Chapter 3: The Germans in France, 1940–1944

(See Map 1 and Sketches 2 and 3)

THE coast which British, Canadian and American forces assaulted in Normandy on 6 June 1944 had been in German hands for four years. For two of those years Hitler’s engineers had been constructing defences which the dictator hoped would render it impregnable; and for five months before our attack this work had been pushed with particular energy.

The availability of German records makes it possible to describe the enemy’s strength, defences and organization with considerable accuracy. These things are the themes of the present chapter. No attempt will be made, however, to tell the story in all its detail. Much has already been published on the subject elsewhere.1 Our object therefore is to summarize the essentials, adding such significant new information as is available and dwelling in detail only upon those aspects which are of special interest to the Canadian Army.

The Creation of the Atlantic Wall

As we noted in an earlier volume,* the victorious German armies that came out upon the French coast in 1940 were not thinking of defence, but of attack; and it was only gradually that the changing aspect of the war forced German minds towards the concept of a fortified defensive front along the Channel. By the end of 1941, Hitler’s plans “to crush Russia in a swift campaign”2 had miscarried. In December of that year the United States entered the war. As the Russian front created an insatiable demand for men and materials, the West became of secondary importance to the German High Command, and was to remain so until OVERLORD burst upon them. Even after the full mobilization of German manpower and resources under Albert Speer in 1942, the German leaders were forced to supply the needs of the eastern front at the expense of the west. It was this shortage of manpower to conduct war on such a grand scale which led to the idea of a “new West Wall” along the coast of France.

Hitler first laid down the principle of extensive fortification against seaborne attacks in his Directive No. 40 of 23 March 1942.3 Fears that the Allies might

* Six Years of War, 349.

land in France to relieve pressure on the Russians gave urgency to the work. At conferences on 2 and 13 August Hitler was reported by General of Engineers Alfred Jacob to have said that there was but one front, the other could be a defensive one only, held by small forces. Thus on the principle of “the stronger the fortress, the smaller the number of troops required”,4 the defences were to be such that they could be taken neither frontally nor from the rear except by an attack lasting for weeks. The successful repulse of the raid on Dieppe a few days later reinforced the belief of Hitler and at least some of the senior commanders in the effectiveness of strong fortifications in defeating a seaborne invasion on the beaches.* Lured on perhaps by the belief that an actual attempt at invasion had been defeated, they were convinced of the need to extend defences along the whole coast.5

Field-Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, then 67 years old, was again made Commander-in-Chief West, and Commander of Army Group D, in March 1942.6 This appointment he was to retain, with the exception of a short period during the North-West Europe campaign, until March 1945. On 25 August 1942 (a week after Dieppe) he issued a basic order for the development of the Channel and Atlantic coast defences stating that the “Wall” would be built in such a way “that no attack from the air, the sea or the land shall appear to have any prospect of success. ...”7 He ordered that during the approaching winter half-year, 15,000 installations of permanent fortress-like construction were to be built, 11,000 of them on the coasts of Belgium and France as far as the Loire, 2000 on the Bay of Biscay, and 2000 on the Dutch coast. It was intended that these installations would fortify the coasts “continuously throughout their entire length after the pattern of the Upper Rhine front”,8 in addition to providing protection for the U-boat bases, harbours and heavy coastal batteries. Construction was to be undertaken by the Army’s fortress engineers and the Organization Todt,† the latter being, in the main, responsible for it. Rundstedt required an overall construction plan for the entire coastline, showing the number of installations to the kilometre, to be submitted to him by 15 September. But it was one thing to draw the blueprint for the Atlantic Wall; the colossal task of construction was another. It was not easy to find the required quantities of labour and concrete and steel. Soon there were to be competing demands for resources from the Navy for U-boat installations and gun emplacements, and from the OT itself for its other tasks of repairing bomb damage, and, in 1943, for building launching-sites for the V-weapon offensive against England.9

What was the actual picture which the Germans had in their minds of the finished Atlantic Wall? “Wall” was a propaganda term. To build a continuous barrier along the 1200 miles of coastline from the Netherlands to the Spanish border would have taken unobtainable quantities of steel and concrete. What did

* The condition of the German defences up to the Dieppe raid, and the effect of the raid on German thinking, have been dealt with in Six Years of War, Chaps. XI and XII.

† Named after its first head, Fritz Todt, designer of the Autobahn and the West Wall (Siegfried Line); a para-military organization employed as the construction arm of the Wehrmacht. It was, however, under the Ministry of Armament and War Production. The Reich Labour Service and impressed foreign workers made up its labour forces.10

develop, as Colonel-General von Salmuth, commander of the German Fifteenth Army, complained (with considerable exaggeration) in October 1943, was not a wall but rather a “thin, in many places fragile, length of cord with a few small knots at isolated points”.11 By July 1943 about 8000 installations*12 had been reported completed or in various stages of construction.13

Rundstedt had comparatively little faith in fortifications, but to Hitler they were a part of his strategy of “defence by the millimetre”.14 He forbade retreat and demanded resistance to the last, for to his mind fortifications were made to be held, even if in holding them commanders were forced into operations as inflexible as the concrete they were to defend. In an “Estimate of the Situation on the Western Front” written in the autumn of 1943, von Rundstedt expressed the view that fixed defences were necessary as protection against heavy bombardment and thus were “indispensable and valuable for battle as well as for propaganda”.15 He saw disadvantages, however, in placing infantry with heavy weapons in concrete shelters. They would probably not emerge at the crucial time, and would, furthermore, be bound to them and unable to exploit the ground as the situation demanded. He remarked, “It is better to have a few installations really completed, camouflaged and therefore fit for defence than to begin many works which lie unfinished, without camouflage, and obstruct the field of fire, and which can only be of use to an enemy force that has landed, by affording it shelter.” He emphasized the point that fieldworks were an indispensable supplement to the concrete structures.16

Even more rigidity was introduced into the defence system in January 1944, when twelve important coastal positions in the Netherlands and France were designated as “fortresses”. This fortress policy, designed to deny large ports to the Allies, was in fact to be a considerable embarrassment to them; but it also tied down great numbers of German troops and a great deal of equipment.17

German Forces in the West

The inadequacies of the Atlantic Wall were not offset by the calibre of the troops which were to man it. After the opening of the Russian front, occupied France and the Low Countries served as training areas for German formations. Here they would be formed, built up, quartered and trained before being shipped off to the Eastern front, and in many cases when they had been virtually destroyed the remnants would be brought back for refitting and rehabilitation. Thus the mere Order of Battle of the German Army in the West does not give an accurate picture of the forces which Rundstedt could expect to be available should he be required to defend the coasts.

* The design of these installations depended upon their use and the number of men who were to occupy them. In general a “fortress-like” construction corresponded to 2.5 metres of steel-reinforced concrete.

† Ijmuiden, Hook of Holland, Dunkirk, Boulogne, Le Havre, Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, and the northern and southern sections of the Gironde estuary. Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney were added to the list in March.

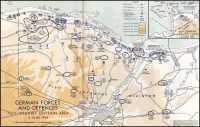

Map 1: German Forces and Defences 716th Infantry Division Area, 6 June 1944

When the Allies invaded North Africa in November 1942, the Germans occupied Southern France. Despite this additional commitment, the C-in-C West saw his forces reduced in 1943 as a result of the series of reverses which overtook the German cause. During January the Sixth Army was being destroyed at Stalingrad, and by spring the once-glorious Panzerarmee Afrika was nearing the end of its long retreat from El Alamein. Despite the repeated efforts of Rommel to have it brought back for the defence of Europe,18 it shared the same fate of captivity as the other Axis forces in North Africa.

When the North Africa campaign was over, the next Allied move was a puzzle to Hitler and the German High Command. The forces now available to the Allies might be used for an attack anywhere along the Mediterranean coastline from the Spanish border to the Balkans, or they might join with those assembling in England for an invasion across the Channel.19 Five days before our invasion of Sicily supplied the answer, Hitler had made another fateful move with Operation CITADEL, a counter-offensive on the Russian front, which absorbed his major reserves. The wisdom of the operation was questioned in the light of the new threats in the West, but Hitler overrode the advice of his staffs and ordered it to begin on 5 July.20

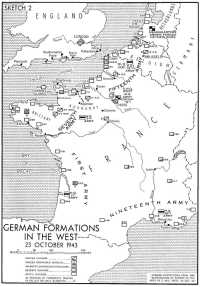

Rundstedt had little hope of stopping the drain on his resources. CITADEL had taken some of his formations designated for Plan ALARICH, which had been devised in May to deal with the possible defeat of Italy. Soon it was to be necessary to give up formations* to the Italian campaign as well. On 27 June von Rundstedt pointed out that the mobile formations which he had left were such in name only, and requested that they be reequipped. To this the High Command replied that holding the Atlantic Wall was the way to defeat enemy landings.21 In all, between October 1942 and October 1943, 36 infantry and 17 armoured and motorized divisions, including such good formations as the 7th Panzer and the SS Divisions Adolf Hitler, Das Reich and Totenkopf, left the West for other theatres.22 This loss was not of course absolute, since some divisions had arrived or had completed their training or recuperation during that period. The German order of battle chart for 26 October 1943 shows 40 divisions in the West, in addition to nine in process of formation (see Sketch 2); but Rundstedt represented that there had been a great decline in quality during the year.

Most of the divisions involved in the continual shuffling were of the better type. Defence of the coastline proper was mainly in the hands of the static (bodenstandig) divisions. In the autumn of 1943 there were 19 of them on the west coast.23 Like the fortifications, they were to be permanently installed to bear the brunt of any invasion. Frequently their best personnel were taken in mass drafts as reinforcements for the East. In the autumn of 1943, 45,000 men were removed in this way, and in return the commanders were promised the newly called-up 18-year-olds.24 In time the static divisions came to be made up of very young men (“babes in arms”, the commander of the Fifteenth Army called

* E.g., the 1st Parachute Division and the 26th Panzer Division. The effect of the Italian capitulation on German strategy has been dealt with in The Canadians in Italy, Chaps. VII-IX.

them),25 men over thirty-five, those with third-degree frostbite, and the Ostbataillone. These “East Battalions” reflected the seriousness of the German manpower shortage. Formed from Red Army prisoners of war from the many ethnic groups around the Caucasus and Turkestan, they could not, for obvious reasons, be employed in the East, but in the West the disadvantage of their questionable loyalty to Germany was offset by the urgent need to reinforce the coastal defences somehow.26

The static divisions were similarly denied both the most modern equipment and priority on replacements. Their “little anti-tank guns and baby cannon”27 were out of date; some of them had machine-guns of First World War type. Within the divisional artilleries of one Army there were ten different gun types, many of them captured pieces. Of the divisions under the Commander-in-Chief West, 17 had two regiments or the equivalent instead of the normal three; most had limited mobility, and there was much horse-drawn transport; six had less than two battalions of artillery; and in a number of cases the division’s training was considered unsatisfactory in greater or less degree.

These depressing facts were part of the long and frank “Estimate of the Situation”, already referred to, which von Rundstedt forwarded to the High Command on 28 October 1943.28 Only that command, he pointed out, knew Germany’s political objectives and had the resources to achieve them. However, if an invasion in the West was to be defeated, the unrealistic policy of stripping the defences must be reversed. Rundstedt argued that the sector which the Allies were most likely to choose for attack was the narrow part of the Channel, even though this was where the defences were strongest. He thought an attack here, likely to be combined with one against the French Mediterranean coast. On many portions of his long front, “defence”, he said, was in fact impossible; all that could be effected was some “security”, and on the Biscay and Mediterranean fronts nothing better than “a reinforced ‘observation’”. The principles of defence which he laid down were these. “The coast and its fortifications must be held to the last” with a view to weakening the enemy as much as possible; but the fact must be accepted that the enemy would inevitably succeed in landing large forces, particularly in areas where the defences were weak:–

Conclusions: In spite of all fortifications a “rigid defence” of the long stretch of coast is impossible for any considerable length of time.

This fact must be kept in mind.

The defence therefore is based primarily on the general reserves, especially of tanks and motorized units. Without them it is impossible to hold the coasts permanently. But these reserves must not only be available in sufficient number; they must be of such quality that they can attack against the Anglo-Americans, that is, against their material, otherwise the counter-attack will not go through.

What was needed to defeat invasion was, first, a reinforcement of the defensive power of the coastal fronts by providing triangular (three-regiment) divisions with three-battalion artillery regiments (including one heavy battalion), adequate antitank armament, enough supply troops, and sufficient mobility to enable divisions manning unattacked sectors to be withdrawn thence and committed as field formations against the enemy’s points of main effort. Secondly, to provide the

Sketch 2: German Formations in the West, 23 October 1943

mobile reserves which were the most essential element in his plan, Rundstedt calculated that, taking the Mediterranean coast into account, nine “completely fit armoured and motorized divisions” were required for his area of command.

This gloomy report brought some results. On 3 November 1943 Hitler issued his Directive No. 51 in which he stated, “I can no longer justify the further weakening of the West in favour of the other theatres of war. I have therefore decided to strengthen the defences in the West, particularly at places from which we shall launch our long-range war against England.”29 In general the strengthening was to take the form of greater fire power and mobility. Artillery for coastal protection, and the number of anti-tank guns and machine-guns for the static divisions were all to be increased. Panzer divisions were each to be brought up to a strength of 93 Mark IV tanks or assault guns. All available men from training schools, convalescent units and security groups were to be formed into operational units. The Luftwaffe was ordered to increase its effectiveness “to meet the changed situation”. The Navy was to prepare “the strongest possible forces suitable for attacking the enemy landing fleets”. The SS, the Nazi Party’s security army under Himmler, was called upon to relieve as many men as possible for combat duty.30

If the demands which it contained could have been met, the Führer’s directive would have meant an important change in policy. Undoubtedly the West did receive more men and materials as a result, but by this period German strength had been dissipated to such an extent that the directive is an indication of the unrealities in which Hitler was to deal increasingly in the coming year. New tanks, flame-throwers, jet aircraft and V-weapons were all to fire his imagination and lead him to make promises to his commanders which could never be fulfilled.31 The suggestion that the Luftwaffe, in its sorry state, could “meet the changed situation” shows little appreciation at Hitler’s headquarters of the weight of air power that was to support the assaulting forces. In the Army sphere, however, there were considerable improvements. By 6 June 1944 the total number of divisions in the West had been materially increased. The armoured force had reached the strength, though not the standard of quality, for which Rundstedt had asked; there were now 10 panzer or panzer grenadier divisions in the West, though four of them were not fully ready for battle. But the static divisions that would have to take the first shock of the attack were still much as they had been in October 1943, weak in strength, equipment and mobility.

The Advent of Rommel

At this time Hitler made an important change in the system of command in the West. Field-Marshal Erwin Rommel, with the staff of Army Group B,* was appointed what might be called Inspector General of Defences in the West.32 Rommel, who had shown himself in Africa an energetic leader and an extremely

* Rommel and his staff had been preparing to take over the Italian theatre (see The Canadians in Italy, 265, 269). In the autumn of 1943 Army Group B was sometimes referred to as Army Group for Special Employment.

able tactician, enjoyed high prestige and popularity in Germany; and in the circumstances of the moment energy was necessary. Moreover, his appointment might provide a fillip to morale.

Army Group B was in the first instance a headquarters without troops. Its assignment was to submit proposals on the coast defences and to prepare studies for offensive operations against Allied landings; and it was to be directly under Hitler.33 Rommel was at first concerned with Denmark and did not arrive in France until 14 December.34 His appearance there placed him in an anomalous relationship with Rundstedt, who until this time had had under his command the German troops in the Netherlands (for tactical purposes), the Fifteenth Army from the Dutch border to west of the mouth of the Seine, the Seventh Army thence to the mouth of the Loire, the First Army on the Bay of Biscay, and the Nineteenth Army on the Mediterranean coast.35 Although Rommel had direct access to Hitler, and was empowered to make recommendations, he had no authority over any of these forces. This situation was changed at the end of the year when Army Group B was given command of the troops in the Netherlands and the Fifteenth and Seventh Armies. Thus Rommel took operational control of the anti-invasion forces in the most threatened sector. He continued, theoretically at least, to be subordinate to Rundstedt as Commander-in-Chief West, but he did not hesitate to deal directly with Hitler.36 Before the invasion began the other two Armies, the First and the Nineteenth, were formed into Armeegruppe G under Colonel-General Johannes Blaskowitz.37 (An Armeegruppe was a formation of lower rating than a Heeresgruppe, the appellation of the other Army Groups in the West.)

Unlike many other senior German commanders, Rommel had felt the weight of the Allies’ powerful tactical air weapon. Even before the Battle of El Alamein, it appears, he had come to the conclusion that British air superiority now limited the Germans to a more or less static defence. “...We could no longer rest our defence on the motorised forces used in a mobile role, since these forces were too vulnerable to air attack. We had instead to try to resist the enemy in field positions which had to be constructed for defence against the most modem weapons of war.” He now felt that the same factor invalidated any plan of defence in North-West Europe which depended upon major movements by mobile reserves. Pushed to their logical conclusions, these views simply implied that the war was already lost; but it is doubtful whether Rommel as yet admitted this even to himself. With characteristic energy he set to work to reorganize the defences in accordance with the facts as he saw them, with the Atlantic Wall strengthened to the utmost and the reserves disposed close behind it ready for immediate intervention. On the last day of 1943 he reported to Hitler, “The battle for the coast will probably be over in a few hours and, if experience is any judge, the rapid intervention of forces coming up from the rear will be decisive.”38

These opinions led Rommel into a fundamental conflict with von Rundstedt. The latter, with his wider responsibility, favoured the retention of the few armoured formations, when they were ready, as centrally-located reserves ready to be thrown into a powerful counter-attack at the strategically correct moment.

Both views had much to commend them. Rommel argued that the coastal divisions would not stand up to the heavy naval and air bombardment and the airborne landings that he foresaw. Furthermore, the Allied air forces would so retard the movement of the armoured formations from their central locations that they would arrive too late. Rundstedt’s reply was the simple one that if the reserves were close to the coastline they might, considering Allied skill at deception and feint, be in the wrong places. There was general agreement that the danger area would be in the Fifteenth Army’s sector around Calais or on either side of the Somme estuary, but Rundstedt was reluctant, in the absence of reliable intelligence, to tie down the mobile formations. Both opinions had adherents among senior commanders. In January, Hitler, with whom final decisions rested, supported Rundstedt, but later in the spring Rommel was able to convince him that Army Group B should have control over some of the armour.39

To offset the Atlantic Wall’s deficiencies Rommel planned to make extensive use of mines and obstacles. He wanted a mined zone, five or six miles deep, along the coast, capable of being defended against assault either from the sea or from the rear. He felt that by following the British pattern at Tobruk, the Germans would be able to hold the attacker at least until his point of main effort could be determined. To carry out such a plan around the coasts of France, it is estimated, would have taken 200 million mines. Some four million were laid in the Channel sectors by 20 May 1944.40

Rommel was somewhat more original with his foreshore obstacles to impede landing craft, and his “asparagus” stakes in the fields behind the coasts to prevent aircraft from landing. The foreshore obstacles, mined at the tips (see below, page 101), were arranged in such a way that landing craft would stick on or be destroyed by them at various tide levels. Rommel realized that time was short for such preparations, but he calculated that when the Allies became aware of what was going on they would have to change their method of approach, as in fact to some extent they did (below, page 88). The obstacles were also thought to have the advantage of requiring a great expenditure of artillery fire and bombs to destroy them, and where the Allies undertook to do so might reveal where they intended to land. The air landing obstacles were ten-foot stakes, driven into the ground about one hundred feet apart. They were to be mined and connected with wire. Although extensive areas were “staked” by the end of May, the wiring and mining had not progressed so rapidly.41

A Confusion of Commands

Hitler had ended his directive of 3 November with the words, “all authorities will guard against wasting time and energy in useless jurisdictional squabbles”.42 It would have been more to the point had he exerted himself to create a system of command that would have obviated such squabbles; but this he would not do. He had concentrated vast powers in his own hands; but he was afraid to concede to his commanders the powers which they needed to win his battles for him.

In February 1938 Hitler himself assumed the functions of War Minister and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The Navy he left at first to Raeder and later to Dönitz, and the Air Force to the trusted but inefficient Göring. Under Himmler there grew up the especially indoctrinated party army, the SS.43 As for the Army, Hitler, increasingly distrusting the General Staff, took over the active command of it himself in December 1941.44 As a result there developed a dual control of military operations. The High Command of the Army (Oberkommando des Heeres—OKH) under the Army Chief of Staff, was responsible for the Russian front. The High Command of the Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht—OKW) under its Chief of Staff, Keitel, and the Chief of its Operations Staff, Jodl, conducted the war in other theatres, including the West.*45 This system, militarily quite illogical, doubtless had from Hitler’s viewpoint the advantage of minimizing other men’s power over the military machine. Hitler, at the head of this dichotomous structure, directed all fronts, and came increasingly to demand that decisions, even in matters of detail, be referred to him. We shall note occasions when his strategical intervention was disastrous for the Germans. Nevertheless, as the records of the Führer’s conferences which have survived indicate, matters of strategy were not his chief or only concern. Like an obsessive neurotic he increasingly spent time and energy on minutiae to avoid the insoluble problems of general policy.46 Apoplexy at the centre led to the inevitable paralysis at the periphery. All the three armed forces, the SS, the Reich Labour Service and other para-military organizations were able to retain varying degrees of control of their forces in the field.

Field-Marshal von Rundstedt, as Commander-in-Chief West, found himself preparing against invasion with limited and inadequate authority. He was not, like Eisenhower across the Channel, a true Supreme Commander with authority over the naval and air forces as well as those of the Army. Hitler’s basic directive on coast defence of March 1942 (above, page 48) had paid lip service to the principle of unity of command. It designated commanders in various theatres who were to exercise such command; in the case of the occupied West, including the Netherlands, the officer designated was the C-in-C West. These commanders were to have authority “over tactical headquarters of the services, the German civil authorities, as well as units and organizations outside of the armed forces that are located within their respective areas”. But this authority was constricted “within the framework of coastal defence tasks”. As a result, the scope of the orders which Rundstedt could issue to the air and naval commanders in his area—the commanders of the 3rd Air Fleet and of Naval Group West—was limited. In all matters which could not be represented as connected with coast defence they were independent of him and functioned on the same level of command as himself.

Certain peculiarities of German organization aggravated the effect of this

* This division of the German war effort into the OKH and OKW theatres, which post-war accounts consider to be its main structural weakness, does not seem to have been defined formally in any directive by Hitler, but rather to have developed from usage, particularly when Zeitzler replaced Halder as the Army Chief of Staff in the autumn of 1942.

Thereafter, as General Westphal puts it, the Army Chief of Staff was “no more than Chief of Staff on the Eastern Front”.

situation. Of the coast artillery batteries, some were manned and directed by the Navy, others by the Army; there were also some Army batteries under naval orders. There were disagreements between the two services on the position and employment of batteries. It was laid down that until after an enemy had landed the naval batteries firing at him would be controlled by naval “Sea Commandants”; only when he had come ashore would they pass to the control of army artillery commanders. At the same time, almost all the antiaircraft artillery units serving with the Army were part of the Luftwaffe, as were also the parachute divisions; these units and formations were under the air force for administration and the army’s control of them was not complete. The position of the Waffen SS, the SS formations, was similar; though under Rundstedt’s tactical control, they were under Himmler in his capacity as Reichsführer SS, just as the Luftwaffe units were under Göring in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the air force. Each of these distinctions tended to create additional friction in the machine.

In addition to the authorities already mentioned, there were two Military Commanders (Militarbefehlshaber), really military governors, one in Paris, for France, and one in Brussels, for Belgium and Northern France. These, with the security troops under their command, were also independent of Rundstedt except for strictly tactical purposes. In the Netherlands a slightly different system prevailed. Here there was a Commander Armed Forces in the Netherlands, with headquarters at Hilversum, who took his orders from OKW and was subordinate to the C-in-C West only for coast defence or in case of actual enemy attack. But the German army formations in the area were under the GOC 88th Infantry Corps (termed Commander of German Troops in the Netherlands), with headquarters at Utrecht; and this officer was responsible for training, equipment and administration of army units in the area, under directives from the C-in-C West.

This was still not quite the whole story. The anomalous relationship of Rommel to Rundstedt has already been described. In November 1943 another headquarters was set up, on Rundstedt’s initiative: Panzer Group West, located at Paris and headed by General Baron Geyr von Schweppenburg. This had the function of forming and training all armoured formations in the West and advising the C-in-C West on the employment of armour. Geyr von Schweppenburg, though he did not always see eye to eye with Rundstedt in everything, in general agreed with him on the question of the disposition of the armoured reserves, and was one more party to the discussion of that much-vexed problem.47

Finally, dominating the whole scene, was the remote control which Hitler insisted on exercising from his headquarters in East Prussia. This was concretely represented by the fact that four of the efficient mobile divisions on which the defence so greatly depended (1st SS Panzer, 12th SS Panzer, Panzer Lehr, and 17th SS Panzer Grenadier) were in the spring of 1944 placed in “ OKW Reserve”; that is to say, they could not be moved into action without OKW authority—which meant, in practice, the personal authority of Hitler.48

All in all, the German command organization in the West in 1944 was weak, confused and chaotic. When Field-Marshal von Rundstedt told Canadian interrogators

after the war, “As Commander-in-Chief West my only authority was to change the guard in front of my gate,”49 he merely exaggerated a situation which was absurd almost to the point of insanity.

German Knowledge of Allied Plans

Through the spring of 1944 the German commanders could do little more than speculate about the coming invasion. Their intelligence staffs were unable to penetrate the screen of Allied security and deception.

In part, this failure can be attributed to the rivalry between the various German intelligence services. Both the armed forces and the Nazi Party operated secret services abroad, the former the Abwehr and the latter the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). Hostility between the two reflected the hostility between the armed forces and the Party. Very few of the higher officers whose task it was to appraise information had any great knowledge of countries outside of Germany, and they were clumsy at interpreting political situations. At Hitler’s headquarters all unpleasant reports were regarded as deliberate defeatism; this frequently led the intelligence services to falsify or withhold information which was unpalatable. Much of the information which came in was from neutral capitals, but the checking of agents’ reports for reliability was poor. There was always the suspicion that some brilliant scheme of deception was being played out.50

One piece of good fortune for German Intelligence, much publicized after the war, was “Operation CICERO”, as a result of which a number of documents appear to have found their way from the British Embassy to the German Embassy in Ankara. By this means the Germans would seem to have obtained some information on our plans, but it is doubtful whether this went further than the code name OVERLORD and the fact that a second front was to be opened in 1944.51 It may have been the CICERO papers which enabled Hitler to say at a conference on 20 December 1943, “There is no doubt that the attack in the West will come in the spring. There’s absolutely no doubt about it.”52 Such knowledge was little comfort.* Nothing was known of the time, place or weight of the invasion. Nor could secret intelligence allay German fears that the Allies might attempt feint landings in the initial stages to tie down the limited garrisons and reserves.

It was, of course, impossible for the Allies to conceal the concentration of forces in the south of England. Deception measures, designed to give the impression that the landings would be launched from south-east England towards the Pas de Calais, were however in general successful. On 20 April 1944, Foreign Armies West, the branch of OKH responsible for intelligence concerning the Western Allies, stated that the confirmed picture of dispositions supported previous

* The CICERO information seems to have been restricted to a very small circle in Germany, and the German documents now available throw no light upon it. Franz von Papen, the German Ambassador in Ankara, states in his memoirs, “our knowledge of Operation OVERLORD was limited to the name”. This, if true, invalidates the statement of his subordinate Moyzisch that the thievish servant known as CICERO supplied “complete minutes of the entire conferences both at Cairo and at Teheran”. It is in any case improbable that such minutes would be in the hands of the British Ambassador in Turkey.

conclusions to the effect that the main attack was likely to come in the area of the eastern Channel ports, and on 13 May it reported, “The focal point of the enemy troop movements is becoming more and more defined as the South and Southeast of the island.”53 This movement of troops southward led it to discount the possibility of an invasion of Norway except perhaps on a minor scale.54

The lack of information from air reconnaissance is striking. In contrast with the situation in 1942, it was only occasionally now that the Luftwaffe ventured across the Channel. In the Folkestone-Dover area there actually seems to have been no flight between 26 July 1943 and 24 May 1944, and in the Poole area none between 12 August 1943 and the same date. The Weymouth-Portland area was not reconnoitred between 21 January 1944 and 24 May. Other references to air reconnaissance in the reports of Foreign Armies West are few. After these flights of May 1944 it was reckoned that the Allies had available landing craft and shipping for sixteen and a half divisions.55 The greatest miscalculation of German Intelligence was their version of the Allied strength and order of battle. In all, 78 divisions were thought to be available to General Eisenhower in England. This exaggerated total was made up of 56 infantry, seven airborne and 15 armoured divisions. The Allies were credited in addition with five independent infantry brigades, 14 armoured brigades and six parachute battalions.56 (The force actually under Eisenhower on D Day was 37 divisions—23 infantry, 10 armoured and four airborne.)57 One of the Allies’ most closely guarded secrets, the artificial harbours, never became known to the Germans, who therefore continued consistently to think that a large port would be our first objective.58

Nothing illustrates the shortcomings of German Intelligence more clearly than its picture of the Canadian Army in England. On 22 March 1944 Foreign Armies West commented as follows59 on the publication of General Crerar’s appointment to command First Canadian Army:

The appointment of General Crerar, former Canadian Chief of the General Staff, and until now in Italy, as Commander of the First Canadian Army in England, along with an as yet unconfirmed report about concentration of the Canadian forces in England (altogether 5 infantry divisions and 3 armoured divisions) in the Wiltshire area, seem to indicate that the highly-rated [hochbewerteten] Canadian formations are to play a role in the forthcoming operations. Whether they will operate independently or under Army Group Montgomery cannot be foretold as yet.

At this time there were three (not eight) Canadian divisions in England; and they were not in Wiltshire. Nevertheless, until D Day the Germans continued to make the same faulty assumptions of strength. Their map of the enemy picture on 6 June 1944 shows the following Canadian divisions: the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions and the 4th Armoured Division definitely identified (to this extent they were right); the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions tentatively identified;* two formations

* As explained in Six Years of War, Chap. V, the 6th, 7th and 8th Divisions were home defence formations which never left Canada. The 7th and 8th were disbanded, and the 6th reduced, in September 1943, and this action was publicly announced. It is not inconceivable that the Germans construed the announcement as a clever deception scheme to cover the movement of these divisions overseas. It is also possible that there was deliberate sabotage in the German intelligence organization.

believed to be Canadian divisions (one of them armoured); while among formations whose whereabouts was unknown but which were believed to be in Britain or Northern Ireland was included a Canadian armoured division tentatively designated the 1st. Such absurdities could scarcely have been perpetrated had the Germans maintained and heeded a moderately consistent review of the English-language press; and it is a rather extraordinary fact that such a review, supplemented by information from other sources concerning the Canadian formations, exists among the captured German documents.60 It is interesting also that the Germans failed to record the movement of Canadian formations into the toe of Kent, which had apparently been ordered as part of the Allied deception plan. Their D Day map showed the 2nd Infantry Division at Bognor and the 2nd Canadian Corps in East Sussex. Nevertheless, one of their few agents in England had reported the 2nd Division’s headquarters in the Dover area on 22 May.61

Seven weeks after D Day, Foreign Armies West lamely confessed that it had come to the conclusion that one Canadian infantry division and two Canadian armoured divisions (!), heretofore believed to be overseas, were in fact still in Canada. It explained that the information of their movement to Britain had come from “a reliable source”, their serial numbers being given; it was now assumed that in fact it was only drafts of reinforcements that had moved.62 Unfortunately for the reputation of Foreign Armies West, the three serial numbers which it had obtained somewhere, and believed to be those of divisions, actually belonged to the 21st Armoured Regiment (The Governor General’s Foot Guards), the 4th Medium Regiment RCA, and the 1st Battalion of the Algonquin Regiment.

Some information did reach the enemy. Before D Day he knew the approximate locations of all the British assault formations; the 3rd British, 3rd Canadian and 50th Divisions appear on his map in the Portsmouth-Southampton area. On 22 May the Commander-in-Chief West pointed to this area as “a focal point of preparations”.63 But the paucity and inaccuracy of the intelligence reflected in the German reports justify the generalizations that the enemy got remarkably little accurate information out of England, and that he did not make particularly good use of what he did get.

The Final German Preparations

From the beginning of 1944 until the day of the invasion the Germans sought desperately to strengthen their defences in both men and materials. Construction of the Atlantic Wall fell far behind schedule, particularly as the Allied air forces and the French Resistance stepped up their attacks on the French railways. Thousands of men were taken from work on the fortifications to repair bomb damage.64 This chronic lack of resources also helped to prevent Rundstedt from developing a second line of defence in rear of the coast. He had ordered the construction of such a line in the previous October; but General von Salmuth immediately raised the question of where the labour was to come from; and in April 1944 Rommel ordered work on the second line discontinued.65 Thus the defences on the shores of Normandy remained a coastal ribbon, entirely without

depth. Demands were continually being made for materials and explosives for the shoreline obstacles and mines, but the number of these provided was but a small part of what was considered necessary.

During the winter new divisions had been formed from training and replacement establishments and surplus air force personnel, from the remnants of formations destroyed in the East, and anywhere else the men could be found. Some few of the static divisions had their status raised to that of infantry divisions with some capacity for attack. There had been by the end of 1943 some movement of coastal divisions to strengthen the Fifteenth Army’s sector and the right wing of the Seventh Army, that is along the Channel from the Dutch border to the Cherbourg Peninsula.66

It proved impossible to carry out Hitler’s direction that there was to be no further movement of troops out of the West. Of the few armoured divisions which had been nurtured and were coming up to strength, the whole of the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, comprising the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions, was rushed from France in March 1944 to meet a crisis in the East. The 1st SS Panzer Division which had been intended for the West was kept on the Russian front until it suffered such heavy losses that it was brought to Belgium for rehabilitation. The Panzer Lehr Division, formed from training establishments, had to be sent to Hungary when that country was occupied in March, but when the situation there had settled in May it was able to return to France. The Hermann Göring Panzer Division which had been promised from Italy was kept there after the Anzio landings.67 The West thus had but little armour at the time when Allied preparations were reaching their height.

When the Russian spring offensive subsided, the moves to the East were stopped.* By the beginning of June the mobile reserves in the West had been built up to nine armoured divisions, three of which were still being formed, and one motorized division which was also still incomplete. The dispute about the disposition of these reserves was never settled. Hitler vacillated between the conflicting views of Rommel and Rundstedt until eventually he compromised by dividing the mobile divisions. Three (the 2nd, 21st and 116th Panzer) were given to Rommel, three were with Armeegruppe G in the South (including one directly under the First Army), and four, as we have seen, were retained in OKW reserve.68

The final location of these armoured formations, whether under Army Group B or in OKW reserve, reflected a sudden and belated interest in Normandy, rather than the Pas de Calais, as the most likely invasion area. Hitherto, the Fifteenth Army’s sector had received the greater share, in both quantity and quality, of the resources available; but late in April and early in May Hitler insisted on strengthening the Seventh Army’s sector in Brittany and Normandy, including the Cherbourg peninsula. The origin of this new attention to Normandy—whether it was information from CICERO, or mere intuition, or something else—remains problematical. It is worthy of note, however, that Hitler seems to have

* The Soviet summer offensive began only in the fourth week of June.

emphasized the menace to the Cherbourg and Brest areas rather than the beaches where the first landings actually took place.69

[Footnote reference 70 is missing]

In April, the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitlerjugend) was moved from Belgium to Normandy and placed some fifty miles behind the coast between Elbeuf and Argentan. The Panzer Lehr Division was in the triangle Le Mans–Chartres–Orléans. These two divisions were in OKW reserve. The 21st Panzer Division, under Army Group B, was in the Caen area by 6 May, with some of its units very close to the coast (below, page 67).71 Thus three of the five panzer divisions ready for action in northern France were within one hundred miles of the invasion sector. The remaining two were north of the Seine, between Rouen and Doullens.72

It is interesting that early in May Rommel recommended that a good part of the armoured OKW reserve be moved up to the Normandy-Brittany sector, and his request was refused. On 29 April the C-in-C West issued an order informing his subordinates of his belief that the Allied assault was now close at hand. He added emphatically, “All movements and regroupings must now end!”73 Rommel nevertheless made his submission some days later. It is thus recorded in the C-in-C West’s war diary under date of 4 May:

The Commander-in-Chief of Army Group B has reported that in his view the best way to strengthen the defence potential of Normandy and Brittany is to move up and bring under command the [following] High Command Reserves: Corps Headquarters 1st SS Panzer Corps, Panzer Lehr Division and 12th SS Panzer Division.

C-in-C West cannot concur in this premature commitment of the sole and best operational reserves. This in order to safeguard the possibility of moving them quickly and at all times to any threatened sector.

C-in-C West reports to OKW in this sense.

In a retrospective I-told-you-so memorandum dated 3 July Rommel stated that “at the end of May, when the threat to Normandy became apparent” he asked that 12th SS be moved to the Coutances–Lessay area south of Cherbourg, and Panzer Lehr to an (unspecified) position where it could strike immediately against landings either in Normandy or Brittany; these requests were, he said, refused.74 It seems possible that he was writing from memory and was actually referring to this incident early in May.

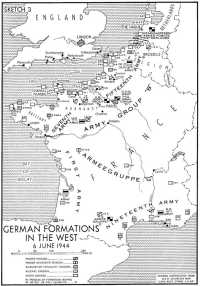

Along the coast or close behind it. Army Group B had 32 “non-mobile” divisions of varying types and quality. Of these 18 were under Fifteenth Army, 11 under Seventh Army and three in the Netherlands. Thirteen such divisions were in Armeegruppe G. In all, in the West at the beginning of June there were 58 divisions of all types. One of these was moving to Italy, and 11 were being formed or rehabilitated.75 (See Sketch 3.)

As summer drew on the Germans studied in vain the pattern presented by tide tables, Allied bombing and coded radio messages to the French “underground”. The area of assault remained uncertain, for the recent attention to Normandy was far from decisive. The last weekly situation report issued by the Commander-in-Chief West before D Day, dated 5 June,76 was notably noncommittal:

The centre of gravity between the Scheldt and Normandy is still the most probable focal point for the attack. The possibility of extension up to the north of Brittany, including Brest, is not excluded. Where within this entire sector the enemy will attempt a landing is still obscure. ... As yet there is no immediate prospect of the “invasion”...

On the timing of the invasion, indeed, the Germans were quite at sea. On 4 June Admiral Krancke, Commander Naval Group West, very incautiously committed himself to the opinion that Allied measures were “a well calculated mixture of bluff and preparations for invasion at a later date”.77 The German Naval Operations Staff, with its usual penetration, was more realistic. The messages from Britain to the French Resistance led it to conclude that invasion by 15 June “at the latest” was probable; although it added that this signalling might possibly be for training purposes.78 There is some reason to believe that on or about 3 June the senior Gestapo official in Paris made strong efforts to convince the military that the invasion was actually imminent. If this is true, he failed, and it is evident that the German commanders did not regard 5-6 June as a particularly dangerous period. On invasion night Field-Marshal Rommel was at his home in Germany, on his way to see Hitler.79

It has sometimes been argued80 that German weather forecasting was less efficient than the Allies’, and that this contributed to our achievement of surprise on D Day. This does not seem to be true, at least in any important degree. We now have the German weather forecasts, and they do not differ significantly from our own, particularly with respect to the improvement early on 6 June which was so vital an element in our calculations (below, page 89). Regierungsrat Muller, Liaison Meteorologist at Rundstedt’s headquarters, forecast at 5:30 p.m. on 5 June that departure flights from British airfields that night would be “on the whole possible without serious difficulties”, and that both the wind and the sea in the English Channel would fall somewhat “towards morning”.81

The Defences of the Normandy Coast

Almost the whole of that part of the Normandy coast through which the Allies chose to break into France was held by the right wing of Colonel-General Friedrich Dollman’s Seventh Army.* The coastline from Avranches around the Cherbourg peninsula (the Cotentin) to the eastern side of the Orne estuary, as well as the Channel Islands, was the responsibility of the 84th Infantry Corps under General of Artillery Erich Marcks. The garrison of the Corps sector consisted of the heavily reinforced 319th Infantry Division, with a battalion of tanks, locked up in the “fortresses” of the Channel Islands; the 243rd Infantry Division in the north-western portion of the Cotentin; and the 709th Infantry Division in Cherbourg and along the east coast as far as the western side of the Vire estuary. The 352nd and 716th Infantry Divisions shared the long front between the Vire and the eastern side of the Orne estuary.82

With the exception of the 352nd, which had been inserted between the 709th

* The British airborne descent east of the Orne fell in part upon the extreme left flank of Colonel-General Hans von Salmuth’s Fifteenth Army, held by the 711th Infantry Division under the 81st Corps.

Sketch 3: German Formations in the West, 6 June 1944

and 716th in March 1944, all these divisions were static. The lower western side of the Cotentin was in the hands of a miscellaneous group of East Battalions and training units. An independent battalion of tanks had been stationed on Cap de la Hague, the promontory north-west of Cherbourg.83 Early in May, when the Germans became concerned about Normandy, particularly the peninsula, they put in the 91st Air Landing Division and the 6th Parachute Regiment as an Army Reserve between Valognes and Carentan, and as far south as Périers.84

The main blow of the invasion was, therefore, to fall on the 352nd and 716th Divisions, and on the southern elements of the 709th. The area had been belatedly and, as it proved, inadequately reinforced. Two divisions instead of one now held the coast between the Vire and the Orne, but it was a very long front. As early as December 1942, when the 716th Division was responsible for the whole of it, the Divisional Commander had written, “major landings in the sector are improbable”.85 This view, supported by naval opinion, does not seem to have changed during the following year and a half.86 It was apparently based chiefly on the existence of the offshore shoals, although these were not in fact a hindrance to small craft at high tide.

The area assaulted by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was a part of the “Coastal Defence Sector Caen”, which was held by the 716th Infantry Division commanded by Lieut.-General Wilhelm Richter. This division, formed in May 1941, had been in the Caen area since March 1942. As just noted, it was responsible for the whole front between the Vire and the Orne until March 1944, when the 352nd Division took over the left sector. The 716th thereafter held the coast from (but excluding) Asnelles to Franceville Plage on the east side of the Orne estuary, a distance of approximately 19 miles. Divisional Headquarters was at Caen.87

The 716th Infantry Division was a static formation. Its ration strength on 1 May 1944 was 7771 all ranks.88 It had only two infantry regiments: the 726th (of which moreover the headquarters and two battalions were under the 352nd Division) and the 736th. In addition it had two East Battalions (above, page 52). Of the four sub-sectors into which its front was divided, the most westerly (from the divisional boundary to just west of Graye-sur-Mer) was held by the 441st East Battalion plus one company of the 2nd Battalion of the 736th Regiment. The single battalion of the 726th Regiment was in immediate reserve behind this sector. It was unusual to put an East Battalion in the line, but it appears that the 441st was considered unusually reliable. (It nevertheless ran away on D Day.) The left central sub-sector, including Courseulles and Bernières, was held by the 2nd Battalion of the 736th with two of its three available companies on the beach and the third in reserve. The right central sub-sector, including St. Aubin and Lion-sur-Mer, was held by the 3rd Battalion of the 736th with two companies on the beach and two in reserve. The most easterly sub-sector fell to the 1st Battalion of the 736th, again with two companies up and two in reserve. In this area also was the greater part of the 642nd East Battalion; it appears to have had one company on or near the beach in the Franceville strongpoint, but it is reported that two other companies were scattered across the division’s front on construction work.89

It is thus evident that Richter’s 19-mile divisional sector was comparatively weakly held. Of his six infantry battalions, two were of doubtful quality and only one did not have a good part of its strength deployed directly in the beach area. On the other hand, the prepared defences compensated in some degree for the weakness in personnel, and important reserves were close at hand. Several mobile units of the 21st Panzer Division were stationed in the 716th Division’s area. Two panzer grenadier battalions and the divisional anti-tank battalion were spread across the sector some five miles inland. A reinforced company of one of these panzer grenadier battalions was stationed in field positions south of Lion-sur-Mer under the 716th Division’s command. The 21st Panzer Division as a whole was, as we have seen, in Army Group B Reserve. None of its tanks was north of Caen.90

In artillery the—716th Division sector was strong, even though almost all the guns were French, Czech, Russian or Polish. The divisional artillery amounted to three battalions, but of the heavy battalion only one battery (six 15-centimetre—5.9-inch howitzers) was present, the rest being under the 352nd Division. The other two battalions consisted of four batteries each; one of the eight batteries was with the 352nd Division. In addition, a motorized battalion (three batteries) of the 21st Panzer Division artillery was stationed in the 716th Division sector and was under General Richter’s tactical command;91 there were also a GHQ heavy artillery battalion of three batteries, and two batteries of a GHQ coast artillery battalion (see below). All told, there were in the divisional sector 16 batteries of artillery, armed with a total of about 67 guns of calibres ranging from 10-cm. to 15.5-cm.* This does not include anti-tank guns or the guns in the beach defences (below).92

The 716th may be accounted a better-than-average static division. Rundstedt in his report of October 194393 had described it as “mobile under certain conditions (to be motorized)”. It had not been motorized, but since the date of Rundstedt’s report its artillery had been strengthened and a second anti-tank company had been organized. The Field Marshal had characterized its state of training as “Good; not uniform, owing to an exchange of age classes and detachments”. His general comment on it was, “Completely fit for defence”. It may be said that on D Day the Division justified his statement. Heavily outnumbered and smitten by a tremendous weight of metal by land, sea and air, it nevertheless contrived to give a good account of itself. It was the first of the many German formations, officially accounted by our Intelligence as of inferior quality, which gave us serious trouble during the campaign in North-West Europe.

The fortifications in the Caen sector,† as on other parts of the coast, fall

* One battery whose strength in guns is not stated has been assumed to be of four guns. A German batterie (roughly equivalent to a British or Canadian troop) was normally of four guns.

† This account derives mainly from three sources: reports prepared after the invasion by the (British) Army Operational Research Group and by Combined Operations Headquarters,94 both in part on the basis of examination of the defences by experts; and a detailed German map of the dispositions in the 716th Division sector,95 which unfortunately suffers somewhat from having been compiled after the assault. Some use has also been made of the excellent Allied maps of the enemy defences prepared, mainly on the basis of air photographs, before the assault.

into two main categories: the installations housing the coastal and field batteries, and the beach defences proper.

The most massive defences were those of the batteries, but these were also the least complete on D Day. The batteries were installed at various distances from the coast, but most of them were within two miles of it. There appear to have been only two completed concrete battery positions in the 716th Division’s area on 6th June, both of them manned by units of the divisional artillery and each mounting four Czech 10-centimetre howitzers; one was at Merville on the right flank and the other at Ver-sur-Mer on the left. The heaviest weapons in the divisional sector were 15.5-cm. French guns; a battery of four of these was manned by the divisional artillery in half-completed concrete positions south-west of Ouistreham. It was found, however, that these guns had been removed before D Day, possibly to alternative positions in rear. There were in the sector only two batteries manned by GHQ coast artillery units (batteries of the 1260th GHQ Coastal Artillery Battalion): four 12.2-cm. Polish guns at Mont Fleury (one under concrete on D Day, the others in open positions behind); and four or perhaps five 15.5-cm. French guns in unfinished positions south of Riva Bella on the right flank. The great majority of the guns in the sector were in open field positions. One such battery which received rather disproportionate attention in Allied reports was the four 10-cm. guns near Beny-sur-Mer (also spoken of as the Moulineaux battery).96

As for the beach defences proper, these were not and could not be continuous. They took the form, normally, of a series of “resistance nests” (Widerstandsnester)—defended localities well sited immediately above the beaches and commanding them. These localities were placed close enough to each other to ensure that so long as they remained in action no enemy could land at any point on the beach without coming under small-arms fire. On ordinary sections of the 716th Division’s front the average distance between them was approximately 2000 yards. While there was considerable local variation, the pattern of these resistance nests was fairly standard. In some cases they centred on a massive concrete pillbox or casemate (with seven feet of concrete on the roof and seaward side) mounting a 50-, 75- or 88-mm. gun which was invariably sited to fire down the beach in enfilade, usually in only one direction. The embrasures of these works were protected from fire from seaward by heavy “buttresses” which proved effective on D Day, the more so as our Intelligence had not been able to inform the Navy of this feature. In half a dozen cases 50-mm. anti-tank guns were mounted in rather lighter concrete shelters, shielded from seaward but open on the land side and able to fire down the beach in both directions.* These various concrete structures were surrounded and supplemented by trench systems and mortar and machine-gun positions which were often of the “Tobruk” type, i.e. concrete-lined pits with their upper edges flush with the ground. Additional 50-mm. guns were sometimes found in open concrete positions. The localities as a whole were well protected with mines and wire. Each was usually designed to be manned by an infantry platoon.97

* For illustrations of typical positions, see facing pages 51 and 114.

At certain points considered to be of special importance (and this included all harbours, even the most minor) the defences were thickened up with more concrete and additional artillery and other weapons to form “strongpoints” (Stützpunkte). Sometimes a battery position was included within one of these strongpoints or was close enough to it to form a single defended area.98

On the basis of examination by British operational research investigators after the assault, the total number of guns mounted in the beach defences on the front attacked by the three British and Canadian infantry divisions was 25: two 88-mm., seven 75-mm., fourteen 50-mm., and two 37-mm. Of these, one 88, three* 75s and six 50s were on the beaches assaulted by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.99 Among other weapons in the defences, the 8.1-cm. mortar seems to take pride of place on the basis of casualties inflicted on us on D Day. There appear to have been 11 of these mortars on the British and Canadian fronts, chiefly mounted some distance inland from the beaches.100 Beach-defence weapons also included a few electrically-fired static flame-throwers, none of which came into action on D Day.101

Heavy mining, integrated with the beach defences, had been completed to a depth varying from 300 to 800 yards inland, particularly at possible exits from the beaches. There had been no mining of the beaches themselves, although almost all the foreshore obstacles had mines attached to them. These obstacles were in belts as far as 1200 yards from the high water line. Lack of materials and time restricted the number that could be prepared. The foreshore obstacles varied in type and density at different points. In general they were sited within the upper half of the tidal range and were all submerged at high tide. A normal pattern of arrangement was, starting from seaward, first, rows of wooden or concrete stakes; ramps of logs or steel rails driven into the sand at the seaward end and raised some six feet at the other; “tetrahedra” (pyramid-shaped obstacles formed of three concrete, steel or wooden bars); and “hedgehogs” (obstacles made of three lengths of heavy angle-iron bolted together at their centres to form a large double tripod). In some areas, including those around Courseulles and Bernières in the Canadian sector, there were also what were known as “Belgian gates” or “Element C”—sections of the steel anti-tank obstacle which Belgium had erected in pre-war days along her frontier with Germany. All these obstacles were frequently armed with Tellermines (anti-tank mines) or artillery shells fitted with pressure igniters. The Germans hoped that they would prevent the approach of landing craft or damage or destroy those which persisted in the attempt to beach.102

It remains to describe in some slight detail the defences of the beaches which were attacked by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on D Day. These beaches extended from Graye-sur-Mer on the west to St. Aubin-sur-Mer on the east, both inclusive.

In this area the heaviest defences were those of “Stützpunkt Courseulles”, guarding the small harbour of Courseulles-sur-Mer. The east side of the harbour

* The operational researchers seem to have included one of these, in the casemate north of Vaux (below, page 70) known as “La Rivière 1”, in the 50th Division sector.

entrance was covered by a casemated 88-mm. gun and a 50-mm. anti-tank gun. About 500 yards to the east another concrete emplacement housed a 75-mm. gun. Six machine-gun posts were also embedded in this short stretch. On the west side of the harbour entrance between the sea and the loop of the River Seulles there were another 75-mm. and two 50-mm. anti-tank guns. The smaller weapons here consisted of six machine-guns and two 5-cm. mortars. The next 75-mm. casemate was about 1300 yards farther west, at a point north of Vaux, the western limit of the Canadian beaches.

Between Courseulles and Bernières a German map shows a resistance nest, and Allied maps based on air photographs show construction activity here; but it would seem that no active position existed at this point. In the resistance nest at Bernières itself the main defences were in front of the town along the sea-wall, which was from 6 to 10 feet high. There were one log and one concrete 50-mm. gun emplacements, and seven concrete machine-gun posts. Back from the beach about 150 yards were two 8.1-cm. mortar posts. At St. Aubin there was a resistance nest at the west end of the village which had “exceptional command of the beach”; it possessed a 50-mm. gun, several machine-gun posts, and apparently three 8.1-cm. mortars sited a short distance back from the beach.103

As already indicated, the defences were almost entirely without depth. They were a coastal ribbon; prepared defensible positions in general existed in rear only at battery sites or where headquarters or unit billets had been dug in. One inland position in the Canadian sector however requires notice. Just west of Douvres-la Délivrande the Luftwaffe had built and strongly fortified a radar station. Here there were two strongpoints surrounded by minefields and wire, guarded by weapons including six 50-mm. guns, 16 machine-guns and three heavy mortars, and garrisoned by “about 238” men of the German air force.104 This fortress, some three miles inland from the beach, was to distinguish itself by resisting until eleven days after D Day.