Chapter 10: Operations on New Britain

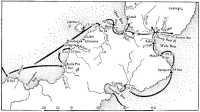

ON the island of New Britain in August 1944 there existed the same kind of tacit truce as on Bougainville and the New Guinea mainland. In each area American garrisons guarded their air bases, the main Japanese forces had been withdrawn to areas remote from the American ones, and, in the intervening no-man’s land, Allied patrols, mostly of Australian-led natives, waged a sporadic guerilla war against Japanese outposts and patrols.

In August 1944 one American regimental combat team was stationed in the Talasea–Cape Hoskins area on the north coast, one battalion group at Arawe on the south, and the remainder of the 40th Division, from which these groups were drawn, round Cape Gloucester at the western extremity. The main body of the Japanese army of New Britain – then believed to be about 38,000 strong (actually about 93,000) – was concentrated in the Gazelle Peninsula, but there were coastwatching stations farther west. In the middle area – about one-third of the island – field parties directed by the Allied Intelligence Bureau were moving about, collecting information, helping the natives and winning their support, and harassing the enemy either by direct attack or by calling down air strikes.

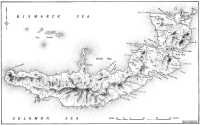

New Britain is some 320 miles in length and generally about 50 miles in width, with a mountain spine rising steeply to 8,000 feet. On the south the coastal strip is generally narrow, but suitable landing places are fairly frequent. On the north, east from Cape Hoskins, the coastal strip is wider but very swampy, the shore is mostly reef-bound and landing places are scarce. In addition several of the north-flowing rivers are wide and swift and infested with crocodiles. In the north-west monsoon season, from December to April, the north coast has heavy rain and high winds, while on the south coast it is generally hot and calm. The Gazelle Peninsula, where before the war some 37,000 out of the island’s 100,000 people had lived, is approximately 50 miles square and joined to the main part of the island by a neck only 21 miles wide. The largest plantations were within this peninsula, and at its north-eastern corner was Rabaul, for many years the administrative centre of the whole New Guinea territory, and now, in 1944, the main Japanese base in the South-West Pacific and headquarters of the Eighth Area Army of General Imamura.

When the relief of the 40th American Division by the 5th Australian was planned it was believed that the Japanese forces on the island included the 17th and 38th Divisions, small detachments of the 51st and 6th Divisions, the 65th Brigade, some 22,000 base and line of communication troops, and 2,500 naval men. Japanese air strength at Rabaul was believed to have been reduced to fewer than 30 aircraft and there were no ships in the area except an occasional visiting submarine. When the Australians

arrived it was estimated, however, that the Japanese possessed about 150 barges, including large craft able to carry from 10 to 15 tons or 90 men.

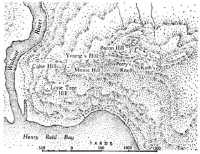

It was considered that the Japanese commander had established his main defensive line across the north-eastern corner of the Gazelle Peninsula, along the Warangoi and Keravat Rivers from Put Put on the east to Ataliklikun Bay on the west. (This was so.) Such a line would cover Rabaul and, round it, an area about 28 miles by 16. Forward of this position the enemy appeared to have established delaying forces of varying strength, notably at Waitavalo on Henry Reid Bay. Early in November, at the time when the headquarters of the 5th Division was moving to New Britain, a substantially revised estimate of the enemy’s strength and organisation was produced. The total strength was now believed to be not 38,000 but 35,000, the main field formations the 17th and 38th Divisions, each with three regiments, and the 39th Brigade;1 there were only 12 serviceable aircraft. In January the estimate of the total strength was reduced to 32,000.

Reports about the enemy’s food supply were conflicting, but it appeared that they had enough to keep men in fair condition and were growing vegetables on a large scale, and some rice. The principal sources of detailed information about the Japanese on New Britain were the AIB field parties mentioned above, and their agents. In April 1944 a change in the organisation of these field parties was decided upon. Thenceforward they would be concentrated in two groups, one on the north coast and the other on the south.

At this time the Japanese had posts at intervals along the south coast as far west as Awul near Cape Dampier. It was decided that the Australian southern guerilla force would be based at Lakiri, a village in the hills two days’ march inland from Waterfall Bay, and in an area into which the enemy had not ventured. It possessed a good site for dropping stores from the air and, as a preliminary, some 25,000 pounds of supplies were dropped there. To give added security to the base the Australian-led native guerillas, commanded at this stage by Captain R. I. Skinner, overcame the enemy’s coastwatching posts at Palmalmal and Baien, to the South-west and South-east, respectively, killing 23 and taking three prisoners. None survived at Palmalmal, but two escaped from Baien, and it was learnt later that they reached an enemy post at Milim bearing news of what had happened.

The south coast group was now placed under the command of Captain B. Fairfax-Ross, a former New Guinea planter, who had served as a subaltern in the 18th Brigade in the Middle East. Because of his New Guinea experience he had been transferred to field Intelligence work in August 1942 and had served behind the Japanese lines on the New Guinea mainland in 1943.

Fairfax-Ross’ orders were to clear the enemy from the south coast as far east as Henry Reid Bay, 150 miles from the enemy’s westernmost

New Britain

outpost at Montagu Bay; to contain him within the Gazelle Peninsula; to gather Intelligence; to succour Allied airmen who had been forced down; and help the natives and win or regain their confidence. This was a formidable task for a force comprising five officers (including Flight Lieutenant Hooper2 as second-in-command, and three platoon commanders, Lieutenants G. B. Black, J. McK. Hamilton and C. K. Johnson), 10 Australian NCOs, about 140 native troops, and such native allies as could be maintained on an air delivery of 5,000 pounds of supplies a month. At that stage no air support could be provided south of Cape Cormoran, but aircraft from the Solomons could be called upon to attack points to the north. At the remote base at Lakiri the native troops were trained to shoot and were given “basic field training in the terms of Infantry Section Leading”.

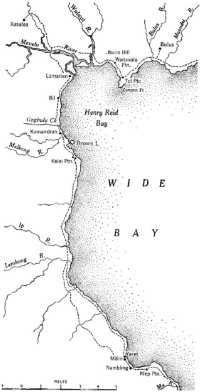

After the loss of Baien the Japanese reinforced their post at Milim at the south end of Wide Bay until it was 400 strong. Far to the west they retained posts at Massau and Awul and round Cape Beechey. Fairfax-Ross decided to move discreetly into the strongly-held Wide Bay area, advancing through the hills, concentrating first on winning over the natives, and using the air power available from Bougainville as his trump card. At the same time spies would be sent into the Gazelle Peninsula. In the western area also the first task was to gain information.

On 5th June an American patrol from the west led by Lieutenant White3 of Angau attacked the Awul garrison, which withdrew inland. Black and his platoon thereupon marched from Jacquinot Bay to Lau and Atu. In this area they found that native guerrillas about 80 strong had killed 14 Japanese and 14 of their native allies. At Awul they met White and his party. It now seemed that the Japanese from the Atu–Awul area were retreating to the north coast. Guerrillas were organised and at Kensina on 18th June, “after pretending to entertain a party of about 50 enemy”, the natives attacked and killed 28, losing 5 of their own men. Black’s patrol, in pursuit, found the remainder of the enemy about Rang and in an attack on 24th June killed nine, but had to withdraw after losing one native NCO As they moved north and east through hostile territory other Japanese were killed.

In the eastern section in this period Lieutenant Johnson was winning the support of influential natives in the mountains South-west of Wide Bay, where Captain C. D. Bates and Captain English4 now, like Johnson, due for relief, had also been organising native agents. On 24th June Bates, English, Johnson, who had been on the island since September 1943, and some of their natives were taken off by the destroyer Vendetta from

Cutarp, Johnson being replaced in Fairfax-Ross’ force by Lieutenant Sampson.5

The Japanese now became very active in the Wide Bay hinterland, punishing natives who had helped the Australians and collecting information, until wholesale reprisals against the Wide Bay people became a possibility. Fairfax-Ross set about persuading the people between Ril on Henry Reid Bay and Milim to move inland secretly to remote areas.

A heavy air attack was made on the main Milim positions on the night of 17th–18th July and as a result the Japanese withdrew some men to a new position away to the west and some men right back to Lemingi in the Gazelle Peninsula.

By early September the last of the Japanese stragglers on the south coast west of Wide Bay had been killed; the Japanese had heard many reports of a strong Australian base at Jacquinot Bay – reports circulated by the Australians to dissuade the enemy from advancing westward. This base, although non-existent as yet, was soon to become a reality, and from 5th to 7th September a reconnaissance party, including officers from New Guinea Force and the 5th Division, landed from the corvette Kiama and, guided by Black, examined the area.

Fairfax-Ross now planned to reconnoitre Milim with two platoons and, if circumstances were favourable, to attack. In support of this move the South Pacific Area’s air force was to bomb Milim on 8th, 9th and 10th

August and the sloop Swan to bombard it on the 11th. However, because Milim was 16 miles south of the boundary between the Solomons-based air force and the New Guinea-based one, a dispute arose, and whereas Fairfax-Ross had hoped for an attack by perhaps 100 aircraft on three consecutive days from the Solomons, all he got was “an attack by four Beauforts on August 12th which unfortunately missed the target”.6

The two-platoon force reached Milim unnoticed on 12th August, and found the enemy about 150 strong. At dawn they opened an attack in three groups, one to fire on the houses in the Japanese camp, another to fire from the flank, and the third to intercept any reinforcements from the Yaret position 500 yards to the north. Unfortunately a native fired his rifle during the approach, the enemy manned his defences, and, after a short exchange of fire, the attackers withdrew and placed ambushes across the tracks. The same day the Swan bombarded Milim. After three days of inaction on the part of the Japanese four native soldiers crawled into the enemy’s position and killed three, whereafter the Japanese fired into the bush at intervals for 36 hours. This fire ceased on the 18th and soon afterwards the position was found to be abandoned; there was much booty including boats and numerous machine-guns. It was discovered that the enemy had withdrawn to Waitavalo.

Fairfax-Ross now moved his forward base to the coast at the Mu River only 6 hours’ march from Waitavalo. On 17th and 18th September Fairfax-Ross, Sampson and a platoon, reconnoitring Kamandran, became involved in a fight with a Japanese force about 100 strong. Anticipating that the enemy would retaliate in force the Australians prepared defensive positions and one platoon under Sergeant-Major Josep, an outstanding NCO who had come from the New Guinea Constabulary, was placed on the hillside above Milim to give warning of an enemy advance. On the night of 28th September the Japanese did in fact advance on Milim and on towards the Australian defensive position at the Mu River. Here, however, largely because of Sergeant Ranken’s7 cool handling of his Bren gun, they were repulsed losing 17 killed. Next day about 200 Japanese reinforcements arrived and, in a fire fight with Josep’s men whose presence they had not discovered, 16 Japanese and a native ally were killed. The Australians now withdrew inland. Soon the Japanese about 700 strong were in their original positions round Milim, where they remained until heavy air attacks on 6th, 7th and 8th October forced them out again. By 10th October the guerilla force was again concentrated at Lakiri.

At this stage, since the landing of the 5th Division at Jacquinot Bay was soon to take place, Fairfax-Ross was instructed to cease guerilla warfare and concentrate on collecting and passing on information. He placed one platoon covering Jacquinot and Waterfall Bays, another

watching the coast from Rondahl Harbour to Cape Cormoran and sections covering the inland roads. On 4th November when troops of the 6th Brigade landed at Jacquinot Bay there were no Japanese on the coast south of Henry Reid Bay.

This we could view with a great deal of satisfaction as our labours, and the splendid work of our native troops and free natives associated with us, had now been well rewarded.8

Meanwhile a party of three native soldiers, of whom Lance-Corporal Robin was leader, had returned from a four months’ patrol into the Gazelle Peninsula as far as the enemy’s main defences on the Warangoi River. They had made contact with two devoted agents – Danny Marks William, a Seventh Day Adventist Mission teacher of Put Put, and Ah Ming,9 a Chinese of Sum Sum Plantation on the east coast – and brought back much information, including estimates of the strength of the garrisons in the outlying part of the eastern side of the peninsula: 200 at Kamandran, 500 at Waitavalo, 500 inland at Lemingi, 320 on the coast from Jammer Bay to Adler Bay, 125 at Sum Sum, 300 at Put Put. On 29th December knowledge of the Japanese dispositions was greatly augmented when Gundo, a former constable of Sattelberg, arrived. He had been in prison where he met Captain J. J. Murphy, captured at Awul in 1943, who told him of the presence of Australian groups on the island. Gundo, who had learnt some Japanese and had been employed as an interpreter, had in consequence a considerable knowledge of the enemy’s organisation, depots (excellent air targets), and deployment. He escaped and after many adventures arrived at the AIB base, bringing all this information with him.

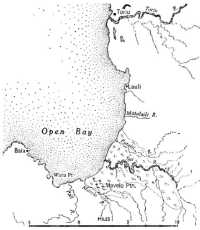

On the north coast in September 1944 Lieutenant G. R. Archer had led a guerrilla patrol deep into the Gazelle Peninsula. It was out for several weeks and penetrated into Seragi Plantation, near the western tip of the peninsula. On 10th September Archer attacked a Japanese party and put it to flight, killing three and capturing some equipment.

In this month Captain Robinson, a veteran guerilla leader and an experienced New Guinea hand, whose work on Bougainville in mid-1945 has already been mentioned, had on the north coast a force of native troops with three officers and 15 other Australians, mostly senior NCOs. Five Europeans and 20 natives were posted in the hills south of Baia. In October the Japanese sent a party forward to Baia and in November became still more active. Shots were exchanged on the beach in Hixon Bay. The enemy (who were also using native troops) moved on and on the night of 13th November tried to cross the Pandi River.

There can be no doubt that the enemy suffered heavy casualties (Robinson reported) as the following morning the canoes or what remained of them were found on the beach completely shot to pieces, quantities of blood were seen in the vicinity – undoubtedly wounded and dead had been removed during the night.

On 19th November, however, the Japanese pressed on in force. More than 100 crossed the Pandi south of its mouth in flat-bottomed boats, and

about the same time native scouts arrived to report that 50 Japanese were moving along the beach towards the mouth of the river. The Japanese scattered the defenders at the crossing and moved west. One Australian-New Guinea patrol fired on this party as it was resting and hit many.

Robinson now decided to withdraw all his parties to Ea Ea (Nantambu), leaving only 10 native scouts forward. On 20th November Lieutenant Seton reported that 70 Japanese had tried to cross the Pandi at a point some miles inland, but the current prevented them. Seton’s patrols engaged these. Fearing that the Japanese might get behind him on an inland track Robinson moved his force to his rear base a few miles South-west of Langeia leaving a forward post at Ulamona. This party withdrew on 21st November when some hundreds of Japanese began to converge on Ulamona from three points. When the Japanese settled in at Ulamona, Robinson withdrew his force, including 400 loyal natives who had evacuated their villages, to the western side of the Balima River near Cape Koas.

Building on the foundations laid by earlier AIB parties in 1942, 1943 and early 1944 the guerilla force had achieved remarkable results in gaining information, winning the support of the natives, and driving the enemy’s outposts out of about one-quarter of the island. In the whole operation only two New Guinea soldiers were killed.10

The visit of the reconnaissance party to Jacquinot Bay in September was an outcome of a conference between Generals Savige and Ramsay at New Guinea Force headquarters on 24th August, when it was decided to examine both the Jacquinot Bay and Talasea–Hoskins areas and report on their suitability as bases to accommodate a division. Thus from the outset it was intended to establish the incoming force well forward of the existing main bases. The Jacquinot Bay party had decided that the area could house a suitable base: there was shelter for up to six Liberty ships and a site for an airstrip. A second party, examining Talasea and Hoskins, found that both the Talasea and Hoskins sites were less accommodating. On 15th September General Blamey approved the establishment of the new base at Jacquinot Bay and the movement of the 6th Brigade there, less one battalion which was to go to Talasea–Hoskins’.11 Later in September Savige formally instructed Ramsay that the role of his division was to relieve the American forces on New Britain and protect the western part of that island.

Major-General Ramsay, the commander of the incoming division, was a schoolmaster by profession who had served in the ranks of the artillery

in France from 1916 to 1918, had been commissioned in 1919, and was commanding the artillery of the 4th Division when war broke out. He had controlled the artillery of the 9th Division at El Alamein, and commanded the 5th Division in operations on the New Guinea coast earlier in 1944. His leading brigade had not yet been in action as a brigade although one battalion – the 36th – had fought at Gona and Sanananda in the Papuan campaign, and later had taken as reinforcements some men from three battalions which were disbanded after hard fighting in Papua. The brigade commander and the commanding officers, however, were soldiers of wide experience. Sandover, the brigadier since May 1943, had served with the 2/11th Battalion in North Africa and Greece and commanded it on Crete; he was the youngest infantry brigadier in the Australian Army. Caldwell12 of the 14th/32nd Battalion had proved himself an able company commander in North Africa and Greece; Miell13 of the 19th had served with the 6th Cavalry in the Middle East; 0. C. Isaachsen of the 36th had led a company of the 2/27th in Syria and had now been commanding the 36th for more than two years. The 14th/32nd was a Victorian battalion, the 36th a New South Wales one, and each had largely retained its territorial character. The 19th, originally a New South Wales machine-gun battalion, had absorbed the Darwin Battalion when serving in the Northern Territory and a proportion of its officers were former NCOs of the regular army. The 6th Brigade had been in New Guinea since July 1943 training, doing garrison duties and unloading ships; in the opinion of its commander, nine-tenths of the men were anxious lest the war should end before they had heard a shot fired in action.

The landing of one battalion (the experienced 36th was chosen) with its ancillary detachments, 19 in all, at Cape Hoskins, an area already developed by the American forces, seemed to present no difficulties. The first flight of the group landed at Cape Hoskins on 8th October from the transport Swartenhondt after a voyage which Colonel Isaachsen considered had demonstrated defective liaison between the army and navy.

The quarters for troops were found to be in a filthy condition and it was necessary to put a large working party from the battalion on to cleaning it up (he reported). ... The naval authorities at Finschhafen ordered [the Captain] to sail to Talasea and provided him with charts for that place only. The charts were not even as good as the ones provided in the army terrain studies with the result that the ship nearly ran on to a reef. On arrival at Talasea the Captain was at length persuaded that he should go to Hoskins [using] the chart in the terrain study.

At Hoskins an American battalion gave all the help they could in unloading and fostering the incoming unit. The Australians found that the American battalion was occupying a perimeter with double-apron barbed wire fences, pill-boxes and weapon-pits, but that practically no storage huts were available. For several weeks the 36th Battalion was under the command of the 185th American Regiment and “was receiving orders

from that regiment, 6 Brigade, and 5 Division, but fortunately these orders did not conflict much”.

At Jacquinot Bay, although the AIB patrols continued to report that the area was clear of the enemy, it was decided to provide against the possibility of a sudden attack on the incoming force by providing a naval escort and by landing ready for action; in any event it would be a useful exercise. Thus the two transports carrying the first contingent – the 14th/32nd Battalion group and a company of the 1st New Guinea Infantry Battalion – arrived at Jacquinot Bay on 4th November escorted by the destroyer Vendetta, frigate Barcoo and sloop Swan.14 The landing was uneventful. Brigadier Sandover considered it fortunate that it was not opposed.

First Army orders naturally made provision for possible opposition (he wrote), but the landing craft arrived late, the RAAF’s “maximum air effort” consisted of one Beaufort which arrived well after H-hour. The troopship was guided to its anchorage by the BM in a native canoe. High spot of the trip was the annoyance of base officers who, after watching from armchairs on the wharf the heavily-laden troops disembarking, brought their armchairs out by DUKW and expected the working parties to carry the chairs up with the weapons, ammunition and fighting stores as deck cargo. The chairs were sent back ownerless to the wharf. Incidentally, they were branded ACF [Australian Comforts’ Fund]. ... However, we have nearly reached the war; up to the present the Bde has acquitted itself very creditably. Both of these give cause for gratitude.

After having stood by for two days to cover the landing HMASs Swan, Vendetta and Barcoo steamed east and bombarded Japanese positions in Wide Bay. After their departure two naval launches MLs 802 and 827 remained in the area available to the 5th Division for intercommunication and patrolling against Japanese barges. In the early stages landing craft were provided by Americans of a company of the 594th Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment; the 41st Australian Landing Craft Company did not arrive until 15th February, and then with only 18 Australian craft, less rugged and powerful than comparable American craft. General Ramsay took over responsibility for New Britain on 27th November. General Sturdee, who had assumed command of all New Guinea operations on 2nd October, had instructed him that, as information about the enemy on New Britain was conflicting and incomplete, it would be unwise to undertake major offensive operations until more information was available. “To undertake such operations would be to court heavy casualties, which the AMF could not afford.” Consequently Ramsay should undertake patrols and minor raids “to obtain the required information, to maintain the offensive spirit in our troops, to harass the enemy and retain moral superiority over him”. In particular the tasks of the division were to defend the bases; “so far as the maintenance situation would

permit with existing resources, to limit Japanese movement South-west from Gazelle Peninsula”; and to collect information on which future plans could be based.

These fairly modest tasks did not differ greatly from those that had been allotted to the handful of white officers and the few native troops of the AIB, who had managed to perform them partly as a result of their skill and enterprise and partly because the Japanese seemed willing to confine themselves to the Gazelle Peninsula, with outposts and occasional patrols in the area immediately to the west.

The AIB on 10th November had given the incoming commander a comprehensive assessment of the temper and tactics of the Japanese on New Britain. It appeared to take the enemy about ten days to make plans and assemble troops in response to a display of force. Recently they had not advanced south of Waitavalo with fewer than 200 troops and equipped with a high proportion of mortars, evidently considering that the best way to deal with guerilla troops was to mortar them. They generally advanced along the tracks and could be ambushed. They showed little tendency to exploit. If a strong Japanese patrol came upon an abandoned AIB camp it would return to the Waitavalo base and there report fictitious successes.

Two days after the arrival of the 36th Battalion at Cape Hoskins on 8th October Colonel Isaachsen sent a patrol along the coast by barge to examine Ulamona, Ubili and Ea Ea and make contact with Captain Robinson’s party. It returned next day having seen no Japanese and reported that Ea Ea would provide a suitable flying-boat base and excellent barge harbour in the north-west monsoon season (December to April). Enemy patrols were moving, however, between the Sai and Mavelo Rivers and west of the Mavelo, evidently pressing on towards Robinson. In November Isaachsen with Captain W. A. Money, an officer of the AIB who had been a schooner master on this coast before the war, and a lieutenant of the American 594th EBSR travelled by barge to Ea Ea examining every harbour on the way. They found that Ea Ea was the only place east of Talasea that provided suitable barge landing points and shelter for large freighters. Thereupon Sandover strongly recommended that if any advance along the coast was to be made it should begin immediately so as to avoid the rough weather of the north-west season due soon to open. Ramsay who, by agreement with the American commander, had now taken over responsibility for the operations on the north coast, informed Sandover that no eastward move was intended yet and he was to confine patrolling to the area west of the Yamule River.

In the first half of November, however, as mentioned earlier, enemy activity south of Open Bay increased and Robinson reported that Japanese patrols had returned to the Pandi River, that strong enemy parties were between Ea Ea and Baia, and a submarine had been seen off Ea Ea. When, on 22nd November, the Japanese reached Ulamona, threatening Robinson’s base, the limit of the 36th Battalion’s patrolling was immediately extended to the Balima River so that it could give help, and a company

was moved to Bialla Plantation on 23rd November and, to Robinson’s great relief, began patrolling forward. On 6th December another company was moved to Bialla and the two patrolled along the coast and inland along the Balima. On the night of 1st January one of Robinson’s patrols fired on a submarine between Cape Koas and Gulagula. Next day another patrol found that, under this new pressure, the Japanese had withdrawn and the area Ea Ea–Pandi River–Matatoga–Ulamona was clear of the enemy.

Because of this sudden withdrawal and because of the difficulty of beaching barges at Bialla, General Ramsay decided to allow the 36th to advance to Ea Ea, which was the nearest sheltered beach to Bialla, and was covered to the east by the Pandi River and five miles of swamp. Isaachsen was to leave a small detachment at Hoskins to defend the strip and help refuel reconnaissance aircraft;15 at Ea Ea he was to prevent the enemy filtering west from the peninsula but was to avoid a heavy engagement. Thus on 13th January a company of the 36th landed at Ea Ea and a company of the 1st New Guinea on Lolobau Island, both unopposed. By the end of January the 36th, except for the Hoskins’ detachment, but including “D” Company of the 1st New Guinea Battalion (Captain Bernard16), was at Ea Ea.

Meanwhile, on the south coast, the remainder of the 6th Brigade was complete at Cutarp by 16th December; there a battery of the 2/14th Field Regiment (Lieut-Colonel R. B. Hone) joined it on 1st January. The brigade’s role was to prevent the enemy filtering west from Wide Bay, while the 13th Brigade protected Jacquinot Bay against an enemy approach from north or south.

On the South-west Sandover had under command the 12th Field Company (Major Nelson17) less a platoon which was on the north coast. “Work in the initial stages was hampered by poor equipment, but with the assistance of unit pioneer platoons much was accomplished. The poor tracks in the Jacquinot Bay area made heavy demands on engineers, and at one time the only possible method of transporting stores was the inauguration of a tractor train with six jeep-trailers being towed by a tractor.”18

On 27th and 28th December Lieut-Colonel Caldwell with two companies of the 14th/32nd Battalion and a platoon of Captain H. McM. Lyon’s company of the 1st New Guinea Battalion were landed at Sampun. The advance-guard of the force was now approaching the Japanese concentration at the north end of Henry Reid Bay, yet the Japanese, lacking air reconnaissance, not very enterprising in patrolling, and closely watched by the AIB parties, were evidently still unaware of its presence in New

Britain.19 On 7th January Ramsay instructed Sandover to concentrate the whole of the 14th/32nd, with a troop of the 2/14th Field Regiment, at Sampun, and on the 21st to establish a new base at Milim (which had been regularly visited by patrols of the 1st New Guinea Battalion), to secure crossings over the Ip River, and “patrol toward Henry Reid Bay without becoming heavily committed”. Sandover was warned on 23rd January that he should soon move the remainder of the brigade to the Kiep–Milim area. This advance was begun on 26th January and completed by 11th February.

Meanwhile, on the north coast, patrols had probed forward from the new base at Ea Ea but met no enemy troops until 27th January when a platoon of native soldiers fired on and put to flight a patrol of Japanese and native troops near Mavelo Plantation. Two days later from 20 to 30 Japanese attacked a section outpost of the 36th Battalion near Baia and it withdrew. A series of small clashes followed culminating in a sharp fight between a large enemy party on the one hand and two New Guinea platoons and one platoon of the 36th on the other. Casualties were inflicted on the Japanese but the New Guinea troops were somewhat unnerved by mortar fire and the detachment withdrew in stages to Baia.

When a company of the 36th moved forward again the Japanese withdrew before they were attacked, but on 9th February two platoons (one Australian and one New Guinea) met an enemy party north of the Mavelo River and withdrew after inflicting casualties. In view of the strength of the enemy patrols it was decided to use patrols one company strong. One such patrol, attempting to cross the Sai River, was attacked by 70 to 80 Japanese, who were repulsed. A second company crossed the Sai farther inland, and circled round to the coast putting to flight a Japanese party there. Isaachsen was then ordered first to withdraw east of the

Operations in Central New Britain, October 1944–March 1945

Pali River and then to occupy the line of the Mavelo River. There at dawn on 8th March some 100 Japanese supported by a field gun attacked the leading platoon but were repulsed.

On 3rd March Ramsay had instructed Isaachsen not to establish patrol bases forward of the Mavelo River but to send mobile patrols forward to the Sai River. On 30th March a company landed by barge north of the Sai, met seven Japanese on the Potaiti River and killed or wounded them all. Heavy rain during the first fortnight of April confined patrolling to the area south of the Sai. AIB patrols ahead of the 36th reported that the Japanese were busily building defences in the Matalaili River area; it was evident that his strong patrols from January to March were intended to delay the Australian advance until these were ready. Aircraft attacked the Japanese positions and on 17th March the sloop Swan bombarded them. On 7th April AIB patrols found the defences abandoned and it seemed that the Japanese had withdrawn to the Toriu River. It was decided that their experiences in Wide Bay, described below, had persuaded them that it was unwise to commit their force in small, isolated parties. At the end of April the main body of the 36th was at Watu Point, one company at the mouth of the Mavelo, one company at Ea Ea with a platoon detached at Hoskins. Between the main Australian position at Watu and the main enemy outpost on the Toriu lay a wide area of swamp. Ramsay decided that the battalion group could not safely hold at Lauli and he lacked the means of maintaining any larger force on the north coast.

In December 1944 No. 79 Wing RAAF – No. 2, No. 18 (NEI) and No. 120 (NEI) Squadrons – was ordered to Jacquinot Bay when the airfield was ready. Its advanced party arrived on 23rd February, but in May, before the wing had been concentrated there, it was ordered

north in response to a request by the Netherlands Indies Government that their few squadrons be used over Dutch territory. Later, occasional air attacks and supply-dropping missions were carried out by No. 6 Squadron from Dobodura. In February a detachment of No. 5 Squadron was established at Cape Hoskins for army cooperation.

In comparison with operations elsewhere in the Pacific the air and naval support allotted to the Australian forces throughout New Guinea and the Solomons in 1945 was scanty, but nowhere was it so diminutive as in New Britain. Since the supporting aircraft were based on the mainland of New Guinea requests for air action had to be made 24 hours before it was needed, and the briefing of crews had to be done by signal until early in March when the completion of the Jacquinot Bay airstrip made it possible for them to land there for briefing. From January until March the tactical-reconnaissance aircraft were based at Hoskins where again they had to be briefed by signal, and there were never enough aircraft to do the work required by the forward units. When, in March, these aircraft were based at Jacquinot Bay briefing improved. Also a system of ground to air communications was evolved so that the crews could be briefed in the air. Up to the end of April – that is, during the whole period of offensive operations – no light intercommunication aircraft were available, although they were urgently needed to provide a link with the troops on the north coast, to carry officers forward from divisional headquarters to the 6th Brigade, to enable observation of artillery fire, and to evacuate wounded. The only means of moving from Jacquinot Bay to Hoskins was to make a five-day march across the island or a six-day voyage by barge around it clockwise, and the latter was practically impossible because of the shortage of barges. It took up to three weeks to send a written message from Jacquinot Bay to the north coast.

In Wide Bay the AIB patrols had reported that the enemy’s main position was on high ground 800 yards South-west of Kamandran Mission. By 2nd February the 14th/32nd Battalion was firmly established on the Ip River with a troop of artillery two miles southward. By the 6th a company was deployed 3,000 yards north of the river and some 5,000 yards from Kamandran, and soon afterwards patrols had reached Kalai Plantation, which stretched along the coast for two miles southward of Kamandran Mission. Early on 11th February occurred the first clash on this coast between the Japanese and troops of the 5th Division when a small patrol fired on five Japanese. In the meantime a jeep road had been pushed forward to within 3,000 yards of Kalai Plantation.

The steady advance continued. A platoon of Lyon’s company of the New Guinea Battalion moved round the left flank and observed enemy parties moving from Kamandran towards Ril; the 14th/32nd was deployed 600 yards south of Kalai with the supporting 28th Battery at the south end of the plantation. On 15th February the New Guinea company set up ambush positions and at 3.15 p.m. about 60 Japanese walked into one of them. The native troops held their fire until the Japanese were very close, then blazed at them killing 20 Japanese and two of their native

allies. The ambush party then withdrew, being still outnumbered. That day an AIB patrol reported some 200 Japanese dispersed from the creek bounding the Kamandran area northward for two miles. However, after an attack by Beauforts and some artillery fire the 14th/32nd advanced and found Kamandran abandoned. Sandover established his headquarters and the 19th Battalion on the northern edge of the plantation. Captured papers suggested that there had been an enemy platoon at Kamandran and that there were from 400 to 500 Japanese south of the Mevelo River. The Australians continued to probe forward and by the end of February the 19th Battalion, which had relieved the 14th/32nd at Gogbulu Creek, had secured crossings over the Mevelo River and was patrolling east to the Wulwut (Henry Reid) River, beyond which lay Waitavalo, a ridge overlooking the Waitavalo and Tol Plantations at the eastern end of Henry Reid Bay – the scene, three years before, of the massacre of some 150 Australians endeavouring to escape from Rabaul. Two naval launches patrolled the coast to intercept enemy barges and fired on targets ashore. On one occasion a 3-inch mortar and crew were carried by a launch and bombed targets on Zungen Point, the eastern point of the bay. Almost every night the 2/14th Field Regiment from Kalai Plantation fired across the bay on targets at Waitavalo.

The advancing force was now only about 20 miles from the 36th Battalion on the northern coast of the isthmus, but between them lay a tract of country so rugged that repeated attempts to find a suitable direct track had not yet succeeded.

On 27th February General Sturdee instructed General Ramsay that he was to secure the Waitavalo–Tol area and hold a line not forward of Moondei River–Waitavalo Plantation–Lauli, except that ground necessary for the defence of Tol Plantation could be held. He could send forward of this line such patrols as were necessary to give warning of an enemy attack. This gave the 6th Brigade a somewhat more definite task and led to a long series of fights that was to open on 5th March and last for about six weeks.

In consequence of this order Ramsay, on 3rd March, redefined the role of the 6th Brigade which would now involve crossing the Wulwut River and capturing an elaborate system of Japanese defences along an east-west ridge about 2,500 yards in length and rising steeply from the river and the sea to about 600 feet.

Heavy engineer tasks were involved. Temporary crossings of the Mevelo and Wulwut Rivers had to be made, the jeep track had to be extended behind the advancing infantry, beach-heads improved, and the infantry helped with mine clearings and demolitions. The supporting engineer company was now the 4th Field Company, Major Nelson who had commanded the 12th Field Company remaining to command the incoming one.

The assault was opened on 5th March by the 19th Battalion, commanded since 28th February by Major Maitland.20 The first effort to cross

the river failed because of heavy fire, but at the end of the day one company under Major A. A. Armstrong, with an artillery officer of the 2/14th Regiment, Lieutenant Crompton,21 was on the east side. In the meantime a company of the 14th/32nd which had relieved the 19th on the Mevelo was fired on by an invisible group of Japanese, evidently trying to cut the tracks behind the attacking force, and lost 2 killed and 3 wounded. On 6th March after artillery fire on Cake Hill Captain Stainlay’s22 company attacked up the steep slope. The leading platoon was pinned down but the others moved left and right and with their support the leading platoon attacked again, and by 10.30 a.m. the Japanese were withdrawing south to Lone Tree Hill leaving 9 killed. One Australian was killed and four wounded. At the end of the day two companies were concentrated on Cake. From Cake onwards the direction of artillery fire was extremely difficult as the observation officers were working in dense rain forest, the fall of shot was rarely visible, and the guns had often to be registered by sound. On the other hand the narrow tracks had all been registered by the many Japanese mortars in the Waitavalo fortress area. The main role of the guns was now to silence these mortars – a difficult task as it soon became evident that they were sheltered in caves where artillery fire became dangerous.

It was difficult for the engineers to maintain communications with the forward infantry. After rain the Wulwut River became a swift torrent; the night after it was bridged a flood came down, the bridge and a ferry boat were swept out to sea, and the forward companies were cut off. The first beach beyond the Wulwut was hard to land craft on and was under mortar fire.

On 7th March after a bombardment (which incidentally removed the lone tree from Lone Tree Hill) Captain Behm’s23 company occupied it without opposition. It now seemed that the Japanese had withdrawn their main force eastward to the higher part of the ridge, because, on the 9th, Major Armstrong’s company took Moose Hill with little opposition, and

early next morning took Young’s Hill (named after Lieutenant Young,24 commanding the leading platoon, who was wounded but remained on duty). About 400 yards to the east stood another knoll the same height as Young’s and connected to it by a saddle. About 10.45 the company advanced towards it but after 200 yards came under heavy fire and was halted on the narrow saddle. Soon two platoons were stationary in a narrow perimeter and the third (Lieutenant Perry25) was out of touch on the right. The company continued to advance, unobserved, and soon was in the rear of the enemy on Perry’s Knoll. Thence it attacked, took the position, and established contact with the rest of the company. Thirteen Japanese dead were counted; the Australians lost two killed and 10 wounded of whom four, including Armstrong, remained on duty. Lieutenant Hunter26 and a small group made a reconnaissance to the east but were fired on, Hunter and another being wounded. The Japanese suffered still heavier loss when they made a disastrous charge against the company on Perry’s at 7.20 p.m. They came under fire from machine-guns on Young’s; the men on Perry’s held their fire until the enemy was only a few yards away; the attack wilted, and afterwards 25 dead were counted.

Armstrong’s company, however, had now been hard hit and next day, when its casualties had mounted to 23, it was withdrawn and Behm’s company was concentrated on Perry’s and Captain Kath’s27 on Young’s. (One company of the 19th was tied down to the task of securing Cake Hill and the northern flank.) In an effort to silence the mortars which were bringing down a galling fire the 2/14th Field Regiment sent 460 rounds over, searching an area 400 yards in depth, and eventually silenced the mortars, although only for the day. On 12th March heavy mortars (the Japanese had improvised mortars to fire 150-mm shells) rained 60 bombs on Perry’s and Young’s, killing four28 and wounding nine, including Lieutenant Faul,29 and temporarily disabling 12 others with bomb blast. It was a day of torrential rain which reduced visibility to a few yards.

On the 13th the artillery again succeeded in silencing the mortars and the five Beauforts made an accurate strike on the main enemy positions. A tunnel was found in the side of a spur (Kath’s Hill) running north-east from Perry’s. Captain Kath and Lieutenant Worthington30 were both fatally wounded when Worthington threw a phosphorous grenade into the tunnel and it blew back when the grenade exploded. The Beauforts, mistaking the resultant smoke for a target indicator, strafed the area, but fortunately without hitting anyone.

By this time the surviving Japanese were all concentrated on Bacon Hill. Sandover decided to relieve the 19th Battalion with the 14th/32nd for the final assault. By 15th March the relief was complete and Captain Sinclair’s31 company of the new battalion was on Kath’s and Captain Jack’s32 on Perry’s.

Next day two Japanese aircraft appeared and dropped two 100-lb and ten 20-lb bombs round a bridge that had now been built over the Wulwut, killing one and wounding four of the 19th Battalion.33 About 10 a.m. the forward companies – now Captain Bain’s34 and Jack’s – attacked. Jack’s company was checked by heavy fire and later in the afternoon Colonel Caldwell ordered that it be extricated. Bain’s probed deeply to the northeast and in the afternoon dug in north of Bacon Hill. Bain was wounded and Lieutenant Pugh35 took command. That day 10 Australians were killed and 13 wounded.

The enemy were now almost surrounded in an area about 500 yards by 500. Caldwell placed Jack in command of both forward companies for an attack on the 17th, to be made from the north, supported by artillery fire directed by Captain Adamson36 and Lieutenant Longworth37 of the 2/14th Regiment. Jack’s men thrust south and South-east until they were established to the east of Bacon Hill. Then two platoons began clambering westward up the hill about 40 yards apart. Soon they were being heavily grenaded, and the Japanese mortars were dropping bombs round Jack’s headquarters just to the rear. A third platoon was sent in on the left to give fire support. Then the men of the forward platoons went in throwing grenades and firing and by 4 p.m. had taken the hill except for two positions. Thirty Japanese broke off and fled. In the day the attacking battalion lost 6 killed and 17 wounded, a number of these being hit carrying wounded men through mortar fire.

On 18th March the mortar fire was intensified from the few remaining enemy positions, and it seemed that the Japanese were firing off their ammunition while they could. The attack was resumed. When Corporal Martin’s38 section was halted on the steep spur by fire from three posts he jumped up shouting, “They can’t do that to me”, and went on alone, firing

his Owen and throwing grenades. He forced the enemy out of all three posts, killing five, before he himself was hit. The decisive attack was launched through this foothold. By 3 p.m. all the Japanese had been cleared from Bacon Hill; and a patrol from Kath’s, under Lieutenant Lamshed,39 penetrated to a knoll 800 yards to the east and found no enemy there. No Japanese now remained in the Waitavalo–Tol area. In the five days from the 16th to the 20th 4 officers and 53 others had been killed or wounded. In the next few days fighting patrols probed deeply but few stragglers were found. The 19th relieved the 14th/32nd on 21st March and exploited to the Bulus and Moondei Rivers.

On 28th March General Ramsay ordered that the 13th Brigade should relieve the 6th, and by 12th April this change was complete. Because of the withdrawal of part of the 41st Landing Craft Company and the concentration of the company of the 594th EBSR preparatory to its departure, the intended relief of the 36th Battalion on the north coast by the 37th/52nd, ordered at this time, was not completed until 19th May, nearly two months after the decision was made.

The division had now achieved its main task; it was firmly established across the neck of the Gazelle Peninsula. Henceforward it was to hold this line and patrol forward of it, but not to thrust farther forward in strength.

On the south coast the division had lost 38 killed and 109 wounded, on the north 4 killed and 13 wounded. The killing of 138 Japanese on the south coast and 68 on the north had been confirmed. Five prisoners had been taken. Strict discipline had kept illness to a remarkably low level: the 6th Brigade, although fighting under difficult conditions, had only 41 malaria casualties.

Four months of patrolling by the infantry and maintenance and routine work by other troops followed the capture of the Waitavalo area. The 13th Brigade (Brigadier McKenzie40), now forward on the south coast, was a West Australian formation which had not hitherto been in action. Its battalions were all commanded by officers who had come from AIF battalions: Lieut-Colonel W. S. Melville led the 11th, Lieut-Colonel Horley41 the 16th, and Lieut-Colonel Brennan42 the 28th. Its first deep patrol was an eventful one.

On 11th April a platoon of the 16th Battalion under Lieutenant Knight,43 with Captain Murdoch44 as an observer, was sent out to reconnoitre a suitable barge-point at Jammer Bay and report recent enemy movement; information suggested that only about twenty Japanese were there. The

patrol spent the night of the 12th–13th at a point about one mile from Jammer Bay. Next morning security patrols reported all clear, and the platoon began to form a hidden base from which it intended to send a party forward to the bay. Suddenly, about 7.30 a.m., it was attacked by Japanese who had crept to within 80 yards, and soon advanced, firing, to within 15 yards of the patrol’s perimeter. Then the enemy began using mortars from about 100 yards away. The patrol fought the enemy off but not before three Australians had been killed, one mortally wounded, and 13 slightly wounded; one was missing. The wireless set had been out of commission since the 11th. It was decided to withdraw, and in the next half-hour the seriously wounded man was carried out, and the sections thinned out and finally broke contact and withdrew. All the Australians concerned had been in action for the first time, but had behaved calmly, and handled their weapons skilfully, and a dangerous situation was saved.

As a result of patrolling, capture of documents, and information from natives, it was decided that there were now at least 100 Japanese round Jammer Bay and they were digging strong defences: indeed that the occupation of Jammer Bay would probably require an operation on the scale of the one that had been carried out at Tol.

Soon after the capture of Tol Lieut-Colonel B. G. Dawson, commander of the New Guinea Battalion, walked across the island from Ril to Open Bay, thus establishing ground contact between the two parts of the division. (Dawson had made this walk when escaping from Rabaul after the Japanese invasion in 1942.)

In May the 37th/52nd Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Embrey45) of the 4th Brigade marched across the island by this route and relieved the 36th which had then been forward on the north coast for about eight arduous months, and the 36th marched across to the south coast. These journeys took five days and a chain of staging camps was set up along the route. Also in May Brigadier McKenzie of the 13th Brigade was invalided to Australia and replaced by Brigadier Winning.46 McKenzie had commanded this brigade since May 1940 – a longer period in command than that of any other Australian infantry brigadier in 1939-45. In June the 2/2nd Commando Squadron arrived at Tol and was concentrated at Lamarien.

In May the airfield at Jacquinot Bay was completed and the New Zealand Air Task Force began moving in. No. 20 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force, began patrolling over the Rabaul area on 29th May. No. 21 Squadron also served at Jacquinot Bay from May until July when it was replaced by No. 19. These were fighter squadrons. One New Zealand bomber squadron was also maintained at Jacquinot Bay from June onwards.

From May onwards most of the deep patrolling was again done by the two companies of the 1st New Guinea Battalion. There were occasional clashes, often with small groups of two or three Japanese sent out to

harass the Australians, but the main Japanese outposts were now east of the line beyond which the division was forbidden to advance in force.

The employment of native troops was producing a variety of disciplinary problems. The Australians were collecting a mass of valuable information from natives, but there was evidence that the Japanese too were receiving information by “bush wireless” which circulated at “an alarming rate”. Officers were enjoined, in orders distributed in May, to impress on the native soldiers that when they met civilian natives who spoke their tongue “ol tok bilong armi i tambu”. There had been a tendency for natives to circulate disparaging remarks about Australian units with which native sub-units had fought; these could harm European status within the Pacific Islands Regiment and were also forbidden. There were other problems of discipline, which at first glance seemed less serious:

In some cases (said a battalion routine order of 5th May) it has been noticed that when being addressed by European or native NCOs soldiers of this battalion have failed to cease smoking and/or remove cigarettes from their mouths. Another irregularity is wearing of cigarettes between the head and ears. These unsoldierly practices will in future be regarded as an offence.

In June the 1st New Guinea Battalion, now temporarily commanded by Major A. R. Tolmer in Lieut-Colonel Dawson’s absence at a school, was concentrated on New Britain, “A” Company arriving from Bougainville, “C” from Madang. The two newly-arrived companies began a period of training. The men of the Bougainville company had done invaluable work but had been in operations for seven months with little rest and were tired and debilitated; every man in two platoons that were examined had hookworm. They seemed restless and discontented. The Europeans in the company, as mentioned earlier, were over-tired and their numbers depleted.

On 14th June two New Guinea soldiers were arrested and were about to be charged with having refused to carry out a lawful command when about 50 men of the company marched towards the detention compound armed with rifles and sticks. When ordered by a native NCO to take their rifles to their quarters they did so, but returned to the compound armed with sticks and stones, wrecked it and freed the two prisoners. An inquiry revealed that on Bougainville the native soldiers of the company had agreed that they would free any member who was put in detention; detention was “fashion belong before” and did not now apply to them as fighting soldiers. In the next two days two senior native NCOs were threatened by privates, and there was talk of a coming fight between the mainland natives and the New Britain ones. One native told his European sergeant that the time had come for “fighting soldiers” to get European rations.

Tolmer in his report on these incidents concluded that the native soldiers were becoming more educated, and were discontented because of differences between their treatment and the treatment of Europeans; and that natural leaders – sometimes good leaders in action – were arising who were encouraging discontent. Tolmer sought authority to discharge 15 soldiers, all patas (privates). Their periods of service ranged from 13 to 26 months.

On 14th July there was another disturbance in the company from Bougainville which culminated in the release of three prisoners from the unit detention compound. On Brigadier Winning’s orders the extreme step was taken of disarming the company and marching it to Jacquinot Bay where a court of inquiry was held. On 19th July there was a disturbance in the company from Madang. Finally the offenders were tried according to civil regulations and six were sentenced to 12 months’ and eight to one month’s imprisonment.

In a report on this incident Major Tolmer wrote:

In this type of non-progressive warfare the native soldier is becoming increasingly dissatisfied. The strategy in this area, which has several times been explained to them, is still beyond their comprehension. Our patrols on many occasions contact the enemy, sometimes suffering casualties, and pinpoint his positions with no “follow up” action on the part of the Australian troops. The native soldier’s reaction to this is: “Is it worth while?”

The mainland natives ... dislike being on New Britain, but are most anxious to return to their own country and fight the Japanese who still occupy much of their land.47

These tensions, occurring as they did among troops who were giving invaluable service and saving many Australian lives and who were to be allotted a more important role should the war continue into the summer, were very disturbing, particularly to the keen young officers who had formed these battalions. Colonel Dawson of the 1st New Guinea Battalion attributed the troubles to faulty employment of the New Guinea troops by all commanders on Bougainville and New Britain to whom they had been allotted, with the exception of Brigadier Sandover.

When he returned to his command on 8th August, Dawson wrote in his monthly report that the reason for the indiscipline was laxity on the part of the Europeans, and that in its turn was a result of a war establishment which provided so few Europeans that they were overworked. Another reason, he considered, was the splitting up of companies when in operations into small groups under the command of officers who were ignorant of natives and their tactical role.

After the war Dawson, who had been in action first with an AIF infantry battalion, then an Independent Company, and then New Guinea troops, expanded this criticism and propounded doctrines about the employment of New Guinea troops whose soundness seems to have been demonstrated in every area in which they fought, from 1942 to 1945.

You will readily appreciate (he wrote) from reports of AIB activities, how effective native units can be in deep patrolling, and in driving in enemy outposts. At no stage was 1st NGIB given the opportunity to operate in this, its true cavalry role. Instead, it was fragmented, and the fragments placed under command of all sorts of Australian infantry officers, very few of whom had the slightest idea of the tactical role in which native troops should be employed. In effect, they were often used so that Australian infantry sub-units, by disposing the natives round their perimeter, could sleep soundly at nights. To get an appreciation of just how absurd this is, one only has to imagine that an infantry platoon commander in the

desert might ask for a tank, or an AFV of some sort, to be placed under his command and to operate with the platoon to provide local protection. I wonder how many cavalry regiment commanders would have stood for that?

I had no alternative, however, as until the other units of the Pacific Islands Regiment were raised and trained, the 1st NGIB had to be scattered under several different commands. Not until the war ended did I get the battalion back under my own disciplinary control. It was during this period of fragmentation, and close fraternisation with Australian infantry, away from my personal control, and frequently the control of their experienced company commanders, that a decline took place in the respect in which Europeans were held, and the idea grew that the native soldier should be entitled to expect similar treatment to Australian infantry. ... Several native platoons had experienced occasions in action when green Australian infantry had not shown up particularly well. ... These occurrences were the subject of much unfavourable comment by the natives. Quite apart from the abandonment of their correct tactical role, native units should never under any circumstances be fragmented and integrated with infantry troops inexperienced in their handling and control. Neither should they be used in a purely infantry role.

[The New Guinea soldier] should remain at all times under the command of those who know him and understand him (he added) and not be farmed out like a library book. Senior commanders should be told not to yield to the temptation to break the unit down under the command of inexperienced infantry junior officers. They should never operate as sub-units in cooperation with other infantry, but should be given their own unit tasks to perform, as a unit, in their correct cavalry role. At no time should senior officers interfere in the internal administration and discipline of native battalions.

Such problems were not confined to New Britain and Bougainville. On 6th August General Sturdee telegraphed from First Army headquarters to the Chief of the General Staff, General Northcott, that serious unrest existed among natives of the Pacific Islands Regiment and the native labourers, particularly at Lae, because of dissatisfaction with their low rates of pay. A spokesman of the regiment had said that the native troops wanted £3 a month instead of the present rate of 10 shillings a month for a private. Angau officers took a very serious view of the unrest. Sturdee himself considered the pay not commensurate with the important work the troops were doing in action.

PIR are natural experts in jungle warfare (he signalled) and few Australians ever reach their individual standards. This all fully realised by native soldiers who feel that their pay of 4d per day and no compensations or pensions most unfair.

Sturdee said that he realised that to pay £3 to New Guinea privates might upset the economy of New Guinea after the war; and recommended £1 a month for a first-year and second-year private, £1 5s for a third-year private; £1 15s for a corporal; £2 10s for a sergeant; and £4 for a warrant-officer. He added that wireless announcements that the Minister for Territories, Mr E. J. Ward, had promised 15 shillings a month as a basic wage for labourers had caused unrest and he, Sturdee, proposed to increase the labourers’ wage to 15 shillings. However, he had no power to increase the soldiers’ pay.

General Blamey, when he saw this signal, urged that increases in pay be approved immediately. “In view of the serious and important part designed to be played by native troops in releasing white troops early any mass action or mutiny during the next few months would be disastrous.”

Events moved quickly and on 9th August Blamey was informed that the Secretaries of the Treasury, the Army, and External Territories had agreed to increased rates and were seeking Ministerial approval. This approval arrived within a week of Sturdee’s proposal. Soon, however, the main problem was not pay but demobilisation and rehabilitation.

As a result of this unrest the pay for native privates was increased from 10 to 15 shillings a month after one year’s service and to £1 a month after two years’ service, the increases being made retrospective for up to six months. Shorts, shirts and European pattern badges of rank were issued to New Guinea soldiers. At the same time discipline was made tighter and compliments more strictly demanded.

Meanwhile, on 15th June 1945, after ten weeks of relatively uneventful patrolling, General Sturdee instructed Major-General Robertson, who had replaced Major-General Ramsay48 in command of the 5th Division in April, that in order that his units might be more actively employed and thereby their morale and fighting efficiency maintained, they might undertake “minor offensive operations against enemy parties” within the limits of the division’s own resources. When General Blamey saw this instruction he objected that it might “easily involve demand for further resources which cannot be met”, and instructed that any operations under the new instruction were to be undertaken only with the approval of Sturdee, who must inform Blamey of any such proposals.

In June and July the headquarters staff of the 5th Division, which had served in New Guinea for 32 months, was relieved by that of the 11th Division, of which Major-General K. W. Eather (from the 25th Brigade) took command on 4th August. General Robertson had gone to Wewak a few days earlier to command the 6th Division. Soon, here as elsewhere, it was known that the end of the fighting was near.

On New Britain as in other forward areas the arrival of news that negotiations for a Japanese surrender were in progress was a signal for great revelry: to describe it is to describe what happened in many other places.

In the Jacquinot Bay area the darkness was broken by coloured flares fired from ships in port; machine-guns rattled; tracers streaked up into the heavens. There was singing and shouting and long blasts from motor horns. ... In the hospital wards sisters and orderlies sang with the patients. By now several fires were visible as merry-makers ignited some disused buildings in old camp sites. This joyous scene continued until almost morning.49

On 15th August when the news arrived that the war was over it was received quietly. Native workers and troops were assembled and told the news – “Japan man ‘e cry enough” – and native runners were sent into the hills to spread the news among the villages.

Next day Gracie Fields and a party of other entertainers arrived at Jacquinot Bay from Bougainville and in the evening performed before 10,000 troops.

Highlight of the night ... was a half hour’s non-stop entertainment by “Gracie” who at the conclusion of the concert said: “I hope it won’t be long before you all pack oop and go HTM – home to Moom.” Ten thousand troops had exactly identical hopes and the thunderous cheering showed this in no uncertain manner.50

On 4th August the acting commanding officer of the 2/14th Field Regiment, Major Rylah,51 had asked that the regiment, being the only remaining complete unit of the 8th Division, should be included in the Australian token force which, the Government had announced, was to assist the British in the re-occupation of Singapore. Rylah pointed out that the regiment, formed in December 1940, had served at Darwin from July 1941 to January 1943, and on the New Guinea mainland from late 1943 until December 1944, but up to that time had fired only 25 rounds against the enemy. It had served on New Britain since December 1944. “One of the factors that has sustained the pride and esprit de corps of the regiment is the remembrance of the fate of the rest of 8 Div and the desire to do the utmost to avenge and release them has ever been present.” The Singapore force, however, was not formed on the scale intended.

It was learnt after the war that the Japanese, in November 1944, suspecting a landing in the Wide Bay area, had sent a force of two infantry companies, a machine-gun company, and a mortar platoon to reinforce the outpost at Tol. In January the main body of this force was round Waitavalo, with a platoon at Kalai Plantation and observation posts along the Wulwut River. The Kalai outpost estimated that a battalion of Australians attacked it and forced it to retreat on 9th February. The Australian force which advanced to the Wulwut River was estimated at two battalions and eight field guns.

On the north coast Lieut-General Yasushi Sakai of the 17th Japanese Division, in the period from May to September 1944, had small forces aggregating 530 men. The largest was a depleted battalion of the 54th Regiment at the Toriu and Pondo. There were smaller groups at Massava Bay, Yalom, and Cape Lambert.

After the war a senior officer on General Imamura’s staff said that, up to the middle of 1944, they believed that the Allies, having isolated Rabaul, would attack it, probably employing more than ten divisions, including about six Australian divisions. But after mid-1944 when the Allied advance began to head for the Philippines and Japan, they felt that the Allies would advance only gradually overland towards Rabaul and attack it at a time when the advance towards Japan had been halted, or when it had

succeeded, or when the Australian forces had been reorganised and reinforced.52

When the Japanese staffs became aware that the Australian force at Open Bay was a small one they decided that the operations in New Britain were a diversion intended to mislead them into believing that important operations were being undertaken, whereas in fact the main body of the Australian Army was going to the Philippines. (American forces had recently landed on Leyte.) Imamura decided that two could play at this game and set about trying to attract Australian reinforcements into this area. Four barges landed 200 men near Ulamona, but, when it was found that the Australian force was even smaller than had been believed, after several clashes the Japanese force was withdrawn by sea to Toriu whence it had come.

There were some Japanese staff officers who found more subtle reasons for the Australian landings: either they were a result of the unwillingness of the Australian Commander-in-Chief to allow his troops to fill a comparatively minor role under American command in the Philippines; or they were part of a political move to enable Australia to claim her mandates after the war.53 These speculations, of course, contained more than a germ of truth.

From October onwards the Japanese based on the Toriu patrolled between the Sai River and Ea Ea. An outpost watched the landing at Baia of what seemed to be a battalion, and, from Baia, of the advance by sea of a company to Mavelo Plantation.

The Japanese force in the Waitavalo–Tol area numbered 400 to 450 at the outset. Before the final engagement 150 of these had been killed, about half by artillery and mortar fire.

The account of the Japanese side of the action at Waitavalo and Tol, compiled after interrogations in Rabaul after the war, says: “The Australian forces advanced under cover of their bombardment and by clever infiltration captured our water point at our main line of defence. ... This made it very difficult for our forces to put up a final stand. ... On 12th March the garrison commander made his decision to fight to the last man. Reinforcements were not sent from Rabaul because our main line ... was along the Warangoi and Keravat Rivers [and] could not be disturbed. In any case reinforcements would have had to be sent in barges subject to attack from the air. At this time the commander of the 38th Division sent a message of encouragement to the Tol commander who then attempted a last rally. All men, including those of headquarters units, went out to the [Wulwut] River, and it is assumed that the unit was completely annihilated by 18th March.” The force round Tol was out of communication from 15th March onwards.

The staff officer of the Eighth Area Army quoted earlier remarked on the Australian policy of establishing offensive bases at points along the

roads and advancing step by step, developing the roads as they went so that they would carry motor vehicles. Australian scouts were skilful in concealment, acted promptly and “made puppets of natives skilfully”. “The Australian tactics were very steady and the Australian men were very persevering.”

After the war the staff of the Eighth Area Army at Rabaul said that it had estimated the strength of the whole Australian Army at about seventeen divisions – nearly three times the actual 1945 strength. They were not sure whether the headquarters of the First Army were at Lae or Finschhafen. The only Australian commanders whose names they knew were Generals Blamey and Sturdee. Indeed, here as on Bougainville, the Australians reached the conclusion that Japanese Intelligence work was of a very low order.

It would appear that the Japanese were anxious to obtain information, as their higher formations carried an extensive Intelligence organisation, but they failed badly because they did not realise that Intelligence of value is obtained by carefully piecing together scraps of information supplied by lower formations and especially by forward troops.54

When the fighting ended the main Japanese formations, as before, were concentrated north of the Warangoi–Keravat line. Forward of this line there were, on the east, 1,100 troops in the Put Put–Lemingi–Adler Bay–Jammer Bay area; and, on the west, 520 at posts between Pondo and the Matalaili River.

As mentioned above, by January 1945 the total strength of the Japanese forces on New Britain had been estimated at 32,000 including about 2,500 naval men. By June the estimate was 50,000 plus, perhaps, an additional 10,000 to 15,000 naval men. These figures were still too low, a result (as on Bougainville) largely of failure to obtain adequate information about the naval forces or the large numbers of base troops and civilian workers. In August 1945, the naval troops in the Gazelle Peninsula numbered 16,200 and there were 53,200 soldiers. In addition there were nearly 20,000 civilian workers attached to the army or navy. Close by on New Ireland were 11,100 troops of both Services and 1,200 civilian workers. The grand total of Japanese on New Britain and New Ireland in August 1945 was 101,700.55 Of these 3,600 were in hospital, not a large total in the circumstances. In this force were 19 generals, 11 admirals, 3,300 other officers of the army and 1,400 of the navy. (In view of the sharp and persistent criticism of the Australian Army by Ministers and others on the ground that it had too many generals, it is interesting to note that, at this time, there were 26 generals in the whole of the Australian Army in Australia and the South-West Pacific Area.)

The strengths of the main Japanese Army formations on New Britain in August were: 17th Division, 11,429; 38th Division, 13,108;

39th Brigade, 5,073; 65th Brigade, 2,729; 14th Regiment, 2,444; 34th Regiment, 1,879; 35th Regiment, 1,967. The five independent brigades or regiments contained 19 battalions. Since the naval fighting units amounted to a force of divisional strength, the equivalent of five somewhat depleted divisions was round Rabaul.

Thus the achievements of the 5th Division and the AIB parties on New Britain were remarkable. On the one hand was a Japanese army of over 53,000, most of them in veteran fighting formations, and over 16,000 naval men. On the other was a division of relatively raw troops, although commanded down to unit level by widely-experienced officers. Employing only one brigade in severe fighting, General Ramsay had secured (and General Robertson maintained) a grasp on the central part of New Britain, already virtually cleared of the enemy by the AIB parties, had captured the enemy’s forward stronghold round Waitavalo, and had established an ascendancy over the Japanese so complete that they offered no great resistance to fairly deep patrols in the last four months of the war. This was done at a cost of 53 killed, 21 who died of other causes, and 140 wounded.56

The air support and the shipping allotted to the Australian force were far from adequate. The responsibility for this rested with General MacArthur and General Blamey. GHQ were not responsible for the fact that the Australians had engaged in more active operations than the Americans, but, even so, they allotted to the Australian forces fewer ships and small craft than their own static garrisons had possessed. From time to time Blamey pressed for more shipping and with some success. It seems, however, that the few transport and light aircraft that were so urgently needed could have been provided with little difficulty by the schools in Australia, the civil airlines, or the big Australian air force farther north, whose crews during part of this time were becoming rebellious because they considered that they were being employed on insignificant tasks.

Why General Imamura at Rabaul showed so little aggressive spirit compared with General Hyakutake of the XVII Army on Bougainville or General Hatazo Adachi of the XVIII Army at Wewak remains a puzzle. Both the XVII and the XVIII Armies delivered resolute counter-offensives against the American forces, accepting appalling losses, and, when the Australians began attacking them, they defended every position with all the strength they could find. This was despite the fact that most of the formations composing each army had suffered crushing losses and hardships in earlier campaigns, and by mid-1944 the men were under-nourished and many were sick. The divisions and regiments round Rabaul, on the other

hand, had endured less arduous fighting in earlier operations and were fit and well fed. Yet, after the American landings late in 1943, they used only relatively small forces in the main part of New Britain. They allowed guerillas to thrust most of their outpost forces back into the Gazelle Peninsula. The key position at Tol was defended by a force of about battalion strength which the divisional commander exhorted to fight to the last but did not reinforce. In the final stages Imamura had only about 1,600 troops deployed forward of the fortress area, within which he held experienced fighting formations equivalent to five divisions.