Chapter 10: Normandy: Victory at Falaise, 12–23 August 1944

(See Map 5 and Sketches 16, 17, 18 and 19)

The German Counter-Offensive and the Allied Change of Plan

On 6 August General Montgomery had issued another directive1 covering the next phase of operations and reiterating the orders already given concerning the Canadian Army’s attack towards Falaise. It defined the intention for the future as “to destroy the enemy forces in that part of France” west of the Seine and north of the Loire. The plan was outlined as follows:–

6. a. To pivot on our left, or northern flank.

b. To swing hard with our right along the southern flank and in towards Paris, the gap between Paris and Orléans being closed ahead of our advance.

c. To drive the enemy up against the R. Seine, all bridges over which between Paris and the sea will be kept out of action.

The 12th Army Group was to clear Brittany, using no more troops than necessary, “as the main business lies to the east”, and to push its main force eastward to the Seine on a broad front. Montgomery was still planning for an airborne operation to secure the Chartres area ahead of the main advance, so as to block the enemy’s escape gap between Paris and Orléans. This was to be launched when the 12th Army Group had crossed the general line Le Mans-Alençon.

Immediately after this directive was issued, the picture was altered by the Germans’ great counter-thrust towards Avranches (above, page 213), which opened the prospect of cutting off and destroying the most formidable portions of their army in the west long before the Seine was reached. During the next two days the Allied commanders modified their plans to exploit this new situation.

Operation LÜTTICH went in on the night of 6-7 August (above, page 214). The divisions actively engaged were the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions and the 1st and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions.2 During the night and in the fog of early morning the Germans gained ground, capturing Mortain and some other places. But the First US Army stood and fought with skill and resolution; and as the mists cleared the Allies’ potent and flexible air weapon came flashing into action. Flying weather on that 7th of August was perfect. The fighter-bombers of the

RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force were called into the battle on the American front to reinforce the Ninth Air Force. No. 83 Group (under which the squadrons of No. 84 were still operating) flew 1014 sorties, and reported happily, “First really large concentration of enemy tanks seen since D Day was found north of Mortain during afternoon. Approximately 250 tanks were seen here and claims are 89 tanks destroyed, 56 damaged, while 104 mechanical transport vehicles were destroyed and 128 damaged.”3 Examination on the ground later indicated that these claims, as was not surprising in all the circumstances, were exaggerated;*4 but German testimony is unanimous that the air attacks were a major factor in stopping LÜTTICH in its tracks. The headquarters of the Seventh Army recorded that by noon the attack “had been brought to a complete standstill by unusually strong fighter-bomber activity”.5

On 8 August, with the Germans at Mortain contained and their great mass of armour there virtually immobilized for the moment, the Allied plan was changed. Until now, as we have seen, it had envisaged a large encirclement, driving the Germans back upon the Seine and cutting off their retreat by blocking the gap between the Seine at Paris and the Loire at Orléans. The high command now substituted a shorter encirclement designed to bring General Crerar’s and General Patton’s Armies together in the Argentan area south of Falaise, thus cutting off the German forces around Mortain.

The manner in which the new decision was reached and new orders issued can be pieced together from the accounts written by the senior commanders concerned, supplemented by certain available documents. On 8 August General Eisenhower was with General Bradley at the latter’s headquarters.6 According to the Supreme Commander, he assured Bradley that he could count upon an air transport service capable of delivering up to 2000 tons of supplies per day to any Allied force that might be temporarily cut off. This convinced Bradley that it was safe to retain only minimum forces at Mortain and concentrate upon driving his spearheads eastwards to carry out the envelopment which the situation promised. General Eisenhower writes: “I was in his [Bradley’s] headquarters† when he called Montgomery on the telephone to explain his plan, and although the latter expressed a degree of concern about the Mortain position, he agreed that the prospective prize was great and left the entire responsibility for the matter in Bradley’s hands.”7

Bradley accordingly issued orders whose essence was found in the sentence, “12th Army Group will attack with least practicable delay in the direction of

* A later figure for tanks destroyed is 84. The US Ninth Air Force claimed 69, raising the total to 153. Operational research teams from the 21st Army Group and Second Tactical Air Force found in the area 78 armoured vehicles, of which 21 had been destroyed by air action, 29 by the US ground forces, and 15 by unknown causes. Nine were abandoned intact and four destroyed by their crews. It may be noted that the British and US Tactical Air Force commanders had agreed that the RAF’s rocket-firing Typhoons should take on the tanks while the Ninth Air Force warded off enemy aircraft and attacked transport moving to and from the battle zone.

† Eisenhower’s diary gives a slightly different version: “On a visit to Bradley today I found that he had already acted on this idea and had secured Montgomery’s agreement to a sharp change in direction toward the Northeast instead of continuing toward the East, as envisaged in M-517 [Montgomery’s directive of 6 August]” (quoted in Pogue, The Supreme Command, 209).

Argentan to isolate and destroy the German forces on our front.” In detail, General Patton’s Third Army was ordered to “Advance on the axis Alençon-Sees to the line Sees ...—Carrouges ... prepared for further action against the enemy flank and rear in the direction of Argentan”.8 General Montgomery, according to Eisenhower, issued orders “requiring the whole force to conform to this plan”, and then met with Bradley and General Dempsey to coordinate the details.9 Montgomery confirms10 that on 8 August he ordered the 12th US Army Group to swing its right flank north on Alençon, while at the same time urging all possible speed on the first Canadian and Second British Armies in the movement towards Falaise. (He had a conference with Generals Crerar and Dempsey late in the afternoon of 8 August; but the nature of the orders he then gave is not recorded.)11 The manner in which the new decisions were reached illustrates the statement previously made (above, page 204) that there was an element of the committee in the Allied system of command during this month of August.*

On 9 August Patton’s leading troops bridged the River Sarthe near Le Mans. They then pushed north towards Alençon, which was reached on the night of the 11th–12th.12 The advance continued towards Argentan. On 11 August General Montgomery issued a new directive13 which confirmed the orders issued less formally on the 8th. It emphasized the predicament of the enemy forces about Mortain and the importance of closing the narrowing gap in the Falaise–Alençon area through which they could be supplied or could escape. Montgomery wrote:

6. It is definitely beginning to look as if the main battle with the German forces in France is going to be fought between the Seine and the Loire. This will suit us very well.

7. The enemy force that will require to be watched carefully is the main concentration of armour now in the Mortain area; it is a formidable force, and must be well looked after.

The orders for the 12th Army Group were in the same terms as those issued by Bradley on the 8th, requiring the right flank to swing up from Alençon to the general line Sees–Carrouges. The Second Army was to “advance its left to Falaise” as “a first priority, and a vital one”. The orders for the First Canadian Army ran:

10. Canadian Army will capture Falaise. This is a first priority, and it is vital it should be done quickly.

11. The Army will then operate with strong armoured and mobile forces to secure Argentan.

12. A secure front must be held between Falaise and the sea, facing eastwards.

While emphasizing the importance of making the “short hook” succeed, Montgomery still provided for executing the former plan in case the enemy should “escape us here”. The 12th Army Group was to continue to plan for an airborne operation against the Chartres area, which might have to be carried out at very short notice.

* In Normandy to the Baltic General Montgomery does not mention any consultation with Bradley before these orders were issued. The episode is not referred to in his Memoirs. General Bradley in his book does not mention consulting either Eisenhower or Montgomery. But General Eisenhower’s categorical accounts, quoted above, seem to be decisive unless some new evidence is produced

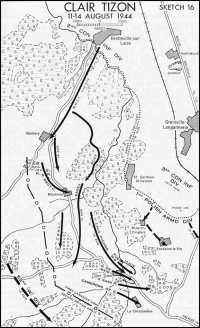

Sketch 16: Clair Tizon, 11–14 August 1944

Preparations for Operation TRACTABLE

Until 10 August the plan to which Headquarters First Canadian Army was working was that after capturing Falaise the Army would move east directed on Rouen and the Seine. That afternoon, however, General Montgomery instructed General Crerar to “swing to the east around Falaise and then south towards Argentan, at which point it is proposed to link up with the Third US Army”. During 11 and 12 August plans took shape for another great “set-piece” attack, with the heaviest scale of support, to break through towards Falaise. This operation, at first called TALLULAH, was redesignated TRACTABLE on 13 August.14

While the planning and preparation were in progress, the 2nd Canadian Division was engaged in a subsidiary operation on First Canadian Army’s western wing, undoubtedly intended to threaten the enemy’s positions astride the Falaise road by a flank movement and thereby lead him to weaken them before our main operation went in. On 11 August, as already noted (above, page 231), General Simonds directed General Foulkes to undertake what was called a “reconnaissance in force”15 southward from Bretteville-sur-Laize with one brigade, and the movement began that night. On the morning of the 12th, however, General Foulkes was told that his advance was to be, for the moment, the Corps’ main effort, and he was given the support of two Army Groups Royal Artillery and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade less one regiment. The whole 2nd Division was now committed to the operation.16

The advance was led by the 4th Infantry Brigade with the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment and the 27th Armoured Regiment under command. Barbery was reached during the night 11-12 August and the following morning the forward troops were on the high ground overlooking Moulines. These advances had cost some casualties, and more were suffered before The Royal Regiment of Canada captured Moulines, which was accomplished by last light on the 12th. Further progress was made next day; the 5th Brigade passed through the 4th, and The Calgary Highlanders, supported by artillery, established a small bridgehead on the east bank of the Laize at Clair Tizon. This was a decided threat to the main German position on the Falaise road; but when Le Régiment de Maisonneuve attempted to expand it on the evening of 13 August it was driven back with heavy loss by the Germans holding the commanding heights east of the river.17

The 2nd Canadian Corps produced no written orders for Operation TRACTABLE. General Simonds had a conference with his divisional commanders on 12 August and on the 13th held his orders group for the operation; map-traces were issued confirming and illustrating the instructions then given.18 After the group the Corps Commander spoke to the commanders of all armoured units in the Corps, demanding, in effect, more drive than had been shown in the recent operations:

He stressed the necessity for pushing armour to the very limits of its endurance and that any thought of the armour requiring infantry protection for harbouring at night or not being able to move by night was to be dismissed immediately. The tremendous importance of the operations now being undertaken could not be overlooked and although there would probably be cases of the mis-employment of armour this was to be no excuse for non-success.19

General Crerar issued on 13 August a directive to his Corps Commanders20 which was mainly limited to advising them of adjustments made since General Montgomery’s order of two days before. It was now intended that Second British rather than First Canadian Army would actually capture the town of Falaise, assisted by an adjustment of the inter-army boundary which would give the Second Army the road from Clair Tizon to Falaise. The object of TRACTABLE was defined as to dominate Falaise “in order that no enemy may escape by the roads which pass through, or near, it”. After the 2nd Canadian Corps had established itself on the high ground north and east of Falaise, and when the Second Army’s operations to capture the town were well advanced, the 2nd Corps would exploit south-eastwards and capture or dominate Trun.

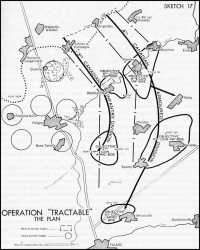

Faced with a problem basically the same as that which had confronted him in planning TOTALIZE, General Simonds decided to apply basically the same technique; but there were significant variations. Again the might of the strategic bomber forces was to be invoked in support of the attack. Again the armoured personnel carrier would be brought into use, and the main attack would be delivered by massed armoured columns including infantry carried in these vehicles. Again there would be no preliminary bombardment, for this would deprive us of any possibility of surprise. But this attack, unlike that a week earlier, was to be delivered in daylight. The protection from enemy fire which the night had given our columns in TOTALIZE was to be provided in TRACTABLE by smokescreens laid by the artillery along the front and flanks of the advance.

This heavy, highly-concentrated blow on a narrow front was to fall upon the German positions north of the Laison valley and east of the Falaise Road. It was to be struck by two columns, each comprising an armoured brigade followed by two infantry brigades. The forward infantry brigade would be borne in armoured carriers, the rearward one would march. The armoured brigades were to push straight across the Laison and on southwards to the high ground dominating Falaise. The infantry brigades carried in KANGAROOS would have the task of mopping up the Laison valley; the marching brigades, on the other hand, would be in readiness to pass through and hold the ground to the southward seized by the tanks. The right or westward column consisted of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division less the 8th Infantry Brigade, but with the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade under command. The latter brigade was now commanded by Brigadier J. F. Bingham, Brigadier Wyman having been wounded on 8 August. The leftward column was the 4th Canadian Armoured Division plus the 8th Infantry Brigade.21

Preparing this attack was a very large task, particularly as it involved moving nearly every fighting formation in the 2nd Canadian Corps during the 24 hours preceding H Hour. On 12 August Simonds reported to Army Headquarters that he expected H Hour to be noon on the 14th; although Corps would be “pressed for time”, it would be possible to put the operation in that day.22 This forecast proved accurate.

With the TOTALIZE precedent to help, the assistance of the RAF Bomber Command was obtained without any of the uncertainties that had accompanied

the earlier operation.*23 Sir Arthur Harris had said, “Don’t be shy of asking”, and the Canadians weren’t. On 13 August Army Headquarters issued an instruction covering the air plan.24 Immediately before H Hour medium bombers of No. 2 Group, 2nd Tactical Air Force, guided by red smoke fired by the artillery, would go for the German gun, mortar and tank positions in and around the Laison valley on the front of attack. Two hours after the advance began the heavies of Bomber Command would assail the positions astride the Falaise Road about Potigny and Quesnay Wood, which the ground attack was to bypass. This bombing was intended “to destroy or neutralize enemy guns, harbours, and defended localities on our right flank and to prevent any enemy movement from this area to the area of the attack”.25 The artillery would lay smoke screens on the flanks of the ground attack in Phase I, as already described, in addition to a barrage in front combining smoke shell and high explosive. Known enemy gun-positions would be bombarded from five minutes before H Hour, and the artillery regiments would be prepared to move forward to support the advance as it proceeded.26

Although we did not know it until afterwards, a serious misfortune befell us before the attack. On the evening of 13 August an officer of the 2nd Canadian Division’s 8th Reconnaissance Regiment, travelling in a scout car, lost his way and drove into the enemy’s lines. He was killed and his driver taken prisoner. On the officer’s body (we later learned from a prisoner) the Germans found a copy of a 2nd Division paper27 containing the gist of General Simonds’ orders as issued that day. It gave them full information concerning our plan of attack, and enabled them to make quick adjustments to deal with it. These included, apparently, disposing an additional anti-tank battery above the Laison on our line of advance. General Simonds expressed the opinion that these adjustments “undoubtedly resulted in casualties to our troops the following day, which otherwise would not have occurred, and delayed the capture of Falaise for over twenty-four hours”.28

It is worth noting that during training every opportunity had been taken to warn officers against exposing themselves to precisely this sort of mischance. After Exercise BUMPER, the great manoeuvres held in the United Kingdom in the autumn of 1941, the Chief Umpire (who incidentally was Lieut.-General B. L. Montgomery) emphasized the dire results of a similar incident which had happened during the exercise, and the unfortunate British officer involved was one of the few individuals mentioned by name in his critique.29

The Action of the Laison

The final regrouping for TRACTABLE went forward during the night of 13th-14th August. The Polish Armoured Division relieved the 3rd Canadian

* Army Headquarters, however, was decidedly dissatisfied at this time with the arrangements in effect for obtaining air support within the theatre, particularly when requests involved resources beyond those of the tactical group immediately supporting the Army. Brigadier Mann reported to General Crerar that existing practice “in effect results in the Senior Air Staff Officer 83 Group RAF becoming the adjudicator of the military necessity or desirability of a particular attack upon a particular target”, no matter how strongly or urgently the Army had put the case; he particularly complained of the delays involved.

Sketch 17: Operation TRACTABLE, The Plan

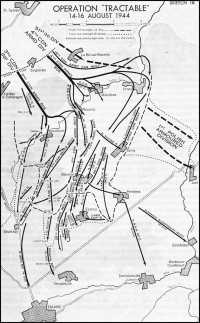

Infantry Division, which moved into position for its battle task.30 Special armour from the 79th Armoured Division arrived. During the morning of the 14th the columns formed up just over the horizon from the view of the enemy holding the positions north of the Laison.

The 3rd Division column, on the right, was headed by the tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, with British Flails in front. Then came the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment, then the 9th Infantry Brigade in armoured carriers,

The 7th Infantry Brigade on foot brought up the rear. Farther east the 4th Canadian Armoured Division was similarly formed up, with the 4th Armoured Brigade in front. In this case the 8th Infantry Brigade was the formation using the armoured carriers, and the 10th Infantry Brigade the one in rear. The 18th Canadian Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) protected the Corps’ left flank. The forming-up positions were on the road running from Bretteville-le-Rabet to St. Sylvain, and the start-line, to be crossed at H Hour, was a line running slightly north of Estrées-la-Campagne and through Soignolles.31 In the midst of the final preparations, a message from General Crerar32 to all commanders and commanding officers reminded the Army of the extreme importance of the present juncture and the present opportunity:

Hit him first, hit him hard and keep on hitting him. We can contribute in major degree to speedy Allied victory by our action today.

The 14th of August was a beautiful summer day. Those who saw it were to remember long the sight of the great columns of armour going forward “through fields of waving golden grain”.33 At 11:37 a.m. the artillery began to fire the marker shells for the benefit of the medium bombers; at 11:55 it commenced to lay the tremendous smoke-screens intended to shield our columns from enemy observation.34 At 11:40 the medium bombers began bombing the enemy positions, hitting Montboint, Rouvres and Maizières in that order. Sweeping in over the waiting tanks, they attacked the valley for a noisy quarter of an hour. Forty-five Mitchells and 28 Bostons actually bombed.35 At 11:42 wireless silence was broken by the command “Move now”; and the armoured brigades began to roll towards the start line.36

The artillery smoke-screen was designed to be “impenetrable” on the flanks and of the density of thick mist on the front.37 As soon as the armour moved, the smoke-clouds were supplemented by dust—“dust like I’ve never seen before!” was one unit commander’s phrase.38 The two things together made it extremely difficult for the drivers to keep direction, and there was little they could do except press on “into the sun”.39 The German gunners, fully alert and knowing in advance precisely the frontage on which we were going to attack, took their toll in spite of the smoke cover. One of their victims was the commander of the 4th Armoured Brigade, Brigadier E. L. Booth, who was mortally wounded when his tank was hit.*40 There were other casualties to the brigade headquarters, and the resulting disorganization had an adverse effect on the 4th Division’s subsequent operations.41

The armoured carriers bearing the infantry again showed themselves extremely valuable, boring straight through into the valley of the Laison where the riflemen jumped down and set to work clearing out the enemy. In general, the infantry task here was not formidable; large numbers of Germans surrendered after slight resistance or none. At one point, the Château at Montboint, a company of The

* Lt.-Col. M. J. Scott of the Governor General’s Foot Guards took over, evidently after some delay. When a wound forced Scott into hospital on 15 August, Lt.-Col. W. W. Halpenny of the Canadian Grenadier Guards succeeded him. Brigadier R. W. Moncel took command of the brigade on 19 August. General Kitching states that he asked for Moncel (who had been previously earmarked as a replacement in case of the brigade commander becoming a casualty) as soon as Booth’s death was reported.

Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders—who arrived in the valley before our tanks—were held up by machine-gun posts; these were rapidly dealt with, with the aid of a new and terrible weapon here first used by Canadians, the WASP—a flame-thrower mounted on a carrier. A Tiger tank (apparently one of two which were causing trouble hereabouts) was knocked out by an SD and G. 6-pounder detachment.42

The Laison valley, deep-cut and wooded, is a rather striking feature; but the “river” itself is little more than a ditch, six feet or so wide and a couple of feet deep.43 Nevertheless, it proved itself a more considerable tank obstacle than had been expected. The provision made for crossings was “fascines”, great bundles of brushwood carried by engineer assault vehicles. These were effective when once in place, but it was some time before the AVREs could reach the crossing-places, and meanwhile there was congestion and confusion along the little stream. Some tanks bogged down in attempting to ford it; other groups managed to improvise crossings from rubble and the remains of destroyed bridges. On the 3rd Division front on the right most of the tanks of two squadrons of the 1st Hussars suffered the former fate; the reserve squadron discovered a crossing at Rouvres, found itself leading the regiment’s advance and pushed on to occupy the high ground west of Olendon.44 The light vehicles of the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) seem to have been first across the river, and this unit’s squadrons advanced toward the high ground with a view to occupying it pending the arrival of heavier armour.45

On the 4th Division front, some tanks, seeking a crossing, got as far east as Ernes, where they found a practicable one; others waited until crossings were completed at Rouvres and Maizières.46 According to the Canadian Grenadier Guards’ diarist, “the whole brigade was split up into small groups, each group containing representatives of all the units”. Late in the afternoon the armoured advance on this front was proceeding beyond the Laison. Shortly before midnight the armoured regiments of the 4th Armoured Brigade were disposed about Olendon (which the 10th Infantry Brigade had captured in the evening) with the 21st Armoured Regiment,, the farthest forward, immediately south of the village. The main body of the 10th Brigade was in the same area, and The Algonquin Regiment was about to carry the advance on towards Epancy.47 In the 3rd Division’s sector, the 2nd Armoured Brigade were on the north end of the high ridge between the Laison and Olendon, and the 7th Infantry Brigade were reinforcing them. The 8th Brigade, having cleared its portion of the valley, was now back under the 3rd Division, and the North Shore Regiment had occupied Sassy.48

The assault had been a complete success; the 4th Division reported that by 11:00 p.m. it had captured prisoners numbering 15 officers and 545 other ranks. But it also reported that progress south of the river was slow.49 It seems evident that this was due not so much to enemy opposition as to the degree of disorganization, all across the front of attack, which resulted from the losses of direction during the advance to the Laison and the confusion in the valley while our units sought for crossings.

Sketch 18: Operation TRACTABLE, 14–16 August 1944

In the early morning of the 14th the 2nd Canadian Division, on the right of the Corps front, had attacked successfully to enlarge its Clair Tizon bridgehead. During the afternoon it beat off three counter-attacks delivered at La Cressonniere* by troops identified as belonging to the 12th SS Panzer Division.50 The Polish Armoured Division, now operating on this same flank west of the Falaise Road and having no major role in the day’s offensive except to exploit the Bomber Command attack,51 got patrols into Bray-en-Cinglais, north of Clair Tizon, but does not seem to have held the place.

The day’s success had been marred by another incident, strikingly similar to that of 8 August, in which our troops were bombed by our own supporting aircraft. On the 8th the errant bombers had belonged to the US Eighth Air Force. This time they were aircraft of the RAF Bomber Command; and of the 77 planes that bombed short 44, by ill hap, belonged to No. 6 (RCAF) Bomber Group.52

As we have seen, beginning at 2:00 p.m. Bomber Command was to strike at six targets in the area Quesnay-Fontaine-le-Pin-Bons-Tassilly. The damage done the enemy may have been somewhat reduced by the warning given by the captured document above referred to. All told, 417 Lancasters, 352 Halifaxes and 42 Mosquitoes of Bomber Command took part and 3723 tons of bombs were dropped. Two aircraft were lost, one of them, it appears, unfortunately by our own anti-aircraft fire.53

The short bombing was chiefly in the area of St. Aignan and about the great quarry at Hautmesnil on the Falaise Road.54 One senior RAF officer experienced its effects, for Air Marshal Coningham was in General Simonds’ armoured car near Hautmesnil at the time.55 Though it is impossible to state precisely how many casualties it caused, it seems that the loss was somewhat heavier than that in the earlier incident (above, page 223). A return prepared at Headquarters First Canadian Army on 15 August showed totals of 65 killed, 241 wounded and 91 then missing. Many of the missing were certainly killed. Canadian artillery regiments east of Hautmesnil suffered heavily, the 12th Field Regiment RCA having (as finally established) 21 killed or died of wounds and 46 wounded. The Royal Regiment of Canada was badly hit, its casualties this day being six killed and 34 wounded. The Poles again had serious losses, reporting 42 killed and 51 missing as of 15 August.56

The incident was fully investigated on the orders of Air Chief Marshal Harris. The technical reasons which led to it need not be explored here, but Bomber Command considered that a blameworthy aspect was the failure of the bomber crews to carry out orders which required them to make carefully timed runs from the moment of crossing the coast. This precaution would have prevented the errors. Disciplinary action was taken against individuals whose responsibility could be established. Two Pathfinder Force crews were re-posted to ordinary

* The credit goes chiefly to The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, even though their war diary does not mention these attacks and dates the bombing attack accompanying TRACTABLE as 15 August.

crew duties, squadron and flight commanders personally involved relinquished their commands and acting ranks and were re-posted to ordinary crew duty, and all crews implicated were “starred” so as not to be employed upon duties within 30 miles forward of the bomb line until reassessed after further experience.57

One particularly unfortunate aspect of the bombing was not the fault of the aircrews. Under orders issued by SHAEF,58 one of the recognition signals to be used by Allied troops for identification by our own air forces was yellow smoke or flares. This was duly shown by our troops on 14 August. Unhappily, neither SHAEF nor Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Air Force had advised the RAF Bomber Command of this procedure.* Even worse, the target indicators used by Bomber Command on 14 August were of a yellow colour similar to the army recognition signals. Thus the yellow smoke burned by the units under attack had the reverse effect to that for which it was intended, merely attracting more bombs.59 The Royal Regiment recorded that it was out of yellow smoke, took steps to get a supply when bombing began nearby, displayed it, and was immediately bombed.

Sir Arthur Harris complained, as well he might, of the failure to inform his Command in this matter. He asserted indeed that his Senior Air Staff Officer, who had arranged the operation with First Canadian Army, “had particularly sought information on the subject of possibly confusing pyrotechnics and been assured that none would be used”.60 It seems evident that it simply never occurred to General Crerar’s staff that Bomber Command would not be fully conversant with a procedure laid down by SHAEF long before D Day and used universally throughout the campaign so far; and, most unfortunately, nobody thought of mentioning yellow smoke in the discussions with Harris’s representative. It was certainly not the responsibility of an army headquarters to inform Bomber Command of such a matter, and it was undoubtedly assumed that higher authority had done it long before.

During the time when our troops were being bombed an attempt was made by the pilots of small Auster aircraft of Air Observation Post squadrons to warn the bombers off by going aloft and firing red Verey lights. Observers at Headquarters 4th Division felt sure that one such aircraft “was responsible for preventing the bombers from dropping more bombs on our own troops”,61 and there are other similar reports. Air Chief Marshal Harris, however, commented that this procedure was “likely to and did in fact, give a misleading imitation of target indicators”. With the best intentions, he said, these Austers “succeeded only in making confusion worse confounded”.62

There are many reports to indicate that this incident, following the similar one six days earlier, had momentarily a severely depressing effect on the morale of the units and formations that suffered.63 Men naturally overlooked the fact that the vast majority of the bombs had gone down precisely where they were intended to. In his final communication to Harris about the affair, General Crerar expressed the opinion that the Bomber Command attack “contributed greatly to the great

* This may have been the result of the strategic bomber forces coming under SHAEF at such a relatively late date (above, page 23).

success” of the day’s operation, and said that he remained a very strong advocate of the use of heavy bombers in closely integrated support of the army when the latter was faced by strong defences. The letter ended with “sincere thanks for your co-operation in the past, and... great confidence in such mutual efforts as may be ours in the future”.64

The Drive Continues Towards Falaise

During 14 August General Montgomery again somewhat modified his instructions to General Crerar, who was now instructed that he, and not General Dempsey, was to take Falaise. This was to be done with the least possible delay, but was not to interfere with the larger and more important task of driving south-east to capture Trun and link up with General Patton’s forces coming up from the south.65 The Americans were now just south of Argentan, only some 15 miles south-east of Falaise. At this point their advance had been stayed, though not by the enemy. This incident requires some analysis.

The “boundary” between the 12th and the 21st Army Groups ran approximately eight miles south of Argentan. It had been established by a message from Headquarters 21st Army Group sent at 11:00 p.m. on 5 August,66 well before the German counter-offensive was launched. On the evening of 12 August troops of the 15th US Corps of General Patton’s Third Army reached this boundary and in fact crossed it, coming within four kilometres of Argentan. Uncertain whether or not to push on farther with a view to closing the gap through which the Germans were now retiring, Major-General Wade H. Haislip, commanding the 15th Corps, told his divisions not to advance beyond Argentan and sought guidance from Patton. Shortly after midnight of the 12th-13th Patton ordered him to capture Argentan, “push on slowly in the direction of Falaise” and on reaching it “continue to push on slowly until you contact our Allies”. Early in the afternoon of the 13th, however, Patton countermanded this very sensible order and instructed Haislip to halt in the vicinity of Argentan and assemble his units in preparation for further operations.67 (According to the version that reached First Canadian Army, the phrase was operations “north, north-east or east”.)68

It has been stated69 that General Montgomery originated the countermanding order, but this was not the case. The responsibility for the decision not to cross the boundary rests with General Bradley, who has fully and frankly accepted it. The matter was never referred to Montgomery. Bradley has explained that he doubted Patton’s ability to block the Gap, through which the great German force was “now stampeding to escape the trap”. (The main movement however had not actually begun at this time.) But he also feared the consequence of “a head-on meeting between two converging Armies” with, perhaps, “a disastrous error in recognition”.70 Although Montgomery was not consulted, the Supreme Commander was. General Eisenhower himself has written, “I was in Bradley’s headquarters when messages began to arrive from commanders of the advancing American columns, complaining that the limits placed upon them by their orders were allowing Germans to escape. I completely supported Bradley in his decision

that it was necessary to obey orders, prescribing the boundary between the army groups, exactly as written; otherwise a calamitous battle between friends could have resulted.”71 As a result of this, the formations of the 15th US Corps remained relatively quiescent from the 13th through the 16th of August, holding road-blocks south and south-east of Argentan.72

General Patton raged against this decision at the time. We need not lose our tempers over his reported “crack” to Bradley, “Let me go on to Falaise and we’ll drive the British back into the sea for another Dunkirk.”73 Patton no doubt had his failings, but he had the instincts of a great battlefield commander, and he knew an opportunity when he saw one. The situation south of Falaise on 13 August presented one of the greatest opportunities of the war. First Canadian Army failed to take full advantage of it on its side of the Gap; Bradley and Eisenhower refused to take full advantage of it on theirs. It is true that Patton might not have succeeded in closing the Gap; but the stakes were so high that it was well worth trying. It is true that an advance beyond the boundary might have resulted in fatal incidents between two Allied armies; but these would have been much more than compensated for by the damage which closing the Gap would have done the enemy. Ultimately the boundary had to be disregarded (below, page 251). It would have been good sense to disregard it on 13 August.

General Patton, in his posthumous book, said that the order forbidding him to advance was attributed to the fact that “the British had sown the area with a large number of time bombs”.74 Delayed-action bombs had in fact been dropped on the Argentan-Falaise road about 8:00 p.m. on 12 August, the maximum delay being 12 hours. These bombs were dropped by the US Ninth Air Force, as were others put down on the 13th with a six-hour delay. None of them would have interfered with a northward drive by Patton’s army.75

Turning to the German side, we find that by 9 August the Commander-in-Chief West had completely accepted the fact that the offensive at Mortain had failed: “Further successes are no longer to be expected from this attack group.”76 Hitler, however, disagreed. The attack, he said, had been launched prematurely; it was now to be resumed in the area of Domfront. General Eberbach was placed in charge of it; Sepp Dietrich was to command Fifth Panzer Army* in his absence.77

On 11 August Field-Marshal von Kluge reported that his army commanders concurred in his view that the Domfront attack was no longer practicable. The situation was deteriorating from hour to hour; the only immediate action possible was an attack on Patton’s army in the Alençon area. Hitler at once agreed that the 15th US Corps thereabouts was to be “destroyed by concentric attack”. In the meantime, however, strong resistance was to continue at Falaise and Mortain, and the intention of “carrying out attack towards the West” was to be maintained.78 The German armoured formations which had lain about Mortain since 7 August now begun to move eastward. On 13 August von Kluge made a pessimistic report which resulted in Hitler reiterating his orders for the attack on the 15th Corps.79

* On 27 July Panzer Group West had been given army status, and thereafter usually called itself “Panzer Army West”. On 8 August it was officially redesignated Fifth Panzer Army.

Such an offensive, however, was now out of the question, and on the night of the 14th-15th von Kluge reported that the Führer’s project simply could not be carried out. The only remaining possibility, it seemed, was to seek to break out of the narrowing pocket towards the north-east.80

On the Fifth Panzer Army front north of Falaise these days had seen desperate attempts to collect reinforcements to buttress the crumbling line. The German strength, small in the beginning, was steadily sapped by casualties. These were particularly heavy on 8 August. That evening Eberbach, reporting to von Kluge by telephone,81 spoke of the “renewed Allied bombings” (those of the afternoon), which “crushed the 12th SS Panzer Division so that only individual tanks came back”. Eberbach went on:

1 SS Pz Corps has built up a battle line with anti-tank and flak guns [see above, page 224], which has held so far. Whether this line will hold out until tomorrow if the enemy attacks more energetically is questionable. Actually the new Infantry Division [the 89th] are 50% knocked out. I shall be lucky if by tonight I am able to round up 20 tanks, including Tigers.

The same evening Fifth Panzer Army ordered the 2nd SS Panzer Corps (on the Army’s left flank north of Flers) to send to the 1st SS Panzer Corps any Mark IV and Mark V tanks still remaining with the 9th SS Panzer Division. Soon it was reported that a number of tanks, and in addition the anti-aircraft battalion and anti-tank battalion of the 85th Division, which had been under the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, were on the way. Later, however, word came that these tanks had been “built into the main line of resistance” and therefore in place of them the 2nd SS Panzer Corps was sending its Tiger battalion, present strength 13 tanks.82 This unit arrived on the 9th. But the Panther battalion of the 9th Panzer Division, which had also been promised, was sent instead to the Seventh Army.83 On the evening of 9 August, Fifth Panzer Army reported that the tank strength of the 1st Panzer Corps—presumably including the newly arrived Tigers—was down to 35 (15 Mark IVs, five Panthers and 15 Tigers).* By tomorrow, it said, it would be impossible to prevent a break-through to Falaise.84

The Canadian blow down the Falaise Road alarmed the Commander-in-Chief West so much on 8 August that it considerably affected his view of the situation at Mortain and contributed to leading him to defer ordering further action there (though it must be said that he probably considered such action hopeless anyway). At 6:45 p.m. he said to the commander of the Seventh Army,85

... there is an enemy penetration at Caen such as there has never been before. I come to the following conclusion: We must make preparations tomorrow for the reorganization of the attack. There will be no continuation of the attack tomorrow, but we will prepare to attack on the day following.

But by 3:20 p.m. on the 9th, when the Canadian thrust had been blunted by the disaster to the British Columbia Regiment near Estrées (above, pages 226-8), von Kluge was more confident. After a conversation with the Supreme Command he

* The 4th Canadian Armoured Division alone still had a tank strength of 234 on the evening of 10 August. The strength of the 2nd Canadian Corps as a whole for this date cannot be found, but it must have been in the vicinity of 700 tanks.

told the Seventh Army’s Chief of Staff,86 “I have proposed that we hold to the plan for attack, inasmuch as the situation south of Caen is restabilized and has not had the effect feared. The attack must now be prepared and carried out according to plan, not rashly and hastily.”

The units of the 85th Infantry Division continued to arrive in the 1st SS Panzer Corps area, and on 11 August this division took over the 12th SS Panzer Division’s front, and part of the 89th Division’s. It now held the right sector of the Corps front, along the Laison valley from Ernes to just east of the Falaise Road. Its main line of resistance was on the high ground immediately north of the Laison.87 The much-reduced 89th Division continued to hold the centre sector, and the left portion of the Corps front was still confided to the 271st Infantry Division. The 12th SS, it would seem, was no longer responsible for a specific sector, but was in reserve in rear ready to act at any threatened point. Part of it remained in the 89th Division’s sector.88 There is evidence that it was now acting also as “battle police” to hold the Wehrmacht infantry divisions in line.89 There had been a slight increase in its tank strength, which on 10 August was up to 18 Mark IVs, nine Panthers, 17 Tigers and some others.90

In these circumstances, it was the 85th Infantry Division, supported and “encouraged” by the 12th SS, that took the main brunt of our attack in Operation TRACTABLE. Some 1010 prisoners were taken from this division in the first phase of the operation.*91 However, an important part of its infantry strength, the 85th Division Fusilier Battalion, had been stationed south of the Laison (though apparently with outposts north of it) on its right; and the divisional artillery had been sited south of the river “so as to destroy any tank attacks over the high ground north-west of the Laison sector by massed artillery fire over open sights”.92 These elements, at least, therefore, may not have been wholly overrun in the first rush; although the Fusilier Battalion lost as many as 171 prisoners, and the divisional artillery regiment 120, on 14 August.93 The division had some fight left in it; and the remnant of the 12th SS was still showing determination—though by 15 August it was down to 15 tanks.94 But it was the 88-mm. guns that were to give us most trouble in the next phase.

On the morning of the 15th our advance towards Falaise was resumed. The enemy had strong ground to aid him in delaying it, the dominant feature being the long ridge running directly north from Falaise just east of the main road. The 4th Armoured Brigade pushed west of Epancy, leaving The Lake Superior Regiment and a squadron of the Foot Guards to capture the village itself, in cooperation with The Algonquin Regiment which was to assault from the north. Epancy was fiercely defended; the Algonquins had a long hard fight before the place was finally made good.95 The 4th Armoured Brigade’s day, as reflected in the records, was marked by confusion and lack of coordination. Late in the afternoon two armoured regiments, the Canadian Grenadier Guards and the British

* This is the number reported as having been received at the Corps cage and passed through the Army cage between 6:00 p.m. on 14 August and the same hour the following day. The grand total of prisoners on the Army front for this period was 1299.

Columbia Regiment (the latter now composed mainly of reinforcement tanks and crews) reached, or were reported to have reached, Point 159, the southern butt of the ridge, immediately above Versainville; but here they ran into heavy anti-tank fire and were driven back.96 The 4th Division diarist observed, “... it appeared that the enemy had once again established an anti-tank screen on the southern slopes of the high ground which the Armoured Brigade was unable to penetrate”.97 The brigade, it will be remembered, was still under interim command.

On the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division front to the west, there was fierce fighting in the afternoon. On the ridge immediately east of the Falaise Road the 1st Battalion Canadian Scottish Regiment, fighting under command of the 2nd Armoured Brigade, and supported by the 1st Hussars, met and beat down tenacious opposition on Point 168. The Hussars, as the result of an inopportune enemy counter-attack, had to go in with their ammunition “unreplenished and very low”,98 and they encountered nasty anti-tank fire. Unfortunately also the range in the beginning is reported to have been too long for artillery support, and when the field guns did come into action some shells dropped among our own troops. It was a grim affair. The Scottish went into the attack “tired, hungry and thirsty”. Few prisoners were taken, the enemy, partly at least reported to be SS men, “preferring to die rather than give in”.99 The Germans seem to have had most of their surviving tanks in this area. “The infantry pushed forward to their objective, however, and the tanks were able to support them onto it but the heavy anti-tank fire made it impossible for the tanks to get onto the objective themselves.”100 CSM J. S. Grimmond won the DCM by leading his company headquarters party against two enemy tanks and a group of infantry and routing them. This was one of those fights where the job had to be done mainly by the men on foot, and as was too usual they paid a heavy price. The battalion’s casualties, the heaviest it had yet suffered on a single day, were 37 killed or died of wounds and 93 wounded.101 But late afternoon found the companies fully dug in on the objective, and all counter-attacks were repelled.102 The enemy, however, had not entirely withdrawn from the area; in an evening attack on the village of Soulangy below the ridge the 2nd Armoured Brigade lost 10 tanks, and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, after getting into the village, were forced out of it.103

During the morning the Polish Armoured Division had cleared the area about Potigny; it then handed it over to the 2nd Canadian Division and began to move eastward towards the River Dives. The 2nd Division itself found that, after his unsuccessful counter-attacks on the 14th, the enemy had retired on its front. The 4th Infantry Brigade, moving on Falaise from the west with the Essex Scottish leading, met no opposition and by nightfall was only a mile or so from the edge of the town.104

In accordance with General Montgomery’s intentions (above, page 245), General Crerar on 15 August instructed General Simonds that as soon as Falaise had been taken and handed over to a Canadian infantry division, he would direct his two armoured divisions on Trun. The following day Simonds issued orders that the 2nd Division would clear Falaise and reorganize, while the two armoured divisions would be directed eastward on Trun.105 The 4th Armoured Division,

which had been planning another attack on the high ground north of Falaise, was told on the morning of the 16th to move instead to seize a crossing over the Ante River in the Damblainville area and advance along the axis of the main highway running south-east to Trun to close the gap between the First Canadian and Third United States Armies.106 In the meantime, the Poles, advancing farther north, were to cross the Dives at Jort (which they had reached on the 15th) and also move south-east, on a line parallel to the 4th Division’s.107 At 3:30 p.m. Montgomery spoke to Crerar and told him that a German force containing elements of five panzer divisions was reported to be counter-attacking the American salient stretching north to Argentan. The Commander-in-Chief appreciated that when the enemy discovered that his escape route was blocked by the American line between Argentan and Carrouges, he would try to force his way out through the gap remaining between Argentan and Falaise. The capture of Trun, in the middle of the gap, was thus vital. This requirement had been anticipated in essentials by General Simonds’ earlier orders, but he now ordered the 4th Division to accelerate its move.108 By midnight its leading troops were on the high ground immediately north of Damblainville. Meanwhile the 3rd Division had pushed south from Point 168 and the 7th Brigade occupied the high ground about Point 159.109

The task of taking the tragic ruins*110|111 of Falaise thus fell to the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. Brigadier Young was ordered to clear the town with the 6th Brigade, and attacked at 3:00 p.m. with The South Saskatchewan Regiment on the left and The Cameron Highlanders of Canada on the right, each supported by a squadron of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment. The advance was handicapped by the huge craters caused by our bombing. Moreover, parties of the enemy were still fighting hard in the ruins. By the morning of 17 August, however, the South Saskatchewan had reached the railway east of the town. The Camerons had not got forward so rapidly, their tanks being hung up in craters; but they finished their task that day and then moved south across the River Train.112

The job of mopping up the last resistance in Falaise, one which was far from easy, was left to Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal. Fifty or sixty desperate men of the Hitler Youth Division had established themselves in the Ecole Supérieure in the centre of the town. The building, surrounded by a heavy wall, commanded the southerly main east-west road through Falaise. Resistance here finally ended only about 2:00 a.m. on 18 August, when the Fusiliers assaulted in the midst of an enemy air attack which took toll of friend and foe alike. The building was fired. Four of the Germans were reported to have escaped. The others “fought to the end”; none surrendered.113

The destruction in Falaise had been appalling. In some parts of the town it was difficult even to tell where the streets had run, and our bulldozers had much difficulty in opening routes. The castle where William the Conqueror was born, on the high rock or falaise that gives the place its name, was little damaged, save

* On the night of 12-13 August 144 aircraft of the RAF Bomber Command attacked Falaise with a view to blocking the enemy’s escape route through the town, which had also been subjected to harassing fire from our medium artillery.

for the, marks of a few shots fired at it in the process of clearing out snipers; the Conqueror’s statue in the square below was untouched; but as a whole the ancient town that had been our objective for so long was little more than a shambles.

The capture of Falaise had deprived the Germans of their best remaining east-west road, but they still had at their disposal the one running north-east from Argentan to Trun, and various secondary routes. The action that might suitably have been taken on 13 August when Patton was prevented from crossing the army boundary south of Argentan, was taken now. Having ordered General Crerar to drive towards Trun on his side of the gap, General Montgomery directed General Bradley to push on from Argentan towards Trun and Chambois. The intention seems to have been simply to disregard the army group boundary, for there is no record of a change in it at this moment.*

Action on the American side of the Gap was delayed by regroupings and misunderstandings concerning command. When General Patton was forbidden to cross the boundary at Argentan he had, in effect, lost interest in that area and had asked to be allowed to send two of the divisions there eastward towards the Seine. Without reference to Montgomery, Bradley authorized this; and Patton’s spearheads were soon driving east, meeting little opposition. On 18–19 August the leading troops of the 15th Corps reached the Seine in the vicinity of Mantes-Gassicourt.114

There were now three Allied divisions in the Argentan area (the 2nd French Armoured and the 80th and 90th US Infantry Divisions). Headquarters 15th US Corps having moved east towards the Seine, Bradley and Patton acted separately to provide local coordination for the attack towards Trun. Patton created a Provisional Corps under his chief of staff, Major-General Hugh J. Gaffey, to direct the advance. Gaffey arrived at Alençon on 16 August and that night issued an order for the 2nd French Armoured Division (left) and 90th Division (right) to attack next day and capture Trun and Chambois.115 But before the attack could get under way a further regrouping was carried out on Bradley’s orders. The Argentan front was transferred to the First US Army, and Major-General L. T. Gerow with the headquarters of his 5th Corps (which had been “pinched out” farther west) arrived to take command of the divisions there. He made contact with Gaffey; the latter put off his attack; and both generals asked higher authority for a decision on who was in command in the area. Bradley having decided in favour of Gerow and the First Army, on the afternoon of 17 August Gaffey turned his divisions over to Gerow and disbanded the Provisional Corps. Gerow postponed the attack until 18 August, since his corps artillery was still moving up and he did not like Gaffey’s plan. Gerow’s own plan was to hold on the left with the

* The precise time at which Montgomery issued this instruction to Bradley cannot be determined from the records available. General Bradley’s account (A Soldier’s Story, 378-9) might if taken literally indicate that the date was 14 August, but this is clearly impossible. The US Army’s official history (Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit) “infers” that the order was issued on 16 August, and this seems highly probable. It seems likely, in fact, that Montgomery telephoned Bradley about the same time at which he telephoned Crerar (above, page 250). This is rendered the more probable by the statement of General Patton (War As I Knew It, 109-10) that it was at 6:30 p.m. on the 16th that Bradley telephoned him and ordered him to attack towards Trun. Pogue, The Supreme Command, p. 214, states that Montgomery had in fact authorized on the 15th an attack across the boundary farther west to enable the First Army to take Putanges.

French division (less one combat command) between Ecouché and Argentan, while the 80th cut off Argentan with an attack east of it, and the 90th, with a French combat command to help it, drove forward from the line Le Bourg St. Léonard–Exmes towards Chambois. The 90th Division had already been in heavy action with the Germans at Le Bourg St. Léonard, north-east of Argentan; on the night of the 17th–18th it attacked again and secured the village as a line of departure for the main effort.116 H Hour for the main attack, as prescribed in Gerow’s field order,117 was 6:30 a.m. on the 18th, at least a day and a half after Montgomery’s order to attack towards Trun and four and a half days after Patton had been stopped at the boundary. During this period the Canadians had been fighting down from the north with painful slowness, and the Germans had been flooding out through the Gap in increasing numbers.

The 4th Canadian Armoured Division continued to encounter difficulties on 17 August. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders captured Damblainville with little trouble early in the morning, but The Algonquin Regiment could not secure the high ground south of the village which commanded the crossings of the Ante. From this ground the enemy brought down intense mortar and machine-gun fire, and when the armour began moving through to cross a bottleneck developed.118 The old stone bridges in the village, and their approaches, were intact, but they were narrow and overgrown with scrub, grossly inadequate means for such a movement.119 This, combined with the opposition the enemy was offering, led to an order from the Corps Commander to switch the 4th Division’s effort to the left and cross the Dives at Couliboeuf (below its confluence with the Ante and the Traine), where two platoons of The Algonquin Regiment had gained a bridgehead on the 16th.120 The 3rd Division was to take over the Damblainville area. The change of plan required a tremendous effort of traffic control, but was carried out successfully. During the afternoon the 4th Division’s armour crossed the Dives at Couliboeuf and Morteaux-Couliboeuf, followed by the 10th Infantry Brigade.121 Being now farther to the north than had been planned, and far off the line of the main Falaise-Trun highway, it had to advance towards Trun, so to speak, by the back door. Once across the river, good progress was made, and by evening the Canadian Grenadier Guards, meeting only light resistance, had reached Louvieres-en-Auge, a couple of miles north of Trun. Here they harboured, preparatory to attacking Trun in cooperation with the Lake Superior Regiment.122 In the meantime the Polish Armoured Division, thrusting for Chambois, had got its leading troops into Neauphe-sur-Dives, directly east of Trun.123

The final tactical arrangements for closing the narrowing Gap had been telephoned to the Chief of Staff of First Canadian Army by General Montgomery at 2:45 p.m. on 17 August. Brigadier Mann recorded the order as follows:124

It is absolutely essential that both the Armd Divs of 2 Cdn Corps, i.e. 4 Cdn Armd Div and 1 Pol Armd Div, close the gap between First Cdn Army and Third US Army. 1 Pol Armd Div must thrust on past Trun to Chambois 4051 at all costs, and as quickly as is possible.

During the next two days these orders were carried out in the face of frenzied German opposition which slowed progress both north and south of the Gap.

The Germans’ situation had become steadily worse from the moment when

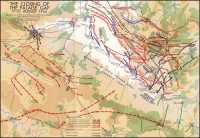

Sketch 19: Expansion of the Normandy Bridgehead, July–August 1944

von Kluge first recommended withdrawal from the pocket. During 15 August von Kluge himself temporarily “went missing”. He had set out, it seems, to visit his subordinate headquarters, but his car was shot up by Allied aircraft, his wireless transmitters destroyed and his party held up for hours in traffic jams. Hitler suspected—apparently quite baselessly—that the field marshal was negotiating with the Allies. In the course of the night of 15-16 August von Kluge finally reached General Eberbach’s command post.125

Von Kluge was now on the verge of dismissal and, indeed, death. But before he left the scene he was able to give the vital order to retreat from the salient west of the Gap. Until now he and his subordinates had continued to urge such action without success. “It is five minutes to twelve”, Blumentritt, his chief of staff, told OKW on 15 August.126 And at midday on the 16th von Kluge himself spoke to Jodl. Hitler had issued yet another counter-attack order the evening before. This, von Kluge said, was impossible to execute. “To cling to a hope that cannot be fulfilled by any power in the world ... is a disastrous error. That is the situation!”127 Later that day a Führer order arrived authorizing withdrawal behind the Orne and then the Dives—though Falaise (which the Germans were finally losing at that moment) was to be held as a corner post.128 Von Kluge proceeded—still on 16 August—to issue orders129 for the retirement; it is possible that he acted before the Führer’s permission arrived, for the time of its receipt is not recorded, and the field marshal quite probably now considered himself a dead man. On the other hand, he may have. relied on the fact that during their conversation Jodl had promised him “a degree of freedom of action” (eine gewisse Handlungsfreiheit). The movement was to begin that night. Fifth Panzer Army and Seventh Army were to “withdraw without delay to the sector of the Dives and the line Morteaux-Trun-Gacé-Laigle”. Hausser, the commander of the Seventh Army, was to direct the whole movement. Panzer Group Eberbach was to cover the withdrawal in the area Argentan–Gacé and thereafter be disbanded, Eberbach resuming command of the Fifth Panzer Army.130

Issuing these orders was von Kluge’s last significant act of command. On 1 July Field-Marshal von Rundstedt had suggested evacuating the Caen bridgehead, and two days later von Kluge had arrived at his headquarters as his successor. History now repeated itself. Von Kluge having recommended the abandonment of the Eberbach Group’s attack and withdrawal from the pocket, in the evening of 17 August Field-Marshal Walter Model appeared at Headquarters Army Group B, presented a letter from Hitler and relieved von Kluge.131

The next day the fallen Commander-in-Chief left his former headquarters for Germany. En route he committed suicide, apparently by taking poison. According to General Jodl’s diary notes, he was dead when his aircraft reached Metz. But he had left behind him a letter to Hitler, dated 18 August,132 in which he told the Führer a number of things. One was that his order for the offensive directed on Avranches was in practice impossible to carry out; “on the contrary”, he wrote, “the attacks ordered were bound to make the all-round position of the Army Group decisively worse, And that is what happened.” Von Kluge recalled his earlier letter covering

Rommel’s memorandum (above, page 179). These two documents, he said, had been prepared on “sober knowledge of the facts”. The letter concluded:–

I do not know whether Field-Marshal Model, who has been proved in every sphere, will still master the situation. From my heart I hope so. Should it not be so, however, and your new, greatly desired weapons, especially of the Air Force not succeed, then, my Führer, make up your mind to end the war. The German people have borne such untold suffering that it is time to put an end to this frightfulness.

...my Führer, I have always admired your greatness, your conduct in the gigantic struggle and your iron will to maintain yourself and National Socialism. If fate is stronger than your will and your genius so is Providence. You have fought an honourable and great fight. History will prove that for you. Show yourself now also great enough to put an end to a hopeless struggle when necessary.

I depart from you, my Führer, as one who stood nearer to you than you perhaps realized, in the consciousness that I did my duty to the utmost.

This document is the best testimony to the desperate situation of the German armies in the West. Model, however, proceeded to do his best, and his troops continued to fight fiercely. At a conference on the morning of 18 August Model gave instructions that the Seventh Army and Panzer Group Eberbach were to be extricated as quickly as possible, while the 2nd SS Panzer Corps (with the 2nd, 9th and 12th SS Panzer Divisions and the 21st Panzer Division) held the north wall of the escape corridor, and the 47th Panzer Corps (with the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions) the south wall.133 The same day Hausser issued a clear and sensible written order134 along these lines. It emphasized the importance of our “deep penetration South-East of Morteaux–Couliboeuf into the area NorthWest of Trun”, and proceeded:

For the success of the whole withdrawal behind the Dives it is of decisive importance both to recover the area Morteaux-Couliboeuf, as a corner-stone for the new front, and to establish a covering line on the South at and East of Argentan.

The intention is while holding firmly these corner-stones to withdraw the formations lying South-West of the Dives behind the river in two to three nights.

The attack to Morteaux-Couliboeuf was to be carried out by the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, which had got out, or was then getting out, through the Gap and was concentrating at Vimoutiers. It was now to turn back into the cauldron. The establishment of the covering line on either side of Argentan was the business of Panzer Group Eberbach.

In the sector south-east of Falaise the Germans’ position had been going from bad to worse. As early as 14 August, von Kluge, realizing that the 1st SS Panzer Corps could not possibly hold out longer without reinforcements, had ordered the 21st Panzer Division disengaged from its commitments farther west and moved to the Falaise area.135 However, its commander did not reach the headquarters of the Fifth Panzer Army until the morning of the 16th. He was then ordered, on his own suggestion, to commit his division at Morteaux-Couliboeuf, which was already recognized as a point of danger.136 It shortly began to come into action; but it was too late to reach Morteaux. It was identified south of Falaise on 17 August, and west of Trun the following day.137

By the 18th the German retreat through the Gap had reached full flood. Two nights had brought the Seventh Army across the Orne comparatively unscathed

in the crossing. (Unfortunately, the Allied air forces were giving their main attention to targets farther east, including the crossings of the Risle and the Seine.)138 At 2:00 p.m. on the 18th the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief West recorded, “Withdrawals in pocket have been continuing. Bulk of forces [now] on east bank of Orne.”139

The Action of Chambois: The Closing of the Gap

The 2nd Canadian Corps “intention” for 18 August was simple: “To link up with US forces and hold line of River Dives.”140 But carrying it out was not so simple.

The two armoured divisions continued to push south-eastward to close the Gap. The Canadian Grenadier Guards’ intended attack on Trun was delayed by waiting for the company of the Lake Superior Regiment that was to cooperate. The enemy was apparently not attempting to hold the town, which was occupied by the 10th Infantry Brigade during the day; but he was on the hills east and south-west of it.141 The 4th Armoured Division’s morning situation report remarked, “Only slight resistance to forward movement our armour.”142 During the day the 4th Armoured Brigade pushed across the Trun-Vimoutiers road, and midnight found the Governor General’s Foot Guards a couple of miles north of Neauphe-sur-Dives.143 The direct drive from Trun towards Chambois was confided to the 29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) less one squadron, and with an infantry company of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada attached.144

The Polish Armoured Division fought its way into the rugged area south of Les Champeaux, some six miles north of Chambois, and reported in the evening that one squadron of its reconnaissance regiment had been “observing Chambois for some time” but “could not get in owing to bombing”145 (presumably our own). General Maczek wrote later that the commander of his 2nd Armoured Regiment, who had been ordered to make “an immediate stroke at Chambois” on the evening of the 17th, moved instead towards Les Champeaux, and not until 2:00 a.m. on the 18th.146 The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was moving up in rear through the Dives valley, and by the evening of 18 August the 7th Infantry Brigade, leading its advance, was in the area immediately northwest of Trun.147

With the Americans now beginning to push in from the south, the Gap had narrowed almost to nothing. The Germans continued to fight desperately to keep it open and escape. In the attempt they suffered terrific punishment at the hands of our tactical air forces.

The 17th of August, the day after von Kluge’s order to withdraw, was the first of what an account by No. 35 Wing RAF, the reconnaissance wing which served the Intelligence needs of the First Canadian Army, calls “three days of the largest scale movement, presenting such targets to Allied air power as had hitherto only been dreamed of”. Tactical reconnaissance aircraft reported during the day “a minimum of 2,200 vehicles of all types, including several concentrations so dense as to be uncountable”. Late in the afternoon the flood was moving eastward into

the area covered by No. 84 Group, supporting First Canadian Army.148 Under the stress of the emergency the Germans were attempting something they had not dared for many weeks: large-scale road movement in daylight. The weather was fairly good for flying, and our air forces made the most of it. During the twenty-four hours ending at 9:00 p.m. on 17 August the Allied Expeditionary Air Force flew 2029 sorties. The 2nd Tactical Air Force claimed for the day 13 tanks destroyed and 12 damaged, and 295 transport vehicles destroyed and 328 damaged.149 On this day a Canadian “Canloan” officer passed through the Gap at Trun as a prisoner. He shortly escaped, and the scene as he “and other escapers” saw it was thus described a couple of days later:150

All roads, and particularly the byways, were crowded with transport two abreast, grinding forward. Everywhere there were vehicle trains, tanks and vehicles towing what they could. And everywhere there was the menace of the air. They reported the RAF dominated the movement. On many vehicles an sir sentry rode on the mudguard. At the sound of a plane, every vehicle went into the side of the road and all personnel ran for their lives. The damage done was immense, and flaming transport and dead horses were left in the road while the occupants pressed on, afoot.

There were Red Cross signs everywhere—on staff cars, ammunition vehicles, in each convoy, even on ambulances. The bulk of the transport was of the “every man for himself” class. There were no complete ordered formations on the move. There was much horse drawn transport. ...

On the 18th the weather was still clear; and Allied pilots, after an initial absence of traffic, reported that by 10:30 a.m. “the Bank Holiday rush” was on again west of Trun. It was a day of supreme disaster for the fleeing enemy. The Allied Expeditionary Air Force made 3057 sorties. The 2nd Tactical Air Force claimed 124 tanks destroyed and 96 damaged, and 1159 transport vehicles destroyed and 1724 damaged.151 Such destruction had never fallen upon an enemy from the air.

In the circumstances of that moment, with thousands of aircraft aloft and the battle-lines on the ground in a very fluid state, it was probably inevitable that there should be some attacks on our troops by our own aeroplanes. In fact, reports of such attacks had been frequent for some days. The 51st (Highland) Division of the 1st British Corps made a particularly strong complaint on 19 August, specifying 40 individual incidents, resulting in 51 personnel casualties and 25 vehicle casualties, all of which had taken place the day before.152 The Polish Armoured Division however, had suffered still more heavily; having had large losses at the hands of our heavy bombers on both 8 and 14 August, it now had an unfortunate experience with the tactical air forces. On the evening of the 18th it reported, “Units and brigade headquarters have been continually bombed by own forces. Half the petrol being sent to 2nd Armoured Regiment was destroyed through bombing just after 1700 hrs [5:00 p.m.].”153 The Polish casualties from such attacks during the three days 16-18 August were computed as 72 killed and 191 wounded; those of the 2nd Canadian Corps as a whole totalled 77 killed and 209 wounded. Army Headquarters asked through Army Group for strong measures to prevent such incidents in future. It was able to report that of the many such attacks of recent days, only one had been traced to aircraft of its own supporting Group, No. 84. That Group, whose headquarters was located alongside the Army’s, had taken

special pains in briefing its pilots.154 On 18 August General Crerar sent a message to all Commanding Officers:155

It is necessary to stress the peculiar difficulties to the Allied air forces caused by the convergence of US, British and Canadian armies on a common objective, with air action against the enemy forces within that Allied circle most desirable up to the point of their surrender.

In order to judge the matter rationally and to avoid wrong or exaggerated conclusions as to what has been accomplished on behalf of the Army by the Tactical Air Force during their attacks today I give the scores, as yet incomplete and definitely conservative, compiled as at 2030 hours [8:30 p.m.]. Tanks flamers 77 smokers 42 damaged 55. Mechanical transport flamers 900 smokers 478 damaged 712.

If Canadian Army formations and units will compare their vehicle casualties proportionately to the above they will obtain some idea of the tremendous military balance in their favour.

As we have seen, US commanders had been strongly impressed by the danger of accidental collisions between the Allied armies as they advanced from either side of the Gap, and this had been a major factor in General Bradley’s decision to forbid Patton to cross the army group boundary. The same possibility was of course evident at Headquarters First Canadian Army, which saw the best means of avoiding such accidents in special liaison arrangements with the advancing Americans.

The first special measure in this respect had been taken on 12 August, when an artillery liaison officer was sent from Army Headquarters to the Third US Army. By 14 August information was being received from him by wireless,156 and a number of messages from him are preserved, addressed to the Commander Corps Royal Artillery, 2nd Canadian Corps, and repeated to the liaison section of the General Staff at Army Headquarters.157 Some of these were greatly delayed in transmission, but this mission certainly somewhat improved the Canadian Army’s knowledge of the American positions and plans.

On 16 August, with the armies drawing still closer together, General Crerar made an attempt at establishing more effective contact between their headquarters. He wrote a personal letter to General Patton informing him that he was sending a liaison officer to his headquarters to collect information on operations and pass it to First Canadian Army, and inviting him to send a liaison officer of his own to Crerar’s headquarters.158 The letter was sent by the liaison officer, Major A. M. Irvine, who set off that day by air. He never caught up with Patton, but after some difficulty reached Le Mans and found that Headquarters First US Army was taking over the sector and was nearby. He accordingly very properly presented General Crerar’s letter there.159 A message sent by him to First Canadian Army thereafter is on record:160

Direct liaison not permitted. Liaison on army group level only except corps artillery. Awaiting arrival signal equipment before returning.

On 20 August Major Irvine returned to First Canadian Army “from his abortive attempt to liaise with First US Army”.161

On 17 August Headquarters First Canadian Army began sending the Third US Army hourly situation reports to keep it informed of the precise whereabouts

of the Canadian forward troops. Several urgent requests were included for similar information about US troops. From the morning of the 18th, information having been received that the First US Army was taking over the Argentan sector, the hourly situation reports were directed to that army as well as the Third.162 It would seem that the artillery liaison officer had moved to the 5th Corps, for messages evidently sent by him continued to be received; some information about the US front also came through Headquarters 21st Army Group and its servant PHANTOM (the GHQ Liaison Regiment).163

While the Canadian Army drove south-east along the line of the Dives, the Second British Army was coming in below Falaise, pushing the Germans before it through the Gap. By the evening of 17 August the leading troops of the 53rd Division of the 12th Corps were directly south of Falaise; 24 hours later they were in the vicinity of Necy, some five miles south-east of Falaise, and pressing on.164 As for the First US Army, it was meeting heavy opposition in its advance northwards. The 80th Infantry Division’s attack immediately east of Argentan was stopped, and the 90th, though it made more progress, was held up short of Chambois by the 116th Panzer Division.165