Chapter 15: The Advance to Florence, June–August 1944

Enemy Intentions After the Fall of Rome

There was now a great opportunity for an aggressive exploitation northward from Rome; the two German armies were divided and had no communication with each other, and there was considerable disorganization and confusion both among their forward and rear elements. Bold enveloping movements against the weak forces of the Fourteenth Army might have paid handsome dividends; but the Allied plan called for an orthodox pursuit.*

* In his post-war comments Kesselring, noting “the remarkable slowness” of the Allied advance, declares that “the enemy behaved very much as I had expected. If on 4 June he had immediately pushed forward on a wide front, sending his tank divisions on ahead along the roads, our Army Group west of the Tiber would have been placed in almost irreparable jeopardy. ...”1

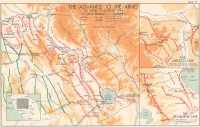

The Eighth Army’s immediate task, as General Alexander had directed before the offensive opened on 11 May, was “to pursue the enemy on the general axis Temi–Perugia”; the Fifth Army was to capture the port of Civitavecchia and the Viterbo airfields2 (see Map 17).

Seizure of the Rome bridges had given the Allies entry to three first class roads to the north. By 6 June two armoured divisions of the 13th Corps were driving up the Tiber valley towards Terni, 50 miles north-east of the capital – the 6th South African along the Via Flaminia (Highway No. 3) on the west bank, and the 6th British up the Via Salario (No. 4), east of the river.3 On the left the Fifth Army advanced with two corps. While the 2nd Corps headed up Highway No, 2 towards Viterbo, 40 miles to the north, armoured combat commands of the 6th Corps swept up the coastal flank, to seize Civitavecchia on 7 June. In spite of German demolitions the port, the largest between Naples and Leghorn, was opened to Allied shipping on 12 June.4 As the retreating German columns streamed up the highways employing any means of transport that would move, the relentless air attacks which had harassed them south of Rome continued to exact a heavy toll. The Tactical Air Force claimed 1698 vehicles and armoured cars destroyed

and 1755 damaged in daylight attacks between 2 and 8 June, while road and rail transport near the sea fell prey to fighters of the Coastal Air Force. Even the darkness did not allow the hapless enemy to move unmolested. Night after night Baltimores and Bostons harried the traffic flowing from the battle area, and farther afield Wellingtons and heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force struck effectively at bridges and road junctions along the escape routes to the north.5 There was virtually no opposition from the Luftwaffe; on many days scarcely one enemy aircraft ventured into the Italian skies.6

For the first time since the beginning of the Italian campaign the terrain favoured the Allies. Northward from Rome, as the Italian leg broadens at the calf, the Apennines, which in the region of the Winter Line cover two thirds of the peninsula, narrow away towards the Adriatic, leaving in the latitude of Lake Trasimene a series of rolling plains which stretch 100 miles across Tuscany to the Tyrrenhian Sea (see map at back end-paper). Between Lake Trasimene and Florence the country becomes more rugged again. The main mountain backbone swings back towards the west, to form north of the River Arno a solid barrier spanning the peninsula from coast to coast, and blocking all approaches to the Lombard Plain except by the narrow coastal strip south of Rimini. Both topography and the season of the year were now against Kesselring. On these wide plains and with winter no longer on his side there seemed little likelihood that his armies could make any protracted defence until they reached the line of the Arno and the Northern Apennines.

The nineteen divisions with which the C-in-C South-West had attempted to bar the road to Rome were now battered and disorganized, and in no condition to offer any immediate effective resistance. On the day after the city’s fall he told Berlin, “By 2 June the divisions had reported a total of 38,024 dead, wounded and missing. The figure keeps mounting. ...”7 A preliminary estimate showed the fighting strength of his formations, both in personnel and guns, to be only from ten to fifty per cent* of that with which they had entered the battle.8 Within a week disquieting information in greater detail reached Kesselring. Abbreviated “condition reports” showed that on 10 June no division of the 14th and 76th Panzer Corps could put into action more than 2500 men; the Hermann Goring Panzer Division numbered only 811, and the 1st Parachute Division 902 all ranks. Heavy deficiencies in guns and tanks completed the general picture of ruination.9

Characteristically Kesselring acted promptly to restore his broken front. His first concern was to reinforce the Fourteenth Army, which in the open

* Among the hardest hit were the 94th and 3 62nd Infantry Divisions (reduced to 10 per cent of their normal strength), the 1st Parachute, the 44th Infantry and the 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions (15 per cent), and the 26th Panzer and the 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions (20 per cent).

country west of the Tiber was in greater danger than von Vietinghoff’ s forces nearer the Apennines. He replaced von Mackensen with General of Panzer Troops Lemelsen (who had temporarily commanded the Tenth Army at the end of 1943 before taking over the First Army in the Bordeaux area), giving him three fresh, if inexperienced, formations – the 356th Infantry Division and the 162nd (Turcoman) Division from Armee Gruppe von Zangen, and the 20th Luftwaffe Field Division from Denmark.10 He ordered the new Army Commander to send back three hard-hit formations from the front “to the Gothic Line*

* Originally called by the Germans the “Apennine position”, the Pisa-Rimini line was given the more romantic designation, the “Gothic Line”, in April 1944.11 On 16 June it was renamed the “Green Line”.12

for rejuvenation, where at the same time they will act as security garrisons.13 To add further strength to the German right flank, the 14th Panzer Corps, with its three motorized divisions (the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier and the 26th Panzer Divisions), moved west of the Tiber to join the 1st Parachute Corps in the Fourteenth Army. Its place was taken by the 76th Panzer Corps, which assumed responsibility for the Tenth Army’s right flank as the inter-army boundary was shifted westward.14

At first the German leaders saw little prospect of halting the Allied advance south of the Pisa–Rimini line. On 8 June the Deputy Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, General Walter Warlimont, who had been sent to Kesselring’s headquarters to get first-hand information, reported to General Jodl that “if the worst should happen and despite the greatest efforts the enemy cannot be brought to a halt previously, it will be necessary to fall back to the Gothic position in about three weeks.”15 To Kesselring “the worst” would be an Allied encircling landing; spared this, he hoped “to lengthen this time considerably by fighting a delaying action with all means available.”16

Next day the German C-in-C issued a comprehensive operation order for a gradual fighting withdrawal to the Gothic Line. His instructions followed the pattern of those given after the loss of the Hitler Line. Every effort was to be made to hold the Dora position, a line which crossed the peninsula about 40 miles north of Rome, passing south of Lake Bolsena through Rieti and Aquila to merge into the Foro defences on the Adriatic coast. From this stand Army Group “C” would only withdraw northward “if forced to do so by the enemy”, and then only over several lines of resistance, each to be stubbornly defended, and in bounds that would “not exceed 15 km. at any one time.”17

The terms of this order were received with misgivings and distrust by Hitler, who suspected his Army Group Commander of wanting to fall back to the Gothic Line without offering serious resistance. A teletype message

from Kesselring to the High Command on 10 June reinforced these doubts, for the Field Marshal, while reaffirming “his intention of defending Italy as far south of the Apennines as possible”, declared that “his second imperative duty is to prevent the destruction of his Armies before they reach the Gothic Line and to let them reach the new line in battle-worthy condition.”18 But Kesselring failed to make his point, and next day his war diary recorded: “Order from the Fuhrer: Delaying resistance must not be continued [indefinitely] till the Apennines are reached. After reorganization of the formations the Army Group will resume defence operations*

* The distinction between “delaying resistance” and “defence” should be noted. The former (hinhaltender Widerstand) meant a gradual yielding under moderate pressure; the latter (Verteidigung), to hold to the last.

as far south of the Apennines as possible.”19 In vain Kesselring protested to Jodl the hopelessness of attempting to defend unprepared positions, emphasizing the continued threat of an encirclement of the Tenth Army, and the danger that too slow a withdrawal to the Gothic Line might not only weaken his forces below the point where they could form an adequate garrison, but might allow the Allies to arrive there simultaneously with German troops, and so achieve an immediate breakthrough.20 Hitler was adamant. As a staff officer of Army Group “C” observed,21 “When the Fuhrer says ‘Thus it shall be done’, that is the way it will have to be done.”†

† A short time later, however, Kesselring, as told in his Memoirs, won a concession from the Fuhrer. On 3 July he flew to Hitler’s headquarters and successfully urged that he be given a free hand in Italy, guaranteeing “to delay the Allied advance appreciably, to halt it at latest in the Apennines.”22

On 14 June (by which date Allied forces were 70 miles north of Rome)23 the C-in-C issued a sharply worded “Army Group Order for the Transition to the Defence”.24 The Gothic Line was to be built up sufficiently to resist any large-scale Allied attempt to break through to the plains of the River Po. To gain time for these preparations the Army Group would “stand and defend the Albert–Frieda Line.” This position (in Allied records the Trasimene Line) crossed the peninsula from Grosseto, on the Tyrrenhian flank, to Porto Civitanova, 25 miles down the Adriatic coast from Ancona, passing around the southern shore of Lake Trasimene. “Every officer and man must know”, insisted Kesselring, “that upon reaching this line the delaying tactics will come to an end and the enemy advance and break-through must be stopped.”25 The Commander of the Fourteenth Army was one of the first to find that Kesselring meant business. On 15 June he was sternly reprimanded by the C-in-C for having retreated 20 kilometres in a single day. “Lemelsen was made very unhappy by my words”, Kesselring told von Vietinghoff later, “but after all it must be possible to use strong language at times; we cannot afford to go back 20-30 km. in one day.”26

ANVIL is Given Priority

Allied progress in the initial stages of the pursuit was so satisfactory that on 7 June General Alexander was able to set new and more distant objectives for his forces. He ordered the Eighth Army to advance with all possible speed to the general area of Florence–Bibbiena–Arezzo in the region of the middle and upper Arno, and the Fifth Army to occupy the triangle formed by Pisa, Lucca and Pistoia at the northern limit of the Tuscan plains. He authorized Generals Clark and Leese “to take extreme risks to secure the[se] vital strategic areas” before the enemy could reorganize or be reinforced.27 In order to save the resources in transportation and bridging material which would be required for an advance over the difficult terrain of the eastern flank, the 5th Corps was directed not to follow up the enemy on its front. Should the general advance of the Eighth Army fail to force the Germans to abandon Ancona, Alexander intended to take the port by attacking from the west with the Polish Corps.28

To carry out these new instructions both Armies reshuffled and augmented their pursuit forces. On the Fifth Army’s right the French Expeditionary Corps relieved the 2nd Corps, while the 4th Corps took over the coastal sector from the 6th Corps, which now withdrew from the Italian campaign.29 The Eighth Army’s drive developed into an advance by two corps; on 9 June General McCreery’s 10th Corps, which had been fighting through the mountainous region east of Rome, assumed the 13th Corps’ responsibilities on the left bank of the Tiber, leaving General Kirkman free to concentrate on the push to Arezzo.30 On the same day troops of the 5th Corps entered Orsogna, as the

enemy began relinquishing his long tenure of the Adriatic flank.31

German attempts to hold at the Dora Line* produced the first serious fighting north of Rome,

* Not to be confused with the alternative name given to the Hitler Line.

but by 14 June the 13th Corps had broken past Lake Bolsena to capture Orvieto, and the 10th Corps was at the gates of Temi. On that day Alexander signalled General Wilson that since the fall of Rome his armies had advanced an average of seven miles a day, and were now nearly half way to Florence and Leghorn – “an extremely satisfactory situation which we must take full advantage of by speeding up the tempo still higher.”32 The Allied pressure continued. The Fifth Army captured Grosseto on the 17th; and the reduction of the island of Elba, which fell on 19 June to an assault mounted from Corsica by French ground forces with British naval and American air support, compelled the enemy to pull back still farther on his coastal flank.33 The 13th British Corps reached the southern shore of Lake Trasimene on the 19th, and next day the 10th Corps

entered Perugia. In the Adriatic sector the 2nd Polish Corps had relieved the 5th Corps and was midway between Pescara and Ancona, its progress impeded by bad weather and extensive demolitions.34 Thus by 20 June the momentum of the main attack had carried General Alexander’s forces up to the Albert–Frieda Line.35

While the Allied Armies in Italy were thus achieving satisfactory tactical successes, in the wider field of strategy the Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean and his Commander-in-Chief were fighting a losing battle to retain for the Italian campaign the overriding priority in Mediterranean operations which it had been given at the end of February. When the Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed in April to the cancellation of Operation ANVIL, so as not to interfere with an all-out offensive in Italy, they had directed General Wilson to make plans for the “best possible use of the amphibious lift remaining to you either in support of operations in Italy, or in order to take advantage of opportunities arising in the south of France or elsewhere. ...”36 Accordingly on 22 May Wilson warned General Alexander that he intended to mount an amphibious operation not later than mid-September, either in close support of the advance up the peninsula, or as an assault outside the Italian theatre. He gave Alexander a tentative schedule of dates for the release to AFHQ of the necessary formations for this undertaking.37 For the next six weeks, while the Combined Chiefs strove to reconcile British and American views on ANVIL, the C-in-C had to carry on without knowing whether he was to lose four French and three American divisions. “This uncertainty”, he writes, “was a very great handicap to our planning, and its psychological effect on the troops expecting to be withdrawn, especially the French, was undoubtedly serious.”38

In an appreciation to General Wilson on 7 June Alexander pointed out two alternative courses that he might take. After breaking the Pisa–Rimini line, he could either bring his offensive to a halt and so free resources for operations elsewhere, or if permitted to retain all the forces which he then had in Italy, he could carry the offensive into the Po Valley and form there a base for an advance into either France or Austria.39 He warmly recommended the second as the course likely to achieve his object of completing the destruction of the German armed forces in Italy and rendering the greatest possible assistance to the invasion of North-West Europe. “I have now two highly organised and skilful Armies, capable of carrying out large scale attacks and mobile operations in the closest cooperation ...”, he wrote. “Neither the Apennines nor even the Alps should prove a serious obstacle to their enthusiasm and skill.”40

On 14 June the Combined Chiefs of Staff notified General Wilson of their decision that an amphibious operation on the scale planned for ANVIL would be launched – either against Southern France, Western France or at

the head of the Adriatic;41 General Alexander was immediately instructed to begin withdrawing from action the 6th US Corps Headquarters and the divisions already earmarked for inclusion in the Seventh Army.42 Wilson strongly urged adoption of the third alternative proposed by the Combined Chiefs. He contended that an advance across the Po Valley and through the Ljubljana Gap into Austria, with the assistance of an amphibious operation against Trieste, would make the best contribution to the success of General Eisenhower’s operations in the west.43 The claims of ANVIL, however, were not to be denied. General Marshall had already pointed out to General Wilson that the capture of Marseilles would provide an additional major port through which some 40 or 50 divisions from the United States, all of them ready for action, might be introduced into France.44 General Eisenhower was firm in his desire for the operation against Southern France, and on 2 July Wilson received a directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff that the assault was to be made*

* Mr. Churchill, who was against any reduction in Alexander’s armies except as direct reinforcements to OVERLORD, opposed ANVIL to within a few days of its mounting. On 28 June he urged that it be abandoned in order to “do justice to the great opportunities of the Mediterranean commanders”;45 and on 4 August, declaring that the enemy on the Riviera coast was much stronger than the Allies could hope to be, he recommended that the ANVIL forces be sent around to the west coast of France to join the OVERLORD forces in the St. Nazaire region.46

on 15 August.47 The operation was to be given overriding priority over the battle in Italy to the extent of a build-up of ten divisions in the south of France. General Alexander’s task was still the destruction of the German forces in Italy; and to this end he was directed “to advance over the Apennines and close to the line of the River Po, securing the area Ravenna–Bologna–Modena to the coast north of Leghorn.” Thereafter, should the situation permit, he was to cross the Po to the line Padua–Verona–Brescia at the northern edge of the Plain. The Combined Chiefs hoped that these advances, together with the exploitation of the ANVIL assault, would cause the enemy to withdraw from north-west Italy, and thus render unnecessary any further offensive in that direction.48 To the C-in-C, however, any large-scale penetration into the Po Valley before winter set in now appeared most unlikely. He therefore gave permission for the bombing of the Po bridges, which he had hitherto spared because of the major engineering problems that their rebuilding would have involved. On 12 July the Tactical Air Force went to work, and within 72 hours knocked out all the 23 rail and road bridges†

† Subsequent action by the Air Forces kept the Germans from restoring these important links in their communications. At a conference on 30 August the Tenth Army’s Chief Engineer Officer reported: “At the moment all bridges across the Po are destroyed.”49

in use over the river.50

“Whatever value the invasion of Southern France may have had as a contribution to operations in North-western Europe”, Alexander was later to declare, “its effect on the Italian campaign was disastrous. The Allied Armies

in full pursuit of a beaten enemy were called off from the chase, Kesselring was given a breathing space to reorganize his scattered forces and I was left with insufficient strength to break through the barrier of the Apennines.”51 Almost a full year after the landings in Sicily the Italian campaign had reached its climax. “From the beginning”, observed the C-in-C, “both Germans and Allies regarded Italy as a secondary theatre and looked for the main decision to be given on either the Eastern or Western front. “52 Henceforth Allied commanders in Italy were to feel increasingly the effects of this subordination. But the main intention, to bring to battle the maximum number of German troops, never varied, and in the ten months of fighting that remained this object was relentlessly pursued.

Canadian Tanks at the Trasimene Line, 21-28 June

Canadian participation in the initial stages of the pursuit which followed the capture of Rome was limited to the operations of one armoured unit. When General Burns’ 1st Corps was withdrawn into reserve on 6 June, the Three Rivers Regiment was supporting the leading brigade of the 8th Indian Division,*

* The Indian Division was then under command of the 13th Corps, but next day came under the 10th Corps as General McCreery’s forces took up the pursuit.53

which it had joined two days before on the Frosinone–Subiaco road, about four miles north of Alatri.54 During the next five days the Indians carried out a steady but unspectacular advance along the rocky western slopes of the Simbruini Mountains. They passed through Guarcino on the 4th and Subiaco on the 6th, and on the evening of the 9th reached Arsoli at the junction with the Via Valeria (Highway No. 5). The contribution of the Canadian armour at this stage was minor; most of the time the tanks trailed far behind the infantry, being held up by demolitions and mines on the narrow mountain roads.55 On 9 June, as a regrouping of the Eighth Army placed all formations west of the Tiber under the 13th Corps, the Three Rivers Regiment left the 8th Indian Division and rejoined the rest of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade, which was still at Aquino and now under General Kirkman’s command. Three days later the brigade (which General Leese described to Brigadier Murphy on 22 June as “the most experienced armoured brigade in Italy and therefore in great demand”)56 began concentrating with the 4th Division fifteen miles north of Rome, and by the 18th both formations had moved up to the Viterbo area for a very brief period of infantry-tank training.57 While there they formed the reserve to the 13th Corps, which was carrying the pursuit with the 78th Infantry Division and the 6th South African Armoured Division.58

By the time the Eighth Army reached the Trasimene Line the advance of its two corps against Arezzo was developing on two independent axes, dictated by the general topography and the limitations of the road system. The 13th Corps was allotted Highway No. 71, which skirted the western shore of Lake Trasimene and followed the east side of the broad Val di Chiana to Arezzo. Fifteen miles east of the lake the 10th Corps was assigned a secondary road running northward from Perugia along the Tiber.59 General Kirkman’s advance would thus take him through the gap between Lake Trasimene and the smaller Lake Chiusi and Lake Montepulciano, which lie five miles to the west. This defile is covered by a belt of low, rolling hills rising about 300 feet above the surrounding country and extending a dozen miles up the west side of Lake Trasimene. It was an area favourable to defending troops, who could find good observation and cover from view in the scattered villages and farms which surmounted the successive ridges and hilltops, and additional concealment in the woods and in the standing crops which in midsummer clothed the intensively cultivated slopes.

Three days of heavy rain which began on 17 June had slowed the Allied advance and given the Germans time to prepare hurried defence positions along the line selected by Kesselring for a delaying action. The sector of this line opposite the 13th Corps was anchored in the east at Lake Trasimene, and in the west on a high ridge extending north-west from the town of Chiusi – the old Etruscan Clusium. The whole position was about two miles in depth, and was based upon a series of dug-in strongpoints along the Pescia River, a narrow stream flowing into Lake Trasimene with banks steep enough to make it an effective tank obstacle. About half a mile south of the Pescia an almost continuous line of slit-trenches and machine-gun posts linked the hamlets of Pescia, Case Ranciano, Badia and Lopi on the crests of the ridges, and in front of these a forward line ran westward from Carraia on the Trasimene shore through Sanfatucchio and Vaiano to Lake Chiusi.60 The German forces holding these positions formed the right wing of the 76th Corps on von Vietinghoff’ s extreme right flank. In the eastern half of the five-mile gap between the lakes was the 334th Infantry Division, reinforced to four regiments, while on its right, from Vaiano to Lake Chiusi, was Heidrich’s 1st Parachute Division, still fighting with its customary ferocity. The Hermann Goring Panzer Division held Chiusi, and farther west, on the other side of the inter-army boundary, the recently committed 356th Infantry Division*

* These formations had all received reinforcements since the Rome battle. A Tenth Army return for 2 July gave the following “fighting strengths”: 334th Division, 1750; 1st Parachute Division, 1530; and Hermann Goring Division, 3380.61 In a Fourteenth Army return the 356th Division reported a strength of 3927.62

covered the road leading northward to Montepulciano.63

On 21 June, when it was apparent that a full-scale attack would be needed to dislodge the enemy, Kirkman decided to commit his reserves. He ordered the 4th Division (commanded by Maj-Gen. A. D. Ward) and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade to move up on the left of the 78th Division and take over the centre of the Corps front opposite Vaiano.64 The first of the Canadian armoured units to go into action was The Ontario Regiment, placed temporarily under command of the 78th Division while the 4th Division was completing its take over. Early on the 21st two squadrons supported two battalions of the 38th (Irish) Brigade in an attack on the enemy’s foremost positions between Sanfatucchio and the lake. By midday the village had been cleared after extremely bitter hand-to-hand fighting. During the evening Pucciarelli, a mile to the north, was captured by the 6th Inniskillings after “A” Squadron’s tanks had rushed the village. German counter-attacks on the 22nd to regain the eastern end of their forward line were beaten off, and our infantry and tanks spent the day clearing the low ridge between the two villages.65

By the evening of the 23rd the 4th Division had taken over the 78th Division’s left flank in the sector between Vaiano and Chiusi, and arrangements were completed for an attack by both divisions next day. At dawn the 78th Division attacked astride Highway No. 71 with two brigades. To the left of the road two battalions of the Irish Brigade advanced from Pucciarelli, with tanks of The Ontario Regiment protecting both flanks. As the infantry approached Pescia, a small group of German tanks launched a counter-attack from Case Ranciano, a handful of farmhouses off to the left flank. Prompt action by the Ontarios’ “A” Squadron destroyed two Panthers and damaged a third, forcing the remainder to withdraw. Aided by “C” Squadron The Royal Irish Fusiliers took Pescia, and moved on to clear Case Ranciano. By evening the 78th Division had crossed the Pescia River on both sides of the highway, although partial demolition of the road bridge kept armour on the south bank. The 334th Infantry Division had resisted stubbornly across its whole front; a high proportion of the 200 prisoners captured had been wounded.66 The Ontarios’ bag of five German tanks brought a personal message of congratulations from the Army Commander to the CO, Lt-Col. R. L. Purves.67 In its four days of fighting the regiment had suffered casualties of seven killed and 18 wounded.

The attack by the 4th Division in the centre of the 13th Corps front progressed more slowly. A battalion of the 28th Brigade advancing northwards from Villa Strada found members of the 1st Parachute Division firmly in possession of Vaiano.68 But now faulty cooperation between our armour and infantry showed the effects of lack of joint training.* When the infantry

* After training briefly with the 10th Brigade, the Three Rivers Regiment had suddenly taken The Ontario Regiment’s place in support of the 28th Brigade when the Ontarios were transferred to the 78th Division.69

failed to take advantage of the Three Rivers’ covering fire, the Canadian tanks by-passed the village, driving another 1000 yards on to a ridge which marked the brigade objective, only to find that their action exactly suited the tactics of the paratroopers, who from the tall grain pinned down the infantry in the rear with small-arms fire. Throughout the day the Three Rivers remained forward, waging their own battle against the enemy’s strongpoints, and suffering casualties from anti-tank and mortar fire. In the evening they withdrew to consolidate with the British battalions, which had not been able to pass Vaiano. The day closed with a heavy cloud-burst that saturated the ground and slowed tank movement. The crew of a Sherman which bogged down in a muddy gully without infantry protection were captured; these five were the only members of the regiment to be taken prisoner during the Second World War.70

Before daylight on the 25th the paratroopers pulled back from Vaiano, conforming with the 334th Division’s withdrawal across the Pescia River. As the 4th Division’s advance gained momentum the Canadian tanks found manoeuvre over the rain-sodden ground made increasingly difficult by the sharp little hills with their steep terraced sides and the dense curtains of vines strung on wires between sturdy low-growing oak-trees. Of seven tanks lost by the Three Rivers’ “C” Squadron that day, five fell victim to the rough Umbrian terrain as they threw their tracks or became hopelessly bellied down on the rocky terraces.71

By 26 June the 78th Division, after breaking through the right of the Trasimene Line, had been halted between the Pescia and the Castiglione del Lago–Montepulciano lateral road in open country dominated by the enemy’s artillery. The 4th Division now took up the main attack, sending the 10th Brigade along a secondary road which wound into the hills about a mile east of Lake Chiusi. Tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment led the way into Lopi, whose possession the enemy did not dispute, and then supported an attack by the 2nd Battalion, The King’s Regiment (Liverpool) on Gioiella, which was taken after determined resistance by strong paratroop rearguards.72 The loss by the Canadian unit of seven officers and men killed and 19 wounded during the day prompted the regimental diarist to comment, “The Three Rivers Regiment is suffering more casualties than in the Gustav and Hitler shows! And personnel and tank reinforcements are very short, mainly because tank rail-head is about 200 miles back at Cassino, and transporters and road space are very limited.”73

About 1000 yards north of Gioiella a dominating ridge extending westward from a bend in the Pescia River to the village of Casamaggiore formed the rear and strongest part of the German defences on the 4th Division’s front. It took two days of combined effort by four infantry battalions and all three squadrons of the Three Rivers Regiment to rout the, enemy from this

final position.74 “C” Squadron fought a brilliant action on the 28th when, having pushed a mile past Casamaggiore, it seized vital high ground and then for seven hours stood off a series of determined counter-attacks by German armour and infantry, thus enabling the British battalions to close in on their objectives.75 When, early in the engagement, the squadron commander’s was one of four Canadian tanks knocked out in rapid succession, his second-in-command, Captain I. M. Grant, assumed control of the three remaining Shermans and throughout the day directed their operations with great skill and daring. As small groups of paratroopers attempted to infiltrate through the standing crops he left his own tank and for five hours, under continual sniping and mortar fire, sought them out on foot and guided his tanks from one fire position to another to deal with them. This “complete disregard for his personal safety and superb leadership” won Grant the DSO,*

* The only troop commander to survive with Grant, Lieut. F. A. Farrow, won the MC in the same action.76

an honour not often bestowed on a junior officer.77 Largely due to “C” Squadron’s gallant efforts the strength of the German position on the ridge was broken. During the evening “A” Squadron supported the 1st/6th Battalion, The East Surrey Regiment in a successful attack on Casamaggiore. This time tank cooperation with the infantry was good, as “A” Squadron shot them from objective to objective and then covered them into town.”78 Its final action in breaking the Trasimene Line had cost the Three Rivers Regiment eleven killed and 14 wounded. “It was the 12th’s roughest day on record”, wrote the unit diarist, “and everyone felt deeply the loss of such fine men and officers.”79

In the meantime on the Fifth Army’s front the 4th US Corps had been advancing steadily up the relatively lightly defended coastal flank, while on the 13th Corps’ immediate left the Corps Expeditionnaire Français, after being held from 22 to 26 June on a 29-mile front along the Orcia River, had broken through the stubborn resistance of the 4th Parachute and 356th Infantry Divisions.80 “There are no words to express what is going on”, lamented Lemelsen to von Vietinghoff on the morning of the 26th. “He is breaking through on the coast and is extending his gains in the centre. Everything goes wrong. There are no reserves to save the situation.”81 That evening Kesselring acceded to the demands of his Army Commanders and issued orders for a general withdrawal, to be accompanied by bitter rearguard resistance, particularly in the sector between Lake Montepulciano and Castiglione del Lago.82 As we have seen, there was little immediate lessening of resistance opposite the 13th Corps, but during the night of 28–29 June the enemy broke contact and pulled back three or four miles across the entire Corps front.83 German documents reveal that Kesselring’s staff had been indulging in much uneasy speculation regarding the future movements of the 1st Canadian

Corps, which on 24 June was erroneously reported to be in the Terni–Foligno area84 In the momentary lull which followed the 78th Division’s overrunning of the forward Trasimene positions, Tenth Army intelligence staffs waited for the commitment of the Corps (which they believed was being concentrated immediately behind the front) to disclose the centre of gravity of the expected attack.85 “One of these days”, remarked Runkel (Chief of Staff of the 76th Corps) to Wentzell, “the Canadian Corps is going to attack and then our centre will explode.”86 The capture of members of the Three Rivers Regiment on the 24th (see above, p. 468) led to the faulty conclusion that a Canadian armoured division had entered the battle in the Vaiano sector, and for a time the identity of the attacking infantry was in question. “My Intelligence Officer tells me that it is the 1st Canadian Division ...”, Wentzell reported to the Army Group’s Chief of Staff (Lt-Gen. Hans Rottiger). “Personally I believe it is the 4th British Division, but my Intelligence Officer says, ‘Only Canadians attack like that’, and after all the 5th Canadian Armoured Division has been identified.”87 Before the end of June the enemy correctly recognized the 1st Armoured Brigade as the only Canadian troops then opposing him in Italy; but he was still ignorant of the whereabouts of the Canadian Corps.88

The Advance to the Arezzo Line, 29 June–16 July

The continuation of the advance on 29 June reflected changes in the Eighth Army’s plan for the drive on Arezzo and Florence. The 13th Corps was now to have priority in men and resources over the 10th Corps, which had been making little progress in the mountainous region north of Perugia. The tired 78th Division, due for a long rest in the Middle East, began withdrawing from General Kirkman’s right flank; its place was filled by transferring the 6th Armoured Division from General McCreery’s command to lead the 13th Corps’ advance along Highway No. 71, and by increasing the front of the 4th Division, which now brought the 12th Brigade up on the left of the 10th Brigade, supporting it with the 14th Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Calgary Regiment).89

Units of the 1st Parachute Division had halted about four miles northwest of Casamaggiore on a low ridge connecting the villages of Valiano and Petrignano, and as the leading troops of the two British brigades approached at dusk on the 29th, they were greeted with heavy artillery and mortar fire. Next day squadrons of The Calgary Regiment (now commanded by Lt-Col. C. A. Richardson) supported a two-pronged attack by the 12th Brigade on Valiano, while a battalion of the 10th Brigade, assisted by the Three Rivers, advanced on Petrignano, two miles to the east. Both attacks

met trouble. Mutually supporting fire from the defenders of each village harassed the infantry from both flanks, and our armour was hotly engaged by German self-propelled guns and tanks along the ridge. Lack of coordination kept the Canadian regiments from knowing the exact positions of each other’s forward tanks, with the result that neither could press the attack, and no artillery fire was brought down on the enemy armour, which did some damaging shooting with relative impunity.90 At nightfall the Germans, under cover of a sharp counter-attack in front of Petrignano, withdrew from both villages. “Superficially the day was not a marked success,” recorded the Calgary diarist, “but we had inflicted casualties and seen the enemy once more retreat.”91

The sight of the enemy in retreat became more familiar during the following week, as General Herr’ s divisions withdrew northward over level country little suited to effective delaying action. But as usual the German engineers missed no opportunities, and as the 4th Division pushed forward along the broad Val di Chiana, its advanced guard was checked by mines and demolitions at the numerous water-crossings and by occasional shelling and sniping by small rear parties. Smart work by the Calgaries’ reconnaissance troop in routing a demolition party and seizing a bridge over the main waterway – the Canale Maestro della Chiana – enabled units of the 12th Brigade to occupy the town of Foiano di Chiana by midday on 2 July.92 As the advance continued along the west side of the canal, the 28th Brigade, supported by The Ontario Regiment, replaced the 10th Brigade and the Three Rivers on the divisional right flank. It was by no means ideal country for the armour; for although the level vineyards and the narrow grain plots between provided good tank going, low-strung grapevines and tall-growing maize crops seriously restricted the field of vision of the crew commander and his driver. More than once in such conditions a hidden enemy anti-tank gun caught an advancing Sherman unawares.93

On 4 July both brigades crossed the Arezzo–Siena highway east of Monte San Savino, and next day stiffening resistance along the rising ground indicated that Kesselring had decided to make another stand.94 By the 6th the Allied advance had been checked all across the peninsula; it was apparent that the important rail and road centre of Arezzo and the major ports of Leghorn and Ancona on either coast were not to be taken without a struggle. In the 13th Corps’ sector what we came to call the Arezzo Line ran about seven miles south of the main road from Arezzo to Florence (Highway No. 69). With their customary tactical sagacity the Germans had selected positions of great natural strength along the height of land between the valleys of the Arno and the Chiana. Steep hillsides covered with rocky outcroppings and deep gullies clothed with oak thickets made movement off the roads by infantry extraordinarily arduous and by tanks virtually impossible – and the enemy controlled all roads.

From the hilltop town of San Pancrazio General Heidrich dominated the Monte San Savino–Florence road, which provided the 4th Division’s main avenue of advance, while his hold on the equally inaccessible village of Civitella, four miles to the east, barred the only other passage across the mountain ridge in the divisional sector.95 On 6 July two battalions of the 12th Brigade made a vain and costly attempt to storm the olive-terraced slopes below San Pancrazio while Calgary tanks poured a heavy volume of high explosive into the enemy’s positions on the heights.96 On the brigade’s right flank the Calgaries’ “B” Squadron had been halted two days before about a mile south of Civitella by “rocks, gorges, precipitous hills, sniping, mortaring and the exhaustion of their accompanying infantry.” The enemy was holding a height Point 543 – so hemmed in by other hills that the armour could give little help to the infantry, and attacks by the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers on 4 and 5 July were thrown back with heavy losses.97 On the afternoon of the 5th a battalion of the 28th Brigade supported by an Ontario squadron drove the enemy from Tuori, a mean hamlet two miles east of Civitella, high above the Chiana Valley.98

Having failed to take the main San Pancrazio–Civitella ridge by frontal assault, the commander of the 4th Division made another attempt to break into the valley of the middle Arno by attacking through the somewhat less mountainous country on the right flank. Late on the 6th the 2nd Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry of the 28th Brigade, striking into the hills behind Tuori under covering fire from Ontario tanks, gained two stubbornly held heights north-east of Civitella – Points 535 and 484.99 But the divisional intention for the 10th Brigade and the Three Rivers to exploit towards Highway No. 69 three miles beyond was frustrated by strong German counter-attacks on both positions during the next three days.100 On Kirkman’s right flank the efforts of the 6th Armoured Division to capture Mount Lignano, which commanded the southern approach to Arezzo, had been equally unfruitful. There followed a week’s deadlock, during which action along the Corps front was limited to patrolling and small-scale skirmishing. The respite gave the battle-weary British and Canadian troops an opportunity for 48 hours in Monte San Savino, which was quickly organized as an impromptu rest and recreation centre.101

The final stage in the struggle for Arezzo began in the early hours of 15 July as the 1st Guards Brigade of the 6th Armoured Division struck at the northern end of the Chiana Valley, while east of Highway No. 71 the 2nd New Zealand Division, brought forward from the Liri Valley to reinforce the 13th Corps, stormed Mount Lignano. West of the Chiana Canal the 4th Division fired all available small arms and mortars in support, an effort to which the tank guns of the Three Rivers Regiment contributed by engaging targets north of Tuori.102 The Guards’ attack was stoutly resisted by the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, but the New Zealanders’ early capture of

their objective gave them commanding observation of Arezzo and the German gun areas to the north. With Mount Lignano in our hands, Kesselring accepted the loss of the city, and gave permission for the 76th Corps to withdraw.103 The armoured division entered Arezzo on the morning of the 16th, and by evening had crossed the Arno four miles to the north-west.104 The next few days saw the enemy once more withdrawing across the entire Allied front. On the 17th the United States 4th Corps reached the Arno east of Pisa, Ancona fell to the Poles on the 18th, and next morning the Americans entered Leghorn.105

The Pursuit to the Arno, 16 July–5 August

The prolonged battle for Arezzo had given Kesselring’s labour battalions ten extra days in which to complete the defences of the Gothic Line; but the Eighth Army now held an administrative base for its planned attack on those positions. There remained, however, a further three weeks of hard fighting before Florence was secured as an operational base from which such an offensive might be launched.

The 13th Corps’ advance on Florence began on a front of three divisions. While the British 6th Armoured Division thrust north-westward down the Arno valley, and west of the Chianti Mountains the 6th South African Armoured Division drove northward on the Corps’ left flank, the 4th Division kept contact between them, using Highway No. 69 as its main axis.106 On the morning of 16 July, as the fall of Arezzo became imminent, all three of General Ward’s brigades began moving forward with their Canadian armoured regiments in support. On the left the 28th Brigade and The Ontario Regiment widened the divisional front by five miles when they relieved a brigade of the South African Division.107 The enemy had pulled back from the San Pancrazio–Civitella heights, and as the brigades on the right closed up to the Arezzo–Florence highway they met only the familiar opposition of mined roads and demolished bridges while undergoing moderate shelling and mortaring. Early on the 17th the Three Rivers received a royal welcome from the local townspeople as they rolled through Pergine, a mile south of the highway, and by evening the accompanying infantry of the 10th Brigade had cleared La Querce, near the junction with the road from Monte San Savino.108 Four miles down this road infantry of the 12th Brigade, having moved on from “the pile of rubble and crowd of doleful peasants that once comprised the community of San Pancrazio”,109 were in Capannole, which the Calgaries’ reconnaissance troop had entered unopposed the previous evening. Three miles to the west the 28th Brigade had taken Mercatale, and as the two flanking formations converged towards Montevarchi – a prosperous market town on the Arno twenty miles west of Arezzo – the 12th Brigade

was squeezed out and passed into reserve.110 A battalion of the 10th Brigade supported by Three Rivers tanks entered Montevarchi on the afternoon of the 18th, and by midnight had cleared the town of a considerable number of snipers.111

It was at Montevarchi that the Three Rivers Regiment encountered its first band of Partisans – tough, bearded men of many nationalities, whose fierce appearance explained the reluctance of the individual German to stir far from his fellows at night, or even by day. The unit diarist described them as a motley crowd, “dressed in odds and bits of every conceivable uniform from the German’s grey-green to our own drab khaki. For weapons, they must have toured the arms factories of the world ... and from their persons hung a good supply of hand grenades, all different kinds.112 During the advance through Tuscany these rough guerrillas had frequently aided the 4th Division by disclosing details of enemy strengths and dispositions and the location of minefields, and on more than one occasion our artillery was able to pin-point hostile batteries as a result of information brought back by a Partisan patrol which had penetrated the German lines.113

Resistance now stiffened sharply. West of Montevarchi a regiment of the Hermann Goring Panzer Division*

* During the last two weeks in July the Hermann Goring Division, which had been in action on the 76th Corps’ right wing, was transferred to the Russian front. Its 2nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, placed temporarily under the command of the relieving 715th Infantry Division, was the last of its formations to leave Italy.114

was holding a rocky ridge which overlooked both Highway No. 69 and the lateral road leading westward to Poggibonsi (on the main Siena–Florence highway). The feature formed part of one of a series of delaying positions which Kesselring had ordered “must be held to the last” in order to gain more time for the preparation of the Gothic Line.115 It was shown on German maps alternatively as the “Irmgard”116 or “Fritz” Line.117 From Ricasoli, a mountain village about a mile west of Highway No. 69, the Hermann Görings beat off an attack by the Ontarios and the 2nd Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry working in from the south on the 18th. Next day they repelled a 10th Brigade attack from Montevarchi, knocking out two Three Rivers tanks. Under continual pounding from self-propelled batteries with both British brigades, the enemy vacated Ricasoli during the night, and early on the 20th the Three Rivers’ “A” Squadron climbed into the village with the East Surreys and pushed on along the left of the highway. In the rugged terrain the squadron received valuable assistance from a sub-section of the 1st Canadian Assault Troop, Canadian Armoured Corps,†

† The 1st Canadian Assault Troop was formed in Italy on 1 June 1944 to carry out engineer duties with the 1st Armoured Brigade. Its two officers and 84 other ranks-all Canadian Armoured Corps personnel-were given special training in methods of keeping tank routes open, including the use of demolitions and the removal of mines and booby traps. A section of the Troop joined each armoured regiment on 18 July.118 (At the same time the 5th Canadian Assault Troop was organized to work with the 5th Armoured Brigade.)

whose pioneers on one occasion blasted a way

for the tanks through a twelve-foot cliff face. On a ridge 2000 yards north of Ricasoli the infantry-tank force surprised and captured a party of 38 Hermann Görings whose officer is reported to have refused to believe that Shermans could make their way through to his position.119 It was appropriate that this parting Canadian thrust against the Hermann Goring Division before it left Italy should have been delivered by the Three Rivers Regiment, for it was a rearguard of this same enemy formation that, a year before, almost to the very day, had ambushed a group of Three Rivers tanks outside Grammichele, in Sicily, thereby precipitating the first action between Canadian and German forces in the Italian campaign.

At this point the Canadian Armoured Brigade’s six weeks’ association with the 4th British Division ended, and in a farewell message to Brigadier Murphy the GOC expressed his appreciation for “the sterling work” done by the Canadians. “All the soldiers in my Division”, wrote General Ward, “have found cooperation with your regiments a very easy business, and all are impressed by their splendid determination and fighting spirit.”120 In the past three weeks, despite the delay at the Arezzo Line, infantry and armour had advanced together more than 35 miles from the rear Trasimene positions to the valley of the Arno. During that time the Canadians had suffered casualties of 26 killed and 102 wounded. Their relief by the 25th British Tank Brigade began on 20 July as part of a general regrouping of the 13th Corps.121

With the departure of the Corps Expeditionnaire Français to prepare for participation in Operation ANVIL General Kirkman took over the sector which General Juin had been holding astride Highway No. 2 on the Fifth Army’s right flank. This extension of his frontage, while increasing his responsibilities, gave the British GOC a wider choice of areas in which to strike at the enemy. In the Arno Valley the 13th Corps’ advance had come to a virtual halt, particularly east of Highway No. 69, where the 6th Armoured Division found its path blocked by two and a half German divisions between the river and the great barrier of the Pratomagno. By contrast, opposite Kirkman’s left flank, the ten-mile front between the Chianti Hills (which formed the German inter-army boundary) and Highway No. 2 was held by only two divisions of the 1st Parachute Corps.122 To take advantage of the expected lighter resistance in this sector the Corps Commander shifted the weight of his attack westward. He moved the 2nd New Zealand Division over to the left of the 6th South African Armoured Division and ordered both those formations to make a strong thrust northward to secure crossing-places over the Arno at and west of Florence. In the western half of the sector taken over from the Fifth Army he placed the 8th Indian Division, transferred from the 10th Corps, and assigned it the role of protecting the Corps flank and following up the main attack.123 On 22 July, as the New Zealanders and the Indians were completing the

relief of the French Expeditionary Corps, the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade passed under command of the 8th Indian Division, thereby renewing a partnership which had been initiated in the Adriatic sector and substantially strengthened at the breaking of the Gustav Line.124

Moving by way of Highway No. 73 and Siena the Canadian armoured regiments joined the Indians in the Poggibonsi area. General Russell began a two-pronged advance on 23 July, sending his 2 1st Brigade forward on the right astride Highway No. 2, and the 19th Brigade along the secondary road which from Poggibonsi followed the valley of the River Elsa and reached the Arno near Empoli, 20 miles west of Florence. For four days, pending the arrival of the Three Rivers from the Montevarchi area, The Calgary Regiment supported both these thrusts while the Ontarios waited in reserve with the remaining brigade of the division. The Ontarios were thus privileged to provide a guard of honour to represent the Canadian brigade at a ceremonial parade outside Siena on 26 July, when His Majesty decorated a Sepoy of the 19th Indian Brigade with the Victoria Cross, won at the crossing of the Gari.125

The Calgaries now found themselves following up rearguards of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division,126 old opponents of the 1st Canadian Division. These offered little opposition other than by mines and demolitions and occasional long-range shelling, for the successful attack launched two days earlier by the South Africans and New Zealanders had started a general German withdrawal between the middle Arno and the Elsa.127 While the Calgaries’ “A” and “B” Squadrons advanced slowly with the 19th Brigade through Certaldo and Castelfiorentino (General Russell’s orders were to apply no strong pressure on the enemy), “C” Squadron supported a Mahratta battalion of the 21st Brigade up Highway No. 2 as far as Tavarnelle, thence turning north-westward along the New Zealanders’ left flank.128 “We were scarcely playing an inspired role”, recorded the Calgary diarist on the 24th. “The engineers and assault personnel were worked to the limit, while the enemy retired leisurely laying still more mines.” There was even time for squadron cooks to attend a short course of instruction on the serving of dehydrated potatoes.129

First signs of stiffening resistance came on 26 July along a line through Montespertoli, thirteen miles north of Poggibonsi. This was the western extremity of the Germans’ “Olga” delaying position, which had brought the New Zealand and South African Divisions to a halt on the previous day.130 The 4th Parachute Division, holding the ten-mile line, was well supported with self-propelled anti-tank guns, medium guns and Tiger tanks, as the Calgaries’ “C” Squadron with the 21st Brigade on the Indians’ right flank found to its cost – suffering six casualties and losing two tanks.131 That

night the Three Rivers relieved the squadron, and when the advance was resumed early on the 27th, it was found that the enemy, not waiting for a major attack on the “Olga” Line, had once more broken contact. Indian infantry and Canadian armour pushed on half a dozen miles along fairly good roads winding between the steep vine- and olive-covered slopes of the rich Chianti countryside. The speed of the enemy’s retirement had given him little time to mine or carry out demolitions, and before the day ended the 8th Indian Division’s right-hand thrust had reached to within two miles of Montelupo at the junction of the Pesa River and the Arno.132 Here the 21st Brigade, waiting for the formations on either flank to catch up, began preparing for an attack north-eastward across the Pesa. Enemy shelling was troublesome, for the rapidity of the advance had placed the forward troops beyond the range of counter-battery action by the divisional artillery. Fortunately air support was readily available, and shortly after midday on the 28th 48 RAF Spitfires*

* The transfer of combat elements of the Twelfth Tactical Air Command to Corsica in mid-July to support ANVIL left the Desert Air Force responsible for air operations on behalf of both the Fifth and Eighth Armies in Italy.133

bombed and strafed the hostile batteries into silence.134 That night patrols of both brigades probing to the Arno found Empoli and Montelupo held by rearguards of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division.135

By the 29th the 13th Corps’ advance had been halted by the last of the enemy’s planned delaying positions south of Florence. This was the Fourteenth Army’s “Paula” Line, which from the Arno at Montelupo followed the right bank of the River Pesa for seven miles before swinging eastward across Highway No. 2 to the Tenth Army boundary, four miles west of Highway No. 69.136 Holding the main front from the River Elsa to the Middle Arno ten miles north-west of Montevarchi, were five divisions†

† From west to east the 3rd and 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, the 4th Parachute and 356th Infantry Divisions, all in the 1st Parachute Corps, and the 715th Infantry Division holding the right flank of the Tenth Army.137

– one more than the number which General Kirkman had forward in the same sector.138 The British Corps Commander decided to breach the “Paula” Line in the area about Highway No. 2, both because that road provided the best approach to Florence, and because the heights there were less formidable than in other sectors. Late in the evening of 30 July the 2nd New Zealand Division attacked on a narrow front between the highway and the River Pesa, supported by an extensive artillery programme in which the New Zealand guns were joined by those of the two flanking divisions and an Army Group Royal Artillery. The battle went well, and all initial objectives were taken from the stubbornly resisting 29th Panzer Grenadier Division; but heavy consumption of artillery ammunition made it necessary to postpone the second phase of the attack for twenty-four hours while stocks were replenished.139

As the New Zealanders struck again on the night of 1–2 August, the 8th Indian Division went into action on their left. Units of the 21st Brigade, supported by all three squadrons of the Three Rivers Regiment, secured a bridgehead over the Pesa at Ginestra, three miles upstream from Montelupo.140 By daybreak on the 3rd the New Zealanders and South Africans had broken through the main “Paula” line and were driving towards Florence on the heels of a retreating enemy. That night Three Rivers tanks helped Mahratta and Punjabi infantry chase German rearguards out of the villages of Inno and Malmantile in the angle between the Pesa and the Arno. By the evening of 5 August the south bank of the Arno from Florence to Montelupo was firmly in Allied hands.141

The Three Rivers and Calgary Regiments had now reached the limit of their advance on Florence. For a few days they remained immediately south of the Arno, held in readiness for counter-attack if required, and occasionally firing in support of the infantry engaged in extending their control of the near bank. Then they began concentrating with their brigade headquarters in the general area of Greve, a dozen miles south of Florence.142 Before leaving the battle area they had been joined briefly by The Ontario Regiment, which on 3 August came forward with the 17th Indian Brigade in the centre of. the divisional sector. Within forty-eight hours, however, the Ontarios had been whisked out of the line again and transferred to the command of a formation which had just arrived south of Florence, and whose presence the enemy did not suspect – the 1st Canadian infantry Division.143

The Organization of the 12th Brigade

Before seeking the reason for the 1st Division’s appearance in the Florence area we must consider the fortunes of the main Canadian forces in Italy during June and July.

On withdrawal into Eighth Army reserve at the end of the battle for Rome the 1st Canadian Corps had settled in the upper Volturno Valley for a period of rest and refit. Corps Headquarters was established at Sant’ Angelo d’Alife, near Raviscanina, while seven or eight miles to the east units and formations of the 1st Division were camped about Piedimonte d’Alife at the southern foot of the great Matese barrier. The 5th Armoured Division’s area was on the west bank of the Volturno, in the region of Dragone and Alvignano.144 For the battle-weary troops there were opportunities for short periods of leave in Rome (where accommodation was provided for 180 Canadian officers and 1000 other ranks),145 and unit parties made 48-hour excursions to bathing beaches in Salerno Bay and the Gulf of Gaeta.146 In the capital an eight-day exhibition of Canadian war art at the Canada Club on

Map 17: The Advance to the Arno, 21 June–5 August 1944

the Via Nazionale attracted nearly 10,000 civilian and military visitors.147 The three companies of the Canadian Dental Corps in the field*

* A fourth company, No. 11 Base Company, formed in the theatre in May 1944, had assumed responsibility for the dental treatment of troops in the Base and L. of C. units, besides serving as a reinforcement depot for the forward companies.

took advantage of the relatively static condition of the various units to carry out treatment of a large number of officers and men. Although a few engineer and transport units of the Corps Troops were employed on Eighth Army duties148 (field companies of the 1st Division assisted Royal Engineers to reopen a railway north of Rome and other RCE units were busy reclaiming bridging material on no longer essential routes in the rear areas),149 most of the combatant troops were available for training. The lessons learned in the operations in the Liri Valley were assiduously rehearsed by all arms on the sun-baked Volturno flats, and in the surrounding foothills battalions of the 1st Division practised infantry-cum-tank tactics with armour of the 21st British Tank Brigade, which was destined to support the Canadian division in forthcoming operations over just such irregularities of ground.150 Infantry officers received special instruction in a simplified method of controlling the fire of supporting artillery by observed shooting. Each company and platoon commander practised the procedure in turn, using guns firing live ammunition from a neighbouring valley. It was a training which was to prove its value later on occasions when infantry found themselves with no artillery officer available to bring them quick supporting fire.151

The generally rugged nature of the Italian terrain, which admirably suited the enemy’s style of close defensive fighting and his delaying tactics in withdrawal, was largely responsible for an important reorganization in the 5th Canadian Division during July. During the pursuit from the Hitler Line the 11th Infantry Brigade had been severely overworked while trying to maintain the momentum of the advance in the exacting country west of the Melfa, and on 3 June the Corps Commander drew the attention of Canadian Military Headquarters to the need for two infantry brigades to work in succession with the division’s armoured brigade, pointing out that the Eighth Army was providing additional infantry brigades for two of its armoured divisions.†

† The 61st Infantry Brigade (organized from battalions of the Rifle Brigade) and the 24th Independent Guards Brigade were added to the British 6th Armoured Division and the 6th South African Armoured Division respectively.152

He asked whether one of the operational brigade groups in Canada might be sent to Italy for inclusion in the 5th Armoured Division.153 A request by General Alexander that the War Office support the recommendation of the GOC 1st Canadian Corps was turned down however by the CIGS, who ruled that no “diversions from Overlord” could be agreed to.154 General Leese then proposed that Burns should organize an infantry brigade from existing Canadian units in Italy, suggesting that he use the 5th Armoured Division’s motor battalion (The Westminster

Regiment) and withdraw from the 1st Canadian Corps Troops, for conversion into infantry, the armoured car regiment (The Royal Canadian Dragoons) and the light anti-aircraft regiment.155 (This last unit was being eliminated from British corps in the Eighth Army since the destruction of the enemy’s air power in the Mediterranean had virtually ended the Allied need of anti-aircraft defence forces.)156

In submitting to CMHQ the recommendation that he form the new brigade from resources already available to him, Burns substituted for the armoured car regiment the 1st Division’s reconnaissance regiment (the 4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards) on the grounds that the latter unit had had more experience in infantry fighting.157 When General Stuart notified National Defence Headquarters of Leese’s request, he was warned by the CGS, Lt-Gen. J. C. Murchie, that because of the probable increase in the number of infantry reinforcements that would be required the proposal was unlikely to find acceptance unless it was militarily necessary.158 Stuart flew to Italy (see above, p. 451n), and on 12 July, having discussed the problem with Generals Alexander and Leese, authorized Burns to proceed with the organization of the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade, later reporting to Ottawa that such a step was an operational necessity.159

The task of organizing the brigade went ahead rapidly, although it was some time before the many complexities arising from conversion to new establishments were all straightened out. Announcement of the change was received with little enthusiasm by those most affected. Every soldier considers his own arm of the service superior to all others, and in the units which were being converted there was natural disappointment at the prospect of becoming infantry and apparently sacrificing many years of specialized training. The loss of their armoured vehicles was a bitter blow to the men of the 4th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment. “These were our homes for a long time, and no cavalryman ever felt sadder at losing a faithful and tried mount”, recorded the unit diarist,160 and added that when the sad news was broken to the officers of the regiment, “much vino was consumed in an effort to neutralize the pains of frustration, despair and complete loss of morale.”161 This disturbed feeling quickly passed, however, for in the urgency of building and training the new battalions there was little time for prolonged regrets. It may be noted here that the change was not a permanent one; although none could then foresee it, within eight months the 12th Infantry Brigade was to be disbanded, and its units were to return to their original role (below, p. 663).

The 4th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment (4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards), discarding their reconnaissance label for the balance of their stay in Italy, retained their pre-war name – the 4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards. They were replaced as the 1st Division’s reconnaissance unit by The Royal Canadian Dragoons. The converted 1st Canadian Light

Anti-Aircraft Regiment (temporarily using the improvised title of the “89th/109th Battalion”, from the numbers of the two batteries*

* The regiment’s third battery, the 35th, had become No. 35 Canadian Traffic Control Unit on 15 June-an outcome of the traffic difficulties in the Liri Valley-and was undergoing training in provost duties.162 The new infantry battalion drew additional men from the 2nd and 5th Canadian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiments, which in common with all divisional anti-aircraft units in the theatre reduced each battery by one troop.163

which formed the nucleus of the new unit)164 was at first officially designated the 1st Canadian Light Anti-Aircraft Battalion;165 but, seeking a title which would “indicate a Highland unit from Ontario or Eastern Canada”,166 it was renamed in October†

† Final decision on a name for the new battalion was reached only after much discussion. One of the more original suggestions, designed to “show origin, which we think advisable”, was that proposed by the Minister of National Defence – “Laircraft Scots of Canada”167

The Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment.168 The Westminster Regiment (Motor) underwent no change in name or establishment, for the Corps Commander considered it essential that although the unit was to serve as an infantry battalion in the 12th Brigade, it should also be available to be used as motor battalion for the 5th Armoured Brigade. Ottawa approved the recommendation and authorized the provision of reinforcements for the battalion’s dual role.169 The new brigade’s support group, consisting of a mortar company (eight 4.2-inch mortars) and a medium machine-gun company (twelve Vickers), was furnished, like that of the 11th Brigade’s, from The Princess Louise Fusiliers. It was named the 12th Independent Machine Gun Company (The Princess Louise Fusiliers), the 11th Brigade Support Group being redesignated to conform.170

Command of the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade was given to Brigadier D. C. Spry, who was transferred from the 1st Brigade; but after a busy month of organizing and directing training, he left for France on 13 August to take over the 3rd Canadian Division. He was succeeded by Brigadier J. S. H. Lind, former commander of The Perth Regiment.171

The Red Patch at Florence, 5-6 August

The first intimation of a return to active operations by the Canadian Corps came on 18 July, when word was received from the Eighth Army that towards the end of the month the Corps would begin secretly concentrating near Perugia.172 In discussions with General Leese two days later General Burns learned that “the task of the Canadian Corps was not yet definitely determined, but generally it was intended to continue the offensive against the enemy and break through the Gothic Line.”173 The Corps Commander subsequently found174 that his headquarters would have no part in the main attack, which was designed to penetrate the line between Dicomano (fifteen miles north-east of Florence) and Pistoia.175 He was to take over the 10th

Corps’ eastern flank in the Central Apennines*

* The relief of the 10th Corps was slated to begin on the night of 6-7 August, with the Canadians becoming responsible for a 25-mile sector between Gubbio and Citerna, which would ultimately be extended 40 miles westward to Pontassieve176 (see map at back end-paper).

so as to enable the 10th and 13th Corps to concentrate for the Eighth Army’s share in the offensive; the 1st Division, however, would reinforce the 13th Corps at Florence.177

The Canadian stay in the Volturno Valley culminated on 31 July with the visit of His Majesty and the royal investiture of Major Mahony of The Westminster Regiment (see above, p. 434).178 Next day the 1st Division began moving to a concentration area in the hills north of Siena, near Castellina in Chianti.179 During the week the remainder of the Corps followed northward to the vicinity of Foligno, Corps Headquarters setting up its tents four miles south of the city in the inevitable olive grove. Strict precautions were taken during these moves to ensure that the same cloak of secrecy which had shrouded the transfer of the Corps from the Adriatic sector in the preceding spring should now conceal from the enemy the arrival of Canadians behind the central front. (At the time – as we shall see later – the Eighth Army was executing an elaborate cover scheme to convey the impression that the 1st Canadian Corps was assembling behind the 2nd Polish Corps, preparatory to an attack on the Gothic Line in the Adriatic sector. )180 Before any troops left the Volturno Valley they painted out formation and unit identification signs on their vehicles and removed from their uniforms “Canada” badges and all other distinguishing patches and flashes, not forgetting the ribbon of the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal. Towns along the way were put out of bounds, and the customary collection of unit direction signs lining the highway were replaced by route markers carrying only a single letter.181 That these measures effectively frustrated the inquisitiveness of those whom our intelligence staffs called “short range agents”182 among the civilian population is shown by the significant silence of enemy war diaries regarding the true whereabouts of the Canadian formations at this time.

By a strange irony these elaborate precautions went for nought. On 4 August the illusion we had sought to create of a forthcoming drive in the Adriatic sector became our actual intention when, for reasons that will be shown in the next chapter, General Alexander abandoned the idea of a two-army attack through the central Apennines in favour of an offensive on the right flank by the Eighth Army.183 The change in plan cancelled the Canadian relief of the 10th Corps but did not affect the move of the 1st Division. Red patches and unit flashes returned to arms and shoulders, and vehicles once more showed their distinguishing signs; for not only was anonymity no longer necessary, but it was desirable to advertise to the enemy the presence of Canadians at Florence and so destroy the earlier concept of their being on the east coast.184

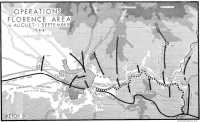

Sketch 8: Operations, Florence Area, 6 August–1 September 1944

On the evening of the 5th the 2nd Canadian Brigade took over the 2nd New Zealand Division’s sector of the now almost static front, and next night on their right the 1st Brigade relieved the 6th South African Armoured Division (see Sketch 8). The New Zealand Division was thus enabled to shift to the left and allow the 8th Indian Division to pass into corps reserve.185 The Canadians now faced the Arno on a ten-mile front, which in the 1st Brigade’s sector included the triangular portion of Florence which lay south of the river. The German garrison – three battalions of the 4th Parachute Division – still controlled the nine tenths of the city which lay on the right bank.186 German engineers had blown all the Arno bridges except the famous fourteenth-century Ponte Vecchio in the heart of old Florence, and they had ensured that no Allied vehicle would readily test its frail shop-lined footway by systematically demolishing a number of fine old mediaeval houses on either bank in such a way as to block the approaches at both ends.187 The bulk of the city’s population had made no move, and the front line provided the uncommon spectacle of soldiers crouching in watchful readiness with weapons at the alert, while civilians cycled or strolled past in apparent unconcern of stray bullets. The Canadians were using only their rifles and machine-guns, the firing of PIATs and mortars in the built-up area being forbidden – for Allied Force Headquarters had ruled that “the whole city of Florence must rank as a work of art of the first importance.”188

It soon became apparent that not all the Italians south of the river supported the Allied cause. The RCR, holding the waterfront east and west of the Ponte Vecchio, suffered casualties from civilian snipers on nearby rooftops and from occasional mortaring and shelling which the enemy, less punctilious about preserving undamaged the treasured fabric of the city, was bringing down with the assistance of Fascist observers in the area. To end this practice a force of 250 Italian Partisans, assisted by a score of the battalion’s “tommy-gunners”, combed the south bank on 8 August, entering every building and scrutinizing its inhabitants. They rounded up more than 150 suspects, and enough rifles, pistols and hand grenades (some of these being found in the women’s purses) to fill two 15-cwt. trucks.189

The 1st Division’s brief stay in the Florence sector ended on 8 August. Its attachment to the 13th Corps had enabled General Kirkman to carry out among his tired formations a series of welcome reliefs, some of them short but none the less necessary; now fresh commitments awaited it on the Adriatic coast. That evening the Canadians were relieved by the 8th Indian Division, and, once more under the strictest security regulations, they moved 30 miles southward to a staging area outside Siena.190 By nightfall on the 10th the Division had rejoined the 1st Canadian Corps in the Perugia–Foligno area.191

Canadian Armour Across the Arno

On the withdrawal of the Canadian infantry from Florence, The Ontario Regiment, which General Vokes had held in a counter-attack role in the south-western suburbs of the city, reverted to the command of the 8th Indian Division.192 Brigadier Murphy’s other two regiments stayed in reserve near Greve, the Calgaries for the next fortnight, and the Three Rivers until early in October. For another week the Ontarios remained south of the Arno, shelling fairly steadily the main routes leading north-west from Florence, and occasionally sending a troop of Shermans with a party of infantry to deal with enemy patrols reported on the near bank.193 During the night of 10–11 August the rearmost elements of the 4th Parachute Division withdrew across the Mugnone Canal into the northern suburbs,194 and at daybreak white flags flying along the Arno waterfront signalled this departure, which Partisan patrols promptly confirmed. Infantry of the 8th Indian Division and the 1st British Division on its right crossed the river and began organizing the movement of food, medical supplies and water to the starving population in the main part of the city. The opening of the Ponte Vecchio to jeeps on the 14th eased the problem of supply, and next day the Royal Engineers completed a Class 30* Bailey

* The numerical classification of a military bridge represents approximately the “live load” (i.e., of moving vehicles suitably spaced) in tons which may safely cross it.

on the piers of a demolished bridge 300 yards downstream.195