Chapter 5: The Beginning of the Eastward Drive

23–31 July 1943

The Conquest of Western Sicily

The five days of bitter fighting during which the Canadians had dislodged the enemy from the Valguarnera heights and then forced him out of his Assoro and Leonforte strongholds had seen little progress elsewhere on the Eighth Army’s front. Between 18 and 21 July the 13th Corps had fought two major actions in a fruitless attempt to break through to Misterbianco, on the high ground west of Catania; while the 51st (Highland) Division (of the 30th Corps), trying to reach Paterno, had been halted after taking Sferro village and Gerbini in two bitterly contested engagements. Then the Hermann Görings, determined at all costs to deny Allied use of the main Gerbini airfield, had counter-attacked and driven the 51st back to the line of the Dittaino River.1 It was apparent to Army Headquarters that the bulk of the German forces had now concentrated in the north-east comer of the island, specifically in the Catania plain and the hills that bounded it to the north, and that any further attack by the 13th Corps and the 51st Division would inevitably lead to high casualties.2

Western Sicily, however, presented a very different picture. At the end of the first week of the campaign there remained here two intact Italian divisions – the 202nd and 208th Coastal Divisions – and elements of the 26th Assietta and 28th Aosta Divisions which were covering the general withdrawal to the east. In order to make the Allied left flank secure, these had to be liquidated; moreover the excellent port of Palermo was urgently needed as a supply base for the Seventh Army. The defensive role to which his troops had been relegated on 16 July (see above, p. 94) while the Eighth Army carried the main offensive irked General Patton. “To have adhered to this order”, he wrote later, “would have been disloyal to the American Army.” He flew to Algiers on the 17th and presented General Alexander with a

draft plan3 for an enveloping attack on Palermo.*

* The Seventh Army Report of Operations contains a marked map of Sicily illustrating a proposed change in the Army Group Directive of 16 July. Having indicated the Eighth Army’s three main axes of advance into the Messina peninsula (above, p. 94), the plan provided that “the 7th Army will drive rapidly to the north-west and north, capture Palermo, and split the enemy’s forces.” This plan, the Report states, “was agreed to 17 July 1943 at a conference between CG 15th Army Group and CG 7th Army accompanied by Brig.-General Wedemeyer, USA”4

Next day the Army Group Commander issued orders for the Seventh Army to cut the coast road north of Petralia and then from a firm base along the line Campofelice–Agrigento to “advance westwards to mop up the western half of Sicily.”5 “The rapid and wide-sweeping manoeuvres envisaged in this directive were very welcome to General Patton”, writes Lord Alexander, “and he immediately set on foot the measures necessary to carry them out with that dash and drive which were characteristic of his conduct of operations.”6

While the 2nd US Corps, commanded by Lt-Gen. Omar N. Bradley, drove northward to form the firm base and split the island in two, Patton sent Maj-Gen. Geoffrey Keyes’ Provisional Corps (which had been created on 15 July from the 3rd Infantry, 82nd Airborne and 2nd Armoured Divisions) racing north-westward towards Palermo.7 By 20 July the 2nd Corps had taken Enna, and the Provisional Corps was at Sciacca, the port on the south coast which, it will be recalled, had been chosen for an American D Day landing in the original Casablanca Outline Plan for Operation HUSKY. That evening, encouraged by the rapid American progress, General Alexander directed Patton “to turn eastwards on reaching the north coast and develop a threat along the coast road” and the parallel inland road (Highway No. 120), which runs south of the mountain barrier through Petralia, Nicosia and Troina to Randazzo.8 The directive concluded with a forecast of the pattern for the final stages of the campaign. “Future operation is to make Palermo the main axis of supply for 7th Army and to develop a combined offensive against the Germans by bringing American forces into line with 8th Army with a view to breaking through to Messina.”9

The terms of this order had been largely anticipated in the discussions of 17 July, and General Patton was able to maintain the momentum of his advance without slackening. Late on 22 July his Provisional Corps swept into Palermo, and on the 23rd the 2nd Corps took Petralia and reached the coast midway between Termini Imerese and Campofelice.10 That same day General Keyes occupied the seaports of Trapani, Marsala and Castellammare; and early on the 25th Kesselring admitted to Berlin, “The occupation of Western Sicily by the enemy can now be considered as completed.”11 There remained only the elimination of a few isolated pockets of resistance and the disarming of the many disorganized Italian units. The capture of 11,540 prisoners by the Americans that day was their biggest bag of the campaign

and brought to more than 50,000 the total taken by the Seventh Army since D Day. Patton now transferred the bulk of his artillery to General Bradley’s 2nd Corps, which without loss of time had turned eastward for its drive into the Messina peninsula.12

Reinforcing the German Garrison

Up to the time of the capture of Enna, while the Allied field of operations was still restricted to the southern half of Sicily, the enemy’s main concern, as we have seen, was to establish and maintain a continuous defensive line running westward across the island from Catania. It was apparent, however (no less to the German than to the Allied Command), that a collapse of Italian resistance in the west would leave this line with an exposed right flank and provide the Allies with an open avenue of approach into the Messina peninsula. To see how the enemy met this threat to his rear it is necessary to turn back several days and survey the changes that had taken place in German troop dispositions in Sicily.

It will be recalled that by 14 July the Hermann Göring Division was preparing to concentrate its forces in the Catania plain, while on the German right, west of the central portion of the line (which was held by elements of the Italian 4th Livorno Division), the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had assumed responsibility for the Caltanissetta-Enna region. As Italian resistance dwindled, it became clear to Kesselring that the defence of the island could not be successfully sustained by two German divisions in the face of two well-equipped Allied armies. It was moreover obviously unsatisfactory that the German forces in Sicily should remain under the tactical control of General Guzzoni’s Sixth Army Headquarters, tenuous though that control might be. Accordingly on or about 14 July the Headquarters of the 14th Panzer Corps, which had been carrying on the tasks begun by the Einsatzstab, was ordered to cross the Messina Strait and assume command of all German formations on the island. The Commander of the Corps (which had been reconstituted after destruction at Stalingrad) was General of Panzer Troops Hans Hube, a one-armed veteran of the First World War, who had distinguished himself by his brilliant leadership on the Russian front in 1941 and 1942. General Hube and his staff moved to Sicily on 16 and 17 July, and established tactical headquarters on the northern slope of Mount Etna, east of Randazzo.13 His task, as set forth in verbal orders brought to him by von Bonin, his new Chief of Staff, from General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, was “to fight a delaying action and gain further time for stabilizing the situation on the mainland”.14 Officially the German Corps Headquarters was under command of HQ Italian Sixth Army,

but in actual practice the relationship was reversed, and in the remaining weeks of the campaign orders were channelled directly from the Commander-in-Chief South to the 14th Panzer Corps, and carried out without question by General Guzzoni.15

It was no mere chance that brought about this assumption of control over the Italian armed forces in Sicily. The move had been carefully engineered in Berlin; and three days before Hube set foot on the island a staff officer was dispatched by air to advise Kesselring of Hitler’s plan for the 14th Panzer Corps Commander to usurp the Italian command. The gist of this is revealed in a situation report of the Armed Forces Operations Staff for 13 July:–

In a further written communication OKW*

* Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces).

informs O.B. South that the Führer had caused a special directive to be issued for Headquarters 14 Pz Corps, which is to be kept secret from the Italians, and the [distribution] of which is to be limited to the smallest possible circle, even in German quarters. Hereafter it will be the task of Corps Headquarters, in close cooperation with the head of the German Liaison Staff attached to Italian Sixth Army, to take over the overall leadership in the bridgehead of Sicily itself, while unobtrusively excluding the Italian headquarters. The remaining Italian formations are to be divided up and placed under the command of the various German headquarters.16

The flow of reinforcements to the island proceeded apace. Already, in the first days after the Allied landings, two regiments of the 1st Parachute Division (before 1 June designated the 7th Flieger Division) had been hurriedly flown from France to reinforce the Hermann Görings in the defence of Catania (the 3rd Parachute Regiment jumped near Lentini on 12 July; the 4th Regiment descended near Acireale, about ten miles north-east of Catania).17 The balance of the Division (except for its anti-tank units, which reached Sicily on 22 July) remained on the Italian mainland. The units on the island were placed under the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, “a wasteful use” of his troops which considerably annoyed the commander of the Parachute Division, Lt-Gen. Richard Heidrich.18 The remaining major German formation to be committed in strength was the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, an advance group of which (the reinforced 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment†)

† This battalion came under command of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division near Regalbuto, and only rejoined its parent formation on 14 or, 15 August. It defended Agira against the 1st Canadian Division.19

was reported by Kesselring on 16 July to be in action north of Catania.20 At the time of the Allied landings the Division, commanded by Maj-Gen. Walter Fries, had been on the Italian mainland in the Foggia–Lucera area, whence it had immediately been rushed to the Tyrrhenian coast in the vicinity of Palmi, less than twenty miles north of Messina Strait. Completion of the transfer to Sicily was held up by Hitler, who was concerned that German supplies on the island might be insufficient for another formation – “a finickiness” said Kesselring later, “which was to be

paid for in the subsequent battles.”21 The bulk of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment crossed on 18 July. Four days later Kesselring ordered the remainder of the Division to follow (although an amendment to this order kept Fries’ Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion and Tank Battalion on the mainland as coastal protection).22

In planning his course of action Hube’s primary concern was that the Strait of Messina should be kept open – first for the passage of vital supplies to his forces, and subsequently as a means of evacuation from the island. Jodi’s orders (as reported by Hube’s Chief of Staff) were most explicit on this point: “The vital factor ... is under no circumstances to suffer the loss of our three German divisions. At the very minimum, our valuable human material must be saved.”23 Accordingly the Commander of the 14th Panzer Corps took immediate measures to meet as far as possible the threefold danger that continually menaced his lifeline to the mainland: that of air attack, blockade of the Strait by an Allied fleet, or an Allied seaborne landing. He appointed as Commandant of the Strait of Messina a capable and energetic officer, Colonel Ernst Gunther Baade, whose contribution to the successful German evacuation from Sicily was later to win for him the command of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division. It was Baade’s task to organize and coordinate all available means of protecting the narrow water passage and maintaining the flow of traffic across it, and for this purpose he was given unconditional control over all artillery and anti-aircraft units and other forces in the Messina region and the mainland area about Villa San Giovanni and Reggio Calabria.24 The only two batteries of heavy artillery on the island (17-cm. guns with a maximum range of 17 miles) were brought from the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division to the Strait to protect the ferry route against naval attack. All non-combatant installations that could be dispensed with (workshops, camps of all sorts and medical establishments) were ordered back to Calabria, where a specific area was allotted each division to serve as a supply base, and eventually as a concentration area when the final evacuation from Sicily should take place. Command of these bases was given to General Heidrich, who was, as we have seen, without other duties at this time.25

Simultaneously with these measures for the protection of his escape route, Hube took action to meet the American threat to his western flank. After the loss of the central region about Enna the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, commanded by Maj-Gen. Eberhard Rodt, had lengthened its right wing with weak elements towards the northern coast (Kesselring’s subsequent claim of having held “a solid defence front on the general line Cefalu–Leonforte”26 is somewhat exaggerated). On 23. July, however, as the United States 45th Infantry Division began to push eastward along the coastal road, the reinforced 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (29th Division), under

the command of Colonel Max Ulich, was sent forward to the Cefalu area to fill the gap between General Rodt’s division and the sea.27 During the next day or two Ulich’s group was joined by the 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment, and by the divisional headquarters of General Fries, who assumed command of the northern sector on a front of a dozen miles. From his Mount Etna headquarters, General Hube could now contemplate with satisfaction a continuous line of resistance*

* The central portion of this line ran south-east from Nicosia to a point about three miles west of Agira, thence eastward along the highway to midway between Agira and Regalbuto, where it turned south-eastward towards Catenanuova.

reaching across the peninsula from Catania on the east coast to San Stefano on the north.28

The Eighth Army’s Change of Plan

On 21 July General Montgomery finally decided that Catania could not be taken by frontal attack without incurring heavy casualties which he “could not afford”. He planned instead to break through the Etna position from the west using the 30th Corps, reinforced by the 78th Infantry Division, which he had ordered the previous day to be brought across from Sousse, in Tunisia. Accordingly he issued instructions for all formations of the Eighth Army except the 1st Canadian Division to assume a defensive role along the line of the Dittaino River. The Canadian operations were “to continue without restraint directed on Adrano”.29 He thus explained his intentions in a message to General Alexander on the 21st:–

We are making new airfields on the South edge of Catania Plain, but they will be in range of artillery from Misterbianco area. Heat in the Plain is very great and my troops are getting very tired. During the past ten days we have driven enemy into North East comer of the island. He is determined to hold fast on his left flank about Catania and further attacks here by me will mean heavy losses. I am therefore going to hold on my right and will continue operations on my left against Adrano. Will give 78 Division to 30 Corps so that 30 Corps can have greater strength in its operations North towards Bronte. Two things are now very important – (1) American thrust eastwards along North coast towards Messina. (2) The full weight of all air power that can be made available from North Africa must be turned on the enemy army now hemmed in to the North East corner of Sicily.30

Montgomery had good grounds for his change of plan. The 13th Corps, which had been the first to strike the main line of resistance of the enemy’s resistance which was subsequently strengthened by reinforcing German paratroops and the concentration of the Hermann Göring Division in the east – had been fought to a standstill. The 51st Division of the 30th Corps, although initially facing lighter opposition, had advanced across 150 miles of difficult country in the wide flanking sweep which had brought it to the

Dittaino River in line with General Dempsey’s forces; any further attempt to reach Paterno would leave its left flank dangerously exposed to counter-attack from Catenanuova. A shortage of artillery ammunition had developed, to meet which temporary limitations were imposed upon the daily allotment to all guns except those supporting the Canadian Division (thirty rounds per gun for 25-pounders, and twenty for self-propelled guns). The 78th Division, which General Montgomery intended to commit in the centre of the 30th Corps front in “a blitz attack supported by all possible air power” on the thrust line Adrano–Bronte–Randazzo, was not expected to be ready to attack before 1 August. Time was also required to enable the American Seventh Army to develop its eastward thrust in the north of the island and for the Canadian Division to move up in the centre of the Allied front.31 It thus became the role of the Eighth Army’s right flank to hold a firm base on which the remainder of the Army Group could pivot.

Meanwhile the Allied air forces continued to exploit fully the advantages of complete air superiority over Sicily. After 21 July there was no more enemy air activity from Sicilian fields,32 which were strewn with the broken remains of Axis aircraft. By the end of the campaign Allied Intelligence, delving through the aeroplane “graveyard” which lay beside every airfield, had counted the remnants of 564 German and 546 Italian aircraft (including those captured intact). The discrepancy between these totals and enemy-reported air strengths in Sicily on D Day may be partly attributed to the inclusion in the Allied figures of many craft destroyed during the pre-invasion bombing, or which had crashed long before during training flights. The exact losses in the air are impossible to establish. The Allies reported 740 hostile craft shot down, with their own losses less than half that number. Enemy statistics admitted only 320 aircraft (225 German, 95 Italian) lost on war missions from 1 July to 5 September, while claiming a total of 640 Allied brought down during the same period, either in aerial combat or by ground flak.33

Allied fighters now patrolled all sectors of the battlefield without encountering hostile aeroplanes. As the Eighth Army began regrouping for the next, and it was hoped, final offensive, the plan of air support aimed at the isolation of the main Catania positions by systematically bombing and strafing every line of reinforcement and supply. From the night of 19–20 July to the end of the month medium and light bombers and fighter-bombers constantly attacked the ring of towns which encircled Mount Etna, and on the connecting roads no enemy transport was safe. During the last twelve days of July, including attacks on Catania Itself, aircraft under the control of the Northwest African Tactical Air Force flew a total of 1959 sorties against these targets.34

The Opening of the Struggle for Agira, 23 July

The fall of Assoro and Leonforte brought no respite to the Canadian troops, who, as we have seen, were under orders to push on with all speed. On 21 July, while the 1st and 2nd Brigades were engaged in reducing these two strongly held hill towns, Brigadier Penhale’s 3rd Brigade had moved eastward from Valguarnera to the road running north to Agira, up which the 231st Brigade had moved two days before. On the 22nd The Carleton and York Regiment crossed the Dittaino at Raddusa–Agira Station, relieving a battalion of the Malta Brigade, whose forward troops had been in contact with the enemy for two days in the hills south of Agira. The better to coordinate operations on the 30th Corps’ left flank, the Malta Brigade, which was commanded by Brigadier R. E. Urquhart, had been placed under General Simonds’ command on the 20th.35

On the afternoon of 22 July the Canadian GOC gave his four brigades detailed instructions for the capture of Agira and the subsequent reorganization for the “move east to secure Aderno*

* Renamed Adrano by Mussolini to perpetuate the ancient Adranum on which site it stood.

in conformity with the Corps plan.”36 The attack on Agira was to be made by a battalion of the 1st Canadian Brigade approaching by night along Highway No. 121, and supported in the actual assault, which would be launched early on the 23rd, by the full weight of the divisional artillery. Protection on the Division’s left flank would be ensured by placing a second battalion across the road (Highway No. 117) which led north to Nicosia; while the 2nd Brigade was to form “a firm base” about Assoro and Leonforte. On the right it was the 231st Brigade’s task to threaten Agira from the south. Supported by the 142nd Field Regiment, the brigade was to capture hill positions three miles south of the town on either side of the road from Raddusa, and exploit northward to a line, about half a mile south-east of Agira, which marked the limit of Canadian artillery targets. Simonds ordered his remaining formation, the 3rd Canadian Brigade, to remain in the vicinity of Raddusa–Agira Station (which was twelve miles by road from the town of Agira itself). At his conference on 19 July he had announced his intention that after the capture of Agira the advance eastward would be led by these two latter brigades – the 231st on the left and the 3rd Canadian on the right.37

It was little more than eight miles by road from Leonforte to the medieval town of Agira, perched high upon its mountain cone overlooking the Salso and Dittaino valleys. In this sector of its course the main Palermo–Catania highway followed what was for Sicily a comparatively direct route along the rugged plateau which separated the two river systems. The road was generally free from very steep gradients, but at least four times between Leonforte and Agira it curved over low hill barriers which crossed the plateau

from north to south. Four miles west of Agira, in the relatively flat ground between two of these ridges, lay the village of Nissoria, a small community of less than a thousand inhabitants. Because it was overlooked from the high ground to west and east, Nissoria itself was not expected to present a serious obstacle to the 1st Brigade’s advance.

On receiving instructions to attack Agira Brigadier Graham ordered the 48th Highlanders, who were in Assoro, to occupy the junction of Highways No. 117 and No. 121, a mile east of Leonforte, in order that The Royal Canadian Regiment might then pass through. Heavy artillery shelling caught the Highlanders in their forming-up area, inflicting several casualties, and their first attempt to reach the objective was driven back by machine-gun and mortar fire. When day broke the enemy withdrew over a line of hills, and the 48th established themselves just east of the crossroads. But the 2nd Brigade had not yet formed its firm base, and shortly after noon Divisional Headquarters signalled the 231st Brigade that the attack on Agira was postponed twenty-four hours. The RCR deployed to the south of the road junction, and during the day the 4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards reconnoitred to the north and east. One troop encountered enemy positions on the Nicosia highway; the other reached the western limits of Nissoria, where it was turned back by enemy mortar fire.38

Next morning (the 24th) the GOC held another conference and gave detailed orders for the capture of Agira by nightfall. The advance of the 1st Brigade was to be closely coordinated with a timed programme of artillery concentrations on successive targets along the route; a creeping smoke barrage would provide a screen 2000 yards long 1000 yards ahead of the forward troops; in front of this curtain Kittyhawk fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force would bomb and strafe targets along the road, and six squadrons of medium bombers would attack Agira and its immediate vicinity. The 2nd Canadian Brigade was to take over Assoro from the Hastings and Prince Edwards and the Nicosia road junction from the 48th Highlanders, in order to free Brigadier Graham’s battalions for exploitation beyond Agira.39 This elaborate programme, which would give the Canadians their first experience of heavy air cooperation, obviously impressed the RCR diarist, who wrote on the 24th, somewhat irreverently:

The feature [Agira] is deemed so important to gain that the Bn, which is leading the Bde, will be supported by the complete Div Arty, plus ninety bombers, plus more than a hundred fighter-bombers in close support. It is a set piece attack, with a timed arty programme, report lines, bells, train whistles and all the trimmings.

At three in the afternoon the artillery barrage from five field and two medium regiments*

* The 1st Field Regiment RCHA, the 2nd and 3rd Field Regiments RCA, the 142nd, (SP) and 165th Field Regiments RA, and the 7th and 64th Medium Regiments, RA.40

began to fall, as the leading RCR companies, supported

by “A” Squadron of the Three Rivers, set off along the highway towards Nissoria. From the excellent vantage point of the castle ruins above Assoro General Simonds with officers of the 30th Corps and members of his staff watched their progress. Eastward above the geometrically sharp lines of the escarpment which walls the broad Dittaino valley they could see the dominant Agira mountain six miles away standing out boldly against the background bulk of Etna. Lower to the left lay the flat white cluster of the buildings of Nissoria. The heavy concentrations of high explosive landed with great accuracy on their targets. All efforts to build up a satisfactory smoke-screen however were nullified by a strong breeze which blew across the field of action, even though in a rapid succession of signals to his Commander Royal Artillery General Simonds increased the intensity of fire of smoke shells from one to three rounds per gun per minute.41 It was remarked later by one of the divisional intelligence staff that in this attack the infantry had a tendency to advance too late after the artillery shelling had ceased, with the result that the Germans were then ready for them with mortar and medium machine-gun fire.* He said “that German prisoners had told him that we Canadians are very much like the British in that we are slow in following up any advantage we may have gained by an artillery barrage.”42 This failure to follow the fire support closely enough was afterwards cited by General Simonds as the fundamental cause of the reverses suffered by units of the 1st Brigade in their attacks at Nissoria.43

After some delay the Kittyhawks arrived and one by one dived down to drop their bombs along the road, but due to a break in RAF communications the scheduled attack by medium bombers did not take place.44 As events were to show, however, this failure to bomb Agira on the 24th probably did not materially affect the progress of the ground operations that day, for strong enemy opposition was to engage the Canadians in four more days of bitter fighting before they reached their hilltown objective.

The Reverse at Nissoria, 24–25 July

Led personally by Lt-Col. Crowe, the RCR covered the three miles to Nissoria without incident and successfully cleared the village, reporting it secure at 4:15 p.m.45 Almost immediately the battalion ran into difficulties. From the eastern outskirts of Nissoria the highway curved south of a wide gully to climb easily through a gap between two low hills which formed a mile-long edge 1000 yards beyond the village (see Map 4). The rocky high ground on either side of this saddle concealed

* The Divisional Artillery Task Table shows that the concentrations on the high ground half a mile east of Nissoria were to be fired from 3:30 to 4:00 p.m. It was 4:30 however before the infantry reached the eastern edge of the village.

a force of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, identified later as the 2nd Battalion, 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, with stragglers from the 1st and 3rd Battalions, and a number of artillery sub-units.46 The shelling did not achieve the desired effect upon these particular positions, either because the concentrations in general seem to have been confined to the road and its immediate vicinity, or more probably because the enemy, who were well dug in, had been allowed time to recover before the Canadians arrived. The appearance of the RCR at the edge of Nissoria was greeted by a hail of machine-gun bullets accompanied by heavy mortar fire. Crowe ordered his two forward companies to clear the ridge, sending “C’ Company around to the right of the highway to take the southern knoll, and “D” directly across the gully to the left. The latter’s objective was a solitary square red building at the highest point of the road where it crossed the ridge. This landmark was the Casa Cantoniera – the dwelling of the local highway foreman – but by the Canadians who fought around it on that and subsequent days it will always be remembered as the “red school-house”.47

“D” Company, attacking across the open gully, made little headway against the enemy fire. Its platoons became separated, and wireless contact with Battalion Headquarters in Nissoria failed. The breakdown in communications within the battalion became general, and subsequent attempts to relay messages by runner from one company to another were unsuccessful. In the resultant fog of uncertainty the sound of brisk fighting on the right flank led Crowe to believe that “C” Company had gained its objective; accordingly he dispatched his two remaining rifle companies with orders to push on through “C’s” position. An earlier attempt by “A” Company to attack the right end of the southern hill in support of “C” Company had been abruptly called back because of an additional artillery concentration on this objective which had been ordered for 5:15. In the confusion of withdrawal it lost one of its platoons, which became involved in “D” Company’s effort.

About six o’clock the battalion commander, judging from the noise of considerable firing coming from the enemy’s right rear that his companies had cleared the ridge, and anxious to re-establish wireless communication with them, moved forward from Nissoria on foot, accompanied by a small party of engineers and signallers. At the foot of the south hill they came under enemy fire. Calling out, “RCR”, Crowe pressed on, hoping to reach his troops. He was struck by a machine-gun bullet; but seizing a signaller’s rifle he engaged the enemy, until a second bullet killed him. His wireless operators fell by his side, and with the loss of their sets went hope of restoring contact with the missing companies. The Second-in-Command, Major T. M. Powers, took over the regiment.48

The virtual blackout on information which now descended on Battalion Headquarters, as reflected in the brigade message log, and the indefinite

and often conflicting reports given by companies after the action make it impossible to chart with certainty the subsequent action on the right. It appears that when “A” and “B” Companies received the battalion commander’s instructions to advance, they followed a small valley well out on the right flank, which took them south of the hill against which “C” Company had been directed. Ultimately they came upon their missing comrades, considerably behind the enemy position – to find that they too had by-passed the objective. They were now well on their way to Agira – some reports suggest within two miles of the town – but with the enemy in their rear, between them and Nissoria. The three company commanders, realizing that the battalion was out of control, held a council-of-war and decided to consolidate their forces for the night. Dawn found them under enemy observation, and brought casualties from mortar and machine-gun fire.49

In the meantime the curving mile of road east of Nissoria had been the scene of an independent and bitter action between the Three Rivers tanks and the strongly entrenched enemy on the hill south of the “red school-house”. During the approach to the village “A” Squadron had destroyed an enemy Mark III tank, and at the eastern end of the narrow main street had silenced a troublesome 88-millimetre anti-tank gun. Taking over the lead from the infantry the Shermans advanced towards the high ground, the unfavourable terrain compelling them to travel singly along the highway. Heavy fire across the valley from the hill on their left – which is named on large-scale maps Monte di Nissoria – knocked out one of the leading tanks, effectually blocking the road to those following. In the fighting that ensued the Canadian armour claimed successful hits on four German 88s. Two tanks of the leading troop patrolled through enemy territory supporting the few of the RCR who had got forward, until all their ammunition was exhausted. But the technique of successful infantry-cum-tank cooperation which brought satisfying results later in the campaign in Italy had not yet been perfected. The failure of the infantry to reach and clear the enemy positions cost the squadron dear; ten Shermans were knocked out, four of them beyond recovery.50 Casualties to Three Rivers personnel numbered fifteen, including four men killed; among the wounded were the commander of “A” Squadron and his second-in-command.

When late on the 24th it became obvious that the RCR had failed to dislodge the enemy, General Simonds ordered the 1st Brigade to renew the attack that night. Agira was the objective, and Regalbuto the limit of exploitation.51 Brigadier Graham, who had been close to the scene of action riding in one of the headquarters tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment, assigned the task to the Hastings and Prince Edwards. The CO, Lord Tweedsmuir, had not seen the ground by daylight. “The only thing”, he

wrote later, “was to get as far as possible in the darkness and hope for the best.”52 After consultation with Major Powers he decided to outflank the troublesome enemy positions by advancing south of the highway and then swinging left to cut it about a mile west of Agira.

shortly after midnight the Hastings marched into Nissoria from the west, and in the early hours of the 25th, guided by an RCR patrol, moved to the attack. The battalion advanced in its accustomed single file, with one company patrolling ahead. But the plan to reach the enemy’s rear failed. At the southern end of the ridge beyond the village “B” Company, in the lead, stumbled upon a machine-gun position. When the enemy opened fire, pinning down the leading Hastings, the remaining companies deployed and pressed on up the slopes. The German post was outflanked and overrun; but now came the deadly rattle of machine-guns from the alerted defenders all along the ridge. Lt-Col. Tweedsmuir,*

* Promoted to this acting rank on 22 July.

who was fighting his last action in Sicily (he was wounded and evacuated that morning), thus describes the situation:

The Battalion formed a rough square on the hilltop. The light came up and there were plenty of targets to shoot at as the Germans moved about the slopes. Then the mortar fire started. Their object was to fill in the gaps in the geometrical patterns made by the machine-gun fire, and with extraordinary accuracy they did it. The number of wounded began to mount up. ... A wounded man was repeating over and over again “Give ‘em Hell, Tweedsmuir, give ‘em Hell”, as we called the artillery on the radio.53

But the withering fire which pinned the Canadians to ground – the enemy mortars and medium machine-guns were being supported by three well dug-in Mark III tanks – made it impossible to pick good artillery targets or to find a suitable position from which to observe. The Hastings were in a serious predicament. The steady rate of fire which they were maintaining had left their stock of ammunition dangerously low; to attempt further advance, or even to remain in such exposed positions, might well have meant the loss of most of the battalion. A withdrawal was ordered, and under rearguard protection given by “D” Company, they fell back behind Nissoria. Tweedsmuir, who had suffered a severe leg wound from a mortar bomb, turned over command of the regiment to Major A. A. Kennedy.54

During the morning two RCR carriers had reached their battalion’s forward companies in the hills east of Nissoria and recalled them to a concentration area near Assoro. Here the regiment reorganized from its dislocation of the previous day. The brigade’s second attempt to dislodge the Panzer Grenadiers had failed, and the casualties were mounting. The cost to The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment had been five officers and 75 other ranks killed, wounded and missing – the heaviest losses suffered in

a single day by any Canadian unit during the entire campaign in Sicily. In their two days’ fighting the RCR had lost in addition to their Commanding Officer, three officers and 43 men, of whom sixteen had been killed.

That evening Graham sent his remaining battalion, the 48th Highlanders, against the stubborn enemy. To avoid the dispersion which had dissipated the RCR’s effort, he directed that the left flank should be tested by a single company attack, and if this succeeded the remaining companies would follow through in succession and wheel out into the enemy’s positions along the ridge. Lt-Col. Johnston launched his attack at six in the evening, directing “B” Company against Monte di Nissoria at the northern end of the long feature, after medium machine-guns of the Saskatoon Light Infantry had searched the rocky hillside with their fire.55 At first there was little opposition, and the Highlanders quickly reported themselves on their objective. “D” Company now entered the attack, climbing the steep terraced position to the right of “B” Company. Soon word came back of strong resistance, for “B” Company had reached only a false crest, and the Germans above them were holding the summit and the reverse slopes of the escarpment, where they had been comparatively safe from the Canadian machine-gun fire and artillery concentrations. Harassed by enemy fire both Highlander companies were forced to find what shelter they might on the narrow ledges below the German positions. Johnston attempted to call new supporting fire, but once again wireless sets, their range considerably reduced by the screening of intervening hills, proved ineffectual. The two forward companies now found themselves out of communication with Battalion Headquarters, and after nightfall they withdrew from their untenable positions. In the meantime “C” Company, sent forward on the right of “D”, halted when overtaken by darkness, and about midnight assaulted its objective, the Casa Cantoniera, north of the road. Enemy tanks and machine-guns held off the Highlanders, and on Johnston’s orders the attempt was abandoned. The battalion withdrew west of Nissoria, having suffered 44 casualties, including thirteen killed.56

The 48th Highlanders’ difficulties in maintaining wireless communication were of a pattern with those frequently experienced by other Canadian units during the fighting in Sicily. After the campaign General Simonds reported to the 15th Army Group that whereas wireless communications behind brigade headquarters were excellent throughout the Eighth Army, those from brigade headquarters forward had fallen behind requirements. It was his view that the No. 18 set – the portable man pack wireless set in use down to headquarters of infantry companies – “did not meet the range demanded to control an infantry brigade when dispersed over a wide front and/or in great depth.”57

The mountainous terrain through which the Canadians were operating produced freak conditions which seriously restricted wireless reception,

particularly at night – a problem not encountered by the other formations fighting in the Catania plain. Much of the trouble appears to have been caused by faulty batteries; the extreme heat was blamed for deterioration of the chemicals. On 28 July the war diary of the 1st Canadian Divisional Signals recorded “difficulty in 18-set battery supply. Batteries coming up are duds or very weak.” And at the end of August Headquarters 15th Army Group noted that “large quantities of the old unreliable pattern batteries for wireless sets No. 18 continue to arrive in this theatre. Of these, between 60% and 70% are completely exhausted when received.”58 It will be recalled that the 1st Division had lost a considerable amount of signal equipment in the convoy sinkings. The resultant shortage had imposed a severe strain in maintenance; with the lack of spares sets broke down faster than they could be repaired.59

As reports of the ineffectiveness of the No. 18 set in the fighting before Agira multiplied, the Canadian GOC gave orders for the more powerful No. 22 set to be made available to forward units on a scale of six to a brigade. These heavy sets had been used during the landings, where they were transported on special handcarts. The carts had not proved very satisfactory, for the narrow-tyred wire wheels dug deeply into the sand of the beaches, and were too lightly constructed to withstand the rough passage over the stony tracks farther inland. The sets would now be carried by sturdy and sure-footed pack mules.60

The Winning of “Lion” and “Tiger” Ridges, 26 July

It was now the turn of the 2nd Canadian Brigade to enter the battle; but before proceeding with the story of its participation, we may glance briefly at what was happening on the right in the 231st Brigade’s field of operation. It will be recalled that on 22 July, when he issued the first orders for the capture of Agira, General Simonds had assigned the Malta Brigade the role of threatening the town from the south, while the main attack went in from the west. On the night of the 22nd the brigade, which was astride the Raddusa–Agira road, seized two strongly defended hills 4000 yards south of Agira, the 2nd Battalion, The Devonshire Regiment, taking the left position, Point 533,*

* Designated by the altitude in metres.

and the 1st Battalion, The Dorsetshire Regiment, Point 482,* east of the road. At midday on the 23rd Brigadier Urquhart received word of the postponement of the 1st Canadian Brigade’s attack; and that night he moved forward his third battalion, the 1st Hampshires, in readiness for a coordinated effort with the Canadians on the 24th.

About a mile to the east of Agira Highway No. 121 was commanded by two prominent hills which were dominated only by the Agira mountain itself. To the north of the road was Mount Campanelli, 569 metres high; to the south, in the angle between the highway and the road to Raddusa, was a somewhat higher feature closer to the town and under complete observation from the Agira heights. It was named on large-scale maps Mount Gianguzzo, but was always referred to by the Malta Brigade as Point 583. On the night of 24–25 July, while the RCR were making their fruitless attempt east of Nissoria, the Hampshires gained positions astride the highway, prepared to intercept Germans retreating from Agira when the town should fall. An early morning report that the Canadian attack had failed brought a change in plan, and two companies of the Hampshires were ordered forward to Mount Campanelli, with instructions to lie low throughout the day. Partially screened from view by rows of vines and cactus hedges they spent the morning of the 25th watching enemy traffic on the highway and on the secondary road running north from Agira to Troina. The Germans were using these two escape routes freely, and many tantalizing targets were presented to the Hampshires, who dared not, however, disclose their presence on Campanelli. Yet the enemy’s suspicions were evidently aroused, for at mid-afternoon he counter-attacked the hill, and compelled the Englishmen, who were without mortars or artillery support, to withdraw south of the highway.61

That night, as the 48th Highlanders unsuccessfully tried to force the German defences east of Nissoria, the 231st Brigade again cooperated. Two Hampshire companies worked their way in the darkness on to Mount Campanelli, with orders to withdraw at first light if the Canadian effort failed. The Dorsets got patrols on Point 583. But the Highlanders did not break through, and the troops from both battalions of the Malta Brigade fell back at daybreak as planned.62

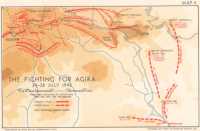

Preparations were now made for a fresh effort from the west. Early on 26 July General Simonds ordered the 2nd Brigade to relieve the 1st and to launch an attack against Agira that evening. The GOC directed that the operation should take place in two stages: an advance by one battalion under a heavy barrage to seize and consolidate a firm base 2300 yards in depth east of Nissoria, and a subsequent exploitation by a second battalion to the high ground which overlooked the western entry to Agira. In his detailed plan Brigadier Vokes selected Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry to carry out the first phase of the attack. The unit’s objectives were the ridge east of Nissoria which, had cost the 1st Brigade so much bloodshed, and a second feature of equal height a thousand yards nearer Agira; these were given the code names of “Lion” and “Tiger” respectively. From an assembly area within an hour’s march of “Tiger” the Seaforth

The fighting for Agira, 24–28 July 1943

Highlanders would be prepared, on thirty minutes’ notice, to move forward and seize the final objective, “Grizzly”, a stretch of high ground within half a mile of Agira rising at either end to a well-defined crest – Mount Crapuzza north of the highway, and Mount Fronte to the south.63

At 8:00 p.m. the crash of high explosive shells on a mile-long front across the highway immediately east of Nissoria signalled the commencement of the heaviest barrage yet fired by the artillery of the 1st Canadian Division.*

* The fire plan provided for 139 rounds per gun. In the series of concentrations fired in support of the attack on 24 July the demands upon each battery averaged not quite sixty rounds per gun.64

For seventeen minutes eighty guns of the three Canadian field regiments and the 165th Field Regiment RA concentrated their fire on the opening line; then the barrage lifted and moved eastward along the highway in twenty-eight successive steps, advancing one hundred yards in every three minutes.65 The effect upon the enemy was paralyzing. Supported by guns of the 90th Anti-Tank Battery and by the tanks of the Three Rivers’ “C” Squadron, “C” and “D” Companies of the Patricias, following closely upon the barrage, swept rapidly on to their objectives, respectively the right and left crests of “Lion”. They took these without difficulty, for the Germans were shaken and demoralized by the intensity of our attack. One dazed prisoner who had fought in Poland, France, Russia and North Africa, declared that he had never before experienced such devastating fire;66 a captured officer is said to have asked to see the “automatic field gun” which was capable of producing such an incredible rate of fire!67 The Patricias took more than seventy prisoners, and it was later reported that of those defenders of the ridge who were not killed or captured few escaped unwounded.

Now the barrage paused for twenty minutes, to allow the PPCLI reserves to move up for their attack on “Tiger”. Unfortunately these companies, “A” and “B”, probing forward in the darkness over the rugged, unfamiliar ground, lost their way and with it the advantage of the barrage when it began again. The brief respite in the shelling allowed the Germans to get their heads up, and a bitter fight ensued. Neither PPCLI company reached its objective.68 Although wireless communication appears to have been maintained unusually well, uncertainty of companies about their own positions, coupled with the inevitable “fog of battle” which cloaked the battalion’s movements, left Brigade Headquarters with a confused picture of the situation. It was not clear whether “Tiger” had yet been taken. At midnight, therefore, Vokes decided to commit the Seaforth Highlanders, in the hope that aggressive action would bring a clear-cut decision in our favour.

The Seaforth, deploying on either side of the road outside Nissoria, mounted the “Lion” objective, where they were held up by fire from a

number of well-concealed medium machine-guns and tanks. While “A” Company engaged and knocked out the machine-gun posts, a troop of Shermans, assisted by anti-tank guns of the supporting battery, effectively quelled the opposition of the German armour, destroying at least two enemy tanks. The company now pushed ahead, and at 4:25 a.m. sent back the report, “Forward elements on ‘Tiger’.” With grim tenacity the enemy clung to his hold on the high ground, meeting the Seaforth assault with fire from flanking machine-gun nests and tanks in hull-down positions on the reverse slope of the crest. Once the infantry had secured a footing however, anti-tank guns were rushed forward, followed closely by the Seaforths’ “B” Company. There was more bitter fighting, in which “A” and “B” Companies of the Patricias played an important part, and by 11 o’clock “Tiger” ridge was firmly in Canadian hands.69

From their hard-won vantage point the Canadian artillery, tanks and infantry had an excellent field of fire over the stony fields to the high ground of “Grizzly” two miles to the east, and to the north, where the land fell steeply away across the Agira–Nicosia road into the broad valley of the Salso River. During the morning several German tanks and machinegun posts were spotted and destroyed, and a number of retreating vehicles and infantry paid the penalty of being caught in the open by our guns.70

The enemy’s use of the road to Nicosia had already been interrupted by Canadian troops. Nicosia, fifteen miles to the north-west, was under attack by the American 1st Division, and there was much shuttling of Axis traffic forward and back between the two threatened towns. It was too good an opportunity to miss, and on the night of 26–27 July The Edmonton Regiment was ordered to send a fighting patrol well out on the northern flank to cut the road. “D” Company carried out a difficult six-mile cross-country march, routed an enemy post with a sudden bayonet charge in the darkness, and before rejoining the battalion successfully established a platoon astride the road three miles from its junction with Highway No. 121. By means of well placed “Hawkins” grenades

* The No. 75 (“Hawkins”) grenade, of weight 2¼ lbs., could be lightly buried like an anti-tank mine, or thrown directly in the path of a moving vehicle. It was also used as a portable demolition charge.

and some remarkably cool-headed and effective handling of the PIAT, this platoon accounted for no less than three enemy tanks, a large tank-transporter and three lorries. On the afternoon of the 27th the position was strengthened by the arrival of “C” Company. Next day the Edmonton force drove off three counter-attacks of varying strength, as enemy pressure came alternately from the north and the south. While continuing to block the road the company also contrived to blow up an enemy ammunition dump, and to capture a truckload of hospital brandy. Late on the 28th an Edmonton carrier brought orders to rejoin the battalion. The episode was an example of the effective employment of a small detached

force, and was matched on the following night by the work of another strong fighting patrol sent by the Edmontons to investigate enemy positions north of Agira. Commanded by a sergeant of the Support Company the patrol, about two platoons in strength, surprised an estimated 200 Germans in the hills north of the Salso and routed them with mortar and machine-gun fire. They counted 24 enemy dead and took nine prisoners.71

Kesselring reported on the operations of 27 July: “A strong attack of 1 Canadian Inf Div has been repelled up to now”; and later, “In the afternoon renewed attacks of strong forces on Agira.”72 But a captured operation order of the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, dated 27 July, admitted that the Germans had been forced to give ground.

15 PG Div, under strong enemy pressure, is taking up positions adjoining HG Armd Div back on the general line Regalbuto–Gagliano–east of Nicosia, leaving a standing patrol in area Agira ... Contact will be established and maintained between Regalbuto and the left flank of 15 PG Div and any enemy elements infiltrating between the flanks of the two divisions will be spotted and wiped out.73

The “standing patrol” whose fate it was to fill the gap between the two major formations proved to be the entire 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment,*

* As noted earlier (p. 116) this battalion was operating independently of its parent regiment, which was opposing the United States 1st Division’s advance in the Nicosia area.

of the 29th Division – fresh troops who had been hastily moved into defence positions along “Grizzly” to replace the decimated battalions of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.74

The Capture of “Grizzly” and the Entry into Agira, 27-28 July

The renewed attacks to which the C-in-C South had referred started at midday, as Allied medium bombers struck Agira and Kittyhawks strafed and bombed enemy positions west of the town. At two o’clock Brigadier Vokes sent the Seaforth against the “Grizzly” objective, supporting them with artillery, medium machine-guns, anti-tank guns and two troops of Shermans. To the right of the highway “A” Company, commanded by Major H. P. Bell-Irving, advanced upon Mount Fronte, a square-topped hill with a precipitous southern flank. One enemy company was firmly installed upon this commanding height, and it poured such a volume of machine-gun and mortar fire down the forward slope as to make a frontal attack on the feature impossible.

Accordingly Major Bell-Irving decided on a right-flanking movement, and an assault up the face of the cliff, next to impossible though the feat might seem. The operation was brilliantly successful. While one platoon

energetically held the enemy’s attention by their fire and infiltration from the west, the remainder of “A” Company, making skilful use of the cover afforded by terraced orchard and vineyard, reached the southern base of the mountain and scaled the 300-foot cliff. Completely taken by surprise the enemy nevertheless fought back strongly; but the Seaforth hung grimly on, and by employing admirable tactics of fire and movement executed with great determination, secured a commanding position, which they held throughout the night against counter-attacks. Early in the morning, as reinforcing companies arrived on the scene, Bell-Irving launched a final attack with rifle and grenade. So vigorously was the assault pressed forward that the enemy fled in complete disorder “literally and actually screaming in terror”. By six the whole of Mount Fronte was in Canadian hands.75

On the north side of the highway the attack by “D” Company during the afternoon of the 27th had been halted by the vehemence of the German fire. The immediate objective was a sprawling hill at the left centre of the “Grizzly” ridge, of about equal height with Mount Crapuzza half a mile to the north, and bearing on its summit a walled cemetery characteristically bordered by tall, sombre cypress trees. The south-eastern slopes of “Cemetery Hill” ran down to the outlying buildings of the town itself, which was spread over the western slopes of the towering cone of the Agira mountain. Lt-Col. Hoffmeister, realizing that one company could not successfully dispute the enemy’s possession of the hill, withdrew “D” Company into reserve, in order that he might concentrate his forces against Mount Fronte. The wisdom of this decision was vindicated, as we have seen, by the Seaforth success on the right. For their outstanding part in directing and carrying out the Seaforth operation against “Grizzly” both the battalion CO and his gallant company commander, Major Bell-Irving, were awarded the DSO.76

Late that afternoon Brigadier Vokes, realizing the need for a more powerful effort against the northern end of “Grizzly”, ordered The Edmonton Regiment into action. The battalion set off at eight o’clock, swinging wide to the left through country broken by hills and ravines, intending to attack Mount Crapuzza and Cemetery Hill from the north. But the route was difficult beyond expectation, and the maps which the Edmontons carried proved unreliable. By the time they reached the point from which the final assault was to be launched, an artillery concentration, intended to support their attack, had been completed several hours before.77

It was shortly before three in the morning when the attack finally went in, with “A” Company directed against Mount Crapuzza and “B” and “D” against Cemetery Hill. “B” Company found itself faced by an almost precipitous slope on which the alerted enemy was dropping heavy concentrations of mortar fire while his forward troops lobbed down “potato masher” grenades from the heights above. While “B” was thus pinned to ground

with quickly mounting casualties, “D” Company, farther south, managed to work a section of men around to the right of the hill. This daring little party created so effective a distraction in the enemy’s rear that the remainder of the company, rallied by the second-in-command when the commander was killed, assaulted the cliffs, and with 2-inch mortars, hand grenades and Bren guns carried Cemetery Hill against opposition estimated at four times their numerical strength. The enemy broke into disorganized retreat, many suffering further casualties as they came under fire from the Edmontons’ “A” Company, which had in the meantime established itself upon Mount Crapuzza without opposition.78 The night’s work had cost the Edmontons three killed and 31 wounded; but at 8:55 a.m. Brigadier Vokes was able to send Divisional Headquarters the satisfying message:

Whole of Grizzly in our hands. Nearly all enemy killed. Survivors retreating northwards. We have lost contact. All approaches safe.79

On the two preceding nights the 231st Brigade had played their now familiar role for the third and fourth times, on each occasion putting small parties astride the road east of Agira in anticipation of the capture of the town by the Canadians. The coming of daylight on the 27th compelled the accustomed withdrawal of their patrols from Mount Campanelli and Point 583; but on the following morning the 2nd Canadian Brigade’s success enabled Brigadier Urquhart’s forward troops to retain their footing on these important positions. During the day Devons and Dorsets put in spirited attacks to consolidate their hold, and by nightfall the Malta Brigade was firmly astride the main highway, and ready to lead the divisional attack eastward against Regalbuto. In these operations the support of “A” Squadron of the Three Rivers Regiment, which came under Brigadier Urquhart’s command on the 27th, was very welcome, for the brigade had parted from tanks of the 23rd Armoured Brigade at Vizzini, and from that time forward had been thrusting deep into enemy country with “soft skin” vehicles only.80

The final scene in the prolonged battle for Agira was enacted on the 28th. Determined to take no half measures, the Commander of the 2nd Canadian Brigade ordered a bombardment of the town with all available artillery and mortars to commence at 3:45 p.m. Immediately afterwards Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry would go into the town. But the population were spared the destruction of their homes by Canadian shells, for about noon an officer of the 1st Canadian Field Regiment, whose eagerness to select a good vantage point for his task of observing fire for the Patricias had carried him right into Agira, found no sign of enemy activity, but streets crowded with people who gave him an enthusiastic welcome. The bombardment was cancelled, and at 2:30 two PPCLI companies entered the town. They received an ovation from the populace on the outskirts; but as they climbed the steep streets into the heart of Agira they met a different kind of welcome

from enemy pockets of resistance. It required two hours of fairly stiff house-to-house fighting and the employment of a third rifle company, as well as assistance from a squadron of tanks, to clear the town.81

So Agira fell, after five days of hard fighting in which practically the whole of the Canadian Division, with the exception of the 3rd Brigade (whose place was in effect taken by the 231st Brigade) had been engaged. It was the Division’s biggest battle of the Sicilian campaign and it cost 438 Canadian casualties. (This includes neither the losses of the 3rd Brigade, which was engaged in a separate action, nor those of the 231st Brigade, which suffered approximately 300 casualties during the fighting for Agira.*)

* Exact casualty figures for the 231st Brigade for this period are not available. An indication of the losses suffered is shown in a report in the 1st Hampshires’ war diary of 26 casualties sustained by the unit on 26 July and 83 on the 27th. The total of 300 is taken from the published story of the brigade’s operations in Sicily.82

In its early stages the battle provided the enemy with an opportunity of strikingly demonstrating the principle of economy of effort. Because the extremely rugged nature of the country prevented deployment on a large scale, the six battalions of the 1st and 2nd Canadian Brigades had been committed one by one against the stubborn defenders of the Nissoria–Agira road. Thus in the early stages of the action the Canadians attacked on a single- or two-company front, a procedure which enabled the enemy, although numerically inferior to the total force opposing him, to concentrate the fire of his well-sited weapons upon the relatively small threatened area. It was not until the last two days of the battle, when the 2nd Brigade used more than one battalion at critical moments – the Seaforth to turn the tide of the Patricias’ assault on “Tiger”, and the Edmontons to assist the Seaforth against “Grizzly” – that the desired momentum was achieved and the issue was at last decided.

The enemy had been hit heavily. The 1st Division’s intelligence staff estimated that 200 of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had been killed, and 125 of the reinforced 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which relieved it. We took 430 German prisoners, and 260 Italians, remnants from the 33rd and 34th Infantry Regiments of the Livorno Division, and from the 6th Regiment of the Aosta Division, which had been brought down from Nicosia without supplies or supporting arms to bolster the German defences of Agira.83

These battered battalions of Panzer Grenadiers did not again oppose the 1st Division in Sicily, and there is good reason to suppose that they desired no return engagement.†

† On 1 August the 2nd US Corps identified the 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, at Gagliano, midway between Agira and Troina; what was left of the 104th Regiment showed up next day north of Troina.84

They had met Canadian troops at close quarters and had painfully experienced the impact of what one prisoner called “their tenacious fighting spirit in the face of concentrated fire.” From interrogations

conducted after the capture of Agira the CO of the Patricias reported a German dislike of hand-to-hand and night fighting:–

They consider that our troops are not only too persistent in their manner of fighting, but also extremely unorthodox – that is to say, they do not manoeuvre in the manner the enemy expects them to.85

On the Canadian left flank Nicosia fell to the American 1st Division on the same day as Agira. A score of miles farther north on the 2nd US Corps’ coastal flank the 45th Division pushed to within four miles of San Stefano, which the strongly resisting 29th Panzer Grenadier Division did not relinquish until the 31st.86 The relief of the 1st Canadian Brigade in Leonforte on 27 and 28 July by advanced troops of the 9th Infantry Division heralded the regrouping which was taking place preparatory to the major American drive eastward. Palermo harbour was opened to shipping on the 27th, and the bulk of the Division disembarked there from North Africa on 1 August.87

For the 1st and 2nd Canadian Brigades there was a brief period of recuperation, during which much-needed reinforcements were brought forward from the beach areas, where they had been waiting since their landing on 13 July.88 It is not to be wondered that the war diary of almost every unit should make special note of a five-hour rain storm which swept over the hills on 28 July, for it was the first precipitation that the Canadians had encountered in their hot and dusty journey through Sicily. The 48th Highlanders reported that “all ranks including the CO took advantage of it and held impromptu shower baths out in the rain”. On the evening of the 30th the Seaforth pipes played “Retreat” in the town square of Agira, to the huge gratification of the assembled townspeople. The unit diarist reported, with understandable pride, that “it was heard in London and broadcast over the BBC.”

The people of Agira, and indeed of every Fascist-ridden city, town and village in Italy, felt that they had good cause for rejoicing in those last days of July 1943. Late on the evening of the 25th a dramatic announcement by the Rome radio struck the country like a thunderbolt:

His Majesty the King and Emperor has accepted the resignation of the head of the Government, the Chancellor and State Secretary, tendered by His Excellency Cavalier Benito Mussolini.89

The wheel was come full circle, and the irresponsible dictator, who in May 1940, on the eve of his treacherous attack on France, had declared, “I need a few thousand dead so as to be able to attend the peace conference as a belligerent”,90 now found himself toppled from his pedestal by the turning fortunes of the struggle into which he had so blithely plunged his unhappy country.

“It is defeat in war that brings about the fall of a regime”, wrote Mussolini during the following winter, in a series of articles, History of a Year, published by a Milan newspaper.91 The political crisis which precipitated his downfall he attributed, and with good reason, to the military crisis which had arisen in Sicily. The Italian people had come to realize that the loss of the island was imminent. Already disillusioned by the North African disaster, and faced with the prospect of aerial bombardment of their towns and cities and an impending invasion of the Italian mainland, their resentment was strong against the man who had plunged them into war. The picture drawn by Marshal Badoglio is probably not exaggerated:

Conscious of our complete helplessness, the morale of the people rapidly deteriorated; in trains, in trams, in the streets, wherever they were, they openly demanded peace and cursed Mussolini. Anger with the Fascist regime was widespread, and everywhere one heard: “It does not matter if we lose the war because it will mean the end of Fascism.”92

Events in the coup d’état moved rapidly. On 19 July the Duce met Hitler at Feltre, where, in spite of earlier assurances to his Chief of Staff that he would impress upon the Führer the impossibility of Italy’s remaining in the war, he appears to have said nothing to interrupt the usual harangue of his Axis partner.93 He returned to Rome next day, to find that during his absence in the north the city had suffered its first air raid. The attack had been directed with great accuracy against the city’s marshalling yards and the nearby Ciampino airfield by 560 bombers of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force. These dropped more than 1000 tons of bombs, inflicting severe damage upon railway installations and rolling stock and nearby industrial plants.94 The raid on their capital struck a heavy blow at the already sagging morale of the Italian people, and the clamour for a cessation of hostilities became louder than ever. But there could be no withdrawal from the war as long as the dictator remained in power. Leading Fascists insisted that he summon the Grand Fascist Council, which had last met in 1939. On the night of the 24th, in a session which lasted for ten hours, he bowed to the Council’s demands for his resignation. Next morning he was taken into “protective custody”, and King Victor Emmanuel called on the 71-year old Marshal Pietro Badoglio to become head of the Government.95

The new Cabinet’s first action was to announce the dissolution of the Fascist Party. The war would go on, said Badoglio; but Hitler was under no delusion regarding the new regime’s intentions. As we shall note in a later chapter, the German High Command had foreseen a possible Italian defection from the Axis, and as early as May 1943 had planned measures to be taken in such an eventuality.96 Within 48 hours of Mussolini’s deposition German infantry and armoured formations were massing along the northern frontier. On 30 July Rommel (see below, p. 196) gave the

signal for a special task force to occupy the Brenner and the other passes, and a continuous stream of German troops began pouring down into Italy.97

The 3rd Brigade in the Dittaino Valley

For the past week, while the fighting along Highway No. 121 was in progress, the 3rd Canadian Brigade had been following a parallel axis down the Dittaino valley towards Catenanuova, an unpretentious and dirty village on the river flats about fifteen miles east of Raddusa–Agira station (see Map 5). Its role, as set forth in a divisional operation instruction of 24 July, was restricted to active patrolling eastward until a decision should have been reached in the battle for Agira. By the night of the 24th Brigadier Penhale’s three battalions were holding positions about the tiny hamlet of Libertinia and Libertinia Station, roughly four miles east of the Raddusa–Agira road. The West Nova Scotia Regiment, on the brigade’s right flank, was in touch with a unit of the 51st Highland Division (the 2nd/4th Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment) on Mount Judica, a 2500-foot peak four miles south of the river. On 26 July orders came for the 3rd Brigade to advance as quickly as possible and take Catenanuova, for its capture was a necessary preliminary to the offensive which the 78th Division was to launch at the end of the month.98

Topographically speaking the western approach to Catenanuova was relatively easy, for road and railway were laid along the flat floor of the Dittaino valley, through which the river meandered from side to side in sweeping loops that sometimes reached a mile in width. From either edge of the river plain, however, the land rose sharply in a confused scramble of hills and ridges, affording excellent defence positions from which to oppose the eastward advance of a military force. An indifferently matched pair of these heights dominated the valley a short distance from Catenanuova – Mount Santa Maria, a bald, rounded hill 800 feet high, on the north side of the river, about a mile west of the village; and to the south, Mount Scalpello, a much more massive feature whose rocky ridge towered in a long razor-back nearly 3000 feet above the road.

The securing of both of these hills was a prerequisite to an assault on Catenanuova itself. This task the Brigade Commander entrusted to the Royal 22e Regiment, intending that The West Nova Scotia Regiment would then pass to the south of Scalpello and launch an attack upon Catenanuova across the dry bed of the Dittaino. In order that there might be complete coordination on the brigade’s right flank the Hampshire battalion was temporarily placed under Brigadier Penhale’s command,99 and arrangements were made for artillery support to be given by the Highland Division.*

* The 57th and 126th Army Field Regiments RA and the 64th Medium Regiment RA.100

On the evening of the 26th Lt-Col. Bernatchez directed his “A” Company against Mount Santa Maria and ordered “B” Company to push forward to the Scalpello ridge, the crest of which had already been reached by the Hampshires, although there were still Germans on some of the outlying spurs. Advancing from Libertinia Station along the rough river bed, the banks of which were cut deeply enough to provide appreciable cover, the company on the left came within striking distance of its objective, and after a short but heavy artillery bombardment charged the Santa Maria hill with fixed bayonets. The enemy responded sharply with the usual machine-gun and mortar fire, and in the opening phase of the action the company commander was killed. It took many hours of determined effort and some skilful tactical manoeuvring over the ploughed fields and stubble by the Royal 22e platoons before the Germans, who were estimated at company strength, were finally driven from Santa Maria.101

On the right “B” Company worked their way along the northern slope of Mount Scalpello under cover of darkness, being considerably aided therein by information obtained from a friendly French-speaking peasant woman. At dawn they surprised a party of Germans on the eastern end of the mile-long ridge, and, failing to procure an artillery concentration, attacked with the support of only their own mortars. The enemy replied in kind, and with the added advantage of 88-millimetre guns which threatened to turn the tide against the Canadians. A vigorous rally by “B” Company saved the day, however, and by late afternoon, when “C” Company had come up on the immediate left, the whole mountain with some ground immediately to the east was free of enemy. The situation of the Royal 22e was unenviable, however, for their forward troops were fatigued and hungry – some had been without food or sleep for 36 hours – and the large number of mines with which the Germans had sown the valley made it impossible to bring up supplies immediately. The company on Santa Maria was particularly hard pressed, for at 6:00 p.m. the enemy began a counter-attack under cover of a barrage of mortar and artillery fire. It had already been decided to withdraw the forward troops after dark, and this was accomplished by about 9:30, the companies taking positions at the north-eastern base of Mount Scalpello.102

Their second action of the campaign had so far cost the Royal 22e Regiment 74 casualties, including one officer and seventeen other ranks killed. But even though the Santa Maria hill was again in German hands, the effort of the battalion had not been in vain. The enemy had suffered heavy losses, and, as subsequent patrolling revealed, he had abandoned his positions south of the Dittaino River. Furthermore, during the afternoon of 27 July, on the 3rd Brigade’s right flank The West Nova Scotia Regiment, profiting by the enemy’s preoccupation with the fighting on Scalpello, had

been able to make an apparently unobserved advance south of the ridge to an area about two miles south-west of Catenanuova.103

During the 28th the West Novas lay in concealment, ignored by the German artillery, which continued to harass the more exposed positions of the Royal 22e, who suffered another score of casualties. Platoons of the 4th Field Company RCE worked busily clearing the river road of mines, reconnoitring routes across the Dittaino (for all the bridges had been blown) and developing a mule path south of the Scalpello ridge into a track along which the brigade’s fighting vehicles could move forward without being under observed fire.104 Catenanuova was still ‘to be taken, but further action by the 3rd Brigade was temporarily postponed. The capture of this objective now became part of a much larger operation, and the pattern of Canadian activities had to be carefully woven into the wider design.

Preliminaries to Operation “Hardgate” – The Catenanuova Bridgehead, 29–30 July

At a meeting between General Alexander and his two Army Commanders at Cassibile on 25 July arrangements were completed for the dual offensive which was timed to begin on 1 August.105 The Seventh Army’s role, as set forth in a directive issued by General Patton on 31 July, was to advance eastward from the San Stefano–Nicosia road on two axes, the coastal Highway No. 113, and the parallel inland route, Highway No. 120, from Nicosia to Randazzo. The thrust would be made by the 2nd Corps, strongly reinforced, which was enjoined to maintain “a sustained relentless drive until the enemy is decisively defeated.”106

On 27 July General Leese issued his written orders for Operation “Hardgate”, the Eighth Army’s part of the Army Group effort. The 30th Corps was charged with the main attack, which was directed at breaking the “Etna Line” by the capture of Adrano; but on the Army’s right flank the 13th Corps was to perpetrate a deception measure designed to mislead the enemy into expecting a major blow in the Catania sector. On the successful completion of the action on the left the 13th Corps would be prepared to follow up the probable enemy withdrawal from the Catania plain. Two divisions were to make the assault on Adrano – the 78th along the thrust line Catenanuova–Centuripe–Adrano, and on the left the 1st Canadian Division, through Regalbuto and down the Salso valley. On the Corps right the 51st Highland Division was to assist by occupying the high ground east of the main axis, in order to secure deployment areas for artillery within range of Centuripe and Adrano.107

A tentative time-table for the projected operations set the night of 30–31 July for the Canadian attack against Regalbuto, and the night of 1–2 August for the 78th Division’s assault on Centuripe. As a preliminary to these actions, the opening phase of the “Hardgate” operation would be the capture of a bridgehead at Catenanuova by the 3rd Canadian Brigade on the night of 29–30 July, for which task it would come under the command of the 78th Division. The newly arrived division would then take over this bridgehead as a base from which to launch its attack northward. The air forces would give support by “full-scale bombing” of Paterno throughout 31 July, Centuripe from noon on 1 August, and Adrano and its surrounding villages “at any time from now onwards”.108