Chapter 7: W Force Moves Into Position

Movement of New Zealand Division to Greece

ON 24 February General Freyberg told his brigadiers that the Division was going to Greece. They were not free, even among themselves, to discuss the expedition and the movement in its initial stages would have the appearance of a divisional exercise. The unit commanders in their turn were warned that they would soon be moving to ‘a theatre of war’. Intense activity immediately developed in the Base Ordnance Depot where clothes and equipment, including topees,1 were issued and about the camps where equipment was checked and packed into the motor vehicles. The observant rank and file, who had been told nothing, thereupon decided that they were about to move overseas. Some oracles predicted a landing along the North African coast, others thought that the Division would be attacking an island base in the Aegean Sea and quite a number concluded that the objective would be on the mainland of Greece.

The movement orders which were issued by GHQ Middle East2 on 28 February bypassed HQ 2 NZEF and went straight to individual units. The Division was not going to embark as a complete formation. Lustre Force had been divided into flights within which units, and sometimes sections of units, would travel with similar detachments from the British and Australian divisions. On 3 March the assembly commenced, the first flight moving by road or by rail to Amiriya, a dusty transit camp on a windswept stretch of desert some 12 miles west of Alexandria. The loaded vehicles were then taken to the docks, the troops waiting until they received their final orders to move.

In the Suez area the movement was reversed. On 3 March, the day that the advance parties moved out from Helwan to Amiriya,

the convoy with the Second Echelon was steaming in from Britain. While the first arrivals, 23 Battalion and 28 (Maori) Battalion, were disembarking and entraining for Helwan Camp, General Freyberg and Brigadier Hargest were warning the senior officers of the echelon that they must prepare for yet another move. They had only three weeks within which to reorganise the brigade and receive new equipment, to complete their training schemes and harden the men after nine weeks at sea.

General Freyberg had then to make his own preparations for the move. On 5 March he called at GHQ Middle East to meet General Wavell after his return from the conference3 in Athens. The Commander-in-Chief gave him an outline of the defence plan but no estimate of the possible strength of Lustre Force. General Freyberg understood, nevertheless, that twenty-three squadrons of the Royal Air Force would be in support. This was encouraging information though he still had no illusions about the difficulties that Lustre Force would have to face.

The immediate problem was that of transport. The Naval Command had always realised that the Eastern Mediterranean could never be safe from the Axis forces that were operating from southern Italy and the islands of the Aegean Sea. But they had not expected the acute shortage of transport vessels which had developed in February after the enemy, by dropping magnetic mines, had closed the Suez Canal to all shipping. On 3 March, the day the Canal was to have been clear, more mines had been dropped, with the result that half the freighters and all the transports had to remain at the southern entrance. It was just possible for separate convoys of freighters to have the motor vehicles and heavy equipment in Greece before the arrival of the flight, but the troops, if they were to arrive on time, had to travel in the cruisers York, Bonaventure, Orion, Ajax Breconshire, and the motor vessel Ulster Prince.

The first flight embarked about midday on 6 March.4 In the notes which he made as they pulled out General Freyberg recalled the spring of 1915, when he had been with the Royal Naval Division before the landing on Gallipoli. After twenty-six years he was back with his own countrymen, better qualified to appreciate them and convinced that they had ‘a higher standard of talent and character’ than the men of any other unit he had known. If the troops in the first flight had known that he was of this opinion they would probably have been surprised but they would not have wasted any

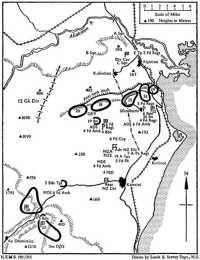

The German Plan of Attack and Alled Positions on 5 April 1941

time debating the subject. They were too busy enjoying the hospitality of the Navy and speculating as to their possible destination.

The General had hoped to reveal the secret to his senior officers in Egypt but events had moved so rapidly that he had to be satisfied with a Special Order of the Day5 which was to be opened after the ships were out of the harbour. Through it the men were told that they would be fighting in Greece against Germans; they were warned that they must steel themselves to accept the noise and confusion of modern warfare; and they were reminded that the honour of the Dominion was in their hands.

On 7 March, less than twenty-four hours after it had left Alexandria, the flight had its first sight of Greece. In the clear air of that spring morning the troops could see the outlying islands, and beyond them the harmonious outline of the still distant mainland. As the hours passed the sea changed to darker shades of blue, the white villages along the rocky coastline became more distinct and the isle of Salamis rose up above the waters to the west. At last about midday the cruisers swung east beyond a rocky promontory and the troops about the crowded decks had their first view of the harbour, the factories and the modern buildings of Piræus. Athens, only three miles inland, lay behind the slight rise to the north-east.

The Greeks, who had not expected the arrival of a British expeditionary force, were wildly excited. The seamen on the ships within the arbour cheered as the cruisers drew in; the excited people along the highway and the crowds in the streets of Athens gave the flight – and all successive flights – a spontaneous and tumultuous welcome as they went through to the staging areas outside the city. Kifisia, a summer resort on the lower slopes of Mount Pendelicon, had been reserved for the artillery regiments, the Army Service Corps companies and 1 General Hospital. The infantry brigades, each in its turn, encamped in the pine plantations on the western slopes of Mount Hymettus.

In the city itself Advanced 2 Echelon and Base Pay Office were established; Major Rattray,6 the New Zealand Liaison Officer, went to Headquarters, British Troops in Greece. At Voula, a pleasant resort along the coast to the south-east of Piræus, the Reinforcement Camp was set up.

The other flights did not always find it so easy to reach this new world. Some units enjoyed the comparative luxury of travel on the fast cruisers, but others had to endure a slow crossing on small cargo

vessels that came through after the Canal was cleared. They had not been built for such a ferry service. ‘Deck dwellers peered down the hatch at men, mess gear and packs pressed together in the holds, where past passengers – sheep – had left their trademark, and where the smelly air was hot and stifling.’7 The messing facilities were naturally very limited, the ships’ galleys providing tea and the men eating tinned meat and army biscuits.

Moreover, at this season of the year there was always the danger of severe storms. On 13–15 March the transit camp at Amiriya had heavy rain and then a memorable sandstorm that stopped the movement of all vehicles on the desert road between Cairo and Alexandria. The second flight8 which was at sea during 9–17 March consequently saw the Mediterranean at its worst. The Greek steamer Hellas, with Headquarters Divisional Engineers on board, was hove-to for a day; the Ionia, with 4 Field Ambulance and 19 Army Troops Company, had her holds battened down and was hard put to it to make two knots; the Marit Maersk with 19 Battalion drifted out of the convoy, was hove-to south of Crete and forced to put in to Suda Bay before she could go on to Piræus.

With the third9 and fourth flights which were crossing during 17–22 March it was not the weather but the Luftwaffe that was dangerous. Dive-bombers came over on several occasions but caused no damage until 21 March, when the SS Barpeta had a near miss and a tanker was hit and had to be towed off to Suda Bay.

The fifth10 flight with the much-travelled 5 Brigade crossed during 25–29 March, the period of the naval Battle of Matapan. On 27 March, when the convoy was south of Crete, the Admiral learnt that the Italian Navy was steaming into the Aegean Sea. The convoy was ordered to steam on as a decoy and, after nightfall, to reverse its course. Next day when the battle took place it was well out of the way, though the diversion meant another twelve hours at sea and an unexpected arrival at Piræus on the evening of 29 March. With no unit vehicles waiting for them, 23 and 28 (Maori) Battalions had to march the ten miles to Hymettus Camp; 21 Battalion went by train, 22 Battalion by motor transport.

The major portion of the New Zealand Division was then in Greece. The only New Zealanders with the sixth flight on 1–3 April were 7 Field Company, the Mobile Dental Unit and a detachment from the YMCA. A seventh flight was at sea on 6 April when the German invasion began, but as chance would have it no New Zealanders had been detailed to go with it.

After that date it would have been foolish for General Wavell to send any other troops to the Balkans. The armies of Yugoslavia were disintegrating and it was doubtful if a solid front could be established. In North Africa the situation was even more disturbing. On 31 March Rommel had opened that spectacular counter offensive by which he was to recover Cyrenaica, surround Tobruk and threaten Egypt. Instead of sending 7 Australian Division and the Polish Brigade to Greece, Wavell retained them in Egypt and eventually sent them as reinforcements to Tobruk. The seventh flight was consequently the last to reach Greece. The transport vehicles of 10 Railway Construction Company had been shipped to Greece, but the personnel and a composite section from the Railway Operating Companies, who were to have sailed with an eighth flight, and 21 Mechanical Equipment Company which was to have moved with a ninth flight, never left Egypt.

W Force Moves into Position

At the Athens conference11 on 2–4 March the final arrangement was that three Greek divisions from the Central Macedonian Army would assemble with all possible speed and take over a sector of the Aliakmon line. The British, Australian and New Zealand troops of Lustre Force, henceforth to be known as W Force, would be sent north as rapidly as possible to take over the remainder of the line. All units, both Greek and British, would take their orders from General Wilson who, in turn, would be under General Papagos, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in Greece. For security reasons and because the Greeks did not wish to provoke the Germans, General Wilson was to remain incognito with the pseudonym of Mr Watt until the German attack was about to be launched.

After the conference General Wilson made a swift reconnaissance of the Aliakmon line, a natural but as yet unprepared defence system that extended from the Gulf of Salonika to the border of Yugoslavia. To approach it the Germans now moving into Bulgaria would have to break through the Metaxas line and cross the plain of Macedonia. Once they were past Salonika and over the Vardar (Axios) River,12 they had the choice of attacking several different gaps in the mountain ranges. South of Mount Olympus the

railway and a third-class road turned west through the Pinios Gorge (the historic Vale of Tempe) to Larisa. Immediately north of the mountain a narrow but well-formed road went through Olympus Pass to Elasson. South-west from Veroia the main highway went over the ranges to Kozani, and still farther north to the west of Edhessa a pass linked the Salonika area and the small plain about Florina.

As the forcing of any one of these passes would be long and costly, it was quite possible that the Germans might attempt to turn the left or northern end of the Aliakmon line by way of Yugoslavia and the Monastir Gap. Should Yugoslavia object to such movement across her territory she would almost certainly be invaded, and much would then depend upon her powers of resistance. If she was unable to halt a German thrust towards Monastir the Aliakmon line would have to be adjusted. Units would be withdrawn from Edhessa and Veroia, the Mount Olympus sector would be retained, and a new line established westwards from there to Servia and the Greek sector about Grevena. The highways which came south from Florina and Kastoria would thus be blocked.

To cover the concentration of W Force, Greek units would be sited on the three main routes: 19 (Motorised) Division in the coastal sector, 12 Division in Veroia Pass and 20 Division in Edhessa Pass. In due time the New Zealand Division, with 19 (Motorised) Division on its right flank, would, take over the coastal sector. Adjoining it to the west in the Pierian Range would be regiments from 12 Greek Division. The defence of the Veroia Gap would be the responsibility of a brigade from 6 Australian Division. The Vermion Range, the Edhessa Pass and the rugged Kaimakchalan sector on the border of Yugoslavia would be held by 20 Greek Division and the remainder of 12 Greek Division. On the Macedonian Plain to the east of Edhessa 1 Armoured Brigade would hold the line of the Axios River in order to delay the enemy and cover the parties preparing demolitions.

While movement orders were being prepared, General Freyberg, with Colonel Stewart, went by air to Larisa and then motored to Kozani. From there they went through the pass to Veroia and returned by way of Katerini and Olympus Pass to Larisa and, eventually, to Athens. The General was impressed by the commanders of the Central Macedonian Army but disturbed by the sight of 12 Greek Division moving into position: ‘their first line transport was composed entirely of ox wagons and pack animals which of course could only travel a very limited distance in a day at a very slow speed – actually at a slower pace than troops could march.’13

On 9 March he received his orders from W Force Headquarters. There had been some changes in the plan which had been drawn up at the conference in Athens on 2–4 March. In the southern sector the line had been swung north from Mount Olympus to include the great triangle of open ground between the mountain range and the Aliakmon River. The Division, less 5 Brigade as Corps Reserve behind Veroia Pass, would be responsible for the quadrilateral between Meliki, Neon Elevtherokhorion, Katerini and Mega Elevtherokhorion. The Greek divisions which were already in the sector would eventually be withdrawn, leaving the New Zealanders with a front of 15 miles: from the coast to the ridges of the Pierian Range immediately north of Mount Olympus. In the more level country adjoining the coast a deep anti-tank ditch was now being dug, but even with this barrier the defence of such an extended front was no ordinary task for two infantry brigades.

To make the situation still more difficult there were serious problems of time and transport. As a result of the dispersal of the units throughout the different flights, men who should have been among the first to reach Katerini were held back for days or even weeks. The GSO I and the AA & QMG had travelled with General Freyberg but the other members of his staff did not reach the area until 25 March, nearly a fortnight after the arrival of the advance party. The artillery units required time for the preparation of their positions but they were among the last to move in, 7 Anti-Tank Regiment, in particular, appearing only a few days before the German invasion. Once the units arrived in Greece the hastily organised base headquarters in Athens did its best to send them forward, but that was not always easy to organise. If the flights were delayed by bad weather or by the activities of enemy aircraft, there had to be alterations and adjustments in the movement orders that caused the greatest anxiety. Moreover, the staff had always to remember that between the transit camps about Athens and the divisional area at Katerini there were 250 miles of indifferent roadway and a succession of great mountain ranges.

New Zealand Division Moves up to Katerini

The first group to move north – Lieutenant-Colonel G. H. Clifton, 6 Field Company and 2 Armoured Division Light Field Hygiene Section14 – left Hymettus for Katerini on 11 March. At

that date there was still rain, sleet and even snow, but for the majority of the Division who moved up towards the end of the month there was all the charm of the Balkan spring, the most enjoyable season of the year. In other months the countryside is dry and bare, for there are few grasses in Greece, but throughout March and April the fields are green with wheat or glowing with asphodels and poppies. In the forests and shaded clearings below the budding oaks and plane trees there are hyacinths, anemones, irises, crocuses, violets and Stars of Bethlehem. And on what would soon be dusty hillsides, pinks and campions, violas and saxifrages flourished in the shaded clefts and cracks.

On the route itself, whether the units went by road or by railway, there was a succession of plains or river valleys separated by ridges that were often high and always formidable. There was little choice of movement. The passes that had once been forced by Persians and Macedonians were the passes through which engineers had constructed railways and through which the battalions of the Commonwealth were to advance and retreat within the next few weeks.

The first stage of the journey was along the Sacred Way from Athens to Elevsis and then north through the hills to the defile of Citheron and the rolling vineyards outside the historic town of Thebes. Here the streets were pink with almond blossom and the famous springs gushed water at every fountain head. Beyond the town the road turned west and the company went up the valley to Levadhia, where it halted for the night. In the gorge beyond that picturesque town men had once consulted the oracle and found the waters of Memory and Forgetfulness.

Next day they moved on, with Mount Parnassus dominating the landscape to the west and great ridges rising to the north. In another age the company would then have turned north-east to the gap between the ridges and the sea which is known as the Pass of Thermopylae. At its narrowest it is wide enough for a road but for little else; there is the shingle beach on one side and 500-foot cliffs on the other. In its more open stretches the scene becomes enchanting: caiques may be anchored close in to the shore; the cliffs are still precipitous and the road is fringed with tall pine trees. In the open country to the north there is the village of Molos, the blue sulphurous stream from Thermopylae, the ancient aqueduct and then the silted plain with the Sperkhios River and the straight road to Lamia.

The railway and modern highway do not use the Pass of Thermopylae. They follow the more direct route to the north-west across the range by way of Brallos Pass. Those who went

north by train remember the slow climb up the valley, the shaded gorges with stands of oak and pine, the succession of tunnels, the great bridge15 across the Asopos River and the run out across the Sperkhios valley to the west of Lamia, a town at the foot of the Othris Range. Sixth Field Company and other road parties recall the succession of curves by which they climbed above the gorges and the railway bridges. The hillsides were a mass of vegetation: myrtle, broom, thyme, Judas trees, wild olives and mountain oaks. The crest of the pass was in a world of pines and firs: ‘ – it was a wonderful sight from the top with the road zigzagging downhill in hair-pin bends, straightening out at the bottom and making a bee-line for Lamia at the far side of the plain. At every village the people gave us a wonderful reception – threw flowers, waved and cheered, and whenever we stopped, brought us wine and eggs. All the schools were closed for the duration, and the children were there in hundreds.’16

The Othris Range beyond Lamia was the next obstacle. The railway line followed the north side of the Sperkhios valley and broke through the hills past Lake Xinias to the south-west corner of the plain of Thessaly. There was a second-class road running eastwards round the coast to Volos, a port from which a narrow-gauge railway and a bad road went through the hills to Larisa, the key town of Thessaly. The main highway ran between these two routes. Climbing north over scrub-covered hills, it reached the plain about Lake Xinias and then went over another ridge near Dhomokos to the undulating country about Pharsala and on to the plain of Thessaly, almost bare of trees, but well cultivated, studded with small villages and encircled by high mountains.

The chief town, Larisa, was not altogether at its best, having been shaken by an earthquake17 only a few days before and bombed on several occasions by the Italians, but it was obviously the key town of central Greece. The railway turned north-east to the Pinios Gorge, the Platamon tunnel and Salonika; to the north through Elasson, Kozani and Florina ran the highway to Yugoslavia; and north-westwards, by way of Trikkala and Kalabaka, was the road to Albania. The company kept to the highway, crossing the Pinios and Titarisos rivers and spending the night at Tirnavos. On 13 March, a cold day with some swirling snow, they went through the hills to another, but much smaller, plain on the northern edge of which was Elasson, a market town remembered for its Turkish minarets. North and across the valley, beyond the monastery with the golden dome, was the narrow pass leading to the bridge

beside the village of Elevtherokhorion. Beyond it there was yet another plain across which the highway continued north to Yugoslavia and a secondary road branched north-east to Olympus Pass and Salonika.

The route for 6 Field Company lay across the plain and up through the forested foothills to the crest of the pass. Mount Olympus was now to the south of them, white with snow and often obscured by clouds. Below them at the head of the gorge was the village of Ay Dhimitrios, where No. 1 Section remained to improve the road. In the next ten miles the forest changed imperceptibly from fir to pine, to oaks and beeches, to plane trees and finally to the shrubs of the foothills. Here No. 3 Section was left to ease corners, construct passing bays and generally improve the surface of the road which the engineers thought ‘wasn’t so bad, ... the main jobs were widening a few of the hair-pin bends and some of the culverts, but it was a pretty tricky road much like some of the back-country roads in New Zealand, and a big change from Egypt.’18

Company Headquarters and No. 2 Section then continued on their way across some 12 miles of undulating country on which shepherds watched flocks of long-tailed sheep and farmers ploughed the open fields for crops of maize and tobacco. A straight stretch of road lined with poplar trees took them into Katerini, a flourishing country town with a market square, a railway station and public gardens. The engineers, and for that matter the whole Division, had not yet been issued with bivouac tents so they were billeted19 in houses and public buildings. In this case it was only for two days, the men finding it much more convenient to be back at the base of the pass, where they worked until their services were required after the arrival of 4 and 6 Brigades.

The next unit to leave Athens was 18 Battalion. The road party with the transport vehicles left on 12 March, followed the route of the engineers and reached Katerini the following evening. But it was different with the main body of the battalion: the rifle companies and the Bren-carrier platoon. They started the fashion for the majority of the Division and went up by train, leaving Athens on 13 March and reaching Katerini twenty-two hours later.

The journey was one that no soldier ever forgot. Sometimes there were old-fashioned carriages, but for the most part the troops were in goods wagons, horse vans and cattle trucks. ‘Dry rations, tins of bully beef and stew and some bread were carried on the

train. Tea was made with the aid of primus stoves, and luxuries like eggs and fresh Greek bread, brown and nutritious, could be purchased at some of the wayside stations.’20 The route across the succession of plains and valleys had been much the same as that of the highway but in the mountain sectors there were pronounced differences. Instead of windswept passes and great panoramas there were precipitous cliffs, heavily timbered gorges, the Asopos bridge, the charming Vale of Tempe and the coastal strip between the Platamon tunnel and Katerini, with the sea on one side and the timbered ridges of Mount Olympus on the other.

In Katerini the battalion spent several days waiting for instructions. The companies marched and trained; the transport platoon shifted road metal for the engineers; and in the evenings the rank and file enjoyed the hospitality of the township, sipping ouzo, a close relative of vodka, and sampling such wines as krassi and mavrodaphne.

By this time General Freyberg, having returned through the now snow-covered passes, was discussing with the Greek commanders the boundaries of the divisional sector in the Aliakmon line and studying with Colonel Stewart the defence positions for 4 Brigade. The final decision was that the brigade should move beyond Katerini and fill half the gap between 19 Greek Motorised Division on the coast and 12 Greek Division in the mountains; 6 Brigade when it arrived would go to the west of 4 Brigade and take over the rest of the sector. In other words, the brigades would share a front of 12,000 yards, much of it along low ridges studded with oak saplings.

For 18 Battalion this meant the end of its pleasant sojourn in Katerini. On 18 March it moved out, A and C Companies to cover the demolition parties in Olympus Pass, Battalion Headquarters and the other companies to Mikri Milia, a village in the open country between Katerini and the Aliakmon River. As the other battalions had already left Athens, they appeared shortly afterwards and went straight to their respective areas. Twentieth Battalion, which arrived on 19–20 March, had to prepare positions at Riakia, a village three to four miles west of 18 Battalion. On 20–21 March 19 Battalion, as brigade reserve, arrived to assist the other units and to replace the companies which 18 Battalion had sent to the pass.

Brigade Headquarters was at Palionellini, where the supporting units were now assembling. No. 1 Section 6 Field Company, which had been brought down from Olympus Pass on 17 March, was assisting in the preparation of roads and defensive positions. Fourth

Field Ambulance, which had reached Katerini on 18 March, had, before the week was over, an Advanced Dressing Station burrowed out of a ridge to the north of the village and its Main Dressing Station to the west of Katerini in the village of Kalokhori, where there were already Headquarters New Zealand Division and the office of the Assistant Director of Medical Services (Colonel Kenrick). Fourth Field Hygiene Section which arrived on 20 March was established beside the Main Dressing Station. As malaria was prevalent in summer the unit, in addition to checking the water supply and the sanitary arrangements, had to drain pools and ponds and oil all standing water in which mosquitoes might breed.

The Monastir Gap

There was one serious weakness in this Aliakmon line; it could be turned from Bulgaria by a force which did not directly attack Greece. By driving hard across south-east Yugoslavia the Germans could reach Monastir and then thrust south across the border of Greece to Florina, to Kozani and to Larisa. However, this danger had been accepted in the hope that either the neutrality of the Yugoslavs would be respected or that they would prevent access to Greece by force of arms. Should the Germans overrun Yugoslavia, it was Papagos’s intention to withdraw his Greek armies in Albania to link with the left flank of W Force.21

Arrangements22 had been made for a special reconnaissance squadron to operate in such forward areas as the Monastir Gap and to provide communications direct to Headquarters W Force. But this was not sufficient; there had to be a defence force to hold the range which overlooked the southern edge of the Florina area.

On 17 March Brigadier R. Charrington, the commander of 1 Armoured Brigade, was warned that the Germans, if they reached the Monastir Gap, could turn the north flank of the Aliakmon line. In view of this threat the cruiser tanks of 3 Royal Tank Regiment which were then on their way up from Athens were not detrained on the eastern side of the Aliakmon line; they were sent north towards Salonika and then back through the Edhessa Gap to be the nucleus of a force which would assemble about Amindaion, a small town just south-east of Florina. The other regiments remained in Macedonia but they had to be prepared to close the Monastir Gap. If the Germans came across Macedonia to the Aliakmon line, 1 Armoured Brigade would not withdraw southwards ‘over lovely A/T positions’23 to the coastal sector held by the New Zealand Division. It would pull back through the Edhessa and Veroia gaps

and become part of the force that was now assembling about Amindaion.

On 20 March General Wilson was still apprehensive about the chances of an attack from the direction of Monastir. In a letter to General Freyberg he mentioned the steps that he was taking to meet such a threat. ‘Some medium artillery and I believe a MG battalion may be ready to move within the next week. I am also taking their destinations up with Papagos, but I am anxious to increase the reserve consisting of the 3 RTR at Armintion [sic] and will probably send a good proportion there.’24

This explains why on 21 March 27 New Zealand (Machine Gun) Battalion, less one company, received orders to move to Amindaion. Next day Brigadier E. A. Lee,25 of 1 Australian Corps, was warned that if an attack developed in that quarter he was to command 3 Royal Tank Regiment and 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion. In the meantime he was to advise General Kotulas on artillery matters.26 Later 2/1 Australian Anti-Tank Regiment (less one battery) was added to his command.

The advance party from 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Gwilliam,27 left Athens on 22 March and followed the main highway through Larisa to Elevtherokhorion. But instead of branching north-east to Mount Olympus it continued north to Servia Pass, a gap in the northern hills which was afterwards defended by 4 Brigade. The town of Servia was below the escarpment; the Aliakmon River, about to enter the gorge in the eastern hills, was only a few miles farther on; and beyond it there was a long, gradual rise to Kozani, a substantial town from which roads radiated eastwards to Veroia and Salonika, northwards to Yugoslavia and westwards to Albania.

From the wide ridge or plateau about Kozani the road to Yugoslavia descended to skirt the western edge of another plain and then passed through the Komanos Gap, a neat cleft in the low ridge which overlooks the straggling town of Ptolemais. Continuing north, it went through Perdikha and over undulating country until it reached Amindaion, a village set in poplar trees above the blue waters of Lake Petrais; south-west there were the marshes about Lake Roundik; and north again, beyond the two lakes, were high scrub-covered ridges.

The arrival of the machine-gunners came as a surprise to the commander of 3 Royal Tank Regiment, for he had received no warning orders and knew nothing about Brigadier Lee to whom the New Zealanders had to report. Somewhat baffled, Lieutenant-Colonel Gwilliam waited for the Brigadier, who did not arrive until 26 March.

Until then he spent his time inspecting the area. In the ridges to the north was Klidhi Pass (‘the key’), by which the road and railway reached the level country east of Florina and fringing the border of Yugoslavia. At first sight this mountain basin was not unlike the Mackenzie Country in New Zealand. But there were no fences whatsoever; a few peasants were ploughing with teams of slow-paced oxen; and about the foothills were white-walled, red-tiled villages. Strategically it was an important area, the meeting place of roads from Salonika, from Yugoslavia and from central Greece and Albania.

The two commanders eventually decided that two machine-gun companies would be forward of the ridge covering the approaches to the pass, one company to the east in the Lofoi area and the other to the west near Palaistra. A third company would deploy on the ridge immediately west of the pass, with the level plain before it patrolled by 3 Royal Tank Regiment. Once these decisions had been made the advance party picked out gun positions and prepared for the arrival of the battalion.

The convoy had left Athens on 25 March and was now well on its way. Three companies were to have gone to Amindaion, but Freyberg had signalled W Force Headquarters that he needed two not one. Nos. 3 and 4 Companies28 had consequently turned off at the Elevtherokhorion junction and gone over Olympus Pass. The others were moving north and finding it ‘a pleasant enough drive through terribly rough country with tiny villages and desperately poor peasants.’ Even so they were given a wonderful reception. There was always a Greek returned from America who could act as interpreter, garlands of flowers would be distributed and glasses of wine handed out to the noble allies.

At last on 28 March the battalion reached Amindaion. No. 1 Company was then sent to Lofoi, 2 Company to Palaistra and Battalion Headquarters with Headquarters Company to a position just off the road to the north-west of Amindaion and near the southern entrance to the Klidhi Pass. Their first task was to make a detailed reconnaissance of the area in front of the pass and to study the tracks over the hills to the rear in case they had to withdraw from their positions on the plain. There was, however,

an element of uncertainty about all this work. ‘After we got there plans were always changing and we had several alternative positions. We did not know what force would come up.’29

The Coup d’état in Yugoslavia

The uncertainty of those in command at Amindaion was not difficult to explain. General Papagos had never given up his hopes of holding the Metaxas line, thereby checking any thrust from Bulgaria and covering the Axios valley through which the Allied supply line from Salonika would have to enter Yugoslavia. Moreover, if that country did support the Allies and if her army was as strong as many military experts declared it to be, then there would be no need for a stronger force about Amindaion. The British commanders, on the other hand, had always argued that the Allies without the support of Turkey and Yugoslavia had not the strength to retain the Metaxas line, Salonika and western Macedonia. In their opinion, and they had won the argument,30 the greater part of the Central Macedonian Army had to be withdrawn to the Aliakmon line. To prevent the Germans driving through Yugoslavia and turning the northern end of that line, General Wilson had consequently been assembling the force at Amindaion.

But events in Yugoslavia had been causing complications. On 25 March, the day on which 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion had moved north from Athens, the Yugoslav Government adhered to the Tripartite Pact with Germany. General Papagos, accepting the situation, had then been prepared to withdraw his troops from eastern Macedonia to the Aliakmon line. Shortly afterwards, however, news arrived that the people of Yugoslavia were dissatisfied with the pact. Acting on this information Papagos declined31 the offer of British transport and kept his divisions in eastern Macedonia. The coup d’état of 27 March which changed the government in Belgrade was definite proof, so far as he was concerned, of the wisdom of his policy. He now hoped that if his divisions remained on the borders of Bulgaria they would, in due time, link up with the armies of Yugoslavia.

The British were inclined to agree with him. The expedition was now ‘in its true setting, not as an isolated military act, but as a prime mover in a large design.’32 Eden and Dill, who had already reached Malta, hastened back to Athens, where they conferred first with Wilson and then with the Greek authorities. It was

decided that the Yugoslavs should be told that, if they moved into Bulgaria and Albania when the Germans entered Greece, the Allies would reinforce the defences along the Nestos River and the boundary of Bulgaria. At all costs they would protect the route up the Axios valley from Salonika into Yugoslavia.

At the end of March Dill paid a secret visit to Belgrade, but the Yugoslav leaders had no definite plans and no desire to take steps which might irritate Germany. The best that he could do was to arrange a conference at Kenali, near the border of Yugoslavia, between General Jankovitch, their Director of Operations, and Generals Papagos and Wilson. The Allied representatives went north from Athens on the night of 2–3 April so it was possible for General Freyberg to join the train and travel some distance with them.

That evening [2 April] I received a mysterious telegram to meet certain important people who were arriving by train at Katerini Station at 4.30 in the morning. To my surprise I met Mr Eden, General Dill, and General Wilson en route to Florina for a conference with the Yugoslav General Staff. I travelled up on the train with them as far as Aginion [Aiyinion] and heard the news and the plans which were in view. They were all in high spirits at the thought of Yugoslavia coming into the War and, as a result, various new plans seemed to be under consideration, including the possible advance of the British Forces north to the Rupel Pass. In the short time I had I did my best to put the case from our point of view. Although I did not like the Metaxas Line,33 it was a defensive position. With the help of Greek civilians we had improved the tank obstacle considerably and we had put out a great deal of wire. If we moved from this we might well be caught on the open plains without any defence against the German mechanised forces. Our only armoured force was the 1 Armoured Brigade whose original role was to delay the enemy to the maximum between the Axios and Aliakmon Rivers. I also hinted that we were not an Army – that so far we had only got the NZ Division in the forward area. On getting back to my HQ I wrote as follows in my diary concerning this new plan: ‘The situation is a grave one; we shall be fighting against heavy odds in a plan that has been ill-conceived and one that violates every principle of military strategy.’34

This was soon equally clear to the British commanders. They had gone forward to Edhessa and back through the mountains to Amindaion, through the Klidhi Pass and the defence posts of 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion to Florina, and beyond that again to a siding just south of the border of Yugoslavia. In the railcar that night, 3–4 April, they had their conference with General Jankovitch, who made the policy of Yugoslavia quite clear. If the Axis group attempted to take Salonika with the aim of encircling Yugoslavia from the south, Yugoslavia would resist and be prepared to co-operate with the Allied armies. She herself would

decide just when she would make that move, but she was quite willing to have plans prepared for any eventuality. In fact, Jankovitch had brought with him the draft plans by which she was willing to commit her divisions. Five British divisions were to go forward to the Lake Doiran area as a link between the army of Yugoslavia and the Greek forces along the Metaxas line. At the appropriate moment, which would be decided in Belgrade, the Allied forces were to open an offensive against the Italians in Albania and to the rear and right flank of the Germans advancing towards Salonika.

In the discussion which then developed the Allied representatives had to explain that such an ambitious plan was impossible. Moreover it was quite obvious that Jankovitch had not the authority to make any important decisions. The best they could do was to make suggestions and thereafter hope for the best. ‘General Papagos urged General J. to persuade his Government to send two more divisions into southern Serbia so as to ensure no break in the hinge joining the Allies; whilst I again stressed the importance of stopping a tank break through and of fighting on ground where the Yugoslav soldier would find himself superior to the German. At two o’clock in the morning General J. departed; opportunity for meeting him again never recurred. This closed the most unusual and at the same time the most unsatisfactory conference I have ever attended.’35

On the other hand, it was now quite clear that there had been a tendency to overestimate the contribution which Yugoslavia could make to the Allied cause. Her leaders apparently thought that they could make decisions in their own good time, ‘whereas it was most likely the Germans would make them for them.’36 And, even more important, her army as a fighting unit was now of very doubtful quality.

This hesitancy on the part of Yugoslavia placed Wilson and Papagos in a very difficult position so on 4 April, during the train journey from the conference, they discussed their problems. The former thought that the Germans might follow their favourite practice of attacking on the flanks, in which case there could be an encircling move from the east towards the Strumica River37 or possibly a thrust across south-east Yugoslavia which might end up as an advance into Greece through the Monastir Gap. First Armoured Brigade had therefore to be retained west of the Axios

River, ready to move forward or, if there was a threat from Monastir, to retire through the mountains to Amindaion.

In the opinion of General Papagos, however, the Monastir Gap was less important than the routes through the mountains into Macedonia and south towards Salonika. That from Bulgaria went through the Metaxas line by way of the Rupel Pass; that from Yugoslavia, the only supply line in the case of war, followed the valley of the Vardar (Axios) River. To control them he thought that several units from the Allied army should be moved forward from the Aliakmon line.

If the British resources had been greater and the support of Yugoslavia more certain this would have been a reasonable plan. But Wilson did not wish his troops to be caught on the move at this stage of the campaign; he preferred to remain where he was until the political situation was less obscure. So the final decision was that there should be no move beyond the Aliakmon line for at least eight days.

The Problems of W Force

Neither Blamey nor Freyberg seems to have been fully aware of the web within which the attitude of Yugoslavia had now enmeshed Wilson and Papagos. Anxious about their respective divisions, the Dominion commanders had long since wanted to move back from the plain to the mountains. On 20 March, for instance, after Wilson released 19 Greek Motorised Division from the central sector for an anti-parachute role in the Axios valley and the Doiran Gap, he had to inform Freyberg that his 6 Brigade, instead of filling the gap between 4 Brigade and 19 Greek Motorised Division, would have to take over the coastal sector from the Greeks. The warning order explained the position very bluntly: ‘As soon as you have got two Bdes up you must relieve 19 G Div and let them go. You may not like this but it can’t be helped. It is imperative that they be released for service NE.’38

General Freyberg thereupon pointed out that as he would have insufficient troops to hold this extended sector it could not be wise to have them on the plain to the north of Katerini. They would be better placed in the passes adjoining Mount Olympus. The Australian officers were of the same opinion. Lieutenant-Colonel H. Wells, the senior Australian liaison officer, who had already inspected the line, thought that it was not sound ‘to hold the open country north of Katerine, rather than the passes to the south.’ On 23 March Freyberg warned Blamey, who was then inspecting the line, that until reinforcements arrived about 4 April

he, Freyberg, had to hold a front of nearly 15 miles with only two infantry brigades, one field regiment of artillery and no anti-tank guns whatsoever. If 5 Brigade and 7 Anti-Tank Regiment did come through by that date his division would still be ‘too thin on the ground.’ Blamey’s opinion had then been that the New Zealand Division should be withdrawn from the plain to the foothills of Mount Olympus. In fact he had said that as soon as he became corps commander he would order such an adjustment to the Aliakmon line.39

On the strength of this statement General Freyberg had that same day explained the position to General Wilson. On his present front of 16,000 yards he had 4 Brigade. Given time and material he could, with 6 Brigade and normal fire support, make it reasonably secure. The more level sector along the coast which was held by 19 Greek Motorised Division was a totally different proposition. The retention of its 12,500 yards of front was a task for a complete division. Yet he understood that his three brigades, less the machine-gun companies at Amindaion, would have to take over both sectors. ‘Should this be so the enemy will have no difficulty in penetrating at any place where he chooses to concentrate. In my opinion at best a division on front of 28,500 yards is not a defensive position and it will only be able to delay enemy a matter of one or two days. I am of course not in the picture as regards general situation but if as I understand present line is to be held as a long term policy I suggest it is most unsound and that main position should be prepared and occupied covering mountain pass 14 miles south-west of Katerini. Present position could then be held by mobile troops.’40

The reply from W Force Headquarters on 24 March was that General Wilson ‘considers heavy attack on your front unlikely as compared one via Edessa.’ No additional troops41 were available but General Freyberg had to make certain that the enemy did not force the passes east and west of Mount Olympus. The Divisional Cavalry Regiment, when it arrived, ‘should more than compensate for departure of 19 Greek Div.’42

The same day General Blamey returned to Athens and discussed the subject with General Wilson. The following decisions were made:

The defence of the passes on the British front is of paramount importance. Work on these defences should be given priority. General Freyberg will be so informed by Brigadier Galloway. NZ Div Cav Regt will be

available very shortly to take over forward role and these are sufficient to relieve remainder of Div in advanced positions to allow the Div to prepare defences of Katerini (Olympus) Pass and pass between sea and Mt Olympus.43

In other words, the New Zealand Division was to remain behind the anti-tank ditch to the north of Katerini, but General Freyberg had, at the same time, to prepare demolitions and garrison the passes about Mount Olympus. He was warned44 that he must make certain of the passes on either side of Mount Olympus. ‘Everything you do in front must be subservient to that important factor, for if the passes are lost it would be awkward.’ Nineteenth Greek Motorised Division had to be released as early as possible. ‘The Greeks are counting on it, for what it is worth – in an anti-parachute role out in front of the plain. They may be of some use.’

The Aliakmon Line

The necessary operation orders45 were accordingly prepared. The battalions of 6 Brigade, having reached Katerini during 22–25 March, were free to take over the coastal sector from the Greeks: 24 Battalion went to the extreme right about Neon Elevtherokhorion and Skala Elevtherokhorion in the strip between the sea and the highway to Salonika; 25 Battalion went to the area about the church to Ayios Elias.46 The unit in reserve, 26 Battalion, was to have been at Koukos, near Katerini, but the task of preparing the defences of the passes, as well as those of the Aliakmon line, forced Divisional Headquarters to send D Company to the Platamon tunnel area47 and the rest of the unit to the Mount Olympus area.

In the sector on the left flank which had been the responsibility of 4 Brigade for the past two weeks, 18 Battalion now held the ridges about the villages of Paliostani and Mikri Milia and 20 Battalion was to its left about Radhani. D Company 19 Battalion was at the entrance to Olympus Pass but the battalion as a whole had been in reserve along the Chaknakhora ridge. Like 26 Battalion in the coastal sector, it was now withdrawn and employed about the eastern approaches to the pass during the period 28 March– 1 April.

The divided interest of the two brigades – along the Aliakmon line and about Olympus Pass – was not the only unusual feature of the defence system. The 15-mile front was so exceptionally

wide that areas which would normally have been allocated to battalions were held by single companies sited on spurs or high ground and prepared for all-round defence. There was still an undefended gap of some 5500 yards between the western boundary of 4 Brigade and the mountain sector held by 12 Greek Division. Wire and sandbags were available for 4 Brigade, but 6 Brigade had to make the best use it could of any material left behind by 12 Greek Division. In fact the only strong point appeared to be the deep anti-tank ditch that was being cut from the coast north of Skala Elevtherokhorion to the Toponitsa River and thence to the source of the shallow stream in the area north-west of Paliostani.

In the area behind the line there were equally serious problems arising from limited time and inadequate resources. The different companies of engineers had not only to improve the system of communications but they had also to assist in the preparation of defensive positions. No. 1 Section 6 Field Company had therefore been brought forward from Olympus Pass to the 4 Brigade area, and Nos. 2 and 3 from the north of Katerini to the 6 Brigade area. Nineteenth Army Troops Company had No. 3 Section48 on the western side of Mount Olympus preparing W Force Headquarters at Tsaritsani; No. 2 was completing work begun by 6 Field Company at the crest of the pass; and No. 1 was improving the roads in the Gannokhora area. Fifth Field Park Company was erecting trestle bridges and handling the explosives and stores arriving at Larisa and Katerini. Seventh Field Company reached Katerini on 7 April, just before the divisional withdrawal but not in time to do any work in the forward areas.

So far as possible the engineers, and not the infantry, did the more specialised work along the front. Demolition charges were laid on the bridges, railway embankments and anti-tank crossing in the 6 Brigade area. The allocation of mines and the selection of sites for them are mentioned in official instructions but there is no record of their having been laid in any area. With the anti-tank ditch there was more progress. The Greek plans for a continuous line across the front had to be dropped but every effort was made to complete a series of defended localities. The only trouble was that the half-completed positions were not always suitable for all-round defence. The battalions had therefore to dig, wire and camouflage positions; the engineers had to construct a concrete pillbox in each company area. The local Greeks gave

what assistance they could, the old men, the women and the boys doing the work of those who were away on active service. Clifton noted: ‘Still some difficulty getting Greek engineers properly functioning on our line of thought regarding defences and pill boxes. They are sound and their 4000 labourers going well, but language is a serious difficulty.’ This was better appreciated by Captain Carrie,49 of the New Zealand Engineers, who had to pay the labourers. On pay-days he would depart ‘dazed and almost crazy leaving behind a mutinous and vociferous crowd whose names had somehow been left off the rolls altogether and who were now adopting a menacing attitude towards the by now demented and almost speechless Union officials.’

At the same time the CRA, Brigadier Miles, and his Brigade Major, Major R. C. Queree, had been preparing for the arrival of the Divisional Artillery. As the extended front, particularly on the left flank, made it impossible for the infantry to hold a complete line, the German advance would have to be checked by artillery fire and counter-attack. The gun positions had therefore to be in places which the enemy could not observe either from his own territory or from the gaps between the defended localities. This necessity, together with the south-easterly slope of the ridges, the steep gullies and the lack of tracks connecting them made the selection of positions difficult, but, in the end, these requirements were met, at the expense, however, of anti-tank fields of fire. No serious consequences came from this decision, but events were soon to show that too much reliance had been placed on the supposedly anti-tank nature of the country.

It was decided that 6 Brigade, astride the main highway, should be covered by 4 and 5 Field Regiments (less E Troop) and that 4 Brigade should be supported by 6 Field Regiment. Fourth Field Regiment, which had reached Katerini on 26 March, was in position by 30 March with its guns covering the front from the coast to Katakhas. Fifth Field Regiment, arriving on 31 March, sent E Troop 26 Battery to the Aliakmon River on 2 April and moved to the rear of 6 Brigade on 4 April. Sixth Field Regiment reached Katerini on 1 April and was in support of 4 Brigade by 5 April. By then 1 Survey Troop was making a minor triangulation of the front and Headquarters Divisional Artillery had been established in the village of Kalokhori.

There were no anti-tank guns until 7 Anti-Tank Regiment arrived at Katerini on 2 April. As the most suitable route for enemy tanks was along the main road and railway, 32 and 33 Batteries, with B Troop from 31 Battery under command, were

allocated to 6 Brigade, whose sector included these avenues of approach. The great difficulty was the shortage of men and guns. Battalion commanders were inclined to expect anti-tank gunners to cover gaps in the infantry positions; the gunners complained that obvious anti-tank positions had to be left unoccupied because no infantry support was possible. Another problem was the actual siting of the guns. The fashionable theory brought out from Britain by the gunners was that the tanks should be knocked out after they had penetrated the infantry positions. The infantry commanders naturally preferred that the tanks should be halted as they approached their defences. In the end three guns were placed well forward to cover the crossings over the anti-tank ditch and the others sited behind the main ridge. As 4 Brigade occupied an area that was less suitable for tanks, only 31 Battery, less the troop with 6 Brigade, came under its command. The eight guns were then placed under the command of the battalions and incorporated in their defence plans.50

The only other supporting weapons were those of 3 and 4 Companies 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion which had reached Katerini on 27 March. The former, under the command of 6 Brigade, now had platoons with the flank battalions to act in a ‘counter penetration’ role. The latter with similar instructions was in the 22 Battalion area along the ridge to the south of Tranos.

The field ambulance with each brigade provided advanced and main dressing stations. Thus 4 Field Ambulance, which was in the rough country with 4 Brigade, had its ADS in dugouts cut into the hillsides and its MDS 13 miles away at Kalokhori. The medical cases from 6 Brigade had at first been the responsibility of an MDS set up near this village by 5 Field Ambulance, but after 30 March 6 Field Ambulance had two ADSs behind the brigade lines, one at Sfendhami dug in and camouflaged, and the other at Koukos in the shelter of a stone shed. The MDS was well back near Kato Melia and among the oak trees at the foot of Olympus Pass.

At this stage of the war there was ‘a very general opinion that the German Army would not respect the Red Cross if displayed by our medical units. It ... led to unnecessary difficulties in the forward medical units. Partly because of this, the forward ADSs and MDSs were placed in positions chosen for their obscurity and camouflage value and the possibility of sinking the tent floors below ground level. There were no large Red Crosses displayed on the roofs of ambulances. As a result medical units were subjected to bombing and machine-gunning from the air. As the short

campaign proceeded it was learnt that the Germans did respect the Red Cross.’51

The structure of the divisional defence system was now complete. No additional troops were ever brought forward but some slight changes were made on 2 April after General Freyberg had discussed the arrangements with the commanders of 4 and 6 Brigades. Divisional Headquarters was moved from Katerini to Ay Ioannis to form a battle headquarters. The boundary between the brigades was shifted westwards, giving 6 Brigade a wider frontage and making it necessary to have three battalions in the line. Twenty-sixth Battalion, now released from the Divisional Reserve because of the arrival of 5 Brigade, was therefore sent forward between 24 and 25 Battalions. In the 4 Brigade sector the only change was the return of 19 Battalion from the Mount Olympus area; as brigade reserve it could now be used for counter-attack without the consent of Divisional Headquarters.

The Divisional Reserve in the Tranos area was still of limited strength. Twenty-second Battalion, with 4 Company 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion under command, was deployed along the ridge, while Headquarters 7 Anti-Tank Regiment with 34 Battery (less O Troop) covered the anti-tank obstacles between Pal Elevtherokhorion and Sfendhami.

Divisional Cavalry Regiment Along the Aliakmon River

Nearly 15 miles north of the anti-tank ditch was the muddy Aliakmon River with its coastal swamp and high stopbanks. As the road and railway bridges in the stretch between Megali Yefira and Karavi were particularly important, the Divisional Cavalry Regiment, when it arrived at Katerini, was ordered to that area. After resisting as long as possible any attempts to make a crossing, the squadrons would fight a series of delaying actions and eventually withdraw through the main defences. On 1 April the regiment moved to the river, A Squadron taking the eastern section, B Squadron going to the west and Advanced Regimental Headquarters, with C Squadron as reserve, occupying the area about the village of Paliambela. Efforts were then made to improve the roads and the armoured cars were dug into the river bank until there was just sufficient clearance for the Vickers machine guns. On the escarpments to the south, observation points were established to overlook the approaches from Salonika, the plain of Macedonia to the north and the gorge near Veroia from which the river left the western mountains.

To assist the regiment in its delaying role two troops of artillery were sent up. E Troop 28 Battery 5 Field Regiment (Captain Bevan52), which arrived with its four 25-pounders on 2 April, had to prepare to shell the crossroads at Yidha, the road south to the bridge and any enemy formations that attempted to cross the river. O Troop 34 Battery 7 Anti-Tank Regiment (Lieutenant Patterson53) came up on 3 April and was placed under command of A Squadron. Two of its two-pounders, each supported by an armoured car, covered the main road bridge; the other two, with similar support, covered the railway bridge.

No. 3 Section 6 Field Company was responsible for the demolitions in the area, particularly those on the bridges across the Aliakmon River. The charges were not, however, to be placed in position until orders had been received from Divisional Headquarters.

On 4 April there was one change in the strength of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment. First Armoured Brigade on the Macedonian Plain was seriously handicapped by a shortage of reconnaissance vehicles so, in exchange for seven cruiser tanks, two troops of Marmon Harrington armoured cars were sent over under the command of Lieutenant Atchison54 and Second-Lieutenant Cole.55 In their new role they were to be the first New Zealand units in action in Greece.56

The Olympus Pass Defences

At the same time new positions were being prepared about Mount Olympus. In the pass itself two companies from 18 Battalion had started work immediately after the arrival of 4 Brigade. One had soon returned to its unit but the other had remained until 22 March, when it was relieved by a company from 19 Battalion. After 25 March, when General Freyberg was warned that he must prepare for the withdrawal to the mountains, much greater effort had to be made so the reserve battalions of 4 and 6 Brigades were employed about the pass until 5 Brigade arrived from Athens.

Nineteenth Battalion was brought back on 28 March to the north side of the pass; a guard was placed on that rocky feature called Gibraltar; and positions were prepared on the north bank of the Mavroneri River. Twenty-sixth Battalion, which had moved to the reserve area for 6 Brigade on 27 March, received its orders and

was back that night at the Petras Sanatorium on the south side of the pass. The next two days were spent making a road suitable for motor traffic from the Sanatorium southwards to Ravani. After the campaign Brigadier Hargest when describing the tracks of the area said, ‘one built mainly by 26th Bn was an especially fine piece of work, going from the road straight up a mountain side for hundreds of feet – it was completed in a short day and allowed eight guns to fire from a totally unsuspected spot straight down the enemy’s line of approach.’57

The orders for 5 Brigade had already been issued. It had to prepare and occupy defensive positions astride the pass on Mount Olympus, which would be held in strength; the coastal route by way of the Platamon tunnel would be held by one company, though preparations would be made for a battalion ‘should circumstances require it.’

The first unit to arrive was 23 Battalion, which moved into the Sanatorium area on 31 March, thereby making it possible for 26 Battalion to return to the 6 Brigade sector. The following day 28 (Maori) Battalion went to the north side of the pass and 19 Battalion returned to 4 Brigade. The other units of 5 Brigade were not as yet sent to the pass. On 1 April 22 Battalion58 had gone to Tranos, where it was under command of 6 Brigade and part of Divisional Reserve. Twenty-first Battalion59 was still in the Athens–Piræus area under the command of 80 Base Sub-area.

The defences were along the eastern slopes of Mount Olympus, with dense undergrowth on the lower level and an oak-beech forest above. Twenty-third Battalion held the right flank; 22 Battalion, when it returned, was to hold the pass and 28 (Maori) Battalion the left or northern flank. As the front of some eight to nine miles was too wide for the number of men available, the system of defence had to be similar to that adopted by the other brigades: ‘Our sub-sectors will be held by pl or even coy localities and sited on spurs and high ground. Localities will be prepared for all round defence. All posts will be dug in and wired.’60

Twenty-three Battalion occupied a ridge that ran almost parallel to the main range. D Company, somewhat isolated on the extreme right, covered the approaches from the east; C Company had the section which included Lokova, a village on the foothills; A and B Companies were strung out along the ridge towards the buildings of the Sanatorium. To an artist these posts would have been enchanting; to the thoughtful soldier the broken country, the

undergrowth and the wide front immediately suggested infiltration. Nevertheless the scenery was impressive, for the battalion from the clearings amidst the oak trees overlooked ridges cloaked with saplings and dense undergrowth, a belt of scrub and the plain with its many villages. Above it loomed Mount Olympus, looking like some peak in the Southern Alps when seen from a beach on the West Coast. From Larisa it had been an unimpressive rounded mass but from the Macedonian side it was, without question, the abode of the Gods.

The Aliakmon line. The New Zealand Division’s early positions in Greece, 5 April 1941

There were admittedly some unpleasant hours of mist and rain, but it was springtime and the woods were ‘carpeted with vast banks of polyanthus, primroses, hyacinths and violets’;61 the newly cut tracks were often greasy and requiring attention, but the life was invigorating and the men were fit. They had to site section posts, cut fields of fire and erect wire through the undergrowth. ‘Rarely, if ever again, did the battalion take such pains over a defensive position.’62

The greatest problem was that of communications. The only vehicle access from the main highway was by the road to the Sanatorium which 26 Battalion had extended along the ridge. The junction, however, being at a lower level, was too far forward of the positions for the route to be a safe supply line. It was therefore decided that a serviceable track must be cut round the shoulder of Mount Olympus and south-west to Kokkinoplos, a village from which a rough but passable road went down to the Kozani–Larisa highway. On 6 April Major Hart63 and 200 men from 22 Battalion came over to begin the work. Soon afterwards when the situation in the Balkans deteriorated and there was every possibility of withdrawal, the track became even more important. The battalion could reach the main highway only by moving across its front to the mouth of the pass where, with others also on the move, there would inevitably be congestion and delay. Engineers were therefore called in to make the track capable of carrying gun tractors over the ridges to Kokkinoplos.

Until 22 Battalion was released from the Divisional Reserve, the defence of the entrance of the pass was the responsibility of B Company 28 (Maori) Battalion. At first the Maoris had one platoon south of the highway ‘on the Gibraltar outcrop’ and the others north of it. Later the whole company went forward another 1000 yards to cover the junction of the highway and the road to 23 Battalion.

The other Maori companies held the left flank or northern side of the pass, first A Company, then C Company behind the village of Kariai and D Company still farther north overlooking Haduladhika. If all went well, the line was to be extended still farther north to link up with 16 Australian Brigade in the Veroia Pass area.

The Maoris hastened to prepare their positions among the heavily wooded spurs half parallel to the main range. They had a clear view of the highway, but the foreground was thick with bracken and wild pears and cut by many high-banked streams. In

such country a determined enemy would inevitably adopt a policy of infiltration which would be very difficult to resist. As it was, the Maoris had serious problems of communication and had attempted to cut foot tracks through the dense undergrowth. But up to date all weapons, ammunition, wire and rations had been packed through to the outlying platoons. In fact the simplest way to reach C and D Companies was to go six miles forward from the pass and then turn north-west and so back to Kariai and Haduladhika. If the battalion had to withdraw it would be quite impossible to move south across the front to the main highway. The only possible line of retreat was up the Mavroneri creek and over the timbered ridges to join the road near the crest of the pass.

The other units of the brigade group were not so widely dispersed. All B Echelon transport was assembled forward of the pass at Kato Melia. Fifth Field Ambulance, which had moved north with the brigade, had established a Main Dressing Station near Dholikhi, on the western side of the pass, for the use of New Zealand units working in that area. In the event of hostilities the casualties from the brigade would be brought back up the pass road and through the Advanced Dressing Station which had been established between the crest and Ay Dhimitrios.

No guns were yet in the area, for all regiments were needed behind 4 and 6 Brigades. The best that Brigadiers Miles and Hargest could do was to select positions and arrange for the construction of the necessary roads and tracks.

The engineers, however, were able to give more attention to the pass. The sections of 6 Field Company had been called forward to the Aliakmon line, but after 24 March their work at Ay Dhimitrios was continued by No. 2 Section 19 Army Troops Company. The main demolition was initially prepared in the narrow gorge below the village, with a sapper permanently on guard to protect it from enemy or fifth-column interference and, if necessary, to explode it on orders from the officer in command of the covering party. That officer had very definite instructions:

He will receive his orders either in writing signed by Div Comd or verbally from a senior staff officer who will be in possession of written orders from Div Comd. The OC covering party will satisfy himself that these written orders are genuine. Under no circumstances whatever will OC Covering Party fire the charge.

After 5 Brigade took over, the demolition was shifted to the area held in the first stages by 28 (Maori) Battalion. Other demolitions were prepared on the bridges covering the approaches to the pass and three additional charges were placed on the main

highway at points selected by Brigadier Hargest and the CRE, Lieutenant-Colonel Clifton.

The Coastal Route and the Platamon Tunnel

The pass to the east of Mount Olympus was more complex in character. It began as the Pinios Gorge separating Mounts Ossa and Olympus, continued north as a narrow coastal strip, and ended as a steep ridge flanking Mount Olympus and ending in great cliffs above the sea. Access to the plain beyond depended upon the railway tunnel at Platamon and a rough track across the ridge. In the opinion of the intelligence officer who prepared a report upon the area, 8-cwt trucks could be taken over but for heavier vehicles there would have to be considerable improvement. If there were demolitions in the tunnel and in the narrower parts of the gorge, the ‘eastern pass’ could be held by one battalion.

On 27 March D Company 26 Battalion was, accordingly, instructed to move by train from Katerini to the Platamon area and there prepare positions to meet an attack from the north. The Divisional Engineers would provide 1000 yards of wire and make preparations to demolish the tunnel ‘when emergency occurs’. The company, under the command of Captain Huggins,64 arrived that night, detrained at the miniature railway station and next morning went up the tracks to the crest of the ridge.

At the seaward end was a castle,65 farther up the ridge a small hillock, Point 266, and beyond that the village of Pandeleimon and the lower slopes of Mount Olympus. The company’s first task was the preparation of a post about the castle, but after Colonel Stewart inspected the area on 30 March he ordered the construction of positions for a whole battalion. There would be a post at the castle, another one would cover it from the rear, and the line would be extended up the ridge beyond Point 266.

‘The men were impressed with the urgency and importance of the job and worked very intelligently and with a will throughout.’66 On 4 April General Freyberg with Brigadier Hargest and Colonel Stewart visited the area and ‘expressed satisfaction with what had been done. ...’67 The General stated that if a battalion took over it would be expected to hold for only twenty-four hours: by then reinforcements would have been sent up from Larisa.

The demolitions in the tunnel were the responsibility of the CRE. The orders for firing them were just as carefully worded as those for 5 Brigade in Olympus Pass, but because of the isolation of the sector the senior officer or NCO on the spot could, in face of serious enemy attack, fire the charges without his having received written authority to do so.

Units Continue to Arrive

Throughout this period the remaining units of the Division were steadily coming up from Athens, but the order of their arrival had not been intelligently planned by those who had arranged the embarkation. The Divisional Postal Section, for instance, had an office at Hymettus Camp by 15 March, another at Voula by 20 March and one at Katerini by 24 March. As early as 21 March the Divisional Provost Section was at Kalokhori and the Field Punishment Centre at Katerini. The Headquarters staff, on the other hand, owing to their late departure from Egypt and to the delays of the storm period, made a very late arrival. ‘For fifteen days I had only two Staff officers in Greece, my GSO I and AA & QMG, who had travelled across with me.’68

Divisional Signals arrived at Katerini on 25 March; until then there had been no signals office at Divisional Headquarters. J Section which had travelled with 4 Brigade had, however, established communication with Athens by the civil lines and requisitioned the line between Palionellini and Katerini. K Section with 5 Brigade had built up a system in the Mount Olympus area. And now with the assistance of W Force Signals it was possible to complete the divisional signals system before the invasion of Greece.

As there was always the possibility of the civil lines being tapped, the Field Security Section, after its appearance on 27 March, checked civilians and watched for any fifth-column activities. In all calls to Athens a high-grade cipher was used and, for messages within the area, there were twenty-seven typewritten pages of codenames for units, places, equipment and supplies. Some interruptions were due to breaks within the cable ‘plainly made by pounding the wire between two stones.’ Others were due to the needs of the local peasantry. One shepherd by tethering his bell wether with a length of cable caused a full-scale field security spy hunt. The wireless sets, apart from some test exercises, were not used for there had to be complete wireless silence until operations began. Consequently, the Divisional Cavalry Regiment when it was sent forward to the Aliakmon River used its No. 11 sets for nothing other than daily test calls.

The units of the New Zealand Army Service Corps were about Katerini before and after the arrival of Divisional Headquarters. Until 25 March the troops had dry rations, but once Headquarters New Zealand Army Service Corps arrived at Kalokhori69 a Greek officer assisted the Requisitioning Officer to purchase fresh rations, and thereafter New Zealand vehicles brought bread from Athens, vegetables from Salonika and meat from both cities. The responsibility of drawing these supplies and building up reserve dumps of dry rations was left to the front-line transport of all units except 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion at Amindaion, which was supplied by the Divisional Supply Column. If the units were east of Mount Olympus they went to No. 4 Field Supply Depot at Neon Keramidhi; if they were on the Larisa side they went to No. 1 Field Supply Depot on the plain below the western entrance of Olympus Pass. This left the Supply Column free to establish itself at Neon Keramidhi and bring in supplies from both Katerini and Larisa.

The Army Service Corps units were, for the most part, on the Larisa side of the mountain. The Ammunition Company had reached Katerini on 25 March and had then taken ammunition from the railhead to the forward areas, but after 3 April it operated from Larisa, attached to 81 Base Sub-area and running convoys to Servia and Amindaion. The Petrol Company worked in Athens during 21–25 March, reached a base just north of Elasson on 29 March and thereafter trucked petrol from Larisa. Fourth Reserve Mechanical Transport Company, after spending 21–27 March about Athens and Piræus, went to the Larisa area, where it encamped at Nikaia, attached to 81 Base Sub-area. From there dumps were established about Larisa, supplies were taken to Servia and Kozani, and, on 4–7 April, Greek troops were transported from Veroia to Edhessa.

The servicing of divisional transport was done by 1 Field Workshops from a point six miles west of Katerini; Ordnance duties were the responsibility of Major Andrews,70 Assistant Director of Ordnance Services, who had opened his office at Kalokhori on 27 March.

The Chain of Medical Evacuation

The last day of March saw the medical service of the Division more or less complete with main and advanced dressing stations in each brigade area. First General Hospital (Colonel A. C. McKillop) which would normally have been a base institution had, on

instructions from Brigadier D. T. M. Large, Deputy Director of Medical Services, W Force, to be established along the line of communications. The Larisa area was malarious and the port of Volos was likely to be bombed, so the site eventually chosen was in a valley south of Pharsala and roughly halfway between Athens and the Aliakmon line. The hospital, with the Mobile Dental Unit (Major Mackenzie71) attached, moved in on 22 March; the first cases were received on 2 April; and two days later the New Zealand sisters arrived from Athens, where they had been billeted at Kifisia after their arrival on 27 March with the fifth flight.

The new site was charming. On the north side of the valley and alongside the small creek were the ruins of an old mill; at the head were groves of poplar trees and well turfed slopes already carpeted with spring flowers. In New Zealand it would have been classed as good sheep country; in fact, bearded shepherds did wander about the hillsides to the amazement of the troops, who had never seen sheep and goats with bells on their necks or savage dogs whose chief virtue was their ability to protect a flock.

The Greek and Australian Divisions