Chapter 5: The Landings in Normandy, 6 June 1944

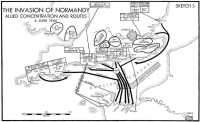

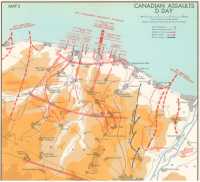

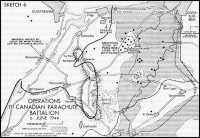

(See Maps 1 and 2 and Sketches 5 and 6)

Forth to Normandy

The high historic moment towards which so many months of effort had been directed was now at hand. On the morning of Monday the 5th the tremendous assembly of loaded craft in the ports on the south coast of England began moving towards France.

The first British groups sailed from the Portsmouth area about nine in the morning, and from then on ships were steadily passing out through the channels east and west of the Isle of Wight. Simultaneously the American assault forces were sailing from the ports farther west. During the afternoon the leading groups of Forces G, J and O arrived in the assembly area known as Area Z (PICCADILLY CIRCUS) south-east of the Isle of Wight, and began making their way through the pre-arranged channels provided for them in the barrier of German minefields which interposed between our forces and the Normandy beaches.1

The minesweepers whose task it was to breach this barrier had sailed earlier. Their job was ticklish and dangerous. One of the units allotted to it was the 31st Canadian Minesweeping Flotilla, and other Canadian minesweepers served in British flotillas; sixteen in all were taking part. Long before dusk on Monday evening the sweepers were within sight of the coast of France; before darkness fell, it is recorded, the crews of one of the British flotillas could distinguish individual houses on shore. It had been fully realized that the minesweeping operations might compromise the security of the operation, but this risk had had to be accepted. Whether or not the Germans failed to observe the minesweepers, the fact remains that they were not fired upon by shore batteries or attacked by aircraft. The flotillas duly completed their task, cutting a considerable number of mines and marking the ten swept channels with lighted buoys. Some of the Canadian sweepers were within a mile and a half of the French coast during the dark hours of the morning of 6 June.2

Since about midnight on the night of 4-5 June, two British midget submarines (X23 and X20) had been in assigned positions close to the enemy shore. They were to flash coloured lights to help guide the assault forces in, and in particular to mark the points where Forces J and S were to launch their DD tanks

They had duly received the signal announcing the postponement and spent Monday on the bottom. On the morning of D Day these two little craft, the first Allied vessels to arrive in the assault area, carried out their allotted task, except that the weather was too rough to permit them to launch the dinghies which were to have marked separate points, including the launching position for the DD tanks for the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade’s beaches.3

Commodore Oliver, commanding Force J, was flying his broad pendant in the headquarters ship Hilary, which had served the 1st Canadian Division in the same capacity for the assault on Sicily. Embarked with him were Generals Crocker and Keller, with the headquarters of the 1st British Corps and the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. HMS Hilary passed out through Spithead Gate, between No Man’s Land Fort and Horse Sand Fort, at 7:25 p.m. on 5 June.

The wind did not stand fair for France. The Channel was rough, with waves five to six feet high in the open sea; conditions “most severe for loaded landing craft”. The improvement foretold by the meteorologists had not yet fully materialized. The landing ships and craft tossed and pitched; many soldiers and some sailors were miserably sick. But with only relatively minor exceptions the night’s voyage proceeded according to plan. Certain groups of craft got into the wrong marked channels through the minefield; one of these was Group 312, carrying the engineer assault vehicles for the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade. Generally speaking, Oliver reported, “Owing to the weather landing craft groups had difficulty in maintaining their planned speeds of advance, low though these were.” This was to have its due effect upon the assault. But one fact overshadowed all others. At the time it seemed hard to believe, but “No offensive action by enemy air or surface forces was encountered by Force J during the passage.”4

Operation NEPTUNE Begins

As we have already seen, the air forces’ part in the great invasion had begun many months before D Day. However, in terms of the actual assault, NEPTUNE—and OVERLORD—may be said to have commenced at 11:31 p.m. on 5 June, when the RAF Bomber Command began its attack upon the ten selected coastal batteries. About three-quarters of an hour later the advanced guards of the Allied armies came into action, when the first men of the British and American airborne divisions came down on the soil of Normandy.

On the US flank, the first soldiers in France appear to have been men of the Pathfinder Group of the 101st Airborne Division, who are reported to have come down at 15 minutes past midnight.5 It seems likely, however, that the first Allied soldiers who actually fought in Normandy were six platoons of the 2nd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry who landed in the first wave of the 6th Airborne Division on the British flank. These platoons, carried in gliders, constituted along with a party of Royal Engineers a “ coup de main force” which had the vital task of capturing intact the two bridges over the Canal de Caen a la Mer and the Orne River near Benouville. The gliders were due to land

Sketch 5: The Invasion of Normandy. Allied Concentration and Routes. 6 June 1944

at 20 minutes past midnight, and they did so. With a single exception,* they came down very close to the bridges. The men of the Oxford and Bucks—worthy successors of the famous 52nd of Wellington’s army—immediately rushed and overpowered the German defenders. The bridges thus seized were to be important in a later stage of the campaign.6

Simultaneously with the coup de main party the first Canadian soldiers descended on French soil. They were C Company of Lt.-Col. G. F. P. Bradbrooke’s 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, who jumped by parachute along with the advanced party of the 3rd Parachute Brigade. The company was to secure and protect the dropping zone near Varaville which was planned for the main body of the Brigade.7 As we shall see, the tasks of the Canadian company and battalion, as of the Division at large, were in general carried out, but not strictly according to plan (below, pages 116-17).

Thus before the sixth of June was half an hour old the great operation had been launched and important progress had been made. And something we had scarcely ventured to hope for had happened. The Germans had been taken by surprise.

Bombardment by Air and Sea

The attack on the chief coastal batteries which the RAF Bomber Command launched half an hour before midnight on the night of 5-6 June was, in terms of weight of bombs, the heaviest blow the Command had ever struck. It went on until 5:15 a.m., and during this period 5268 tons of bombs were dropped and the Command made 1136 individual sorties. The targets, from west to east, were batteries at La Pernelle, Crisbecq, St. Martin de Varreville, Maisy, St. Pierre du Mont, Longues, Mont Fleury, Ouistreham, Merville/Franceville and Houlgate.8

In this bombardment No. 6 (RCAF) Bomber Group played an important part, sending out 230 aircraft and dropping 859 tons. Its targets were Merville/Franceville and Houlgate, which were exclusively attacked by the RCAF Group, and Longues, where about one-third of the attacking force was Canadian. In addition, 16 Canadian pathfinder aircraft went out. Only one Canadian aircraft was lost. The results of the attacks were spotty. At Merville the markers quickly disappeared in dense low clouds, and in fact the battery was not hit.9 At Longues also the bombardment was considered ineffective; yet a naval report based on examination of it after its capture states that the bombing was “remarkably accurate”.10 At Houlgate the attack was considered precise and well-concentrated. Both these batteries seem to have fired on D Day, though ineffectively.11

As we have already noted, at dawn the Eighth US Air Force took up the bombardment in its turn. In the thirty minutes immediately before H Hour, 1083 heavy American bombers (out of 1361 dispatched) attacked the coastal defences, dropping 2944 tons. Here, as at so many points in the operation, the weather made itself felt. It was necessary to bomb by instruments through the

* One of the gliders intended for the Orne bridge landed seven miles away, beside a bridge over the Dives. This platoon rejoined its unit on 8 June.

overcast. There was natural anxiety to avoid hitting our landing craft as they closed the beaches. Accordingly, “in the interest of greater safety and with Eisenhower’s approval, pathfinder bombardiers were ordered to delay up to thirty seconds after the release point showed on their scopes before dropping. The danger of shorts was stressed in all briefings.” The result of this thoroughly laudable caution was that the Americans’ main concentrations fell “from a few hundred yards up to three miles inland” and “the beachlines from OMAHA east were left untouched”.12 The defences both on OMAHA and on the British and Canadian beaches remained almost intact. This was unfortunate, but it would have been still more unfortunate had the bombs come down among our landing craft.

The heavy attacks on various selected targets delivered by the fighter-bombers and light and medium bombers of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force began about the same time as the US heavy bomber operation and no doubt contributed very considerably to disorganizing and demoralizing the defenders. It is questionable however whether they did much actual damage to the beach defences, except possibly in the case of the medium attacks in the UTAH area, made visually, which were much more accurate than those of the heavies. Precise assessment of the attacks’ effectiveness seems impossible.13

The naval programme of Counter-Battery Fire began, as noted in describing the plan, about the same time as the US heavy bomber attack. It was on a tremendous scale. The major bombardment ships in the Western Task Force (i.e., in the US sector) amounted to three battleships, one monitor, and ten cruisers (of which two were in reserve). In the Eastern Task Force there were three battleships (of which one was in reserve), one monitor and 12 cruisers (including one in reserve). In addition one battleship (HMS Nelson) was held back as a spare unit for either task force.

In the British sector the heavy bombarding ships for the counter-battery tasks were organized in three Bombarding Forces. Of these the largest was Bombarding Force D, composed of the battleships Warspite and Ramillies, the monitor Roberts and five cruisers. This force was to deal with the formidable batteries on the eastern flank of the assault area and south of the Seine. (The heaviest batteries which could bear on the assault area were those at Le Havre, which included guns up to 15-inch. These batteries would, however, it was hoped, be neutralized by bombing before D Day, and in fact they do not appear to have interfered with the assault and no naval fire had to be directed at them.) Bombarding Force K was attached to Assault Force G and consisted of four British cruisers and a Dutch gunboat. The weakest of the three British Bombarding Forces, E, was that attached to Force J. It consisted of the cruisers Belfast and Diadem, which were (rightly, as it proved) considered sufficient to deal with the weak batteries in the Canadian divisional sector.14 The only batteries actually scheduled for bombardment by Bombarding Force E before H Hour were those at Ver-sur-Mer and Beny-sur-Mer (see above, page 68), which were duly engaged by Belfast and Diadem respectively, beginning at 5:30 and 5:52 a.m.* The

* The voluminous naval reports appear to contain no list of the batteries actually engaged before H Hour, but references to individual batteries indicate that the programme actually carried out was very similar to that laid down in the Joint Fire Plan dated 8 April, which envisaged bombardment of 20 batteries from La Pernelle on the extreme right, far up the Cherbourg Peninsula, to Benerville on the extreme left, only a short distance west of Trouville.

destroyer Kempenfelt fired at an inland battery midway between Courseulles and Bernières at 6:19 a.m.15

The naval fire, carried out with the aid of spotting aircraft, was more effective than the heavy bomber attacks which, as we have seen, were seriously interfered with by the weather. On the whole there was surprisingly little opposition to the assault on the part of the German coastal batteries. The fact is that few of these positions had really been completed, either as to their protection or as to fire control and communication arrangements.16 The battery at Longues gave some trouble but was silenced by HMS Ajax which actually put 6-inch shells through the embrasures of two of the four casemates. The Mont Fleury battery was also silenced. The batteries at Benerville and Houlgate seem to have done some ineffective firing and were engaged by naval vessels a number of times during D Day and later; these batteries were outside the assault area and not exposed to early capture by the Army.17 But it is a remarkable fact that the German coastal batteries apparently did not score a single hit against our shipping on D Day. Admiral Ramsay summed the matter up as follows in his report:18

Fire from enemy coast defence guns was never effective, and was directed initially against the bombarding ships. Prior to the bombardment of Cherbourg [on 25 June], none of the bombarding ships received even one hit from shore-based guns. This is considered to have been due to the combined effect of the bombing of certain batteries carried out during the three months prior to D Day; to the heavy air bombardment of the larger coast defence batteries on the night of D-1 day; to the effect of the naval bombardment itself, and to the measures taken to prevent the enemy from ranging and spotting his fall of shot, by the use of smoke screens and radar counter measures. ...

In general, indeed, the failure of the Germans to strike, or even to attempt, any effective blow against the tremendous target offered by our shipping on D Day appears extraordinary. There was only one small naval enterprise that day. “Unfavourable tide and weather conditions” and the fact that “there were no indications of an enemy landing” had kept the German naval forces in harbour on the fateful Monday night. But at 3:09 a.m. Naval Group West received radar reports of ten large vessels stopped about seven miles off Port-en-Bessin (these were doubtless the landing ships of Force “0”, then engaged in lowering their landing craft). This in conjunction with the reports of airborne landings led Admiral Krancke to order his flotillas to sea. Three boats of the 5th Torpedo Boat Flotilla were sent out of Le Havre to reconnoitre the Port-en-Bessin–Grandcamp area (later altered to the Orne estuary); while the 15th Patrol Flotilla (six patrol vessels) likewise sortied from Le Havre to patrol off the port. About 5:15, according to British reports, or a little later according to the Germans, these two units encountered Bombarding Force D. The small German vessels were indistinctly seen against the land, and were obscured by a prearranged smoke screen laid by aircraft to cover the landing ships of the 3rd British Division from shore batteries. The British heavy ships opened fire and reported having sunk one torpedo-boat and one trawler. The German reports, however, establish that only

one vessel was lost—the patrol vessel VP 1509. The Germans fired 15 torpedoes. The smoke prevented them from observing the result. But they had taken their toll; one torpedo struck and sank the Norwegian destroyer Svenner.19 This ship and the US destroyer Corry, which was mined (and possibly also struck by shellfire) in the UTAH area,20 were the only major Allied warships lost that day.

The German naval forces in the Channel area were very weak, and no great effort could have been expected of them. More surprising was the complete failure of the German Air Force even to put in an appearance in the first hours of the assault. Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory reported that the first enemy air reaction on D Day was a reconnaissance of the Channel areas. The powerful fighter force (continuous cover by nine squadrons) which he provided over the assault area from dawn onwards met no opposition for many hours. Not until about 3:00 p.m. did the first German fighters and fighter-bombers appear: “This was nine hours after the assault began and fifteen hours after the first of very large formations of airborne transports and of the air bombardment squadrons had arrived over enemy territory.” The first real effort of the Luftwaffe was on the night following D Day, and it was weak. About 85 enemy aircraft were over the beaches and shipping lanes that night.21

Although the German Navy and the German Air Force made so little attempt to halt the advance of our ships and aircraft towards Normandy, the German Army did not fail to offer the resistance that had been expected of it. Our troops as they approached the beaches found the enemy ware and waking.

“Drenching” the Beach Defences

At dawn on 6 June the weather off the assault beaches was unpleasant. Admiral Ramsay’s report summarizes the conditions thus:–22

Wind—West-northwest—force 4.*

Sea—Moderate—waves 3/4 feet.

Sky—Fair to cloudy with cloud increasing.

Of all the assault forces, only U, landing on the eastern beaches of the Cotentin, had relatively sheltered water. “There was little to choose between conditions anywhere else along the coast.”23 The commander of Force J estimated the wind at first light as force 5, and remarked, “The weather conditions were hardly in accordance with the forecast.”24 Landing operations were possible, but the circumstances were still very nasty for small craft.

The assaulting infantry had crossed the Channel in infantry landing ships (LSI) which carried assault landing craft (LCA) swung from their davits. When they had reached the planned “lowering position” within striking distance of the French coast, these ships lowered the assault craft, and the latter carried the infantry in to the beaches. The American lowering positions designed to be out of range of shore batteries, were 10 to 11 miles from the beaches, whereas the

* An appendix to the report, dealing specifically with the assaults, says, “Wind West—Force 15 knots”.

Eastern Task Force positions were only seven to eight miles out. Thus the American assault craft had a longer run-in (which under existing conditions was bound to be uncomfortable); and since in addition the American assaults were to be about an hour earlier than the British, Forces “0” and U reached their lowering positions some three hours before the British assault forces. The flagships of the Naval Commanders of Forces U and “0” anchored at 2:29 and 2:51 a.m. respectively. HMS Hilary did not anchor until 5:58 a.m.25

Among the infantry landing ships bearing the assault brigades of the 3rd Canadian Division to France there were three (Invicta, Duke of Wellington and Queen Emma) which had helped to carry the 2nd Canadian Division to the raid on Dieppe in 1942.26 They were bound now on a mission that was to have a happier outcome.

Although as we have seen the roughness of the sea somewhat disorganized the various craft groups of Force J, it had not interfered with the voyage of the infantry landing ships, nor was it allowed seriously to interfere with forming up the assault forces at the lowering position. “The LSI groups arrived punctually”, reported Commodore Oliver, “and despite the rough weather the ships deployed neatly and anchored in good station. No time was lost in lowering and forming up the LCAs which proceeded to the assault in a resolute and seamanlike manner.” It is true that the Commodore also wrote, “The final approach of the Assault to the beaches was far from the orderly sequence of groups and timing which had been the rule during exercises.”27 The weather had been bad, but not quite bad enough to jeopardize the success of the operation.

Since the heavy bomber attack had been so ineffective, the programme of Beach Drenching Fire (above, page 75) was of tremendous significance to the success of the assault. Fortunately, this phase of the fire plan was on the whole very efficiently carried out. The comparatively light weapons used in it could not, in the nature of things, be expected to destroy concrete defences. It was hoped, however, that they would exercise a “neutralizing” effect, destroying or damaging the lighter defences and discouraging the defenders and forcing them to keep their heads down.

In this phase of the fire plan destroyers were important. General Keller subsequently described their fire as “accurate and sustained”.28 Two Canadian fleet destroyers, Algonquin and Sioux, played a part in the Canadian area; all told, 11 destroyers fired on the beach defences on the Canadian front.29 Their fire was supplemented by that of the 4.7-inch guns of the LCG(L) (above, page 7), of which two were allotted to each assaulting battalion’s area. They fired on the enemy strongpoints from the flanks until the assault craft actually touched down. The Allied Naval Commander singled out the LCG(L) as being of special importance, on account of the fact that, being able to operate closer inshore than destroyers, they were particularly valuable against concrete defences. The lighter support craft—LCS(L)—with their shallow draft, were able to work still closer to the shore, and their 6-pounders had considerable effect.30

The rocket craft—LCT(R)—seem to have been, on the whole, very effective; Commodore Oliver reported that they fired their salvoes “accurately and a little

early”. (The plan called for them to fire in two “waves”, at H minus 8 and H minus 5 minutes.) Their targets on the Canadian front were the four main strongpoints, each of which was fired upon by two rocket craft and a regiment of self-propelled guns.31 The Hedgerows (above, page 7) were less satisfactory. The little assault craft, LCA(HR), in which they were mounted, had to be towed. On the 7th Brigade beach on the right only one of the nine allotted arrived. Commodore Oliver reported, “The remainder had foundered or had had to be cut adrift before entering the swept assault channels, apparently because they were being towed at excessive speed for the rough weather prevailing.” On the 8th Brigade front, on the other hand, all nine reached their firing positions on time, “a fine performance”.32 Captain G. Otway-Ruthven, RN, the commander of Assault Group J.2, stated that they “were able to fire their bombs to very good effect”, four on NAN WHITE beach (Bernières) and five on NAN RED (St. Aubin).33

The Army’s own contribution to the drenching fire, as already fully noted, was provided by four regiments of self-propelled artillery. On the 7th Brigade’s front astride the mouth of the Seulles, the 12th Field Regiment fired on the strongpoint immediately west of the river, and the 13th on the similar one immediately east of it. On the 8th Brigade’s front farther east the 14th Field Regiment fired on the Bernières strongpoint and the 19th on that at St. Aubin. The two pairs of regiments were grouped as “12 Canadian Field Regiment Artillery Group” commanded by Lt.-Col. R. H. Webb of the 12th Field, and “14 Canadian Field Regiment Artillery Group” commanded by Lt.-Col.

H. S. Griffin of the 14th Field. Each of the four regiments was armed with 24 105-mm. guns embarked in six tank landing craft.34 The field regiments did their job well. According to Captain Otway-Ruthven, on the 8th Brigade beach the 19th opened fire at 7:39 and the 14th at 7:44. On the 7th Brigade’s front the 13th began ranging at 6:55 and all guns opened fire “soon after”. Captain A. F. Pugsley, RN, commanding Group GJ1, which landed the 7th Brigade, wrote later, with respect to the regiments on his front, “It was reported that their fire was good and on the correct target.” General Keller’s own opinion was that the self-propelled guns in general “put on the best shoot that they ever did”.35

As the assault craft moved towards the beaches, the artillery regiments fired steadily over the infantrymen’s heads. The craft carrying the guns approached the beach at a constant speed of about six knots. The guns were kept on the proper line by simply pointing the craft at the target area; the gunners corrected the range by dropping the elevation as the distance lessened. In each regiment fire was controlled by a senior officer embarked in the navigational motor launch which accompanied the craft group. Another senior officer in a support craft acted as regimental Forward Observation Officer, noting the fall of shot and reporting necessary corrections to the Fire Control Officer by radio telephone. The calculation was that each of the 96 Priests in the 3rd Division would fire some 120 rounds during the run-in. The storm of shell continued to fall for 35 minutes. It had been planned that when it ended, at the moment when the infantry were due to land, the

craft carrying the guns would be only some 2000 yards offshore. They now turned aside to await their turn to land.36

We shall see that the assaulting units complained of the ineffectiveness of the preparatory fire, and undoubtedly the actual damage done to the concrete defences was slight. The Royal Navy, always a severe critic of its own performance, remarked in an analysis of “Normandy bombardment experience” prepared in 1945, “A considerable number of medium and light gun positions, pillboxes, Tobruk-type positions, etc., received direct hits, but at a generous estimate not more than 14 per cent of a total of about 106 can be said to have been put out of action by naval gunfire, mainly from destroyers, LCGs and LCS(L).”37

The effect of the beach drenching programme was assessed in the report38 of a Combined Operations Headquarters Special Observer Party which examined the beach defences shortly after the assault. This contained the following passage:

Except in a few isolated cases where weapons had been put out of action by direct hits through the embrasures (it is not possible to establish the actual time when these were made) the beach defences were unaffected by the fire preparation. Reports have been received from all except S Beach that the defences generally were still in action when the fire plan had been completed, and while troops were being landed. Any neutralisation during the run in may have been due either to the morale effect of the bombardment or to the fact that until the leading waves were close in shore the defences could not bear or had insufficient range. All evidence shows that the defences were NOT destroyed. The majority of the defences appear to have been overcome eventually by infantry infiltration from the rear assisted by AVREs. and tanks. The majority of guns destroyed were put out of action by direct hits from AFVs. A number of guns were also destroyed by their crews by using special demolition charges.

The same report, however, testifies that there was a heavy concentration of fire along the sea front, even though the concrete defences were little damaged. With respect to St. Aubin-sur-Mer, for instance, the report runs, “In general the buildings along the sea front were 90% destroyed. By this is meant that the walls were breached and inner dividing walls and floor had collapsed. The destruction was such that the buildings were rendered untenable for snipers during the bombardment though they would have found suitable cover subsequently. The remainder of the town was estimated to be between 30% and 40% heavily damaged. The damage appeared to have been caused mainly by shell fire and was not due to fires.” There are very similar accounts of the other sectors.

No. 2 Operational Research Section, which worked with the 21st Army Group, made a detailed study of the work of the self-propelled artillery in the assault on the Canadian sector, questioning officers concerned and examining the target areas. In all cases the investigators found that the “maximum crater density” was “plus of the target” by 100 to 200 yards; in other words, the main weight of shells fell slightly inland of the strongpoints. In the case of the 13th Field Regiment the fire was reported correct for line; in the 12th and 14th Regiments’ sectors the main weight of fire was reported to have fallen slightly east of the target; the 19th Regiment’s shells “fell over an extremely large area approximately 700 yards wide and 300 yards deep measured from the forward line of defences”.

The effect of the rocket fire, which as we have noted was directed at the same targets as that of the army artillery, got some attention from the Combined Operations

Headquarters observers. At St. Aubin rockets were reported to have fallen somewhat to the west of the town; at Bernières, “in the area of defences” and along a belt approximately 300 feet back from the sea wall; at Courseulles East evidence of rocket fire was found distributed across the area with the main weight “well back from the beach”. At Courseulles West, where there were few buildings and therefore less evidence of fire effect, no definite report is made.

From all this it is evident that the effect of the drenching fire was moral rather than material. This means that it is quite impossible to measure it with precision. Nevertheless it was probably very considerable. A very large weight of high explosive shell came down in the general area of the beach defences immediately before the assault, and this bombardment continued for over half an hour. On balance, it seems likely that its effect on the morale of the defenders considerably eased the task of the assaulting infantry. The general conclusion of the operational researchers was: “It is safe to say that a degree of neutralization was achieved, as there were several instances of weapons which had ample ammunition and had not been fired. No individual element of the fire plan can be said to have had a material effect, but the self-propelled artillery in contributing to the cumulative effort which did produce a degree of neutralization, performed a most useful role.”

The actual value of the drenching fire is strongly suggested by what took place at one strongpoint which received none, Le Hamel in the 50th Division sector. In this case everything went wrong. The heavy bombers missed the strongpoint, as they did elsewhere, although there are some reports of bomb damage in the area. The regiment of self-propelled artillery which was to fire on this target was unable to do so since “both their Navigational ML and control LCT fell astern due to weather”; this regiment therefore fired on the same target as the regiment on its left, one motor launch controlling both. Three destroyers fired on the strongpoint, but “the enemy positions were protected against low trajectory fire from seaward”. The net result was that this strongpoint gave much trouble, and was not captured until 4:30 p.m. on D Day.39 The episode suggests that the drenching programme was actually very valuable.

The Assault on the Beaches

As has been explained, the times set for H Hour varied across the front of assault, those on the British beaches being later than in the American sector. The original H Hour on the Canadian front was 7:35 a.m. for the 7th Brigade and 7:45 a.m. for the 8th. However, the lateness of certain craft groups resulting from the weather caused the two Assault Group Commanders to defer H Hour ten minutes more in each case. Thus the final H Hour was 7:45 a.m. for the 7th Brigade and 7:55 a.m. for the 8th. This was unfortunate, in that the higher

* It should be remarked that this account is based entirely on naval evidence, since the war diary of the artillery regiment concerned makes no reference to the pre-landing shoot, and that of the infantry battalion concerned is vague. The naval reports however are quite categorical. It is worth adding that the fierceness of the resistance here may have been due in part to the fact that Le Hamel was held by troops of the 352nd German Division, which at this point overlapped the British front of assault.

tide made it more difficult to deal with the beach obstacles; to quote Commodore Oliver, “craft beached amongst the obstacles instead of short of them, and clearance of the outer obstacles was not practicable until the tide had fallen”. The obstructions, and the mines attached to them, were in fact to take a heavy toll of our craft.40

The combination of the rough sea, the obstacles and the enemy’s fire made an unpleasant prospect for the crews of the landing craft; but they were not daunted. In the words of Admiral Vian, “Their spirit and seamanship alike rose to meet the greatness of the hour and they pressed forward and ashore, over or through mined obstacles in high heart and resolution; there was no faltering, and many of the smaller Landing Craft were driven on until they foundered.”41

The fire that came down upon the leading craft as they ran in was actually much less than had been feared. As we have seen, there was not much firing by the heavy inland batteries, and of what there was little if any was directed at the ships of Force J. Nor were any enemy aircraft to be seen. As for the artillery weapons mounted in the beach defences, as already noted, they were so emplaced as to enfilade the beaches, and in almost all cases could not bear upon craft any distance offshore. In consequence, it was in the main only small arms and mortars that fired upon the approaching craft. Admiral Vian reported that opposition began to manifest itself only when the leading craft were about 3000 yards from the beach; and even then the fire was “only desultory and inaccurate”, except on SWORD Beach, where craft were damaged by mortar fire until about two hours after H Hour. Heavy fire directed at the craft while still afloat was in fact the exception rather than the rule; Commodore Oliver wrote, “In general, apart from some inaccurate mortar fire, very little shooting was directed on craft before touch down.”42 It was after the actual landings that really fierce opposition began to manifest itself.

In these circumstances, it was during the landing craft’s sojourn on the beach, and still more their withdrawal from it, that they suffered most of their casualties. The commander of Assault Group J.2 (8th Brigade) reported, “The LCAs. had had to beach amongst the Hedgehogs. Although no difficulty was experienced in steering the craft in through them, going astern out of them proved more difficult. A high percentage of LCAs. of all the three flights set off mines in this way, causing them to founder.”43 In Force J as a whole 36 LCAs. (25 per cent of the whole number engaged) were lost or damaged in the assault. The Force’s casualties in craft were thus reported by Commodore Oliver:

Sunk: 3 LCT(A)

Badly damaged: 2 LCT(3), 7 LCT(4), 7 LCT(5), 5 LCI(S), 2 LCS(M), 14 LCA

Damaged or disabled: 18 LCT(4), 8 LCT(5), 2 LCI(S), 22 LCA

In total craft lost or disabled, Force J’s casualties were by a small margin the heaviest in the Eastern Task Force, numbering 90 craft as against 89 for

Force G and 79 for Force S. Force G however had heavier losses in LCAs: 52—while Force S lost only 29.44

The orders for the operation conjure up a picture of groups of vehicles and craft going ashore in orderly planned succession. They called for the first landing to be made, five minutes before H Hour, by the two squadrons of DD tanks assigned to each brigade sector; these were to be launched from their tank landing craft well offshore and to swim in. At H Hour itself the plan called for two LCT groups to land on each brigade front: one carried the AVREs of the 5th Assault Regiment Royal Engineers, the other the tanks of the 2nd Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment and a proportion of armoured bulldozers manned by Royal Engineers. The Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment was equipped with Centaur tanks armed with 95-mm. howitzers, plus one Sherman tank for each troop. These tanks were not intended to fire during the run-in unless self-defence required it; their role was to land and engage targets that had escaped the main bombardment with observed fire from hull-down positions in the water.45

The assault companies of the forward infantry battalions were to hit the beach in assault landing craft five minutes after H Hour, by which time, it was hoped, the tanks and the engineers would have made some progress in clearing the obstacles and in overcoming such opposition as had not been beaten down by the bombardment. The reserve companies of the assault battalions were to land 15 minutes later, namely at H plus 20.46

This neat pattern was largely spoiled by the roughness of the sea, which in particular almost completely disrupted the plan for launching the DD tanks. On the 8th Brigade front no real attempt was made to swim them in; they came off their LCTs. close inshore behind the leading infantry. On the 7th Brigade front, the Senior Officer of Group 311, carrying the tanks, considered the weather too bad to launch them at 7000 yards from the beach as planned. However, when closer in he decided that launching was possible and the tanks were sent off. There was some confusion, and in the case of one squadron those tanks which reached the beach arrived after the assaulting infantry (see below). As for the AVREs, on the 8th Brigade front they were the first element to land, a little in advance of the infantry; but on the 7th Brigade beaches their LCTs., which were “straggling somewhat in their efforts to make up lost time”, were a few minutes behind the assault companies.47

The 7th Brigade’s Beach Battle

The 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, as we have seen, was to be landed by Captain Pugsley’s assault group on the right or western sector of the Canadian front. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, with one company of the reserve battalion (the 1st Battalion Canadian Scottish Regiment) attached, landed on MIKE RED and MIKE GREEN Beaches, west of the river-mouth at Courseulles, while The Regina Rifle Regiment landed on NAN GREEN immediately east of the river. The DD tanks of A Squadron of the 6th Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars) were to support

the Winnipegs, while B Squadron performed the same service for the Reginas. The 6th Armoured Regiment was commanded by Lt.-Col. R. J. Colwell.

There was some disagreement as to precisely when the DD tanks landed. Admiral Vian asserted that in all cases they arrived after the first landing craft touched down; but the weight of evidence supports the statement of Commodore Oliver that on the 7th Brigade front the tanks touched down first, “20 minutes before the infantry”, although it seems evident that this was the case on only one battalion sector.

What happened was this. After the decision not to launch the DDs at 7000 yards the craft proceeded towards the beach, “wasting” time so as not to arrive before the moment planned. When at a distance from the beach which Major J. S. Duncan, commanding B Squadron of the 6th Armoured Regiment, estimated at 4000 yards, the Flotilla Officer of the LCT flotilla, after consulting the squadron commander, decided to launch the tanks. All the 19 tanks of B Squadron left the craft; and when about 2000 yards from the beach the squadron commander gave the order to deploy into line. Fourteen of the tanks duly landed on the proper beach, in Duncan’s words, “somewhat later than was intended but still well in advance of either AVREs or Inf”. Another landed later some distance to the east.48 There seems no doubt of the tanks’ being the first element ashore, for at 7:58 a.m. The Regina Rifle Regiment’s headquarters received and logged from its B Company the code word POPCORN, meaning “DD tanks have touched down”. B Company’s message reporting its own touchdown was not logged until 8:15.49

A Squadron’s experience was less fortunate. The order to launch was longer delayed than in the case of B; it was given, according to the senior officer of Group 311, when the craft were about 1500 yards from the beach. “The launching”, he reported, “took too long, and the LCTs drifted down on the tide.” Major W. D. Brooks, the squadron commander, wrote, “All craft at this point were not in the proper formation for launching and all were being subjected to mortar and other enemy fire.” The chains holding the door of one LCT were shot away after one tank had been launched. Another craft with five tanks aboard landed them directly on to the beach. Only 10 tanks of A Squadron swam off the LCTs., and of these seven reached the beach. The commander of Group 311 states that they were six minutes after the assaulting companies.50 The war diary of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles confirms that the tanks were late; but an extremely warm letter from the Winnipegs’ Commanding Officer (Lt.-Col. J. M. Meldram) attests the value of the support they gave him in his beach battle.51

The two squadrons between them lost seven tanks during the run-in, the majority evidently as a result of the roughness of the sea. One was run down by a rocket craft, all but a single member of the crew being saved. One tank was sunk due to its canvas screen having been damaged by mortar fire. Most of the men in the sunken tanks were rescued, thanks to the tanks’ rubber dinghies.52

It seems evident from the accounts written by members of the 1st Hussars that the procedure followed by the tanks in most cases after touching down was to stop in the water on the seaward side of the beach obstacles, deflate, and open fire on

the nearest pillbox. While thus engaged a number were flooded and immobilized by the rising tide.53

The infantry’s experience on the right battalion front of the Canadian division was a mixture of good and bad. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles state that they touched down at

7:49 a.m., all three assault companies landing “within seven minutes of one another”.54 On the far right, C Company of the Canadian Scottish, which was prolonging the Rifles’ front here, reported that it landed with slight opposition, and the platoon which had the job of knocking out the 75-mm. casemate north of Vaux (above, page 70) approached it “only to find—thanks to the Royal Navy—the pill-box was no more”.55

Quite different was the experience of B and D Companies of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, a short distance to the left, whose task it was to deal with the western portion of the Courseulles strongpoint. The battalion diary remarked grimly, “The bombardment having failed to kill a single German or silence one weapon, these companies had to storm their positions ‘cold’—and did so without hesitation. B” Company met heavy machine-gun, shell and mortar fire beginning when the LCAs. were 700 yards from the beach. This continued until touchdown, and as the men leaped from the craft many were hit “while still chest high in water”.56 But the Little Black Devils were not to be denied. B Company, with the aid of the tanks, captured the pillboxes commanding the beach; it then forced its way across the Seulles bridge and cleared the enemy positions on the “island” between the river and the little harbour. The fierceness of the fight on the beach is attested by the report of the Special Observer Party which later examined the German positions: “Big guns in this area were probably all put out of action by close range tank fire, and the machine gun and mortar positions gave up when surrounded by infantry.” When the strongpoint was clear B Company had been reduced to the company commander (Capt. P. E. Gower) and 26 men. Gower, who had set a powerful example of leadership and courage as he directed the clearing of the successive positions, received the Military Cross. An assault party of the 6th Field Company Royal Canadian Engineers, which landed with the infantry, had similar losses; the company had 26 casualties during the day.57

D Company met less fierce opposition when landing, since it was clear of the actual strongpoint area. It had relatively little difficulty in “gapping” a minefield at La Valette and clearing the village of Graye-sur-Mer beyond it. When the reserve companies landed the beach and dunes were still under heavy mortar and machine-gun fire. A pushed inland towards Ste Croix-sur-Mer, starting at about 8:05 a.m., while C advanced on Banville. The latter place fell comparatively easily, but machine-gun fire held up the advance in front of Ste Croix. Assistance was asked from the 6th Armoured Regiment, which with “cool disregard” of mines and anti-tank guns beat down the opposition and permitted the advance to continue. By 5:00 p.m. the battalion was consolidated in and around the village of Creully.58

In dealing with the other half of the Courseulles strongpoint, east of the river, The Regina Rifle Regiment, as we have seen, had the advantage of the fact that their DD tanks reached the beach ahead of the infantry and in larger numbers

than on the Winnipegs’ front. Here as at most points, however, the results of the preliminary bombardment had been disappointing. During the planning the village of Courseulles had been partitioned into blocks numbered 1 to 12, each to be cleared by a designated company; at the same time, careful study of aerial photographs and maps had familiarized the troops with the ground to such an extent that, as the Commanding Officer (Lt.-Col. F. M. Matheson) said, “nearly every foot of the town was known long before it was ever entered”.59

The two assault companies (A and B) reported touching down at 8:09 and 8:15 a.m. respectively.60 A Company, which was directly opposite the strongpoint, immediately met heavy resistance. The strongpoint gave it a hard struggle, and Matheson testified that the help of the tanks of B Squadron of the 6th Armoured Regiment was invaluable. This observation is supported by the later examination of the German positions by the Special Observer Party, which reported, with respect to the 75-mm. position at the east end of the strongpoint, “The gun had fired many rounds (estimated 200 empties) and was put out of action by a direct hit which penetrated the gun shield making a hole 3” x 6”. ... It is probable that the gun was put out by a direct shot from a DD tank.” Similarly, the 88-mm. position by the riverside was reported as “probably silenced by direct hits with guns from DD tanks”, although the concrete and gunshield were marked by shells probably fired by destroyers and LCGs. The nearby 50-mm. gun’s shield had been pierced by holes “probably caused by aimed fire from tank at short range”. Of the strongpoint generally, the observers report, “The guns had fired a considerable quantity of ammunition and were put out of action by accurately placed fire from close range by tanks.”

When at last A Company had cleared the strongpoint after breaking through by “a left flanking attack”, its troubles were not over. It moved on to its next task without leaving any force in occupation, and the Germans promptly filtered back into the positions “by tunnels and trenches”. The work of clearance began again, with the assistance after a time of an additional troop of tanks. In the meantime, B Company, landing on the left of the battalion front east of the strongpoint, had met only slight resistance and had cleared a succession of the assigned blocks in the village. The fortunes of the reserve companies were similarly mixed. C reported touching down at 8:35 and moved inland without difficulty. D, on the other hand, met catastrophe. Coming in late (it reported touching down at 8:55), several of its craft were blown up on mined obstacles concealed by the rising tide. Only 49 survivors reached the beach. As the companies overcame resistance in their areas they pushed inland towards the village of Reviers, where the battalion gradually concentrated in the course of the afternoon; the last company to arrive was A, which had finally overcome the stubborn resistance in Courseulles. About 5:00 p.m. the Reginas began to advance southward from Reviers. Before 8:00 p.m. both Fontaine-Henry and Le Fresne-Camilly were in their hands.61

The 7th Brigade’s reserve battalion, the 1st Battalion of The Canadian Scottish Regiment, commanded by Lt.-Col. F. N. Cabeldu, found opposition still alive as

its three companies approached MIKE Beach about 8:30. The leading companies came under mortar fire on the beach, and one of them was held up there for some time while waiting for an exit to be cleared of mines. Soon after 9:30 the battalion was able to start its advance across the grain fields towards Ste Croix-sur-Mer. En route it picked up its C Company, which had landed in the assault wave. There were a considerable number of casualties from machine-gun fire during the advance, which was pushed with all possible speed. After dealing with snipers in Ste Croix the battalion continued its movement through Colombiers-sur-Seulles, passing through The Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Little or no opposition was now being encountered, and the Scottish could have gone farther, but under orders from brigade headquarters they dug in for the night around Pierrepont, with patrols out well in front of Cainet and Le Fresne-Camilly. The latter village had been taken over from The Regina Rifle Regiment.62

Delay in opening exits from the beaches on the 7th Brigade front prevented the field artillery from moving inland as soon as had been planned. In these circumstances, Lt-Col. Webb brought the guns of the 12th Field Regiment ashore about 9:00 a.m. and put them into action actually on the beach. Deployed side by side amid the confusion of men and vehicles, they opened fire in support of the advancing infantry. In the late afternoon the regiment was able to move to its planned gun area between Ste Croix and Banville. The 13th Field Regiment had landed somewhat later. The first battery to land established itself south of Courseulles. By evening the whole unit was in its designated position adjacent to the 12th Field Regiment’s.63

The Centaurs of the Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment had comparatively little to do on the 7th Brigade’s beaches. Some of the Centaurs were lost at sea, and others landed late. They received few calls for fire, though one troop, answering a request received through a 13th Field Regiment observation party, silenced a beach position which was harassing the Reginas.64

Because of the late landings and the state of the tide, which was higher than had been predicted, the arrangements made for clearing the beach obstacles were badly disrupted. This task was to be shared by army engineers and special naval parties. Little could be done, as it turned out, until the receding tide uncovered the obstacles, which as we have seen inflicted heavy damage on landing craft.65

The clearance of exits from the beach was the business primarily of the AVREs and bulldozers of the assault engineers (the 5th Assault Regiment RE) and “Crabs” of the 22nd Dragoons. As already indicated, there was great difficulty in opening exits on the 7th Brigade front. A line of low sand-dunes, and beyond it a flooded area, were the causes of the trouble. On MIKE RED Beach, one exit was opened across the dunes just west of Courseulles and the flooded area behind them, a. bridge being laid and a rough causeway built across an AVRE which had become submerged at a cratered culvert on the track which it was planned to use. Some tanks got across about 9:15, then the causeway failed and traffic had to be stopped. This exit was not working quite satisfactorily until noon or later. A second one, on MIKE GREEN farther west, gave less trouble and was working

fairly well by about 9:30. In the meantime the assault infantry had made good progress inland, but very. few tanks or other vehicles were available to support them, and the beach was extremely congested.66

On NAN GREEN Beach, on the left, there was rather less difficulty; the Crabs dealt with the mines, an anti-tank ditch was filled with fascines dropped by the AVREs, armoured bulldozers improved the lanes, and both planned exits (leading into the East Courseulles strongpoint) were working by about 9:00 a.m. All across the brigade front the Engineers and the 22nd Dragoons had done yeoman service, and the former in particular had had a considerable number of casualties.67

The 8th Brigade Beaches

As has been explained above (page 78), the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group was to lead the assault on the eastern sector of the Canadian Division’s front, with The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada (Lt.-Col. J. G. Spragge) landing on NAN WHITE Beach, on the right, and capturing the resistance nest at Bernières, while The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment, under Lt.-Col. D. B. Buell, landed on NAN RED on the left and cleared the similar strongpoint at St. Aubin. The brigade’s reserve battalion was Le Régiment de la Chaudière (Lt.-Col. J. E. G. P. Mathieu). Armoured support in the assault phase would be provided by the DD tanks of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse), commanded by Lt.-Col. R. E. A. Morton, with B Squadron supporting the Queen’s Own and C Squadron the North Shore.

The DD tanks on the 8th Brigade front, as already indicated, had a quite different experience from those with the 7th; instead of swimming in, they left their craft close inshore and landed behind the infantry assault companies. The DD equipment was inflated, and the tanks used their propellers, but the operation was “really a wet wade”.68 Captain G. Otway-Ruthven, whose naval assault group landed the brigade, reported, “The LCTs. with the DD Tanks touched down at 0810 and except for one craft which beached on LOVE Sector and was missed all the tanks got ashore and the LCTs. got clear of the beach without much damage.”69 The war diary of the 10th Armoured Regiment implies, rather than states, that the tanks landed before the first infantry, but gives no time. All other evidence is that the infantry were earlier. The Queen’s Own Rifles indicate that the tanks were behind the assault companies. Evidence from the North Shore Regiment is that neither tanks nor Centaurs were present at the moment of the first infantry landing, which the officer commanding one of the assault companies puts at 8:05,70 but the battalion diary at 8:10. The 5th Assault Regiment records are similar. The 80th Assault Squadron indicates that on the right the infantry were first, followed by the AVREs and later by the tanks; on the left, it reports the DD tanks did not arrive until H plus 60.71 It seems evident that on both battalion fronts the DD tanks were behind the leading infantry, but likely that most of them landed only a few minutes later.

On the right sector of the Brigade front, B Company of the Queen’s Own ran into difficulty. Captain Otway-Ruthven reports that the assault companies “touched

down about 200 yards east of their correct position”. B landed directly in front of the “resistance nest” at Bernières. “Within the first few minutes there were 65 casualties.” Then Lieut. W. G. Herbert, Lance-Corporal René Tessier and Rifleman William Chicoski dashed at the pillbox which was causing the losses, and put it out of action with grenades and Sten gun fire. This opened the way for clearing the rest of the strongpoint.* In other respects the battalion’s experience paralleled that farther west. The other assault company, A, landing west of the strongpoint, had much less difficulty in getting off the beach, but shortly came under mortar fire and also suffered casualties. The reserve companies, like those on other sectors, suffered heavy casualties to their craft by mines as they came in, but fortunately losses among personnel were not numerous. By the time these companies arrived the Bernières strongpoint was being mopped up, and they were able to get through to the southern edge of the village. During the afternoon they led the battalion’s advance southward towards Anguerny, which was captured after some resistance had been overcome.72

This was the only Canadian assault battalion front where tank support was reported as ineffective. The 10th Armoured Regiment itself recorded that the QOR suffered severely “before B Squadron could support it”. The Special Observer Party, which did not report any visible damage by tank fire, got the impression that it was possible that “very good tactical surprise was achieved here”. But this was not in fact the case, and the troop of assault engineers working on the beach 500 yards east reported being heavily fired on by the two 50-mm. anti-tank guns in the Bernières strongpoint, which, they said, were silenced only after some 15 minutes, when they were captured by the infantry. Men of the 5th Field Company RCE, labouring at removing charges from the beach obstacles, also had heavy casualties on both NAN RED and NAN WHITE.73

On the left sector, the North Shore Regiment found that the St. Aubin strongpoint “appeared not to have been touched” by the preparatory bombardment. B Company had the task of dealing with it, and this was done with the assistance of the tanks and later the AVREs, which used their petards with effect. “The co-operation of infantry and tanks was excellent and the strongpoint was gradually reduced.” The battalion diary records that the area was cleared by 11:15, four hours and five minutes after landing. It appears, however, that there was still sniping going on after this time, and the OC B Company stated that the enemy in the strongpoint did not finally give in until 6:00 p.m.74

The 50-mm. anti-tank gun in the resistance nest here caused serious trouble in the early stages of the assault. B Company’s commander recorded that it knocked out the first DD tanks to arrive; subsequently two other tanks and an AVRE dealt with it. The Special Observer Party reported that the concrete of the emplacement bore the mark of a 95-mm. shell, evidently fired by a Centaur. The gun had been put out of action by tank fire, but “about 70 empty shell cases” around the emplacement attested the resolution with which its crew had fought it.

The North Shore’s A Company, landing to the west of B,75 suffered some casualties in booby-trapped houses but in general made good the beachhead objective without great difficulty. The reserve companies, C and D, likewise

* Herbert received the Military Cross, and Tessier and Chicoski the Military Medal.

had comparatively little trouble in the beginning. D carried out its task of securing the south end of St. Aubin, and C, which was to seize the inland village of Tailleville, met no opposition until it reached the actual outskirts of that hamlet. Here the enemy, well dug in, fought long and hard; in spite of early optimistic reports, it was “nearing evening” before the company, with tank support, finally cleared the place, taking over 60 prisoners.76 Divisional Headquarters logged the report of its capture at 8:10 p.m.

Le Régiment de la Chaudière, the brigade’s reserve unit, began to land at Bernières about 8:30 a.m. Its craft had a difficult time with the beach obstacles. Captain Otway-Ruthven described A Company’s experience: “The LCAs. of the 529th Flotilla

(HMCS Prince David) struck a very bad patch of obstacles and mortar fire on NAN WHITE and all foundered before touching down. The troops, however, discarded their equipment and swam for the shore. They still had their knives and were quite willing to fight with this weapon.” This was only a slight exaggeration; Canadian naval records indicate that just one of Prince David’s five assault craft made the beach undamaged.77 Luckily, most of the men reached it safely. The battalion, however, was held up along the sea-wall for some time while the Queen’s Own Rifles finished dealing with the strongpoint. It then advanced through the village, meeting opposition, and assembled in the wooded area on its south edge.78 The people of Bernières were surprised and delighted to find themselves liberated by men who spoke their own tongue. The regiment’s diarist wrote, “Les français sont assez accueillants et beaucoup nous acclament au milieu des ruins de leurs maisons.” Two years later the present writer, visiting Bernières, found the recollection of Le Régiment de la Chaudière still strong among the people of the village. The battalion records that it spent two hours in the assembly area (it reported itself still there at 1:56 p.m.) and then pushed southward towards Beny-sur-Mer, supported by A Squadron of the 10th Armoured Regiment. Traffic congestion slowed the advance. A Company captured a battery, described, apparently inaccurately, as consisting of 88-mm guns, and, evidently somewhat later, B took what may have been the position known as the Beny-sur-Mer battery (above, page 68).79 Beny-sur-Mer itself was captured by C Company, apparently about mid-afternoon, though the actual time seems nowhere to have been recorded.*80

The two self-propelled artillery regiments employed on the 8th Brigade front, the 14th Field Regiment and the 19th Army Field Regiment, RCA, began to land at 9:25 and 9:10 a.m. respectively. They had no great difficulty in getting off the beach. The 14th had 18 guns in action near Bernières by 11:30; the 19th had its first gun in action at 9:20. Both regiments had casualties in men and guns from enemy artillery fire. It appears that both spent most of the day in action in improvised gun areas close to Bernières. In the evening the 14th, at least, moved forward to a planned area a mile or so north of Beny.81

* Headquarters 8th Brigade signalled the Chaudière at 3:35 p.m., “Understand you are in ALEPPO [Beny]”, but there is no confirming reply in the log.

On the 8th Brigade beaches, as on the 7th’s, the Royal Marine Centaurs had not a very great deal to do. One troop came into action on the beach against targets in St. Aubin and subsequently gave assistance to No. 48 Commando in its struggle to clear the village of Langrune-sur-Mer just to the eastward. A number of Centaurs intended for these beaches did not arrive until D plus 1 or D plus 2.82

On clearance of obstacles, the story on the 8th Brigade beach was much the same as on the 7th’s. By the time the engineers arrived the tide was too high to permit much work on them; “it was obvious from the outset”, recorded No. 80 Assault Squadron RE, “that beach obstacles could not be cleared”. Neither the sappers nor the naval Landing Craft Obstacle Clearing Units were able to make headway with the task until the tide fell.

Four beach exits were planned for the brigade front: two at the village at Bernières and two between Bernières and St. Aubin.83 The set of the tide caused most of the engineers’ craft to touch down some distance east of their planned positions. In the Bernières area the high sea-wall caused some trouble, which was made worse by the effects of enemy fire. However, four exits were opened here by the 5th Assault Regiment RE, one with the aid of a “small box girder” assault bridge placed over the wall by an AVRE, one at a point where the wall had been broken down, one by clearing an obstructed ramp, and one in a manner not described. On the beach east of Bernières there was less trouble; with the assistance of Crabs which flailed lanes through the sand dunes at least two exits were shortly opened, one using a bridge over the wall, the other being a double lane passing over the dunes. In general the situation was less difficult than at Courseulles, and in consequence there was somewhat less congestion on the beaches.84

The Reserve Brigade Lands

While the 7th and 8th Brigades were fighting their way forward, the craft carrying the reserve brigade, the 9th,* were circling offshore waiting their turn to go in. At 10:50 a.m. Divisional Headquarters ordered the brigade to land.85 As was natural in the state of the beaches, it was sent in through the 8th Brigade sector in accordance with the primary plan (above, page 79). However, it was considered necessary to land the entire brigade on Nan White beach.86 (Craft had been diverted from NAN RED since about 10:30, since “the craft casualties were getting serious”;87 the opposition still being offered by the St. Aubin strongpoint may also have had some influence.) This meant that the whole brigade had to land through Bernières and make its way southward over one road only, that leading to Beny-sur-Mer.

The battalions actually began to land about 11:40. At 12:05 Brigade Headquarters reported, “Beaches crowded, standing off waiting to land”; but fifteen minutes later it signalled that the brigade commander had landed and the units were moving to their assembly area near Beny.88 However, the 8th Brigade’s

* This brigade crossed the Channel in the same craft—Landing Craft Infantry (Large)—which landed it on the beaches.

slow progress and the severe congestion around Bernières retarded the movement. The battalions halted on the outskirts of the village, and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders (Lt.-Col. C. Petch), who were in the lead, did not move on towards Beny until 4:05 p.m. They were accompanied by the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment), commanded by Lt.-Col. M. B. K. Gordon, and were followed by the other battalions of the brigade, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (Lt.-Col. G.

H. Christiansen) and The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (Lt.-Col. F. M. Griffiths).89 At 6:20 p.m. the North Nova Scotias and the 27th Armoured Regiment, acting as the brigade’s advanced guard, moved off from the assembly area to pass through the Queen’s Own and the Chaudière and carry the advance southward. Three. companies of the Highlanders rode on the Sherbrookes’ tanks. In the vicinity of Colomby-sur-Thaon A Company met opposition which, while not serious, caused some further delay. The vanguard in the meantime had run into other resistance at Villons-les-Buissons. It was now evident that the advanced guard units could not reach their objective in the Carpiquet area before dark. They were therefore ordered to dig in for the night in the area where they found themselves “and to, form a firm base while there was still light”.90 The infantry and tanks accordingly “formed a fortress” in the area Anisy—Villons-les Buissons.91 The brigade’s other battalions were still in the assembly area at Beny.

General Keller had left HMS Hilary with part of his staff at 11:45, and Divisional Headquarters was set up in a small orchard at Bernières. Here at 2:35 p.m. Keller held a conference which was attended by the commanders of the 8th and 9th Infantry Brigades and the 2nd Armoured Brigade. No changes of plan resulted. It was confirmed that the North Shore Regiment was having trouble in Tailleville and that the 8th Brigade would push on to take Beny-sur-Mer, while the 9th would pass through it on the GOC giving the code word “Kingston”.92 These orders, we have already seen, were duly carried out.

At 9:15 p.m. the GOC sent out his orders for the night by liaison officer. The 7th Brigade on the right was to occupy the area Le Fresne-Camilly—Cainet. The 8th was to hold the area Colomby-sur-Thaon—Anguerny and to contain La Délivrande and Douvres-la-Délivrande with a view to clearing them both at first light in the morning. The 9th Brigade was to occupy the area Villons-les-Buissons—Le Vey.* This was generally equivalent to ordering the brigades to hold the ground on which they found themselves, namely, the intermediate objective known in the plan as ELM (above, page 77). The 10th Armoured Regiment, and the 6th less one squadron, were to revert to the command of the 2nd Armoured Brigade and harbour in the area Beny-sur-Mer—Basly. (In fact, the whole of the 6th Armoured Regiment harboured at Pierrepont in the 7th Brigade area.) Division ordered active patrolling and “utmost preparation” to meet a counter-attack at first light.93

The Division had made much less progress than the day’s plans had called for. (As we shall see, its neighbours were in similar case.) The time-table had

* There is no record of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders having occupied Le Vey during the night, but they may well have covered the area by patrols without recording the fact.

been in arrears from the beginning, when the state of the sea necessitated setting back the times of landing; and it had fallen steadily further behind as the hours passed. The lateness of the landing, and the consequent impossibility of clearing the beach obstacles, resulted in the beaches becoming clogged with damaged craft. And as so often in this war, the vehicles of a mechanized army, intended to facilitate rapid movement, had in fact become hindrances to advance. The difficulty in opening exits from the beaches had led to congestion, and the enemy’s determined resistance at certain points, notably St. Aubin and Tailleville, had paid him considerable dividends. The accumulated difficulties, by forcing the reserve brigade to land on a narrow front where it had only one forward route available, prepared the way for further delays.

To the Division’s failure to reach even its final D Day objectives there was one small exception, or rather near-exception. A troop of tanks of C Squadron of the 1st Hussars, commanded by Lieut. W. F. McCormick, which was supporting The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, helped them through Creully and then “just kept on going”, pushing on through Camilly to the north edge of Secqueville-en-Bessin. En route they shot up a German scout car and inflicted casualties on parties of infantry; and Mr. McCormick was punctiliously saluted by a German soldier who evidently did not expect to meet the enemy so far inland.94 The fact that these few tanks—which probably got closer to the final inland objective than any other element of the Allies’ seaborne assault forces that day—were able to push so far and return is evidence of how slight the resistance on the 7th Brigade’s ‘front was during the afternoon.

The armoured cars of the Inns of Court Regiment had not been able to carry out their task (above, page 81) of destroying bridges over the Orne. Some of the squadron’s vehicles were lost before landing or on the beaches. It landed at Courseulles, and was one of the victims of the slowness in opening beach exits there. An isolated message from it appears in the Division’s log at 11:40 a.m.: “Left exit clear, priority to be given to antitank guns”. It seems to have got off the beach about noon, and the greater part of it crossed the Seulles at 3:00 p.m., apparently at Creully. But the armoured cars did not get through to the Orne, or the nearer Odon, which the 1st Corps operation instruction had prescribed as an alternative objective.95

The casualties suffered by the 3rd Canadian Division on D Day, though heavy, were fewer than had been feared. For the whole day Canadian losses in the seaborne force amounted to 340 all ranks killed or died of wounds, 574 wounded and “battle injuries”, and 47 taken prisoner. It is not possible to distinguish between casualties suffered on the beaches and those in the later stages. There was not much difference between the casualties of the two assault brigades.* The Infantry unit that suffered most heavily was the Queen’s Own Rifles of the 8th Brigade, which lost 143 men; this loss was presumably mainly caused by the strongpoint at Bernières, captured without tank assistance. Next came The Royal

* In The Canadian Army 1939–1945 the writer made the statement that the beach battle was “somewhat fiercer” on the 7th Brigade’s front than on the 8th’s. More careful and leisured analysis leads him to the conclusion that there was little to choose between the two.

Winnipeg Rifles, which had 128 casualties. This reflects the bitter fight at Courseulles. The North Shore Regiment lost 125 men, chiefly undoubtedly in the prolonged fighting at St. Aubin and Tailleville.96 A detailed tabulation of Canadian D Day casualties will be found at Appendix B.

The Situation at the End of D Day

At this point, let us lift our eyes from the situation on the Canadian sector and survey the general progress of the great Allied assault. Speaking broadly, the day had been extraordinarily successful; but, as was only to be expected, the degree of success varied considerably between different areas.

On the far right the two United States airborne divisions were greatly scattered during their drop.* The operations of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were far from going according to plan. Nevertheless, although casualties were heavy and there was some confusion, these operations were valuable. By the evening of D Day the airborne troops had captured Ste Mère-Eglise and were in general control of a large area lying between that place and Carentan. They had certainly contributed materially to disordering the enemy and confounding his counter-measures.

Of all the seaborne assaults, that which met least resistance was the attack by the 7th US Corps, with the 4th US Infantry Division under its command, on UTAH Beach in the lower part of the Cotentin peninsula. We have seen that the bombing of the beach defences was more effective here than elsewhere. Although the assault battalions were landed almost 2000 yards south of the planned positions, this was actually fortunate, since they struck areas which were less heavily defended. Success was complete and casualties “extraordinarily light”. By evening a substantial bridgehead had been established.97

Very different was the story on OMAHA Beach, east of the estuary of the Vire. Here the invading forces had more difficulty than at any other point; losses were extremely heavy, and for a time success seemed to hang in the balance. On this front the 5th United States Corps was assaulting with the 1st US Infantry Division, reinforced by part of the 29th, under its command. At least some of the reasons for the trouble here are fairly obvious. For one thing, the military quality of the defenders (the 352nd German Division) was somewhat higher than elsewhere. As we have seen, this division had moved up to the beaches in March. (Information indicating this move had reached the Allies before the assault, though the 21st Army Group’s weekly intelligence review issued on June 4 described the evidence for it as “slender indeed”.) The terrain, moreover, favoured the defenders. The coast was steeper than on the British front farther east, the beaches being overlooked at short range by high ground. At the same time, the German defences on this sector were probably somewhat stronger than at any other point on the front, particularly in terms of the number of machine-guns bearing on the beaches. In addition, the assaulting infantry were less strongly

* Their drop patterns are graphically shown by maps IX and X in Harrison, Cross-Channel Attack.

supported than on the British sectors. A battalion of DD tanks was employed here, but of 32 of them launched on the eastern half of the sector only five reached the shore; while artillery being ferried ashore in DUKWs had even higher casualties from the heavy sea.98 The Americans had no engineer assault vehicles or flails. Those who have read the account of events on the Canadian beaches will realize that without the DD tanks, AVREs and Crabs Canadian casualties would certainly have been higher than they were.*

The result of all these circumstances was that the Americans on OMAHA had to fight desperately to gain and keep a foothold, and casualties here were heavier than anywhere else. On the evening of D Day the beachhead was still narrow and precarious, 2000 yards deep at best. Not until 8 June did the advance on this sector really get under way.99

On the front of the 30th British Corps (GOLD sector), which was assaulting with the 50th British Infantry Division under command, the situation developed in a manner not unlike that on the Canadian front. The landing was carried out successfully, although, as already indicated, certain strongpoints on the coast offered prolonged resistance, and the final inland objectives were not reached. By the evening of D Day the 50th Division was firmly established ashore, had penetrated to within striking distance of Bayeux and the Bayeux-Caen road, and was in touch with the 3rd Canadian Division on its left (the 7th Green Howards and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles having made contact with each other at Creully during the afternoon).100 The 50th Division beachhead and the Canadians’ were thus firmly linked up, but the 50th was not yet in touch with the Americans on OMAHA.101

There had likewise been no contact as yet between the 3rd Canadian Division and the 3rd British Division on its left. When night fell on D Day the Germans were still resisting in a portion of the beach defences immediately east of the Canadian sector. As already explained, the task of clearing, these had been allotted to Royal Marine Commandos of the 4th Special Service’ Brigade. ‘They ran into serious trouble. No. 48 Commando, landing at 8:43 a.m.- on D Day opposite and immediately east of the St. Aubin strongpoint, suffered very heavily from the strongpoint’s fire and subsequently met resolute opposition in Langrune. A similar situation faced No. 41 Commando, which landed at Lion-sur-Mer with the mission of clearing that village and Petit Enfer to the west of it. The Lion strongpoints proved very difficult to deal with and on the afternoon of D Day the 8th British Infantry Brigade took over the direction of the fight there.† The last strongpoint in Lion was taken only on 8 June. It was necessary on the morning of the 7th to land No. 46 Commando to deal with Petit Enfer. The strongpoint here surrendered at 6:00 p.m. that day.102

The 3rd British Division itself had met serious resistance north of Caen and had failed to seize the city. By the evening of D Day, however, it held a solid wedge of territory with its base on the coast between Lion and Ouistreham,

* For a discussion of the Americans’ refusal to avail themselves of the British “special armour”, except the DDs, see Chester Wilmot, The Struggle for Europe, 264-6, 291.

† The diary of No. 41 Commando indicates that it came under the command of the 9th Brigade (evidently an error for the 8th) at 3:00 p.m.

Map 2: Canadian Assaults. D Day