Chapter 14: Clearing the Coastal Belt and the Ports, September 1944

(See Map 7 and Sketches 25, 26 and 27)

In the early autumn of 1944 several sequences of events important to this history were proceeding simultaneously in North-West Europe. In the preceding chapter we abandoned the course of events in the First Canadian Army sector to discuss the higher direction of the campaign and happenings elsewhere on the front. We must now return to First Canadian Army and deal with its operations during the month of September. Those operations themselves were widely dispersed, and it is difficult to describe them even summarily without occasionally taking some liberties with chronology.

The Advance Beyond the Somme

On 3 September, while the 2nd Canadian Corps was crossing the Somme, the 1st British Corps was closing in on Le Havre and the Second British Army was speeding through Brussels on its way to Antwerp, Field-Marshal Montgomery issued another directive.1 It was brief and general, but it indicated the breadth of the possibilities of the situation at that moment. His intentions now were, first, “To advance eastwards and destroy all enemy forces encountered”; and secondly, “To occupy the Ruhr, and get astride the communications leading from it into Germany and to the sea ports.” On 6 September the Second Army was to advance eastwards with its main bodies from the line Brussels–Antwerp, directed on the Rhine between Wesel and Arnhem. The Ruhr was to be “by-passed round its northern face, and cut off by a southward thrust through Hamm”. The First US Army, advancing with its two left corps directed successfully upon the lines Maastricht–Liège, Sittard–Aachen and Cologne–Bonn, would “assist in cutting off the Ruhr by operations against its south-eastern face, if such action is desired by Second Army”. The Belgian and Dutch contingents, which had been serving under General Crerar since the moment when the initial advance from the old bridgehead was undertaken, were now transferred to the Second Army. This was undoubtedly due to the fact that that army was already operating in Belgium, and would shortly enter the Netherlands. As for First Canadian Army itself, its tasks

had already been defined. Now they were summarized in a single somewhat bleak sentence:

Canadian Army will clear the coastal belt, and will then remain in the general area Bruges–Calais until the maintenance situation allows of its employment further forward.

As we have seen, the Fifteenth Army had had time to occupy the line of the Somme in the Canadian sector and had destroyed the bridges. However, the rapid advance of the Second Army on its left imperilled and dismayed the German formation, and it withdrew from the Somme without offering serious resistance. The necessity of bridging the stream was the main difficulty encountered by First Canadian Army. Bridging began on the afternoon of 2 September, the 10th Infantry Brigade crossing the river in the area of Pont Remy to cover the operation. A “Class 40” bridge (capable of carrying tanks) was completed here during the morning of the 3rd and by noon the armour of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division had begun to cross. During the night the Polish Armoured Division had got part of its infantry across the Somme below Abbeville and repairs were undertaken to a bridge here to enable tanks to cross.2

The Poles now took the lead of the 2nd Canadian Corps advance and drove northward without meeting much opposition. By noon of 4 September they were reported in Hesdin. In accordance with the orders previously issued, the 4th Division concentrated immediately east of Abbeville to rest and reorganize. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division followed the Poles across the Somme and pushed north parallel to the coast. On the morning of the 4th its 9th Brigade crossed the river Canche near Montreuil and moved on towards Boulogne.3 Blown bridges on this river and the Authie were making trouble similar to that met with on the Somme. One of Field-Marshal Montgomery’s liaison officers reported on this day, “The problem facing 2 Cdn Corps at the moment is not German soldiers but bridging difficulties.”

In this phase, indeed, with the Army moving rapidly forward, the Engineers had constant bridging problems, especially as the First Canadian Army routes crossed the rivers flowing into the Channel near their mouths, where they were widest. There was a chronic shortage of bridging equipment during September. Simultaneously the construction or rehabilitation of airfields in the new areas for the wings of No. 84 Group was an equally important commitment of the RCE and RE units working under the Army’s Chief Engineer (Brigadier Geoffrey Walsh took over this appointment from Brigadier A. T. MacLean at the beginning of the month). This was likewise a very busy and exacting period for the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals. By 2 September the Army’s “main signals artery” was complete to Rouen; that day cables were successfully put across the Seine at Duclair (only to be broken two days later by a ferry dragging its anchor). On 9 September it was recorded that cable connection had been established with Headquarters 2nd Corps at Cassel; the Corps now had speech and teleprinter communication with Army “after being entirely on wireless for one week”.4 Mere distance was a serious problem for commanders and staffs, and particularly for Army Headquarters. General Crerar in the second week of September

Sketch 25: The Coastal Belt, 4-12 September 1944

was directing operations from Le Havre in the south to Bruges and Ghent in the north, a front of nearly 200 miles. Fortunately, his light Auster aircraft gave him the means of maintaining personal contact with his two corps commanders as well as with Field-Marshal Montgomery.

Early in September we had not yet appreciated that the Germans intended to fight for the Channel Ports; air reconnaissance had reported the Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk areas “deserted”,5 and indeed, as we have seen, it was only on 4 September that Hitler issued his order for defence (above, page 301). On the evening of the 4th General Simonds sent a directive6 to his divisional commanders emphasizing the objects of pursuit to the Scheldt and destruction or capture of all enemy south of the river within the Army boundary. The 2nd Canadian Division when it moved forward was to clear the coastal strip from Dunkirk to the Dutch frontier. The 3rd Canadian Division, having been previously directed to push through to the Dunkirk area (above, page 303), was now merely ordered to ensure that the 2nd Division’s route was clear and thereafter to reorganize about Calais. But by the night of the 5th-6th the 3rd Division had come up against the landward defences of Boulogne and established that the enemy was holding hard there. A momentary intention to contain Boulogne with one brigade while the balance of the division pushed on to Calais and Dunkirk7 was quickly abandoned, and soon after midnight a divisional operation order8 was issued: the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was now to “capture Boulogne and destroy its garrison”. The 7th Brigade was pushed on to seize high ground south-west of Calais and cover the flank of the operation.

On 5 September the Polish Armoured Division occupied St. Omer; on the 6th it crossed the Franco-Belgian frontier and overcame enemy resistance at Ypres and Passchendaele-names famous in an earlier war; on the 7th it reached Roulers. In the meantime the refreshed 4th Canadian Armoured Division had resumed the advance early on the 6th and pushed forward from St. Omer on the Poles’ left, directed on Bruges and Eecloo. Organized in two ad hoc battle groups named after Brigadier Moncel of the 4th Armoured Brigade and Lt.-Col. J. D. Stewart, who was commanding the 10th Infantry Brigade in Brigadier Jefferson’s absence through illness, the division pushed forward rapidly. On 8 September it came up against the next German delaying position, the Ghent Canal, a meandering waterway connecting historic Ghent (which the Second British Army had reached but not cleared on 5 September) and the beautiful old city of Bruges.9 The bridges were down, and the enemy intended to make full use of the obstacle to hold up our advance to the Scheldt.

On the evening of the 8th The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s) launched the division’s attack across the canal near Moerbrugge, some three miles south of Bruges. The unit diary remarks drily, “Apparently it was considered that the crossing would be a routine matter, since no boating material was brought up, and no serious artillery programme was laid on.” The Argylls however found two large punts and used them for the crossing. Mortar and 88-mm. fire came down, and the battalion suffered severely.

Nevertheless, at midnight it was “still clinging, rather precariously” to its narrow bridgehead on the further side. Fortunately, the Canadian attack had been made at the junction between the 245th and 711th German Infantry Divisions’ sectors,10 which tended to delay the enemy’s counter-measures. In the early hours of the 9th The Lincoln and Welland Regiment joined the Argylls in the bridgehead and the two units repulsed strenuous German efforts to dislodge them. During the day the sappers struggled to build a bridge; but in the words of the division’s General Staff diarist, “For the first time since we left the Falaise area the enemy was able to put down a truly effective concentration of fire with the result that the engineers could not get the bridge across in daylight.” However, it was duly completed during the night, and early on 10 September a squadron of the 29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) crossed to support the infantry. During the day the bridgehead was gradually extended and large numbers of prisoners were taken; but the ground and the closeness of the country (“much closer than the map indicates”) made progress slow.11

On 9 September, and again on the night of the 10th-11th, the Poles attempted to force the Ghent Canal on their own front in the area north-west of Aeltre, roughly halfway between Bruges and Ghent. Steep banks and deep water, combined with unfavourable conditions for artillery observation, lack of assault craft and heavy German opposition rendered the efforts fruitless. They were abandoned; and on the 11th, as the result of a decision by higher authority to regroup (below, page 330), the Poles moved to the Ghent area to relieve the 7th British Armoured Division.12

In the meantime, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, left behind at Dieppe to refit, had also begun to move forward again on 6 September. After concentrating west of St. Omer it began its task in the coastal area; since it was now clear that Calais as well as Boulogne was going to be defended, and the 3rd Division would have its hands full there, the whole coast from just east of Calais, including Dunkirk, now fell to the 2nd.13 On 7-8 September Brigadier Megill’s 5th Infantry Brigade captured Bourbourg, south-west of Dunkirk, and was then instructed to contain the Dunkirk garrison, estimated to be some 10,000 strong, which held a wide perimeter of outposts in the villages of Mardick, Loon-Plage, Spycker, Bergues and Bray Dunes.14

The Calgary Highlanders had begun operations against Loon-Plage—“a very slow, tedious and costly job”—on 7 September.15 They ran into very heavy opposition and before long each of their forward companies was reduced to a strength of only 30. Their diary says on the 8th, “We must give great credit to the artillery and heavy mortars, plus our own mortars, for the very valuable support they gave us throughout the attack.” Eventually the enemy withdrew and Loon-Plage was occupied on the morning of the 9th. Simultaneously, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada occupied nearby Coppenaxfort with the help of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment. The inhabitants’ celebrations were, unfortunately, abruptly terminated by the enemy’s mortars.16 During the following week the 5th Brigade’s activities were mainly limited

to probing the defences of Dunkirk and patrolling. Civilians contributed much useful information on the enemy’s dispositions. The troops remained under fairly severe and consistent shellfire, some of which was believed to come from heavy guns in Dunkirk. This static phase soon became trying, and a disgruntled diarist remarked: “We are really getting fed up with the monotony of this job—a somewhat depressing business.” The brigade learned on 15 September that the entire division would shortly move to the Antwerp sector. Its last operation before Dunkirk was the capture of Mardick on the 17th.17

In the meantime, east of Dunkirk, in the area of the Franco-Belgian border, the 6th Brigade, now commanded by Brigadier J. G. Gauvreau, occupied Fumes, Nieuport and La Panne. The South Saskatchewan Regiment at Nieuport received great assistance from the Belgian White Brigade, the national resistance movement, which furnished exact information concerning the enemy’s strength, defences and minefields.18

West of La Panne The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada occupied German coast defences, gaining shelter from the enemy’s artillery. On 12 September the 6th Brigade was directed against Bray Dunes and Bray Dunes Plage. During the next two days the Camerons made several unsuccessful attempts to capture this area. Aided by Typhoon aircraft and a supplementary operation by the South Saskatchewan, they finally cleared it on the 15th. Simultaneously, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, whose CO was now Lt.-Col. J. M. P. Sauve, took the nearby village of Ghyvelde, where they had been repulsed in earlier attempts.19 But the enemy showed no sign of relaxing his grip on Dunkirk, and the place could have been taken only by a major attack with heavy support.

Brigadier Cabeldu’s 4th Brigade, initially in reserve, had moved north on 9 September and occupied Ostend.* This not inconsiderable port had not been mentioned in Hitler’s directive of 4 September, and the Germans did not defend it, although the fortifications, including large concrete gun-positions with excellent fields of fire, impressed our troops as formidable. However, the harbour installations had been partly demolished, and the necessity of dealing with mines and sunken ships imposed delay on the use of the port. From 28 September, pending the opening of Antwerp, stores and bulk petrol flowed in through Ostend to alleviate the maintenance problem.20

Just east of Nieuport The Essex Scottish Regiment laid siege on 10 September to a coastal gun position of great strength. “What had appeared to be sand dunes were concrete dugouts and emplacements covered with sand. The position commanded all the surrounding country.” But the Essex brought so hot a fire against it—with the help of mortars and anti-tank and Bofors guns, as well as other supporting artillery—that the garrison surrendered on the 12th. The Commanding Officer (Lt.-Col. P. W. Bennett) recorded that 316 prisoners had been taken, at a cost to the Essex of two killed and three wounded, and that “the booty was absolutely terrific”.21

While the Essex were thus engaged, the remaining battalions of the 4th

* The 18th Armoured Car Regiment had been in Ostend the day before. It had also anticipated the 6th Brigade in Nieuport.

Brigade moved to the southern outskirts of Bruges to assist the 4th Armoured Division in that sector. Fortunately, the enemy withdrew without contesting possession of the city, and on 12 September elements of the 4th Infantry Brigade entered it on the heels of the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons).*22 The enthusiasm of the citizens knew no bounds; the diarist of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry remarked, “the people on seeing the vehicles became delirious and literally thousands of people swarmed about and prevented the vehicles from moving for close to an hour”. The brigade now turned south again to attack Bergues, a key feature of Dunkirk’s outer defences. But the area was badly flooded and an attack on the 15th by the RHLI bogged down. Then, even as the brigade was preparing to move with the remainder of the 2nd Division to Antwerp, the enemy withdrew and the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment was able to occupy Bergues on the morning of 16 September.23

The Need for the Channel Ports

Meanwhile, the changes in strategy described in the last chapter had begun to be reflected in the orders issued to the First Canadian Army. They appeared first in decreased emphasis upon the pursuit to the Scheldt and greater emphasis upon the capture of the Channel Ports. Subsequently the demand for the opening of Antwerp came to the fore.

We have seen Field-Marshal Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, on 6 September, calling attention to the importance of getting the port of Boulogne (above, page 310). That evening the C-in-C duly signalled to General Crerar:24

Would be very grateful for your opinion on the likelihood of early capture of Boulogne. It looks as if port of Antwerp may be unusable for some time as Germans are holding islands at mouth of Scheldt. Immediate opening of some port north of Dieppe essential for rapid development of my plan and I want Boulogne badly. What do you think are the chances of getting it soon.

This was delayed in transmission, but Crerar was already working on the problem25 and as we have seen the 3rd Canadian Division issued orders that same night for operations against Boulogne.

We have also seen (above, page 310) that on 9 September Montgomery calculated that, with the ports of Dieppe, Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais and some help from Le Havre, he could go to Berlin; with one good Pas de Calais port plus airlift and extra motor transport, he could go to “the Münster triangle”. At this time he saw the Canadian Army’s tasks as, first priority, capture of Boulogne; second priority, capture of Dunkirk; take over the Ghent area and clear the enemy pocket north of Ghent; then, as “last priority”, “examine and carry out the reduction of the islands guarding the entrance to Antwerp”.26 On the morning of the 9th General Crerar flew to the Field-Marshal’s headquarters for a conference at which Generals Dempsey and Hodges were also present. Crerar’s

* The regiment, normally part of 2nd Canadian Corps Troops, had one squadron. under the command of the 4th Division during the pursuit. This hard-driving squadron reported that, at times, it was up to 40 miles ahead of the division.

diary notes briefly, “Decisions affecting First Cdn Army were reached, i.e., speedy capture of Channel Ports within First Cdn Army boundary.” Later in the day Crerar issued a directive to his corps commanders.27 This underlined the maintenance difficulties which were being encountered and which rendered it impossible to press on as quickly and as powerfully “as the very favourable military situation urgently demands”. Crerar proceeded:

3. It follows that a speedy and victorious conclusion to the war now depends, fundamentally, upon the capture by First Cdn Army of the Channel ports which have now become so essential, if the administrative problem is to be solved, i.e. Le Havre, Boulogne, Dunkirk, Calais and generally in that order of importance.

4. 1 Brit Corps will attack and capture Le Havre on 10/11 Sep—unless unfavourable weather entails a further delay. On the completion of this important operation 1 Brit Corps will re-organize and reequip in the vicinity of Le Havre, pending an improvement in the administrative situation which will permit the movement of this formation to the Eastern sector of First Cdn Army area.

5. 2 Cdn Corps has already been directed to proceed, without delay, to capture Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais, preferably in that order, but without prejudice to the earlier and easier capture of anyone of them. If no weakness in the defences of these ports is discovered, and decisively exploited, in the course of operational reconnaissance—then a deliberate attack, with full fire support, will require to be staged, in each case.

6. In view of the necessity to give first priority to the capture of the Channel ports, mentioned above, the capture, or destruction, of the enemy remaining North and East of the Ghent–Bruges Canal becomes secondary in importance. While constant pressure and close contact with the enemy, now withdrawing North of R Schelde, will be maintained, important forces will not be committed to offensive action.

During 10 September the 2nd Canadian Corps was to take over Ghent from the 12th British Corps. Thereafter the inter-Army boundary would be adjusted to give First Canadian Army the left bank of the Scheldt as far east as the Dutch border where it crossed the river north-west of Antwerp. The directive ended by stating that the responsibility of No. 84 Group RAF was now extended to include the Dutch islands of South and North Beveland and Walcheren. “Every effort is to be made to interfere with, and destroy, the enemy now in process of ferrying himself across R Schelde to these islands.”

The absence from this directive of any direct reference to the opening of Antwerp suggests that Field-Marshal Montgomery had mentioned it either not at all or merely as a task of the distant future. This situation, however, was soon to change. At their conference at Brussels on 10 September Eisenhower seems to have impressed upon Montgomery his desire for the opening of Antwerp, although he agreed to some delay for the sake of Operation MARKET-GARDEN (above, page 312). Thereafter Antwerp assumed a rather higher official priority, at least, in the planning of the 21st Army Group.28 It is of interest also, and perhaps of some importance, that at this same moment the Combined Chiefs of Staff, meeting at Quebec, on the motion of Field-Marshal Sir Alan Brooke urged General Eisenhower to make energetic efforts to open Antwerp. Eisenhower had reported his immediate plans, which the conference record summarizes as follows: “The Supreme Commander’s first operation will be one to break the Siegfried line and seize crossings over the Rhine [MARKET-GARDEN]. In doing this his main effort will be on the left. He will then prepare logistically and otherwise

for a deep thrust into Germany.” On 12 September the Combined Chiefs agreed to send Eisenhower a telegram, drafted by Brooke, which concurred in his plans but drew his attention

“a. to the advantage of the northern line of approach into Germany, as opposed to the southern, and

“b. to the necessity for the opening up of the north-west ports, particularly Antwerp and Rotterdam, before bad weather sets in.”29

The changing emphasis was reflected in a signal from Montgomery to Crerar sent early on 12 September:30

Delighted to hear about good progress at Havre. When you have encircled [sic] concentrate everything on Boulogne. The early opening of the port of Antwerp is daily becoming of increasing importance and this cannot repeat cannot take place until Walcheren has been captured and the mouth of the river opened for navigation. Before you can do this you will obviously have to remove all enemy from the mainland in that part where they holding up [sic] north east of Bruges. Airborne army considers not possible use airborne troops in the business. Grateful for your views as to when you think you can tackle this problem. ...

The following day, in the same letter which informed Crerar of the MARKET-GARDEN plan (above, page 312) Montgomery raised the question of Antwerp in a more urgent form (below, page 336). The planning of the operations to open Antwerp can best be dealt with in the next chapter; at this point it is most appropriate to concentrate upon those directed against the Channel Ports. It should be emphasized, however, that from 12 September onward the planning for the Scheldt operations, representing a great enlargement of the tasks of First Canadian Army, complicated its operations. When on 13 September Montgomery asked Crerar whether he could capture Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais, and simultaneously set in motion operations to open the port of Antwerp, he was in fact setting him, as is now obvious, a task far beyond the limited resources of his Army.

Operation ASTONIA: The Capture of Le Havre

The first of the Channel Ports to be captured by First Canadian Army was Le Havre, which was taken by Lieut.-General Sir John Crocker’s 1st British Corps in a neat and expeditious three-day operation in the second week of September. As has been explained, the capture of Le Havre had been assigned to Crocker well before the end of August, and his leading troops came up against the city’s outer defences on 2 September. It soon became evident that the place was garrisoned and that the Germans intended to offer a strong defence; but a heavy scale of support, by air and sea as well as by land, was clearly required, and obtaining and coordinating these various resources took time. The assault could not be undertaken for over a week.

Le Havre had long been a city of much commercial and military significance and had figured prominently in the old Anglo-French wars. In modem times it had become a very important mercantile port and just before the Second World

War it ranked second only to Marseilles among French ports in terms of shipping handled. In the first week of September 1944 it was already far behind the new battlefront; nevertheless, if it could be captured quickly without serious damage to the harbour installations, the pressure on the Allied supply lines would be reduced and the momentum of the pursuit could be better maintained.

The place had considerable natural strength. It was surrounded by water on three sides: on the west by the Channel, on the east by the flooded valley of the Lézarde River, and on the south by the Seine estuary and the Canal de Tancarville. On the land side high ground at Octeville-sur-Mer overlooked the northern approaches, which were also protected by minefields and a deep anti-tank ditch. However, although the city was heavily fortified against naval attack, the landward defences were incomplete. A defensive line ran west of and roughly parallel to the Lézarde, turning west at Montivilliers to reach the coast by way of Doudenéville and Octeville; the Germans considered this latter sector the weakest part of the front. They had large artillery resources. Apart from the coastal guns, most of which could fire only to seaward, and which included one 380-mm. (14.8-inch) and two 170-mm. guns in the Grand Clos battery north of the city, there were 44 medium and field guns and 32 anti-aircraft guns. The fact that some of these were of French or Czech manufacture complicated the problem of ammunition supply.31

The fortress of Le Havre had been commanded since mid-August 1944 by Colonel Eberhard Wildermuth, not a regular soldier but an officer of wide experience. He later estimated the effective strength of his garrison as about 8000, although the total strength, as indicated by the number of prisoners finally taken, was well over 11,000. It comprised a fortress cadre unit (Festungs Stamm Abteilung); some units of the 226th and 245th Infantry Divisions; a battalion of the 5th Security Regiment; and naval elements. The defenders were hampered by the presence in the city of some 50,000 French civilians, the remnant of the peacetime population of over 160,000.32

Before the assault the defences were “softened” by a series of coordinated naval and air bombardments. The 1st Corps had been authorized to communicate directly with Bomber Command and the Navy. On 5 September HM Monitor Erebus engaged the defences with her two 15-inch guns, but the Grand Clos battery hit her and forced her to withdraw. She bombarded again on the 8th but was again hit.33 The RAF Bomber Command also began its attacks on the 5th in daylight, when 348 aircraft dropped 1880 tons on the port area and gun positions. On the night of the 6th-7th there was another attack in roughly the same strength, and on the 8th a day attack during which 109 aircraft bombed. A considerable raid attempted the next day was frustrated by the weather. All told, before the day the ground assault began Bomber Command had put down some 4000 tons of explosive on Le Havre.34

Sir John Crocker decided to launch his Corps against the northern outskirts of Le Havre immediately after a large-scale attack by Bomber Command, with the 51st (Highland) Division on the right and the 49th (West Riding) Division on the left. In the opening phase the 49th Division, with the 34th Tank Brigade

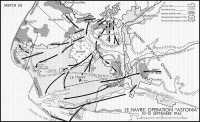

Sketch 26: Le Havre: Operation ASTONIA, 10–12 September 1944

under command, would seize the northern plateau which lies west of the Lézarde River and south-west of Montivilliers. The 51st Division, with the 33rd Armoured Brigade, would then secure a base farther west, on the northern edge of the Forêt de Montgeon, while the 49th Division pushed on south to capture another plateau looking across the Lézarde towards Harfleur. In the final stages the 51st would deal with the defences near Octeville, obtaining control of dominating ground on the northern outskirts, and, together with the 49th, would crush any remaining resistance in the city.35 ASTONIA was originally scheduled to begin on 9 September, but weather interference with the bombing programme necessitated a postponement of 24 hours on 7 September.36

Before the infantry assault the defences, particularly the battery positions, were heavily shelled. The divisional artilleries of the 1st Corps were supplemented by six medium and two heavy regiments of the 4th and 9th Army Groups, Royal Artillery. The artillery programme included counter-flak fire (known as APPLE PIE) during our bomber operations.37

The 10th of September, the Le Havre D Day, began with an attack by 65 aircraft of Bomber Command on the Grand Clos battery.38 Then Erebus renewed the naval bombardment in partnership with the battleship Warspite, their targets being “casemated guns on perimeter defences of Havre”. The Grand Clos battery came to life but this time scored no hits. “ Erebus was particularly successful being awarded 30 hits out of about 130 rounds by the spotting aircraft.”39 Warspite fired 304 rounds and is reported to have finally silenced Grand Clos. Both ships received the warm thanks of General Crocker.40

At 4:15 p.m. the main Bomber Command attack began, the first wave of aircraft dropping its load on the western defence area of Le Havre, the second bombing the northern belt of defences running west from Montivilliers. Later in the day the southern plateau was bombed. All told, 932 aircraft took part in this terrifying demonstration of Allied air power, and 4719 tons of bombs were dropped.41 Examination later indicated that the bombing had done considerable damage to batteries with open emplacements, much less to concrete positions. However, available evidence indicates that the German garrison (unlike the civilian population, unfortunately) suffered few casualties because of their deep underground shelters. Indeed, the Fortress Commandant afterwards claimed that the naval and air bombardment had “only a general destructive effect” and that the most damaging fire was the counter-battery activity of the Army artillery.42

At 5:45 p.m., immediately following the cessation of the bombing of the northern defences, the 49th Division began the ground assault. Preceded by “Flail” tanks of the 22nd Dragoons, which breached a minefield west of Montivilliers, the 56th Infantry Brigade captured the northern plateau and secured bridges over the Fontaine River (a tributary of the Lézarde) during the same night.43 These operations were greatly assisted by other specialized assault equipment, in particular “Crocodiles”, AVREs and “Kangaroos” from the 79th British Armoured Division. The “Kangaroos”, first used in Operation TOTALIZE (above, page 210), were manned at Le Havre by the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel

Carrier Squadron.*44 In the opening phase of ASTONIA they transported British infantry to the area of their objectives, thereafter assisting the troops in mopping up and exploitation. The Corps Commander later paid tribute to the “Kangaroos”, observing that they “saved many casualties from small arms and especially enemy harassing fire”.45

At midnight the 51st Division advanced on the 49th’s right or western flank and, with the help of artificial moonlight, began clearing the area north of the Forêt de Montgeon. The anti-tank ditch hampered progress forward and the evacuation of casualties to the rear.46 Nevertheless, the 51st made such good progress, reducing strongpoints and capturing prisoners, that on the morning of the 11th their divisional commander decided to carry out the third phase of ASTONIA at once, by eliminating the German gun areas west of the Forêt de Montgeon. Meanwhile, the British counter-battery programme had greatly reduced the number of German field, medium and anti-aircraft guns still capable of firing.47

Early in the morning of 11 September Bomber Command made its final attack on Le Havre, 146 aircraft dropping 742 tons of bombs on the western part of the town. In the course of the day rocket-firing Typhoons made successful attacks on strongpoints in the south-eastern sector. General Crocker signalled to Air Chief Marshal Harris thanking Bomber Command for the “absolute accuracy of bombing and timing on every occasion”.48 On this day the 49th Division captured the southern plateau, on the eastern outskirts of Le Havre, as well as an area east of the Lézarde, near Harfleur. In this latter sector the 146th Infantry Brigade had to deal with several strongpoints covering the main road into Le Havre, all well protected by minefields. The infantry suffered severe casualties from mines when they attacked; later tanks and some “Flails” were brought forward to assist and the strongpoints were finally subdued on the afternoon of 11 September.49

The stage was now set for the final act. Advancing rapidly through the eastern parts of the city, the 49th Division reached the vicinity of the old fort of Sanvic (Fort de Tourneville) by nightfall on the 11th. From the northern outskirts the 51st also forced their way in, their route blocked in places by debris from the bombing, and by evening were on the high ground at La Heve overlooking the Channel. It was evident that the enemy’s resistance was collapsing, for prisoners gave themselves up in large numbers. On the morning of the 12th Colonel Wildermuth lay wounded in the dugout of his battle headquarters. The garrison’s situation was hopeless. The 49th Division took Fort de Tourneville. British infantry and armour were closing in, the terrible artillery fire continued, and there were no German anti-tank guns left. When a squadron of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment menaced his headquarters just before noon, Wildermuth surrendered. He afterwards complimented the British troops on their “correct and gentlemanly behaviour” towards the wounded and prisoners. Throughout the

* This squadron had been organized on 28 August and was equipped with the “unfrocked Priests” used in the Falaise operations. In the following October the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment (two squadrons) was organized under the command of Lt.Col. G. M. Churchill. It was equipped with converted Canadian “Ram” tanks (“Kangaroos”). It operated as a unit of General HobartÕs 79th British Armoured Division.

remainder of the 12th sporadic fighting continued. The 51st Division captured Fort Ste Adresse and cleared the Doudenéville–Octeville area and La Hève the 49th cleared the docks and the Schneider works. The last resistance was offered by a small party on one of the quays.50

Forty-eight hours had sufficed to reduce Le Havre. The number of prisoners was reported as 11,302;51 while the casualties of the 1st British Corps for the period of the assault were (according to the best available figures) only 388.52 Much of the success of ASTONIA was undoubtedly due to the bombardment of the defences by the Royal Artillery, the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy. The Germans had offered a respectable but not a fanatical defence; a British observer wrote, “Without... a halfhearted garrison and a thorough subjugation of hostile artillery, success would have been less rapid and much more costly.”53

The enemy had carried out systematic demolitions to delay Allied use of the harbour. The job was in fact so thoroughly done that shipping could not use it until 9 October.54 SHAEF had allotted the port to the maintenance of the American armies, and this the British did not object to, since it was almost as far behind the front as the Rear Maintenance Area at Bayeux.55 What Field Marshal Montgomery now wanted was the Channel Ports, and particularly Boulogne (above, page 329). In his letter of 13 September to General Crerar,56 he wrote,

3. The things that are now very important are:

a. Capture of Boulogne and Dunkirk and Calais.

b. The setting in motion of operations designed to enable us to use the port of Antwerp.

4. Of these two things, (b) is probably the most important. ...

The same evening, Montgomery signalled Crerar, “Early use of Antwerp so urgent that I am prepared to give up operations against Calais and Dunkirk and be content with Boulogne. If we do this will it enable you to speed up the Antwerp business?”57 In his directive of 14 September (above, page 313) the Field Marshal prescribed the tasks of First Canadian Army as follows:

8. Complete the capture first of Boulogne, and then of Calais.

9. Dunkirk will be left to be dealt with later; for the present it will be merely masked.

10. The whole energies of the Army will be directed towards operations designed to enable full use to be made of the port of Antwerp. ...

Leaving the Antwerp operations aside for the moment, we must now deal with the Canadian operations against the northern Channel Ports.

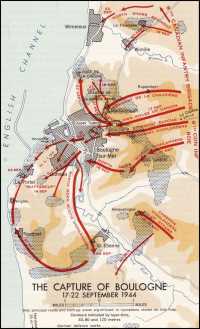

Operation WELLHIT: The Capture of Boulogne

General Spry’s 3rd Canadian Infantry Division had come up against the defences of Boulogne on 5 September and that night issued a preliminary order concerning the capture of the place (above, page 326). But the town was far too strong to be taken without a deliberate attack and heavy support; and this meant delay. It is recorded that General Simonds considered “bombers, Priests [armoured personnel carriers] and medium artillery as vital to plan”; “other

gadgets” were desirable but not so much so as to necessitate postponing the attack to wait for them.58 But Bomber Command, the armoured carriers and a great force of artillery* were all committed to the attack on Le Havre; and Boulogne could not be attacked until Le Havre fell and these resources were freed. From one fortress to the other was roughly 135 miles by road.

Boulogne was ringed on the landward side by a series of high hills which dominated all approaches. Mont Lambert on the east, in particular, rose 550 feet; and farther south the Herquelingue “feature” was almost as high. These and other positions had been heavily fortified by a resourceful enemy, for Boulogne had been on Hitler’s original list of “fortresses” (above, page 50). The garrison was under an able and experienced senior officer, Lieut.-General Ferdinand Heim, who had served in Poland as Chief of Staff to General Guderian and had risen to command a corps in Russia. Its strength (estimated by our local intelligence as between 5500 and 7000)† was actually about 10,000.59 Its quality was not especially high, the 2000 infantry consisting of a fortress machine-gun battalion and two fortress infantry battalions, all made up of low-category men. A good part of the artillery and engineer personnel of the 64th Infantry Division were present.60 As at Le Havre, the enemy was strong in artillery, the guns including coast-defence pieces up to 30.5-cm. (12-inch), of which however many could not fire landward, and at least 22 88mm. guns, plus about nine 15-cm. howitzers belonging to the 64th Division. Apart from the dual-purpose 88s there were few anti-tank guns.61 Under German orders some 8000 civilians left the city between 11 and 13 September—Canadian Civil Affairs officers making efficient arrangements for transporting, feeding and housing them.62

The attack on Boulogne, Operation WELLHIT, was to be executed in four phases. General Spry intended to launch his main assault from the east against the general area of Mont Lambert, using the 8th and 9th Infantry Brigade Groups, after a heavy preliminary bombardment by aircraft and artillery. In the second phase the two brigades would secure the centre of the built-up area and, it was hoped, seize a crossing over the Liane River before the bridges could be blown. The third phase would see the capture of outlying strongpoints at Fort de la Crèche, Outreau and Herquelingue; the fourth, the capture of Nocquet on the coast and the heights of St. Etienne.63

The preparations for aerial bombardment reflected the views of the Army Commander, who on 13 September wrote to Field-Marshal Montgomery:64

While the rapid fall of Le Havre has favourable potential influences, it is most important that the effect so gained should not be more than lost by an unsuccessful attack on the next objective, Boulogne. I, therefore, want Simonds to button things up properly, taking a little more time, if necessary, in order to ensure a decisive assault.

* Of the three Canadian medium regiments in the theatre, only one (the 7th) was immediately available to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. The 3rd, which had been refitting south of the Somme, arrived in the Boulogne area on 8 September. The 4th was supporting the Polish Armoured Division in Belgium.

† These are the figures given in a 3rd Division intelligence summary dated 13 September. On the same day, however, General Crerar, writing to Field-Marshal Montgomery, estimated the garrison more accurately at 10,000.

The bomber support was in fact the last part of the programme to be settled. A hoped-for meeting with a representative of the RAF Bomber Command did not materialize on 14 September; HQ First Canadian Army complained, “Whole affair now held up awaiting his arrival.”65 But on the 15th General Simonds, his own Chief of Staff and General Crerar’s, and the Senior Air Staff Officer of No. 84 Group, flew to Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Air Force at Versailles and duly “buttoned up” the question of air support at both Boulogne and Calais. The first discussions were not particularly satisfactory, it is true; two air vicemarshals, one of whom was from Bomber Command, were reluctant “to use more than 300-400 RAF [heavy] Bombers for each port”, counting on supplementing this effort with mediums. But when Air Chief Marshals Tedder, Harris and Leigh-Mallory arrived “for another meeting” the Corps Commander seized the opportunity and put his case to them. All three “agreed with little hesitation that if Boulogne and Calais were to be captured forthwith and air support was necessary, then it should be given in full measure”. The details were worked out at once.66 Next day General Spry announced that the WELLHIT D Day would be 17 September.67 Thus the assault on Boulogne went in on the same day as the greater operation at Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem.

During the final stage of preparation, particularly after the fall of Le Havre, the tactical air forces were directed against Boulogne. All told, there were 49 attacks, before the assault, by mediums, fighter-bombers and rocket-firing Typhoons.68 Their main targets were battery positions; these were also engaged by the gradually growing force of artillery deployed around Boulogne, but ammunition shortages prevented heavy counter-battery fire before the actual day of the assault.69 Ultimately 328 guns were used against the fortress: those of five field, seven medium, three heavy and two heavy anti-aircraft regiments.* The 9th British Army Group Royal Artillery and the divisional artillery of the 51st (Highland) Division, both of which had hurried up from Le Havre, joined with the Canadian gunners in this operation. Since this great force of artillery was supporting the 3rd Canadian Division, the responsibility for coordinating and directing the effort rested mainly upon the 3rd Division’s artillery commander, Brigadier P. A. S. Todd.70

There was potent artillery help also from across the Channel. The Brigadier Royal Artillery, First Canadian Army (Brigadier H. O. N. Brownfield) flew to England and arranged for the mammoth guns on the South Foreland east of Dover to fire on the German cross-Channel batteries in the Calais–Cape Gris Nez area, to prevent them from interfering with the attack on Boulogne. Two 14-inch guns (WINNIE and POOH) manned by the Royal Marine Siege Regiment, and two 15-inch manned by the 540th Coast Regiment RA, came into action, firing with air observation; it may be noted at once that after some preliminary shooting on the 16th they fired actively and accurately on the 17th. The German battery positions were hit repeatedly; and one of the 15-inch guns scored a direct

* The 12th Canadian Field and 3rd Canadian Medium Regiments were supporting the 7th Infantry Brigade in front of Calais, and did not fire on Boulogne. All three heavy, five of the medium and one of the HAA regiments were British.

Map 7: The Capture of Boulogne, 17–22 September 1944

hit on one of the 16-inchers of the great German Noires Mottes battery near Sangatte, the range being about 42,000 yards, or over 23 miles. The 15-inch guns fired this day until their old barrels were so worn that they could no longer reach the French coast. The 14-inch were in action again on 19 and 20 September. Both the army and marine units cooperated with enthusiasm and shot with a skill that earned the Canadians’ admiration.71

At 8:25 a.m. on 17 September the first aircraft from Bomber Command appeared over Boulogne. An officer who was watching from high ground south of the city* described the scene:72

The bombers approached us head on: suddenly huge bursts of dust and smoke plumed out on the slopes of Mount Lambert ... Over the peak of Mount Lambert appeared a tight concentration of low [artillery] air bursts, designed to keep the flak crews there below ground. ... A later wave of bombers, directed on the peak of the mount was preceded by a Pathfinder which dropped a white smoke marker. The arty seemed also to lay smoke here. A swarm of planes then materialized out of the sky as before, and once again huge clouds of smoke blotted out the shape of the hill-top.

In this single attack Bomber Command dropped 3232 tons of bombs on Boulogne. Five hundred and forty Lancasters, 212 Halifaxes and 40 Mosquitoes took part; in spite of the artillery fire directed on the flak positions, two aircraft were lost. An RAF group captain was with Brigadier Rockingham in his tactical headquarters dug in on his brigade’s start-line. He was in radio communication with the master bomber overhead, and was able to pass to him the brigadier’s confirmation that the markers put down by the pathfinder aircraft were on precisely the right points. This was “close cooperation” at its best.73

As at Le Havre, the precise results of this bombardment are a matter of discussion. General Heim claimed that “amongst personnel, casualties were almost negligible” and that there was little effect on permanent installations.74 Again British operational researchers found that only a relatively small proportion of the enemy’s guns had actually been destroyed or damaged. The extensive cratering impeded armoured vehicles supporting the ground attack.75 There is, however, ample evidence that the bombing seriously disrupted the defenders’ communications and shook their morale. (A German who had been in an underground bunker during the attacks remarked that it was “like being in the bottom of a cocktail shaker”.)76 The investigators noted that positions within the limits of the heavy bomber targets were captured much more rapidly than those outside. Moreover, the bombing certainly gave, as always, a fillip to the spirits of our own infantry which was no small factor in their success. Headquarters First Canadian Army, commenting on the researchers’ report some months later, remarked, “Despite the proved lack of material effect of ground or air bombardment on the defences, it is considered that both the RAF and the artillery bombardment were extremely effective in neutralizing the enemy defences.”77

* The completeness of our command of the air was reflected in the fact that for this operation a lookout for “spectators” was arranged on a high hill—as if for an exercise in England. General Crerar watched the bombing from his own light aircraft.

The 8th Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Blackader) attacked on the right, the 9th (Brigadier Rockingham) on the left. H Hour was 9:55 a.m.—the moment when the last bomb fell on Target 1. However, it was considered important if possible to capture the extreme northern end of the German defended area before the main attack went in; for the strongpoints about La Trésorerie and Wimille appeared to be a menace to it. A coastal battery on the hill at La Trésorerie mounted three 30.5-cm. (12-inch) guns, and though these could not fire landward there were other weapons here and the position was commanding. Accordingly The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment was to attack it at 9:25 a.m. after half an hour’s artillery preparation. The evident assumption that thirty minutes would suffice to clear the area turned out to be too optimistic. The attack was checked, after making slight progress, in minefields covered by airburst fire from light artillery. The North Shore in fact did not clear all its objectives until 19 September. Nevertheless it seems to have kept the Germans busy enough to prevent them from interfering with the main attack.78

The task of the 8th Brigade’s main body was to deal with the enemy’s defences between Mont Lambert and La Trésorerie, in the vicinity of Marlborough and St. Martin Boulogne. Immediately after the bombing Le Régiment de la Chaudière advanced against Marlborough. En route they occupied an intact radar station in the hamlet of Rupembert; and by nightfall they were consolidating in Marlborough. On the Brigade’s left (southern) flank The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada were directed against St. Martin Boulogne. By 11:00 a.m. they had captured the railway station there, and by evening they were close to the “citadel” of Boulogne. Throughout the brigade area, shellfire and minefields were the main hindrances to advance.79

While these operations were proceeding on the northern flank, the 9th Brigade assaulted the Mont Lambert feature, moving forward the moment the Bomber Command attack had ceased. Tanks of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse) led; the infantry rode into battle in Kangaroos and half-tracks which were followed by AVREs of the 87th Assault Squadron RE Flails had also been provided to clear paths through minefields; but when the attack went in the enemy’s artillery prevented this relatively vulnerable equipment from coming into action.80

On the right, along the main road from La Capelle, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders led the assault in “galloping Kangaroos under a tremendous barrage of artillery”.81 (The artillery actually fired timed programmes, prolonging the neutralizing effect of the bombing and enabling the infantry to reach their first objectives with diminished opposition.)82 When minefields stopped the Kangaroos, the Glengarrians continued on foot; they took only 45 minutes to capture their first objectives. By this time, however, the German batteries had recovered sufficiently to bring down hot fire from their commanding positions on the slopes of Mont Lambert and nearby hills. Although the shelling made movement almost impossible, men of the 18th Field Company RCE performed an outstanding feat by clearing a vital route through the mines by hand.83

Meanwhile, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders ran into heavy opposition when they attacked the main fortifications of the Mont Lambert feature. Both sides

had appreciated the importance of this dominating ground; General Heim believed that penetration in that sector “would make defence of the port impossible”. He claimed, however, that his defensive preparations here had not been completed when WELLHIT began.84 The North Nova Scotias were transported in Kangaroos as far as the minefields; thereafter their upward progress was delayed by machine gun fire from pillboxes which had survived the bombing. These were overcome with the help of AVREs and the hard ascent continued. “Towards night Crocodiles and Flails were able to come up and the area was steadily cleared.”85 By the day’s end a great part of Mont Lambert was in our hands.

Arrangements had been made for three armoured assault teams of the 31st British Tank Brigade (each composed of one troop of Flails, two troops of Crocodiles and one half troop of AVREs, together with one platoon of Canadian infantry) to drive into Boulogne, at the end of the first phase, and seize the important bridges over the Liane River in the heart of the city. The Glengarrians provided the infantry component for two of the assault teams and these reached the Liane early on the 18th only to find the bridges blown. The third team, operating with the North Nova Scotias, had a similar experience.86

Thus, at the end of the first day, a considerable wedge had been driven into the enemy’s fortifications in the Highland Brigade’s sector, while in the 8th’s good progress had been made. At the extreme north of the position the North Shore Regiment had a foothold in the La Trésorerie strongpoint. All along the line, however, the operation had gone more slowly than the forecast. A paper produced at Headquarters First Canadian Army on 15 September seems to have assumed that Boulogne would fall in one day; for it suggested that the same troops that attacked Boulogne on the 17th might be able to attack Calais on the 19th.87 This, it now appeared, was wildly sanguine.

The 18th, however, saw further solid progress. The North Shore completed the capture of the gun positions at La Trésorerie; the Chaudière pushed on to the vicinity of the Colonne de la Grande Armee (a monument to Napoleon’s preparations to invade England in 1803-5) where there was hard fighting. The Queen’s Own advanced through the northern outskirts of the city. In the 9th Brigade area the North Nova Scotias. completed the capture of Mont Lambert.88 The Glengarrians, accompanied by AVREs, reached the so-called citadel in the centre of Boulogne. This was actually the “upper town”, perched on a limestone hill overlooking the port and surrounded by high walls. It soon succumbed to a combination of modern methods of assault and story-book stratagem. A civilian showed Major J. G. Stothart, one of the company commanders, a “secret tunnel” leading to the interior and Stothart soon had a platoon in the passage.

At the same time the Churchills wheeled up, raking the ramparts with Besa [machine-gun] fire, and prepared to place petards against the portcullis. The gate was effectively blown in. At once a host of white flags waved from the walls. To add to the confusion Maj Stothart had by now appeared in the midst of the besieged fort, utterly astonishing its ‘defenders’.89

About 200 prisoners were taken, including 16 officers. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, coming up from reserve, scrambled across the Liane in the evening by using the remains of a half-demolished bridge in the middle of the

city; the 18th Field Company then set to work to improvise repairs to the bridge with timber, and had it open for light vehicles by 4:30 a.m. on the 19th.90

The capture of the upper town and the crossing of the Liane marked the end of the second phase of WELLHIT. While the 8th Brigade continued its operations to subdue the German defences north of the port, the 9th turned south to deal with equally stubborn strongpoints in the Outreau peninsula. On 19 September the HLI pressed forward here from its Liane bridgehead. The opposition was very heavy: “Murderous fire came from all directions which was heavier than the battalion has yet experienced.” It had 64 casualties and four supporting Flails were knocked out.91 The Glengarrians took up the struggle in the afternoon with the help of tanks, AVREs and Wasps. They seized the village of Outreau, after extricating themselves from a minefield, and captured many prisoners, “including perhaps thirty black Senegalese complete with fez”.92

Between Outreau and the open Channel was a hill, about 250 feet high, capped with a German battery of six 88-mm. and four 20-mm. guns.*93 This formidable position, known in the plan as BUTTERCUP, the Glengarrians assaulted on the 19th, aided by heavy artillery concentrations. “The infantry, following the fire closely, swarmed over the hill with bayonets and grenades before the last rounds had fallen. BUTTERCUP” contributed another 185 prisoners to the already bulging cages in the rear areas.94

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders completed the next phase in the Outreau peninsula with the assistance of the divisional support battalion, The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG). After containing the enemy on the southern flank during the initial operations, the Camerons had successfully assaulted the German position on top of the very high hill at Herquelingue on the night of 18–19 September. However, when the North Nova Scotias advanced on the 20th they came under fire from the lower slopes of the feature. About 400 German soldiers had remained hidden in the underground passages of Herquelingue while the Camerons occupied the casemates on the summit. Some tank fire from the Fort Garry Horse quelled the opposition and next day this large force came marching out to surrender (General Spry christened this “the bargain basement incident”). The North Nova Scotias had continued their advance to capture the village of St. Etienne, and subsequently turned north along the coast to deal with the remaining defences at Nocquet, Ningles and Le Portel.95

While the 9th Brigade was completing its tasks in the Outreau peninsula, the 8th was reducing the last German defences on the northern outskirts of Boulogne. In this area the focal points of resistance were Wimille, Fort de la Crèche and Wimereux. On 19 September the North Shore moved against Wimille; they met stubborn resistance but captured the village, together with many prisoners, the following morning. From this time the momentum of the attack slowed as some of General Heim’s best troops fought tenaciously for their last strongpoints.

Since Fort de la Crèche was strongly held the 8th Brigade screened it with smoke and attacked the town of Wimereux on the 21st. Lt.-Col. J. E. Anderson

* Examination afterwards established that one of the 88s and two of the 20s had been destroyed or damaged by the bombing; one 88 had been put out of action by our artillery.

of the North Shore was reluctant to employ heavy bombardment against a target which he knew contained many civilians. Accordingly, only one field regiment and some captured light German guns engaged the defences while the infantry gradually penetrated the eastern portion of the town. Effective close support was given by a battery of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment RCA, which silenced machine-guns in the railway station. Fortunately, the town’s main defences faced seawards and the North Shore were able to complete the capture of Wimereux on the 22nd, receiving a warm welcome from the population.96

By this time the formidable Fort de la Crèche had also fallen. This “northern anchor of the main fortifications”97 was an old French work which the Germans had modernized and greatly strengthened. When WELLHIT began, its armament included six naval guns (two 210-mm. and four 105-mm.)*98 as well as lighter field and flak pieces. The defenders’ morale was noticeably higher than that of the remainder of the garrison. On 21 September patrols of the Queen’s Own Rifles and the Chaudière probed the outer works and obtained valuable information in spite of strong reaction. On the afternoon of the same day, some 78 medium bombers of No. 2 Group RAF attacked the fort. These preliminaries proved their worth when the Queen’s Own advanced on the following morning. With the assistance of a captured German gun they quickly subdued the now disheartened garrison; Fort de la Crèche surrendered at 7:50 a.m. It was reported that some 500 prisoners were taken in this stronghold.99

Operation WELLHIT ended on the afternoon of 22 September in the Outreau peninsula. Scout cars with loudspeakers impressed the futility of further resistance on the garrison at Le Portel. There were two strongpoints here. The northern one fell first; then, just as the 9th Brigade and a squadron of the 10th Armoured Regiment were about to assault the southerly position, the enemy hoisted the white flag. General Heim surrendered to Brigadier Rockingham at 4:30 p.m. and the last fighting ceased after the German commander sent a cease-fire order to a detachment isolated on the harbour mole, which had fought a single 88-mm. gun to the bitter end.100

Six days were consumed in the operations against Boulogne at a juncture when time was very important. Apart from this the results were gratifying.† We took 9517 prisoners, including 250 wounded.101 Our own losses were calculated as 634 killed, wounded and missing.102 Those of the six infantry battalions that bore the brunt amounted to 462, the 9th Brigade’s (247) being very slightly higher than the 8th’s (215). The heaviest loss fell upon The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (97 casualties, 18 of them fatal) and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders (96 casualties, 27 fatal).103 The enemy force had been only a little smaller than that at Le Havre, and the two Canadian brigades engaged against it had lost more men than the two British divisions that took the larger city (above, page 336). In view of the strength of the ground and the defences, it was fortunate,

* Of these, two 105s were put out of action by bombing and one by artillery fire.

† The battle honour “Boulogne 1944” awarded to units concerned in this operation serves to distinguish it from “Boulogne 1544”, carried by the Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms, which was present at Henry VIII’s siege.

as an observer said, that the enemy’s will to fight was not stronger. His troops frequently went on firing until our infantry were close to their pillboxes and gun positions, and then gave themselves up, in many cases having their kit packed ready to surrender.104

It was the German artillery that caused most of our losses, and it is evident that the neutralization of enemy batteries was less effective than at Le Havre. The reason may lie in part in the smaller effort made by Bomber Command, in the absence of naval bombardment (the reason for which was presumably the presence of extremely powerful German coastal batteries in the Pas de Calais), and in the fact that ammunition stringency prevented a really heavy artillery counter-battery programme being undertaken before the actual day of the assault (above, page 338). A Canadian artillery commentary on the first day’s fighting attributed the failure to silence some batteries partly to the lightness of the concentrations used, “seldom more than 2 [guns] to 1”, and partly to the exceptionally strong construction of the enemy gun positions.105 Operational researchers estimated in one case, that of a battery of six 88-mm. guns at Honriville south of the harbour, that our artillery put down 5700 rounds on it within a circle 300 yards in diameter, but the battery nevertheless continued in action and fired some 2000 rounds. The same investigators found deficiencies in our artillery Intelligence; our hostile battery lists before the operation contained some dummy positions, on which bombs and shells were wasted, while some actual batteries were omitted.106 Eight previously unknown batteries were reported in action on 17 September.107

Boulogne had offered the hope of a considerable improvement in the Allies’ administrative situation. Though not a major harbour, it had a total seaborne cargo movement, inward and outward, of over 1,000,000 tons in 1937 and was considered “the first fishing port of France”. Unfortunately, however, the harbour installations had been extensively damaged by the enemy’s demolitions and by bombing during the attack or earlier. Several ships had been sunk across the harbour mouth, most of the cranes had been destroyed and the locks damaged. Consequently, the port could not be used until 12 October, and there was no immediate alleviation of the Allied supply problem.108

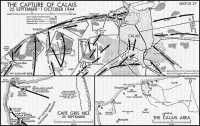

Operation UNDERGO: The Capture of Calais

Calais was next. The port was smaller than Boulogne’s and therefore less important in logistical potential. But the opinion of the Naval Liaison Officer at Army Headquarters (Commander R. M. Prior) was that if Boulogne was to be used with an acceptable degree of risk “the seven heavy Calais batteries must be captured as well as those at Gris Nez”; Captain A. F. Pugsley, RN, who now took command of the offshore naval units operating in the area of First Canadian Army, concurred, and so apparently did Admiral Ramsay.109 The situation was complicated by the preparations then being made to carry out First Canadian Army’s great task of opening the Scheldt Estuary. On 15 September,

when giving preliminary consideration to that task, General Crerar had written to Field-Marshal Montgomery:110

If, subsequent to the capture of Boulogne, Simonds finds it possible quickly to exploit that success and to capture Calais, this will be done by 2 Cdn Corps. If, on the other hand, the Garrison of Calais shows indications of resisting anything but a heavy and prepared assault, then I shall move 1 Brit Corps, less 51 (H) Division to that area and Crocker will relieve Simonds of the responsibility for the capture of Calais and the containing of Dunkirk.

It was soon apparent that Calais could not be captured without a deliberate assault. However, the urgency of the forthcoming Scheldt operations dictated a change in General Crerar’s arrangements; on the 19th the Army Commander directed the 1st Corps to take over the Antwerp sector while General Simonds prepared to deal with Calais and the batteries on Cape Gris Nez.111

General Spry’s 3rd Canadian Division, already on the ground, naturally received these latter tasks, and its staff produced their first plan for the operation (UNDERGO) the day before the attack began at Boulogne.112 It was then thought, as we have noted, that UNDERGO might begin as early as 19 September; but the protracted fighting at Boulogne led to successive postponements, since the special armour, the artillery and even the infantry needed for Calais were engaged there. Furthermore, there was a possibility that the naval requirements at Boulogne, already mentioned, might be satisfied if the army captured the Cape Gris Nez guns and merely contained Calais. As late as 23 September, the Army Commander believed that a decision to contain might have to be made after the operation began. The argument in favour of merely masking the place was, of course, based on the urgent need to expedite the clearing of the Scheldt Estuary.113

While the remainder of the 3rd Division had been preparing for the siege of. Boulogne, the 7th Infantry Brigade (Brigadier J. G. Spragge) and the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment invested Calais and Cape Gris Nez. Initially, the task was boldly performed by the reconnaissance regiment, which reached the Calais area on 5 September and proceeded to isolate the fortress, occupying a front of more than 20 miles to do so.114 On the 10th The Toronto Scottish Regiment (MG)*115 of the 2nd Division took over the southeastern perimeter from Oye to Ardres. Meanwhile, the 7th Brigade, as already described, occupied high ground about seven miles south-west of Calais on 6 September, cutting off Boulogne from Calais and threatening the Gris Nez batteries. During the next ten days these troops gradually advanced their positions and partially cleared Cape Gris Nez.116

On the night of 16-17 September the 7th Brigade, less one battalion (for the 1st Canadian Scottish were in divisional reserve for the Boulogne operation) made an attempt to capture the three heavily fortified batteries on the Cape. The 6th Armoured Regiment, the 12th Field Regiment RCA and a battery of the 3rd Medium Regiment RCA were in support. The result was merely to demonstrate that heavier support was necessary to take these positions. The attack made no impression, and an attempt by The Royal Winnipeg Rifles to bluff the

* This unit came under General Spry’s command on 19 September, returning to the 2nd Division on the 23rd.

commander of the Haringzelles battery into surrender by a threat to “blow him off the face of the earth” made no more. On the 18th the task of containing Cape Gris Nez was handed over to the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment, while the 7th Brigade prepared for its share in the attack on Calais.117

The defences of Calais were of some strength but, unlike those of Boulogne, they did not depend on a fringe of outlying hills. Canals surrounded the landward side of the city—itself described as “a series of islands culminating in the CITADEL, the heart of the old city”118—with marshy ground and inundated areas forming further barriers to penetration from the south and east. To one observer the flooded ground looked like “a vast lake”.119 A firm ridge, almost like a causeway, carried the road and railway east to Gravelines; but this ridge had been fortified and could be easily defended by a resolute enemy.

The city retained much of its old fortifications, including a bastioned wall and a wet ditch covering most of the built-up area. Here again, however, the modern defences developed during more than four years of German occupation faced mainly seaward. According to Lt.-Col. Ludwig Schroeder, commandant of the garrison, no attempt had been made to deal with the problems of landward defence until about mid-August 1944.120 Calais had only recently been designated by Hitler as the equivalent of one of his “fortresses” (above, page 301). Nevertheless, the enemy’s works in the area were impressive. At and about Noires Mottes, some five miles south-west of Calais, a battery of three 406-mm. (15.8-inch) guns, a lesser cross-Channel battery and a system of concrete pillboxes blocked the coastal route to the city. Eastward from Noires Mottes, along the Belle Vue ridge, machine-gun positions and concrete shelters protected railway guns. Between these positions and the inundated area south of Calais the Germans had constructed a formidable strongpoint on higher ground north of Vieux Coquelles. Here a wide variety of weapons, amply protected by wire and mines, lay astride the main road from Boulogne to Calais, The eastern and south-eastern approaches were similarly defended by minefields and infantry positions supported by field, anti-aircraft and antitank artillery. Finally, in the Les Baraques area on the north-western outskirts of the port, coastal installations were shielded by still more minefields and an anti-tank ditch connecting the inundated areas to the sea.121

Our Intelligence originally estimated the strength of the garrison as between 4450 and 5550, later raising the figures to “six to eight thousand”. The actual total was evidently somewhat over 7500.122 These troops were a “mixed bag” of very indifferent quality—Schroeder described them, somewhat unkindly, as “mere rubbish”—and only 2500 were available as infantry. Nearly two-thirds of the remainder were needed to man the coastal guns and port installations. The garrison’s morale, following the reduction of Le Havre and Boulogne, was under standably low. A report based on later interrogation of prisoners123 noted that

Army personnel were old, ill, and lacked both the will to fight and to resist interrogation; naval personnel were old and were not adjusted to land warfare; only the air force AA gunners showed any sign of good morale-and were also the only youthful element of the whole garrison.

Sketch 27: The Capture of Calais, 25 September–1 October 1944

The plan for the capture of Calais followed the familiar pattern of preliminary bombardment by heavy bombers and artillery, followed by a heavily-supported infantry assault. At Versailles on 15 September General Simonds had obtained RAF approval for the use of heavy bombers against Calais as well as Boulogne (above, page 338). Subsequently, Bomber Command agreed to attack five main areas, including the Sangatte–Belle Vue ridge positions, the Vieux Coquelles area and coastal fortifications as well as the north-western defences of the port proper, and the citadel.124 The artillery bombardment was to be fired by the same units employed against Boulogne, including the field regiments of the 51st Division. Detailed preparations were made for counter-battery and counter-flak programmes in the preliminary phase; these were to be supplemented, when the ground assault went in, by heavy concentrations on local points of resistance.125 A feature of the operation was the use of a smoke-screen, 3000 yards long, to hide a number of artillery units from observation from the German positions on Cape Gris Nez.126

General Spry planned to attack Calais with the 7th and 8th Infantry Brigades, assisted by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. Apart from the artillery, these formations would be supported by Flails, AVREs and Crocodiles of the 31st British Tank Brigade and Kangaroos of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron. The 7th Brigade’s task was to “capture or destroy” the garrisons of Belle Vue, Coquelles and Calais itself, while the 8th Brigade dealt with the positions at Escalles, near Cape Blanc Nez, and Noires Mottes.* (Meanwhile, the 9th Brigade would relieve the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment at Cape Gris Nez and prepare to capture the batteries there.) The infantry attack would begin when the last bomb fell on the targets nearest our troops. After successive postponements, D Day was finally set on 24 September as the following day.127

The air support programme produced one curious incident. Headquarters 2nd Canadian Corps, “cutting a comer” in a manner which disregarded both Army and RAF “channels”, made a direct request to Bomber Command for a heavy attack on the Escalles area. The helpful Harris agreed. Army Headquarters, when it heard of the proposal, was alarmed lest this should vitiate the goodwill which had been carefully built up with the air headquarters that had been by-passed—particularly HQ Allied Expeditionary Air Force and HQ 2nd Tactical Air Force. Accordingly it hastily made a request in proper form, through HQ No. 84 Group RAF, for the same attack on Escalles that Corps had asked for. AEAF nevertheless decided to cancel the attack. They did not succeed in doing so, but in the attempt (the 2nd TAF later stated) they “made a mistake”, with the result that an attack by mediums of No. 2 Group, planned to go in on Fort de la Crèche at Boulogne on the evening of 20 September, was cancelled instead. This was done by a direct order to the Group from AEAF, who thus cut a corner themselves. But the Bomber Command attack on Escalles was duly made that afternoon; 633 aircraft attacked, 3372 tons were dropped, and

* The 3rd Division’s operation order, issued on the evening of 22 September, assigns only Escalles to the 8th Brigade, but by the time the Brigade’s own order was issued on the 23rd Noires Mottes had been added to its tasks.

the results were reported on all sides as excellent.128 If this was impropriety, it was at least on a magnificent scale.

Bad weather prevented further attacks until the late afternoon of 24 September, when 188 aircraft of Bomber Command attacked targets in Calais. Unfortunately eight of them were lost.129 According to the diarist of the 7th Infantry Brigade, this was caused by a report being received that the attack had been cancelled, which led to no artillery programme being in readiness to shell the enemy antiaircraft positions.*130 The entry is poignant:

We felt very helpless watching this attack—the casualties to aircraft could have been lowered if someone along the lines somewhere hadn’t messed things up. However one has to expect this sort of thing in war. Patrols were sent out from battalions to try to pick up some of the bomber crews—those we did find were dead.131

The weather interfered with the main Bomber Command attack beginning at 8:15 a.m. on the Calais D Day itself. Nearly 900 bombers took to the air, but the majority of sorties “were abortive”; only 303 aircraft attacked, dropping 1321 tons.132 Headquarters 2nd Corps signalled Bomber Command, “Bombs which were delivered were well timed and on targets.”133 But as usual many pillboxes and other defences survived the battering from the air (and the supporting artillery) and caused trouble during the assault. In general, the results of the preliminary bombardment at Calais were similar to those at Le Havre and Boulogne: damage was done to the enemy’s defences and his morale suffered appreciably; but there was no overall smothering of resistance, and the attacking troops had heavy fighting before the port was captured.

At 10:15 a.m. on 25 September, immediately following the aerial bombardment, the 3rd Division’s veterans advanced against the western defences of Calais.134 On the left, the 8th Brigade assaulted the defences on Cape Blanc Nez and the battery at Noires Mottes. By the evening of the same day the Chaudière had captured the German garrison at Blanc Nez, numbering nearly 200. (The regimental history records that most of them were found dead drunk.)135 Meanwhile, the North Shore attacked “Battery Lindemann”, the Noires Mottes battery. Flails beat lanes through minefields protecting the gun areas, and tanks of the 10th Armoured Regiment gave covering fire. By the end of the day the North Shore occupied positions overlooking one of the huge emplacements and, in spite of continuing fighting, “negotiations” went on throughout the night for the garrison’s surrender. The German commander eventually gave in early on the 26th and at noon the enemy came filing out of their positions, the North Shore thus adding 285 prisoners to the brigade’s total. This surrender seems to have covered both the Noires Mottes position with its three great guns, and the lesser coastal battery at Sangatte on the coast nearby.136

The good progress made by the 8th Brigade in the early stages on the high ground in the Escalles-Sangatte area greatly assisted the 7th in its attack on the Belle Vue and Coquelles defences, which this ground commanded. In this sector, the assaulting battalions reported that the preliminary heavy bombing had missed,