Chapter 9: Alarums and Excursions, 1940

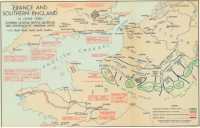

(See Map 4 and Sketch 1)

The Role and Problems of the Canadian Army Overseas

The tasks of the Canadian field army developed in a manner which no one foresaw at the outset; for no one foresaw the course of the war. Inevitably, Canadian thinking was largely dominated by the experience of 1914–18, the more so as the beginning of hostilities in 1939 found a British army again crossing the Channel to cooperate with the French forces on French soil. It seemed clear that the 1st Canadian Division, and such other Canadian formations as might follow it to Britain, would in due time go to France and serve with the British armies there.

This was not the course which events followed. In a lightning campaign in May and June 1940, the Germans smashed the French armies and drove the British from the Continent before more than a fraction of the available Canadian force had reached France and before any of it had got into action. Thereafter, the Canadians found themselves part of the garrison of the British citadel, a beleaguered garrison which nevertheless maintained an active defence and constantly directed sorties against the besiegers. This situation raised a whole series of unexpected problems.

As it turned out, the Canadian force – a volunteer army recruited in the expectation of early action – spent forty-two months in the United Kingdom, from the arrival of the 1st Division in 1939, before even a portion of it took part in a protracted campaign. During this period the Canadians had few active tasks, and only one major contact with the enemy – the Dieppe raid of 19 August 1942. These few tasks and operations, including the part which the Canadian force played in the protection of the United Kingdom, are the theme of this chapter and those that follow. Except for the Dieppe operation they are not treated in great detail.

Authority to Commit Canadian Forces to Operations

A topic of basic importance is the question of the extent of the authority possessed by the senior Canadian commander overseas to commit his force,

or portions of it, to operations without reference to his superiors in Ottawa. This involves a brief preliminary excursion into the constitutional background.

The legal relationship between the military forces of Canada and those of other countries of the Commonwealth was very largely governed by a group of statutes passed by the various Commonwealth parliaments half a dozen years before war broke out. Most important for our purposes are those enacted by the parliaments of Canada and of the United Kingdom, known as “The Visiting Forces (British Commonwealth) Acts, 1933”. The content of the British and Canadian statutes is, for practical purposes, identical.

The most important sections of the Canadian statute1 may be reproduced here:

(4) When a home force and another force* to which this section applies are serving together, whether alone or not:–

(a) any member of the other force shall be treated and shall have over members of the home force the like powers of command as if he were a member of the home force of relative rank; and

(b) if the forces are acting in combination, any officer of the other force appointed by His Majesty, or in accordance with regulations made by or by authority of His Majesty, to command the combined force, or any part thereof, shall be treated and shall have over members of the home force the like powers of command and punishment, and may be invested with the like authority to convene, and confirm the findings and sentences of, courts martial as if he were an officer of the home force of relative rank and holding the same command.

(5) For the purposes of this section, forces shall be deemed to be serving together or acting in combination if and only if they are declared to be so serving or so acting by order of the Governor in Council; and the relative rank of members of the home forces and of the other forces shall be such as may be prescribed by regulations made by His Majesty.”

It will be seen that the Act provides for two types of relationship: “serving together” and “acting in combination”. Under the former, as interpreted by the lawyers, the forces are independent of each other. With the forces “in combination”, however, command is unified and the commander of one force possesses correspondingly wide powers over the other. It may be noted at once that during the Second World War a considerable part, at least, of the Canadian force in the United Kingdom was normally “serving together” with the British, and not under the control of the War Office or of any British commander. However, when active operations became imminent, or when a Canadian formation was assigned a definite operational role in the defence of the United Kingdom, Canadian forces concerned were placed “in combination” with the British formations detailed for the task and thus ,passed under higher British command.

The interpretation and implementation of the Visiting Forces Act gave much employment to lawyers and many headaches to staff officers. At the

* In this statute, “home force” means a Canadian force; “other force” means one belonging to another Commonwealth country.

outbreak of war the Canadian Government appointed an inter-departmental committee to consider and report upon the legal and constitutional questions raised by the Act. This Committee made its report in October 1939.2 On this basis, the Minister of National Defence recommended that an order-in-council be made placing the Canadian military forces in Great Britain in the position of “serving together” with those of the United Kingdom and stating that such forces would be “in combination” with those of the United Kingdom from the time of embarkation for, and while serving on, the continent of Europe. Such an order-in-council (PC 3391) was duly made on 2 November 1939.3 In order to meet any situation which might demand a unified command within Britain, it provided that portions of the Canadian forces might be placed “in combination” by orders issued by Canadian service authorities designated for the purpose by the Minister of National Defence.* Subsequently the Minister designated the GOC 1st Canadian Division and the Senior Combatant Officer of Canadian Military Headquarters, London, as appropriate “Canadian Service Authorities” under PC 3391.

The memorandum of instructions entitled “Organization and Administration of Canadian Forces Overseas” which General McNaughton received before leaving Canada4 did not define the relationship between the GOC 1st Division aid the British military authorities beyond providing, “All matters concerning military operations and discipline in the Field, being the direct responsibility of the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in the theatre of operations, will be dealt with by the General Officer Commanding, Canadian Forces in the Field, through the Commander-in-Chief, whose powers in this regard are exercisable within the limitations laid down in the Visiting Forces Act. ...” In the conditions of 1939, no further directive seemed necessary; but, as we have already shown, events were to develop in a manner which nobody foresaw.

During the winter of 1939–40 discussions with the War Office clarified the status of Canadian troops in Britain vis-à-vis the United Kingdom forces. As we have seen (above, page 231) these conversations resulted particularly in establishing the fact that training policy was to be controlled by the Canadian authorities.5

The first necessity for taking action under the Visiting Forces Act in an important operational emergency arose in connection with the Norwegian campaign.

* “That, in respect of any Military and Air Forces of Canada serving in the United Kingdom, those parts thereof as may from time to time be detailed for that purpose by the appropriate Canadian Service Authorities as from time to time designated by the Minister of National Defence, shall act in combination with those Forces of the United Kingdom to which the same have been so detailed.”

The Proposal to Send Canadian Troops to Norway

Need to find a place for the reference to footnote6

What the First Lord of the Admiralty called a period of “strange and unnatural calm” came to a sudden and violent end on 9 April 1940 when the Germans invaded Norway and Denmark. The latter country was completely overrun at once, and in Norway the Germans, acting with the combination of unscrupulousness, energy and tactical skill which they were so often to display in this war, established themselves so firmly in twenty-four hours in Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Stavanger, Kristiansand and Narvik that they were not evicted from Norway until the general collapse of their European empire in 1945.

The British authorities were caught without either appropriate plans or adequate organized forces for the campaign thus thrust upon them. It is true that there had been a plan to intervene, through Norway, on behalf of Finland in the latter’s war with Russia which ended in a Finnish surrender in March; it was also hoped to deny Swedish iron ore to the Germans. The decision to mine the inshore passages known as the “Norwegian Leads” (taken by the Anglo-French Supreme War Council on 28 March, as a result of the Germans’ use of the Leads for moving ore to Germany from Narvik, and justified as a reprisal against German illegalities in the conduct of the maritime war)7 had been accompanied by a decision to send British and French troops to Narvik, and to dispatch other forces to Stavanger, Bergen and Trondheim, to deny these places to the enemy. This was a precaution against the mining provoking German action, and the Allies did not intend actually to land troops in Norway until the Germans had violated Norwegian territory, or there was clear evidence of their intention to do so.8 The forces for Stavanger and Bergen were embarked in cruisers at Rosyth on 7 April, but were hastily put ashore again on the following day when news arrived that the German fleet was out.9 When it became clear that the Home Fleet and the Royal Air Force had not succeeded in interfering effectively with the German invasion of Norway, it was necessary to make new plans, although the small forces earmarked for the previous scheme were still available.

It may be noted here that during the Norwegian campaign the Germans captured documents revealing the state of British preparations before the invasion. They naturally made much of these for propaganda purposes.* However, the Nazis had by this period established such a reputation for mendacity that very few people believed them even when they were telling

* The present writer possesses a beautifully printed volume entitled Britain’s Designs on Norway: Documents Concerning the Anglo-French Policy of Extending the War, published by the German Library of Information, New York, later in 1940. These include facsimiles of documents captured from the Headquarters of the 148th British Infantry Brigade, including an operation instruction dated 6 April.

part of the truth. In fact, of course, the German enterprise had been planned long before the Anglo-French operation took definite shape. The acquisition of bases in Norway was recommended to Hitler by Admiral Raeder as early as 10 October 1939. In December the Norwegian traitor Quisling came to Berlin and arrangements were made with him. On 16 February HMS Cossack entered Norwegian waters to rescue British seamen from the German ship Altmark. Hitler issued his preliminary directive for the attack on Norway on 1 March. On 26 March he agreed to launch the operation (“Weserubung”) “about the time of the new moon” (7 April), and the date was specifically fixed by another directive of 2 April.10

Faced with the need for forces to act in Norway, the War Office turned in due course to the Canadian military authorities in the United Kingdom. No approach was made to them, however, until 16 April, a week after the German operation began. In the meantime, the British had been developing plans for counter-action and taking the first steps. Two places in Norway commanded particular attention: Narvik, the ore port in the far north, and Trondheim in Central Norway, which had direct railway connection with Oslo and offered the hope of effectively supporting Norwegian resistance. By 10 April British plans had crystallized to the extent of a decision to take both Trondheim and Narvik. The Narvik expedition was launched first. It was a relatively simple matter to reassemble the force previously intended for action in Norway, and its first flight sailed from Britain on 12 April.11

The plan for the enterprise against Trondheim took shape rather more slowly, but it hardened (at least temporarily) during 13–16 April in the form of a triple operation: there were to be landings at Namsos, north of Trondheim, and at Aandalsnes to the south of it, followed by a frontal combined operation against Trondheim itself.12 On 14 April, when the Chief of the Imperial General Staff issued his instructions to Major General Carton de Wiart, who was to command at Namsos and eventually to command the Allied forces in Central Norway, the plan was still fluid, and there was no reference in the instruction either to an intended landing at Aandalsnes or to any use of Canadian troops.13 By the night of 15–16 April, however, the Aandalsnes landing had been added and the plan for the direct attack on Trondheim further elaborated.14 In this latter phase Canadian assistance was required.

At eleven o’clock in the morning of 16 April Major General R. H. Dewing, Director of Military Operations it the War Office, came to CMHQ and placed before General Crerar an outline of the proposed operations, accompanied by a request that the Canadians, “in view of lack of other trained, troops in the United Kingdom”, might take part. The scheme is thus outlined in General Crerar’s war diary:–

The proposed operation is that Maj. Gen. de Wiart’s force, having landed at Namsos on 16th will advance south on Trondheim; heavy naval forces will enter the fjord and 2 battalions of Guards will land to capture the aerodrome; a subsidiary landing party is planned at Romsdals, to advance north along the railway on Trondheim. To neutralize the German-held forts commanding Trondheim fjord, it is planned to land several parties of infantry from destroyers, to take them in rear; 8 parties of about 100 infantry will be needed, the best type of personnel, and War Office suggests Canadians might furnish these parties. Leadership and initiative essential qualifications for their task.

General McNaughton at once came to CMHQ from Aldershot, and he and Crerar went to the War Office. They saw General Dewing, and McNaughton subsequently had an interview with the CIGS McNaughton had already received from the Deputy Judge Advocate General at CMHQ the advice that he had the legal authority to detail Canadian troops for such an operation, and accordingly he agreed to assist.15 General Ironside said that “under the particular circumstances of the shortage of available troops” his acceptance was much appreciated. Detailed plans for the attack, it was explained, were still being worked out.16 Since they did not necessarily involve landings at the forts, it is possible that the Canadians, if employed at all, might have been used for the main landings.

General McNaughton immediately set about organizing the force required. It was drawn from the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade; as the brigade commander, Brigadier G. R. Pearkes, VC, was ill, the acting commander, Colonel E. W. Sansom, was appointed to command the party. Two of the brigade’s battalions (Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and The Edmonton Regiment) were to take part; they were considered “the most advanced units in training”17 in the Division, and had some Scandinavians in their ranks. The heavy administrative tasks of providing special winter clothing, etc., were at once undertaken; and General McNaughton issued, under authority of PC 3391, an “Order of Detail” placing Colonel Sansom’s force “in combination” with the British force organized for operations in Norway.*

* This was Order of Detail No. 2. No. 1 supposedly dealt with teams of Canadian anti-aircraft Lewis gunners lent in March 1940 for the protection of North Sea trawlers, but it is questionable whether any formal order was finally issued in this connection.18

The Canadian contingent as finally organized was 1300 strong. It left Aldershot for Scotland on the evening of 18 April, being played to the station by the pipes of The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada. The following evening it arrived at Dunfermline, and went into camp to await embarkation.19

The embarkation never took place, for the British War Cabinet and its military advisers had changed their plans. The process of change has been described by Sir Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, and by the British official historian of the campaign. On 17 April the Trondheim plan as sketched above was described to the War Cabinet, and the Chiefs of Staff testified that they agreed with it and, while admitting that it was

risky, considered the risks worth running. However, by the 19th, “a vehement and decisive change in the opinions of the Chiefs of Staff and of the Admiralty” had taken place:–

This change was brought about, first, by increasing realisation of the magnitude of the naval stake in hazarding so many of our finest capital ships, and also by War Office arguments that even if the Fleet got in and got out again, the opposed landing of the troops in the face of the German air power would be perilous. On the other hand, the landings which were already being successfully carried out both north and south of Trondheim seemed to all these authorities to offer a far less dangerous solution. The Chiefs of Staff drew up a long paper opposing “Operation Hammer”.

The Chiefs now recommended, in other words, that the frontal attack on Trondheim be abandoned, and that enveloping movements from the flanks, where we already had troops ashore at Namsos and Aandalsnes, be adopted instead. Although Churchill himself was “indignant” at the reversal, he supported the Prime Minister in accepting the Chiefs’ recommendation.20

Essentially, it would seem, then, the Trondheim scheme had already been abandoned at the time when Colonel Sansom and his men arrived at Dunfermline. However, the possibility that they might be used elsewhere was now considered, and a paper written by Mr. Churchill on 19 April suggested that their destination, along with that of the French troops who were available, could “for today or tomorrow be left open”, and that the Canadians in particular should be considered as reinforcements for the Narvik enterprise.21 The following day a staff officer at the War Office told Lt. Col. E. L. M. Bums of CMHQ that Sansom’s force would “probably” be required for “an operation similar to that previously intended, in another area”; he would give no details. Later on the 20th General McNaughton had a conference with General Dewing and it was agreed that if further plans involving the use of Canadians were made, McNaughton would be fully informed so that he could satisfy himself concerning the project and ensure that the troops were properly equipped. Dewing remarked that if the Canadian Division, “now at the top of the list for completion of equipment”, were not available for Norway if required, then the equipment would have to be diverted elsewhere.22 However, no further scheme for the employment of the Division, in whole or in part, in Norway was ever actually presented. For a time Sansom’s force remained in reserve at Dunfermline, but the units were back in their barracks at Aldershot on 26 April.23

Only two men of the 1st Canadian Division, Privates G. Hansen and A. Johannson, saw active service in Norway. They were soldiers of the Saskatoon Light Infantry (M.G.), who spoke Norwegian and were lent as interpreters to the 1st Battalion of the King’s, Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, their own unit’s allied regiment. They saw action in the neighbourhood of Dombaas with their adopted battalion, and withdrew with it through Aandalsnes in due course. (They recorded afterwards that the main language difficulty they had met was in understanding Yorkshire English.)24

The 1st Division had suffered the first of many disappointments. Whether the frontal attack on Trondheim could have succeeded, had it been attempted, there is no point in discussing here. It was clearly a perilous enterprise, and not least the Canadian share in it as first proposed. That the Canadian commander was prepared to commit his force to so desperate a venture is evidence that the long period in which the Canadians took no part in active operations was not the result of any reluctance to embark upon dangerous projects.

Little further space need be devoted to this “ramshackle” campaign. The Namsos and Aandalsnes operations belied their early promise, and by the morning of 3 May the Allied forces had been withdrawn from both areas. At Narvik the attack developed slowly. The town was captured, but only on 28 May, when orders had already been issued for the evacuation of Norway. The last British and French troops left the country on 8 June.25 A greater emergency had already arisen, and a greater reverse been suffered, in France and the Low Countries. The new crisis was faced by a new British Government. The Norwegian fiasco had brought down the Chamberlain cabinet, and Winston Churchill was now Prime Minister.

As we have seen, the situation on 16 April when Generals Crerar and McNaughton were consulted by the War Office admitted of no delay, and McNaughton, having been advised that it lay within his legal competence to do so, immediately agreed to permit troops to go to Norway. He did not refer the question to Ottawa – a procedure which would inevitably have entailed some loss of time. Only on the evening of 17 April was a telegram dispatched to the Minister of National Defence through Canada House advising of the action taken and the intention that the Canadian force should leave Aldershot the following evening.26 The Canadian Government* did not find this procedure satisfactory. A reply received in London on the morning of the 18th approved sending the force, but remarked, “It is considered however that such a commitment should not have been entered without prior reference to National Defence and approval of Canadian Government”. A concurrent telegram from the Department of External Affairs to the High Commissioner in London said the same thing in more detail:–

We would have expected that Canadian Government would have been informed by United Kingdom Government immediately participation referred to was required. ...We feel that when consultation commenced intimation should have at once been given by yourself or GOC to afford Canadian Government reasonable opportunity pass on a disposition of such importance to Canadian people as diversion of a portion personnel of present formation to a special Mission of this kind which is a radical departure pre-considered policy and plan.

* At this moment, in the absence of Mr. King in the United States, Colonel Ralston (then Minister of Finance) was “executing the functions” of Prime Minister.

The High Commissioner (Mr. Vincent Massey) immediately replied explaining that the GOC had fully satisfied himself that the military situation justified using Canadian forces and required that orders be given at once. He continued, “In discharge of his responsibility in this matter actions of GOC were based on designation of Minister under authority PC 3391 dated 2nd November, 1939, which require that he should act as necessitated by Military exigency of moment.” The authorities in Ottawa, however, were not mollified. A further telegram of 19 April remarked, “As I previously indicated, we consider any such proposal should have been made by Government of United Kingdom to Government of Canada. From your telegram it does not appear why immediately request was made by CIGS to GOC advice was not given us to permit consideration pending receipt of observations and recommendation of GOC arising from consultation with War Office. Action by Canadian service authority under paragraph III of PC 3391 in detailing forces to act in combination is not considered to relate to service beyond United Kingdom.”27

Just at this time, the Minister of National Defence (Mr. Norman Rogers) arrived in the United Kingdom on a visit arranged before the emergency arose. He discussed the question with General McNaughton, and a telegram which he sent to the Department of External Affairs on 22 April28 indicates that he had come to the conclusion that there was force in the GOC’s arguments. The effect of PC 3391, he wrote, was under consideration: “Will advise you later of any revision that appears to be necessary but wish to emphasize that there are dynamic features in present military situation which argue against too rigid limitation upon actions taken to meet possible emergencies.”

The issue is too clear to require extended comment. On one side the GOC saw primarily the exigencies of the military situation and the need for immediate action, circumstances which none could gainsay. On the other, the Canadian Government was determined that its forces should not be committed to a completely new enterprise without reference to itself. In this particular instance, the authorities in Ottawa were understandably nettled by the fact, which emerged during the discussion, that over thirty hours had passed after the first proposition was made before any information concerning it was sent to Canada. Such a delay never happened again.

It was plain, however, that military expediency required a more exact definition of the powers of the senior Canadian commander overseas in such matters, nor was it hard to see the desirability of his being given a larger discretion than that implied in this exchange of telegrams. The question was discussed in the Canadian House of Commons in the spring of 1941, and the Minister of National Defence, Colonel Ralston, committed himself to a definite statement that troops could not be moved out of the United Kingdom without the Government’s consent. “There is no doubt whatever”,

he said, “that the Canadian government was consulted about the Norway expedition, and it gave its express approval. I wish to say, just to clinch that, that the decision as to the employment of troops outside the United Kingdom is a matter for the Canadian government... the appropriate Canadian service authority [under the Visiting Forces Act] cannot authorize the embarkation of Canadian forces from the United Kingdom without the authority of the Minister of National Defence.”29 General McNaughton, who had felt deeply the censure upon him which he thought was implied in the cables about Norway, discussed this statement with Mr. King when the Prime Minister visited England later in the year. His memorandum of the conversations30 indicates that he asked for a more liberal policy:

Question of restriction on use of troops. Ralston’s statement in Commons which we felt had tied our hands. His attitude in the Norway affair. Conversation with Rogers. Warning that I would not accept censure, and that he should be very certain that he was right before he gave it.

On 10 September the Cabinet War Committee discussed the question. The remark was made that while troops could not be sent out of the United Kingdom on the sole authority of the Corps Commander under the law as it stood, it might be desirable to extend his authority to include operations based on the British Isles. As we shall see, this was the direction in which policy developed.

“Angel Move”: The 1st Division and the Crisis in the Low Countries, May 1940

On 10 May 1940 another phase of the war began. That morning the German forces drove into Belgium and the Netherlands, two more weak and unoffending neutral states. This was the beginning of a campaign which in scarcely more than a month destroyed the Anglo-French alliance and placed Hitler in control of the coasts of Europe as far as the Pyrenees. These historic weeks passed without the Canadian troops in Britain being committed to the battle; but there were repeated proposals for sending them to France, and on one occasion a brigade actually crossed the Channel. These events we must now review.

In September 1939 a British Expeditionary Force commanded by General Lord Gort, VC, was sent to France and took up positions on the Belgian border. Here it spent the winter, busily engaged in strengthening the inadequate defences of this frontier, along which the Maginot Line, which covered the Franco-German boundary, had never been extended. The British force was gradually built up until at the time of the German attack in May it amounted to ten divisions, plus three more, incomplete, which had been sent out “for labour duties and to continue training”. It was organized in

three Corps. The plan had been to expand it by dispatching ‘the 4th Corps from the United Kingdom “during the late summer”. The 1st Canadian Division, which was training hard in England, was to form part of this Corps.31 These arrangements, of course, were disrupted by the German blow.

During the winter, while the Allies were building up their forces with complacent deliberation, the Germans were preparing for a tremendous offensive in the spring. This operation, known by the code name “Gelb” (Yellow), originated in Hitler’s “Directive No. 6 for the Conduct of the War”, issued on 9 October 1939, which ordered preparations for an offensive “at the northern flank of the Western Front”. Hitler desired to attack almost immediately, but was dissuaded. A succession of further instructions followed until 1 May, when orders were issued that a state of readiness should be maintained to enable the enterprise to be launched at any time on one day’s notice.32 The 10th brought the deluge.

The events which now took place are familiar and can be very rapidly summarized. The Belgians immediately called for help: and in accordance with what was known as Plan “D”, made by the French command for use in such a contingency, the British and French forces on the frontier moved out of their fortified positions and went forward into Belgium, pivoting on the region of Sedan. The object was to occupy a position on the River Dyle, which it was considered would offer a shorter line of defence while at the same time protecting a large area of Belgium from the enemy. Whether or not this move was wise, disaster followed. The Germans struck with extraordinary speed and efficiency. The resistance of the Netherlands crumbled in a few days; the Dutch Army, with which the British and French had been able to make no effective contact, surrendered on 15 May, and the Queen and her Government took refuge in England. Simultaneously the whole Allied position in Belgium was imperilled by enemy penetration across the Meuse to the south. On 13–14 May the Germans broke through at Dinant and Sedan, creating a great bulge in the Allied line.* On the 16th, accordingly, the BEF, and the First French Army on its right, were ordered to fall back to the Scheldt, and proceeded to do so. It proved impossible, however, to prevent the Allied forces being cut in two. The bulge south of Sedan became a break, and the German spearheads, tearing west across the. communications of the Allied northern armies, reached the Channel coast in the Abbeville area on 20 May.33

During the next few days the Allies’ hopes and plans centred upon severing the German corridor to the sea and renewing contact between the

* The original German plan had been to make the main effort on the right, enveloping the Allies’ northern flank – much the same scheme that had been used in 1914. This was abandoned in favour of a heavy punch in the Sedan area intended to lead to the isolation of the Northern armies. Generals Guderian, Blumentritt and Westphal all believe that the new plan originated with Manstein, Chief of Staff to Colonel General von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group “A”.

northern and southern armies. General Weygand, who replaced General Gamelin as Allied Commander-in-Chief on 20 May, proposed to stage an offensive along these lines, but it never materialized. On Thursday, 23 May, the position was roughly as follows. The Anglo-French forces cut off in the north and fighting with their backs to the sea were holding a line from Gravelines on the Channel coast inland to the vicinity of Denain, and thence north to around Menin (south-east of Ypres). From there to the Scheldt estuary it was prolonged by the Belgian Army. The situation as seen from England was obscure. Boulogne and Calais were immediately threatened by the German advance up the Channel coast from Abbeville; and it was not clear whether the land route between these places and Dunkirk remained open. It was obvious, that either the further operations or the withdrawal of the BEF would depend upon the possession of one or more of these three ports. With the object of maintaining the BEF’s essential communications, a British brigade group with tanks, commanded by Brigadier C. Nicholson, landed at Calais on 22–3 May. On the 22nd also two battalions of the Guards with some other troops were sent to Boulogne. This latter force, after considerable fighting with the advancing Germans, found the position untenable and was evacuated by destroyers on the night of 23–4 May.34

On the 23rd the 1st Canadian Division was drawn into the Allied calculations.* Early in the morning General McNaughton was told that he was urgently needed at the War Office and that a brigade group of the Division should be prepared to move “as early as possible”. A warning order was sent to the commander of the 1st Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Armand A. Smith), and General McNaughton drove to London. He had an immediate conference with the CIGS, General Crerar and several senior officers of the War Office also being present. General Ironside explained how the BEF’s supply lines had been imperilled by the enemy advance, and said that he wished McNaughton to go to France “to re-establish the road and railway line through Hazebrouck and Armentieres as soon as possible”. This was to be done by way of Calais, if possible; if not, then by way of Dunkirk. The CIGS added that McNaughton would be placed in command, of the troops in the area, including the brigade group then disembarking at Calais, and suggested that he might be reinforced by a mixed brigade from his own Division and such additional troops as were required. As communication with Lord Gort might be difficult if not impossible, McNaughton was to report directly to the CIGS The Canadian general

* The episode which follows is recounted in some detail. This seems the more desirable as it is not mentioned either in the United Kingdom official history of the campaign or in Sir Winston Churchill’s memoirs.

accepted the task and told Ironside that the 1st Brigade had been ordered to be ready to move by noon.35

After a further quick discussion of details, General McNaughton returned to Aldershot, issued his orders, and then drove to Dover, where the Brigade was to embark. There he conferred with the Vice Admiral commanding at the port (Sir Bertram Ramsay), Lieut. General Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Adjutant General of the BEF, who had just arrived from Calais, and Major General A. E. Percival, Assistant Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

From this conference there emerged two written instructions to McNaughton, both signed by Percival.36 One followed the lines of the conference at the War Office that morning. The most essential parts of it ran as follows:

1. The communications between the BEF now more or less in their old positions on the Franco-Belgian frontier and the ports of DUNQUERQUE [sic] and BOULOGNE have been cut ...

3. It is important to re-establish the road and railway line through ST. OMER – HAZEBROUCK – ARMENTIERES as soon as possible.

4. You are appointed to command this operation. It should be carried out with the utmost possible speed and should be based mainly on CALAIS and DUNQUERQUE ...

5. Comdr. at CALAIS, Brigadier Nicholson, has been instructed that his primary job is to get supplies forward to the BEF. That the best chance appears to be via DUNQUERQUE, and thence through YPRES. If enemy pressure necessitates, he is to move such of his troops as are mobile in the direction of DUNQUERQUE. Those which are not mobile are to remain where they are.

6. A mixed Brigade from the 1st Canadian Division is being prepared now.

7. If the ports will bear any more and you find you can take them a second Mixed Brigade of Canadians will be sent in the best way. 8. You should go provided to run a moving battle with liaison officers and a large proportion of motor cycles, as ordinary communications will not be able to be established at first owing to the amount of enemy mobile troops available.

This was the text of the other directive:

With reference to instructions already issued to you, you yourself with what staff you decide to take will carry out an immediate reconnaissance.

You should first proceed to CALAIS and review the situation there, then you should proceed to DUNQUERQUE and after seeing the situation there, you will report to the War Office as to whether you consider any useful purpose that [sic] can be served by landing a force in or near either CALAIS or DUNQUERQUE.

On your report coupled with the latest information available at the War Office at the time a decision will be taken as to whether the force can be despatched or not and if so So what port.

Both orders bore the same date and hour (“23 May 40, 2030 hrs”). In other words, General McNaughton was given a free choice between them. He could produce the first and take command in the Pas de Calais if he chose; on the other hand, if on arriving in the area he decided that the situation was not such that the original instructions remained valid, he could act on the second and simply report to the War Office.37 Few officers have

had such wide discretion in so great a crisis. With the two sets of instructions in his pocket, McNaughton, accompanied by his GSO1 (Lt. Col. G. R. Turner), three junior staff officers, and ten men of No. 1 Canadian Provost Company,* embarked in H.M. Destroyer Verity and sailed for Calais, which he reached half an hour before midnight.

At Calais he spent two hours, interviewing various officers, British and French, and gathering information. He did not see Nicholson, who was out going round his defences. Not much was known about the enemy. The British troops were holding a close perimeter and had had contact with the Germans at Sangatte, south-west of Calais. A road convoy, escorted by infantry and tanks, was about to set out for Dunkirk with supplies for the BEF. At 1:37 in the morning of 24 May the Canadian party sailed in HMS Verity for Dunkirk. En route, the destroyer was several times attacked by enemy aircraft but arrived safely at 3:30.38 In the meantime, General McNaughton had wirelessed to the War Office a report of what he had seen at Calais.39 It remarked, “Most present garrison can be expected to do is hold perimeter in face of attack”, and added that the troops were in good heart.† At 4:45 a.m. General McNaughton sent through his staff at Dover a further report to the CIGS, emphasizing the importance of Calais and expressing the opinion that the Canadians should be used “to strengthen the situation” there. Conferring with Brigadier

R. H. R. Parminter, Lord Gort’s Deputy Quartermaster General, who had been sent back to hasten supplies, McNaughton learned that the BEF was threatened with an ammunition shortage. Dunkirk was weakly held, but two French divisions under General Fagalde had been ordered to take up positions safeguarding the port. Fagalde was being placed under the direction of Admiral Abrial, the “Amiral Nord”, with whom McNaughton discussed the situation. Early in the morning Fagalde arrived and confirmed that these divisions were on the way. By this time it was known that the convoy from Calais had been turned back by enemy armour, only three tanks succeeding in breaking through. The road from Calais to Dunkirk was now closed. Information concerning enemy attacks continued to come in. There was pressure on the line of the River Aa, between Calais and Dunkirk, and Calais itself was being bombed and shelled. Shortly before ten o’clock McNaughton telephoned one of his staff at Dover and instructed him to seek permission from General Dewing for him to return to England to discuss the situation “with a responsible representative of the War Office”, for there were aspects

* This company, the 1st Division’s military police unit, was raised in 1939 entirely from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. See Asst. Commissioner L. H. Nicholson, “Battle-dress Patrol” (Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly, October 1946–January 1947).

†Brig. Nicholson was later told that he and his men must fight to a finish to keep pressure off the BEF at Dunkirk, and they did so. Resistance in Calais ended late on 26 May.40

which could not be described over the telephone (see below, page 272). Before a decision could be obtained from Dewing, a senior staff officer of the War Office, Lt. Col. A. H. Hornby, called General McNaughton in another connection and agreed that his return was desirable.41 General Crerar was with Hornby during this conversation.42 McNaughton and his party left Dunkirk immediately in the Verity, and were back in Dover about one in the afternoon.

In the meantime, there had been great activity at Aldershot. The force to take part in what was known as “Angel Move” was to consist of a small divisional headquarters plus the units of the 1st Brigade (The Royal Canadian Regiment, The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment and the 48th Highlanders of Canada), two machine-gun battalions, two anti-tank batteries, the 3rd Field Regiment RCA, the 1st Field Company RCE, the 4th Field Ambulance RCAMC, and some detachments.43 The machine-gun battalions were not to go at once, and the field regiment, which was at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain, was to move through Southampton. The rest of the force was to sail in two flights from Dover, probably on the morning and afternoon of 24 May. Tremendous efforts were required to collect the necessary supplies, ammunition being a special problem.44 In the early morning of 24 May the Canadian units began to arrive at Dover, and by eleven o’clock those of the first flight, including the Brigade Headquarters, the 48th Highlanders and the RCR, were embarked and ready to sail. However, as a result of General McNaughton’s reconnaissance, they never sailed.

At Dover, the GOC on his return from Dunkirk had found no “responsible representative of the War Office”; and after telephoning Dewing he drove to London. At 4:50 p.m. he reported to the CIGS at a meeting in the latter’s office which was attended by the principal officers of the War Office as well as General Crerar and Lt. Cols. Turner and Homby. It emerged that, with General Fagalde’s two divisions in the Dunkirk area and two British divisions reported to be moving towards Aire and St. Omer, the small reinforcement represented by the Canadian brigade group would not contribute materially to improving the situation; on the other hand, if the French troops were not in a mood to fight, there seemed little point in throwing the Canadians into the midst of a mass of dispirited soldiers and civilian refugees. The unanimous conclusion of those present was that there was no purpose in sending the Canadian force to Dunkirk. McNaughton then accompanied General Ironside to a meeting of the Defence Ministers and Chiefs of Staff, which was attended by Mr. Churchill, Mr. A. V. Alexander, Mr. Eden, Sir Archibald Sinclair, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound (First Sea Lord), Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall (Chief of the Air Staff), and others. McNaughton again reported what he had seen and heard. No final decision was taken, the Prime Minister stating that he

“wished General McNaughton to consider himself at two hours’ notice for any eventuality”.45 However, it was impossible for the troops to remain embarked indefinitely, and they were ordered back to Aldershot. To the men at Dover, who had waited on board all day, the order was a bitter disappointment. “A very flat feeling for all of us who had been highly keyed up”, recorded the diarist of Brigadier Smith’s headquarters.46 The Canadian Government had been informed of the intended operation as soon as it was proposed.47 An immediate reply came back: “We have been deeply moved by the momentous news contained in your telegram. We shall all look forward with deep anxiety but firm confidence to the part that will be taken by our Canadian men in the hard and vital task of the next few days.”48 The project that had occasioned this message was formally cancelled on 25 May;49 but more was to be heard of it.

The Dunkirk Evacuation

On the further side of the Channel, Lord Gort was anxious for reinforcements from England. His situation was becoming increasingly perilous; the Belgian Army on his left was weakening under the German onslaught, and he was obliged to think in terms of falling back upon the coast in the hope of being able to evacuate his army through Dunkirk. Early on 25 May he was informed of the decision not to send Canadians to that port.50 He considered, however, that it would be useful to have “a nucleus of fresh and well trained troops on the bridgehead position”, and (later on the 25th, it would seem) he asked the War Office to send him a Canadian brigade.51 The War Office prepared to comply. At 1:50 a.m. on 26 May, Headquarters 1st Canadian Division was informed that the previous scheme had been revived, and that the same troops made ready a few days before would embark on the night of 26–7 May. Warning orders were issued to the units, and at about 10 a.m. Generals McNaughton and Crerar went to Whitehall to discuss the project with General Sir John Dill (who had returned from France in April to become VCIGS and was now about to be appointed CIGS) and General Dewing. The records indicate that all four generals were in accord in the view that it was useless to send more troops across the Channel. McNaughton nevertheless made it clear that he was quite prepared to undertake the operation if it was decided upon, provided only that his artillery could be dispatched with the rest of the force (it had been indicated that the field guns would not arrive until at least twenty-four hours after the infantry).52 General Ironside and the Secretary of State for War subsequently joined in the discussion, and Mr. Eden showed “some perturbation”53 at the doubts

which were being expressed about the operation, as the British War Cabinet, acting on the advice of the Chiefs of Staff, had decided on the previous evening that the Canadian brigade should go. McNaughton told Eden that his objection to the plan “was not based on any timidity but rather on a desire to get the best possible value for the effort made”, and added that while the matter was being further considered he would make every effort to ensure that the brigade group could “go tonight complete with guns if the Prime Minister and War Cabinet decide that it should be sent”. In the course of the discussion the British generals had referred more than once to the fact that the defence of Britain was now an essential consideration and that troops important to this object should not be thrown away for the sake of what Dewing is reported to have called “a gesture to help the BEF.”54

Following this discussion, the CIGS showed McNaughton and Crerar the draft of a telegram to Lord Gort informing him that it was unlikely the Canadians would go; but the project was not cancelled until later in the day, when Mr. Churchill’s concurrence was obtained.55 Soon after noon the troops at Aldershot, who were busy preparing for the move, received word of this second cancellation. This time, however, the vehicles were left loaded and the 1st Brigade remained on eight hours’ notice. This proved a wise precaution. Late in the afternoon Gort telegraphed Eden, strongly requesting that the Canadian brigade should go and be followed if possible by a second. “These troops are required urgently to assist withdrawal”, he wrote. Some hours later he repeated his plea, stating that the Canadians were required “to enable offensive mobile operations to be undertaken on Belgian front by other troops in order to safeguard security of withdrawal”.56 Shortly after seven o’clock in the morning of the 27th General Dewing telephoned General McNaughton to the following effect (the elliptical manner of speech was adopted in case the conversation was overheard):57

Have had conversation with fellow on the other side [Gort]; he has made an appeal to be passed on. My recommendation is the same as yesterday, but no one should be far away as the matter will be considered by the higher ones about 1000 hrs. I have seen our new man [Dill] and his view is the same as yesterday. However, black coats may not accept and movement control has been warned.

The divisional staff and Brigadier Smith were advised, but nothing was said to the units. During the day General McNaughton and the staff drew up a revised composition for the proposed force. “It was agreed that it should be drastically reduced as regards Headquarters and certain arms, in view of the only result which it could reasonably achieve.”58 But military opinion at the War Office was now strongly against the scheme, and the “black coats” evidently agreed; for in the course of the afternoon Crerar was able to tell McNaughton by telephone, “The landing operation show is definitely off”.59 Thus was “Angel Move” finally relegated to limbo.

The Dunkirk evacuation was now under way. It had begun as early as 27 May, when about 5000 men took ship, but embarkation on a really large scale started only on the 29th. The Anglo-French situation had by then been still further endangered by the Belgian surrender, which took place on the morning of the 28th.* In the end, in defiance of the very grim forecasts made in the beginning, some 338,000 British and Allied soldiers were successfully withdrawn; but their heavy equipment had to be left behind.60 It was an all but disarmed Expeditionary Force that returned to England.

On 27 and 28 May Dewing and McNaughton exchanged letters which merit quotation at length.61 Dewing’s ran:–

27 May, 1940.

My dear Andy,

I am afraid your Division, or a good portion of it, have spent a lot of time on fruitless preparations in connection with their proposed employment yesterday morning. ... I hope there will be no further question of putting troops into Dunkirk, though even tonight the question has been re-opened by a message from Gort asking for support there.

I am absolutely convinced in my mind that to put fresh troops into Dunkirk now with little or no transport would be militarily quite wrong. The most they could do would be to hold the outskirts of the town. and that would not secure the port for Lord Gort. In fact, it would be throwing good material into a quicksand which is already on the way to engulfing far too much. I don’t believe it would add anything to what we should save from the quicksand.

I think, too, there is the greatest importance, as well as the greatest difficulty, at the present time of seeing more than the drama that is immediately before our eyes. We must remember that we have got to win this war, first by defending England and giving the German a jolt when he attacks here; and next by building up a fresh Field Force out of the ruins of the old. Your Division and the 52nd may be vital to the first task, and with the 51st which is already in France will be the keystone on which the new Field Force will be built.

These are the reasons which have influenced me in throwing what little weight I have against the employment of your Division or any part of it in Dunkirk. The part you have been asked to play has been extraordinarily difficult. You went off on your first visit to Calais and Dunkirk full of fire and determination to use your troops to save the BEF. What you thought of it as a military proposition then I don’t fully know, but you were absolutely determined to do thoroughly whatever might be asked of you. Today, I think you share a good many of my feelings of the unsoundness of committing fresh troops to Dunkirk. It was much more difficult for you to express that, because you naturally had the feeling that you might be giving the impression that you and the Canadian troops were not ready to undertake a desperate adventure. I can assure you that you did not give that impression. We all know you far too well for it to be possible for any of us to entertain that suspicion for one moment; and I only mention it because I think it was in your mind.

The opportunity to use the Division will come soon enough, but it must come in circumstances in which it can play a sound military role, as dashing as you like, but militarily practicable.

General McNaughton replied next day:

Aldershot, Hants, 28 May, 1940.

My dear Dick,

On my return from Chatham this evening, I have your letter of yesterday’s date and I very deeply appreciate your friendly thought in telling me of your sympathetic

* The Belgian garrison of Fort Pepinster, one of the forts of Liege, which had been resisting since 11 May, gave in only on the 29th.

understanding of the position in which I found myself in the difficult circumstances of the last few days. You have clearly penetrated to the motives and considerations which governed my actions and it is a great comfort to me to know that this is so.

I was all for Calais on the first night because I thought that from that flank we might, at the least, delay the close investment of Dunkerque and with British troops in effective occupation of the perimeter there was some certainty that our deployment could be effected in an orderly and proper manner.

As for Dunkerque, from the beginning I could not see our employment there as a practical operation of war. With our small force we could not go beyond the near perimeter. De Fagalde, under his mandate, from Weygand, was already in command with his 68th Division in movement and able to reach position much earlier than we. He, as a French general clearly in close sympathy with the Admiral du Nord and with all the local naval, military and air intelligence service at his disposal, was better placed than I, with no British troops on the spot and no staff with local knowledge, to exercise coordination. If I had attempted to do so and produced my instructions from Ironside, they might well have folded up!

When I heard from De Fagalde of his plan for the withdrawal of his 60th Division [in the Bruges area] leaving a gap on the left, I was very anxious thinking that it might result in a torrent of German Infantry behind our lines. a far more serious matter than the five armoured divisions said to be operating northward in our vicinity. It was to give this, in my view, vital information that I asked permission to return to Dever and later to the War Office.

As for taking the force the next day or the day after to Dunkerque, I could only see it as a gesture of no very great value and I thought it was the sort of thing the enemy would like, that is to draw some part of our not too ample reserves into the melee where they could be dealt with cheaply. For these reasons and others of like sort I could not enthuse over the project put before me.

After my visit to MacDougall of the Home Forces* on the afternoon of 26 May and in the light of his explanation of the situation in the United Kingdom I knew that it would have been an act of utter folly to have sent us over and when, on the morning of 27 May, I heard from you that the project might again be on I determined to cut our force to a minimum so as not to divert any more men or resources from the defence of the United Kingdom than was absolutely necessary for the purpose of a gesture and if the War Cabinet had called on us my orders for a force, armed only with Small Arms and Anti-Tank guns and without field guns or transport, had been drafted; this force to be landed on the open beach from Dover so as to save time and perhaps avoid the dangers in the Channel from mines and air bombing.

However, thanks largely I think to the sound military judgment of yourself and of Dill this rather theatrical sacrifice was not required of us.

Our problem now is to beat Germany and to do this we must maintain at least a toe hold on this side of the Atlantic until great friendly forces can come. and I have faith they will come, to our assistance. The coast of the United Kingdom is the perimeter of the citadel which must be held. All else outside is now of secondary account. ...

This correspondence provides the best commentary upon the events. And the outcome of the evacuation operation justified the generals’ judgement. It is difficult to see how sending a Canadian brigade to Dunkirk could have contributed to bringing about a better result. It would, indeed, have introduced an unnecessary complication, would almost certainly have meant the loss of more equipment, and might well .have meant the loss of more men.

* Brigadier A. I. MacDougall, employed as Major General, General Staff, GHQ Home Forces. It was during this interview that McNaughton suggested organizing his force in mobile groups and using it as a central reserve (see below).

First Measures Against the Invasion Menace

From the time when the Germans broke into the Low Countries, increasing anxiety was felt for the safety of Britain herself. On 26 May, General McNaughton had produced the idea of organizing his division in nine mobile groups, each based on an infantry battalion, for action in the United Kingdom. He suggested that it might move to a central area (the Oxford region was mentioned) where it could be ready for immediate counterattack against an enemy landing anywhere in southern England. This project was approved, though the area was changed. On 27 May orders were issued for the 1st Canadian Division to move to an assembly area in the district Kettering–Higham Ferrers–Northampton.62

Before the move took place, the Division and the Canadian ancillary troops were formed into a self-contained body known as “Canadian Force”; and on 29 May the new formation began the march to the Northampton area. It covered four nights, one brigade group moving each night in civilian buses hired for the purpose.”63 (In addition to the three infantry brigade groups, a “Canadian Force Reserve Group” had been formed from the ancillary artillery regiments and machine-gun battalions.) At Northampton, Canadian Force was in “GHQ Reserve”: that is, it was a reserve formation directly under GHQ Home Forces. Its role was that of reinforcing the troops on the east coast between the north bank of the Thames and the south bank of the Humber in case of attack there. Each brigade was instructed to reconnoitre one sector of this front, and the routes leading to it. General McNaughton himself, and other officers of his headquarters, also made reconnaissance trips in the area where the Force might be required to operate.64

The people of Northampton and the other towns in the new area seemed delighted to see the Canadians, gave them a great reception and entertained them warmly during their stay.65 The stay, however, was very short. It was terminated by further events on the Continent. The Dunkirk evacuation was completed on Tuesday, 4 June. The British Government at this moment was uncertain as to the Germans’ next move. The situation was frankly stated by Mr. Churchill in the House of Commons on this same day: “We must expect another blow to be struck almost immediately at us or at France”. Two days earlier, the Prime Minister had put his views on paper, for the benefit of the Chiefs of Staff. The memorandum66 ran in part:–

3. The BEF in France must immediately be reconstituted, otherwise the French will not continue in the war. Even if Paris is lost, they must be adjured to continue a gigantic guerrilla. A scheme should be considered for a bridgehead and area of disembarkation in Brittany, where a large army can be developed. We must have plans worked out which will show the French that there is a way through if they will only be steadfast.

4. As soon as the BEF is reconstituted for Home Defence, three divisions should be sent to join our two divisions south of the Somme, or wherever the

French left may be by then. It is for consideration whether the Canadian Division should not go at once. ...

I close with a general observation. As I have personally felt less afraid of a German attempt at invasion than of the piercing of the French line on the Somme or Aisne and the fall of Paris, 1 have naturally believed the Germans would choose the latter. ... The next few days, before the BEF or any substantial portion of it can be reorganised, must be considered as still critical.

On 4 June CMHQ telegraphed to Ottawa,67

It is now planned to move in near future certain divisions in the United Kingdom to France to join 51st Division at present Abbeville area and thus form the first corps of a reconstituted BEF. I am informed by decision taken yesterday it is not proposed immediately to utilize 1st Canadian Division for this purpose. Chiefs of Staff Committee views threat of enemy landings between the Thames and the Humber as definite and imminent and is not willing to release Canadian Force from important responsibilities now entrusted to it in this connection.

Speculation was ended, and the situation much altered, when on 5 June the Germans launched an offensive against General Weygand’s line along the Somme and Aisne. On the 6th the War Office ordered Canadian Force back from Northampton to Aldershot. By the 8th the movement had been virtually completed, and that day Their Majesties the King and Queen visited the Division.68 This honour was rightly interpreted as indicating that the units would shortly find themselves on the way to France.69

Forlorn Hope: The Second BEF, June 1940

On 29 May, when the Dunkirk evacuation was only beginning, Mr. Churchill had declared to the French Government his intention of building up “a new BEF.”70 It was now becoming a reality, although the hard facts of the situation reduced it to pitiably small proportions. Lieut. General Sir Alan Brooke, who had been GOC the 2nd Corps of the original British Expeditionary Force, was to command it until it could be further built up. The only British divisions in France after Dunkirk were the 51st (Highland) Division, which had been in the Saar region and had never joined Lord Gort, and the 1st Armoured Division, which had landed too late to make contact with him. These divisions were to be the foundation of the new BEF; but before it could be formed the 51st was cut off in the Le Havre peninsula and the greater part of it was obliged to surrender on 12 June. The Armoured Division, which had been reduced in the beginning by the force sent to Calais, had suffered further in fighting on the Somme.71

Every division in England fit to move was now to be sent to France under General Brooke’s command; but the grim fact was that for the moment there were only two such divisions. The 52nd (Lowland) Division had already been under orders to move; the move was now somewhat accelerated and began on 7 June.72 The 1st Canadian Division was to

follow as soon as possible. The only other division which could be dispatched in the near future was the most forward of those evacuated from Dunkirk, the 3rd, commanded by Major General B. L. Montgomery. It was warned on 8 June; but its movement could not begin until the 20th, and only one field regiment of artillery, and an anti-tank regiment less two batteries, would then be available to accompany it.73 All the other Dunkirk divisions were still so short of equipment as to be incapable of taking part in an expeditionary movement for some time to come.

The generosity of Britain’s action in sending her “only two formed divisions”74 to support the French at this desperate moment has been recognized by General Weygand.75 Nevertheless, there was a definite limit to the risks which the British Government was prepared to run for its ally. It would not throw into the cauldron the whole of the metropolitan fighter force of the RAF, on which Britain’s safety depended. In the middle of May the Chief of the Air Staff supported Air Chief Marshal Dowding, AOC-in-C Fighter Command, in arguing that continuing to drain away the home defence force in attempts to save the situation in France would merely render the future successful defence of Britain impossible. Mr. Churchill resolved on 19 May that no more fighter squadrons would leave the country.76

The refusal to throw in all the resources of Fighter Command was deeply resented by the French. And in a purely military view the decision to commit every available Army division, while at the same time refusing the air support without which their operations could scarcely be effective, was a peculiar one. It emphasizes the fact, which indeed emerges clearly from Mr. Churchill’s memoranda, that the formation of a new BEF was a political rather than a military act; its object was to encourage the French and keep them in the war. It involved the likelihood of destruction for the divisions concerned, but the stakes were such that it cannot be said that it was wrong. At the same time, it seems clear in the light of later events that the British Government was wise to hold back the fighter squadrons. It seems unlikely that this force could in itself have turned the tide on the Continent; more probably, it would have been merely engulfed in the devouring quicksand. But it won the Battle of Britain later in the year and in doing so prevented the final loss of the war.

General Weygand has suggested that because there is doubt whether Hitler really intended to invade England, the argument from the Battle of Britain may be invalid.77 It is difficult to agree with him. It is true that there is reason to think that Hitler never wholly committed his mind to the invasion project; but had the Luftwaffe won the Battle of Britain and obtained air superiority above the Channel, it is hard to believe that invasion would not have been attempted. It is even possible, though certainly not probable

that Britain might have been brought to ruin by the air weapon alone.*

* “The crux of the matter is air superiority. Once Germany had attained this, she might attempt to subjugate this country by air attack alone.” (Paper by the British Chiefs of Staff, 26 May 1940).78

General Brooke received his orders on 10 June and sailed for France on the afternoon of the 12th.79 There were officers at the War Office who never expected to see him again.80

The Canadian Government was being kept fully informed of developments affecting its forces in Britain. A telegram of 14 May had referred to the possibility of a movement “to theatre of operations” earlier than 15 June, a date which had been mentioned in earlier correspondence. With the concurrence of the Minister of National Defence, the CGS informed General McNaughton on 15 May that this was approved “if you consider the circumstances warrant it”. On 6 June Ottawa was advised of the orders which had been issued for the return of Canadian Force to Aldershot and the expectation that the Division would begin to move to France on 11 June. Later telegrams gave further details as these came to hand.81 To clarify the legal position of the Canadian troops, McNaughton had executed a new Order of Detail under the Visiting Forces Act on 1 June.82 This was the first such order in which the right to withdraw troops from combination was specifically included; it specified that the forces detailed in the Order would continue to act in combination with those of the United Kingdom “until I shall otherwise direct.”

After “a period of intense activity” on the part of the administrative staffs of the 1st Division, preparations for the cross-Channel move were, for the most part, completed by 9 June. That day a divisional conference was held at which commanding officers were told the anticipated nature of the operations in France, and a telegram of “heartfelt good wishes” from the Prime Minister of Canada was read. On 11 June, there was another conference, dealing mainly with equipment. While it was in progress General Brooke arrived at Aldershot, accompanied by several members of his staff, and himself presided over the latter part of the meeting.83 This visit gave General McNaughton an opportunity of discussing the forthcoming operations with the Corps Commander.

The Role of the Second BEF

It is not surprising that the plans for the operations of the Second BEF are not clearly recorded, or that all concerned with executing them were not fully apprised of their nature. With the Anglo-French alliance rapidly falling asunder, and France herself tottering to ruin, it might have been surprising had it been otherwise. It is our task, however, to outline, as far as the

available records permit, the ideas which dominated the minds of those in control, and the nature of the Canadian share in the resulting plans.

The written instructions which General Brooke received from the Secretary of State for War were brief and general. He was simply informed that he was to command all British troops in France and to cooperate in the defeat of the enemy under the supreme command of General Weygand.84

It is necessary here to trace the history of one important project of this period: that for setting up what was called a “redoubt” (more accurately, a “reduit” or keep) in Brittany, upon which French forces could retreat, where the French Government might take refuge and continue to operate on French soil, and to which British assistance could be directed. It appears that this scheme was first discussed with General Weygand by the heads of the French Government on 29 and 30 May; and on 31 May the French Prime Minister (M. Paul Reynaud) gave Weygand written instructions to consider the possibility of forming “a national redoubt in the neighbourhood of a naval base, which would enable us to benefit from the freedom of the seas, and likewise to remain in close touch with our allies”. This work, he said, should be laid out and provisioned like a fortress; it “might be situated in the Breton peninsula”. Weygand had no faith in the scheme, but he gave instructions for work to begin at once with a good Corps Commander in charge.*

* It appears nevertheless that when Reynaud on 13 June wrote Weygand emphasizing the importance of the “redoubt” scheme, the general replied (14 June) that on the 11th, when he drafted his order for general retreat, he had not known of the government’s intention to set up a keep in Brittany.85 Presumably he had regarded the earlier orders as merely precautionary.

The plan was, he says, extended after consultation with the French Navy to cover not only Brittany but also the Cotentin peninsula, including the port of Cherbourg.86 This extension made a dubious project still more impracticable. Published information does not indicate that the British Government was advised of it.

Weygand states87 that the redoubt scheme was approved by Mr. Churchill at the meeting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council on 31 May. It was doubtless discussed at this time, but it would seem that it was not mentioned during the Council’s formal session.88 As we have already seen, however, Churchill’s memorandum sent to the British Chiefs of Staff two days later makes definite reference to the idea of a “bridgehead” in Brittany. On 11 June the Supreme War Council met again, at Briare. By this time, the Germans had broken through Weygand’s line on the Somme and Aisne, and the situation was becoming desperate. Sir Winston Churchll has confirmed that at this meeting he agreed with Reynaud “to try to draw a kind of ‘Torres Vedras line’ across the foot of the Brittany peninsula”.89

How far this idea was communicated to General Brooke before he embarked for France does not appear. The records of the conferences at

Aldershot on 9 and 11 June give no details of the operational plans proposed to the Canadians; they were presumably not circulated for security reasons. Other evidence indicates, however, that Brooke had in mind, and described to General McNaughton, the Breton redoubt scheme or something very closely allied to it.

On 13 June, the day before McNaughton and his advanced headquarters left Aldershot, a draft operation instruction was prepared with a view to issue when the Division arrived in France. As things turned out, it was never issued; but it serves as a record of the roles of the BEF, and of the Canadian Division within it, as they were understood at McNaughton’s headquarters after Brooke’s visit.*

* A copy of this draft, with covering letter dated 13 June, was sent to the Senior Officer, CMHQ, for insertion at a future date in the Division’s General Staff War Diary.90 It is interesting to note that at this time, before starting for France, Divisional Headquarters completed its War Diaries to date and forwarded them to CMHQ, along with divisional files not required for the operations in prospect. The 1st Canadian Division was, in effect, making its last will and testament, as it had good reason to do.

Its most important sections (omitting map references) ran as follows:

1. The political object of the reconstituted BEF is to give moral support to the French Government by showing the determination of the British Empire to assist her ally with all available forces.

2. The military object of 1 Canadian Division is, in conjunction with other formations of 2 Corps, to threaten from the general line [ST.] NAZAIRE... RENNES... PONTORSON. ...the flank of a German advance towards LE MANS... ANGERS... NANTES... and relieve pressure on the FRENCH Army by drawing GERMAN forces Westwards.

3. The coasts of the peninsula projecting westwards about 150 miles from the line [ST.] NAZAIRE – PONTORSON have deep water close to the shores and there are many good harbours. The average width from NORTH to SOUTH is about 70 miles. The flanks of a force operating in this area can be supported by the Navy. The country is hilly, intersected by many rivers and well wooded. From a study of the map it does not appear to be suited to the employment of large armoured formations. Apart from its extent, it is thus a favourable theatre for the operations visualized by the British forces available.

4. 2 Corps of the BEF is to consist of the following formations:–

52 Division. Landing at [ST.] NAZAIRE and assembling NORTH of the port.

1 Canadian and ancillary troops. Landing at BREST... and assembling N.E. of the port.

Remnants of 51 Division...

Remnants of 1 Armoured Division ...

2 Corps Troops.

5. It is the intention of the Corps Commander to concentrate the whole of 2 Corps in the area to the NORTH and SOUTH of RENNES as soon as formations are assembled.

6. Thus there are two divisions. part of a third, part of an armoured division and 2 Corps troops available for operations within the area defined above. A division may have to hold up to fifty miles of front...

The movement instructions issued by the War Office for the Canadian Division91 provided that motor transport, which was to move in advance, would embark at Falmouth and Plymouth; troops moving by rail would embark at Plymouth. Only a small proportion of drivers were allowed to go on the mechanical transport ships with their vehicles; the rest went

simultaneously on a “driver ship”. The 1st Brigade, which had suffered so many disappointments in May, was to lead; and Brigadier Smith’s first road parties left Aldershot on 8 June. The vehicles belonging to this brigade’s three battalions and the 1st Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, as well as those of some administrative units, were loaded into ships which sailed for France on the 11th. It is recorded that at Plymouth all regimental control was lost “from the moment the vehicles reached the regulating point” at the port, and personnel and vehicles “became individual units in the hands of the Movement Control”.92

The 1st Brigade in France

As we have seen, it had been General McNaughton’s understanding that his Division after landing at Brest would assemble north-east of that port. He had ordered Brigadier Smith to take command in the assembly area pending his own arrival. Smith was not told the precise area – the divisional headquarters had no information – but it was assumed that he would receive the necessary instructions upon arriving at Brest.93 All these expectations were disappointed. The instructions, apparently originating in the War Office, which had been issued to Movement Control at Brest, were quite different from anything contemplated by McNaughton or Brooke. Headquarters Brest Garrison was informed on 6 June that the movement of the divisions arriving from England would be in accordance with Plan “W” – the same used for the movement of the original BEF in 1939.94 This involved using an assembly area about Laval and Le Mans, roughly 70 miles in advance of the line across the base of the Brittany peninsula which it had been suggested the Canadians were to hold. These unsuitable orders were put into effect in an equally inappropriate manner. When the ships carrying the 1st Brigade’s transport docked at Brest on 12 and 13 June, Movement Control sent the vehicles off up-country in small parties as they were deposited on the dock. At a collecting point at Landivisiau the drivers were given route cards and mimeographed instructions and sent on in groups of ten vehicles, in some cases at least irrespective of units or of whether there were officers or NCOs. with the groups. (The war diary of the 1st Field Regiment, unlike several others, indicates that at Landivisiau vehicles were “sorted out into units” and an attempt was made to place “a senior NCO or driver” (sic) in charge of each group.) As was to be expected, these conditions had an adverse effect on discipline, and there were some reports of drunkenness and reckless driving.95

The procedure with the rail parties was similar. Those of the 1st Field Regiment and the Supply Column RCASC landed at Brest on the 13th and were immediately sent forward by train to their destined assembly point,