Chapter 16: Planning for Borneo – April to June 1945

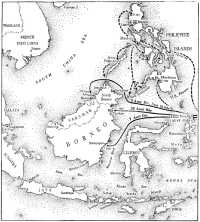

IN an earlier chapter the story of the higher planning of the operations against Borneo was carried as far as mid-April, when, despite General Marshall’s opinion in February that such operations would have little immediate effect on the war against Japan, he and his colleagues of the Combined Chiefs of Staff had approved them and the dates had been finally fixed. One object was to secure a base for the British Pacific Fleet, and, incidentally, the operation would provide employment for the I Australian Corps. The British Chiefs of Staff, however, considered that to develop Brunei Bay in northern Borneo as a fleet base would be a waste of resources; and the Australian Commander-in-Chief, although he had expressed approval of the seizure of Tarakan Island and Brunei Bay, had made it clear that he did not favour the third and largest operation in Borneo – the attack by the 7th Division on Balikpapan.

On 1st May the Borneo campaign had opened with the landing of the 26th Australian Brigade Group at Tarakan. The second phase – the seizure of Brunei Bay by the remainder of the 9th Division – was due to begin on 10th June.

For every Allied nation but one the surrender of the German forces on 7th May signalled a great reduction of effort. Australia, however, unless plans were changed, would not diminish but rapidly intensify her efforts in the next few weeks until, from 1st July onwards, every field formation in her army would be in action. As it was, virtually all her navy and the greater part of her air force were serving in the Pacific.

For many months the Australian Government had been giving much attention to post-war problems. The prospect that its manpower would be so heavily committed in the final phase was disturbing, and now that the war in Europe had ended it seemed fair that Australia’s contribution should be reduced. As mentioned, General Blamey on 16th May had suggested to the Government that the 7th Division should perhaps not be committed to the proposed attack on Balikpapan, and the Australian force employed in Borneo should be limited to the 9th Division.

On Blamey’s advice the acting Prime Minister, Mr Chifley, wrote to General MacArthur on 18th May that, with the end of the war in Europe, his Government had been considering what adjustments could be made in the strength of the Australian forces in order to relieve the manpower stringencies and at the same time maintain a fighting effort of appropriate strength. The Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Army had pointed out that if there was to be a substantial reduction in the strength of that army the 7th Division should not be committed to operations on the Borneo mainland.

I shall be glad (Chifley added) if you can give urgent consideration to this matter in relation to the present stage of your plans for the Borneo campaign, and furnish

me with your observations. I would add that it is the desire of the Government that Australian Forces should continue to be associated with your command in the forward movement against Japan, but the Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces advises that, if a reduction in our strength is to be made, the 7th Division should not be employed for further operations until the overall plan is known.

General MacArthur replied on 20th May:

The Borneo campaign ... has been ordered by the Joint Chiefs of Staff who are charged by the Combined Chiefs of Staff with the responsibility for strategy in the Pacific. I am responsible for execution of their directives employing such troops as have been made available to me by the Governments participating in the Allied Agreement. Pursuant to the directive of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and under authority vested in me ... I have ordered the 7th Division to proceed to a forward concentration area and, on a specific date, to execute one phase of the Borneo Campaign. Australian authorities have been kept fully advised of my operational plans. The concentration is in progress and it is not now possible to substitute another division and execute the operation as scheduled. The attack will be made as projected unless the Australian Government withdraws the 7th Division from assignment to the South-West Pacific Area. I am loath to believe that your Government contemplates such action at this time when the preliminary phases of the operation have been initiated and when withdrawal would disorganise completely not only the immediate campaign but also the strategic plan of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. If the Australian Government, however, does contemplate action along this line, I request that I be informed immediately in order that I may be able to make the necessary representations to Washington and London. ... There are no specific plans so far as I know for employment of Australian troops after the Borneo Campaign. Operations in the Pacific are now under intense consideration in Washington and London. I do not know whether Australian troops are contemplated for use to the north. Consideration is being given by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to a proposal to turn over to Great Britain full responsibility for that part of the South-West Pacific Area which lies south of the Philippines. In that event undoubtedly all Australian formations would come under British Command for operations to the south.

At this distance it seems that, in his determination to squash the Australian proposal, MacArthur somewhat overstated his argument. It is not clear in what way the abandonment of the Balikpapan operation would have seriously disorganised either the local Borneo operation or “the strategic plan of the Joint Chiefs of Staff”. The securing of oilfields would be achieved by the operations at Tarakan and in British Borneo. The Japanese garrison at Balikpapan had no offensive power beyond the narrow limits of the ground they occupied round a ruined refinery and a virtually-abandoned seaport. To the end, however, the Australian Government in its relations with MacArthur took the view that it was theirs not to reason why. On the day on which MacArthur’s telegram arrived Chifley replied that the Government had no hesitation in agreeing to the use of the 7th Australian Division as planned. The Government fully accepted MacArthur’s views, which agreed with “the Government’s conception of its commitments and by which it absolutely intends to abide”.

Before this decision had been reached the Government had been considering two allied problems affecting the future of the army and demanding prompt decision: what should be the size of the force which Australia would maintain in the next phase, and what principles should govern the discharge of men with long service in the army?

On 19th April Blamey had sent the Minister for the Army a detailed submission about the conditions under which men were being discharged from the army. He pointed out that it was mainly the older men who were going out, yet it had been strongly represented that men with five years of service should have the right to elect to be discharged. On 1st

March there were 12,392 of these and by the end of 1945 there would be about 40,000. He recommended that, say, one-third of future “releases to industry” should be allocated by the army and consist of

(a) men who had completed five years’ service;

(b) men over 35 who had completed four years’ service including two years overseas;

(c) medically “B” class personnel with disabilities which made their satisfactory employment difficult;

(d) others who applied on grounds of personal hardship.

He recommended also that the balance of the releases should be effected on recommendations from the Manpower Directorate but should be confined to “personnel with five years’ service, personnel over 35 with three years’ service, personnel over 45 and personnel who were medically ‘B’ class”.

In short, whereas hitherto the main considerations had been the needs of industry and the retention of young men in the army, a main consideration should now be the future welfare of the long-service men and women. These had earned the right to be looked upon as human individuals and not merely as units of manpower.1 The army’s plan, if adopted, would presumably not have interfered with the army’s efficiency; it recognised the needs of industry for men with required qualifications; from the veteran soldier’s point of view the main thing was that a plan should be adopted promptly. It was then 19th April.

No decision had been made, however, when, on 30th May, Blamey sent to the acting Minister, Senator Fraser, some facts and figures about releases of men from the army which, he hoped, the Minister would make known to the War Cabinet and Parliament “in order to stifle what I consider unjustified criticism and to place the Army’s ready cooperation in re-establishing the national economy in its true light”. He reported that, between October 1943 and April 1945, 122,802 men and women had been discharged or released, 78,000 through normal releases and 44,000 to meet special manpower demands. In the same period 21,443 were received into the army compared with the War Cabinet allocation of 26,960. The army had been responsible for the control and maintenance of 20,000 Italian prisoners sent to rural employment. In the period the reduction in army organisations had approximated 25 per cent.

On 31st May, however, the War Cabinet decided that “all members of the Army and Air Force with operational service overseas and who have over five years’ war service are to be given the option of taking their discharge”. On 14th June Senator Fraser asked General Northcott to make a submission to the War Cabinet showing, among other things, how many men with five years’ service who were now in operational areas could be released immediately. This suggested a drastic solution to a problem to which, two months before, Blamey had proposed a balanced one. As shown above, the number of men in the fighting formations with over five years’ service was not very large but it was rapidly increasing and included a large proportion of the leaders, senior and junior. Northcott and later Blamey telegraphed to Fraser to point out that a large number of key men would be affected by such a decision and that the formations

then in action, or embarked, or soon to embark, could not afford to lose all their long-service men. The formations most affected would be the 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions. Blamey suggested that the present announcement about releases should be limited to the release of “men who enlisted in 1939 as and when the present operations permit”.

The effect of the Government’s proposal if rigidly applied would have been to have left the army very gravely short of leaders by the end of the year, since by that time all who enlisted in the AIF up to the end of 1940 would have gone.2 Blamey’s compromise would enable commanders to retain key men and would have confined the discharges largely to the 6th Division, which contained most of those who had enlisted in 1939 and, having been in action since 1944, could better afford to spare its veterans than could the 7th and 9th which were just about to embark on large-scale operations after a long period of retraining.

Possibly the Government did not intend its proposal to include officers, but, if so, it did not indicate this either in the original inquiry or in a teleprinter message which Senator Fraser sent to General Northcott on 16th June. In the course of it he said:

My own view of the position is that full immediate effect should be given to the Government’s decision to allow soldiers with previous operational service now serving in operational units or immediately due to serve in such operational units the option of taking their discharge. Desire that pending Government decision immediate instructions be issued that no troops who come within the Government’s decision shall leave Australia for operational service.

This was a somewhat different proposal to the earlier one in that release was now to be optional. Northcott telegraphed this message to Blamey saying that he had been unable to contact Fraser to explain the impracticability of the proposals, and that he had taken no action to carry it out. Fraser continued to press that his instruction be issued. Northcott continued to insist that he could not do so.

On 18th June Northcott attended a meeting of the War Cabinet and explained the difficulties. The general effect, he said, would be to release officers, NCOs and specialists who by reason of length of service, training and experience had risen to positions of leadership or become key personnel. It would be impossible to begin to carry out the War Cabinet’s decision until appreciable relief from present operational commitments had been obtained. The army was committed to operations to a greater extent than at any previous period.

Thereupon the War Cabinet recorded that there had been “no promise to release men with operational experience immediately on the attainment of five years’ war service without regard to the organisation of units and the effect on operational plans”, and directed the Defence Committee to

submit a revised definition of operational service overseas with statistics to indicate its effect.

Next day (19th June) Chifley made a measured statement in Parliament in the course of which he said that the releases would be made in a graduated manner but at least 50,000 men would be released before the end of the year. This left the problem where it had been two months before when the army had made its proposals of 19th April. Finally on 28th June the War Cabinet decided that “subject to operational requirements, the option of discharge is to be given in the first place to personnel attaining five years’ service, who, in the case of Army personnel and Air Force ground staff, have two years’ or more operational service overseas, and, in the case of aircrew, have more than one tour of flying operations against the enemy”. In this decision two other groups whom the army itself considered to deserve special consideration – “B class” men who might find it difficult to obtain employment, and others who applied on grounds of personal hardship – were left out. The Ministers had no means of knowing that it was already too late for their belated decision to substantially accelerate the release of the veterans.

To give soldiers with five years’ service the choice of obtaining a discharge or remaining in the army created many personal problems, particularly among officers. Many of these felt a duty to stay with their units until the end and had misgivings about applying for discharge. On the other hand they did not wish to have to say to their wives and children that they had refused to return home, and they had also their post-war careers to consider.

Meanwhile, on 5th June 1945 the War Cabinet had decided the size of the forces which should be maintained in the later stages of the war: the navy should remain at its present strength, the operational forces of the army should be reduced to three divisions, and the air force reduced proportionately to the army. Together the army and air force were to release 50,000 men by December. This decision was communicated to Mr Bruce (the Australian High Commissioner) in London, to Mr Forde and Dr Evatt at the United Nations Conference at San Francisco, who were asked to seek the agreement of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, and to General MacArthur, who was asked, among other things, that the 7th and 9th Divisions should be replaced by other troops as soon as his plans would allow.

The Australian Ministers suggested to the Combined Chiefs that the three divisions should be employed thus:

one brigade group in the Solomon Islands,

one brigade group in New Guinea,

one division in New Britain,

one division in operations against Japan,

probably one brigade group in South-east Asia.3

The Government also expressed the opinion that, if a new command was set up in the South-West Pacific, Australia should be given operational control of Australian forces in all Australian territories – a change which would merely give formal recognition to a situation which had existed since the last quarter of 1944.

One outcome of these Australian proposals was that the British Joint Planners now recommended that Borneo, Java and Celebes should be included in Admiral Mountbatten’s command and that Australia should control operations elsewhere in the area. On 7th June, at the suggestion of the Americans, the boundaries were again redefined so as to remove all the Netherlands Indies from American command but retain American command in the Admiralty Islands, the eastern Solomons, Ocean and Nauru Islands.

While these proposals were still the subject of lengthy cabled discussion between Melbourne, Washington and London, Blamey instructed his staff to make plans for: one expeditionary force (probably for Japan) of one division, a second expeditionary force (probably for Malaya) of a brigade group including a tank regiment and the 1st Parachute Battalion, and a New Guinea Force including two divisions less a brigade group.

As mentioned, one reason for anxiety about manpower had long been the needs of the British Pacific Fleet. In September 1944 the British Government had informed the Australian Government that it planned to put into the Australian area by July 1945 120,000 seamen, including 29,000 ashore. The civilian labour force required by the Pacific Fleet would be 4,890 by the middle of 1945. On 7th June 1945 General Blamey received a copy of a Defence Committee minute about the works to be undertaken for this fleet. It showed that Australia was committed to spending over £25,000,000, including £1,943,000 on building or extending air stations for the Fleet Air Arm. Blamey at once wrote to Sir Frederick Shedden: “I must admit on reading it I feel very much like Bret Harte’s gentleman who exclaimed: ‘Am I blind? Do I see? Is there visions about?’4 ... Is it realised that tremendous airfields have been laid down at Moresby; there are seven of them, one or two in excellent repair. At Nadzab there are several in excellent repair and in use. Good strips have been laid down at Buna and Dobodura, all of which are 2,000 miles nearer the war at least than some of those proposed. ... May I urge that before a decision is reached on what appears to me to be a completely absurd demand ... a complete examination of existing facilities somewhere near the war area should be made.” To Northcott he wrote: “I hope you will fight this very vigorously. It looks to me the method of conducting war in drawing rooms and hotel lounges.” On 2nd July

Blamey’s suggestion about the use of airfields in New Guinea was incorporated in a telegram to the Dominions Office.

When complaining about what he considered the extravagance of the requirements of the British Pacific Fleet Blamey may well have had in mind protests which he and other army leaders had been making in the previous two years about the lavish scale of the demands made by the American forces and their effect on the Australian manpower problem. As early as 3rd May 1943 Colonel Kemsley,5 the Business Adviser to the Minister for the Army, wrote to the Minister that many of the demands being made by the American forces for stores, equipment and buildings seemed extravagant “to a degree far beyond any Australian or British standards”. At the same time it was impossible to discover what Australia’s total commitments would be for maintenance of American forces. He suggested the appointment of an additional Cabinet Minister with the task of conducting negotiations with the American representatives and the appointment to MacArthur’s staff of a Major-general whose approval must be obtained before any demands for purchases or construction were made. Nothing came of this.

A somewhat similar note was struck on 4th November 1944 when General Blamey wrote to Mr Curtin as Minister for Defence to point out that the American forces were building up in Australia vast reserves of food.

Many millions of square feet of storage space are in use including wool stores and warehouses hired from industry and new buildings erected under Reverse Lend-Lease. Requests made for release of these for urgent Australian requirements, both Army and civilian, bring advice of inability to empty them because of lack of shipping to move the stores housed therein.

Blamey directed attention to a cable recently received from Washington describing American plans for bringing American industry back to normal as soon as possible after the war with Germany ended, and how to this end the American Government was already cancelling wartime contracts and reducing depot stocks. Yet, Blamey added,

the impression is growing that stocks are being built up under Reciprocal Lease-Lend, far in excess of legitimate operational requirements, with the object of making them available in the Philippines, China or America itself, for civilian or relief purposes, thus buying favourable publicity for American interests, both Government and private, at the expense of our sadly strained and depleted Australian resources.

Blamey suggested that Australia “should immediately revise and very considerably limit Reciprocal Lease-Lend administration and commitments”.

It was on top of such American demands for goods, storage space and manpower that the requirements of the British Pacific Fleet were piled. On 7th March 1945 the Quartermaster-General, Major-General Cannan,6

wrote to the Chief of the General Staff pointing out that, despite a decision by the War Cabinet that services given to American forces under reciprocal Lend-Lease would have to be reduced if Australia was to meet commitments for the British Pacific Fleet, there had been reluctance to curb American demands. Cannan went on to say in effect that, because excessive quantities of supplies were occupying storage space in Australia and New Guinea, Australia was faced with the necessity of spending labour and materials on building storehouses for the British Pacific Fleet.7

On 4th April Cannan returned to the problem. He wrote Blamey a long minute in which he referred to “the avoidable waste of manpower and materials that went on without question [for Reciprocal Lend-Lease] and the lavishness and extravagance which characterised US demands whilst Australian Army and Australian Services’ demands were being subjected to rigid scrutiny and economies”. He instanced three camps built for American troops at a total cost of £560,000 and never occupied; the Cairns port project, abandoned after £650,000 had been spent; an air depot at Darwin which cost £600,000 and proved unnecessary. Australia was spending about one-quarter of her war budget on services for the Allies. “Within the wide ambit of that service much could be done to effect real and justifiable economies.” Throughout the war, however, the Australian Ministers showed a strong disinclination to take any action that might be looked on with disfavour by the American political and Army leaders, and the soldiers’ complaints were ineffective.

The approach of the operations in British Borneo had brought forward the problem of restoring the civil administration in a British colony. Hitherto Australian troops had operated either in Australian colonial territory, with Angau officers to care for the civilians, or in Dutch Borneo, with officers of the Netherlands Indies Civil Affairs unit (NICA) performing a similar task. For about two years, however, there had been discussions between Australian and United Kingdom authorities concerning both the general doctrines of military government being developed in London and the specific problems of Borneo.

In July 1943 the Full Cabinet, on the recommendation of the Minister for External Territories, Senator Fraser, had established a departmental committee to plan the rehabilitation of the Australian territories. G. W. Paton,8 professor of law at Melbourne University, was appointed its chairman, and it was to contain representatives of the Departments of External Territories, Post-War Reconstruction, External Affairs, Army and the Treasury. In the second half of 1943 Paton and Major N. Penglase, of Angau, a former district officer in New Guinea, were sent abroad to study British and American doctrines of military government of occupied

or re-occupied territories. They visited the American School of Military Government at Charlottesville, the United States Naval School of Military Government and Administration at Columbia University, and did the course at the War Office Civil Affairs Staff Centre in England; they had discussions with a variety of authorities including the Foreign, Dominions, Colonial and War Offices in London.9

Since April 1942, however, there had existed at LHQ a research branch, initially attached to the Adjutant-General’s branch, later to the Directorate of Military Intelligence, but since 6th October 1943 established as a directorate responsible directly to General Blamey (as were the Military Secretary, the Judge-Advocate-General and the Directorate of Public Relations). Its head was Lieut-Colonel Conlon, who had joined the former research branch at the outset.

In the five months after the establishment of the Directorate of Research, and while Paton and Penglase were either abroad or preparing their report, the directorate added to its staff a number of senior lawyers, anthropologists and economists. These included (in the order of their arrival) : Major W. E. H. Stanner, an anthropologist, who had been commanding the North Australia Observer Unit; Professor Stone,10 of the chair of international law and jurisprudence at Sydney; Professor Isles,11 of the chair of economics at Adelaide; Dr Hogbin12 and the Honourable Camilla Wedgwood,13 both anthropologists; Colonel Murray,14 a former militia battalion commander who in civil life was a professor of agriculture.15 Those who were recruited direct from civil life came in with the rank of temporary Lieut-colonel.

By February 1944 the functions of the Directorate of Research had been re-defined thus:

(1) To keep the Commander-in-Chief and certain other officers informed on current events affecting their work;

(2) To undertake specific inquiries requested by Principal Staff Officers;

(3) To assist other Government Departments in work concerning the Army.

On 20th October 1943 the Directorate was given specific duties concerned with the National Security (Emergency Control) Regulations. It is required to maintain full records at LHQ of all exercise of powers and all activities by the Army under

the Regulations; to effect liaison and collaborate with Federal and State authorities on matters arising out of activities by the Army under the Regulations; and to carry out such other duties in connection with the Regulations as the C-in-C may direct....

A considerable proportion of the work of the Directorate has been concerned with administration and development in New Guinea.16

On 23rd December 1943 Lieut-Colonel Stanner had been specifically appointed “Assistant Director of Research (Territories Administration)”.

Thus, in between the time of Professor Paton’s appointment as chairman of the departmental committee, on which the Department of the Army was to be represented, and the presentation of his report on his and Penglase’s studies abroad, a second organisation had been developed to advise the Commander-in-Chief (not the Ministers) on “civil affairs including Territories Administration”. The first committee was a departmental one and thus the Army Secretariat would have had influence with it, or at least knowledge of the advice it offered. The Directorate of Research, however, was responsible directly to the Commander-in-Chief and had no direct link with the Secretariat.

This was the situation in January 1944 when Paton submitted a report describing the British doctrines of Civil Affairs and the governmental machinery so far developed, and placing before the Government the problems that, he considered, had to be faced in New Guinea. He proposed that a Civil Affairs Directorate should be established at LHQ to work in cooperation with the Department of External Territories, and that a school should be set up to train additional staff for Angau. He recommended that the Director of Civil Affairs should be a person with experience of native administration and that at least some of his staff should have served in peace in the Civil Service in the territories. A War Cabinet agendum along these lines was drafted.

When the Paton proposals reached LHQ, Blamey, evidently on Conlon’s advice, objected that he should have been consulted before the proposal went to the Cabinet, which had been

placed in the position of giving decisions on questions upon the immediate implications of which it had but little information and which obviously were not understood by those who prepared the agenda.

Blamey added that the territories would continue to be the main overseas base of operations for a considerable time and, as long as this continued, control must remain with the army. There seemed to be lack of understanding of the fact that, as the army advanced, it was setting up the former administration under army direction.

As an outcome, on the recommendation of the recently-appointed Minister for External Territories, Mr Ward, the Cabinet decided to appoint a sub-committee of Cabinet to consider post-war policy for the territories. It was to include the Ministers for the Army, Post-War Reconstruction,

External Affairs, Transport, External Territories, Health and Social Services, the Treasurer and the Attorney-General, and was to discuss its problems with the Commander-in-Chief.

When the sub-committee had its first meeting, on 10th February, Conlon accompanied Blamey, who explained that “a major part of the function of the Director of Research and his staff was to advise the Commander-in-Chief upon all matters relating to the administration in occupied or re-occupied territories”. The sub-committee, on Blamey’s advice, decided that the functions of the departmental committee of which Paton was chairman should be carried out by the Department of External Territories which should collaborate with Conlon.

Blamey added that the role of the Directorate of Research was in conformity with Paton’s recommendation for the creation of a Directorate of Civil Affairs, and that plans for establishing a school of civil administration were ready to proceed. The Cabinet sub-committee agreed that the school should be controlled by the Director of Research. The staff of the directorate contained in the higher ranks none excepting Murray, Hogbin and Stanner who had served in a field formation, and none (except Stanner and Major Penglase, who was attached to the directorate for a month after his return from the tour with Professor Paton) fulfilled the requirement Paton had recommended by being “a person with experience of native administration”.17 In April Stanner and Major Kerr18 (who had joined the army in 1942 as a research officer in what later became the Directorate of Research) were attached to the Australian Army Staff in London. They arrived there at the same time as General Blamey, when he attended the Prime Ministers’ conference mentioned earlier. Their tasks in London were to study post-hostilities planning, Civil Affairs, the research activities of the General Staff, and “the structure of financial and other controls at the War Office”. Conlon arranged that they should advise Blamey on diplomatic matters and Civil Affairs problems.

In consequence there were exploratory conversations of problems of military administration in London in May between General Smart and General Hone19 of the War Office, and between General Blamey and Sir Frederick Bovenschen,20 Under-Secretary of State at the War Office. In the following eight months Stanner sent reports on Civil Affairs doctrine and organisation to LHQ, some of them the result of study of the British Civil Affairs set-up operating in Holland, France and Belgium.

He had discussions with several British officers earmarked for service in Borneo.

Planning for the re-establishment of the administration in Malaya, Hong Kong and Borneo had been in progress at the Colonial Office in London since 1942.21 In October 1943 planning had reached a stage where Mr Macaskie,22 Chief Justice and Deputy Governor of North Borneo, was appointed Chief Planner and Chief Civil Affairs Officer designate (CCAO) for Borneo, and by early 1944 five other officers had been added to his group.

Because Borneo was likely to fall within an American or Australian area of operations, a Combined Civil Affairs Committee had been set up in Washington in July 1943. One clause of its charter read:

When an enemy-occupied territory of the United States, the United Kingdom or one of the Dominions is to be recovered as the result of an operation combined or otherwise the military directive to be given to the Force Commander concerned will include the policies to be followed in the handling of Civil Affairs as formulated by the government which exercised authority over the territory before enemy occupation. If paramount military requirements as determined by the Force Commander necessitate a departure from those policies he will take action and report through the Chiefs of Staff to the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

In May and July 1944 a memorandum on policy in Borneo and Hong Kong, prepared by the War Office and the Colonial Office, was accepted, after slight modification, by the Combined Committee as a statement of policy under the clause quoted above. It stated the views of the United Kingdom Government that the administration of British Borneo and Hong Kong should be entrusted to a Civil Affairs staff mainly comprising British officers, mentioned that planning groups for those territories had been assembled in London, and asked that the directives to the Force commanders concerned should include instructions on these lines. A more detailed statement prepared by the Borneo group, and accepted, stated that it was intended that the CCAO, British Borneo, should advise on the British Government’s plans for long-term reconstruction and

should at the discretion of the Allied Commander-in-Chief, while keeping the latter, or the military commander designated by him, informed, be authorised to communicate direct with London on questions which do not affect the Allied Commander-in-Chief s responsibilities for the military administration of British Borneo.23

On 14th November 1944 General Blamey, now in Australia again, cabled to General Smart in London that he had asked Sir Frederick Bovenschen to send out a Civil Affairs staff officer and that planning

for the administration of Borneo must begin soon. If the responsibility fell on him he wished to proceed on lines acceptable to the British authorities. It was desirable that as many suitable officers as possible with experience in Borneo should be made available. They could be given commissions and transferred to the civil administration later if desired. Smart was to take the matter up with the United Kingdom authorities.

In December 1944 a War Office liaison officer on Civil Affairs, Colonel Taylor,24 arrived in Melbourne. Already a unit known as 50th Civil Affairs Unit, with an establishment of 145 officers and 397 other ranks, including 241 Asians, had been sanctioned by the War Office. In December Colonel Stafford,25 Controller of Finance for the unit, left for Australia to arrange for the unit’s reception; in February the advanced party under Colonel Rolleston26 left, and in March the main party, under Brigadier Macaskie, the CCAO.

Taylor had brought with him the War Office war establishment of the 50th Civil Affairs Unit. Blamey, however, on the advice of his staff, expressed the view that the war establishment prepared by the Directorate of Civil Affairs at the War Office was unsuitable and ordered the preparation of a revised establishment “more suitable for the military phase”. It provided for small sections of the General Staff, Adjutant-General’s and Quartermaster-General’s branches to ensure proper coordination with the force to which the unit would be attached – “a valuable provision, the need for which was not realised till much later in other theatres”.27

Telegrams were now exchanged between the War Office and LHQ with the result that, on 17th March, the War Office agreed that an Australian Civil Affairs organisation should be set up with an Australian war establishment. The War Office expressed the hope that the best possible use should be made of the United Kingdom staff.

On 9th April, the Australian war establishments for Civil Affairs units having been prepared and approved by the War Office, Lieut-Colonel K. C. McMullen, Regional Commander of the Islands Region in Angau, was ordered to fly from his headquarters at Torokina to Australia to raise a detachment under the Australian Civil Affairs establishment.

That day 35 officers of the 50th Civil Affairs Unit, largely officers of the Borneo administrations, reached Australia. They found themselves faced with a baffling situation. A primarily-Australian Civil Affairs force, to be named “British Borneo Civil Affairs Unit”, was being organised to do the task which they had been planning for some years and had travelled from England to perform.

Later in April Blamey approved the war establishment and partial raising of the British Borneo Civil Affairs Unit.28 Authority was given to raise two “area headquarters”, two “Type A detachments” (each 18 officers and 44 other ranks) and two “Type B detachments” (14 and 31). Blamey directed that his headquarters would be responsible for equipping and mobilising the unit, subject to the best possible use being made of any United Kingdom officers made available by the War Office. The unit would communicate with LHQ and the Allied Intelligence Bureau through the Director of Research and Civil Affairs. The total war establishments provided for 210 officers (including a brigadier, 6 colonels and 17 Lieut-colonels) and 493 other ranks, of whom 259 might be Asians.

On 23rd April Conlon, after a discussion with General Blamey, wrote General Berryman a letter about the arrangements being made for the Borneo Civil Affairs Unit. In it he made some disparaging remarks about the British unit and said:

It will be difficult, if not impossible, to use most of [the 35 British officers] during the operational phase. ... I have instructed that they concentrate at Ingleburn, and

I have told the CO that we do not recognise the Colonial Office during the operational phase.

Conlon added that McMullen’s detachment would be “predominantly Australian”, and that he proposed that four Civil Affairs detachments be raised, with a headquarters under McMullen for attachment to corps headquarters, but that “we keep most of the present British officers at Ingleburn as a sort of rear headquarters until it is prudent to send them in”. He said that Colonels Gamble29 (of the Army Legal Corps, appointed to the directorate in April) and Stafford were going forward to confer with Berryman. Conlon sent Blamey (who was then at Morotai) a copy of his letter to Berryman. At the same time he informed Blamey that he was taking steps to form the two Type “A” and two Type “B” detachments, and had asked that Lieut-Colonels Stanner and Tasker30 be flown from America, where since February they had been attending the School of Military Government at Charlottesville, to become detachment commanders.

The Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs, which had achieved the foregoing results, contained few officers with real military experience, yet it was organising and controlling military units, a task requiring expert

staff work. At the same time the directorate was causing confusion and distress among the British Borneo officers who had arrived to perform a task for which they had long been preparing. The 50th Civil Affairs Unit became a holding centre from which its members were gradually seconded to the Australian Army. The field headquarters of BBCAU were placed under the commander of the force invading British Borneo, and in technical matters the unit was under the control of DORCA

Difficulties arose (writes the United Kingdom official historian) from ... the facts that the CCAO was excluded from planning and preparation in the Directorate and that the Task Force was placed under the command, not of the senior officer, the DCCAO of the British unit, but of one of his juniors, a Lieut-Colonel of the Australian unit.31

Blamey on 26th April instructed Conlon that the United Kingdom officers were to be used whenever reasonably qualified and that a proportion of them must be sent forward. An advanced party of BBCAU arrived at Morotai on 2nd May, and the remainder of one Type “A” detachment began to arrive on 7th May. That day Conlon informed Blamey that the first BBCAU detachment had embarked under the acting command of Lieut-Colonel Lohan,32 a British officer, but that Lohan had been informed that a commanding officer would be appointed later; 12 United Kingdom officers were now attached to McMullen’s group.

Blamey was also informed that a Borneo Civil Affairs mission was to be attached to General Headquarters. He cabled to Smart that he was dissatisfied with the attitude of the War Office; the matter should be left entirely in the hands of the Australian command; all details had been completed in cooperation with Stafford (who had replaced Taylor as liaison officer with the War Office). Later, however, Blamey agreed with the War Office as to the need for a joint Civil Affairs mission at GHQ and Stafford joined GHQ at Manila in May.

In the course of a letter to Bovenschen on 1st June Blamey explained the circumstances surrounding the decisions about BBCAU and said that he hoped to bring Macaskie and some of the remaining officers forward as soon as possible, although he was not sure that Macaskie should not remain in Melbourne “where the major issues of policy are likely to arise”.

All these decisions had been made by Blamey and his staff on their own authority. On 23rd May, however, the acting Minister for Defence had stepped in, and had written to the acting Minister for the Army seeking a fuller statement from Blamey on the matter, including any directions issued by General MacArthur. He drew attention to the recent decision to attach a United Kingdom Civil Affairs mission to GHQ “to assist the Allied C-in-C (or the Military Commanders designated by

him) to carry out the military administration in accordance with the policy of His Majesty’s Government” and expressed a desire that the administration of the Borneo colonies should be entrusted to the British Chief Civil Affairs Officer, subject to the general directions of the military commander. The only result, however, was that on 28th May the War Cabinet approved the raising of BBCAU but expressed the view that it should have been consulted before the commitment was entered into; it limited the number of Australian officers to be attached to the unit to 50.

The work of BBCAU in the field will be discussed in a later chapter, but some of the immediate consequences of the policy of the Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs may best be mentioned here. The report of the 9th Division says:

Owing to the change in the task allotted to 9 Aust Div from Oboe Two (Balikpapan in Dutch Borneo) to Oboe Six, the BBCAU party received only 24 hours’ notice before leaving Australia for Morotai. The advance party arrived on 30 April 45. Personnel of the unit arrived by different routes, with personal baggage only, without any unit stores, equipment or transport, and with no knowledge of the nature and area of the impending operation except that it was to be in British Borneo. The unit was equipped from Adv LHQ, I Aust Corps and Divisional resources. ...

No approved War Establishment of BBCAU was available until 26 May, just before embarkation. The personnel available (about 29 officers and 25 other ranks) were part of a percentage of a Type lA Detachment and a percentage of HQ BBCAU, but as many of the appointments had not been filled, an improvised organisation was made.33

On 15th June, five days after the 9th Division had landed round Brunei Bay, Lieut-Colonel McMullen appealed to the headquarters of the division for an increase in the strength of BBCAU. He pointed out that only one of the four detachments comprising the unit was then in Borneo and that the remainder were held at Ingleburn Camp, Sydney. “The rest of the UK personnel of the unit, mainly consisting of those designated by London for HQ BBCAU are held on the strength of 50 CAU (a UK war establishment) located at Ingleburn Camp,” he wrote. He urged that the Chief Civil Affairs Officer (Brigadier Macaskie) and 13 other officers, whom he specified, including the Finance Officer, Agriculture Officer, Legal Officer, Labour Officer and others, and such other officers as Macaskie wished, should be sent forward. He considered that the military administration of British Borneo would be jeopardised if the unit was not strengthened in this way.

General Wootten, the divisional commander, concurred on the 16th, expressing the opinion to General Morshead, the corps commander, that the existing headquarters was “totally inadequate”. Morshead’s headquarters on Morotai did not receive Wootten’s message until 24th June. On the 26th Morshead signalled LHQ asking that Macaskie and his staff be flown to Labuan as soon as possible. The Adjutant-General ordered the expansion of BBCAU on 27th June; Macaskie and five others were to fly to Labuan immediately; the movement of the main

body by sea was ordered on 8th July. Macaskie took command of BBCAU in Borneo on the 22nd. In August when the unit was almost fully staffed it had 138 Australian officers and 48 British, and six of the seven detachments were commanded by Australians.34

While problems concerning Borneo were absorbing much of the attention of Australian staffs MacArthur’s American armies were heavily engaged far to the north-east. Throughout April, May and June fierce fighting raged on Okinawa. It was not until the last week of June that organised resistance ceased, by which time the Americans had lost 12,520 killed, and the defenders 61,000 killed and 7,400 prisoners; between July and November the number of prisoners increased to 16,000. In June heavy resistance ceased on Luzon although “sizable pockets” of resolute Japanese were still fighting. On Luzon 317,000 Japanese had been killed and 7,200 taken prisoner; the Americans had about 60,000 casualties. On Okinawa and in the Philippines at the end of June the armies were making ready for the invasion of the Japanese mainland; the President’s approval had just been given for an invasion of Kyushu on 1st November, by a force of ten divisions.