Chapter 22: Balikpapan Area Secured

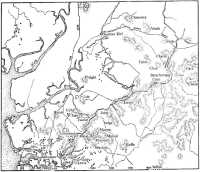

BY 9th July both airfields were firmly in Australian hands and the 7th Division had completed its main tasks. The two forward battalions of the Japanese force had been reduced to fragments. But, meanwhile, the 25th Brigade, facing the third battalion dug in round the Batuchampar area on the Milford Highway, had become heavily engaged; and, on the extreme left, units of the 18th Brigade had become involved in a novel river war. It was now known that Rear-Admiral Kamada’s headquarters were in the Batuchampar area.

On the afternoon of 4th July Brigadier Eather had held a conference at which he ordered his unit commanders to continue the northward advance on a three-battalion front. He instructed Lieut-Colonel R. H. Marson of the 2/25th to take over Nurse and Nail from the 2/31st, the object being to “seal off” the area from Orr’s Junction westward to the coast and clear the country thus enclosed. All three battalions were then “to move forward slowly making utmost use of supporting arms”.1 These included those of the 2/4th Field Regiment, of a company of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion, some anti-tank guns, and three troops of tanks. On the right the 2/33rd had occupied Letter and Lewis on the 4th, and on the 5th pressed on against dwindling opposition to Mackay, Marshall, Mutual and Margin.

After the 2/25th had relieved the 2/31st (Lieut-Colonel Robson) on Nail and Nurse the forward companies of the 2/31st took up defensive positions on Letter and Lewis. Then Laverton was occupied, and, after a bombardment, Liverpool was taken. Heavy fire was now coming from Metal, and about 1 p.m. Robson’s command post on Lodge was under heavy fire and his adjutant (Captain De Daunton2) and Intelligence officer (Lieutenant B. E. D. Robertson) were wounded and the wireless set shot to pieces. Robertson continued to pass information back to brigade by telephone until carried back under fire by Corporal Moorhouse,3 who then went out again and brought in the telephone.

When it occupied its new positions on 5th July the 2/33rd was under fire from Muffle, to the east, and, like the 2/31st, from Metal. That night mortars lobbed 650 bombs on to Metal and next morning Captain Balfour-Ogilvy’s4 company took that hill, but a platoon of another company that moved towards Muffle was held up by enemy fire; in the afternoon, however, Muffle too was taken. From midday onwards Japanese guns on Joint fired on the battalion’s positions. At 3.55 p.m. shells hit

the command post, killed the signals officer, Lieutenant Wallace,5 and wounded the commander of the 2/33rd, Lieut-Colonel T. R. W. Cotton, and others. Cotton was taken to the dressing station and G. E. Lyon, Eather’s brigade major, who had just arrived at the post, assumed command. A company probed forward towards Judge but came under heavy fire and withdrew to Marshall. On 6th July the 2/25th pressed on, took over Liverpool and occupied Huon.

Eather’s policy in this situation – the enemy resisting vigorously on naturally-strong ridges – was to use the supporting arms to the maximum and probe forward with patrols. Even so the Japanese were exacting a high price. On 5th July the brigade had lost 9 killed and 13 wounded; 31 Japanese dead were counted and 2 prisoners taken. On the 6th the brigade lost 2 killed and 32 wounded; 20 Japanese dead were counted and 3 prisoners taken.

On the morning of 7th July Lieut-Colonel Marson ordered Major C. S. Andrew’s company, on Huon, to take Cult with one platoon, and if this succeeded to build up to full company strength. Lieutenant Egan6 led

his platoon out, formed a firm base on Cult without meeting opposition, and sent a section to Jam. It came under fire from two pill-boxes and, ably led by Lance-Corporal Svenson,7 wiped one out but then was forced back. At this stage Andrew and an artillery party arrived on Cult with the remainder of the company. It was now found that a copse between Cult and Jam was strongly held; it was kept quiet by machine-gun fire from Liverpool.

Next day the copse was shelled but patrols probing forward met sharp fire. Finally, after a very heavy concentration of fire by field guns, antitank guns and machine-guns, a patrol on the 9th found the copse and Jam unoccupied. On Jam and in the copse 46 enemy dead were found and there were signs that others had been buried. The 2/25th lost 3 killed and 10 wounded of whom 6 remained on duty.

Almost every night small parties of Japanese raided the Australian positions. For example, on the night of the 7th the 2/31st killed six raiders, and the headquarters of the 2/33rd was attacked by about 16 armed with rifles, machine-guns, spears and grenades. These killed the Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Melville,8 and wounded 3; 3 Japanese officers and 9 men were killed. Eather now sent the 2/6th Commando Squadron (Captain G. C. Blainey) out on the left flank into the hills overlooking the Sumber River. Here on the 8th they occupied Job and next day found Freight and other hills unoccupied: it was evident that the Japanese had abandoned most of the garden area along Phillipson’s Road.

That day after heavy bombardment the 2/33rd (now commanded by Major Bennett9) found Justice abandoned, and a company pressed on to Joint where 16 enemy dead and two damaged field guns were found; and to Judge. On the right flank two platoons under Lieutenants Moore10 and Richards11 made a converging attack on Muffle, long an isolated yet stubborn enemy outpost well to the south of their main positions, and took it; 15 Japanese dead were counted there. By the end of the day it was evident that the enemy rearguard had withdrawn about three miles along the highway to the Batuchampar area.

The effectiveness of the artillery fire – obviously a main cause of the withdrawal – was revealed by examination of the ridges that the Australians occupied on the 9th: shell holes on Muffle, Joint, Justice and Jam were only about five yards apart and many bunkers had been hit; the two field guns found on Joint had received direct hits.

For the first five days the 25th Brigade had been fighting in fairly open country in which it was able to use all available supporting weapons,

but from the 9th onwards it was fighting in thick bush. The advance astride the Milford Highway to Batuchampar was allotted to the 2/31st Battalion. On the afternoon of the 9th Colonel Robson gave orders that Major C. W. Hyndman’s company would be forward on the right, its objective being Junior, and Major H. F. Hayes’ company on the left, its objective being a road bend due north of Junior. These were occupied without loss by 5 p.m. and at 6.25 Robson decided to move the whole battalion forward. Soon afterwards Lieutenant Lewis’12 platoon was moving along the highway when five 500-kilo bombs lying in the open along the road were exploded around the Australians by remote control killing 3 and leaving 17 others dazed by the blast; the Japanese then opened fire with machine-guns. Corporal Mullins,13 commanding one section, was thrown 15 feet off the road but returned, carried out a wounded man, withdrew the remainder of the bewildered men, and then went back and carried out another wounded man. That night the 2/31st formed a perimeter in this area and a patrol found the enemy dug in forward of Cello.

On the morning of the 10th Captain Lewington’s14 company secured a foothold in the buildings at Cello about 300 yards from the enemy. Robson was moving forward with a reconnaissance party when a group of depth-charges was exploded by remote control; Lewington suffered shock and the artillery observer was wounded. By 11.30, however, Cello had been secured and Japanese were seen at some fallen timber beyond, which was mortared and bombarded by the artillery.

At 12.10 p.m. Robson ordered Hayes’ company to attack through the company on Cello and secure the fallen-timber area. In support was a troop of three tanks including one Frog. From 1.45 until 2.30 the artillery and 4.2-inch and 3-inch mortars fired on the area, clearing all the light timber, and the tanks, which had taken up hull-down positions on the road, fired into enemy strongpoints.

Hayes’ company attacked at 2.30 with one platoon and the Frog forward. Two bunkers were soon silenced. Warrant-Officer Willson15 advanced with one section and knocked out several Japanese machine-gun posts. He was wounded but carried on, capturing a 40-mm gun, and in 15 minutes the foremost enemy position had been taken. Twenty-five Japanese were killed and the captured weapons included one 75-mm gun, nine light anti-aircraft guns and two anti-tank guns. A patrol then probed forward and reported one machine-gun post on Coke.

Coke was a steep knoll on the right of the road carrying a tall tree every few yards and with tangled secondary growth among which lay a number of big logs 3 and 4 feet in diameter, evidently felled by timber

getters. Robson, who considered that the shell of the enemy’s resistance had been broken, now gave a warning order to Hyndman’s company to take Coke and thrust along the road with all speed. The artillery and mortars began firing on the objective at 3 p.m. and the tanks fired from a road cutting 400 yards from the foot of Coke. There was no reply from the enemy. Lieutenant Carroll’s16 platoon attacked at 5 p.m. with three tanks (of the 2/1st Armoured Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron) and with two engineers out ahead to deal with mines. The tanks (in line ahead and about 30 yards apart) and the infantry had advanced about 100 yards without opposition when the enemy opened intense fire from several positions on Coke and also from some on the left of the road. The fire from the left killed Major Ryrie of the tanks and a signaller who were forward in the road cutting, and wounded Major K. S. Hall, second-in-command of the 2/31st, who, with Robson, was also watching from the cutting. The forward platoon lost heavily and was halted, one man, Lance-Corporal Rabjohns,17 lying within five yards of the enemy and others within 20 yards. The posts, which numbered about seven, were dug under the big logs, which gave good overhead cover, or at the foot of big trees.

All this had happened in an instant. When the Japanese opened fire the men of Lieutenant Kelly’s18 platoon, which was to leap-frog over Carroll’s when it had passed Coke, were leaning against the bank of the cutting just behind Robson, Ryrie and the others Immediately Robson turned and shouted: “Nine platoon, get up there on the right!”

We had a grandstand view and needed no orders by the platoon commander (wrote one of them later). [Corporal Ottrey’s19] section crossed the road first and ran into the fire that killed Ryrie. It was so quickly done that I am sure it was the same gun and the same magazine.

Ottrey and two others were hit. Lance-Corporal Cooper,20 a former lance-sergeant in the 1st Parachute Battalion, who had heard Kelly give a shout and thought he too had been hit, collected five men, and they pressed on to the logs where Cooper grenaded two Japanese who appeared on the right. There they threw off their haversacks and fixed bayonets. Kelly now joined this group and then arrived a second platoon which Robson had sent forward. While part of the two platoons faced right Cooper sent two men up the hill in search of the machine-gun which had hit so many men on the road. The leading scout, Private Blunden,21 fell. Cooper ran up to him and found him at the feet of a Japanese. Cooper promptly bayoneted this man, picked up Blunden’s Owen gun

and shot four more. Cooper held on here while the men farther down the hill beat off Japanese who were coming in from the right.

On the road, when the forward tank – the Frog – had exhausted its fuel, it went back carrying wounded, and another tank replaced it. Private Douglass,22 a man of 39 who was normally a storeman at battalion headquarters, moved down the road under heavy fire and helped out two wounded men, then returned on a tank and remained attending to wounded men who lay in the open. The tanks could not turn on the road, and when the leading one withdrew the others had to precede it. About ten Japanese were now advancing round the lower slopes of Coke towards the wounded, but Douglass engaged them with Rabjohns’ Owen gun and held them off until the wounded men had been taken out by the tank.

Corporal Murdock’s23 tank now gave supporting fire until its Besa gun was damaged and could fire only single shots and all high-explosive ammunition for its main gun was exhausted. At 5.50 Murdock was ordered to withdraw and to pass on an order to withdraw to the infantry. Murdock dismounted under fire and did this; he then directed the placing of four wounded on his tank and brought them out. Two of his crew had been wounded.

Robson’s order to withdraw was passed forward from man to man. The forward infantry sections came out under spasmodic fire, helping with the wounded, and then the battalion took up a defensive position astride the road for the night. The Japanese infiltrated among the Australian posts that night and killed one man. On the 10th, 18 had been killed and 23 wounded round Coke, all but 3 killed and 9 wounded being in Hyndman’s company; at the end of the day 11 of the dead had not yet been recovered.

On the left of the 25th Brigade the 2/6th Commando Squadron had been ordered by Brigadier Eather to patrol to Sumber Kiri. On the 10th a patrol under Lance-Sergeant J. McA. Brammer encountered about 60 Japanese north-east of the village. Lieutenant W. Taylor hastened forward with another section; they attacked and drove out the Japanese who left 8 dead; two Australians were killed.

There was a lull after the hard fight on Coke. The Japanese facing the 2/31st were well dug in and well-armed. Next day Eather ordered the 2/25th to relieve the 2/31st. On the 12th a patrol of the 2/6th Squadron worked round through the bush to a point on Charm whence it overlooked the highway about two miles behind the forward positions. Here the men watched parties of about 30 Japanese carrying supplies and stretchers forward. A party of about 20 approached the Australians’ observation post. The Australians withdrew and set an ambush which killed six; the others made off. The main body of the squadron on the 13th and 14th moved to Cloncurry and Abash. In the course of this move

one troop was ambushed, two bombs were detonated in its path, and Lieutenant Linklater24 and four others were killed or mortally wounded. An NEI platoon that had also been patrolling on this flank was at the Wain pumping station and probing northward.

After much patrolling on both sides of the highway, Eather, on the afternoon of 14th July, ordered the 2/25th to send a company-wide on each flank: one to Cart and the other to Calm, both of which had been visited by patrols and found unoccupied. The right-hand company reached Cocoa about a mile south of Cart by dusk; the left moved through Calm to Chair. On the 15th Lieut-Colonel Marson ordered the company on the right (Captain B. G. C. Walker) to advance to Cart while another company and his own headquarters moved on to Calm. In this situation the battalion would dominate the highway from both east and west.

The enemy reacted strongly on the night of the 15th. In heavy rain from 40 to 50 raided Calm but were driven off. In this fight which lasted all night Lance-Corporal Grigg25 moved forward alone to a log that the raiders were using as cover and threw grenades over the log at the Japanese. He was believed to have killed most of the 13 Japanese who were found dead there. The Japanese raiders moved very quietly: one of them wounded an Australian with a sword. When daylight came the Japanese withdrew about 75 yards. Marson sent up three platoons under Major Andrew at 9 o’clock next morning and these took forward ammunition, carried out the wounded and drove the Japanese away. On the 16th an enemy force occupied Cocoa, temporarily cutting the line of communication of Walker’s company on Cart, and that night raiding parties attacked the headquarters of the 2/33rd near Cello causing five casualties, and attacked the NEI platoon at Wain pumping station, causing it to fall back some distance.

On the 17th a company of the 2/25th occupied Charm hard by the highway and a company of the 2/33rd took over on Cart. That evening Eather gave orders for a decisive movement: the 2/6th Squadron, which was carrying out ambushes throughout its area – it killed 23 Japanese on the 16th and 17th – was to patrol in strength to the highway near the junction with Pope’s Track; the 2/31st was to relieve the 2/33rd astride the highway; the 2/25th was to cut the highway at Charm; the 2/33rd was to cut the track running east from the Pope’s Track junction along the valley north of Cart.

That night (the 17th–18th), which was dark and rainy, the Japanese “reacted violently to the gradual encirclement” and before dawn attacked the two companies of the 2/25th then on Charm and the headquarters of the 2/33rd. At Charm the enemy maintained constant pressure against the whole perimeter until a counter-attack drove them off at 8.30 a.m. Here three Australians and 53 Japanese were killed, many probably by

defensive fire brought down by the artillery. On the 19th and 20th the forward companies continued to probe on both sides of the road. There was a sharp fight on Charm on the 20th. Lieutenant Raward26 and 12 men of Captain R. W. P. Dodd’s company went out to destroy a Japanese strongpoint which was found to be far stronger than expected. Raward divided his party into two, attacked and drove the enemy out. Corporal Ford,27 operating a flame-thrower with much daring, was largely responsible for the success. That evening a patrol of the same company under Lieutenant McCosker28 ambushed a carrying party of 20 moving south along the highway and killed about 17. Round Charm the 2/25th killed 95 Japanese and lost 4 killed and 12 wounded. The 2/33rd on the right was now round Cart, the 2/25th on Calm, Chair, Charm and Abide.

The 2/31st was astride the highway South-South-east of Chair. The tanks moving with it along the highway had been halted by a big crater in the road. On the afternoon of the 19th, after artillery bombardment, Lewington’s company advanced and attacked round the right flank, and a tank with bridging equipment moved forward to span the crater in the road and let four other tanks through. By 2 p.m. the bridge was ready and the leading tank moved up to engage the enemy; by 3 p.m. the company had its objectives, and had taken four heavy mortars. One of the tanks was temporarily disabled by a contact mine which it hit just beyond the bridge.

Patrolling continued on the morning of the 21st: the enemy was still in the same positions on both sides of the highway. In the evening, however, it was found that the forward positions had been vacated but were covered by fire from a little farther back. Patrols counted 26 dead in the abandoned posts. That night there were loud explosions round Charm and elsewhere, and next morning the enemy had gone. Against little opposition patrols pushed forward to Pope’s Track and beyond.29

General Milford decided that, having reached the line of Pope’s Track, he had his objectives and no good purpose would be served by continuing to thrust against the enemy rearguards. General Morshead agreed and Milford instructed Eather to stay put and only patrol forward of the line he then held.30

It was proving impossible to land the necessary tonnage of stores over the open beaches because of the sea swell and it was therefore essential to use the port, but when General Milford asked Rear-Admiral Noble to do this Noble stated firmly that he would not send even a destroyer into the bay unless he had a guarantee that the western side of it was

5th July-6th August

clear of Japanese guns. Thus Milford had no alternative to sending a force across the bay. It was an interesting example of a course of aggressive action being forced on a commander by the administrative requirements.

On 4th July, therefore, Milford had given the 18th Brigade the task of landing a battalion on the western shores of Balikpapan Bay to ensure that the enemy could not interfere with the working of the port from that direction, and incidentally to assist NICA to give aid to the natives.

Brigadier Chilton gave these tasks to the 2/9th Battalion, with, under its command, a troop of the 2/7th Cavalry (Commando) Regiment, a troop of tanks, a troop of field guns, one of heavy mortars, and other detachments. This force was to land at Penadjam from LVTs and LCMs on 5th July.

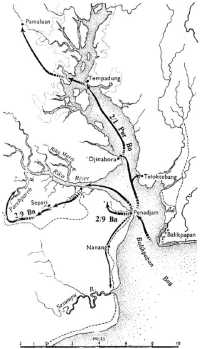

The LVTs containing the two leading companies of the 2/9th moved off at 12.10 p.m. Milford regarded this as a ticklish operation and watched, with some anxiety, from the heights where the cracking plant stood. Naval vessels and field artillery bombarded the objective and at 1.35 the first troops landed without opposition. By 2.15 the whole battalion was ashore. All the tanks bogged as they landed from their LCMs. One company patrolled southward and found no enemy. There was random enemy artillery fire from a point three miles west of Penadjam at 3.45, but the 2/4th Field Regiment, firing across the bay, quickly silenced the gun. A second company patrolled northward and by 6.15 had reached the top of the hill to the north-west having killed one Japanese and taken a 5-inch gun intact. Five more guns were later found in this area. Just outside Penadjam five Indonesians were discovered dead with their hands tied behind their backs.

Next day at dawn a patrol went south to Nanang village and on to the Sesumpu River which it reached by 2 p.m. No Japanese were seen but natives reported that some had passed through the previous day. The other companies and the commando troop made local patrols.

One commando patrol was ambushed near a village not far from the mouth of the Riko River and lost two men killed. A platoon of the 2/9th Battalion reinforced the commando troop and after some days of patrolling it was found that the enemy was dug in in the Separi area. On 12th July, after further probing, the enemy withdrew from this position. On 7th July a platoon under Lieutenant Gamble31 established an artillery observation post on high ground with a view of the mouth of the Riko River.

Patrols of the 2/3rd Commando Squadron found enemy positions about four miles west-north-west of Penadjam. At the first position a patrol killed five; at the second 23, it was estimated, before enemy mortar and machine-gun fire forced the patrol of 12 to withdraw.

Captain D. C. J. Scott of the 2/9th Battalion with two platoons and mortars landed unopposed at Djinabora on the afternoon of 8th July; one platoon was left there to examine tracks in the neighbourhood; it found no Japanese.

That night Chilton ordered Lieut-Colonel A. J. Lee, the commander of the 2/9th, to land troops at Teloktebang on the eastern shore. These landed on the 9th but found no enemy. On the 11th Chilton ordered the 2/9th to maintain a platoon base at Teloktebang and patrol northward, to patrol the north bank of the Riko River to the Riko Matih and northwest along the high ground, to harass the enemy on the south bank of the Riko, and to continue patrols to the Sesumpu River and eliminate Japanese stragglers.

On 15th July natives reported that there were 30 Japanese at Separi, and patrols set out through very difficult country to find them, but when they arrived the Japanese had gone. A patrol under Lance-Corporal McKinlay32 reported a Japanese motor vessel of 300 tons some miles up the Riko and a platoon was sent out to place a standing patrol to watch it. They found the vessel unoccupied and boarded it. During the night a big launch appeared towing a motor boat and prahu. The patrol opened fire from the motor vessel and the launch was set on fire and sank. Five Japanese were taken prisoner; the motor vessel was sailed down to the mouth of the Riko.

This kind of patrolling, by land and water, continued. A patrol led by Lieutenant Frood33 voyaged by LCM and prahu along the Parehpareh, and established a base to the west whence it probed westward to cut the enemy’s line of communication. It found about 50 Japanese who were withdrawing northward. This was too large a force to be attacked in such circumstances and the patrol was withdrawn.

General Milford decided on 16th July to place a reinforced company of Lieut-Colonel A. A. Buckley’s 2/1st Pioneer Battalion, which had mainly been employed round the beach-head, under the command of the 18th Brigade to protect Balikpapan harbour against possible enemy attacks from the north. Milford did not know what the Japanese were doing at the top end of the bay, but the 2/9th had intercepted several small craft trying to make their way there. There was now much shipping in the port, the naval covering force had departed, and it was conceivable that the Japanese, with small craft, might make a night raid on the port.

Thus Captain Morahan’s34 company with a section of the 2/4th Field Regiment and other detachments, and with two LCMs, went to Djinabora and began patrolling. Its tasks included preventing enemy parties moving south to the bay and possibly engaging enemy positions to the north. On 21st July this force was enlarged to include two companies of the Pioneer battalion with detachments of heavy weapons under command and a troop of the 2/4th Field Regiment and a searchlight in support. This group was named Buckforce and was at first commanded by Major Coleman.35 It was to establish a coast-defence position and patrol base in the Tempadung area, prevent Japanese from moving by sea to Balik-papan Bay, patrol and establish contact with the enemy, operate “such water patrols as type of craft available permits” and seek more forward patrol bases.

Buckforce patrolled widely in the next few days. Some Japanese were encountered. On 26th July the Australian frigate Gascoyne, placed at the disposal of Buckforce for the day, shelled Tempadung and Pamaluan, a village about 7 miles to the north-west. The latter was occupied early on the 28th; the Japanese had evidently departed a few hours before. Next day a patrol fired on a group of eight Japanese and killed three. Thick jungle and mangroves made both patrolling and the landing of water craft difficult. On 30th July two platoons under Lieutenant Blamey36 probed east and north. One platoon encountered a bunker position and a man was killed. Artillery fire silenced this position and both platoons attacked, took three bunkers and killed seven Japanese. They dug in and at 3 a.m. on 31st July 30 Japanese attacked but were driven off by artillery and small arms fire.

Patrols were sent out on the morning of 1st August and found many signs of enemy movement but saw no Japanese. On the 2nd, however, at 8.30 p.m. a Japanese patrol attacked Captain Kitching’s37 company but was driven off leaving six dead. Soon afterwards three Japanese were killed by a booby-trap. Buckforce had now killed 30, and taken one prisoner. Lieut-Colonel Buckley took command of the force on 3rd

August and the Japanese positions were bombarded by the guns of a whole battery, their fire being directed with the help of an observer in an Auster aircraft.

By 6th August the whole of the battalion was concentrated in the Tempadung area. Patrolling continued against parties of Japanese who were still disciplined and aggressive. On the 6th observers in an Auster guided a patrol to a group of 63 Indian prisoners, who were picked up by an LCM next day. These had been captured in Sarawak early in 1942. The last clashes with the enemy in this area occurred on 9th August when a patrol under Lieutenant Morrow38 killed three Japanese, and Captain Williams’39 company, patrolling towards the Milford Highway, also killed three.

After the big withdrawal of the Japanese from the Batuchampar stronghold the 25th Brigade stayed where it was but patrolled extensively every day. On 25th July the 2/7th Cavalry (Commando) Regiment with two squadrons took over the forward positions astride the highway, and thenceforward patrolled northward; it had fairly frequent patrol clashes and set many ambushes. The last clash occurred here on 14th August when a deep patrol of the 2/25th Battalion set an ambush on the highway; 12 Japanese walked into it and 9 were killed.

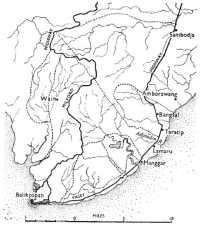

While the 2/14th Battalion was overcoming the enemy stronghold above Manggar the 2/16th had been patrolling deep into the tangle of hills north-east of Balikpapan. From 8th July onwards such patrolling occupied only a few sub-units each day and much of the effort of this battalion (as of others, similarly employed) went into improving its camp, making fish traps, and engaging in other profitable and pleasant occupations.

After the Japanese positions above Manggar had been taken the 2/14th Battalion was out of contact with the enemy for a time. Hundreds of natives were then streaming into the NICA compounds. They said that about 150 Japanese were on Bale, 2,000 yards to the north. On 10th July the 2/27th took over the left flank at Manggar, freeing the 2/14th to probe towards Sambodja. Patrols from Major C. A. W. Sims’ company of the 2/27th clashed with parties of Japanese that day on Band and Frost, south of Bale; 3 Australians were killed and 9 Japanese. Lieutenant Dempsey40 of the 2/14th led a platoon along the Vasey Highway to the Adjiraden River, made a patrol base there, and thence probed to Taratip without finding any Japanese.

On the 11th the 2/27th moved through and took over the base at the Adjiraden River and next day its command group and two companies were established at Lamaru. Natives said that there were no Japanese

even in Sambodja, and on 14th July a patrol confirmed this, and an NEI patrol found Amborawang unoccupied. On the 17th Lieut-Colonel K. S. Picken of the 2/27th moved his command post forward to Amborawang and had one company there and one at Bangsal on the highway. Thence on 18th July Picken sent two companies, 438 strong, into Sambodja. A patrol north along the pipeline encountered five stray Japanese and killed two.

A patrol consisting of Captain Crafter’s41 company of the 2/27th less one platoon moved due west across country to the Milford Highway on the 18th. They reached a point about two miles and a half from the highway, and thence Crafter and a small party made their way forward and, having had to cut a track through thick jungle for the final 2,000 yards, reached the road at 5 p.m. They heard Japanese moving along the road and then were themselves seen and pursued. They evaded the enemy and rejoined the company, which moved back to Amborawang next day. That day (the 19th) the battalion was ordered to return to the Adjiraden and relieve the 2/14th in the country north of the airfield. It moved back in vehicles next day.

The Japanese appeared to be gradually withdrawing from the cluster of hills round Bale. On 14th July a platoon under Lieutenant Gugger42 encountered a party of about 20 Japanese with two machine-guns on Bale. Gugger decided to withdraw under cover of smoke to allow the artillery to fire. Smoke grenades could not be fired because of the density of the bush, so Gugger crawled forward to where the screen was needed and lit the grenades with a match. The Japanese drew back farther into the hills and on 17th July the ridges north of the Bale group were found to be unoccupied except by one party, and it withdrew on the 18th.

In the next four weeks deep patrolling continued in the area north of Manggar, and there were occasional clashes. On 1st August information arrived that about 100 Japanese were moving towards Sambodja. Brigadier Dougherty ordered Lieut-Colonel F. H. Sublet to reinforce

Sambodja and Amborawang, and by 3rd August most of the 2/16th was concentrated at Sambodja. Long-range patrols were sent out, some remaining away five or six days, but only stragglers were found.

The 2/14th moved forward to protect the line of communication of the 2/16th and particularly to deal with ambush parties along the Vasey Highway. On 9th August Lieutenant Backhouse43 and 20 men of the 2/14th set out on a 48-hour patrol to examine the tracks between the two forward companies. About four hours out the leading scout saw and fired on four Japanese. Backhouse put one section on the track while he and the two other sections attacked on the right and soon found themselves close behind the enemy. They had been unobserved but could now see the Japanese who appeared to be “in a large-sized panic, racing from hole to hole”. “This situation,” says the patrol report, “was not desirable,” so the flanking group returned and a fresh attack was launched. This time two sections attacked on the left while the third held the track and watched the line of withdrawal. In close fighting seven Japanese were killed and opposition ceased. Three Australians were wounded, one mortally. It was the battalion’s last engagement.

As usual the men soon found interesting employment.

An officer of this staff is building a 15-foot sailing boat just outside his tent (wrote a visitor to the 21st Brigade in mid-August). Next door another is cleaning and polishing a set of crocodile’s teeth. On the river are several sailing boats made from aircraft belly-tanks. Surf boards are in use in the 2/16th Bn area farther along the beach. There is plenty of sawn timber to be collected in the ruins of Balikpapan and bigger and better huts are going up every day.

The number of Japanese dead seen and counted in the Balikpapan operation was 1,783. It was estimated that 249 others had also been killed; 63 were captured. A total of 229 Australians were killed or died of wounds and 634 were wounded. The heaviest losses were suffered by the 25th Brigade in its advance inland along the Milford Highway, and particularly by the 2/31st Battalion.44

In September Milford received a copy of the report on the Oboe Two operation by the AOC RAAF Command, Air Vice-Marshal Bostock. Bostock offered some criticism of the army on some interesting points

of principle, and Milford wrote replies to this criticism into his war diary. For instance, Bostock wrote: “The local army commander, during this operation, was particularly prone to attempt to dictate the manner in which air support was to be applied. He wished to nominate classes of aircraft, types and weights of bombs and methods of attack to be employed to achieve the results he specified. This attitude is to be deprecated. It is just as illogical for a local army commander to presume to interfere with professional and technical air force aspects as it would be for him to attempt to dictate to a supporting naval force commander the classes of ships, types of guns and dispositions of naval vessels detailed to afford him support with naval bombardment.”

Milford replied: “In many instances the army commander has a vital interest in the method of attack to be employed since the lives of his troops may be endangered. For targets in proximity to army troops the army commander alone knows the detailed dispositions and intention of his troops and can determine methods of attack which are safe. For distant targets the same considerations do not apply but [the] paragraph ... does not differentiate.”

Bostock also complained that “Army officers responsible for loading the First TAF units were not always sympathetic to RAAF requirements ... working with a new division, some rawness was inevitable”.

Milford replied: “The allotment to ships of every man, vehicle and store of the whole force is an army responsibility. Since shipping is never available to meet all demands (and every service and unit considers its demands essential) the difficulties of a satisfactory solution are very great. As an example of army cuts, no supporting arms whatever and practically no equipment and stores for the reserve brigade could be included in the assault lift.

“The RAAF, accustomed to a high standard of comfort, and not faced by the problem of fitting masses of vehicles and stores to a minimum of ships, regards as unsympathetic a reduction of air force equipment to a scale which on army standards is lavish.”

Indeed, rightly or wrongly, in this and other amphibious operations, army officers considered the equipment required by the air force in the early stages excessively elaborate, and the discipline of air force ground staff capable of improvement.

The Balikpapan operation – the largest amphibious attack carried out by Australian troops – succeeded fairly swiftly. The attackers possessed the support of powerful weapons: aircraft using bombs, napalm and guns; naval guns; tanks, including flame-throwers; manhandled flame-throwers.45 The Japanese, who were in well-prepared positions and well equipped with guns and mortars, resisted with their usual fortitude, and paid more than seven lives for each Australian life they took. Once again they

demonstrated how a force of resolute men well dug in could delay a stronger force far more formidably armed.

The immediate objectives in Borneo were to establish bases and reoccupy oilfields; the long-range objective had originally been to advance westward to Java. If the attack on Java had been carried out it would have been in progress at a time when American forces were committed to an advance northward to Japan proper, and the British-Indian forces to an advance southward against Singapore. In retrospect the wisdom of embarking upon this third thrust – westward against Japanese forces isolated in the Indies – seems doubtful. Strategically the only gain would have been to the Japanese whose isolated and otherwise idle forces would be given employment; it would have been proper to place this third front on a low priority for equipment, and not improbable that it would have been plagued by shortages of men, ships and aircraft.

One result of a complex of decisions, some contradictory and some illogical, was that, in 1945, while I Australian Corps, well equipped and with powerful air and naval support, was preparing for or was fighting battles of doubtful value in Borneo, an Australian corps in Bougainville and an Australian division in New Guinea were fighting long and bitter campaigns (whose value also was doubted) in which they were short of air and naval support, and suffered such a poverty of ships and landing craft that, as a rule, the best they could do was to put ashore a company or two at a time on a hostile shore. The Japanese on the other hand could reflect with satisfaction that in this period their four depleted divisions isolated round Wewak and on Bougainville had kept three Australian divisions strenuously employed, and in Borneo three hotchpotch forces had engaged two more Australians divisions, though only briefly.