Chapter 16: The Evacuation from Greece Begins

The Decision to Evacuate

IN the period of the withdrawal to Thermopylae the overall situation in the Middle East had been changing rapidly for the worse. Once the Germans had entered Belgrade on 13 April it had been clear to the authorities in Cairo that the Balkan front was about to collapse. Next day the New Zealand Government was told that because of the critical condition in Cyrenaica the Polish Brigade and 7 Australian Division could not be sent to Greece. Fearing the worst, it immediately suggested that preparations be made for the possible evacuation of W Force.

As it happened Wavell, when in Greece on 11–13 April, had warned1 Wilson that he must expect no reinforcements and had authorised de Guingand to discuss evacuation plans with certain responsible officers. This had been a wise precaution for Wavell, Cunningham and Longmore on 15 April were ‘forced to the conclusion that the only possible course was to withdraw the British troops from Greece.’2 They could not at this stage adopt or even mention this course of action. The suggestion had to come from the Greek Government.

The following day General Papagos made the first move when he suggested3 to General Wilson that W Force should be withdrawn. This brought matters to a head. Wilson informed Middle East Headquarters and on 17 April Rear-Admiral H. T. Baillie-Grohman was sent to Greece to prepare for the evacuation. In Athens a Joint Planning Staff was formed and reconnaissance parties were sent to report on the more suitable beaches.

When informed of the Greek proposal Mr Churchill on 17 April had replied:

We cannot remain in Greece against wish of Greek Commander-in-Chief, and thus expose country to devastation. Wilson or Palairet should obtain endorsement by Greek Government of Papagos’s request. Consequent upon this assent, evacuation should proceed, without however prejudicing any

withdrawal to Thermopylae position in co-operation with the Greek Army. You will naturally try to save as much material as possible.4

In Athens the situation was fast approaching a crisis. An unofficial order to the army in Albania had given certain troops Easter leave and they were now in the city ‘bewildered and angry.’5 There was a suggestion that the King and his Government should depart for Crete. And on 18 April M. Koryzis committed suicide ‘after telling the King that he felt that he had failed him in the task entrusted to him.’6

At the same time General Wilson, owing to the frequent changes in location of his headquarters and the unreliability of the wireless communications in the mountains, was not always able to supply the information required by the authorities in both Cairo and London. ‘For this I was taken severely to task by our Prime Minister, who often referred subsequently to this deficiency on my part.’7 Nor could he always be definite. On 18 April Wilson first stated that his force could fight on for another month and then doubted if his units would be in position to hold the Thermopylae line.

The problems of Air Chief Marshal Longmore were just as formidable; his resources were quite inadequate for the demands now being made upon them. So that day in London, as a result of his request for guidance, the relative importance of the many problems of the Middle East was at last clearly stated. In a directive sent by Mr Churchill and endorsed by the Chiefs of Staff the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East were advised that, though the future of W Force affected the whole Empire, ‘victory in Libya counts first, evacuation of troops from Greece second.’ Shipping to Tobruk, unless indispensable to victory, had to be supplied when convenient; Iraq could be ‘ignored and Crete ... worked up later.’8

Evacuation now seemed inevitable but there was as yet no suggestion of haste. Wavell advised Wilson that if W Force could itself securely hold the Thermopylae line there was no reason to hasten the evacuation. Unless the political situation forced an early withdrawal the line should be held for some time and the enemy forced to fight. Attention could then be given to the work in Crete, the defence of Egypt could be strengthened and the evacuation plans could be prepared without too much haste.

Nevertheless, much organisation was necessary. Small craft had to be chartered and fitted out to ferry the troops from the beaches to the ships; to provide the beach parties the ship’s company from

the cruiser York abandoned its salvage work in Suda Bay; and the Navy, in spite of its responsibilities in the Mediterranean, had to adjust the movements of shipping according to the Army’s requirements.

Meanwhile in Athens General Wilson had attended a conference with the King, General Papagos, Sir Michael Palairet (British Minister), Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac, Rear-Admiral Turle and some members of the Greek Cabinet. They had discussed the military situation and whether it was advisable for the British to ‘hold on or evacuate’, the political situation and the defeatism that ‘was now getting widespread.’9

The results of this discussion were given to General Wavell, who arrived in Athens the next day, 19 April, and immediately conferred with General Wilson to consider the future action of W Force and to decide whether the British troops should or should not evacuate Greece. ‘The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible, were: the tying up of enemy forces, army and air, which would result therefrom; the strain the evacuation would place on the Navy and Merchant Marine; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred. In favour of withdrawal the arguments were: the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale.’10 Furthermore, the support of an army in Greece could so weaken the force in the Western Desert that its position could be precarious. Thus it was a case of sentiment versus facts, with instinct suggesting a fight to a finish and reason pointing out that the shortage of food and air cover were really the decisive factors. The decision was therefore made to withdraw from Greece. Evacuation would start on the night of 28–29 April and, with the destruction about Piræus harbour and the limitations of smaller ports, the general feeling was that the Navy would be fortunate if it ‘embarked 30% of the force.’11

The same day another conference was held at Tatoi Palace outside Athens. With no Prime Minister and no one willing to

assume that responsibility, the King was ‘now acting as head of his Government.’12 Those present included the group who attended the previous day together with General Wavell and General Mazarakis, a leader of the Venizelist Republican party, who had taken little part in public life after the dictatorship of Metaxas had been established in 1935.

The discussion was opened by General Wavell, who said that the British Army would fight as long as the Greek Army fought. However, if the Greek Government so desired it, the British forces would withdraw.13 Papagos then described the situation so far as the Greeks were concerned: the morale of the forces was weakening; the maintenance of both troops and refugees would soon be a serious problem. The British Minister followed with a message from Mr Churchill stating that if the British left Greece it must be with the consent of the Greek King and Government. After further discussion General Mazarakis decided that ‘he had been called in too late to retrieve the situation and that evacuation was the best solution.’14 This, the obvious conclusion, was accepted by all present. The actual decision was not officially made until the next day. A new government had to be formed and the King wanted some final statement about the morale of the Army of Epirus.

In London Mr Churchill was still confident:

I am increasingly of the opinion that if the generals on the spot think they can hold on in the Thermopylae position for a fortnight or three weeks, and can keep the Greek Army fighting, or enough of it, we should certainly support them, if the Dominions will agree. I do not believe the difficulty of evacuation will increase if the enemy suffers heavy losses. On the other hand, every day the German Air Force is detained in Greece enables the Libyan situation to be stabilised, and may enable us to bring in the extra tanks (to Tobruk). If this is accomplished safely and the Tobruk position holds, we might even feel strong enough to reinforce from Egypt. I am most reluctant to see us quit, and if the troops were British only and the matter could be decided on military grounds alone I would urge Wilson to fight if he thought it possible. Anyhow, before we commit ourselves to evacuation the case must be put squarely to the Dominions after to-morrow’s Cabinet. Of course, I do not know the conditions in which our retreating forces will reach the new key position.15

Unfortunately the situation in Greece no longer justified such determination. On 19 April the Germans, having forced the Pinios Gorge, were through Larisa and endeavouring to overtake the British columns along the roads to Volos and Lamia. The SS ‘Adolf Hitler’ Division had been diverted from Grevena and sent across

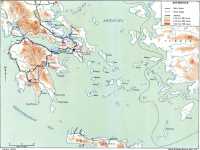

Southern Greece. Situation on 26 April 1941 after Germans Paratroop landings at Corinth

the Metsovon Pass in the direction of Ioannina to cover the flank of 12 Army and to isolate the Greeks on the western side of the Pindhos Mountains. The appearance of this force to the rear of the Army of Epirus and close to the Greek headquarters at Ioannina was decisive. With the support of two other corps commanders, General Tsolakoglou of 3 Army Corps (Western Macedonian Army) deposed the Army Commander and on 20 April opened the negotiations for an armistice. Next day at Larisa the terms were discussed and the treaty duly signed.16

Meanwhile, on the night of 20–21 April Wavell had driven north to Blamey’s headquarters in the Levadhia area and explained the situation.

He then returned to Athens, where on 21 April he met the King and his new Prime Minister, M. Tsouderos. The officer who had been sent to report on the conditions in Epirus had not yet returned, but the King admitted that there was no Greek force to protect the left flank of the British lines at Thermopylae. Wavell thereupon announced that he would have to attempt the evacuation of W Force. The King agreed, promising all possible support and generously apologising for the disaster. After the meeting the Greek premier, through Sir Michael Palairet, thanked the British Government and W Force for their efforts to help Greece. The Greek Army was now exhausted, and as conditions did not justify any further sacrifice W Force should, in the interests of the common cause, be immediately withdrawn.

The same day, 21 April, Wavell, in confirmation of verbal instructions, sent his written orders to Wilson. He was free to select the date for the beginning of the evacuation and he must take Generals Blamey and Freyberg fully into his confidence; the troops were to be taken either to Crete or to Egypt; close touch had to be kept with the Greek Government and so far as was possible any Greek personnel desired by the Greek Government should be embarked. The order also stated:

Should part of the original scheme fail or should portions of the force become cut off, they must not surrender but should endeavour to make their way into the Peloponnese or into any of the adjacent islands. It may well be possible to rescue parties from the Peloponnese at some considerably later date. You should bear in mind the possibility of later being able to evacuate transport, guns, etc., from the Southern Peloponnesian ports or beaches.

Almost immediately the plans had to be changed. News came through that day of the surrender of the Greek armies in Epirus. The western flank of the Thermopylae position was now wide

open; it was even possible that the Germans might cross the Gulf of Corinth to the Peloponnese. The German radio was already announcing that the British force in Greece was facing another Dunkirk. Wilson, after consultation with Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman, decided that the evacuation originally set for the night of 28–29 April must begin on 24–25 April, the earliest possible night. So, late on the night of 21 April, they met Blamey on the roadside near Thebes and told him that he would have to conduct the withdrawal. The detailed arrangements would be made by Headquarters W Force.

Medical and Base Units leave the Athens Area, 22–25 April

In Athens the King of Greece announced that the Government would leave for Crete and from there continue the war. The troops were told of the decision to evacuate Greece; movement orders were prepared; arrangements were made for the Greeks to have the supply depot and for the American Red Cross to take over the canteen stores; and the Military Attaché at Athens began to tour the Peloponnese to make plans for the Greeks to assist any British troops who might not be evacuated.

No time was wasted; in fact some of the New Zealand base units had already moved out. On 19 April 1 General Hospital17 had received its orders: the nurses would leave for Egypt in a hospital ship within a few hours; thirty orderlies must be sent to 26 General Hospital at Voula; and all the other male staff, less the five officers18 already at Voula, would leave Piræus that afternoon in the MV Rawnsley.

The vessel left that evening with some 600 British base troops and the medical group: Colonel McKillop, with 14 officers and 69 other ranks. But it missed the convoy and next morning, when standing by for instructions, was bombed and machine-gunned. The British had several casualties but they were transferred to the hospital ship Aba, and the Rawnsley carried on to reach Alexandria on 23 April.

The nurses, accompanied by Captains Sayers19 and King,20 took

much longer to leave Greece. No orders were received for the expected move on 19 April, but next day 1 officer and 32 nurses – of the fifty-two concerned – were sent to join the Aba, but it had already put out from Piræus to avoid the air attacks. The party returned to Kifisia and waited for further instructions.21

On the night of 21–22 April the New Zealand liaison officer at Headquarters British Troops in Greece, Athens, Major N. A. Rattray, had attended a conference with the naval staff and Brigadier Brunskill. The evacuation plan had been outlined and Rattray had been instructed to move the base units from Athens and the medical group from Voula. The officers of the Base Pay Office (Captain Morris22) and Advanced 2 Echelon (Second-Lieutenant Morton23) had been awakened just before midnight and given orders to join immediately the convoy which would be leaving that same night from the Reinforcement Camp at Voula, a village south-east along the coast from Piræus.

Shortly after midnight the authorities in the camp, Major MacDuff24 and his adjutant, Lieutenant Curtis,25 were given similar instructions by Major Rattray. Several groups were soon packing equipment and preparing to move out in half an hour’s time. Among them were the staff and patients of the temporary Convalescent Hospital, the Mobile Dental Unit encamped nearby, some members of the Divisional Postal Unit (Second-Lieutenant Harbott26), the Convalescent Hospital (Captain Slater27) and many convalescents recently discharged from the hospital to the reinforcement group.

The convoy left under the command of Captain Ritchie28 (Divisional Cavalry Regiment), whose instructions seem to have been very brief: move towards Corinth and the Peloponnese. This was simple enough once the highway was reached, for the main stream of traffic was now rattling westwards out of Athens. There was some confusion and an hour’s delay in the narrow streets of Elevsis, but at dawn the trucks were skirting the coast and approaching Megara. The convoy was then diverted by Movement

Control authorities into the olive groves to the east of the village; the troops took cover and the lorries were ordered back to Athens.

Here they waited for further orders from 80 Base Sub-Area and in peacetime would have remarked upon the sound of sheep bells and the enchanting countryside. On the outskirts of Megara the land sloped south to the minute coastal plain and north into a long valley thick with olive trees. The cemetery with its tall cypress trees was to the left, the dusty village faced south across fields red with poppies to the blue Mediterranean and the island of Salamis. To the west beyond the road above the cliffs there was the mass of the Peloponnese, range behind range, in a soft blue haze.

As it was, the Luftwaffe dominated the scene, patrolling the highway and making all movement by day extremely dangerous. That night, 22–23 April, a train came through from Athens with Australian troops, drafts of convalescents from the British hospitals and several New Zealanders, including the seven29 YMCA secretaries who had been working with the line-of-communication units and at the Base Reception Camp at Voula. Once again the Greek villagers offered eggs and brown bread – and once again the day was spent sheltering from observation aircraft and dive-bombers. But there were nearly 1200 men in the area, many of them convalcscents or walking wounded still needing attention. Captain Slater went back to Athens for medical supplies and three of the YMCA secretaries returned to Voula, where they salvaged chocolate, cigarettes, tinned milk and even clothing for those who had been hastily evacuated with little more than hospital pyjamas.

Each night there was an almost continuous stream of trucks moving through the village, but the expected orders for the New Zealand units never appeared. Finally, on the evening of 24–25 April Lieutenant H. M. Foreman30 (1 New Zealand General Hospital) was sent back to Athens for further orders. The ADMS, Greece, Colonel J. B. Fulton, RAMC, was amazed to hear of the situation; Movement Control, 80 Base Sub-area was equally surprised. Apparently the convoy should not have stopped at Megara but should have continued over the Corinth Canal to some embarkation point in the Peloponnese. Some seriously ill patients were returned to 26 General Hospital at Kifisia; the others had to

remain at Megara, Lieutenant-Colonel A. R. Barter, the senior officer at Megara, promising to arrange, if possible, for their embarkation on the night of 25–26 April.31

Another small detachment under Lieutenant Wilkinson32 was more fortunate. The convoy with the sick and wounded had set out for Voula, but at Daphni, just a few miles west of Athens, Wilkinson’s group had been ordered off the road by the military police who were restricting travel in daylight. The lorries had been taken back to Athens and the party left to its own devices for several anxious days before it was picked up by some New Zealand Divisional Postal Unit and Army Service Corps transport and taken to Navplion. From here they were taken off by HMAS Perth on the night of 26–27 April.33

Formation of the Reinforcement Battalion at Voula

At Voula there still remained the front-line reinforcements who had assembled there after the arrival of the different convoys or after the movement of the brigades to the Mount Olympus area. In March as many as fourteen different detachments from the camp had been scattered about the Athens– Piræus area as anti-aircraft gunners, mine spotters and guards for the many store and ammunition dumps. Some of this work had been taken over by 21 Battalion, but after that unit joined the Division on 6 April the guard duties were again the responsibility of the group. Once there was the chance of German landings two detachments of fifty were always on call to meet paratroop attacks, and after 17 April some eighty-five men under Captain Hutchison34 were on guard duties about the Hassani airfield. At the same time officers were often detailed for special duties. On 20 April, for example, Captain Baker35 and Second-Lieutenant Porter36 of the Maori Battalion were sent to Force Headquarters in Athens. There they were told that they were under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Barter, who was about to establish an evacuation point at Megara. They left immediately and were present when the New Zealand groups came in from Voula Camp.

After the Convalescent Hospital and attached units had made their sudden exodus on the night of 21–22 April there were four

days of intense activity and reorganisation. Including the detachments on guard about Athens, there were some 70 officers and 800 other ranks in the group. They came from thirty-one different units, had little fighting equipment and almost no transport. Trucks, Brens, machine guns and anti-tank rifles had to be ‘collected’ from the now loosely guarded ordnance depots. All this was done, with Captain Yates37 bringing order out of chaos and organising the men into companies: Headquarters Company, with engineer, anti-tank and machine-gun platoons, and four companies of infantry.

From the camp itself there was still some movement. An officer from the remnants38 of 21 Battalion, then outside Athens prior to its embarkation, appeared and the platoon organised from that unit’s reinforcements was allowed to join the main body and embark with 5 Brigade on the night of 24–25 April. Other men were detailed for duties outside Athens. Two small detachments under the command of Lieutenant Findlay39 and another subaltern were sent to guard the Khalkis bridge to Euboea Island, the plan at this stage being for a New Zealand brigade to embark40 from that area. Another detachment, with an Australian unit, went under the command of Second-Lieutenant Brickell41 to the Greek barracks in Athens and took the German prisoners captured at Servia to a transport in Piræus harbour.

The same day, 23 April, movement orders were received. The battalion became part of Force troops and was ordered to proceed to Navplion on the night of 25–26 April for embarkation from ‘T’ Beach on the night of 26–27 April. During daylight on 24 April Lieutenants Curtis and Spackman42 were sent to select assembly areas outside Navplion and after dark on the night of 25–26 April the battalion moved out, the guards from the wharves, dumps and airfield having come into camp or assembled along the highway to join the convoy.

The Evacuation Plans for W Force

The withdrawal of the divisions from the forward areas demanded more time and more carefully prepared timetables. Blamey had received his orders from Wavell on the night of 21–22 April, but Freyberg and Mackay were still preparing to hold the Thermopylae line. In the preamble to an operation order which was then being

prepared, Freyberg stated that ‘The Div. is fit to fight and again demonstrate its superiority over the enemy ... the present position is to be held and from it we shall not retire.’ Mackay afterwards said, ‘I thought that we’d hang on for about a fortnight and be beaten by weight of numbers.’43

The first warning to Freyberg was an order early on 22 April to halt the movement of a battalion to Khalkis and the Divisional Cavalry to Euboea. Then about 6 a.m. Lieutenant-Colonel Wells, senior Corps liaison officer, arrived from Anzac Corps Headquarters with a summary of the evacuation plan as it then stood. That night 4 Brigade and some supporting Australian units would go into position south of Thebes; each division would also withdraw a brigade group, which would wait under cover throughout 23 April, move back on the night of 23–24 April and embark from beaches east and west of Athens on the night of 24–25 April. The same night, 24–25 April, the balance of the force would leave the line, moving through Khalkis to Euboea Island to embark at some yet undecided date. Finally, on the night of 25–26 April the covering force south of Thebes would disengage; no details were yet available as to its place of embarkation.

The brigade commanders were immediately called to headquarters and given warning orders. Hargest was told that 5 Brigade, the forward formation, would be withdrawn from the line that night; Barrowclough learnt that 6 Brigade with all the artillery would remain at Thermopylae and Puttick was told that 4 Brigade, including 19 Battalion then on its way to Delphi, would be the rearguard holding the line south of Thebes.

That afternoon Blamey and his divisional commanders, Mackay and Freyberg, prepared their more detailed orders. The final plans for the withdrawal of W Force were not issued until next day, 23 April, but the main features had already been explained to them.

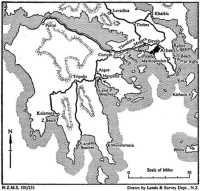

W Force had been organised as Anzac Corps, 80 Base Sub-area (Athens), 82 Base Sub-area (formed from 1 Armoured Brigade) and Force Troops from the Athens area directly under Wilson’s command: 4 Hussars, 3 Royal Tank Regiment and the Australian and New Zealand Reinforcement Battalions. To cover the withdrawal of these groups one New Zealand brigade44 would be sent south of Thebes to the ridge above Kriekouki. The original plan for embarking some units from Euboea had been abandoned and the collection and embarkation areas now were: Rafina (‘C’ Beach), Porto Rafti (‘D’ Beach), Megara (‘P’ Beach), Theodhora (‘J’ Beach), and Navplion (‘S’; and ‘T’ Beaches). The staffs for these

The Evacuation Beaches

areas, the beaches and the nights of embarkation for the different groups were then stated. On 24–25 April the units to embark would be 5 Brigade (‘C’ and ‘D’ Beaches), Headquarters Anzac Corps and one Australian brigade group (‘J’ Beach) and the Royal Air Force and some base details (‘S’ Beach); on 25–26 April 6 Brigade (‘C’ and ‘D’ Beaches), the other Australian brigade group and 82 Base Sub-area (‘P’ Beach); on 26–27 April 4 Brigade from ‘J’ Beach, Base Details, including Yugoslavs and W Force Headquarters (less Battle Headquarters), from ‘S’ and ‘T’ Beaches, the New Zealand Reinforcement Battalion from ‘T’ Beach, and 4 Hussars, 3 Royal Tank Regiment, the Australian Reinforcement Battalion and detachments of 82 Base Sub-area all from ‘S’ Beach.

The orders also gave detailed instructions about the method of withdrawal. The convoys would move by night and to ensure maximum practical speed side-lights could be used; towing was forbidden and all breakdowns were to be hauled aside and their passengers transferred to other vehicles. As the Greek authorities

were most insistent that no long-term damage be done to their railway system45 no major demolitions would be undertaken. In the beach areas, when motor transport would no longer be required, radiators and batteries had to be smashed and the engine casings broken with a sledgehammer. All implements and tyres had to be rendered unserviceable. No fires were to be lit and on no account whatsoever were oil and petrol to be destroyed by fire. Guns were to be rendered useless by the removal of the breech mechanism but all sights were to be brought away. Horses were to be shot; mules could be given to the Greeks. The troops were to leave with greatcoats, full equipment (less pack) and respirators. No other articles whatsoever were to be permitted in the lighters and the crews had to ensure that this order was obeyed.

In the Anzac Corps orders there were further details. Guns and technical vehicles not being used for troop-carrying were to be destroyed on the spot. The covering force would be 4 New Zealand Brigade with several Australian units under command: 2/3 Field Regiment, one anti-tank battery, 2/8 Field Company, one company 2/1 Machine Gun Battalion and one field ambulance. In the orders of Anzac Corps this brigade group was to be evacuated on the night of 25–26 April ‘unless otherwise ordered.’

With the New Zealand orders there were other variations. Fourth Brigade Group would embark on the night 25–26 April as stated in the orders from Corps, not on 26–27 April as suggested in W Force orders. Fifth Brigade Group which would, according to Force and Corps, withdraw to ‘C’ and ‘D’ beaches on the night 23–24 April and embark on the night 24–25 April, would withdraw on the night 22–23 April and embark from beaches east of Athens near Marathon on the night 23–24 April. With 6 Brigade there was another variation. According to both Force and Corps the battalions would embark on the night 25–26 April from the Rafina and Porto Rafti areas; in the divisional orders they would on the night 24–25 April withdraw from Thermopylae and embark from the Khalkis area.

The orders for the divisional rearguard were quite definite. The Divisional Cavalry Regiment, the carrier platoons of 5 Brigade and 34 Anti-Tank Battery, all under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Clifton, would cover the withdrawal of 6 Brigade from Thermopylae and then the withdrawal of 4 Brigade from Kriekouki.

But there were other irritating differences. The orders from W Force about equipment to be carried aboard ship were clearly stated yet those from New Zealand Division added gun sights,

rifles, Bren and anti-tank guns, ammunition, wireless sets and small attaché cases for officers. There was even some uncertainty about the routes to be followed. Corps had said that on the night of 24–25 April a New Zealand brigade should, if the road was passable, move south from the Khalkis area, and the New Zealand Division stated that the possible route to Athens was through either Khalkis or Elevsis. But on 23 April Corps just assumed that the Division would follow the coastal road from Khalkis.

The distances between the different headquarters, the broken communications and the constantly changing plans had been responsible for these conflicting orders. They were in most cases swiftly adjusted but there was nevertheless a certain amount of confusion. The beach officers, for example, followed Force orders and this led to fierce arguments when New Zealanders were asked to dump certain equipment on the embarkation beaches.

The Withdrawal from Thermopylae begins, Night 22–23 April

Next morning, 22 April, saw the enemy building up his strength. His heavy guns opened up from the east and south of Lamia; tanks were parked unconcealed; aircraft landed south-east of Imir Bei; and the long vehicle column continued to move in from Larisa.

At the same time there was the ever-increasing fear of German forces encircling either flank of Anzac Corps. No force had landed on Euboea but 1 Armoured Brigade was warned that a landing was imminent, perhaps that night. First Rangers, whose headquarters were at Ritsona, had to send a company to Khalkis and be prepared to demolish the bridge. Three Bren carriers with the three C Squadron New Zealand Divisional Cavalry armoured cars (Lieutenant Atchison) were sent to patrol the island but found no evidence of German landings.

On the extreme left the threat was more serious. The enemy were in Ioannina, and although they had not apparently reached Arta or Preveza the former town had been bombed heavily and was now in flames. To meet the expected attack demolitions were prepared in the Delphi Pass and the Greek headquarters sent infantry and anti-tank guns to come under British command and hold the approaches from Mesolongion to Amfissa. South of the Gulf of Corinth the Reserve Officers’ College Battalion was sent to Patrai with some field guns to check any landing party. And the coast from Corinth westwards to Patrai was assigned to 4 Hussars, which had been reorganised into three squadrons, each with two tanks and two Bren carriers.

The only sharp action during the day was on the Australian front. Two 25-pounders below Brallos Pass opened fire on German trucks

moving south towards the Sperkhios River. The enemy replied with medium artillery from the south-east of Lamia, field guns were brought forward to the river, and by midday the position was serious. The stores of shells and charges had been hit and were exploding; one gun was out of action; and the surrounding undergrowth was ablaze. In spite of these difficulties the artillerymen remained in position and did their best to harass some German infantry who were now debussing from trucks at the foot of the escarpment to the west of the road. The officer and his men ‘lifted the trail of the gun on to the edge of the pit so as to depress it enough to fire down the face of the hill and, using a weak charge lest the recoil should cause the gun to somersault, fired more than fifty rounds into the enemy infantry.’46 The Germans replied and, although half the crews were sent out with parts of the damaged gun, the Australian casualties, before the guns were abandoned in the late afternoon, were six killed and four wounded.

The New Zealand sector was comparatively quiet, apart from the ever recurring air raids and some artillery fire at night. The only casualty came with the last raid before nightfall when trucks moving forward for the withdrawal were attacked and one man killed. The night, 22–23 April, in the forward areas was equally undisturbed. The covering platoons from 22 and 23 Battalions were not attacked and the brigade Bren carriers which went forward to patrol the river bank were never challenged, except by the frogs whose croaking was greater than even Aristophanes could have imagined. To the rear, however, there was great activity. Fourth Brigade Group moved out first. Nineteenth Battalion,47 already in the Delphi area, had to be warned of the withdrawal but the other units, 1 Machine Gun Company, 4 Field Ambulance (less one company) and 18 and 20 Battalions, in the lorries of 4 RMT Company, moved back without any trouble to the Thebes area. Twenty-first Battalion, now 200 strong, handed over some twenty trucks to the other battalions of 5 Brigade, followed the 4 Brigade convoy and then carried on beyond Thebes to the Restos area near Athens.

The withdrawal of 5 Brigade from the left flank began about 9 p.m. The units – 22 and 28 (Maori) Battalions, 4 Machine Gun Company and finally 23 Battalion – moved to the highway and then marched three miles to embus, after which the convoy moved south to the Ay Konstandinos area, some 15 miles along the coast road.

After the convoys moved back A, B, C and F Troops of 6 Field Regiment withdrew to the west of Molos, leaving the forward

troops of 5 Field Regiment and 7 Anti-Tank Regiment in their anti-tank roles for another twenty-four hours.

To cover the gap which now existed between the left of 6 Brigade and the right flank of 6 Australian Division a covering force was left by 5 Brigade. Forward of the bridge were the Bren carriers from the battalions; south of the road in the 22 and 28 (Maori) Battalions’ areas were Major Hart, Second-Lieutenants Leeks48 and Carter49 and fifty-eight other ranks of 22 Battalion whose task it was to suggest that the line was still occupied. In the 23 Battalion area there were Captain Worsnop,50 Second-Lieutenants T. F. Begg and McPhail51 and two platoons to hold the demolished bridge.

Finally, to check any attempt to scramble through the high country on the western flank of 6 Brigade, 25 Battalion moved its C Company on to the ridge from which 22 Battalion had withdrawn. This feature was an effective tank obstacle, and if it could be held against infantry attacks the Germans would be forced to traverse the very rough country south of the road before they could encircle the defence line and block the withdrawal through Molos. If they did get round below the cliffs and came down the gully between Mendhenitsa and Molos in which Brigade Headquarters and several of the artillery units were established, the position would have been turned. However, this risk was taken and the platoons went into line facing the road at the end of the ridge with the carrier platoon in reserve. As events were soon to show, it would have been better had the flank of 25 Battalion been held in greater strength and much higher up the ridge.

The Front Weakens

On the following day, 23 April, the insecurity of the Brallos–Thermopylae position became more apparent. Away to the west in Epirus there had at first been no noticeable movement of the German forces, but that afternoon reports52 came in of hundreds of trucks moving south. As they could possibly reach Delphi within twenty-four hours, General Blamey saw to it that the road eastwards from Amfissa was blocked for motor traffic and that a small

force – an Australian battalion with a troop of artillery and a company of machine-gunners – was established just east of Levadhia to cover the demolitions in the road.

On the eastern flank there were now signs of German activity. The patrol from the New Zealand Divisional Cavalry Regiment, continuing its movement through the island of Euboea, found some eighty Australians and New Zealanders,53 once members of Allen Force, who were certain that the enemy was coming over from the mainland. Shortly afterwards several Germans were seen but no action took place and the patrol returned to the mainland. The great swing bridge at Khalkis was then to have been wrecked by a detachment from 7 Field Company, but before it arrived engineers from 1 Armoured Brigade destroyed the mechanism, leaving it wide open and impossible for the enemy to close. After that the channel coast was covered by C Company 1 Rangers.

The wrecking of the bridge had been due to a change in the plan of withdrawal. Divisional Headquarters had been advised that 6 Brigade would not move to Euboea but would withdraw to the beaches east of Athens for embarkation on the night of 26–27 April. There had also been a suggestion that the Division would retire to Athens by the northern route through Khalkis and Marathon and that the Divisional Cavalry Regiment should move back to support C Company 1 Rangers. However, General Freyberg considered that he needed the regiment as a rearguard; in any case, its vehicles were hastily being reconditioned after the long withdrawal from the Katerini area. So when Corps assumed that the Division would follow the coastal road, Freyberg rather frigidly informed General Blamey that he had already made plans for the Division to take the inland route through Thebes–Elevsis–Athens. The subsequent orders from Corps were for him to take such action as was then possible to cover the right flank and to support the Rangers. And later he did order the Divisional Cavalry Regiment to send one squadron to the Khalkis area to assist the 1 Armoured Brigade units should there be any landing from Euboea.

The day was also notable for the increased severity of the air attacks along the south coast. The columns of vehicles moving along the historic road between Elevsis and Corinth suffered heavy damage. Stukas damaged ships in Salamis Bay, and Dorniers when machine-gunning the road round the cliffs surprised a Greek mule transport column and just slaughtered the unfortunate animals. The Royal Air Force, now operating from the landing fields near Argos, had been reinforced with five Hurricanes from Crete, but that evening when the majority of the aircraft were on the ground thirty

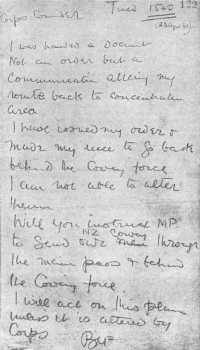

Draft of message from General Freyberg to General Blamey on 23 April 1941 on withdrawal route of the New Zealand Division from Thermopylae. Copied from General Staff Branch war diary, April 1941

to forty Me110s appeared over the area. The Bofors opened up but they were soon silenced. The Germans, almost unopposed, then destroyed one Hurricane in the air and thirteen on the ground. The remaining aircraft could not have covered the evacuation; the odds were too great. So that same day orders were issued for their withdrawal to Crete to defend Suda Bay and to assist No. 30 Squadron in protecting the convoys.

The Royal Air Force authorities then made54 their own arrangements for the evacuation of the ground staff. On 24 April over 2000 men were taken south by train and motor transport, several hundred to Yithion and the majority to Kalamata. From there it was thought that they could be taken, at night and in fishing vessels, to the island of Kithira and eventually to Crete.

With no air support from the mainland, Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman then decided that if the embarkations were to be kept secret the convoys must not approach the beaches until one hour after dark and that all ships must leave by 3 a.m. This would give them some chance of clearing the coast without being observed and of coming within the area covered during daylight by the fighters operating from Crete.

In the Thermopylae area the enemy, as on 22 April, awaited the arrival of reinforcements from Larisa and was satisfied with long-range shellfire and more active patrols. To check one active battery to the east of Imir Bei and out of range of 25-pounders, three guns of 64 Medium Regiment were brought up to the Molos area, but even then the aircraft landing near Imir Bei and the column of vehicles streaming into Lamia were well out of range. The best that could be done was to harass any movement of men and transport towards the river and the Alamanas bridge.

More direct action came about 4 p.m. when Germans on bicycles and motor-cycles rode up to the Sperkhios River and crossed the demolished bridge. To deal with this group the 23 Battalion detachment was ordered to send out patrols to the right and to the left of the bridge. But the platoon commanders, after receiving their orders, were unable to reach their sections because of the enemy’s steady machine-gun fire. Lieutenant McPhail thereupon set out to do alone what he had been ordered to accomplish with a patrol. Armed with a tommy gun, this determined officer went forward and shot two of ten Germans who were clambering over the bridge. On his way back he met two other Germans, one of whom he shot. After this resistance, and no doubt because of the harassing fire from 6 Field Regiment, there were no further attempts by the enemy to patrol beyond the river.

Withdrawals from the Thermopylae area, Night 23–24 April

When darkness fell over the Anzac area there began another series of withdrawals and adjustments. Fourth Brigade Group, which had been encamped in the Thebes area, moved the few miles south to the Kriekouki Pass and began to prepare the line which it would eventually have to hold as the rearguard of W Force.

In the Australian sector 19 Brigade withdrew to the Brallos area, leaving a two-company rearguard at the crest of the pass overlooking the highway to Lamia. Seventeenth Brigade came back from the rough country on the left flank and with 16 Brigade and Divisional Headquarters moved off in convoy towards the Megara area to await embarkation the following night. The column was eventually stopped near Elevsis, the units spending 24 April under cover in the olive groves.

In the New Zealand sector there was similar activity. Brigadier Barrowclough had decided that Hart Force and the guns in front of the spur immediately east of the baths at Thermopylae should all be withdrawn. After 9 p.m. the 23 Battalion detachment moved back to the old lines of 22 Battalion where the rest of Major Hart’s group was waiting. The men clambered aboard the Bren carriers and returned to Headquarters 6 Brigade, where it was expected that transport would be waiting to take them back to 5 Brigade. No lorries appeared so Hart Force remained with 6 Brigade, moving with it to southern Greece and eventually to Egypt. A and B Troops 5 Field Regiment were withdrawn without any difficulty, the first to the right flank behind Ay Trias, the second to the west of Molos. The anti-tank element, 33 Anti-Tank Battery and E Troop 31 Anti-Tank Battery, came out and went into position near Ay Trias and along the road between that village and Molos. This left E Troop 5 Field Regiment in an anti-tank role in front of two-pounder anti-tank guns, so next day, 24 April, four anti-tank guns from the Northumberland Hussars were brought forward.

To the rear of the FDLs there was corresponding activity. At Ay Konstandinos 5 Brigade had spent the day destroying equipment and preparing for the move that night to the embarkation beaches at Porto Rafti, some 150 miles away. Nothing was to interfere with the movement of the convoy: there would be no speed limit; headlights could be used beyond Livanatais; refugees could be moved aside; and, where the road was for one-way traffic only, oncoming vehicles could be stopped. To assist in the work at the control points on the beaches two officers from each battalion were sent forward to report at Headquarters British Troops in Greece in the Hotel Acropole in Athens.

The move began immediately after dark and the road was soon

filled with a steady stream of vehicles. Divisional Headquarters, less Battle Headquarters, had moved back during the afternoon to Atalandi, so it was probably first on the road through Thebes and over the hills to Athens and the lying-up areas near the eastern beaches. Behind it were 4 Field Hygiene Section and 6 Field Ambulance, all in the latter’s transport. These units, which had been sheltered in the olive groves of Livanatais, passed through Athens early next morning, 24 April, and the latter, when caught in the first air raid for the day, scattered throughout the olive groves and barley fields on the outskirts of the city. Fifth Field Ambulance, which had been established at Kammena Vourla, a delightful resort on the beaches south-east of Molos, also moved back, the forty-odd patients with the assistance of some Australian ambulance cars moving with the convoy to Athens and thence to 26 General Hospital at Kifisia. When the unit was safely in the lying-up area near the beaches the bulk of its equipment was sent to that same hospital.

The main body – 22 Battalion, 23 Battalion, 28 (Maori) Battalion, 19 Army Troops Company and 106 Anti-Aircraft Battery – came through in that order, moving swiftly and with very few mishaps. There was one break in the Maori Battalion column which encouraged an Australian convoy to take the road and led to some trucks following the Australians, but they were able to rejoin the unit for embarkation. Otherwise the convoys were rattling through Athens during the early morning of 24 April. The streets were still empty and windows were shuttered, all very different from the crowded city which had received the Division so excitedly only six weeks before. The troops, if they were awake, were disappointed, but those who went through later in the day soon learnt that the Greeks could remain loyal to an apparently hopeless cause.

East of Athens the convoy hastened for another 25 miles to what was called the Marathon area, and when the sun was rising the trucks were turning off for shelter under the pines or in the olive groves. The men remained under cover. Brigadier Hargest returned to Athens, visited Headquarters British Troops in Greece and saw to it that his troops could embark carrying packs and one blanket as well as their light weapons.

The many other units which had been on the road that night were equally successful. Twenty-first Battalion, which had been encamped at Restos near Athens, and its reinforcement group which had been at Voula Camp, both rejoined the brigade. Fifth Field Park Company and 7 Field Company (less the detachment with Clifton Force) moved to Mazi, south of Thebes, and there assisted

Australian engineers to prepare demolitions. Another convoy of 170 vehicles, mostly from the B Echelons of the Machine Gun Battalion and the Divisional Cavalry and artillery regiments, reached a valley south-east of Levadhia, where they spent the next day under cover of the olive trees.