of the Combined Chiefs to draw plans for British and American forces without references to “the various Governments whose forces are included”.

Curtin declined to let the matter rest there but (on 16th September) sent Churchill a further cable saying that he felt that he had not misunderstood the task force proposal, and that in principle it did involve a change in the existing direct relationship between the Australian forces and General MacArthur. (Curtin communicated the gist of all these messages to MacArthur.)

Since it was for the sake of prestige that the United Kingdom wished to be represented by forces in the Pacific it was natural that they wished the commander of the proposed task force to be a member of a British Service. Curtin, however, had long since clearly indicated that such a proposal would not be acceptable to Australia; and it seems doubtful whether the British staffs had really thought out the complex command and administrative problems involved, or appreciated the difficulty of defining the spheres of the task force commander on the one hand and Blamey and the Australian Chiefs of Staff on the other. Another aspect was that the proposed commander and his staff would inevitably be new to the area and its problems, whereas the Australians had attained a degree of efficiency in the type of land warfare imposed by conditions in the Pacific and South-East Asia which at that stage was probably unsurpassed.

Meanwhile, on 9th September the American Chiefs had accepted the British proposal for a British task force under a British commander who would be subordinate to MacArthur, but ignored the main proposal concerning participation in the attack on Japan by the British Fleet. Thus one British proposal was unwelcome to the Americans and the other not acceptable to the Australians.

The command problem, combined with growing uncertainty whether they could spare a military contingent for the proposed task force, made the British leaders the more resolved to obtain acceptance of the offer to send their main fleet to the Central Pacific. And on 12th September the Chief of the Air Staff, Marshal of the RAF Sir Charles Portal, brought forward a new proposal that, after the German collapse, a strong force of British heavy bombers should take part in the long-range bombing of Japan. Consequently, on the eve of a conference at Quebec in August between the British and American leaders, the British were determined to press hard for the employment of the fleet in the Central Pacific and for the employment of their heavy bombers against Japan, and were ready to withdraw the offer of a British Commonwealth task force in the South-West Pacific Area. At the first plenary session at Quebec Mr Churchill offered the main British fleet for service in the Pacific and President Roosevelt promptly accepted it. Churchill then said that the placing of the main British fleet in the Central Pacific would not prevent a detachment from working with General MacArthur if desired, and added that there was “no intention to interfere in any way with General MacArthur’s Command”.

Later, however, the American Chiefs sent a memorandum to their British colleagues in the course of which they said that they considered that the initial use of the British naval task force should be on the western flank of the advance in the South-West Pacific. This led to long and acrimonious debate in the course of which it became evident that Admirals William D. Leahy and Ernest J. King – two politically aware admirals – did not want the British Fleet to have any share in the main operations in the Pacific and the British Chiefs considered it “for political reasons ... essential” that it should.16 Finally the Combined Chiefs agreed that the British Fleet should participate in the main operations against Japan in the Pacific, took note that the British Chiefs withdrew their proposal to form a British Empire task force in the South-West Pacific, and invited the Chief of the Air Staff to put forward proposals about the contribution the RAF could make to the main operations against Japan. Thus, after nine months of debate, the nature of the British contribution in the Pacific was at last agreed upon.

What was the strength and distribution of the Japanese armies now awaiting the final battles? Twenty-six Japanese divisions – one quarter of the total – were in China proper. An additional fourteen were in Manchuria, and thirteen in Japan itself or the Kurile Islands. Thus approximately half the fighting formations were in Japan or deployed against China and possible attack by Russia. Twenty-three divisions, less than a quarter of the total, and some of them now mere fragments, were scattered along the American line of advance or were isolated in areas of American responsibility. Nineteen were in Burma, Malaya and those parts of the Netherlands Indies that lay west of New Guinea. Six lay isolated

in the areas for which Australia would soon take responsibility. These figures do not include numerous independent brigades. All the divisions in Burma, Australian New Guinea and the Central Pacific were veteran formations, as were about two-thirds of those then in the Philippines and Ryukyus, whereas more than half of those in Japan, China and Manchuria had been formed since the war began.

General MacArthur’s army and air force had been greatly increased during 1944. At the beginning of that year it had included four army corps: the I, II and III Australian and I American. In March, the XI American Corps had been added, in June the XIV Corps, in July the X Corps and in September the XXIV, temporarily on loan from Admiral Nimitz. At the beginning of the year MacArthur had possessed one American army – Lieut-General Walter Krueger’s Sixth; in September a new army – the Eighth, under Lieut-General Robert L. Eichelberger – had been created. In December the Sixth Army (nine divisions) was on Leyte and the Eighth mainly in Dutch New Guinea.17 Meanwhile in June 1944, as mentioned, the Combined Chiefs of Staff had agreed to an Australian proposal that henceforth Australia would maintain a reduced army of six infantry divisions and two armoured brigades; and the III Australian Corps headquarters had ceased to exist. In October the I Australian Corps was commanded by Lieut-General Sir Leslie Morshead and the II by Lieut-General S. G. Savige.18

Of eighteen American divisions that General MacArthur commanded in the third quarter of 1944 six and one-third were employed in the defence of Torokina, Aitape and the New Britain bases. Other divisions were similarly guarding the bases at Morotai, Biak, Hollandia and Sansapor where Japanese forces were still at large, and three divisions were only on loan from Nimitz. If the policy was continued of seizing air bases and manning a defensive perimeter around them with a force generally greater than the enemy force in the area, MacArthur’s advance would soon be halted because his army would be fully engaged defending its bases against “by-passed” Japanese. The reconquest of the Philippines would require more divisions than MacArthur could provide unless he was able to use the large part of his force which was tied down in New Guinea and the Solomons. His solution was to hand over the problem of the bypassed garrisons to Australia.

A natural desire that Australians should take a leading part in regaining their own lost territory was reinforced by the decision of February 1943 that conscripted soldiers should not be employed north of the equator. The decisive battles of 1945 would be fought far north of that line. The

three AIF divisions, consisting solely of volunteers, could be sent there or anywhere else in the world, but a proportion of the men in the militia divisions had not volunteered, and their units could not be sent to the Philippines, for example, or northern Borneo, until the conscripts had been subtracted, a process that would entail considerable regrouping and retraining. For example, in October 1944, 13 of the 33 militia infantry battalions had not the 75 per cent of volunteers needed to entitle them to add the letters “AIF” in brackets to the name of their battalion, and in the remaining 20 battalions there were small percentages of non-volunteers. Consequently an Australian political problem would be avoided if the partly-militia force – about three divisions – was employed south of the equator.

Throughout 1942 and 1943 (as Blamey had pointed out in a broadcast statement in September) “the great bulk of the land fighting in the South-West Pacific area fell upon the Australian Army”. Only after more than two years had the American Army taken over the major share. In the past year, however, a greatly increased American Army, lavishly equipped and strongly supported by sea and air forces, had developed tactics by which it had overcome outlying Japanese garrisons and had gained in confidence and efficiency. It was becoming evident too that, for the sake of enhancing American prestige in the Far East after the war, some American leaders wished the Stars and Stripes alone to float above the major battlefields of 1945.

The association between General MacArthur and the Australian Government (in the persons of Mr Curtin, General Blamey, and the Secretary of the Defence Department, Sir Frederick Shedden) had been harmonious, but nevertheless those who had been close to the American headquarters knew that at least some of its senior members would be happy to snap the link. The cooperation of allies produces many difficulties and irritations, particularly when the larger one is established in the territory of the smaller. And a headquarters staff of which an astute American observer was to write that they considered Washington and perhaps even the President himself to be under the domination of “Communists and British Imperialists”,19 was not likely to find the atmosphere of Australia, a British country with a Labour Government, entirely congenial. In addition the combination of two national armies creates many problems of organisation and equipment, tactics and temperament. It would be satisfactory to MacArthur’s headquarters if a separate sphere of action could be found for the Australians; particularly would it be gratifying if one such sphere should be the relief in Australian New Guinea of the American divisions urgently needed in the Philippines.

As early as 22nd November 1943 Mr Curtin had written to General MacArthur pointing out that Australia had a special interest in the employment of her own forces in ejecting the enemy from her New Guinea territories. At that time American forces were engaged or would soon be

engaged in four areas on Australian territory: Bougainville, New Britain, Saidor, and Aitape–Wewak. General Blamey had long anticipated an American request that Australian troops should take over all areas in Australian New Guinea. On 3rd March 1944, in a letter to Morshead, then commanding in New Guinea, Blamey had said that he envisaged being required soon to garrison the Mandated Islands, and expected to have about eight militia brigades available for this purpose, of which three would probably be in New Guinea, two or three in New Britain and Bougainville, with two at Atherton working reliefs.

On 22nd May 1944 General Northcott had cabled to Blamey, then in London, that Major-General Stephen J. Chamberlin of General Headquarters had said that possibly Australian troops would be required to garrison New Britain, relieving the American division there in November. As he had indicated to Morshead, Blamey planned to garrison the Solomons, New Britain and the mainland of New Guinea, then held by six and a half American divisions, from his three “militia” divisions. Thus he would hold ready for a possible task in the Philippines the veteran 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions.

The plan took more definite shape on 12th July when MacArthur sent Blamey the following memorandum:

1. The advance to the Philippines necessitates a redistribution of forces and combat missions in the Southwest Pacific Area in order to make available forces with which to continue the offensive.

2. It is desired that Australian Forces assume the responsibility for the continued neutralisation of the Japanese in Australian and British territory and Mandates in the Southwest Pacific Area, exclusive of the Admiralties, by the following dates:

Northern Solomons–Green Island–Emirau Island – 1 Oct 1944

Australian New Guinea – 1 Nov 1944

New Britain – 1 Nov 1944

3. The forces now assigned combat missions in the above areas should be relieved of all combat responsibility not later than the dates specified in order that intensive preparations for future operations may be initiated.

4. In the advance to the Philippines it is desired to use Australian Ground Forces and it is contemplated employing initially two AIF Divisions as follows:

One Division – November 1944

One Division – January 1945

5. It is requested that this headquarters be informed of the Australian Forces available with the dates of their availability to accomplish the above plan and your general comments and suggestions.

In the subsequent discussion MacArthur would not accept a proposal by Blamey that he should hold the perimeters with only seven brigades (little more than one-third of the American forces thus employed) and insisted that he use four divisions – twelve brigades.20 As a result, at a series of conferences between Blamey’s staff and MacArthur’s, a directive

was issued by MacArthur on 2nd August that the minimum forces to be employed in the New Guinea areas should be:

| Bougainville | 4 brigades |

| Emirau, Green, Treasury and New Georgia Islands | 1 brigade |

| New Britain | 3 brigades |

| New Guinea mainland | 4 brigades |

This left a corps of only two divisions for operations farther north with no reserve division. Under a revised arrangement Australian forces were to take over on the outer islands on 1st October, in New Guinea on 15th October, on New Britain on 15th November, and on Bougainville by stages from 15th November to 1st January. MacArthur’s insistence that the equivalent of four divisions be employed in the New Guinea areas made it necessary to use one of the AIF divisions there. Only the 6th would be at full strength and ready by 15th October and therefore Blamey chose it to relieve the American Corps at Aitape.21

At this time the estimated strength of the Japanese forces in the three New Guinea areas was:

| Bougainville | 13,400 |

| New Britain | 38,000 |

| Wewak area | 24,000 |

Before the end of the year, however, as a result of information and discussion which will be recorded later, the Bougainville estimate was increased to about 18,000. In fact all these estimates were far too low, as the Intelligence staffs gradually discovered, although the whole truth was not known until after the war had ended. The number in the three areas plus New Ireland totalled not 80,000 but about 170,000 including some 25,000 civilian workers.22 Eventually 138,200 surrendered, including 12,400 on New Ireland.

The decision that Blamey should employ more troops in New Guinea than Blamey considered necessary was a puzzling one in view of American staff doctrine that when a commander had been allotted a task he himself should decide how to carry it out, and the question arises whether considerations of amour-propre were involved: whether GHQ did not wish it to be recorded that six American divisions had been relieved by six Australian brigades (taking into account that one of the seven Australian brigades already had a role in New Guinea and was not part of the relieving force). An even more interesting aspect of the disagreement is that Blamey’s proposal seems to indicate that, in July and earlier, he was not contemplating offensive operations on Bougainville and from Aitape, because he could not reasonably have undertaken them with only two brigades in each area. Thus it was the decision of MacArthur, who considered that the Japanese in those areas should not be attacked, to place three instead of two brigades at Aitape and five instead of two in the northern Solomons that made it feasible for the Australians to undertake offensives there, should they so decide.

In preparation for the new phase in which, in General Blamey’s words, the army would undertake its “maximum effort during the war”, Blamey had held a conference on 11th August at his advanced headquarters at Brisbane, attended by the commanders and senior staff officers of the First Army, New Guinea Force and I Corps and by his own senior staff officers. There he issued instructions that the future roles of the Australian Army would be: first, to occupy the Australian New Guinea areas; and, second, to prepare an AIF Corps for future offensive operations in the South-West Pacific. The headquarters of Lieut-General V. A. H. Sturdee’s First Army would move from Atherton to Lae and would command all Australian forces in Australian New Guinea. Blamey directed that from the existing New Guinea Force headquarters, under Lieut-General Savige,

a headquarters of II Corps would be formed (until May 1944 Savige’s command had been so named). It would control one division and two brigades. (These were to be the 3rd Division and the 11th and 23rd Brigades.) New Britain would be taken over by one division (the 5th was allotted). The Madang area would continue to be garrisoned by one brigade (the 8th).

The task of II Corps was to defend the air and naval installations on Emirau, Green and Treasury Islands and Munda and, on Bougainville, to “destroy enemy resistance as opportunity offers”.23 The task on New Britain would be to “maintain contact with the Japanese by patrol activity and, without commitment of major forces, endeavour to advance to a line Open Bay–Wide Bay”. At Aitape the 6th Division (which might be needed later in the Philippines) was to “defend the airstrip and base area and by patrol activity maintain contact with the enemy in the Wewak area. The commitment of major forces was to be avoided.”

In each area there had long been little contact between the American garrisons, manning the defensive perimeters round the bases and airfields, and the Japanese. From the outset the Australian forces were to adopt a more active policy, although in each place, at this stage, a restricted one.

In July Blamey had decided that, in consequence of the movement of General Headquarters to Hollandia and the proposed movement of Advanced GHQ to Leyte, he would form a Forward Echelon of his own headquarters which would move with Advanced GHQ to safeguard Australian interests.24 Lieut-General F. H. Berryman, now titled “Chief of Staff, Advanced LHQ”, commanded this echelon. On 14th November 1944 Blamey approved a re-arrangement of the functions of LHQ in Melbourne and Advanced LHQ, as a result of which LHQ took over control of operations in Australia, plus those at Merauke; and Advanced LHQ was defined as “HQ for C-in-C Allied Land Forces and C-in-C AMF for dealings with GHQ SWPA [and] for operations of the AMF outside Australia except for Torres Strait and Merauke areas”.25 The role of the Forward Echelon would be to “move forward with GHQ to assist in the preparation of plans for future employment of the Australian Corps and to initiate movement of troops, equipment and stores to and within the complete area of operations of the Australian Forces abroad”. Thus on 7th September, about a fortnight after MacArthur’s advanced headquarters was established at Hollandia, the Forward Echelon of Blamey’s headquarters had been opened there; and on 15th December Advanced Land Headquarters itself opened at Hollandia.

In the new phase, Blamey would command a total of six subordinate formations: First Army, Second Army, I Corps, Northern Territory Force, Western Command and 11th Division. Lieut-General Sturdee’s First Army opened its headquarters at Lae on 2nd October. Under it would be Savige’s II Corps with headquarters at Torokina in Bougainville; Major-General A. H. Ramsay’s 5th Division on New Britain; Major-General J. E. S. Stevens’ 6th Division at Aitape; and the 8th Brigade in the area west of Madang.

The deployment of twelve brigades in New Guinea and the Solomons left in Australia, apart from I Corps training on the Atherton Tableland, only two brigades of infantry. The Second Army – the reserve army – had diminished until its infantry component was one division (the 1st) which, after 8th January 1945 when the 2nd Brigade was disbanded at Wall-grove, would possess only one brigade. In Queensland (under Blamey’s direct control) was Major-General A. J. Boase’s 11th Division, a reserve divisional headquarters with no infantry brigades under command, as all three brigades normally allotted to it were serving under other commanders in New Guinea. There was now only one brigade (the 12th) in the Northern Territory Force. The garrison of Western Australia (Major-General H. C. H. Robertson’s Western Command) had been reduced almost to vanishing point.

On 7th and 21st September 1944 Blamey spoke to the Advisory War Council about the forthcoming operations. Concerning Bougainville he said that Torokina had been an inactive area but the Australian forces would not perhaps be quite so passive. Large-scale operations were not contemplated at present; the enemy strength would be probed and the extent of further operations then determined.

In the last quarter of 1944 the Australian formations relieved the Americans in the various areas, as planned. On 18th October Blamey issued to Sturdee an operation instruction which defined the role of the First Army in the Bougainville, New Britain and Aitape areas as “by offensive action to destroy enemy resistance as opportunity offers without committing major forces”.

In order to be able to interpret this to lower formations (Sturdee wrote to Blamey on 31st October), I should be glad if you would give me some advice on the reason for the restriction “without committing major forces”.

There seem to be two aspects, one to avoid being so deeply committed that it might be necessary to call for outside assistance if the Japs were unexpectedly stronger than anticipated. The other is that the Jap Garrisons are at present virtually in POW Camps but feed themselves, so why incur a large number of Australian casualties in the process of eliminating them.

If the former is the reason then interpretation is easy, but if it is the latter, then I should like some guidance as to the extent of the casualties that would be justified in destroying these Jap Garrisons.

In the case of Aitape, I realise that 6 Div must be kept on ice for larger operations in 1945. In New Britain I do not have the forces available to do more than keep the Japs confined to the Gazelle Peninsula and by active patrolling eliminate as many as possible.

The real difficulty is with Bougainville, where already there are signs of commanders spoiling, quite laudably, for an all-in fight with the resources at their disposal.

I tried [Brigadier] Barham26 for some light on the above when I was in Hollandia last week, but he was unable to answer my point.

I realise that there may be some question of prestige that makes the clearing up of Bougainville an urgent necessity, or alternatively of the elimination of the Japs in that area to reduce inter-breeding to a minimum and so avoid the potential trouble of having a half native-Jap population to deal with in the future.

In the course of his reply, written on 7th November, Blamey wrote:

My conception is that action must be of a gradual nature. In the first place our information is imperfect. Before any very definite plans can be made for the destruction of the enemy resistance, it is essential that this information should be greatly enlarged.

This means the early development of patrol action. This again, to my mind, separates itself into two actually overlapping phases. The first is the pushing forward of the native troops into the wild to ascertain the location and strength of the enemy in various places. If this is reasonably successful it should give sufficient information to enable plans to be made to push forward light forces to localities which can be dealt with piecemeal. These light forces would form the nuclei from which patrols would contact and destroy the enemy by normal methods of bush warfare. By such means as these it should be possible, first, to locate the enemy and continually harass him, and, ultimately, prepare plans to destroy him.

Alongside of this, when the enemy is a little more definitely located, every means should be employed, by way of landing parties from small craft, from the air or by other means, to harass and destroy such of his forces as may be located.

The reason for the restriction “without committing major forces” is that it is not desired to formulate plans for a definite advance against main areas of enemy resistance, which will lead to very heavy casualties on our side, until the situation is much clearer. ...

With regard to Bougainville, our information is far from exact. The ... latest information produced by our Intelligence ... shows 25,000 troops, whereas two months ago the estimate was 12,000 to 13,000.

I quite appreciate the desire of commanders for an all-in fight, but the present lack of information and the fact that the enemy strength is unknown on the island make it most desirable that there should be a complete probe and a better knowledge gained before any large commitment is undertaken.

I fully appreciate the undesirability of retaining troops in a perimeter, particularly our Australian troops, over a long period, since this is certain to destroy the aggressive spirit which is essential against the Japanese. I hope, therefore, that there will be a considerable increase in our activity along the lines I have indicated above.

As a result of Blamey’s letter Sturdee on 13th November issued a new instruction in which he said that it was considered unwise to undertake major offensive operations to destroy the enemy until more information was available. It added:

In order (a) to obtain the required information, (b) to maintain the offensive spirit in our troops, and (c) to harass the enemy and retain moral superiority over him, offensive operations will consist of patrols and minor raids by land, sea and air, so far as our resources will permit.

Operations will be divided into three phases: A. Patrols and raids ...; B. Based on the information obtained in Phase A, the preparation of plans for major offensive operations; C. Offensive operations designed to destroy the enemy. Phase C will not be undertaken without prior approval from this headquarters.

It remained to allot a definite role to I Australian Corps. This would depend on American plans.

Before Krueger’s army landed on Leyte the American forces in the Pacific had received orders for the next stages of the advance towards Japan. The planning of a proposed assault on Formosa and the China coast had been in progress during most of 1944. On 27th and 28th July 1944 President Roosevelt had met General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz at Honolulu and discussed future operations. Nimitz wished to by-pass Luzon and MacArthur wished to reoccupy it. Roosevelt decided that Luzon should be reoccupied.27

Admiral Nimitz proposed to invade Formosa as soon as General MacArthur’s forces were established in the southern and central Philippines. This was to be followed by landings in the Ryukyu and Bonin Islands. A joint staff study of the Formosa operation had been published at Nimitz’s headquarters on 23rd August. However, after the Joint Chiefs instructed General MacArthur to invade Leyte two months earlier than had been intended, and Nimitz to by-pass Yap, Nimitz asked his army commanders to express their opinions on a proposal to advance north by way of the Bonins and Ryukyus without landing on Formosa first. It seems probable that Nimitz and his staff preferred to operate as an independent force as they had in the past, and advance on an axis parallel to MacArthur’s towards the final objective, delaying the inevitable time when both the predominantly naval force of Nimitz and the predominantly army force of MacArthur must be amalgamated. Lieut-General Robert C. Richardson, commander of the army forces in the Pacific Ocean Area, replied to Nimitz that MacArthur’s seizure of Luzon, after Leyte, would enable the Japanese forces operating from Formosa to be neutralised, and the seizure of bases in the Ryukyus to be carried out. The capture of bases in the Bonins would provide alternative bases for bombing attacks on Japan.

Lieut-General Millard F. Harmon, commanding the army air forces in the Pacific Ocean Area, reminded Nimitz that he had earlier suggested the seizure of islands in the Ryukyus as an effective and more economical alternative to an invasion of Formosa. Lieut-General Simon B. Buckner, of the Marines, commander of the Tenth Army to which the capture of Formosa had been allotted, offered a more definite objection. “He informed Admiral Nimitz that the shortages of supporting and service troops in the Pacific Ocean Areas made [Formosa] unfeasible.”28

On 2nd October Admiral King proposed to the Joint Chiefs that, because of the lack of sufficient troops to execute the assault on Formosa and because the army could not make such troops available until the end of the war in Europe, operations against Luzon, Iwo Jima (in the Bonins)

and the Ryukyus should precede any attack on Formosa. Next day the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur to invade Luzon on 20th December and Nimitz to seize one or more positions in the Ryukyus by 1st March 1945. On the 5th Nimitz informed his subordinates that his forces would seize Iwo Jima on 20th January and positions in the Ryukyus on 1st March. Thus from bases in Luzon air and naval forces could neutralise the Japanese in Formosa; from Iwo Jima fighter support could be given to B-29’s attacking the Japanese mainland; the capture of Okinawa in the Ryukyus would bring American forces within 300 miles of Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese islands.

The role of I Australian Corps in these main operations was changed several times in the five months between August 1944 and January 1945. As mentioned, on 12th July MacArthur had said that in the advance to the Philippines he contemplated using one AIF division in November and a second in January. In August, however, GHQ had indicated that the corps would be employed in Luzon about 20th February 1945, when it would land at Aparri on the north coast as a preliminary to the landing of American forces at Lingayen Gulf some 18 days later.

On 5th September 1944 Berryman informed Blamey that MacArthur intended to bring the 6th Division to the Lingayen area on Luzon when it had finished its job at Aitape. He hoped that this would be in March. It would be employed in the final drive on Manila. After the capture of Luzon MacArthur proposed to drive south and use the AIF in British Borneo. If Washington decided to by-pass Luzon in favour of an attack on Formosa by the Central Pacific force, MacArthur proposed to use the AIF in an advance on the Visayas–Luzon axis. On 26th September, in elaboration of this plan, GHQ stated that the task of I Australian Corps would be to establish at Aparri a base whence aircraft could support the operations against Manila; but only if Nimitz’s carrier-based aircraft could not ensure the protection of the transports round the north coast of Luzon. If MacArthur had adequate naval support the Aparri operation would be cancelled. Indeed it was becoming evident to those Australians who were close to GHQ that GHQ would prefer not to have Australians playing any notable part in the reconquest of the Philippines. On 7th October Berryman recorded in his diary that MacArthur’s Chief of Staff, Lieut-General Richard K. Sutherland, had informed Blamey that

it was not politically expedient for the AIF to be amongst the first troops into the Philippines.

Late in October Blamey’s Forward Echelon was informed that the employment of the Australian Corps at Aparri had been cancelled and the future role of the corps would probably be to operate on Mindanao as part of the Eighth American Army, and then to advance into the Netherlands Indies. The 6th, 7th and 9th Australian Divisions would attack Mindanao on 1st March, Jolo Island on 1st April, Kudat on 1st May, and Labuan Island in British Borneo on 1st June. Another phase would be undertaken by XI American Corps: Tarakan on 20th April,

Dutch New Guinea. Borneo and the Philippines