Chapter 12: The Pursuit Across the Seine, 23–30 August 1944

(See Map 6, and Sketches 20, 21 and 22)

Advancing Towards the Seine

We have already described General Montgomery’s plan for the pursuit following the German defeat in the Falaise Gap (above, page 267). It was to get the Allied armies forward across the Seine with all speed, and in the process to effect if possible a second encirclement, pushing American spearheads in a great sweep up the left bank of the river to cut off the retreating enemy remnants before they could cross. The particular task of First Canadian Army was to cross the Seine, clear the Le Havre peninsula, and capture the port of Le Havre itself as soon as might be. By 23 August the Army was fully launched in this new direction.

On 19 August General Crerar had given his two Corps Commanders their orders for the advance.1 The 1st British Corps was to continue its movement along the axis Lisieux-Pont Audemer. The 2nd Canadian Corps was to follow the general line Trun–Vimoutiers–Orbec–Bernay–Elbeuf (or possibly Louviers). Its advance was to commence only when ordered by the Army Commander, but in the meantime General Simonds was to “carry out active reconnaissance in the direction indicated”. In fact, as has been seen (above, page 268), he started the 2nd Canadian Division off towards Vimoutiers on 21 August. The final paragraph of Crerar’s directive ran as follows:–

The basic tactical policy of the First Cdn Army, as previously explained, will be to advance to the R. Seine with “right leading” even though it may well be that 2 Cdn Corps will be temporarily prevented from commencing its part in this intended manoeuvre by its present commitments. ... In the meantime, 1 Brit Corps will not hold back on that account, but will proceed as indicated. ... Enemy garrisons in the coastal belt will be masked and contained by adequate forces. Their continued existence, however, will not be allowed to distract the main forces of 1 Brit Corps from their thrust along the axis given.

The 1st British Corps, as already noted, had some heavy fighting during its advance, particularly on the line of the River Touques. By 24 August, however, the Corps was across the Touques and advancing on Honfleur, on the south shore of the Seine Estuary opposite Le Havre. The 2nd Canadian Corps had reached the line of the River Risle east of Bernay, which was captured that day.2 Under orders issued by General Simonds on 22 August,3 the 2nd Canadian Infantry

Division was moving on the left, through Brionne, directed on Bourgtheroulde. The 3rd Division was in the centre, moving by way of Orbec upon the Elbeuf area. On the right the 4th Canadian Armoured Division was following the axis Broglie–Bernay–Le Neubourg, directed on the region about Pont de l’Arche. The advance was being led and covered by the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) and the divisions’ reconnaissance regiments.4

Resistance to the 2nd Corps had so far been insignificant; the enemy was chiefly intent on getting away, and such opposition as he offered was merely delaying actions by rearguards which withdrew as soon as strong pressure was applied. Indeed, the most memorable feature of these days was the tumultuous and heartfelt welcome which the liberated people gave our columns. The historian of the 10th Brigade wrote later, “Will Bernay ever be forgotten? Bernay where the people stood from morning till night, at times in the pouring rain, and at times in the August sun. Bernay where they never tired of waving, of throwing flowers or fruit, of giving their best wines and spirits to some halted column. ...”5 But in every town and hamlet the reception was much the same. It was an experience to move the toughest soldier.

It will be remembered (above, page 39) that before D Day the First Canadian Army had been directed to study the problem of an assault crossing of the lower Seine. As it turned out, no such operation was required. As early as 21 August, Army Headquarters informed General Simonds that “the AXEHEAD operation as planned in England, in regard to the crossing of R. Seine is definitely off”, adding that “an assault crossing in the Elbeuf bend seems indicated, if required at all, which seems to be somewhat unlikely”.6 On 25 August General Crerar issued a new directive.7

The Army Commander noted that the Second British Army was proceeding to take over the areas lately secured by American troops and those of First Canadian Army within the Second Army boundary. Thereafter, the 30th British Corps, on the British Army’s right, was to exploit the bridgehead obtained by the Americans in the vicinity of Mantes-Gassicourt, while on the left the 12th British Corps was to take over and, after the elimination of an enemy pocket existing between the British and Canadian Armies, develop a bridgehead east of the Seine in the vicinity of Louviers. The 8th British Corps was to be held, for the moment, in Second Army reserve; it was in fact “grounded”, its transport being used to get the rest of the Army forward.8 This symbolizes the greatest Allied problem in the phase now beginning-that of getting sufficient supplies to the forward troops to maintain the advance. The Allies were outrunning their maintenance; they had no ports close to the area they were now entering, and as the armies rushed forward the lines of supply back to the Normandy beaches and ports were lengthening hourly.

The task now prescribed for the First Canadian Army was to “complete the destruction of enemy forces” within the Army boundaries west of the Seine and thereafter to cross the Seine and advance along the general axis Rouen–Neufchâtel–Abbeville–Hesdin–St. Omer–Ypres. The boundary between the

Sketch 20: The Pursuit to the Seine, 22–30 August 1944

Canadian and British Armies would run through Le Neubourg, Louviers and Pont de l’Arche and on through Neufchâtel to Hesdin.

The 2nd Canadian Corps was to plan and make initial preparations for an opposed crossing of the Seine between Pont de l’Arche and Elbeuf, and subsequently for securing additional bridgeheads both above and below Rouen as far west as Caudebec-en-Caux. The probability of one infantry division from the 1st British Corps being transferred temporarily to General Simonds for the purpose of securing the bridgehead east of the last-named place was forecast. The Seine once crossed, the 2nd Corps was to establish itself in the area north of Rouen, “pushing out strong reconnaissances, preparatory to further advance in the direction of Neufchâtel and Dieppe”, while the 1st British Corps would “proceed simultaneously with the rapid clearance of the Havre peninsula” west of a line running north-west from Rouen to Fontaine-le-Dun.

The day after Crerar sent out this directive, General Montgomery issued a new one to the 21st Army Group.9 This was the first such order which did not have specific application to the US forces. It noted the nature of the orders which had been issued to General Bradley’s 12th Army Group, but was not a formal instruction to that formation. Its opening paragraphs, describing the “general situation”, should perhaps be quoted:

1. The enemy has now been driven north of the Seine except in a few places, and our troops have entered Paris. The enemy forces are very stretched and disorganized; they are in no fit condition to stand and fight us.

2. This, then, is our opportunity to achieve our further objects quickly, and to deal the enemy further heavy blows which will cripple his power to continue in the war.

3. The tasks now confronting 21 Army Group are:

a. To operate northwards and to destroy the enemy forces in NE France and Belgium.

b. To secure the Pas de Calais area and the airfields in Belgium.

c. To secure Antwerp as a base.

4. Having completed these tasks, the eventual mission of the Army Group will be to advance eastwards on the Ruhr.

5. Speed of action and of movement is now vital. I cannot emphasize this too strongly; what we have to do must be done quickly. Every officer and man must understand that by a stupendous effort now we shall not only hasten the end of the war; we shall also bring quick relief to our families and friends in England by over-running the flying bomb launching sites in the Pas de Calais.

Intention

6. To destroy all enemy forces in the Pas de Calais and Flanders, and to capture Antwerp.

The particular tasks of the First Canadian Army were thus described:

10. Having crossed the Seine the Army will operate northwards, will secure the port of Dieppe, and will proceed quickly with the destruction of all enemy forces in the coastal belt up to Bruges.

11. One Corps will be turned westwards into the Havre peninsula, to destroy the enemy forces in that area and to secure the port of Havre. No more forces will be employed in this task than are necessary to achieve the object. The main business lies to the north, and in the Pas de Calais.

The Canadian Army was directed to operate generally “with its main weight on its right flank”, dealing with resistance by outflanking movements and “right

hooks”. The 6th Airborne Division was to be withdrawn from operations in time to be returned to England by 6 September; the 7th Armoured Division was to be transferred to the Second Army at once.

The Second Army was to push across the Seine “with all speed”, establish itself in the area Arras-Amiens-St. Pol and thence be prepared to drive on through the industrial area of north-eastern France into Belgium. Alternatively, part of the Army might be required to operate north-westwards in support of the Allied Airborne Army which at this time Montgomery was proposing to drop in the Pas de Calais ahead of the Canadian advance. It was important, immediately after the Seine crossing, to push a strong armoured force quickly ahead to seize Amiens. As for the 12th Army Group, the directive noted, “12 Army Group has been ordered to thrust forward on its left, its principal offensive mission being, for the present, to support 21 Army Group in the attainment of the objectives referred to in para 3 above.” The First US Army was being employed for this task, and was to advance north-east on the general axis Paris-Brussels and establish itself in the area Brussels-Maastricht-Liège-Namur-Charleroi. In conclusion, Montgomery wrote:

24. The enemy has not the troops to hold any strong position. The proper tactics now are for strong armoured and mobile columns to by-pass enemy centres of resistance and to push boldly ahead, creating alarm and despondency in enemy rear areas. Enemy centres of resistance thus by-passed should be dealt with by infantry columns coming on later.

25. I rely on commanders of every rank and grade to “drive” ahead with the utmost energy; any tendency to be “sticky” or cautious must be stamped on ruthlessly.

At the time when this directive was issued there seemed to be no limit to the possibilities of the situation. The only apparent cloud on the horizon was the supply problem. The news of the liberation of Paris had just electrified the world. A rising in the city forced the Supreme Commander’s hand, and Allied troops, including General Leclerc’s 2nd French Armoured Division, had entered the city early on 25 August, and that day the tactical headquarters of the 5th US Corps of the First US Army was established at the Gare Montparnasse.10 The same day the Second British Army made contact south-west of Le Neubourg with the 19th US Corps which had advanced across their front, and the 43rd (Wessex) Division reached the Seine at Vernon (where the Americans advancing along the left bank had arrived some days before) and established a small bridgehead in the face of resistance from the enemy on the north bank.11 On 25 August also First Canadian Army made contact with the First US Army at several points north and north-east of Le Neubourg, and subsequently reported, ‘By last light our forces were within striking distance of the Seine crossings and formations of the 2nd Canadian Corps were preparing their individual attacks.”12 At 5 p.m. on 26 August the scout platoon and D Company of The Lincoln and Welland Regiment, using shovels as paddles to propel a small boat, crossed the Seine near Criquebeuf, above Elbeuf, and took up a position on the far shore.13 They were the first Canadians across the river.

Nevertheless, an unpleasant check lay just ahead-a check which suggested that the optimistic forecasts of an early end of the war which were current at this moment might not be entirely well founded. At the same time a special Canadian administrative problem which was to have wide repercussions was beginning to emerge.

The Infantry Reinforcement Problem Appears

Casualties in the infantry arm in Normandy had been heavier, and those in other arms lighter, than had been anticipated in Allied planning. This was a situation common to the British, American and Canadian armies.14 All had grossly miscalculated. The Canadian Army Overseas had accepted as a basis for planning the “rates of wastage” used by the British War Office, which had much wider experience of operations than the Canadians. These rates however were undoubtedly based mainly on the fighting in North Africa, and they proved inapplicable to North-West Europe. To state the matter in its simplest and starkest terms, the War Office had predicted that in periods of “intense” activity 48 per cent of the casualties would be suffered by the infantry, 15 per cent by the armoured corps and 14 per cent by the artillery; in “normal” periods the parallel percentages would be 34, 11 and 16. But down to 17 August in Normandy the infantry had had 76 per cent of the Canadian casualties, the armoured corps only 7 per cent and the artillery 8 per cent. It may be noted that these figures were almost identical with those deriving from experience in the Italian theatre, where Canadian troops had been in action since July 1943. However, the actual force engaged there, and the losses, had been relatively small; Canadian armour had not fought on any considerable scale; and it was rightly felt that this limited experience was an insufficient basis for revision of the War Office rates.15

In the Canadian Army in Normandy the problem began to present itself even before the final attack to break out of the bridgehead. It first appeared in an urgent form in the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, which had had exceptionally heavy casualties in the July battles. On 7 August General Simonds had reported to Headquarters First Canadian Army that the 2nd Division was 1900 men short; he estimated that it might conceivably be 2500 short on the completion of Operation TOTALIZE, then about to be launched:

No definite information is available to this Headquarters concerning further arrivals of infantry general duty reinforcements and it is felt that, for one reason or another, the system for the supply of reinforcements to this theatre is not functioning satisfactorily and that reinforcements in sufficient quantities to take care of actual and probable losses are not immediately available.16

On 26 August, although considerable numbers of reinforcements had been received in the interval,17 the field returns18 show the nine infantry battalions of the 2nd Division as deficient a total of 1910 “other ranks”. The two French-speaking units were worst off, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal being 331 men short and Le Régiment de Maisonneuve 246; however, although these were the largest deficiencies, three other units were short more than 200 men each. An attempt had

already been made to improve the situation in the French battalions by “combing” Canadian units in the United Kingdom for French-speaking personnel.19

The situation concerning infantry reinforcements generally was to be a serious source of anxiety throughout the late summer and autumn, in the field and also in London and Ottawa. In the meantime, it is evident that the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was considerably under strength as it approached the Seine, where it had a hard battle to fight. It is only fair to add that the German formations salvaged from Normandy were in much worse condition.

It is time to turn to the German side and note the plans and dispositions which the enemy had been able to make for withdrawing his forces and delaying our advance.

On 20 August Hitler had issued a directive20 requiring the Commander-in-Chief West to hold the bridgehead west of Paris, prevent a break-through between the Seine and the Loire in the direction of Dijon, re-form the battered Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies behind the Touques with the armour on the southern flank, and, finally, if the area forward of the Seine could not be held, to fall back to and defend the line River Seine–River Yonne–Canal de Bourgogne–Dijon–Dôle to the Swiss border. (On a small-scale map, this appears as a pleasantly straight line across eastern France.) But the bridgehead south of the Seine at Paris was still to be held at all costs. Hitler wrote, “If necessary, the battle in and around Paris must be conducted regardless of the [possible] destruction of the city.” As has already appeared, the shattered German armies were far from equal to making this directive good. Nevertheless, their performance in this phase commands respect. The German forces, from the coast to the boundary with the First Army at Poissy, just west of Paris, were under the Fifth Panzer Army commanded by Colonel-General Sepp Dietrich. As we have seen (above, page 270) this Army’s formations had largely been reduced to mere shadows. It was now using in the line those divisions which had been least badly mauled. Three corps were under its command: the 86th nearest the coast, the 2nd SS Panzer in the centre and the 81st on the left.

On 24 August the Commander-in-Chief West (Field-Marshal Model) emphasized the importance of covering the lower Seine crossings to ensure that his retreating forces got across the river. His order for this date21 specified operations as follows:

Withdrawal of the western wing in accordance with the situation. The eastern wing to stand fast under any circumstances and to be strengthened by all available forces in order to safeguard the crossings of the lower Seine. Elements of Seventh Army not needed and all vehicles to be ferried across the river forthwith at high pressure and without let-up.

The available armour was being concentrated during this day in the area northeast of Le Neubourg to prevent a break-through along the Seine, where the Americans had pushed the German covering group back from Vernon to the vicinity of Louviers.22 And in fact the Germans succeeded in preventing their retiring forces being cut off and encircled in the manner planned by the Allied commanders. The American sweep penetrated to Louviers and Elbeuf—a fine

advance-but not “beyond” (above, page 267). The British and Canadians had now drawn level with the Americans; and the enemy’s resistance had suddenly stiffened. On the threshold of his river crossings west of Elbeuf he fought a very effective rearguard action.

On 25 August, it appears, the 331st German Infantry Division was made responsible, under the 81st Corps, for covering the withdrawal across the Seine in the Rouen area.23 This was a good division commanded by Colonel Walter Steinmuller. It had been under the Fifteenth Army north of the Seine until early August, when it was moved south. It did not become involved in the disaster of the Pocket, but took part in the general retreat to the Seine and in it lost one of its three grenadier regiments. It now found itself defending a line west of Bourgtheroulde, while behind it a great mass of German armoured and other vehicles stood waiting to cross the river. Its task was to cover the crossings about Rouen and Duclair, at the tops of the two great loops of the Seine north and east of Bourgtheroulde. It was very evident that Steinmuller’s division would not in itself be equal to this. Accordingly, on the afternoon of the 25th Fifth Panzer Army directed Lieut.-General Graf von Schwerin, commanding the tank force that had been collected north-east of Le Neubourg, to form two armoured groups, one from the remnants of the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions, and the other from those of the 21st and 116th Panzer Divisions, to block the necks of the river loops south of Rouen and south of Duclair.24

On 25 August the 2nd US Armoured Division, the First US Army’s spearhead, fought its way into Elbeuf and made contact with the 4th Canadian Armoured Division about Le Neubourg and also with elements of the 7th British Armoured Division west of the town.25 The 4th Division recorded, “The fact that the Americans had beaten the Div to this area West of the Seine somewhat dampened the good spirits but they were indeed a welcome sight.”26 Arrangements were now made for the Americans to withdraw, and during the next couple of days the British and Canadian armies relieved them in their corridor along the south bank of the Seine.27

The 2nd Canadian Division captured Bourgtheroulde on 26 August (the Canadian Black Watch overcoming determined if disorganized opposition from snipers and a troublesome anti-tank gun in the centre of the town)28 and the 3rd took over Elbeuf.29 The German ferrying operations went badly this day, few units getting across the river. The Fifth Panzer Army recorded that the 86th Corps, resisting the 1st British Corps, asked for permission to remain on the south bank for another night:

The Corps was therefore given orders to stand fast on 27 Aug in the line Risle Estuary–Corneville–Bourg Achard. 81 Corps was directed to fill the gap from Bourg Achard to Moulineaux with 331 Inf Div. Group Schwerin was instructed to seal off the Seine loop at Orival [just north of Elbeuf].30

On the 27th, then, the 81st Corps was standing fast on the line Bourg Achard–La Bouille–Orival. The armour was disposed with the remnants of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer and 21st Panzer Divisions between Bourg Achard and La Bouille,

and the 116th Panzer and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions between La Bouille and an area north of Orival.31

General Simonds on the morning of 25 August had issued verbal orders to his divisional commanders for the crossing of the Seine; these were confirmed in writing that evening.32 They required the 4th Division to seize “by coup-de-main” a bridgehead beyond the Seine in the area of Pont de l’Arche and Criquebeuf and thereafter advance directed on Forges-les-Eaux. The 3rd Division would seize in the same manner a bridgehead including Elbeuf and the railway bridge at Port du Gravier to the north. It was thereafter to advance on Neufchâtel. As for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, it was to “clear the meander” south of Rouen and, “by coup-de-main” as in the case of the other divisions, seize bridgeheads at the railway bridge at Oissel on the east side of this loop and at the bridges at and south of Rouen. As a result of the German plans and the determination with which they were carried out, the Corps Commander’s orders proved difficult to execute.

On the morning of 27 August the infantry of the 4th Division began to cross the Seine, using stormboats, to develop the small bridgehead already held by The Lincoln and Welland Regiment opposite Criquebeuf (above, page 283). The 10th Infantry Brigade met heavy opposition and suffered severe casualties in attempting to enlarge this, and failed to capture the high ground north of Sotteville-sous-le-Val and Igoville during the day.33 It was evident that the Germans—here, the 17th Luftwaffe Field Division34—intended to do their utmost to block any advance on Rouen from this direction. The intention of putting the 4th Division’s armoured brigade across the river in this area was abandoned, and on 28 August it crossed at Elbeuf, where there was a more secure bridgehead. The 3rd Division in fact had met little opposition in ferrying itself across the river here on the 27th;35 the enemy evidently had no troops to spare to try to keep us out of the low-lying river loop opposite Elbeuf, but was content to concentrate on holding the high ground beginning some four miles east, which commanded both the approaches from Elbeuf and the 10th Brigade’s bridgehead. The 9th Field Squadron RCE, working under shell and mortar fire, got two tank-carrying rafts into operation at Elbeuf before nightfall, and early the next morning the 8th GHQ Troops Royal Engineers completed a Bailey pontoon bridge also capable of carrying tanks.36

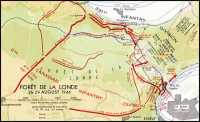

The Forêt de la Londe

It was the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division that met the heaviest opposition in this phase, for it fell to it to attack the positions which the enemy now considered most important: those immediately covering the Rouen crossings and their approaches.

The Germans held exceptionally favourable ground. The open end of the sack-shaped loop at the top of which Rouen stands is an isthmus roughly three miles wide, covered by the eastern end of the rugged area of thick woodland known as the Forêt de la Londe. Parts of this largely uninhabited region rise as high as

120 metres above the river. Just west of the narrowest point of the isthmus the forest is intersected by a valley similar to an old river-bed, running from near Moulineaux* on the north to Port du Gravier on the south. This depression carries two railway lines which traverse it with the assistance of four tunnels. On the high ground immediately east of it the Germans had disposed their main forces.

If only because the enemy’s operations were necessarily on a basis of short-term improvisation, they presented a difficult problem to our Intelligence, which at first underestimated the German strength in the forest. A 2nd Canadian Corps intelligence summary issued on the night of 26-27 August described the enemy troops still “putting up stiff resistance” south of the Seine on our left flank as “nothing more than local rearguards”.37 A 2nd Division summary sent out in the afternoon of 25 August contained the statement, “Civilians report large concentration of tanks early today in Forêt de la Londe”, but this report was evidently considered to have been discredited, since a revised version issued five hours later omitted it. The division issued no more summaries until the night of 27-28 August. On the basis of the information available the GOC’s appreciation early on the 27th was, “Boche has pulled out, and little opposition can be expected.” The division’s reconnaissance regiment was accordingly ordered to push forward to Rouen.38 It was soon checked.

Incomplete records make it difficult to reconstruct the progress of planning, but at one stage the intention apparently was that the 6th Brigade should clear the Forêt de la Londe of such enemy as might be present, while the 4th and 5th crossed the Seine at Elbeuf, alternating with the brigades of the 3rd Division. But the ultimate decision was to attack the forest on the morning of 27 August with the 4th Infantry Brigade on the right and the 6th on the left. The final plan settled upon for the 4th Brigade was that it would advance through Elbeuf with The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry leading, followed by the Essex Scottish; The Royal Regiment of Canada was in reserve. The two leading battalions were to seize the high ground overlooking the river north of the hamlet of Port du Gravier, and the Royal Regiment was to pass through and take up a position just south of Grand Essart.39 In attempting to carry out this plan the brigade ran into the enemy’s main positions and made little progress.

Leading the brigade’s advance up the main road in the darkness, the RHLI by mistake took the left fork of the road at Port du Gravier instead of continuing on up the river. Some 500 yards north they found the road through the valley blocked. Machine-gun and mortar fire came down and the battalion was forced back to the high ground immediately west of Port du Gravier. It was clear that the enemy was strongly posted on the heights north of the valley, and the unit went on having casualties. The Essex Scottish, coming up in rear of the RHLI, came under fire from Port du Gravier and took positions along the river bank.

* The valley does not actually break through the Seine escarpment at Moulineaux, but opposite the village there is a gap or “col” in the line of hills. During the Franco-Prussian War, on 4 January 1871, the Germans, attacking from the direction of Rouen, defeated and scattered French levies attempting to hold the line La Bouille–Elbeuf. See Major-General Sir F. Maurice, ed., The Franco-German War, 1870-71, by Generals and Other Officers Who took Part in the Campaign (London, ed. 1914), 358-60.

The brigade commander, Brigadier J. E. Ganong, ordered the reserve battalion, the Royal Regiment, to make a wide flanking movement to the north-west, cross the Port du Gravier–Moulineaux road and get behind the enemy positions holding up the other battalions. This advance, beginning about 11:30 a.m. on the 27th, made slow progress through the woods. During the afternoon the Royals made contact with Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, who were advancing on the 6th Brigade’s right; and a little later Divisional Headquarters placed the Fusiliers under command of the 4th Brigade. The Royal Regiment’s attack across the road was cancelled, and it was ordered instead to move northward to a rendezvous in the woods where the Essex Scottish was to join it.40 This junction however was never made, and the brigade commander was forced to report late that evening,41

Attack arranged for this afternoon bogged down entirely in thick wood. Have ordered units concerned back to South. As soon as location received from Essex I intend to put on attack on South Objective with Essex and on North Objective with Fus MR...

Shortly before midnight General Foulkes conferred with Brigadier Ganong42 and plans were made for the next day. The Royal Regiment was to make a further attempt to out-flank the machine-gun positions dominating the line of advance, while the Essex tried again to punch through on the right. Les Fusiliers Mont Royal now reverted to the 6th Brigade.43

Early in the morning of the 28th the Royal Regiment, then in position near a flag station or “halt” in the middle of the isthmus on the more westerly of the two railway lines through the valley, began an attack intended to capture a dominant area of high ground designated MAISIE, whose western portion formed a salient angle in the eastern wall of the valley, through which the other railway line tunnelled. Just as the move was about to begin, rations and water arrived. The battalion diary indicates the conditions under which the troops were fighting:

As the men had, generally speaking, been without water for about 18 hours and without food, except for odd scraps which they had carried with them, for a longer period, the Acting CO [Major T. F. Whitley] took it upon himself to allow the troops to eat and fill their water-bottles before starting the move. This resulted in C Coy crossing the start line at first light instead of in darkness, but it is extremely doubtful whether the darkness would have assisted our troops in any way as enemy positions had not been pinpointed.

C Company’s immediate objective was “Chalk Pits Hill”, another but lower salient feature north-west of MAISIE. It failed to capture it, and suffered heavily in the attempt. Major Whitley now called for artillery concentrations to prepare the way for a battalion attack. This took time to arrange, and “permission could not be obtained to lay down a medium concentration on Chalk Pits Hill itself as the exact position of units of 6th Bde on our left was not known”. At 11:30 a.m. the battalion attacked. On the left flank Chalk Pits Hill again resisted all efforts; on the right the line of the second railway was reached and since it seemed that progress was being made the company here was reinforced with a second. However, these two companies likewise met heavy opposition and became widely separated from the rest of the battalion; and the attack again came to a stop.44

On the right of the brigade front the Essex Scottish fared no better. Two companies went forward about 1:30 p.m. after heavy preparation by artillery and

medium machine-guns; but as they moved down the steep slope into the valley at Port du Gravier they met heavy fire and were forced to dig in along the road north of the village. They withdrew after night fell.45

It appears that in the morning of the 28th there was a momentary intention to abandon the attack in the forest and move the 2nd Division across the Seine through the Elbeuf bridgehead, but that subsequently it was decided to persist, due possibly to the heavy opposition being met in that bridgehead.46 At 4:00 p.m. General Foulkes held an orders group and discussed with Brigadier Ganong and the three battalion commanders a plan to capture MAISIE by passing one battalion by night through the positions of the two Royal Regiment companies on the right, followed by a swing south-east to take the position which was holding up the Essex. The Royal Regiment diarist recorded,

The COs of both the RHLI and the R Regt C were strongly of the opinion that this task was beyond the powers of a Battalion composed largely of reinforcement personnel with little training. It was suggested that the enemy was actually stronger than Intelligence reports had indicated, and that the ground was immensely favourable for defence.

However, the operation was considered necessary and the RHLI made the attempt. Major H. C. Arrell was in command, since the CO, Lt.-Col. G. M. Maclachlan (who incidentally had been wounded on 12 August but returned to duty next day) had been taken ill during or just after the orders group.47 The battalion got forward slowly, and dawn had broken on the morning of the 29th before it crossed the first railway. Heavy concentrations of artillery smoke were laid down to assist it, but machine-gun fire from the forest-clad heights stopped it.48 At 1:26 p.m. it reported that its three forward companies had lost heavily. Two of them had been withdrawn some distance. Heavy machine-gun and mortar fire was still coming down. The Acting CO felt that it was “impossible to proceed with original plan and that position must be taken from another direction”. The battalion held on for the rest of the day and then withdrew to the Royal Regiment area.49

During the morning of 29 August the Essex Scottish on the right of the brigade front discovered that the Germans appeared to have drawn back, and the battalion advanced some 800 yards beyond the railway at Port du Gravier.50 In fact, this was the last day of resistance in the area; the enemy was beginning to pull out.

We must now go back some days and deal with the 6th Infantry Brigade’s fight on the left sector of the 2nd Division front. This brigade was now commanded by Brigadier F. A. Clift, Brigadier Young having been promoted to Major General and appointed Quartermaster General in Ottawa. On 26 August the 6th Brigade was ordered to pass through the 5th, then in the Bourgtheroulde area, and clear the Forêt de la Londe. The objectives prescribed were, for The South Saskatchewan Regiment, the area La Bouille–Le Buisson; for The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, the area La Chenaie–Moulineaux, farther east; and for Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal the portion of the isthmus directly east of the railway triangle or Y in the northern sector of the valley through the forest.51 This had the effect, though we did not know it at the

Map 6: Forêt de la Londe, 26–29 August 1944

time, of directing the Fusiliers at the northern section of the enemy’s main line of resistance.

On the morning of the 27th the brigade advanced along the road running north-east from Bourgtheroulde, except that Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal used the road running directly east. The South Saskatchewan Regiment, in the lead, soon found that the western portion of the brigade’s objectives was clear of the enemy, but the Camerons, moving east through the forest in the direction of Moulineaux, ran into strong opposition including tanks and self-propelled guns and did not succeed in taking all their objectives. As for Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, they met the enemy at Le Buquet west of Elbeuf, and pushed him back towards his main line.52

Shortly after midnight of the 27th–28th Brigadier Clift issued orders for further advance. The objectives assigned were areas directly west of Oissel,53 and it must be assumed that the Divisional Commander hoped that the 6th Brigade would be able to break through in the north and outflank the opposition which was holding up the 4th farther south. However, the 6th Brigade had no better fortune than the 4th. The South Saskatchewan Regiment had got as far as the area of the railway triangle south of La Chenaie when they came under sniper and machinegun fire from the high forested ridge to the left. The leading company lost very heavily and the battalion fell back to Le Buisson and reorganized. Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, coming back under the 6th Brigade (above, page 289), should have followed the South Saskatchewan, but machine-gun and mortar fire kept them virtually immobilized through 28 August in the southern area west of Port du Gravier.54

Another attempt was made in the evening, The South Saskatchewan Regiment again seeking to reach the high ground west of Oissel with the assistance of the Camerons, who had spent the day entrenched on their first objective west of Moulineaux and under heavy shell and mortar fire. An artillery barrage was provided, but the South Saskatchewan started late and did not get the full benefit of it. The battalion advanced east along the escarpment overlooking the Seine, past the castle of Robert the Devil on the col above Moulineaux (captured by the Germans in the 1871 battle, and called in the South Saskatchewan diary “the monastery”). It was again held up near the Y. The Acting CO, Major F. B. Courtney, was killed when his carrier struck a mine. Further efforts during the night and early morning had little better result; and at first light on the 29th an enemy counter-attack pushed the South Saskatchewan back to the col. They had suffered very heavily, and continued to suffer during the day. In the afternoon a newly-arrived reinforcement officer was killed by a sniper before he could join his company. The Camerons were nearby (their CO, Lt.-Col. A. S. Gregory, was wounded and evacuated in the course of the day). Brigadier Clift planned to use them and the South Saskatchewan in a further attack. Before this could be done, however, the brigadier himself was wounded. Lt.-Col. J. G. Gauvreau of the Fusiliers took over. On the afternoon of the 29th General Foulkes cancelled the proposed attack and ordered the brigade merely to consolidate on the line of the valley. That evening the South Saskatchewan had another misfortune; deceived by what was apparently a fictitious message originated by the enemy, they fell back some

distance. Subsequently the remnants of the battalion* moved forward once more, supported by tank and artillery fire, and re-established themselves around the castle. During the night the enemy withdrew.55

The 5th Brigade took only a limited part in the operations in and about the Forêt de la Londe. However, the brigade was moved up on 28 August to support the units fighting in the forest. The Calgary Highlanders, taking over the positions west of Moulineaux formerly occupied by the Camerons, were painfully pounded with shell and small arms fire throughout the 29th, and suffered very considerably.56

It is evident that in these three days of unpleasant fighting the 2nd Division failed to make any important impression upon the strong enemy positions east of the valley in the Forêt de la Londe. The hard-fighting Germans holding them carried out their task of covering the river crossings at Rouen, and withdrew only when it had been completed.

The difficulties of the division’s task were very considerable. As the 4th Brigade reported,57 the enemy fought skilfully from commanding positions, excellently camouflaged. His mortar fire was accurate and the positions of the weapons were frequently changed. The dense woods made it difficult to keep direction, and to make matters worse our maps were inaccurate.† The difficulty of pin-pointing the enemy’s positions (and for that matter our own) rendered it impracticable to make full use of our artillery, and the same consideration, combined with the fact that the weather was rather poor for flying on 28 August and very poor on 29 August,58 deprived our troops of any effective air support.

The 4th and 6th Brigades suffered very heavily in this business. Of the battalions, only Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal (which as we have seen went into the battle already very weak) got off lightly, with 20 casualties for the three days 27-29 August. The South Saskatchewan Regiment suffered 185 casualties, 44 of them being fatal. The Royal Regiment of Canada had 118 casualties, the Camerons 99, the Essex Scottish 96, and the RHLI 59, making a total for the six battalions of 577. Lt.-Col. F. N. Cabeldu of the Canadian Scottish Regiment took command of the 4th Brigade on 31 August.59

There had also been stiff fighting in the 3rd and 4th Divisions’ areas above Elbeuf. The 3rd met opposition as it advanced eastward on the 27th. The Canadian Scottish Regiment had a hard fight for a foothold on the high ground at

* The South Saskatchewan diarist writes: “At 1400 hrs [2:00 p.m.] the fighting strength of the bn [presumably the rifle companies] was approx 60 other ranks with Major E. W. Thomas as Commanding Officer, Capt. H. P. Williams in charge A Coy, Lt. N. A. Sharpe in charge B Coy, CSM [J. A.] Smith in charge C Coy, Lt. F. Lee in charge D Coy and Sgt. Fisher SE acting as bn Intelligence Officer.” CSM Smith received the Military Medal for his work during the day.

† The Allies had very insufficient data on which to base operational maps of northern France and Belgium. No accurate edition of maps of France was available. To provide adequate maps modern methods utilizing aerial photography were used in conjunction with the best available French maps; but the lack of sufficient and accurate positional and height control, coupled with shortage of personnel experienced in special mapping techniques, resulted in errors. In the later stages of the campaign the situation was better, excellent Dutch and German large-scale maps being available to provide a basis for operational maps of the Netherlands and Germany. With special reference to the Forêt de la Londe, comparison with air photographs shows that neither the 1:25,000 scale maps nor the 1:50,000 maps used at the time were really adequate aids for fighting in such difficult country.

Sketch 21: The Seine Crossing, 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions, 26–30 August 1944

Tourville.60 On the 28th this was developed and the 7th Infantry Brigade linked up with the 10th Brigade’s bridgehead on the right. On this day the 10th fought its way on to the heights dominating Igoville, The Lincoln and Welland Regiment losing heavily in capturing Point 88.61 On the 29th resistance lessened. The 4th Armoured Brigade, having come up from Elbeuf, advanced north-east, while the 3rd Division, with the 9th Infantry Brigade leading, moved north towards Rouen. The opposition was now “persistent but light”. On the afternoon of 30 August the 9th Brigade pushed patrols into Rouen. Brigadier Rockingham himself was first into the main square, and exchanged shots from his armoured car with a German party which was then dealt with by a patrol of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada.62

On the First Canadian Army’s left sector, that of the 1st British Corps, the story had been not dissimilar from that farther east, though the fighting was less fierce. The Germans offered opposition in the Forêt de Brotonne covering the crossings at Caudebec-en-Caux. The 49th Infantry Division took over here from the 7th Armoured Division. The 1st Corps reported on 29 August, “No organised defences but going slow owing to density of forest.”63 Later that day it was reported that there was “no organized resistance” left in the area. On the afternoon of the 30th reconnaissance elements of the 1st Corps crossed the Seine at

Duclair, Caudebec-en-Caux and points below and discovered that the enemy had withdrawn.64

In spite of the check inflicted upon us in the Forêt de la Londe, the enemy suffered tremendously in the attempt to withdraw across the Seine. For days, whenever the weather permitted, the Allied air forces struck at the concentrations of vehicles piled up south of the crossings. On 25 August the Luftwaffe made a serious attempt to cover these crossings, with the result that fighters of the US Ninth Air Force claimed 77 enemy aircraft destroyed in combat and 49 more on the ground.65 Artillery fire, including the Americans’ after their advance into the Elbeuf area,66 also inflicted great damage on these masses of men and vehicles. When our troops advanced to the river they found scenes comparable with those in the Falaise Gap. In the whole area of what British operational researchers called “the Chase”, roughly the region from Lisieux and Vimoutiers eastward to the Seine from Louviers down to Quillebeuf, they counted a grand total of 3648 vehicles and guns, including 150 tanks and self-propelled guns, and this was certainly a very incomplete count. The greatest graveyard was on the south bank of the river at Rouen itself: “a mass of burnt vehicles and equipment” consisting of 20 armoured vehicles, 48 guns and 660 other vehicles.67

Nevertheless, the Germans, by a great effort of improvisation, succeeded in getting large numbers of vehicles across the river. The Fifth Panzer Army recorded that between 20 August and the evening of the 24th approximately 25,000 vehicles of all types had been withdrawn over the Seine.68 The reason for this success is fairly evident; on the four days 20-23 August the weather was bad and air operations were seriously curtailed.69 On the 24th the weather was better, and during the next three days large-scale air operations were again possible. These were probably the days when the heaviest damage was inflicted and the Germans got fewest vehicles across the river.70

Most of the crossings had to be made by ferry, since few bridges were in operation. On 25 August Army Group D recorded that the completion of a floating bridge at Rouen had been made impossible by the destruction of three boats.71 Many ferry craft were also destroyed. The British investigators, examining the river soon afterwards, came to the conclusion that the Germans had used 24 crossing-sites, from Petit Andelys (near Les Andelys) to Quillebeuf near the mouth of the river. Of all the crossings, it appears, the one which carried most traffic was that at Poses, about four miles east of Pont de l’Arche. This was actually the only point where the researchers considered the use of a bridge confirmed.*72 It was a pontoon bridge, which is said to have been in use for five nights and three days; a local inhabitant claimed that he recorded 16,000 vehicles as passing over it. It appears that the Allied air forces made no heavy attacks here.73 It is likely that the bridge was dismantled during daylight hours on days when the weather was

* There were evidently others in at least partial use. On 30 August a Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders patrol crossed the partly-demolished railway bridge at Rouen. It reported the bridge impassable to vehicles, but also reported that civilians stated that “several thousand” horse-drawn vehicles and guns had crossed it during the past ten days. Air photographs taken on 26 August seem to indicate that motor vehicles were then using this bridge. On 25 August General Montgomery was told that the Germans were using three pontoon bridges-at Poses; a short distance upstream from Poses; and at Elbeuf.

good for flying. No important road crossed the Seine at Poses and there was no peacetime bridge.

It is impossible to determine with precision either how many vehicles the Germans had in Normandy south of the Seine or how many survived the Seine crossing. But the Allied researchers came to the conclusion that over 12,000 motor vehicles of all sorts were destroyed or abandoned south of the river.74 And the approximate figure of 25,000 given by Fifth Panzer Army as crossing successfully during. the most favourable period (above, page 294) presumably includes horse-drawn transport.

During the last stages of the German resistance south of Rouen the 74th German Corps took over the Forêt de la Londe area from the 81st, and the infantry was instructed to relieve the armour so the latter could withdraw.75 Steinmuller states that the last elements of his 331st Division crossed the river in the early morning hours of 30 August, that it was the last German formation to cross, and that “no man and no vehicle fell into the hands of the enemy”.76

The German withdrawal across the Seine provides a good example of the application of the related military principles of Concentration and Economy of Force. Carried out by an army which had just suffered a catastrophic defeat and enormous losses in personnel and material, it must be accounted a fine achievement. The forces available to the German command were small, but they were used where they could be employed to the best advantage. The most essential crossings were effectively covered, and by hard fighting and effective use of ground the Germans held up our advance until the great body of their surviving troops had got away. But what they had achieved was only a successful local delaying action. Their strength was quite unequal to the prolonged defence of the Seine line which Hitler had demanded. The next phase would see them retiring rapidly far to the north and east in search of a position where the situation could be stabilized.