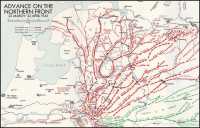

Chapter 20: The Rhine Crossing and the 2nd Corps’ Advance to the North Sea, 23 March–22 April 1945

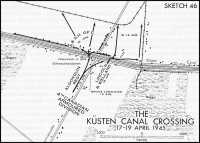

(See Map 12 and Sketches 42, 43, 44, 45 and 46)

Strategy: Malta and Yalta

The long road from the Normandy beaches had reached the banks of the swollen Rhine. Allied soldiers, peering eastward across the swiftly-flowing water, realized that this was the last major barrier before the heart of the enemy’s homeland.

They faced the task of making an assault crossing of this formidable obstacle with confidence. Their victories in the Ardennes and in the savage battles west of the Rhine had demonstrated their superiority over a foe unquestionably skilful and courageous, but now exhausted and desperate. On the long eastern front the Russian tide was flowing across the Oder and menacing Vienna. An early junction between the Allied forces invading Germany from east and west appeared inevitable; further German resistance seemed futile. The end was in sight. The question uppermost in Allied minds was, how soon would it come?

In these buoyant circumstances any fundamental disagreement over the strategy to be employed in forcing the passage of the Rhine and compassing the final defeat of Germany might have appeared improbable. In practice, however, the issues were far from simple and the strategic problem provoked between British and American leaders one of the sharpest controversies of the entire war.

When the Combined Chiefs of Staff met at Malta (30 January-2 February), as a preliminary to the main ARGONAUT conference to be held with the Russians at Yalta, a warm argument soon developed over future strategy in North-West Europe.1 The discussion hinged on the directive, if any, to be issued to General Eisenhower for the remainder of the campaign. In a sense this was a revival, on a higher level, of the “broad front” versus “single thrust” controversy between Eisenhower and Montgomery (above, pages 306-13 and 316-22). The Supreme Commander had prepared a tentative plan based on the possibility of seizing two bridgeheads across the Rhine—one, north of the Ruhr, between Emmerich and Wesel, and the other upstream, between Mainz and Karlsruhe. He realized that a heavy attack in the north offered the quickest means of eliminating the Ruhr industries and reaching the most favourable terrain for mobile operations. However,

suitable sites in the Emmerich-Wesel sector were restricted to a 20-mile frontage on which only three divisions could be initially employed, leaving an Allied attack vulnerable to a quick German concentration. On the other hand, between Mainz and Karlsruhe there were sites for at least five assaulting divisions, with less danger of effective opposition. Eisenhower therefore planned a secondary crossing here.

The British objection to these proposals, stated by Field-Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, was based mainly on fear of dispersion. Just as in the dispute the year before over the invasion of southern France, the British argued for greater concentration of effort, while the Americans urged the advantages of a large-scale diversionary operation. Specifically, the British Chiefs of Staff felt that there was insufficient strength for two major operations across the Rhine. In their opinion the advantages of concentrating Allied effort in the northern sector—nearer the Antwerp base and in a better position to menace the Ruhr—far outweighed any benefits which might be expected from an attack in the south, unless the latter was clearly subsidiary to the main thrust. Brooke and his colleagues were also concerned about the Supreme Commander’s evident intention to close up to the Rhine throughout its length before advancing into Germany. This, they felt, might result in undue delay. In the background of the strategic problem was a further complication—continuing controversy on the need or otherwise for a commander of all Allied ground operations, under the Supreme Commander, with powers similar to those exercised by Montgomery during the Battle of Normandy. The British were still convinced that such a commander was necessary; the Americans still rejected the suggestion, and when Mr. Churchill proposed, as he had lately done, that Field-Marshal Alexander should replace Air Chief Marshal Tedder as Deputy Supreme Commander, they saw in this, probably rightly, an attempt to achieve the desired change. The proposal, incidentally, was not supported by Field-Marshal Montgomery. Europe.2

After protracted discussion the Combined Chiefs of Staff disposed of the problem by somewhat amending General Eisenhower’s draft plan of operations. The amendments were slight, but in accepting them General Eisenhower gave assurances intended to satisfy the British. He telegraphed from Versailles to his Chief of Staff (Lieut.-General W. Bedell Smith) at Malta:3

You may assure the Combined Chiefs of Staff in my name that I will seize the Rhine crossings in the north just as soon as this is a feasible operation and without waiting to close the Rhine throughout its length. Further, I will advance across the Rhine in the north with maximum strength and complete determination immediately the situation in the south allows me to collect necessary forces and do this without incurring unreasonable risks.

There remained the further problem of co-ordinating Allied plans for crossing the Rhine with Russian intentions on the eastern front. British and American leaders agreed that the Red Army’s help was indispensable to quick progress in the west. At the Yalta Conference (4-10 February), Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin and their advisers explored means of achieving effective co-ordination, Stalin pointing out that, on previous occasions, synchronization of operations on the eastern and western fronts had seldom proved possible. It was, however, apparent that

none of the Allied leaders expected the German war to end before 1 July 1945,4 and this may have been a factor in the failure to agree on detailed plans for co-ordinated offensives on both fronts during the spring.

The Western Allies described their plan for crossing the Rhine, and Stalin in reply commented on the need for overwhelming resources of tanks and artillery. But when Brooke pressed for details of Soviet intentions during the spring, General Antonov (Deputy Chief of Staff, Red Army) replied merely,5

The Soviet forces would press forward until hampered by weather. With regard to the summer offensive, it would be difficult to give exact data with regard to the interval between the end of winter and beginning of the summer attack. The most difficult season from the point of view of weather was the second part of March and the month of April. This period was that when the roads became impassable.

The Russians did, however, agree to take whatever action they could to assist Allied operations in the west. When Marshall pointed out that the critical period of the assaults across the Rhine would occur between the winter and summer offensives, Antonov assured him that the Soviets would do everything possible to prevent the Germans shifting troops from east to west at that time. The Russians also agreed to exchange information on river-crossing techniques and equipment. But agreement over other aspects of liaison, affecting operations on land and in the air, was more elusive.6

The 1st Corps Arrives from Italy

The discussions at Malta had a very important consequence for the First Canadian Army: the withdrawal of the 1st Canadian Corps from Italy and its reunion with the main body of the Canadian field force in North-West Europe.

The story is told in an earlier volume of this series* and need not be repeated at length here. The 1st Canadian Corps had been sent to the Mediterranean as the result of urgent representations by the Canadian Government; yet that government expressed a desire for its return in an instruction to General Crerar drafted even before it had fought its first battle, as a corps, in Italy (above, page 43, and Appendix A). Thereafter the matter was kept before the United Kingdom authorities. At Malta the required opportunity arose. The British Chiefs of Staff now took the view that “the right course of action was to reinforce the decisive western front at the expense of the Mediterranean Theatre”,7 and the Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed to withdraw “up to five” Canadian and British divisions forthwith.8 Arrangements were made to move the 1st Canadian Corps at once. The 5th Canadian Armoured Division began to arrive in Belgium in the last days of February; the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade was there by mid-March, and at noon on 3 April the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, concentrated in the Reichswald Forest, came under General Simonds’ command. The great move, known as Operation GOLDFLAKE, had involved a sea voyage from Leghorn to Marseilles and a long drive in mechanical transport up the Rhone valley. It had been carried out with admirable dispatch.9

* Nicholson, The Canadians in Italy, 656-66.

Thus an important milestone was passed. All the Canadians were to be together for the last few weeks’ fighting. First Canadian Army, in which as we have seen Canadian formations had frequently been a minority, would now be more truly Canadian than ever before. The reunion was a source of satisfaction throughout the Army, and to no one more than the veterans from Italy.

Planning Operation PLUNDER

While the First Canadian and Ninth United States Armies were heavily engaged in the Rhineland, the Second British Army was preparing for the northern crossing of the Rhine. Even before VERITABLE began, General Dempsey’s Headquarters had produced a detailed study of the projected operation, which was known by the code name PLUNDER. Its object was defined as “to isolate the northern and eastern faces of the Ruhr from the rest of Germany”. The most suitable crossing areas were believed to be Rheinberg, Xanten, Rees and Emmerich—although the last-named might be “too hazardous owing to the difficulties of crossing the Alter Rhein (west of the River Rhine proper) under observation from enemy fire from the Hoch Elten high ground [north-west of Emmerich] and because of the wide flood plains and poor approaches in this area”. If an amphibious attack could not be launched against Emmerich, it would be necessary to seize the town and the Hoch Elten feature from the landward side. Alternative groupings for the assault were considered: either two British corps; each with a single division “up”, or one corps on a two-division front.10 The target-date for PLUNDER remained uncertain at this stage, awaiting developments in the battle for the Rhineland.

In mid-February a directive issued by Headquarters 21st Army Group11 set a provisional target-date of 31 March for PLUNDER. Increased emphasis was laid on the necessity of capturing both the important communications centre of Wesel and industrial Emmerich during the early stages of the operation. The Ninth United States Army would be responsible for the Rheinberg crossing, while the Second British Army would control the crossings at Xanten and Rees. The instruction added, with respect to the proposed assault at Emmerich:

A raid may be mounted by [First] Canadian Army simultaneously with, and as a diversion for, the main crossing of the Rhine. Such a raid will only be executed if opposition is judged to be light and if equipment for it can be made available without prejudice to the main crossings further south.

First Canadian Army was also instructed to study the possibilities of a secondary operation across the Lek,* taking advantage of any weakening of German forces in the Arnhem area, to assist in opening a route through Emmerich.

Early in March the target-date for PLUNDER was advanced to the 24th.12 On the 9th Field-Marshal Montgomery held a conference with his army commanders in which he outlined the forthcoming operation;13 and the same day he issued his detailed “Orders for the Battle of the Rhine”.14 The intention, he wrote, was “To cross the Rhine north of the Ruhr and secure a firm bridgehead, with a view to developing operations to isolate the Ruhr and to penetrate deeper into Germany”.

* The Lek is the Dutch name for the lower reaches of the Neder Rijn; presumably however the directive was intended to refer to the Neder Rijn proper.

Assaulting between Rheinberg and Rees (with the Ninth and Second Armies right and left, respectively), he planned to seize Wesel first, thereafter expanding the lodgement area northwards so the Rhine could be bridged at Emmerich. When First Canadian Army joined the remainder of his command east of the Rhine in the second phase Montgomery anticipated that “further operations deeper into Germany” could be “developed quickly in any direction as may be ordered by Supreme HQ.”

To First Canadian Army the Commander-in-Chief assigned limited tasks for the first phase of operations:

a. to hold securely the line of the Rhine and the Meuse from Emmerich westwards to the sea.

b. to ensure the absolute security of the bridgehead over the Rhine [Waal] at Nijmegen.”

Special measures were also necessary to safeguard the port of Antwerp—“about the only place in which successful enemy operations could throw us off our balance”—with particular attention to the islands north of the Scheldt Estuary. During the initial phase, the Army was to prepare to bridge the Rhine at Emmerich and to take “command of the bridgehead to the north and northwest of that place” when ordered by Montgomery. In the second phase, while the Ninth and Second Armies drove on to seize the line Hamm-Münster-Hengelo, Canadian operations would be designed to

a. attack the Ijssel defences from the rear, i.e. from the east.

b. capture Deventer and Zutphen.

c. cross the Ijssel and capture Apeldoorn and the high ground between that place and Arnhem.

d. bridge the river [Neder Rijn] at Arnhem and open up a good communication and supply route from Nijmegen, northwards through Arnhem, and thence to the north-east.”

General Crerar immediately issued instructions15 for the 2nd Canadian Corps to plan (a), (b), and (c), while the 1st Canadian Corps prepared to secure a bridgehead across the Neder Rijn and capture Arnhem.

Although First Canadian Army as such was not directly concerned in the assault phase of PLUNDER, Canada was to be represented in the Rhine crossing by the 9th Infantry Brigade—the “Highland Brigade”—of the 3rd Canadian Division. This brigade would be the spearhead of a rapid build-up of Canadian forces east of the river, initially under British command. Whereas in VERITABLE the 30th British Corps had played a leading part under First Canadian Army, in PLUNDER the 2nd Canadian Corps would have a role under Second Army. On 11 March, General Simonds’ headquarters came under General Dempsey for planning purposes only; the 2nd Corps passed under the complete operational command of ‘Second Army on the 20th.16 Simultaneously, the 3rd Canadian Division was placed under Headquarters 30th British Corps.*17 The 9th Brigade passed, appropriately, to Major-General T. G. Rennie’s 51st (Highland) Division.

* On 22 March Major-General D. C. Spry relinquished command of the 3rd Division on being appointed to command the Canadian Reinforcement Units in England, an appointment for which General Crerar had recommended him on 6 March. Major-General R. H. Keener took over the vision.

The Second Army was to cross the Rhine between Wesel and the western outskirts of Rees with the 12th Corps on the right and the 30th on the left. General Horrocks’ Corps was to capture Rees and Haldern, and establish a lodgement deep enough to permit bridges to be built. This assault was to be carried out by the Highland Division on a two-brigade front, the 9th Canadian Brigade having a “follow-up” role immediately behind the 154th Brigade on the left. The Canadians’ task would be to thrust towards Emmerich, securing control of the area Vrasselt–Praest–Dornick, as a preliminary to further operations by the 3rd Canadian Division directed against Emmerich. Alternatively, the Canadian brigade might be required to capture Millingen.18

The Army plan included vital missions for specialized troops. The 1st Commando Brigade was to assault Wesel immediately after heavy bombing by the RAF19 Airborne forces were given their third important task of the campaign: under the code name VARSITY, the 18th United States Airborne Corps (comprising the 6th British and 17th US Airborne Divisions) would drop on important ground east of the Rhine, help to disrupt the defence of the Wesel sector and assist General Dempsey’s operations in the bridgehead. The 6th Airborne Division, which still included the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion as part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, was to capture the village of Hamminkeln, the high ground at Schneppenberg in the north-west corner of Diersfordt Wood and bridges over the Issel River nearby. This time the airborne attack was to follow, instead of preceding, the assault by ground forces. Moreover, profiting by the experience at Arnhem, the commanders decided to land smaller tactical groups on or near the objectives (rather than attempt massed landings at a distance) and to land formations complete in one operation.20 Looking to the possibility of bad weather interfering with VARSITY, some consideration was given to alternative plans by which the airborne troops would be dropped farther east if it should be decided to proceed with the first assault without them.21

PLUNDER would be supported by extensive aerial and artillery bombardment. Only the main features of the air plan need be described here. Long before the amphibious assault took place Allied aircraft had been engaged in an interdiction programme designed to help seal off the Ruhr from the remainder of Germany. Sustained attacks against communications and transportation centres continued until the eve of the assault; during the first three weeks of March heavy and medium bombers of the RAF and USAAF dropped 31,635 tons of bombs on the transportation system within the Ruhr. Immediately before and during the PLUNDER D Day assault, Eighth Air Force bombers and Nos. 83 and 84 Groups RAF and the Ninth Tactical Air Command USAAF combined to neutralize German airfields, anti-aircraft sites and other gun positions which might interfere with the crossing of the Rhine. In the British sector, particular attention was devoted to Wesel. These activities were supplemented on D Day by close support of the amphibious and airborne attacks.22

While the Air Forces pounded German installations, Allied gunners prepared to deliver a massive bombardment from the west bank of the Rhine. It is difficult to establish the total number of guns employed on the Army Group front; the Second

Army calculated that a grand total of 3411 (including 853 anti-tank guns and 1038 antiaircraft guns and rocket projectors) supported its five corps, of which the 18th US Airborne Corps was one.*23 The resources directly under the artillery commander of the 30th Corps included the divisional artilleries of the Guards and 11th Armoured Divisions and the 3rd British, 3rd Canadian, 43rd (Wessex) and 51st (Highland) Infantry Divisions, as well as three Army Groups Royal Artillery (including the 2nd Canadian) and the 30th Corps Troops Royal Artillery. The fire plan included counter-battery preparation, to prevent the enemy shelling our forming-up areas and crossing places, counter-mortar tasks, a preliminary bombardment to lower the defenders’ morale (in which the 4th Canadian Armoured Division’s artillery took part), harassing fire and a smokescreen. Artillery of the 2nd Canadian Corps, not otherwise allocated, participated in a diversionary fire plan.24

The Watch on the Rhine

The fierce battles west of the Rhine, we have said, had virtually settled the result of PLUNDER in advance. German reserves of men and equipment had been exhausted and, in the words of British Intelligence, Kesselring, taking over Rundstedt’s command, had “inherited a bankrupt estate”.25 Nevertheless, as we have seen (above, page 509) the Germans had taken some steps at the end of February to organize defences east of the Rhine; and there were many signs that they had profited from the fortnight’s interval between the end of fighting in the Rhineland and the beginning of PLUNDER.

The First Parachute Army held the east bank of the Rhine from Emmerich on the right up to Krefeld on the left. On the 21st Army Group front the 2nd Parachute Corps occupied a sector between Emmerich and a point nearly opposite Xanten, with the 86th Corps on its left covering Wesel. In Army Group H Reserve, north-east of Emmerich, was the 47th Panzer Corps, with its headquarters at Silvolde and the 15th Panzer Grenadier and 116th Panzer Divisions still under command. If these formations had been up to strength, fully equipped and imbued with high morale, they would have been a formidable threat to PLUNDER. But in actuality reinforcements, when available, were untrained; ammunition was desperately short; and troops and commanders alike lacked confidence. Exact figures are not available, but it appears that the total strength of the 2nd Parachute Corps was not much above 12,000—or less than the authorized strength (16,000) of a single parachute division. The Corps Commander (Meindl) afterwards estimated that he had only 80 field and medium guns and 12 assault guns to meet the Allied attack; but he had in addition some 60 88-millimetre anti-aircraft equipments which could be used in a ground role. General von Lüttwitz claims that the two

* By way of comparison, Montgomery used 980 guns at El Alamein; 1060 “of all kinds” supported the Eighth Army in the Liri Valley; and 1034 (excluding anti-tank and certain anti-aircraft guns) fired in VERITABLE (above, page 467). The Ninth US Army history states that 2070 guns supported that Army in “plunder”; apparently this included tank, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. The 21st Army Group calculated that Ninth Army’s assaulting corps was supported by 624 guns of 25-pounder or larger size.

divisions of his 47th Panzer Corps had only 35 tanks between them.26 Hitler’s earlier refusal to permit the construction of defences on the east bank of the Rhine had merely served further to depress the morale of his troops in their most critical hour. Moreover, the Germans had had no time to organize their defences in depth; they were only able to build a narrow belt of rifle and machine-gun pits along the river, focussing their attention on probable crossing sites. This pattern had been anticipated by Allied planners.27

German commanders have maintained that they foresaw the course of Allied operations on the Lower Rhine. Kesselring writes: “The enemy’s air operations in a clearly limited area, bombing raids on headquarters, and the smoke-screening and assembly of bridging material indicated the enemy’s intention to attack between Emmerich and Dinslaken, with point of main effort on either side of Rees.” However, General Schlemm, commanding the First Parachute Army, suggested that there was some lack of unanimity in the higher headquarters over the precise point of expected attack. Basing his opinion on the topography suitable for Allied airborne landings, Schlemm expected the main effort at Wesel, while some of his superiors evidently inclined to the view that the northern crossing would take place near Emmerich, or even at Arnhem.28

The Crossing of the Rhine: The Assault

Before Montgomery’s assault was launched, we have seen, the Allies had already crossed the Rhine elsewhere. The First United States Army was exploiting its Remagen bridgehead in the direction of the Sieg River. Farther south, above Mainz, General Patton beat Montgomery to the east bank by nearly a day (above, page 524). But Montgomery’s bridgehead, in accordance with the decision of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, remained the point of main effort. There was also a significant difference between German opposition in the south and in the north; as the Supreme Commander afterwards observed, “the northern operation was made in the teeth of the greatest resistance the enemy could provide anywhere along the long river”.29

The amphibious phase of PLUNDER began at 9:00 p.m. on 23 March after heavy bombardments by Allied aircraft and artillery. “Pepper Pots” similar to those used at the beginning of VERITABLE (above, page 467) helped to neutralize German defences. The expenditure of ammunition was enormous: in less than two hours, two batteries of the 4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment RCA fired 13,896 rounds on “Pepper Pot” tasks. (This unit also gave directional tracer fire with one Bofors to mark the left flank of the Highland Division’s assault.) The 1st Rocket Battery RCA supported the same division’s attack. The preliminary bombardment undoubtedly softened the German resistance. The enemy’s artillery could reply only sporadically, and retaliation from the Hoch Elten feature was described as “practically negligible”, little more than “light harassing fire”.30

As the assaulting troops moved forward to cross the 500 yards of swift water their movements were carefully controlled by a “Bank Group” organization. It ensured that crossings were made according to priorities and that undue congestion

was avoided at points of embarkation. From marshalling areas in the rear troops moved forward to the “Buffaloes”, stormboats, DUKWs and ferries which carried them across the Rhine. Navigation was assisted by “Tabby” lights, invisible unless seen through special glasses. On the far bank of the river another headquarters directed the craft-loads of troops to forward assembly areas, where units rejoined their formations as required.31 The work of the “Bank Group” organization was unquestionably a major factor in the success of the assault.

Two other aspects of the crossing deserve mention: the use of DD (amphibious) tanks, and the employment of Force U of the Royal Navy. The tanks followed the leading infantry, with a view to being available to give prompt support in the bridgehead.32 No Canadian tanks swam the Rhine. Naval Force U, under Captain P. H. G. James, RN, was organized in three squadrons, each consisting of one flotilla of Landing Craft, Mechanized, and one flotilla of Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel. These craft, some of which were 50 feet long, were brought overland from Antwerp to Nijmegen with the intention of using them to ferry troops and vehicles across the Rhine. Twenty-four LCV(P) and 24 LCM were allotted to Second British Army, while 12 of each came under the control of First Canadian Army for the use of the 2nd Corps during PLUNDER.33 However, other amphibious arrangements proved so successful that, during the initial attack, the craft were mainly used for patrolling and assisting in the erection of bridges.34 As we shall see, the LCMs afterwards made an effective contribution to the capture of Arnhem by the 1st Canadian Corps.

The attack across the great river could have been a very bloody operation. But in the actual circumstances existing on 23 March 1945 it was no such thing. Only six minutes after the Highland Division launched its attack west of Rees on the 30th Corps front, the leading wave reported its arrival on the far bank. The first really stiff opposition was met a mile and a half inland, at Speldrop. The Scots were supported by DD tanks of The Staffordshire Yeomanry (Queen’s Own Royal Regiment), which had three tanks sunk during the crossing.35 Rees was soon outflanked and the bridgehead rapidly expanded. Meanwhile, on the front of Lieut.-General N. M. Ritchie’s 12th British Corps on the right, the 1st Commando Brigade established itself immediately west of Wesel, beginning its crossing at 10:00 p.m. At 10:30, 201 aircraft of the RAF Bomber Command began a brief pulverizing assault on the town in which nearly 1100 tons of high explosive were dropped. The Commando Brigade then moved in. Even in these circumstances there was some fierce fighting before Wesel was clear.36 In the early hours of 24 March the 15th (Scottish) Division attacked between Wesel and Rees and also secured its initial objectives, against spotty opposition.* Simultaneously, formations of the Ninth United States Army crossed the Rhine south of Wesel and quickly overran the enemy’s forward lines.37

The climax of these complicated operations occurred about ten o’clock on the morning of the 24th, when Allied airborne soldiers came down from clear skies

* The able General Schlemm had been badly wounded when his headquarters was accurately hit by Allied aircraft on (he says) 21 March. General Gunther Blumentritt subsequently took over First Parachute Army.

Sketch 42: Operation VARSITY, Showing Situation 6th Airborne Division, Afternoon 24 March 1945

upon the hazy battlefield east of the Rhine. VARSITY drew together, with remarkable precision, parachutists and glider-borne troops from widely-separated bases in France and the United Kingdom. They were lifted by 1589 paratroop aircraft and 1337 gliders. A great force of British and American fighters provided escort and cover. There was virtually no enemy opposition in the air, but light antiaircraft guns made trouble, particularly about the British glider landing zones around Hamminkeln. Poor visibility at low altitudes made exact navigation difficult and hampered supporting fighter-bombers. Nevertheless, as early as noon, it was evident that VARSITY was a success. The 17th United States Airborne Division then held positions east of Diersfordt and Isselrott, while farther north the 6th British Airborne Division was firmly established on its objectives.38

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion landed with the rest of the 3rd Parachute Brigade just north of Diersfordt Wood. The unit’s war diary complained that the men were “widely spread” due to the speed of the aircraft, adding, “Flak was fairly heavy over the Dropping Zone and several aircraft were seen to go down in flames.” On landing, the Canadians met severe machine-gun and sniper fire; but they had cleared their objectives at the north end of the Schneppenberg “feature” by 11:30 a.m. Prisoners “constituted quite a problem because they numbered almost the strength of the battalion”; and “Germans were killed by the hundreds”. The battalion’s own casualties were 23 killed (including the Commanding Officer, Lt.-Col. J. A. Nicklin, whose body was later found hanging from a tree in his parachute), 40 wounded and two prisoners of war.39

During this fighting one of the battalion’s medical orderlies, Corporal F. G. Topham won the fourth Victoria Cross awarded to a Canadian during the campaign. As he treated casualties after the drop, Topham heard a cry for help from a wounded man in the open. The recommendation for the decoration continues:

Two medical orderlies from a field ambulance went out to this man in succession but both were killed as they knelt beside the casualty. Without hesitation and on his own initiative Corporal Topham went forward through intense fire to replace the orderlies who had been killed before his eyes. As he worked on the wounded man, he was himself shot through the nose. In spite of severe bleeding and intense pain he never faltered in his task. Having completed immediate first aid, he carried the wounded man steadily and slowly back through continuous fire to the shelter of the woods.

Refusing assistance for his own wound, he continued to perform his duties for two hours, until all casualties had been evacuated from the area, Then, having successfully fully resisted orders for his own removal, he rescued three men from a burning carrier at great risk from exploding ammunition. His heroic conduct serves to emphasize the great debt owed by the Army to its medical services.*

The 9th Brigade Beyond the Rhine

At 4:25 on the morning of 24 March the four rifle companies of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (Lt.-Col. P. W. Strickland) began crossing the Rhine in Buffaloes under “sporadic shelling”. The HLI, fighting in this phase under the

* It may be noted that unit medical orderlies were not members of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps.

154th Brigade, was the first Canadian unit across. On the farther bank guides led it to an assembly area north-west of Rees. The 154th Brigade, we have seen, had met stiff resistance at Speldrop (the Highland Division’s commander, General Rennie, was killed in the brigade area during the morning)* and the Canadians were ordered to capture the village. Some parties of the Black Watch were still cut off and surrounded in Speldrop when, in the late afternoon, the Highland Light Infantry advanced against the outskirts. The defending paratroops fought fiercely, but the assault was pressed with determination over open ground, valuable supporting fire being provided by six field and two medium regiments and two 7.2-inch batteries.40 Within the village the enemy held out desperately in fortified houses, which could only be reduced by “Wasp” flame-throwers and concentrations of artillery fire.

The battle continued well on into the morning [of the 25th]. Houses had to be cleared at the point of the bayonet and single Germans made suicidal attempts to break up our attacks. ... It was necessary to push right through the town and drive the enemy out into fields where they could be dealt with.41

The HLI relieved the trapped detachments of the Black Watch and put out the last embers of resistance. Their casualties during the two days’ fighting were, for the circumstances, light: 33, including ten killed.42

Meanwhile, on the afternoon of the 24th, the remainder of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade had joined their comrades east of the Rhine. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada came back under Brigadier Rockingham and that night his brigade, reinforced by the North Shore Regiment from the 8th, relieved the 154th.43 During the next two days the 9th Brigade struggled to open an exit from the pocket formed by the Alter Rhein northwest of Rees. These operations centred about the villages of Grietherbusch, Bienen and Millingen. While they were in progress, on the afternoon of the 25th, the brigade came under the command of the 43rd (Wessex) Division which was moving into the bridgehead.44 General Horrocks was thus gradually implementing his plan to develop the attack on a three-division front, with the 51st, 43rd and 3rd Canadian Divisions right, centre and left respectively.45

On the left of the whole Allied advance, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders captured Grietherbusch without too much difficulty; but far heavier opposition was encountered at Bienen. There, on the 25th, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders attacked across open ground against very determined defenders. The Canadians had, in fact, drawn in the lottery the area on the British front where resistance was fiercest. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had been put in here from Army Group Reserve to hold the Alter Rhein bottleneck and the important road junction of Bienen.46 Although artillery and medium machine-guns of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG) lent support, the North Nova Scotias were soon pinned down by German automatic weapons and mortars. “The battalion had quite definitely lost the initiative and contact between platoons was next to impossible because of the murderous fire and heavy mortaring.”47 Early in the afternoon General Horrocks visited the Canadian sector

* He was succeeded by Major-General G. H. A. MacMillan, who had previously commanded the 15th (Scottish) and 49th (West Riding) Divisions.

while, with the help of armour and Wasps, Lt.-Col. Forbes mounted a new attack against the village. By the end of the day his men had penetrated the southern portion; but their casualties had been very severe-114, of which 43 were fatal.48 As the North Nova Scotias’ diarist wrote, it had been “a long, hard, bitter fight against excellent troops who were determined to fight to the end”. Helped by a troop of 17-pounder self-propelled guns of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment RCA, The Highland Light Infantry of Canada now took over the task of clearing the rest of Bienen. “Progress was very slow as the enemy fought like madmen.”49 But the HLI were not to be discouraged, and during the morning of the 26th they mopped up the last resistance in the place.50

About a mile north-east of Bienen was Millingen, on the main railway line between Emmerich and Wesel. This village now became the target of The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment. It went in at noon on the 26th, with the support of artillery and armour, and was completely successful, all objectives being secured on the same afternoon; but the day cost the life of its commander, Lt.-Col. J. W. H. Rowley, who was killed by a shell early in the attack.51 Simultaneously The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders cleared the villages to the west of Millingen. The Canadian buildup east of the Rhine continued with the arrival of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, also under the command of the 9th Brigade.52 As the bridgehead was steadily enlarged the remainder of the 3rd Division prepared to follow; on the 27th General Keefler established his tactical headquarters on the right bank while the balance of the 7th Brigade joined the 9th in the bridgehead; and at 5 p.m. he took over the left sector of the 30th Corps line. His last brigade, the 8th, crossed the river on 28 March. At noon that day the 2nd Canadian Corps (still under the Second Army) took the 3rd Canadian Division, and its sector of the bridgehead, under command.53

Beginning the Northern Drive: Emmerich and Hoch Elten

“We have won the Battle of the Rhine”, wrote Field-Marshal Montgomery in a new directive to his Army Commanders on 28 March.54 He intended to exploit the favourable situation rapidly, driving hard for the line of the Elbe “so as to gain quick possession of the plains of northern Germany”.

The Field-Marshal’s “Plan in Outline” as he conceived it at this time may be quoted:

6. To advance to the line of the Elbe with Ninth Army and Second Army.

7. The right of Ninth Army to be directed on Magdeburg; the left of Second Army to be directed on Hamburg.

8. Canadian Army to open up the supply route to the north through Arnhem, and then to operate to clear Northeast Holland, the coastal belt eastwards to the Elbe, and West Holland.

9. Having reached the Elbe, Ninth and Second Armies will halt. Ninth Army will assist 12 Army Group in mopping up the Ruhr.

Second Army will assist Canadian Army in its task of clearing the coastal belt vide para 8.

The large area of Germany occupied by 21 Army Group will be brought under military government.

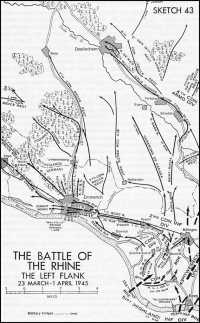

Sketch 43: The Battle of the Rhine, The Left Flank, 23 March–1 April 1945

We shall see (below, page 543) that one assumption on which this programme was based was immediately voided by the Supreme Commander. Montgomery was disappointed in his expectation of retaining the Ninth Army.

As the Canadians moved in an eastward arc along the German coast, their right flank would be echeloned slightly behind the left of Second British Army. To cover the eastern flank of the 2nd Canadian Corps during its advance north of the Rhine Montgomery considered returning the 30th British Corps to General Crerar’s command; but this proved unnecessary. The 1st Canadian Corps might be required to clear the north-western Netherlands; but the Commander-in-Chief hoped to avoid such a diversion from “the main object, which was the complete defeat of the German Armies in Northwest Europe”.55

At the end of March careful consideration was also being given to the problem of an assault crossing of the River Ijssel from east to west-the task assigned to First Canadian Army in Montgomery’s earlier directive. The object, we have seen, was to open a route through Arnhem and Zutphen to maintain forces east of the Rhine and the Ijssel. Although there was little likelihood that the enemy could offer effective opposition along the Ijssel, the river was itself a considerable obstacle, varying in width from 350 to 600 feet with high floodbanks. The problem was also complicated by a temporary shortage of engineering resources. A 21st Army Group proposal to carry out the plan with both Canadian Corps operating east of the Ijssel was considered impracticable by First Canadian Army because of limitations on crossings over the Rhine and routes east of the Ijssel.56 As we shall see, the 2nd Corps actually made the Ijssel crossing in mid-April in conjunction with operations of the 1st Corps west of the river.

Meanwhile preparations for the northern drive continued. General Simonds established his command post near Bienen, where he could direct the 3rd Division during its advance on Emmerich while maintaining contact with the 30th Corps on his right flank.57 The 2nd Canadian Division, which had been resting in the Reichswald, crossed the Rhine on 28-29 March, led by the 6th Brigade, now commanded by Brigadier J. V. Allard. It was to become the spearhead of the 2nd Corps’ northern advance (Operation HAYMAKER), with the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions on its left and right respectively. At the end of the month the 4th Armoured Division joined the force in the bridgehead, the divisional staff being reminded of “the crowded sites of Normandy”.58

Before General Crerar could take control of Canadian operations east of the Rhine it was essential to open a maintenance route across the river at Emmerich. This depended, in turn, on the progress of operations to capture the city and the nearby Hoch Elten ridge. This important job fell to the 3rd Canadian Division. On the night of 27-28 March Brigadier T. G. Gibson’s 7th Infantry Brigade opened the attack on the eastern approaches to Emmerich. The Canadian Scottish quickly captured the village of Vrasselt and pressed on during the night; The Regina Rifle Regiment occupied Dornick the following morning. The units reached the city’s outskirts before they met serious opposition, from units of the 6th Parachute and the 346th Infantry Divisions. General Keefler then ordered the 7th Brigade to continue its attacks to clear Emmerich and a wooded area north of the city while

the 8th Brigade prepared to pass through and attack the Hoch Elten feature. These operations were supported by tanks of the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment) and “Crocodiles” of C Squadron, The Fife and Forfar Yeomanry.59

During the night of 28-29 March the Canadian Scottish experienced what they described as “probably the most vicious fighting of the battle for Emmerich”60 in attempting to expand their bridgehead over the Landwehr Canal. A company of the Regina Rifles assisted in this difficult task and the stubborn enemy was gradually driven back into the city, while our engineers bridged the canal during the darkness. The way was then clear for concerted thrusts into the heart of the built-up area. Emmerich, which had a normal population of about 16,000, had been heavily bombed and was “completely devastated except for one street along which a few buildings were more or less intact”61 (When the 1st Canadian Division passed through Emmerich nine days later it recorded that “only Cassino in Italy looks worse”.)62 On the morning of the 29th the Reginas, supported by tanks and Crocodiles, launched an attack to clear the southern portion of the city. Resistance stiffened as the operation progressed. “Enemy defences consisted mainly of fortified houses and tanks and as each house and building had to be searched progress was slow.” When the troops forced their way into the central area of the city they faced a problem familiar from Normandy and the Channel Ports: “our tanks in support found it almost impossible to manoeuvre due to well-sited road blocks and rubble”.63 While the Reginas cleared the southern part of Emmerich, The Royal Winnipeg Rifles fought steadily through the northern section, beating back a fierce German counter-attack early on the 30th. On that day the Canadian Scottish again became the division’s vanguard, capturing a large cement works on the western outskirts of the city as a start line for the 8th Brigade’s operation. The 7th Brigade completed its task on the following morning. During the previous three days its infantry battalions had suffered 172 casualties, including 44 killed or died of wounds; the heaviest loss fell on the Canadian Scottish.64

The 8th Brigade was now to carry forward the attack and capture the Hoch Elten “feature”. We have already noted the tactical importance of this high wooded ridge some three miles north-west of Emmerich. It dominated our engineers’ Rhine bridging sites and German possession of it might thereby delay the full participation of First Canadian Army in the battle. For this reason the Hoch Elten area had been subjected to particularly severe artillery and air bombardment during the days preceding the attack. These measures had the effect of easing the task of the 8th Brigade when it advanced on the night of 30-31 March. The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and Le Régiment de la Chaudière led the way; the latter, with no doubt some pardonable exaggeration, describes the ground as “peut-être le plus bombardé dans l’histoire de la guerre”65 The enemy’s surviving artillery and mortars fired on the axes of advance but, in general, there was little opposition. On the following night the Chaudière entered the village of Elten, west of the ridge, while the Queen’s Own and the North Shore completed the occupation of the wooded area. Meanwhile, on the 3rd Division’s inland flank, the 9th Brigade had cleared the woods north of Emmerich and the nearby town of ‘s-Heerenberg.66

Elimination of the Germans’ hold on Hoch Elten enabled the engineers to begin construction of a low-level Bailey pontoon bridge—a “Class 40” bridge capable of carrying tanks—across the Rhine at Emmerich. At noon on 31 March the 2nd Canadian Army Troops Engineers began work. They were assisted by various elements of British and Canadian services and a squadron of landing craft from Naval Force U. Although the enemy could not interfere actively with the bridging operation, his minefields on the northern bank (the Rhine flows due west at Emmerich) had to be cleared, and a west wind impeded the manoeuvring of floating bays into position. Nevertheless, “Melville” Bridge, as it was named, in honour of Brigadier J. L. Melville, a former Chief Engineer of First Canadian Army, was opened to traffic at 8:00 p.m. the following day. Its length was 1373 feet, and from the moment it was opened “traffic went over it nose to tail night and day”. Completion of two other bridges at Emmerich soon followed. One was a secondary (Class 15) bridge. The other, named for Brigadier A. T. MacLean, also a former Chief Engineer, was a high-level Bailey pontoon bridge (Class 40) which was built by the 1st Canadian Army Troops Engineers. It was given extended landing ramps in anticipation of further flooding.67 Thus the way was clear for General Crerar to take control of Canadian operations east of the Rhine.

[Reference for the * footnote is missing68]

Strategy for the Final Phase

While the Canadians were fighting down the right bank of the Rhine there was a significant development in Allied strategy.

General Eisenhower had had the considerable pleasure on 26 March of reporting to General Marshall that on the previous day Sir Alan Brooke, in conversation with him on the banks of the Rhine, had conceded that in the late controversy over strategy west of the river (above, pages 527-8) Eisenhower had been right.69 The Supreme Commander now made a decision which had the effect of altering what the British considered to be the agreed strategy for the next phase—expressed in the words “I will advance across the Rhine in the north with maximum strength” in the Supreme Commander’s message to the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Malta (above, page 528). On receiving a copy of Field-Marshal Montgomery’s directive of 28 March (above, page 539), Eisenhower immediately told him that General Bradley’s 12th Army Group was now to make the main offensive east of the Rhine; the Ninth US Army would revert from Montgomery’s command to Bradley’s after the Ruhr was encircled. The strategic task given to Montgomery was reduced to that of protecting Bradley’s left flank, though the Ninth Army was again to be available to him, if required, after the Elbe was reached.70

Eisenhower’s motives at this point are to some extent conjectural. On 15 September 1944, we have seen, he had considered Berlin the great Allied objective, and had envisaged the main thrust as directed from the Ruhr upon the capital (above, page 316). But as early as 11 March the Russians were reported within

* “Melville” was not the first Canadian bridge across the Rhine. On 26-28 March the 2nd Canadian Corps Troops RCE built “Blackfriars” Bridge, a 1814-foot Class 40 low-level Bailey pontoon bridge, one of five bridges constructed across the river in the British area at Rees.

30 miles of Berlin; and it appeared that they were likely to traverse this distance long before the Western Allies could cover 300 miles from the Rhine. Eisenhower explained later that he apprehended that a thrust to Berlin could only be supported by immobilizing formations along the rest of the front. He was anxious to join hands with the Russians as soon as possible and cut Germany in two. Moreover, there was anxiety (which proved to be groundless) over reports that the Germans intended to retreat into a “National Redoubt” in the Austrian Alps.71 SHAEF Intelligence pointed out that these reports were unconfirmed. But far away in Washington General Marshall—to whose suggestions the Supreme Commander was always particularly attentive—urged him on 27 March to consider directing US forces on Linz or Munich to guard against such a development.72

An American official writer has suggested that there may have been other factors, never made explicit. American public opinion could not be disregarded, and Bradley was known still to be fuming over Montgomery’s press interview in January (above, page 450). This doubtless made it difficult for an American commander either to keep large US forces under Montgomery or to give Bradley a role in the final phase subordinate to Montgomery’s.73 And as we have already noted the British position in these controversies was fatally weakened by the relative smallness of the British land forces. Without an American army Montgomery’s army group could not play the leading part which the British Chiefs of Staff desired it to play.

Eisenhower made his offence, as it seemed to the British, still worse by communicating his new intentions direct to the head of the Soviet government and armed forces. He did this with great precipitation*74 and without prior consultation with his British Deputy, the Combined Chiefs of Staff or his American and British political superiors. He told Stalin on 28 March that he intended to make his main thrust on the axis Erfurt-Leipzig-Dresden, and a secondary one on the axis Regensburg-Linz.75 This led to strong protests from the British Prime Minister, who—though his sensitiveness to the possibility of post-war difficulties with Russia at earlier periods has been exaggerated—was now fully seized of the problem. He wrote to President Roosevelt on 1 April, “The Russian armies will no doubt overrun all Austria and enter Vienna. If they also take Berlin will not their impression that they have been the overwhelming contributor to our common victory be unduly imprinted in their minds, and may this not lead them into a mood which will raise grave and formidable difficulties in the future? I therefore consider that from a political standpoint we should march as far east into Germany as possible. ...”76

It appears now to be a general opinion—not least in the United States77—that this would have been the statesmanlike course. But at the time Mr. Churchill’s representations met only stony refusals from the American leaders. President Roosevelt was already an ailing man (he was to die on 12 April) and General Marshall was apparently acting for him in military matters. Marshall’s view of

* The full text of the communications has not been published; but everything happened on 28 March, the day on which Montgomery issued his new directive. (He appears however to have given Eisenhower advance notice of it on the 27th.) A possible interpretation is that Montgomery’s action nettled Eisenhower, that he immediately informed Montgomery of his decision, and that he simultaneously sent his telegram to Stalin—perhaps, an American author has plausibly suggested, with a view to making it impossible for the decision to be changed.

such questions is reflected in a telegram he sent to Eisenhower on 28 April, in connection with a British suggestion that great political advantages would accrue to the Western powers if they, and not the Russians, liberated Prague: “Personally and aside from all logistic, tactical or strategical implications I would be loath to hazard American lives for purely political purposes.”78 It would almost seem that in the heat of argument some of the protagonists had temporarily lost sight of the fact that it is not for military objects that wars are fought.

At the end of March 1945 the war was virtually won, and a good peace and future international stability were far more important considerations than the immediate military situation. In these circumstances political leadership should have dictated their action to the military commanders. It was a singular misfortune that at this crisis there was virtually no political leadership in the United States. The policies of Eisenhower were fully sustained by Washington in spite of all British protests; his attitude that Berlin was “no longer a particularly important objective”79 was accepted; and the Russians were allowed to capture the German capital, and occupy that of Czechoslovakia, without any Western attempt to anticipate them.

While this argument, so peculiar in retrospect, was going on between their chiefs, the soldiers on the Western Front achieved another great success. On 1 April the Ninth US Army made contact with the First at Lippstadt, and the Ruhr was encircled. This meant more than the separation of Germany’s greatest industrial area from the rest of the country: virtually the whole of Army Group B, with the Fifth Panzer and Fifteenth Armies, was surrounded. The liquidation of the great pocket now proceeded in the face of only moderate resistance. It was cut in two on 8 April. On the 18th organized resistance here ended. Over 317,000 prisoners had then been taken in the pocket. Field-Marshal Model, the Army Group Commander, is believed to have committed suicide.80 Nazi Germany was rapidly falling apart.

The Re-Entry of First Canadian Army

At one minute before midnight of 1-2 April Headquarters First Canadian Army took control of the 2nd Canadian Corps’ operations east of the Rhine. At noon that day General Crocker’s 1st British Corps had returned to General Dempsey’s command.81 It had served continuously under General Crerar since the memorable days in Normandy, and the severance of this long and honourable association caused regret. On the other hand, it was a source of satisfaction to have General Foulkes’ 1st Canadian Corps now under the Army in the Arnhem sector. The Corps Headquarters had arrived from Italy early in March, and had come under General Crerar at midday on the 15th of the month, in the first instance with only the 49th (West Riding) Division under command.82 The new boundary between First Canadian and Second British Armies ran north from Terborg (some nine

* It should be noted that, since zones of occupation had already been agreed upon, an advance to Berlin or Prague by the Western powers would have had to be followed by a withdrawal in due course.

miles north-east of Emmerich) to Zelhem and then swung through Ruurlo, Borculo, Neede and Delden to Borne.83

General Crerar issued a new directive to his Corps Commanders on 2 April.84 General Simonds was to continue his northward advance with a view to forcing the Ijssel south of Deventer and making good the line Apeldoorn–Otterloo. Simultaneously, General Foulkes would enlarge the “island” south of the Neder Rijn, secure a bridgehead over that river west of Arnhem and proceed to capture Arnhem. In succeeding phases, Simonds, having secured the line Almelo-Deventer, would clear the north-eastern Netherlands, while Foulkes might be required to deal with the German forces in the western Netherlands. The Army Commander wrote:

Should it be decided that the clearing of West Holland by 1 Canadian Corps is not to be undertaken, then First Canadian Army will regroup on a two Corps front, and advance into Germany between the inter-Army boundary capturing, Right [wit forces Second British Army], and the sea on its Left, destroying, or capturing, all enemy forces as it proceeds.

Throughout the operations outlined the 2nd Corps would have “a prior claim” upon the Army’s resources and the support of No. 84 Group RAF

The 2nd Corps’ northern advance had already gathered momentum. After concentrating in the Bienen-Millingen area, the 2nd Division moved forward on the 3rd Division’s right, recrossing the Dutch-German frontier and clearing Netterden on 30 March. In general, “scattered clusters” of opposition were reported, with only token resistance in certain sectors.85 While the 3rd Division was capturing the Hoch Elten feature, General Matthews’ troops thrust forward to Etten, seven miles north-east of Emmerich, with the Wessex Division temporarily on their right flank. The 4th Canadian Armoured Division moved in here on 1 April. General Vokes’ immediate task was to occupy the Lochem–Ruurlo area and then press on across the Twente Canal to Delden and Borne.86

As our formations fanned out east of the Ijssel-Rhine junction, German disorganization facilitated rapid advance. It soon became apparent that apart from Zutphen, which was well protected by water lines connected with the Ijssel, the enemy’s next natural defence line would be the Twente Canal. This ran eastward from the Ijssel north of Zutphen, past Lochem and through the southern outskirts of Hengelo to Enschede, roughly at right angles to the axes of the 2nd Corps. Defending the main portion of the Canal as far east as Hengelo was our old antagonist the 6th Parachute Division. East of the Rhine the division had been reinforced by replacement and training units, together with the 31st Reserve Parachute Regiment; the latter consisted of three battalions, one of which was an artillery unit armed with ordnance of various calibres. On the eve of the Canadian attack Plocher was also reinforced by a “Police Regiment” of doubtful quality.87

Pressing forward through Doetinchem and Vorden, the 2nd Canadian Division was first to cross the Twente Canal. On the night of 2-3 April the 4th Infantry Brigade made the assault near Almen, four miles east of Zutphen. The speed of the attack, following a rapid 20-mile advance, caught the enemy napping. Although the Germans had blown the bridges over the Canal, their defences were still disorganized.

When The Royal Regiment of Canada crossed in assault boats, their first prisoners were mainly engineers, busy preparing positions for infantry who arrived too late to oppose the crossing. Our own engineers quickly began work on a ferry, while a company of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry reinforced the bridgehead. About midnight the enemy reacted vigorously, beginning “a most intense mortaring and shelling of the proposed ferry site” and temporarily stopping the engineers’ work.88 Nevertheless, they soon had rafts operating across the Canal and, during the next day, these carried armoured cars of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), self-propelled guns of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment RCA, and tanks of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse) to the infantry’s support. The Germans mistakenly believed that the Canadians used amphibious tanks.89 Although the enemy launched spasmodic counterattacks, and continued to interfere with bridging and rafting, the bridgehead was consolidated and expanded on 3 April. At the end of the day The Essex Scottish Regiment was preparing to join the remainder of the brigade north of the Canal and the way was clear for the 5th Brigade to continue the northern drive. The 4th Brigade’s losses had been comparatively light.90 Meanwhile, the 6th Brigade had eliminated resistance on the left flank, closer to the Ijssel River.

The casualties inflicted on the Wehrmacht in earlier battles were obviously having a significant effect. The 4th Brigade noted,91

The enemy tactics appear almost juvenile at times—he is doing everything the book says as usual, but his training here shows that the calibre of troops opposing us is not what it used to be. Each enemy attack suffered very heavy casualties and usually a number of PW [were] taken-grubby, dirty, slender youths, boys and old men.

Although further German resistance was rapidly becoming meaningless, fierce struggles would continue in isolated sectors until the disintegration was complete.

Just west of Delden, 20 miles east of the 2nd Division’s crossing, the 4th Armoured Division carved out a second bridgehead across the Twente. On 2 April General Vokes’ tanks and motorized infantry had reached the canal at Lochem, relieving a formation of the Wessex Division, but found no suitable crossing site.92 The enemy held the far bank in some strength, inflicting casualties on our troops. Then, on the evening of the 3rd, Lt.-Col. R. C. Coleman’s Lincoln and Welland Regiment (fighting under the 4th Armoured Brigade) threw two companies across the canal and a company of The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) made a diversionary attack against lock-gates about 1000 yards west of the main crossing. After indulging in “scattered sniping and small arms fire” throughout the day, the enemy was able to direct only “moderate machine-gun and mortar fire”93 against the assault. Counter-attacks were beaten off by our infantry with the help of the divisional artillery and the bridgehead was secured. Again the pressing problem was one of bridging: it was essential to construct quickly a bridge that would carry the heavy vehicles of the 4th Armoured Brigade. Fortunately, the Lake Superior Regiment discovered at the lock-gates a 30-foot gap which could be bridged. Initially there had been no intention of bridging there, but. now the 9th Field Squadron RCE was sent in and in two hours and a quarter the bridge was built and the brigade began to roll across. The brunt of the operations on 3-4 April

fell on The Lincoln and Welland Regiment, which suffered 67 casualties.94

Opposition now lessening, our troops occupied Delden and pushed on through Borne to the important communications centre of Almelo, eight miles north of the canal. On 4-5 April units of the 4th Armoured Brigade cleared snipers out of this town amid the rejoicings of its people. Other elements of the 4th Division were already beyond the town, driving on across the German frontier towards the Ems River at Meppen.95

Zutphen and Deventer

On 5 April Field-Marshal Montgomery issued a new directive.96 He noted that the Ninth US Army had been withdrawn from his command at midnight on 3-4 April and had passed to the 12th Army Group; this had “definite repercussions” on the operations of his own army group, and his orders of 28 March (above, page 539) required modification accordingly.

The new instructions ordered the Second Army to “operate to secure the line of the Weser within the Army boundaries” and to capture Bremen. It was then to seize bridgeheads over the Weser, Aller and Leine and be prepared to advance to the Elbe and establish bridgeheads over it. As for First Canadian Army, it was to carry out the tasks prescribed for it on 9 March (above, page 531):

11. One Corps, of at least two Divisions, will then operate westwards to clear up western Holland. This may take some time; it will proceed methodically until completed. See para 14.

12. Simultaneously with the clearing of western Holland, the remainder of Canadian Army will operate northwards to clear northeast Holland, and then eastwards to clear the coastal belt and all enemy naval establishments up to the line of the Weser. During these operations Canadian Army will operate with one armoured division on the axis Almelo–Neuenhaus–Meppen–Sogel–Friesoythe–Oldenburg, so as to afford a measure of security to the left flank of Second Army.

13. Having cleared Northeast Holland and the coastal belt, as outlined in para 12, Canadian Army will he prepared to take over Bremen from Second Army to operate eastwards on the Hamburg axis. It will have the task of protecting the left flank of Second Army in the advance to the Elbe, and of clearing the Cuxhaven peninsula.

14. In the operations of Canadian Army the available resources in engineers, bridging equipment, etc, may not be sufficient for all purposes. In this case the operations vide para 12 and 13 will take priority; the clearing of western Holland will take second priority.

While General Simonds’ centre and right flank were making rapid progress north of the Twente Canal the 3rd Canadian Division, on his left sector, was preparing to capture Zutphen and Deventer. Advancing steadily northward from the Hoch Elten area, it had cleared the right bank of the Ijssel, meeting light opposition at Wehl on 2 April. Since, at this time, the flanking 2nd Division was in the lead, Simonds instructed that formation to “tap out and, if opposition not heavy, capture Zutphen”.97 But the enemy’s evident intention to hold the town, and the 2nd Division’s rapid progress north of the Twente Canal, soon made it necessary for the 3rd Division to take on Zutphen. While the 8th Infantry Brigade contained Doesburg, and the 7th cleared the western end of the Twente on 5 April, the 9th Brigade closed in on the southern

Sketch 44: Zutphen and Deventer, 5–12 April 1945

and eastern approaches to Zutphen. This sector was defended by the 361st Infantry Division of the 88th Corps,* with a parachute training battalion under command.98 These troops, many of them “teen-aged youngsters”,99 fought very fiercely. The 9th Brigade encountered stiff resistance at Baronsbergen and Warnsveld, on the outskirts of the town, which was covered by old water defences connected with the Ijssel. To pass one drainage ditch the pioneer platoon of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada built a bridge “with 4.2” mortar boxes, reinforced with timber and ballast”—and it proved strong enough to carry the supporting tanks of A Squadron of the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment).100

Having secured the approaches to the town, the 9th Brigade was withdrawn on 7 April to add momentum to the drive north of the Twente and the 8th continued the operations to reduce Zutphen. It had launched its attack on the 6th, developing a two-pronged thrust into the town from the east with the North Shore Regiment on the right and Le Régiment de la Chaudière on the left. The North Shore ran into heavy opposition, with hand-to-hand fighting, but the Chaudière were able to make good progress. Accordingly, the plan was changed, the North Shore being withdrawn to pass through the right flank of the Chaudière. Fighting continued on the 7th. Sometimes our infantry were pinned down by snipers and machine-gun fire. Nevertheless, as in the operations on the Twente Canal, “for the first time there was evidence that the enemy’s attitude was gradually changing and although he fought well at times, the old tenacity was lacking”.101 The coup de grâce was given on the morning of the 8th, when the brigade penetrated the factory area with the help of Crocodiles. By midday the historic old town had been completely cleared, some of the defenders escaping across the Ijssel in rubber boats.102

As the 8th Brigade was completing its work at Zutphen, the 9th was establishing a bridgehead across the Schipbeek Canal, some five miles north of the Twente, and the 7th was preparing to assault Deventer. The capture of this town was an essential preliminary to General Simonds’ attack across the Ijssel in conjunction with General Foulkes’ operations at Arnhem.

Deventer, like Zutphen, lay on the right bank of the Ijssel with its approaches well protected by a maze of waterways. Again it was necessary to attack from the east. After “a very hard struggle”103 the 7th Brigade crossed the Zijkanaal, running north-east from the town’s outskirts, on the evening of 9 April. The Canadian Scottish led the way, capturing the nearby village of Schalkhaar without difficulty. When three German tanks appeared on the morning of the 10th one was quickly destroyed and the others put to flight by B Squadron of the 27th Armoured Regiment. At midday Brigadier Gibson’s main attack began, with the Canadian Scottish and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles right and left, respectively, and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, temporarily under command, maintaining pressure against the town’s south-eastern approaches. The enemy was forced back

* As an illustration of the command arrangements in the German forces during this period, it may be noted that the 88th Corps passed from the control of the Twenty-Fifth Army to that of Army Group Student on 3 April and, three days later, returned to Twenty-Fifth Army. The 361st was a Volksgrenadier division.

to his last major defensive line-an anti-tank ditch surrounding the town—but this did not long delay our troops. Resistance crumbled as many Germans were captured and others attempted to escape across the Ijssel, a manoeuvre rendered hazardous by the cooperating artillery of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division.104 By the evening of the 10th the brigade had occupied the main part of Deventer and, during the night, The Regina Rifle Regiment passed through the Winnipegs, clearing the south-eastern suburbs. Twenty-four hours after the main attack began Deventer was entirely in our hands, much of the credit for the speedy clearing of the town being due to “the extremely-well-organized Dutch Underground”. The 7th Brigade’s total infantry casualties (including those of the Queen’s Own) were 126; the brigade reported capturing about 500 prisoners.105

Operation CANNONSHOT: Crossing the Ijssel

At the end of the first week of April General Crerar, in accordance with Montgomery’s directive, still gave top priority to the task of opening a route from Arnhem to Zutphen. The reduction of Deventer and elimination of German resistance on the eastern bank of the Ijssel prepared the way for the decisive stage of these operations. Thus by 11 April the 2nd Corps was ready to carry out the initial phase of the Army Commander’s instructions for Operation CANNONSHOT—“the crossing of the Ijssel from the East, and the capture of Apeldoorn and high ground between that place and Arnhem”.106 As will be seen in the next chapter, the 1st Canadian Corps was already in position to attack Arnhem, with both Corps planning converging operations, north of that city, between the Ijssel and the Neder Rijn. The formation selected to make the assault across the Ijssel was Major-General H. W. Foster’s 1st Canadian Infantry Division, only recently arrived from Italy (above, page 529). Temporarily under General Simonds, it immediately began preparations for its first operation in North-West Europe.

CANNONSHOT was launched by the 2nd Infantry Brigade on the afternoon of the 11th, about midway between Zutphen and Deventer. The assault was delivered by Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada under cover of extensive artillery support, including smoke-screens on the flanks, concentrations of high explosive on known defensive positions and counterbattery and counter-mortar bombardments.107 At 4:30 p.m. the two battalions began crossing the river in “Buffaloes” of the 79th Armoured Division; not having used these vehicles in Italy, they had trained carefully with them before the operation. Surprise was achieved and “the action went speedily and according to plan”.108 On the left the Seaforth reported no opposition and, 65 minutes after the assault began, all their companies had consolidated on objectives; on the right, the Patricias encountered stiffer resistance, but after knocking out a French tank used by the Germans they too secured their ground.109 By six o’clock the first phase of CANNONSHOT had been successfully completed. Meanwhile, five companies of engineers had started bridging and rafting operations on the eastern bank of the Ijssel.* The

* The engineers under the Commanding Royal Engineer 1st Canadian Infantry Division had been increased for CANNONSHOT by the addition of the 32nd Field Company RCE He also had under his command the 277th Company of the (British) Pioneer Corps.

enemy’s artillery quickly registered this vital target and shellfire inflicted 17 casualties on the sappers. Nevertheless, by two o’clock on the following morning they had two rafts and a bridge ready to take wheeled and tracked vehicles across the river.110

On 12 April the 1st Brigade passed through the 2nd to expand the bridgehead westward towards Apeldoorn. In the course of the fighting the 48th Highlanders of Canada lost their Commanding Officer, Lt.-Col. D. A. Mackenzie, who was killed by a shell. The German artillery was accurate and troublesome, and the 2nd Brigade noted that houses in this theatre, unlike those in Italy, “provided no shelter from shelling due to the fact that houses were made of brick and not stone or cement”. The 3rd Brigade now crossed the Ijssel and the attack progressed rapidly on a wider frontage. By six o’clock on the morning of the 13th—at which time the division reverted to 1st Canadian Corps command—patrols had penetrated nearly halfway to Apeldoorn. General Foster’s troops were then preparing for the final thrust into the town.111 The concluding stages of CANNONSHOT, an integral part of the 1st Corps’ operations, will be described in the next chapter.

On to the North Sea

While operations were in progress on General Simonds’ left flank to open a maintenance route across the Ijssel, rapid advances were being made on the remainder of his front. We have seen that in the centre and on the right the 2nd and 4th Divisions had forced the Twente Canal at the beginning of April. The latter then veered north-east through Almelo, recrossing the Dutch-German frontier on 5 April, while the 2nd and 3rd Divisions continued their drive to clear the north-eastern Netherlands. In this task they were assisted by the 1st Polish Armoured Division, which rejoined the 2nd Corps on 8 April,112 and later by the 5th Canadian Armoured Division. Before describing the armoured operations on the eastern flank, we may conveniently consider the striking developments in the centre, where the 2nd Division advanced more than 80 miles in a direct line, from the Twente to the North Sea, in less than a fortnight.

When the 2nd Division lunged forward from the Twente available intelligence indicated that there could not be more than three German divisions in the northern and eastern Netherlands. Headquarters 21st Army Group did not favour trapping these formations in the western portion of the country since this would side-track Allied forces needed elsewhere. Rather, the intention was to press the enemy north and east of his Ijssel defences, forcing him to escape from the northern end of the “bag”,113 On 6 April the 6th Infantry Brigade reached the Schipbeek Canal about eight miles east of Deventer. The enemy had blown the only bridge in the area, but The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada found that marching troops could still cross on the damaged structure and against light opposition they soon established a bridgehead on the northern bank. The following day the 2nd Division drove on in the direction of Holten. The divisional staff noted that the supporting RAF were “howling for targets” but that “with this fast moving advance, enemy headquarters, gun positions and installations are almost impossible to pinpoint”.114

Meanwhile, preparations had been concluded for using airborne troops to assist the advance to the North Sea. At the end of March Brigadier J. M. Calvert, who commanded the Special Air Service troops, had discussed plans for their employment with officers at General Crerar’s headquarters. These troops were organized and trained to operate in small parties of about one officer and 10 to 15 men; they could be dropped in advance of our ground formations and, though only lightly armed, could cause confusion in German rear areas, help the Dutch Resistance and in other ways assist the progress of our divisions. Early in April it was agreed that two operations would be mounted: AMHERST, in the north-eastern Netherlands (with the cooperation, in a ground role, of the 1st Belgian Parachute Battalion) and KEYSTONE*115 west of the Ijssel.116 The airborne force selected for AMHERST comprised French units, the 2nd and 3rd Régiments de Chasseurs Parachutistes, operating under British command, and amounting to about 700 men equipped with wireless sets and armoured “Jeeps”. Their general task was the preservation of canal and river bridges on the 2nd Corps’ axes of advance; their first-priority special task was the preservation of two airfields at Steenwijk. They were also expected to harass the Germans and provide guides and information for forward elements of First Canadian Army.117

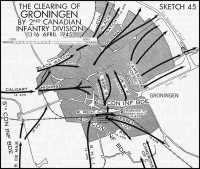

The drop took place on the night of 7-8 April. Although the weather was barely acceptable, aircraft of No. 38 Group RAF carried the SAS troops from England, dropping them with varying degrees of accuracy in the triangle formed by the towns of Groningen, Coevorden and Zwolle. There was no German antiaircraft fire, but due to certain deficiencies in training, it proved impossible to drop the units’ jeeps.118 Some were afterwards brought in overland and delivered to their owners. Contact was soon established at various points with the rapidly advancing divisions of the 2nd Corps. Early on the morning of 9 April the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) met the French near Meppel, while at Coevorden a Polish motorized battalion joined hands with the Belgian component of the SAS119 During succeeding days isolated detachments of parachutists fought almost continuously, sustaining 91 casualties, but capturing many prisoners, destroying communications and generally dislocating the enemy’s withdrawal. At Spier, halfway between Meppel and Assen, on the morning of the 11th, the CO of the 3rd RCP, having boldly captured the village with a small party, was rescued from imminent annihilation by far superior German forces by the timely arrival, in the best manner of the films, of vehicles of the 8th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment.120