Chapter 13: The Battle for Rome Begins, May 1944

Allied Plans for the Spring Offensive

By the New Year of 1944 the failure of the 15th Army Group to dislodge the enemy from his Winter Line was not only causing concern to the Allied commanders in Italy but was threatening seriously to interfere with the basic strategy which had been conceived at Casablanca, Quebec and Cairo. Allied planners were keenly aware that the success of the approaching cross-Channel attack would depend upon the closest coordination of operations in the Mediterranean with that vast enterprise. At Quebec, in the previous August, the Combined Chiefs of Staff had proposed that the most effective assistance which the Allied Forces in the Mediterranean could give to OVERLORD would be to initiate “offensive operations against Southern France.”1 Three months later in Cairo it was agreed at the “Sextant” Conference that a major assault of not less than two divisions should be launched against Southern France at the same time as OVERLORD. The project was given the code name ANVIL, and shortly afterwards at the “Eureka” Conference in Teheran the decision was embodied in agreements with the Soviet Union.2 In the light of these the Combined Chiefs reported to President Roosevelt and Mr. Churchill that “ ... ‘Overlord’ and ‘Anvil’ are the supreme operations for 1944. They must be carried out in May 1944. Nothing must be undertaken in any other part of the world which hazards the success of these two operations.”3 On 6 December Eisenhower was directed to plan for the invasion of Southern France, a task which passed to General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, who succeeded him as Allied Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Theatre*

* On 9 March 1944 redesignated Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean Theatre.

on 8 January 1944.4 Responsibility for detailed planning was given to Headquarters United States Seventh Army, which since the completion of the Sicilian campaign had been relatively inactive.5

Among the assumptions on which the early planning for ANVIL was based the most important was that by May 1944 the advance in Italy would

have forced the enemy back to his prepared defences along the Pisa–Rimini line, where he might be held by such comparatively moderate pressure as would not divert Allied resources from the operation.6 But the December battles on the Adriatic and south of Cassino were evidence that this condition was unlikely to be fulfilled; until Rome had been captured no German retirement northward could be expected. Accordingly at a conference of Commanders-in-Chief held at Tunis on Christmas Day plans were initiated for the amphibious assault at Anzio. It was hoped that such an operation would turn the enemy’s flank and enforce his withdrawal north of Rome, for, as Mr. Churchill cabled to Mr. Attlee from the meeting: “We cannot leave the Rome situation to stagnate and fester for three months without crippling amalgamation of ‘Anvil’ and thus hampering ‘Overlord’. We cannot go to other tasks and leave this unfinished job behind us.”7

As we have seen, the Anzio landings produced unexpectedly strong German reaction. “None of us”, writes General Wilson, “had sufficiently realized the strength of political and prestige considerations which would induce the enemy to reinforce his front south of Rome up to seventeen divisions to seal off the bridgehead and even to expend much of his fighting strength in counter-attacks to drive us into the sea.8 These bold and desperate measures stopped the Fifth Army’s advance on both its fronts, and brought a reconsideration of the ‘Anvil’ proposal. On 18 February, at a meeting of General Wilson with his Commanders-in-Chief at Caserta, it was agreed that overriding priority must be given to linking up the bridgehead with the main effort and subsequently capturing Rome; the projected operation against Southern France (which would eventually build up to ten divisions) should be cancelled.9 The Supreme Commander communicated these recommendations to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 22 February, and asked for a fresh directive “to conduct operations with the object of containing the maximum number of German troops in South Europe”, using the forces earmarked for ‘Anvil’.10 The request was promptly met. On the 26th General Wilson received a new directive, approved by the President and the Prime Minister, which granted the Italian campaign “overriding priority over all existing and future operations in the Mediterranean” and gave it “first call on all resources, land, sea and air” within the theatre. The whole situation would be reviewed in a month’s time.11 ‘Anvil’ was postponed. The Combined Chiefs considered that to cancel the operation altogether would be strategically unsound and contrary to the decisions reached at Teheran.12 On 22 March, after receiving from General Wilson a further appreciation of the Italian situation, the British Chiefs of Staff proposed that the assault landing in Southern France “should be cancelled as an operation but retained as a threat.” The American Chiefs of Staff concurred on 19 April.13

Plans for an all-out spring offensive were agreed upon at a conference of Army Commanders held at General Alexander’s headquarters in Caserta on 28 February. The bulk of the Allied force was to be concentrated west of the Apennines. The Fifth Army’s sector would be reduced to the sea flank (as far inland as the Liri River), and the Anzio bridgehead; the weight of the Eighth Army would be transferred from the Adriatic to a narrow front covering Cassino and the entrance to the Liri Valley. The administrative problem of maintaining a greatly increased number of formations west of the Apennines was eased by the decision to retain with the Fifth Army all American-equipped United States and French formations in Italy, while all British-equipped divisions – which included Dominion, Indian and Polish forces – would return to the Eighth Army. General Alexander’s intention was to take immediate steps to secure the Anzio bridgehead, and to capture the Cassino spur and a bridgehead over the Rapido. The armies would then regroup for a full-scale attack through the Liri Valley, designed to link up with a coordinated breakout from the Anzio bridgehead and bring about the fall of Rome.14 Accordingly on 15 March the New Zealand Corps struck once more unsuccessfully against the ruined town at the foot of Monte Cassino and the broken Monastery on its crest.*

* Previous attempts to take Cassino had been made by the United States 2nd Corps on 2 February, and by the New Zealand Corps on 16 February, when the Abbey of Monte Cassino was destroyed by heavy bombing and artillery fire. The fighting during the period 20 January to 25 March has been officially designated the First Battle of Cassino.

Renewed attacks made no progress, and the termination of the battle on 25 March brought the winter offensive to an end. To the north the third major German assault against the Anzio beachhead had petered out on 3 March, and both sides passed to an active defence of the positions they then held.15

The change in the boundary between the Fifth and Eighth Armies came into effect on 26 March, and thereafter regrouping went steadily forward. The vast undertaking could not be unduly hurried, for the troops in both armies, exhausted with the winter campaign, had to be rested, re-equipped and reinforced. The tentative date for the offensive was 10 May, a timing calculated to ensure the best support being given to the Normandy invasion.16 The schedule of reliefs and moves was completed as planned and the eve of the attack found all formations ready in their new positions (see Map 12). The Fifth Army was holding a sixteen-mile front from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Liri River with two corps – the United. States 2nd Corps (Maj-Gen. Geoffrey T. Keyes) on the coastal flank and the Corps Expeditionnaire Français (General of the Army Alphonse Juin) in the mountainous region on the right. The Eighth Army’s sector extended for 55 miles from the American right boundary to the Maiella Mountains, but its centre of gravity was well to the left. From the Liri to the southern edge of Cassino was the 13th Corps, with four divisions and an armoured brigade

(the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade); on its immediate right, ready for the attack on Cassino, was the 2nd Polish Corps, with two divisions and an armoured brigade. In reserve behind the 13th Corps the 1st Canadian Corps, comprising the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, the 5th Canadian Armoured Division and the British 25th Tank Brigade, brought to a total of eight divisions and three brigades the striking force concentrated on a short ten-mile front. The Eighth Army’s right flank in the mountainous centre of the peninsula was held by the 10th Corps, and in the dormant Adriatic sector was the 5th Corps, placed directly under the command of General Alexander’s headquarters.17

During the whole of April the anxious calm which precedes great battles covered the Italian front. But while the troops were resting, training and regrouping, a battle of wits, with Rome as its prize, was being fought between Alexander and Kesselring. The German commander had shown himself strong in defence and brilliant in improvisation, but none too well served by his intelligence staffs. He had been surprised in Sicily, at Salerno and Anzio. The Allied aim was to catch him off balance once more – to hurl an overwhelming force against a sector where it was not expected, and at a moment when his mobile reserves were pinned down elsewhere by some action or a threat of action.

As the German command in Italy examined the changing picture of Allied dispositions – the transfer of the bulk of the Eighth Army westward from the Adriatic could not, of course, be concealed – it was faced with the momentous problem of deciding where and when Alexander would strike next, and which attacks would be diversionary and which the main effort. The fact that the Allied inter-army boundary was now at the Liri pointed to the imminence of a thrust up that valley, but it also increased the possibility of a seaborne operation. The Anzio landing was fresh in Kesselring’s mind, and captured documents show that he gave serious consideration to the likelihood of amphibious assaults at Gaeta, at the mouth of the Tiber, at Civitavecchia, and even at Leghorn*

* on 23 April Kesselring warned the Commander of the 14th Panzer Corps that a landing was to be expected at Leghorn, to cut off the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies from Northern Italy.18 According to his Chief of Staff, the Field Marshal believed that such an operation could have been carried out without serious interference from German air or naval forces, and would have resulted in the collapse of the entire Central Italian front.19

far to the north.20 Contemporary German records reveal frantic efforts to pierce the Allied cloak of security. Kesselring, his Army and Corps Commanders and their Chiefs of Staff demanded, ordered and pleaded for the taking of prisoners to throw some light on the mystery of Allied dispositions. Hitler attached much importance to the babbling of a Moroccan deserter;21 much was made of the statement under narcosis of a wounded and captured British officer “that the Allies would strike when the weather was favourable”;22 and radio interception teams

sought to identify units from Canadian regimental numbers carelessly divulged in the small talk of signal units near the front.23

In the interception and decoding of Allied radio messages lay the enemy’s main hope of gaining the information he so desperately needed; for his air reconnaissance was no longer able to penetrate our areas, reports of agents were woefully scanty, and prisoners were almost non-existent.24 His resultant interest in our signal traffic the Allied Command shrewdly turned to our advantage, using it as the basis of an elaborate cover plan, designed to deceive Kesselring as to Alexander’s intentions.

Outwitting the Enemy

It was known that among the weaknesses of the enemy’s Intelligence were a tendency consistently to over-estimate Allied strength and resources and, from his dearth of experience of amphibious operations, a marked inability to assess accurately the probability of an Allied seaborne assault at any particular time or place. That the Allies might lack the requisite number of landing craft for another major landing in the Mediterranean does not seem to have been realized by Kesselring. Had he known of the concern which this shortage was causing the Allied Commanders and the Combined Chiefs of Staff, he might have worried less about the vulnerability of his long coastal flank.

Playing upon this known sensitivity of the C-in-C South-West, Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy devised a scheme to produce the impression that an amphibious assault was being planned to take place on 15 May against the port of Civitavecchia, forty miles north of the mouth of the Tiber. If Kesselring could be convinced of the imminence of such an operation, there seemed a good chance that he might concentrate the bulk of his reserves in that area, leaving the Cassino front with only local reinforcements. The example of Anzio strongly aided the device, for since in January a strong attack on the Garigliano had preceded the landings, the enemy, with his attention attracted to Civitavecchia, might be expected to mistake the opening of the assault in the Liri Valley as only a diversion to a major attack from the sea.25

In the plot framed by General Alexander’s playwrights the leading role was given to the 1st Canadian Corps. Dummy signal traffic was to create the illusion that the Corps, consisting of the 1st Canadian Division, the 36th United States Infantry Division and the 5th Canadian Armoured Brigade, had assembled in the Salerno area to train for amphibious operations. This force – so ran the script – would make the initial landing at Civitavecchia,

and follow-up divisions would be drawn from the formations opposite the Tenth Army’s southern front.26

On 18 April the headquarters of the formations participating in the scheme began going off the air – the normal sign of an impending move. The silence was broken four days later as Canadian signal detachments began operating from simulated headquarters near Salerno.*

* “Notional” Headquarters of the 1st Canadian Corps was established at Baronissi, five miles north of Salerno; of the 5th Canadian Armoured Brigade at San Cipriano nearby; and of the 1st Canadian Division (on 28 April) at Nocera, ten miles north-west of Salerno. The 36th United States Division opened up on the Canadian Corps wireless net from its real location south of the River Volturno, having closed communications with the Fifth Army.27

For three weeks they maintained a steady stream of fictitious cipher messages, whose volume was carefully regulated to represent the normal flow of signal traffic between a corps and its subordinate formations. At the same time “Corps Headquarters” ostensibly kept up communications with Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy at Caserta, and the Canadian Section, GHQ 1st Echelon in Naples. To further the deception, on 2 May a signal exercise, in which units of the Royal Navy cooperated, portrayed the rehearsal of an amphibious assault on the shores of Salerno Bay. Messages in code and signals “in clear” based upon a carefully prepared script passed between a “notional” force headquarters and lower imaginary formations to convey the impression that the 1st Canadian Division, supported by two regiments of the 5th Armoured Brigade, was practising an opposed landing immediately north of Ogliastro, a town 25 miles down the coast from Salerno. Two factors made the device the more convincing: the inclusion of the 1st Canadian Division, which because of its part in the landings in Sicily and Calabria was now recognized by the enemy as an assault formation, and the close topographical resemblance which the site of the fictitious landing bore to the coastal area immediately north of Civitavecchia.

While Canadian signallers at Salerno were perpetrating this hoax upon Kesselring’s intelligence staffs, in the hilly country south-east of the Liri Valley the forces of the Eighth Army were mustering for the offensive. Elaborate precautions were taken to conceal their arrival from the enemy, for the cover plan would reap its richest dividends if Kesselring could be persuaded that there would be no attack on his southern front until some time after the threatened assault on Civitavecchia had taken place. Accordingly the transfer of the Canadian units from their training grounds was carried out in the utmost secrecy. All moves were made by night, and in each case rear parties remained behind with enough vehicles or tanks to suggest continued occupancy of the vacated areas. The arrival in the new locations was concealed by careful siting and skilful camouflaging, in which art all units had been well instructed before moving. Experts from Army and Corps supervised the work of hiding vehicles and guns in the natural protection

of some olive grove, or masking them with huge mottled green and brown camouflage nets realistically garnished with foliage.*

* For ease in camouflaging the 5th Canadian Armoured Division’s tanks were fitted with five-inch lengths of two-inch piping, welded vertically to the sides and turret. In these could be placed branches appropriate to the local background.28

The enormous tell-tale dumps of ammunition, petrol, engineer equipment and other stores which normally characterized maintenance areas were absent; instead the vast mass of material was inconspicuously distributed along roadside ditches and in the shadowed edge of clumps of trees, where, covered with nets and leafy branches, its presence was effectively hidden from possible enemy observation.29

An examination of captured German war diaries and intelligence files discloses that these various deceptive measures left the enemy very much in the dark concerning Allied dispositions and intentions. During the first few days of May Tenth Army Intelligence reported the identification of “Headquarters 1 Canadian Inf Div at Nocera”,30 and “the concentration of enemy troops in the Salerno–Naples area. Amongst others, 1 Canadian Inf Div. ...”31 A map of the Allied order of battle as known to the enemy on 12 May (the day after the main attack began) revealed a very confused picture of Canadian dispositions. Headquarters 1st Canadian Corps was unlocated; the 5th Armoured Division was shown under Polish command at Acquafondata, north-east of Cassino;†

† The German identification of the 5th Canadian Division was based on the capture on 23 April by the 5th Mountain Division of a member of The Irish Regiment of Canada, which was then employed in the 11th Brigade’s holding role in the mountains (above, p. 385).32

and the 1st Division was placed at Nocera.33 The actual situation was very different. General Bums’ headquarters was three miles south of Mignano, whither it had moved from Raviscanina on 10 May. The 5th Armoured Division was concentrated beside Highway No. 6 at Vitulazio, a few miles north of Capua. Headquarters and two brigades of the 1st Division were at Sant’ Agata, east of Caserta, while the other brigade was still at Lucera completing its training with British tanks.34

German intelligence staffs fared little better with respect to other Allied formations. The strength in both the French Corps and the Polish Corps sectors of the front was badly misjudged, and the 13th Corps Headquarters was believed to be at Termoli. In all, the enemy underestimated our strength in the area of the main attack by seven divisions.35

Having concluded that the Allies were holding in the rear large reserves, of which at least three divisions were on or near the coast, Kesselring kept his southern front thinly manned, and disposed his reserve divisions along the Tyrrhenian coast to meet the landing which he confidently expected.36 On 11 May (the day that was to end with the opening of the great Allied offensive) he announced, “I feel that we have done all that is humanly possible.37 There seemed justification for his complacency. That morning

the Commander of the Tenth Army had reported to him: “There is nothing special going on. Yesterday ... both Corps Commanders [14th Panzer and 51st Mountain] told me as one that they did not yet have the impression that anything was going to happen.”38 In the evening von Vietinghoff departed for Hitler’s headquarters to receive a decoration.

The German Defences South of Rome

The Liri Valley, through which the Allied blow was soon to be struck, formed with its western extension, the Sacco Valley, a natural corridor leading to Rome. Along its northern edge ran the Naples–Cassino–Rome railway, and Highway No. 6, perpetuating the ancient Via Casilina. The main valley is from four to seven miles wide and about twenty miles long. From a point near Ceprano, where the Liri, twisting down from the mountains about Avezzano, is joined by its Sacco tributary, it stretches south-eastward to the junction with the Gari,* six miles south of Cassino.

* This river, called the Rapido in the vicinity of Cassino, becomes the Gari lower down, before joining with the Liri to form the Garigliano.

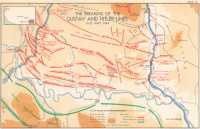

It is enclosed by rugged mountain barriers. To the south, the scrambled masses of the Aurunci and the Ausoni Mountains intervene before the narrow coastal plain. To the north rise the outlying spurs of the Meta massif, dominated by the towering 5500-foot Mount Cairo. At its Cassino end the valley is flat and open, and extensively cultivated with vine and grain, but westward the ground becomes more rolling and fairly thickly wooded with small poplars and scrub oak. Two water barriers cross the valley floor to join the Liri in its course along the southern edge – within half a dozen miles of the Gari, the Forme d’Aquino, a deep gully carrying a pair of small semi-canalized streams; and farther west the wide but shallow Melfa River, about five miles below Ceprano (see Maps 13 and 14).

To bar this promising avenue of approach to Rome Kesselring depended on three fortified lines. The first of these, already tested and in some places dented, but not broken, by persistent Allied assaults, was the Gustav Line, the rearward position of the Winter Line west of the Apennines. North-east of Cassino the massive Monti della Meta, and southward the swiftly flowing Rapido–Gari–Garigliano, were topographical obstacles which the Italian General Staff had considered could be made into an impregnable position.39 The Gustav Line was anchored on Monte Cassino, and in general followed the west bank of the river down to the Gulf of Gaeta (although for the last ten miles before the coast the Fifth Army was holding a bridgehead on the right bank about two miles deep). As might be expected, Kesselring’s engineers had devoted most attention to the open sector across the mouth

of the Liri Valley. The natural barrier of the Gari – forty or more feet wide and six to eight deep, and flowing with the speed of a millrace – they had reinforced with an extensive network of wire and minefields along the flats on the east bank. The whole of this forward zone could be swept with machine-gun fire from concrete emplacements and semi-mobile steel pillboxes on the German side of the river. These substantial positions were supplemented by deep shelters to protect the defenders against air and artillery bombardment. Most effective of all from a defensive standpoint was the fact that from the heights to north and south of the Liri Valley observers could direct artillery fire on any force attempting to cross the Gari in daylight.40

Formidable as the Gustav Line might be, experience had taught the Germans the importance of backing up each forward position with an alternative defence line, at which a large-scale attack might be held after intermediate territory had been surrendered. Accordingly in December 1943 work began on a second position to be known as the “Fuhrer Riegel” (Fuhrer Switchline). The Anzio landing however apparently caused Hitler to doubt the propriety of bestowing his name on defences which might soon be broken. On 23 January, Westphal telephoned the Tenth Army’s Chief of Staff: “We may not call the Fuhrer Riegel by that name any more; the Fuhrer has forbidden it ...”41 Next day the Tenth Army issued an order changing the name to “Senger Riegel” – a somewhat dubious compliment to General von Senger and Etterlin, the Commander of the 14th Panzer Corps.42 At the same time Kesselring ordered the position to be strengthened, under the direction of his own General of Engineers.43

Hinged on the main Winter Line at Mount Cairo, the Adolf Hitler Line (the name used by the Allied Armies) crossed the valley some eight miles west of the Gari, immediately in front of the villages of Piedimonte, Aquino and Pontecorvo. South of the Liri the Line swung south-westward through Sant’ Oliva into the Aurunci Mountains, to reach the coast at Terracina.44 In the mountainous sector on the German right flank there was little need for artificial defences; and the great strength of the Hitler Line was concentrated across the open valley between Piedimonte and Sant’ Oliva. Lacking the effective water-barrier which gave the Gustav Line its best means of resistance to tanks (for though the Forme d’Aquino, a natural tank obstacle, intersected the Line at Aquino, it diverged thence to the south-east to cross the Liri Valley obliquely), the Senger Riegel depended upon a formidable wall of concrete and steel fortifications to stop the Allied armour and infantry.

The work had been completed in five months by construction battalions, mostly non-German, labouring under the supervision of the Organization Todt, builders of the famous West Wall defences.45 By early May a line of “permanent installations” (so called by the Germans to distinguish them

from the usual type of field defences) ran from Piedimonte across the Via Casilina to Aquino, and thence along the lateral road to Pontecorvo and Sant’ Oliva. At intervals of 150 yards or more were forty shell-proof sunken shelters of sheet steel construction with an outer casing of reinforced concrete one metre thick,*

* Maj-Gen. Erich Rothe, who was in charge of construction writes of walls two metres thick.46 The smaller dimension appears in a key to conventional signs used on German engineer maps of the Gustav and Senger Lines, which was issued by Kesselring’s General of Engineers on 29 April 44.47 It was verified by the writer’s personal observation.47

each housing a section of men twenty feet below ground. Immediately adjoining each was a “Tobruk” weapon-pit. This was an underground concrete chamber with a circular neck-like opening projecting a few inches above the ground. A metal track inside the neck provided for the rotation of an anti-tank turret or machine-gun mount.48 Interspersed between these subterranean bunkers were eighteen specially constructed armoured pillboxes cased in reinforced concrete, each mounting a long 75-mm. anti-tank gun in a revolving Panther turret. It was the first appearance in Italy of this form of defence, although in North Africa the Germans had similarly used turrets from captured British tanks. Skilful camouflage concealed these miniature fortresses from Allied detection until the Line was stormed, when they disclosed their identity with deadly effectiveness and inflicted on the Eighth Army its heaviest tank losses of the Italian campaign.49

This formidable row of installations was reinforced by an extensive system of field fortifications, which included concrete shelters, mobile steel pillboxes,†

† This was a steel cylindrical cell, seven feet deep and six feet in diameter, housing a two-man machine-gun crew and their weapon. Only the top 30 inches, which was of armour five inches thick, extended above the ground. They were nicknamed “Crabs”, from their appearance when being towed on removable wheels to the place of installation.

machine-gun and rifle positions (some of concrete, others merely open weapon-pits dug in the ground), and observation posts for all weapons. Anti-tank ditches traversed all favourable approaches, and when the time came to man the Line, a fairly continuous broad belt of minefields and wire stretched across the valley. It had been intended that these field installations should serve at least four divisions in the front line, a requirement which would take, according to the engineer in charge, approximately 400 shell-proof shelters, 2786 firing positions and observation posts, and the same number of dug-outs.50 Considerably fewer than these were actually completed.

By contrast to this impressive strength, the portion south of Sant’ Oliva was much more lightly fortified. The Germans called this sector the “Dora” position (a name which they eventually gave to the entire Line in anticipation of its fall), and they obviously relied on the rock cliffs of the Aurunci Mountains to break any Allied attack which might pierce the Gustav defences. There were no permanent installations, but only fairly widely distributed shelters and weapon-pits cut into the hillside and camouflaged with rocks

and stones. Construction was far from complete when the Fifth Army struck on 11 May.51

While the Gustav and Hitler Lines might together be reasonably regarded as an effective block to any Allied thrust up the Liri–Sacco Valley, their security was seriously threatened by the presence at Anzio of a strong Allied force many miles to their rear. A breakout from the bridgehead reaching Highway No. 6 would render the Hitler Line useless as a barrier to Rome. Kesselring recognized the need for a defence line north of Anzio from which in the event of a forced German withdrawal the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies could, side by side, further delay the capture of Rome. Early in March he ordered construction work on the Caesar Line to be pushed forward and completed by 20 April.52 This line (whose name denoted “C” in the phonetic alphabet, and bore no historical significance) crossed the peninsula from the sea coast west of Velletri*

* The first “C” Line, reconnoitred in December 1943, began near Littoria, leaving the Tyrrhenian coast a dozen miles below Anzio. After the Allied landings the alternative position through Velletri was adopted. It skirted the bridgehead to the, north, and joined the original position near Avezzano.53

(a town on the southern slopes of the Alban Hills) to the Saline River, north-west of Pescara. Defences were not designed on the elaborate scale of the Hitler Line, and in many instances were never completed. By May the most developed section was in the vital Valmontone area, where Highway No. 6 cut through the gap between the Alban Hills and the Prenestini Mountains. Eastward to the Adriatic, very little work had been done54 (in spite of the fact that the Tenth Army was employing in its sector alone, which extended from west of Highway No. 6, 25 construction battalions, twelve of them Italian, and four rock-drilling companies)55 As events turned out, Canadian forces were to be little concerned with the Caesar Line. The Germans were quite unable to stabilize on this last-ditch position, and before General Alexander’s advancing armies reached it Canadian soldiers had already performed their allotted task in the Liri Valley. The bitter fighting in which they broke through the strongest of all the enemy’s positions there was to link lastingly the name of the 1st Canadian Corps with that of the Adolf Hitler Line.

The April lull which had enabled the enemy to push forward the work on his defence positions had also allowed him to rest and regroup his forces. He withdrew his motorized divisions from the front lines and disposed them along his coastal flank so that they might build up their strength and be ready to counter the Allied landing which he believed to be imminent (see Map 12). Thus by 11 May, of the three†

† A fourth motorized formation-the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division-was holding the line of the bridgehead under the 1st Parachute Corps of the Fourteenth Army. Weakened by more than 4000 casualties sustained in continuous frontline duty since the first landings at Anzio, it wad of dubious value as a mobile reserve.56

Panzer Grenadier Divisions which constituted Kesselring’s potential mobile reserve, the bulk of the 15th had

moved down from the Liri Valley to the Fondi area to protect the Tenth Army’s right flank from amphibious attack by watching the sector between the Gustav Line and the bridgehead; the 90th was reorganizing between the northern flank of the bridgehead and the Tiber; the 29th was stationed north of Rome about Viterbo, covering the Civitavecchia area. These last two divisions were being held in army group reserve; in fact all three might be moved only on Kesselring’s orders.57 Of the two German armoured divisions in Italy, the 26th Panzer Division was on the Anzio front, as an armoured reserve for the Fourteenth Army in case of an Allied breakout, and the Hermann Goring Division was north of Leghorn, where it was being held as an Armed Forces High Command reserve, earmarked for France.58 Thus, when the Allies struck at the Gustav Line, the German mobile reserves were too far away to give immediate help; and in any case none of them was under the control of either army.

The transfer of the Tenth Army’s weight to its right flank which had matched the Allied concentration west of the Apennines had brought necessary changes in the German chain of command. The 14th Panzer Corps, on a narrowed front extending from Terracina to the Liri River, controlled the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division on the coast and two infantry divisions (the 94th and the 71st). General Feurstein’s 51st Mountain Corps Headquarters was brought down from the Adriatic to take over the sector north of the Liri, leaving the eastern flank, opposite the British 5th Corps, the responsibility of “Gruppe Hauck” – a force directly under Army Command, composed of the 305th and 334th Infantry Divisions, and bearing the name of the former’s commander (Lieut.sh General Friedrich Wilhelm Hauck).59 In the plans for the final regrouping of the Tenth Army, Feurstein was allotted four divisions. He held his mountainous left flank from the Maiella to the northern slopes of Mount Cairo with the 114th Jäger*

* The Jäger or light division was similar in organization to the mountain division, but its greater mobility suited it for employment in flat as well as mountainous terrain.

and the 5th Mountain Divisions.60 To defend the Cassino front he had General Heidrich’s 1st Parachute Division and the 44th† Infantry Division,61 commanded by Lt-Gen. Bruno Ortner.62

† The 44th Infantry Division carried the honorary title Reichsgrenadierdivision “Hoch und Deutschmeister” (originally that given to the Grand Master of the Order of Teutonic Knights). German documents identify the formation by the abbreviation H. u. D. as commonly as by its numerical designation.

Misled as to the direction and unaware of the imminence of the Allied attack, the Germans were still rearranging their forces in the Liri Valley when the 13th Corps struck across the Gari on 12 May. The 1st Parachute Division was holding the important Mount Cairo–Cassino hinge, where Feurstein and Heidrich expected the main pressure would come.63 South of Cassino Ortner’s headquarters had relieved the 15th Panzer Grenadier

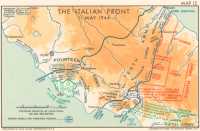

The Italian Front, 11 May 1944

Division, but his two infantry regiments were still in the mountains to the north (the 134th Grenadier Regiment under command of the 5th Mountain Division, the 132nd under General Heidrich).64 Pending their expected arrival the line of the Gari from Cassino to the Liri was comparatively lightly manned by the 1st Parachute Division’s Machine Gun Battalion, two battalions of the 115th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (which had not accompanied the rest of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division to the coast), and two from the 576th Grenadier Regiment of “Blocking Group Bode”, brought down from the mountainous centre of the peninsula.65

In the early stages of planning General Alexander had affirmed that a force attacking organized defences in Italian terrain needed “a local superiority of at least three to one”.66 By the second week in May skilful Allied manoeuvre had produced just such a disparity of strength in the battle area. Along the line of the Garigliano, from Cassino to the sea, four German divisions opposed an Allied strength of more than thirteen.67

The Assault of the Gustav Line, 11 May

Detailed plans for the Allied offensive emerged from an Army Commanders’ Conference held on 2 April at Caserta, and were confirmed at a final meeting on May Day. In his operation order of 5 May Alexander defined the intention of the Allied Armies in Italy “to destroy the right wing of the German Tenth Army; to drive what remains of it and the German Fourteenth Army North of Rome; and to pursue the enemy to the Rimini–Pisa line, inflicting the maximum losses on him in the process.”68 The initial task in this comprehensive programme, which thus envisaged the capture of Rome and a sweeping advance of 200 miles up the Italian peninsula, was a simultaneous frontal attack by both Allied Armies on the night of 11 May. General Leese’s divisions were to force an entry into the Liri Valley and advance up Highway No. 6 on Valmontone. On their left the Fifth Army was to break through the Aurunci Mountains and drive forward “on an axis generally parallel to that of [the] Eighth Army but south of the Liri and Sacco Rivers”.69 On Leese’s right the 5th Corps, holding its front with minimum troops, would follow up the expected German withdrawal. It was calculated that the launching of these blows against his southern front would draw in all the enemy’s resources and weaken his forces encircling the bridgehead. The achievement of this object, to be effected by the time that the second line of defence (the Hitler Line) had been broken, would mark the moment for General Clark’s 6th Corps to strike inland from Anzio and join the forces advancing up the valley.70 The breakout from the bridgehead was to be in readiness from D plus four.

By thus timing his punches General Alexander ensured that each would receive the undivided support of his air effort. Already the Allied air forces were taking full advantage of a supremacy of nearly 4000 aircraft over an enemy strength of 700 (half of which were based in Southern France and Yugoslavia). From 19 March to D Day the Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Force*

* On 10 December 1943 the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, commanded by Lt-Gen. Ira C; Eaker, replaced the Northwest African Air Forces and the Mediterranean Air Command. In the following March the major components of the NAAF were redesignated the Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force, Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Force, Mediterranean Allied Coastal Air Force, and Mediterranean Allied Photographic Reconnaissance Wing.71

concentrated all its power in Operation “Strangle” – a mighty programme of interdiction against the enemy’s rail, road and sea communications south of the Pisa–Rimini line, designed to prevent his acquiring the necessary stocks with which to increase his resistance to the forthcoming ground attack.72 Meanwhile, as the Coastal Air Force harassed the sea lines of supply, bombers of the Strategic Air Forces attacked railway junctions, marshalling yards and bridges in Northern Italy. From the last week in March all lines to Rome and the front were continuously cut, so that no through rail traffic approached nearer to the capital than 50 miles, and usually no closer than 125 miles.73 The tasks for D Day were to isolate the battlefield by maintaining this disruption of German communications; by counter air force operations to keep the Luftwaffe in a state of ineffectiveness; and to neutralize the gun positions commanding the crossings over the Gari River.74

The Eighth Army’s part in the offensive was formulated at a series of conferences in April and early May.75 Following Eighth Army practice, General Leese, beyond giving his Corps Commanders a short directive, issued no written operation order. In simultaneous assaults on the Gustav Line the 13th Corps would make a frontal attack across the Gari below Cassino, while the 2nd Polish Corps struck through the mountains to turn the line from the north. Their junction on Highway No. 6 would isolate Cassino and “Monastery Hill” and prepare the way for their capture. The 10th Corps was to secure the Army’s right flank and stage a demonstration to delude the enemy into expecting an attack against his thinly held positions in the centre of the peninsula. The Canadian Corps, in army reserve at the beginning of the offensive, would be prepared for one of two alternative roles, depending upon the progress of the battle. If the 13th Corps should succeed in breaching both German lines of defence, the Canadians would pass through and exploit up Highway No. 6 towards Rome. If on the other hand – and Leese considered this the more likely possibility – General Kirkman’s formations encountered strong opposition after establishing the initial bridgehead, the Canadian Corps would be called on to cross the Gari and go into action on the left of the British Corps.76

Although it was not expected that the Canadian infantry would be required before the night of 14–15 May,77 Canadian artillery and armour would be engaged in the attack from the very first. Less than half a dozen miles east of the Gari, regiments of the 1st Army Group RCA and the divisional artilleries waited in carefully concealed gun areas between the hills for the signal that would start the biggest bombardment programme yet fired in the campaign by Allied gunners.78 Nearby on the narrow flats beside Highway No. 6 the squadrons of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade*

* The 12th Canadian Armoured Regiment (Three Rivers Regiment) had come under command of the 13th Corps on 27 March; its squadrons had supported units of the 4th and 78th British Divisions and the Polish 3rd Carpathian Division north-east of Cassino.79

were assembled ready to help the 13th Corps infantry win the initial bridgehead across the river.80

There was an understandable feeling of tension among the Canadian troops, but morale was high. The exhilarating prospect of action was accompanied by a confidence that in winning the approaching battle the Allied Armies would not only strike a disastrous blow at the enemy in Italy, but would contribute materially to the liquidation of Hitler’s empire. An inspiring message addressed to the “Soldiers of the Allied Armies in Italy” came from General Alexander on the eve of the battle:–

The Allied armed forces are now assembling for the final battles on sea, on land, and in the air to crush the enemy once and for all. From the East and the West, from the North and the South, blows are about to fall which will result in the final destruction of the Nazis, and bring freedom once again to Europe and hasten peace for us all. To us in Italy has been given the honour to strike the first blow.

We are going to destroy the German armies in Italy. The fighting will be hard, bitter, and perhaps long, but you are warriors and soldiers of the highest order, who for more than a year have known only victory. You have courage, determination and skill. You will be supported by overwhelming air forces, and in guns and tanks we far outnumber the Germans. No armies have ever entered battle before with a more just and righteous cause.

So with God’s help and blessing, we take the field-confident of victory.

Cloudy skies over Latium on 11 May cleared in the evening, but a thick ground mist in the Liri Valley partly obscured a moon four days past its full. At 11:00 p.m. the thunder of artillery broke along the entire Allied front, as all medium and heavy guns of the Fifth and Eighth Armies began neutralizing the enemy’s gun positions with massive concentrations of fire. On the Eighth Army’s front 1060 guns of all kinds were deployed;81 the Fifth Army was using approximately 600.82 In the 13th Corps’ sector the counter-battery programme went on for forty minutes, and then abruptly switched to a barrage from 17 field and four and a half medium regiments, as the 4th British and 8th Indian Divisions attacked across the Gari. At 11:45 the first assault boats were launched into the swirling river, and

crossings began in four brigade sectors. The Indian Division was on the left; the task of its four assaulting battalions was to secure an immediate bridgehead at, and south of, the village of Sant’ Angelo in Teodice, midway between Cassino and the Liri83 (see Map 13). The three regiments of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade were under command of the Division, but until the Gari had been bridged the assaulting infantry would of course be without tanks. A novel form of support, however, was provided by three troops of the Three Rivers Regiment, which moved up to the east bank and covered the Indians’ crossing*

* The troops of the Three Rivers Regiment had been carefully trained for three weeks for their night fire task, and there seems little doubt that the volume of fire which they blasted across the river helped to keep the Germans’ heads down as well as greatly contributing to the morale of the assaulting infantry. The Commander of the 17th Indian Brigade declared that the assistance of the Canadian tanks was invaluable.84

with high-explosive and machine-gun fire.85

The attack got off to a bad start. The swift current capsized assault boats and swept many downstream (in one of the 4th Division’s brigade sectors all but five boats out of forty had been lost by early morning);86 and the enemy’s automatic and small-arms fire was even heavier than had been expected. Only a shallow bridgehead had been secured by daybreak. The vital business of constructing tank-bearing bridges had begun, but German domination of the 4th Division’s precarious holding between Sant’ Angelo and Cassino halted the work in this sector. On the left the Indians had been more successful, and the infantry had reached the lateral road which ran along the low escarpment west of the river. Exposed to withering fire, and hampered by fog and the smoke from the dense screens with which each side was attempting to confuse the other, Indian engineers toiled heroically throughout the night preparing launching sites and approach ramps, and bolting together their Bailey sections into the required span. By 8:40 on the morning of the 12th they had completed “Oxford” bridge, about a mile south of Sant’ Angelo; but their efforts at a second site above the village had been stopped by the German fire.87

Five hundred yards below “Oxford” bridge, at a point where the Gari curved close to the lateral road, a third site, “Plymouth”, had been selected; but throughout the night it had remained free from engineer activity. A new experiment in assault-bridging was about to be made. About an hour after the completion of “Oxford” bridge two Shermans of The Calgary Regiment approached the Gari, the front one, with turret removed, bearing the weight of a complete 100-foot Bailey span, which had been constructed in relative concealment from the enemy’s fire, 600 yards to the rear. An officer walked coolly alongside, controlling their direction and speed by telephone. Without pausing, the leading tank drove down the soft bank into the bed of the river, the crew escaping just before it submerged. The rear tank thrust

forward, and the bridge slid across the back of the carrying Sherman to the far bank. The pusher tank disconnected, and fifteen minutes from the time it left its building-site the bridge was in position*

* This method of launching a Bailey bridge from the backs of tanks was employed, with various modifications, in subsequent operations in Italy. Its initial success was largely due to the ingenuity and courage of Captain H. A. Kingsmill, an officer of the Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, attached to The Calgary Regiment, who developed the bridge after many experiments in the Volturno Valley. His cool efficiency in conducting the launching under heavy fire after he had been wounded by a shell, brought him the MC.88

across the 60-foot water gap.89

Each of the two assaulting Indian brigades now had a bridge over the river, and without delay troops of Canadian tanks, the olive branches of their camouflage belying their warlike intent, drove across to succour the hard-pressed infantry. Two squadrons of The Ontario Regiment, supporting the 17th Indian Brigade in the Sant’ Angelo sector, crossed at “Oxford”, but before they could reach the lateral road half their tanks were bogged in the marshy river flat. During the afternoon two Sherman recovery tanks of the 59th Light Aid Detachment RCEME returned fourteen of these to action,90 and the Ontarios spent the rest of the day under heavy fire clearing isolated enemy positions south of Sant’ Angelo and slowly working their way northward along the river road, which provided the only approach for armour to the village.91 On the 19th Brigade’s front, “Plymouth” bridge was temporarily put out of action by a shell after only four tanks of the Calgaries’ leading “A” Squadron had crossed. “Oxford” bridge now provided the sole means by which armour could cross the Gari; yet before nightfall the greater part of five Canadian squadrons had reached the German side of what the enemy had regarded as an impassable tank obstacle. (“A” Squadron of The Ontario Regiment remained on the near bank giving supporting fire to the 4th Division’s brigade north of Sant’ Angelo.) There were frequent delays, as Shermans were trapped in the treacherous footing between road and river, and many were stopped by mines.92 Those that reached firm ground quickly relieved the pressure on the Indian infantry. On the left flank of the bridgehead the surviving four tanks from the Calgary “C” Squadron, unable to link up with the infantry, who had become widely dispersed in the withering fire, pushed westward 1000 yards to the village of Panaccioni†

† This penetration by Canadian armour was recorded with concern by a 14th Panzer Corps Intelligence Report of 12 May: The deep northern flank of 14 Pz Corps is being threatened by the enemy, who has broken through at S. Angelo and who has deployed tanks able to fire to the south between 53/12 and 53/13 [i.e., along the left bank of the Liri, south of Panaccioni].93

playing havoc with the enemy’s strongpoints, and engaging transport retreating up the valley.94

The general situation across the Allied Armies’ front at the end of the first day’s fighting was not as favourable as had been hoped. In the Fifth

Army’s sector south of the Liri both the 2nd Corps – and the French had encountered stubborn opposition, and had achieved no break-through. The Eighth Army’s position was no better. On the right the Poles after bitterly fighting their way on to an early objective north-west of the Monastery had been driven back to their starting line by very heavy fire and a vicious counterattack. The 13th Corps had gained only half of its initial objectives, and the 4th Division’s bridgehead north of Sant’ Angelo was still without armour. Nevertheless the Gustav Line had been penetrated, if not very deeply, and there were tank-bearing bridges across the Gari.95

General Alexander’s Armies had received the fullest support from the Allied air forces, which in spite of intermittent bad weather, had flown that day a record-breaking 2991 sorties. Yet it must be recorded that the earlier programme of interdiction, while it hampered the Germans and strained their motor transport, had not succeeded in isolating the battlefield; research shows that both the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies were more adequately supplied at the start of the May offensive than in earlier or later operations in Italy.96 Early on the 11th, in a striking gesture of encouragement to our troops and intimidation to the enemy, heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force paraded low along the battle front before delivering 375 tons of bombs on Kesselring’s personal headquarters north of Rome and Tenth Army Headquarters*

* According to the Tenth Army’s Chief of Staff, the air raid seriously disrupted the operations of the Army Headquarters, which shortly afterwards joined the 14th Panzer Corps Headquarters at Frosinone.97

near Avezzano.98 Medium and light bombers of the Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Force (the Twelfth Tactical Air Command, formerly the Twelfth Air Support Command, and the Desert Air Force) concentrated on command posts in the rear of the Hitler Line, while in the forward areas fighter-bombers smashed at German gun positions across the Liri Valley and behind Cassino.99

It had been a day of painful surprises to the enemy, but after the initial shock he had acted with his customary resilience to stabilize the situation. It was too early to assess the full scope of the Allied intention – the 14th Panzer Corps looked for “an expansion of the battle through a landing operation”,100 while the Fourteenth Army expected “an attack from the bridgehead ... at any moment ... and new landings either between the southern flank of Tenth Army and the bridgehead ... or at the mouth of the Tiber and to the north of it. ...”101 But the penetration had to be sealed, and from midday to midnight a succession of orders emanated from Army and Corps Headquarters for the dispatch of reinforcements to the front south of Cassino.102 Calling in reserve detachments of company strength from the 5th Mountain and 114th Jäger Divisions on his left flank, Feurstein provided a small measure of assistance to his outnumbered forces behind the Gari, and hastily assembled north of Aquino a battle group built around the hard core of two battalions of the 1st Parachute Regiment. This Battle

Group Schulz (so-named from the regimental commander) he placed at the disposal of the 1st Parachute Division, at the same time extending Heidrich’s command southward over the 44th Division’s area.103 As a more substantial counter-measure Feurstein demanded and obtained the dispatch of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division’s 200th Grenadier Regiment to the Liri Valley. Kesselring, however, was not yet ready to abandon his fear of a landing behind the front, and reserved to himself the decision to commit the regiment*

* On its arrival in the Pontecorvo area on the 13th it was assigned to the 14th Panzer Corps’ hard-pressed. 71st Infantry Division south of the Liri.104

to action.105 Events. were to show that these hasty but niggardly measures would not suffice to stem the tide.

Early on the morning of 13 May a bridge was completed over the Gari between Sant’ Angelo and Cassino, and tanks of the 26th Armoured Brigade crossed into the bridgehead to lead the 4th Division’s attack.106 British tanks and infantry overran Heidrich’s Machine Gun Battalion, which was ordered to fight its way back to Battle Group Schulz.107 Sant’ Angelo, keystone of the German resistance in the 13th Corps’ sector, fell early in the afternoon. Two companies of Gurkhas stormed the village at midday, after a five-minute bombardment by seven field regiments. Tanks of The Ontario Regiment helped silence the defenders’ machine-guns, and at the end of an hour’s deadly fighting Sant’ Angelo was won.108

The way was now open for our armour to deploy on the open ground to the west. An attack towards Panaccioni by two battalions of the 19th Indian Brigade with the support of The Calgary Regiment proved the worth of joint training exercises conducted in preceding weeks on the banks of the Volturno by Indian infantry and Canadian armour.†

† Between 23 April and 8 May each battalion of the 8th Indian Division’s two assaulting brigades attended a two-day “infantry-cum-tank” course with the Ontario and Calgary Regiments.109

Displaying fine teamwork the Canadian Shermans knocked out many a machine-gun nest opposing the infantry’s advance, while in turn keen-eyed Indian riflemen successfully directed the Calgaries’ cannon fire against German self-propelled anti-tank guns lurking behind heavy foliage or hidden in sunken lanes. In a fierce late afternoon assault the 6th (Royal) Battalion, Frontier Force Rifles, captured Panaccioni, and with it a battalion headquarters of the 576th Grenadier Regiment.110 That night, while the German 44th Division was reporting a withdrawal of 1500 yards from the Gari,111 the British 78th Division passed through the Indian bridgehead and attacked north-westward towards Highway No. 6.112

The next two days saw a steady enlargement of the bridgehead, but only after much hard fighting. Early on the 14th squadrons of the Three Rivers Regiment went into action with the 21st Indian Brigade in a drive to cut the lateral road which traversed the valley from Cassino to San Giorgio a

Liri, crossing the river south of Pignataro. Their way lay across a formation of low hills arranged in the shape of a crude horseshoe, which had its extremities at Sant’ Angelo and Panaccioni and its toe against the lateral road north of Pignataro. Covered with close-growing vineyards and thick patches of scrub oak, and intersected by narrow ravines and sunken lanes, the Sant’ Angelo “Horseshoe” included some of the roughest ground in the Liri Valley.

This unfavourable terrain and the determined resistance of the enemy, who was well-equipped with anti-tank weapons, resulted in frequent loss of contact between armour and infantry (its commitments in the line with the 13th Corps had prevented the Three Rivers Regiment from training with battalions of the 8th Indian Division in the Volturno Valley).113 On several occasions the Canadian armour outdistanced the Punjabi riflemen and had to return to destroy by-passed German sniper positions and machine-gun nests now pinning the infantry to ground. Progress was slow, but the enemy suffered heavy casualties, and many surrendered to our tanks. On the right two squadrons of the Ontarios, supporting the 17th Indian Brigade west of Sant’ Angelo against stem resistance, knocked out a tank, a self-propelled gun and eight anti-tank guns as they methodically cleansed the Horseshoe of the enemy.114 By midday on the 15th the two Indian brigades were firmly on the lateral road, and before dark two companies of the Frontier Force Rifles had worked their way into Pignataro under cover of high explosive and smoke shells fired from Calgary tanks.*

* Contemporary German accounts of the fighting in the 44th Division’s sector on 15 May emphasize (if they do not exaggerate) the strength of the Allied armour. “At, Pignataro alone he had advanced on our positions with 45 tanks; south of Colle d’Alessandro [the toe of the “Horseshoe”] with another 45 tanks, and ... in the area of Battle Group Schulz with 54 tanks. A total of 250-300 tanks were observed along the whole front.”115

The garrison fought back bravely, stubbornly resisting the Pathans house by house and street by street. By midnight, however, the town was reported clear of enemy, and the lateral road from the railway to the Liri was in Allied hands.116 Elements of the 361st Panzer Grenadier Regiment – second of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division’s formations to be rushed into the fray – arrived in the Pignataro area too late to save the town.117

Of the fortifications of the vaunted Gustav Line, only the battered Cassino stronghold now remained in German possession. South of the Liri General Juin’s hill – trained African forces had made sweeping gains through the mountains, and the 2nd Corps was keeping pace in the coastal area. On 13 May the 2nd Moroccan Division had captured the 3000-foot Mount Majo, key to the mountain defences overlooking the Garigliano. Two days later, Algerian troops, striking with amazing speed over the Aurunci Mountains, had entered the Ausonia defile, through which the road passed to Esperia and Pontecorvo.†

† In his Memoirs Kesselring seeks to cover his failure to commit sufficient reserves by blaming the 94th Division for assembling in the coastal area instead of in the Aurunci Mountains as he had ordered. “This meant”, he writes, “that the Alpine troops of the French Expeditionary Force had a clear path.”118

By the night of the 14th the French 1st Motorized Division

had cleared the south bank of the Liri as far west as San Giorgio.119 As the whole German right flank staggered back from these successive blows, Kesselring angrily demanded a clear picture from every sector of his front, declaring it intolerable that troops could “be in fighting contact with the enemy for two days without knowing whom they are fighting.”120 His failure to realize the full measure of the momentum of the Allied offensive is revealed in a directive to his two Armies on the evening of the 15th, ordering stabilization on a new main line of defence from Esperia through Pignataro to Cassino, to permit “the continued defence of the Cassino massif.”121 But by the morning of 16 May 13th Corps forces were already holding the road which such a line would follow, and a further German withdrawal was imperative.

At 5:25 that evening Marshal Kesselring and his Army Commander discussed the situation on the telephone:

Kesselring: ... I consider withdrawal to the Senger position as necessary.

von Vietinghoff: Then it will be necessary to begin the withdrawal north of the Liri; tanks have broken through there.

Kesselring: How far?

von Vietinghoff: To 39 [two miles north-west of Pignataro].

Kesselring: And how is the situation further north?

von Vietinghoff: There were about 100 tanks in Schulz’s area.

Kesselring: Then we have to give up Cassino.

von Vietinghoff: Yes.

Within an hour von Vietinghoff had issued directions for a general withdrawal to the Senger Line.122

The Advance to the Hitler Line, 16–19 May

The success of the 8th Indian Division in breaching the Gustav Line from Sant’ Angelo to the Liri, and the relatively slow progress that had been achieved on the 13th. Corps’ right flank and on the Polish front, presented a situation for which General Leese had his plans ready. He decided to commit his army reserve, and continue the battle on a three-corps front. On the evening of 15 May he directed the 1st Canadian Corps to relieve the Indian Division and maintain the advance in the south half of the valley, and the 13th Corps to put its whole weight into a joint effort with the 2nd Polish Corps to isolate Cassino and Monastery Hill.123 General Burns immediately ordered the 1st Canadian Division forward.

General Vokes had been awaiting these instructions for two days, and he had already arranged with the GOC of the Indian Division, Maj-Gen. Dudley Russell, that the takeover should be made a brigade at a time. During the night 15–16 May Brigadier Spry’s 1st Brigade dug in behind the Indians’ left flank, and early next morning began to advance – The Royal Canadian Regiment next to the Liri, and The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment

(now commanded by Lt-Col. D. C. Cameron) in the vicinity of Pignataro. Both battalions met resistance from troublesome German outposts, and being further slowed down through having to operate off the roads (and thus manhandle their heavy wireless sets, 3-inch mortars and ammunition), gained little ground during the day.124 On the left the RCR, supported by tanks of the 142nd Regiment Royal Armoured Corps (25th Tank Brigade),*

* The 25th Tank Brigade had fought in the Tunisian Campaign, and since that time had been training in North Africa.125

hotly disputed the enemy’s possession of a low hill which overlooked the junction of the Pignataro lateral with the river road and commanded the approaches to the only bridge across the Liri below Pontecorvo. When driven off the feature with heavy losses the Germans employed a favourite trick of raking it with mortar and artillery fire. The assaulting RCR company was forced to withdraw, and nightfall found the battalion with casualties of 20 killed and 36 wounded and still on the wrong side of the empty hill.126 The Hastings, encountering somewhat lighter opposition, by-passed Pignataro, which was still being cleared by the Indians, and reached positions about a mile to the west of the village. The relief of the Indian Division was completed that night, as Brigadier Bernatchez put The West Nova Scotia Regiment and the Carleton and Yorks into the line north of Pignataro, and Vokes took over command of the sector from General Russell. The Canadian GOC learned from General Burns that the Army Commander had expressed disappointment at the 1st Brigade’s lack of progress “in the face of quite light opposition”,127 and he gave orders for a determined advance by both his forward brigades to make contact with the Hitler Line.128

The advance was resumed at dawn on the 17th. On the right the three battalions of the 3rd Brigade, each supported by a squadron of the Three Rivers (the unit allotted from the 25th Tank Brigade could not reach the battle area in time),129 attacked in succession, with the Royal 22e Regiment in the lead, and the West Novas and the Carleton and Yorks following through. They advanced vigorously against moderate rearguard action, for the 361st Grenadier Regiment was under orders to fall back to the Senger Line.†

† The 51st Mountain Corps war diary recorded that the 361st Grenadier Regiment had been “enveloped from both sides by superior enemy forces with tanks; overtaken and finally encircled.”130

Boggy ground and minefields claimed sixteen of the Three Rivers tanks, but throughout the day infantry and armour worked together in perfect harmony. “It was a real thrill to see the battle-wise ‘Van Doos’ march straight forward spread out and half crouching”, wrote the Three Rivers diarist. “They never dug in.” After advancing some three miles, Brigadier Bernatchez did not halt with the coming of darkness, but “contrary to all expectations” of the German defenders131 pushed the Royal 22e through the Carleton and Yorks on the east bank of the Forme d’Aquino, to secure a substantial bridgehead on the far side of the gully.132

For units of the 1st Brigade the fighting on 17 May was very nearly the heaviest of any day in the whole Liri Valley campaign.133 The brigade’s axis lay across more difficult terrain than that of the 3rd Brigade, notably the narrow but steep gully of the Spalla Bassa, which formed a tank obstacle midway between the Pignataro road and the Forme d’Aquino. Well dug in on the wooded ridges, remnants of the 576th Grenadier Regiment, reinforced by the 190th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion,*

* This unit had arrived the previous day. Its parent formation, the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division, took over from the 44th Division command of the sector opposite the 1st Canadian Division at 8:00 a.m. on 16 May.134

fought a skilful delaying action, in which they were strongly backed by shell and mortar fire, and it took the Hastings and Prince Edwards, deprived of the help of their armour, all day to cross the ravine.135 On Lt-Col. Cameron’s left a squadron of the 142nd Regiment RAC, supporting the 48th Highlanders along the river road, was delayed by a minefield at the Spalla Bassa crossing. Before it caught up again with the infantry the squadron was surprised in tall grain by enemy troops whose Faustpatronen accounted for five Churchills.136 In the meantime the Highlanders, fighting forward without armoured support, stormed an enemy 75-mm. position on high ground a mile west of the Spalla Bassa. Gallantly led by its commander, Lieutenant N. A. Ballard (who when his supply of grenades was used up tackled a German officer with his bare fists and forced his surrender), the foremost platoon drove the Germans off the hill, killing or taking prisoner a score of them and capturing three 75-mm. guns and one half-track vehicle. Ballard was awarded an immediate DSO.137

The end of the day’s confused fighting, which had netted the Canadians 200 prisoners, found the 1st Brigade drawn level with the 3rd, overlooking the Forme d’Aquino and within three or four miles of the Hitler Line. An unsuccessful night counter-attack across the Forme against the 48th Highlanders on the Pontecorvo–Pignataro road cost the enemy heavy casualties and two of the 190th Panzer Battalion’s 75-mm. self-propelled guns, which were destroyed by the skill and ingenuity of the anti-tank platoon sergeant,† who fired his six-pounder by the light of mortar flares over his target.138

† This NCO, Sgt. R. J. Shaw, was awarded the MM for his part in the action.

This was the enemy’s last marked reaction before taking up his stand in his prepared Senger defences. While the Forme d’Aquino obstacle allowed the disengagement of forces in front of the Canadian Division, on the north side of the valley Heidrich’s paratroops reluctantly slipped back along the Via Casilina during the night 17–18 May, before the Poles and the 13th Corps could close the gap. Retirement of the 1st Parachute Division had to be personally ordered by Kesselring – “an example”, he points out, “of the drawback of having strong personalities as subordinate commanders.”139 On the morning of the 18th the British 4th Division held the rubble that had been

Cassino town, and the Polish standard flew over the ruins atop Monastery Hill.140 That day the two Canadian brigades pushed forward unopposed another two miles to the fringes of the Hitler Line, while the 4th Field Company bridged the Forme d’Aquino for the passage of armour.141

In spite of the loss of Cassino the enemy’s northern flank was still secured by his retention of Piedimonte, overlooking Highway No. 6 from the lower slopes of Mount Cairo (see Map 15). But the situation on his right was serious. The hasty committal of a regiment*

* The 9th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which moved to Pico from the Fourteenth Army on 17 May.142 Kesselring placed the whole of the 26th Panzer Division under command of the 14th Panzer Corps on the evening of the 18th.143

of the 26th Panzer Division to strengthen the 200th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had failed to halt the astonishing drive of the French spearheads through the Aurunci Mountains. General Augustin Guillaume’s Goumiers – tough North African tribesmen who excelled in hill fighting†

† The Corps Expeditionnaire Francais had about 12,000 of these troops, who were lightly equipped, extremely mobile, and specially trained in mountain tactics. They were organized into three Groups of Tabors (approximately battalions) of Goums (or companies).144

– had taken Esperia on the 17th, and next afternoon Sant’ Oliva, less than four miles south-west of Pontecorvo.145 General Alexander now ordered the Polish Corps to capture Piedimonte at the northern end of the Hitler Line; the French Corps to turn the southern flank by an encircling move from Pico, which they were fast approaching; and the Eighth Army to “use the utmost energy to break through” the defences in the Liri Valley before the Germans had time to settle down in them.146

For a short time on the 18th chances looked bright for a break-through by a quick thrust against the enemy’s disorganized battle groups. Early in the evening armoured and infantry units of the 78th Division, advancing rapidly through the good tank country south of the railway, reached Aquino airfield, on the edge of the main German defences. An attempt to take Aquino village after dark failed. Brigadier Murphy’s armoured brigade had moved up to relieve the 26th Tank Brigade, and in a more deliberate assault next morning by the 36th Brigade, The Ontario Regiment was called on to support the 5th Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), who were attacking on the right. When the sun suddenly dispersed the heavy morning mist, the Canadian tanks found themselves in the open, within point-blank range of the deadly Panther cupolas of the Hitler Line. The three Shermans of a troop which had approached to within 300 yards of Aquino were rapidly knocked out by a single anti-tank gun. The infantry suffered heavily from shelling and mortaring, and were forced to retire. The armour, ordered to hold its ground (the planned attack on the brigade’s left front did not materialize), continued throughout the day to engage all possible targets, protected to some degree from the withering enemy fire by a constant smoke-screen laid down by

artillery and Engineers with the 78th Division. When at dusk they pulled back to a harbour area east of the airport, the Ontarios had lost twelve Shermans to anti-tank guns, and one by a mine; every remaining tank of the two leading squadrons had received at least one direct hit by high explosive.147

In compliance with General Alexander’s urging on the 18th the Army Commander had ordered the Canadian Corps to maintain pressure, and to have the 5th Armoured Division ready to pass through should the 13th Corps succeed in breaching the Hitler Line.148 Late that night General Vokes directed the 3rd Brigade to advance next morning against objectives on the Aquino–Pontecorvo road, behind the main German defences. At 6:30 a.m. the Royal 22e and the Carleton and Yorks attacked with the support of the 51st Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment. Unfortunately much of the artillery originally assigned for the Canadian attack had been switched to support the 78th Division’s assault on Aquino.149 Deciding that insufficient fire remained to cover the advance of two battalions, Brigadier Bernatchez halted the Carleton and Yorks 800 yards short of the Hitler Line and sent the Royal 22e on alone. Lt-Col. Allard’s leading companies were now about 2000 yards south of Aquino, and midway between the Forme and the lateral road.150

At first the thick patches of stunted oak trees – from five to ten feet high hid them from the enemy’s view, but as they emerged into the open fields they were caught in the relentless fire of machine-guns. A German 88 in a forward position knocked out several of the supporting tanks. During the morning one company worked its way to within 50 yards of the barbed wire, where it came under heavy mortar fire. Greatly increased artillery concentrations were needed if the attack was to succeed; but these were not immediately available because of the priority being given to the 13th Corps’ effort. At two o’clock Colonel Allard received orders from the Brigadier to withdraw his battalion. It had then suffered 57 casualties.151

Preliminaries to Operation “Chesterfield”

It was now apparent to Leese that the heavy fortifications of the Hitler Line could be overcome only by a major assault, substantially mounted and carefully coordinated. On the morning of 20 May he issued orders for the Canadian Corps to attack and break the Line between Pontecorvo and its junction with the Forme d’Aquino. The 13th Corps would maintain pressure at Aquino,*

* The effect of giving the 13th Corps this relatively inactive role on the right flank is discussed on page 452. General Mark Clark, who had urged that both Allied armies should attack with the maximum effort at the same time, was extremely critical of the fact that the Eighth Army’s assault of the Hitler Line was made with only one division.152

and concentrate forward, ready to advance on the

Canadians’ right once the break-through had been achieved.153 Allowing 48 hours for reconnaissance and regrouping, the Canadian attack was tentatively timed to begin on the night of 21–22 May, or early next morning, matching a simultaneous breakout which General Alexander had ordered to be made from the Anzio bridgehead.154 In an early morning instruction Burns gave his 1st Division the task of breaching the Hitler Line; the 5th Canadian Armoured Division would be ready to support the infantry, and to exploit their success by seizing crossings over the Melfa and advancing towards Ceprano.155

In a careful study of the problem assigned to him General Vokes had already selected a lane of attack about 2000 yards wide, with the right resting on the Forme d’Aquino. The ground in this sector provided a better approach for armour than in the vicinity of Pontecorvo, a factor which the Divisional Commander considered outweighed the disadvantage of being enfiladed from Aquino, on the immediate right of the proposed avenue of assault.156 The 1st Division’s blow would be delivered in two phases, designed to breach the defences and gain as successive objectives the line of the Pontecorvo–Aquino lateral, and the high ground 1500 yards to the west, along which ran a second lateral road, joining Pontecorvo to Highway No. 6. This operation would make a hole in the Hitler Line wide enough and deep enough for the 5th Armoured Division to pass through.157

To effect such a breach the GOC originally intended to launch the assault on a two-battalion front, employing the 2nd Brigade under cover of an intensive barrage and supported by two regiments of tanks, while the 1st and 3rd Brigades made feint attacks on the left.158 This plan was accepted at a Corps conference on the 20th, but met criticism from the Army Commander, who felt that an assault on a frontage of this width, against such strong defences, required two infantry brigades forward, fighting on a three- or four-battalion front.159 Accordingly the 3rd Brigade, less the Royal 22e Regiment, was included in the attacking force. There would thus be ranged across the Corps front three infantry battalions with supporting armour: Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry on the right, with one squadron of the North Irish Horse; The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in the centre, with the two remaining North Irish squadrons; and on the left The Carleton and York Regiment of the 3rd Brigade, with two squadrons of the 51st Royal Tank Regiment. The Loyal Edmonton Regiment and the remaining squadrons of the 51st would form the 2nd Brigade’s reserve; Brigadier Bernatchez would have the West Nova Scotias in support. H Hour was set at 6:00 a.m. on 23 May.160

The next three days were busy with preparations for “Chesterfield” – the somewhat ironical code name given to the Canadian Corps operation. While infantry and engineer patrols probed cautiously into the fringe of the German defences, lifting mines and reconnoitring tank routes, the narrow valley