Chapter 22: The German Surrender

(See Map 14 and Sketches 47, 48 and 49)

In the final days of April 1945 the military operations in Europe were approaching an inevitable end and the Allied leaders were concerned with international problems of the future.

There was growing difficulty between the Western powers and Russia over the future of Poland, and little unanimity between Britain and the United States on the political aspects of the campaign in Germany. Mr. Churchill was still anxious to carry the Allied advance as far, to the east as possible, thereby limiting the post-war influence of a suspicious and possibly hostile Russia. On the other hand President Truman, following the policies of his predecessor, was reluctant to take any action which might prejudice future relations with the Soviet Union.1 In the field, the Germans continued to fight obstinately, but the power of the Wehrmacht had been broken. Beleaguered in Berlin, Hitler was nearing the end of his extraordinary and malign career.

By 23 April converging Allied operations from east and west had compressed German-controlled Europe into the shape of a gigantic hour-glass. This was symbolic, for the sands were fast running out for the enemy. On the southern portion of General Eisenhower’s front the First French Army had cleared Stuttgart; farther north the Seventh United States Army had captured Nurnberg, the shrine of Nazism, and reached the Danube. In the centre, the First US Army had eliminated resistance in the Harz Mountains and occupied Leipzig, while the Third was rapidly approaching the Austrian border. The 12th Army Group held the general line of the Elbe River and was preparing to drive deep into the Danube basin and seize Salzburg. On 25 April the 69th United States Division was to meet the 58th Russian Guards Division near Torgau, on the upper Elbe. In the northern sector, the 21st Army Group had also reached the Elbe and liberated most of the north-eastern and part of the western Netherlands.

The Supreme Commander halted the main Allied forces on the lines of the Elbe and Mulde Rivers and the Erzgebirge. He later explained that logistical factors, and “the aim of concentrating forces now on the north and south flanks”, were largely responsible for this decision. The rapidity and scale of the advance “had strained our supply organization to an unprecedented degree”. A situation had developed which bore some resemblance to the problems of the pursuit during

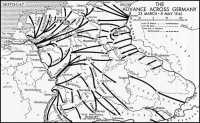

Sketch 47: The Advance Across Germany, 23 March–8 May 1945

the previous autumn, and only the expedient of supplying armoured columns by air had maintained the momentum of the advance.2

Canadian Tasks for the Final Phase

In his directive of 22 April3 (above, page 587) Field-Marshal Montgomery had stated that it was his intention “to capture Emden, Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck, and to clean up all German territory north of this general line”. General Dempsey’s Second Army was instructed to capture Bremen, clear the Cuxhaven peninsula, secure a bridgehead over the lower Elbe and seize Lübeck and thereby “seal off the Schleswig peninsula as quickly as possible”. A secure flank would be formed, north of the Elbe, on the general line Wismar–Schwerin–Darchau. This flank would be held by the 18th US Airborne Corps, operating under Dempsey; the 6th British Airborne Division was to be added to this corps. In a later phase, the Second British Army would occupy Hamburg and Kiel and clear all German territory north to the frontier with Denmark.

Apart from the instructions relating to the suspension of offensive operations in Western Holland, quoted in the previous chapter, the directive prescribed the tasks of First Canadian Army as follows:

12. The right wing of Canadian Army will operate strongly against Oldenburg, and south of it, in close touch with the left wing of Second Army which is advancing on Bremen.

13. As soon as the portion of Bremen on the south bank of the Weser has been captured by Second Army, the right wing of Canadian Army will operate northwards to capture Emden and Wilhelmshaven and clear all enemy from the peninsula between the rivers Weser and Ems.

14. Canadian Army will study the problem of capturing those islands at the eastern end of the Frisian group from which the enemy could interfere with the free use of the Weser estuary e.g. Wangerooge, and possibly also Spiekeroog.

...

16. Canadian Army will be prepared to release 49 Div to Second Army as soon as the operations referred to in 13 have been completed.

Responsibility for reduction of the Frisian Islands was delegated on 22 April to the GOC 2nd Canadian Corps, General Simonds, who, as previously mentioned (above, page 563) on the same day again became Acting Army Commander, though without relinquishing command of his corps.* He was to plan and execute the operation in conjunction with Captain A. F. Pugsley, Commander Naval Force T. As originally assigned, the task included both the East and West Frisian Islands; Wangerooge, at the mouth of the Weser, was to receive first priority, followed by Borkum, Norderney and Juist.4 However, on the 24th, Simonds obtained confirmation that the Army was concerned only with the islands at the eastern end of the Frisian group-in particular, Wangerooge, though Spiekeroog might also be a requirement. He reported that Field-Marshal Montgomery favoured reducing the islands by heavy bombing.5 Nevertheless, on the 27th, Montgomery’s headquarters issued another instruction ordering First Canadian Army to capture first Wangerooge and then Alte Mellum, a small sandy island in the mouth of the Weser. Although plans were drafted for these operations they were never required.6

* General Crerar returned to his headquarters on 29 April.

Simonds and his staff were too heavily engaged with other commitments to be able to concentrate on the Frisians, and the termination of hostilities on 5 May disposed of the problem.

In telling the story of the final Canadian operations in the campaign it is best to begin by describing the action on the front of the 2nd Corps, then continuing with a brief account of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion’s advance to the Baltic (as part of the 6th British Airborne Division, under the Second Army) and concluding with the continuation of efforts to bring relief to the Dutch on the front of the 1st Corps.

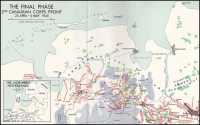

During this period the 2nd Canadian Corps’ commitments extended from the north-eastern Netherlands to the left bank of the Weser, below Bremen. Across this wide front the Corps Commander employed four Canadian divisions (the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th), the 1st Polish Armoured Division and, from 28 April to 6 May, the 3rd British Infantry Division. Supporting formations under his control included the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade and the 2nd Canadian and 4th British Army Groups, Royal Artillery. The pattern of the final operations had been clarified on 20 April, when the Corps Commander held a conference with Generals Keefler and Hoffmeister and assigned divisional tasks. On the right, the 2nd Division was to protect the western flank of the 30th Corps and advance on Vegesack, on the Weser. The 4th Division would continue north and then turn east against Oldenburg; but if that city proved to be too strongly held for an armoured division to tackle, General Vokes would “capture and seal off” its northern exits and close up to the Weser. The 5th Division, then still in the western Netherlands, would relieve the 3rd Division, enabling it, in turn, to relieve the Poles. They would thus be free to seize Papenburg and test the crossings over the Leda at Leer; but if opposition appeared too heavy, they would strike north-east to Varel, leaving the amphibious assault to Keefler’s infantry division. Following the capture of Leer, the 3rd Division would advance to Emden by way of Aurich.7

The Fight for Delfzijl

The operations of the 2nd Corps may conveniently be described from left to right, beginning with the 5th Division in the north-eastern Netherlands.

On 21 April, as already mentioned, the division began moving from western Holland to assume its new responsibilities; it passed under the 2nd Canadian Corps on the same date.8 Apart from relieving the 3rd Division, General Hoffmeister was given operational control over the provinces of Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe and the northern portion of Overijssel. (At a later stage these areas would pass to Headquarters Netherlands District and Lines of Communication.) His tasks were to clear the remaining Germans out of the area west of the junction of the Dutch-German frontier and the Ems estuary, to dominate the waters between the northern coast and the Frisian Islands, dealing with any raiding parties or patrols endeavouring to land, and to establish battle groups which could garrison the entire area effectively. In addition there was still a possibility that the divisional headquarters would be required to plan amphibious operations against Borkum and

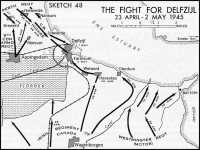

Sketch 48: The Fight for Delfzijl, 23 April–2 May 1945

Norderney. To assist Hoffmeister in his new role he was given eight Netherlands Independent Companies and anti-aircraft gunners for employment in ground roles and on occupation duties.9

The 5th Division virtually completed its relief of the 3rd Division on 24 April.10 Initially, the 5th Armoured Brigade held the area north and east of Groningen, exclusive of a German pocket centred on Delfzijl, and the 11th Infantry Brigade occupied the greater part of Friesland and north-western Overijssel, from the North Sea to Zwolle. However, Hoffmeister soon concluded that the reduction of the Delfzijl pocket was primarily a task for infantry. Therefore, on the morning of the 25th, Brigadier Johnston took over the division’s right sector from Brigadier Cumberland and the 11th Brigade prepared to capture the port. Responsibility for the left sector was transferred to the 5th Brigade.11

Delfzijl, with a pre-war population of 10,000, is one of the largest of the secondary ports of the Netherlands. It is located on the left bank of the Ems estuary, some 20 miles from the river’s mouth. Topography hampered operations in this area. The ground was flat with very little cover and “a complicated network of ditches and canals made cross-country movement impossible. The weather was wet and the whole area subject to flooding, which meant [that] all vehicles were confined to roads.”12 The German garrison was estimated at about 1500 fighting

troops, consisting of a battalion of marines*13 and various battle-groups, together with an unknown number employed on maintenance. The Germans had batteries and concrete emplacements in and around Delfzijl and “an outer perimeter of wire and a continuous trench system” surrounded the port. Heavy naval guns near Emden and on the island of Borkum could also give defensive fire.14

The Corps Commander coordinated the 3rd Division’s attack towards Emden with the 5th Division’s assault at Delfzijl.15 At the beginning of the latter operation Brigadier Johnston had under command, in addition to his own battalions, The Westminster Regiment (Motor), the 9th Armoured Regiment (The British Columbia Dragoons), a squadron (later two) of the New Brunswick Hussars, the 11th Independent Machine Gun Company (The Princess Louise Fusiliers), the 88th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery RCA and the 16th and 82nd Anti-Tank Batteries RCA The divisional field artillery was also actively engaged and later stages of the operation were supported by the 31st (British) Anti-Aircraft Brigade and the 3rd Battery of the 1st Heavy Regiment RA, mainly in counter-battery roles.16

Brigadier Johnston’s first step, beginning on 25 April, was to reduce the perimeter of the defence with steady pressure exerted by the Westminsters and The Irish Regiment of Canada from the south, the Dragoons from the west and The Perth Regiment from the north. This was not accomplished without difficulty. The Westminsters were heavily shelled and movement during daylight was exceedingly difficult; however, by the end of the month, they had cleared all of their area except a spit protruding deep into the Dollart, seven miles south-east of Delfzijl, where the Germans had a troublesome battery. Not until the port fell (1 May) did the enemy evacuate this position by sea. Meanwhile the Irish made steady progress from Wagenborgen to Oterdum and Heveskes (little more than a mile from the south-eastern outskirts of Delfzijl), which they had cleared by the 30th. “The going was slow as they had to deal with mines and road demolitions before they could get any supporting arms forward.” They also endured much shelling, some coming across the estuary from the vicinity of Emden.17 The British Columbia Dragoons held the northern portion of Appingedam. Partly dismounted, they were under constant fire, with forward movement impeded by demolitions and waterways; they recorded that “spasmodic shelling made life miserable for the forward squadrons as the slit trenches have become very muddy”.18 However, our own artillery, in particular the 8th Field Regiment (Self-Propelled) RCA, replied vigorously and on the 29th the Dragoons were able to advance, in conjunction with the Perths on their left, and occupy nearby Marsum. On the northern flank, the Perths encountered the heaviest opposition of the whole operation. Entering Krewerd on the night of 23-24 April, the battalion’s main objective was a line through Nansum and Holwierde, about four miles north-west of Delfzijl. This was not secured until the 29th, after hard fighting in which the infantry were assisted by Spitfires, A Squadron of the New Brunswick Hussars and our artillery firing airbursts. The Perths suffered 78 casualties during the period 24-29 April.19

* These were not marines as known in the British and American services; they were simply ad hoc organizations of ships’ crews and personnel from bases and depots. Nevertheless they frequently fought well.

The time had now come for the decisive assault on Delfzijl itself. This task was assigned to The Cape Breton Highlanders, who had relieved the Perths on the evening of the 29th and then pushed forward to seize Uitwierde, mid-way between Marsum and the estuary. The main attack began at 10:00 p.m. on the 30th. Progress was delayed by wire and minefields covered by German positions dug in along the dykes. On the morning of 1 May the troops were temporarily pinned down by the enemy’s fire. An officer who was there described D Company’s difficulties in assaulting “four large enemy bunkers, each the size of a bungalow, and all constructed of 4-ft. thick reinforced concrete”:20

One of these bunkers—the command post for the guns along the dykes—could raise its periscope and view our axis of advance over the flat Dutch farmland quite easily. Luckily for D Coy, the gunners on top of the dyke could not depress their pieces sufficiently to fire directly at us coming along a road half-way up the landward side of the dyke. This was our company’s axis, since the open fields around the strongpoint were heavily mined.

Meanwhile B Company, supported by a troop of the Hussars’ tanks, captured the railway station on the northern outskirts of Delfzijl. Shortly thereafter opposition died down and German soldiers were seen “retreating over the dyke and pushing off in boats heading across the estuary towards Germany”.21 Our artillery rendered their passage extremely hazardous.

Delfzijl was completely cleared on the 1st, and on the following day the Irish extinguished the remaining embers of resistance in the pocket at Weiwerd and Farmsum, capturing 38 officers (including the garrison commander) and over 1300 other ranks. Fortunately, the lock gates and other installations at Delfzijl, although prepared for demolition, were preserved intact; also, the German commander and his staff cooperated in locating and dealing with numerous indiscriminately strewn minefields. Our own casualties were lighter than might have been anticipated. The Irish Regiment and The Cape Breton Highlanders had 67 and 68 respectively; the Westminsters, 23.22 With these losses, in its last major operation, the 5th Canadian Armoured Division had successfully carried out a difficult task, capturing 109 German officers and 4034 other ranks.23

Across the Ems and the Leda

While the 5th Division was dealing with the Delfzijl pocket, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division were crossing the Ems and the Leda, loosening the German hold on the eastern bank of the Ems estuary and penetrating deep into the Emden-Wilhelmshaven peninsula. We have seen that General Simonds originally intended that the Poles would reconnoitre the crossings over the Leda at Leer; if these were too strongly held, the actual assault would be performed by Keefler’s “Water Rats”, while the Poles went for Varel, at the eastern base of the Emden-Wilhelmshaven peninsula. The latter alternative ultimately proved necessary. The problem was in fact settled by developments to the eastward, where the 4th Armoured Division’s bridgehead north of the Küsten Canal was under heavy attack. Consequently, on the morning of the

22nd, the Polish Armoured Division was directed along a north-easterly axis to relieve the pressure here. The tasks of forcing the Ems and the Leda and capturing Leer fell to the 3rd Division.24

Leer is a small port for sea-going vessels at the junction of the Ems and the Leda. The town is an important communication centre, connected by good roads with Emden and Wilhelmshaven. Although the Polish advance east of the Ems had simplified the approach, an assault across the wide lower reaches of the Ems (where tidal action causes differences in width of up to 300 feet)25 promised to be difficult. The Leda, though narrower than the Ems, is itself some 200 yards wide at Leer and is also subject to tidal variations. These rivers surrounded the port on three sides and the fourth was protected by marshy ground. All bridges had been demolished.

Before the attack General Keefler’s Intelligence staff could provide little definite information on the Germans in Leer. It was thought, however, that they might have two battalions for the defence of the town and its immediate vicinity; reports also indicated that supporting arms were “not plentiful”. Afterwards we learned that the defending force had consisted of a unit of marine replacements and some Flak troops, all under a lieutenant colonel. He had placed three companies on the western outskirts of Leer, to guard against attack across the Ems, and four on the southern perimeter, the Leda side. These marines were quite untrained—“for many it was the first experience in land battle”—and their morale was low.26

DUCK was the appropriate code name given to the 3rd Division’s amphibious operation to take Leer and nearby Loga. The assault was to be carried out in three phases: first, the 9th Infantry Brigade would attack across the two rivers and establish a bridgehead; then the 7th Brigade would pass through to capture Loga and an adjacent wood (Julianen Park); finally, the 9th Brigade would enlarge the bridgehead northwards as a base for exploitation towards Veenhusen and Terborg, in the direction of Emden.27 In the initial phase, Brigadier Rockingham ordered The North Nova Scotia Highlanders to cross the Leda in stormboats, on the right of the brigade, secure the northern bank of the river and develop the main attack to capture Leer. In the centre, The Highland Light Infantry of Canada were to descend the Ems and land at a point named Leerort, where the Ems and the Leda meet. On the left, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry High landers would attack directly across the Ems and seize the town’s western edge. Rockingham reasoned that simultaneous attacks at three points would prevent the enemy from concentrating his defence. The timing of the assault required special consideration, not only because of tidal variations, but because HQ 2nd Corps had ordered that the planned bridgehead should be firm by nightfall, in order that engineers could start their operations under cover of darkness. Accordingly H Hour was set for three o’clock in the afternoon of 28 April.28

The 3rd Division’s resources were considerably augmented to meet the special demands of DUCK. Under command for the operation were the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment), two batteries of the 6th Anti-Tank Regiment RCA (from Corps Troops) and Headquarters 2nd Corps Troops RCE with the 20th and 31st Field Companies RCE The operation would also

be supported by “Crocodiles” of A Squadron of the 141st Regiment RAC, the 4th Army Group, RA, the 16th/1st Heavy Battery RA, the 11th Army Field Regiment RCA (in addition to the divisional artillery) and a British smoke company of the Pioneer Corps. A “Pepper Pot”, organized by the Commanding Officer of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG), would also assist the 9th Brigade’s assault.29

In the early afternoon of the 28th, Typhoons shot up targets in Leer and, 35 minutes before the stormboats were launched, the artillery opened a heavy bombardment. Brigadier Rockingham observed: “The shooting was for the greater part excellent, as burst after burst was seen along the dykes where the enemy was entrenched.”30 However, on the 9th Brigade’s right flank, the German positions were too close to our assembly area for the artillery to give support and a contrary wind made a normal smoke-screen impracticable. Nevertheless, the North Nova Scotias employed their 2-inch mortars, firing smoke, to screen the attack and they were helped by weapons of the Camerons and the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment. “D Company, carrying the assault boats, left the cover of the dykes, dashed to the river banks, boarded the boats and were soon on the other side.” The Germans were completely surprised; they were found cowering in their trenches and “three machine-guns were captured, fully loaded, before firing a round”.31 The remainder of the North Nova Scotias followed D Company and in a short time had penetrated deeply into the southern portion of Leer. Meanwhile, two miles south of the town, The Highland Light Infantry of Canada launched their boats on the Ems, moving downstream to the point at Leerort. Although delayed en route, they received such excellent support from the artillery that their landing was virtually unopposed. The HLI then pressed forward into the centre of Leer “against sniper and Panzerfaust fire”.32 On the left of the brigade The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders encountered the heaviest opposition. As their boats crossed the Ems, 400 yards wide at this point, they were engaged by machine-guns from both flanks. The leading companies reached the eastern bank at 3:08 p.m.; but sustained German fire sank two boats in a second wave and 15 men were believed drowned. (Brigadier Rockingham afterwards questioned “the suitability of the type of lifebelt” then used.) The battalion mopped up resistance along the adjacent dyke and proceeded methodically to clear the western part of Leer.33

There was fierce street fighting in the process. Germans infiltrated our positions and, at times, “fought with the greatest dash and bravery”.34 Great care was needed to avoid clashes between our own troops. Another difficulty arose in connection with the build-up: wind, tide and engine-trouble plagued the engineers’ efforts to maintain ferry service across the rivers. Finally DUCK was halted on the night of the 28th, to be resumed on the following morning. The operation then proceeded smoothly and by 6:50 p.m. on the 29th Brigadier Rockingham was able to report that his brigade had all its objectives-that is, as far as the railway running through the eastern section of Leer. The fighting on the 28th and 29th cost his three battalions 70 casualties in all.35 This relatively light loss was certainly

due to the soundness of the tactical plan as well as to the supporting arms’ efficiency and the determination of the assaulting troops.

The 7th Infantry Brigade completed the capture of Leer and its vicinity. Late on the 29th The Regina Rifle Regiment moved eastward across the railway without serious opposition. Next morning it swung south to clear the right bank of the Leda, overcoming unexpected resistance in a German barracks. Meanwhile The Royal Winnipeg Rifles had cleared Julianen Park; the Canadian Scottish then took Loga with little difficulty, delayed only by the rubble in the streets.36

Late on 1 May the 3rd Division’s headquarters issued instructions for the final phase of the campaign that had begun on the beaches of Normandy. While the 7th Brigade held the Leer bridgehead, the 8th was to drive on towards Aurich, seizing crossings over the Ems-Jade Canal. The 7th would then take over and capture Aurich, while the 9th Brigade, on the left, probed towards Emden. The 8th and 9th Brigades proceeded to advance steadily along their designated routes in the face of scattered resistance and extensive demolitions; but hostilities ceased before the objectives were reached. The 8th Brigade was on the outskirts of Aurich, and Brigadier Roberts was negotiating with the Germans for the surrender of the place, when operations were suspended on 4 May.37

The Advance into the Emden-Wilhelmshaven Peninsula

In the centre of the 2nd Corps’ active front, General Simonds’ two armoured divisions drove well into the base of the Emden-Wilhelmshaven peninsula before the campaign ended. In this area the German order of battle underwent kaleidoscopic changes during the last days. Out of a mass of confusing and contradictory identification—including verification of a squadron of cavalry under command of a parachute regiment—our Intelligence could draw only tentative conclusions. (Even today, due to the absence of German records for the final phase, we can do little better.) However, at the end of April, it appeared that the front between the Weser and the Ems was divided into five “divisional” commands. In the west, we believed that the 2nd Parachute Corps controlled three: the 7th and 8th Parachute Divisions and Battle Group “Gericke”—a parachute formation including naval troops. The eastern flank was thought to be under the 86th Corps, with the 471st and 490th Infantry Divisions (“divisional staffs controlling a miscellany of battle groups”) under command.38

Although the enemy entered the last round battered and disorganized, he still had one important factor in his favour—the difficult terrain north of the Küsten Canal. We have already seen (above pages 559-61) that both the 4th and the 1st Polish Armoured Divisions had fierce struggles for crossings over this obstacle. Fighting forward north of the canal, the armour found seemingly endless stretches of wet ground, interlaced with countless ditches and streams. The maps were full of treacherous bogs and ponds; movement—particularly armoured movement—was restricted to a few routes, and these were vulnerable to counter-attack. In this country even an inexperienced unit, if determined, could hold up an entire division. Yet, with infantry divisions fully engaged on either flank, Generals Vokes and

Maczek were compelled to commit their tanks, half-tracks and other heavy vehicles over this unsuitable battlefield.

On 22 April, as previously mentioned, the Corps Commander directed the 1st Polish Armoured Division towards Varel in order to relieve the pressure on Vokes’ western flank. Soon, however, bad roads slowed the Poles’ advance. By the 25th their 3rd Infantry Brigade Group had reached Potshausen, on the upper Leda; assisted by aerial and artillery bombardments, it obtained a foothold beyond the river here. But construction of a bridge was delayed by heavy German fire, and reconnaissance revealed that the road leading north to Stickhausen was obstructed by six craters, each between 40 and 60 feet wide, within a distance of 500 metres.39 Not until 1 May did the Poles manage to cross the Jümme River, a tributary of the Leda, and occupy Stickhausen. Meanwhile, on 30 April, the 10th Polish Armoured Brigade struck out from the Canadian bridgehead at Leer in the direction of Hesel, about five miles distant, which they secured on the following day.40

The continuing Polish advance, although delayed by the roads, gave some help to the 4th Armoured Division’s operations. The Poles met sporadic resistance to the end of the campaign. An attempt to seize a bridge near Moorburg, on the 2nd, cost them five tanks; but contact with General Vokes’ troops was finally established at Westerstede on the 3rd41 In the final stages, the Polish Division was directed towards Neuenburg, Jever and Wilhelmshaven. On the evening of the 4th, Maczek’s infantry and armoured reconnaissance troops reached the hamlet of Astederfeld, only two miles south of Neuenburg. In action to the end, the Polish artillery pounded German positions until one minute before the “cease fire” on the morning of 5 May.42

Meanwhile the 4th Canadian Armoured Division was striving to expand its bridgehead beyond the Küsten Canal. On 20 April General Simonds had ordered it to advance on Oldenburg (above, page 591). On General Vokes’ right flank, the boundary between the 2nd and 4th Divisions ran north-east just to the north of Sage and Huntlosen, along the River Hunte and the eastern section of Oldenburg to the Weser.43

The advance north of the Küsten Canal was a fitting sequel to the costly struggle for a bridgehead. Although the defenders consisted mainly of marines and remnants from the 7th Parachute Division, hastily organized and flung into battle, they fought hard. On 21 April the 10th Infantry Brigade forced these people back over the River Aue near Osterscheps, giving our bridgehead a depth of more than two miles. As The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s) moved forward they observed the grim effect of our supporting aircraft and artillery: “The main road leading north from the canal was literally strewn on either side with German dead. The enemy had evidently not found time to bury them all, and there were disfigured bodies in or near every slit-trench. It proved once more how very effective close air and ground co-operation can be.”44 The 28th Armoured Regiment (The British Columbia Regiment) also supported the infantry; at one point their 30-ton Shermans successfully crossed a light Bailey bridge, designed to carry 12 tons, to assist The Algonquin Regiment.45 Early on the 24th the

Algonquins captured an important road junction near Edewecht, and the village itself was in our hands on the following day. Meanwhile, The Lincoln and Welland Regiment took high ground on the south-eastern outskirts after persistent attacks. The severity of the fighting was reflected in our losses. During the period 17-25 April, the 10th Brigade’s three battalions had a total of 402 casualties; the heaviest burden fell on the Argylls, who lost 146 men, including 41 killed.46 On the 22nd this unit recorded that the fighting strength of its companies had been “reduced to about 55-60 each in A, B and C, with only 47 remaining in D”. It received 90 reinforcements the following day-evidence that the reinforcement situation was well in hand.47 The steady expansion of the bridgehead was not accomplished without severe strain on maintenance. A senior staff officer of the 4th Division described the difficulties:48

Not only had the roads leading up to the Canal deteriorated seriously, but there was only a single road north from Edewechterdamm across the Küsten swamps to Bad Zwischenahn, and that displayed an alarming tendency to ‘disappear’ under us altogether. Faced with this situation, the GOC [General Vokes] decided to concentrate all available RCE resources and all available vehicles to maintain these roads. They were, in fact, kept open, but only by dint of a tremendous effort on the part of the divisional engineers.

With the Argylls and the Lincoln and Welland under command, Brigadier Moncel’s 4th Armoured Brigade took over on the morning of the 25th the task of expanding the bridgehead towards Bad Zwischenahn. The armour’s right (eastern) flank was protected by the 10th Brigade, reinforced by the 27th Royal Marine Battalion, while the 29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) operated south of Oldenburg. On Moncel’s left the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) drove northwest towards Godensholt.49 Commenting on the tactics employed along the main axis, the brigade commander observed that “the condition of the roads in the bridgehead was such that no more than two squadrons of armour could be deployed at any one time, and usually only one troop of each could be used for direct fire”; he therefore decided “to choose company objectives some 200 yards apart, to tee-up company attacks supported by a troop of tanks, and to drive straight ahead”.50 These tactics were supplemented by particularly efficient cooperation between ground and air forces. This was partly achieved by the use of a “contact tank”,*51 equipped with special wireless, in direct communication with close-support aircraft, and commanded by an officer of the Royal Air Force. Employed with the leading company of The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor), it brought rocket-firing aircraft into action within 300 yards of our forward troops.52

As the northward thrust continued the cages filled with German prisoners and deserters (during April the 4th Division captured over 3600 prisoners); but the enemy continued to resist strongly along the approaches to Bad Zwischenahn. Road-blocks, mines and craters, covered by the fire of self-propelled guns, mortars, machine-guns and other weapons, delayed the 4th Armoured Brigade’s advance.53 On the 26th the Lake Superior Regiment, supported by tanks of the 22nd Armoured

* A similar, but less satisfactory, procedure had been employed during earlier phases of the campaign-for example, in support of the 7th Infantry Brigade on 21 February.

Regiment (The Canadian Grenadier Guards), reached a bridge at Querenstede, some two miles south-west of Bad Zwischenahn, only to have it blown in their faces. On their right, The Lincoln and Welland Regiment also had difficulty; apart from dealing with continual obstacles, they had trouble maintaining communications between tanks and infantry platoons because of “thick hedges, resembling those found in the bocage country of Normandy”. Nevertheless, on the 28th they captured Ekern and next morning seized high ground on the southern edge of Bad Zwischenahn under machine-gun and 88-mm. fire from the town.54

Meanwhile, steps had been taken on 27 April to strengthen General Vokes’ left flank. For this purpose he took under command the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade* (less the 10th and 27th Armoured Regiments, then supporting the 2nd and 3rd Divisions, respectively) with the 1st Armoured Car Regiment (The Royal Canadian Dragoons), and the 1st and Belgian Special Air Service Regiments. This force was instructed to capture Godensholt, Ocholt, Apen and Barssel, make contact with the Poles at Bollingen, and patrol north and east to Torsholt and Rostrup.55 Brigadier Robinson accordingly dispatched “Frank Force”, evidently named for Lt.-Col. F. E. White, commanding the 6th Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars), and composed of elements of that regiment, the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) and the Belgian SAS Regiment, in the direction of Godensholt. With the help of armoured bulldozers and Bailey bridging equipment “Frank Force” had reached the village by 30 April. The Royal Canadian Dragoons then pushed on to Westerstede where, as we have seen, they met the Poles on 3 May. When the fighting ended the 2nd Armoured Brigade was advancing on a north-easterly axis, the armoured cars reaching Grabstede, 12 miles north of Bad Zwischenahn, on the 4th.56

While these developments were taking place on his left flank, General Vokes was dealing with Bad Zwischenahn. On 30 April The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, supported by a squadron of the Canadian Grenadier Guards, outflanked the town from the west and closed its northern exits by reaching the shore of the adjacent lake, the Zwischenahner Meer; simultaneously, The Lincoln and Welland Regiment fought its way into the eastern outskirts.57 Further German resistance appeared hopeless and the divisional commander sent an ultimatum to the burgomaster offering a choice of “unconditional surrender” or “annihilation”. The German military commander does not seem to have made a formal surrender, but he did evacuate Bad Zwischenahn, apparently reserving the right to shell the town if our troops moved in. These terms were, in effect if not in form, accepted. General Vokes placed the town “out of bounds” to all troops, save for “through” traffic.58

On the night of 30 April-1 May the enemy withdrew his heavy equipment on the 4th Armoured Brigade front. The following day, accordingly, resistance was light in this sector west of the Zwischenahner Meer, though it “remained tough” on the 10th Brigade’s to the south-east. Meanwhile, the 2nd Division’s easier progress on the right brought a change of plans; by 1 May that formation was preparing to take Oldenburg and the 4th Division was therefore redirected upon Varel.

* Commanded since the previous December by Brigadier G. W. Robinson.

General Vokes planned to send the 10th Infantry Brigade through Bockhorn and Neuenburg, while the 4th Armoured Brigade cut the main highway running north from Oldenburg to Varel and Wilhelmshaven.59

With the Argylls and the Lincoln and Welland back under command, the 10th Brigade made steady progress against sporadic resistance. On the 4th, divisional headquarters recorded: “At a few points small groups of infantry knotted around a mortar or a self-propelled gun have fought well. More often, however, they have been very ready to surrender.”60 By evening that day the Argylls, supported by British Columbia Regiment tanks, were near Mollberg, seven miles north-east of Bad Zwischenahn. On the armoured brigade’s front The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor), along with the Canadian Grenadier Guards, captured Rastede and reached the outskirts of Bekhausen, ten miles north of Oldenburg.61

The Advance to Oldenburg

On General Crerar’s far eastern flank the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division and, beginning on 28 April, the 3rd British Infantry Division had somewhat easier tasks than their neighbours. It will be recalled that General Matthews’ division had been brought from the Groningen sector to operate between the 43rd (Wessex) Division, directed on Delmenhorst, and the 4th Armoured Division. The object of this regrouping was to assist the Second British Army’s attack on Bremen. Initially, therefore, the 2nd Division was ordered to clear the left bank of the Weser opposite Vegesack, some ten miles below Bremen.62

On 19 April the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade relieved the 214th Brigade of the Wessex Division near Ahlhorn, about 15 miles south of Oldenburg. The 4th Brigade’s patrols advanced along the railway leading towards Oldenburg without encountering serious resistance. On the 22nd the divisional axis swung eastward, aimed at Vegesack, and the 5th Brigade passed through the 4th to occupy the Huntlosen area. Its headquarters reported that “practically no opposition was met at all—a few stragglers and deserters, but no real contact with the enemy”.63 However, mines and felled trees imposed some delay. It was then the turn of the 6th Brigade, which had the task of capturing Kirchhatten, athwart the road connecting Wildeshausen with Oldenburg.

At Kirchhatten the enemy reacted vigorously but ineffectually. The place was defended by six companies of a “Battle Group Lier”, formed from a noncommissioned officers’ school near Hanover, under the nominal control of the 490th Division, a weak formation composed of miscellaneous elements including marines.64 Brigadier Allard’s attack was supported by C Squadron of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse), two companies of the divisional support battalion, The Toronto Scottish Regiment (MG), and field, medium and anti-tank artillery. In the village and neighbouring woods The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada encountered stiff resistance. The enemy was well dug in, and counter-attacked in strength on the afternoon of the 23rd. He was, however, beaten back with the help of tanks and artillery. Another German effort next day failed to dislodge our troops and the 6th Brigade strengthened its hold.

In spite of this show of fight, the 2nd Division’s Intelligence staff concluded that the enemy’s attention was focussed on the defence of Wilhelmshaven, “leaving poorer troops for less important task our front”.65

Meanwhile the 4th Brigade drove forward with Kirchkimmen and Falkenburg, on the main road between Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, as its objectives. On the left, The Royal Regiment of Canada was soon “heavily engaged with numerous enemy infantry”;66 while, on the right, The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry had an easier time taking Nuttel. The Essex Scottish Regiment then intervened to relieve the pressure on the Royals. On the 25th the brigade resumed its advance under heavy fire; but “with quick and efficient artillery support and the ready co-operation of the tanks [of the Fort Garry Horse] little delay was imposed”. Typhoons also lent assistance, attacking positions shown on captured maps or located by prisoners. The latter were, in the Royals’ words, “a motley collection of engineers, marines, paratroopers, etc.” There were continual signs of enemy deterioration; one prisoner proved to be a technical officer of the Luftwaffe with two days’ experience in the infantry. By the late afternoon of the 25th both the Royals and the

RHLI had secured objectives astride the Oldenburg-Delmenhorst highway. That evening, thanks to the YMCA, the RHLI saw a movie in Falkenburg.67 Meanwhile, 200 miles to the south-east, Russian and American troops had joined hands. On General Matthews’ immediate right, the 30th Corps was operating against Bremen; by the afternoon of 25 April British troops had penetrated to the heart of the battered city.68 Resistance was collapsing everywhere. Yet, as Delfzijl, Leer and the Küsten Canal bridgehead had shown, the enemy was still capable of lethal local opposition.

The 2nd Division now pivoted still farther north-east, cutting the railway between Oldenburg and Delmenhorst and clearing the low-lying area west of the Weser. Leaving the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment RCA to hold the division’s left flank, the 5th Brigade began this operation on the morning of 26 April. The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada advanced north-west from Delmenhorst, passing through units of the Highland Division, in the direction of Hude. Before long the old familiar pattern of shelling, rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire slowed its progress. A Squadron of the Fort Garry Horse lost one tank aiding the infantry, while a supporting Toronto Scottish platoon had 11 casualties from shellfire. Particularly stubborn opposition came from Germans sheltering behind the railway embankment, as they had at the South Beveland isthmus in the previous autumn, and although these men were less skilful than those met on the Scheldt, they could not be lightly dismissed. Nevertheless, by the end of the day our troops were firmly established some four miles north-west of Delmenhorst.69 Meanwhile Le Régiment de Maisonneuve captured its objectives under heavy shellfire and, in the late afternoon, The Calgary Highlanders moved north along the road between Bockhorn and Gruppenbuhren, reaching positions just short of the railway. These operations continued during the next three days, with the 5th Brigade gradually clearing west to Hude, less than 10 miles from Oldenburg. Even at this stage the enemy was not giving in easily; during

the period 26-29 April the brigade had 130 casualties, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, with 54, suffering most heavily.70

By 27 April the German forces on the 2nd Division front had been reduced to miscellaneous battle groups under the staffs of the 471st and 490th Infantry Divisions. On that day General Matthews ordered the 5th Brigade and the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), which had been operating on his right flank, to finish clearing the area south and west of the Weser while the rest of the division turned its attention to capturing that portion of Oldenburg lying south of the Küsten Canal and the Hunte River system. This was not, however, the immediate aim; “the intention was to secure limited objectives and to get into positions from which the momentum of the final phase could be maintained without interruption”.71

Added impetus was given to the 2nd Division’s operations against Oldenburg when the 3rd British Infantry Division (Major-General L. G. Whistler) came under the 2nd Canadian Corps on the 28th. Whistler was ordered to relieve the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade and continue clearing the area west of the Weser. The inter-divisional boundary ran north from Ganderkesee to Butzhausen and on to the left bank of the river.72 There was, however, little for the 3rd Division to do; its historian observes that “though the Gunners had some excellent shooting at odd bands of soldiers fleeing from the Canadians across the coastal plain, there was no further fighting”. After the cessation of hostilities the division returned to General Dempsey’s command.73

Oldenburg, a pleasant town with a population (1939) of 79,000, dates from the 12th century. Fortunately, our expectation that it would be “defended as a bastion to the full extent of the resources available to the enemy”74 was not fulfilled.

On 28 April General Matthews was instructed to advance towards Oldenburg with all three brigades.75 While the 5th continued to exploit north of Hude, the 4th and 6th approached Oldenburg from the east and south respectively. The weather was cloudy and cool with much rain. Our troops advanced steadily against light opposition. Propaganda leaflets, printed in Delmenhorst, were fired into Oldenburg urging the futility of further resistance. The end came as something of an anti-climax. On 3 May the 4th and 6th Brigades entered the city only to find that the defenders had fled. On the following day firm contact was established with the 4th Canadian Armoured Division; and in the last hours of the campaign the 2nd Division pushed north of Oldenburg, prepared to clear the Butjadinger “thumb”, between the mouths of the Jade and the Weser.76

The Parachute Battalion Marches to Wismar

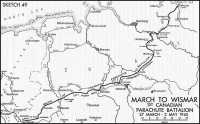

This account of the last phase of the fighting may appropriately conclude with the story of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion’s advance to the Baltic Sea.

It will be recalled (above, pages 535-7) that on 24 March the battalion had dropped east of the Rhine to play its part in Operation VARSITY. This was its last parachute operation. The concluding weeks of the war found it, still serving in

the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the 6th British Airborne Division.* in the van of the Second British Army’s rapid advance across Germany. It was now commanded by Lt.-Col. G. F. Eadie.

In the first stage of the advance the 6th Airborne Division was still under the 18th US Airborne Corps, but on 29 March it passed to the 8th British Corps. On the same day the 3rd Parachute Brigade cleared the town of Lembeck.77 As the drive continued in the direction of Coesfeld, a potent alliance was formed between airborne and armoured troops: the 4th (Armoured) Battalion of the Grenadier Guards came in support of the 6th Airborne Division, No. 1 Squadron being allocated to the 3rd Parachute Brigade. The Canadian parachutists now enjoyed the—for them—novel experience of riding into action on tanks.78 Crossing the Dortmund-Ems Canal by a partially demolished bridge on 1 April, they took Ladbergen in a stiff little fight and thereafter drove rapidly on, bypassing isolated groups of German soldiers. On 3 April they covered 40 miles and reached Minden, scene of a famous British victory of 1759, on the 4th.79

After receiving 100 reinforcements from England the battalion crossed the Weser and pushed north-eastwards accompanied by the Grenadiers. The Canadians were in a high state of training and fitness. Their brigade commander (Brigadier S. J. L. Hill) described an incident that occurred at Ricklingen on 8 April:80

Having marched 20 miles over very bad roads the day before, they marched a further 14... and were then called on to put in an assault on a small village. This they successfully did. Meanwhile, an SOS had been sent out for them to try and rescue a small reconnaissance detachment which was holding an important bridge just to the south [actually 10 miles west] of Hannover and in order to do this the leading company of the Battalion doubled pretty well non-stop for two miles with full equipment and stormed the bridge over an extremely open piece of ground under fire from three or four German SP guns [the Canadian diary mentioned only one] without turning a hair. They got the bridge intact, but the Reconnaissance Regiment had been unable to hold out.

It was during the fight that the guardsmen, not without surprise, overheard a Canadian sergeant giving his orders: “I guess we gotta get this bridge and if we hit anything, don’t you guys sit around. Let’s go.”81 They went, and the Germans retreated.

By the 14th the battalion was in Celle. Three days later it seized Riestedt, near Uelzen, with the support of tanks and artillery. The 6th Airborne Division was now rapidly approaching the Elbe; Dempsey’s spearheads reached and crossed it on the 29th. On that day the Canadians, who had been resting since the 22nd at Kolkhagen, south of Luneburg, resumed their advance. On the 30th they crossed the Elbe, some 40 miles upstream from Hamburg. On 30 April also the 18th United States Airborne Corps came under Second Army and simultaneously secured a second bridgehead at Bleckede; and on 1 May the 6th Airborne Division passed to the command of the American corps. The remaining task now was to reach the Baltic shore and block the advancing Russians off from the Danish peninsula.82

In contrast with the situation on the 2nd Canadian Corps front, where there was fighting—in some places bitter fighting—up to the last moment, the Second British Army in these final days met virtually no opposition. The 2nd of May was the

* The 6th Airborne Division was now commanded by Major-General E. L. Bols.

Sketch 49: March to Wismar, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, 27 March–2 May 1945

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion’s last day of active operations. It brought no action, but was not wanting in drama. It began with the establishment of liaison near the village of Bahlendorf with another famous British regiment, The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons). Mounting the battalion on its tanks, C Squadron of the Greys set off towards the north-east and the beckoning Baltic. There was nothing to stop the advance, and it was made at top speed, the Greys’ longest charge. (One parachutist is reported to have remarked, “I never realized that a Sherman could do sixty miles an hour.”) It had been “hoped that Wittenburg would be taken by the end of the day”, but it was in fact reached in the morning and the force pushed on to Lutzow. Here the tanks refuelled and the dash continued. The Canadian battalion’s diarist recorded, “All resistance had collapsed, because the Germans wanted us to go as far as possible. They reasoned that the more territory we occupied, the less the Russians could occupy. Thousands of German troops lined the roads and crowded the villages, some even cheering us on, though most were a despondent-looking mob.” The Greys described the thousands of Germans who surrendered at Gadebusch. “From now onwards for the rest of the day prisoners of war continued to stream one way while we streamed the other. In many cases the Germans were in their own mechanical transport and in one case a Mark III [tank] was observed in the prisoner-of-war column.”83

Wismar was the end of the road. At this picturesque medieval town, once a Hansa city, the Canadians and the Greys reached the shores of the Baltic and met the Russians. The place fell on the evening of the 2nd without resistance, though tanks did a very little firing at an aerodrome north of the town. That night a Soviet officer arrived “in a jeep, with his driver”. He had no idea that Allied forces were in Wismar until he came to the Canadian barrier. “He had come far in advance of his own columns, and was quite put out to find us sitting on what was the Russians’ ultimate objective.” The next day there was “considerable visiting” between Canadian and Russian officers, and the latter, the Canadians recorded, “proved to be the most persistent and thirsty drinkers we had ever met”. The “shooting war” was over for the 1st Parachute Battalion. It had had an excellent fighting record. During the advance from the Rhine to the Baltic, since the day of the VARSITY drop, 24 March, it had suffered 61 casualties, 15 men losing their lives. Its casualties for the whole campaign numbered 496, of which 125 were fatal.84

It was fitting that the first Canadian unit to fight in Normandy should also be the Canadian unit to penetrate deepest into Germany. Wismar, taken by Lt.-Col. Eadie’s men and the Royal Scots Greys, was in fact the most easterly point reached by any Commonwealth troops in this campaign, and the first point where any Commonwealth troops serving in it made contact with the Russian ally. It is satisfactory that a Canadian battalion was there.

Help for the Western Netherlands

We may now return back to consider the steps taken on the 1st Corps’ front to relieve Dutch distress at the end of hostilities. We have seen (above, pages 584-5)

that the crisis in the western Netherlands led to unofficial negotiations with the Reichskommissar, Seyss-Inquart, and that these culminated in the Allied decision to treat with him more formally. Political and humanitarian factors had temporarily suspended military operations. Although no written order seems to have been issued (probably for fear of misinterpretation), verbal instructions were circulated on the evening of 27 April that from 8:00 a.m. the next morning the enemy would not be fired on unless he was taking offensive action.85 This was in fact the end of active hostilities on the 1st Corps front.

The first official meeting between Allied and German authorities took place in a schoolhouse at Achterveld on 28 April. Major-General Sir Francis de Guingand, Chief of Staff 21st Army Group, represented the Supreme Commander; Lieut.-Gen. Foulkes, commanding the 1st Corps, and Brigadier C. C. Mann, Chief of Staff First Canadian Army, were present.* A judicial official, Reichsrichter Ernst Schwebel, and Dr. Friedrich Plutzer were the reichskommissar’s delegates, and a senior Russian officer held a watching brief for his government. The Allied proposals for bringing relief supplies into the western Netherlands were explained to the Germans, but they lacked authority to make definite commitments. Accordingly, a second meeting was arranged for the 30th, to be attended by Seyss-Inquart in person.86

At the meeting on the 30th Lieut.-General W. Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, represented his principal. The reichskommissar, who afterwards claimed that he had not requested authority from Berlin in order to avoid a refusal,87 accepted the Allied proposals in outline and staff arrangements were then worked out in detail. It was agreed that food would be introduced into the “B-2” area (above, page 582) by air, sea, inland waterways and road. Special provision was made for Allied teams to assist the Dutch medical services and the enemy agreed that no further flooding would take place.88 General Foulkes discussed with General Plocher of the 6th Parachute Division the terms under which convoys by land and water could enter the German lines. Plocher was, however, reluctant to conclude details without reference to higher authority.

At this point General Foulkes stated that he had had enough. What he wanted was a military commander who had authority to deal with him on his terms, not merely a divisional commander whose sector did not take in the whole front. A request was made that either General Plocher should be given the authority by General Blaskowitz [the military commander in the western Netherlands] or that the latter should come down and meet General Foulkes and thrash out the whole question. After some hesitation General Plocher agreed to this.89

On the following day these difficulties were resolved at a meeting between the Corps Commander and Lieut.-General Paul Reichelt, Chief of Staff to Blaskowitz. A corridor was created, extending south from the railway linking Arnhem and Utrecht to the Waal at Ochten, for the passage of supplies. “Within these bounds there would exist a temporary truce until such time as the feeding arrangements had been concluded.”90 Foulkes explored the possibility of extending the area of

* The proceedings at this and subsequent conferences are described in some detail in General de Guingand’s Operation Victory, 445-53. A representative of the 2nd Tactical Air Force was also present in connection with the dropping of food supplies.

the truce north to the Ijsselmeer; but Reichelt had no power in the matter and the subject was reserved for further consideration. The Corps Commander immediately issued a “stand fast” order to all troops on his front; patrolling would cease and only “local defensive measures” would be maintained. Particular care was taken to ensure that our troops thoroughly understood the “peculiar situation” on their front.91 Pending the outcome of negotiations with the Germans, Canadian authorities had made further preparations to deal with the Dutch emergency. By 26 April First Canadian Army was ready to move a total of 1600 tons of food daily into the distressed area: 700 tons could be brought by road from ‘s-Hertogenbosch to Ede; 300 could be supplied by road and rail to the vicinity of Amersfoort and 600 could be moved by railway and barges from Nijmegen to Renkum, or downstream on the Neder Rijn. It was anticipated that the easiest method of transport would be by road, in spite of the bottleneck of the bridges at Arnhem.92

Meanwhile, the 21st Army Group had arranged for shipping various supplies by sea from Antwerp to Rotterdam.93 One item to be provided in this manner was coal, which was urgently needed to provide both electrical and steam power. It was estimated that 300 tons would be required daily in the B-2 area during the first 10 days of relief, rising to 4000 tons per day at a later period.94

The immediate problem of getting food to the starving population was met by the free dropping of food packages from Allied aircraft. This began even before negotiations with Seyss-Inquart were completed. On 24 April the Combined Chiefs of Staff had approved plans for air supply, and SHAEF ordered the operation to begin on the 28th; but bad weather postponed the first flight until the following day, when 253 aircraft of the RAF Bomber Command dropped over half a million rations close to Rotterdam and The Hague. Later the Eighth Air Force joined in the work. This relief continued on a rising scale and, during the period ending on 8 May, over eleven million British and American rations were dropped into the B-2 area. Due to the fact that the rations had been packed in bulk (most of them were originally intended for camps of Allied prisoners of war), some delay occurred before they could be distributed as individual civilian rations.95

Canadian arrangements for bringing supplies into the distressed area by land were coordinated by Colonel M. V. McQueen, Deputy Director of Supplies and Transport at Headquarters 1st Corps. The operation, known as FAUST, was carried out by a special organization of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps 1st Corps Troops (aided by units of the Royal Army Service Corps) under Lt.-Col. E. A. DeGeer. He set up his headquarters between the Canadian and German lines and at 7:30 a.m. on 2 May the first 3-ton trucks began deliveries to a depot at Rhenen, on the Neder Rijn. By the following day the operation was in full swing, with convoys of 30 vehicles crossing the truce line every 30 minutes.96 Twelve transport platoons (eight Canadian and four British), comprising 360 vehicles, delivered approximately 1000 tons of supplies daily until the 10th, when the FAUST organization was disbanded and responsibility for delivery passed to the 6th Lines of Communication, under the supervision of the 1st Canadian Corps.97

Map 14: The Final Phase, 2nd Canadian Corps Front, 23 April-5 May 1945

As our Civil Affairs officers moved into the western Netherlands they found conditions, though deplorable, not quite so grave as had been feared. Brigadier Wedd reported:98

The picture appears to be that while a state of acute general starvation as feared had not been reached at the time of the entry of our troops, the state of food supplies would indicate that this catastrophe had only been avoided by a matter of two or three weeks. ... It is probable that there are many cases of people suffering from starvation in their houses. Reports would indicate that death from starvation has been confined to the very old, the very young and the very poor. Conditions appear to vary in several cities with Rotterdam as probably the worst.

Subsequent reports indicated that there were between 100,000 and 150,000 cases of starvation oedema, with a death rate of ten per cent, in the larger centres of the B-2 area. Steps were immediately taken to supplement civilian rations with food from the agricultural areas of the north-eastern Netherlands. The lack of food had not resulted in any marked increase of disease; this was fortunate, since many centres were short of medical supplies. Again, water systems were intact in the “B-2” area, although the pressure was low in some localities; the main electrical generating plants were also found undamaged, but they required large quantities of coal to produce power.99

German action in flooding large sections of the country, before the truce, had seriously damaged the Dutch economy. The worst areas were in the Wieringermeerpolder and about Utrecht. It was anticipated that lowering the Ijsselmeer would assist drainage; but time was required. since the enemy had destroyed the raising gear for sluice gates weighing 12 tons each. Experts estimated that between three and four weeks would be required to drain the flooded areas in Utrecht province.100

Headquarters Netherlands District had gone back under Headquarters 21st Army Group on 1 May; but the Canadian authorities remained in charge of relief measures until the 12th, when the District assumed full responsibility for the relief and rehabilitation of the provinces of North and South Holland and Utrecht.101 By that time the immediate crisis was over. The Canadians could, therefore, relinquish their task with the satisfaction of having made a significant contribution to the solution of one of the war’s most difficult and tragic problems and to the relief of a friendly people who had suffered much.

The German Surrender

At 12:55 p.m. on 4 May Brigadier Belchem of Field-Marshal Montgomery’s headquarters telephoned General Crerar, advising him of negotiations then being conducted between the Field Marshal and representatives of Admiral Dönitz, who had assumed Hitler’s titular authority after the Führer shot himself on 30 April. These negotiations were directed towards “the unconditional surrender of the remaining German forces in NW Europe”.102

The overtures leading to this development are a relatively familiar story.103 As early as March German feelers had been put out, through the British Embassy in Stockholm, in a futile effort to reach a separate agreement with the Western Powers excluding Russia. Later indications suggested that many senior commanders, including

Field-Marshal Ernst Busch (who on 6 April had been appointed Commander-in-Chief North-West, with authority which may be roughly defined as covering the troops opposing the 21st Army Group) were willing to talk terms. The final stages of the enemy’s disintegration began with the formal capitulation of all German forces on the Italian front on 2 May. A German delegation arrived at Montgomery’s headquarters on the morning of the 3rd.

Before Belchem’s call, General Crerar was “already aware” of the negotiations, but had received no instructions or authority to suspend operations.* Now Belchem explained that the German delegates had heard that the garrisons of Jever and Aurich had been summoned to surrender “with the alternative of immediate assault”. They had asked that the assaults should not be made while the negotiations proceeded. Montgomery had agreed, and now asked Crerar “to withhold, until further word from him, direct assault on those places”. Crerar’s record proceeds, “In the meantime, reconnaissance and improvement of positions of troops under my command could go on.”

The Army Commander immediately telephoned Brigadier Rodger, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Canadian Corps, and instructed the Corps “to call off any planned assaults on the towns of Jever and Aurich by 1 Pol Armd Div and 3 Cdn Inf Div pending further instruction”. Our troops’ activities in the meantime were to be “limited to reconnaissance and the improvement of their dispositions”. The General Staff diary of Headquarters 2nd Corps records the order thus: the negotiations would probably be concluded satisfactorily by evening; in the meantime, “our divisions were not to become involved in any assault against a German-held position”. However, there is no record of any division other than the 3rd Canadian and the Poles receiving a cautionary order; and the former recorded, “we are not to assault Aurich. It is permissible to do anything else. Other plans will carry on as per schedule.” General Crerar explained the latest developments to General Foulkes (whose operations had already been suspended) when the Army Commander flew to Apeldoorn in the afternoon.104

The long-awaited news of German capitulation eventually reached General Crerar at 8:35 p.m., first by announcement from the British Broadcasting Corporation and, immediately afterwards, by the official signal from Headquarters 21st Army Group.105 Under the Instrument of Surrender signed at Montgomery’s headquarters, the German Command agreed to “surrender of all German armed forces in Holland, in north-west Germany including the Frisian Islands and Heligoland and all other islands, in Schleswig-Holstein, and in Denmark, to the C-in-C 21 Army Group.106 All hostilities were to cease at eight o’clock the following morning (5 May). In quick succession the German forces in southern Germany and Austria accepted the terms of capitulation, and at Rheims, in the early hours of 7 May, General Jodl surrendered all German forces to the Supreme Allied Commander.

* Field-Marshal Montgomery’s memory has evidently deceived him when he writes in his Memoirs that, in order to avoid casualties, “I had ordered all offensive action to cease on the 3rd May when the Germans first came to see me.” Actually, the firm order, “all offensive ops will cease from receipt this signal”, was included in the same message that announced the cease fire for 8:00 a.m. on 5 May; this message was sent out from Montgomery’s headquarters only at 8:50 p.m. on 4 May. It is reproduced in facsimile in the Field-Marshal’s earlier book Normandy to the Baltic.

† The Poles were in fact some 14 miles south of Jever and meeting considerable resistance.

Two days later the surrender was formally ratified at the Russian headquarters in Berlin. German garrisons in the Channel Islands and at Dunkirk gave themselves up on 9 May.107

It had of course been obvious for some time that the end was close. The 1st Corps had had no fighting since 28 April, except for an occasional shot; but on the 2nd Corps sector, and notably on the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions’ fronts, as we have seen, the enemy at some points resisted fiercely to the end, and losses were suffered up to the moment of the order to cease offensive operations.* One of the last Canadians to lose his life was the Protestant chaplain of the Canadian Grenadier Guards, Honorary Capt. A. E. McCreery. On the afternoon of 4 May he set off, accompanied by Lieut. N. A. Goldie, to bring in some wounded Germans whom prisoners had reported nearby. While engaged in this errand of mercy, both officers were killed, in circumstances which remain obscure.108

In general, the final news came to the fighting troops almost as an anti-climax. When the announcement was made on the evening of the 4th men at first found it hard to believe. When it became evident that it was really true, they felt not so much exultation as intense relief. The units’ diaries make it clear that there were no cheers and few outward signs of emotion. The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, the Canadian unit that had paid the heaviest price on the Normandy D Day, which had fought with distinction throughout the campaign and on the last day was still fighting and suffering losses in front of Aurich, recorded simply, “There is no celebration but everybody is happy.”

On the evening of the 4th General Crerar addressed a message to all ranks of the First Canadian Army:109

From Sicily to the river Senio, from the beaches of Dieppe to those of Normandy and from thence through northern France, Belgium, Holland and north-west Germany, the Canadians and their Allied comrades in this army have carried out their responsibilities in the high traditions which they inherited. The official order that offensive operations of all troops of First Cdn Army will cease forthwith and that all fire will cease from 0800 hrs tomorrow Saturday 5 May has been issued. Crushing and complete victory over the German enemy has been secured. In rejoicing at this supreme accomplishment we shall remember the friends who have paid the full price for the belief they also held that no sacrifice in the interests of the principles for which we fought could be too great.

Heavy indeed the cost had been. During the final phase, beginning with the crossing of the Rhine on 24 March and extending to the end of hostilities, Canadian Army casualties were 6298, of which 1482 were fatal. These losses, serious enough in all conscience, were nevertheless light by comparison with those of earlier periods. The Canadian Army’s casualties for the entire North-West Europe campaign beginning on 6 June 1944 were 44,339; of these, 961 officers and 10,375 other ranks gave their lives.110

Others besides Canadians had fought in the First Canadian Army. It is fitting to set down here the best available record of the casualties suffered by British and

* The record shows 60 Canadian Army casualties on 4 May (of which 20 were fatal) and 10 on 5 May, of which three were fatal. Some of those reported as of the 5th may actually have taken place on the 4th.

Allied formations while serving under its headquarters. The figures are chiefly as compiled in June 1945 and are approximate only. The United States figures cover only the 104th US Infantry Division during its time in the Army in the autumn of 1944:111

| Fatal | Wounded | Missing | Total | |

| United Kingdom | 2,611 | 11,572 | 1,898 | 16,081 |

| Polish | 1,163 | 3,840 | 371 | 5,374 |

| United States | 179 | 856 | 356 | 1,391 |

| Belgian* | 73 | 253 | 35 | 361 |

| Czechoslovak | 17 | 105 | 2 | 124 |

| Netherlands | 25 | 91 | 1 | 117 |

| Total | 4,068 | 16,717 | 2,663 | 23,448 |

Messages poured in from all over the world congratulating the First Canadian Army on its contribution to the Allied victory. Field-Marshal Montgomery’s letter to General Crerar deserves pride of place:–112

Tac Headquarters:

21 Army Group.

8-5-45

My dear Harry

I feel that on this day I must write you a note of personal thanks for all that you have done for me since we first served together in this war.

No commander can ever have had a more loyal subordinate than I have had in you. And under your command the Canadian Army has covered itself with glory in the campaign in western Europe. I want you to know that I am deeply grateful for what you have done. If ever there is anything I can do for you, or for your magnificent Canadian Soldiers, you know that you have only to ask.

Yrs always, Monty.

There were also letters from humbler people. One came from Hatert, near Nijmegen:–113

... As a young girl of 19 years, living in this powerful and big world, I wish to inform you about my happiness and to thank you. It was you, General Crerar, and your Canadian troops, who liberated the greater part of our country.

It was your boys who gave their lives and blood, and it was your people who had to accept, in the interest of our country, so many sad reports about sons being “Killed in Action”.

We were very close spectators during your operations in this vicinity. So many times we saw you leaving in your plane, close to the front line, to carry out your hard and difficult task; accordingly, we are not surprised that all your soldiers give you their confidence and respect.

I would like to finish this letter in thanking you once more for our liberation, and may God bless you.

* The Belgian figures appear to cover the entire campaign, although the Belgian brigade was not in First Canadian Army throughout.