Chapter 8: Across the Hari: Porton Plantation

THE comparative lull which followed the defeat of the Japanese counter-offensive early in April lasted for three weeks. General Savige and General Bridgeford agreed that no attacks should immediately be launched, and that the Japanese should be allowed to exhaust themselves in costly onslaughts. The Japanese, however, were in no position to convenience their enemies by making further heavy attacks. On the other hand the timing of any Australian attacks depended on ability to deliver supplies from the Torokina base. To maintain an effective force in the forward area it was necessary to make roads that would carry either jeeps or 3-ton trucks, and, in some cases, both. Each such road involved laying extensive corduroy and building many bridges across rivers and creeks.

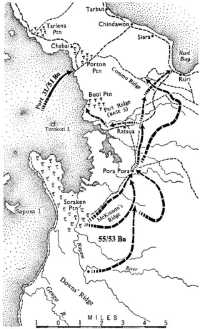

Thus on 19th April, soon after the 15th Brigade had relieved the 7th, Savige, after a visit to the 3rd Division’s area, confirmed the plan that Bridgeford should continue to employ only one brigade forward, and that a second brigade (the 29th) should guard and maintain the lines of communication, with one battalion in readiness to counter an enemy movement round the inland flank. He said that one battalion of the leading brigade should advance on the northern axis and one on the southern, while the third was held in close support. Savige had now obtained a third regiment of field artillery – the 2/11th – and he placed it under Bridge-ford’s command. Because of the difficulty of supply Savige directed that no man who was not “absolutely essential” was to be employed forward of Toko. He gave Bridgeford as his objective the line of the Hari River; the line of the intervening Hongorai River was to be an “intermediate objective”.

The total Japanese strength in southern Bougainville was now estimated by the Corps staff at from 10,500 to 11,000, of whom 2,300 were believed to be immediately opposing the 3rd Division, the main concentrations being in the garden areas west of the Hari River. (In fact the Japanese strength in southern Bougainville still exceeded 18,000.)

The incoming 15th Brigade1 had at the outset been by far the most experienced to arrive on Bougainville. Brigadier Hammer, who had corn-

manded it during arduous operations on the New Guinea mainland in 1943 and 1944, had moulded it into a capable, self-confident force. It had just completed ten weeks of intensive training at Torokina. Hammer himself was a tireless, fiery and colourful leader who would be likely to drive his men hard in the coming operation, encouraging them with vigorously-phrased exhortations. On the day on which the brigade took over the southern sector he distributed an order of the day predicting a long tour of duty with perhaps heavy casualties but expressing confidence in the outcome.

Hammer was resolved to use the artillery, which now included the four 155-mm guns of “U” Heavy Battery, to the utmost, sending out artillery observers with the smallest patrols so that, when they met the enemy, they would be able promptly to bring down the fire of perhaps a regiment of guns. He hoped to herd the enemy into confined areas and there bombard him with guns and mortars. Hammer was enthusiastic about the use of noise to deceive: for example by sending a noisy fighting patrol to one flank and a silent patrol to the other to locate enemy positions and prepare the way for the main attacking force – usually tanks, an infantry battalion and supporting troops. Bulldozers would be used to cut tributary tracks along which tanks could make flanking attacks. Hammer had the advantage of increased air support because there were now four instead of two New Zealand squadrons on the island; the tonnage of bombs dropped increased from 493 in March, to 663 in April, and to 1,041 in May.

The country between the Puriata and the Hari generally resembled that to the west. The coastal plain was some ten miles in width and clad with dense bush above which towered large trees. Big areas of swamp occurred near the coast. East of the Puriata the Buin Road (or “Government Road No. 1”) ran 5,000 to 6,000 yards from the coast. The Commando Road (or “Government Road No. 2”) was parallel to it, some 5,000 yards farther north. The ground was so sodden that each road had to be corduroyed with logs before it could carry heavy traffic.

The task of advancing along the Buin Road was given to the 24th Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Anderson) with the 58th/59th (Lieut-Colonel Mayberry) protecting its rear and flanks, while the 57th/60th (Lieut-Colonel Webster2) advanced down the Commando Road. Hammer intended to develop the lateral track between the two main ones so that he could send tanks across the front into the Rumiki area. Hammer later recorded that when his brigade took over “contact with the Japanese had been completely lost and ... the enemy situation was most obscure”.

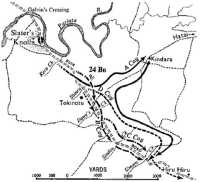

The 15th Brigade opened its attack on 17th April when the 24th advanced behind a creeping barrage, with two companies moving forward against enemy positions round Dawe’s Creek, and a third making an outflanking move to cut the lateral track to the north. The left forward company reached its objective without encountering any Japanese, but

24th Battalion, 17th–25th April

Captain Graham’s3 on the right, with Lieutenant Scott’s4 troop of tanks, became engaged in a vicious fight which lasted until the next afternoon when tanks and leading infantry were 400 yards beyond Dawe’s Creek. The tank crews spent the night in two-foot pits with the tanks above them like roofs. Thirty-seven Japanese were killed in this action, and the 24th lost 7 killed and 19 wounded. The 24th pushed on to Sindou Creek where it withstood several sharp counter-attacks during the next week, while patrols pushed forward deeply through the bush on either side of the road. One of these, a three-day patrol under Lieutenant N. J. Spendlove, reached the Hongorai about 1,000 yards south of the Buin Road crossing and reported that the river was 30 yards wide with banks eight feet high. On the return journey they observed, unseen, an air bombardment of an enemy position which scattered a party of Japanese and caused “much squealing and cooeeing”.

On 23rd April Corporal Nott,5 an outstanding leader who had taken out many patrols but had never lost a man, led a party 3,000 yards behind the Japanese forward positions to Hiru Hiru, examined the Buin Road there, and later ambushed 12 Japanese of whom five were killed at about 10 yards range.

On 26th April the advance along the Buin Road was resumed. Thirty-six Corsairs of Nos. 14, 22 and 26 Squadrons of the Royal New Zealand Air Force bombed and machine-gunned the enemy’s area to within 300 yards of the Australian positions, and so heavily that they cleared the ground of undergrowth for some distance each side of the road. A creeping barrage fired by artillery and mortars preceded the advancing infantry. There was little opposition. By 28th April the 24th was about one-third of the distance from the Puriata to the Hongorai.

It was not until 3rd May that the 57th/60th relieved the 9th in the Rumiki area. The 9th had then been in action for three months and a half and, after the 15th Brigade had begun to take over, was still strenuously patrolling in country where clashes with enemy patrols were fairly frequent. Meanwhile the lateral track to Rumiki had been cleared

15th Brigade, May–June

of the surviving Japanese parties and corduroyed, a task largely done by the infantry of the 58th/59th Battalion.

On their first days in the new area the 57th/60th on the Commando Road had several clashes and lost men – a result, it was decided, of the inexperience of the patrols as a whole. (In the operations in New Guinea in 1943 and 1944 this battalion had had less battle experience than the others in the brigade.) For instance, on 4th May a patrol commanded by Lieutenant Linehan6 walked into an ambush. Linehan was mortally wounded and as he lay dying ordered his men to press on. In the ensuing fight two others – Lance-Corporal Woolbank7 and Private Watson8 – were killed.

Meanwhile on 30th April an artillery forward observation officer, Lieutenant Tarr9 of the 2nd Field Regiment, who was with a patrol of the 24th Battalion, was missing when the remainder of the patrol returned. His body was found three days later. On 30th April and 2nd May, the 24th, with a troop of tanks reinforcing the leading company, advanced a

total of more than a mile without opposition; they were now nearing the Hongorai. However, on the 4th Lieutenant Lawn’s10 platoon was advancing with two tanks and a bulldozer when the crew of the leading tank came to a log across the road and saw movement in the bush. A burst of machine-gun fire from the tank cut the leaves away and revealed the barrel of a field gun. The first round fired from the tank’s 2-pounder disabled the enemy gun and the enemy seemed to flee. Farther ahead, however, a mine exploded at the rear of the second tank. It was discovered that it had been exploded with a wire by a Japanese concealed in the bush.

Henceforward mines and concealed guns were encountered more and more frequently. They were detected chiefly by the practised eyes of the engineer teams of Major Needham’s11 15th Field Company who became increasingly skilful. Mechanical detectors were defeated by several sorts of mine employed – wooden boxes filled with TNT, for example; but their presence was betrayed by protruding fuses, wires, disturbed earth, and confirmed by prodding with a bayonet.

There were instances where large mines, consisting of many 150-mm and 75-mm shells, were laid underneath corduroy and were so well camouflaged that detection would have been impossible without a significant stick which the enemy had placed by the side of the road. This stick was usually 2 feet to 3 feet high and about 1 inch thick. ... One mine ... consisted of a timber hole 8 feet by 5 feet by 3 feet filled with 150-mm, 75-mm shells and 81-mm mortars. This mine was blown in situ and created a crater 24 feet in diameter and 10 feet deep.12

An impression at this time that the Japanese in this sector were becoming dispirited led to a renewal of “psychological warfare”, which, it will be recalled, had already been waged on the central sector, though without visible effect. On several occasions in the first week of May a broadcasting unit of FELO spoke to groups of Japanese troops known to be only a few hundred yards away from forward posts of the 24th Battalion. For example, on the morning of the 5th the following address was broadcast in Japanese:–

Soldiers of Japan stop your movement and listen. We are now cooking a good hot meal for our troops, come in and have your first good meal for months. We have for you amongst other things fresh meat, bread and fruit, cigarettes are plentiful and clean clothes and boots are yours for the asking. We do not desire to cause unnecessary killing so we give you this opportunity to come in by walking down the road with your weapons on your backs and your hands in the air with the palms towards your front. You will be well cared for and sent to Australia where thousands of your officers and fellow soldiers are now. Do not die a useless death, come in now and build up to live and serve Japan after the war. Come in now.

Soon after this broadcast Australian troops fired on the Japanese; then a further short broadcast was made telling them that the invitation was still open and fire had been commenced because the first broadcast was not heeded. At 4 p.m. the same day a similar address was broadcast to

several Japanese in the same locality. About one minute after the broadcast began the Japanese attacked and the talk was discontinued until after the action ceased. Then the following address was given:

Japanese soldiers do you know the war in Europe is almost over? Yesterday 60 German and Italian divisions surrendered unconditionally. Berlin has fallen. Meanwhile the war fast approaches your homeland. If you continue with your futile resistance here when you are deserted by your High Command, you must surely perish. We offer you a chance to live and work for Japan in the future. Walk down the track with your hands in the air and your weapons across your backs and we will look after you well. Your officers have told you that you will be tortured if you come in. That is not true. It is told you only to ensure that you fight on uselessly. We have waiting for you a good hot meal with fresh meat and plenty of cigarettes or anything else you desire. Be wise come in now, you will be treated well and honourably as are the thousands of your officers and men in our hands. Do not hesitate.

No visible result was achieved by any of these appeals or threats.

References have been made earlier in these volumes to instances where leaflets aimed at depressing the spirits of Australian troops in the Middle East not only failed to do that but had the opposite effect of enhancing their self-esteem and improving their spirits. May not such broadcast addresses as the above have had a similar effect on the Japanese? The Japanese soldier well knew that the Japanese army on Bougainville was isolated and hungry. Each man in the front line knew that his chance of survival was poor. Broadcast addresses such as those quoted above were perhaps likely somewhat to dispel loneliness, and to raise the spirits of the men of those isolated outposts – it must be an important position they were holding and they must be holding it well if the enemy chose to adopt such elaborate and roundabout methods of taking it.

The Australian Army’s experience both at the receiving and giving end of “psychological warfare” of this sort suggests that the positive results achieved were not worth the labour that was spent on it. In the years before the outbreak of war the rulers of Germany and Russia had acted on the assumption that intensive preaching could alter the outlook of a community at fairly short notice. Many politicians, administrators and economic planners of the democratic nations developed as great a faith in “propaganda” as Dr Goebbels possessed: if the citizens’ outlook was not what was desired, one simply drugged it with “propaganda”, and if the required result was not rapidly achieved that was because the drug was not properly mixed and administered.13 However, Australian experience of battlefield broadcasts and leaflets suggests the possibility that the roots of national character are far too deep for fundamental changes to be brought about in a day, a year, or even several years of exhortation, no matter how cajoling or threatening. It was as futile to attempt to seduce Japanese soldiers from what they regarded as a divinely-appointed duty with the

offer of a hot meal and a cigarette, or to frighten them with bad news from another front, or even from Japan itself, as it was to try to stop Australians from fighting by showering them with drawings purporting to show Americans embracing their wives. The mental habits of a community and therefore of its soldiers are formed during centuries and are not likely to be basically changed during the relatively brief period of a war.14

As the 24th Battalion neared the Hongorai it became evident that the Japanese intended to make the Australians pay a price for each advance, and that they were willing to trade a field gun for a tank at every opportunity. On the 4th and many later occasions leading tanks were fired on at a range of a few yards by guns cleverly concealed beside the track, but in positions from which the Japanese could not hope to extricate them. In other respects also the Japanese tactics were improving and their striking power was strengthened. Each forward Australian battalion was now under frequent artillery fire, evidently directed by Japanese observers who remained close to the Australian advance, and it was this which was now causing most of the casualties. The shells usually burst in the trees and their fragments were scattered over a wide area with lethal effects. To counter the tanks the Japanese were now establishing their positions not astride the track but about 100 yards from it in places where the tanks could not reach them until a side track had been made.

Early in May General Savige received news of a most valuable reinforce-ment – the headquarters and one additional squadron of the 2/4th Armoured Regiment. This regiment had been formed in November 1942 to take the place in the 1st Armoured Division of the 2/6th when it went into the Buna fighting in New Guinea. It had recently been training at Southport (Queensland), where it was re-armed with Matilda tanks and expanded into a self-contained regimental group with its own technical sections. It was sent to Madang in August 1944, whence, in November, one squadron moved to Aitape to come under the command of the 6th Division, and in December a second squadron (Major Arnott’s) was sent to Bougainville. The regiment had not been in battle as a regiment but it had had years of hard training and included a sprinkling of men who had been in action with other cavalry and armoured units. One of these was the commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel Mills,15 who had been an outstanding cavalry squadron commander in North Africa and Syria.

This reinforcement would enable the relief of the squadron then in action – its tanks were worn and were kept running only by a great amount of maintenance work – and perhaps the employment of tanks in the northern sector.16 The early relief of Arnott’s crews was desirable. The

slow advances along the track entailed arduous periods of up to six hours in closed tanks. Meanwhile, as a result of their experience of using tanks in support of infantry on the narrow tracks travelling through thick forest, Arnott and his officers had worked out a settled tactical doctrine: the leading tank should move fifteen yards ahead of the second, with freedom to fire forward and to each flank from “3 o’clock” to “9 o’clock”; the leading infantry section should be at the rear of the second tank, the second tank supporting the first and being itself protected by the infantry. At night the crews were to run their tanks over shallow pits and sleep below them.

The 24th Battalion made another move forward on 5th May. Lieutenant Yorath’s17 tank troop moved with the leading infantry, firing right and left. At 500 yards the machine-gun in the leading tank (Sergeant Whatley18) suffered a stoppage. As the crew were removing it to remedy the defect a concealed field gun opened fire wounding Corporal Clark.19 A second tank, armed with a howitzer, moved forward, knocked out the field gun and drove off the supporting infantry, who were about 100 strong. Meanwhile, under fire Whatley had lifted Clark out of the tank, carried him to safety, and raced back to his tank. That night the battalion area was sharply bombarded, more than 160 shells falling in it, and in the morning, as Captain Dickie’s20 company was moving forward to relieve Captain J. C. Thomas’, about 100 Japanese attacked. A fierce fire fight, in which the tanks also took part, lasted for two hours and a half in dense undergrowth. Some of the Japanese fell only five yards from the forward posts but overran none of them. In one forward pit Private Barnes21 held his fire until the Japanese were within about 15 yards, then mowed them down, and each time they repeated the attack he did the same. When he had used up his ammunition he carried his gun back, collected more, and returned to his post. Thirteen dead were counted round his pit. At length the Japanese withdrew leaving 58 dead – their heaviest loss in a single action since Slater’s – and abandoning two machine-guns. One Australian was killed and 9 wounded. This was the last effort to defend the Hongorai River line. On 7th May the leading company advanced to the river behind a barrage, but met no opposition. The preliminary patrolling and the advance to the Hongorai (7,000 yards in 3 weeks) had cost the 24th heavily-25 killed and 95 wounded; 169 Japanese dead had been counted.

More evidence of the enemy’s faulty communications was provided the next night when two Japanese carrying a lantern crossed the Hongorai and walked almost into a company perimeter. When a sentry threw a

grenade they fled, leaving a basket of documents. That day two patrols encountered strong groups of Japanese. In one of them four men were hit and one of these, Private McLennan,22 was left behind. He crawled away and was not found until four days later, when he was brought in by a patrol of the 58th/59th Battalion.

As the leading battalion and the tanks fought their way forward, the supporting infantrymen and the engineers toiled behind laying corduroy on the road. By the end of the first week of May the 9,300 yards of the Buin Road from Slater’s to the Hongorai and 5,000 yards of the lateral Hatai Track had been so treated.

Meanwhile the 57th/60th had also advanced to the Hongorai along the Commando Road from Rumiki. On 6th May a company crossed the river, and that day and the next their ambushes trapped parties of Japanese in the neighbourhood.

On the inland flank the 2/8th Commando Squadron had been patrolling deeply. On 8th April, just before the 15th Brigade replaced the 7th, it had again been brought directly under Bridgeford’s command. Major Winning went to Toko to discuss with the staff the future operations of his unit. It was decided that the squadron would reconnoitre and harass the enemy between the Hongorai and the Mobiai Rivers in the general area north of the Buin Road, with the special tasks of locating possible tank obstacles, the enemy’s defences and concentrations of strength, and tracks suitable for tank and motor traffic. If considered feasible the headquarters of the 6th Japanese Division then at Oso was to be raided and ambushes set on the tracks east of the Hongorai. Winning considered that his unit had now been allotted “a role which could be carried out with more purpose and to more effect than at any previous stage in the campaign”.23

The task, mentioned earlier, of bringing in the missionaries and nuns from Flying Officer Stuart’s area somewhat delayed the opening of the new phase, but on 18th April a patrol with the code name “Tiger”, under Captain K. H. R. Stephens, established a base on the Pororei River about 3,000 yards north of the Buin Road and thence scouted stealthily to discover the enemy’s tracks and dispositions on the Buin Road between the Hongorai and Pororei and on the Commando Road about the Huda River crossing. They found also a secret Japanese track, later named the Tiger Road.

On 21st April, Trooper Kemp24 and two others of the 2/8th Commando were sent out to obtain information along the Tiger Road and particularly

to obtain a prisoner. They moved out 2,000 yards and for five hours lay concealed a few feet from the Tiger Road. Finally when a single Japanese approached, Kemp leapt upon him, stunned him with a Bren magazine and brought him to the base.

On the 25th a patrol laid mines on the road and set an ambush. Some hours later eight Japanese arrived and all were killed by mines. Another patrol ambushed and killed four Japanese on the Commando Road and captured a map showing the enemy’s proposed defences south of the Hongorai crossing. Other patrols were operating farther east with equal effect. Natives with Lieutenant Clifton’s25 section on 23rd April killed four Japanese near Kapana and captured a lieutenant of the 4th Medium Artillery Regiment. The section inspected the Hari River crossing and on the 28th attacked an enemy group at Kingori, killing six. Lieutenant Barrett’s26 section sent patrols into the Oso, Taitai and Uso areas, and located near Oso a garrison of 80, which was then shelled by the artillery.

It was discovered that there was no suitable barge-landing point in the Aitara area or at Mamagota, and consequently the rate of advance would be governed largely by the speed with which the Buin Road could be made able to carry 3-ton trucks. Forward of this road supplies had to be carried by jeep trains travelling on corduroyed tracks or dropped from the air. Beyond the corduroy only tracked vehicles could travel, as a rule. Consequently, before the second stage of the advance – from the Hongorai to the Hari – could be completed, it was necessary to pause until enough stores had been brought forward.

It was now estimated that from 1,500 to 1,800 Japanese troops with probably nine guns, including heavy and medium pieces, were west of the Hari. Between the Hari and the Oamai were believed to be from 900 to 1,150 men with eight guns. The enemy could mount a counter-offensive only by withdrawing troops from the base and the gardens. To meet the Australian superiority in artillery, in tanks and in the air, they would need to concentrate behind a tank obstacle, and the next such obstacle was the Hari. A strong reason why they should fight hard on the line of the Hari was that the gardens to the east of it were large enough to feed a fairly big force, but if these gardens were lost, food would have to be carried from distant areas – a very difficult task, particularly in view of the loss of native carriers and the intermittent attacks by native guerrillas organised by Stuart’s party and Mason’s.

Savige issued new instructions: first to advance to the line Hari River–Monoitu–Kapana; and, in a second phase, to advance to the Mivo River. Again only one brigade group would be maintained in the forward zone, its northern battalion being supplied by air-dropping.

Thus the 15th Brigade’s battalions on the Hongorai spent the second and third weeks of May patrolling deeply into Japanese territory to gain

information and harass the enemy, and preparing for the next phase – the advance from the Hongorai to the Hari. The patrolling was intrepid. For example, on 10th May a small patrol led by Sergeant Langtry27 stealthily reached the bridge carrying the Buin Road over the Pororei River and, near by, spent half an hour concealed in a camouflaged bay containing a Japanese truck watching groups of up to 30 Japanese moving up and down the road. On the same day a patrol under Lieutenant Gay28 of the 57th/60th, with two native soldiers as guides, set an ambush at a river crossing about a mile east of the Hongorai. After an hour a Japanese came to the river to wash. Here was an opportunity to take a prisoner. One of the natives crept up behind the Japanese, hit him on the head with a stone, and hauled him screaming into the bush, where he was bandaged and eventually led back to the battalion’s area. In the course of this preliminary patrolling the 24th Battalion moved a company across the Hongorai and its patrols found a very strong enemy position estimated to be manned by 100 on what came to be called Egan’s Ridge.

On 13th May Corporal Boswell29 of the 24th Battalion led out a small patrol north of the Buin Road towards the Hongorai. It was surprised by about 50 Japanese armed with machine-guns, light mortars, grenades and rifles. Boswell and two men with him were pinned down and the others could not reach them because of the intense fire. Private Barnes killed one Japanese but an enemy machine-gun opened fire from the rear and a member of the patrol fell wounded in the fire lane. The men were now under fire from all the enemy’s weapons.

Lance-Corporal O’Connor30 crawled in a wide circle to the wounded man and dressed his wounds and then moved under fire to a second wounded man and looked after him too. The patrol withdrew covered by fire from O’Connor and Barnes. When Barnes’ Bren gun was almost out of ammunition O’Connor sent him to join the rest of the patrol and remained alone with his Owen gun until he thought that the patrol had all withdrawn. Then he ran to one of the wounded and was about to carry him out when three Japanese rushed at him with fixed bayonets. O’Connor killed two of these and wounded the other. He then dragged his wounded comrade back and for a time gave covering fire while a man who had been left behind withdrew.

On the Buin Road the 58th/59th was now taking the lead. Hammer’s plan was that, after a heavy air bombardment, it should make a wide flanking move on the right some days before the main assault. It would cut the Buin Road east of the Hongorai while the 24th made a frontal attack, and the 57th/60th on the left created diversions and attempted to attract the enemy’s attention in that direction. The right was chosen for

the main flanking move because there seemed to be only light Japanese forces there; it offered the shortest route to the Buin Road, which travelled South-east from the Hongorai to the Hari; and the Aitara Track would enable the final part of the flanking move – the move back to the Buin Road – to be completed without difficulty.

It thus became a task of the 58th/59th to explore the area south of the Buin Road. It sent out five or six-day patrols to set ambushes on the track from the Buin Road to the coast at Mamagota. The intervening bush was so dense and much of the ground so swampy that some patrols reached the track only in time to turn round and return before their rations were exhausted. However, on 10th May one such patrol on its first day out captured a prisoner on the Aitara Track.31 This Japanese said that 7 men of the I/23rd Battalion manned a coastwatching station at Aitara and four more a signal station 1,000 yards east of the point where the track crossed the Hongorai. A telephone line connected both posts and continued to a headquarters in the Runai area. He described how the weapons were sited. On the 12th two fighting patrols set out to attack each station simultaneously, the farther patrol laying a telephone line from the nearer. On the 14th Lieutenant D. J. Brewster leading the Aitara patrol found Aitara Mission deserted and by telephone ordered the other patrol (Sergeant Bush32 and eight men) to attack the signal post. This post was found to be wired and there were positions for thirty men, but only three were there and all were killed. The prisoner was examined again and revealed that the coastwatching station was not at Aitara Mission but at the mouth of the Aitara River, a mile away. Consequently on the 16th two patrols moved out to attack it and also to destroy a 47-mm gun at the signal station. They found that from 20 to 30 Japanese had now occupied the signal station. Major Pike’s33 company was moved forward to contain this post, which was harassed by mortars and artillery for the next four days while preparations for the main attack continued. Enemy parties made several efforts to reach the beleaguered party and eight Japanese were killed. A patrol to the Aitara area reported it clear of the enemy.

Meanwhile the battalion had sent several other patrols daily across the Hongorai to map the area through which it would advance, avoiding contact with the enemy so as not to reveal a special interest in the area. By the 16th all company commanders had a good knowledge of the country. Finally the engineers chose a crossing and a route thence to the Buin Road was surveyed. Major Sweet34 of the 58th/59th and Lieutenant

Willis35 of the 15th Field Company picked the area which the battalion would occupy. All this was done without the Japanese being aware of it.

It will be recalled that the 24th had found that a strong enemy force, perhaps 100 strong, occupied Egan’s Ridge, dominating the western approaches to the Buin Road. Captain C. J. Egan led out a platoon and two tanks in this direction on the 15th but a tank bellied on a log. As mechanics advanced to help the crew, the Japanese opened fire with a gun and small arms. A 155-mm shell hit the tank killing the gunner, Trooper Hole,36 and wounding three others and wrecking the tank. An attack which followed was beaten off and the little force withdrew.

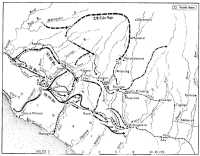

Although the main attack across the Hongorai was not to open until 20th May the diversionary advance by the 57th/60th was to begin three days earlier. On the eve of this move Hammer issued an order of the day in a characteristic style. He spoke of his “undying admiration” for and “extreme confidence” in his men and told them that the next few weeks might see the major defeat of the Japanese in south Bougainville. “Go to battle as you have done in the last month and no enemy can withstand you.”

In preparation for the attack and in support of it the four Corsair squadrons of the RNZAF – Nos. 14, 16, 22 and 26 – carried out the biggest operation of this kind which the force had undertaken in the Pacific. For eight days from 15th to 22nd May the squadrons attacked along the axis of the Commando and Buin Roads. Each day, except one, from 40 to 63 sorties were made. A total of 185 1,000-lb and 309 lighter bombs were dropped.37

On 17th May, supported by 32 Corsairs overhead and the fire of two batteries, the 57th/60th crossed the upper Hongorai and advanced on a wide front astride the Commando Road. The centre company crossed 500 yards north of the ford. The tanks could not negotiate the ford but the infantry attacked down the far bank sending the Japanese off in wild disorder. By 11.35 a.m. the Commando Road beyond the river was secured. Captain J. D. Brookes’ company made a wide outflanking move to the Pororei River through difficult country, but reached it at dusk driving off the few Japanese who were at the crossing.

Captain Ross’38 company, led by native guides, also went wide to cut the road at the Taromi River, 3,000 yards to the south, and Major Wilkie’s39 went north to the Huda River. Next day the infantry pressed on. Brookes’ at the Pororei crossing was attacked by 30 Japanese but after a hard

18th May-16th June

fight repulsed them, losing one man (Private Gulley40) killed and eight wounded while the Japanese left seven dead. Next day Colonel Webster’s headquarters were established on the Torobiru River, a dropping ground had been prepared and supplies dropped; the battalion had seven days’ rations, ambushes were established (seven Japanese were killed in ambushes that day) and the battalion was ready to fight again. On the 20th it began patrolling. One party under Lieutenant Paterson,41 scouting far to the south, found a well-dug Japanese position, set an ambush and killed five, including a sergeant carrying useful documents.

That day, on the Buin Road, the main attack opened. From 8 a.m. until 8.20 on 20th May aircraft bombed the enemy’s positions along the road and at 8.30 the 24th Battalion advanced behind a creeping barrage of artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire and with two troops of tanks. Two of the three leading companies soon gained their objectives; the third was held up just short of it by heavy Japanese fire from small arms and artillery, and dug in, having lost 4 killed and 5 wounded.42 Next day it fought its way to a position dominating the Pororei ford, but Japanese were still road farther west; a patrol holding strongly astride the from a supporting company under Lieutenant Spendlove met a group of some seventy and dug in just west of them. When Captain Graham’s company occupied the high ground on Egan’s Ridge it found the whole area to be sown with mines and booby-traps; there were tank mines in the road and booby-traps in the scrub on each side of it. The bomb disposal squad which began working on the mines was blown up, two men being killed. Thereupon all through the morning of the 21st Lieutenant Syrett43 of the 24th’s Pioneer platoon and

Sergeant J. A. C. Knight searched for and disarmed mines. At first they used the only available mine detector, but, after it had failed to respond to three improvised mines, Syrett and Knight probed with bayonet and fingers and cleared all mines and traps from the area.

Meanwhile the 58th/59th’s wide flanking move on the right had begun along a route bulldozed to the west bank of the Hongorai. On the 18th and 19th there had been some sharp patrol clashes beyond the Hongorai. On 20th May the final pad had been cut to the Aitara Track and tractors had dragged ten trailers loaded with supplies across the river at Mayberry’s Crossing. A powerful tractor, newly arrived, dragged the tanks through the deep mud and across the river. Despite the noise the Japanese were evidently oblivious of all these preparations. By 4 p.m. that day the whole battalion except headquarters and the Headquarters Company were in an assembly area east of the Hongorai. Before dawn on the 21st the complete battalion was formed up ready to advance. At 6.30 a.m. Major Pike’s company (he had played a leading part in the preliminary patrolling) with Lieutenant Scott’s tanks set off eastward. A creek 400 yards forward delayed the tanks so Pike left a platoon with them and advanced with the remainder but was held by some 40 Japanese dug in another 400 yards on. It took a bulldozer an hour to make a crossing over the creek and it was 9.30 a.m. before the tanks reached the forward infantry. They advanced straight up the track sweeping the enemy’s position with fire and after half an hour the Japanese broke and fled in disorder, leaving seven dead. Early in the afternoon the battalion was on its objective covering the Buin Road and digging in against the expected counter-attack. Their guns shelled one company position and caused some casualties.

A patrol on the left flank was pinned down by heavy fire from north of the road. Tanks moved forward and fired into the enemy position so effectively that the Japanese fled leaving a 70-mm gun in perfect order, with 100 rounds of ammunition. By nightfall all the objectives had been secured and most localities had been wired in; but the Japanese did not make a counter-attack, probably because an attack so far to their rear had disorganised them.

On 22nd May the powerful tractor mentioned above, dragging a trailer train to the headquarters of the 58th/59th, was ambushed by about 20 Japanese with a 47-mm gun. The tractor was hit and disabled but the escort, reinforced, drove off the attackers and took their gun. On 26th May Captain Hocking’s44 company encountered 20 Japanese astride the Buin Road and drove them off, but booby-traps killed Lieutenant Putnam45 and wounded 11 others. The Buin Road was now open for traffic, and fighting patrols had mopped-up the whole area and taken a number of prisoners.46

In ten days about 500 bombs of up to 1,000 pounds in weight, 7,800 shells and 3,700 mortar bombs had fallen on and about Egan’s Ridge. The Japanese endured nine days of this bombardment but after the final blasting, on the 22nd, the infantry advancing to attack found the area abandoned.

The positions once occupied by the enemy were completely buried under huge piles of debris and the whole area was barren and scarred with shrapnel (says the report of the 15th Brigade). The consistent accuracy of our bombing, shelling and mortaring was evidenced by the complete devastation of the whole area and the destruction of the enemy positions, which were the strongest yet encountered during the operation. A strong odour of dead was noticeable throughout the area but the destruction ... was so complete that it was impossible to make any search of the original positions for bodies or for abandoned equipment or documents.

The plan had succeeded brilliantly: the enemy forces west of the Hari had been broken. In the attack the 24th Battalion had killed 54 and lost 7 killed and 26 wounded; the 58th/59th had killed 36 and lost one killed and 16 wounded; the 57th/60th had killed 16 and lost 5 killed and 22 wounded.

On the northern flank the 57th/60th now pressed on towards the Oso junction. An attack by three companies was launched on 27th May with the support of aircraft and artillery, and the junction was secured with few casualties. In the new position the 57th/60th were harassed by night raiding parties and artillery fire – the first encountered on the northern road. In one bombardment on 30th May the first shell, bursting in the trees, killed or wounded nine. The same day a Corsair mistakenly strafed one of the companies of the 58th/59th Battalion on the Buin Road and machine-gunned battalion headquarters, killing the Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Wheeler,47 and wounding the adjutant, Captain R. L. Mathews, and three others.

On 2nd June Corporal Biri, a Papuan soldier of 5 years’ service, was sent out with three others to the right flank of an ambush position which was being constructed by 12 Japanese near the Sunin River. When in position near them Biri attacked alone and killed one. The Japanese tried to surround the natives but Biri without trying to take cover set upon them, firing his Owen and hurling challenges and abuse, and kept them from moving. When his Owen jammed he took a rifle and shot two more Japanese whereupon the survivors fled.48

On 2nd June the main advance was resumed, the 58th/59th moving forward without opposition through positions which had been “completely devastated by air, artillery and mortars”. “Not one enemy was found alive or dead,” wrote the battalion diarist, “although a strong smell of death pervaded the whole area.” A prisoner taken later in the day said that the air strike had completely demoralised the defenders, and when they heard the tanks approaching they had fled. On the left the 57th/60th reached the Sunin River against slight opposition. On the 3rd and 4th

the 58th/59th continued the advance, moving slowly because of the need to disarm an unprecedentedly large number of mines and booby-traps-more than 100 in three days – until they reached the Peperu River. Patrols moving stealthily forward to the Hari and across it found evidence of much confusion, many positions dug but unoccupied, and small groups of Japanese at large. It was decided to attack frontally towards the Hari next day.

However, on 6th June many difficulties were encountered. By 12.30 p.m. Captain Bauman’s49 company had advanced only 300 yards when it encountered a strong enemy force that had evidently just come up. This was driven out, but 200 yards farther on, on an escarpment, was another enemy force commanding the whole area. Lieutenant Dent,50 commanding the supporting troop of tanks, directed Corporal Cooper’s51 tank forward. It bogged and drew heavy fire. Dent took shelter behind it. Corporal Burns52 tank advanced and gave support and a bulldozer was brought forward but abandoned after three men had been wounded trying to tie a tow rope to the tank. At length Sergeant Moyle’s53 tank towed Cooper’s out and then went forward again to retrieve the bulldozer. Under sharp fire Dent and Lieutenant Dunstan54 of the engineers attached a tow rope and Moyle’s tank dragged the bulldozer to safety. In the day’s fighting four Australians, including Bauman, were killed or fatally wounded and sixteen others wounded.

Next day the 58th/59th and tanks, impeded by swampy country, a road scattered with mines, and intermittent shellfire, made some progress against strongly-held Japanese positions. On the 8th Captain E. M. Griff’s company of this battalion was sharply attacked, Griff being wounded – the third company commander to become a casualty in a few days.

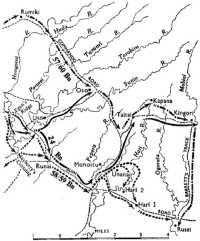

On 9th June General Blamey visited the 15th Brigade. “Take your time, Hammer,” he said to the brigadier. “There’s no hurry.” It was now clear that the Japanese intended to resist strongly along the approach to the Hari on the Buin Road axis; and the far bank of the Hari was a high escarpment. Hammer therefore decided that the 58th/59th would make a shallow outflanking march to the north and cut the Buin Road some miles cast of the Hari while the 57th/60th thrust wide to the south on the far side of the Ogorata and cut the same road near Rusei. At the same time a company of the 24th would operate south of the Buin Road east of the Hari. Success would carry the brigade not only across the Hari but the Ogorata and through a large garden area valuable to the enemy.

At a conference on 24th May Bridgeford had expressed the opinion that with his present resources he could not reach Buin before the end of the year. Savige informed him that later he would place the 11th Brigade and the 4th Field Regiment under his command. In the meantime his task was to cross the Hari and push on to the Mivo. Beyond the Hari the 15th Brigade should be relieved by the 29th.

Savige’s intention was to advance the 29th Brigade to the Silibai along the present axis. He considered that the enemy would be drawn into the south Silibai area and would denude the northern flank. He then hoped to find a way in on the left flank for the 11th Brigade even if it had to be supplied by air. The 11th Brigade might then attack the Japanese right flank and inflict a decisive defeat. The task of the 2/8th Commando was to reconnoitre a route for the 11th Brigade. With this project in mind Savige on 30th May spent nearly three hours on an air reconnaissance of the Mivo area and the road systems north of Buin. As a result he decided that a movement along the Commando Road, and then on to the lower foothills across the Mivo and Silibai Rivers, and finally an attack southwards would be practicable.

As part of the plan to advance to the Mivo two large patrols from the northern flank were sent out to circle deep into the enemy territory exploring the Commando Road and routes leading south from it to the Buin Road. One commanded by Captain Scott55 of the 57th/60th numbered some 180 men and included one tank troop, one infantry platoon (Lieutenant Gay), engineers with a bulldozer, and other detachments. It was to advance from Kapana to Kingori destroying the enemy in that area, then south to Rusei – more or less the route of the 57th/60th’s advance. One of its objects was to create the impression that the Australians were operating strongly along the northern axis. Another force of the 57th/60th under Lieutenant G. H. Atkinson, about 70 strong, was sent out far along the northern flank to establish a base at Musaraka on the Mivo and obtain information. This was on the fringe of the commando country and both patrols would be dependent on track information obtained by the commando patrols.

The advance of the 57th/60th began on 11th June, that of the 58th/59th on the 12th. The plan of Colonel Mayberry of the 58th/59th was to send two companies and two troops of tanks under Major Pike to gain a position astride the road 2,000 yards east of the Hari, whence a third company, having followed behind, would thrust westward to the Hari taking the enemy in the rear. One company remained near the Hari ford. For four days before the advance began the two artillery regiments and the New Zealand Corsairs had bombarded the area until “it resembled Australian bush after fire”. By the early afternoon “Pikeforce” had made its long march and was astride the Buin Road, having encountered little opposition. On the 14th Pike moved east with most of his force towards the Ogorata while one company went west towards the Hari to clear the

main road to Pikeforce. In the day the eastern company advanced about 700 yards against stiff opposition; the western company encountered a resolute and well-sited group of Japanese dominating the ford, and between it and the company on the other side of the river.

Daring tactics such as these created situations that could be highly dangerous to supporting troops. At 10.30 a.m. on the 14th a reconnaissance party of five led by Lieut-Colonel Hayes56 commanding the 2/11th Field Regiment came up to Captain C. C. Cuthbertson’s company, which was on the west side of the ford, and (according to the diarist of the 58th/59th Battalion) did not heed a warning but continued along the road. Major Dietrich,57 however, who was just behind Hayes, heard no warning. At the Hari ford Hayes and his party climbed a 40-foot escarpment beside the road and soon were joined there by Major Pearson58 and two others. Suddenly Japanese opened fire. Captain Winton59 who was disarming a booby-trap about 100 yards short of the ford was wounded. The artillery party fired back at the enemy; Dietrich organised covering fire and with two others went forward and brought Winton in. Meanwhile Hayes had been killed by a mine. Three others were wounded.

The ford was not occupied until next day after a heavy bombardment. The road was opened late in the afternoon, but not before some 40 Japanese had suddenly attacked Cuthbertson’s company as it was moving east. In the fierce fight which followed two Australians and four Japanese were killed, but this was the last time Japanese appeared on the Buin Road west of the Ogorata, where Pikeforce was now securely dug in.

For its long move through the bush, which began on 11th June, Colonel Webster streamlined his 57th/60th Battalion to three companies, each about 80 strong, a headquarters of 60 and 120 native carriers. The men made slow progress, hacking their way through trackless bush, but achieved almost complete surprise. On the second day the battalion reached a track from Kingori to Rusei – named Barrett’s Track after Lieutenant Barrett of the 2/8th Commando. Here some Japanese appeared and a sharp fight followed, but Webster and the main part of the battalion continued on towards the objective. They expected to reach the Buin Road on the 13th but found no sign of it. Next day they pushed on, through swamp and dense bamboo and sago. Seven Japanese were killed in small clashes. It was not until 3.45 p.m. on the 15th that the road was reached.

Meanwhile Scott Force had set out for Kingori on 9th June. The bulldozer and tanks made painfully slow progress, men from the tank crews and such infantry as could be spared having often to corduroy the saturated track with logs before the tanks could move through. On the second day Papuan scouts reported that the enemy was dug in not far ahead.

The tanks formed a perimeter. The artillery observer, going forward to direct fire on the Japanese, was wounded. It was the 12th before another artillery observer was forward and fire could be brought down. The tanks advanced and the enemy fled. Thence the force moved slowly to Kapana, through sodden country cut frequently by creeks, and on to Kingori along a good track. At the Mobiai a Papuan patrol was ambushed but extricated itself after inflicting casualties. Scott now turned south towards Rusei along Barrett’s Track, which the 57th/60th had already crossed in the course of its advance to Rusei. That afternoon a Japanese field gun concealed by the road opened fire on the leading tank (Corporal Matheson60) but the tanks promptly silenced it. On the 16th Scott reached the Buin Road at Rusei and joined the main force. What had this laborious thrust achieved? It demonstrated that tanks could go through the most difficult country with the help of a bulldozer and the labour of infantrymen. Incidentally the tanks maintained the only contact between the 57th/60th Battalion, after its line was cut by the Japanese, and Hammer’s headquarters. One tank was in wireless touch with the battalion, the other with squadron headquarters at 15th Brigade.

That morning an armoured patrol from the 58th/59th advanced towards the 57th/60th. On the way a tank was blown up by a mine. The driver, Trooper Dunstan,61 was killed and the remainder of the crew wounded. The tank lurched into the crater with its engine racing. It could not be stopped because the turret had jammed and the engine raced until it seized. At midday the patrol reached the 57th/60th. Success was now confirmed. On Hammer’s orders Webster prepared to send a company eastward towards the Mobiai, and traffic began to pour along the Buin Road to the battalion now, after six days in the bush, linked by a vehicle road with the main force.

“The mass arrival of stores, tanks, jeeps and bulldozers at the one area made a complete traffic jam,” wrote the diarist of the 57th/60th. Three troops of tanks and two bulldozers were soon on the spot. It was 3 p.m. before the leading company (Captain Martin62) was able to move off with a troop of tanks (Lieutenant Fraser63). After advancing only 400 yards from the traffic jam a 150-mm gun 350 yards away hit the forward tank whose magazine exploded killing Trooper Dew,64 the driver, and wounding Fraser and the others of the crew. The tank was hit twice more and destroyed. It was evident that the Japanese were still in strength west of the Mobiai and determined to make the Australians pay heavily for any ground they gained there. But great success had been achieved. “Thus ended the battalion’s last, and undoubtedly its most spectacular,

major action in the 1939-45 war,” wrote the historian of the 58th/59th. “In 13 days, from 3rd to 15th June, 13,000 yards of territory had been gained from a numerically superior enemy.65

It will be recalled that while the main attack from the Hari towards the Mobiai was in progress Atkinson Force (of the 57th/60th) was to move deeply into Japanese territory. It set out on 7th June, moved through Kapana to Katsuwa where it linked with a patrol of the 2/8th Commando, and thence to Astill’s Crossing on the Mivo River where it turned south and formed a patrol base in the river bed 1,000 yards south of Musaraka. Next morning a returning line of native carriers encountered some 30 Japanese about 300 yards from Astill’s Crossing. The leading escorts engaged the Japanese and the “kai-line” was sent back to the base. Three hours later a second attempt was made to push the kai-line through but again the enemy were across the track. In the light of these events, and of information from the 2/8th Commando that some 60 Japanese were shadowing his force, Lieutenant Atkinson struck camp and moved 3,000 yards north along the east bank of the river. There a new base was formed on the 11th (the main attack had now opened) and thence patrols operated until the 17th, when Atkinson learnt from the 2/8th Commando and Stuart, the guerilla leader, that there were some 180 Japanese round Kingori and perhaps 100 hunting Stuart farther east. Consequently on 18th June Atkinson again moved his base, this time 1,000 yards to the north-west, farther from the Japanese main force and deeper into the commando country.

On the 19th a company of the 24th Battalion under Captain S. C. Graham set out from Taitai through Kingori, where another company of the 24th had established a base on the 14th, to relieve Atkinson. Next morning Lieutenant C. A. Graham66 of this company was leading a patrol towards Katsuwa ahead of the main column when he encountered about 30 Japanese. A sharp fight followed in which three Australians were wounded, and a number of Japanese were killed or wounded. The main body of the company advanced in extended line to join the patrol then withdrew with it to enable artillery fire to be brought down. Before the guns opened fire Captain Graham was wounded in the foot by a sniper. Lieutenant Whitebrook67 took command, the enemy were outflanked, and that night the Australians bivouacked on the Koroko River.

On 21st June they moved on through very difficult country, failed to find Katsuwa and instead established a perimeter at a clearing sloping upwards from the river and marked on their map as a likely dropping ground. They set about improving this dropping ground.

Next morning, when most of the force was on patrol and only a handful were left defending its area of the perimeter, some Japanese scouts were seen in the bush. They were fired on and disappeared. About half an

hour later mortar bombs fell into the perimeter and what seemed like 100 Japanese attacked with fanatical zeal. The fight lasted for two hours. Japanese thrust forward to within a few yards of the posts held by the cooks, under Sergeant Erbs,68 and one man leapt into a weapon-pit and was clubbed to death. The Australians’ ammunition was almost exhausted before the Japanese withdrew, leaving 18 dead. Their fire was wild and no Australian was hit.

Meanwhile Sergeant Langtry, who had led out a patrol before the attack opened, found a strong enemy position astride the Commando Road near Kingori. He attacked but the enemy was too strong. Thereupon he telephoned for artillery support, and moved close to the enemy to direct fire. In the subsequent attack Langtry found the position even larger than he had thought, by-passed it and rejoined his company. When he arrived the company was being fiercely attacked, but he made an encircling move, joined it and helped in the defence.

The company at Kingori had heard the firing in the far distance. At length Private Lancey,69 a signaller with the company that was being attacked, managed to gain wireless contact with the rear company and it relayed the news to battalion headquarters. Consequently during the afternoon an aircraft made several visits, dropping ammunition and wire to Captain Graham’s force. Next day the perimeter was fenced and the artillery ranged on to the wire; the Japanese did not attack again. On 24th June Atkinson Force moved back through Graham Force.

Throughout the period of the 15th Brigade’s attacks the 2/8th Commando had been probing forward on the inland flank. On 10th May Captain Dunshea set off to establish a new base near Monorei, near the headwaters of the Mivo. The Tiger patrol (now two sections under Captain Barnes70) laid ambushes on the Tiger Road, killing ten and capturing the Regimental Sergeant-Major of the 13th Regiment. The enemy was now becoming more alert and cautious, and fewer of his foraging parties were to be found moving about. At this stage, after a conference with Brigadier K. E. O’Connell, commanding the artillery of the 3rd Division, it was arranged that an artillery liaison officer (Captain Bott71) be attached to the squadron and forward observation officers be attached to patrols to increase their hitting power.

The first such patrol went out from 19th to 26th May into the Taitai and Monoitu areas. It encountered a difficulty already suffered by some earlier commando patrols: the danger of moving behind the Japanese lines now that the supporting artillery and air bombardments were so heavy. The artillery, for their part, were embarrassed by the large areas that should not be shelled because of the possible presence of commando patrols.

Eventually it was decided that Major Winning’s patrols should not operate within range of the close-support artillery of the brigade.

On 24th May the headquarters of the squadron was opened at Moro-kaimoro. General Bridgeford had issued an order on 23rd May increasing the strength and re-defining the role of the force on his inland flank. Winning was given command of “Raffles Force”, consisting of his own squadron and Captain G. L. Smith’s company of the Papuan Infantry Battalion. Its task was to collect information on the flanks and ahead of the main force and harass the enemy’s rear.

Winning was disappointed in the results obtained by the Papuan company. The Papuans were successful on fighting patrols of certain types but not in reconnaissance or artillery strikes.

Discipline was not impressive (he wrote), probably due to insufficient Europeans in the establishment. Apart from the company commander, the platoon commanders and sergeants lacked battle experience and experience with natives. The native soldiers feared artillery and would not accompany FOOs forward. It was considered more aggressiveness could have been shown on several patrols, and, on investigation, it was found there was friction and mistrust between the Buka natives and the Papuans, who had secretly threatened the Buka guides not to lead them to any targets which could not be overcome easily, or from which escape was likely to be dangerous. This led to considerable use of PIB for escort and security patrolling. ... The final attitude was that where a definite position for attack could be given, good results could be expected, but it was unwise to give PIB patrols general areas of operations for strikes and ambushes as was done with squadron patrols.

At the new Morokaimoro base huts were built and a strip for Auster aircraft begun. Meanwhile arduous and effective patrolling continued. The report of the squadron gives some examples of the patrol achievements of Captain Dunshea’s men, usually in two-men parties with a few natives, between 17th and 31st May: found a group of huts near Ivana River, which was later raided; found and brought down artillery fire on a strong enemy group near Irai; found a field gun which aircraft later destroyed; placed observation posts on the Buin Road which reported movement including the first arrival of naval troops; captured a lieutenant of the 23rd Regiment; patrolled the coast near the mouth of the Mivo, finding an enemy group and reconnoitring for a possible beach landing.

On 26th May Lieutenant Clifton’s section laid an ambush on the Buin Road 400 yards east of the Mobiai ford. A party of 16 entered one end of the ambush while 6 entered the other; 17 were definitely killed and possibly 2 more. Farther east Lieutenant Killen’s section, making a series of patrols in the Buin Road area near the Mivo, ambushed a truck near the Mivo crossing and killed 7 of its 10 occupants. Next day it set a nine-man ambush near the Mobiai ford and soon opened fire on a party of Japanese, but almost immediately the Australians were attacked by about 90 Japanese following behind, evidently as part of a pre-arranged drill controlled by whistles. After a fight in which it was estimated that 19 Japanese were killed, the patrol withdrew having had only one man wounded; these Japanese were naval troops – the first encountered in southern Bougainville. Ambushes were set and raids made on enemy

camps at frequent intervals. On 2nd June a patrol was sent out to destroy a Japanese post in a garden on the Mobiai, 1,500 yards north of the Buin Road. With two natives Trooper Guerin72 crawled to within a few feet of the enemy position, then stealthily placed the patrol in positions only a few yards from the enemy. Guerin then led in the attack. One machine-gun began firing from a covered position. Guerin charged and killed the crew with his Owen. Eighteen Japanese were counted, possibly two escaped. No one in the patrol was hit. Later 11 Japanese were killed in an ambush near the Mivo ford; on 16th June Lieutenant Perry’s section killed 7 in the same area. However, the main artery in this area – the Buin Road – was so well patrolled by the Japanese that Australian and Papuan patrols had only limited success along it.

During April and May Stuart’s Allied Intelligence Bureau party based on Sikiomoni had been sending in detailed information and engaging in guerilla warfare “on the small scale which their position and task per-mitted” – they were primarily a source of Intelligence. In May they reported the killing of 197 Japanese, mostly with booby-traps. On 17th May Stuart moved his base South-eastward but in June a large enemy force set out to disturb him and he moved eventually into the Mount Gulcher area.

After the war Japanese officers said that in the several severe clashes at the Hari and Ogorata River crossings the uniformity of the Australian tactics – a wide outflanking move to the north accompanied by an artillery barrage – enabled General Akinaga to anticipate the course of action and withdraw before encirclement, using minor tracks parallel to the Buin Road. Since his guns could not be withdrawn across the rivers, the crews were ordered to site their guns for direct fire on advancing tanks. One tank knocked out was considered worth the loss of a gun. The gun crews were allowed to escape as soon as they had hit a tank.

The Japanese were critical of the Australian tactics of repeatedly making a wide outflanking move through the bush combined with a thrust by tanks along the main track. They declared that, because of the weight of the Australian armour, artillery and air support, each river crossing could have been secured more easily by the thrust along the main track combined with a small outflanking movement each side of it. (Hammer’s tactics, however, succeeded.)

It will be recalled that in May Seton had relieved Mason as guerilla leader in the Kieta area. According to the report of the II Corps, Seton was by training and predisposition “eminently suited to lead a band of killers”. This warrior decided to maintain his headquarters above Kieta which he was determined to capture if he could, and at the same time to send a patrol under Lieutenant Lovett-Cameron73 and Sergeant Cross74 along the Luluai Valley and one under Sergeant White and Corporal McGruer75 north to the Vito area. Lovett-Cameron took up a position covering the Toimonapu, Kekere and Aropa Plantations and, with local partisans, made a series of raids on enemy camps, killing 213 Japanese

in three weeks. They returned to Sipuru on 4th August. White’s patrol was less successful, partly because White himself fell ill. However, valuable information was obtained and, in August, an attack on Rorovana killed 32 Japanese.

Mason’s guerilla operations, continued by Seton, seem to have been without parallel. Never more than seven Europeans and generally only three took part. When Mason set out he encountered enemy troops only four hours’ walk from Torokina, but in a few months his native guerrillas had established a reign of terror among well-armed and trained Japanese forces which numbered nearly 2,000 in the Kieta area alone, and in August Seton was preparing to attack and capture Kieta itself. It was estimated that in eight months the partisans killed 2,288 Japanese. For evident reasons nothing was published at the time about the remarkable achievements of these and other guerilla leaders. The work in 1941–1944 of the coastwatching organisation from which most of them were drawn was fully and eloquently described after the war by Commander Eric Feldt in The Coast Watchers, but little was published about their guerilla and scouting operations in the final year of the war, and singularly few decorations were bestowed on the leaders for service in that period.

It has been mentioned that from the outset the Australian commanders had disagreed with the direction from General MacArthur’s staff that a brigade should be employed in garrisoning Munda and the outer islands – Emirau, Green, Treasury. In December General Savige had submitted to General Sturdee that three companies would suffice, enabling the remainder of the 23rd Brigade to be concentrated at Torokina in reserve. It was not until about three months later – on 20th March – that MacArthur’s approval of this plan was received, and so few ships were available that another six weeks passed while the brigade was brought to Bougainville. One company of the 8th Battalion remained on Emirau Island, one on the Green Islands and one was divided between the Treasury Islands and Munda. In June Savige was given permission to withdraw even these companies and the entire brigade was concentrated at Torokina. During its period on the outer islands the brigade, anxious for action, had made a number of small expeditions; there would have been more if General Savige had not restrained the enthusiasm of Brigadier Potts. In November one patrol of the 7th Battalion captured an isolated Japanese on Mono Island in the Treasury group and, as mentioned, another explored Choiseul Island. Patrols of the 27th Battalion discovered that no Japanese remained on several hitherto-occupied islands north of the Green Islands; troops of the 8th Battalion supported an Angau patrol which spent three weeks on New Hanover.

The freeing of the 23rd Brigade enabled Savige to hand over the central sector to it, thus reducing the responsibility of the 11th Brigade to the northern sector. On 19th April Potts took command of the central sector where his 27th Battalion had relieved the 31st/51st. He was ordered not to advance beyond Pearl Ridge, except with patrols. The information

brought in by early patrols convinced Potts that the Japanese holding the Berry’s Hi11-Hunt’s Hill area numbered from 40 to 50, and were reinforced from time to time. It was decided to send strong fighting patrols against them.

From 8 a.m. on 10th May twelve Corsairs dropped depth-charges on and machine-gunned Berry’s Hill and Little Hunt’s Hill for nearly an hour, and from 9 a.m. to 11.25 the field guns and mortars bombarded them. In the afternoon a patrol under Lieutenant Mills76 advanced through dense bush on to Little Hunt’s Hill which had been cleared of foliage by the blast of the depth-charges. After a short exchange of fire in which one Japanese was killed the hill was taken. It appeared to have been occupied by only about ten men. Four Japanese courageously tried to reoccupy the position; two were killed and the others fled. The occupation of this hill brought the forward Australian posts to within 450 yards of Berry’s Hill.

Lieut-Colonel Pope77 planned to take Berry’s by sending four strong patrols against it after an air strike. A whole squadron of the New Zealand Air Force dropped bombs on and round Berry’s in the morning of the 13th and the patrols moved out. Soon sharp firing was heard from Berry’s and later Lieutenant Wolfenden78 telephoned to Pope that the Japanese occupied it in strength, whereupon “in view of Corps’ no casualty’ policy” Pope ordered a withdrawal. One Australian had been slightly wounded.

However, reports that Japanese with packs on had been seen moving over Berry’s led Pope, on 16th May, to decide that it was being abandoned and Wolfenden was again sent forward with a patrol. After calling for artillery fire Wolfenden’s patrol advanced on to the hill and found it abandoned. Captain McGee.79 then moved the remainder of his company on to the hill, which had been battered by the air and artillery bombardment. Every post had been hit, the vegetation had been flattened, and several partly-buried corpses and 16 rifles lay around. In the patrolling on earlier days 12 Japanese had been killed on Berry’s; a total of about 40 had been killed there by this battalion or the artillery, the Australians losing 3 killed and 2 wounded.

Meanwhile two platoons under Captain Lukyn80 had been harassing the Japanese garrison of about 15 in the Sisivie area, hoping by continual sniping and harassing to eliminate them. By the 20th it was estimated that 8 had been killed.

23rd Brigade, April–June

A patrol led by Sergeant Gilligan81 on 17th May to ascertain whether the enemy still occupied Wearne’s Hill and Base Point 3 and harass him, approached Base Point 3 stealthily and found Japanese in position astride the track. Gilligan took one man and a native round a flank and the

patrol attacked. In a sharp fight lasting 20 minutes eight Japanese were killed and a machine-gun was destroyed before the patrol, under fire from a patrol of six Japanese, withdrew. No Australian was hit.

On 18th May Lieutenant Tiernan82 led a patrol to spend five days out in the bush and examine Tokua. They found it and observed the enemy

for some time; there were 15 to 20 Japanese well dug in. Artillery fire was brought down on the Japanese positions. The patrol report mentions that on the third day a local native armed with one grenade joined the patrol.

From 22nd May onwards a series of patrols were concentrated against Wearne’s Hill and Base Point 3. Each moved out and either probed in a new direction or occupied a position from which a further bound could be made.

Early in June Colonel Pope knew that he would soon be relieved by the 7th Battalion. The order that no attack should be made in the central sector had now been lifted, and he decided to take advantage of this change of policy by sending in a company to attack Tiernan’s Spur. On the 3rd, after sharp artillery fire, Lieutenant Tiernan’s platoon attacked a ridge held by the enemy 200 yards short of the main feature. After a sharp fight it took the position killing 9 Japanese; 5 Australians were wounded. The enemy counter-attacked the company next day without success.

In May and June the 23rd Field Company vastly improved the supply line to the force on the Numa Numa trail by constructing a powered haulage up Barges’ Hill. It comprised a 2-foot gauge railway, rising 894 feet in 2,245 feet and with a maximum grade of 1 in 1. It handled 25 one-ton loads a day (600 carrier-loads), and relieved 200 natives for carrying farther forward.

The Papuan Infantry Battalion (Lieut-Colonel S. Elliott-Smith) had arrived at Torokina in May. One company was attached to the 15th Brigade, one (as mentioned) to the 2/8th Commando, one to the 27th Battalion at Pearl Ridge, and one to the battalions in the northern sector. These troops were soon engaged on long-range patrols in all sectors. For example, from 25th May to 5th June a platoon of the Papuan Infantry Battalion under Lieutenant Burns83 made a notable patrol lasting twelve days, the object being to cut the enemy’s track at Mapia and ambush and destroy any Japanese who were encountered. They thoroughly explored the enemy’s line of communication, twice ambushing parties travelling along it. On the third day they killed 4 out of a party of 25, on the seventh 7, and on the twelfth day reached home without having lost a man.

In spite of the restrictions imposed on it the 27th came out of the central sector in early June a unit experienced and tested in bush warfare. In six weeks its men had made 48 patrols, and, moving stealthily through the enemy-held area, had launched several small-scale attacks. It had killed 122 Japanese, losing only 4 killed and 9 wounded.

At this stage Savige planned to land a company of the incoming battalion – the 7th – from a corvette on to the coast north of Numa Numa.84 The plan was abandoned, however, because of the lack of reliable information

about the Japanese strength in the area, and because of the difficulty of supplying even a company there.

For the first four months of the year the Japanese saw nothing to shake their conviction that the Australians would not try to advance overland to Numa Numa. In May, however, they found the Australians (the 27th Battalion) more aggressive and moved back their main strength. In this period they had about 350 men in the forward zone, and about 600 in reserve at Numa Numa. Their orders were to make deep outflanking movements, set ambushes and strike at supply trains. From June onwards, after corvettes had bombarded the north-east coast, a sea-borne landing at Numa Numa was expected daily. This threat added to that of a possible move south along the coast from Ruri Bay, led to the establishment of a composite battalion north of the Wakunai River to meet either contingency, and six field guns were sited for coastal defence.

Meanwhile Flight Lieutenant Sandford had been harassing the Japanese with increasing severity. By the end of May his natives had reported having killed 211 and he was able to patrol from Teopasino to Tinputz without meeting a Japanese. His party then moved south and surprised a body of Japanese troops who had retreated from the north or fled from Inus after air and naval bombardments and were busy building a camp. “The entire complement of 195 was wiped out.” In June the camp was reoccupied and Sandford attacked it again, killing all the 50 or so occupants, for a loss of two natives killed. The camp was again reoccupied, this time by more than 300. New Zealand aircraft attacked it on 17th June and about 160 of the Japanese began to flee northward. Sandford’s party pursued them and killed 10.

At this stage Captain Robinson85 was moving into the mountains to relieve Lieutenant Bridge. When he heard a signal from Sandford that about 50 Japanese were moving in his direction, he decided to ambush them and set out to find a suitable position on the Ramazon River where he set three ambushes. On 20th June his men captured two Japanese. On the 22nd he was told from Torokina that 100 more Japanese were on their way towards him. Next day one of his patrols sent word that 50 to 60 Japanese had crossed the Ramazon, 18 had been killed and others hit. Robinson sent word to Aravia and Lumsis villages to muster as many men as they could and join him. On 26th June about 60 Japanese were ambushed near Raua Plantation. The Japanese returned the fire then broke away dragging many wounded. Two police boys were hit but not fatally.

On 29th June one of Robinson’s patrols clashed with a party of more than 100 Japanese near Rugen Plantation. After fighting for two hours the Japanese withdrew to a hill in the plantation leaving a captain and 6 others dead. From 8th June to 4th July this party killed 45 Japanese.

Early in July Sandford was relieved by Captain J. H. Mackie.

When [Sandford’s] party went into the field few of the natives were friendly, many were bitterly hostile and openly fought with the enemy. Moreover Sandford had had little experience with the AIB previously. Largely by personal influence

Sandford won the natives’ support and formed a fighting force of three platoons, each 35 strong, and by splendid organisation and personal leadership welded them into a force which accounted for over 500 Japanese killed.86

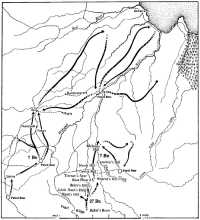

Early in April (while the Slater’s Knoll battle was in progress in the south) the 55th/53rd Battalion had relieved the 26th in the northern sector. By that time the whole of the Soraken Peninsula had been occupied. Across the low coastal strip ahead lay a wide area of swamp; further advance by the main body must eventually be astride a track which was hemmed in by this swamp on the west and the steeply-rising mountains on the east. There were still some Japanese troops in the foothills south of this bottleneck and the incoming battalion was given the task of destroying these and then advancing north to Pora Pora, a village in the defile mentioned above.

In carrying out the instruction to capture Pora Pora Brigadier Stevenson decided that a quick move through the swamps would probably divide the Japanese forces, whereas if he landed at Ratsua and drove inland he would tend to consolidate the enemy round Pora Pora. Consequently he ordered the engineers to develop a jeep road along the old Government Road and to bridge the Nagam River. This was a large undertaking as much of the road had to be corduroyed and the jungle cut back to let the sun in to dry it. Unfortunately the road had not been finished when the advance began.

The 55th/53rd (Lieut-Colonel Henry87), now forward in this sector, had not yet been engaged in full-scale action on Bougainville, though it had had six weeks of patrolling in the Numa Numa sector. It was so short of officers at this time that the battalion and the companies lacked seconds-in-command and, even so, five platoons were led by sergeants.