Chapter 11: Ortona

December 1943

The Advance from the Moro, 10–11 December

Now that supporting arms could cross the Moro, the 2nd Brigade prepared to continue the advance to the Orsogna–Ortona road. On the morning of 10 December Brigadier Hoffmeister ordered The Loyal Edmonton Regiment to secure an intermediate objective half way across the San Leonardo plateau and then press on to “Cider” crossroads, the vital intersection of the old Highway No. 16 with the Orsogna lateral. The day was wet and the ground boggy.1

At nine o’clock the battalion broke out from San Leonardo, with “C” Squadron of The Calgary Regiment and a platoon of the Saskatoon Light Infantry in support, and two companies of the 48th Highlanders, temporarily under Lt-Col. Jefferson’s command, providing a firm base.2 So rapid was the initial advance, there seemed good prospects that the crossroads might be captured early in the day and that it would be possible for Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry to exploit towards Ortona.3 At ten Jefferson signalled, “We are now proceeding on final objective.”4 Air strikes which had been ordered on the crossroads were accordingly called off.5 At 1:30 word came that three companies had reached their goal.6 This optimistic message had been sent prematurely, however, for the Edmontons (if indeed in their unfamiliarity with the ground they were really on their objective) were almost immediately driven back by the force of the enemy’s superior fire. As we shall see, there were to be many days of furious fighting before the “Cider” crossroads was in Canadian hands.

The deep gully already referred to, which the 90th Panzer Division had picked as its next defence position, cut into the plateau from the sea, paralleling the Ortona lateral at a distance of from 200 to 300 yards. It was bridged by the old Highway No. 16 at the bottom of a long, hairpin bend in the road, and thence continued inland for another 1000 yards before merging into the surrounding level ground. The enemy had chosen well. The Gully – it bears, and needs, no other designation to distinguish it from a thousand other ravines

which lay athwart the Canadians’ path in Italy formed a complete tank obstacle, and German weapon-pits constructed in its steep bank were practically immune from damage by our shellfire, which fell harmlessly on the level ground to the front and rear. Experience was to show that the mortar was the only weapon with which the Canadian attackers could successfully reach into this narrow cleft.

In the late afternoon of the 10th a company of the 200th Panzer Grenadier Regiment supported by self-propelled guns launched a sharp counter-attack against the Edmontons’ right flank. It was beaten off, but not before three Calgary tanks had been knocked out.7 As darkness fell the Edmontons consolidated with the remaining armour on the San Leonardo side of the Gully. A grim incident had accounted for several of the 27 casualties sustained by the battalion during the day: German machine-guns opened fire upon a platoon which was accepting the surrender of a group of Grenadiers who had come forward with their hands up. By order of General Vokes the atrocity was publicized throughout the Division as a stern reminder of the need for constant vigilance against treachery.8

The Edmontons’ failure to capture “Cider” crossroads had not been confirmed in time to prevent the PPCLI from being committed to what was intended to be an exploitation, but which resulted in the battalion becoming involved in indecisive action east of the Gully: While moving up in the wake of the assaulting Edmontons, the Patricias had been caught in the heavy barrage which supported the German counter-attack; their casualties included three of their company commanders. They dug in for the night behind the Edmontons, to the right of the road leading to “Cider”. The Seaforth Highlanders, having occupied with the help of the Calgaries’ “A” Squadron the high ground west of San Leonardo during the day, took up positions level with Jefferson’s left flank.9 During the move forward Lt-Col. Forin was wounded by shellfire, and Major S.W. Thomson took over the battalion.10

The Canadian Division was now entering upon the third stage of the battle which had opened with the successive struggles for Villa Rogatti and San Leonardo. The tactical significance of the obstacle blocking the path to Ortona became increasingly apparent. Near the sea the Gully widened considerably, so that an approach by the coast road would be under direct observation from the high promontory on which Ortona stood. Two alternatives were left to the advancing troops – either they must force a passage along the central route, or circumvent the whole feature by a drive westward to the lateral road, followed by an assault on the crossroads from the south-west. The GOC decided to take the former course, and on the evening of 10 December he ordered the 2nd Brigade to persist in its effort against its original objective in the centre, and also test the enemy’s position

on the coast road to determine whether any weakness in the defence existed below Ortona. At the same time he began moving his reserve brigade forward to the Moro River.11

The 11th brought hard fighting to all three of Hoffmeister’s battalions, but gains were small. Pre-dawn patrols discovered the enemy digging in along the length of the Gully and his armour patrolling the lateral road beyond. All attempts by the Edmontons to advance failed in the face of heavy machine-gun and mortar fire.12 In the afternoon the Patricias, with a squadron of the Calgaries in support, struck out towards the coast road. By nightfall they had battled through a tangle of olive groves and vineyards infested with anti-tank mines and booby-traps to reach the edge of the Gully. After successfully beating off a counter-attack by some 40 Grenadiers, they settled down on the right of the Edmontons to a busy night; for “Vino Ridge” – as the position became familiarly known – was within easy grenade-throwing distance of the German slit-trenches in the Gully.13 On the left flank one company of the Seaforth battered its way through the mud of deeply ploughed olive groves in an attempt to secure the ridge on the near side of the Gully, half a mile south of where the road crossed. The boggy ground, saturated by the previous night’s heavy rain, hampered the movement of supporting Ontario tanks. About 45 infantrymen struggled up the muddy slopes to the objective, but the threat of a counter-attack forced them to withdraw to their starting point.14

While the 2nd Brigade thus closed up to the enemy’s positions, a battalion of the 1st Brigade had drawn level on either flank. During the day the Hastings and Prince Edwards, supported by The Ontario Regiment, had pushed forward along the coast road to a point on the Patricias’ right within 2500 yards of Ortona.15 On the inland flank the 48th Highlanders were holding the hamlet of La Torre, which they had occupied without opposition on the previous night.16

The Fight for the Gully

At noon on 11 December, when it was clear that progress was falling short of intention and that even if the 2nd Brigade should capture the crossroads it would be too exhausted to exploit, Vokes decided to commit his reserves. The West Novas, less one company, were detailed to push through the Seaforths’ positions, cross the Gully and capture the lateral road in the vicinity of Casa Berardi, a prominent square, whitewashed farmhouse, three quarters of a mile south-west of “Cider”. They were then to cut the road which from the crossroads wound westward to Villa Grande and Tollo.17 The remaining company, together with “B” Squadron of The Ontario Regiment,

was held in readiness to move west from San Leonardo along a narrow trail (named by us “Lager”* track)

* This code name, which was suggested by a familiar beverage, has appeared erroneously in some accounts as “laager” – the designation given to a park for armoured vehicles.

which skirted the head of the Gully and joined the Ortona road a mile and a half south-west of “Cider”; this was considered a less precarious approach for tanks than the direct route from San Leonardo.18 What the Seaforth had failed to accomplish during the day, the West Novas were to attempt at night.

At 6:00 p.m. the three companies left San Leonardo for their start line, which was 500 yards north of the town. The attack failed completely. Little artillery support was possible, for fear of endangering the attackers, and what was given did not greatly disturb the enemy, well dug in below the near edge of the Gully. The confusion increased when the battalion lost its wireless sets and the artillery FOO was killed. Early morning found the enemy – members of the 1st Battalion of the 200th Grenadier Regiment – still secure on their reverse slope.19 At eight o’clock Brigadier Gibson ordered the West Novas to renew the attack towards Berardi, and the fight continued in driving rain. Again wireless communication was destroyed as rapidly as it could be repaired or replaced.20 Four times the Grenadiers launched counter-attacks, but the Canadian battalion held its ground. In repulsing one of these thrusts forward elements of the West Novas, eager to close with the enemy, left their slit-trenches and were drawn forward to the crest, where intense machine-gun fire from across the Gully added to an already long casualty list. During the morning the CO, Lt-Col. M. P. Bogert, was wounded, but he continued to direct the fight until relieved in the afternoon. The deadlock could not be broken. The West Novas, having lost more than 60 killed and wounded, dug in and awaited another plan.21 Elsewhere along the divisional front efforts to advance had been equally fruitless. Between the central and coast roads the Patricias had broken up two minor counter-attacks, but had not been able to make contact with the Hastings’ elongated bridgehead.22

At an afternoon conference on the 12th Vokes ordered the 3rd Brigade to make another frontal attack on the crossroads, using one battalion. The task fell to the Carleton and Yorks. A thick creeping barrage, augmented by the mortars of the 2nd and 3rd Brigades, would be preceded by a heavy artillery concentration along the length of the Gully; Calgary tanks were to give what armoured support was possible in the deteriorating weather.23 The PPCLI on the right and the West Novas on the left would make a coordinated effort on either flank of the main thrust, moving forward under the same barrage. One company of the Royal 22e Regiment was detailed to follow the Carleton and Yorks in a mopping-up role. Zero was 6:00 a.m. on the 13th.24

The attack proved as abortive as the previous attempts of the Edmontons and the West Novas. The leading Carleton and Yorks, pressing forward

immediately after the artillery concentration, managed to clean out three machine-gun nests on their side of the Gully and take 21 prisoners, but they were met with murderous machine-gun and mortar fire as they showed themselves above the crest. Those who were not cut down were forced back to their own side of the ridge. Within an hour the attack was spent; the artillery barrage had far outdistanced the infantry, allowing the German defenders to fight back vigorously with machine-guns and small arms. A threat by two Mark IV tanks on the left flank of the Carleton and Yorks resulted in a troop of the Calgaries’ “C” Squadron being committed – at the cost of one of its Shermans.25 Casualties mounted; by the end of the day Lt-Col. Pangman had lost 81 officers and men – including 28 taken prisoner when a company headquarters and one of its platoons were surrounded.26 Low cloud had prevented fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force from giving their usual effective support. Pilots were compelled to bomb alternative targets farther north or return to base with their full load.27

The attacks on the flanks were scarcely more fruitful than the Carleton and York effort: neither the Patricias nor the weakened companies of the West Novas gained the edge of the Gully. The latter unit’s fighting strength had been reduced to about 150 men, and these numbers were still further depleted in a heroic but futile late afternoon sally against a German outlying position near Casa Berardi.28 On the coast road the Hastings pushed two companies forward a few yards under heavy fire.29

The gloomy picture of the day’s events was momentarily brightened by a temporary success, upon which we unfortunately failed to capitalize. It will be recalled that for the past two days Gibson had been holding at San Leonardo an infantry-tank combat team, made up of “B” Company of the West Novas and “B” Squadron of The Ontario Regiment, augmented by some engineers and the self-propelled guns of the 98th Army Field Regiment RA. An infantry patrol from this force reconnoitring “Lager” track on the night of 12–13 December discovered a number of German tanks near the shallow head of the Gully, apparently guarding the approach to the main Ortona road.30 At seven next morning, while the Carleton and Yorks were making their abortive attack opposite Berardi, three of the Ontario Shermans, carrying a West Nova platoon, drove into the enemy laager. The startled Germans had time to get away only one shot; armour-piercing shells fired at a range of less than 50 yards knocked out two of their tanks, while eager infantrymen closed in and captured the remaining two. The destruction of an anti-tank gun completed a satisfactory job.31

If this prompt action, which was initiated and controlled by the West Nova platoon commander, Lieutenant J. H. Jones – and which won him the MC – did not itself open the door to the main lateral road, it at least unbarred it. By 10:30 a.m. the remainder of “B” Company and its supporting

squadron arrived with orders to turn north-east and drive towards Casa Berardi. The combat team advanced between the lateral road and the Gully, but less than 1000 yards from the “Cider” crossroads a ravine, lying at right angles to the main Gully, stopped the tanks. Efforts of the infantry to cross by themselves were unsuccessful; for the enemy, already concerned with the attack on his front by the main body of the West Novas, reacted quickly and vigorously to this new threat to his flank.32

Meanwhile, another small Canadian infantry-tank team, organized by Brigadier Wyman with the authority of the GOC, had made a spectacular thrust on the left which “almost loosened the whole front.”33 The action caught the enemy unaware, and, promptly exploited, might quickly have ended the struggle for the crossroads. Earlier on 13 December “A” Company of the Seaforth, numbering but 40 men, had set out along “Lager” track with the four effective tanks remaining to the Ontarios’ “C” Squadron. It was the strongest force that could be mustered for the purpose, for, as we have seen, the whole Division was committed, and there was no reserve. Describing a wider arc around the head of the Gully than that taken earlier by the West Nova Scotia combat team, the tanks crossed on a culvert which the enemy had neglected to demolish and led the attack up the lateral road along the rear of the German positions. The surprised enemy, not realizing the numerical weakness of their assailants, ran out of houses and strongpoints to surrender. By nightfall the enterprising little group had advanced almost to Casa Berardi; it had taken 78 prisoners (including a German battalion headquarters) and knocked out two German tanks.34 But unfortunately this brilliant achievement, which was to point the way to the eventual capture of Casa Berardi, could not immediately be followed up. Towards dusk the Ontario squadron commander, Acting Major H. A. Smith, who had been in constant touch by radio with Brigadier Wyman, reported that his ammunition was expended and that he was very low on petrol. With no reserve immediately available for reinforcement Wyman instructed the force to withdraw and to hold the entrance to the main road secure throughout the night. The vulnerability which the enemy had betrayed on this flank changed the Canadian plan of battle, and Vokes now ordered an attack to be made the following morning by the Royal 22e, the only battalion of the Division yet uncommitted west of the Moro.35 During the night, however, the Germans restored their right flank positions, as troops of the 1st Parachute Division replaced the battered Grenadier units defending the Gully.

From the time of its committal in the coastal sector to restore the chaotic situation produced by the debacle of the 65th Infantry Division the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division had fought with spirit, but had paid dearly for its stand. German situation maps of 13 December showing dispositions along the Gully bore the significant designations: “Remnants 1 Bn 200 Gren Regt”;

“Remnants 361 Gren Regt”.36 The reckless and extravagant manner in which the Grenadiers had been engaged, particularly during their counterattacks, had drained the division’s manpower beyond immediate reinforcement. The fighting on the 13th had cost 200 prisoners (many of these to an attack by the 8th Indian Division west of Villa Rogatti).37 bringing the total during the two weeks’ contact up to nearly 500.38 But the number of prisoners did not tell the whole story of the 90th Division’s losses. One counter-attack against the West Novas was typical of many instances indicating the length to which the enemy was prepared to go to maintain his position. It was made by some 50 Grenadiers advancing in extended line; almost all were annihilated by the West Novas, who held their fire until the last minute.39 The war diary of the 76th Corps recorded regretfully on the 13th: “A great fighting value can no longer be ascribed to the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division. The units have become badly mixed and the troops are exhausted. The fighting value of at least two battalions has been used up. The present positions can only be held by bringing in new battalions. ...”40

The 3rd Parachute Regiment, transferred from the relatively quiet sector of the upper Sangro, had already supplied these new battalions.41 The 2nd Battalion of this regiment was committed opposite the Canadian centre in time to repulse the Carleton and York attack on the 13th.42 That night it was joined by the 3rd Battalion in the Berardi area, while to its left the hapless “remnants” of the 200th Regiment’s 1st Battalion held the coastal salient.43 Temporarily the commander of the 3rd Parachute Regiment was in charge of all operations in the coastal sector, for Herr, who felt that operations of the 90th Panzer Division could have been more skilfully directed, had removed Lt-Gen. Karl Hans Lungershausen, and was replacing him by the very capable Colonel Baade.44

Casa Berardi, 13–15 December

Late in the afternoon of the 13th General Vokes announced the plan by which he hoped to turn the enemy’s flank. The Royal 22e Regiment, supported by “C” Squadron of the Ontarios, would strike out at 7:00 next morning from “Lager” track and attack north-eastward along the Ortona road towards “Cider”. Corps and divisional artillery would fire a barrage 1500 yards wide, which would move up the road with its right flank covering the Gully. Coincident with the attack the PPCLI would once more attempt to cross the Gully and cut the lateral road, while the Hastings maintained pressure along the coast.45

Throughout the night recovery teams of The Ontario Regiment worked to free “C” Squadron’s tanks from the deep mud of “Lager” track. They

retrieved seven, and with these Major Smith moved off at 3:00 a.m. to join the infantry at the start line, in the area where “Lager” crossed the shallow head of the Gully.46

Forty minutes before the Royal 22e Regiment was scheduled to begin its advance (at the request of the 3rd Brigade zero hour had been postponed to 7:30),47 the enemy counter-attacked at the junction of “Lager” with the Ortona road. This threat to the success of the 3rd Brigade’s venture was capably handled by a company of the 48th Highlanders, which had been sent to the Division’s left flank on the previous afternoon to provide additional support to the combat team, and had spent the night in defensive positions astride the track. Wisely holding their fire until the last minute the Highlanders killed nine enemy and captured 31 before the remainder hurriedly withdrew.48

It was Lt-Col. Bernatchez’s intention to advance along the main road with two companies. This imposed upon “C” Company on the left the necessity of securing a bridgehead across, this road before both made a right turn towards the final objective. Shortly after 7:00 a.m. on the 14th, as “C” Company approached the start line it came under fire from a German tank which had been hidden behind a house near the road junction. The situation looked serious, for at the time the supporting Shermans were lumbering over the muddy track some distance behind the infantry.49 Skilful manoeuvre and determined action by one of the platoons saved the day. While the rest of the company, applying the battle-drill tactics so diligently rehearsed on training fields in southern England, worked forward by sections to divert the attention of the German tank crew and of enemy infantry across the highway, the platoon commander led his PIAT group through the partial cover of an olive grove into a position from which the tank could be engaged. During the approach the officer was wounded, and the PIAT’s mechanism damaged, but the platoon sergeant, Sergeant J. P. Rousseau, taking his commander’s place, secured another weapon from a following platoon. With this he dashed across the open ground to within 35 yards of his target, and fired. The bomb struck between turret and engine casing and must have detonated the ammunition; later 35 pieces of the Mark IV Special were counted scattered over the ground.50 By his courage and initiative this plucky NCO won the Military Medal.51

To the crouching men of “C” Company the explosion was a success signal which heralded the capture of the road junction; but the bomb which blew that tank to pieces exploded too the long controversy on the effectiveness of the PIAT, which after numerous failures had lost the confidence of many of the troops. Now, as a training memorandum issued by the 1st Canadian Division pointed out, “this quick, resolute and well thought out action demonstrated clearly that enemy tanks can be dealt with effectively by infantry men who have confidence in their weapons and the ability to use them.52

By this time it was 10:30, and the company commander, Captain Paul Triquet, signalled up the Ontario’s Shermans, which had been waiting in the shallow Gully. They arrived in time to destroy a second German tank which had made its appearance at the track junction.53 The infantry surged forward, and for the second time Canadians had a footing on the lateral road. Without further delay Triquet pushed forward along the highway, with the tanks moving on his right, immediately to the rear of the Gully. At first resistance was light, but half way to Casa Berardi the attackers encountered savage opposition. “C” Company and the Ontarios were now alone; “D” Company on the right had become lost in the confusing terrain, and straggled into the West Novas’ area later during the afternoon.54

It was evident that the enemy had appreciated the danger to his flank and had taken full measures to meet it. After a week’s air and artillery bombardment, the approach to the crossroads was a wasteland of trees with split limbs, burnt out vehicles, dead animals and cracked shells of houses. Now every skeleton tree and building was defended by machine-gunners backed by tanks and self-propelled guns, and paratroop snipers lurked in every fold of the ground. Against this formidable resistance our armour and infantry cooperated well. The Shermans blasted the stronger positions, while the Royal 22e cleaned out what remained. Two more German tanks were knocked out and a third put to flight. A heavy barrage caught the infantry company and reduced its strength to only 50; Triquet was the sole surviving officer. He reorganized the remnants of his force into two platoons under the two remaining sergeants, and spurred them forward. “There are enemy in front of us, behind us and on our flanks,” he warned.*

* This is corroborated by the Tenth Army war diary, which describes the German counter-measures as “a concentric attack on the enemy who had broken through”.55

“There is only one safe place – that is on the objective.”56

The attack continued. Ammunition was short; there was none following, and no one who could be sent for it. The wounded were treated hurriedly, and left where they had fallen. A Mark IV approaching along the road was first blinded by smoke laid down by one of Smith’s Shermans, and then destroyed by tank fire through the smoke.57 In the late afternoon Casa Berardi was taken, and the indomitable few fought on almost to the cross-roads. Finally the enemy’s mortar fire stopped them, and the survivors, less than fifteen, drew back to the big house. A count revealed five Bren guns and five Thompson sub-machine guns on hand, and a woefully small supply of ammunition. “C” Squadron had four tanks left. With these slender resources Triquet organized his defences against counter-attack, and issued the order, “Ils ne passeront pas!”58

When news of the success reached Brigade Headquarters, Brigadier Gibson impressed upon Bernatchez the importance of holding and reinforcing the

position which had been so gallantly won on the west side of the Gully.59 At nightfall “B” Company of the Royal 22e joined the small group of tanks and infantry clustered about Casa Berardi. The failing light made any renewed attack with armoured support impossible, and the force took up an alert defence for the night. In the dark two Mark IV tanks, the last enemy traffic on that part of the lateral road, slipped by towards Ortona. The German flank was sealed.60 Under cover of night Bernatchez led his two remaining companies across the empty Gully in front of the West Nova Scotia area, reaching the Casa at 3:00 a.m.61

Elsewhere on the Canadian front units of all three brigades had maintained pressure on the 14th, but without making any substantial gains. Near the central axis the Carleton and Yorks beat off a strong counter-attack in the late afternoon;62 on the right flank attempts by the Patricias and the Hastings and Prince Edwards to advance were thwarted by the heavy enemy fire.63 These fruitless efforts convinced the Canadian GOC that the key to success lay in an exploitation of the favourable situation around Casa Berardi.64

The probability of such a move was already unpleasantly realized at 76th Panzer Corps Headquarters, whose war diary recorded on the 14th, “Enemy will bring up further forces and tanks and, in the exploitation of today’s success, will presumably take Ortona.”65 German accounts did not conceal the extreme concern at the break-through south-west of Berardi. Characterizing 14 December as “a day of major action”, Tenth Army Headquarters admitted that Canadian exploitation had been stopped only “by sacrificing the last resources”.66 The prolonged telephone conversations of the day showed that the Germans were exhausting every possible source of quick reserves. “The situation is very tense ...” Wentzell told the 76th Corps Chief of Staff. “Either the Corps receives something tangible [in reinforcements] or it will have to adopt another method of fighting.”67 A hint as to what this might be was provided by the commander of the 3rd Parachute Regiment. “Heilmann thinks that even now one ought to change tactics and withdraw to the mountains”, Herr suggested to the Army Commander, General Lemelsen. “If reserves arrive tomorrow it will be possible to hold, otherwise only a delaying action is possible.”68

With neither Corps nor Army able to provide replacements, Kesselring ordered his Army Group Reserve – Regiment Liebach*

* Consisting of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Parachute Regiment, an air-landing training battalion and an artillery battery.69

– to be committed in the Ortona sector.70 He gave instructions that everything had “to be thrown in” and that the 76th Corps was to be “held responsible for the sealing off of the enemy penetration.” “It was a serious decision to make Liebach available”, commented Lemelsen to Herr.71

This conclusive German testimony to the significance of the blow delivered along the Ortona road on 14 December by the hard-fighting force under Captain Triquet strikingly endorses the recognition which this gallant officer received for his achievement. He was awarded the Victoria Cross – the first of three won by Canadians in the Italian campaign. Major Smith, under whose intrepid leadership the Ontario tanks had so effectively supported the successive thrusts of the Seaforth and the Royal 22e along the lateral road, received the Military Cross.72

General Vokes did not immediately undertake the major thrust up the Ortona road which the enemy was expecting. “My appreciation of the situation at this time”, he writes, “led me to believe that a strong build-up of tanks in the Casa Berardi area, which must be held at all costs, would so shake the enemy, who had been badly mauled, that pressure from this flank and on his front would cause an early collapse.73 Late on the 14th the GOC therefore ordered a further squadron of tanks to be moved up to Berardi during the night, and another frontal assault to be made in the morning by The Carleton and York Regiment, with the support of heavy artillery concentrations. If this attempt to cross the Gully failed, he planned alternatively to have the 1st Brigade envelop the crossroads by a deep movement on the left flank. At the moment, however, the RCR and 48th Highlanders – the only infantry battalions not in contact with the enemy – were well placed to exploit through the crossroads position, should the 3rd Brigade’s effort succeed.74

The Carleton and York attack began at 7:30 a.m. on the 15th, and lasted less than an hour. Artillery fire had failed to neutralize enemy positions, which remained secure against frontal assault. After an advance of only 200 yards the battalion was ordered to consolidate; three officers and nine other ranks had been killed, one officer and 27 other ranks wounded.75 This ended all attempts to force the Gully from the east. From now on the main Canadian endeavour shifted to the Berardi area and the axis of the Orsogna–Ortona road.

For the Royal 22e in their newly won positions west of the Gully, 15 December was a difficult day. Their CO’s plans to press forward along the lateral road in conjunction with the Carleton and York attack went awry. Immediately before zero hour “B” Company was caught in its own supporting artillery fire and suffered heavy casualties. With communications broken, nothing could be done to correct the offending batteries. The enemy was quick to profit from the mishap, and manoeuvred his tanks into positions from which their guns could cover the ground held by the Canadians. Deadly machine-gun and artillery fire kept the remaining companies at their start line.76 Early in the afternoon enemy shelling slackened as a force of 200 paratroopers with tank support launched a determined counter-attack. The

weakened battalion contracted to withstand the shock and to allow a margin of safety for our artillery fire. Speedy and efficient action by the self-propelled 105-millimetre guns of the 98th Army Field Regiment RA, which in fifteen minutes hit the enemy with 1400 rounds, crippled the German thrust, and sent the discomfited paratroopers reeling back with heavy losses.77

As night descended, the infantry companies drew into tight defensive positions with the armour. Orders came from Brigade Headquarters to hold at any price for 48 hours – the time which Vokes considered would be needed to prepare for the 1st Brigade attack.78 By daylight on the 16th the force at Berardi had received welcome reinforcements and much-needed ammunition for the tanks. About 100 “left out of battle” personnel from the Royal 22e Regiment’s Support and Headquarters Companies came forward with a well-laden pack train* of mules.79

* The Commander RCASC, 1st Canadian Division had available some 370 mules, which were kept in a “harbour” under the care of an Indian Mule Company and sent forward as they were required by the front line troops.

Seven Ontario tanks filled with 75-millimetre ammunition (to provide more space each co-driver was left behind) set out along “Lager” track at midnight and groped their way safely through the darkness to solve the most vital problem confronting the hard-pressed “C” Squadron.80

Thus fortified, the Royal 22e continued during the 16th and 17th to dominate the area about Casa Berardi and thereby frustrate any attempt by the enemy to restore his flank. Intense artillery activity on both sides persisted all along the front, and each Canadian battalion along the edge of the Gully suffered an average of a score of casualties daily. A small probing attack by the West Novas on the 17th immediately to the left of the main bridge over the Gully confirmed patrol reports that the enemy was thinning out south of the “Cider” crossroads.81 This news was received without undue optimism: intelligence staffs correctly appreciated that defence of the sector was being placed in the safer hands of Heidrich’s parachutists.82

The Capture of “Cider” Crossroads, 18–19 December

It is fitting that the attack launched by the 1st Brigade on 18 December should be remembered by the code name of the barrage which supported its opening phase – “Morning Glory”. Not only was it the heaviest fire yet employed by the 1st Division, but in its initial stages “Morning Glory” set a standard of almost faultless cooperation between artillery, infantry and armour, not previously attained by Canadians in the Italian campaign.83 The complex details of the plan for the set-piece assault were painstakingly worked out by the headquarters staffs of the 1st Canadian Division, the 1st

Infantry Brigade and the 1st Armoured Brigade. Final responsibility for carrying out the operation rested with Lt-Col. Spry, of the RCR, who took over the 1st Brigade on 16 December when illness forced Brigadier Graham to relinquish command.84

“Morning Glory” was designed to drive a deep salient into the German defence line south-west of Ortona, from which an attack might be mounted against the town itself. The three phases in which the operation was planned would successively bring into action all the battalions in the 1st Brigade. From a forming-up area on “Lager” track at the head of the Gully the 48th Highlanders were to attack due north behind a creeping barrage to cut the Villa Grande road at a point about 2000 yards from “Cider”. With this achieved, after a minimum pause of one hour the second phase would begin with a new barrage (“Orange Blossom”*)

* In selecting code names for these fire plans Headquarters RCA 1st Canadian Division was allotted for the week names of flowers having the initial letter “M” to “O”. The choice of “Morning Glory” came from a flower on the CRA’s family crest; “Orange Blossom” was picked not so much for the flower as for the cocktail of that name, which someone suggested “carried a tremendous wallop”.85

running at an angle to the original one. Behind this the RCR (commanded now by Major W. W. Mathers), forming up in the wake of the 48th Highlanders, would attack north-eastward along the railway track, which closely paralleled the Ortona lateral; on reaching the Villa Grande road it would assault, the isolated enemy garrison at the “Cider” crossroads. In the final phase the 2nd Brigade would exploit to capture Ortona, while the Hastings and Prince Edwards, brought over from the coastal sector, would extend the salient northward towards San Tommaso and San Nicola, villages each about two miles inland from Ortona. Phases I and II were to be supported by all the artillery of the 5th Corps, consisting of three medium and nine field regiments and a heavy anti-aircraft battery.†

† The 4th, 58th and 70th Medium Regiments RA, the 1st Field Regiment RCHA and the 2nd and 3rd Field Regiments RCA, the 3rd, 52nd and 53rd Field Regiments RA, the 57th, 98th (SP) and 166th (Newfoundland) Army Field Regiments RA, and the 51st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery RA.86

The “Morning Glory” barrage, 1000 yards wide, would advance to a depth of 2200 yards, moving forward 100 yards every five minutes. At the same time, the whole area over which the infantry was advancing would be curtained by protective walls of intermittent bursts designed to stop any counter-attack from the flanks. “Orange Blossom” followed a similar pattern; in effect, each battalion attack was to be supported by 250 guns.87 It may be noted that the array of artillery strength assembled for “Morning Glory” included the 166th (Newfoundland) Field Regiment RA, which had joined the Eighth Army in Italy at the end of October, having served with the First Army during the final stages of the Tunisian campaign. It had supported the 78th Division north of the Trigno, and the 8th Indian Division at the Sangro crossing,88 and its forthcoming employment with the Canadians was to add force to the claim, later made by one of the battery commanders, that the

Newfoundlanders had “fired their 25-pounders in support of most infantry formations in the [Eighth] Army.89

If for nothing else the 48-hour pause was necessary to replenish ammunition stocks for these mighty barrages. This task called for unremitting toil by RCASC units, which for three days hauled daily from the beaches north of the Sangro 16,000 rounds for the 25-pounders alone – making round trips*

* The exacting role of controlling this and other extensive supply traffic for the Canadian Division was capably carried out by No. 1 Provost Company, recruited in 1939 from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Detachments were under continual fire on exposed roads and bridges, and a number of men were later killed by enemy shelling while on point duty in Ortona.90

of close to 35 miles.91 The tired gunners themselves welcomed the brief respite. From the commencement of the first attack across the Moro eleven days earlier their guns had seldom been silent, and there had been periods of intensive action when, to quote the 3rd Field Regiment’s historian, “they fired until the paint curled from the red-hot steel and the men reeled in the pits from exhaustion and were sick from the blast.”92

Some mention must be made of the peculiar difficulties confronting the artillery at this time. Up to the crossing of the Moro the gunners when developing their fire plans had usually been able to carry out preliminary shooting in order to register by observed fall of shot the salient points of the barrage. In the battle in which the Canadians were now engaged, however, the number and variety of the demands for artillery support meant that sometimes two or three fire plans were under preparation at once, and the guns frequently had to switch from one side of the divisional front to the other in a matter of minutes. In these circumstances adequate artillery registration was not possible, and fire plans had to be developed from the map. The risk accompanying this method was recognized, and all infantry commanders were warned down to the platoon level. It soon became evident, moreover, that the only large-scale maps available – Italian sheets with the British grid superimposed – were far from accurate (see below, p. 371), and in some cases had an error of as much as 500 metres. Every effort was therefore made to do the maximum observed registration, but often the pressure of the battle forced a resort to map shooting. Nor did the weather help the gunners. Rapidly changing conditions which produced an overnight variation of several degrees in the temperature of the gun charges and sudden high winds which blew off the Adriatic with unpredictable velocity further complicated the problem of providing effective artillery support.93

The care and precision with which the artillery programme for “Morning Glory” was planned was matched in the design for the armoured support. This role fell to the Three Rivers Regiment, which had been uncommitted since its arrival on 15 December from Vinchiaturo, where it had rested during November after supporting the 5th British Division in the advance to Isernia.94

The regiment’s return to the command of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade released the 44th Royal Tank Regiment, which since the Moro crossings had been employed mainly in support of the 8th Indian Division.95 “B” Squadron was assigned to the 48th Highlanders and “A” Squadron to the RCR “C” was held in reserve. It was arranged that each squadron commander should move with the battalion commander, and that a troop of tanks would work with each rifle company. To ensure proper intercommunication an infantry officer rode in the squadron commander’s tank with a wireless set tuned to the battalion frequency. More meticulous attention was paid to ensuring close infantry-tank cooperation than in any previous Canadian operation in Italy. Officers of the squadron and of the battalion met to discuss the coming action together, so that (as a divisional account records) “when they went into battle it was not merely three tanks supporting a company, but is was ‘Bill Stevenson’s’ troop working with ‘Pete Smith’s’ company – and it made a lot of difference.”96

Promptly at eight o’clock on the morning of the 18th, the thunder of massed artillery announced the opening of “Morning Glory”. The first phase of the operation proceeded with the precision of a well-rehearsed exercise. Behind a wall of bursting high explosive 300 yards thick “A” and “D” Companies of the 48th Highlanders. advanced resolutely through the broken orchards and tattered vineyards that encumbered their path. (The battalion was using the “Y” formation, in which the two leading companies were directed to follow the barrage on to the objective without becoming involved in any fighting en route, while the company immediately behind them mopped up any, enemy who might appear after the barrage had passed – the fourth company being held in reserve to exploit the success of either of the leading companies.)97 Dust and smoke reduced visibility to about 200 yards, and some platoons maintained their direction only by using the compass. Enemy reaction was at first limited to some small-arms fire, but soon mortar and artillery shells began to fall behind the barrage – a German manoeuvre calculated to destroy our troops’ faith in the efficiency of their own gunners. The Three Rivers tanks found a target in every building and haystack, and when soft ground forced them to select routes which separated them from their infantry, the arrangements made in advance to ensure good intercommunication proved their worth. German self-propelled guns opened fire from the flanks, but the presence at Berardi of the Royal 22e Regiment (which had come temporarily under Spry’s command) reduced the effect of interference from the right, while the tanks successfully dealt with the opposition on the left.98 At 10:30 the forward companies reported that they were on the objective, and the remainder of the battalion moved up rapidly to consolidate. The first phase was over. Casualties for the 48th Highlanders numbered only four killed and twenty wounded; half of these losses were

caused either by shells of the supporting barrage falling short, or by enemy fire designed, as we have noted, to create just such a false impression.99

When the success signal came back, Spry ordered “Orange Blossom” to begin, and at 11:45 a.m. the guns of the 5th Corps again opened fire.100 In their forming-up places near the junction of “Lager” with the lateral road The Royal Canadian Regiment prepared to advance astride the railway track on a two-company front. But whereas success and economy had marked the Highlanders’ attack, that of the RCR within a few minutes met with misfortune and heavy casualties. As the barrage began to creep, “C”, and “D” Companies, closely supported by their tanks, moved across the start line and reported over the wireless that everything was going well. While our shells were still bursting on the opening line, however, the Carleton and Yorks on the right flank sent an urgent message that rounds were falling in their forward positions, despite the fact that the battalion had previously been withdrawn 300 yards from the edge of the Gully. At the same time the 48th Highlanders reported that their mopping-up companies were coming under our fire. (The artillery had not been able to carry out registration by observed fire for “Orange Blossom”; and dependence on faulty maps was the probable cause of the barrage’s failure to “fit the ground”, which was very uneven and divided by embankments and deep gullies.)101 These complaints could not be set aside, and the CRA, Brigadier Matthews, who was with Spry at the time, ordered the barrage to lift 400 yards and at the same time cancelled the right-hand wall of protective fire.102

The effects were immediate and disastrous. The advancing RCR suddenly found themselves face to face with a strong group of paratroopers whom the lifting of the barrage had left unscathed. From these and from the east side of the Gully, where the modification of the artillery plan had also given the enemy unexpected freedom of action, a murderous cross-fire laced the Canadians. Men dropped like flies. The two leading companies were smashed to pieces, all officers becoming casualties. “Never before”, wrote a surviving officer, “during either the Sicilian or Italian campaign had the Regiment run into such a death trap.”103 After an hour of bitter and confused fighting, Major Mathers, himself wounded, decided that since the barrage had been lost it would be futile to commit his reserves, and ordered a consolidation. Two artillery officers who had gone forward with the infantry brought back the remnants of the assault companies – a dozen or fifteen men each. These carried on the fight from some buildings 100 yards ahead of the start line.104

Throughout the ensuing night The Royal Canadian Regiment, its strength reduced to 19 officers and 159 other ranks, held its position under mortar fire and sniping, and prepared to return to the attack. Fully aware of the predicament of his own battalion, Spry had ordered that for the sake of morale as well as from tactical considerations the RCR must make another

effort to take its objective. Every man that could be spared from the Support and Headquarters Companies came forward, and with these and the remnants of the rifle companies, three companies were organized of 65 men each.105

The attack started at 2:15 p.m. on 19 December, after a shortage of petrol and ammunition for the tanks had caused a delay of four hours. This time all went well. Communications were excellent, and “A” and “B” Companies with their accompanying tanks advanced unwaveringly behind an intense barrage. The relatively light enemy resistance in contrast to the deadly opposition of the previous day indicated that Heidrich*

* HQ 1st Parachute Division assumed command of the coastal sector on 19 December.106

had accepted the loss of the Gully. Shortly before nightfall “Cider” crossroads, which had remained the objective of the 1st Division during two weeks of bitter fighting, was captured with surprising ease. In the final advance to their goal the RCR had suffered only three casualties. With “Cider” in Canadian hands, the Carleton and Yorks crossed the Gully and spent an unpleasant night mopping up enemy pockets among the bodies and booby traps which littered the area of the fateful road junction.107

The operation just completed, like every other in the campaign, had seen the unit chaplains making their fine contribution to the comfort of the wounded and the welfare of the troops generally. They administered first aid, evacuated casualties in their jeep-ambulances, and buried the dead. Their roadside Regimental Aid Posts were friendly stopping places for individuals and small parties moving up or down at night. Here they combined medical aid with cheering little deeds of hospitality, dispensing “tea, insect powder, apples, bandages, sulphanilamide, biscuits, advice and news”. From the pen of a padre of the 1st Armoured Brigade (H/Major Waldo E. L. Smith, who himself won the MC at Colle d’Anchise for bravery in caring for the wounded under direct enemy observation) comes this tribute to the chaplains of the 1st Canadian Division:–

You heard about them in the Ambulance wards, in conversations at our roadside RAP, in the contacts you had in the fields and streets that were the scene of this fighting. They tended the wounded and helped carry them out. They went to the boys in their company positions. They shared all their dangers and all their hardships. “It is service under fire that counts.”108

In winning the bloody 2500 yards from San Leonardo to the Ortona road each brigade of the Canadian Division had successively played its costly part. Now it was once more Brigadier Hoffmeister’s turn to take up the struggle. During the morning of 19 December, the Seaforth Highlanders relieved the Hastings on the coast road. The PPCLI had remained on “Vino Ridge”, about a mile inland, while The Edmontons were in immediate reserve north of San Leonardo.109 The 2nd Brigade was thus in good position to exploit the capture of the crossroads and advance on Ortona.

The Approach to Ortona, 20 December

The second week in December had seen another regrouping of the Eighth Army. The arrival of winter had ended any possibility of conducting offensive operations in the mountainous sector of the 13th Corps; the enemy recognized this fact when he relieved the formidable 1st Parachute Division in that region of snow-covered peaks by a mere handful of mountain troops.*

* The 3rd and 4th Alpine Infantry Battalions (Hochgebirgsbataillon). These non-divisional units were composed almost wholly of highly skilled mountaineers.110

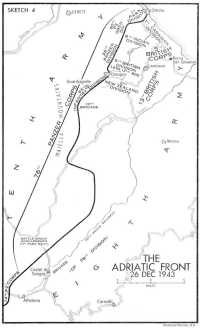

To provide a greater concentration of forces in the coastal sector, General Montgomery accordingly ordered the 13th Corps to move east, replacing it in the mountains with the battle-weary 78th Division. On 16 December the 5th Division entered the line on the right of the 2nd New Zealand Division, which now came under command of General Dempsey’s headquarters. This redeployment of his strength gave the Army Commander four divisions abreast on the twelve-mile front from Ortona to Orsogna111 (see Sketch 4).

While the 1st Canadian Division had been fighting to secure a firm hold on the Ortona–Orsogna road, each of the three divisions farther inland had also managed to cut the important lateral. On the Canadians’ immediate left the 8th Indian Division, thrusting slowly westward from the Villa Rogatti bridgehead which it had inherited from the Patricias, captured Villa Caldari on 14 December and Villa Jubatti three days later, and by the 18th had put patrols into Crecchio, one mile beyond the highway.112 In the 13th Corps’ sector infantry of the 5th Division entered Poggiofiorito, midway between Ortona and Orsogna, on the 17th, and supporting tanks crossed the road to shoot up the village of Arielli.113 Below the Maiella massif, on Dempsey’s left flank, the New Zealand Division had been engaged since 2 December in continuous heavy fighting against the 26th Panzer Division, whose stubborn and reckless defence of Orsogna had won praise from the Fuhrer himself.114 Three bitterly contested assaults on Orsogna failed, but by the morning of 17 December the New Zealanders had secured a firm hold on a mile of the Ortona road north-east of the town.115 This achievement, following hard upon the Canadian success in the Berardi sector, forced the enemy to surrender the lateral communication link which he had so long and stubbornly defended. But although he retired a few thousand yards to the mass of ridges, ravines and watercourses to the north-west, he still retained possession of the terminal towns of Orsogna and Ortona.

Experience of German defensive tactics led Montgomery’s staff to expect that the enemy, having been evicted from his delaying position in the Gully, would withdraw to the next natural obstacle. This was the Arielli, a small stream cutting across the line of advance to enter the Adriatic three miles north of Ortona. A 13th Corps operation order issued on 22 December

The Adriatic front, 26 December 1943

stated somewhat optimistically: “Eighth Army is going to reach the line of the river Arielli by 24 December.”116 It was not considered that the Germans would make a serious stand in Ortona; indeed, the Army’s administrative staffs were busy with plans to develop the town into a maintenance area and a rest centre, where troops would find in the high stone buildings which lined the narrow streets adequate protection from the winter weather. To this end the small harbour below the ancient citadel had not been included among the targets of our heavy bombers, and the town itself was spared the almost daily strikes with which light and fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force pounded Orsogna during December.117 As the Canadians prepared to capture Ortona and so free the coastal highway, Montgomery ordered a sustained thrust to be made at the same time along the inland road through Villa Grande and Tollo, with the object of opening a second route to the north. Accordingly a battalion of the 8th Indian Division moved north across country from the lateral road, and in the early hours of 22 December launched a strongly supported attack against Villa Grande.118 By that time Canadian soldiers were battling their way into Ortona in the face of unexpectedly stern resistance.

By 10:00 a.m. on the 20th sappers of the 4th Field Company RCE had repaired the blown bridge on the main axis, and Canadian tanks crossed the Gully to “Cider” crossroads.119 At midday The Loyal Edmonton Regiment, supported by “C” Squadron of the Three Rivers, struck out along the Ortona road, with orders to occupy the buildings at the edge of the town. Moving steadily behind an effective barrage the attackers met little resistance in their 3000-yard advance. Engineers accompanying the infantry swept the tank routes, but despite their efforts the mines and booby-traps with which the ground was sown disabled four of the armoured squadron’s tanks. At 2:26 p.m. the Edmontons were on their objective; fighting in the later stages of the attack had become more severe, and had produced 14 German prisoners.120 By nightfall “C” Company of the Seaforth, attacking up the coast road, had scaled the cliffs south-east of the town and had linked up with the Edmontons, coming temporarily under Lt-Col. Jefferson’s command.121 In the gathering darkness eight anti-tank guns and a platoon of medium machine-guns were brought forward to join the twelve tanks supporting the infantry in the western outskirts of Ortona.122

During the 2nd Brigade’s approach fighters and fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force had swept over German-held territory from Orsogna to the coast, scouring the enemy’s supply roads and attacking his gun and forming-up areas.123 In the past fortnight adverse flying conditions had, reduced air activity over the battle area, but what limited support had been available to the Canadians had benefited by the introduction of a new system of control. In Sicily, as we have noted (above, p. 111), requests by forward

troops for air support had to be channelled through brigade and army headquarters to the air force – a cumbersome process which virtually precluded effective support in a fast-moving battle. Early in the fighting on the Italian mainland No. 2/5 Army Air Support Control had modified two of its armoured tentacles as “Rovers” – visual control posts which could “rove” from one brigade front to another without interfering with normal air support communications and seek out additional targets for air attack. Besides being linked with the Army Air Support Control and one of the forward brigades, the Rover was in direct communication with its affiliated fighter-bomber wing on the ground, and by means of a Very High Frequency wireless set could control similarly equipped fighter-bombers in the air. Thus the time lag between placing a request and its fulfilment was considerably reduced, and ground-air cooperation materially improved.124 During the battle of the Sangro the addition of the “cab rank”*

* First used in support of the Canadian Division on 8 December.

produced the system of airborne fighter-bomber control which became universally adopted in the later stages of the campaign. The cab rank, a flight of six fighter-bombers, would call in to the Rover control post by VHF set at a stated time, and for a maximum period of twenty minutes would circle just behind the battle area awaiting briefing on impromptu targets. If the air controller with Rover had none, the aircraft would proceed against an alternative pre-selected target, and another flight would move into the cab rank.125

The 2nd Brigade’s Struggle in the Streets

At first light on 21 December the Edmontons began to fight their way into Ortona. It was the start of a week of hand-to-hand struggle with the elite of the German Army. From it Canadian troops emerged with an enhanced reputation, and a technique of street fighting which was to be closely studied by training staffs in all the Allied armies.

Ortona was typical of the many communities up and down the Adriatic which had their origin as coastal strongholds in mediaeval days when the maritime power of Venice dominated Mediterranean commerce. Huddled against the massive 15th-century castle which crowned a high promontory thrusting squarely into the sea, the Old Town with its tall, narrow houses and dark, cramped streets, merged into the more modern section which had grown up on the flat tableland to the south. This newer part of the town was laid out in a system of rectangular blocks, although only the main thoroughfares were wide enough to allow the passage of a tank. The buildings were packed wall to wall, and rose generally to a height of four storeys. From the eastern edge of the town an almost precipitous cliff fell away to the small

artificial harbour, which was enclosed by two stone breakwaters protruding far out into the water. A deep ravine west of Ortona restricted the town site to an average width of 500 yards – about one third of its length from north to south. This natural impregnability against attack from three sides meant that the German defenders could concentrate on blocking the only possible approach – the route from the south (Highway No. 16) by which the Canadians were attempting to force an entry. At the outskirts of the town this road became the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, which continued northward to the Piazza Municipale. From this central town square, overlooked by the great dome of the cathedral of San Tommaso, the Via Tripoli led out past the cemetery to emerge as the main coast road to the north.126

The Edmontons, attacking northward on a two-company front, spent the whole of 21 December clearing the score or more of scattered buildings which spread across the southern outskirts of the town. By nightfall they had reached the Piazza Vittoria, at the beginning of the main built-up portion of Ortona, where they were within a quarter of a mile of the central square.127 The Seaforths’ “C” Company had a stiff fight to clear the church of Santa Maria di Constantinopoli in the extreme south-east corner of the town, and during the afternoon the Brigade Commander ordered the full battalion to be committed to assist the Edmontons in what was developing into a major task.128

Although these were relatively modest gains, a misconception of what the Canadians had achieved during the day produced a feeling of gloom in the highest German military circles. The 1st Parachute Division’s daily report to the 76th Corps stated without elaboration that an enemy attack south-west of Ortona had been repulsed. Hitler’s headquarters, interpreting this reticence as the normal forerunner of bad news, assumed that the town had been lost. “The High Command called me on the phone,” Westphal told Wentzell that afternoon. “Everybody was very sad about Ortona.” “Why”, replied the Tenth Army Chief of Staff, “Ortona is still in our hands.129 It may have been to guard against any recurrent lapse of confidence that on the evening of the 22nd – when the Edmontons had been fighting in the streets of Ortona all day, and the report of the 1st Parachute Division spoke of hard house-to-house fighting – the Tenth Army’s war diary recorded. “Contrary to the reports of the opponents, the enemy is still outside Ortona.”130

Edmonton patrols reporting before first light on 22 December disclosed the effectiveness of the defenders’ demolition plan. The Corso Vittorio Emanuele was free of barricades for 300 yards or more, but all other lines of advance were blocked by the debris of houses which German engineers had systematically toppled into the narrow streets. It looked as though the defenders intended to channel the Canadian attack along the main street to the open Piazza Municipale, which they hoped to make a “killing ground”. Jefferson decided to clear the enemy from both sides of this central route

so that the street itself might be swept of mines to enable tanks to penetrate the town.131 “A” Company took the left and “D” the right, with “B” Company carrying out flank protection in the troublesome area between the main Corso and the esplanade overlooking the harbour. Company tasks were divided into platoon and section objectives, and commanders instituted a strict system of reporting each house clear before starting on the next. House by house and block by block the infantry worked forward, followed by the armour. By nightfall the Edmontons had reached the Piazza Municipale, but 25 yards short of it a high pile of rubble stopped further advance by the tanks.132

The day, typical of those to follow, had been one of bitter struggle against a stubborn and vicious defence. The German paratroopers, fresh, well trained and equipped and thoroughly imbued with Nazism, fought like disciplined demons. Each sturdy Italian house that they elected to defend became a strongpoint, from every floor of which they opposed the Canadian advance with fire from a variety of weapons. They left other buildings booby-trapped or planted with delayed charges; and if these faced houses which they were holding, they demolished the front walls in order to expose the interiors to their own fire from across the street. Every obstructing pile of rubble was covered by machine-guns sited in a second storey, and the litter of shattered stone and broken brick usually concealed a liberal sowing of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines.133

Although the employment of armour in such restricted conditions was anything but orthodox, the Three Rivers tanks gave the infantry invaluable support. They became in turn assault guns, their 75-millimetre shells smashing gaping holes in the walls of enemy-held buildings, and individual pillboxes, covering a sudden sally by our infantry with sustained bursts of machine-gun fire; frequently they carried ammunition forward and evacuated casualties through the bullet-swept streets. They performed these tasks under constant threat from German anti-tank guns sited to cover the obvious approaches and often concealed close behind the barricades so as to catch the attacking tank’s exposed underside as it climbed over the rubble.134

From the Piazza Municipale the Edmonton commander continued towards the Via Tripoli, intending to cut off the garrison holding the north-eastern portion of the town. Early on the 23rd a troop of tanks managed to scale the barrier blocking the Corso Vittorio Emanuele; yet even with this support it took the infantry the whole of that day to cover the 200 yards to the wide Piazza San Tommaso in front of the cathedral. On the right another Edmonton company had by nightfall secured the south end of the Corso Umberto I, which, being free of buildings on its seaward flank, could be covered by Canadian anti-tank fire and on that account offered a promising means of approach to the Castle.135

Their heavy casualties had left the Edmontons in a weakened state; none of the infantry battalions of the 1st Division had received any reinforcements since crossing the Sangro, and Jefferson was reduced to fighting on a basis of three companies of 60 men each. On 22 December “D” Company of the Seaforth had been given the task of clearing the left flank, and the entry of the remainder of the battalion into battle on the 23rd further eased the heavy strain on the Edmontons. The two commanders divided the town between them – the Seaforth to take the western half, and the Edmontons to push along the Corso Umberto I to the Castle and the cemetery beyond.136

In their grim efforts to advance the infantry received magnificent support from the anti-tank guns – which were better suited than field guns for shooting at such short ranges. The battalion six-pounders and the six- and 17-pounders of the 90th Anti-Tank Battery were employed with devastating effect against enemy-occupied buildings. In the early stages of the fighting two six-pounders covered the advance of the infantry and tanks along the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, each firing high-explosive shells into the windows along either side of the street immediately ahead of the leading troops. When enemy fire prevented the sappers from demolishing the barricades of rubble which blocked the streets, the same guns blew the crests off the piles, enabling our tanks to mount them. As resistance in the streets stiffened, and infantrymen had to battle their way forward house by house, anti-tank gunners were called on to smash a way through. They obtained particularly effective results by first penetrating an obstructing wall with an armour-piercing round fired at close range, and then sending a high-explosive shell through the breach to burst inside. German snipers posted on the tops of buildings received short shrift: one round from a six-pounder was usually sufficient to blast a tile roof to pieces. From a ridge south-east of the town two 17-pounders, firing at a range of 1500 yards, systematically ripped apart buildings which the infantry indicated along the sea front.137

Failing in their attempt to outflank the enemy by striking up the Corso Umberto I, the Edmontons reverted to their former practice of working forward house by house. The necessity for getting from a captured house to the next one forward without becoming exposed to enemy fire along the open street produced an improved method of “mouse-holing” – the technique, taught in battle-drill schools from 1942 on, of breaching a dividing wall with pick or crowbar.138 Unit pioneers set a “Beehive” demolition charge in position against the intervening wall on the top floor, and exploded it while the attacking section sheltered at ground level. Before the smoke and dust had subsided the infantry were up the stairs and through the gap to oust the enemy from the adjoining building. In this manner the Canadians cleared whole rows of houses without once appearing in the street; and as they progressed the German paratroopers automatically vacated the buildings on the opposite side.139

By this time the enemy had belatedly admitted the forced entry into Ortona. The Tenth Army war diary on the 23rd disclosed an attack by “two battalions, supported by flamethrowers* and 17 tanks

* A misstatement – only the Germans used flamethrowers in the battle for Ortona.

... used as artillery”, and reported that “the number of our own casualties” had compelled the abandonment of the “more remote and southernmost positions ... after exceedingly hard fighting.”140 Next day the 1st Parachute Division reported that “in hard house-to-house fighting the enemy advanced to the centre of Ortona.”141

Heidrich now had two battalions in Ortona – the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Parachute Regiment, which had borne the brunt of the early Edmonton attacks, and the 2nd Battalion, 4th Regiment,†

† This unit had been held in divisional reserve at Torre Mucchia, three miles up the coast from Ortona. “The mistake was that 2 Bn. 4 Regt. was kept too far back”, Kesselring complained to Lemelsen on Christmas Day.142

which was pushed into the battle on the 24th.143 The remaining units of the 1st Parachute Division were in position between the coast and Tollo, covering San Tommaso, San Nicola and Villa Grande; the divisional reserve was reduced to a single infantry company at Tollo.144 On Heidrich’s immediate right was the Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion Hermann Goring, which Kesselring, in his efforts to find forces to stop the Eighth Army, had detached from its parent formation west of the Apennines.145 This action by the C-in-C South-West incurred the severe displeasure of Goring himself. “I received a terrific blast from the Reichsmarschall today”, Kesselring told Lemelsen on 23 December. “He said that I had no understanding for his division and demands that it be committed as a compact force and not piecemeal with the Recce people at one coast and the infantry at the other.”146

“For some unknown reason the Germans are staging a miniature Stalingrad in hapless Ortona”, wrote the Associated Press correspondent on 22 December.147 Had he, instead of Lemelsen, been listening to Kesselring on the telephone on Christmas day he would not have been left in doubt. “It is clear we do not want to defend Ortona decisively”, the Field Marshal told the acting Commander of the Tenth Army, “but the English have made it appear as important as Rome.” He agreed with Lemelsen’s protest, “It costs so much blood that it cannot be justified”, but argued “ ... you can do nothing when things develop in this manner; it is only too bad that ... the world press makes so much of it.”148

Kesselring may well have been trying to rationalize an unhappy situation, yet it was true that by mid-December this formerly insignificant town on the Adriatic coast had acquired considerable prominence. On the 8th it was merely the Adriatic end of “makeshift German defences”,149 but by the 14th

the Associated Press from Algiers was calling it a “strategic road junction”.150 Newspaper despatches emphasized the violence of the enemy’s counterattacks and underlined the fact that he had had to throw in three divisions to defend Ortona; and on 16 December the Associated Press cited a captured document which ordered the Germans to hold on at all costs.151

This forcible reminder of the power of the press to turn a limited tactical operation into a long and costly “prestige” battle was not lost upon the Allied commanders. Before the next offensive opened Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy took special care to instruct Public Relations Officers and censors to ensure “a truer presentation of what has actually taken place ... than has been the case in previous battles.” An echo of the fighting in Ortona was heard clearly in one such directive: “DON’T before Rome is captured claim it as a great military objective. Show that Rome as a town has no military significance.”152

Christmas Day – and the End of the Battle

Long after the lessons of Ortona recede into the pages of military textbooks men who were there will remember how, despite their joyless surroundings, the two Canadian battalions observed Christmas Day. Nothing could be less Christmas-like than the acrid smell of cordite overhanging Ortona’s rubble barricades, the thunder of collapsing walls and the blinding dust and smoke which darkened the alleys in which Canadians and Germans were locked in grim hand-to-hand struggle. The daily report of the 76th Corps testified to the bitterness of the day’s fighting:

In Ortona the enemy attacked all day long with about one brigade supported by ten tanks. In very hard house-to-house fighting and at the cost of heavy casualties to his own troops [he] advanced to the market square in the south part of the town. The battle there is especially violent. Our own troops are using flamethrowers, hand grenades and the new Ofenrohre*

* The Ofenrohr (stovepipe) or Panzerschreck (tank terror), the German counterpart of the United States “bazooka”, was an 88-millimetre anti-tank rocket launcher, firing a hollow-charge rocket projectile weighing about seven pounds.153 Another enemy anti-tank weapon which had just made its appearance in the Italian theatre (one was captured intact at Ortona) was the Panzerfaust 30, or Faustpatrone 2, a single-shot, expendable, recoilless grenade discharger, firing a hollow-charge bomb comparable to that of the PIAT.154

...155 In such dreadful circumstances did men thousands of miles from home keep the greatest of all home festivals.

Battalion administrative personnel were determined that, whatever the situation, their rifle companies should have a Christmas dinner. The

Seaforths’ banquet hall was the abandoned church of Santa Maria di Constantinopoli. Let their diarist relate the event:

The setting for the dinner was complete, long rows of tables with white tablecloths, and a bottle of beer per man, candies, cigarettes, nuts, oranges and apples and chocolate bars providing the extras. The CO, Lt-Col. S. W. Thomson, laid on that the Companies would eat in relays ... as each company finished their dinner, they would go forward and relieve the next company. ... The menu ... soup, pork with apple sauce, cauliflower, mixed vegetables, mashed potatoes, gravy, Christmas pudding and mince pie. ...

From 1100 hours to 1900 hours, when the last man of the battalion reluctantly left the table to return to the grim realities of the day, there was an atmosphere of cheer and good fellowship in the church. A true Christmas spirit. The impossible had happened. No one had looked for a celebration this day. December 25th was to be another day of hardship, discomfort, fear and danger, another day of war. The expression on the faces of the dirty bearded men as they entered the building was a reward that those responsible are never likely to forget. ... During the dinner the Signal Officer ... played the church organ and with the aid of the improvised choir, organized by the padre, carols rang out throughout the church.156

Nor had a sense of humour been lost when the Padre remarked, “Well, at last I’ve got you all in church.” The Edmontons, marking their fifth Christmas on active service with “the fiercest fighting so far encountered”, ate their Christmas dinner in small groups, as officers and men were relieved from battle a few at a time to share what was to be for some their last meal.157

German records reveal that during the week before Christmas the Tenth Army had given serious consideration to launching a concentrated offensive which would “annihilate those elements of the Eighth Army which are north of the Sangro.”158 “The Christmas feast days are best suited to our purpose”, Herr had written to Lemelsen, “as the enemy will think that the Germans will then be in a soft mood.159 The plan was a bold one, based upon the conclusion that Montgomery’s concentration of the Canadian, Indian and New Zealand Divisions in the northern coastal sector, with the bulk of his artillery well forward, had left him with few reserves behind the front. (The 5th British Division was not expected to arrive from the interior in time to affect the issue.*)

* On 21 December Lemelsen reported to Kesselring that “the enemy is moving up 5 Brit Div”.160 Actually on that date the Division had been in the line for five days.

German defensive action was known to have inflicted very considerable casualties upon the three divisions in the Eighth Army’s front line, and Herr believed that a sudden blow might achieve victory before their striking power could be restored. The Tenth Army plan envisaged a three-fold thrust. On the inland flank the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division would attack from the south-west to envelop Montgomery’s left wing; in the centre an assault force made up of every available unit of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division (which had been earmarked to relieve the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division), the 334th (newly arrived from France) and the 65th Infantry

Divisions and the 26th Panzer Division would drive eastward from the Orsogna–Guardiagrele area through Lanciano in an attempt to reach the coast between Fossacesia and San Vito; the 1st Parachute Division would then seal the fate of Montgomery’s forces by striking south from Ortona to San Vito.161

Tempting though these proposals appeared to Herr and Lemelsen, they did not win Hitler’s approval On 27 December the Armed Forces Operations Staff in Germany notified Kesselring “that the Fuhrer has given the order to desist from the planned offensive in view of the inability of the Air Force to meet requirements and because of the fact that certain formations in the theatre are slated for transfer to C-in-C West and are therefore to be relieved.”162

The “Christmas feast days” passed, and the fighting continued with unabated fury. Slowly and with mounting casualties the Edmontons forced their way towards the Castle and the Seaforth battled through the western part of the town, where their exposed left flank compelled a weakening of their front and led to several lively skirmishes with enemy parties attempting to take them in the rear.163 In the relentless struggle for the mastery no holds were barred. On the 27th a house in which an Edmonton officer and 23 of his men were distributing ammunition was blown up by a prepared charge; only four men were dug out of the ruins alive. Retaliation was swift. Two buildings occupied by the enemy were reconnoitred under cover of smoke, and infantry pioneers laid heavy charges of captured explosives during the night. When these were simultaneously blown, it was estimated that nearly two German platoons were destroyed.164

It was remarkable that amid so much death and destruction many of the people of Ortona clung to their homes and warmly welcomed the Canadians to the houses which they had been shelling for days. A British war correspondent has described the scene he stumbled upon in a basement living room in one of the forward positions:–