Chapter 11: The Raid on Dieppe, 19 August 1942

(See Map 5 and Sketch 3)

German Defences in the West in 1942

Before describing what happened at Dieppe on 19 August 1942, we should examine the general situation of the enemy on the French coast that summer, and describe his defences and dispositions at Dieppe itself.

When the Germans appeared on the Channel coast in 1940 they were flushed with victory and looking forward to an early conquest of or surrender by Britain. The British Commonwealth was in no condition to undertake any but the most minor enterprises against them. In these circumstances, their dispositions in France were primarily directed to preparations for offensive cross-Channel operations. During 1941, however, there was a gradual change in attitude, particularly after it became clear that the Russian campaign which began in June of that year was not to have an early end. More attention was now paid to the defence of the French coast, and special orders were issued in September and October.1 The year’s activity, however, was mainly concerned with constructing field works, and little concrete was poured.2

By December 1941 the German situation was still worse. The offensive in Russia had come to a standstill, and on 7 December the bombs of Pearl Harbor blew the United States into the war. On 14 December Keitel, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, issued a directive which specifically stated that the Arctic, North Sea and Atlantic coasts controlled by Germany were “ultimately to be built into a new West Wall”. Immediate measures, however, were to be largely limited to digging field fortifications, permanent installations being built only at “the most threatened places”. Norway was given the highest priority, with the Franco-Belgian coast second and the coasts of Holland and Jutland third.3 As a result, there was considerable activity during the spring of 1942. And on 23 March Hitler signed his directive No. 40, which dealt with coastal defence problems.4 It

emphasized the importance of unified command arrangements, constant vigilance and improved defences. About the same time Field Marshal von Rundstedt was re-appointed Commander-in-Chief West and took full responsibility for the defence of the French coast.

As spring came on, the Germans became more and more worried about the possibility of raids, and the attack on St. Nazaire (28 March) rendered them particularly sensitive to reports of such enterprises; many raid rumours are recorded in German diaries of this period. But it was not only raids that they feared now. With American troops beginning to appear in the British Isles, and the campaign in Russia still going on, the initiative in the West had passed to the Allies; and Hitler and his generals were confronted with the possibility of their trying to open that Second Front which was already the subject of so much speculation. The notorious communiques issued after Molotov’s visits to London and Washington in June (above, page 315) would probably have been enough in themselves to lead the Germans to take special measures. During the weeks following them, Hitler issued repeated orders enjoining precautions against a major landing in the West.

In March 1942 the German forces there had been at a very low ebb; it would seem indeed that at one moment the armour at the disposal of the Commander-in-Chief West in France and the Low Countries was actually only one tank battalion (stationed in the Paris area).5 The situation map of 12 March shows in the command one armoured division (the 23rd) but it is moving out. As the spring advanced the armoured forces in France were increased; and on 25 June Hitler directed that several of the most formidable formations in his armies were to “be retained in the West as a reserve until further notice”. Those specified were the 6th, 7th and 10th Panzer Divisions, the S.S. Division “Das Reich”, the 7th Flieger Division (the parachute division which had conducted the attack on Crete in May 1941) and the “Göring” Regiment, which was to be enlarged. “Adequate air forces” were also to be held available, and the navy was to keep a reserve of U-Boats ready for intervention “in the event of a sudden enemy operation”.6 On the following day (26 June) the Führer, “in consequence of the gathering of small vessels on the south coast of England”, ordered that the “Reich” Division, after reorganization, was to be transferred to the West immediately. He said further that, in the event of Russian resistance in future operations being less than was expected, he was considering transferring two other S.S. Divisions, “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler” and “Totenkopf” (Death’s-head).7

On 9 July Hitler issued over his own signature a directive which reflected his acute concern for the western coasts.8 It spoke of the impending necessity for Britain of “either staging a large-scale invasion with the object of opening a second front, or seeing Russia eliminated as a political and military factor”. He referred to increasingly numerous reports from agents concerning impending enemy landings, and the “heavy concentration of ferrying vessels

along the southern coast of England”; note that the air attack on ships of the Dieppe force in the Solent (above, page 339) had taken place two days before. Among areas to be regarded as particularly threatened he listed, “In the first place, the Channel coast, the area between Dieppe and Le Havre, and Normandy, since these sectors can be reached by enemy fighter planes and also because they lie within range of a large portion of the ferrying vessels”. In the light of this situation Hitler ordered the immediate transfer to the West of the available units of the Reich Division, without waiting to complete reorganization; the immediate transfer to the West of the Adolf Hitler Division; the rapid organization of the S.S. Corps Headquarters (Motorized) and its transfer to the West with a view to its taking command of all S.S. formations there; and the postponement for the present of the transfer of one infantry regiment to Denmark. The directive concluded:

In the event of an enemy landing I personally will proceed to the West and assume charge of operations from there.

These measures were promptly carried out. The German operational map for 24 July9 shows the S.S. Corps Headquarters (Motorized), now re-christened Headquarters S.S. Panzer Corps, moving by rail to Nogent le Rotrou, while the Adolf Hitler and Reich Divisions are similarly moving into areas near Paris and Laval respectively.

By the time of the Dieppe raid, accordingly, the German army in the West had been greatly strengthened and was in a full state of alert, expecting at any moment what might be a major Allied enterprise. On 12 March there had been in France and the Low Countries only 25 normal and two Ersatz (reinforcement) divisions; there were now 33 normal and three Ersatz divisions.10 In quality the alteration had been still more striking. The S.S. Panzer Corps with its two crack divisions was now in the West; and whereas in March, as we have seen, there had been practically no effective armour there, now three Panzer Divisions (the 6th, 7th and 10th) were in von Rundstedt’s area. There had been a noticeable movement of formations closer to the coast; and the Pas de Calais had been particularly strongly reinforced.

During the first half of August Hitler issued still further orders on the defence of the French coast. It was now that he specifically ordered the construction of what came to be called the Atlantic Wall. On 2 August, at a Führer conference attended by Keitel and senior engineer officers, he gave detailed instructions for a new system of coast defence. Notes on the conference11 (which do not claim to be literal quotations) indicate that he spoke in part to the following effect:

Development work is very limited and scanty at present. A SOLID LINE WITH UNBROKEN FIRE MUST BE INSISTED ON AT ALL COSTS. ... DURING THE WINTER, WITH FANATICAL ZEAL, A FORTRESS MUST BE BUILT WHICH WILL HOLD IN ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.

The coast was to be developed “after the pattern of the West Wall”, making all possible use of armour, and protecting personnel and weapons “in such a way that they cannot be destroyed by systematic bombardment and bombs.” On 13 August Hitler further developed this theme in another conference,12 dwelling on the importance of preventing at all costs “the opening of a second front” and emphasizing that Russia was still fighting and that “at critical moments the British might create difficulties”. The essence of the matter was expressed in one sentence: “THEREFORE THE FÜHRER HAS DECIDED TO BUILD AN IMPREGNABLE FORTRESS ALONG THE ATLANTIC AND THE CHANNEL COAST”.

All things considered, circumstances were not particularly favourable to the success of a major raid on the French coast in August 1942.

The Enemy in the Dieppe Area

The specific situation at Dieppe can be reviewed in detail on the basis of German documents. The highest German military authority in France was the Commander-in-Chief West, who from his headquarters at St. Germain-en-Laye directed affairs from Groningen in Northern Holland to the Spanish border. Dieppe was in the sector controlled, under him, by the Fifteenth Army, with headquarters at Tourcoing; this Army was responsible for the coast from the Scheldt to Dives-sur-Mer near Caen. The Corps concerned with the Dieppe area was the 81st, whose headquarters was in the outskirts of Rouen. The Division responsible for Dieppe was the 302nd Infantry Division, commanded by Lieut. General Conrad Haase. Its headquarters was not at Arques-la-Bataille as our intelligence indicated; it had formerly been there, but had moved on 27 April* to Envermeu, six miles east.13

The 302nd Division’s front ran from the mouth of the Somme almost to Veules-les-Roses, some miles west of Dieppe. It was thus roughly 50 miles, a very considerable frontage. However, it had been shortened when the German defences were reorganized earlier in the summer; it had formerly extended from the River Authie to St. Valéry-en-Caux.14 The 302nd Division, organized in Germany in November 1940, took over the Dieppe sector on 10 April 1941.15 Full records of its work on the defences there are available in its war diary. It is interesting to note that one of its early orders on the subject, issued on 25 April 1941, assumes that -the ports of Le Tréport and Dieppe “will not be attacked directly by the enemy” but will be assailed by means of “landing attempts at nearby points”.16

* It is curious that the situation maps prepared for the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces at Army Headquarters in Berlin (OKH) still showed the division’s headquarters as Arques-la-Bataille at the time of the raid. Any Allied agent relying on these or similar maps for information would have been misled.

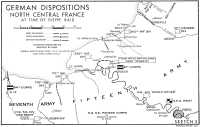

Sketch 3: German Dispositions, North Central France, at Time of Dieppe Raid

Serious fortification of the Dieppe area began in March 1942. On the 15th and 19th of the month the 302nd Division issued orders defining the various strongpoints to be developed in the area.17 Construction of concrete defences now went forward actively. In addition the Division busied itself with demolitions designed to facilitate the defence of important areas. During June and July a certain number of houses adjacent to the beaches in the sector were blown up.18 Before our raid took place part of the Dieppe Casino had also been demolished, but the Germans’ supply of explosives was not equal to its complete destruction.19

Under orders issued on 9 June20 the German defences in the area were organized as follows. The Berneval battery on the right formed an independent strongpoint (Stützpunkt). Dieppe itself was designated a “Defended Area” (Verteidigungsbereich),* sub-divided into three sectors: Dieppe East, including Puys; Dieppe South; and Dieppe West, including the eastern portion of Pourville and the heights overlooking it.

* On 8 July, however, due to the relatively small capacity of the port, which disqualified it as a major invasion objective, Dieppe was “downgraded” to the category “Group of Strongpoints” (Stützpunktgruppe).21

The Varengeville battery constituted another strongpoint, and in the Quiberville area there was a “Resistance Nest” (Widerstandsnest). The whole Dieppe Defended Area was girded on the land side with a continuous barbed wire obstacle. Puys and the heights east of Pourville were inside this, but Pourville village itself lay outside it.22 A good many concrete pillboxes and other positions had been completed by the time the raid took place.

The sector was very strong in artillery. There were three coastal batteries in the area attacked: that at Varengeville with six 15-centimetre (5.9-inch) guns, that at Berneval with three 17-centimetre and four 105-millimetre guns, and one near Arques-la-Bataille with four 15-centimetre howitzers. A fourth battery at Mesnil Val, west of Le Tréport, had four 15-centimetre guns which could fire on the Berneval area. There were also sixteen 10-centimetre field howitzers (the armament of one of the divisional artillery battalions) divided between four battery positions, two on either side of Dieppe and all but one within the wire barrier. In addition, eight French 75-millimetre guns were emplaced on the front of attack for beach defence.23 (The 302nd Division had taken over 15 of these guns from the division it relieved on the coast.) Anti-aircraft guns were also fairly numerous in the Dieppe area. A location statement of 14 June 194224 shows one heavy battery of 75-millimetre French guns, one medium battery of 37-millimetre guns (plus one troop of 50-millimetre) and one light battery of 20-millimetre guns. There were no 88-millimetre guns. The main beach of Dieppe was defended by some nine small-calibre anti-tank guns, including one in a French tank concreted in near the West Mole and two mounted at the front corners of the Casino.25

The German forces in the area were disposed as follows. The garrison of the Dieppe Group of Strongpoints was controlled by the headquarters of the 571st Infantry Regiment (equivalent to a British brigade), located on the West Headland at Dieppe. It consisted of two battalions of this regiment, with headquarters on the West and East Headlands respectively; a battalion of the 302nd Divisional Artillery, manning the four batteries already mentioned; the headquarters of the divisional engineer battalion, and two of its companies; and various minor units, including those of the Luftwaffe which manned the anti-aircraft guns.26 The remaining battalion of the 571st Infantry Regiment was in Ouville-la-Riviere, south-west of Dieppe and outside the Group of Strongpoints, as regimental reserve.

The enemy had large reserves at hand. The 302nd Division’s own reserve consisted of an infantry regiment two battalions strong, with its headquarters at Eu, near Le Tréport. The Corps Reserve was another regiment whose headquarters was at Doudeville, south of St. Valéry-en-Caux, and a tank company at Yvetot. In Army Reserve were four rifle battalions, lately placed in the area about Barentin, north-west of Rouen; an assault gun battalion at Motteville, east of Yvetot; and some motorized artillery between Duclair and Jumièges. We have already noted one element of the Army Group Reserve-the 10th Panzer Division at Amiens. The S.S. “Adolf Hitler” Division (not yet an armoured formation) was at Rosny, west of Mantes-Gassicourt, and the 7th Flieger Division near Flers, west of Falaise.27

Our troops who returned to England after the raid were in general convinced that the enemy had known in advance that it was going to happen and had strengthened Dieppe accordingly. Those who became prisoners were even more strongly of this opinion, having been told that the Germans had been “waiting for us” for days past. Our intelligence staffs, however, ,reported on the basis of information from prisoners and other available sources that the enemy had had no warning; and today, with his voluminous records at our disposal, we can say with complete certainty that he had no foreknowledge whatever of the raid. Throughout the war, indeed, the Germans’ knowledge of what was going on in Britain was almost ludicrously slight and inaccurate.

The events before Dieppe are thus outlined in the report of the German Commander-in-Chief West, dated 3 September 1942:28

From the middle of June onwards, information accumulated at GHQ West as the result of photographic and visual reconnaissance by the 3rd Air Fleet and reports from agents, of an assembly of numerous small landing craft on the South Coast of England.

A further photographic reconnaissance, flown only at the end of July because of poor weather conditions, confirmed the assembly of vessels which had become still more numerous since the large number observed in June.

No further data – except from agents’ reports of an English operation, which could not be checked – could be obtained up to 15 August. In spite of this, GHQ West appreciated the situation from the middle of June to be such that it had to reckon with the possibility of an enemy operation, even a major undertaking, at any moment, and at any point on its extensive coastal front. The U-Boat strongpoints and defence sectors were therefore strengthened as much as possible, both by manpower and by construction (the landward fronts not being neglected), and the organization of the forces was repeatedly checked so that all reserves – local, divisional, corps, and army – would be ready for immediate employment. ...

On 15 August, a sudden change took place in the English wireless procedure which made our interception service much more difficult. Numerous flights toward the Channel Coast suggested the possibility that these were briefing flights, and frequently aircraft shot down were found to have American crews. No further change in the enemy picture appeared until 0450 hours on 19 August, not even as a result of the early reconnaissance of the 3rd Air Fleet.*

The reports from “agents” vaguely referred to were evidently not considered particularly significant; and the references to “briefing flights” and changes in wireless procedure are somewhat discounted by later passages in this same report. At one point it states, “up to the commencement of battle action on the morning of 19 August enemy air operations by day or night had not pointed in any particular way to an impending landing attempt”; while with respect to wireless it adds, “interception of operational and training traffic in England presented no deviation from normal”.29 Rundstedt’s statement that the first real warning of an impending operation came only with our encounter with a German convoy at 3:50 a.m. on 19 August could not be more definite. This and all the other documents now available indicate that the Germans’ actual solid information was limited to the knowledge that during the summer landing craft in considerable numbers had been assembled on the south coast of England; and this, coupled with their general estimates of the strategic situation, led them to intensify their defensive measures along their whole front, including of course the Dieppe area.

Hitler’s order of 9 July presumably led to very special precautions. Particular attention was of course paid to periods when moon and tide were favourable for landings. On 20 July the GOC-in-C Fifteenth Army issued an order30 calling attention to three such periods: 27 July-3 August, 10–19 August, and 25 August-1 September. On 8 August, accordingly, the headquarters of the 302nd Division ordered a state of “threatening danger” (drohende Gefahr) for the ten nights from 10–11 to 19–20 August.31 The enemy coastal garrisons were thus under a special alert at the moment of the raid.

On 10 August, at the outset of this period of alert, the commander of the Fifteenth Army sent out an order32 beginning, “Various reports permit

* Italics represent underlining in the original document. The time mentioned (3:50 a.m. BST) is that of the encounter with the German convoy.

the assumption that, because of the miserable position of the Russians, the Anglo-Americans will be forced to undertake something in the measurable future”; he told his troops that such an attack would be a grim business and urged them to do their duty. A month earlier, on 10 July, Headquarters 81st Corps had told the 302nd Division that the C-in-C West had ordered precautions because of the Russians’ reverses and the fact that they were believed to be “again” demanding of the British Government the establishment of a Second Front. It added that there was no information of actual preparations for an attack, but that the Division was nevertheless to be brought up to full strength forthwith.33 Moreover, its establishment was increased, to provide for manning additional weapons.34 These decisions had considerable effect before the raid. The 302nd received two drafts of untrained reinforcements (1353 and 1150 men) on 20 July and 10–12 August respectively, and it had no personnel deficiencies on 19 August.35 Other divisions on the coast were similarly reinforced.36

There were repeated alarms during the spring and early summer. There was a report, for instance, that a raid on Dieppe was planned for 6 April37 (at a time when, it would seem, the raid was only beginning to be considered in London). On 3 July the Commander-in-Chief West issued an order declaring, “It is our historic task to prevent at all costs the creation of a ‘Second Front’”. All commanders of strongpoints and defended areas were now to be sworn to defend their positions to the last.38 Accordingly, on 6 July, in the presence of all officers down to the rank of captain, the commander of the Defended Area Dieppe was solemnly sworn to defend his charge to the death.39

It is interesting that the records of the 302nd Division for the weeks of August immediately preceding the raid are devoid of the references, so frequent earlier, to agents’ reports of forthcoming landings.

Our Information About the Enemy

Our own intelligence concerning the enemy’s defences and dispositions was on the whole excellent. Thanks to our efficient air reconnaissance, there was not much we did not know about the defences of the Dieppe area. Field Marshal von Rundstedt in fact later commented upon the high quality of our maps, and one of the lessons he drew was the importance of constructing dummy positions.40 The 81st German Corps, however, truly observed that while our information on the defences was accurate, intelligence of types more difficult to obtain from air photographs was less complete: “There was a general lack of knowledge as to the location of regimental and battalion command posts”.41 Other information not easily available

from air reconnaissance was also lacking; notably, although our maps showed numerous pillboxes along the main Dieppe beach, there was no indication of their armament or of the presence of beach-defence or anti-tank guns. Fortunately, as we shall see, these antitank guns were too light to have much effect on Churchill tanks.

Our intelligence staffs made one curious error; luckily, it too had no influence on the operation. Our information before the raid was that the 302nd German Infantry Division had been relieved in the Dieppe area by the 110th, thought to be of higher category.42 This was quite inaccurate, for the 110th Division was not in the West at all; indeed, it seems to have served on the Russian front throughout the war.43 How this mistake came to be made remains a mystery. The other notable slip of our intelligence – the failure to observe the move of the 302nd Division’s headquarters from Arques-la-Bataille to Envermeu – has been commented upon above.

The Collision with the German Convoy

The senior officers concerned with Operation JUBILEE had emphasized in their comments on the plan that all such operations are greatly at the mercy of fortune. JUBILEE ran into bad luck at a very early stage, in the form of an accidental collision with enemy vessels about one hour before the first landings.

The report of the German Commander-in-Chief West tells us44 that a German convoy bound for Dieppe sailed from Boulogne at 8:00 p.m. on 18 August. It consisted of five motor or motor sailing vessels protected by two submarine-chasers and a minesweeper. As this little group (which would certainly not have sailed if the Germans had known of our enterprise) moved slowly down the coast, its movements were reflected on radar screens in England. The Commander-in-Chief Portsmouth accordingly sent out two warning signals (at 1:27 and 2:44 a.m.) reporting the presence of small craft. These had no effect, although they were received by at least some of the vessels of our force. They are not mentioned by the Naval Force Commander in his report; and even had he received them it is not clear what action he could have taken without breaking wireless silence and thereby prejudicing the whole operation. It appears that the warnings were not heard by the destroyers Brocklesby and Slazak, which were acting as screening force to the eastward45 In any case, at 3:47 a.m. Group 5, the most easterly group of our force, ran into the enemy convoy.

Group 5 consisted of some 23 personnel landing craft carrying No. 3 Commando, whose task it was to assault the Berneval battery. They were escorted by a steam gunboat, a motor launch and a flak landing craft. In

the violent little naval encounter which now took place, Brocklesby and Slazak played no part, their senior officer (the Polish commander of Slazak) believing that the gunfire came from the shore. The British escort vessels were seriously damaged.46 One of the German submarine-chasers (No. 1404) became “a total loss”.47 But, more important, the craft carrying No. 3 Commando were completely scattered, some of them being damaged. The Berneval attack was thereby disrupted, and only seven of the landing craft landed their troops.

What was the effect of this unfortunate encounter upon the enterprise generally? It was widely assumed after the raid that it resulted in a complete “loss of surprise” which compromised the whole operation. Colour is lent to this by the report of the German 81st Corps, which says that as a result of the engagement “the entire coast defence system was alerted”. There is a similar remark in the report of the C-in-C West.48 Nevertheless, detailed analysis of the German documents, and collation of them with our own information, do not entirely support these statements.

The noise of the sea fight did cause immediate precautions at some places, at least, in the eastern part of the area to be attacked. In particular, the Luftwaffe men in charge of the radar equipment at Berneval manned their strongpoint within ten minutes of the fight beginning;49 from that moment No. 3 Commando’s attack had little chance of succeeding. No evidence has been found indicating when the defences at Puys were manned, though it seems possible that the Germans here were alerted at the same time. We do know, however, that the encounter had no practical effect in the central or western sectors. At Pourville our first wave of infantry landed without a shot being fired at them;* and the 302nd Division’s report indicates that in Dieppe itself the 571st Infantry Regiment did not actually order “action stations” (Gefechtsbereitschaft) until exactly 5:00 a.m., when it had already heard of the landing at Pourville a few minutes before. The Division ordered “action stations” one minute later.50 It is important to note that at 4:45 a.m. the Commander Naval Group West expressed to GHQ West the opinion that the affair was only a “customary attack on convoy”. Destruction of wireless equipment had prevented the convoy escort from making any report.51

All in all, we seem forced to the conclusion that the convoy encounter did not result in a general loss of the element of surprise. It did seriously impair our chances of success in the eastern sector off which the fight took place. To this extent it had an effect upon the operation as a whole, though in the absence of evidence as to its particular influence on the garrison of Puys it is difficult to say precisely how important that effect was,

* See below, page 369.

The landing at Puys did not actually take place until a few minutes after that at Pourville had led to a general alarm being given.

It is clear, of course, that there was great danger of surprise being completely compromised as a result of the convoy encounter, and the question has sometimes been asked, why was the operation not abandoned at this point? There were good and definite reasons.

The orders specified,52 “If the operation has to be cancelled after the ships have sailed the decision must be made before 0300 hours [3:00 a.m.].” This was the time planned for the infantry landing ships concerned with the flank attacks to lower their landing craft, which would immediately start in towards the beaches.53 In order to avoid the landing ships’ being detected by the German radar (which in fact gave the enemy no warning whatever)54 it was necessary to lower the craft some ten miles from the coast and allow almost two hours for the run-in. It was impossible to call off the operation at the time of the encounter with the convoy, which took place nearly an hour after the deadline fixed in the order, when the assault craft were well on their way to the beaches, and the infantry landing ships which had lowered them were already returning to England.

The planners, it is of special interest to note, had striven to provide against precisely the sort of misfortune which had now happened. The naval orders directed that wireless silence might be broken “By Senior Officer of Group 5 if by delays or casualties it is the opinion of the senior military officer that the success of the landing at YELLOW beach is seriously jeopardised”.55 But the Group Commander (Commander D. B. Wyburd) was quite unable to report, for in the fight his steam gunboat’s wireless equipment was destroyed, and wireless traffic congestion foiled a subsequent attempt to signal from a motor launch. The consequence was that the Force Commanders in Calpe, although sight and sound had told them that there had been some contact with the enemy, received no actual account of the clash until about 6:00 a.m.,56 when both the flank attacks and the frontal attack had gone in. The whole episode was a remarkable example of how, in war, the most careful calculations may be upset.

The Attack on the Berneval Battery

It is best to deal separately with the five different areas in which attacks were made, beginning with the extreme left, where our arrangements were disrupted as a result of the encounter with the convoy.

As we have seen, the craft carrying No. 3 Commando to Berneval were completely scattered. Most of them never reached the shore, and Lt. Col. Durnford-Slater, after reporting to General Roberts on the headquarters

ship off Dieppe, returned to England without knowing that any of his men had landed.57 In point of fact, however, seven of the 23 craft landed their troops. Thanks to these men’s determination, the attack on the Berneval battery was far more effective than might have been expected in the circumstances.

Part of No. 3 Commando had been ordered to land on “YELLOW I” beach, at Petit Berneval, east of the battery, and part on “YELLOW II” beach to the west of it. Commander Wyburd’s report indicates that, of the seven craft which touched down, six (five first and another later) landed their troops at “YELLOW I” under covering fire from the motor launch (ML 346). The five craft touched down at 5:10 a.m., 20 minutes late.58 The party landed here was unable to reach the battery which was the Commando’s objective. Heavy opposition was encountered immediately after landing. Not only did the German defenders outnumber the small force put ashore, but they were soon reinforced by the equivalent of three more companies commanded by Major von Blucher, the commander of the 302nd Division’s anti-tank and reconnaissance battalion. By about 10:00 a.m., after bitter fighting, this small portion of No. 3 Commando was overwhelmed. Perhaps 120 men had been landed at “YELLOW I” beach. The Germans claim to have taken 82 prisoners here.59

The group landed at “YELLOW II” had much better fortune, and its action shines like a star in the gloom which otherwise pervades the eastern flank beaches. Here a single craft, LCP(L) 15, commanded by Lieut. H. T. Buckee, RNVR, landed three officers and 17 other ranks of No. 3 Commando, the senior officer being Major Peter Young. Access inland from this beach was by a narrow gully. Undismayed by finding themselves alone on the French coast, and heartened by the fact that they had landed without being fired upon or apparently even observed, Young’s tiny party climbed up the gully and with magnificent effrontery advanced against the Berneval battery. To take it was out of the question, but the Commando men got within 200 yards and sniped at it for about an hour and a half, preventing the guns from firing against our ships. (A German artillery report indicates that between 5:10 and 7:45 a.m. the battery fired no shots, except some over open sights at the snipers, which we know to have been ineffective.)60 The battery was thus certainly neutralized for over two and a half hours; the actual period may well have been longer. Young and his men then withdrew without loss to the beach, where they were taken off by the same faithful craft that had put them ashore.61 The DSOs. which both Major Young and Lieut. Buckee subsequently received were well earned, for few more daring feats of arms were performed during this war. The Naval Force Commander wrote in his report, “In my judgment this was perhaps the most outstanding incident of the operation.”

The Attack on the Varengeville Battery

On the extreme right or western flank of the operation, No. 4 Commando, commanded by Lt. Col. Lord Lovat, was completely successful in its attack on the battery near Varengeville. The good fortune of this Commando, the only military unit engaged in the operation to capture all its objectives, was in curious contrast with the ill-luck encountered by No. 3 on the opposite flank.

Lord Lovat’s force amounted to some 252 all ranks, including a small party of United States Rangers. It was transported in the landing ship Prince Albert and put ashore in assault craft. The plan was to land on two beaches designated “ORANGE I” and “ORANGE II”; the former a very narrow beach at Vasterival, immediately north of the battery, the latter the eastern section of the much longer beach near Quiberville. The plan was for one party, 88 strong and commanded by Major D. Mills-Roberts, to land at Vasterival and engage the battery in front with mortar fire, while the main body under Lord Lovat landed at ORANGE II, made a detour and attacked it from the rear.62

This plan was carried out exactly as written. Major Mills-Roberts’ party reached the clifftop successfully, advanced upon the battery, and fired on it with small arms and a 2-inch mortar. At or about 6:07 a.m. charges stacked beside the German guns ready for use blew up. The Commando attributes the explosion to a bomb from the mortar, but the German accounts blame fire from low-flying aircraft.63 The battery never fired again.* It was kept under fire until 6:20 a.m., when, in accordance with the plan, RAF cannon fighters made a low-level attack upon it. Simultaneously, Lovat’s main party, having landed and moved inland successfully, attacked it with the bayonet. After a short fierce fight the positions were cleared and the garrison cut to pieces. Captain P. A. Porteous particularly distinguished himself. Although painfully wounded, he took command of a troop which had lost its officers and led it in the final rush across open ground swept by machine-gun fire. Again wounded, he continued to lead his men until the battery was taken. He was awarded the Victoria Cross.64

Lord Lovat’s force suffered about 45 casualties, including two officers and ten other ranks killed, but this loss purchased full success. The menace of the battery to our shipping off Dieppe was wholly removed, for its guns were blown up before the Commando withdrew according to plan about

* The Commando account is probably accurate, as the Air Force Commander’s report indicates no air action against the battery at this time. A report from the 81st Corps, logged by Headquarters C-in-C West at 9.03 a.m., to the effect that the battery was firing again with two guns, is quite unsupported by other evidence and is probably an error. The 81st Corps report includes in its list of German material lost six 150-mm. coast defence guns, i.e. the battery’s full complement.

7:30 a.m. No. 4 Commando’s action is a model of boldness and effective synchronization.

At 8:50 a.m. Lord Lovat reported to the headquarters ship and the Chief of Combined Operations. The signal to the latter ran: “Every one of gun crews finished with bayonet. OK by you?”65 Actually, not quite the whole of the German unit had been liquidated, but it had suffered very heavily. Its strength is variously stated as from 93 to 112 men; its losses, which vary only slightly in different German accounts, were about 30 killed and 30 wounded66 – a proportion which reflects the use of the bayonet. Four prisoners were taken back to England.

Disaster at Puys

The bad luck of No. 3 Commando on the extreme left extended to the Canadian unit closest to it: The Royal Regiment of Canada at Puys. The beach here, and the gully behind it in which the little resort village lay, were both extremely narrow and were commanded at very short range by lofty cliffs on either side. Success depended entirely upon surprise and upon the assault being made while it was dark enough to interfere with the aim of the German gunners. Neither of these conditions was achieved. The German garrison at Puys was only two platoons, one of the army and one of the Luftwaffe, plus some technical personnel;67 nor does it appear to have been reinforced during the morning. In the circumstances, it was quite enough for the work in hand.

The Royal Regiment of Canada had attached to it three platoons of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, and detachments of the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment and the 4th Field Regiment, RCA The artillerymen were to assist in capturing enemy guns in the area and subsequently to man them. The Royals’ general task is best described in the words of the Combined Plan:

The Royal Regiment of Canada at BLUE beach will secure the headland east of JUBILEE [Dieppe] and destroy local objectives consisting of machine gun posts, heavy and light flak installations and a 4 gun battery south and east of the town. The battalion will then come into reserve, and detach a company to protect an engineer demolition party operating in the gas works and power plant.

This task was of special importance, since if the East Headland was not cleared the numerous weapons there would be able to fire on the main beaches in front of Dieppe.

Although the Detailed Military Plan does not assist us, and none of the Canadian infantry units issued separate written orders, individuals in positions to know68 state that the Royal Regiment was to land in three waves: the first to consist of three companies and an advance group of battalion

headquarters; the second, consisting of the remaining rifle company and the balance of the headquarters, to land ten minutes later; while the third, formed mainly of the attached platoons of the Black Watch, was to go in when signalled by the force already landed.

Unfortunately, the naval landing arrangements for BLUE Beach went awry. No operation of war is harder than landing troops in darkness with precision as to time and place, and the danger of reckoning upon exactitude in such matters was well illustrated at Dieppe. The Royals were carried in the landing ships Queen Emma and Princess Astrid, while the Black Watch detachment was in the Duke of Wellington. (The last-named ship’s landing craft flotilla was almost entirely manned by Canadian sailors, and a Canadian officer, Lieut. J. E. Koyl, RCNVR, took command of it after the Flotilla Officer was wounded.)69 There was delay in forming up after the craft were lowered from the ships; this was mainly, apparently, the result of Princess Astrid’s craft forming on a motor gunboat which, having got out of station, was mistaken for the one which was to lead them in.* The Flotilla Officer of Queen Emma states that the delay made it necessary to proceed at a greater speed than had been intended, and as a result the two mechanized landing craft (LCM) which formed part of this ship’s flotilla, and were carrying 100 men each, could not keep up. Ultimately, according to this officer, these two LCMs, with four assault craft which had been astern of them, landed as a second wave. In fact, one of the LCMs developed engine trouble and consequently touched down in due course quite alone.70

Thanks to these mischances, the first group of craft carrying the Royal Regiment struck the beach late. The situation is thus described in the record of a conference held on 13 September 1942 by the senior Canadian officers confined in Oflag VIIB, one of whom was Lt. Col. Catto of the Royals:

Only part of three leading assault companies were landed in first wave and these were brought 35 minutes late by Navy. Remainder of companies finally reached beach nearly one hour late. Effect of darkness and smoke screen entirely lost.

Princess Astrid’s Flotilla Officer states that touchdown was at 5:07 a.m., which would make it 17 minutes late. The time given by the Oflag VIIB conference is only one of many widely varying estimates made by Army officers and men. On a point of this sort it seems best to accept the naval evidence, the more so as that of the Germans agrees with it pretty closely: their 302nd Division gives the time of the first landing as 5:10. Whatever

* Lt. Col. Catto remembers a flare being dropped by an aircraft at this point. This is not mentioned by Queen Emma’s Commanding Officer or in any other naval report. Certainly no warning reached the Germans at this time.

the exact time, the unit was certainly placed upon the beach so late as to make its task far more difficult than it would have been at 4:50.

The defenders of BLUE Beach were fully on the alert. Fire was opened upon the leading craft while they were still well offshore; the Princess Astrid Flotilla Officer estimates that it began when they were “about 100 yards from the beach”. He states that Major G. P. Scholfield, the senior officer of the Royals with the first wave, was slightly wounded before landing. All accounts agree, moreover, that as this wave touched down and the craft dropped their ramps machine-gun fire was greatly intensified and heavy casualties were suffered immediately. The Flotilla Officer says, “In several cases officers and men were wounded or killed on the ramp as they made to leave the boats.”71

At the head of the Puys beach was a sea-wall ten or a dozen feet high, covered with heavy barbed wire. The wire’s presence had not been detected before the operation, but Lt. Col. Catto, suspecting it, had seen to it that the unit had “Bangalore torpedoes” for blowing paths through such obstacles.72 Survivors of the Royal Regiment and enemy documents both testify that the German defence was concentrated upon the east cliff.73 A brick house which stood here had in its front garden a concrete pillbox disguised as a summer-house, whose main slit had a murderous command of the beach and the sea-wall at very short range.74 This “LMG bunker” (which bore bullet-marks when examined in 1944) was probably responsible for a great number of the Royals’ casualties on the beach. It and other positions enfiladed the sea-wall, and caused heavy losses among the men who ran forward from the boats to take shelter there.

Although several Bangalore torpedoes were exploded on the wall to cut the wire, very few men succeeded in passing through the gaps alive. The combination of the absence of surprise with the fact that the assault was made in much broader daylight than had been intended had been fatal to the BLUE Beach attack. In the words of Capt. G. A. Browne, the artillery Forward Observation Officer attached to the battalion, “In five minutes time they were changed from an assaulting Battalion on the offensive to something less than two companies on the defensive being hammered by fire which they could not locate”.75

The second group of craft seems to have landed some twenty minutes later than the first; Canadian and naval estimates of the time vary from 5:25 to 5:35 a.m.76 Capt. Browne, who was in this group, has described77 the bearing of the men during the approach and the landing; he and those with him had been intended to land with the first wave, and they did not realize that in fact other troops had gone in before them:

In spite of the steady approach to the beach under fire, the Royals in my ALC appeared cool and steady. It was their first experience under fire, and although I watched them closely, they gave no sign of alarm, although first light

was broadening into dawn, and the interior of the ALC was illuminated by the many flares from the beach and the flash of the Bostons’ bombs. The quiet steady voice of Capt. [W. B.] Thomson, seated just behind me, held the troops up to a confident and offensive spirit, although shells were whizzing over the craft, and [they] could hear the steady whisper and crackle of S.A. [small arms] fire over the top of the ALC. At the instant of touchdown, small arms fire was striking the ALC, and here there was a not unnatural split-second hesitation in the bow in leaping out onto the beach. But only a split-second. The troops got out onto the beach as fast as [in] any of the SIMMER* exercises, and got across the beach to the wall and under the cliff.

This second wave of assault, in the circumstances, could accomplish nothing; it simply added to the number of men sheltering on the beach and being pounded by the German machine-guns and mortars. The landing of the third wave proved equally useless. No signal having been received, and no information concerning the situation ashore being available, Lieut. Koyl, in charge of Duke of Wellington’s flotilla, and Capt. R. C. Hicks, in command of the troops, jointly took the decision to land. At Hicks’ request, the Black Watch company was put ashore under the cliff to the west of the sea-wall, where the main body of survivors of the earlier waves were gathered.78 Virtually every man of the Black Watch who landed ultimately became a prisoner; one officer was killed.

The men on the beach were cheered by close and constant air support. Aircraft went in at clifftop level to lay smoke, and in Colonel Catto’s words, “The fighters came in again and again on the batteries while our show was on and later continued their close attacks while the withdrawal was taking place, and they undoubtedly affected quite seriously the fire from the east headland.” Only one small party of the Royals is definitely known to have got off the beach.† This was not long after 6:00 a.m. The party, numbering about 20 officers and men, was led by Lt. Col. Catto himself. They cut a path through the wire at the western end of the sea-wall, and the colonel led them up the cliff between bursts of machine-gun fire. They cleared two houses on the clifftop, “resistance being met in the first only”. The Germans now brought intense fire to bear upon the gap in the wire, and no more men got through it. The colonel’s party moved westward above the beach in the hope of making contact with the Essex Scottish; but this battalion had never got off the beach in front of Dieppe. Catto’s group lay up in a small wood until it was obvious that the men left on the Puys beach had been overwhelmed, that the landing force had withdrawn and that there was no hope of being taken off. At 4:20 p.m., after equipping a number of active unwounded men with “escape kits” and sending them off

* The code name applied to the special training for the operation.

†Nevertheless, the report of the German 302nd Division, after mentioning what is evidently Catto’s party, adds, “An additional 25 men, suffering losses, scrambled through the wire entanglements reinforced with mine charges; they are annihilated at 0815 hours [7:15 a.m. BST] by assault detachment of 23 (Heavy) Aircraft Reporting Company.”

in the hope – which proved illusory – that some of them might get clear, the party surrendered.79

In the face of the German artillery fire (a troop of four howitzers in position only a few hundred yards south of Puys fired 550 rounds during the morning at craft offshore)80 it was impossible to organize any systematic evacuation of the beach, although valiant attempts were made by the Navy. Analysis of the naval reports seems to indicate that the only craft which actually touched down on BLUE Beach for the purpose of re-embarking troops was LCA 209, commanded by Lieut. N. E. B. Ramsay, RNVR Many soldiers made a rush for it under heavy fire, and, overloaded and badly holed, it capsized not far offshore. Lieut. Ramsay was among the killed.81 Several men clung to the bottom, and two of Duke of Wellington’s landing craft, largely manned by Canadians, pushed in through a hail of missiles and rescued at least three of them, at the cost however of two or more sailors’ lives.82

As was inevitable in the circumstances, it is difficult to build up from the naval reports a completely coherent picture of the attempts to evacuate the Royal Regiment. It is clear, however, that Lieut. Commander H. W. Goulding, Senior Officer BLUE Beach Landings, visited HMS Calpe shortly after 7:00 a.m. He did not know what was happening on shore, but reported that the Royals had been duly landed. While he was in the headquarters ship a signal arrived, passed through HMS Garth, operating off BLUE Beach. This untimed message, apparently the only one from Garth to Calpe which has been preserved, reads: “From BLUE Beach: Is there any possible chance of getting us off”.83 Goulding recorded that he was now ordered by the Naval Force Commander “to take an M.L. [motor launch] for close support and make an attempt to evacuate BLUE Beach”. This was done accordingly, but when Goulding approached the beach heavy fire opened and no craft reached the shore.84 A signal, sent by him, was logged at 11:45 a.m.: “Could not see provision [? position] BLUE Beach owing to fog and heavy fires from cliff and White House. Nobody evacuated.”85 At least one further attempt was made, this time by four craft from Princess Astrid, whose Flotilla Officer reported that “Fire from the beach was still terrific”, one craft was sunk, and “there was no sign of life on the beach”.86

In point of fact, the remnants of The Royal Regiment of Canada on the Puys beach had probably surrendered a little before 8:30 a.m., rather more than three hours after the first landing. At 8:35 the 571st German Infantry Regiment informed its divisional headquarters, “Puys firmly in our hands; enemy has lost about 500 men prisoners and dead”.87

Very few men of the Royals returned to England: all told, two officers and 65 men. Practically all of these were in one craft – that LCM which,

as described above, had had engine trouble and touched down independently. It pulled back off the beach under murderous fire, only a few men having landed from it and many having been hit on board.88

The episode at Puys was the grimmest of the whole grim operation, and the Royal Regiment had more men killed than any other unit engaged. Along the fatal sea-wall the lads from Toronto lay in heaps.89 The regiment’s fatal casualties, including those who died of wounds and 18 who died from any cause while prisoners of war, amounted to 227 all ranks out of 554 embarked. And there is no doubt that the setback at Puys had a most adverse effect upon the raid as a whole, for, as we noted, failure to clear the East Headland was certain to make success in the centre much less likely. The Naval Force Commander reports, “There is little doubt that this was the chief cause of the failure of the Military Plan”. It certainly had great influence.

Some indication has already been given of the inadequacy of the information concerning events at BLUE Beach which reached the headquarters ship during the early stages. Indeed, this extended to the whole of the eastern beaches, for we have seen that the Force Commanders got no reliable account of what had happened to No. 3 Commando for more than two hours after its encounter with the German convoy. Information about Puys should have been better, for though the only wireless set working on the beach was that of Capt. Browne, the Forward Observation Officer, he was in communication with the destroyer Garth offshore. Garth’s commander confirms that the ship was in touch with Browne from 5:41 to 7:47, “during which time he was held up at the foot of the cliff and most messages received concerned wounded and the fact that they were held up, which were passed to CALPE”.90 The tragic fact is, however, that none of the early messages reached the headquarters ship. The Intelligence Log maintained in Calpe notes at 5:50 a.m. that there is no word from the Royals; and the first definite statement recorded concerning BLUE Beach is at 6:20 and is extremely inaccurate: “R. Regt C. not landed”. Another version appears in the Fernie Intelligence Log at 6:25, “Impossible to land any troops on BLUE Beach. From Navy”. This is probably a garbled version of an untimed message recorded as received by the Naval Force Commander from the Puys naval beach station: “Impossible to land any more troops on BLUE Beach”. It presumably came from the Beachmaster, who had not succeeded in getting ashore. In any case, the Force Commanders were long left in the belief that the Royal Regiment had not been landed; and as a result of this General Roberts sent out to the Royals, at 6:40 a.m. or a little before, an order directing them to go to RED Beach to support the Essex Scottish.91

The Fighting in the Pourville Area

The units landed on “GREEN Beach”, at Pourville to the west of Dieppe, had better fortune, on the whole, than any other Canadian troops in the operation. Nevertheless, this success was only comparative, for they attained but few of their objectives.

The Pourville beach, though much longer than that at Puys, is still dominated by cliffs on both sides. Standing in the village of Pourville and looking east towards Dieppe, one faces a lofty and forbidding rampart, the eastern ridge of the valley of the Scie. This obstacle, strongly held by the Germans, proved insuperable on the morning of 19 August 1942.

The South Saskatchewan Regiment was carried across the Channel in the landing ships Princess Beatrix and Invicta. The trans-shipment to landing craft and the approach to the beach went without a hitch, and the craft touched down within a very few minutes of the time planned (4:50 a.m.); the two ships’ Flotilla Officers agree in fixing the time at 4:52. A considerable measure of surprise was achieved. The naval reports indicate that there was no fire as the boats ran in, although it began very soon after the landing. One craft which touched down two minutes late on the extreme right flank was fired upon and the soldiers in it suffered casualties as they disembarked.92 The whole unit landed as one wave. This was the earliest actual landing of troops in this operation, except perhaps for those of No. 4 Commando on the same flank; we have seen that both the eastern landings, though timed to take place simultaneously with that at Pourville, were considerably delayed.

One misfortune during the disembarkation, however, had considerable effect upon events. The River Scie flows into the Channel near the middle of the Pourville beach, and the intention had been to land the battalion astride the river, so that the companies operating against the objectives east of it could deliver their attacks without having to seek a crossing. Although there is no reference to this in the naval reports (indeed, the officers of the landing craft may have been unaware of the fact), accounts by officers and men with The South Saskatchewan Regiment93 leave no doubt that in the semi-darkness the craft had not been able to strike the precise parts of the beach intended, and almost the whole of the battalion was actually landed west of the river. This meant that the companies having the vital task of seizing the high ground to the eastward had first to penetrate into the village and cross the river by the bridge carrying the main road towards Dieppe. The delay thus caused nullified the effect of the surprise that had been obtained, and was probably fatal.

“C” Company, operating to the west of Pourville, promptly occupied all its objectives, including positions on the hills immediately south-west of the village, and killed a good many Germans in the process. The companies

working to the eastward had no such success. “A” Company’s objective was the radar station on the cliff-edge roughly a mile east of Pourville. “D” Company’s was positions on the adjacent high ground to the southward, including Quatre Vents Farm and antiaircraft guns nearby; it was expected that they would be helped by The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and a troop of tanks arriving from Dieppe. Before these two companies, having been landed west of the Scie, could get across the bridge and reach the heights, the enemy’s posts there were manned and firing. The eastern part of the village, and the bridge, were completely dominated by them. Soon the bridge was carpeted with dead and wounded men and the advance of the South Saskatchewans came to a halt.

At this point, Lt. Col. Merritt, having established his headquarters near the beach, came forward and took charge himself. Walking calmly into the storm of fire upon the bridge, waving his helmet and calling “Come on over – there’s nothing to it”, he carried party after party across by the force of his strong example. Other men forded or swam the river.94 The Colonel then led a series of fierce uphill rushes which cleared several of the concrete positions commanding bridge and village.* Nevertheless, in spite of his extraordinary energy and dauntless courage, and the best efforts of his men and of the Camerons who were shortly mingled with them, the posts on the summit, including the trench system of Quatre Vents Farm and the radar station, could not be taken. Apparently some of our men got within a short distance of the radar station, but it was heavily wired and defended and could not be dealt with without artillery support.95 The enemy handled his mortars and machine-guns skilfully, and our thrusts were all beaten back. One party actually reached the edge of the Quatre Vents position and killed several Germans before being forced out.96 Attempts to obtain artillery support from the destroyer Albrighton were nullified by the Forward Observation Officer’s inability to observe and lack of knowledge of the exact positions of our own troops; he did indicate several targets, but was unable to spot the fall of the ship’s shells.97

The Cameron Highlanders of Canada, who were to pass through the Pourville bridgehead and operate against the aerodrome in conjunction with the tanks from Dieppe, were landed about half an hour late. This was due in part at least to the wishes of Lt. Col. Gostling, who, according to Commander H. V. P. McClintock, the naval officer in charge, “preferred to arrive late [rather] than early”. The idea (a dubious one) apparently was to land ten minutes later than the plan provided; however, miscalculations of

* The following information was logged by the 302nd German Division at 8.00 a.m. (7.00 a.m. British time): “At Pourville-East 4.7-cm. anti-tank gun position is overrun by enemy. Anti-tank gun unable to continue fire due to jamming of loophole, crew is killed. Enemy advances on height up to orderly room of 6th Company 571st Regiment, is held here. One beach-defence gun and one heavy machine-gun put out of commission.”

speed and course lengthened the delay, and the battalion touched down at 5:50 a.m.98 During the approach, it was apparent that the South. Saskatchewans had not succeeded in opening up their bridgehead in the manner expected; fighting was clearly in progress in the outskirts of Pourville, and shells were bursting in the water offshore. With the Camerons’ pipers playing, the craft pushed on; all of them reached the beach and there were almost no casualties on board. As Lt. Col. Gostling’s own craft ran in, he was calling cheerfully to his men, identifying the types of fire that were coming down upon them. When the boat touched down, near the east end of GREEN Beach, he leaped on to the shingle and went forward to direct the cutting of wire. Fire immediately opened from a pillbox built into the headland on the left, apparently the one position closely covering the beach which the South Saskatchewans had not succeeded in clearing; and the Commanding Officer fell dead.99 The second in command, Major A. T. Law, took over.

The battalion had been landed astride the Scie, and mainly as a result of this it became divided into two main sections. The larger, which had landed west of the river, consisted of “A” Company, two platoons of “B”, and evidently the major part of all three platoons of “C”. This main body under Major Law subsequently moved inland and effected the deepest penetration made by any portion of the force engaged that day. The rest of the battalion remained in the Pourville area and fought in parties of varying strength mingled with The South Saskatchewan Regiment.100

Pourville was under heavy mortar fire, and this, plus the lateness of the hour, made it desirable that the battalion should move inland as rapidly as possible. It was clear that although the original plan had provided for an advance up the east bank of the Scie and a rendezvous with the tanks from Dieppe at the Bois des Vertus, the South Saskatchewans had not made enough progress for this to be practicable. However, an alternative route, up the west bank, had been planned in case of need, and this Major Law now adopted.101 He debouched from Pourville with his main body at a time which was not recorded.

At first the battalion followed the main road; then, coming under machinegun fire from the direction of Quatre Vents, it bore to the right to take advantage of the cover of the woods on the heights overlooking the Scie. It continued to be harassed by German snipers, and would seem to have advanced slowly. After penetrating roughly a mile and a half from Pourville, it moved left again towards the hamlet and bridges of Petit Appeville (Bas de Hautot). Here Law hoped to cross the river and make contact with the tanks.102

Looking down on the crossings from the high ground west of the village, Law saw enemy forces beyond the river, including what appeared to be a bicycle platoon (we now know that a German cyclist platoon had been sent

at 5:30 to reinforce the ridge near Quatre Vents Farm).103 There was no sign of the Canadian tanks; none of them had, in fact, got beyond the Promenade at Dieppe. Law had no information beyond what he could see, and as time was getting short he resolved to abandon the attack against the planned objectives, and instead to cross the river and clear the Quatre Vents area. Orders to this effect were issued about nine o’clock. As the companies moved towards the road-bridge, there was contact with the enemy coming from two directions: a party moving south on the road from Pourville (probably a reconnaissance patrol of engineers which was operating in this area)104 and forces moving up from the south on the west bank of the Scie. Casualties were inflicted on both. The Germans, however, were establishing an increasingly firm hold on the area about the crossings. At 6:10 a.m. their 571st Infantry Regiment had sent an order by dispatch rider to its 1st Battalion, the regimental reserve in Ouville, to move to the Hautot area for an attack against Pourville. This unit in the course of assembling ran into the Cameron (a report of this contact was received by the German divisional headquarters at 9:55 a.m. from a staff officer who had been sent to the battalion). Law saw a detachment of horse-drawn close-support guns arrive from the south, cross one of the Petit Appeville bridges and take up a position on the east side covering the crossings. This was doubtless the infantry gun platoon “in process of formation” which is known to have been stationed at Offranville as part of the regimental reserve.105 Although its operations are not mentioned in the German documents, the 302nd Division’s administrative report speaks of two 75-millimetre infantry guns being in action during the day.

The Camerons’ 3-inch mortars having been knocked out in Pourville, they had no weapons capable of silencing these shielded guns at several hundred yards’ range. At the same time, they were under machine-gun and sniper fire from the high ground overlooking the crossings. Major Law now decided that it was not practicable to fight his way across the river. About 9:30 a.m. he gave orders for withdrawal. Immediately afterwards he heard that his wireless set had intercepted a message from Headquarters 6th Brigade to The South Saskatchewan Regiment advising of the intention to evacuate from GREEN Beach and adding, “Get in touch with the Camerons”. The message was understood as giving the time of evacuation as ten o’clock; thus a speedy retreat was essential. After sending a message telling the South Saskatchewans what he was doing, Law began his withdrawal by the route by which he had advanced. The unit retired under pressure. On the way it met a South Saskatchewan platoon which had been sent out to make contact with it, and the combined force re-entered Pourville just before ten.106

The penetration through Pourville was the most important effected during the day, and it was about this area that the Germans were most apprehensive.

The regiment in Corps Reserve was moved up in that direction and was about to attack when the operation came to an end.107 Moreover, as we shall see, the Germans’ intention was to employ the 10th Panzer Division in this area. There has been a tendency to criticize the Military Force Commander for not exploiting the advantage gained here; but the fact is that he knew nothing of the extent of the penetration. No reports about the Camerons’ progress appear in the headquarters logs during the period when they were inland.* All General Roberts knew was that they “had penetrated some distance inland and ... were out of wireless touch”.108 In any case, by the time they reached Petit Appeville it was too late to begin exploiting, and the infantry reserves had been expended elsewhere.

The plan had envisaged evacuating all the troops, in the event of success, through the town of Dieppe. In the circumstances actually existing, however, The South Saskatchewan Regiment and the Camerons had to be taken off from the same beach at Pourville on which they had landed. This decision was made and orders given about 9:00 a.m. The time fixed was 11:00 a.m., the same as for the main beach. The boats arrived on schedule, but the South Saskatchewans and the Camerons lost heavily during the withdrawal. The enemy was able to bring fierce fire upon the beach from his lofty positions east of Pourville, and also from the high ground to the west, from which “C” Company of the South Saskatchewan had retired as the result of a misunderstanding (the order from the headquarters ship for the battalion to withdraw and re-embark was apparently passed on to this company and understood by it as an executive order from the Commanding Officer, although it was not so intended).109 However, the landing craft came in through the storm of steel with self-sacrificing gallantry (one Cameron wrote afterwards, “The LMG fire was wicked on the beach, but the Navy was right in there”).110 The naval reports indicate that probably 12 assault landing craft, one support craft and one chasseur took part in lifting troops from GREEN Beach. In this task at least four, and probably five assault craft were lost.111 Several larger vessels gave fire support.

The enemy’s troops, who showed little stomach for really close fighting, were kept at arm’s length by a courageous rear guard commanded by Lt. Col. Merritt. Throughout the day, Merritt had been in the forefront of the bitter struggle around Pourville, exposing himself recklessly and displaying an energy almost incredible (“It wasn’t human, what he did”, said an officer who was with him).112 Thanks to Merritt’s group, the greater part of both units was successfully re-embarked, though many of the men were wounded. The rear guard itself could not be brought off. It held out on the beach until ammunition was running low and there was no possibility of evacuation

* The narrative in the Camerons’ war diary states, “We were unable to contact Bde. HQ at any time during the advance inland and subsequent withdrawal, and it was not until approximately 1005 hrs when we returned to Pourville that this was accomplished.”

or of doing further harm to the enemy. At 1:37 p.m. the 571st German Infantry Regiment reported, “Pourville firmly in our hands”.113 Lt. Col. Merritt subsequently received the Victoria Cross.

The fatal casualties suffered by the Camerons and The South Saskatchewan Regiment were respectively six officers and 70 other ranks, and three officers and 81 other ranks.

The Frontal Attack on Dieppe

The frontal attack on Dieppe was to be delivered by The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry on the right and the Essex Scottish on the left, with the nine leading tanks of the 14th Army Tank Regiment landing simultaneously with the first infantry. The assault was to be covered by the 4-inch guns of the destroyers and Locust; and close-support fighter aircraft were to attack the beaches, the buildings overlooking them and the gun positions on the West Headland “as the landing craft finally approach and the first troops step ashore on RED and WHITE beaches”.114 There was no hope of surprise here, for the flank landings were scheduled for half an hour earlier; and we have seen that the alarm was given in Dieppe, following the Pourville landing, 20 minutes before the main assault.

The RHLI and the Essex Scottish were carried across the Channel in the landing ships Glengyle, Prince Leopold and Prince Charles. The landing craft were lowered and made their approach without untoward incident,* and the infantry units touched down on the long beach in front of Dieppe’s Promenade – dedicated once to idleness and pleasure – at the exact time appointed or within a minute or two of it.

The naval orders called for intense direct bombardment by four destroyers and Locust from the time when the landing craft were one mile from the beach until they touched down. These were carried out, except that Locust did not participate; she had been unable to keep up during the passage.115 The Air Force also played its part precisely as planned. Smoke was laid to screen the East Headland; and at 5:15 a.m. five squadrons of Hurricane fighters made a cannon attack upon the beach defences.116 This was ending just as the Essex Scottish and The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry leaped from their assault craft and began to scramble through the wire obstacles towards the town. All witnesses117 agree that the Hurricane attack

* Lt. Col. Labatt states that shells fell near HMS Glengyle while craft were being lowered; and, doubtless on the basis of his report, the conference of Commanding Officers at Oflag VIIB on 13 Sep 42 recorded that “infantry assault ships... came under fire by 0340 hours from shore batteries”. But the German documents disprove this, and the report of Glengyle’ss Commanding Officer makes it clear that the firing was that resulting from Group 5’s encounter with the German convoy. He writes, “...heavy fire from guns of light calibre was observed (0350) bearing 130’ – the direction of YELLOW landing – and a few ‘overs’ of no importance burst near the ship”.

was excellently timed and most terrifying. It was planned to cease at 5:25, and its effect was of course purely temporary. Naval estimates of the time the first landing craft touched down vary from 5:20 to 5:23;118 they may thus have been up to a couple of minutes late. If so, the troops were to this extent less able to profit by the air attack.

There was, however, a more serious error in timing. The three craft carrying the first nine tanks “approached from too far to the westward and were about 10 to 15 minutes late in touching down”.119 During this period, between the cessation of the naval and air bombardment and the tanks’ arrival, there was no support for the infantry; and the enemy, recovering from the Hurricane attack, was able to sweep the beaches with fire. This happened so rapidly that our infantry were pinned down before they could get through the wire obstacles, climb the sea-wall and cross the broad Promenade into the town. In any opposed landing, the first minute or two after the craft touch down are of crucial importance; and it may be said that during that minute or two the Dieppe battle, on the main beaches, was lost. The impetus of the attack ebbed quickly away, and by the time the tanks arrived the psychological moment was past.

The enemy had been firing upon the landing craft as they approached the shore. Some reports suggest a temporary slackening at the moment of landing, possibly the result of the Hurricanes’ blow, but it was followed immediately by an intensification of machine-gun and mortar fire.120 Officers of the RHLI state that “D” Company, which was on the right closest to the West Headland, was almost wiped out immediately after landing.121 It had, in fact, suffered heavily while still afloat. Two craft, both apparently carrying platoons of this company, were reported lost. A responsible naval officer122 states that both were “heavily damaged during the approach but touched down; this seems likely, though an Army witness doubts whether they reached the beach.123

At the west end of the Promenade, in front of the town, stood the large isolated Casino. The Germans, we have seen, had begun to demolish it, but only the south-west wing had, been destroyed before the raid. The building, and pillboxes and gun emplacements near it, were occupied by the enemy, and clearing them took time and cost lives; but the RHLI shortly broke into the Casino and rounded up the snipers. “Nearly an hour was needed before all the enemy were either killed or taken prisoners.124 In this work Lance-Sergeant G.A. Hickson, RCE, leading the survivors of a demolition party whose assigned task was the destruction of the telephone exchange, distinguished himself.125 At 7:12 a.m. a report that the Casino had been “taken” was logged on the headquarters ship; this may indicate when the clearing process was completed.

The Casino constituted a sort of covered avenue between the beach and the Boulevard de Verdun, the street skirting the front of the town. Thanks largely to this fact, at least one party of the RHLI and another led by a Sapper sergeant were able to get into the town and remain there for some time.

The first party to enter seems to have been a group of about 14 men under Capt. A.C. Hill. This officer led it from the beach into and through the Casino at about six a.m., when our troops had entered the building but not yet cleared it. Covered by Bren gun fire, they ran across the open to the buildings on the front of the town and broke into one which let them into a theatre, through which in turn they got into the town. They circled through several streets, engaging enemy patrols and losing one man killed. Encountering increasingly heavy opposition, they fell back to the theatre, where they were joined by some other men of our force. About ten in the morning, when enemy infantry were seen converging on the theatre, the whole party retired to the Casino, only one man being hit during the rush across the open.126

At a fairly late hour in the morning Lance-Sergeant Hickson took a party of about 18 men into the town,* profiting by the fire of one of our tanks which had stopped near the south-east corner of the Casino and had silenced some of the machine-guns in and around the lofty Castle on the West Headland. The party had trouble with snipers and cleared one house held by German infantry before withdrawing to the Casino towards noon.127 Hickson was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

On the Essex Scottish beach there was no such feature as the Casino to facilitate infiltration. It was completely open and was commanded by both headlands as well as by the high buildings in front. We have mentioned the French tank dug in near the base of the west mole; and on the mole itself there was a pillbox mounting an anti-tank gun. These two positions remained in German hands throughout the operation, though the enemy records that the one on the mole “suffered a direct hit”, possibly from naval fire.128

The only party of the Essex Scottish known to have got into the town was led by C. S. M. Cornelius Stapleton. Only a few minutes after the first landing, this stout Warrant Officer led a dozen or so men across the fire-swept Promenade into the buildings fronting the Boulevard de Verdun.†

* A narrative written by Capt. WD Whitaker states that another party of the RHLI, led by Lieut. L. C. Bell, also penetrated into the town. In the opinion of Lt. Col. Labatt, this is an error. Lieut. Bell himself was killed during the operation. The present writer however thinks it probable that another party got into Dieppe in the RHLI area. The German 302nd Division records at 7:45 the capture of a “British assault detachment... near Dieppe city hall” (not far from the Casino); and a careful French observer, M. Georges Guibon, relates what seems to be the same incident.

†How fierce the fire was is indicated by the evidence of a soldier129 who was one of a group who crossed the Promenade at this time and joined Stapleton in the buildings. He testified that of about nine men in his group only two reached the houses.

The party killed a number of enemy snipers in the buildings and subsequently penetrated through the streets to the harbour. It “accounted for a considerable number of enemy in transport and also enemy snipers”130 before being overpowered; its action is doubtless reflected in a German report logged at 8:16 a.m., that the enemy had been thrown back “from the harbour station (100 metres from the beach)”.131 CSM Stapleton got back to the beach and reported to Colonel Jasperson. In due course he received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.