Chapter 7: Normandy: The Battles of Caen and Bourguébus Ridge, 1–23 July 1944

(See Map 3 and Sketches 10 and 11)

A Momentary Pause

At the beginning of July 1944 there was a momentary pause in the operations in Normandy. On the British front the Battle of the Odon was dying down. On the American front to the west General Bradley’s Army was preparing for the drive southward prescribed in General Montgomery’s directive of 30 June. The Germans still held Caen, but they had been forced to abandon hope of mounting a major counteroffensive to destroy our bridgehead. Their operations were hamstrung by the apprehension of another Allied landing on the Strait of Dover; and Hitler was in the act of replacing his senior commander in the West and one of his chief subordinates.

As we have seen, Tactical Headquarters First Canadian Army was in France, but for the moment had no work to do; though General Crerar himself used the opportunity to make ground and air reconnaissances of his prospective theatre of operations. His Main and Rear Headquarters had also opened, theoretically, at Amblie in Normandy at midnight on 19-20 June; but their actual moves from England were postponed by the gale then in progress and by General Montgomery’s subsequent decision not to make the Army operational at present (above, pages 146-7). Accordingly, they re-opened at their old station at Headley Court, near Leatherhead, Surrey, at midnight on 25-26 June. The Army’s pre-D Day planning for this phase, based on the orderly principle of bringing in the Army Headquarters and administrative units first, so that they could supervise the subsequent arrival of the fighting formations, had turned out to be merely a waste of time. Fighting formations, to “stake out” more ground, were what were urgently needed under the now existing conditions.1

In accordance with Montgomery’s original policy, however, Headquarters 2nd Canadian Corps was beginning to move to France. The Corps Commander, Lieut.-General Simonds, opened his Tactical Headquarters at Amblie on 29 June and his Main Headquarters at Camilly a week later. The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was also on the move to France; its leading units disembarked on 7 July.2 For the moment Simonds’ corps had no operational responsibilities.

With the operations immediately in prospect, then, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade associated with it, were still the only Canadian formations directly concerned. The Division continued to hold the line which it had taken up and made good north-west of Caen, from La Villeneuve on the Bayeux road on the right to Villons-les-Buissons on the left, confronting Carpiquet, Authie and Buron. It was still under the 1st British Corps, which was about to carry out General Montgomery’s direction to the Second Army to “develop operations for the capture of Caen as opportunity offers-and the sooner the better”. The method now proposed was a frontal attack with the heaviest possible support.

The Capture of Carpiquet

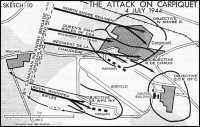

As a preliminary to attacking Caen itself, the 1st British Corps ordered the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division to capture Carpiquet village and the adjoining airfield. As we have seen (above, page 150) a plan had been prepared for this purpose but the operation (WINDSOR) had been postponed on 30 June. It was now revived “in more virile form”3 and the attack was delivered on the morning of 4 July. The task was difficult, for the objective was held by units of the 12th SS Panzer Division, now commanded by Kurt Meyer (who had succeeded General Witt when the latter was killed on 14 June),4 and the defenders were well dug in. Accordingly, the plan provided for powerful support.

The attack was to be made by the 8th Infantry Brigade (Brigadier K. G. Blackader), with The Royal Winnipeg Rifles attached from the 7th Brigade. The 10th Armoured Regiment was to provide tank support, along with “special armour” from the 79th Armoured Division—a squadron each of Flails, Crocodiles and AVREs. Fire support was to be provided by bombarding ships of the Royal Navy and by 12 field, eight medium and one heavy regiments of artillery and three companies of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG) with their medium machine-guns and mortars. There was a programme of air attacks on pre-arranged targets and in addition Blackader had two squadrons of Typhoon fighter-bombers on call. WINDSOR was to be carried out in two phases. The first was the capture of Carpiquet village and the adjacent hangars on the north side of the airfield, as well as the opposite group of hangars on the south edge of the field. The second phase was to see the capture of the control buildings and other structures at the east end of the field. In the first phase, the North Shore Regiment (left) and Le Régiment de la Chaudière (right), each supported by a squadron of tanks from the 10th Armoured Regiment and a half-platoon of the 16th Field Company RCE, were to attack Carpiquet village from a start-line in front of La Villeneuve. Simultaneously The Royal Winnipeg Rifles would advance from Marcelet against the southern hangars. During this stage The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada were to be in reserve; subsequently they would pass through the village and carry out the second phase. The infantry were to cross the start-line at 5:00 a.m., following a creeping barrage fired by six field and two medium regiments.5

On 3 July the troops moved into the assembly areas in rear of the start-line

Sketch 10: The Attack on Carpiquet, 4 July 1944

(previously held by units of the 43rd Division). The enemy obviously observed the movement, and during that day and the night that followed the villages were heavily shelled and mortared.6 When our barrage opened at 5:00 a.m. on the 4th the Germans immediately replied with a counter-barrage. It caught the leading companies as they moved across the start-line, and in their advance through the level fields of ripening wheat separating them from the objectives they suffered heavily. As men fell, their comrades marked their positions for the stretcher-bearers by bayoneted rifles stuck upright among the grain, and then pushed on. By 6:32 the leading troops of the North Shore were on their objective. Le Régiment de la Chaudière on their right also reached the village. The two battalions then proceeded to clear it. The garrison, reported in a post-war narrative by the 12th SS Panzer Division’s senior staff officer to have consisted of only 50 men of the 25th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, fought fiercely.7 The Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ attack on the hangars ran into trouble from the beginning, the leading companies being heavily mortared from the moment they crossed the start-line and subsequently meeting heavy machine-gun fire from the hangars themselves. The tank squadron allotted to the Winnipegs had been held in reserve in the first instance, and was assisting merely by fire. After a request from the Rifles’ commanding officer one troop of tanks now moved forward in direct support. Not until 9:00 a.m., however, did two of the Winnipeg companies reach the nearest hangar; and then they found the enemy so strongly posted that neither tanks nor Crocodiles could drive him from his pillboxes. The area, moreover, was swept by fire from the high ground just south of the control buildings. Unable to gain a foothold in the hangars, the Winnipegs withdrew to the sparse shelter of a

copse close to the start-line. About 4:00 p.m. the battalion again advanced but again met extremely stiff resistance. Enemy tanks approaching the airfield from the east were several times dispersed by artillery but rallied on each occasion; and this threat forced the forward companies, which had “again reached the first hangars”, to retire. At 9:00 p.m. Brigade ordered the battalion back to the start-line and 44 rocket-firing aircraft were sent in to attack 17 enemy tanks or self-propelled guns which had been reported dug in around the airfield. The second phase was not carried out.8

During the early stages of the operation part of the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers) had carried out a diversionary attack on the left towards the Château de St. Lôuet and Gruchy. This was successfully executed and a considerable number of casualties were inflicted on the enemy without our own force suffering any important losses.9

The day’s work had thus been only a partial victory, in spite of the great weight of support employed. We now held Carpiquet village and the northern hangars; but the south hangars and the control buildings remained in enemy hands. Troops of the 43rd (Wessex) Division who had occupied Verson and Fontaine-Etoupefour on the right were withdrawn during the night as a result of the failure to complete the capture of the airfield.10 The 8th Brigade’s units on the high ground at Carpiquet were in an exposed salient. Early on the morning of 5 July a series of enemy counter-attacks supported by artillery and Panthers were beaten off.11 For the next few days Carpiquet was subjected to intermittent heavy shell and mortar fire. The 12th SS, alarmed by the threat to Caen represented by our possession of Carpiquet, nevertheless lacked the infantry for further counter-attacks. But a regiment of the 7th Mortar Brigade (Werferbrigade), which had been placed under its command, set up numerous projectors which bombarded the village with 110-lb. high explosive and oil bombs and made it a very nasty place.12

The partial success of Operation WINDSOR had been dearly bought. On 4 July The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment had its heaviest casualties of the whole campaign, amounting to 132, of which 46 were fatal. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles also had 132 casualties, 40 being fatal. The other armoured and infantry units involved at Carpiquet suffered as follows:13

| Total Casualties | Fatal Casualties | |

| 10th Armoured Regiment | 20 | 8 |

| Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada | 26 | 4 |

| Régiment de la Chaudière | 57 | 16 |

The 16th Field Company had 10 casualties, three men losing their lives.

Theatre Strategy and the Use of Heavy Bombers

It is likely that the ten days following the conference on 15 June which is said to have been interrupted by Air Chief Marshal Tedder (above, page 144) witnessed discussions at high levels concerning the possibility of using the strategic air forces

in direct support of the armies; but no record of them seems to have come to light. It is possible that the Supreme Commander, who as we have seen had insisted upon having control of the strategic air (above, page 23), intervened to settle the argument in favour of the use of the heavy bombers. At any rate, on 25 June General Eisenhower telegraphed General Montgomery14 wishing him luck in the Odon offensive and adding,

Please do not hesitate to make the maximum demands for any air assistance that can possibly be useful to you. Whenever there is any legitimate opportunity we must blast the enemy with everything we have. ...

This has the appearance of an invitation to ask for the heavy bombers. And in fact the RAF Bomber Command intervened in Normandy in daylight for the first time five days later, when it dropped 1100 tons of bombs on Villers-Bocage to interfere with the assembly of German armour for the Odon battle.15

Some of the officers about Eisenhower were still critical of Montgomery’s failure to get forward on the eastern flank, and it would seem that they were urging him to bring pressure on the Army Group Commander. But it must have been clear to Eisenhower that he could scarcely urge Montgomery forward while at the same time refusing him the heavy bombers. About this time, on a date which is not given, the Supreme Commander instructed Tedder “to keep the closest touch with General Montgomery or his representatives in 21st Army Group, not merely to see that their requests are satisfied but to see that they have asked for every kind of support that is practicable and in maximum volume that can be delivered”.16 On 7 July Eisenhower wrote Montgomery a long letter17 which, while tactfully phrased, was clearly intended to encourage him to push on. Referring to his own recent studies of the situation, “particularly in consultation with G-2 [Intelligence] and the Air Commanders”, he proceeded to urge Montgomery to strike hard on his left:

I am familiar with your plan for generally holding firmly with your left, attracting thereto all of the enemy armour, while your right pushes down the Peninsula and threatens the rear and flank of the forces facing the Second British Army. However, the advance on the right has been slow and laborious. ...

It appears to me that we must use all possible energy in a determined effort to prevent a stalemate or facing the necessity of fighting a major defensive battle with the slight depth we now have in the bridgehead.

We have not yet attempted a major full dress attack on the left flank supported by everything we could bring to bear. To do so would require some good weather, so that our air could give maximum assistance. Through Coningham and Broadhurst there is available all the air that that could be used, even if it were determined to be necessary to resort to area bombing in order to soften up the defense. ...

... please be assured that I will produce everything that is humanly possible to assist you in any plan that promises to get us the elbow room we need. The air and everything else will be available ...

To this “friendly nudge” General Montgomery on 8 July made a firm and rather cool reply.18 He wrote, “I am, myself, quite happy about the situation. I have been working throughout on a very definite plan, and I now begin to see daylight.” He mentioned the attack on Caen which was then in progress and again referred to the importance of operations there assisting “our affairs on the western

flank”. His letter concluded, “Of one thing you can be quite sure-there will be no stalemate. ... I shall always ensure that I am well balanced; at present I have no fears of any offensive moves the enemy might make; I am concentrating on making the battle swing our way.”

Although Eisenhower’s reference to ample air support being available “through Coningham and Broadhurst” might have suggested a continued unwillingness to use the strategic bombers, this was not the case. At the time he wrote, the RAF Bomber Command was already committed to direct support of the Second British Army at Caen. On the evening of 7 July it struck a great blow to clear the way for the capture of the city.

The Action of the Orne: The Capture of Caen

Planning for the attack on Caen was well advanced before Operation WINDSOR went in. General Crocker, commanding the 1st British Corps, held his first conference about the operation on 2 July, and the Corps order for the operation (CHARNWOOD) was issued on 5 July.19 It defined the intention as to clear Caen as far south as a line from the point where the Caen-Bayeux railway crossed the Orne along that river to its intersection with the Canal de Caen and thence along the Canal de Caen itself. Bridgeheads were to be secured across the Orne in the city area. The order, somewhat peculiarly phrased in this respect, defined the “Final Objective” as a general line running through the villages of Franqueville and Ardenne and onward north of Caen to a point about a mile north of the centre of the city. The more distant objectives defined in the intention were described as “objectives for exploitation”. Three infantry divisions were to take part, advancing on Caen in a semi-circle: the 3rd Canadian Division on the right, the newly-arrived 59th (Staffordshire) Division in the centre and the 3rd British Division on the left. A great number of guns, including those of the 3rd and 4th Army Groups Royal Artillery, would support the attack. Heavy naval bombardment was also planned; the battleship Rodney, the monitor Roberts and the cruisers Belfast and Emerald took part.20

Moreover, as already mentioned, the heavy bombers now appeared above the battle. The arrangements for air support were apparently completed only on 7 July,21 and no information has been found concerning the precise manner in which they were arrived at. Field-Marshal Montgomery has written, “The plan involved an assault against well organized and mutually supporting positions based on a number of small villages which lay in an arc north and north-west of the city, and, in view of the strength of these defences, I decided to seek the assistance of Bomber Command RAF in a close support role on the battlefield. ... The Supreme Commander supported my request for the assistance of Bomber Command, and the task was readily accepted by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris.”22

This part of the operation has proved to be controversial, both as to timing and targets. It was considered that the “bombline” for the heavy bombers should be at least 6000 yards from our leading troops. This probably largely dictated the decision as to the target to be assigned to Bomber Command, which was defined

as four map squares on the northern outskirts of Caen, amounting in fact to a rectangle some 4000 yards long by 1500 wide.23 This area did not include the fortified villages in the front line which our troops had to capture in the early stages of the operation; these were to be dealt with by the artillery. It appears that there were not actually a great many enemy defences in the area attacked by the heavy bombers; but in Lord Montgomery’s words, “In addition to the material damage, much was hoped for from the effects of the percussion on the enemy defenders generally, and from the tremendous moral effect on our own troops.” It would obviously have been desirable that the Bomber Command attack should take place immediately before the troops on the ground advanced; however, Lord Montgomery states that “owing to the weather forecast” it was necessary to carry out the bombing the previous evening.24 This point has been disputed. The forecast issued in Normandy on the morning of the 7th was not unfavourable, and in fact large forces of Bomber Command operated over France during the following night.25 Be this as it may, the heavy bombers attacked between 9:50 and 10:30 p.m. on 7 July, while the ground operation began only at 4:20 the following morning.

In the fading light of evening the air attack came in. Like all such operations, it was tremendously impressive. Bomber Command “employed 467 bombers to drop 2,562 tons of bombs”.* In reply to an urgent inquiry from the 1st British Corps as to the results, the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade replied, “Smoke and flame wonderful for morale”, and a little later, “Everything to our front seems to be in flame. Cannot get anything more accurate.” No bombs had fallen short.26

There was no doubt at all of the bombing’s results among our own troops. A message from The Highland Light Infantry of Canada said, “The stuff going over now has really had an effect on the lads on the ground. It has improved their morale 500 per cent.”27 The effect on the enemy is more doubtful. The available contemporary German records (which do not include the diaries of the divisions and corps concerned) throw little direct light on the matter. The senior staff officer of the 12th SS Panzer Division states that his formation “suffered only negligible casualties despite the fact that numerous bombs fell in the assembly areas of the 2nd Panzer Battalion and the 3rd Battalion 26th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. Some tanks and armoured personnel carriers were toppled over or buried under debris from houses, but after a short while nearly all of them were again ready for action.”28 A 21st Army Group intelligence summary of 11 July, undoubtedly based upon the interrogation of prisoners, asserts, “The heavy bombing of Caen was decisive. 31 GAF [German Air Force] Regiment lost its headquarters and 16 GAF and 12 SS Panzer Divisions were deprived of rations and ammunition for the crucial morning which followed.” The moral effect upon the German troops, and particularly upon the Luftwaffe division, was probably very considerable. But the matter had a tragic aspect-the lamentable damage done to the city of Caen, and the inevitable casualties among French civilians. The havoc was great, the city’s university being among the buildings lost. Fortunately, the

* These are the figures given in Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory’s despatch, which however is in error in stating that the attack took place at 4:30 a.m. on 8 July.

Sketch 11: The Capture of Caen, 8–9 July 1944

inhabitants had been partly evacuated from the areas most heavily struck. The number of French casualties was apparently between 300 and 400.29

Almost immediately after the end of the bombing attack the British artillery opened fire. The guns of the 8th Corps, on the right, were employed in long-range harassing fire against the roads leading into Caen from the south and south-west. An hour before midnight the artillery supporting the 1st Corps—656 guns were available—began firing on the villages behind the German front line. La Folie, St. Contest, St. Germain-la-Blanche—Herbe, Lebisey and Authie were pounded in turn through the night. Every known hostile battery was also fired on. Then, at 4:20 a.m. on 8 July, 93 minutes before sunrise, the planned barrage and concentrations came down across the fronts of the 59th and 3rd British Divisions as their infantry moved across the start-line into the assault.30 Thus began a day of fierce and bloody fighting.

In the first phase the British divisions were to capture Galmanche, La Bijude and Lebisey Wood. The 3rd Canadian Division was not involved at this stage, but in Phase II, which was to be launched when ordered by Corps Headquarters after one hour’s notice, the Canadians were to capture the Château de St. Lôuet, Authie, and a patch of high ground immediately south of Buron. In Phase III they were to push on to the general line Franqueville–Ardenne. During these two phases the two British divisions were to continue the advance on their fronts. Phase IV was to witness exploitation by all three divisions designed to secure and mop up Caen to the Orne and the Canal de Caen. Only now was the Canadian division to attack those parts of the Carpiquet airfield still in enemy hands. The fifth phase, for the Canadians, would consist of the completion of Phase IV; while the British divisions were to secure the required bridgeheads across the Orne, launching these thrusts at their own discretion as opportunity arose.31

The first reports from the British fronts indicated good progress, but in fact both divisions (and more especially the 59th) were meeting heavy opposition and continued to meet it until evening. However, the early reports were sufficiently encouraging to lead General Crocker at 6:30 a.m. to order Phase II to begin at 7:30.32 At that time, accordingly, the 59th Division moved against St. Contest, Malon and Epron; and the 3rd Canadian Division launched its attack towards Gruchy and Buron. The task here fell to the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, which had met a stiff check in this same area on 7 June.

“Unbelievable”33 artillery concentrations on the enemy positions in the villages and in front of them prepared the way for the brigade’s advance. On the right, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders had the mission of taking Gruchy. The place was reported in Canadian hands at 9:38.34 Taking it had not been easy, but it was easier than the task in the adjoining sector on the left.

The forward companies of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, advancing towards Buron, came under heavy artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire. They cleared the enemy’s positions in front of the village, losing heavily in the process, and then fought their way across the built-up area, assisted by tanks of the 27th Armoured Regiment whose arrival had been delayed by mines. Although it was reported at 8:30 a.m. that the HLI’s forward troops were in Buron, some

of the enemy fought on all day among the rubble, and in fact the last survivors were not rooted out until the following morning. In this area the 3rd Battalion, of the 25th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment was fighting with the bitterness expected of the 12th SS Panzer Division; and the Canadians got the impression that the garrison of Gruchy when evicted had retired into Buron to strengthen the defence there. The Highland Light Infantry were fighting their first real battle at Buron, and it proved to be, like the North Shore’s at Carpiquet, their bloodiest of the campaign. The battalion’s casualties on 8 July amounted to 262, of which 62 were fatal; its commander, Lt.-Col. F. M. Griffiths, was among the wounded, but the day also brought him the DSO Not only was Buron taken, but a very formidable armoured counter-attack late in the morning was beaten off with the efficient assistance of two troops of the 245th Anti-Tank Battery Royal Artillery and the supporting squadron of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment. Fourteen German tanks were reported destroyed.35

At 9:55 a.m. General Keller ordered Brigadier Cunningham, commanding the 9th Brigade, to carry the operation on to the next stage, attacking south to envelop Authie and the Château de St. Lôuet.36 This advance was slow in getting under way, probably because of the fierce resistance still being offered about Buron, and the GOC, who seems to have underestimated this resistance, was displeased; but during the early afternoon the Glengarrians captured the Château and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders avenged their grim experience of D plus 1 by taking Authie. Our troops at Carpiquet could now see enemy parties withdrawing southwards in disorder; the enemy, fiercely though he had fought, was showing signs of cracking.37 The way was clear for the 7th Infantry Brigade to initiate its part of Phase III, passing through the 9th to assail Cussy and Ardenne. This attack began at 6:30 p.m. The Canadian Scottish had trouble at Cussy, which was covered by heavy fire from the Germans in Ardenne on one flank and Bitot (in the 59th Division’s area) on the other; and when the enemy’s infantry was driven out his tanks launched a determined counter-attack. But they failed to regain the village, and the Scottish claim to have knocked out six of them. In Cussy the battalion buried more than one German officer who had fought among his troops “to the bitter end”.38

The Regina Rifle Regiment, attacking the Abbey of Ardenne, which was still the command post of the 25th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, met perhaps even heavier opposition. When Kurt Meyer found that this position was threatened he hastened there himself to direct the defence. Under his leadership a company of Panther tanks and the remains of the 3rd Battalion of the 1st SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment (from the Adolf Hitler Division), which had been attached to Meyer’s division, managed to bring our attack to a temporary standstill. At nightfall the ruined Abbey buildings, surrounded by luridly burning German and Canadian tanks, remained in the enemy’s hands. He withdrew, however, during the night.39

While the 12th SS Panzer Division fought so desperately in the centre and on the west flank, the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, a raw formation which had relieved the 21st Panzer Division north-east of Caen only three days before,40

was being badly mauled by the experienced 3rd British Division. By evening the latter had advanced through Lebisey and was threatening to cut off the SS units still resisting the 59th Division in the villages in the German centre.41

There was some hope that a spearhead might reach the Orne bridges at Caen before they could be destroyed, and in the evening General Keller directed a force of armoured cars from the Inns of Court Regiment, with part of the 7th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment* under command, to push forward along the highway through St. Germain-laBlanche-Herbe. It got into that suburb before enemy mines and snipers checked its progress in the gathering darkness. It seems evident that no Allied troops got close to the bridges until the following day.42

During the evening Field-Marshal Rommel arrived at the headquarters of Panzer Group West to consult with its commander, General Eberbach; and with his approval the Panzer Group ordered all heavy weapons withdrawn from Caen that night. “Strong infantry forces, supported by engineers” were to continue to resist in the, line north and west of Caen, and “only in the event of an enemy attack with superior forces” were they to withdraw to the line defined as “east bank of the Orne-northern outskirts of Venoix-northern edge of Bretteville [sur-Odon]”. This was not much more than a face-saving formula. About 3:00 a.m. on 9 July, it appears, the final evacuation of Caen as far as the Orne was ordered. The 3rd Battalion of the 26th Panzer Grenadier Regiment was to act as rearguard in the 12th SS Panzer Division’s sector.43

In these circumstances, 9 July witnessed the British occupation of Caen. In the morning the 59th Division moved into the villages to the north, while the two flanking divisions, the 3rd British on the east and the 3rd Canadian on the west, “pinching out” the 59th, filtered into the city on their own fronts and joined hands. There was still opposition, but it was not heavy. The squadron of the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment working under command of the Inns of Court pushed towards the Orne bridges in the centre of the city and reached them in the course of the afternoon (it is difficult to establish the precise time, but it was probably around 5:00 p.m.). One of the bridges was found intact, but blocked by rubble and covered by enemy fire from the far bank.44 The bridgeheads which the Corps order had required the British divisions to establish were not obtained.

The armoured cars had been little if at all in advance of the infantry. On the Canadian front The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders were the first battalion to enter the city; Sherbrooke Fusiliers tanks went with them. At 1:35 p.m. the 9th Brigade signalled, “My Sunray [commander] reports that he is in the centre of Caen with Sunray of SD & G. Highrs.”45 In the meantime, the units of the 8th Brigade, supported by the 10th Armoured Regiment, had completed the occupation of Carpiquet airfield;†46 there was little opposition and the troops were reported on their objectives at 11:15 a.m.47

Thus at long last, thirty-three days later than prescribed in the original plan, Caen was in Allied hands. The city was a painful spectacle. Virtually the whole

* Part of this unit, including its headquarters, was still in England.

† The code name for this part of the operation was TROUSERS. At 7:40 p.m. on 8 July Tactical HQ 3rd Canadian Division had signalled, “TROUSERS off until tomorrow.”

of the central area had been destroyed on 6 and 7 June by Allied bombing designed to interfere with German movements by road and rail; and, as we have seen, the northern areas suffered equally in the great attack on the evening of 7 July. Happily, however, one portion of the city had been little damaged. This was the “island of refuge” about the great church of St. Etienne (Abbaye-aux-Hommes) and the Hôpital du Bon Sauveur. As early as 12 June, it appears, the Resistance forces and the French authorities in Caen contrived to send messengers through the lines to the British command, informing it that thousands of refugees were gathered in this area and begging that it should be protected. The French record that assurances were duly given, and in fact this part of the city went almost untouched during the struggle, and great numbers of lives were saved in consequence.48

In spite of their dreadful experience, the people of Caen greeted their liberators in a manner which our troops found very moving. And the Caennais were apparently particularly delighted to find their city freed in part by men from Canada. The historians of Caen during the siege thus describe the events of 9 July:49

At 2:30 p.m., at last, the first Canadians reached the Place Fontette, advancing as skirmishers, hugging the walls, rifles and tommy guns at the ready.

All Caen was in the streets to greet them. These are Canadians, of all the Allies the closest to us; many of them speak French. The joy is great and yet restrained. People—the sort of people who considered the battle of Normandy nothing but a military promenade—have reproached us for not having fallen on the necks of our liberators. Those people forget the Calvary that we had been undergoing since the 6th of June.

No Canadian unit recorded any complaint of the warmth of the welcome; and the 1st Corps situation report for the day remarked, “Inhabitants enthusiastic at Allied entry.”50

The people of Caen had suffered; the liberators had suffered too. The final phase of the battle for the city had been as bloody as its predecessors. The losses of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada on 8 July have already been noticed (above, page 161); no other unit lost so heavily, but the three battalions of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade together had 547 battle casualties on 8 July and 69 more on the 9th. Total Canadian casualties for the theatre on the two days were 1194, of which 330 were fatal.51 This was heavier than the loss on D Day.

Although the greater part of Caen had been liberated, the enemy was still in the southern quarters of the city, across the Orne. The only foothold the Allies possessed beyond the river was that seized by the airborne troops on 6 June. The task of breaking out into the open country to the south-east, so long desired by the air forces for airfields, was still ahead.

The German divisions that had fought for the Caen bridgehead were mere shadows when they retired across the Orne. Panzer Group West reported on 8 July, before the evacuation, that the infantry of the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division west of the Orne had “suffered 75% casualties”.52 Army Group D recorded next day that every one of this division’s battalion commanders in the bridgehead had been killed or wounded. As for the much more formidable 12th SS Panzer Division, it was in almost equally sad case. Army Group D set down on 9 July that the division’s total infantry strength now equalled only that

of one battalion; most of the anti-tank guns had been destroyed by enemy fire, and on 8 July alone 20 of the division’s tanks had become total losses. At the beginning of the invasion, as we have seen, the 12th SS Panzer Division had possessed 150 tanks (above, page 129). It had now lost 65 of them: 44 long-gun Mark IVs and 21 Panthers.53 It was, in fact, little more than a remnant; yet the remnant was still to give us much trouble before the Normandy campaign was over. On 11 July it handed over the Caen sector to the 1st SS Panzer Division and was withdrawn to refit.54

The Situation After the Capture of Caen

It is time to survey again the situation in the bridgehead as a whole.

On 3 July the First US Army had duly launched the offensive on the western portion of its line which General Montgomery’s directive of 30 June had ordered. The advance was hampered by bad weather and by difficult terrain—the bocage country, intersected by formidable hedgerows, being very unsuitable for armour and favourable to the defence. Nevertheless the American troops clawed their way forward, and after the first stage the Germans, realizing that this was a major offensive, began to move important formations westward to help stem the tide.55

On 8 July, the day on which the final British attack on Caen was launched, Hitler issued to the Commander-in-Chief West a new and comprehensive directive for the next phase of operations.56 This observed that the enemy’s next action would probably be “a thrust forward on both sides of the Seine to Paris”. The Führer proceeded, “Therefore, a second enemy landing in the sector of Fifteenth Army, despite all the risks this entails, is probable; all the more so, as public opinion will press for elimination of the positions for long-range fire on London.”* Attacks to gain an important harbour in Brittany, or on the Mediterranean coast, were also possible. Circumstances, the dictator went on, excluded for the present a major German attack intended to destroy the Allied bridgehead; but it was essential to prevent any substantial enlargement of it. Therefore the present front was to be held. However, “The mass of the mobile formations must be relieved by the infantry divisions which have arrived or are still arriving from time to time, and must thereafter be assembled in readiness for action as tactical reserves.” Relief of the 12th SS Panzer Division was specified as particularly necessary in the near future. After the mobile formations had been thus relieved and reorganized, “an operation with limited objectives” was to be prepared by Panzer Group West, the aim being to drive a wedge into the bridgehead by a surprise thrust, to split it as far as possible, to inflict losses on the Allied forces and to create favourable conditions for further operations. Hitler ordered that the strong reserves behind the Fifteenth Army’s coastal front were to remain there “until such time as it can be ascertained whether the American Army Group is

* On the German V-weapons, see below, pages 354-5.

going to undertake another landing operation, or whether its forces will follow Montgomery’s Army Group into the present beachhead”.

Recent history now repeated itself. Throughout the campaign the Germans had been struggling to withdraw from the line enough armour to form a mobile reserve capable of a counter-offensive; but all such attempts had been frustrated by Allied thrusts which could only be countered by sending the tanks in again. Now part of the armour withdrawn from the British sector had to be committed on the American front in an attempt to stop General Bradley. On 7 July, after discussion between Kluge and Rommel, the Panzer Lehr Division was ordered west. It came into action against the Americans on 11 July. The greater part of the 2nd SS Panzer Division was already fighting them.57

This development, so inimical to his policy of pinning German strength on the eastern flank, naturally disturbed General Montgomery. On 8 July a 21st Army Group intelligence summary, reporting movements which it correctly interpreted as indicating the switch of Panzer Lehr, remarked: “Opposite the American Army is the equivalent of some seventy battalions of infantry supported by 250 tanks.” This was a material change as compared with the situation little more than a week earlier (above, page 151). On 10 July Montgomery took note of it in a new directive to his Army Commanders.58 His deduction was, “It is important to speed up our advance on the western flank; the operations of the Second Army must therefore be so staged that they will have a direct influence on the operations of the First Army, as well as holding enemy forces on the eastern flank.” He proceeded to emphasize the importance of gaining possession of the Brittany peninsula, which was essential from an administrative point of view; of gaining “depth and space” on the eastern flank, “for manoeuvre, for administrative purposes, and for airfields”; and of engaging the enemy unceasingly to reduce his strength (“generally we must kill Germans”).

On the Second British Army front Montgomery asked for a bridgehead opposite Caen but only if it could be gained “without undue losses”. West of the Orne, on the other hand, the Army would “immediately operate strongly in a southerly direction, with its left flank on the Orne”, its objective being the general line Thury Harcourt-Mont Pingon-Le Beny Bocage. During this advance southward it was to secure bridgeheads east of the Orne between Caen and Falaise; and it was to retain the ability to be able to operate with a strong armoured force east of the Orne in the general area between Caen and Falaise. “For this purpose a Corps of three armoured divisions will be held in reserve, ready to be employed when ordered by me.”

This directive contained a number of points of particular Canadian interest. It placed the 2nd Canadian Corps under command of the Second Army. And it contained the following passage:

A study will be made as to when the northern portion of the eastward front, i.e., from the sea as far as Caen and possibly south of Caen, could profitably be transferred to First Canadian Army. First Canadian Army will study to what extent command of this eastward front so transferred could be exercised at an early date with comparatively limited resources in Army troops.

The result of these studies will be reported verbally to me; meanwhile no action will be taken as to phasing forward units of First Canadian Army HQ or Army Troops until I have further considered the problem.

For the First US Army Montgomery prescribed a continuance of operations along the same line indicated on 30 June (above, page 151). When its advance reached the base of the peninsula at Avranches, the right-hand Corps (the 8th), to consist of three infantry divisions and one armoured division, was to be turned westwards into Brittany. The directive repeated the intention of directing “a strong right wing” south of the bocage country towards the line Le Mans-Alençon. The headquarters of the Third US Army was to be “stepped forward” in rear of the 8th Corps, “so that it can take direction and control of the operations on the extreme western flank when so ordered”. This army would have the task of clearing the whole of the Brittany peninsula.

In accordance with these instructions the Second British Army now returned to the offensive west of the Orne. The first task (Operation JUPITER)—was to break out of the tiny bridgehead across the Odon established in the last week of June. On 10 July the 43rd Division attacked out of the bridgehead and got a foothold on Hill 112, a height which had dominated it. The Germans, who had attached the greatest importance to the hill, counter-attacked fiercely with many tanks and succeeded in preventing the British from gaining full possession of it and from capturing the village of Maltot to the east. The 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade was under the 43rd Division for this operation but played only a secondary role. On 13 July Headquarters 8th British Corps handed the sector over to the 12th Corps, newly arrived from England, and withdrew into reserve to prepare for the operation east of the Orne with three armoured divisions, forecast in General Montgomery’s directive.59

General Simonds’ 2nd Canadian Corps had now entered the line. At 3:00 p.m. on 11 July it took over about 8000 yards of front in the Caen sector; with the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions, the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade and the 2nd Canadian Army Group Royal Artillery under command.60

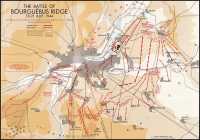

Operation GOODWOOD: The Battle of Bourguébus Ridge

The succeeding phase, centring upon the great armoured operation by the 8th British Corps south-east of Caen on 18 July, has been prolific of discussion. Field-Marshal Montgomery has written that these operations “gave rise to a number of misunderstandings at the time”, and various post-war publications have added fuel to the fire of the controversy. The aim of the present account is to summarize the essentials of the situation without going into great detail.

The issue turns upon Montgomery’s intentions. General Eisenhower in his post-war report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff described the operation as “a drive across the Orne from Caen toward the south and southeast, exploiting in the direction of the Seine basin and Paris”. This appears to be a misinterpretation of Montgomery’s plans, although it was perhaps not difficult to read some of his communications to the Supreme Commander at the time in this sense. The Germans,

as we have seen (above, pages 150 and 164), assumed that the object of our strategy was a break-out on the eastern flank in the direction of Paris. It has already been amply demonstrated that this was never Montgomery’s policy.

On 12 July Montgomery telegraphed to Eisenhower61 stating that the operation by the three armoured divisions mentioned in his directive of the 10th would now take place on Monday the 17th. He wrote:

Grateful if you will issue orders that the whole weight of the air power is to be available on that day to support my land battle. We must have the air to ensure success so good weather is essential and we will wait for it if Monday is bad. My whole eastern flank will burst into flames on Saturday and the operation on Monday may have far reaching results. ...

The following day the Army Group Commander sent a further personal message62 to Eisenhower:

Am going to launch two very big attacks next week. Second Army begin at dawn on 16 July and work up to the big operation on Tuesday 18 July when 8 Corps with three armoured divisions will be launched to the country east of Orne. Note change of date from 17 to 18 July. First Army launch a heavy attack with six divisions about 5 miles west of St. Lô on Wednesday 19 July. The whole weight of air power will be required for Second Army on 18 July and First Army on 19 July. ...

It has been plausibly suggested63 that these messages, whose main function, clearly, was to impress SHAEF with the importance of overwhelming air support, actually misled the Supreme Commander as to the aims of the operation. Other documents give a somewhat different impression of Montgomery’s intentions.

On 14 July Montgomery wrote to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff64 pointing out that while his infantry divisions had had heavy casualties and would be worse off “after the manpower situation begins to hit us”, his three armoured divisions were “practically untouched”. He proceeded:

And so I have decided that the time has come to have a real “show down” on the eastern flank, and to loose a corps of armoured divisions in to the open country about the Caen-Falaise road.

We shall be operating from a very firm and secure base. The possibilities are immense; with 700 tanks loosed to the SE of Caen, and armoured cars operating far ahead, anything may happen. ...

Later in the letter he again wrote, “Anything may happen”, adding however that it was necessary to “be certain that we do nothing foolish, and so let ourselves open to a German comeback which might catch us off our balance and lead to a setback. The basic fundamentals of policy are as stated in paras 2, 3, 4, 5, of M 510,* and the Brittany Peninsula is essential for us; but we may well get it by a victory on the eastern flank.”

On the same day (14 July) General Montgomery sent his Military Assistant, Lt.-Col. C. P. Dawnay, to explain his plans at the War Office. A record of his

* The directive of 10 July (above, page 165). Paragraph 2 reiterated the principle of drawing the main enemy forces into battle on the eastern flank “so that our affairs on the western flank may proceed the easier”. Paragraphs 3 and 4 are quoted on page 165, beginning “it is important...” Paragraph 5 emphasized the importance of both armies attacking the enemy “hard and continuously” and capturing or killing his troops in large numbers,

conversation with the Director of Military Operations65 contains the following passage:

General Montgomery has to be very careful of what he does in his eastern flank because on that flank is the only British Army there is left in this part of the world. On the security and firmness of the eastern flank depends the security of the whole lodgement area. Therefore, having broken out in country southeast of Caen he has no intention of rushing madly eastwards, and getting Second Army on the eastern flank so extended that that flank might cease to be secure.

All the activities on the eastern flank are designed to help the forces in the west while insuring that a firm bastion is kept in the east. At the same time all is ready to take advantage of any situation which gives reason to think that the enemy is disintegrating.

On 15 July General Montgomery gave General Dempsey a written memorandum on the operation, and Dempsey passed on a copy of it to General O’Connor, GOC 8th Corps.66 This specifically defined the object of the operations as follows:

To engage the German Armour in battle and ‘write it down’ to such an extent that it is of no further value to the Germans as a basis of the battle.

To gain a good bridgehead over the Orne through Caen, and thus to improve our positions on the eastern flank.

Generally to destroy German equipment and personnel, as a preliminary to a possible wide exploitation of success.*

The initial operations of the 8th Corps were thus defined in the same document:

The three armoured divisions will be required to dominate the area Bourguébus-VimontBretteville [sur-Laize], and to fight and destroy the enemy. But armoured cars should push far to the south towards Falaise, and spread alarm and despondency, and discover ‘the form’.

Subsequently, but only after the Canadian Corps had established a “very firm” bridgehead on the general line Fleury-Cormelles-Mondeville, the 8th Corps might “‘crack about’ as the situation demands”.

Finally, it is relevant to cite the intention of the operation as defined in the 2nd Canadian Corps’ Operation Instruction No. 2, dated 16 July, which undoubtedly reflects the views of Headquarters Second Army:

Army Plan

To draw enemy formations away from First US Army front by attacking southwards with 1, 8, 12, 30 and 2 Canadian Corps.

These excerpts serve to establish Montgomery’s aims. It is clear that he had not changed his basic policy of striking the main blow on the western flank, and the armoured operation east of the Orne was intended to assist the Americans. Nevertheless, it is equally clear that he was prepared to exploit to the full any breakthrough which might occur east of the Orne, and it seems quite possible that in fact he hoped for a deeper penetration here than that which was finally achieved.

* The last ten words are missing in two published versions; but they are present in a copy signed personally by Montgomery and passed to his Chief of Staff.

It is time to consider the plan in more detail. The attack east of the Orne was to be preceded by preliminary operations west of the river. On the night of the 15th-16th the 12th Corps, with the 15th Division, was to advance to take high ground south of Evrecy, south of the Odon bridgehead; and on the 16th the 30th Corps was to attack with the 59th Division to capture other heights about Noyers, west of the Odon. Thus the Second Army would work southward as already instructed with its left flank on the Orne, and would draw the enemy’s attention, it was hoped, from the forthcoming operations east of the river. Then the main attack (Operation GOODWOOD) would be let loose on the morning of 18 July. The 8th Corps, with the 7th, 11th and Guards Armoured Divisions under command, would cross the Orne through the “airborne bridgehead” and push forward towards the high ground to the south. On the left, the 1st British Corps was to establish a division in the Troarn area, and on the right the 2nd Canadian Corps would have the task of capturing the portions of Caen beyond the Orne and establishing a firm bridgehead in the country beyond. The Canadian portion of the operation was known by the code name ATLANTIC.67

A very powerful blow by the heavy bombers was to clear the way for the armoured advance. The experience of CHARNWOOD was reflected in this portion of the plan. This time the bombers—the actual number attacking was 1599 heavy plus many medium and light ones—were to attack at first light, immediately before the ground advance. The heavy night bombers, using delayed-action high-explosive bombs, struck at targets in the Colombelles and Touffreville-Emieville areas (along the flanks of the front of attack) and in the vicinity of Cagny. The heavy day bombers’ targets, attacked with fragmentation bombs with instantaneous fuzes (to avoid cratering which might hinder our tanks) were more distant areas. The mediums, using fragmentation bombs, attacked the central area across which the 8th Corps was to move. No. 83 Group RAF went for enemy defended localities and gun areas upon the flanks. To avoid the possibility of British troops being bombed in error, the forward positions were evacuated before the attack.68

The operations by the 12th and 30th Corps (respectively GREENLINE and POMEGRANATE) duly went in on 15 and 16 July. Both met heavy opposition and made only limited progress. Neither Noyers nor Evrecy was actually taken. The most useful result of these operations was to pull back into or retain in the line much of the armour which the Germans had been striving to organize for a counter-offensive. The 9th and a great part of the 10th SS Panzer Divisions were heavily engaged. Nevertheless on the eve of GOODWOOD the Germans still had armoured reserves available to meet it. The decimated 12th SS Panzer and portions of the 21st Panzer and 10th SS Panzer were out of the line; and the 1st SS Panzer was in a position of readiness astride the Falaise road just south of Caen.69

The air attack preceding the 8th Corps advance on 18 July was described by Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory in his dispatch written in the following November as “the heaviest and most concentrated air attack in support of ground forces ever attempted”. He added that “the total tonnage of bombs dropped reached 7,700 US tons”. The “counter-flak” fire of our artillery, hammering the

enemy’s anti-aircraft positions while the bombing was in progress, doubtless contributed to keeping the air forces’ losses down; but six RAF bombers were lost. This fire merged into a counter-battery programme carried out by 15 field, 13 medium, three heavy and two heavy anti-aircraft regiments. Again the Royal Navy’s big guns supported the army; the monitor Roberts and the cruisers Enterprise and Mauritius bombarded during 18 July and the next day.70

To avoid arousing the enemy’s suspicions, only one armoured brigade (the 11th Armoured Division’s) crossed into the bridgehead east of the Orne before H Hour. During the air programme this brigade began moving southward from the vicinity of Escoville, and the operation was on. In the first stage comparatively little opposition was met, and many of the enemy in the forward area were found to have been so dazed by the bombing as to be unable to resist. However, in the course of the morning, as the advance proceeded beyond the straight line of railway running from Caen to Vimont, losses began to mount. German tanks came into action, anti-tank guns were active and by midday the 11th Armoured Division’s tanks, after advancing some 12,000 yards, were stopped. On the left, the Guards Armoured Division was meeting resistance on a similar scale; while the 7th Armoured Division, whose task it was to move up behind the 11th and operate in the centre, was moving forward slowly and had not really got into action. At the end of the day, on the 8th Corps front, the Germans still held the villages of Bras, Hubert-Folie and Soliers; the Guards Armoured Division had taken Cagny. On the 1st British Corps front, the 3rd British Division had captured Touffreville and Sannerville. During the day the 11th Armoured Division had lost 126 tanks damaged or destroyed and the Guards Armoured Division 60 tanks.

Before attempting an account of the Canadian part in the operation, it may be well to note the later developments on the 8th Corps front. During 19 July the three armoured divisions fought their way forward in the face of fierce opposition. On this day the 11th Armoured Division lost 65 more tanks. By evening the British had Bras, Hubert-Folie and Soliers; the Germans were still in Bourguébus, La Hogue and Frénouville. On the 1st Corps front, the 3rd British Division had been stopped just short of Troam. There was slight further progress on 20 July. No ground was gained on the 1st Corps front, but the 8th took Bourguébus and Frénouville. The Germans continued to hold La Hogue and positions in the woods and villages running thence north-east towards Troarn. Here the 8th Corps operations came to a stand.71

Operation ATLANTIC: The Capture of Colombelles and Vaucelles

The 2nd Canadian Corps’ operation instruction for Operation ATLANTIC, issued on 16 July,72 prescribed that the Corps would capture Faubourg de Vaucelles, bridge the Orne in the Caen area and “be prepared to exploit to capture, in succession” high ground north of St. André-sur-Orne and the commanding village of Verrières, closely overlooking the main road to Falaise. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was to pass two brigades across the river and attack

with them south-westwards from the Ranville area through Colombelles and Vaucelles. This’ task fell to the 8th and 9th Brigades, while the 7th remained in reserve west of the Orne, ready to put a battalion across it through Caen. The 8th Brigade was to lead the advance east of the river, capturing Colombelles, Giberville and Mondeville; the 9th would then pass through to clear Vaucelles. The task of exploitation southward was to be carried out by the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, which proposed to use the 4th. Brigade to reconnoitre up to the Orne, and, if it proved practicable, to cross it and seize the high ground near St. André. The 5th Brigade was to cross at Caen and take the St. Andre feature if it had not already fallen to the 4th. The 4th had the particular task of capturing Louvigny, on the Orne near the mouth of the Odon, and preventing any interference from west of the Orne with the 5th Brigade’s crossing. The subsequent advance southward would be the business of the 4th or the 6th Brigade as circumstances might dictate.73

On the evening of 17 July the 8th Brigade moved across the Orne to its assembly area near Le Bas de Ranville. At 7:45 a.m. the following morning it moved off, with Le Régiment de la Chaudière on the right, nearer the river, and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada on the left, astride the road into Colombelles. The two battalions crossed the start-line about eight o’clock, with The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment coming on in rear and the leading elements of the 9th Brigade, which had begun to cross the Orne bridges at H Hour, following in their turn. A barrage fired by four field regiments covered the advance.74

Trouble began shortly. At 10:40 the Chaudière was reported held up by fire from the woods and château above the Orne at Colombelles. On the left the Queen’s Own “lost the barrage” when the latter moved left on a new axis towards Giberville; for the battalion was held up by snipers and machine-guns in the vast steelworks of Colombelles to its right, whose tall chimneys had long been landmarks in the battle area and had undoubtedly afforded the Germans excellent observation. (Several of these chimneys, however, had lately been demolished by the enemy himself, probably in anticipation of losing the area.)75 The steelworks had been one of the Bomber Command targets and were much battered; but the Germans were still firing from the ruins. Assisted by tanks of the 1st Hussars, the Queen’s Own cleared the area of the cross-roads east of Colombelles; then tanks and infantry moved against Giberville. Here the battalion became involved in a slow and painful fight through the village, constantly hampered by continuing fire from the factory area. By late afternoon several hundred prisoners had been taken in and around Giberville.76

On the right the situation was still more difficult. The Chaudière was held up in front of the château, and the North Shore Regiment and the units of the 9th Brigade, closing up behind it, produced much confusion. The North Shore Regiment tried to advance along the steep river bank north of the château but was again held up, as were The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders when they attempted to push through Le Régiment de la Chaudière. Shortly after noon the Chaudière was ordered to withdraw to permit bombardment of the château. At 1:30 it was reported that an air attack had been unsuccessful

(“Bombs bounced over Château owing to hard ground”).77 At 2:40 p.m. the fire of all the guns supporting the division was brought down upon the place. Unfortunately some shells fell among our own troops and contributed to disorganizing further a situation which was already badly confused. However, at 3:18 the château was reported on fire, and thereafter the Chaudière at last succeeded in breaking in.78

At 4:35 p.m. General Keller issued new orders.79 The North Shore was to clear the steelworks. The 9th Brigade would by-pass this obstacle, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders moving along the river bank to Vaucelles and the Glengarrians moving on the southern flank against Mondeville. The attack now recovered its momentum. The North Shore Regiment launched its attack against the steelworks (necessarily an improvised effort) about 6:00 p.m. Fortunately a sudden rainstorm spoiled the visibility as the companies moved across open fields to close with the enemy ensconced among the huge shattered buildings. The Germans remaining were few in number, but some of them fought grimly through the night and were not finally eliminated until daylight. Off to the south-east, the Queen’s Own completed the clearing of Giberville, defeated an evening counter-attack and pushed on to the railway line south of the village. By 9:30 p.m. the battalion was on all its objectives.80

Meanwhile the 9th Brigade’s units forged slowly forward. The SD and Gs. were hung up overnight in Colombelles, but the North Nova Scotias entered the outskirts of Vaucelles shortly before midnight. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, following on, had trouble getting past the factory area, where its temporary Commanding Officer, Major G. A. M. Edwards, was wounded. The two units consolidated for the night in the eastern part of Vaucelles.81

When in the course of the morning it had become evident that the 9th Brigade would be delayed in getting into the Faubourg de Vaucelles, General Simonds directed Brigadier Foster of the 7th Brigade, which was in readiness in Caen, to send a patrol across the river and follow up with a battalion if there was no opposition. The Regina Rifle Regiment’s scout platoon crossed by way of partially destroyed bridges, and met only light resistance. About 5:15 p.m. the rest of the battalion began to cross, covered by artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire. The whole of it was well established in Vaucelles within a few hours.82

On the right of the 2nd Canadian Corps front, during 18 July, Major-General Foulkes’ 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was having its first day in action since Dieppe. The attack by the 4th Infantry Brigade against Louvigny, west of the Orne, began early in the evening, and by nightfall The Royal Regiment of Canada had cleared the orchards immediately north of the village. During this fighting the brigade commander, Brigadier Sherwood Lett, who had been wounded at Dieppe, was again wounded. Lt.-Col. C. M. Drury took over temporarily, and Lt.-Col. F. A. Clift of The South Saskatchewan Regiment acted thereafter until 24 July, when Lt.-Col. J. E. Ganong took command of the brigade.83 While the enemy was occupied with the 4th Brigade, the 5th (Brigadier W. J. Megill) came into action. At 10:15 p.m. The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment)

of Canada began crossing the Orne from Caen into the western end of Vaucelles against light opposition. During the night contact was established with The Regina Rifle Regiment.84 The way was now clear for the engineers to begin bridging.

The Army plan required the 2nd Canadian Corps to bridge the canal and the Orne at Herouville, close to Colombelles, and subsequently the river at Caen itself. The enemy’s tenacity at Colombelles frustrated an attempt at Herouville on the morning of the 18th, the 3rd Division’s engineers being forced to give up after suffering numerous casualties. Another effort in the evening was ended by heavy mortar fire.85 Shortly after midnight, however, the Corps and 2nd Division engineers began work at Caen. Within 12 hours they had completed one bridge (at the main road-crossing) capable of bearing tanks, a tank-carrying raft just above the city, a smaller bridge nearby, and another in the dock area.86 This feat was very important in its bearing on the southward extension of the offensive. The bottleneck at Ranville, which inevitably had interfered to some extent with the deployment of the 8th Corps on the morning of 18 July, was no longer a menace.

Canadian Operations on 19 July

On 19 July the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was able to complete its initial task without heavy fighting. Before dawn the 9th Brigade began the task of clearing Vaucelles of such enemy as remained, chiefly snipers. This was finished by midday.87 The Corps Commander’s intention for the next phase was that the 3rd Division should reorganize and should capture Cormelles, an industrial suburb east of the main road to Falaise (which was now the boundary between the 2nd and 3rd Divisions), while west of the road the 2nd Division was to take Fleurysur-Orne, the high ground between it and St. André, and the village of Ifs.88

After a conference held by the Corps Commander about 11:00 a.m., the 7th Brigade, the balance of which was then crossing into Vaucelles, was directed to take Cormelles. However, since there was a report that the place might be unoccupied, and the opportunity might be fleeting, The Highland Light Infantry of the 9th Brigade was ordered to move into Cormelles at once. This led to some confusion between the two brigades, and in the course of the operation there were again complaints of our troops being shelled by our own artillery. The HLI got two companies into Cormelles in the late afternoon, and in the evening the battalion was relieved there by the 1st Canadian Scottish Regiment and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles.89

West of the great road, in the 2nd Division sector, the 5th Brigade’s attack on Fleury-sur-Orne began badly when Le Régiment de Maisonneuve’s two leading companies formed up on the opening line for their supporting barrage instead of their assigned start-line. The result was that these companies took the full weight of our own shellfire and were disorganized. However, the Commanding Officer, Lt.-Col. H. L. Bisaillon, ordered the other two rifle companies forward and they seized the village with little opposition. In the next phase The Calgary Highlanders passed through the Maisonneuves late in the afternoon and, in spite of considerable

mortar fire, took and consolidated their objective on “Hill 67”, the knoll looking down on St. André-sur-Orne from the north. That night The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada moved against Ifs. It had to deal with several counter-attacks before the village was finally secure the following morning. In the meantime, west of the Orne, The Royal Regiment of Canada had completed the capture of Louvigny on the morning of the 19th.90

The Last Phase of ATLANTIC

By the evening of 19 July the 2nd Canadian Corps had almost completed its assigned task. Its responsibilities, however, were widened and increased as the 8th Corps armour began to withdraw following the check to its advance. Late in the afternoon of the 19th General Dempsey issued orders for the Canadian Corps to take over Bras from the armour “as soon as possible”, and about 10:00 a.m. the following day he directed that the 8th Corps was not to continue the advance for the time being, except that the 7th Armoured Division was to complete the capture of Bourguébus. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was to relieve the heavily-damaged 11th Armoured Division.91 The 2nd Canadian Corps intention for the day, apart from carrying out this relief, was that the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division should carry the advance southward and establish itself on the “Verrières feature”. Brigadier H. A. Young’s 6th Infantry Brigade, which had not yet been engaged, was brought forward for this phase, with the Essex Scottish from the 5th Brigade placed under its command.92

Three miles or so south of Caen the present-day tourist, driving down the arrow-straight road that leads to Falaise, sees immediately to his right a rounded bill crowned by farm buildings. If the traveller be Canadian, he would do well to stay the wheels at this point and cast his mind back to the events of 1944; for this apparently insignificant eminence is the Verrières Ridge. Well may the wheat and sugar-beet grow green and lush upon its gentle slopes, for in that now half-forgotten summer the best blood of Canada was freely poured out upon them.

The ridge is kidney-shaped, with one end close to the road just north of the farm hamlet from which it takes its name, and the other descending towards the Orne above the village of May. It is an important tactical position, rising as ‘it does to a height of 88 metres and dominating the lower ground to the north. On the morning of 20 July the 6th Brigade was moving south across the Orne preparatory to attacking this feature. Simultaneously, British troops of the 7th Armoured Division from east of the great road were already approaching it. Tanks of the 4th County of London Yeomanry and a company of the Rifle Brigade pushed across the road, supported by the 8th Corps artillery, but met heavy opposition and failed to take the ridge. Two different formations were now being directed upon the same objective. After consultation between the headquarters of the 8th and the 2nd Canadian Corps, it was arranged that the 6th Brigade would attack the position. The British tanks would withdraw east of the road and support the brigade’s advance with fire.93

The units of the 6th Brigade crossed their start-lines, running from south of

Ifs to Point 67, at 3:00 p.m., while British and Canadian artillery fired concentrations on targets in front and Typhoon squadrons also struck at the enemy as targets offered. The Cameron Highlanders of Canada were on the right, directed upon St. André-sur-Orne, The South Saskatchewan Regiment in the centre directed against the middle part of the ridge, and Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal on the left had as their objective Verrières. Two squadrons of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment were available for counter-attack, one allotted to the Camerons and one to the Fusiliers. No tanks actually accompanied the attacking infantry.94

Although good progress was made in the initial stages, the day was not to end without a bloody reverse. The Camerons duly got a foothold in St. André and kept it, but were subjected to a series of strong counter-attacks as well as to very heavy fire from west of the Orne, where the enemy, with part of Hill 112 still in his hands, had excellent observation. Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal took Beauvoir and Troteval Farms, but thereafter came under a storm of fire and were unable to push on up the slope to Verrières.95

It was in the centre that the 6th Brigade suffered its setback. The South Saskatchewan Regiment, after overcoming considerable opposition, reported two companies on their objectives, at 5:32 p.m. Half an hour or so before this time the weather had broken and a violent downpour of rain began, putting an end to all air support. The acting Commanding Officer, Major G. R. Matthews, ordered the battalion’s anti-tank guns, and those of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment which were in support, to come forward and dig in. But the guns were intercepted during the forward move by a small group of enemy tanks which suddenly appeared through the mist and rain from the direction of Verrières. The tanks then turned their machine-guns on the infantry. Attempts were made to use the PIAT, but the battalion, unsupported by heavy anti-tank weapons, was soon scattered and suffered very heavily. No message from it reached the 6th Brigade for more than two hours after 5:55 p.m., when it reported that it was being counter-attacked by tanks and asked for help. Many soldiers took refuge in the tall grain and made their way back during the night. None of our own tanks seems to have got into action. The South Saskatchewan had 208 casualties in this sad affair. Major Matthews was among the 66 officers and men who lost their lives.96

The Essex Scottish, who had had little sleep the night before and “little or no noon meal”,97 were ordered forward, at the moment when the leading elements of the South Saskatchewan were coming on to their objectives, to occupy the area between Beauvoir Farm and St. André. Before reaching it the battalion encountered men of the South Saskatchewan retreating. Enemy tanks and artillery fire now struck the Essex. Two of its companies are reported to have broken, it became disorganized and lost very heavily. But its main. body hung on in the area north of its assigned objective, and in the early hours of 21 July the two companies that had withdrawn, after being reorganized by the brigadier, were sent forward to rejoin it. In the meantime General Simonds had taken steps to secure his right flank against further enemy counter-attacks. The Black Watch, still in Ifs, were placed under Brigadier Young’s command, and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade was assigned to the 2nd Division.98

The heavy rain which had begun to fall during the afternoon of the 20th continued through the night and the following day. On the morning of 21 July the reinforced enemy, who had been putting in counter-attacks during the hours of darkness, launched a larger effort with tanks and infantry against the 6th Brigade’s shaken centre. The remnant of the South Saskatchewan had been withdrawn to reorganize. The enemy broke into the positions of the Essex Scottish, who suffered further heavy casualties, and a deep salient was created between the Camerons and Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal. The remnants of the Essex in the forward area were now ordered to withdraw, and at 6:00 p.m. the Canadian Black Watch, supported by tanks of the 6th and 27th Armoured Regiments and a formidable artillery programme, moved out from Ifs to counter-attack. The operation was successful, the lost ground was recovered, and the brigade front was stabilized roughly along the line of the lateral road connecting Troteval Farm and St. André. Troteval and Beauvoir Farms, however, were lost, and few men of the forward companies of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal came back. The Verrières Ridge remained in enemy hands.99 On the river flank this day saw further fierce counter-attacks against St. André by infantry and tanks. The Camerons and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers dealt with them successfully, but the Camerons had 81 casualties, 29 of them fatal.100

Operation ATLANTIC had been costly. The first day’s fighting had brought heavy losses to the 3rd Division, and on the succeeding days the inexperienced 2nd Division had had a very nasty baptism of fire. During the whole four days the nine infantry battalions of the 3rd Division suffered a total of 386 casualties, of which 89 were fatal. For the 2nd Division the comparable figures were 1149 casualties, with 254 men losing their lives. The units suffering most were, we have seen, the Essex Scottish, with 244 casualties (37 being fatal) and the South Saskatchewan, with 215, of which 62 were fatal. The Essex Scottish got a new commanding officer after the battle. In the 3rd Division the heaviest toll had fallen upon The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada (23 fatal casualties, 77 non-fatal) and Le Régiment de la Chaudière (20 fatal, 72 non-fatal), almost all suffered on 18 July. The total casualties of all the Canadian units in the theatre of operations, for the four days’ fighting, were 1965 in all categories; 441 men were killed or died of wounds.101

The Results of GOODWOOD and ATLANTIC

In the light of the heavy Canadian losses, an assessment of the value of the operations of 18-21 July east of the Orne is a matter of special interest.

Back at SHAEF in England the Supreme Commander found them disappointing. So did some of the officers around him, and not least Air Chief Marshal Tedder, who as we have seen had long been critical of Montgomery’s direction of the campaign. Tedder’s biographer quotes a letter102 which the Deputy Supreme Commander wrote to Eisenhower on 20 July:

An overwhelming air bombardment opened the door, but there was no immediate determined deep penetration whilst the door remained open and we are now little beyond the farthest bomb craters. It is clear that there was no intention of making this operation the decisive one which you so clearly indicated.

This was based upon a misconception of the nature of Montgomery’s plan. But we have seen that Montgomery’s communications to Eisenhower before the battle could certainly be interpreted as indicating that GOODWOOD was a breakthrough operation; and he does not seem to have sent the Supreme Commander a copy of his explanatory memorandum to Dempsey, or offered him such an exposition of his intentions as he gave the War Office in London.

Thus one distinguished British officer, Tedder, was encouraging the American Supreme Commander to put pressure on another distinguished British officer, Montgomery. Indeed, Eisenhower’s gossipy naval aide asserts that on the evening of 19 July Tedder told his chief that the British Chiefs of Staff “would support any recommendation” which the Supreme Commander might care to make with reference to Montgomery.103 On such a point the aide is obviously a doubtful source. But Eisenhower did put strong pressure on Montgomery. On the 20th he flew to Normandy and visited him,104 and on the 21st he sent him a letter, said to embody the substance of the previous day’s conversation, which is decribed as “the strongest he had yet written to him”.105 He wrote: “A few days ago, when armored divisions of Second Army, assisted by a tremendous air attack, broke through the enemy’s forward lines, I was extremely hopeful and optimistic. I thought that at last we had him and were going to roll him up. That did not come about.” Eisenhower demanded continuous strong attack by Dempsey’s army to gain terrain for airfields and space on the eastern flank. He mentioned that he was aware of the serious reinforcement problem which faced the British; but he observed, “Eventually the American ground strength will necessarily be much greater than the British. But while we have equality in size we must go forward shoulder to shoulder with honors and sacrifices equally shared.”106 This seems close to a complaint that the Anglo-Canadian forces are not pulling their weight.