Chapter 7: Home Front – 1

Two years of war saw the strength of the Royal Indian Navy expand considerably. On the outbreak of war it had become necessary to increase its size to the utmost and in the shortest possible time. Indian dockyards at once set to work to turn out fast seagoing motor boats for coastal patrol and powerfully armed corvettes and minesweepers for anti-submarine and other duties. Soon every available building slip was occupied. In July 1941 the HMIS Travancore was launched, the first vessel for the Royal Indian Navy to be built in Indian yards, followed in October by the HMIS Baroda while many others were on the stocks. The vessels of this class “Bassett Trawlers” were named, some after various Indian States, others after the chief towns in India, such as Agra, Patna, Lahore. These ships were admirably fitted for minesweeping and patrol duties. There were also built larger ships of the “Bangor” class, used both for minesweeping and anti-submarine duties, motor minesweepers, 72-foot launches, tugs, lifeboats and other craft.

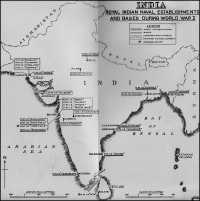

Meanwhile, in spite of her own heavy naval commitments, Great Britain undertook to supply the Indian Navy with some of the larger craft required. Among the vessels then in service or under construction, one class (sloops) were named after the rivers of India, such as the Sutlej, the Jumna, the Narbada and so on. Other naval construction was carried out in Australia. The enormously increased duties imposed on the Royal Indian Navy in connection with minesweeping and patrolling against possible submarines and raiders, and control of contraband, necessitated requisitioning a number of merchant ships also. Many members of the crews of those ships volunteered and were accepted for service. They were brought up to strength by other trained personnel of the RIN and its Reserves. These ships were armed and equipped against mines, underwater, surface and air attacks and put into commission. New naval bases were developed in the ports of Cochin and Vizagapatam, as well as in the older ports of Madras, Karachi, Bombay and Calcutta and from each base the latest anti-submarine and minesweeping craft operated.

The expansion of shipping involved a considerable expansion of personnel also especially technical personnel, so that by the time Italy entered the war in June 1940 the strength of the Royal Indian Navy had increased by nearly 200 per cent, while in 1942 the strength had enhanced to over 600 per cent. This inordinate growth created new and difficult problems of training, which became acute owing to the shortage of qualified instructors and suitable equipment.

Transfer of Naval Headquarters to New Delhi

After eighteen months of war it was realised that the Flag Officer Commanding Royal Indian Navy would have to be stationed in New Delhi, the seat of the Government of India and the Headquarters of the other two Services. Proposals for the transfer of the Naval Headquarters to Delhi or Simla were submitted to the Government of India by FOCRIN on 20 February 1941. Two alternative possibilities were considered: (a) complete transfer of the whole Naval Headquarters with the then existing staff of 23 officers and 35 clerks etc., and (b) transfer of a limited staff only, leaving a proportion of the work to be dealt with in Bombay. As the move had to be rapidly effected and there were difficulties of accommodation at Delhi and Simla, the proposals for transfer were based on the latter alternative only.

Under the arrangement the staff distribution was to be:–

| Delhi/Simla | Bombay |

| Admiral | Commodore |

| Secretary | Captain of the Fleet |

| Staff Officer (Plans) | Director of Personnel Services |

| Staff Officer (Operations) | Engineer Captain |

| Staff Officer (Gunnery) | Staff Officer (Signals) |

| Staff Officer (Admiralty) | Staff Officer (Intelligence) |

| Staff Officer (Engineering) | Staff Officers 2 |

| Signals Officer | Equipment Officer |

| Works Officer | Principal Medical Officer |

| Asst. Staff Officers 2 | Assistant to Staff Officers |

| Cypher Officers 4 | Cypher Officers |

| Administrative Officer | Chief Superintendents |

Government sanction for the moves on the lines proposed above was accorded in February 1941. And the Naval Headquarters moved to New Delhi in March 1941.

March 1941–May 1943

This arrangement was found unsatisfactory as under the existing rules and regulations many problems had to be referred to FOCRIN for his approval or decision, with the result that the planning and operations Staff found themselves forced to deal more and more with matters that were outside their spheres. Hence certain officers, who were stationed at Bombay, and who were nominally supposed to carry out certain specific duties, were brought to Delhi mostly one at a time.

The changes which took place during the period may be briefly described as follows: The Director of Personnel Services was transferred to the Headquarters in March 1942, the Staff Officer Signals in June 1942 and the Equipment Officer also in 1942. The designation of the Engineer Captain at Bombay was altered to Director of Engineering in November 1942. In March 1942 the Staff Officer (Engg.), Equipment Officer, and the Captain of the Fleet were incorporated into one branch known as the Material Branch under the Captain of the Fleet. Subsequently a COF 2 and Equipment Officer 2 were added. Among new branches formed at the Naval Headquarters were the Legal Branch set up in October 1942 with a Deputy Judge Advocate, and the Accountant Branch formed in January 1943, with the Fleet Accountant Officer maintaining an office in Delhi as well as in Bombay. A Welfare Directorate was sanctioned as part of the Directorate of Personnel Services in February 1943.

Towards the end of May 1943, a Chief Staff Officer was appointed and made responsible to FOCRIN for the direction of the work of all the staff of Naval Headquarters which was modest in size consisting of a Captain of the Fleet, a Director of Personnel Services, Director of Accountant Duties, Operations, Intelligence and Plans Staff Officers, Technical Staff Officers, and in addition, the Naval Law and Admiralty sections. The Principal Medical Officer, Royal Indian Navy and the Director of Reserves were located in Bombay. The Naval Secretary had no separate portfolio but acted as Secretary to the Flag Officer Commanding and Adviser to the Staff generally.

This haphazard growth of the Headquarters failed to meet the growing requirements of the Service nor could it keep pace with its expansion. The failure could be attributed mainly to one factor, namely, lack of suitable officers to hold administrative appointments. The Service commenced the war with no Reserve.

Therefore, it had no persons with any naval background. The appointment of persons to naval administrative posts without sufficient background was not a practical proposition, as a knowledge of the Service, its regulations and requirements, and of the customs and usages of the sea was essential.

In drawing up the new organisation for the Naval Headquarters, the analogy of the Admiralty in the UK was followed as closely as possible, but it was not possible to adhere strictly to the Admiralty practice as it was necessary for the Indian naval organisation to correspond generally with the procedure of the Government of India and the existing organisations for the army and the air force so as to achieve smooth collaboration and general uniformity.

Changes in the Method of Recruitment

From 1940 onwards energetic steps were taken to persuade the Government of India to embark on a planned expansion of the Service coupled with a shipbuilding programme. But there was delay in arriving at a decision, and when it was finally taken, the navy was faced with the mighty problem of recruitment and training of the requisite number. The task of securing suitable element for the naval service was made more difficult owing to the competing claims of the army and the air force. The army had a definite advantage, particularly in northern India, owing to the general ignorance of, and indifference towards naval service. The slow and limited growth of the navy in the first two years also contributed to that result. To obtain the numbers required in later years for the navy it became necessary to open up recruitment on an India-wide scale. Large numbers of ratings from Bengal and Southern India were enrolled. Larger number of ratings came from the cities than from the villages of India.

From 1939 up to the end of 1941, two Naval Officers acting independently of any other organisation were responsible for recruitment to the Royal Indian Navy. Later, to obviate any unhealthy competition between the three Services, a joint organisation was established. With it from 1942 every district in India, covered by the machinery of the Inter-Services Recruiting Organisation, became more naval-minded. The Royal Indian Navy employed leaflets and advertising material in important vernaculars. This offset the handicap of the absence of visual naval influence or lack of personal contact. The co-operative spirit between the services in recruiting personnel proved an additional asset for naval recruitment. The elimination of competition between Services achieved

unity of effort, control and economy in establishment and administration. All these factors resulted in a growing response in every district and led to a considerable increase in the recruitment.

The acceleration of the war effort in India, as a result of Japan’s aggression in the East, placed heavy demand on the recruiting organisation. This led to the appointment of 25 Assistant Recruiting Officers (Navy). The appointment of a Deputy Director of Recruiting (Navy) in July 1943 enabled the naval staff attached to the Recruiting Directorate to visit the recruiting areas more frequently, thus keeping abreast of developments and progress of recruitment.

In a voluntary system of recruitment, persuasion and personal contact plays an important part. The increased rates of pay in 1942 helped to improve recruitment during 1943-44. No better stimulation to recruitment existed however than the return to his home on leave of the smartly dressed and contented gating.

Urgent requirements for certain standards of personnel were handled by the allotment of priorities. The Royal Indian Navy’s requirement of educated personnel at the end of 1943 was so serious that overriding priorities were granted by the Government. As a result, the recruitment of educated personnel improved considerably. It was always difficult to strike a proper balance between quantity and quality. When quantity rose, quality dropped and vice versa. Prior to the advent of the Training Directorate in the Naval Headquarters, the standards of entry were not adhered to strictly in practice, as reliance had to be placed on recruiting authorities exercising their discretion and using as a gauge the varying Indian educational standards. Thereafter, however, the tendency was to standardise and simplify tests for all educated recruits.

At the end of 1943 physical standards, particularly height and weight, were revised in order to extend the scope of recruitment to certain branches, as it was found that the peacetime standards were preventing otherwise suitable persons from joining. The Communications Branch and the Supply and Secretariat Branch were chiefly affected.

There being no such distinction as class composition in the Royal Indian Navy, every encouragement was given to recruiting new types and classes. Once fears regarding disparities in food and standards of welfare were eliminated, the main obstacles to increasing recruitment had been overcome. Recruitment from South India, first begun in 1940, caught on in the last two years, and provided the

requirements in the higher educational grades. It was interesting to observe that after 1943, the Sikhs joined up in large numbers. Garhwali recruitment was also initiated but their lack of education was a limiting factor.

An important feature in recruitment often overlooked, was the time-lag. The dissemination of information about terms and conditions of service took long time to reach the masses. When recruitment for any category was stopped, the effect was like that of “drawing fires”. It took two or three months to re-open such recruitment on a successful basis. Experience in the first two years showed that it was never wise to close recruitment to any branch entirely.

The vast size of India and the fact that before the war the Royal Indian Navy itself had no roots from which to draw manpower, made it apparent that the achievements since 1939 and in particular during the first two years were but the first step in a gradual process of making India navy-conscious and navy-proud. Fresh ground was broken and new seed was sown daily, and the soundness of those new connections depended, to a large extent, on the way in which the recruits were handled, treated and trained.

Formation of RINR, RINVR, Fleet Reserve, Etc.

At the end of 1938, the formation of the Royal Indian Naval Reserve (RINR) from gentlemen with sea-faring experience, and of the Royal Indian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RINVR) from those with no such experience, was sanctioned. At the beginning of the war there were no RINR Officers. There were only 21 Executive and 16 Accountant Officers of the RINVR apart from the regular RIN Officers. The creation of a Royal Indian Fleet Reserve was sanctioned later. It was intended to form this Reserve from ratings retired from active service. There were no men in the Fleet Reserve at the commencement of the war.

The whole administration was carried out by a small staff, duties not specifically provided for, such as those of Squadron Accountant Officer, Judge Advocate etc., being carried out by one or other of the officers in addition to his own duties. This system worked adequately, but was not designed to cope with the volume of expansion that followed. With the outbreak of the war Naval Officers-in-Charge with other Staff Officers were appointed in Bombay, Calcutta, Cochin, Madras and Karachi. Moreover, it became necessary to requisition and to man a number of merchant vessels for mine-sweeping, patrol work etc. No less than 31 such vessels were put

into commission in the first two months of the war. Personnel for them had to be found immediately.

An excellent response to the call for volunteers for the RINR came from Indian officers of the Mercantile Marine, most of whom had been cadets of the IMMTS Dufferin. At the outset much support came from the city of Bombay for the RINVR This was followed by an adequate response throughout the country. The selection of candidates from the Far East was also effected to the Volunteer Reserve.

The trend of in-take of officers during 1942 and 1943 showed steady increase in the proportion of Indian officers entering the Service as compared to officers of non-Indian domicile. During 1944, when 498 officers were selected, only 141 of those were European as against 357 officers of Asian domicile, a ratio of 2.5 Indian officers to 1 European Officer.

Establishment of Selection Boards & their Absorption in the Recruiting Directorate

Before the war, officers for the three Services used to be selected on the result of a competitive examination and an interview conducted by the Federal Public Service Commission. The number of Indian officers thus selected annually before the war was relatively small and no difficulty was experienced in filling the vacancies in this manner. Some time after the outbreak of the war selection for permanent commissions was closed and a system of granting temporary commissions was introduced. The demand for officers, both Indian and British, increased considerably and selection of officers for the three Services was taken over by the respective Service Headquarters. Each Service formed an Interview Board. These boards either called the candidate to one central place or toured round the country in order to interview them. Selection was made on the result of an interview for not more than half an hour by one or more members of the Selection Board. This continued until the beginning of 1942 when it was decided that selection of officers to the three Services should be integrated and carried out by the Directorate of Recruiting in the Adjutant General’s Branch at the Army Headquarters.

After this integration the selection of candidates was conducted in two stages (i) preliminary selection by Provincial Selection Boards and (ii) final selection by the Central Interview Boards. While all officers for the army were selected through this integrated organisation, the Royal Indian Navy continued to take in a number

of candidates under their own arrangements and the Royal Indian Air Force appointed a few General Duty Recruiting Officers who were authorised to recommend candidates direct to the Central Interview Boards.

The Provincial Selection Boards were generally presided over by a Senior Civil Officer of the status of a Commissioner of a Division who was assisted by police, military and other civil officers. The method of selection adopted by these Boards was not uniform. Generally speaking, these Boards could devote only one or two days in a month for interview purposes. This sometimes necessitated Boards interviewing candidates in large batches. The final selection of the candidates recommended by the Provincial Selection Boards was made by the Central Interview Boards. These were three in number, one for the north, one for the south and one for the central India. The Central Interview Boards normally consisted of a senior civilian as President and a senior Indian army officer as Vice-President and two co-opted local civilian members.

The system adopted by the Royal Indian Navy for the three types of Commissions is indicated below:–

| Course or Entry etc. | Arm/ Branch/ Corps | Type of Commission | Preliminary Selection | Final Selection | Remarks |

| Inter-Services Wing | All | Permanent | F.P.S.C. Examination | Services Selection Board | 2 Courses a year |

| Cadet Entry (for training in U.K.) | All | -do- | -do- | -do- | 3 times a year but later twice a year |

| Direct Entry (Commission from the date of appointment.) | All | Short Service for 5 years | N.H.Q. | -do- | Suitable Officers to be absorbed in the regular cadre later. |

Formation of Personnel Selection Boards – Their Work at Lonavla, Meerut and Bangalore

Opinion was expressed that a short interview was completely inadequate for testing the suitability of an individual to be an officer.

It suffered from the inherent defect of the personal equation of the interviewer and it was, therefore, impossible to obtain a uniform standard. Moreover, the candidates were not expected to have any confidence in the justice of the system of personal interview. These were considered to be largely responsible for sufficient number of men not offering themselves for commission, and complaints and questions in the Legislative Assembly became frequent. It was also noticed that a large proportion of candidates selected by the method of personal interview failed to qualify for commissions at the Officer Training Schools. In the latter part of 1941, experiments were carried out in England, and a system, calculated to test more satisfactorily the various qualities such as leadership, intelligence, stamina, etc. of the candidates was devised. This system was evolved as a result of considerable amount of research work and was based on scientific methods which had been advocated by psychologists and others for a long time.

The question of adopting the War Office system of selection in India was taken up. As a result of correspondence with the War Office, a team of officers consisting of a Deputy Director of Selection of Personnel at the War Office, two Psychiatrists, two Psychologists and one Military Testing Officer (now known as the Group Testing Officer) arrived in India early in 1943. Considerable doubt was expressed by the War Department in India as well as by the General Headquarters as to whether the application of the British system to Indian candidates would be desirable. The main fear was that it might frighten away the candidates whose number and quality were already falling rapidly. However, it was ultimately decided to establish a separate Selection Board to apply the new technique as an experimental measure. The first Board was opened in Dehra Dun in February 1943. It contained most of the Intelligence Tests, but no Personality Tests and Group Testing. It was described later as “a bit half-baked”, but nevertheless, it was a start. A small section to deal with the new technique of selection was also created in the Recruiting Directorate of the General Headquarters.

In March 1943, again a specialist officer and a few psychologists and psychiatrists arrived from the United Kingdom and re-organised the Dehra Dun Board. By mid-April, it was running along more orthodox lines. It was visited by the Defence Consultative Committee, the Adjutant General in India and other prominent authorities. In May, permission was given to form other Boards. In July 1943, it was agreed that all selection of officers for the three Services would be handled by these Boards. The next two months were

spent in raising staff, and in September four Boards were opened, followed by a fifth in November, a sixth in January 1944 and a seventh in March 1944 for the IAF. A combined Services Selection Board was opened at Lonavla in June 1944. There were then Boards at Dehra Dun, Rawalpindi, Calcutta, Jubbulpore, Meerut, Bangalore, Manora and Lonavla. A Board was also formed at Dehra Dun for the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (India).

In the matter of the other ranks the Personnel Selection Directorate had a rather more difficult task. It arrived in India with all the tests which had been used for British other ranks but it was immediately found that these were valueless in India owing to the language problem, and to the lack of education, especially among army recruits. Consequently, it became necessary to start from the scratch and devise a large new series of tests suitable for application to Indian recruits. Plans were also formulated to set up Boards at HMIS Akbar or at the Recruits Reception Camps. When that took place, the system of recruiting men as Writers, Seamen, Stokers etc. ceased, and all recruits were merely recruits for the navy, who were tested to find out in what direction their- aptitudes lay and then drafted to the appropriate Branch Training Establishments.

Early in 1944, it was decided that all officers of the Royal Indian Naval Reserve (RINR) and Royal Indian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RINVR) of the rank of Lieutenant and under, should be tested by a Personnel Selection Board and for that purpose the Board at Lonavla was set up. Its aim was partly to obtain full records regarding each officer, and partly to find out which of them would be considered fit to hold Permanent Commission in the RIN after the war. It may be of interest to note that the first Indian Naval Officer to be appointed on the Staff (as Senior Group Testing Officer and then Deputy President) of the Services Selection Board at Lonavla was the then Ag. Lt. Cdr. R.D. Katari, RINR, who subsequently became Vice Admiral R.D. Katari, Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy.

Recruitment Under National Services Act (European Subjects)

At the outbreak of the war, the RIN was in a favourable situation for the recruiting of European officers to the Reserve. Unfortunately official sanction for filling the vacancies was not available readily; volunteers released from civil employment were unwilling to wait and many gentlemen with yachting experience or engineering qualifications, invaluable for the navy, found their way into the other Services.

During the period 1942-43 permission was obtained from the Adjutant General to secure from the Officers Training Schools volunteers wishing transfer to the Navy. This method provided a large percentage of candidates, but the War Office objected to the transfer to the Navy of European Cadets ex-United Kingdom, hence as far as those were concerned recruitment was stopped.

Commission from the Lower Deck

To encourage young men to enter upon a career in the RIN, educational, recreational and various other facilities were provided to the ratings. In addition, a scheme for promotion of Continuous Service ratings to Permanent Commissioned Rank in the Royal Indian Navy was introduced under RIN Instruction No. W of 1942. The scheme, however, did not succeed mainly because only one commission was offered per annum to be competed for by Seamen, Signal and Telegraphist ratings, Stoker ratings and Engine Room Artificers, and also because ratings of other branches (e.g.) Writers, Ordnance Artificers, Electrical Artificers etc. were not catered for. No rating was promoted under that scheme.

In 1944, another scheme for promotion of Continuous Service, Special Service and ‘Hostilities Only’ ratings to temporary commissions in the Executive, Special, Engineer, Electrical and Accountant Branches of the Royal Indian Naval Volunteer Reserve was introduced by RIN Instruction No. 125 of 1944. The main qualifications for a candidate for promotion were as follows:–

a. must be within the prescribed age limits,

b. have passed the educational test, (Higher Educational Test)

c. have completed six months’ sea time,

d. have passed the Final Passing-out test,

e. have been recommended for promotion by the Passing-out Board, and

f. have passed the medical test.

In all ten ratings were promoted under this scheme. These were the first commissions ever granted to the Lower Deck and marked an important milestone in the history of the RIN.

Out of the ten candidates for commission, six were for the Executive Branch, two for the Supply and Secretariat Branch and one for each of the Engineering and Electrical Branches. Initial training of these candidates was carried out in HMIS Akbar.

During the first month all candidates underwent the same instruction in the duties of an officer and deportment, general seamanship and discipline. At the end of the first month, non-executive candidates left HMIS Akbar to continue their training in specialised subjects at the Accountant Training Establishment and the Mechanical and Electrical Training Establishments. The Executive candidates remained at HMIS Akbar to complete their twelve weeks’ course. On passing that course they were all promoted to commissioned rank.

Electrical Branch

An Electrical Branch was sanctioned in 1942. In 1943, recruitment was made from among Indian students at Faraday House, the Civil Electrical Training College, in London. To co-ordinate all matters relating to torpedoes, mining and electrical subjects, a Staff Officer (Torpedo and Mining) was appointed to the Naval Headquarters in November 1943. In March 1944 a Torpedo Officer was appointed for duties on the east coast (on the staff of the Commodore, Bay of Bengal) and one for the west coast (on the staff of the Flag Officer, Bombay). The need for a qualified Electrical Officer at Naval Headquarters became apparent and an Electrical Officer of Commander’s rank was loaned by the Admiralty in December 1944. The number of Electrical Officers borne increased from 25 to 58.

Special Branch

In order to permit the employment of officers in naval shore appointments who were specially qualified in a particular sphere or suitable for the executive commission but did not possess a sufficiently high standard of medical fitness, a Special Branch was formed in the Royal Indian Naval Volunteer Reserve in May 1943. The first Indian Officer to join that Branch was Lieut. (Sp) C. B. Sethna, OBE, JP, RINVR

Medical Branch

In 1943 the Medical Branch was formed from the then existing organisations of Indian Medical Service and Indian Medical Department. Up to July 1943 the Principal Medical Officer, Royal Indian Navy, though on the staff of the Naval Headquarters, was located in Bombay and there was no Staff Medical Officer at Naval Headquarters, in New Delhi. In July 1943 the Principal Medical Officer transferred his Headquarters from Bombay to New Delhi. In

November 1943 the appointments of Deputy Principal Medical Officer and Naval Staff Surgeon were created on the staff of the Flag Officer, Bombay. In March 1944 an Assistant Principal Medical Officer was added to the Medical Branch, Naval Headquarters. In September 1944, a Naval Health Officer was appointed to Bombay. The first Principal Medical Officer was Surgeon Captain G. Miller, RIN. He was succeeded by Surgeon Captain P. M. Mc. Swiney in January 1945. In March 1943 the strength of the Medical Branch amounted to Medical Officers 45, Sick Berth Attendants 405. In March 1945 the strength had increased to Medical Officers 92, Sick Berth Attendants 607 and Nursing Sisters 19. The first Naval Hospital in India, the Royal Indian Naval Hospital, Sew/i, Bombay, containing 250 beds, was opened in May 1943. Expansion by another 100 beds took place within the next year. In 1944 a Dockyard Workers’ Families clinic was opened in Hornby Road, Bombay. The popularity and success enjoyed by that clinic was in a large measure due to Dr. S. Gore, the Lady Doctor-in-Charge, who possessed a special knowledge of welfare requirements amongst labour classes in Bombay.

Schoolmasters Branch

Education in the Navy, as distinct from the professional training, began in the service in 1928. In 1935 the total Schoolmaster Cadre was 9. In 1938 the RIN obtained on loan from the Admiralty the services of a Headmaster/Lieutenant. At that time there were Chief Petty Officer Schoolmasters with degree qualifications on very low rates of pay, at the Boys Training Establishment, the Signal School and the Mechanical Training Establishment. It was imperative now to increase the cadre of schoolmasters and to raise their status and their pay. Later in 1941, the cadre was increased to 54 Schoolmasters which included 10 Warrant Schoolmasters. By February 1944, a great advance was made in that sanctions were obtained for a Headmaster/Commander as Deputy Director of Education, one Headmaster/Lieutenant at HMIS Bahadur, one Lieutenant (Sp) Assistant Deputy Director of Education, four Headmasters/Lieutenants, (RINVR), 40 Commissioned Warrant Schoolmasters and 180 CPO Schoolmasters and increased rates of pay to CPO Schoolmasters. Much difficulty was experienced in selecting suitable men in 1941-43, but the improvements in status and pay greatly eased the situation. Schoolmasters were borne in Castle Barracks, Mechanical Training Establishments. Talwar, Akbar, Hamla, Hamla II, Machlimar, Valsura, Bahadur and Dilawar. Others were attached to Recruit Reception Camps at Jhelum,

Meerut, Bangalore etc., and to the Recruiting Organisation itself. There were 10 sea-going appointments, including all sloops.

With the strengthening of the Branch, education within the Service made strides, and at the end of 1944, the RIN Educational Tests compared favourably with those of the Royal Navy, being higher in some respects, whilst the standard throughout the service had risen. An Instructor Branch was added to the then existing Schoolmaster Branch. Both the existing and the newly selected Instructor Officers were eventually appointed to a number of Training Establishments.

Officers of the new Branch ranked as Instructor Lieutenants and Instructor Lieut. Cdrs/Commanders of the RINVR Their uniform had distinctive cloth of light blue between the gold stripes.

Accountant Branch

Early in 1943, it became apparent that the Royal Indian Navy was noticeably deficient in the services of a well-organised and well-trained Accountant Branch to carry out duties in connection with pay, victualling, clothing, stores etc., duties particularly essential for the smooth running of the business side of a naval service. This Branch was practically non-existent before the war, and those officers and men who volunteered from civil occupations had no one of experience to guide and instruct them. The result was that accounts were getting into a muddle, and Commanding Officers were becoming submerged in a stream of queries and objections with which they were unable to cope. There were also no trained or experienced Secretaries or Accountant Officers to assist them, and the situation was becoming serious. The Admiralty, therefore, agreed to loan a Senior Accountant Officer, to re-organise the Branch and produce a curriculum of training and an orderly system of accounting. This move proved to be very beneficial, and resulted in an all-round improvement of the Branch. Selection of officers and recruitment of men received special attention. Although the establishment of a permanent cadre of officers and men in this Branch was then (1944) under consideration, steps were taken to build up the organisation on sound lines and to earmark personnel whose services were required for retention after the war. The intake of ratings left much to be desired. A small and steady flow was nevertheless forthcoming, and an energetic recruiting drive was launched. A training establishment was set up in Bombay at Fort Barracks. Other measures taken to provide for an efficient organisation were (a) the establishment of a separate Directorate at Naval Headquarters

and the appointment of travelling Staff Officers to inspect accounts on the west and east coasts, (b) improvements in the conditions of service and advancement of officers and men, (c) separation of officers’ cooks/from ships’ cooks, (d) separation of Writer ratings from Stores ratings.

A centralised system of pay accounting was worked out and it was intended to apply that to the pay accounts of all Royal Indian Navy Officers and men as soon as the necessary office accommodation, staff and equipment were provided. To conform with the Admiralty practice, the title of the Accountant Branch was altered in 1944 to Supply and Secretariat Branch and officers and men were re-designated accordingly. The uniform of the officers had the distinctive cloth of white between the gold stripes. By the end of 1944 the Branch had been established on a satisfactory basis. Attention to matters such as pay, food and leisure are three factors that count most in the maintenance of morale. Neglect of these matters has in the past led to disaster. These now became the peculiar responsibility of the Supply and Secretariat Branch.

Training of Officers – HMIS Feroze

Reference has been made in an earlier chapter about the difficulties of training Reserve Officers at the outbreak of war. There was no Officers’ Training School. “There was no accommodation in the Barracks for Officers under training, some of whom were accommodated in the RIN Mess and some of whom lived out in private billets. The whole position was unsatisfactory; there was no mess life and officers dispersed to private life after working hours each day”.1 All courses for the trainee Officers were then each of three weeks’ duration only, except the Anti-Submarine Courses which were of one week. In 1941 part of the training was transferred to Castle Barracks. In May 1943 the duration of courses except Anti-Gas and Divisional was increased to four weeks. Reserve Executive Officers received a month’s Seamanship, a month’s Navigation and Divisional and Anti-Gas Courses at Castle Barracks, while Signals, Anti-Submarine, Torpedo and Gunnery Courses were carried out at the Specialist Schools.

In November 1943, the situation improved substantially with the commissioning of HMIS Feroze. This was a building on Malabar Hill, Bombay, and had formerly been the temporary location of HMIS Himalaya. It followed as far as possible the

India – Royal Indian Naval Establishments and Bases during World War II

lines on which HMS King Alfred and HMS Good Hope were run. Officers were accommodated on the premises, and thus became subject to a more continuous Service environment. All officers entering the RIN were required to do at Feroze at least four weeks’ Divisional Course and to undergo courses in Urdu, Physical Training etc. Other courses were also carried out either at Feroze or at the Specialist Establishment concerned.

During 1944 there was close collaboration between the Director of Recruiting, Selection of Personnel Directorate (both at Meerut) and Naval Headquarters concerning the application of ‘selection of personnel’ methods and selection of officers of the Royal Indian Navy, to ensure better quality of candidates for the Service. The fundamental weakness in the system of entry of officers however remained. Unlike the Indian Air Force and the Indian Army, officer candidates for the Royal Indian Navy entered on a temporary commission as officers, and once in, there were no severe penalties attaching to failures in their course, and the Service was committed to retaining them once they had been confirmed. Courses were held for Warrant Officers and for Lower Deck Personnel selected for promotion to commissioned rank. The total accommodation at HMIS Feroze on V-J Day was for 200 officers and 200 ratings.

Other Training Establishments

Other Training Establishments for Officers were2:–

HMIS Akbar, Kolshet, Bombay. Here Divisional Courses for candidates for temporary RINVR Commissions (full course of 12 weeks for Executive candidates) and Divisional Courses for Warrant Schoolmasters (ex-Chief Petty Officer Schoolmaster) were conducted.

HMIS Himalaya, Karachi. In April 1943, as it was no longer possible to continue Gunnery Training in the overcrowded Bombay Dockyard area, the Royal Indian Naval Gunnery School was temporarily established in a large leased house known as “111 Palazzo” on Malabar Hill, Bombay. This was a makeshift arrangement until the school could be accommodated at its new site in Karachi. The instruction given at Malabar Hill was largely for practical firings at sea owing to lack of facilities. One of the Navy’s most ardent admirers, Honorary Lieutenant Commander Sir Dinshaw Petit, Baronet, RINVR, placed a portion of his residence at Malabar Hill at the disposal of the Royal

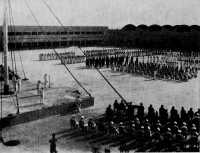

Indian Navy. A number of typical close-range guns were immediately mounted and practical anti-aircraft firing practice became possible under his supervision. Very few low-angle full-calibre practice firings were carried out in Bombay during that period owing to the non-existence of a Gunnery School firing ship and to the fact that other suitable ships were being continuously employed on convoy and other operational duties and were consequently not available. During 1943, rapid progress was made at Karachi in the completion of the new Gunnery School and the opening ceremony of HMIS Himalaya was performed by Vice-Admiral Godfrey, Flag Officer Commanding Royal Indian Navy, on 26 November 1943.

HMIS Himalaya was probably the most modern naval gunnery school of its type in existence outside the British Isles. It was equipped to train officers and ratings in all aspects of gunnery up to 4-inch guns and modern sloops. A firing point of 350 feet in length was provided for practical high angle and low, angle firings to seaward. At the end of 1944, HMIS Lawrence was allocated to HMIS Himalaya as a Gunnery School Firing Ship.

Long and short gunnery (“G”) courses were started in HMIS Himalaya. But, in order to provide suitable officers to man the ships and the gunnery establishment of the Royal Indian Navy, the policy of deputing Lieutenants, Royal Indian Navy, to specialise in gunnery in HMS Excellent (Whale Island) continued. Nine RIN Officers received training in HMS Excellent while eighteen Reserve Officers qualified in HMIS Himalaya. Apart from the normal service training programme undertaken, HMIS Himalaya trained a number of Bombardment Liaison Officers and Forward Observation Officers of the Royal Artillery for duties with the British Pacific and East Indies Fleets.

HMIS Talwar, Colaba, Bombay

This was commissioned in the latter part of 1943 and trained mostly Communication ratings. It was known as the Signal School or the Colaba School. Later, it undertook Radar Officers’ Long and Short Communication Courses. It also gave training to WRINS (Women’s Royal Indian Naval Service) Officers. Some Instructors were loaned by the Admiralty but the majority were RINVR Officers who had received training previously in this branch.

HMIS Machlimar

Enough has already been said to indicate the acute shortage of accommodation with which Training Establishments were faced in

the earlier war years. The Anti-Submarine School, when first opened in the Dockyard in July 1939, also suffered from the same limitation. Transferred to Castle Barracks in 1941, it eventually carried out a further move to Varsova, 19 miles from Bombay, where a modern school building was constructed. Instruction began there in April 1943, the School being commissioned as HMIS Machlimar.

To meet the Japanese submarine offensive efficient anti-submarine training was organised. HMIS Machlimar had equipment sufficient so enable it to teach the highest anti-submarine course for officers and ratings in all types of Asdic sets fitted in the Royal Navy, Royal Indian Navy and the Dominion Navies. Instruction closely followed the syllabus of HMS Osprey, the antisubmarine school in Britain. The Officers’ Long Asdic course lasted five months whilst all officers were required to undergo a three weeks’ short course, and it was possible to train 220 officers and ratings at any one time. However, the policy continued for RIN officers to be sent to the United Kingdom for long courses, mainly to obtain up-to-date anti-submarine knowledge on problems under research and for liaison purposes with the Royal Navy.

HMIS Machlimar was sanctioned as a joint enterprise with the Royal Navy, the intention being to train a certain number of Royal Navy ratings there. However, owing mainly to administrative problems peculiar to the Eastern Fleet, the Royal Navy part of the school could not work in full strength. During the final stages of the war, no changes were made in HMIS Machlimar. The school had attached to it for training purposes the old Dutch Submarine K-ll. Although useful for want of something better, the vessel was obsolete and frequently out of use. HMIS Ramdas was attached as Tender to the Machlimar in 1943. In 1945, HMIS Gondwana became the Anti-Submarine Training Ship and HDML 1084 was attached to HMIS Machlimar for similar duties. During the summer of 1945 some difficulty was experienced in carrying out anti-submarine training at sea as accommodation for the crew of a Royal Navy or Dutch submarine was not available in Bombay or on the Kathiawar Coast during the monsoon.

Facilities for anti-submarine training also existed in the major ports of India. In Bombay, an Anti-Submarine Tactical Training Unit was established on lines similar to the Western Approaches Tactical Unit at Liverpool. Officers of ships equipped with anti-submarine weapons were trained in the latest tactics of underwater

warfare and courses were kept constantly up-to-date. The Naval Headquarters undertook the printing of “Instruction for Installation Publications for the Eastern Theatre”. Negatives and sample copies were received from the United Kingdom and reproduced in Delhi for distribution in India and to the East Indies stations.

HMIS Chamak. Until June 1943 the Royal Indian Navy had no qualified Radar Officers. Training was carried out at the Signal School with one Type 286 set and an incomplete 285 set, the instructor being a Warrant Telegraphist who himself had . no specialised training in these matters. Later, a qualified Radar Officer was obtained from the Admiralty and he imparted instruction, but the general standard of those passing out was not adequate. Subsequently, 2 RIN officers who had qualified in South Africa joined the instructional staff. In November 1943, when the old sloop Cornwallis was commissioned as a tender to Talwar, it was fitted with such radar apparatus as was available.

In 1944, it was decided to build a new Radar School at Manora as the site of the Signal School (HMIS Talwar) was found to be unsuitable for radar training. The new school – HMIS Chamak was to be fitted with all radar sets in use in the RIN vessels together with workshops both for overhaul and for the training of radio mechanics in the upkeep and maintenance of radar units. The school was expected to have the newest testing equipment, teach fighter direction, and contain the Action Information Centre. Construction was delayed, but she was finally commissioned in June 1945 a<nd all radar training was concentrated there. Further, extension was sanctioned at the end of the war to accommodate the latest radar and plotting equipment.

In August HMIS Madras was allocated as radar training ship, and after three months’ conversion, made her first radar training cruise. At the end of the war she was in the process of being refitted with the latest radar equipment found in sloops and with an Action Information Centre of the sloop type. HMIS Karachi, a Basset trawler based on Karachi for local duties, was frequently employed on radar training and HDMLs 1261 and 1262 were also allotted for those duties.

The main difficulties in radar training were acute shortage of instructors and lack of equipment. In 1944 two Petty Officers (Radar) Royal Navy were lent to the Royal Indian Navy as Instructors whilst two RINVR officers were in the United Kingdom undergoing a radar course. Considerable difficulty, however, continued

to be experienced in the provision of Instructors. The Admiralty was approached but it was also in a similar situation and was unable to spare additional staff. Eventually ten Instructors were loaned and arrangements were made for the secondment to the RIN of a small number of RNVR Radar officers to replace personnel lost by demobilisation.

In June 1945, HMIS Chamak was commissioned. In September the whole situation greatly improved. Through the generosity of the Headquarters, Base Air Force, South-East Asia, arrangements were made for a section of the No. 2 School of Air Force Technical Training, Ameerpet to be placed at the disposal of the Royal Indian Navy and for instructor and instructional equipment to be provided. Results from their school were excellent, and a high standard was maintained.

HMIS Hamla, HMIS Hamlawar and HMIS Jehangir

The Royal Indian Navy Landing Craft training began in November 1942, HMIS Hamla being commissioned at Mandapam (on the extreme southern promontory of India), on 1 January 1943. The Landing Craft wing was formed largely by officers and men transferred from the army. The camp had accommodation for 298 officers, 3,846 men and with additional tented accommodation for another 800 men. In April 1943 the first classes of trainees were half way through their four to five month preliminary training in HMIS Hamla. In June 1943, the first batches of the Hamla product, formed into flotillas, moved to Bombay for their advanced training in the Royal Navy Establishment, HMS Salsette. On completion of those courses men were transferred to Landing Ship Infantry El. Hind, Barpeta and Llanstephen Castle for flotilla training from ships and additional night landing. At the end of 1943, the flotillas in Salsette were attached to Force “G” and were joined by their maintenance parties, trained in the Landing Craft Base at Sassoon Dock, Bombay. That base was entirely manned and run by the Royal Indian Navy then. It was extended and improved. It was later taken over by the Royal Navy. Early in 1944, Force “G” left India leaving the Royal Indian Navy flotillas and units in India to carry out combined training with the army at the two Combined Training Centres at Madh (Maud) and Coconada. At that time the Headquarters Establishment and Depot, HMIS Hamla, moved to Bombay area.

No. 1 Combined Training Centre was situated on Madh Island, some 3 miles south of Marve. At Marve, the Naval Camp to

accommodate the crews of the Landing Craft engaged in naval training was established. This establishment, later commissioned as HMIS Hamlawar, originally consisted of three Landing Craft Flotillas, the personnel being accommodated in tents and old huts. The Hamlawar was eventually built up to an establishment of 120 officers and 1,200 men, housed in good buildings on a really fine site. The camp was handed over to the Royal Marines when the Royal Indian Flotillas operating there were required for operations in the Arakan.

No. 2. Combined Training Centre had, meanwhile, been started at Coconada on the east coast of India, some 80 miles south of Vizagapatam. A Naval Camp was built at the mouth of Coconada Canal to accommodate the crews of, and provide maintenance facilities for, the craft engaged in army training. This establishment, commissioned as HMIS Jehangir, was originally intended to be manned by Royal Navy crews, but as these were not available, this commitment was also undertaken by the Royal Indian Navy in April 1944, with some three flotillas then unemployed. In November, when HMIS Hamlawar was handed over, it was decided that the RIN would provide crews for the Naval Camp for 2 Combined Training Centre in so far as future operational requirements permitted. Early in 1945, an officer Training Flotilla and two Ratings Flotillas were formed in HMIS Jehangir to give initial training in Landing Craft with a view to making up for operational wastage.

General

The composition of the Landing Craft by end of 1944 was as follows:–

In the Arakan:–

5 squadrons, comprising 16 flotillas, Minor Landing Crafts, 6 flotillas LCA (Landing Craft Assault), 8 flotillas LCP (Landing Craft Personnel).

One Beach Commando

Two Landing Craft Recovery Units

One Naval Bombardment Troop

One Naval Beach Signal Section

Advanced Administrative and Maintenance Parties

In India:–

The Ships’ companies of HMIS Hamla (Depot) and HMIS Jehangir, three Training Flotillas, one Beach Commando and a portion of the technical personnel of the Royal Navy Landing Craft Base at Sassoon Docks.

The total strength of the wing on 1 February 1945 was:–

Officers – 345

Ratings – 4,030 (of whom 230 JCOs and 1,779 ratings were ex-Army).

In general, the crews of the Landing Craft were composed of ex-army personnel and the technical and administrative personnel drawn from the Services. The distribution, in mid-February, was approximately as follows:–

| Officers | Ratings | |

| Operational (Arakan) | 246 | 2,320 |

| Army Training (HMIS Jahangir) | 32 | 430 |

| Naval Training and Depot Administration (HMIS Hamla) | 61 | 1,000 |

| Landing Craft Base, Sassoon Docks | 15 | 230 |

| Inter Services Exhibition, Field Gun Crews | – | 50 |

The Landing Craft Wing, as a whole, was administered from April 1944 by the Senior Officer, Landing Craft Wing (Solwing), with Headquarters in HMIS Hamla at Varsoya, near Bombay. When the greater part of the personnel of the Landing Craft Wing moved to the Arakan, the Senior Officer, Landing Craft Wing established his Advanced Headquarters in Akyab, while his Rear Headquarters remained in HMIS Hamla located in buildings vacated by HMIS Khanjar. These buildings – mainly old commandeered sanatoria – did not prove satisfactory. Hence HMIS Hamla was moved to the new quarters in Wavell Lines, Malir Camp, near Karachi.

Two flotillas engaged in radar operations on the Arakan Coast in the spring of 1944 were mentioned in the Despatches five times. Two flotillas were engaged in Lighterage for the Eastern Fleet based in Trincomalee. The Signalmen for the Landing Craft crews and for the Beach Signal Section and the Naval Bombardment troops were trained in HMIS Talwar and HMS Braganza III a Royal Naval establishment in Bombay. During 1944, four ratings from Braganza III qualified as Paratroopers. In the autumn of 1944 almost all the operational flotillas and units of the Landing Craft Wing moved to the Arakan, where they were employed in ferrying

stores and working up with “Force 64” for the assault on Akyab. During the landing at Akyab and in the subsequent operations, at Myebon and Ramree, the flotillas and units of the Royal Indian Navy Landing Craft acquitted themselves with credit. In the words of the Force Commander – ”they have done more than their stuff”.

HMIS Shivaji

Towards the end of 1940, an expanded Mechanical Training School within the dockyard area was planned as a joint measure with the object of enlarging the training capacity for 500 Naval personnel. As a result of the expansion of the dockyard during the next two years, it became necessary to find another site for the establishment outside the dockyard area. The new Mechanical Training Establishment at Lonavla (near Poona) was approved on 1 July 1943 and construction commenced during that year. The target date for completion was 31 May 1944. Due, however, to shortage of labour and transport difficulties in obtaining building materials etc., the completion date was amended and was finally fixed as 31 December 1944.

Early during 1944, as accommodation became available, the movement of boilers and machinery from Bombay was taken in hand. The first advance party left the Mechanical Training Establishment in Bombay for the new one at Lonavla on 29 November 1944. HMIS Shivaji was finally commissioned on 8 January 1945. The new establishment was designed to train a maximum number of 720 Naval personnel of various categories, and provided for an instructional staff and Ship’s Company of 50 officers and 329 ratings. It gave technical training to candidates for temporary RINVR commissions. It possessed a variety of modern mechanical and engineering appliances, steam and internal combustion engines, turbines, condensers, lathes and coppersmith’s hearths etc. A number of civilians were employed on the instructional staff, and courses covered both theory and practical work.

Other Training

Fire Fighting and Damage Control – The Admiralty regarded it as essential that all naval personnel should be trained in fire-fighting, many ships having been lost during the war through fire. Early in 1944, a school was constructed at Bombay (dockyard area) and commenced short courses for officers and ratings. It continued in operation up to the end of the war. Damage Control was first taught at HMIS Valsura and at HMIS Shivaji, whilst a series of

Ordnance Artificer P. C. Mascarenhas, DSM, RIN

general view of the parade ground of HMIS Himalaya as Vice-Admiral Godfrey declares open the new establishment.

Craft put troops ashore on one of the beaches in an assault.

soldiers visit HMIS Peshawar, a model warship at the War Services Exhibition at Peshawar

lectures was issued to ships and establishments. In 1944, a RIN officer was sent to the U.K. to undergo course in damage control, and on his return he opened the Damage Control School in Bombay. Short courses were conducted for officers and ratings and it continued to operate till the end of the war.

Anti-Submarine Tactical Training – This was established in Bombay on similar lines to the famous Western Approaches Tactical Unit at Liverpool. Officers of ships equipped with anti-submarine weapons were trained there in the latest tactics of under-water warfare. Training was so arranged that officers from escort vessels escorting convoys to Bombay might be able to attend the Tactical Training Unit in the interval before their vessels left the port along with their convoys. Thus officers were able to keep abreast of the ever-changing tactics of anti-submarine warfare.

Action Information Training – Reference has already been made to the training of officers in HMIS Chamak in radar, plotting and action information organisation etc. With the introduction into Royal Indian Navy ships of new and more complicated sets, action information centres and the like, a complete reorganisation of the radar branch was necessitated. As a result, personnel were trained separately in (a) Radar Plot: those who were responsible for manning all warning sets fitted, manning action information centres and carrying out all plotting duties in ships (b) Radar Control: those who were responsible for manning all gunnery and target indication sets and fire control.

Anti-Gas Training – Anti-gas training was first undertaken in Castle Barracks, Bombay. The INCS (Indian Naval Canteen Service) Warehouse Bombay was used as the gas chamber then. Later, anti-gas training was given in HMIS Akbar, Kolshet, Bombay to officers as well as ratings.