Chapter 18: Tarakan: The Garrison Destroyed

BY the evening of 6th May fairly copious information obtained from prisoners and Indonesians and from captured documents indicated that the enemy had about 390 naval troops in the Mount Api area, about 400 troops and civilians in the Fukukaku headquarters area (embracing Hills 105 and 102), 200 from Sesanip along Snags Track to Otway, 300 on Otway and in District VI, 300 in the Amal River area and 60 at Cape Juata. Having lost the airfield and the water-purifying plant and hospitals “the enemy at this time was displaying a decided disinclination to hold ground. In particular he was shunning any ground which could be subjected to heavy bombing, shelling, or attack by tanks; or against which large-scale attacks could be launched by our troops”;1 and he was directing his operations to delaying the attackers, particularly with mines, booby-traps, suicide raids, and isolated parties fighting to the death in tunnels and dugouts.

In concentrating on the main task – the capture of the airfield – the brigade had by-passed pockets of resistance such as that at Peningkibaru, whence the enemy could bring down small arms fire on 400 yards of the Anzac Highway. Also there was now need for more living space for the Indonesian refugees.

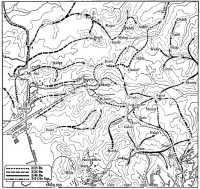

The enemy fire on the Anzac Highway had been countered by posting tanks on the road whence they used their howitzers and machine-guns. Brigadier Whitehead now decided to capture the high ground overlooking the airfield along the line of Snags Track from Mount Api to Janet, and thus secure the airfield from counter-attack, raids, or indirect fire. This task was given to the 2/23rd Battalion; at the same time the 2/24th was to exploit towards Juata oilfields and patrol the high ground between the airfield and Lyons to ensure a link with the 2/48th. In addition Whitehead proposed to clear the enemy from the high ground overlooking Tarakan town and from Districts IV and VI. To achieve this the 2/48th Battalion would gain the high ground north of the town as far as Snags Track, and the 2/4th Commando Squadron, having cleared Tarakan Hill, would advance along Snags Track towards the Sesanip oilfields. At the same time the 2/3rd Pioneers would sweep the high ground east of the town and advance along the line of John’s Track to the mouth of the Amal, and the NEI company would clear the enemy from the Cape Batu peninsula.

Air attack and the artillery were giving formidable support to the infantry, particularly by tearing away the vegetation covering the tangled ridges, but interrogation of prisoners indicated that most of the casualties inflicted during preliminary bombardments were being caused by mortar fire – a not unnatural event in this terrain, which was more broken than

any this brigade had experienced. Of seven prisoners who, in the second half of May, were questioned as to what weapons were causing casualties, four said that they were caused mostly by mortar fire, another’s reply was that five in his group had been killed and 8 wounded by one mortar bomb, and another declared that 300 to 400 casualties had been caused by mortar fire (where or when is not mentioned). The artillery problems on Tarakan were baffling For example,

each knoll on the map was exceedingly difficult to pinpoint on the ground; and, from the air, it could not be clearly identified beneath its mantle of forest, unless marked by Smoke. It could not, in most instances, be seen by the OPO [observation post officer] directing fire on to it; for he was often a quarter of a mile away with the infantry on another knoll, his own visibility less than 20 yards! He relied almost entirely on sound ranging. When he “thought” by the “sound” he was “about the place”, he “gave it the works”, or the CPO [command post officer] prepared a fire plan! If there were two or three OPOs on separate knolls, and each could give a sound bearing, so much the better – an unusual method of cross “observation”. ...

When trees collapsed through constant fire and the rounds got through, it frequently depended on where the guns were sited, and at what angle, as to whether the shells hit on one side of the razor-back or the other. ... It occasionally happened that a fire plan which started on the target began to overshoot the mark by as much as 200-300 yards when the timber started to fall, and the rounds continued unimpeded. This did not matter if our own troops were on the same side as the guns. Sometimes, however, they were on the opposite side as well.2

It was soon apparent that the Japanese were determined to fight for every commanding knoll. In the Mount Api area the 2/23rd met strong resistance, particularly on Tiger, a sharp ridge south of and parallel to Snags Track, which ran through the hills linking the town with the airfield. The defenders of Tiger were protected by pill-boxes and tunnels. One company took the western end of the ridge on 7th May and pressed on next day but was forced back by a counter-attack. The battalion met heavy resistance also on Crazy Ridge. A bridge on Snags Track 150 yards east of Anzac Highway had been blown and it was not possible for the engineers to replace it until the 7th because enemy weapons covered the area. This done, however, tanks came forward and on the 7th and 8th the battalion and the tanks cleared about 200 yards of the track. On the 9th a platoon patrolling towards Snags Track from the north-east of the airstrip was ambushed and six men were hit. Private Dingle3 rushed forward and fired his Bren while the wounded were rescued.4

That day the 2/24th relieved the 2/23rd, which had been in constant contact with the enemy since the landing. Also on the 9th a long-distance patrol of the 2/24th under Lieutenant Walker had driven the Japanese

6th May-16th June

out of Juata after a skirmish. In the central sector on the night of 6th–7th May the men in the forward posts of the 2/48th heard much movement among the Japanese round Sykes, and decided that they were collecting their dead and wounded on the lower slopes. Japanese riflemen were active next day and hit three men, including Lieutenant Burke who died of his wound.

Also on the 7th Captain Lavan’s company of the 2/48th, with support from artillery, mortars, machine-guns and tanks, occupied Otway without opposition. Patrols from Sykes found the enemy holding the main ridge running north in strength. Tanks could not penetrate this thickly-timbered country and, here as elsewhere, it was difficult to direct artillery fire.

Early on the morning of the 8th a Japanese raider crept into the main dressing station of the 2/11th Field Ambulance and placed an improvised bomb under a bed occupied by the gallant Lieutenant Freame of the 2/24th. When the bomb exploded it killed Freame and injured two others.

Farther to the right the 2/4th Commando by the 8th had cleared Snags Track as far as Haigh’s, beyond which the tanks could not go. On 9th May a section, probing forward, was halted by sharp fire which killed two men. Mortars put down smoke to help a withdrawal, but the crews of aircraft, thinking this smoke indicated a target, bombed the area, fortunately without causing casualties. That night Japanese raiders were in the headquarters area using 12-foot spears and throwing 75-mm shells.

All nerves on edge (wrote the squadron’s diarist) and men snatching some sleep in the day time. Morale of troops high but men tiring. ... Operational rations offer no invitation to eat well.

So far this small unit had lost 7 killed and 19 wounded.

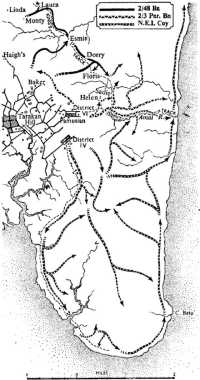

The 2/3rd Pioneers, having left one company in a defensive position on Tarakan Hill and another on Evans, moved out on 7th May to perform its task of advancing along John’s Track, which followed the course of the Amal River. They met unexpectedly strong resistance. The leading platoon came under heavy fire just east of Pamusian; it attacked and one man was killed and the company commander, Captain R. L. Dunn, and one other wounded. A second attack after artillery fire – Colonel Anderson had a battery of the 2/7th Field Regiment in support – also failed. That night Anderson gave orders for an attack in which, while part of his force held the enemy in front, another part would circle round, cut the track behind the enemy and then advance westward.

This attack, by Captain Hincksman’s5 company, opened at 9 a.m. on the 8th. The platoon leading astride the track reached a point 50 yards beyond that at which the advance had been halted the previous day, and there met heavy fire. The rest of the company, sent out to encircle the enemy position, moved into very dense bush through which the men had to hack their way. They could advance only 200 yards in an hour, and, when it was evident that the movement could not be completed before nightfall, the company returned and formed a perimeter at the starting point. That night Anderson brought Major H. G. M. Rosevear forward to lead a company on a wide outflanking movement to the left.

While this was in progress accurate artillery and mortar fire was brought down on the enemy’s position, one shell making a direct hit on the bunker commanding the track; and Lance-Corporal Pallister6 brought a Vickers gun into action in a very exposed position and, until wounded, pounded the bunker with incendiary bullets. At 11 a.m. on the 9th the Japanese abandoned the bunker and at midday Rosevear’s company reached the track farther east. Hincksman’s then passed through and, at 1.15, came under fire at the junction of John’s Track and Helen Track. A platoon sent to the flank reached a creek 30 feet wide on the opposite bank of which Japanese were dug in. Leaving a section here Lieutenant Bethell7

6th–16th May

took the rest of the platoon wide to the right and manoeuvred the enemy out of this position. The Japanese rallied 40 yards beyond, but the platoon drove them from this and another position a similar distance farther on. Their next position, however, proved too strong. In two hours and a half Bethell’s platoon had fought three sharp and successful actions, and had lost four men wounded. Next day (the 10th) a platoon was sent eastward along the track to cover this flank while Hincksman’s company attacked the position on the Helen feature. The flanking platoon (Sergeant Holmes8) found a strongly-defended position and a second platoon was sent south of the track to outflank it. After 200 yards it came under heavy fire and two men were killed and two, including Lieutenant Keys,9 wounded. It was now evident that the Helen feature was strongly held and was an important enemy position.

At 1.30 p.m. Colonel Anderson ordered Hincks-man to advance directly on to Helen, but the men were halted by heavy fire after 50 yards and dug in. The two companies had now been in action on three successive days, and Anderson ordered the two left near Tarakan to relieve them next day. During the relief a sniper’s bullet hit a grenade attached to Bethell’s belt and detonated and wounded him seriously.

At 8.25 a.m. on the 12th one of the fresh companies (Captain C. C. Knott) attacked after heavy artillery and mortar fire, directed by Captain

Morish10 and Lieutenant Whibley11 respectively from the forward edge of the infantry position on to targets as close as 40 yards away. The objective was a long razor-backed ridge sometimes only 3 feet wide on top and with almost sheer sides. It was covered with scrub and the bombardment had thrown in the path of the attackers a tangle of fallen limbs of trees; this not only impeded the advance but also improved the defenders’ field of fire.

The leading platoon (Lieutenant Travers12) met concentrated fire but pressed on. Corporal Mackey’s13 section which was leading was under fire from three well-sited positions at the top of an almost sheer rise. Mackey, with whom was Lance-Corporal Riedy,14 charged the first machine-gun post, but slipped and fell into it. A Japanese seized him but he struggled free, bayoneted the Japanese, and, with Riedy, killed the others in the post. Covered by Riedy’s fire, Mackey then charged another post with overhead cover containing a heavy machine-gun and threw a grenade through the firing slit, killing the gun’s crew. He then borrowed Riedy’s Owen gun and charged up a steep bank towards the third post, firing as he went. At the edge of the post he was hit and fell but not before he had silenced the enemy’s machine-gun. He had killed at least seven Japanese and taken three machine-gun posts. When Riedy saw Mackey fall he went forward to bring him out but found him dead. Riedy remained there firing at very close quarters until he was wounded.15

Travers reorganised his platoon, in which every NCO had now been hit, and kept up heavy fire to help another platoon (Sergeant Jones16) which was moving round the left. The platoon fought at close range for three hours and, when ordered to withdraw, only Travers and three others were occupying the position. Jones’ men, after struggling through fallen branches and thick undergrowth, came under converging fire and were forced back. It was now midday, the fight had lasted three hours and a half and 9 had been killed and 19 wounded – half the strength of the attacking force.

On the morning of 13th May the attackers withdrew about a mile, destroyers and the 2/7th Field Regiment bombarded the feature, and Lightning aircraft dropped napalm bombs. However, none of these bombs fell on the Japanese positions and the naval fire was not very accurate. One shell hit the track less than half way back to the start-line. The Japanese were sited along the razor-back track running up the feature,

which from the bottom presented a series of false crests, ideal for defence since the attacking troops, after crossing a crest, could not be seen or supported from the rear.

To cope with this problem Captain Esau,17 whose company was to renew the attack, asked for flame-throwers, the intention being to fire them from below each crest and carry out the attack to the summit in a succession of bounds.

A platoon from Knott’s company acted as an advance-guard for Esau’s company on its return to Knott’s former position, from which the attack would be launched, but progress was so slow that the timed artillery program was finished well before Esau’s company arrived at the start-line.

At 12.25 p.m. the company attacked, with one platoon assaulting, one holding astride the track in the position occupied the previous night by Knott’s company, and the third platoon in reserve in the rear. Lieutenant Ormiston,18 whose platoon led the attack, reached the scene of the hard fight on the 12th and came under heavy fire from the Japanese on the top of the next crest and from positions at the base and sides of the rise to the crest. One section, however, got to within 25 yards of the enemy and thence Corporal Shanahan19 went forward alone firing a Bren. When this weapon jammed he went on with grenades, threw two into a pit and silenced it but was then killed. He had made the greatest advance up the track of anyone in any of the attacks. Ormiston was killed while leading another section forward, and the attackers were withdrawn, having lost 4 killed and 7 wounded. The flame-throwers unfortunately were left at the rear and not fired.

On 14th May Liberator aircraft were used in close support for the first time, the targets being the Helen and Sadie features, and Lightning fighters dropped napalm immediately after the bombing. This combination proved most effective and thereafter was the kind of air support that was always asked for.

At dawn next day a platoon was sent forward to discover whether the Helen feature was still occupied, and at 7.30 the platoon commander reported that the hill had been abandoned. So ended what the battalion considered the most protracted and difficult fight in its history – a history which included an arduous campaign in North Africa and another in New Guinea. In the course of the operation about 7,000 shells and 4,000 mortar bombs were fired.

The Japanese withdrawal from the Helen feature left John’s Track unguarded and on 16th May the Pioneers reached the coast at the mouth of the Amal River. They had done their job, but at a cost of 20 killed and 46 wounded.

The Japanese force on and round Helen had consisted of about 200 men under Lieutenant Fudaki. It had been guarding the beach at the Amal when the Australians landed and had then moved to the position forward of Helen. It lost heavily there on 9th May and withdrew to the Helen feature. Fudaki expected the Australians to advance along John’s Track and intended to move in behind them. Bethell’s platoon discovered his positions, however. Fudaki withdrew from the Helen feature after he had lost about half his force and when he seemed likely soon to be surrounded.

As the troops pushed into the more thickly timbered country greater use was made of air support. Until the 8th four Mitchells had been overhead during the daylight hours and each battalion had an air-support party with direct call on these aircraft, subject to the possible intervention of brigade headquarters, which listened in. The Mitchells proved too inaccurate against confined targets and their bomb pattern covered too wide an area to silence enemy positions. As a result these aircraft were usually directed to more distant objectives.

In the second week of May the 2/4th Commando Squadron was strenuously patrolling forward of its sector and becoming very weary. On the 13th the enemy became more aggressive in this area: about 30 attacked on the Agnes feature and were repulsed losing about 16 killed. On the 15th “B” Troop advanced farther along a spur on Agnes with the object of taking the crest of the feature, and in mid-afternoon the forward section, 16 strong, under Lieutenant Stanford,20 was digging in on the objective when some 50 Japanese suddenly counter-attacked, making a “Banzai” charge from about 40 yards away. Again they were repulsed and mortar fire was called down on the survivors. One Japanese had got to within three feet of Trooper Collett.21 He fired a burst from his Owen gun and the man fell. Later Trooper Nugent went out to search this body but the Japanese sprang up, hurled a grenade and made off – an occurrence the commandos attributed to the wearing of a bullet-proof vest. Next morning a patrol counted 20 dead Japanese within a few yards of the crest and 2 more farther along the track. The Australians were sure that other dead and wounded men had been carried out in the night.

After three days of strenuous patrolling the 2/48th on 12th May had set out to cut King’s Track with two platoons so as to intercept Japanese who were withdrawing from the Helen and Sadie features, and to clear the heights from Sykes to Butch. The two platoons succeeded in cutting the track and by the late afternoon had each set an ambush. Captain Gooden controlled these platoons from a headquarters on Esmie. On the 13th patrols reached Dorry and Floris.

On the left the 2/24th Battalion was meeting strong resistance. A tank reconnaissance officer, Captain Austin,22 and another were killed in an ambush on Snags Track on the 10th. Between Travis’ company and

Shattock’s was the strongly-defended Tiger feature. Both Lieutenant Sargeant23 from Travis’ company and Lieutenant Stretch from Shattock’s had led out reconnaissance patrols and made contact with the enemy. Stretch then led forward a fighting patrol but was forced to withdraw. That afternoon Travis was killed by a sniper while seeking a position from which to direct tank fire from his flank and Sargeant took command. The company made further attacks but without any success. Lieutenant Endean’s24 company was in contact that afternoon on Hill 105 which, like the position Sargeant’s company was attacking, was heavily fortified and was to become the scene of a long struggle.

On the 11th a platoon of Endean’s company was held up by fire from a scrub-covered knoll about 30 yards ahead. Two flame-throwers were brought up and Sergeant Campbell25 opened fire with thin fuel and cleared all the scrub between the platoon and the enemy’s post, while the riflemen advanced behind the screen of flame and smoke. Campbell next fired with thick fuel. The position was then found to have been abandoned.

Artillery was the only answer to the Tiger problem and on the 11th flares were fired into the enemy’s position from both the east and west to indicate the target. After an artillery concentration a platoon of Sargeant’s company dashed forward just in time to race the enemy to the positions they had vacated during the bombardment. These tactics were repeated and finally the two companies occupied the feature which was a maze of pill-boxes and foxholes.

One pill-box remained in the enemy’s possession. Major Serle26 now took command from Sargeant. Attacks with a flame-thrower next day failed to dislodge the enemy from this last position but on the night of the 12th–13th there was a great explosion and at dawn a patrol found that the enemy had blown up a big tunnel and abandoned the pill-box. Meanwhile patrols from Shattock’s company had probed about 1,000 yards South-east, cutting Snags Track at several places.

On the morning of the 13th Lieutenant Freeman’s27 platoon set out to attack the knoll north of Snags Track which had now resisted attacks for two days. Lance-Corporal Casley28 opened fire with a flame-thrower, killed two Japanese and then ran forward to the top of the knoll, but was hit by a burst from a machine-gun as he began firing again. A bullet punctured the flame-thrower and burning fuel gushed out. Casley dropped the flame-thrower and ran back with his clothes on fire; he died of his injuries. That evening after the Japanese position had been bombarded

by mortars, tanks and two 2-pounder guns, Freeman attacked and took the knoll. On the 15th Serle’s company took Elbow but was forced out by fire from a 75-mm gun firing at point-blank range. This was shelled and next day Elbow was reoccupied.

By the 16th the 26th Brigade had lost 11 officers and 137 men killed, 22 officers and 353 wounded; 9 officers and 243 men were sick. As most of this loss had been suffered by the infantry, the brigade had lost the equivalent of a battalion. The counted Japanese dead numbered 479 but only five prisoners had been taken. The brigade’s task was proving, in Whitehead’s words, “far more difficult and tedious than anticipated”, and now the enemy was holding country that was more inaccessible and rugged than the Intelligence staffs had been able to ascertain. The cover by aerial photographs had been poor, but this was offset by the capture of the excellent Dutch oil survey map which showed contours at one-metre intervals and provided detail lacking in the 1:25,000 maps with which the brigade had been equipped.

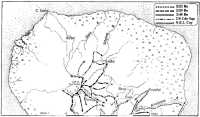

On 17th May it was estimated that 1,200 effective Japanese troops remained; no doubt more than 400 others were sick or wounded – escaped NEI prisoners had reported that there were up to 300 patients in the Fukukaku hospital alone. Captured maps and other sources showed that the enemy was holding in strength Hill 105, thence along a line to the south through Margy to Janet on Snags Track, then South-east through Ostrich, Galah and Susie. A company of the 2nd Naval Garrison, the best troops, with a company of Tokoi Force (the army component) were on Hill 105, Margy and Janet. It still seemed certain that the enemy’s intention was to make a last stand round the Fukukaku headquarters area.

Whitehead decided to maintain pressure along the line Hill 105-Susie; to penetrate as far as possible along the valley running north-west from between Agnes and Linda toward the Fukukaku area, to patrol the high ground east of Hill 102, gain control of the main Japanese track from the Amal River to Hill 102 and close in on the Fukukaku area from the east and north-east of Hill 102, thereby cutting off escape. He would turn the defences in the north, and prevent escape in that direction, and thrust east just north of Hill 105 across the north-south track and thus cut off the forces farther north from the main defence system.

The remaining positions on Hill 105 were bombed and bombarded and on 18th May the hill was attacked by Lieutenant Ingham’s29 platoon of the 2/24th. One pill-box was still defending the area and the approach to it was along a razor-back cluttered with fallen timber. Ingham and a Bren gunner charged and took the pill-box. It was found that many Japanese in the area had been killed by bomb blast. The enemy was still holding 500 yards along the ridge. Next morning Ingham’s platoon attacked this position, which could be approached only in single file. Without being seen the attackers drew close enough to roll grenades into the foxholes. One grenade was thrown back by a Japanese marine who

leapt up with bayonet fixed. He and others were shot and the remainder fled. The 105 feature was now entirely in Australian hands.

From 14th to 17th May patrols of the 2/48th had probed forward killing from 6 to 12 Japanese each day and themselves losing only 7 killed or wounded in the four days. It was decided that the enemy positions on Susie, Mamie, Freda and Clarice were too strong to be attacked by the 2/4th Commando and the 2/48th was given the task. At dawn on 19th May Lieutenant Derrick’s platoon followed at 7.30 by the remainder of the company (Captain Gooden’s) moved from Ossie to Agnes to attack the Freda feature – the vital ground – after an air and artillery bombardment. The aircraft attacked from 9.10 to 9.26 and the artillery went into action, as Derrick’s platoon advanced. They met strong opposition before reaching Freda and pressed on, only to discover that they were on the wrong track and were approaching Clarice not Freda. Later they withdrew for the night. Meanwhile another company (Captain Lavan) occupied the Laura feature.

On 20th May, after early morning patrols from Derrick’s platoon had returned, it was decided to advance along Freda from east to west. Sixteen aircraft dropped napalm on the Japanese area and the artillery bombarded it, but the attacking infantry found the feature too strongly held and again withdrew. Next day 500 mortar bombs were fired on to Freda and Track Junction Knoll but after some sharp fighting the enemy remained in possession.

It was now evident that if the Freda hill was to be taken the attack must have heavier support. Therefore, on 22nd May, 12 Liberators and 12 Lightnings were sent out with bombs and napalm, but the cloud was so low that some of the heavy bombers did not find the objective. Then the artillery and mortars fired, and a two-company attack went in, the infantry moving very close behind the barrage. Gooden’s company thrust from the east, and Captain Nicholas’30 advanced with one platoon pushing east along Snags Track towards Track Junction Knoll and another pressing north. The former platoon (Lieutenant Harvey31), moving through very difficult country along a razor-back so narrow that only two men could be deployed on it, edged forward under heavy fire; after losing one killed and 4 wounded and finding the enemy becoming stronger Harvey manoeuvred out of this position. It was then found that a wounded man was not with them, so Harvey and three volunteers thrust back and engaged the enemy fiercely while the wounded man was carried out.

During the day Gooden’s company on the right had encountered two strongly-held knolls. Derrick’s platoon succeeded in cutting the saddle between them and taking one knoll. Derrick’s platoon and another launched

a most courageous attack up the steep slopes of Knoll 2 in the fading light. Here, in some of the heaviest and most bitter close-in fighting of the whole campaign these two platoons finally reached the top and secured the Knoll after inflicting heavy

casualties on the enemy. ... [Lance-Sergeant] Fennell32 ... time and again ... crawled ahead of the attacking troops, even to within five yards of the enemy, and ... gained vital information. On one occasion, when his section was forced to ground he had charged the Jap positions with his Owen gun blazing and had silenced the enemy post, killing the occupants. In a similar manner, Private W. R. How33 ... found the advance of the troops checked by a well-sited pill-box, raced forward with his Owen firing until within grenade range, and then, throwing grenades, moved in for the kill until he fell wounded. He had silenced the post and killed the machine-gunner, thus allowing the advance to continue.34

At this stage 28 enemy dead had been counted; one Australian had been killed and 15 wounded.

Captain Hart’s “B” Troop of the 2/4th Commando Squadron was ordered to move from Agnes to Freda to reinforce the company there. This was difficult as the move had to be made after dark in unfamiliar jungle. Two sections joined Derrick’s platoon on Knoll 2. The Japanese evidently considered the Freda feature to be vital ground and, having been reinforced, hit back in force soon before dawn on the 23rd. In the hard and confined fighting that followed two were killed and eight wounded, including Derrick, who continued to give his orders for some hours after he had been hit in the stomach and thigh. Afterwards it was found that the platoon area was directly overlooked by a Japanese bunker on the main Freda feature – Derrick would certainly not have established his platoon there had it not been that the lateness of the successful attack the previous night had prevented him from seeing where the Japanese positions on the main feature were. The enemy was now so strong that it was decided to pull back, carrying out the wounded, and bombard the knoll again.

Next day it was learnt that Derrick had died. “This news,” wrote the battalion’s diarist, “had a very profound effect on the whole battalion as he had become a legend, and an inspiration to the whole unit. An original member, he had served with distinction through every campaign in which this battalion took part – Tobruk, Tel el Eisa, El Alamein, Lae, Finschhafen, Sattelberg, Tarakan. In what proved to be his last campaign he fought as ever with utmost courage and devotion to duty and his conduct and inspiration in the attack on Freda to a large extent accounted for the heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy in close-quarter hand-to-hand fighting.” An officer of a neighbouring unit wrote: “His loss was not only felt by his own battalion but the whole force.”

Except that they had lost Hill 105 and the Janet feature the Japanese dispositions had not changed between 14th and 22nd May. The sound of chopping and digging indicated that they were strengthening their grip. Examination of Hill 105 showed how strong the remaining defences were likely to be; it revealed a network of bunkers, trenches and shelters, many shelters being still undamaged despite bombing and shelling so heavy that the whole area was covered with a tangled mass of fallen timber.

At this stage the 4th Company of Tokoi Force plus the 1st Company of the 2nd Naval Garrison Force held Margy and Joyce; the 1st Company of Tokoi Force, and other troops were on Hill 102. In the north was a composite group. Two 75-mm guns remained. It still seemed likely that the enemy intended to make a last stand round the Fukukaku headquarters area, but there was some evidence that they were preparing an alternative headquarters on Essie.

Whitehead now decided that the time had come to assault the enemy’s last stronghold. He decided to concentrate the main effort on rolling up the Japanese from the north, where their defences were probably less well developed than elsewhere. There was no longer any need for haste, and no attack was to be made without maximum fire power being used beforehand. The general policy would be to attack each position with 18 Liberators carrying 500-lb or 1,000-lb bombs and then follow up with Lightnings carrying napalm. Since 15th May, however, it had become evident that 25-pounder ammunition would have to be used sparingly. The brigade had landed with 19,500 rounds, had been using about 800 a day, and there seemed to be no prospect of replenishment before 31st May. Consequently Whitehead took direct control of expenditure of this ammunition, which was not to exceed 500 rounds a day. As a result more mortar and machine-gun ammunition was used, and on 23rd May the use of these was also restricted.

It became evident that only one fully-supported attack could be made each day, and, because bombing by the Liberators was an essential part of the support and their arrival was dependent on the state of the weather, the decision to carry out an attack could not as a rule be made until the previous night. When this assault phase opened the plan was to use most of the fire-power resources in support of the 2/24th Battalion in its thrust along the Dutch Track from Juata oilfields towards Hill 105. At the same time patrols were to go to the north of the island to find whether the enemy was active between Fukukaku and Cape Juata and whether he was occupying the defences at Cape Juata, and patrols were to ascertain whether a track existed on the line of the Binalatung River from the coast to Fukukaku.

Captain Johnson’s company of the 2/48th took over at the Freda feature. Early on the 24th the Japanese sallied out and attacked this company, using grenades and 75-mm shells, and killed or wounded 6 men. A 2/4th Commando patrol now reported the Susie feature to be unoccupied. It was evident that the Japanese had withdrawn all their strength to the Freda feature, and, on 25th May, it was given a devastating bombardment by six Liberators with 250-lb bombs and 18 Lightnings with napalm, and by artillery and mortars. Johnson’s company followed the barrage closely and secured the knolls on Freda, and a company under Captain McLellan35 took Track Junction Knoll. The bodies of 46 Japanese

were buried in the area, most of them having been killed in the attack on the 23rd; in the day the 2/48th killed 21 more Japanese. For the next four days the 2/48th held the ground it had gained, and patrolled.

In the last 10 days of May the 2/23rd and 2/24th were in close contact with a resolute enemy. On 23rd May after 477 mortar bombs had been lobbed on to the Margy feature a platoon moved on to it but found the ground unfavourable and was withdrawn. That day a captured Japanese 75-mm infantry gun was assembled and sited on the edge of a cliff in full view of the Margy feature to support a company of the 2/23rd. There were two good reasons for using this relatively light gun: it was fairly easy to manhandle forward and though the supply of 25-pounder ammunition was dwindling there were some hundreds of rounds of Japanese gun ammunition. On the 24th the gun fired and virtually cleared the trees from the Margy feature. Next day it brought down very effective fire on the Japanese positions now revealed and a platoon of Captain Ferguson’s36 company of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion on Elbow fired 82 belts at the hill. Patrols thrust forward and had fierce fights with the defenders, but the Japanese held on.

The 2/24th Battalion was now stretched out from Juata to Crazy Ridge, occupying and flanking the Dutch Track for a distance of 5,000 yards or more. On 23rd May a company attacked Beech 2 without prior bombardment and was halted by electrically-fired mines, which caused 11 casualties. The wounded were brought out and the position mortared and shelled.

The enemy was strongly dug in among dense vegetation on the Droop feature. Lieutenant Ludbrook’s37 platoon got astride the enemy’s line of communication and held a position there during the night of the 23rd–24th, killing 12 Japanese in the course of repeated attacks. Thirty-six Liberators hit the hill on 26th May and completely cleared it of vegetation. A company then occupied the hill, advancing 1,000 yards in the day. When the advance was continued on the 27th after two strikes by Liberators, Private Christmass,38 the leading Owen gunner, was hit in the chest by rifle fire and knocked to the ground. He staggered to his feet and with his Owen gun blazing continued to advance, killing two Japanese before being shot in the arm. His action enabled his section to gain 300 yards of valuable ground.

An Indonesian prisoner reported that the first air strike had killed no Japanese but the second had killed 10 and also, unhappily, two Indonesian prisoners employed as carriers. The infantry killed eight more Japanese. A company of the 2/23rd made another attack on the Margy feature on the 29th supported by air, artillery and mortar bombardment but was forced back, losing 3 killed and 6 wounded. Margy was now under fire from seven guns in a single row firing at point-blank range – two 25-pounders, one 3.7-inch anti-aircraft gun, the guns of three tanks, and one

75-mm. On the 31st a heavier onslaught was made. In the morning 17 Liberators dropped 102 1,000-lb bombs, 16 Mitchells dropped delayed-action bombs and 15 Lightnings dropped napalm. At 11 a.m. a platoon advanced south towards Margy along a razor-back spur over much fallen timber. The first pimple was found to be unoccupied but farther on machine-gun fire halted the advance. One section moved round to the west, came in behind the enemy and cleared the intervening area and soon three of four knolls on the feature were secured. A second platoon was

then sent against Margy itself. The two platoons closed in on the fourth knoll, took it, and then occupied the Margy feature without opposition. In the mopping up next day 20 Japanese were killed and others were buried in their tunnels. One wounded man was taken prisoner.

At 11 a.m., after aircraft had attacked Poker 2 and 3, Major Serle’s company of the 2/24th and Captain Shattock’s advanced, Serle’s against Poker 2 from the north-west and Shattock’s against Poker 3. There was heavy fighting on Poker 3. At midday Lieutenant Amiet’s platoon attacked the dominating ground on this hill. The only approach was along a razorback spur – a two-man front – on which were tunnels and foxholes to a depth of 100 yards. After moving four yards the leading section came under a hail of fire and four men fell. Corporal Beale39 took his section through but it was checked immediately by grenades and small arms fire. Beale went forward, located the Japanese positions and threw grenades into one of them, then returned and sited the Bren guns of two sections. At this stage Amiet and the remaining section commander were wounded.

Beale took over, sited the third Bren, threw phosphorous grenades, and under cover of the Bren gun fire and the smoke led a charge. The position was taken and 13 Japanese killed. Beale had been wounded in two places but carried on. Another platoon now passed through. The dauntless Beale, firing a Bren from the hip, led the forward section of this platoon until a further 200 yards of the ridge had been gained. Altogether 14 Australians were wounded; 16 enemy dead were counted. Meanwhile Serle’s company could not make headway against Poker 2 that day but the Japanese abandoned it early next morning. The Dutch Track was now open from Juata to Poker 3.

On Hill 102 the Japanese facing the 2/48th were dug in on the highest point of a ridge only 20 to 30 feet wide and the only feasible approach was along a razor-back three feet wide. The defences consisted of five pill-boxes and some 30 rifle pits, with overhead cover. The hill was attacked on 1st June by 18 Liberators each with nine 500-lb bombs and 24 Lightnings with napalm. The Australians’ forward positions were only 100 yards from the enemy and were brought back about 350 yards before the aircraft struck, but machine-gunners of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion fired on the enemy from a flank to try to stop them from leaving their positions during the bombing or from moving forward into the Australians’ positions. After the bombing, at 4.45 p.m., Lieutenant O’Rourke’s40 platoon attacked, following, an artillery barrage as closely as they could, and bringing with them three flame-throwers. They gained the forward slopes without being fired on and then saw five Japanese moving towards them, evidently to re-enter their positions after the bombing. These were fired on while the flame-throwers were brought into action. One operator sprayed the slope from side to side while another fired straight up it.

The result was devastating (said O’Rourke later). The hill was set completely ablaze to a depth of 50 yards, two of the five Japs were set on fire and the other three killed in their posts. The platoon was able to advance almost immediately through the flames, and with the help of the flame-throwers the feature was completely captured within 15 minutes of the advance commencing. The flame which was fired up a slight rise hit the trees on the crest and also sprayed the reverse slope and had the effect of completely demoralising the enemy.

On 3rd June, after an unsuccessful air attack by 49 aircraft, Lavan’s company advanced on Wally from Hill 102 but found the enemy in strength across the track with a pill-box on each flank and weapon-pits farther back; fallen trees made it impossible to outflank the position. The forward scout got to within 15 yards of one pill-box but the enemy’s fire was fierce and the company had to withdraw. Next day 12 Liberators again struck Wally but again the infantry found the enemy still holding in strength. They reached the conclusion that the 250-lb bombs were too light and were bursting among the branches of the big trees.

In this period the 2/23rd was engaged clearing the remaining Japanese from Margy and its neighbourhood. On 1st June patrols killed 35 Japanese

bringing the total number killed on that hill to 118. On the 4th 36 Indonesian prisoners walked into the lines of the 2/24th waving white flags or shirts. On arrival they ran around laughing and shaking hands with the Australians; one said that 300 Indonesian prisoners who had been employed in the Fukukaku area had broken out on the night of the 2nd–3rd.

The 2/23rd was making good progress as a result of using guns sited on the Margy feature itself in close support. The unit was allotted one 3.7-inch anti-aircraft gun and two 25-pounders sited only 400 yards from the target. These guns systematically blasted the timber from the ridges and then, with the help of tank guns and a 2-pounder, battered the enemy’s posts one after another.

A letter was dropped to the Japanese on 4th June addressed to Commander Kahuru (the naval commander) and Major Tokoi (the army commander). In it Whitehead expressed admiration for Japanese courage, recalled how the Japanese had refrained from attacking a hospital ship at Milne Bay, and offered to take care of Japanese wounded. He suggested that Lieut-Commander Yamagata and one man should come forward on Hill 105 at midday on the 5th carrying a white flag and wearing a white brassard and there meet an Allied medical officer and discuss arrangements for treatment of Japanese casualties. A sketch was attached showing exactly where the Japanese representative should halt. This appeal was disregarded.

On 6th June Lieutenant Herbert’s41 platoon of the 2/48th moved stealthily from Hill 102 and dug in South-east of Wally. Three Japanese who walked towards this position were shot. Lieutenant Macdonald’s42 platoon followed and sent a patrol towards the north end of the Linda spur and were 20 yards from the top when they were fired on. It was decided that this approach was not a practical one.

Also on the 6th the Roger feature was given a devastating onslaught from the air and “D” Company of the 2/24th seized it from a Japanese garrison that had been dazed by the bombardment.43 Pressing forward from the Freda feature on the 7th a patrol of the 2/48th found the enemy in strength; Lieutenant Simper44 and one other were killed.45

On the night of the 8th–9th forward posts of the 2/24th reported that the enemy “seemed to be having a regular party” in the direction of the Paddy and Melon features. There was much singing and rattling of tins.46

Next day the brigade Intelligence staff warned the units that the enemy might on the 10th–11th attack over Hill 105 towards the airfield. Thereupon food and water were stored in company areas and preparations made to withstand a desperate final attack. At the same time Colonel Warfe issued orders for a general advance into the Fukukaku area if the Japanese moved out towards the airfield or beaches. A half-hearted attack was in fact made in the early morning of the 10th. There was small arms fire for half an hour and a field gun fired 11 rounds. An enemy aircraft arrived overhead and dropped three flares and one bomb. In the 2/48th’s area at 3 a.m., when the Japanese aircraft flew over Hill 102 and dropped its bomb, enemy troops, firing their weapons, tried to close in on the platoon holding Wally. They sprang six booby-traps, and that was all. Later that day a platoon of the 2/48th advanced up the Linda feature from the South-east and found five abandoned pill-boxes which were later blown in. This platoon and another which approached from the north found that the enemy was firmly in position on the summit

Later a Japanese order for the counter-attack on 10th June was captured: at 3 a.m. on that day all troops were to open fire, the riflemen firing 30 rounds, and then make a desperate attack; seven aircraft were to support the effort. A prisoner captured on 24th June said that he knew of the order, including the mention of 30 rounds, but in fact they had carried out the order “by the firing of 5 rounds only, due to the shortage of ammunition and the appearance of one aircraft only”.

In the 2/24th’s area the enemy were still holding Sandy and Beech 2, two rugged, jungle-covered bastions of the headquarters fortress. Aircraft struck at these on 11th June but their bombs fell 200 to 300 yards from the target. “D” Company had withdrawn from its positions on Roger during the air strike and the Japanese, aware of this, followed up; the Australians got back to Roger only just in time to re-occupy it and drive the enemy off. Captain Eldridge’s company attacked Beech 2, held by some 80 or 90 Japanese, from west and north but could make no progress. Probing on the 12th they found both features still occupied. On the 13th “A” Company found Sandy lightly held and took it, but “C” found Beech 2 still firmly defended. That night there were indications that the Japanese were withdrawing from the Fukukaku area; and early next day a patrol found Beech 2 unoccupied.

The battalions were now far below strength. In the 2/24th, for example, which had had the heaviest losses, only seven of the 12 rifle platoons were commanded by officers and there was a deficiency of 160 riflemen so that most companies were at half strength or less.

Forward of the 2/23rd bombardment was now concentrated on the Joyce feature. On 11th June 46 Liberators had made an accurate strike on targets in the Japanese headquarters area and then for 20 minutes the artillery and a troop of tanks lashed the Joyce feature. A platoon advanced close behind the artillery fire and killed five Japanese who were crouching in their pits, but a second platoon which passed through the first found

the enemy still in possession farther on. On 12th June a converging attack on Joyce by two platoons of the 2/23rd failed.

The 2/48th had continued the patrolling of the Linda feature on 11th and 12th June, and on the 13th, after bombardment by artillery, mortars and machine-guns, Lieutenant Johnstone’s47 platoon advanced from Monty and thrust to within 125 yards of the top, but came to a point where further advance was across open ground strewn with fallen trees, and eventually was withdrawn. Lieutenant Macdonald’s platoon from the north reached a point 60 yards from the top, but thence the approach was along a razor-back overlooked by the enemy’s fortress on the summit.

Thus on the 13th the enemy was resisting strongly. On the morning of the 14th, however, patrols from the 2/24th found that the enemy on their front had made a big withdrawal. The features named Paddy, Melon and Aunty were all abandoned and much equipment lay about. On the other hand a determined force covered the Essie Track, evidently the escape route. In the 2/23rd’s sector that morning a party of 87 Indonesians and 25 Chinese came forward with a white flag and a Chinese announced that the Japanese had abandoned the Fukukaku area. They bore a letter from the Japanese commander asking that they be treated well. The 2/23rd probed forward and soon was on the Joyce, Clarice and Hilda features. Eighteen stragglers were killed in the day.

The 2/48th found the Linda feature abandoned that day. On the 15th Nelly was found to be unoccupied; then Faith was taken – a big hill with twelve freshly-dug but empty positions. The platoon moved on from Faith to Dutch but there came under sharp fire from Japanese holding along a front of about 300 yards. Artillery harassed Dutch that night and next day it was found to be unoccupied.

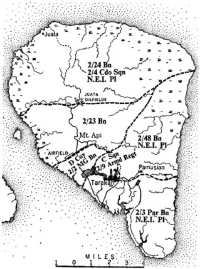

It was learnt soon afterwards that about 8th June Major Tokoi had ordered that the Japanese force would withdraw from the Fukukaku headquarters area in an orderly way with rearguards in position during the thinning out. The force would then split up into a number of independent groups and, within an allotted area, the commander of each would choose the ground on which he and his men would fight to the death. On 13th June Tokoi issued a written order stating that the withdrawal would begin at 4 a.m. on 14th June. The wounded, the translated order said, “will be dealt with so that they will demonstrate the honour of a true soldier, if possible (hara-kiri, suicide, etc.)”; when the withdrawal was complete the main force would take measures to establish liaison. Tokoi ordered that the positions which the Australians named Faith and Nelly were to be held for a week to protect the withdrawal and Essie ridge would be held until further orders. In the event Faith was held for only two days but the withdrawal was greatly helped by this stand.

By 14th June when the pursuit of the defeated garrison opened it was estimated that about 1,000 Japanese were still unaccounted for; a captured document indicated that there were probably 800 effectives.48

At this stage it was estimated that 1,153 had been killed or captured. It was learnt from documents and prisoners that every man had been given a month’s supply of rice and the remaining ammunition had been distributed.

Whitehead decided that as the enemy was on the run the pursuit should be pressed hard before they had time to establish themselves in their new positions and, in particular, that the Essie ridge should be attacked from all directions and the forces strengthened on the escape routes leading north from Essie. The forward troops of the 2/23rd and 2/24th were now advancing along the southern end of Essie ridge, and to the east the 2/48th was trying to force its way through the difficult country between Essie and Lanky.

On 14th June Lieutenant Cameron’s49 company of the 2/24th got astride the Essie Track, but the Japanese, determined to keep their escape route open, counter-attacked heavily. After a long fight the company, short of ammunition, withdrew from Essie ridge, having killed probably 23 Japanese. Next day Shattock’s and Cameron’s companies moved against Essie while Eldridge advanced to Short to cut the escape route to the north. Shattock, pushing swiftly down Essie ridge, ran into the heaviest fire his company had so far encountered on Tarakan, but they pressed on fast. Eldridge’s company covered 2,500 yards “over razor-backed ridges, through dense undergrowth and across a knee-deep swamp”; Shattock’s advanced 2,000 yards “over extremely difficult country” – “a meritorious effort”, wrote the diarist.

The mopping up of Fukukaku was completed on the 16th, when 46 dead had been counted. On Essie ridge the 2/24th had found two dismantled 75’s, 290 75-mm shells fused as grenades, and 87 other mines and grenades. The clashes with small groups of Japanese on this day and the next confirmed that the independent groups which had broken out of the Essie area were widely spread and were heading mainly north and east.

The role of the 2/48th, with a company of the 2/3rd Pioneers and a platoon of the NEI force under command, was now to prevent the enemy from escaping east from Essie. At dusk on the 16th a patrol reported having found the tracks of perhaps 100 Japanese who had moved east across the Lanky–Hopeful track and had leaped the main track to avoid leaving footprints on it. As a result of this indication of a main escape route Captain Johnson’s company was summoned from a picture show and hurriedly transported in LCMs to the Amal River on the east coast, and arrangements were made to ship Colonel Ainslie’s tactical headquarters and a second company to the Amal next morning.

When Ainslie and the second company arrived at the Amal he learnt that Johnson had advanced without incident to the Binalatung River and consequently took his group on to that point by water. There was no contact with the enemy in the area that day.

The main body of the 2/48th pursued the Japanese who were escaping eastward from Essie and on the 18th caught a few but there were indications that the large group had split up into smaller parties, at least some of which probably intended to escape to the mainland: on 18th June a patrol in an LCM, when off Cape Juata, saw clothing hanging out to dry on the shore, landed, and found a raft, six sets of clothing and other gear, but not the owners.

By 19th June patrols were radiating east, north and west in pursuit, and at a few points Japanese were standing firm. The 2/4th Commando Squadron was held at Hill 90 and Eldridge’s company of the 2/24th by a strong position west of Hill 90. Eldridge asked for artillery fire, and when he was asked how much said 2,000 rounds plus mortar fire. On the 20th after the artillery had fired 2,100 rounds and the mortars 600 the company took Hill 90 and found indications that about 200 Japanese had been driven out by the bombardment; soon afterwards patrols of the 2/4th Commando heard sounds of many Japanese moving north-east from this position.50

The capture of Hill 90 ended the last of organised resistance on Tarakan (wrote the diarist of the 2/24th). For 51 days the enemy had contested every yard of the approaches to Fukukaku and only on the virtual wiping out of his effective fighting troops did he cease resistance.

Farther north a patrol of the 2/24th clashed with a large enemy party on Snake and on 21st June the 2/24th attacked and took Snake after heavy artillery fire.

By 24th June 1,131 Japanese had been killed and 58 taken prisoner. It was estimated that about 250 armed effectives remained – an underestimate, as will be seen. For the mopping-up stage Whitehead now divided

the island into six areas of responsibility as shown in the accompanying sketch. The plan was to continue to pursue the surviving Japanese, not allowing them to establish themselves anywhere or to move any food and ammunition to secluded places. There was evidence that some Japanese were making rafts on the northern and eastern coasts and the units in those areas were ordered to press on fast and prevent these Japanese from escaping. The troops were instructed to avoid casualties. On 24th June one LCM began to patrol the narrow straits between Tarakan and the mainland, and another to patrol the waters off the east coast. In addition PT boats operated at night between Tarakan and the neighbouring islands.

The barges of the 2/3rd Pioneers were each manned by an officer and 11 other ranks, plus a crew provided by the American 593rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. These barge patrols killed 78 and took 54 prisoners; one patrol took 20 prisoners in one day.

A patrol under Lieutenant McLean51 sighted a craft [several miles north of Tarakan] with three naked Japs aboard. ... A burst was fired over their heads and signs made to them to surrender. They ignored the warning and continued paddling. On a second burst being fired the Jap in the centre of the craft picked up a grenade and beckoned his two companions over to him. All three knelt in the centre with their heads touching. The centre man then carefully tapped the grenade on the craft and held it under their heads. They remained in this attitude quite some time patiently waiting to join their ancestors, but the grenade was Japanese made. It failed to explode. They carefully replaced the grenade and the two paddlers calmly returned to their task. A third and final warning burst was fired, and, when they ignored it too, they were shot. A search of the craft revealed “no clothing, no food, no water and no loot”.52

The main immediate task was now to pursue the Japanese retreating towards the Maia and Selajong Rivers in the north. Patrols of the 2/24th Battalion which had the big northern sector were slowed down by the difficult country and by enemy rearguards. On 25th June two companies of the 2/23rd passed through the depleted 2/24th and thrust northward, one company along the line of the Maia River and the other along the Selajong. By the end of the month these companies had reached the coast having overcome many groups 30 to 40 strong and generally engaged in building rafts. Other raft builders were found by the 2/48th round the Amal and Binalatung Rivers.

The 2/3rd Pioneers, patrolling the country south of John’s Track found many parties on the high ground above Districts IV and VI, evidently survivors of a group pursued by the 2/48th from the Binalatung River. A company of the 2/23rd was sent into this area and in three days killed or captured 30; about 60 were killed or captured in the area south of John’s Track.

The advance to the Maia and Selajong Rivers caused the Japanese there to scatter, some south, some east and some west to Cape Juata where

they were intercepted by an NEI platoon. From 20th June to the end of July the LCM patrols and the crews of PT boats killed or captured 117 Japanese found on rafts or clinging to floating logs. Some of these rafts were substantial craft able to carry as many as ten men fully equipped, and as a rule they were camouflaged with bushes so that they resembled the little “floating islands” swept out to sea by flooded rivers. Although the gap between Tarakan and the adjoining islands was only about a mile the strong current made it almost impossible for a raft to cover the distance. Aircraft searched for rafts early each morning. The 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion manned several prahus which patrolled the coast and the estuaries and surprised many small parties of Japanese. Carrier pigeons were used for communication with this seaborne force. So strong was the determination of some Japanese to escape that they would fight back from their rafts with rifles and grenades against heavily armed craft.

After the first week of July it became evident that the surviving Japanese were becoming very short of food, and were stealthily moving back from the north to their old defence systems such as Fukukaku and Essie, to native villages, and even Australian camps in search of food. Soon about 20 Japanese were being killed each day in these areas. As hunger increased more Japanese surrendered, some bearing pamphlets dropped by Auster aircraft or left on the tracks by patrols.

On 30th July a patrol of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion led by Lieutenant Walter53 followed a very indistinct track over the Butch feature. Suddenly Walter found himself looking at a Japanese pointing a rifle at him from five yards away and struggling to pull the trigger. Walter fired one shot from the hip and killed the Japanese. A second Jap then ran out of a concealed bunker and Walter shot him on the run. It was found that the safety catch of the rifle of the first Japanese was still applied. A further patrol in the same area found three more Japanese and killed two. These Japanese had stored away enough food to last the five of them for at least two months. It consisted mainly of Australian canned foods including tins of boiled sweets from Australian Comforts Fund parcels that had recently arrived.

From 22nd June to 14th August Australian losses were 9 killed and 27 wounded, while 418 Japanese were killed and about 200 captured – about 350 more than were believed to be effective when this period opened. The prisoners were surprised at the gentleness with which they were treated and it was evident that one reason why they had been unwilling to surrender was a belief that they would be killed or tortured. But this was certainly not the main reason. In July 1945 19 Japanese prisoners on Morotai were asked a series of questions by American Intelligence men. All said that they considered that surrender was disgraceful; having been prisoners, they could never return to Japan, and they would like to settle in America, Australia or China. Seventeen said that they thought they would be killed if they surrendered and the same number said that

they did not believe the propaganda pamphlets that were dropped to them. Fifteen said that they thought Japan would not win the war, but 17 would not answer the question: “Do you think Japan will lose the war?” The interrogators thought that they all believed that Japan would fight to the last man and win a spiritual victory.

By July, although patrolling continued and a few Japanese were being killed or captured every day, a majority of the troops were engaged in re-training, camp improvements and other peaceful tasks. The 2/24th opened classes for NCOs on 9th July. On 14th July the army census aimed at assisting post-war rehabilitation was taken and “made troops think deeply of their post-war plans”. By 19th July the camp of the 2/24th was equipped with electric light, a beer garden with tables, chairs and, in the centre, a tiled floor, a concert stage, “162 signs”, and a reconstructed house as a headquarters. The 2/7th Field Regiment had an art club, with two instructors, and a mathematics class; and four men were at work on a regimental history. The 2/24th had been criticised for having brought to Tarakan band instruments, a piano, and a saw-milling plant. However, all was forgiven in this period when the battalion was supplying sawn timber far and wide, training mill workers, and providing band music.

Late in July began the departure to Australia for demobilisation of men with at least five years’ service, including at least two overseas. In a few weeks the 2/23rd, for example, sent away 7 officers including 3 company commanders, and 70 other ranks; the 2/7th Field Regiment soon lacked 13 officers and about one-third of those who remained had joined in July or August; the 2/24th had only 24 officers of whom 8 were newly-arrived reinforcements; the 2/48th had only 5 officers above the rank of lieutenant.

The Tarakan campaign was in some ways unique so far as Australian experience went and it produced some interesting problems.

Whitehead and his staff considered that too large an air force component had been included in the assault convoy, and after the operation Whitehead wrote that the air force component had had little or no experience of slimming to assault scales, and with its impedimenta caused serious difficulties in the allotment of the force to the available shipping, as well as greatly embarrassing the force, and especially the engineers, on landing. The army staff considered that all RAAF vehicles were too heavily laden and laden to some extent with stores not essential in the assault phase. This led to bogging of vehicles and increased the wear and tear on roads.

The size and complexity of the force, with its 13,000 troops and 5,000 men of the RAAF under command, threw a heavy burden on the small staff, which had functions more like those of a divisional than a brigade staff. Both the brigade major, Katekar,54 and the staff captain,

Geddes,55 were thoroughly experienced in those appointments, but their tasks in this operation resembled those usually performed by a GSO1 and AA & QMG

Before, during and after the landing the operations were dependent on the engineers to an unusual degree. The roads were mined and the engineers had to discover where the mines were. The ground was so boggy that roads could not be built away from the existing roadways and, particularly in the early days, repair and maintenance of roads crowded with heavy vehicles demanded great effort. There was no rock or gravel on the island and the only metal that could be obtained for road building came from the concrete foundations and floors of demolished buildings. The lack of hard standings resulted in vehicles being parked on the verge of roads where they broke the edges away.

The infantry had fought with great skill and determination. After the New Guinea campaign in 1943 and 1944 many of the older men had left the battalions as a result of wounds or illness and the ranks of the rifle companies had been filled up with young soldiers mainly aged about 19; and it was often these who led the advance as forward scouts and faced the enemy from forward section posts.

In such thickly-wooded country, with its steep slopes and sharp spurs, control of supporting weapons presented problems. However, complete confidence existed between the infantry leaders and the forward observation officers of the 2/7th Field Regiment. The gunners brought down remarkably accurate fire, often at the risk of tree bursts over the heads of the leading sections.

With accurate fire support from field guns, machine-guns, tanks and aircraft – and providing that ammunition was available – company commanders relied on blasting the enemy from their positions and on manoeuvring to the rear of their diggings rather than on head-on assault. These tactics took time to execute, specially in such tangled country. It was, however, easier than in New Guinea to pinpoint positions on the map because the Dutch had surveyed the island very accurately and placed many survey pegs along the tracks.

In the whole Australian force 14 officers and 211 others were killed and 40 officers and 629 others wounded.56 When fighting ceased 1,540 Japanese dead had been counted and 252 had surrendered; more than 300 surrendered after the cease fire.

The main object of the Tarakan operation was to establish an air base from which to support later operations in Borneo. The airfield proved so difficult to repair that it was not ready in time for the opening of the

operation against either Brunei Bay or Balikpapan, and fighter cover for those landings was provided from Tawitawi and from aircraft carriers. Thus events demonstrated that the role allotted to the Tarakan airfield, which was strongly defended, could be performed by the Tawitawi airfield, which, with Jolo Island, had been taken by American forces without opposition early in April. Another reason why, in retrospect, the choice of Tarakan as an objective seems unfortunate is that it was an island from which the defenders had no means of withdrawal, and, since they would not surrender, they sold their lives dearly. The Australian losses on Tarakan were nearly as high as those suffered by the 6th Australian Division in the conquest of Cyrenaica early in 1941.