Chapter 14: Burma Operations (Contd.)

Simultaneously with the landing at Myebon, there was an all-out offensive down the Kaladan valley. The waterways east of the Myebon peninsula were completely blocked by Arakan Coastal Forces, whose motor launches had many exciting night encounters with the Japanese motor launches carrying goods, ammunition and oil though the chaungs to the forward troops comprising nearly five battalions. Meanwhile the Narbada and Jumna were intermittently shelling road transport and other supply targets. In a period of nine days (13 to 21 January) they fired 2,548 rounds from their four-inch guns. It was then decided to make a further landing on the edge of the Daingbon Chaung, close to the township of Kangaw. The Japanese were known to have a whole brigade defending this important staging post on their supply route, and the biggest concentration of artillery ever assembled in Burma. From these nearly 800 74-mm shells were lodged in the beachhead area during the assault. Hotly contested fighting ensued, as the Commandos and Indian troops stormed Hill 170. Between this hill and the beach, on one day alone, 340 Japanese dead were picked up from an area not much bigger than a football field. But Hill 170 was finally taken and the Japanese brigade was practically annihilated. RIN Beach Commandos did a grand job under heavy fire on this perilously small beachhead. The support of Naval guns proved a factor of prime importance. In the week following the Kangaw assault, the Narbada and Jumna fired 3,173 four-inch shells, and additional fire support was provided by other craft.

Assault

At 1700 on 21 January HMIS Narbada embarked No. 44 Commando, the Mobile Surgical Unit and 100 porters – total of nearly 700 troops. Other troops were embarked in Landing Craft Infantry (Large) and British Yard Sweepers. At 0600 next day, . the Narbada followed by these craft proceeded up the Thegyan and Mothinattaung rivers to the release position, the passage involving the crossing of a bar of 13 feet with only 6 inches under the ship. The troops were disembarked into landing craft at 1000, 500 troops being disembarked from the Narbada in 23 minutes. A

landing was effected without opposition, but shortly afterwards hostile guns proved troublesome.

At 1230 the Narbada proceeded up the Chaung to her initial bombarding position and 137 rounds were fired at various targets in support of the army. The Jumna, which had arrived back at Myebon on the 18th, also participated in the firing from an anchorage in the Myebon river.

Between 23 and 26 January, 44 bombardments of Japanese guns and defended positions and road lines of communication and focal points, were carried out, 1,584 rounds being fired. The Narbada shifted berth three times during this period, taking up positions in the Pasung Chaung and in Daingbon Chaung, as necessary. In the Pasung Chaung the ship was secured to mangroves aft.

The Narbada was relieved by the Jumna on the 26th. On the morning of the 27th the Commander-in-Chief East Indies, Admiral Sir Arthur Power, arrived at Myebon in HMS Nepal, and visited Narbada. Late on the night of the 27th the ship proceeded to Chittagong where she arrived on 28 January.

MLs at Kangaw

The motor launches played their part in the Kangaw-Myebon Chaung warfare. The 56th Flotilla had returned from refit, at Madras, and it was to these waters that it proceeded first. The motor launches arrived on the evening of 21 January, and were placed under the orders of the Naval Commander Force 64 in the Narbada. Elements of the 49th and 36th Flotillas were also present. During the actual landing at Kangaw, the landing raft were led in by ML 844, which then took up position at the northern end of the beachhead, the southern end being occupied by ML 843. In the afternoon, when the Japanese began shelling the beachhead heavily, both motor launches suffered a number of near misses and.ML 843 sustained casualties. Meanwhile all available motor launches maintained patrols at various points to prevent interference by Japanese craft, and to cut off their escape. The duties of headquarters ship were undertaken by ML 892, and excellent communications were maintained throughout.

On the night of 24-25 January, control duties were directed from ML 390. V Force Intelligence had obtained and passed on valuable information concerning the route followed by Japanese water transport, and MLs 412 and 843 were placed in Ysamwin Chaung, with MLs 413 and 849 at the south-east end of Tek Chaung, thus blocking the route. Nothing occurred during the night,

but on the 26th, MLs 412 and 843 made extensive explorations, and arranged with the local inhabitants for their own intelligence service. It was learnt that a number of hostile landing barges were bidden near Ysamwin village. During the afternoon, this area was heavily bombarded by the motor launches, but the results could not, unfortunately, be observed.

During the night of 26/27 January, MLs 413 and 849, intercepted two landing craft proceeding from north to south down Tek Chaung. The Japanese appeared to be full of confidence and were chattering in loud tones as they came down stream. The motor launches engaged them with gun fire and hits were registered, but owing to smoke it was not possible to see whether they had been sunk. As, however, no trace of the landing craft was subsequently found, it was probable that they were sunk.

On the morning of 27 January orders were received for the 56th ML Flotilla to proceed to Kyaukpyu and join the 55th Motor Launch Flotilla for the Ramree blockade.

Americans Take a Share

During the second half of January, the motor launches had been busy again. On the 18th, MLs 438 and 441 embarked a party of the American Maritime Unit, and sailed with the intention of landing on Thalunew point.

The unit proceeded south round Baronga Point, and past Satellite Island, then through the centre of the channel between Sep-pings Peak and Achargwaine Island. This area was studded with rocks, and at a later date was found to be heavily mined. The landing position was approached from west, and at 2146 just as the motor launches were preparing to disembark the American party, a vivid flash from the shore was seen, and a heavy calibre shell exploded near ML 438. This was followed by four or five further salvoes and one star shell, all of which were good for line, but over by some 1,000 yards (except the star shell, which fortunately fell short). The motor launches withdrew with all speed followed by further salvoes which passed harmlessly overhead. As no suitable alternative landing position was available, the operation was abandoned, and the force returned to Akyab.

Assault on Kyaukpyu (Ramree Island)

The assault on Kyaukpyu was timed to take place at 0930 on 21 January at the same time as the Narbada and the Jumna with the Garhwal Rifles embarked were attacking Kangaw. A week

previously on 14 January Lt. Cdr T. H. L. Macdonald, DSC, RINVR in ML 440 with ML 447 in company embarked a Special Boat Section under the command of Major Livingstone, and proceeded from Akyab south to Katherine Bluff, which bounds Kyaukpyu harbour on the northern side. The party were landed successfully, and for four successive nights the two MLs returned to Kyaukpyu to wait at a predetermined rendezvous for their return. On the 17th night, Major Livingstone returned safely, having carried out a complete reconnaissance of Kyaukpyu inner harbour.

On the evening of the 20th, MLs 440, 438, 476, 477, 474 and 441 proceeded to the convoy assembly position outside Akyab harbour off Savage Island. On leaving the harbour, considerable enthusiasm was evidenced when the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, appeared silhouetted against the sunset. The convoy was a formidable sight; landing craft of every description had to be shepherded into position, and the convoy finally moved off after dark. Six landing Craft Assault at a time were towed in two lines by BYMS (British Yard Mine Sweeper) and one Landing Craft Personnel was attached to each Landing Craft Mechanized. Considerable difficulty was experienced in keeping the landing craft on the right course, and the motor launches spent the whole night chasing lost ships and stragglers. At dawn, however, the convoy was in reasonable shape, having been joined during the night by a number of troop transports, the cruiser HMS Phoebe, the destroyers HM Ships Pathfinder and Rapid, HMI Sloop Kistna and HMI Ships Konkan and Kathiawar.

By 0830 two columns of assault craft had formed up. The starboard column was led by ML 440 with MLs 474 and 476 in support, and the port column by ML 438, supported by 477 and 441.

A tremendous bombardment, considered to be the most ambitious assault, ensued as the force steamed towards the selected beachhead between Georgina point and Dalhousie point, 15” shells from the Queen Elizabeth screamed overhead, supported by the lesser armament of the Phoebe, the Destroyers, and of the Kistna. The Kistna discharged 857 4-inch shells between breakfast-time and midday. At 0915 with the selected beach still a mile distant, heavy bombers attacked the Japanese defences, followed by fighters who strafed Japanese trenches and beach obstructions.

At 0930, the motor launches in each column deployed to starboard and port, ready to engage any targets which might be observed, while the 64 landing craft roared on to the beaches; troops

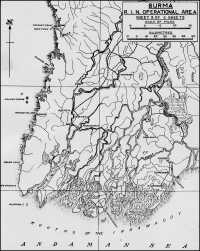

Burma: RIN Operational Area

deployed in every direction, the Lincolns first, and then the men of a Punjab Battalion. After the beaches had been secured, MLs 438, 441 and 447 carried out a sweep of the inner harbour while MLs 440, 474 and 476 anchored in company with ML 891 off the beachhead, awaiting further orders.

At 1100 a Landing Craft Assault approaching the beach and carrying 32 men of a Battery Headquarters, suddenly blew up in the vicinity of the motor launches and disappeared in clouds of debris. This was the first indication that the harbour was mined. The motor launches immediately proceeded to pick up survivors, but only seven were found, and later transferred them to HMS Rapid.

At this stage, MLs 474, 476 and 891 were lying alongside the Rapid. ML 891 came out astern, and just as she cleared the destroyer, a great explosion took place, and 891 disappeared in a vivid cloud of flaming smoke. MLs 474, 476 and 477 went at once to her assistance but owing to the flames could not get near her sufficiently. A number of survivors were seen clinging to the keel of the ML and these men were taken off by a motor-boat from the Rapid. Fourteen out of the crew of seventeen were picked up unhurt.

After the loss of these two craft, the force withdrew till the area had been swept, and the motor launches anchored near F.T. 14 in the outer harbour.

The build-up, after the harbour had been cleared of mines, went on steadily, and Landing Craft Mechanized worked non-stop to unload transport and stores from the big transports. During the night following the assault, a Japanese plane produced a fireworks display from the ships, but no bombs were dropped. HMIS Kistna and other warships were still at Kyaukpyu, responding to periodic calls by the army for the bombardment of specific positions ashore.

After three days, all RIN Landing Craft moved into a creek behind Kyaukpyu harbour where a landing craft base had been established. It was not very comfortable, but it enabled weary crews to have a break ashore, and repairs to be done.

After the harbour had been completely occupied, night antisubmarine patrols were carried out by the Kistna and the Flamingo to seaward of the merchant shipping.

Cheduba Island Assault and Ramree Island Blockade

26 January 1945 was fixed as D-Day and 0845 as H-Hour. The Japanese had been completely misled by the Allies regarding the assault on Ramree island. By a series of preliminary

bombardments and beach reconnaissance, the Japanese had been led into thinking that the Allies would probably land on the west coast. There the Japanese had concentrated their defences, relying on a minefield to deter the Allies from making the assault closer to Kyaukpyu. This minefield was cleared by the Royal Indian Navy minesweepers. Our troops pushed on down the island’s west coast supported by naval bombardment.

General Christison was anxious to occupy Cheduba island at an early date, but did not wish to commit his troops to another assault when they were fully engaged on Ramree Island. Royal Marines from the battleship Queen Elizabeth and from cruisers of the East Indies Fleet were landed near Scarle Point, on the northern shore of Cheduba Island, five days after the Kyaukpyu assault.

The landing was preceded by a cruiser-and-destroyer bombardment, ships taking part included the cruisers Newcastle, Nigeria and the destroyers Nepal (wearing the flag of Admiral Power), Norman, Rapid, Pathfinder and Paladin. The landing craft were escorted to the assault beach by motor launches of the Burma Navy. Ten minutes before the first wave touched down, Hellcats from the escort Carrier Ameer strafed the beach. The landing was accomplished without difficulty and the Royal Marines pressed on to occupy the whole island, whose area was roughly 150 square miles. At the end of January they were relieved by an Indian battalion.

Many Royal Indian Navy Landing Craft Assault took part in the capture of Cheduba Island and some Landing Craft Mechanized landed at points down the west coast of the island. Lieut. S. J. Brander RINVR and two LCMs captured Sagu island in a private expedition. When a day or two later, a carefully planned small-scale assault was carried out, the assault troops were somewhat chagrined to find Lt. Brander and his men firmly in occupation and at that moment searching the beach for a suitable camping site.

Blockade of Ramree

As the army pushed south on Ramree Island, the Japanese defenders were slowly and relentlessly driven into the mangroves, and the blockade of the island began. Destroyers, motor launches and landing craft assault, carrying Gurkha Bren-gunners, patrolled the Thanzit river. They lay under cover of mangrove clusters at night, and caught the escaping Japanese by listening to their movements. Their watchfulness was rewarded on many occasions by the arrival of Japanese soldiers floating on logs, and parties trying to find their way over swampy ground on foot. On one occasion, a

large party was caught scrambling out on a raft they had just built. The sounds of tree felling reached a Landing Graft Assault, which brought the guns of a ML on to the target, and almost every man of a party of 50 Japanese was killed. The first motor launch patrol in the Thanzit river was carried out on the night of 24 January by Motor Launches 476, and 474. The river was in the main uncharted, but the patrol penetrated some 27 miles upstream. No opposition was encountered until opposite Kalebon Bluff, at which point the channel ran within 600 yards of the shore. Here the Japanese had established a strong point with a 25-pounder, several mortars and machine guns. A lively engagement took place, as the motor launches raced past at high speed. No movement, however, appeared to be taking place on the river, and the unit withdrew at dawn without difficulty.

Deception

On the 24th also, MLs 440 and 441, embarked a deception party to carry out an operation in Yinbauk Chaung, half-way down the west coast of the island, where the Japanese were putting up strong resistance. The deception party was to lay booby traps and fireworks behind the Japanese lines to cause consternation after the landing party had withdrawn. A Landing Craft Personnel was towed by Motor Launch 441 to carry out the landing.

By midnight the unit was within five miles of Rocky Point, where HMS Flamingo was anchored for bombardment duty. When some two miles off Rocky Point, the boats were heavily engaged by a Japanese 75-mm gun. ML 440 plotted the position of this battery, and transmitted it to Flamingo. ML 440 thereafter steamed towards Rocky Point again, and was successful in enticing the battery into opening fire once more. The Flamingo thereupon opened up, and 40 rounds of 4-inch shells completely silenced the Japanese gun, which was later captured in a damaged condition.

As surprise had then been lost, it was decided that no landing should be made. Thereafter the MLs re-formed, and returned to Kyaukpyu.

The following night, MLs 476 and 474 carried out the Thanzit patrol, and another exchange took place with the Japanese on Kalebon Bluff. On the 26th, MLs 440 and 441 carried out this patrol, and penetrated as far as 30 miles up the river. ML 440 had the misfortune to hit a submerged rock, damaging both propellers, and was towed* back to base at dawn by ML 441.

Assisting in this blockade were the Kistna and the Flamingo, ready to tackle targets out of range of the motor launches. On the

26th, the Kistna was at anchor in Ramree Wah Creek, engaging targets in support of the army, and on the 28th was employed on similar duties off Thames Point. At this period, the retreating Japanese forces, in spite of the prolonged operations by sloops and motor launches to cut their line of retreat in the Kangaw -Myebon area, were still managing to infiltrate round the hills behind Kangaw down to Combermere Bay, and then by devious inland waterways to reach Letpan. There was a danger that a strong force might be able by this means to occupy the mainland opposite Ramree, and make the water in between untenable. A patrol in Combermere Bay was therefore instituted, and on the 29th HMIS Kistna with ML 413 and ML 416 were in this area. The Kistna carried out a bombardment of Japanese battery positions ashore on Thalumaw Island from an anchorage off Maung Wane Island with ML 413 spotting, and other targets were engaged as the vessels left the bay.

Blockade Tightened

Late in January it was decided that the Ramree blockade should be intensified, and, as already related, the 56th ML Flotilla proceeded on the 27th to Kyaukpyu to join the 55th Flotilla on this job. The army had been pressing the Japanese south and east down Ramree Island; by 8 February, Ramree town was captured and the main remnants of the Japanese troops were squeezed into that part of the Island lying to the east of a line Ramree-Town-Sane, faced with the alternative of fighting or attempting to escape through the chaungs of mangrove swamps to the east. They chose the latter. To cut them off, it was decided to block all chaung exits from Taraung Chaung to the Paikseik Taungmaw river in the east and exits into the Mingaug Chaung and Paikseik Taungmaw river in the north-east.

The Ramree operations were Chaung warfare at its best. It is perhaps difficult to visualise this type of naval warfare. The rivers and chaungs were for the most part completely uncharted, and to reach some of the positions within range of shore targets, both in the Ramree and in the Kangaw-Myebon and Ruywa areas, sloops, Z-craft, and motor launches had to navigate up to 30 miles of these uncharted waters. The chaungs were creeks varying from 1,500 yards to 150 feet wide, generally bounded by high mangrove trees up to 50 feet in height. Firm banks and villages were an exception. The creeks were tortuous and often great difficulty was experienced in turning the sloops at some of the hairpin bends. The depth varied from 7 feet to 80 feet at low water, and usually

the narrower the chaung, the greater the depth. The creeks were tidal, the range being about 9 feet. They were studded with numerous shoals and pinnacle rocks which presented perpetual hazards. The Admiralty later described these chaung operations in an intelligence review as “unprecedented in the annals of Naval History”, while Admiral Sir A. J. Power, KCB, CB, RN, then Commander-in-Chief Eastern Fleet, wrote of them:– “The Myebon, Kangaw and Ruywa operations afforded splendid opportunities for enterprise, resource, impromptu operations and close-range fighting. On each occasion the enemy was caught on the wrong foot and defeated. Sloops, destroyers, minesweepers, motor launches and landing craft manned by Royal Navy and Royal Indian Navy personnel took full advantage of the perfect weather for fighting and the unique opportunities for displaying good seamanship. They landed and supported our troops without any fuss, navigated uncharted waters with skill, and although in face of considerable hardships, especially in the minor landing craft, they never flagged”.

Like the Thames

This unusual warfare produced a number of interesting incidents. The army inclined to the view that all parts of their maps which were coloured blue were navigable by H.M. Ships, and this was the subject of a somewhat bitter report from the Senior Officer, 56th ML Flotilla, who had been ordered to proceed up a tortuous chaung in the Ramree area for a conference with the local army commander. He referred to the chaung as follows:–-”This waterway is considered more suitable for amphibious vehicles than for MLs”. One Boat Officer in the Landing Craft Wing was surprised to find an Army Officer saying that the Daingbon Chaung was not unlike the Thames in some respects.

Dredgers’ Union

Most of the ships ran aground at some period of the operations. On one such occasion, HMIS Narbada, observing a motor launch firmly embedded in the mud, enquired facetiously, “Are you a dredger?”. The motor launch did not reply, but when a few days later the Narbada herself ran aground in the same waters, it was this MLs turn to pass by and to signal “Welcome to the Dredgers’ Union.”

Sagu Kyun Island

As it is not possible to describe all the incidents during the blockade only the important ones are recounted. As part of the blockade MLs 476 and 474 sailed with a combined landing force to Sagu Kyun Island. Capt E. T. Cooper RN was embarked in ML

476 as Senior Officer, Assault Group. Sagu Kyun was reached at 1000 on the 13th, and the landing was unopposed. Japanese guns had been reported, and H.M. destroyers Norman and Raider bombarded the position. At 2100 MLs 476 and 474 proceeded through Ramree gates to patrol the inner harbour. Nothing, however, was sighted during the night, and the Force withdrew at dawn to support a further landing on the southern tip of Ramree island. This landing was also accomplished without incident, and at dusk on 31 January the destroyers were withdrawn, together with most of the landing craft, leaving MLs 476 and 474 to carry out a further night patrol of Ramree harbour.

At 1820 just as the destroyers were disappearing over the horizon, the Japanese engaged the MLs with heavy guns from the shore. The Force immediately got under way, at the same time observing near misses on the few landing craft remaining.

Japanese fire ceased at 1905 and it was decided that to enter Ramree harbour through the narrows in the face of heavy gunfire was an undue hazard and the harbour was consequently entered by the eastern channel. Fire was again observed apparently directed at the MLs at 2255 but no fall of shot was observed, and the patrol continued anchoring by Ponca Island for the night. As nothing was seen during the hours of darkness the MLs withdrew at dawn to return to Kyaukpyu.

Other patrols were carried out through Combermere Bay as far as An Chaung, first by MLs 438 and 477, and subsequently by MLs 413 and 843.

The Illuminations

All boats of the 55th and 56th ML Flotillas were kept continuously on patrol, and were supported by H.M. Destroyers Pathfinder and Eskimo with HMS Flamingo and sloops of the Royal Indian Navy. Landing Craft Assault, Landing Craft Mechanized and British Yard Mine Sweepers also took an active part, and it was a usual sight to see these vessels anchored at intervals of some three cables off from the Thanzit river to a point opposite the eastern end of Ramree Chaung. His Majesty’s destroyers did notable service, especially the Pathfinder, who penetrated as far as the Paikseik Taungmaw river where she was damaged by bombing.

After the first fortnight a lull indicated that the Japanese had escaped, or had died in the mangrove swamps. At the time orders were received that every form of illumination should be used to light up the chaung at night. The results were fantastic. Lighting sets were removed from jeeps and supplied to motor launches and

landing craft, and destroyers’ searchlights played constantly through the night hours.

477 Hit

On 7 February, ML 477 was anchored 50 yards from the east bank of the Paikseik Taungmaw river. Look-outs reported distant voices, but nothing was sighted until at 1405 a gun opened fire on the motor launch from the western bank from a range of approximately a thousand yards. No flash could be observed, and although engines were started immediately and anchor slipped, eight direct hits were -sustained. Fortunately the Japanese were using armour-piercing 37-mm, which went right through the ship. At this moment the gun was located on the only piece of high land and was immediately engaged. ML 441 came in to assist, followed by ML 319, and the hostile gun was successfully quelled, ML 477 being able to return to base under her own power.

The Sloops Again

We may now turn to the story of the sloops, and to state briefly the position on land. The assault on the Kangaw area by the 3rd Commando Brigade on 21 January under the support of the Narbada and Jumna has already been described. The 51st Brigade was subsequently landed. The 74th Brigade advancing from Myebon continued its attack on the western side of the Kyaukgnmaw river, and later carried out raids on the eastern bank to the north of Kangaw. The 82nd West African Division was pressing southward towards Kangaw from the direction of Hpontha. The Japanese fought hard in the Kangaw area carrying out repeated counterattacks. They threw into the battle the largest concentration of artillery yet met by our troops in Burma, but by 3 February it was evident that they were commencing a general withdrawal southwards, and it was decided to use the sloops to bombard targets on their line of retreat.

The object of sloops’ next operation, therefore, was the harassment of the Japanese line of communications between Kyweguseik and Tamandu and especially the ferry crossing on the Dalet Chaung.

The operation began on 5 February, and the bombarding force consisted of four sloops and two Z-craft – HMIS Narbada, HMIS Kistna, HMIS Jumna, HMS Flamingo, the Z-craft Enterprise, and the Z-craft Fighter. The Jumna and the Flamingo, were not present at the start of the operation, and joined the Force on the 6 and 12 February respectively, while the Kistna left on the 10th. The four

sloops each carried six 4” guns, while the Z-craft were armed with four 25-pounders.

Fire Plan

The plan was for the Royal Air Force to carry out the maximum possible harassment of the Japanese line of communications by day and the naval forces to do likewise by night. The Royal Air Force effort consisted of bombing, strafing, and offensive reconnaissances. From 1200 to 1400 daily there was no RAF activity so that the sloops and Z-craft might register with air observation post on new targets and re-register on old ones. The whole operation was controlled from the Narbada.

The Narbada and Kistna anchored at their bombarding positions on 5 February and commenced to engage a series of targets. The principal targets were in the area of Tamandu, where the Japanese were believed to have their garrison, the ferry crossing at map reference 8916, and the area between Kokkomaw and Thekanhtaung. Later, when the Japanese ceased using the ferries, fire was. shifted to the crossing point between Swichaung and Kazaukaing. Other targets were the main roads between Tamandu, Shaukchon and Kolan, the road between Tamandu, Tangyo, Ruywa and Kyweguseik and also the Japanese Inland Water Transport base at Nyaungkhctkan. Counter-battery work was carried out against Japanese 75-mm batteries at Thila, Nyaungkhetkan Pagoda, and on hill feature 582 east of Tamandu. All these guns were very carefully concealed in deep-roofed bunkers in thickly wooded hill country, and observation was very difficult. These were treated as secondary targets, and were only engaged when the guns proved troublesome, on which occasions they were effectively silenced, but not, so far as was known, destroyed.

Several engagements took place between sloops and batteries during the operations. On 12 February the Jumna and the Flamingo were engaged by guns at Thila. As the gun positions could not be detected, they were compelled to retire temporarily. The guns were afterwards silenced with the aid of air observation.

Kantaunggyi Village

On 15 February as the Narbada was leaving Thayettaung Creek for a new operation, information was received from the headman of Kantaunggyi of the arrival of 50 Japanese soldiers in his village. The village could not be engaged from the creek, hence the Narbada was taken to a position in the Kanbyin river from where a clear line of fire was obtained. The Japanese batteries on point 962, east of

Tamandu, opened fire on Landing Graft Support (Medium) 6, carrying the forward observer, as she came within 1,000 yards, but she pressed on and obtained shelter behind a mangrove island. The Japanese then shifted fire to the Narbada, who retired just out of range. This caused some slight delay, but the shoot on Kantaunggyi was successfully accomplished with the aid of the headman of the village in the LCS(M), who pointed out the Japanese camp. After dealing with this position, the Narbada engaged the troublesome batteries whose position, had for the first time been accurately observed from the flash of their guns.

A total of 3,300 rounds was fired by the naval ships between 5 and 15 February, in addition to about 2,000 rounds fired by the 25-pounders in the Z-craft. The ships were involved in continuous operations for eleven days and were operating throughout the period within a few thousand yards (sometimes much less) of strongly held Japanese positions and batteries, in waters in which their craft were known to be operating, and which lent themselves to unorthodox form of attacks such as underwater attacks and assaults from the banks with mortars and grenades.

Results

The results of the bombardment were difficult to assess, but from information provided by the local population, it appeared that the Japanese forces retreating from Kangaw and Kyweguseik were held up on the northern bank of t he Dalet Chaung for many days. Apparently the Japanese were led to believe that an assault would develop in the Dalet Chaung area. In actual fact t he next attack was made well to the south in the Ruywa area and was unopposed; the tying of the Japanese forces to the Tamandu area could only be attributed to the bombardment. The evacuation of the villages by the local inhabitants, consequent on the bombardment, depleted Japanese supply of food, and drove them to desperate measures to obtain it. They had been relying previously on rice stocks held by the villagers during the retreat.

During the operations frequent survey expeditions were carried out by MLs with echo sounders, and by the survey yacht Nguya.

Ruywa Assault

D-Day was fixed for 16 February. 1030 was to be H-Hour.

With the mopping-up operations in the Myebon-Kangaw area being practically complete, the next step was to harass the Japanese withdrawal southward towards Dalet (headquarters of the Japanese 54th Division), Tamandu and An. Accordingly a naval

bombardment force was assembled on the flank of the their line of retreat. This force included the Narbada, the Kistna, the Jumna, and the Flamingo, all armed with six 4-inch guns. To reach their bombardment positions the ships had to navigate 30 miles of uncharted chaungs.

The bombardment went on day and night from 5 February to 15 February. Most of the country was densely wooded, with precipitous mountains, cut by deep valleys. The remainder was mostly mangrove swamp. The Japanese were most skilful in concealing their guns and in moving them from place to place. But forward observation officers kept the ships informed of the changing location of their various targets.

Ruywa, 20 miles south of Dalet, was once again the area of operations for the landing craft of the Royal Indian Navy. This young branch of the service landed the 25th Indian Division troops dead on schedule at Ruywa and became also their main supply link. The Naval Assault Force assembled in full daylight inside a chaung, a considerable distance from the open sea. Led by Arakan Coastal Force motor launches, the minor landing craft-mainly Royal Indian Navy – proceeded further upstream and were diverted unescorted into a smaller chaung continuing for another hour up a narrow winding channel before unleashing the first wave of troops into thick jungle. By the time the third wave had landed, the jungle had been cleared. This technique of amphibious landings up small creeks amidst thick jungle was far removed from the traditional conception of sand beaches and heavy naval units lying just off-shore. Nor was this the only hazard our men were overcoming in those landings. At Ruywa the shallowness of the creeks was an additional problem and rendered the beach usable only at certain stages of the tide. Yet, the Naval Assault Force was able to fulfil all its assignments, and by the end of the first day, the 25th Indian Division troops had reached their initial objectives exactly as planned. The rapid succession of landings on the Arakan coast surprised the Japanese forces and at Ruywa once more tactical surprise was achieved.

On 16 February the assault operation was carried out. The initial object was to land the 53rd Brigade to secure a beachhead through which the 2nd West African Brigade and the 74th Indian Infantry Brigade would be able to advance on An and Tamandu, respectively. The bombarding force was to support the landing of the 53rd Indian Infantry Brigade, and later, after the initial assault, to support the operations of the two other Brigades, and also the

advance by the 5th Nigerian Rifles from Kyweguseik Ngamankai Ywat Hit.

The Jumna left the bombardment force on 21 January and was relieved by the Cauvery on the 24th. Prior to the operation, a survey was conducted in ML 856 of the Ngandaung, Taungseing, and Kyaukpadaung rivers, and the various chaungs leading off from, and connecting, these rivers.

The pre-arranged task consisted of a fire plan on the Thangyo-Donkekan-Ruywa area, in which the three sloops took part in collaboration with army guns which had been landed on an island nearby. The targets chosen were the likely concentration areas of Japanese forces, and the fire plan was designed to prevent their movements towards the beach area.

The actual landing was entirely unopposed and was carried out most successfully. After the assault, the principal tasks were counter-battery work whenever the Japanese opened fire on our troops or craft, fire plans in support of military attacks, fire on hostile defended positions on call by forward bombardment observers, and night harassing fire on Japanese guns and positions which had been registered by air observation by day. Control of the bombardment was in the hands of the Narbada with the Senior Bombardment Liaison Officer embarked. Some of the targets engaged were at a considerable height, and out of sight beyond intermediate crests. Bombardment observers found great difficulty in finding good observation posts.

Quick Work

On 21 February an air observer spotted a Japanese gun, and called for fire. Fire was opened in 60 seconds on this target which had not previously been registered, and the shoot was completed in 5½ minutes in the course of which 26 of the 32 rounds fired fell in the target area. The gun was not heard of again. This was possible due to the RIN sloops maintaining direct radio telephonic communications with the observation planes which were operating from an air strip built the night before D-Day. This direct air-sea co-operation was made even closer by the fact that the senior ship of the squadron commanded by Captain M.H. St. L. Nott, OBE, RIN, was moored in a narrow chaung alongside the air strip.

A Dangerous Shoot

On another occasion the 3rd Gold Coast Regiment called for fire on a defended position on a hill 1,262 feet high at a range of 1,500 yards. For this bombardment our forward troops were

stationed a thousand yards short of the position, a thousand yards beyond it and a thousand yards to the right of it in dense bamboo jungle. In spite of their close proximity to the target, the shoot was successfully carried out, and the Japanese were dislodged from their position, enabling the Africans to advance without opposition at this key point.

On the night of 19 February Capt. G. Robins, R.A. kept a watch on the road between Tamandu and Thangyo from a Landing Craft Support (Mechanized) lying close to the bank within a few yards of hostile territory. At about 0100 he heard transport moving along the road, several points on which had previously been registered. He called for fire on one of these and the first shell arrived at the precise moment required. The result was at least one ditched lorry, and much shouting and confusion. At a later date a Japanese Divisional Headquarters, and centre ‘ of communications in the Letmauk-Kolan area were engaged with the aid of air spotting at a range of 18,600 yards.

Narbada Damaged

On 22 February at 1830, fire was suddenly opened by Japanese 75-mm guns on the Narbada at anchor in the Setkhaw River. The ship was straddled with the fifth shot, and although by that time under way, was hit aft by the sixth round. The shell exploded in the depth charge stowage on the starboard quarter, splitting two depth charges completely in two. Fortunately they did not explode, a splendid testimony to the stable qualities of amatol. The steering gear also broke down temporarily due to a near miss. The only casualty was the coxswain of a D-tug lying alongside.

The Narbada immediately opened fire on the most likely Japanese guns which had been previously registered. It was, however, impossible to be certain which gun was firing, as no observation was available. The Japanese fire was extremely quick and accurate, and they secured several more straddles but no hits.

The Forward Observer Bombardment’s Capture

On 4 March, the 74th Indian Infantry Brigade put in an attack from Thangyo which was intended to carry them to Tamandu. At 0945 the Narbada carried out a heavy bombardment of the Tamandu area, which the Forward Observer Bombardment observed from a distance of 500 yards. He then reported that in. his opinion the village was deserted and was given permission to investigate. This was done, and he took with him a Midshipman, and four

Ratings of the Narbada. The party carried out a reconnaissance 200 yards inland when they were stopped by mines and Panzi stakes.

The 74th Indian Infantry Brigade meanwhile had been held up by the Japanese some three miles further south. The Brigadier 74th Indian Infantry Brigade, asked that the Landing Craft Assault to make a small arms demonstration north of Tamandu to make the Japanese think a party was being landed north of them. This was done, and was effective. It was entirely due to the reconnaissance carried out by the Forward Observer Bombardment and his party that the decision was made to press on to Tamandu that afternoon. At 1730, six hours after the initial landing by the Forward Observer Bombardment and his party, the leading elements of the 74th Brigade arrived, and the village was turned over to them. It was probably the first time in history that a Forward Observer Bombardment had “captured” a village.

The waters in which the sloops were operating were equally difficult to those in the Myebon and Ramree areas, and special noteworthy feats of navigation were the Flamingo’s passage up the Hinkhonbauk river, and the Cauvery’s night passage from the Kaibainggyun river to the Zigyun river.

Cauvery and Kistna

HMIS Cauvery during these days had been busy supporting the army, and between 1 and 6 February she maintained intermittent harassing fire on Japanese land positions and periodic registration shoots with aircraft spotting. HMIS Kistna had a gun duel with a 75-mm gun on Naungkhetkhan Island.

Landing of Guns

Mention was made earlier of the landing of army guns on an island in the Ruywa area. This job was carried out by a Royal Indian Navy Landing Craft Flotilla, assisted by Royal Marines, and two batteries of 25-pounders were put ashore. The landing point selected was nearly 2\ miles up a circuitous chaung and was within a mile of a Japanese gun position. The guns were landed from ten craft in the space of six hours on a beachhead permitting only two craft at one time. Five hours later the same flotilla was standing by to take in the assault troops to the main beach at Ruywa.

The Supply Line

In a tent whose walls, tables and chairs were merely camouflaged tins of hard rations, the Paymaster supplied the Landing Craft

Wing in Ruywa. He followed the southward advance of the forward landing craft base from Myebon and set up office in the Ruywa area, five days after the initial landing there. Japanese artillery was shelling the clearing in which this front-line store was set up.

On to Taungup – The Letpan Assault

Having completed the mopping-up of Ramree Island, the 26th Indian Division then turned its attention to the mainland, for the push to Taungup to bring the Arakan campaign to a triumphant close. Six landing points were selected on the Ma-I Chaung, near the Letpan Ferry, 30 miles up the road from Taungup. The landings which were made with many minor and major landing craft, involved a 40-mile passage through twisting rivers and chaungs. The landing craft were supported by motor launches, minesweepers, the British destroyers Roebuck and Eskimo and RIN sloops Jumna and Cauvery. The destroyer Nubian joined later, helping to provide fire support for the southward advance. The landing was unopposed, and although opposition grew, Taungup was entered on 4 April.

On 12 March, the Narbada was relieved by the Jumna and on that day the Jumna and Cauvery embarked some 400 troops of an assault force and proceeded to the Kaleindaung river to take part in operation “TURRET”. The position on the coast there was that they were established fairly firmly in the Arakan, on the mainland as far south as Ruywa, and on the islands of Ramree and Cheduba. Inland, the 25th Indian Division was advancing south along the axis of the road An-Hinywat-Lamu-Taungup, and the main problem was to prevent the main body of the Japanese forces from crossing the Ma-I Chaung and linking up with the garrison at Taungup, which from all reports was being rapidly and substantially reinforced at that time.

It was essential, if a stalemate was to be avoided, that Taungup be captured before the break of the monsoon. Its capture was important from a military point of view and also from a propaganda one. Taungup meant slightly more to most people outside Burma than names like Myebon, Kangaw, Ruywa, and Letpan, and it meant a great deal more to the Arakanese and the Burmans.

An operation was therefore planned to take place on 13 March 1945, to land the 4th Brigade Group in the vicinity of Pyinwan to establish a beachhead on both the banks of Ma-I Chaung. Forces taking part in the operation were Naval Force ‘W one’ (a composite assault force composed of elements from both the Royal

Navy and the Royal Indian Navy, with bombarding ships,) the 4th Indian Infantry Brigade, 6 squadrons of P 47s, 2 squadrons of Hurricanes, and a half squadron of Tac R Hurricanes.

Subsidiary Beaches

Before the main landing, however, two subsidiary beaches had to be secured. One, on the Singin Taung was for the landing of 25-pounders and 5.5” guns to deal with some Japanese 75-mm positions which had been reported opposite this beach. This position was to be assaulted at 2130 on 12 March by two companies of the 1st Battalion 18th Royal Garhwal Rifles, and the beach was to close down as soon as the main beachhead at Pyinwan had been secured.

The second subsidiary beach was to be established at the head of Chetpauk Chaung, also at 2130 on 12 March. The assaulting troops in this case were one company from the 2nd Battalion, 13th Frontier Force Rifles and one platoon from the Royal Garhwal Rifles. The purpose of the landing was to push through and secure point 1121 on the hill known as Ziban Taung, which directly overlooked main assault beach and was reported to house some Japanese guns. It was essential to secure this feature before dawn to provide a suitable observation post for the pre-assault naval and air bombardment on any Japanese positions in the Pyinwan and Letpan areas.

The main beachhead was to be established at Pyinwan, the assault going in at 0930 on 13 March. The landing was to be made by the 2nd Battalion Green Howards with two machine gun companies of the 12 th Frontier Force Rifles Regiment in support. The original landing was to take place on the north bank, and a second bridge-head was to be secured later on the south bank.

Sindin Taung

The operation was mounted from Kyaukpyu and all embarkation of assault troops and loading of stores was completed by 1800 on the 12th. The assault force had been split up into six convoys, lour Jailing on the 12th into six convoys, four sailing on the 12th to reach lowering position at various times before dawn on the 13th, and two sailing between 0001 and 0030 on the 13th.

Shortly after dawn Royal Indian Navy sloops dropped anchor at their rendezvous and waited. Throughout the night landings were carried out around the Letpan area. One sloop blasted suspected positions. Ant-like streams of landing craft moved in and out of the Chaungs feeding the tributary attacks, while the main beach

under cover of airstrike, tanks were unloaded within an hour of the first wave going ashore. The RIN Beach Commando with its Beachmaster regulated what might easily have become a major traffic jam. Explosives were used to dynamite fresh beaching strips, while the broad perimeter of paddy field flanked with trees was filling with transport and equipment.

The first convoy reached the lowering position at 2000 on the 12th, and the troops were embarked in the Landing Craft Assault immediately and went off to secure the beachhead on the Sindin Taung. The landing was made at high water with little trouble and no opposition, and by 0500 on the 13th, the beachhead was firmly established. Unfortunately, after the tide began to ebb, it was found that nothing could be landed on the beach for two hours on either side of high water, because the bank below high water mark was a mass of mud and nothing could pass through, even though “sandwiches” with a special thick bamboo soling had been specially made for this emergency. The guns were eventually landed during the next day and the beach finally closed down on the 14th.

“Stick-in-the-Mud”

The second convoy carrying troops to secure the beach-head at the top of Chetpauk Chaung arrived safely its release position. This beach was a somewhat different proposition to the one at Sindin Taung in that it was right up Chetpauk Chaung, which at the best of times was about 15 to 20 yards broad with mangrove banks. The beach selected was a small clearance in the mangrove about 50 yards long, with good firm paddy field behind it. It was overlooked, immediately on its left, by a small feature which was reported to be occupied by the Japanese. Owing to the darkness the first wave overshot the beach, and landed the troops into thick mangrove. The swamp extended to a depth of about 20 yards and it took the troops about twenty minutes to get across it.

The troops did their job and by early next morning had secured point 1121. The landing also was completely unopposed in spite of reports that the Japanese were in fair strength in the area. The original beach was established next morning and was worked till 0800 on the 14th when it closed down.

The remaining two assault convoys dropped anchor for the main assault at 0700 on 13 March. By this time the bombarding ships, the Cauvery and the Jumna, and the destroyers Reobuck and Eskimo, were in position and commenced their bombardment. Air support

was forthcoming from Thunderbolts of the U.S. Army Air Force, and inshore support was given by MLs 439, 477, 390 and 417. The assault wave left the ship at 0730 and the whole operation was carried through without opposition. During the first day the whole of the Brigade Group, with 200 tons of stores and 50 vehicles, was landed, and subsequently a further hundred tons of stores were taken off from a stores ship lying about 10 miles out and 27 vehicles were brought over from Kyaukpyu.

Since there was no opposition and things were going well a new beach-head was established half-a-mile further up the Ma-I Chaung, astride the Hinywat–Lemu road. This new beach gradually became the main one, as it was on the right side of the chaung, and all other beaches were closed down. The operation had been completely successful, and from this time it was a matter of jumping from one chaung to another, always going south, until the capture of Taungup on 15 April, when the ultimate object of the operation was achieved.

Coastal Forces Depart

The Letpan combined operations were the last in which the Fairmile Flotillas took part. The 55th ML Flotilla returned to Chittagong three days later, after six month’s continuous operation in Burmese waters, during which time some 340 single boat sorties were carried out.

The 56th ML Flotilla remained behind and carried out one further operation. On 30 March, MLs 412, 413, 417 and 844 together with four boats of the 36th ML. Flotilla, made rendezvous with the Roebuck and the Eskimo in the vicinity of Gwa. The motor launches proceeded into Gwa Bay in line ahead, while the destroyers opened fire with starshell, and 4.7” guns. The motor launches took up the bombardment from close inshore. No results were ascertained, and there were no signs whatsoever of Japanese activity. At midnight on 31 March the Force returned to Akyab, and two days later the 56th ML Flotilla was ordered to return to Vizagapatam for refit.

Last Harbour Defence Motor Launches

The only coastal forces then remaining in the Arakan were a few boats of the 121st HDML Flotilla which were based at Chittagong and operated in the forward areas on various duties when required. In March, HDML 1120 was at Teknaaf helping to salvage a workshop lorry which had sunk while being loaded, and later in the month HDML 1115 helped in the salvage of a

crashed liberator at Cox’s Bazar. The last three boats (1115, 1117 & 1120) returned to Calcutta in April.

Supporting Operations – Other Ships

This narrative of the Burma Operations has so far dealt with the role of the coastal forces, landing craft, and the tasks carried out by the sloops”. Mention may also now be made of some of the other ships which visited Burmese waters in support of these operations, and of those ships which indirectly contributed to their success.

Deserving of mention were five little ships, auxiliary vessels which had been built as coastal craft specially for the Barisal-Chittagong run. Their size and draft made them particularly suitable for plying to and from Cox’s Bazar. The entrance to this port was difficult, and there were only a few ships in Indian waters capable of navigating the narrows at the entrance. HMI Ships Sandip, Sandoway, Selama, Sitakhoond and Nulchira, were loaned in early 1943 to the Eastern Army for transportation duties and were eventually paid off later in the year to the Inland Water Transport. HMIS Baroda was also on loan to the army in 1943 as a hospital carrier, and in April 1944 the Inland Water Transport took her over also.

Sea Transport

In October 1943 the Sea Transport Service in India commenced move “Vanity”, the largest and longest move of stores, vehicles and troops carried out up to that time in the east. The aim was the building up of the Eastern Army to meet the Japanese threat and to counter-attack in Burma, and the move was mainly between Vizagapatam, Madras, Calcutta and Chittagong. All these ports had been greatly developed to enable them to handle the new heavy loads; and bunkering, watering, victualling and stevedoring facilities had been rapidly and stevedorially improved. Between 20 October 1943, and 30 April 1944, when move “Vanity” temporarily ceased, Calcutta alone handled the following sailings:–

106 sailings of troop ships, carrying 137,824 troops.

99 sailings of M.T. ships, carrying 16,022 vehicles.

61 sailings of store ships, carrying 118,669 tons.

22 sailings of colliers ships, carrying 71,779 tons of coal.

25 sailings of hospital ships, carrying 9,781 patients.

From Vizagapatam, a total of 5,797 motor vehicles, 172 motorcycles, 1 trailer pump, 84 guns and 1,138 personnel were shipped between February and April 1944; a total of 32,000 tons of stores was shipped monthly. At Madras between 24 August and 15

October 1943, 33,756 troops and their equipment were handled by Sea Transport.

At Chittagong, to which most of these shipments, were proceeding, a total of 128,900 troops and 16,039 vehicles was handled between 1 September 1943 and 29 February 1944, and in the same period 202,241 tons of military stores were landed, and some 87,780 tons loaded for Cox’s Bazar and Maungdaw. The daily average of stores received in, and despatched out, rose from 606.2 tons of imports and 180 tons of exports in September 1943 to 1,661.1 tons of imports and 790 tons of exports in February 1948. On one day in February 3,000 tons of stores was handled in 24 hours.

Escort Duty

The transport of so many troops and so much valuable equipment carried with it, of course, a huge escort commitment. Many HMI ships, trawlers, fleet minesweepers, and auxiliary antisubmarine vessels were employed on these arduous and monotonous duties between Madras and Chittagong and intermediate ports. It was on one such run, escorting convoy J. C. 36, on 11 February 1944 that HMIS Jumna in company with HMAS Launceston, and HMAS Ipswich, sank a U-boat which had torpedoed the merchantman Asphalion. As will be seen Royal Navy ships of the Eastern Fleet, and also Australian warships, assisted the Royal Indian Navy in this work; the following HMI ships participated over various periods:–

HMI Ships Jumna, Cauvery, Kistna, Sutlej, Narbada, Hindustan, Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Baluchistan, Bihar, Carnatic, Kathiawar, Konkan, Kumaon, Orissa, Oudh, Rohilkhand, Berar, Baroda, Madura, Agra, Lahore, Patna, Calcutta, Shillong, Ahmedabad, Cultack, Amritsar, Lilavati, Kalavati, Netravati, Pansy, Ramdas, Satyavati, St. Anthony, Irrawaddi.

Midget Naval Units in Action

One of the smallest self-contained units in the amphibious Arakan campaigns was RIN Beach Signal Stations. They took part in every major landing on the Arakan, normally “setting up shop” on assault beaches within fifteen minutes of the first wave. “At a beachhead when I landed at H-Hour plus forty”, wrote an RIN Observer, “an advanced party of this Station was already comfortably sconced in a palm-thatched dugout and were sending and receiving messages in a quantity that would have done credit to a metropolitan telegraph office. Official correspondence referred to them as 21 BSS (RIN). They were an integral part of the RIN’s landing craft wing but, in the Arakan, they were

completely self-sufficient. Their two officers between them did the work which in larger naval units was done by engineer, electrical, victualling, pay and clothing officers. They were vital to every landing – a midget organization which did a giant’s work”.

A Radar Barge

War at sea always carries with it the hazards of navigation and weather as well as of the enemy. In January HMIS Bihar was detailed to tow a 100 ton radar barge from Chittagong. Ship and barge sailed on 4 January and at 0200 on 6 January the weather suddenly deteriorated, and violent squalls struck the ship. The barge became unmanageable, and finally the tow parted.

During the night the barge was not visible, but was held by the Bihar’s radar. When she was sighted again in the morning, it was found that the crew had abandoned the barge which was listing about 20° to port and rolling heavily. Two volunteers from the Bihar (S/Lt. A. M. G. Brown, RINVR and S/Lt. (E) J. R. C. Philips RINVR) boarded the barge, and at considerable personal risk steered it while it was towed to Oyster Island. These officers were later mentioned in dispatches.

Ancillary Duties

In November 1944, HMIS Ahmedabad and HMIS Patna both made trips to Teknaaf, escorting LCTs. In early 1945 HMIS Konkan and Kathiawar were part of the escort of the Kyaukpyu assault convoy, and in January and February HMIS Baluchistan and Kathiawar had been on escort work between Chittagong, Akyab, Teknaaf and Kyaukpyu.

Motor Minesweepers

February 1945, saw the first Royal Indian Navy minesweepers in Burmese waters, when Motor Minesweepers 129, 130 and 131 arrived in Akyab under the orders of Commander, Minesweeping, Bay of Bengal. Their first duties were to sweep approaches to Akyab for magnetic mines. Thereafter, the ships were employed on odd jobs in support of.general operations. They carried troops and stores from Myebon to Ruywa, carried out ferry control and block ship duties in Ruywa Chaung, and escorted Landing Craft Mechanized store ship, Harbour Defence Motor Launches and Motor Fishery Vessels between Kyaukpyu, Ruywa and Akyab. MMS 130 and 131 left Burma in April, but 129 stayed till May, having been employed for a month on degaussing range duties at Akyab and Kyaukpyu.

Burma: RIN Operational Area

On to Rangoon D-Day: 2 May 1945, H-Hour: 0800

In April 1945, the newly-formed 37th Minesweeping Flotilla began to assemble at Mandapam, to prepare for the last great operation for which the service had been working and planning for three long years. Operation “DRACULA”, the assault on Rangoon, was at last on. The Flotilla consisted of Bangor and Bathurst class Fleet Minesweepers, HMI Ships Bengal, Bombay, Punjab, Bihar, Kumaon, Khyber, Orissa, Rajputana and Rohilkhand. In company were four Basset trawlers, HMI Ships Agra, Lahore, Patna and Poona who were to act as danlayers for the Flotilla.

Preparation

The Flotilla worked up at Mandapam, and after boiler-cleaning at Colombo, sailed on 16 April for Akyab, where it arrived on the 20th. Between 21 and 28 April there were further Flotilla exercises, and on 29 April the Flotilla sailed from Akyab for Rangoon, joining up on the way with the huge assault convoy, among whose escorts were the sloops Sutlej and Cauvery.

Assault

On 30 April the Kumaon parted company with the rest of the Flotilla, and proceeded to a position 13 miles south-west of Alguada, in order to mark accurately the starting point for the clearance sweep of the area. For the Navy, the Rangoon River findings were yet another case of bold planning paying off. It was an operation that could have been extremely hazardous. The Navy emerged with flying colours. The credit for success in no small measure goes to the paratroopers and Allied air forces who made the naval landings tenable. Our little ships and landing craft with no support from big naval guns, audaciously entered the river at dawn, sailed nearly halfway to the port of Rangoon to put our land forces ashore on either bank of the fast flowing muddy Irrawaddi river. The Japanese made no move to intervene. At last they reached the assembly base where ships had been massing for days with a convoy of packed landing craft and large supply vessels. A signal flashed down. The presence of columns of ships gave them an additional fillip. It was just then announced that Germany had offered unconditional surrender. The troops in the ships ahead waved and cheered when they heard that news. A four hundred mile passage lay before them and at that time of year, monsoon had begun and there was every chance of meeting bad weather. One ML lost the use of an engine soon after leaving harbour but si niggled determinedly to keep up. Refusing to turn back, she

lagged further and further behind until it was almost lost to sight. But a few hours later they saw her creeping up on them and at last she was back in station with repairs completed.

Protected by sloops of the Royal Indian Navy the convoy steered to the rendezvous on the mouth of the Rangoon river entirely without incident. Other convoys, heading in the same direction, passed them on or were overtaken. In the distance carriers with their escorts shadowed their course. It was the middle of the night when they arrived at the rendezvous. Troop carriers and ships of all sizes were already assembled. A fitful moon intermittently lit the scene as troops piled from the big ships into small assault craft. To their south lay the powerful units of the East Indies Fleet including battleships and aircraft carriers which secured them from surface interference. Skilful seamanship was required in that strong tide and swell to get the landing craft lowered, and with their light escorts they set off to the assault.

Eleven months earlier many of those ships, officers and men had been engaged in another “D-Day” and as the landing craft slipped away on their thirty-one mile run into the assault beach the thoughts of many flew back to 6 June 1944. The passage to Rangoon river was four times as long. The distance which the little assault craft had to cover from their parent ships to the beach was the longest in the history of amphibious war, and this time there was no reassuring crash from the big guns of the Fleet to cover the landing. Bombardment from big ships was ruled out by the shallow water, and for supporting fire reliance was placed on the motor launches and the guns mounted on the landing craft. “In this Assault, Royal Indian Navy was proud to play a minor but nevertheless a worthy part” wrote a Royal Indian Navy observer. Two sloops HMIS Sutlej and HMIS Cauvery which had helped.escort convoys to the mouth of the river now stood ready to bombard shore positions if required.

The convoy arrived at the lowering point off the mouth of the river and the intricate task of putting soldiers into assault craft was carried out in darkness and heavy rainstorm which drenched the troops. The apparent confusion as hundreds of craft manoeuvred for positions rapidly resolved itself into orderly formations, and at dawn a splendid spectacle presented itself of twin assault forces destined for east and west banks of the river complete with guns, tanks and supporting weapons moving off on the flood tide exactly according to schedule.

It was important for the troops to move up the river with a strong six-knot tide in their favour according to schedule, disembark ii H-Hour and allow craft to return to their ships on ebb tide for the next wave of the Assault Force. Everything went as planned and the initial landings met with little opposition. In this assault a major part was played by Indian troops. In addition to paratroopers who were dropped on Elephant Point at the mouth of the river on D-minus-one and had successfully secured their objective, the first wave included the Jats, Frontier Force Rifles and Eighth Gurkhas On the west bank and Garhwalis, Lincolns and First Punjabis on the east bank of the river, while Sherman tanks of the 19th Lancers supported the assault. A naval feature of the assault was the support provided by landing craft guns which were intended to eliminate Japanese strongpoints by close-range bombardment. Air bombing, which preceded the landing was also heavy and effective.

Thus history repeated itself. In the Arakan Operations of 1855, a combined Naval Force of the Royal Navy and the Indian Marine commanded by Commodore John (Bully) Hayes of Indian Marine took Akyab and Kyaukpyu by assault in rapid succession, while in 1852 another Naval Force sailed up the Rangoon river and captured the city. In that force was included the father of Lieut. General Sir Philip Christison who now commanded the XV Indian Corps which was responsible for the conquest of Arakan.

The first ship of the invasion Fleet to take up position off the mouth of the Rangoon river was HMIS Punjab. She belonged to a naval force which, consisting of escorting vessels (fleet minesweepers) of Royal Navy and Royal Indian Navy, went ahead of the main convoy of troopships and landing craft. This force prepared for the convoys safe arrival by marking the anchorage and tank lowering positions the day before D-day. Navigating skillfully into unswept waters where danger of mines was greatest, -Indian warships with gun crews at the first degree of readiness, in view of periodical air raid warnings, led the way at the approaches of the Rangoon river sweeping a passage clear and enabling mark vessels to be stationed and danbuoys to be laid. The task was made more difficult by atrocious weather with strong tidal currents running and visibility often down to 50 yards. Suffice it to say that the Royal Indian Navy minesweepers swept the channel for the first convoy enabling it to proceed up the Irrawaddi delta and into Rangoon. No mines were cut or detonated during the operation.

The capture of Rangoon on 2 May 1945 was not the end of the Burma campaign, but it was the visible token of success. The

1945 campaign had been fast and had been crowned with complete success. Burma was free again.

The ships of the 37th Minesweeping Flotilla remained at Rangoon for some days, carrying out various duties, and by mid-May they were all back in India.

After the Victory

It remains now only to gather up a few loose threads, and to mention the part played in the final clearance of the Yomas and Tavoy area.

After the capture of Rangoon, the army in the south of Burma was reinforced from India, and in this movement HMIS Llanstephan Castle and HMIS Sonavali now employed as a store-carrier, took part.

In the Victory Review held by Admiral Mountbatten on 15 and 16 June the RIN was represented by HMIS Barracuda (she had come down from Kyaukpyu to service Royal Navy motor launches in May) and HMIS Assam. The latter vessel, a corvette, was then based on Rangoon for escort duties between the port and Akyab, Kyaukpyu and Chittagong.

Anti-Escape Patrols

During May, June and July, HMI sloops maintained day and night patrols in the Andamans Sea, and off the Tenasserim and Tavoy Coasts, to prevent the escape of small parties of the Japanese by sea. HMI Ships Cauvery, Narbada, Godavari, Kistna, Sutlej and Hindustan visited many little known islands in the Mergui Archipelago, the Forrest Strait, and the Moscos and Bentinck Group, in order to foil attempts at escape.

The RIN had played a worthy part in the liberation of Burma. In few campaigns has there been such intimate or more successful co-operation between sea and land forces as in this one. It was made possible, in the first place, by the unique nature of the Arakan coast, where the maze of chaungs and inland waterways flanked so much of the terrain over which the army fought; and in the second place, by the combination of survey and seamanship which enabled these flanks to be utilised to the full by the Navy’s shallower-draught craft. Lt/Gen Sir Philip Christison paid tribute to officers and ratings of the RIN on the capture of Rangoon. In a letter to the Flag Officer Commanding, he said:–,

“The Arakan campaign is now virtually over. Since I last wrote to you the work of all Officers and Ratings of the RIN has

maintained its high standard and the spirit of co-operation and comradeship had been maintained in the face of all difficulties.

“The Operations in which we have recently been engaged in narrow chaungs lined by mangrove swamps and often overlooked by Jap held hills, with swift currents and large rise and fall of tides, had called for great skill, seamanship and courage. These qualities have enabled us to carry out operations never before attempted by any British forces.

“I am extremely grateful to all of them for what they have done, and all ranks of XV Indian Corps are very proud of their comrades. We will always remember fighting besides them.

“An outstanding feature has been the maintenance of Craft over a long period under the most difficult circumstances, and the high serviceability state kept up has enabled us to build up our Assault forces rapidly before the enemy had time to react.

“I congratulate all those concerned and I hope we shall have you with us for future Operations”.

The work of minesweepers of the Royal Navy and the Royal Indian Navy won recognition. They were engaged in clearing a channel up to the port of Rangoon, so that Allied shipping might once more steam up to Burma’s capital. Indian and British sailors on board these minesweepers toiled without respite, in danger of being blown up by mines and in the face of bad weather, opening up navigational channels, initially to enable our troops to swarm ashore from landing craft and afterwards to allow the first convoy to proceed into Rangoon. The convoy route past the estuaries of the Bassein, Irrawaddy & Rangoon rivers was swept for mines by these minesweepers. An anchorage was prepared outside the Rangoon river, and from it the landing craft, went ashore on D-Day. Everything had to be done quickly in accordance with a set programme which was adhered to strictly and in certain respects work was finished ahead of the schedule.

One of the riskiest jobs was undertaken by HMIS Punjab, who without knowing the state of Japanese preparedness ashore had to steam in front of the minesweepers and station herself at the mouth of the river where she risked a fusillade from hostile artillery – a risk that fortunately did not materialise. It was more than a possibility that the Japanese had sown mines in the river approaches and the minesweepers got to work immediately on arrival, braving all risks. When the convoy arrived, it found that the danger areas had been searched and that channels and an anchorage had been prepared for it.

A particularly dangerous role was assigned to a force of auxiliary minesweepers of the Royal Navy. These drew less water than their consorts and were therefore given the task of proceeding into the Rangoon river and sweeping the shallow reaches as well as the navigational channel. They took with them surveying parties to ascertain and mark out the navigational channel and to make points of bearing ashore more conspicuous. As there was no time to lose, these minesweepers proceeded on D-Day into the river while the rest of the force continued outside widening the approach channel already swept. It was believed that the estuary was mined and, in fact, the little minesweepers steaming bravely in formation found a number of mines on the first day in the river and bagged others during the next 48 hours. All the time the surveying parties were at work and buoys were being laid along the route that the minesweepers had cleared.