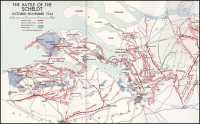

Chapter 16: The Battle of the Scheldt, September–November 1944, Part II: Breskens, South Beveland, Walcheren

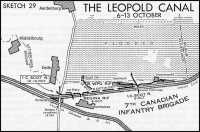

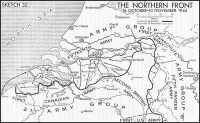

(See Map 8 and Sketches 29, 30, 31 and 32)

Operation SWITCHBACK: Clearing the Breskens Pocket

We must now revert to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division south of the Scheldt. The attack upon the Breskens Pocket, called by the Germans at the time “Scheldt Fortress South”, produced fighting quite as fierce and costly as that around Woensdrecht, and this, as the reader knows, is saying a great deal.

It has already been made clear that the terrain was difficult. The only part of the 64th German Division’s front where there was not a deep water barrier was in the vicinity of the Isabella Polder at the south-west angle of the Braakman Inlet; here there was a well-fortified gap between the eastern terminus of the Leopold Canal at the international boundary and the inlet. The 4th Canadian Armoured Division had been striving without success to get through it. The Algonquin Regiment made its first attempt on 22 September. It was repulsed, an entire platoon being lost. Further efforts thereafter had no better fortune. The enemy held this area in strength. On 5 October the Algonquins made a large-scale attack which was beaten off “with heavy fire of all kinds”. This was intended to divert the enemy’s attention from the 3rd Division’s attack across the Leopold Canal planned for the following morning; it may well have served a good purpose, though the available German records throw no light on the matter.1

The Leopold Canal front itself was unpromising. As we have seen, the entire western half of the Pocket was covered by the two canals, the Leopold and the Canal de Derivation de la Lys, running side by side, as well as by heavy inundations. It was very undesirable to attack here, the double canal obstacle in itself being extremely formidable. The operation therefore had to be launched east of the point where the canals separated, the area between them having been occupied by the 4th Division. But there too inundations almost all along the front made the problem extremely difficult. The best place available, and it was not a good one, seemed to be immediately east of the divergence of the two canals. Here there was a narrow strip of dry ground beyond the Leopold-a long triangle

with its base on the Aldegem–Aardenburg road and its apex near the village of Moershoofd some three miles east. It was only a few hundred yards broad even at its base. Its northern boundary coincided with the border between Belgium and the Netherlands.2

The 3rd Canadian Division had little time to prepare for this new operation. On 1 October the Canadian Scottish and The Regina Rifle Regiment finished mopping up the defenders of Calais. Early on 6 October, having moved up some 90 miles, they assaulted across the Leopold Canal.

The division’s plan3 proposed to combine an initial assault on the Leopold with a subsequent waterborne attack against the rear of the pocket from the vicinity of Terneuzen, in the area cleared earlier by the Polish armour. The intention was that the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade would assault here across the Braakman, in amphibious vehicles, two days after the frontal attack on the Leopold. The Leopold attack was to be carried out by the 7th Infantry Brigade with the North Shore Regiment (from the 8th) under command. The initial assault was to be made by two battalions, the 1st Canadian Scottish Regiment on the right and The Regina Rifle Regiment on the left, each with two companies up. The infantry were to cross the canal in assault boats (see above, page 316). Since very heavy opposition was to be expected, the expedient was adopted of massing “Wasp” flamethrowers to sear the north bank of the canal (which was somewhat less than 100 feet wide) immediately before the crossing. The attack was timed for first light on 6 October. The 8th Brigade was subsequently to pass through the 7th’s bridgehead.

A large force of artillery, including the 2nd Canadian and 9th British Army Groups Royal Artillery and the guns of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division as well as the 3rd Division’s own, was available to back the operation. Two Canadian field regiments (the 15th and 19th) and the 10th Medium Regiment RA were placed south-west of Terneuzen to support the 9th Brigade in its attack across the Braakman. The general principle was, “The maximum amount of artillery that can bear will support each operation in turn.” Along the whole divisional front a total of 327 guns of all calibres would be deployed. The Commander Corps Royal Artillery, 2nd Canadian Corps (Brigadier A. B. Matthews) coordinated the fire requirements.4 But in the hope of achieving surprise in the first attack preliminary bombardment was wisely omitted from the plan.

The Attack Across the Leopold Canal

At about 5:30 on the cold morning of 6 October, 27 Wasps went into action along the 7th Brigade front east of Strooibrug. As the first bursts of flame shot across the water, the assault companies picked up the boats, clambered over the steep poplar-lined bank and launched them. The flame did its work, temporarily demoralizing those of the enemy whom it did not kill. On the right, both companies of the Canadian Scottish crossed successfully near Oosthoek without coming under

Sketch 29: The Leopold Canal, 6–13 October 1944

fire. To the west, north of Moerhuizen, the Reginas’ left company likewise got across before the Germans recovered. This company was in fact the First Canadian Army Headquarters Defence Company (Royal Montreal Regiment), which had lately exchanged duties with B Company of the Reginas in order to gain battle experience. The right company of the Reginas, however, got into difficulties (one version is that it “hesitated” for a moment)5 and the enemy had time to reoccupy his positions and bring down machine-gun fire which made the open strip of water quite impassable. Eventually this company, and the Reginas’ other two rifle companies, had to be ferried over on the left.

We now had two separate narrow bridgeheads on the north bank. Though the enemy seems to have had no advance warning of the attack, his reaction was violent. He poured in mortar, machine-gun and small arms fire from the front and flanks, and immediately began to counter-attack. Rifleman S. J. Letendre of the Reginas took command of his section “without hesitation and without orders” when the section leader was killed in one of these attacks, reorganized it and set an example of initiative and fighting spirit that made an important contribution to preserving the position and won Letendre the DCM By afternoon only a handful of the Royal Montreal Regiment company survived. It was impossible to link up the two precarious footholds. However, the Canadian Scottish on the right, where there was slightly more freedom of movement than on the left, established themselves in Moershoofd. A kapok foot-bridge had been put across the canal in their area by the 16th Field Company RCE, and after an initial failure another was made good on the Reginas’ front that evening. The bridgeheads, though desperately constricted, held in spite of all the enemy

could do, and Brigadier Spragge decided to pass The Royal Winnipeg Rifles across on the Scottish front during the night of the 6th–7th. This was duly done.6

The situation in the bridgeheads almost defies description. In places they were little deeper than the canal bank. The ground was waterlogged; slit trenches rapidly filled with water, and except in the bank they could be only a foot or so in depth. With the whole area drenched with fire, which included heavy shells from coastal batteries in the Cadzand area far to the north,7 coordinated action even on the platoon level was next to impossible. The counter-attacking enemy suffered numerous casualties, but so did our own troops.8 Air and artillery support did not break the deadlock. On 12 October the Regina diarist wrote retrospectively,

Medical Officer advises us there have been between 250 and 300 casualties go through regimental aid post since 6 Oct, which is a grim reminder that this operation has been no push-over. It is the opinion that the past few days have seen some of the fiercest fighting since D Day. Lobbing grenades at enemy 10 yards away and continued attempts at infiltration have kept everyone on the jump. Ammunition has been used up in unbelievable quantities, men throwing as many as 25 grenades each a night. Artillery laid 2000 shells on our own front alone in 90 minutes on the evening of 10 Oct and our own Mortar Platoon expended 1064 rounds of HE in 3 hours. But we feel it has turned the trick. We have been able to cut enemy’s ammunition route out of Eede and prisoners of war have that lean and hungry look.

Only in the early hours of 9 October did The Royal Winnipeg Rifles succeed in closing the gap between the two bridgeheads. Since the main road running north to Aardenburg was our obvious axis of advance, it was decided to push the entire brigade to the left, narrowing but deepening the bridgehead and providing cover for bridging operations on the line of the road. By early morning of 12 October, the Canadian Scottish had succeeded in pushing one company through the Reginas to a position astride the road. The Winnipegs had troops in the hamlet of Graaf Jan on the north edge of the dry area, and the Scottish on the 13th gained a foothold in the south end of Eede. That evening the 8th and 9th Field Squadrons RCE (of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division) finished bridging the canals at Strooibrug. Next day the British Columbia Regiment had tanks in the bridgehead.9 By this time the attack of the 9th Brigade against the rear of the German pocket was making its effect felt, and the worst was over. It had been an exhausting ordeal for the 7th Brigade. In seven days’ fighting, through 12 October, the three battalions had had a total of 533 casualties. Of these 111 were fatal. The Regina Rifle Regiment had suffered by far the most heavily; including the company attached from the Royal Montreal Regiment, it had 280 casualties, 51 men losing their lives.10

The Assault Across the Braakman

Operation SWITCHBACK took a course rather different from what had been expected. It seems evident that the 7th Brigade’s effort was originally considered the main one, and we have seen that the 8th was to go in in support of it. But in the light of the opposition encountered on the Leopold Canal the attack by

Brigadier Rockingham’s 9th Brigade from Terneuzen assumed a particular importance.

The 9th Brigade’s amphibious operation was to be conducted with the aid of “Terrapins” and “Buffaloes” (Landing Vehicles, Tracked)—amphibious vehicles manned by the 5th Assault Regiment RE, a unit of the endlessly useful 79th British Armoured Division. The plan was to “marry up” the infantry and the Buffaloes in the Ghent area, then swim the brigade in the vehicles up the Ghent–Terneuzen Canal to Terneuzen and thence on across the mouth of the Braakman inlet to land east of Hoofdplaat, in the rear of the German pocket, in the early morning of 8 October. But this was one of those cases where plans are defeated by circumstances. The battalions duly embarked near Ghent on the evening of 7 October, but unforeseen difficulties arose. Passing the Buffaloes through the locks at Sas van Gent proved arduous (they would not steer at slow speed), and then at Terneuzen itself it was found necessary to construct ramps and climb the Buffaloes out of the canal around damaged locks. This took time; some of the vehicles were injured; and there was no choice but to postpone the operation for 24 hours. This was unfortunate, both because of the strained situation on the Leopold Canal and the danger of loss of surprise; but the high canal banks shielded the Buffaloes from ground observation, all practicable security precautions were taken, and in the event no warning reached the Germans.11

The actual landing took place, then, in the early hours of 9 October. Soon after midnight the Buffaloes left the mouth of the canal at Terneuzen and sailed westward, led by a motorboat carrying Lieut.-Commander R. D. Franks, RN, Naval Liaison Officer at

HQ First Canadian Army, who had volunteered to act as navigator and guide. There were two columns, each of 48 vehicles, one carrying The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, who were to touch down on “GREEN Beach”, a couple of miles east of Hoofdplaat, the other, carrying The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, being directed upon “AMBER Beach”, closer to the Braakman. The landing was set for 2:00 a.m. The beaches were marked, 15 minutes before this time, by coloured marker shells fired by our artillery, which then proceeded to fire other markers at other points to mislead the enemy. At five minutes to two the beaches were again marked. The leading craft actually touched down about five minutes late. The enemy had been taken by surprise. There was no opposition, except a few shots in the HLI of C. area; and shelling from the German coastal batteries at Flushing, across the West Scheldt, did not begin till dawn.12

In these fortunate circumstances, the bridgehead was soon firm. A smokescreen was laid down with floats to protect the movement of craft from the German gunners, and by 9:30 a.m. the reserve battalion, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, was ashore, accompanied by heavy mortars and machine-guns of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG). The SD and G. directed their advance on Hoofdplaat, while the other battalions pressed southward.13 The Germans were now recovering from their surprise and reacting with characteristic vigour, and shelling from Breskens and Flushing was troublesome. Opposition was heaviest on the front of the Highland Light Infantry, moving

against Biervliet. General Eberding had rapidly committed his divisional reserve against the new menace, and although he later described the reserve as composed of odds and ends14 it fought well. It is of interest that “the prevailing mist” allowed the Germans to ferry two companies of the 70th Division across the Scheldt from Walcheren to reinforce the 64th in this crisis.15 Our advance was slow. The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry captured Hoofdplaat on 10 October. Biervliet did not fall until the evening of the 11th, after the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment, the first reinforcement sent into the bridgehead, had relieved The Highland Infantry of Canada in the line and enabled it to mount an attack against the village.16

By now, General Spry had altered his basic plan as the result of the stalemate on the Leopold and the better progress made on the 9th Brigade’s front. It had not been practicable to use the 8th Infantry Brigade on the Leopold as originally intended. On 9 October, orders were issued to this brigade to prepare for an attack by land through the Isabella area to link up with the 9th Brigade. On the 10th, however, the plan was changed again. Another attempt by The Algonquin Regiment to break through at Isabella, to open a route for the 8th Brigade, failed. The 9th Brigade’s bridgehead was over-extended and there was a gap between the HLI in Biervliet and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders on their right. The decision was now taken to land the 8th Brigade in the rear of the new bridge head.17 Its leading battalion, The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment, landed in the bridgehead on 11 October, coming under the 9th Brigade in the first instance. The following day the 8th Brigade was complete in the area and took over the left flank.18

The Germans were still battling fiercely, and their artillery fire was particularly effective. But the 64th Infantry Division was now under severe strain, and the break was about to come. On 14 October the 10th Infantry Brigade’s long and unpleasant vigil along the Leopold Canal was finally rewarded. On 9-10 October patrols which The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada sent across the canal south of Watervliet had met as fierce opposition as the Algonquins encountered at Isabella. Now it was found that in both these areas the enemy was withdrawing, and the Algonquins and Argylls pushed forward accordingly. During the day Algonquin patrols made contact near the south-western angle of the Braakman with patrols of The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada coming down from the north.19 The eastern end had been sliced off the German pocket, and it was now possible to open a land supply route through the Isabella sector and dispense with the ferry service that had been operating from Terneuzen.

The enemy was still holding hard in front of the 7th Brigade north of Strooibrug, and tough resistance was encountered here after Eede was found to be empty and was occupied on 16 October. But our troops’ advance from the direction of the Braakman was bound to loosen the pressure on the Eede front. The 52nd (Lowland) Division (above, page 388) was now becoming available for action, and at last light on 18 October its 157th Infantry Brigade, having come under command of the 3rd Canadian Division, began to relieve the tired 7th

Brigade in the Leopold bridgehead.* On 19 October the 157th occupied Aardenburg and Middelbourg without opposition. The same day the 7th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment made contact with troops of the British brigade at Aardenburg.20 The enemy had now fallen back to a secondary defence line. With its left resting on Breskens, it ran thence through Schoondijke and Oostburg to Sluis, whence it followed the Sluis Canal to the Leopold. The 64th Division had lost many men—the 3rd Canadian Division had so far captured over 3000 prisoners21—but the Germans were now holding a shortened line and trouble was still to be expected.

General Spry’s plan for breaking the new line22 comprehended, first, the capture of Breskens and Schoondijke by the 9th Brigade. Thereafter the 7th Brigade, having had a short rest after its efforts on the Leopold, would pass through the 9th to clear the whole coastal area north-east of Cadzand. Simultaneously with this operation by the 7th Brigade, the 8th would capture Oostburg, Sluis and Cadzand and then clear up what remained of the German pocket between the Leopold Canal and the coast. The plan was to make considerable use of the special armour of the 79th Armoured Division, although it was realized that the terrain would interfere considerably with its employment. Unfortunately, however, the accidental explosion in Ijzendijke on 20 October of a vehicle carrying flamethrower fuel destroyed some ten armoured vehicles and caused 84 casualties.23 Thus for the moment the role of the special armour was further curtailed.

On 21 October the assault on the new German line began when The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders attacked the defences of the little port town of Breskens. The weather was clear that morning, and air support was on a large scale. There was a heavy air blow at the Flushing batteries, and Typhoons “were used to good effect throughout the attack”. By noon the town was clear, and patrols were pushing on in the direction of Fort Frederik Hendrik beyond. Next day The Highland Light Infantry of Canada attacked Schoondijke and met heavy opposition; the town was not finally cleared until the 24th.24

In the meantime preparations were made for the all-out assault on Fort Frederik Hendrik. Not much remained of this ancient work except its two lines of water defences, but inside them the Germans had built new concrete fortifications.25 The position looked like a hard nut to crack; two companies of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders were beaten back from it on the 22nd, and plans were then made to attack it on 25 October after bombardment by artillery and medium bombers. But on the night of the 24th–25th a deserter from the fort reported that only 23 Germans remained there. He was sent back to threaten them with destruction if they did not come out, which they proceeded to do. The North Nova Scotias occupied the fort and took some additional prisoners. The 9th Brigade had now completed its share in the operation and was withdrawn to rest.26 It was hoped that its temporary disappearance would trouble the enemy, who would be uncertain where it would appear next; and in fact it did have this effect.27

* The 52nd Division was commanded by Major-General E. Hakewill Smith. It had been specially trained for mountain warfare, and was now to fight its first battle in terrain which was largely below sea level.

General Eberding had hoped to use Oostburg as a pivot on which to swing his left flank back to a system of concentric dykes centring on Cadzand; and General Spry had divined this intention. But Eberding’s plan was disturbed by the speed with which the 7th Brigade now moved forward into the coastal area beyond Fort Frederik Hendrik.28 On 24 October the Germans asked through one of their medical officers that Groede, which contained many civilians and a hospital full of wounded, should be treated as an open town; and since it did not appear to be defended this was agreed to. The 7th Brigade advanced on either side of Groede. We hoped to outflank Cadzand by a thrust along the coast, thereby capturing the. enemy’s divisional headquarters which was believed to be in the town. In attempting to effect this on 27 October the Canadian Scottish Regiment met a strong counter-attack which overran their leading company. The Germans reported that the main factor in this local success had been the accurate fire of the Walcheren batteries. But they then pulled out of Cadzand, which we occupied on the 29th.29

In the meantime the 8th Brigade had been pushing in on the left.*30 The advance towards Oostburg was slow. “The ground throughout the area was saturated and movement restricted to roads on which the enemy had established numerous strongpoints.”31 Oostburg was finally taken by the Queen’s Own on 26 October. On the 29th enemy resistance lessened along the line in a manner suggesting another general withdrawal. Le Régiment de la Chaudière captured Zuidzande that day.32 The enemy was in fact pulling back over the Uitwaterings Canal, beyond the old fortified position of Retranchement. He was now penned in the last comer of his pocket.

On 30 October the 7th Brigade, advancing along the coast, found the enemy still in possession of well-fortified coastal batteries immediately north-west of Cadzand, and reducing these occupied it for the next three days. As late as the 27th, at least, the Germans had been supplying these positions with ammunition, and evacuating casualties from this area to Flushing, by sea; on that date 400 casualties reached Flushing safely.33 But they were unable to evacuate their prisoners taken on the 27th; the Canadian Scottish got 35 of their missing comrades back on 2 November.34 By the evening of 30 October the 8th Brigade had troops across the canal north of Sluis, and that night the 9th again moved into action. The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders and The Highland Light Infantry of Canada formed a bridgehead at Retranchement, and merely postponed their advance until the canal could be bridged behind them. As soon as this was accomplished the brigade pressed forward. On 1 November the HLI of C. cleared “Little Tobruk”, a formidable strongpoint just east of Knocke-sur-Mer. Corporal N. E. Tuttle worked under fire for twenty minutes or more, cutting a gap through the German wire; he then led his platoon through it to the assault, winning the DCM The same day The North Nova Scotia Highlanders captured General

* General brigade was now commanded temporarily by Lt.-Col. P. C. Klaehn of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa. Brigadier Blackader had had to go into hospital in September. Lt.-Col. C. Lewis of the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars, who had been acting as Brigade Commander, was killed on 17 October while on his way to visit one of the battalions. On 29 October Lt: Col. J. A. Roberts, formerly commanding the 12th Manitoba Dragoons, took over the brigade and was subsequently promoted Brigadier.

Eberding at Het Zoute nearby; the North Shore Regiment took Sluis, with its ancient fortifications; and the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment RCA, fighting as infantry, crossed the Sluis Canal at its junction with the Leopold and cleared the north bank.35

Operation SWITCHBACK was virtually brought to completion on 2 November. The 9th Brigade had cleared the area of Knocke and Heyst; the 7th had ended the resistance in the coastal strongpoints near Cadzand; and the 8th had cleaned up the last enemy in the flooded area south of Knocke. The 7th Reconnaissance Regiment, which had latterly taken over the task of containing the enemy’s western flank, found no enemy in Zeebrugge or between the Bruges Ship Canal and the Leopold on the morning of 3 November. At 9:50 a.m. that day the entry was made in the operations log at Headquarters 3rd Division, “Op SWITCHBACK now complete”; and somebody wrote beside it, “Thank God!”36

It had been, to put it mildly, an unusually demanding operation. The polder country where it took place is said to have been described by a Belgian military manual as “generalement impropre aux operations militaires”.37 In this opinion the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division would certainly have warmly concurred. The enemy had fought with determination and skill, making the most of the difficulties imposed upon us by the terrain; a First Canadian Army intelligence summary issued on 7 November called the 64th “the best infantry division we have met”. The numerous heavy guns in the Atlantic Wall coast defences, particularly strong in this area, gave it powerful support. During the operation the 3rd Division captured 12,707 prisoners.38 Many Germans had been killed, and as we have seen some hundreds of wounded had been evacuated from the Pocket. The 3rd Division’s own casualties as computed at the time had numbered 2077, of which 314 were known to have been fatal. Of the 231 then “missing”, most had certainly lost their lives.39

The battlefield had been very unsuitable for armour, and tanks had therefore played only a limited part, though when they could come into action they were most helpful. The artillery, on the other hand, had been constantly active and invaluable; linear and pinpoint concentrations, brought down on call, had been used to particular advantage.40 Air support, when the weather permitted, was heavy and excellent; it was calculated that 1733 fighter sorties and 508 medium and heavy sorties were flown on behalf of the division during the operation.41 The engineers, as we have seen, had played an important part. All arms and services, indeed, deserved large credit. But the circumstances of the battle had placed the main burden throughout upon the infantry soldier.

Before the Breskens pocket was finally liquidated, British forces were already ashore on Walcheren Island north of the West Scheldt. However, the capture of Breskens and Fort Frederik Hendrik on 21-5 October provided us with positions from which our artillery could be brought into action against Walcheren before the assault on that island. The withdrawal of guns for that task left the 3rd Division comparatively little artillery support in the final stages of SWITCHBACK.42 To the operations north of the Scheldt we must now return.

Operation VITALITY: The Clearing of South Beveland

As we have noted (above, page 391), the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division began its operation against South Beveland on 24 October, when the division’s right flank had been cleared by the operations of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division directed on Bergen op Zoom.*43

It was hoped to get forward rapidly, by-passing opposition, and seize crossings over the Beveland Canal. The Royal Regiment of Canada was to overcome the enemy’s first line of defences; then two mixed columns of armour (from the 10th Armoured Regiment and 8th Reconnaissance Regiment) and infantry of the Essex Scottish in armoured 15cwt. vehicles were to make the dash. After half an hour’s bombardment by seven field and medium regiments, the attack went in at 4:30 a.m. on 24 October. The Royals rapidly overran the enemy’s defences at the narrowest part of the isthmus, but thereafter met trouble. Mines and mud made a secondary road on the south side of the isthmus impassable, and Brigadier Cabeldu accordingly put in the Essex along the railway embankment in the north. But after several tanks and reconnaissance cars had been knocked out by a wellplaced anti-tank gun, the scheme of pushing through with the armoured columns was perforce abandoned. The operation again became one for the infantry. Real progress across the flat and flooded isthmus could not be made until after nightfall on the 24th. By evening on the 25th The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry had taken Rilland and advanced some distance beyond.44 With its leading troops in the area of Krabbendijke, the 4th Brigade, its men “very tired as a result of the constant fighting and movement in the past 48 hours over difficult country”, was halted on the 26th and the 6th Brigade passed through to continue the advance.45

The Canadians were now approaching the Beveland Canal, and the time had come for the amphibious attack across the West Scheldt by the 52nd (Lowland) Division to turn the Canal line. It was delivered in the early hours of 26 October. Again the flotilla (this time including some naval assault landing craft) set out from Terneuzen, and again Lieut.-Commander Franks acted as navigator. Our artillery fired heavily on the landing areas beginning at 4:30 a.m.; and at 4:50 the 156th Infantry Brigade landed successfully on two beaches in the Hoedekenskerke area. There was slight opposition on the north beach, none on the south; and although some resistance developed during the day the 156th enlarged its bridgehead successfully and captured Oudelande.46 Thus the formidable Beveland Canal had been outflanked before the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade began the frontal attack towards it that afternoon.

The 6th Brigade attacked with all three battalions up, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada on the right, The South Saskatchewan Regiment in the centre, directed on the main road and railway crossings over the canal, and Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal on the left pointing for the southern terminus of the canal at Hansweert. During the day the brigade lost its commander, Brigadier

* On 25 October the 2nd Division’s advance was designated VITALITY I and the 52nd Division’s operation across the Scheldt VITALITY II.

Gauvreau, who was seriously hurt when his jeep struck a mine. Lt.-Col. E. P. Thompson of the Camerons took over. The Camerons made the fastest progress, reaching the canal during the night of the 26th-27th. The other units were hampered by mortar and small arms fire, mines and road blocks, but the South Saskatchewan got to the canal in the early morning of the 27th. The bridges had of course been blown; but fortunately the enemy’s resistance was not well organized and was less of a handicap than the extensive flooding. By midnight of the 27th-28th the South Saskatchewan had crossed the canal, using assault boats, and in the early morning the Fusiliers also got over. Opposition was heaviest on the right, and the Camerons met fierce fire when they tried to cross; they were finally told to desist and concentrate upon preventing the enemy from damaging the important locks at the north end of the canal.47 Early in the afternoon of the 28th the engineers finished bridging the canal on the main road, and about the same time the 4th Brigade again came forward to take over from the 6th. The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry led the new advance against only moderate opposition and on the morning of the 29th The Royal Regiment of Canada linked up with the 156th Brigade in the vicinity of Gravenpolder.48

With the canal line gone, the Germans were apparently now thinking mainly of getting out of South Beveland, and on the 29th both the 2nd Division and the 52nd made rapid progress. The 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade had come in on the right, and The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada took Goes, South Beveland’s capital town, during the day (“The men had to kiss babies and sign autographs all the way through town”).49 The 2nd Division, which had thought its work would be done when South Beveland was clear, was now allotted the task of crossing the causeway to Walcheren, and by late afternoon of the 30th the Royal Regiment was within half a mile of its eastern end. Brigadier Keefler, the acting divisional commander, had told the 4th and 5th Brigades (to encourage rapid advance) that the brigade reaching the area first would hold the near end of the causeway; the other would then push across it and form a small bridgehead. Thereafter the 157th Brigade of the 52nd Division would relieve it for the further operations on Walcheren.50 During the morning of 31 October, accordingly, the Royals, supported by heavy mortars and artillery, cleared the bunkers at the east end of the causeway, capturing 153 prisoners.51 This completed the task of the 4th Brigade, and the 5th took over for the difficult job of obtaining a bridgehead on Walcheren.

On this same day on which the clearing of South Beveland was completed, a largely independent minor operation was launched against the neighbouring island of North Beveland, through which parts of the retreating enemy force were seeking to withdraw by sea. A squadron of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment commanded by Major C. R. H. Porteous ferried itself over to the island across the channel called the Zandkreek, and with the support of heavy mortars and machine-guns of The Toronto Scottish Regiment (MG) rapidly overran it, completing the task by noon on 2 November. North Beveland yielded over 450 prisoners.52

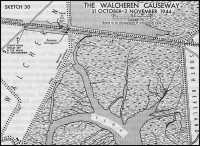

Sketch 30: The Walcheren Causeway, 31 October–2 November 1944

The Fight for the Walcheren Causeway

The causeway leading from South Beveland to Walcheren was singularly uninviting. It was some 1200 yards long and only about 40 yards wide, with sodden reed-grown mud-flats on either side. It was as straight as a gun-barrel and offered no cover except bomb-craters and some roadside slit trenches dug by the Germans in accordance with their custom. The line of spindly trees fringing its southern edge had been badly blasted. The causeway carried the railway line (a single track, the second track having been removed) and the main road; also the characteristic Dutch bicycle-path. At its western end, although it abutted upon one of the few dry areas of Walcheren, there was a wide water-filled ditch on each side of the embankment. The German engineers had been unable to cut the causeway completely, but they had cratered it very heavily just west of its centre, creating a transverse “furrow” which filled with water armpit-deep. This made the causeway impassable to tanks or other vehicles. The Germans’ artillery had certainly registered carefully upon it. They had infantry positions dug into the eastern dyke of Walcheren on either side of the causeway; the road at its western end was heavily blocked; there was a tank or possibly a self-propelled gun dug into the railway embankment just west of the block, and in addition there are reports of a high-velocity gun firing straight down the road.53

Although an assault along the causeway promised to be difficult and very costly, the headquarters of the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade saw no alternative. The

possibility of using amphibious vehicles to cross the mud and water to the north or south was considered, but there was not enough water to enable them to swim more than a short part of the way, and it appeared that the mud-flats intervening between the open channel and the Walcheren shore were an impassable barrier to either wheels or tracks. Accordingly, it was decided that the infantry would have to attack across the causeway, and Brigadier Megill set up a tactical headquarters in a house about a mile south-east of its eastern end to control the operation.54

The first attempt was made early in the afternoon of 31 October by the Canadian Black Watch with one company. They met extremely heavy fire from artillery, mortars and machine-guns and suffered many casualties. “The enemy was firing at least one very heavy gun the shells of which raised plumes of water 200 feet high when they fell short. He was also ricocheting armour-piercing shells down the causeway, which was hard on the morale of the men.”55 At 3:35 in the afternoon it was reported that our leading troops were only 25 yards from the eastern dyke of Walcheren and “trying to inch forward”. But the Black Watch made no further progress and were withdrawn that evening. Brigadier Megill now put in The Calgary Highlanders to renew the attack. The intention was that the Calgaries should advance across the causeway and move out to the right, with Le Regiment de Maisonneuve concentrated behind ready to move across and “fan out to the left”.56 The leading Calgary company, moving on to the causeway about 11:00 p.m., met the same sort of opposition and the Commanding Officer (Major R. L. Ellis) was given permission to withdraw. ‘Brigadier Megill now arranged heavy artillery support for another attack by the battalion, first timed, it appears, for 5:15 a.m. on 1 November and twice postponed; it finally went in at 6:05.57

At 7:10 a.m. the leading company reported that it had met a “very extensive road block” at the end of the causeway, and was encountering much machine-gun fire and some sniping, as well as heavy-calibre shelling; it hoped however that “given some time” it could get through. Ten minutes later the company was reported through the block and less than 100 yards from the open, still moving forward in spite of machine-gun fire and shelling. At 8:00 a.m. it was held up at the extreme west end of the causeway, still not clear of it. During the morning progress was made and about noon all the platoons of the leading company were on the mainland of Walcheren, a second company had passed through them and the others were moving up.58 One of the companies having lost its only two officers, the Brigade Major of the 5th Brigade, Major George Hees, obtained permission to go across and take command of it; an artillery Forward Observation Officer, Captain W. C. Newman, accompanied him.59 It now seemed that the bridgehead on Walcheren was firm. An armoured bulldozer had a try at filling in the big crater; but “30 seconds later it was driven off by a short sharp burst of 5 88-mm. shells”. The enemy had not loosed his grip. On the contrary, about 5:30 p.m. he put in “a determined counter-attack”.60 No one who was there set down any details, though the 1st Battalion of the Glasgow Highlanders (Highland Light Infantry), who were waiting to move across into Walcheren, recorded a

rumour that flame-throwers had been used.61 At any rate, at 6:00 p.m. it was reported that the Calgaries’ leading troops were back on the causeway, 300 yards from the western end.62 The battalion’s two least tired companies took up a defensive position near the crater, the others being withdrawn.63

Brigadier Megill now put in his third and last battalion, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve.* In consultation with the commander of the 157th Brigade of the Lowland Division, he arranged that the Maisonneuves should attack across the causeway with heavy artillery support at 4:00 a.m. on 2 November and re-establish the bridgehead on Walcheren. In accordance with orders from divisional headquarters, they would then be relieved at 5:00 a.m., before dawn, by the 157th Brigade’s leading unit, the Glasgow Highlanders.64

The attack began on time, with three medium regiments firing counter-battery tasks and three field regiments firing a barrage. However, the same sort of opposition that had greeted the earlier advances came down to meet the Maisonneuves. D Company, which was leading, was 200 yards short of the west end of the causeway at 4:15. Thereafter it progressed slowly and at 6:30 was reported in positions on the mainland 200 yards north and the same distance south of the causeway.65 The other companies did not cross, the foremost one getting no more than half-way;66 and after five o’clock they were ordered out. It was now understood that the Glasgow Highlanders would commence to relieve D Company at 6:00 a.m.67

An advance across the causeway was still a very unpleasant prospect. At 5:20 the commander of the 157th Brigade told the Glasgow Highlanders’ commanding officer that the relief was to go on, but that his battalion was not to put across any more troops than Le Régiment de Maisonneuve had, “after deducting casualties”. The Glasgow CO, having consulted Lt.-Col. J. Bibeau of the Maisonneuves, who told him that he believed he had not more than 40 men alive in the forward area, agreed to relieve the Maisonneuves with one platoon. Shortly afterwards Major Hees, who had been forward in the Maisonneuve bridgehead, came back across the causeway and reported the way clear and the Maisonneuves on their first objectives. At 6:10, accordingly, a single platoon of the 1st Battalion of the Glasgow Highlanders started across the causeway. Major Hees accompanied them and in so doing was wounded by a sniper.68

For the next seven or eight hours the small groups of Maisonneuves clung to the exiguous bridgehead. During this period Private J. C. Carriere won the Military Medal by crawling forward down a water-filled ditch and knocking out with a PIAT a 20-mm. gun which was harassing the position.69 Relieving the Maisonneuve parties was “a matter of first importance”; Brigadier Megill pressed Brigadier J. D. Russell of the 157th Brigade on this point, and both brigadiers pressed the commanding officer of the Glasgow Highlanders. Since the enemy opposition was as fierce as ever, carrying out this relief was far from easy. But additional Glasgow men gradually followed the first platoon across, and at 11:55 a.m. another platoon

* The best sources of information for the events of 2 November on and about the causeway are the log of the 5th Brigade’s tactical headquarters and the very detailed diary kept by the 1st Glasgow Highlanders. The Maisonneuve diary gives very little detail.

joined the elements of the Maisonneuves who were holding a house and a railway underpass some 500 yards west of the end of the causeway. But the situation was too unpleasant to enable the Canadians to get out at once. About two hours later, under cover of smoke fired by the 5th Canadian Field Regiment,*70 both the Glasgow platoon and the Maisonneuves withdrew; three Highlanders remained in the house with a wounded man.71

These soldiers of the Maisonneuve, and the gunners who covered their retirement, were the last troops of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division to be engaged in the Battle of the Scheldt, except for a platoon of the 7th Field Company RCE who “corduroyed the crater” on the causeway on the morning of the 3rd.72 The division, desperately tired, now withdrew to rest about Malines. Since the crossing of the Antwerp-Turnhout Canal late in September it had captured over 5200 Germans and killed an unknown number more. Its own casualties in all categories were computed at the time as 207 officers and 3443 other ranks. The 5th Brigade’s battalions had had a total of 135 casualties in the three days’ fighting at the causeway.73

Since the Glasgow Highlanders were having, for the moment, no better fortune than the Canadians in enlarging the tiny bridgehead at the west end of the causeway, other means of progress had to be found. The 52nd Division’s CRA, Brigadier L. B. D. Burns, with an improvised headquarters known as “Burnfor”, had taken charge of the Division’s two infantry brigades attacking Walcheren from this direction. In addition, the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade and the 5th Field Regiment RCA seem to have been briefly under Burnfor.74 Attention now turned again to the possibility of an attack across the Slooe Channel south of the causeway. The use of amphibious vehicles, as the 5th Brigade had concluded, was out of the question. The only alternative was to use assault boats to cross the open channel and thereafter for the infantry to struggle on foot across and through 1500 yards of “soft wet sand” which was often unpleasantly like quicksand. Beginning at 3.30 a.m. in the morning of 3 November the 6th (Lanarkshire) Battalion of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) got across in this manner from a little harbour two miles south of the causeway to the extreme south-eastern point of Walcheren. Fortunately the crossing was nearly unopposed, but resistance developed and stiffened after dawn. By noon the leading Cameronians were reported well inland from the point of landing. Yet the Germans continued to fight hard in this unflooded part of Walcheren, and the new bridgehead was not linked up with that at the end of the causeway until early on 4 November, by which time opposition on the island was beginning to collapse.75

Preparations for the Landings on Walcheren

It is important to remember that while the operations just described were proceeding on the eastern shore of Walcheren, the island was being assailed from two other directions: by an amphibious attack on Flushing across the West Scheldt

* This fire plan was “laid on” by Lieut. D. G. Inns of the 5th Field Regiment, working as a Forward Observation Officer with D Company of La Regiment de Maisonneuve, who remained at his post though wounded. He received the Military Cross.

(Operation INFATUATE I) and by a seaborne assault at the western point of the island at Westkapelle (INFATUATE II). The costly opposed. landing at Westkapelle became the most controversial portion of the whole Scheldt battle. The preliminaries of the INFATUATE operations must therefore be reviewed.

Walcheren was fortified with what Combined Operations Headquarters later called “some of the strongest defences in the world”.76 Heavy batteries were particularly numerous on its western beaches facing the North Sea. The guns ranged up to 22-cm. (8..7-inch) in the battery (W 17) just west of Domburg, but those which proved most formidable were W 15, immediately north of Westkapelle (mounting four 3.7-inch British anti-aircraft guns), W 13, on the dunes south-east of Westkapelle (four 15-cm. or 5.9-inch guns) and—less dangerous at Westkapelle because of its distance from the assault area—W 11, about two and a half miles west of Flushing (four 5.9-inch guns).* There were numerous smaller guns and several heavy anti-aircraft batteries. The heavy coastal guns were all manned by the 202nd Naval Coast Artillery Battalion. The flooding resulting from our breaching of the dykes had put a number of batteries out of action. Unfortunately, however, most of the coastal batteries, including the four specifically mentioned above, were all on the perimeter dyke itself, and did not suffer directly from the flooding, except, as we shall see, for some important interference with ammunition supply. Our intelligence concerning the defences was in general excellent.77

[The reference to footnote † (sword) is missing78]

There were three possible means of destroying or neutralizing these positions: naval bombardment, artillery fire from south of the Scheldt, and air action. The reasons which made naval bombardment impracticable before D Day are noted below (page 409).

The artillery programme was coordinated by the CCRA 2nd Canadian Corps, Brigadier A. Bruce Matthews. He had a great force of artillery at his disposal. But the effectiveness of his guns, though formidable in the Flushing area, was much reduced at Westkapelle, which is roughly nine miles from the northernmost point of the mainland. Only those heavy regiments armed with 155-mm. guns, and the single super-heavy regiment with its 240-mm. howitzers and 8-inch guns, could reach the batteries north of Westkapelle.79

On 31 October Brigadier Matthews had available for the Walcheren operation the field artillery of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division (less the 5th Field Regiment, which, along with the artillery of the 52nd Division, was supporting the operations at the causeway) with the 61st and 110th Field Regiments RA under command; the 2nd Canadian Army Group Royal Artillery, consisting of the 3rd and 4th Medium Regiments RCA, the 15th Medium Regiment RA, the 1st and 52nd Heavy Regiments RA (the latter less two 155-mm. batteries), and the 3rd Super-Heavy Regiment RA; the 9th Army Group Royal Artillery, having under its command the 9th, 10th, 11th and 107th Medium Regiments RA, the

* The numbers here applied to batteries are those that were used to designate them in Allied target lists. Our Intelligence before the assault credited W 15 with four 15-cm. guns. This had in fact been its armament in April 1944, but by June it had been altered. The 15-cm. guns seem to have been Moved to the Zoutelande battery (W 13).

† These three weapons (all of US type) had maximum ranges, respectively, of 26,000, 25,000 and 35,000 yards. The 3rd Super-Heavy Regiment RA had two 8-inch guns and four 240-mm. Howitzers available for INFATUATE.

51st Heavy Regiment RA and the 59th (Newfoundland) Heavy Regiment RA (less one 155-mm. battery); and the 76th Anti-Aircraft Brigade RA with the 112th and 113th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiments RA under command.80 The total number of guns seems to have been 314 (a calculation of 338 made on 27 October assumed the presence of five field regiments, whereas only four were actually available).81 The main gun group was in position to answer calls for fire either from the Flushing operation or the Westkapelle operation; the 2nd AGRA had its gun areas in the region roughly west of a line running south from Fort Frederik Hendrik, the 9th AGRA east of this line. Since the landings were not simultaneous, it was possible to bring the main weight of artillery to bear in support of the Flushing assault before the landing, and subsequently switch it to Westkapelle.82 But the field regiments, armed with 25-pounders, were unable, for lack of range, to take part at Westkapelle.83

Although no detailed counter-battery programme was prepared to be fired before D Day, increasing fire was brought down on located hostile batteries and other targets during the days before the assault as guns became available. Since parts of the gun areas were not cleared until 29 October, some regiments got into position only in time to take part in the D Day shoot. One of the last heavy shoots before D Day was on the evening of 31 October, when enemy guns north-west of Flushing which had been shelling Breskens were engaged by three medium regiments.84

A detailed time programme was prepared for firing on D Day, with three alternative plans for INFATUATE I which might be used as ordered, according as whether INFATUATE II was carried out or cancelled.85 For INFATUATE II there was a timed programme beginning at 70 minutes before H Hour and continuing until 60 minutes past it. Battery W 11 was to be engaged throughout this period by 7.2-inch guns and for a time by mediums. W 13 was to be steadily engaged from H minus 70 until H minus 5 by the 3rd Super-Heavy Regiment. W 15 was to be bombarded by 155-mm. guns of the 1st and 59th Heavy Regiments from H minus 70 to H minus 20.

A new bombardment element was present on this occasion-an experimental rocket battery armed with 12 projectors developed in the United Kingdom as a Canadian project and known by the quaint code name LAND MATTRESSES. Manned for INFATUATE by the 112th Battery of the 6th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment RCA, these weapons were fired for the first time on 1 November, their targets being enemy positions about Flushing. Although the results could not be observed, the experiment made a good impression, which was heightened when the unit supported the Poles near Moerdijk on 6-8 November. Accordingly, the “1st Canadian Rocket Battery” was formed and remained an active element of First Canadian Army until the end of hostilities.86

It was the air plan on which later controversy chiefly centred. We have seen that First Canadian Army asked in the very beginning for prolonged heavy bombing of the Walcheren positions, but that Field-Marshal Montgomery concurred in the opinion of Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory that this should not be done (above,

pages 359, 378). Although Leigh-Mallory had taken the precaution of obtaining General Eisenhower’s concurrence in principle, it appears nevertheless that in the early days of October the Supreme Commander insisted, through his Deputy, that Walcheren should rank as first priority for the heavy bomber force. This was the period when the dykes were being breached. But many senior Allied air officers believed that it was now more important to strike heavy blows against German communications and industry than to afford direct support to the armies. Specifically, the Deputy Supreme Commander and members of the SHAEF air staff*87 had evolved a plan known as Operation HURRICANE involving particularly heavy Anglo-American bomber attacks against targets in the Ruhr. Though weather caused the cancellation of this particular plan, which had been due to be launched on 15 October, the general preoccupation with targets in Germany was not affected. The German petroleum industry, as already noted (above, page 377) was now the air forces’ preferred first priority. On 24 October Air Chief Marshal Tedder, presumably acting with the authority of the Supreme Commander, forbade further heavy bomber attacks against the Walcheren dykes (which in any case had already been satisfactorily breached) and ordered a Joint Air Plan for INFATUATE to be made by the 2nd Tactical Air Force and the First Canadian Army. On the same day No. 84 Group RAF was instructed by the 2nd Tactical Air Force to take over from the heavy bombers the task of silencing a number of batteries.88

The Air Plan for Operation INFATUATE was in fact made by No. 84 Group in consultation with HQ First Canadian Army and was dated 27 October.89 This document’s comment on the problem of the Walcheren defences may be quoted. After remarking, “The light scale of equipment of the [assaulting] forces used and their vulnerability to shore defences coupled with the need to capture the island quickly makes the thorough destruction of these defences a necessity”, it proceeded:

5. There are three means by which the Walcheren defences might be put out of action before D Day

i. air bombardment

ii. naval bombardment

iii. bombardment by artillery based in the Breskens area.

Naval bombardment is being used to cover the Assault itself and all ammunition carried in the ships will be required for this purpose. If these ships were used for pre-D Day bombardment, they would have to return to UK to rearm before the Assault. Return and rearm takes three days. Their lack of effect (compared with air bombardment) and this gap of three days rules out naval bombardment as a preparatory measure.

6. Shore-based artillery is being moved up towards Breskens but cannot be mounted in any strength until the Breskens bridgehead has been cleared of the enemy. Moreover, ammunition supply difficulties for the heavy and super heavy guns limits their use before D Day.

7. We have to rely therefore on air bombardment for the necessary destruction of the defences before D Day. Some of this bombardment is being undertaken by aircraft of 84 Group. Many of the defences, however, are concrete gun emplacements and heavy pillboxes which cannot be put out of action by the weight of attack this Group is able to deliver. [These must therefore be attacked by Bomber Command.]

...

* It may be noted here that when Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Air Force was dissolved on 15 October (below, page 420) “Air Staff, SHAEF” took its place. To the disappointment of American airmen who hoped for the appointment of a US officer, the new staff was headed by Air Marshal J. M. Robb, RAF.

10. It can hardly be expected that all the defences attacked by Bomber Command will be completely destroyed and some may be effective or be repaired after bombardment but before the Assaults. Some of these defences that have come to life again may vitally jeopardize the Assault, particularly the guns near Flushing and near Westkapelle. Should this happen, it is most desirable that Bomber Command should be requested to attack these individual targets again when possible, up to the agreed times of last bombing for each Assault.

The Army and No. 84 Group had agreed upon schedules of targets on Walcheren within and outside the resources of No. 84 Group. The schedule of targets outside the Group’s capacity was repeatedly amended, the latest complete version being prepared on 22 October. The 33 targets listed in it as amended comprised four batteries (W 11, W 13, W 17 and W 15) which were considered to affect minesweeping or the deployment of bombardment ships; seven batteries capable of firing on to the south bank of the West Scheldt (three of these were cancelled before D Day); seven anti-aircraft batteries affecting the operations of No. 84 Group (one of these was cancelled before D Day); six other batteries (of which all but two were cancelled before D Day); and nine strongpoints and concrete emplacements.* (In addition, the “defended area” at Flushing was added as a “special target” after the main document was issued.)90 The covering memorandum remarked, “Targets are not listed in a rigid order of priority but are listed in a general sequence which may be taken as a guide to what is operationally desirable.” This appears to mean that the order in which the targets were listed (apart from the “special target”, that just given), represented a general order of priority, with the four batteries capable of interfering with minesweeping or bombardment coming first. These four batteries were also those which represented the most serious menace to the actual infantry assault.

First Canadian Army and No. 84 Group asked that the targets listed might be “appropriately engaged on a programme of bombing to be completed by” midnight 31 October-1 November. They added, “Insofar as may be practicable, it would be desirable for this programme to be compressed into the period” between midnight 28-29 October and midnight 31 October-1 November. This amounted to a request that the RAF Bomber Command should engage all the targets listed within the space of three days before the assault.91 On the question of D Day air support, the Air Plan asked for “preliminary heavy bombardment of the defences and a small area in the town and waterfront” of Flushing as late as possible before the landing, weather permitting. At Westkapelle the air support was to come entirely from within the resources of No: 84 Group.92 (A Commando conference on bombing on 21 October had agreed that it was undesirable that the heavy bombers should bomb Westkapelle, “as a bad shot might hit the dyke and so render it impossible for tanks to negotiate”.93 This evidently referred only to the village and not to the adjacent batteries.)

Bomber Command went a considerable distance towards meeting the Air Plan’s request. Significant daylight attacks were delivered against Walcheren on 28, 29 and 30 October. On the first of these days, 261 heavy bombers attacked guns at Flushing and the dangerous batteries near Dishoek (W 11), Domburg (W 17),

* The cancellations were chiefly due to flooding.

Westkapelle (W 15) and Oostkapelle (W 19). In all the attacks together, some 1189 tons of high explosive were dropped. The largest single attack ever delivered against Walcheren was that on 29 October, when 358 aircraft were sent out and 327 attacked, directed upon 11 aiming points. On this day 1562 tons of HE were dropped. On 30 October, a further attack was made, but by only 89 aircraft which dropped 555 tons.* At this point the weather took a hand. Bomber Command could not operate over Holland during the day of the 31st, and the Flushing attack planned for the night before D Day also had to be cancelled. However, the attacks planned for the 31st were not heavy, and none of the intended targets was in the Westkapelle area: 25 Lancasters each were to attack W 1, W 3, W 6, and W 33-all near Flushing. Thus the cancellations had no effect on the Westkapelle assault. From 17 September through 30 October, Bomber Command had flown 2219 sorties against Walcheren and dropped 10,219 tons of bombs.94

While it is evident that considerable effort had been directed against Walcheren, the weight of bombs was much less than that dropped in support of the Army in the Normandy campaign or at the Channel Ports (one remembers the 3700 tons dropped in Operation TRACTABLE, the 3200 dropped in a single attack on Boulogne). The fact is that even in the final period before the assault Walcheren was not being given the highest priority among Bomber Command targets. During the night 30-31 October, for example, 984 aircraft of the Command attacked Cologne, dropping 4142 tons. On the following night 493 aircraft again attacked Cologne, dropping 2703 tons.† On 28 October, when as we have seen between 200 and 300. bombers attacked Walcheren, 734 hit Cologne in a day attack, dropping 2911 tons. During the whole month of October, Bomber Command made 1.106 sorties against factories and oil refineries, dropping 5306 US tons, and 10,930 sorties against city areas (51,312 tons); but “army support and tactical targets” got only 1616 sorties and 9728 tons.95

At the headquarters of the 4th Special Service Brigade, which carried out the Flushing and Westkapelle assaults, there seems to have been a feeling after the operation that “there had not been sufficient insistence by First Cdn Army” on getting the weight of air support which the circumstances required.96 Actually, the Air Plan represented everything that the naval and military Force Commanders for INFATUATE II had asked for (below, page 412); though it is highly probable that a document prepared by Army Headquarters alone, and not requiring to be signed jointly with No. 84 Group, would have been more strongly phrased. The direct link to Bomber Command which Army Headquarters had asked for had been refused; negotiations had to be conducted through No. 84 Group.97 Experience in Normandy and at the Channel Ports suggests that if it had been possible to deal direct with Air Chief Marshal Harris the bomber effort effort at Walcheren.. might have been heavier and lives might have been saved.

* In all the attacks on Walcheren during October, including those directed against the dykes, Bomber Command lost six aircraft. Four were lost in a single attack, that on the Flushing batteries on 23 October.

† It would seem that, although the weather interfered with operations over Holland on the night of 31 October-1 November, it was better over Germany. Weather prevented any operations by the heavy day bombers of the US Eighth Air Force on 31 October.

The work of Bomber Command was of course far from being the whole story of air action against Walcheren before D Day. A total of 646 sorties were flown against the island by the 2nd Tactical Air Force on the three days 28-30 October.98

The Final Plan and the Decision to Assault

Walcheren was a name of ill omen, for the island had been the scene of a famous British fiasco during the wars with Napoleon. This time the result was to be happier; but the price of victory was high.

The landings on Walcheren were carried out by British troops. The 4th Special Service Brigade, commanded by Brigadier B. W. Leicester, made the assaults. At Westkapelle, where its main body went in, it operated directly under the 2nd Canadian Corps, which in turn was under First Canadian Army. Once well ashore, the brigade would come under the 52nd (Lowland) Division, which would then be in charge of all the military operations on Walcheren. At Flushing, one commando of the Special Service Brigade led the attack, followed by a brigade of the 52nd Division. While the final planning and preliminary operations were going on, Brigadier Leicester’s brigade was training near Ostend.99 It was to be landed at Westkapelle by the Royal Navy’s Force T, commanded by Captain Pugsley. The Acting Corps Commander (General Foulkes) exercised control of the operation from Ijzendijke, south-east of Breskens, where also his artillery commander set up his command post.100

Fixing the date of the assaults was itself difficult. The two earliest periods when tidal conditions would permit of landings were 1-4 November and 14-17 November.101 At a conference on 20 October General Foulkes explained that the Buffaloes being used in the attack on South Beveland could not reach Ostend before the 30th and (having regard to the need for some training with them) this plus considerations of ammunition supply meant that the 14 November date would have to be accepted for the Westkapelle assault. This would permit of a rehearsal. At this time the Westkapelle and Flushing assaults were considered as alternatives to each other. The Corps Commander said that there would be an all-out bombing effort for 48 hours, but this he thought of as ending 48 hours before the day planned for the assault; reconnaissance parties would then inspect the state of the defences at both Flushing and Westkapelle as a basis for decision as to whether, and where, an assault was practicable. Further bombing would be asked for “to maintain the softness achieved”; but neither assault would be made “unless it was definitely established that defences were softened”.102

During the next 24 hours the aspect of the plans changed. A report came in that Walcheren was now almost completely flooded; and on the basis of this (plus, perhaps, the obvious importance of attacking at the earliest possible moment) the commanders of the 4th SS Brigade and Force T proposed to Foulkes on 21 October that assaults be made at both Flushing and Westkapelle on 1 November “or as soon as weather permits”. They did however prescribe certain “minimum requirements”: that the flooding report should be accurate; that there should be a “heavy bombing attack for 48 hours, to be continued daily at sufficient scale until

weather allows of Operation taking place”; that the battleship Warspite and two monitors should be available; and that the reconnaissance party at Flushing and the naval support force at Westkapelle should find that the opposition was “not more than very weak”.103 On this basis the 4th SS Brigade produced a new provisional outline plan104 the same day; and in essentials this was the plan actually put into effect on 1 November. On that day, however, as we shall see, the authors of these proposals did not act upon their declared intention of attacking only if the defences had been decidedly softened.

On 22 October General Simonds, the Acting Army Commander, was forcibly reminded of the extreme importance of avoiding further delay in opening Antwerp. The Navy had always laid particular emphasis upon this point, and now Admiral Ramsay, having heard of the already abandoned plan to postpone the Westkapelle assault to 14 November, signalled Simonds emphasizing that it was “absolutely vital” to open the Scheldt as soon as possible and requesting confirmation of the earliest practicable date for the assault. Simonds immediately replied giving the timings then envisaged, including “softening air action” against Walcheren on 29-31 October and the assault by the 4th Special Service Brigade on 1 November. He added that ammunition and amphibious vehicles would not be limiting factors and observed that he understood that the tidal conditions would be essentially the same on 1 November as on 14 November. He concluded:

I have ordered 2 Cdn Corps to work to above timings and though you will appreciate weather conditions may cause variations of two or three days in target dates I intend to take Walcheren and Zuid Beveland by 1 Nov.

To this Ramsay replied “Your [signal]. Red hot. Best of luck.”105

The decision as to whether or not to attempt the assault on 1 November was likely to be difficult, in the light of probable weather conditions at that season and their effect on the air programme. But in view of the extreme urgency of opening Antwerp and the fact that postponement might mean that the landing could not be made until the 14th, it was evident that long chances might have to be taken. On 30 October Army Headquarters issued an elaborate instruction106 defining the authorities authorized to confirm or postpone INFATUATE I and INFATUATE II. For Westkapelle, the decision to embark or to postpone embarkation was the responsibility of the Army Commander jointly with the Allied Naval Commanderin-Chief Expeditionary Force and on the advice of the commander of No. 84 Group; the decision to sail or to postpone sailing rested with the Army Commander jointly with ANCXF Confirmation or postponement of the final decision, to assault, was for the commander of Force T jointly with the commander of the 4th Special Service Brigade.

On 31 October, with the weather going to pieces, the question of the decision to undertake the operation became increasingly difficult. Admiral Ramsay met with Generals Simonds and Foulkes at Bruges, and they decided that the 4th Special Service Brigade should embark and sail if the weather did not get worse.107 Late that afternoon, on board the headquarters ship, HM Frigate Kingsmill, at Ostend, Simonds and Ramsay, in the presence of Brigadier Leicester and Captain Pugsley, amended the orders concerning a decision to postpone the assault. The original

instruction had provided that such a decision would be taken by the naval and military force commanders “only ... on naval considerations related to weather which render the landing of the assault force impossible”. The new one108 empowered the naval and military force commanders afloat “to postpone the assault and return to port if in their opinion on all available information (with particular reference to the probabilities of air support, air smoke and spotting aircraft for bombardment ships) at the time of taking such decision the assault is unlikely to succeed”. At 9:15 p.m. on the 31st General Simonds and Admiral Ramsay discussed the question by telephone and reaffirmed this direction extending the powers of the two commanders afloat. At the same time the joint decision was taken to order the force to sail.109 It sailed accordingly.

In HMS Kingsmill off the western point of Walcheren in the dawn of the 1st of November, with the Westkapelle lighthouse already in sight, Brigadier Leicester and Captain Pugsley faced the ultimate decision. They now knew the worst, for at 6:00 a.m. the Chief of Staff at Army Headquarters had sent a grim emergency signal110 to his opposite number at 2nd Corps:

Pass following to Admiral Ramsay for transmission by him to Force T in clear.* Quote extremely unlikely any air support air spotting or air smoke possible due to airfield conditions and forecast. Unquote.

* The message was undoubtedly sent in clear to avoid the delay involved in enciphering and deciphering.

In the light of their latest instructions, the men in Kingsmill would have been justified in regarding this as good reason for postponing the operation. On the other hand, they saw two encouraging aspects to the situation. The sea was calm—and it might not be calm if they waited another day. (In fact, as it turned out, sea conditions for several days to come were to be such as to make landings impossible.) Also, though the sky was overcast it appeared to be clearing, and it seemed possible that air support would be practicable later in the day.111 The naval and military force commanders knew the importance of the operation. Nevertheless, they knew also that to put in the assault under the existing conditions was to pronounce sentence of death upon many fine men and vessels. They did not shrink from the responsibility.†

† There is some indication that they had indeed decided in advance that the previous plan to suspend the operation if opposition was heavy was impracticable, and that it would go in unless sea conditions were prohibitive. Admiral Pugsley, however, has written that the final decision to assault was taken only after the heavy ships opened fire at 8:20.112

The officers waiting anxiously at the 2nd Corps command post at Ijzendijke shortly received from the frigate a pre-arranged code word not inappropriate to the circumstances. It was NELSON.113 Leicester and Pugsley had decided to proceed.

The Assault on Flushing

The attack on Flushing went in four hours before that at Westkapelle. It was delivered by the 155th Infantry Brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, with No. 4 Commando‡ making the first landing. As we have seen, artillery support

‡ This was an Army unit, whereas the other three units of the 4th Special Service Brigade, assaulting at Westkapelle, were Royal Marine Commandos.

Sketch 31: The Capture of Walcheren, 1–8 November 1944

from the south shore of the river “was on a vast scale”.114 This was the more vital as the hoped-for bombardment by heavy bombers had proved impossible. There had been controversy with the Netherlands Government in London over the proposed bombing of Flushing. The Dutch very naturally thought of the possible casualties to the civilian population rather than those the attacking troops might suffer in an inadequately supported assault; and as a result of this opposition the British Government objected to any bombing of the city unless authorized by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. There was an exchange of signals on 31 October between the Supreme Commander and the British Chiefs of Staff. General Eisenhower, while expressing every desire to spare the city, felt that it would be a serious matter to withhold this aid from the Canadian Army and thereby help the enemy. The question seems to have been referred to Mr. Churchill, who took the view that, though every effort should be made to spare the civilians, the opinion of the Supreme Commander must prevail. In these circumstances, it was the weather and not Allied policy that prevented an attack by heavy bombers on Flushing on 1 November. Mediums of No. 2 Group RAF did attack the beach defences during the night preceding D Day.115

At about 4:40 a.m. on 1 November the landing craft carrying No. 4 Commando slipped out of the harbour of Breskens. “At almost the same moment the artillery barrage commenced, and the mainland was from now on silhouetted against the flickering muzzle flashes of three hundred guns.”116 At 6:20 the Commando touched down at Flushing in the face of slight opposition. It was shortly followed by the 4th Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the other units of the 155th Brigade. There was some fierce fighting on shore in Flushing, and the city with its shipbuilding yards (where snipers lurked in the gantries) and many old and new fortifications was not finally declared clear until the morning of 4 November.117 The 52nd Division had used its 3.7-inch mountain guns in the course of this action. “On more than one occasion, a dismantled gun was taken up to one of the upper floors of a house, and re-assembled there. It then engaged suitable targets at point-blank range with surprising effect.”118

The Assault at Westkapelle

The Westkapelle plan of attack, as detailed in the 4th Special Service Brigade’s operation order dated 24 October, provided for an assault at the gap in the dyke made by the RAF The Commandos’ first flight was to land from infantry landing craft (small), the remainder coming ashore in amphibious vehicles from tank landing craft. Covering parties were to seize the shoulders of the gap (No. 41 Commando on the left, No. 48 on the right) and the main bodies were then to pass through the gap in their amphibians. Thereafter No. 41 was to secure Westkapelle and destroy batteries in the area if active. Its probable subsequent task was to move north against the Domburg battery, leaving No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando* to protect the brigade’s left flank. No. 48 was to clear the area soutward

* The portion of this unit engaged included British, Norwegian, Belgian and Dutch troops. About 100 French soldiers were with No. 4 Commando at Flushing. First Canadian Army, always very much an international force, was more so than usual while these units were under its command.

at least as far as Zoutelande. No. 47 Commando was to go through the gap and clear the dune southward from Zoutelande, dealing if necessary with Battery W 11 and other positions in the area.

The heavy bombardment ships were the battleship Warspite and the monitors Erebus and Roberts, mounting between them ten 15-inch guns. (Warspite’s main armament, originally eight guns, was now down to six as a result of battle damage sustained in the Mediterranean.) Close support for the landing was to be afforded by the unit known as “Support Squadron, Eastern Flank”, under Commander K. A. Sellar. It consisted of 27 craft of various types,* of which the most powerful were the large and medium Landing Craft Gun, mounting respectively 4.7-inch and 17-pounder guns.

For a time the troops in the landing craft wondered whether the German batteries had been knocked out or whether they would come into action. They did not have long to wait. “Pinpoints of light sparkled from the south batteries”119 as the Germans opened up. The first fire, directed at a motor launch marking the position where the headquarters ship was to anchor, came at 8:09 a.m. from W 15 at Westkapelle. Shortly every German battery in the area was in action. Warspite and Roberts returned the fire, beginning at 8:20; a defect in the turret mechanism of Erebus prevented her from firing in the first phase. But without their spotting aircraft (which were fogged in on English airfields) the big ships were firing almost blindly. They had asked for army “air observation post” planes to replace these aircraft, but although the AOPs. were duly provided they “proved ineffective due to poor communications”.120 The bombarding ships nevertheless knocked out two of the guns of Battery W 15.

Since the air attacks had not silenced any large proportion of the guns in the batteries, and since the heavy ships were unable to fire accurately until the afternoon, when their own spotting aircraft were able to act, the brunt of the action fell on the Support Squadron. These small vessels drove in without regard for their own peril, blazing away at the formidable concreted batteries with every gun. From about nine o’clock onwards they were fiercely engaged.

It is a tradition of the Royal Navy to sacrifice itself for its convoys when circumstances require it. The Support Squadron lived up to this tradition at Westkapelle. Sellar wrote later in his report: