Chapter 3: First Day of Battle: 20 May

Maleme and 22 Battalion

The dawn of Tuesday, 20 May, like many earlier dawns on Crete, gave back to the twisted olive trees their daytime grey and revealed beneath them men standing to their arms. As the light increased the noise from the company areas of cooks preparing breakfast grew louder, and the troops, the end of stand-to approaching, began to feel in their pockets for the cigarettes they would roll and soon be smoking. The air attacks that also came with the daylight seemed no more than an assurance that this day would pass like others. So at stand-down men merely grounded their weapons, lit their cigarettes, and sniffing the air from the company kitchens or cocking a wary eye upwards prepared circumspectly to join breakfast queues with their dixies. It would be another day of sunlight, of route marches with a swim at the end of them, of putting final patches to the defences, or of rehearsing company tactics on the olive-clad hillsides. There was scepticism enough for those who declared that today would be the day.

Nevertheless, it was the day. Already by half past seven the attack from the air was intense enough for those in the vital areas between Canea and Maleme to realise that something unusual was on the way. By eight o’clock there was no longer room for doubt. Swarms of enemy fighters and bombers were in the air, battering and bespattering the areas chosen for landing. More significant still, a sight new to all those who saw it but impossible to misinterpret, gliders came sweeping in towards Maleme, the Aghya reservoir, and Canea.

The cry of ‘Gliders!’ had hardly passed from mouth to mouth when the gliders themselves had circled swiftly in and disappeared from the view of all but those who overlooked their landing places, and who now, with no time to waste on wonder, looked down the sights of their weapons to see if a bullet fired had reached its mark or to fix the target for a second.

One portent succeeded another. Hard on the heels of the gliders came the Junkers 52 transports – some of them already hovering

hugely over the threatened areas and disdaining the small-arms fire that came crackling up at them, others coming straight in from the sea, ominous and purposeful. The whole air throbbed with them, and in and out among them snarled the fighters, strafing the ground so heavily that it was almost impossible to move except in short starts and rushes. And then, stranger even than the gliders, the air over Maleme and Galatas and in the Prison Valley was suddenly full of different-coloured parachutes, each supporting its man or its canister of weapons and supplies. In spite of all the innocent associations of such a display of colours – a ballroom at the height of the dance’s gaiety when the balloons are released from a balcony on the circling couples below – the sight was inexpressibly sinister. For each man dangling carried a death, his own if not another’s.

Even as they dropped they were within range and the crackle of rifle fire and Bren guns rose to a crescendo Wildly waving their legs, some already firing their Schmeissers, the parachutists came down, in the terraced vineyards, crashing through the peaceful olive boughs, in the yards of houses, on roofs, in the open fields where the short barley hid them. Many found graves where they found earth. Others, ridding themselves of their harness, crept cautiously in search of comrades, only to meet enemies. East of the airfield or in Galatas they were, more often than not, in the middle of the defenders and few were to escape. But where they landed out of range – as in the Aghya plain or west of the Tavronitis – there was the chance to collect more weapons and ammunition from the canisters, to organise in their sections, to attack. The day had indeed begun.

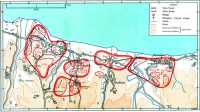

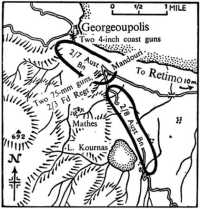

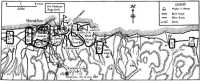

These were the enemy of the first wave, that attacking the sector from Canea to Maleme. Eleventh Air Corps had been divided into three groups: Group West to attack Maleme, Group Centre Canea, its environs, and Retimo; and Group East Heraklion. Retimo and Heraklion would be attacked by the second wave, not to land till the afternoon.

Group West’s ground forces consisted of the Assault Regiment1 (less half a battalion) and a company of the Parachute AA MG Battalion. The commander was General Meindl.2 the role was to seize Maleme airfield, to keep it open for airborne landings, to reconnoitre west as far as Kastelli, to reconnoitre south and east,

and to make contact with Group Centre, which was directed on Canea. To transport the force there were available four groups of transport aircraft and half a group of adapted bombers for the gliders.3

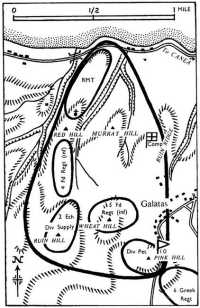

The plan of the enemy attack in the Maleme sector will be more clearly grasped if the units and their objectives are set out in tabular form:

| GLIDERS | ||

| Unit | Commander | Landing place and objective |

| Elements of HQ Assault Regt | Maj Braun | South of Tavronitis bridge |

| Elements of III Bn (9 gliders) | ||

| HQ I Bn 3 and 4 Coys (? 30 gliders) | Maj Koch | Mouth of Tavronitis (3 Coy) |

| Point 107 (HQ Bn and 4 Coy) | ||

| PARATROOPS | ||

| II Bn (5, 6, 7, 8 Coys) | Maj Stentzler | South of Kolimbari |

| Muerbe Detachment (72 men) | Lt Muerbe | 3 miles east of Kastelli |

| III Bn (9, 10, 11, 12 Coys) | Maj Scherber | East of Maleme airfield along road to Platanias |

| IV Bn | Capt Gericke | |

| 13 Coy (infantry guns) | West of Tavronitis bridge | |

| 14 Coy (A-tk guns) | West of Tavronitis bridge | |

| 15 Coy | West of Tavronitis bridge | |

|

16 Coy4 |

South-west of Point 107 | |

If the landing places tabulated are compared with the map it will be seen that the main weight of the Assault Regiment was to be so distributed round the airfield that a heavy converging attack could quickly be brought to bear. The plan also allowed for exploitation by the glider parties of their superior speed in coming into action. Thus Major Braun’s glider party, landing just south of the Tavronitis bridge, was to seize it and prevent its destruction. It would then be used to bring up the paratroops landed farther west. Similarly 3 Company of Major Koch’s party, landing at the Tavronitis mouth, was to destroy the AA positions there and thus ease the way for the transport aircraft. And 4 Company, if successful in taking Point 107, would have secured the feature which

The enemy must have seen from the first was the key to the whole position.

Since the paratroops would require more time and freedom to form up, their landing places were evidently intended to be far enough away from the defence to provide these conditions. II Battalion, south of Kolimbari, would be able to afford protection to the west until Meindl wanted them for the main attack on the airfield; and once they were involved in this, protection to the west would fall to Muerbe detachment.

Similarly IV Battalion, landing west of the Tavronitis and out of range to the main defences, would be quickly available to give artillery support for the main attack. Protection from the south would be provided by 16 Company, which was to move towards Palaiokhora as soon as it was safely landed.5

The enemy also assumed that the area east of the airfield would be as clear of defenders as that west of it proved to be. Thus by dropping III Battalion there he hoped that it would be able to form up without difficulty, send its main body to attack the airfield from the west, and send out other forces east to make contact with Group Centre.

Such, then, was the plan for Group West. The operation was to begin with the glider landings at 7.15 a.m. or by our time at a quarter past eight.6

The map of intended and actual landing areas will reveal the strength and the weaknesses of this plan. III Battalion, landing east of the airfield, was bound to get into trouble with 23 Battalion and the auxiliary detachments which, apparently unknown to enemy intelligence, were strong there. II and IV Battalions, landing well west of the Tavronitis, would find no opposition directly beneath them and would be able to form up with relatively little difficulty. The role of the glider troops of I Battalion was more hazardous. Success would depend partly on surprise, partly on the luck with which they landed initially – whether in view or not of 22 Battalion.

The enemy had, however, the advantage of one circumstance that must have been a blessing, partly unconvenanted. This was the condition of the AA defence on the airfield, which the plan reveals to have been the main objective.

The airfield was defended by the six mobile Bofors and the four static Bofors of 156 LAA Battery RA, and 7 LAA Battery RAA; and the two 3-inch AA guns of C HAA Battery, Royal Marines. The effective plan range of the Bofors did not exceed 800 yards, and to cover the area effectively they had to be sited close to the airfield. Complete concealment was impossible. Consequently the enemy had the gun sites plotted with reasonable accuracy and they were subjected to a heavy pounding for days beforehand. Moreover, although the lie of the land made it relatively easy for the guns to be so disposed that they could deal with air attacks coming in from the sea, they were inevitably very vulnerable to attacks made overland from the south and south-west. And it was from these quarters that attack usually came.

The two 3-inch guns were sited on a hill about 300 feet high and had difficulty in engaging aircraft which flew in at heights of from 300 to 600 feet – a task for which guns of this calibre are in any case unsuited.

Finally, there was some confusion in the orders – the absence of local unity of command has already been mentioned – if we are to judge from the various reports and war diaries. The most probable explanation seems to come from Captain Johnson7 OC C Company of 22 Battalion. He says that for several days he and Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew had been pointing out that some of the AA guns were very badly sited and had been suggesting that they should be withdrawn to less vulnerable sites. They had also requested that some of the guns be asked to play a silent role until the troop-carriers appeared. The orders from Force HQ for both these actions to be taken arrived about 3 a.m. on 20 May and it was then too late for any to be moved. But the order for silence may have been misunderstood and may be responsible for a widespread impression that not all the guns came into action.

For the ground troops, then, in the general area of 5 Brigade the air bombardment began shortly after six o’clock in the morning, varying in intensity in different places but reaching its maximum on 22 Battalion. The first phase, violent as it was, was not so exceptional that it might not have been the regular morning tattoo; for, as Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew says: ‘the enemy air force had “drilled” us into expecting his bombing at the same time each

morning.’8 After the end of this first phase, about half past seven or a little before,9 there was a lull and the troops stood down and began their breakfast.

Breakfast had hardly finished, however, when the second and more intense phase of the air attack broke out, about ten minutes to eight. The whole of the area occupied by 5 Brigade forward battalions was savagely worked over; and although the airfield itself, for obvious reasons, was not bombed, its perimeter took the heaviest pounding of all, until the rising clouds of dust and smoke, themselves visible for miles, made visibility in the immediate neighbourhood very restricted.

It was not only the bombers that were so busy. To the men on the ground the air seemed full of fighters and fighter-bombers and many a man that day felt as if particular planes had been told off to give him particular attention. Movement outside cover was so difficult that in the course of a hundred yards a runner might have to go to ground a dozen times. And even within deep gullies or covered by the kindly olives a man outside his slit trench stood more than a sporting chance of being hit by the hailing machine-gun bullets.

While this attack was still at its maximum, and under cover of it, the first gliders came in to land. Both their numbers and the exact time of their landing are difficult to ascertain precisely, because the defending troops were prevented by the dust or the rough character of the ground from exact observation and because memories differ. New Zealand eye-witnesses say between forty and one hundred came down in the Maleme area; while a calculation based on the fact that the Germans at this time used 15 gliders for a company favours the probability that about fifty were used at Maleme. The higher figure must certainly be an exaggeration for which the excitement, the bad visibility, and double counting would sufficiently account. Of these fifty gliders at least three landed south and east of the airfield, while the rest landed near the mouth of the Tavronitis or along its bed.

Eleventh Air Corps states that one group of gliders landed at the time ordered – by our reckoning 8.15 a.m. – and another a quarter of an hour later. Reports from 22 Battalion men vary between 8.25 and 9.15. It is likely enough that there was some margin between the landing of the first glider and the last, and it is probably safe to say that the landings took place between a quarter past eight and a quarter past nine, most of them being over by nine o’clock.

The main landing place, the bed of the dry Tavronitis, was well chosen. Much of it was dead ground to the troops on the slopes above, and in some cases the crews – ten to a glider – were able to form up and either go straight towards their objectives or take up positions on the high ground west of the river. One crew landed more or less on top of a machine-gun post and destroyed it. Others, as will be seen, were able to put the AA guns on the west edge of the airfield out of action. Those that landed east and south were fewer and less dangerous.

Nothing in the German orders suggests that the paratroops were to be landed later than the gliders. The same zero hour is given for the whole Assault Regiment. It is probable enough, however, that within the regiment different units had different times; and it is possible that the glider troops, whose specific tasks may well have had a time priority, were landed earlier than the paratroops and were able to give them some covering fire. At all events the bombing had not ended and it was still only a quarter past eight when the big Junkers 52 began to drop their loads, each between twelve and fifteen men from heights of from 300 to 600 feet; and west, south, and east of the airfield the first wave of paratroops landed.

Paratroops, like glider crews, landed with weapons. But whereas the glider troops could go into action as a formed body as soon as they got themselves and their heavier weapons out of the glider, the parachutists landed as individuals, depending for the most part on the Schmeissers and grenades that they carried, and needed time before they could collect and fight as a team. Their heavier equipment, moreover, had to be got from separately dropped canisters and so there was an initial period of vulnerability – perhaps ten minutes, though not always as long. The defence took full advantage of this and the still more vulnerable moments before landing, when the parachutist still dangled and wriggled in his parachute and floated downwards. All accounts agree on the slaughter that took place at this stage. Nevertheless, enough survived, particularly to the west of the airfield and out of small-arms range, for a strong attack to develop quickly against the Maleme positions.

In the broad sense the pattern of the enemy landings followed the plan already tabulated, though exceptions will be noted; but the collisions with the defenders that followed soon forced many adjustments to the original programme.

The gliders of Lieutenant Plessen’s 3 Company came down at the river mouth, according to plan, and overwhelmed the AA crews

There.10 But an attempt to develop the success into an attack on the airfield itself failed ‘against strong enemy opposition’.11 Plessen himself was killed while trying to make contact with the other glider troops to the south.

Major Koch, with the HQ of I Battalion and 4 Company, had less success. Their gliders landed along the south-east and south-west slopes of Point 107 and the crews could not give one another the necessary support. They lost heavily to the defenders dug in above them and Koch himself was severely wounded. Only remnants made their way to the area of the road bridge where they joined the main body. The ‘tented camps’ on which they had been directed were found to be more or less empty.

The nine gliders of Braun’s detachment – carrying a party from Regimental HQ and elements of III Battalion – were landed according to plan directly south of the road bridge in the bed of the Tavronitis. There they came under heavy fire from D Company 22 Battalion, and Braun was killed. None the less his men managed to seize the bridge intact and overrun some MG posts on the east bank. The Regimental HQ party seems to have hived off at this point, or not long afterwards, and established itself in Ropaniana to the west of the bridge.

While these glider landings were going on the paratroops also had begun their descent. II Battalion landed south of Kolimbari according to plan and, as the area was undefended, was subjected to no interference. One of its companies, 6 Company, was sent west to guard the pass near Koukouli and had severe fighting with Cretans en route. The detachment put down east of Kastelli under Lieutenant Muerbe at once ran into bitter fighting with 1 Greek Regiment and lost its commander and 53 killed, the remainder being wounded and taken prisoner.12 This left 5, 7, and 8 Companies at General Meindl’s disposal for the support of the glider troops in the Tavronitis.

In addition to these three companies he could rely on some support from 13, 14, and 15 Companies of IV Battalion. These three companies landed west of the Tavronitis, and therefore without ground opposition. Many of their heavy weapons and

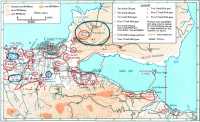

Maleme, 5 Brigade, 20 May

motor cycles had been damaged in landing, but enough were salvaged to make the unit a valuable aid in the attack. The battalion’s fourth company, 16 Company, made its way south on landing to the serpentine at Voukolies and established itself there as a flank guard, though constantly troubled by Cretans.

Thus Meindl had no great reason to be dissatisfied with the initial situation of his forces to the west of the aerodrome. The weakness of his plan, however, had lain in the division of his forces. If anything went wrong with the landing of III Battalion to the east of the airfield it would be difficult for him to pull his regiment together. And something had indeed gone wrong. The battalion was duly landed on the rising ground south of Maleme-Platanias road which had been assumed to be free of enemy. Here its companies at once found themselves in a hornet’s nest, for these slopes were held by the reserve battalions of 5 Brigade – 21 Battalion, 23 Battalion, and the NZE detachment. Two-thirds of the battalion were killed along with all the officers; and the remainder, though of considerable nuisance value, were able neither to launch the intended attack on the airfield from the east nor to make their way east to join Group Centre.

Meindl had jumped at half past eight and taken command. He must at once have appreciated that, since Koch had failed to seize Point 107, the best prospect of progress lay in exploiting the success at the road bridge and trying to develop it into an attack which would take Point 107 from the north-west. At the same time he evidently felt that a flanking move from the south might be worth attempting. He could assume that his own flanks to the west and south were reasonably safe and, in any case, if he were to get on with his task would have to do so. It is not known how soon he had news of III Battalion, but obviously his best course was to press home the attack from the west with or without support from the east. For forces with which to launch it he had Braun’s group already engaged; the remnants of Koch’s group if they had yet begun to make their way down into the riverbed; the remains of Plessen’s company from the river mouth, which cannot have had many casualties; 5, 7, and 8 Companies from II Battalion; and the heavy weapons of IV Battalion with 15 Company as well.

He therefore sent 8 Company and the available troops of IV Battalion to support Major Braun at the bridge by attacking on either side of it; and ordered 5 and 7 Companies under Major Stentzler to cross the river south of 22 Battalion’s left flank and thence attack north-east towards the heights below Point 107.

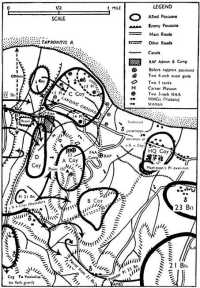

Maleme, 22 Battalion, 20 May

It is now time to turn to 22 Battalion.13 As Maleme was so important and as, owing to the difficulty of movement, the shortage of reserves, and the early breakdown of communications, the story

of the unit on 20 May is very much one of companies and platoons fighting in isolation, it will be necessary first to go into considerable detail about their dispositions.

The 22nd Battalion, then, on the day the battle opened had a strength of 20 officers and roughly 600 other ranks. It consisted of Battalion HQ and five rifle companies; for Headquarters Company fought as a rifle company. Battalion HQ was a little to the north of Point 107 and had with it a small reserve consisting of a platoon of A Company and miscellaneous HQ personnel. This, with the two I tanks and the carrier platoon, was the only reserve available to Colonel Andrew.

The greater part of Headquarters Company was posted round Pirgos14 village under Lieutenant Beaven.15 But its carrier platoon under Captain Forster16 had been put directly under battalion command and was stationed in the olive trees near the Maleme-Vlakheronitissa road; and its pioneer platoon under Lieutenant Wadey17 was at the AMES near Xamoudhokhori, so far away as to be in effect independent.

A Company, commanded by Captain Hanton,18 held Point 107 and the high ground central to the battalion’s position. B Company, commanded by Captain Crarer,19 held the ridge which ran east of the Maleme-Vlakheronitissa road, and one of its platoons straddled the road between Point 107 and Vlakheronitissa. C Company, under Captain Johnson, was disposed round the perimeter at the edge of the airfield, with 13 Platoon on the north between the airfield and the sea, 14 Platoon on the south along the road and canal, and 15 Platoon west from 13 Platoon to the road bridge.

D Company, commanded by Captain Campbell,20 held the east bank of the Tavronitis from and including the road bridge south to a point just south-west of Point 107. No. 18 Platoon was stationed to cover the road bridge, 17 Platoon held the south wing of the company position, and 16 Platoon was between these two

but higher up the north-west slopes of Point 107. About half a mile south of 17 Platoon and also on the east bank of the Tavronitis was a platoon of 21 Battalion.

Also under command were two platoons of 27 MG Battalion. One, under Second-Lieutenant Brant,21 had a section with two MMGs on improvised mountings so sited in D Company area as to cover the road bridge and part of the riverbed; and the second section had two unmounted MMGs sited not far away but higher up so as to cover the airfield. The other platoon, under Second-Lieutenant Luxford,22 had one section on the east edge of the airfield covering it and the beach and the second on a spur near Maleme village from which it could cover the same targets. Both platoons were short of ammunition, the first having enough for only about seven minutes’ rapid fire.

Two 3-inch mortars covered the airfield also, both without base-plates and both short of ammunition. And the two I tanks, also under command, were hidden north of Battalion HQ, ready for counter-attack towards the airfield.

In the battalion perimeter, but not under command, were the ten Bofors guns sited round the airfield, the two 3-inch AA guns sited near Point 107, and the two 4-inch naval guns of Z Battery RM, both sited on the slopes above D Company’s right centre.

As soon as the landings began the battle broke up into a number of separate actions in separate areas, and Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew, handicapped by hopelessly bad communications, found it more and more difficult to operate his battalion as a unit. Our best hope of offering an intelligible account of the day’s events is therefore to take each group separately, distinguishing D Company along the bed of the Tavronitis; C Company on the airfield; Headquarters Company fighting round Pirgos; and Battalion HQ with A and B Companies in the general area of Point 107.

To Captain Campbell, the commander of D Company, parachutists and gliders seemed to arrive simultaneously, the latter coming down ‘with their quiet swish, swish, dipping down and swishing in’.23 Most gliders landed in the riverbed, although odd ones came down in the company area. The paratroops, however, tended to land both in the company positions and on the high ground west of the river. The gliders were those of Major Braun and Major Koch, while the paratroops belonged to II and IV Battalions.

Of the gliders six were counted in 17 Platoon area and few of the crews lived to congratulate themselves. Paratroops landing inside the perimeter met equal severity.24 But one glider landed close to Corporal Bremner’s25 MMG section and caused casualties, among them Brant, the MMG platoon commander. Nevertheless, while ammunition lasted – not long – the machine guns were able ‘to get some juicy shooting in among the gliders in the riverbed’.26

Where gliders landed, as many did, too far from the defenders’ lines or defiladed, the crews were a more difficult target as they made for cover. And paratroops landing on the far side of the river were mostly out of effective small-arms range. A suggestion from D Company that the two 4-inch naval guns should undertake targets across the river was rejected on the ground that the guns were sited for targets at sea.27 D Company therefore had the exasperation of seeing the enemy take over Polemarkhi and Ropaniana virtually unmolested.

Meanwhile Braun’s glider party at the bridge had forced back the two sections of 18 Platoon holding that flank to a new line on the canal where there were prepared positions. This was the only part of D Company’s line that was strongly attacked, and the enemy kept infiltrating men across the riverbed under cover of the bridge pylons so as to drive a wedge between D Company and C Company.

Unfortunately, this area round the bridge was vulnerable as well as valuable. The bridge was a D Company responsibility and Campbell had one section of 18 Platoon north of it. But its positions here were too far forward to give a good field of fire and yet could not be brought back to a better line without basing it on the RAF administrative buildings and encampments. The presence of these and of large numbers of RAF, FAA, and RM personnel in the vicinity made it difficult for Campbell and Johnson to make the most efficient joint arrangements for tactical defence. Requests by Andrew that these miscellaneous troops should come under his command had been refused. Some arrangement seems to have been made just before the battle for the RAF men to have

infantry training and be given infantry positions. But it was too late and, although the armed men among them did do some fighting, no clearly concerted plan is discernible.28

The result was that Braun’s glider force was able to get a strong foothold in this quarter very early in the attack, and one which Meindl appreciated and exploited with speed and determination.

South of D Company there was also trouble. Paratroops and at least two gliders had landed near the positions of the 21 Battalion platoon. For the most part these were faithfully dealt with – 17 dead Germans were counted near one glider – or at least met a reception that discouraged aggressive behaviour. But Lieutenant Anderson,29 the platoon commander, was killed, and Sergeant Gorrie30 who took over could not make contact with 21 or 22 Battalion because of enemy parties in between. He therefore posted his men a little farther south of D Company and decided to stay there till dark, doing as much damage as possible. This was a useful decision, for in the course of the afternoon he broke up two enemy attempts to cross the river. Had it not been for this platoon Major Stentzler’s two companies might have come into action against the south flank of 22 Battalion much earlier than they did and pressed with more determination. As it was, though no precise story of Stentzler’s movements can be given, it seems likely that he was forced to detour farther to the south and then come north-west again, taking undefended Vlakheronitissa on the way.

No doubt because of the firing caused by all this, Campbell felt uneasy about his left flank. But 16 Platoon reported that it had checked a thrust into the company area from this quarter,31 and for the rest of the day he was not unduly troubled. The right flank remained his major worry. He could not telephone Battalion HQ because his telephone had been put out of action by a bomb; but he sent runners to warn HQ of the threatened thrust across the bridge. Of the two sent only one came back.

In the afternoon D Company’s right flank became more and more uncomfortable and at one point Campbell decided to call upon the RAF personnel in the neighbourhood for help; for by a previous arrangement they were to have assembled in a nearby

wadi as reinforcements. They were not to be found, however,32 and the enemy continued to infiltrate from the right and give trouble.

Yet by about three o’clock D Company was reasonably happy. No. 18 Platoon, though reduced to nine men, was holding on in its canal positions; 17 Platoon had adjusted its own positions by moving higher up the slopes; and 16 Platoon in the centre had disposed of a possible enemy attempt to infiltrate from the south. The troublesome features of the situation were that the forward platoons were more or less isolated from Company HQ, and Company HQ itself had been quite out of touch with Battalion HQ even by runner since midday; that the volume of MG and mortar fire from the west on the company positions was getting steadily heavier; and that the threats from the flanks might at any time become serious.

On C Company front the situation, though worse, was not altogether dissimilar. When the day began the company had been reasonably strong with 117 rifles, 7 Brens, 1 MMG, 6 Browning MGs, and 9 tommy guns. The troops were all well dug in. No. 13 Platoon, between the north end of the airfield and the sea, was sited to repel beach landings and cover the airfield itself with fire; 14 Platoon, between the south edge of the airfield and the canal, was to cover the airfield with fire and deal with attacks from the south-east and south-west; 15 Platoon, on the west edge of the airfield, had 13 Platoon as its right boundary and the road bridge as its left. Its task was to defend the airfield against attacks from the west.

Neither the company commander nor his platoon officers were quite happy about these dispositions, however. There was too much dead ground on the front of 15 Platoon, and yet it had been impossible to cross the riverbed and take this in without spreading the front still farther and accentuating the existing difficulty that it would be very hard for the three platoons, separated by the flat expanse of airfield, to give one another mutual support. And there was also the radical weakness already discussed at the road bridge between C Company and D Company.

The battle began for C Company, as for the others, with the second phase of the bombing. So intense was this round the airfield that from C Company HQ it was impossible to see more than a few yards for the dense clouds of dust and smoke. This no doubt explains why no gliders were seen.

When the bombing ceased – having killed five men and wounded one in 14 Platoon and Company HQ – and visibility returned, parachutists could already be seen landing towards Pirgos in the east and in larger numbers west of the Tavronitis. Scarcely had the first dropped when the defence found that enemy, no doubt Lieutenant Plessen’s glider troops, were already active against the two flanks of 15 Platoon. Lieutenant Sinclair,33 the commander, gives some impression of what it was like. ‘Of course the fight was on. We were all more or less pinned to our positions, and as I was fired on from SE, S., SW, W., NW, and NE it was a queer show. ...’34

It was on 15 Platoon, in fact, that most of the pressure at this stage came in C Company. The front was some 1500 yards long and Sinclair had only 22 men. Apart from the fire he describes, there was very persistent firing from a drain near the south-west corner of the airfield, and from this we may guess that the enemy – having pushed back the section of 18 Platoon – had already secured a lodgment east of the road bridge. No. 15 Platoon must have given a good account of itself, however, since the attempt at an assault on the airfield after taking the AA guns was repelled.35

There was nothing the company commander could do to help. All telephone lines had been cut during the bombing, and when they were relaid they were at once cut again. No runner could have crossed the flat, fire-swept airfield.

By ten o’clock it seemed to Captain Johnson that the enemy was infiltrating through the north flank of 15 Platoon towards 13 Platoon. He asked the CO for permission to counter-attack with the two I tanks which were dug in not far from his own HQ. But Andrew, anxious to conserve his trump card for a more desperate situation, refused.

To Sinclair the morning did not seem to be going so badly. His later comment no doubt reflects his spirits at the time: ‘Plenty of good targets and an interesting attack provided all the diversion one needed.’36 But about eleven o’clock he was hit through the neck, and though he was able to carry on for about an hour – mainly throwing grenades at a petrol dump so as to set off a stack of RAF bombs in front of him – the noonday heat was too much for him and he fainted from loss of blood. In an obscure situation

The most credible interpretation of events seems to be that at about this time his southern section was cut off – PWs were seen being marched off from this area by Captain Campbell – and that some of his northern posts were also overrun, but that because his centre held out till towards dusk and because 13 and 14 Platoons kept up steady fire the enemy was not able to make further progress.37

It was still mid-morning when other worries developed for Captain Johnson. At about eleven o’clock the thrust from the bridge area threatened to cut him off from D Company. The enemy was in possession of the RAF camp and could be seen advancing towards Battalion HQ behind what appeared to be a screen of PWs. Johnson therefore sent a section of 14 Platoon under Lance-Sergeant Ford38 to try to outflank this force and link up with Battalion HQ. Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew, however, ordered the section to withdraw with the words ‘look after your own backyard – I’ll look after mine.’39

There was a new job waiting for Sergeant Ford when he got back. He was to cross the airfield with two men and order the commander of 13 Platoon, Sergeant Crawford,40 to take action against the north-easterly movement of the enemy from 15 Platoon’s northern flank. Ford and one of his companions succeeded in getting across the airfield. But it was impossible for anyone to get from the positions of 13 Platoon to the help of 15 Platoon. The enemy in the RAF camp area was bringing too heavy a flanking fire across the front.

In the earlier part of the afternoon the situation on C Company front did not greatly change, and the most notable event was the arrival at Company HQ of an English officer from 156 LAA Battery and about eight of his men. These men – except two bomb casualties – hastened to join the strength of the company and were duly armed. A little later they were to join, at their own earnest request, a counter-attack with 14 Platoon. But, as this attack was important for its effect on Andrew’s view of his battalion’s situation, an account of it is best left until Battalion HQ comes to be considered. It will be sufficient to say now that after this attack had failed C Company, like D Company, was cut off from contact with Battalion.

The third company isolated from Battalion HQ was Headquarters Company with three officers and about sixty men. But in its case

isolation began with the battle. For the landing began with the descent of several gliders, no doubt part of Major Koch’s group, between the two. These were reinforced almost at once by five plane-loads of parachutists, probably from 9 Company of III Battalion. With these a small field gun was also dropped. A second group of parachutists arrived about half-way through the morning. All these had heavy losses both in the descent and in the fighting that at once followed. But the survivors, well armed with automatic weapons, were a force to be reckoned with; they quickly took advantage of the cover afforded by the vineyards and were able to establish strongpoints in disconcerting places. Thus one party set up a post in a brick house between Headquarters Company’s south-west flank and Company HQ and made communications between the two almost impossible.

The gap between Company HQ and the section post of Sergeant Matheson’s41 platoon on this south flank was too wide, presumably because the men did not have the same experience in infantry tactics as those of an ordinary rifle company. And the two posts were without automatic weapons.42 the result was that both were soon overrun,43 although the enemy could make no headway against the village and the main positions. Indeed, he seems to have made no really formidable assault, and the chief trouble came from snipers and small parties who kept wandering about in order to make contact with one another.

For Lieutenant Beaven, too, contact was a prime concern. His only friendly visitors during the day were a party of men from A Troop, 7 Australian LAA Battery, and a runner from Wadey’s pioneer platoon. The Australians, driven off their guns, presumably by the glider detachment, had swum along the coast and were now incorporated into the company, where they did good work with the field gun which the enemy had dropped.

The runner from the pioneer platoon, Private Wan,44 had left the AMES about three o’clock with another runner, Private Bloomfield,45 the latter carrying a message. Bloomfield was killed on the way, and Wan had not been able to recover the message. It could hardly have been more than what Wan was able to tell: that the pioneer platoon had shot up a glider without being themselves attacked and that they had not been able to make contact with Battalion HQ.

Beaven was now so worried about the lack of news that he decided to send Wan with another message to Battalion. The message gives a useful picture of the situation on the front:46

Paratroops landed East, South, and West of Coy area at approx 0745 hrs today. Strength estimated 250. On our NE front 2 enemy snipers left. Unfinished square red roof house south of sig terminal housing enemy MG plus 2 snipers. We have a small field gun plus 12 rounds manned by Aussies. Mr. Clapham’s two fwd and two back secs OK. No word of Matheson’s pl except Cpl Hall and Cowling.

Troops in HQ area OK.

Mr. Wadey reports all quiet. No observation of enemy paratroops who landed approx 5 mls south of his position.

Casualties: killed Bloomfield.

wounded Lt Clapham, Sgt Flashoff, Cpl Hall, Pte Cowling, Brown.

Attached plans taken off Jerry.

1650 hrs

G. Beaven, Lt OC HQ Coy

Finally, however, Beaven decided he had better wait till dark before sending this message. By then it was too late.

An attempt was made to get in touch with B Company. But the runner sent failed to return and a patrol sent after him met an enemy patrol, failed to get through, and had to return with casualties.

It is now time to see how the situation was developing with the central group of the battalion, A and B Companies and Battalion HQ. The two companies, although they had been heavily pounded by the bombing and had their share of trouble from the paratroops and glider crews in the area, were not at first in the front line in the same sense as were the other companies nor so heavily engaged. In the afternoon the effect of Stentzler’s activities from the south-west began to be felt, with his 5 and 7 Companies

probing the south front of B Company and trying to find a way north between A and B Companies. But, in the early afternoon, these pushes were being held without great difficulty and there is no evidence that Stentzler had yet begun to exert all possible pressure when darkness came. No doubt he was nervous himself of being attacked in the flank by 21 Battalion.

Battalion HQ had come in for a particularly heavy share of the bombing. Headquarters itself was not hit, though Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew received a nick from a splinter while forward observing. ‘the immediate countryside, before densely covered by grape vines and olive trees was bare of any foliage when the bombing attack ceased and the ground was practically regularly covered by large and small bomb craters.’47 While the bombing lasted the dust cloud was too thick for good visibility. Just as it began to settle the watchers from Battalion HQ saw the gliders coming in, the nearest landing about 100 yards to the north and another on the road from Maleme to Vlakheronitissa. The parachutists followed, and the battalion staff had a panoramic view of the landings all round them. They soon ceased to attend to it, however, when they observed a party of enemy about 700 yards away towards Pirgos trying to bring a small gun into action. With timely rifle fire they were able to put a stop to this.

Soon there were more serious worries. The battalion telephone lines, which shortage of tools and time and the difficult character of the country had made it impossible to dig in,48 had been cut by the bombing; and no doubt what the bombing had missed was looked after by the enemy on the ground. This isolated Battalion HQ from its more distant companies and made it dependent on its single No. 18 wireless set for communication with Brigade HQ. To make matters worse the set itself temporarily failed soon after the landing of the glider troops, and it was not till about ten o’clock that the landing of hundreds of paratroops in the area could be reported.

Within the battalion therefore the CO was from the first dependent on runners, at all times a slow and clumsy means of communication. In these particular circumstances the runner had the additional handicap that his route was endangered by snipers, and even if he succeeded in getting through he was bound to have lost time in detours or in fighting. Yet, while runners were still getting through to all companies except HQ Company – where

Andrew himself tried and failed – the situation was not so bad. Its chief defect in the early stages was that Andrew could at no time rely on having an up-to-the-minute knowledge of the general situation of the battalion. In the later stages its disadvantage was to prove well-nigh decisive; for, unable to get runners through at all, he was to reach a quite misleading view of the position of some of his companies.

In the morning, however, one thing soon became clear enough. The main enemy concentrations were to the west of the Tavronitis. Accordingly, before half past ten Andrew asked Brigade HQ to have the area Ropaniana-Tavronitis searched with artillery fire and sent his Intelligence Officer to the detachment of 4-inch guns of Z Battery RM with the request that they should engage the mortars and MGs which were by this time harassing his battalion area. The 4-inch guns were unable to do this because of their siting; but A and B Troops of 27 Battery, on the basis of the order relayed from 5 Brigade HQ and a message from their OP on Point 107, were able to bring down effective fire in spite of unpleasant investigations by enemy aircraft. Soon C Troop was also active but, because it had to rely on direct observation, its targets were found east of the airfield.

By the time these guns were brought to bear, however, the enemy attacks were already well under way, and something of Andrew’s concern can be seen in his message to Brigade HQ at 10.55 a.m. that he had lost communication with his companies and that he would like 23 Battalion to try and contact Headquarters Company.49 At this time he seems to have estimated that 400 paratroops had landed: 150 west of the river, 150 east of 22 Battalion, and 100 near the aerodrome.

As the morning wore on RAF and FAA ground staff who had been driven out of the area near the road bridge came filtering back and were followed up the slopes towards Point 107 by small enemy parties. According to some observers the enemy were driving these men demoralised in front of them and using them as a screen. It seems safer, however, to take the more conservative explanation favoured by Major Leggat50 – then second-in-command of 22 Battalion – that the inexperienced RAF and FAA men exaggerated the forces behind them. At all events Leggat relates that on one occasion during the morning he went to investigate a few shots and found a demoralised RAF party. Suspecting that the MG fire troubling them came from an isolated sniper, he went

forward with others from Battalion HQ, crossed the wire, and was ‘fortunate enough to find the machine-gunner with a stoppage.’51

Shortly after midday 22 Battalion told 5 Brigade that the enemy was using a 75 and heavy machine guns from west of the Tavronitis, and under cover of this he seems to have been making further probes up the ridge on the right of D Company. About this time also A Company began to feel pressure from the south-west, while in C Company 13 Platoon made its attempt to help 15 Platoon.

In the early afternoon these pressures grew stronger. About four o’clock – or perhaps earlier – mortar fire from the RAF administrative area forced Battalion HQ to move about 200 yards south-west of its first location and just inside B Company area. The artillery officers from the OP on Point 107 had long since found themselves hopelessly out of touch with their guns owing to the breakdown of communications. They therefore joined 22 Battalion as infantry and their two officers, Captain L. G. Williams and Lieutenant G. P. Cade, were given command of the RAF and FAA men.

A message sent by Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew to Brigade at 3.50 p.m. indicated his growing anxiety. His left flank had given ground – either an allusion to adjustments in D Company area or a mistake for his more seriously endangered right flank – but he still thought that the situation was in hand, although he again asked for contact to be made with Headquarters Company because he needed reinforcements.

All this time, in fact, in common with the rest of his battalion, he had been expecting 23 Battalion to come to his support in its counter-attack role, and flares had been sent up – at what time is not clear – to indicate that it was needed.52 the non-appearance of this support was generally assumed to be due to the difficulties of movement under the vigilance of the numerous enemy fighter planes. Finally, at 5 p.m. Andrew asked Brigadier Hargest for the counter-attack by 23 Battalion to be put in and was told shortly afterwards that this could not be done as 23 Battalion was itself engaged against paratroops in its own area. It was at this point that Andrew decided he could wait no longer but must resort to the last card in his hand: the two I tanks and 14 Platoon.

Accordingly, at a quarter past five, the two tanks with 14 Platoon in support moved off down the road about 30 yards apart, making for the Tavronitis bridge. Almost at once the second tank found that its two-pounder ammunition would not fit the breech block and that its turret was not traversing completely. It therefore withdrew. The leading tank went forward until it reached the riverbed, passed under the bridge from the southern side and went north about 200 yards. There it bellied down in the rough bed of the river and, its turret having jammed, was abandoned by its crew.53

No. 14 Platoon, under Lieutenant Donald,54 consisted of two sections of New Zealanders and a third section made up of the six men from 156 LAA Battery whose officer had begged to be allowed to take part. They accompanied the two tanks, deployed towards the left. They met withering fire from the front and from the left. With one tank turned back and the other out of action, they had no course but to withdraw. This they did. The English officer was killed and Donald, himself wounded, brought back only eight or nine men from his gallant platoon, most of them also wounded.

Captain Johnson reported to the CO that the counter-attack had failed and asked for reinforcements. His own position was rapidly worsening. No. 15 Platoon and the west section of 13 Platoon had been overrun. No. 14 was now practically destroyed. Company HQ with its cooks, stretcher-bearers, and runners could not hope to hold the inland perimeter of the airfield long. Johnson therefore told Andrew that he could probably hold on till dark but would then have to be reinforced. Andrew replied that he must ‘hold on at all costs’.55 From this time communications between the two were cut and no runners got through.

Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew now had to make up his mind what to do. He again got in touch with Brigade HQ by wireless and told Brigadier Hargest that the counter-attack with tanks had failed. He said he had no further resources and that as no support from 23 Battalion had come he would have to withdraw. Hargest replied: ‘If you must, you must.’ But at this time, according to Andrew, by ‘withdrawal’ he did not mean withdrawal right away from the airfield but only as far as the ridge held by B Company. And presumably Hargest understood him in this sense.

This conversation seems to have taken place about 6 p.m., and in the course of it or another conversation about the same time Hargest told Andrew that he was sending two companies to his support – A Company of 23 Battalion and B Company of 28 Battalion. These two companies, Andrew understood, were to be expected very shortly.56

While waiting for them to come Andrew would have had leisure to contemplate what must have seemed a very grim situation. He had had no contact with Headquarters Company all day, and since paratroops had been seen to land in its area in considerable numbers there seemed grounds for assuming that the company had been overrun. A Company, though it had had fighting, was on the whole intact. B Company also was intact but was threatened with a thrust from the south-west. C Company had lost at least part of 13 Platoon, 14 Platoon was almost destroyed, and it seemed probable that 15 Platoon was wholly lost. D Company had been out of touch since midday and according to at least one report had been wiped out. Colonel Andrew could therefore count certainly on only two out of his five companies.

The tactical situation seemed to answer this apparent weakness in forces. The enemy had torn a hole at the road bridge and could be expected to reinforce success from the ample strength that he had built up undisturbed across the river and out of range. The line of the airfield north of the bridge was destroyed with the loss of 15 Platoon. If D Company had been wiped out there was nothing to prevent the enemy crossing the Tavronitis at any point along its length. And the attack from the south-west against B Company front suggested that if the battalion remained in its present positions it might be cut off by morning.

Moreover, mortars and machine guns were by now out of ammunition or knocked out. The tanks and the infantry reserve were gone. There was no sign of reinforcement, unless the two companies from 23 and 28 Battalions arrived soon.

In such a situation Andrew evidently felt that if he did not use the cover of darkness that night to adjust his positions he could not hope to withstand the renewed attack that was bound to come the following day; for if the enemy had been able to make such progress against his full battalion, starting from scratch, what might he not be able to do with his forces fully organised on the ground and the tactical advantage against a battalion reduced to less than half its strength?

Considerations such as these were in Andrew’s mind when he spoke to Brigadier Hargest of limited withdrawal after the failure

of the counter-attack with tanks. By nine o’clock that evening, when the two supporting companies had still failed to appear, his mind was made up. He would withdraw to a shorter line based on B Company ridge. Between nine o’clock and nine-thirty, therefore, he again spoke to Hargest on the 18 set – by this time so weak that this was the last message he was able to pass – and ‘told him I would have to withdraw to “B” Coy ridge.’57 What Brigadier Hargest replied is not recorded. He can hardly have grasped the full implications of the proposed move, though they should have been clear enough to a commander familiar with the ground, and seems to have accepted Andrew’s view without feeling that the situation called for further action on his own part.

Andrew was in the HQ of B Company when he took this decision. Messages about the projected move were sent out to all the other companies by runner, including C, D, and Headquarters Companies. The runners to the last three did not get through.58

Meanwhile Captain Watson,59 OC A Company of 23 Battalion, had left 23 Battalion about dusk and taken his company via 21 Battalion, the AMES and Xamoudhokhori, making for 22 Battalion. Captain Rangi Royal60 of 28 Battalion had also set off with B Company, but for reasons to be explained below arrived too late to affect the situation.61

Between nine and ten o’clock Watson reached B Company ridge and found Battalion HQ there. At this point the narrative is confused. Watson says he was told that D Company had been wiped out and that he was to take over its position. But 22 Battalion sources suggest that it was A Company’s positions he was ordered to take over, and the fact that he was given Lieutenant McAra62 of A Company 22 Battalion as guide lends colour to this.63 If so, the likely explanation seems to be that, if D Company had got Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew’s message and come back, Andrew would have placed them in the positions formerly occupied by A Company; but that, since the failure of D

Company to appear seemed to confirm his belief that it had been wiped out, he now gave up hope of it and decided to use Watson’s newly-arrived company in its stead. And this in its turn suggests that in spite of the withdrawal of A Company to B Company ridge, Andrew had not entirely given up hope of holding Point 107.64

At all events Captain Watson and Lieutenant McAra duly set about placing the platoons. As 8 Platoon was being put into position there was a burst of fire which killed McAra and wounded several others, including Lieutenant Baxter,65 second-in-command of the company, who had been anxious to go into action with his old platoon. Shortly afterwards the resolute Sergeant Gorrie made his way into the lines of the newly-posted company, bringing with him the platoon of 21 Battalion which had been doing such good work all day farther down the Tavronitis.66

Meanwhile a further conference had been going on at 22 Battalion HQ on B Company ridge. Now that Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew had made his limited withdrawal the drawbacks of the new position had become all too apparent. Point 107 had previously been the centre of his defensive system, screened by the companies round the perimeter. It was now, held by Watson’s company, no more than an outpost. If that company failed to hold it when attack began again next day, the enemy by taking it would overlook B Company ridge which was now the main position. B Company ridge itself afforded little natural cover and there were not the tools, even if there was enough time before daylight, for new defences to be dug. Exposed to the inevitable strafing and bombing next day from the air as well as fire from the enemy’s ground forces, A and B Companies would probably have to endure heavy casualties as soon as it was light. And once it was light it would be impossible to extricate them. Moreover, there was still no sign of B Company 28 Battalion, while the silence of the other companies seemed every hour to confirm Andrew’s fears for them.

It is in such terms that we must explain his next decision: to withdraw to 21 and 23 Battalions while he still had the cover of darkness. His mind made up, he asked Watson, who had meanwhile come back to report, to provide a guide to 23 Battalion and use his own company to cover the withdrawal.

Captain Watson agreed to do so, went to warn his men of their new role, and returned to 22 Battalion HQ about midnight in

time to see the troops move out.67 About two hours later Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew, who had remained to see the area clear, told him he might also pull out his company. This Watson did, 8 Platoon carrying its wounded.

The first phase of the battle for Maleme virtually ends with this decision. From now on it was a question of recovering vital positions instead of keeping them, of counter-attacks difficult to mount instead of holding on in prepared defences. Ultimately, in fact, the withdrawal from Maleme was to entail the loss of Crete.68 It would be unjust to Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew to suggest that he should have foreseen this as clearly as the advantage of hindsight enables us to see it ten years later. None the less, he had been given a position to defend which he must have known to be of the greatest importance. And it is necessary to consider whether there was not some other course he could have adopted.

The withdrawal falls into two parts: that from Point 107 and that from B Company ridge. Was the first necessary? When he made up his mind to leave Point 107 Andrew thought that he could count certainly on only two companies, A and B. This, as will be seen in the sequel, was to despair of the others too soon. True, runners had failed to get through; but it was not unprecedented for companies to be cut off and yet continue fighting. Had he remained where he was it should have been possible to push through patrols during the darkness, find out the true state of affairs with HQ, C and D Companies, bring in what remained of them, and build up a new tactical position on Point 107.

Again, even had he been right in thinking his outlying companies destroyed, he still had A and B Companies almost intact and he had been told that there were two further companies on the way to reinforce them. Even if, when Hargest had first promised these, in the late afternoon, Andrew had assumed their almost immediate arrival, he must presumably have learnt when he spoke to the Brigadier again about nine o’clock that they had not left till dusk.69 they might be delayed, but to assume that they would not get through at all was surely being too pessimistic. And if their arrival could thus be counted on, then he could expect to have four

reasonably strong companies with which to hold a narrower perimeter based on Point 107.

That this new perimeter would have been exposed to powerful attacks by ground and air forces next day is certain. And it might well have been completely cut off from 21 and 23 Battalions. But there would have been good hope of counter-attack, and so long as it held out the enemy could not have secure possession of the airfield or give his undivided attention to driving farther east.

But, even supposing the case for withdrawing from Point 107 had been stronger than in retrospect it now seems, it is hard to see how a withdrawal to B Company ridge would improve matters. If, as his placing of Watson’s company suggests, Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew intended to put the two reinforcing companies on Point 107 as they arrived and hold A and B Companies on B Company ridge, this seems a much weaker plan than to concentrate his whole force on and around Point 107 itself.

In fact, however, now that he had made his first move he was forced to consider a second: withdrawal to 21 and 23 Battalions. As we have seen he decided in favour of this; and indeed it is likely enough that he could not have held out next day with B Company ridge as the basis of his defence. But since he had first retired to it Watson’s company had arrived, and he might have taken this as increasing the probability that Royal’s company would also appear. There was still time to change his mind and go back to Point 107. The only two companies which seemed to have got his orders were with him; to have reversed these orders would not have been difficult. If the other companies were not wiped out or had not received the orders they would be none the worse for the change in plan. Even if they had received them and were planning to join him later, they would have had no difficulty in finding him.

Failing such a reversal of plan, he had no course but to go on withdrawing; and how unfortunate for the future of the defence that course was, the story of the events that followed will make plain in due time. But it would be unfair to pass on from this isolation of alternatives open to Andrew without a reminder of the hard conditions in which he had to make his choice.

He had spent a most exacting day trying to control a battle where all the circumstances were inimical to control. Communications within his battalion had failed him almost completely; and outside it they had proved extremely bad. He and his HQ had been severely harassed by bombing and strafing throughout the day to an extent for which neither training nor experience had

prepared them.70 the enemy attack itself was of a kind still novel and from the start induced the feeling – and the reality as well – of enemy all round the perimeter and inside it also. The battle had begun with an enemy breach in the defence. The support he had expected and counted on from 21 and 23 Battalions had failed to materialise and this meant a radical departure from the original battle plan. His own counter-attack with the treasured tanks and 14 Platoon, all that he had to call reserve, had completely failed. He had been unable, through this same shortage of reserves, to give any help to his sorely tried companies. And, finally, he seems not to have been able to impress upon Brigadier Hargest the full difficulty of his predicament. In such circumstances, and exhausted in mind and body, he saw his situation in a blacker light than the facts warranted.

The non-appearance of B Company 28 Battalion all this while was most unfortunate; for had it arrived at the same time as A Company 23 Battalion it might have helped to dispose Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew to more sanguine views. What had happened to it?

Captain Royal, like Captain Watson, received orders to set off at dark and report to 22 Battalion, ready to assist if required. The company left 28 Battalion about seven o’clock with eight and a half miles to go and made its way along the main coast road as far as 23 Battalion. Just before getting there it met two enemy machine-gun posts, carried them at the bayonet point, and with the loss of two killed disposed of about twenty enemy. At this stage the company was joined by Lieutenant Moody71 with a small party from 5 Field Ambulance which 22 Battalion had asked for earlier in the day.

At 23 Battalion the combined party picked up Private Schroder72 as guide and followed the route already taken by A Company. On the way they met various stragglers who said they had been ordered to retire to 23 Battalion. At Xamoudhokhori they took the right-hand road instead of the left-hand track. Instead of taking them to B Company this led them to Pirgos, through which they passed, getting no reply to their shouts for 22 Battalion. Eventually, moving west along the main road, they found themselves on the east edge of the airfield. They could see Germans

lying about in the gunpits and had a grenade thrown at them. Justly incensed, they debated whether they should attack, but decided they must stick to their task and join 22 Battalion. The guide finally found the original Battalion HQ, by this time empty. They therefore came back through Pirgos to Xamoudhokhori and there met Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew emerging from a gully with part of B Company. With this party they made their way back to 23 Battalion, having increased their numbers en route from 114 to 180.

It has been indicated that Andrew accepted a pessimistic view of the fate of his other companies. The day’s events on this front must now be rounded off with an account of each of them.

At last light D Company were not altogether displeased with the day’s operations, in spite of the lack of communication with Battalion HQ. The nine survivors of 18 Platoon on the canal were still in position. No. 17 Platoon had only about a dozen men left unwounded, but these were still full of fight, though their ammunition supplies were lower than their spirit. No. 16 Platoon had had only light casualties.

Captain Campbell knew there were enemy on his left and right, but for the time being at least – especially after dark – these seemed content to count the day’s evil sufficient. Like the rest of his company he expected to take part in a general counter-attack. A story brought by a marine that the battalion had gone he did not believe, and he had solved the food problem by breaking into a ration dump. Water was a serious difficulty because the enemy lay athwart the only source of supply.

It was while searching for water that Campbell and his CSM discovered that the battalion had gone. This revelation and the shortage of ammunition and water was a shock to the men and dashed their spirits. It also altered Campbell’s view of the situation: he had to decide whether to follow or to stand fast in the hope that his positions might be used as the pivot of a counter-attack from the south, this being one of the tentative plans considered before the battle. After interrogating wounded he met in the battalion area he found that none of them knew the new location. He concluded that the withdrawal was a complete one and decided he must follow suit.

His plan was to send the remnants of 18 Platoon, under Sergeant Sargeson,73 south to the coast through a gap in the hills with the worst of the wounded. Having got there Sargeson was to turn

east along the coast in the hope of being picked up.74 No. 17 Platoon under Lieutenant Craig75 was to go south along the Tavronitis and turn east round the flank of Point 107. No. 16 Platoon, with Company HQ and a mixed party of RAF and RM, were to make their way east along a track known to Captain Campbell.

The plan, like most plans, worked out only in parts. Sargeson got his party safely through to the coast and turned east to Sfakia in time to be embarked. Craig found the enemy astride his route in force. He turned back and tried to go east from his original position. But the enemy had followed Campbell on to Point 107 and was too strongly posted for a party short of ammunition to be able to force a way through. Craig decided to wait in the hope that daylight would reveal a way through. His reading of the situation was that the enemy was not really well established. Unluckily morning found him surrounded, except for one of his sections which he ordered to slip away and which made good its escape. The remainder of the platoon, with no more than twenty rounds of ammunition and some wounded, could only surrender.

Campbell’s party consisted of 80 or 90 men, of whom 26 were D Company and the rest RM and RAF. They went due east and passed a party of enemy who had lain up for the night and among whom the CSM tossed a grenade ‘for good luck’. On the Maleme– Vlakheronitissa road they met Captain Hanton of A Company, who had sent his platoons ahead and then lost contact with them.

Shortly afterwards – about four o’clock – a runner arrived from C Company with a message for Battalion HQ. Campbell sent him back with orders that Captain Johnson should withdraw his company and join D Company. This therefore seems a good point to take up the story of C Company.

At the end of the day 13 Platoon still held the beach and C Company HQ, with the few survivors from 14 Platoon, still held a copse on the inland side of the airfield. ‘the surviving men were in excellent heart in spite of their losses. They had NOT had enough. They were first rate in every particular way and were as aggressive as when action was first joined.’76 their fire power was still strong, as two Junkers 52 found in the late afternoon when

They came in to try a landing and were forced out to sea again by a fusillade from all weapons.

But by 4.20 a.m. Captain Johnson, having sent out patrols which found only enemy on the site of Battalion HQ and having tried continually and vainly by other patrols between 1 a.m. and 4 a.m. to get in touch with A, B, and D Companies, concluded that the battalion had withdrawn. He knew that while he held his position he could stop any aircraft from landing on the aerodrome. But he also knew that his small force could not withstand the inevitable dawn attack. Already the Germans shared the airfield with him, holding the western edge formerly defended by 15 Platoon and the bridge end of the southern edge. Their patrols, of about ten men each, were active from dark till midnight all round his positions, on the airfield itself, and on the road towards Pirgos. Johnson therefore decided he must withdraw his men while there was still time. His own account gives a good idea of his method:

(a) At 0420 hrs when I ordered withdrawal I despatched a runner to advise 13 Pl of this order. At the same time I ordered every man to remove his boots and hang them about his neck.

(b) the wounded men who were unable to move were made as comfortable as possible in sheltered positions and provided with food and water and informed that we were about to depart.

(c) At 0430 hrs we moved off in single file, the wounded interspersed along the line of our march, through the southern wire of the copse, past the snoring Germans on our right, through the vineyards which separated C Coy from A Coy’s reserve platoon and HQ area up to A Coy’s deserted HQ, on to the road, up the hill past a grounded glider, until we reached the forward boundary of B and A Coy’s position.

(d) By this time it was getting light and there was no sign of any opposition so I gave orders to put on boots and then we struck east across country towards where I hoped the 21 Bn was situated. On this stage of our journey we picked up two or three sleeping members of 22 Bn who were unaware that any withdrawal had taken place.

(e) By 0600 hrs we arrived in a small wooded area at the same time as the German planes began their morning attack. Here we met HQ Coy under command of Lt Beaven and D Coy under Capt T. C. Campbell. The few German troops on this feature were erased and we stayed put until the worst of the air activity ceased. ...

It will be seen from Johnson’s last paragraph that Headquarters Company had by this time joined Captain Campbell. They had spent a lively enough afternoon in skirmishes round Pirgos but ‘at no time during the night or day had Maleme village been occupied by the Jerries. A few had come through and a few stayed, but only the dead ones.’77 At dusk the enemy had begun to gather

in strength at the post they had captured in the morning. The sergeant armourer, J. S. Pender,78 and Corporal Hosking79 were able to bring into action a small field gun which the enemy had dropped by parachute. ‘ ... when we heard Jerry collecting in this blind spot I spoke about I put twelve rounds into them which quietened them down quite a bit; they were cheeky as hell, shouting out to each other and giving orders, but the field gun quietened them down except that the orders turned to squeals and yells which was very good.80

At 10.50 p.m. Hosking and another soldier set off on a reconnaissance into the B Company area. They got there safely but found no B Company. After returning to report this they set off again and found that Battalion HQ was also vacated. At 1 a.m. Lieutenant Beaven, in the light of this information, began to consider whether he should not withdraw, though loath to do so without orders. Eventually he decided that he must not risk being cut off the next day, and so about three in the morning the company moved out, taking with them their stretcher cases. Shortly afterwards they met Captain Campbell and D Company.

Now that Headquarters, C and D Companies were together, some sort of position had to be manned against the dangers of daylight. Campbell knew the area and led the party to a little valley where trees gave shelter against air observation. Here they waited till the morning blitz had passed its peak. But they had had the bad luck to rouse 21 Battalion’s suspicions – suspicions expressed in bullets. Rather than stay any longer, they decided to cross by companies to 21 Battalion; and this in the course of the morning they managed to do.

Two further groups of 22 Battalion remain to be accounted for: the wounded at the RAP and the pioneer platoon at the AMES. At the time of withdrawal the RAP contained about 160 wounded (among them some Germans), about 70 of whom were walking wounded. Captain Longmore,81 the MO, had been busy all day at his own RAP and at another near the FAA camp. He was ordered in the late afternoon to move east with his patients. With the stretcher cases on boards, and guided by the Intelligence Officer, the party went about half a mile and then stopped to await further orders from Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew. By daylight no orders

had come. The Intelligence Officer set off to get stretchers. He reached the 21 Battalion lines but then decided that the wounded could not be brought safely across the exposed and fireswept ridges.

Longmore and his patients waited on. The German wounded made a circle of RAP gear and the party sat inside it, unmolested by the enemy air force. Attempts were made to contact 22 Battalion and 23 Battalion but they failed. At 5 p.m. The party was captured.

The pioneer platoon under Lieutenant Wadey remained where it was all day and all night, and its further adventures had best be taken up in the next phase of the story.

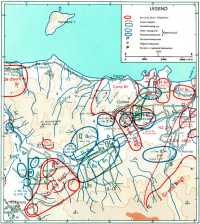

The Other Battalions and 5 Brigade HQ

The preceding account has shown 22 Battalion conducting its battle in isolation and yet continually expectant of counter-attack by one or both of the two units – 21 and 23 Battalions – for which that role was intended. The failure of the counter-attack to eventuate largely accounts for the situation in which Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew found himself at the end of the day, and no doubt contributed to the state of disheartenment in which he made his decision to withdraw, even if it cannot be taken as justifying that decision. It will be necessary therefore to take each battalion in turn and see why no counter-attack took place.

The 21st Battalion had been given three roles, each one excluding the other two. It was to move to the Tavronitis in the event of attack, or to take over the positions of 23 Battalion should it move to counter-attack in support of 22 Battalion, or to remain and fight in its original positions. Just what conditions were to determine which course to be adopted is not now clear. No doubt Lieutenant-Colonel Allen82 considered that he was to hold himself ready to carry out any one of the three and decide, according to the situation or according to subsequent orders from Brigadier Hargest, which was the action required.83

The orders for 23 Battalion were less complicated. Lieutenant-Colonel Leckie84 was to hold his own positions and be ready to come to the support of 22 Battalion if called upon. The onus for providing the counter-attack therefore seems to lie more

specifically on 23 Battalion; and this is what one would expect. For it was the stronger battalion and had indeed been placed where it was because 21 Battalion, much under strength from the casualties it had suffered in Greece, was considered too weak to shoulder alone the task of counter-attack for which it had originally been brought forward. Why, then, did 23 Battalion not counter-attack?

On the morning of the battle the battalion was disposed on either side of the road which ran from the main coast road to Kondomari and the positions of 21 Battalion. East and west across the front lay the canal, and the bulk of the battalion had its company lines immediately south of this canal. On the extreme west of the battalion position was Headquarters Company 1,85 with the battalion mortars and a platoon of MMGs under Lieutenant MacDonald. Between Headquarters Company 1 and the Sfakoriako river was D Company. Between the Sfakoriako and the road was A Company. Right of the road were B Company and Headquarters Company 2. South of all these and in the centre of the battalion position was C Company.86 the RAP and Battalion HQ were in a gully on the southern edge of C Company. A Battle HQ had been prepared in the area of Headquarters Company 1 but the nature and direction of the attack prevented it from being used. Good observation towards Maleme could be had from the high ground held by Headquarters Company 1, and there was observation from a high feature a hundred yards west of Battalion HQ. This feature was occupied by signallers and the Intelligence section.

From these points, and in spite of a much more intense bombing and strafing than usual, the landing of gliders and parachutists over Maleme was observed and reported, though there was no communication with 22 Battalion after seven o’clock, no doubt because the lines were cut. By the time the turn of 23 Battalion itself came all troops were at their stations and as far as possible under cover from the air. Shortly after nine o’clock Leckie reported to Brigade HQ that parachutists were landing between his battalion and 22 Battalion but that so far all was well. In half an hour landings were taking place within the battalion’s own perimeter. In fact the greater part of the Assault Regiment’s III Battalion must have come down there.