The Canadians in Italy 1943–1945

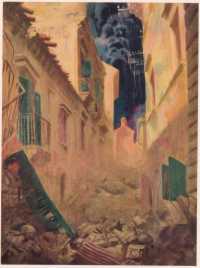

Ortona

From a painting by Major C. F. Comfort. Troops of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade fight forward through a rubble-filled street towards the Church of St Tommaso, December 1943.

[This image was the book’s frontispiece]

Chapter 1: The Allied Decision to Invade Sicily

The Invitation for Canadian Participation in the Mediterranean Theatre

In the late afternoon of 23 April 1943, Lt-Gen. A. G. L. McNaughton, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, First Canadian Army, was called to the War Office for discussions with General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff. General Brooke immediately put forward a proposal of the highest import to Canada and the Canadian Army. For two hours General McNaughton examined the various aspects of the proposition, discussing these first with Sir Alan and then in turn with various high-ranking officers of the General Staff. When he left Whitehall, it was to go to Canadian Military Headquarters, in Trafalgar Square, where he transmitted to Ottawa the terms of the following formal written request which he had received.1

Lieutenant-General A. G. L. McNaughton, CB, CMG, DSO, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, First Canadian Army.

A decision has been reached by the War Cabinet to undertake certain operations based on Tunisia.

The Prime Minister has instructed me to enquire whether you will agree to Canadian forces participating, to the extent of one Canadian infantry division and one tank brigade together with the necessary ancillary troops.

As soon as you have obtained agreement of the Canadian Government for the employment of these forces will you please let me know. Full details of the requirement can then be worked out in consultation between your Headquarters and the War Office.

With respect to the command and control of Canadian troops participating in these operations I must make it clear that arrangements will be the same as those for the British formations which they are replacing.

A. F. Brooke, CIGS

National Defence Headquarters acted promptly, and within forty-eight hours of receiving General Brooke’s invitation General McNaughton had formally replied that he had been authorized by the Canadian Government2 to undertake the operation in question. He detailed for the purpose

the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, and certain ancillary units.

Thus was set in motion the train of events which eleven weeks later was to lead to a landing by Canadian soldiers on the beaches of Sicily in the first major operation by forces of the United Nations to open a breach in the European fortress.

The Casablanca Conference

The Allied decision to undertake “operations based on Tunisia” had been reached at Casablanca three months earlier. When, in mid-January, the Combined Chiefs of Staff met with Mr. Churchill and President Roosevelt, at Anfa Camp on the outskirts of the French Moroccan town to review the conduct of the war and determine basic strategy for the coming year, they were faced with the problem of how to employ Allied armies after the completion of the Tunisian campaign. A perceptibly brightening picture from the war fronts of the world gave evidence that the initiative was passing into Allied hands. During late October and early November in three momentous weeks the tide of Axis advances had been turned in as many sectors of the global struggle. The Russians had triumphed in the epic of Stalingrad and the Red Army was on the offensive; the British Eighth Army’s brilliant victory at El Alamein had driven the German and Italian Armies into their final retreat across the African desert; in the Pacific Axis aggression had been stemmed as Australian and American forces joined hands on New Guinea, and with Marine and Army lines holding on Guadalcanal a crushing Japanese defeat in adjacent waters blasted the enemy’s hopes of retaining that strategic island. On the north-west coast of Africa Allied forces had successfully carried out the greatest landing operation in history. It would appear that there were indeed good grounds for Mr. Churchill’s cautious message of encouragement, “It is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”3

At Casablanca, two months after El Alamein and the North African landings, there seemed assured the successful termination of the converging operations by General Sir Harold Alexander’s Middle East Forces and the formations under General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s command.*

Allied troops of three nations were closing in for the kill. To the east General Sir Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army, after a spectacular drive which in

* General Sir H. R. L. G. Alexander succeeded General Sir Claude Auchinleck as Commander-in-Chief Middle East Forces on 15 August 1942. On 14 August 1942 the Combined Chiefs of Staff appointed General Dwight D. Eisenhower Commander-in-Chief Allied Expeditionary Force, to undertake the “combined military operations ... against Africa”.4

three months had carried it 1400 miles from El Alamein, was at the gates of Tripoli. In the west, although the flow of Axis reinforcements and supplies across the Sicilian bridge from Southern Italy continued, the British First Army under Lt-Gen. K. A. N. Anderson (whose command included the United States 2nd and the French 19th Corps) had entered Tunisia from Algeria and was holding a stabilized line which restricted General Jürgen von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army to the sixty-mile wide coastal corridor.5 Field-Marshal Rommel was on the run across Tripolitania and, while the inevitable junction of his Afrika Korps with von Arnim’s command portended no ready relinquishment of the Axis’ Tunisian bridgehead, it was calculated that the end of April would see the end of enemy resistance on the African continent.6

There was not immediate agreement between the British and American Chiefs of Staff as to where and when the next blow should be struck. “It still would have been preferable”, wrote General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, “to close immediately with the German enemy in Western Europe or even in Southern France had that been possible of achievement with the resources then available to General Eisenhower. It was not.”7 When in July 1942 the British and American Chiefs of Staff had decided in London, at the prompting of both the Prime Minister and the President, to launch an attack against French North Africa as the only operation that could be undertaken that year with fair hope of success, they virtually accepted the fact that the demands of “Torch” (as the proposed assault was called) would so interrupt the build-up programme which was then in progress for a cross-Channel assault (Operation “Roundup”) as to postpone any invasion of North-West Europe until 1944 at the earliest.8 The decision was a momentous one, for not only did it disappoint the hopes of the United States War Department of developing at an early date an operation in what it considered the only decisive sector of the strategic front,9 but the introduction of American forces into the Mediterranean was to invite their full-scale commitment to the subsequent protracted operations in that theatre, which only ended north of the Po with the complete surrender of the German armies.

The British Chiefs of Staff, while agreeing that eventually Germany must be attacked across the Channel, pressed the argument that in view of the exceedingly doubtful prospects for a successful launching of “Roundup” in the summer of 1943, the logical scene of action was the Mediterranean, where conditions were, propitious for immediate operations. An offensive in this theatre could not be expected, it is true, materially to relieve German pressure on Russia. But neither might this be achieved otherwise. The arguments of the previous July retained their cogency, for the Allies were still in no

position to commit to a Second Front a force large enough (as requested by Mr. Molotov) to draw off 40 divisions from the Eastern battle front.10 Furthermore, the favourable turn of events after Stalingrad made direct aid to Russia no longer so pressing a consideration. Mr. Churchill reiterated the opinion expressed to President Roosevelt in the previous November:

The paramount task before us is first, to secure the African shores of the Mediterranean and set up there the naval and air installations which are necessary to open an effective passage through it for military traffic; and, secondly, using the bases on the African shore to strike at the under-belly of the Axis in effective strength and in the shortest time.11

In support of their case the British Chiefs of Staff pointed out that Axis-dominated territory in the Mediterranean presented so many potential targets for an Allied offensive that with proper deceptive measures it should be possible to worry the enemy into a widespread dispersal of his forces to meet threats against Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, the Dodecanese Islands and the coasts of Italy and Greece. Furthermore, once Italy had been knocked out of the war – for it was the British contention that this must be the prime objective of Mediterranean operations*

* On 24 November 1942 Mr. Churchill had cabled the President: “Our Mediterranean operations following on ‘Torch’ may drive Italy out of the war. Widespread demoralisation may set in among the Germans, and we must be ready to profit by any opportunity which offers.”12

– Germany would be forced to assume the defence of the Italian peninsula as well as to replace the Italian troops who were garrisoning the Balkans. Finally there was the possibility that a successful campaign in the Mediterranean might provide a strong inducement to Turkey to enter the war and so open the Black Sea supply route to Russia and provide the Allies with a base for operations against the Rumanian oilfields.

To the American Chiefs of Staff the British advocacy of an early offensive was convincing enough from a tactical standpoint, but General Marshall emphasized that such an exploitation of victory in Africa would at best be a temporary expedient, not to be considered as a change in the general strategy, previously agreed to by the Combined Chiefs, of defeating Germany by opening a Second Front in Northern France.13 Having made this point the Americans bowed to the demands of expediency in maintaining the momentum of the war against Germany, and agreed to the mounting of a Mediterranean operation. They reached this decision because, in General Marshall’s words, “we will have in North Africa a large number of troops available and because it will effect an economy in tonnage which is the major consideration.”14 He again emphasized that the American viewpoint regarding general strategy remained unchanged, declaring that “he was most anxious not to become committed to interminable operations in the Mediterranean. He

wished Northern France to be the scene of the main effort against Germany – that had always been his conception.”15 A similar interpretation of the American attitude has been given by General Eisenhower, who sets forth two reasons for the Casablanca decision to undertake the Sicilian operation: the opening of the Mediterranean sea routes, and the fact that “because of the relatively small size of the island its occupation after capture would not absorb unforeseen amounts of Allied strength in the event that the enemy should undertake any large-scale counteraction.”16

Having reached agreement as to the theatre in which operations would be launched, the Conference turned to the selection of the immediate objectives. Offensive action in the Western Mediterranean might be taken either directly against the mainland of Italy, or against one or more of the intervening islands of Sicily or Sardinia or Corsica. Decision on the invasion of Italy was deferred and the relative attractiveness of the three island targets was considered. Tentative planning of an assault against Sardinia as a sequel to Operation “Torch” had already engaged the attention of General Eisenhower’s staff,17 and in mid-November Mr. Churchill had directed the British Chiefs of Staff to consider the necessity or desirability of occupying the island “for the re-opening of the Mediterranean to military traffic and/or for bringing on the big air battle which is our aim.”18 The occupation of Sardinia and Corsica (it was considered that “the capture of Sardinia would have had a profound effect in the Mediterranean only if coupled with the immediate capture of Corsica”)19 would furnish an advantageous base from which to threaten the Italian peninsula along its entire western flank. On the other hand the possession of these northern islands without Sicily would not free to Allied use the Mediterranean passage, Axis control of which lengthened the convoy route to the Middle East by an enforced 12,000-mile detour around the Cape of Good Hope. (At a conference in Rome on 13 May 1943, Mussolini was to tell Admiral Dönitz that Sicily was in a greater danger of attack than Sardinia, and support his contention “by referring to the British press which had repeatedly stated that a free route through the Mediterranean would mean a gain of 2,000,000 tons of cargo space for the Allies.”)20

After an exhaustive examination of the respective claims of Sicily and Sardinia a firm decision was reached. On 19 January the Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed “that after Africa had been finally cleared of the enemy the island of Sicily should be assaulted and captured as a base for operations against Southern Europe and to open the Mediterranean to the shipping of the United Nations.”21 Four days later they furnished General Eisenhower with a directive which appointed him Supreme Commander and General Alexander his deputy. Admiral of the Fleet Cunningham was to be the

Naval Commander and Air Chief Marshal Tedder the Air Commander.*

* Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 21 January 1943, was appointed Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean on 20 February 1943, in command of all Allied naval forces in the Western Mediterranean (including Malta). An AFHQ General Order of 17 February 1943 designated Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur W. Tedder as Air Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean; his command comprised the Middle East Air Command (RAF), RAF Malta Air Command, and Northwest African Air Forces (US).

The operation (which was code-named HUSKY) was to have as its target date the period of the favourable July moon.22

Canada was not represented at the Casablanca Conference. The first official information concerning the proceedings there came to Prime Minister Mackenzie King on 30 January in a message from Mr. Churchill which enclosed “an account of the principal conclusions reached”. “I earnestly hope”, wrote the British Prime Minister from Cairo, “you will feel that we have acted wisely in holding this conference and that its general conclusions will commend themselves to you.” Mr. Churchill did not conceal his satisfaction at the decision to continue active operations in the Mediterranean.

Without wishing to indulge in any complacency I cannot help feeling that things are quite definitely better than when I was last in Cairo, when [the] enemy was less than 70 miles away. If we should succeed in retaining the initiative on all theatres, as does not seem impossible and if we can sincerely feel we have brought every possible division of soldiers or fighting unit of our forces into closest and most continuous contact with the enemy from now on, we might well regard the world situation as by no means devoid of favourable features. Without the cohesion and unity of advance of the British Empire and Commonwealth of Nations through periods of desperate peril and forlorn outlook, the freedom and decencies of civilised mankind might well have sunk for ever into the abyss.23

Sicily was not named in either Mr. Churchill’s covering note or in the accompanying summary, which was prepared by the Deputy Prime Minister, Mr. Clement Attlee; for it was “most important that exact targets and dates should not be known until nearer the time”. The message from Mr. Attlee alluded in only very guarded terms to the decision to mount Operation HUSKY:

Operations in the Mediterranean with the object of forcing Italy out of the war, and imposing greatest possible dispersal of German Forces will include

(a) clearance of Axis forces out of North Africa at the earliest possible moment,

(b) in due course further amphibious offensive operations on a large scale,

(c) bomber offensive from North Africa.24

In recording Mr. Churchill’s gratification that the invasion of Sicily had been agreed upon, it may be noted that some fifteen months before the Anfa meetings he had been a strong proponent of such a project. In the autumn of 1941, when there were high hopes that the impending offensive by the Eighth Army might drive Rommel back through Libya and Tripolitania, the British Chiefs of Staff were considering a plan – they

called it “Whipcord” – for exploiting victory in the Western Desert by an assault upon Sicily. For this purpose a force of one armoured and three field divisions was available in the United Kingdom, and in order that the defence of Great Britain might not suffer by the withdrawal of these formations, Mr. Churchill had gone so far as to request President Roosevelt “to place a United States Army Corps and Armoured Division, with all the air force possible, in the North of Ireland”.25 The Commanders-in-Chief, Middle East, however, setting a higher priority upon the defence of the vital area between the Nile delta and the Persian Gulf, considered an invasion of Sicily at that time neither practicable nor necessary. Accordingly, “Whipcord” had been abandoned.26

Early Planning for Operation HUSKY

General Eisenhower lost no time in acting upon the directive from the Chiefs of Staff, and on 12 February a planning staff composed of American and British members and organized on the British staff system (since the operation was to be executed under a British commander) set to work under Maj-Gen. C. H. Gairdner (who was later succeeded by Maj-Gen. A. A. Richardson) as Chief of Staff.27 As there was no accommodation available at the overcrowded Allied Force Headquarters in Algiers, the planners at their initial meeting selected the Ecole Normale in Bouzarea, just outside the Algerian capital. The number of the hotel room in which the first meeting was held gave the planning organization the name adopted as a security measure – Headquarters “Force 141”.28 It will be appreciated that this delegation of the control of planning operations to a special staff was made necessary by the full preoccupation of both the Supreme Commander and his deputy with the direction of the campaign that was still continuing in North Africa. Indeed, at this time General Alexander held a dual appointment, for in addition to having been designated Commander-in-Chief of the group of armies entrusted with the Sicilian operation, he was Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in North Africa and Commander of the 18th Army Group, the headquarters established by the Anfa Conference to coordinate the command of the British First and Eighth Armies in the Tunisia area.29

In reaching their decision at Casablanca the Combined Chiefs of Staff had considered a tentative outline plan for the invasion of Sicily which had been produced by a Joint Planning Staff in London, and later supplemented at Anfa.30 This was given to the Force 141 planners as a basis on which to work, and from it there emerged, after a series of modifications which

culminated in a major recasting, the pattern on which Operation HUSKY was finally mounted.

Certain elements of the projected undertaking as set forth in the Casablanca Outline Plan were accepted as fundamental, and remained constant throughout all stages of the subsequent planning. The directive to the Supreme Commander had indicated that HUSKY would require the employment of two task forces, one British and one United States, each of army size. Early in February General Montgomery and Lt-Gen. George S. Patton Jr., who had led the American landings at Casablanca in November, were appointed to the respective commands of these assault forces. It was a logical assumption that the American share of the operation would be based upon the French North African ports; it followed that the British task force must be mounted mainly from the Middle East Command.

Sicily, “a jagged arrowhead with the broken point to the west”, is an island admirably suited by position and terrain for defence against invasion from anywhere except Italy. Separated from the Italian peninsula by the Strait of Messina, which at its narrowest is only two miles wide, the island had long provided a natural springboard for the projection of Axis troops into Tunisia – for Cape Bon on the African mainland is but ninety miles from Sicily’s western tip. In the event of an Allied assault upon the island, enemy reinforcements could be expected to pour in from the toe of Italy – by sea ferry from the Calabrian ports or by transport aircraft from the airfields of Naples and Brindisi. To stem the flow of this traffic and then reverse it in defeat would be no easy task, for Sicily’s topography would overwhelmingly favour its defenders. Almost the whole surface of the island is covered with hills and mountains, which fall either directly to the sea or to restricted coastal plains or terraces. The only extensive flat ground is the east central plain of Catania, above which towers the massive cone of Mount Etna; more limited low-lying areas are to be found along the south-eastern seaboard and at the western extremity of the island. Once attacking forces had penetrated into the mountainous areas of the interior, their lines of advance would be restricted to the few existing roads, and their rate of progress conditioned by the enemy’s well-known skill in mining and demolition.

The early stages of planning were concerned chiefly with the selection of the points at which the main assaults would be made. Messina, at the north-eastern tip of the island, was regarded as the most important objective, for this strategically situated port might be expected to furnish initially the means of entry of Axis reinforcements from the mainland and, when the progress of the campaign should reach its expected climax, to

afford an escape route to the island’s defenders.*

* It was estimated that the train ferries at Messina could move up to 40,000 men, or 7500 men and 750 vehicles, in twenty-four hours.31

Possession of Messina would allow the Allied forces to dominate the Strait and provide them with a base for further operations into Italy. A direct assault on the port or its vicinity could not be contemplated, however, for the Strait of Messina was completely closed to Allied shipping by mines and coast defence batteries, and was beyond the effective range of Allied fighter cover based on Malta and Tunisia. It was therefore necessary to look elsewhere for invasion sites through which operations could be developed to overrun the island.

The main strategic factors to be considered may be reduced to a relatively few prime requirements. Geography must first furnish suitable beaches close enough to Allied-controlled airfields for the landings to be given fighter protection. Consideration of logistics dictated a second demand, thus defined by General Alexander:

It was still an essential element of the doctrine of amphibious warfare that sufficient major ports must be captured within a very short time of the initial landings to maintain all the forces required for the attainment of the objectives; beach maintenance could only be relied on as a very temporary measure. The experiences of Operation “Torch”, the North African landing, though difficult to interpret in view of the special circumstances of that operation,†

† In the “Torch” landings, which were made against relatively light enemy opposition, the loss in landing craft destroyed or damaged on the different surf-swept beaches had varied from 34 to 40 per cent.32

were held to confirm this view.33

Along the 600-mile coastline that forms the perimeter of the Sicilian triangle, more than ninety stretches of beach were reported by Allied Intelligence as topographically satisfying the requirements for landing operations. These ranged from less than one hundred yards to many miles in length and, although offshore gradients were in several cases unfavourably shallow and the beaches themselves of unpromising soft sand, most of them gave reasonably convenient access to the narrow coastal strip encompassing the island. Only in two sectors, however, could disembarkation be covered by land-based Allied fighter craft. These were the beaches in the south-eastern corner of the island, between the Gulf of Noto and Gela, which were within range of the Malta airfields, and those in the south-west, between Sciacca and Marinella, which could be reached from airfields in Tunisia.

Neither of these areas contained any of the major ports the early possession of one or more of which was deemed essential for providing unloading facilities for the assaulting armies. These ports were, in order of size, Messina, Palermo in the north-west, and Catania on the east coast. Against an enemy garrison whose strength was expected to be eight divisions

the planners considered approximately ten divisions would be necessary to take the island. Maintenance requirements for a division, including the build-up of reserves, were calculated at 500 tons a day; thirty tons a day were needed for a squadron of the Royal Air Force.34 It was estimated that the daily clearance capacity of the larger ports, when due allowance was made for damage that might be caused by our bombardment and the enemy’s demolitions, would be between four and five thousand tons for Messina, about 2000 for Palermo, and 1800 for Catania. There were lesser harbours*

* Syracuse on the east coast had an estimated capacity of 1000 tons a day, and Augusta, also on the east coast, Licata and Porto Empedocle on the south, and Trapani on the west coast could each handle about 600 tons daily.35

on the island – but an early decision was reached that the points of assault must be directly related to the location of one or more of the three major seaports.

With Messina out of the question as an immediate objective, consideration was given to securing Catania and Palermo in the early stages of operations. Catania alone would not provide facilities for the maintenance of a sufficient number of Allied divisions for the reduction of the whole island; Palermo would do so – if the enemy allowed enough time for a satisfactory build-up – but an assault directed solely against that area would leave the Axis forces free to reinforce through the eastern ports. A third factor thus entered the planning – the need for early seizure of Sicilian airfields, both to deny their use to Axis aircraft and to provide the invading forces with the means of air support in their operations against the required ports.

The disposition of those airfields was governed less by tactical considerations than by the limitations which the mountainous nature of the country imposed. They were to be found in three main clusters, all within fifteen miles of the coast (see Sketch 1). Most important of these was the Catania–Gerbini group in the eastern plain, for it gave cover to the Strait of Messina. Within supporting reach of this group, on the low ground behind Gela was the south-eastern concentration, comprising the Comiso, Biscari† and Ponte Olivo airfields. The third group lay along the narrow coastal plain at the western tip of the island, extending from Castelvetrano to Trapani and affording air cover to Palermo. These last fields were beyond fighter range of either the eastern or south-eastern groups.

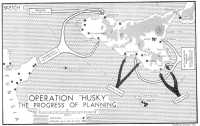

It thus became apparent that the immediate objective of the assault forces must be the airfields both in the south-east and the west, in order to provide the extension of air cover required for the capture of the ports of Catania and Palermo. Accordingly the original Casablanca Outline Plan proposed simultaneous landings by the Eastern and Western Task Forces. British forces would assault the south-east corner of the island with three

Operation HUSKY – The Progress of Planning

divisions on D Day to secure the airfields in that area and the ports of Syracuse and Augusta. With the air protection afforded by those captured fields a fourth infantry division plus a brigade group and an airborne division would assault in the Catania area on D plus 3 to secure the port and the important eastern group of airfields. In the meantime operations by American forces would begin on D Day with a landing by one division on the south-west coast at Sciacca to secure the western airfields required for operations against Palermo. The main assaults in the Palermo area would be made on D plus 2 by two divisions charged with the task of capturing the port and linking up with the thrust from Sciacca. Each Task Force was allotted a reserve division to be landed respectively through Catania and Palermo, to provide by D plus 7 sufficient forces to deal with any opposition that the enemy might offer.36

Throughout February and early March, while the direction of operations in Tunisia, now at the critical stage, claimed the undivided attention of General Alexander and his two prospective army commanders, the planners at Bouzarea, although short-handed by reason of the continued employment of many of their key personnel at the 18th Army Group Headquarters, applied themselves to such basic planning tasks as might be undertaken before firm decisions had been reached at the higher level. “All that was possible”, reports Alexander in his Despatch, “was to work out loading tables, training schedules and all such matters which must of necessity be taken in hand long before the date of the assault, while preserving complete flexibility of mind about the objectives which might eventually be selected for the assault.”37

The tentative outline plan on which all preliminary discussions had been based came under criticism from the three commanders of the ground, air and naval forces when they held their first meeting with General Eisenhower at Headquarters Force 141 on 13 March.38 General Alexander was concerned at the wide dispersion of the proposed landings, particularly those of the Eastern Task Force. He considered it vital to the success of the entire operation that the D Day assault at Avola in the Gulf of Noto should be strong enough to ensure the seizure of Syracuse and Augusta, and if possible Catania, very soon after landing. Only a third of the Force had been allotted to this crucial area, but additional insurance of success could be gained by transferring from the left flank the division assigned to land at Gela. Less than ten miles inland from Gela, however, was one of the most important airfields of the south-eastern group, the air base of Ponte Olivo, the capture of which for the use of the Allied air forces was deemed essential by Air Chief Marshal Tedder. This view was supported by

Admiral Cunningham, who was unable to accept the risk of leaving the enemy’s air power free to operate against the naval forces from airfields so close to the proposed landing areas.39

The Second Outline Plan

It was clear that Force 545 (the code name given by the planners to the Eastern Task Force) required strengthening. After a discussion of plans on 18 March at Bouzarea, when both army commanders were represented’40 General Montgomery requested that his Force – the military component of which was to be the Eighth Army – be allotted another division.41 But it was not clear whence such additional strength would be forthcoming. Although a division might be found in North Africa or the Middle East, the limiting factor was once again that of shipping, for all sea transport and landing craft expected to be available for HUSKY had already been assigned. A redistribution of strength within the existing resources of Force 141 appeared to be the only solution.

A proposal by General Alexander that the D Day assault by Force 343 (the Western Task Force) on the south-west shore at Sciacca should be cancelled, and the American division intended for that role transferred to the Gela beaches was tentatively agreed to by the Supreme Commander on 20 March.42 Like most compromise plans, however, this one had its weaknesses. It meant placing an isolated American division under the command of the British Task Force; and abandonment of the Sciacca landings would mean that the neutralization of the western airfields would have to be accomplished by long-range fighters based on the south-eastern group. Until such action had assured fighter cover for the operations against Palermo, it was not possible to fix exact dates for the American landings in that area. There thus appeared the unwelcome prospect of condemning the assaulting Seventh Army (the military element of Force 343) to stay aboard for an indeterminate period after D plus 3 somewhere between the North African ports and Western Sicily, exposed to possible attack from hostile aircraft based on the airfields behind Sciacca.43

In a letter to General Alexander on 23 March the Supreme Allied Commander expressed his uneasiness at the proposed change of plan.

The gist of the matter is that by agreeing to Montgomery’s demand for an additional division, we have come to the conclusion that we need one more division than can be transported in the means available to our two governments. Realizing that there is no hope of obtaining this additional shipping, we are adopting a plan which we consider the least objectionable of any we can devise. I am not too happy about the matter, but I do agree that the conclusion expressed in the preceding sentence is a true one.44

The British Chiefs of Staff too were disturbed by the proposal to abandon the south-western assault, for they feared that its cancellation might allow the enemy the continued use of Palermo as a port of entry for reinforcements, besides leaving his air forces free to operate in Western Sicily. They made strong representations through the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington that every channel should be explored to provide the additional division without disturbing the dispositions originally made for the Western Task Force.45

Further Revision of the Plan

Again the planners at Bouzarea examined the unfavourable shipping situation and counted British formations available in the Mediterranean area, and on 16 April General Alexander put forward a solution which tentatively restored the main outline of the original plan, and at the same time provided Force 545 with the extra strength it required in the Avola area. A new British division was introduced from North Africa to carry out the Gela landings, thereby releasing the American division for its assault on Sciacca. The specific employment of a division against Catania on D plus 3 was cancelled; instead one was to be held as an immediate reserve at Malta, on call after D plus 1. This formation would be neither assault trained nor assault loaded, and would be carried to Sicily in craft that had already been used in the D Day landings. By such a reshuffling of resources it was possible to meet the current demands of the assault plan without adding materially to the total number of landing craft required; the necessary increment was provided from British and American reserves at the expense of assault training and cross-Channel operations “on the decision to give absolute priority to HUSKY.”46

While the new plan followed essentially that produced by the British Joint Planning Staff for the Casablanca Conference, it contained important modifications in the timings of the landings. In drawing up the original schedule it had been recognized that simultaneous assaults at both ends of the island would have the desirable effect of dispersing the enemy’s air and ground forces. But there was much to be said for initiating operations in south-eastern Sicily, where surprise could more readily be obtained, and by so doing drawing off enemy reserves from the west – to the great benefit of a delayed assault there. The determining factor in making the change, however, lay in the decision to employ airborne troops in advance of the landings to “soften up” the defences. In order to drop the maximum number of troops in each area it would be necessary to employ all the available transport aircraft,

and to apply the total lift to each airborne assault in turn. Accordingly, a series of staggered landings was proposed. Whereas the four British divisions of Force 545 would assault on all beaches from Avola to Gela on D Day, the American landings were to be postponed to D plus 2 for the division assaulting at Sciacca, and to D plus 5 for the two divisions assigned to the landings in the Palermo area. In addition to the division to be held at Malta, one for each of the Eastern and Western Task Forces would be available in North Africa as a later follow-up.

On 11 April the Supreme Commander notified the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington of his adoption of these changes,47 and it was in this form that the outline plan for HUSKY stood when Canadian participation in the operation was invited. But it was not yet the pattern of the actual assaults which were delivered in July; that formula had still to be worked out.

On 24 April (the day following General McNaughton’s visit to the War Office) General Alexander received from General Montgomery a signal expressing the latter’s concern at the disposition of the British forces proposed by the existing outline plan. Always an exponent of the “principle of concentration”*

* A recognized “Principle of War”, that the concentration of the maximum possible force of every possible description should be brought to bear on the enemy at the decisive time and place.

he felt the need of a greater mobilization of power in the assault area. “Planning so far”, wrote Montgomery, “has been based on the assumption that opposition will be slight, and that Sicily will be captured relatively easily. Never was there a greater error. The Germans and also the Italians are fighting desperately now in Tunisia and will do so in Sicily.”48

General Alexander was disinclined to agree that the enemy’s powers of resistance had been underestimated. In his Despatch he recalls the gloomy prognostications of the British Joint Planning Staff in its original report to the Casablanca Conference – “We are doubtful of the chances of success against a garrison which includes German formations”49 – and he draws attention to the fact that “actually planning had been based on the appreciation that the mobile part of the garrison of the island would be more than doubled.”50 On the other hand, he was only too conscious of the slimness of the margin of advantage which the assaulting forces might be expected to hold over the defenders. In actual numbers, if Intelligence estimates were accurate, the enemy garrison could outnumber the invading Allied troops. It was assumed for planning purposes that there would be in Sicily at the time of the invasion two German and six Italian mobile divisions and five Italian coastal divisions;†

† This appreciation was reasonably accurate. Enemy forces in Sicily at the time of the actual assault consisted of two German and four Italian mobile divisions and six Italian coastal divisions (see below, pp. 55-9).

Force 141, as we have seen, would have just over

ten divisions, including airborne formations, and two more divisions in reserve. While it was reasonable to believe that this Allied inferiority in numbers would be more than offset by the advantages which the invaders held in their command of the sea and air, in their superiority in equipment (at least over the Italians), and in their possession of the initiative to choose the points of attack, it was apparent that these advantages would be seriously diminished by the dispersal proposed by the outline plan.

To General Montgomery examining the commitments given the Eastern Task Force at a three-day conference of Force 545 planners in Cairo, which began on 23 April, it seemed essential that his forces “be landed concentrated and prepared for hard fighting.”51 With only four divisions at his command he considered it necessary to restrict the frontage of his army’s assault to the area of the Gulf of Noto and the Pachino peninsula. The assaulting forces would be close enough to Syracuse to ensure its early capture and the development of operations northward against Augusta and Catania. The proposal to concentrate in this manner had, however, one obvious drawback – the Comiso–Gela group of airfields was too far to the west to be included in the initial bridgehead. As may be readily imagined, the Commanders-in-Chief of the other Services, who had once already successfully upheld their claim for including in the planning the early capture of the Ponte Olivo airfield north-east of Gela, strongly objected to a proposal that would now leave the whole Ponte Olivo–Biscari–Comiso group of fields in enemy hands during the initial operations. At a conference in Algiers called by General Alexander on 29 April, Admiral Cunningham declared that “apart from his conviction on general grounds, that in amphibious operations the landings should be dispersed, he considered it essential to secure the use of the south-eastern airfields in order to give protection to ships lying off the beaches.”52 If this were not done he feared that shipping losses might be so prohibitive as to prevent the landings in the west.53 Air Chief Marshal Tedder, pointing out that the Eighth Army plan would leave thirteen landing-grounds in enemy hands, far too many for effective neutralization by air action, formally stated that unless their capture for Allied use “could be guaranteed he would be opposed to the whole operation.”54 Speaking for the ground forces, Lt-Gen. Sir Oliver Leese,55 representing General Montgomery, objected that to shift the proposed Force 545 bridgehead westward to include the Comiso–Gela group of airfields would move it too far from the ports that had to be captured on the east coast.56

It was’ impossible to reconcile these conflicting views. They clearly revealed the fundamental weakness of the entire strategic plan, “which in attempting – with limited resources – to achieve too much at the same time in too many places, risked losing all everywhere.”57

The Final Plan of Attack

“On May 3rd”, wrote General Eisenhower, “we stopped tinkering and completely recast our plan on the sound strategic principle of concentration of strength in the crucial area.”58 On that day the Supreme Commander, concurred in a decision by his deputy to cancel the American assaults in the west and the south-west and divert the entire Western Task Force to the south-eastern assault, placing it on the Eighth Army’s immediate left.*

* In his Despatch Alexander points out that as early as February he had considered concentrating the efforts of both Task Forces against the south-east of the island.59 Different versions of the question of personal responsibility for the decision to make the assault as finally planned are given by Montgomery and his Chief of Staff.60

In abandoning the idea that Palermo must be captured as a means of maintenance for the Seventh Army, General Alexander chose to take this administrative risk rather than the operational one of too much dispersion. Within the new area assigned for its landings the American Task Force would have only one small port – Licata, which now became the farthest west point of assault. Acceptance of the fact that the Seventh Army would rely almost entirely on beach maintenance marked an important departure from the belief that success in large-scale amphibious warfare depended upon the early capture of major ports. The Senior Administrative Officer of Force 141, Maj-Gen. C. H. Miller, had dubiously reminded the planners that they were ignoring the experience of the North African landings, “which proved that a force must have a port for its maintenance within 48 hours of landing”. He had suggested, however, that this lesson might not apply to the forthcoming operations because of the better prospects for good weather in midsummer, the greater certainty of Allied air and sea superiority, and, most important of all, the fact that DUKWs would be available to transfer supplies from ship to shore.61 General Miller’s advocacy of beach maintenance proved justified. The results in Sicily vindicated the decision to employ this new technique of combined operations, and led to its adoption, with outstanding success, in the invasion of Normandy in 1944.

With the approval of the new plan by the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 12 May it was possible to proceed with firm and detailed planning, and on 19 May General Alexander issued his first operation instruction setting forth the tasks of the two armies and the part to be played by the supporting naval and air forces.62 He stated that the intention of the Allied Commander-in-Chief to “seize and hold the island of Sicily as a base for future operations” would be accomplished in five phases: preparatory measures by naval and air forces to neutralize enemy naval efforts and to gain air supremacy; pre-dawn seaborne assaults, assisted by airborne landings with the object of seizing airfields and the ports of Syracuse and Licata; the

establishment of a firm base upon which to conduct operations for the capture of the ports of Augusta and Catania, and the Gerbini group of airfields; the capture of these ports and airfields; the reduction of the island.

The Eighth Army would assault with two corps, comprising a total of six infantry divisions, one infantry brigade and one airborne division, in the area between Syracuse and Pozzallo. It would be responsible for the immediate seizure of Syracuse and the Pachino airfield, and the subsequent rapid capture of Augusta and Catania and the Gerbini group of airfields. On the left the Seventh Army, with one corps headquarters, four infantry divisions, one armoured division and one airborne division, was to assault between Cape Scaramia and Licata, capture that port and the airfields at Ponte Olivo, Biscari and Comiso, and on gaining contact with the Eighth Army protect the British left flank from enemy reserves moving eastward. When the two armies were firmly established across the south-eastern corner of Sicily in a line from Catania to Licata, operations would be developed to complete the conquest of the island.63

The Background to Canadian Participation

With the pattern of HUSKY thus finally determined it may be useful to turn to an examination of the circumstances surrounding the entry of the Canadian formations into the Sicilian enterprise. The story of the high policy that directed the employment of Canadian forces during the war will be told elsewhere in this History; it will be sufficient here to take a brief look at the background to Mr. Churchill’s invitation of April 1943. Early in the course of the HUSKY planning it had been decided that because of the limited facilities of the Middle East ports it would be necessary for Force 545 to draw direct from the United Kingdom an infantry division and an army tank brigade.64 Nomination of these formations lay with the War Office, which towards the end of February had selected the 3rd British Division.65 Detailed administrative planning began immediately and the division embarked upon a programme of intensive training in combined operations and mountain warfare. On 24 April it was replaced in this role by the 1st Canadian Division, with what must have been to the British formation disappointing abruptness.

The considerations which brought about this substitution were not exclusively military. In Canada towards the end of 1942 public opinion, which could, of course, have no authentic knowledge of what plans might be in the moulding for the future employment of Canadian troops, was becoming increasingly vocal through the press and on the rostrum in exerting pressure upon the Government to get its forces into action as soon as possible. Canadian troops had been in the United Kingdom for three years, and except

for a single day’s bloody action at Dieppe by units of the 2nd Canadian Division had seen no real fighting.

Fairly typical of editorial comment was the suggestion made at the beginning of November that it would be “a sensible thing to send a full division to some theatre of war, or next best at least shour senior officers ... An opportunity like Egypt to get actual fighting experience for officers and men should not be allowed to slip by complacently.”66 In Toronto an ex-Prime Minister of Canada, Lord Bennett, said that he could find no reason why the Canadian Army should have to spend its fourth Christmas in Britain without firing a shot.67 A journalist reported to his paper from overseas that Canadian troops were feeling themselves to be “a sort of adjunct to the British Home Guard”; they were regarded as “the county constabulary in the English countryside”.68 Even statistics of a Canadian Army Neurological Hospital were presented under the headline, “Mental Illness in Overseas Army Laid to Inactivity and Anxiety”.69 In Vancouver the Canadian Corps Association heard a veteran of the First World War declare:–

It strikes me as one of the supreme tragedies of this war that the United States, following one year in the struggle has already placed men in battle engagements in Africa while Canadian soldiers are sitting idle in England. This constitutes the greatest disgrace of the present war.70

The argument for giving some of the Canadian formations large-scale battle experience before committing the Army as a whole to operations was sound, and one that might well carry conviction in the military councils of the United Nations at a high level; in a somewhat different category were the more domestic and political reasons advanced, that the continued inactivity of her Army was damaging to the Dominion’s self-respect, and that the lack of a demonstrable contribution to victory might well weaken her influence in the post-war world.*

* In a memorandum prepared for the Prime Minister at the end of January 1943, Mr. Hume Wrong, Assistant Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, expressed the fear that “Canada would become the object of taunts similar to that which Henri Quatre addressed to a tardy supporter who had arrived too late for the battle: ‘Go hang yourself, brave Crillon, for we fought at Arques and you were not there!’ “

These aspects received increasing attention in the criticism which continued to be directed against the Government throughout the winter. As Parliament resumed after the Easter recess an opposition speaker regretted that men who had been overseas since 1939 should “have it thrown in their faces that while Australia and New Zealand are fighting gallantly on the sands of Africa personnel of the Canadian Army are not there.”71 Some newspapers suggested that the decision to keep the Canadians out of action had been made at Canada’s request.

All other Empire troops have had battle experience in this war ... The British have been everywhere. Only Canadians, among all the Allied combatants, have not been tried.

This, we confess, seems strange. To a great many it is disturbing.72

It was charged that the blame lay with the Government’s policy of wishing to maintain the Canadian Army intact. One editor pointed to the many theatres of war in which “one or two or even three Canadian divisions could play a useful role”, and in urging the Government “to make at least fragmentary use of the great striking force” which had been raised and equipped by the nation, warned that “the hand which holds the poised dagger can become palsied through lack of use.”73 In mid-May 1943, unaware that the course which he advocated had already been taken, another wrote in similar vein:

Now that the North African campaign is finished and a new phase of the war is opening up, the honest course would be to admit frankly, even at the expense of personal pride, that the creation of a cumbrous military establishment overseas was an error of judgment and to permit the utilization of Canadian divisions in any formation where they can be effectively employed.74

These popular representations were presumably not without effect upon Government policy, and at a meeting in the United Kingdom with Mr. Churchill in October 1942 the Minister of National Defence, Colonel J. L. Ralston, requested that active employment should be found for the Canadian Army at the first opportunity. Later General McNaughton received from Lt-Gen. Kenneth Stuart, Chief of the General Staff, a brief account (as told him by Colonel Ralston) of what had transpired at this meeting. ‘The Minister of National Defence had emphasized to Mr. Churchill

that there were no strings on the employment of the Canadian Army, either in whole or in part: that the Government of Canada wished it to be used where it would make the greatest contribution: that the Canadian Government were ready to consider any proposals.75

On his return to Canada Colonel Ralston reported to the War Committee of the Cabinet on 21 October that it had once more been made clear to British authorities that the Canadian Army was available for service anywhere it could be most effectively employed. No condition that it must be employed as a whole was being imposed. The sole consideration was how and where the Army could serve best.

But while the Government was thus disclosing its readiness to divide the Army if such means were necessary to bring Canadian troops into action, the Army Commander himself showed less enthusiasm towards such a proposal. On learning from. General Stuart of Colonel Ralston’s representations to the British Prime Minister, General McNaughton reports that he then told the Chief of the General Staff that he was in full agreement with the policy that the employment of the Canadian Army should be based on its making the maximum possible contribution; that this might be in whole or in part, according to circumstances. ...

He went on to give his opinion, however,

that there was no reason to doubt that morale could be maintained even if we had to remain in England on guard for another year; that this was therefore no reason in itself for advocating active operations for their own sake; that anything we undertook should be strictly related to military needs and objectives.76

To forecast accurately for a year ahead the state of the morale of the Army if kept in the United Kingdom without action was not easy, but the problem had to be faced by those responsible for shaping Canadian policy. The unremitting efforts of the Canadian commanders to keep up a high standard of morale and discipline were bringing excellent results. During the closing months of 1942 and early in 1943 the fortnightly Field Censorship Reports – which provided a valuable sampling of the opinions held by the Canadian forces as revealed in their letters home – indicated with gratifying regularity that the morale of the Canadians in Britain was being fully maintained.*

* In February 1943 General Sir Bernard Paget, C-in-C Home Forces, told Lt-Gen. H. D. G. Crerar, GOC 1st Canadian Corps, “that he was increasingly impressed by the smartness and behaviour of the Canadian troops which he daily saw in London. He said that he could recognize Canadian soldiers across the street by their excellent bearing, and that their saluting was quite first-class.”77

This intelligence however was frequently qualified by a reference to the dissatisfaction of some of the troops at their present inactivity. During November some regret was voiced that Canadians had not been included in the landings which had been made in North Africa at the beginning of the month. There was always hope of action – Mr. Mackenzie King in his New Year’s broadcast had warned the people of Canada that “all our armed forces” would be in action during 194378 – and as winter turned to spring evidence appeared that some of the troops expected this to come in the near future. A report which covered the last week in April showed that

Notwithstanding the long period of waiting, the Canadian Army appears to be in excellent condition on the whole, and ready and anxious to move. There are still a number of comments which indicate restlessness and boredom due to this inactivity, but there is much evidence of a great desire for, and anticipation of, action in the near future. The chief desire is to get on with the job, for which they came over, and then get back to their homes.79

From this and similar evidence in the reports of newspaper correspondents overseas it is clear that the major factor contributing to the morale of the Canadians in the United Kingdom during the winter of 1942–43 was their conviction that action would not be much longer delayed. That hope more than anything else encouraged them to endure with comparative cheerfulness the routine of what must otherwise have seemed merely training for training’s sake. The degree to which their enthusiasm might have been sustained had 1943 brought no operational employment to Canadian arms can only be surmised; but it is not difficult to imagine the disquietude with which the Canadian Government must have contemplated at the end of 1942 the

probable effect of another year of inactivity upon the morale of its overseas troops.

Canada received no invitation for her troops to take part in the “Torch” landings in North Africa*

* It may be noted that in July, when the decision was reached to mount “Torch”, Mr. Churchill was contemplating the employment of the Canadian Army in an operation to seize aerodromes in Northern Norway (“Jupiter”) in order to counter enemy air action against convoys to Russia. (General McNaughton’s connection with this project is discussed in Volume l of this History, Six Years of War.) The British Chiefs of Staff opposed the scheme as impracticable, but on the 27th the Prime Minister notified President Roosevelt that he was running “Jupiter” for deception and that the Canadians would “be fitted for Arctic service”.80 A project, put forward in October 1942, for a Canadian force under General Crerar’s command to participate in a combined operation against the Canary Islands (in the event, of a German occupation of Gibraltar) did not get beyond the stage of preliminary planning (see Volume I, Chapter 12).

– indeed it was not until September that General McNaughton was informed of the decision to launch the operation and of the progress of its detailed planning.”81 On the last day of the year, however, the Army Commander was advised by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff that an opportunity might soon arise for Canadian participation in an operation against Sardinia or Sicily.82 The Chiefs of Staff Committee was contemplating for such an enterprise the employment of a British corps of three divisions, and Sir Alan Brooke warned McNaughton that a formal request might be forthcoming for Canada to supply one of these divisions. Within a week a proposal for the conquest of Sicily had been placed on the agenda of the approaching Casablanca Conference as a joint Allied task; but there was still a possibility of the occupation of Sardinia being mounted as a British operation, under the code name “Brimstone”.83 At the end of January, in anticipation of a favourable decision by the CIGS, the 1st Canadian Division was given priority in the use of facilities to complete its training in combined operations. With the development of planning for the assault on Sicily, however, the mounting of Operation “Brimstone” was tentatively cancelled, the Army Commander and General Stuart being so informed by General Brooke on 9 February.84 It looked as though Canadian troops were fated not to see the Mediterranean; and the eyes of Canadian planners returned to the contemplation of operations against a hostile shore closer to the United Kingdom.

By the middle of March, however, it had become apparent that there would be no large-scale cross-Channel operation that summer, except in the extremely unlikely event of a major German collapse. This was exceedingly disappointing news for the Canadian Government, and there was a marked degree of urgency in the telegram sent by Mr. King to Mr. Churchill on 17 March suggesting that “the strong considerations with which you are familiar in favour of employment of Canadian troops in North Africa appear to require earnest re-examination.”85 Additional representation was made at the military level when the Chief of the General Staff signalled General McNaughton next day that if there was little possibility

of the Canadians being employed in 1943 as planned (i.e., in an operation against North-West Europe) “we should urge re-examination for one and perhaps two divisions going as early as possible to an active theatre.” General Stuart pointed out that it was the War Committee’s opinion that if no operations other than raids were thought possible during 1943, Canada should press for early representation in North Africa.”86

The replies to both these messages were not encouraging. On 20 March McNaughton reiterated his firm belief in the overriding authority of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee in the matter of strategic planning.

My view remains (1) that Canadian Forces in whole should be used where and when they can make the best contribution to winning the war, (2) that we should continue to recognize that the strategical situation can only be brought to a focus in Chiefs of Staff Committee, (3) that proposals for use of Canadian forces should initiate with this committee, (4) that on receipt of these proposals I should examine them and report thereon to you with recommendations.

“I do not recommend”, he added, “that we should press for employment merely to satisfy a desire for activity or for representation in particular theatres however much I myself and all here may desire this from our own narrow point of view.”87

Mr. Churchill’s answer to Mr. King, dispatched the same day, held out little hope of meeting the Canadian request. He explained that it was intended to send only one more division from the United Kingdom to North Africa; this formation was already committed and under special training, and plans were too far advanced to permit of a Canadian division being sent in its place. No further divisions were likely to be required. “I fully realize and appreciate”, concluded the Prime Minister, “the anxiety of your fine troops to take an active part in operations and you may be assured that I am keeping this very much in mind.”88

At the end of March the Canadian Government was able to obtain the views of Mr. Anthony Eden. The British Foreign Secretary was made fully conversant with the case for Canadian troops to be given an early opportunity for action, and it was emphasized to him that the Government and the Army Command were willing to have the Canadian Army employed, in whole or in part, at any time and in any theatre of war in which it would be most effective. He was reminded of the Government’s understanding that the Canadian Army was to be held in Britain for use as a unit in European operations later that year, and was told that if there had been any change in this plan and Canadian troops were not to be used even for limited operations in 1943, it would be a serious blow to the spirit of both the Canadian Army and the Canadian people. But Mr. Eden could offer little encouragement; for although Allied plans had been based on the possibility of offensive operations in the late summer or early autumn, this did not mean

that full-scale invasion in 1943 was a probability. A great deal depended on the developments in Russia and North Africa.

Nevertheless it must be concluded that this reiteration of the Government’s request bore fruit with the British authorities. Mr. Churchill, having given his assurance to keep the question of operational employment “very much in mind”, was as good as his word. Whatever may have been the considerations that finally turned the scale in favour of Canada, by St. George’s Day the British Prime Minister had issued to Sir Alan Brooke his directive that Canadian participation was to be arranged in the next operation.89

The Chief of the Imperial General Staff immediately sent word of the inclusion of Canadian troops in Operation HUSKY to the Allied commanders in the Mediterranean Theatre.

Personal from CIGS for General Eisenhower, repeated General Alexander.

1. Both political and military grounds make it essential that Canadian forces should be brought into action this year. It had been hoped to employ them in operations across the channel from UK but likelihood of such operations has now become extremely remote owing to recent addition to HUSKY of practically all remaining landing craft.

2. It has therefore been decided that 1 Canadian Division and a tank brigade similarly organized to 3 Division and its tank brigade will replace latter in the Eastern Task Force for the HUSKY operation subject to confirmation from the Canadian Government which we hope will be immediately forthcoming.

3. I very much regret this last minute change. We have been very carefully into its implications and consider it quite practicable. The Canadian Division is In a more advanced state of combined training than 3 Division and the Canadian planning staff have already started work with full assistance of 3 Division so no time is being lost.

4. Request that Force 141 and 545 be informed.90

When General McNaughton advised General Brooke on 25 April of the Canadian Government’s provisional acceptance of the British invitation it was with an important reservation. In his capacity as Senior Combatant Officer overseas he considered it part of his responsibility to examine the general plans of the proposed operation before recommending acceptance to the Canadian Government. After three crowded days, during which he was almost constantly engaged in discussion with War Office officials – the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the Vice Chief, the Director of Military Operations and Planning, with members of his own staff at Army Headquarters, and with the Commanders of the 3rd British and 1st Canadian Division91 – he was able to report to Ottawa his satisfaction that the plans represented “a practical operation of war.”92 On the receipt of this assurance General Stuart notified the Army Commander of the Canadian Government’s final approval.93

Next day McNaughton received a message from General Montgomery: “Am delighted Canadian Division will come under me for Husky.”94