Chapter 11: Withdrawal and Evacuation

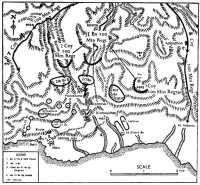

The Ninth Day: 28 May

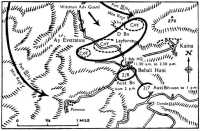

There was jubilation at General Ringel’s HQ on the evening of 27 May and no great disposition to examine the claims of the forward troops too narrowly. Indeed the advance had been considerable: Canea was in Ringel’s hands and Suda, in effect cut off, would soon be his also. Even discounting the claims made by Ringel on behalf of 85 Mountain Regiment to have taken Armenoi, Megala Khorafia and Stilos, and to have reached Neon Khorion, I Battalion had got its main body very close to the Stilos turn-off and II Battalion was established on Point 444, about three miles east of the road running south to Stilos. There may even be some foundation for the more forward claims: a member of Colonel Laycock’s staff reports that while D Battalion was lying up on the main road short of the Stilos turn-off about a company of enemy appeared and, after some fighting, made off again.1 But it seems unlikely that any but the smallest patrols could have got across the Stilos road or to Neon Khorion on that crowded day without being observed.

However that may be, the pursuit was now on and Ringel determined at once to exploit the day’s successes and hasten to the relief of Retimo and Heraklion. He does not yet seem to have realised that these two objects were not identical. For his orders for 28 May were: ‘Ringel Gp will pursue the enemy eastwards through Retimo to Heraklion without a pause. First objective Retimo and the relief of the paratroops fighting there.’

He designed to carry out this intention with his freshest forces. Heidrich’s paratroops were given the relatively easy task of clearing the Akrotiri Peninsula – where the cut-off troops the previous day had made the enemy fight for his progress – and then taking over its coastal defence. Ramcke’s paratroops were to clear Canea and then take over coastal defence as far as Maleme.

For the main pursuit as he saw it, Ringel formed an advance guard under Lieutenant-Colonel Wittmann, commander of 95 Artillery Regiment. It was to consist of the greater part of 95 Motor Cycle Battalion, 95 Reconnaissance Unit, two troops of 95 Anti-Tank Battalion, some mobile artillery and motorised engineers. This force was to be ready to move off before dawn and its task was to drive through to Retimo and thence to Heraklion. Detachments to protect the right flank were to be left west of Alikambos and at Episkopi.

The 85th Mountain Regiment was to push across the road south of the Stilos turn-off and go on via Armenoi and Episkopi to Retimo; 141 Mountain Regiment, with a third battalion which had arrived from Greece that day, was to go via Kalami and Vamos towards Retimo, and 100 Mountain Regiment was to follow. But at Alikambos and Episkopi it was to relieve the flank guards and take over the protection of the whole area to the west and south of Cape Dhrapanon. It was also to clear the road from Armenoi as far as Sfakia and Porto Loutro.

The importance of Ringel’s failure to appreciate the direction of the withdrawal needs no underlining. Had he realised that General Freyberg’s main force was already moving south towards Sfakia, he could easily have brought strong forces to bear and still spared enough to get through to Retimo. But the enemy’s military intelligence throughout this campaign was conspicuously bad, and he must have been to some extent misled by the constant overestimate of opposition that his battalion commanders’ reports contain. Even so, it is surprising that with complete command of the air he was not better informed. No doubt the practice our troops had gained in both Greece and Crete at speedy disappearances from the roads when aircraft were heard, and their compulsory habit of making main moves at night, made it more difficult for the enemy reconnaissance planes than might have seemed possible.

At all events the success of the evacuation was to owe much to Ringel’s faulty intelligence service and his tendency to over-caution – a tendency criticised by General Student.2

It will be remembered that the most northerly troops by the morning of 28 May were the rearguard detachments at Beritiana: the Maori force under Captain Royal, consisting of A and B Companies of 28 Battalion and, with their 130 men, about the strength of one strong company; and the party from Layforce.

According to Colonel Young this was E Company, the Spanish Company, of Layforce.

The commandos, whom Captain Royal found at Beritiana when he arrived, were guarding a road bridge and the high ground west of it. Royal decided to leave them in position, and as he had little doubt that the whole force would sooner or later be cut off and surrounded he arranged an all-round defence, putting one of his companies on the high ground east of the road and the other to cover the southern flank of the whole position. These arrangements were complete before dawn.

About 5 a.m. The Canadian captain who commanded the Layforce detachment reported that ‘the Spanish element’, about sixty men, had disappeared.3 Royal therefore sent his reserve, two platoons of B Company under Second-Lieutenant Pene,4 to replace them.

Hardly was this move complete when a general attack was made against the front. From their positions on the height the Maoris could see that the road from Suda Bay was ‘lined with enemy transport and troops, light armoured vehicles and field guns.’5 This was Wittmann’s advance guard and 95 Reconnaissance Unit which had been ordered to clear the pass. But there was another danger farther south. I Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment had sent a company across the road and round the rear of the Maori position to capture the bridge at Kalami, while the main body of the battalion came out on the Stilos road about two miles to the south.

After the fighting had been going on for some time the Canadian captain and a runner came to report that the rest of his detachment had fallen back.6 This had taken place after the enemy had laid down a heavy fire from guns and mortars. The enemy followed up, driving down the road towards Stilos and capturing a number of commandos on the way.7 At about the same time an enemy company was seen making its way down the Kofliaris Valley towards Stilos – most likely a company of 95 Reconnaissance Unit sent to outflank the Maoris from the east. Thus Royal’s force was virtually surrounded.

As soon as the opposition at Beritiana developed General Ringel had ordered I Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment to come north up the road and take it in the rear. In these orders Ringel expressly told the regiment not to let itself be drawn south. Retimo was

still the objective, and 100 Mountain Regiment would come along later and attend to the protection of the south flank.

When the Canadian captain had reported the departure of his men – he and his runner stayed on with Captain Royal – Royal withdrew his forward troops behind the ridge which they had been manning, and posted a Maori and two Australians, who had joined him the night before, on the right flank with orders to cover the forward slope of the ridge. This they did very effectively.

But Royal could see that he would have to leave before long if his force was not to be overrun.8 About half past ten he sent out his wounded under Sergeant Pitman,9 with men to carry those who could not walk. They were to throw away their weapons and try to persuade the enemy to let them through. After the wounded were gone the main column, including Pene’s two platoons, set off across country. Royal went in front to choose the route and A Company was rearguard. The route was arduous because they avoided mapped tracks and kept as far as possible under cover. One canal had to be swum seven times. They crossed the Kofliaris Valley under heavy machine-gun fire and climbed up its south side. They then headed south-east over the ridges and came out in the Mesopotamos Valley. Here they rested half an hour before going on. Just before they entered Armenoi they were met by bursts of machine-gun fire. Royal formed his men into two columns with tommy-gunners in front and Bren gunners in the rear, and they charged through the village. No doubt the enemy there were weak advance patrols and did not have the stomach to tackle the determined Maoris.

From Armenoi Royal led his men on, still south-east, towards Kaina. The enemy was hot on his heels, and at one point the column halted while the rearguard turned on the pursuers and checked their ardour. Then the column went on again and climbed over more hills under machine-gun fire. Passing Kaina, it reached the main south road about a mile north-west of Vrises at 6 p.m. Casualties for the day had been one killed and six wounded, the latter being all brought out safely.

At Stilos the battalions of 5 Brigade had bedded down after they had got their rations and prepared for the sleep they desperately needed. It is difficult to give an accurate picture of the way the battalions were disposed. But 21 Battalion Group seems

to have straddled the road just north of the village, with 23 Battalion to its front and mainly on the west side of the road. The 19th Battalion was north-west of the village and 28 Battalion west of it. The 22nd Battalion was south-east of 28 Battalion and close to the village.10

Two of the few remaining officers of 23 Battalion, Lieutenant Norris11 of A Company and Lieutenant G. H. Cunningham of D Company, felt uneasy and decided to reconnoitre a little while their men settled down. It was fortunate that they did so, for their inspection revealed a party of enemy emerging from a wadi bed about 400 yards to their front. The alarm was immediately given:

In great haste the troops of the two companies, many of whom had already dropped off to sleep, were summoned to the top of the ridge. They reached the stone wall and began firing from behind it just when the leading elements of the enemy were approaching some 15 yards away. One of the first to arrive and open fire was Sgt Hulme who after the enemy had been repelled the first time was to be seen sitting side saddle on the stone wall shooting at the enemy down on the lower slopes. His example did much to maintain the morale of men whose reserves of nervous and physical energy were nearly exhausted.12

Meanwhile, support was given from 21 Battalion Group, and 19 Battalion had also heard the alarm and come up with a company on the left:

There was a terrific scramble up to the ridge and in places the ascent was almost precipitous. On getting to the top of the ridge we came under fairly heavy mortar fire and there were, unfortunately, quite a few casualties. Some of the enemy had advanced to within 20 to 30 yards of the stone wall which ran right along the ridge like a backbone of a hog’s back and these, of course, were sitters if one cared to take the risk of looking over the wall which, of course, we had to do.13

Finding no way forward to the front, the enemy now sent a party out towards the left who crept close up to the wall and began to throw grenades across. A section of 19 Battalion was sent to deal with this party and arrived in time to despatch an enemy officer and about six men who stood up at the wall with a machine gun. Eventually the attack was beaten off.

The enemy troops in this engagement belonged to II Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment, which came south when it reached the road and indeed must have laagered the night before only a mile or two from the Stilos positions. The fighting seems to have impressed the battalion since the language of the regimental report is stronger even than usual. ‘the strong enemy force at Stylos was taken by surprise by this unlooked-for attack on his withdrawal

route. A terrific struggle developed, including bloody hand-to-hand fighting.’14

At 7 a.m., while the engagement was still going on, there was a brigade conference at which it was decided to extend the line to the left by moving across A Company of 20 Battalion and the Divisional Cavalry. By 8 a.m. this movement was complete, but meanwhile the fighting had spread to the right flank as well and Layforce I tanks could be seen engaging enemy vehicles away to the front.15

The new developments put Brigadier Hargest into some anxiety. After the conference at 7 a.m. a despatch rider was sent to Division with a report on the situation and a message asking Brigadier Vasey to come forward. Shortly after he left, the liaison officer who had been sent the night before came back from Division. He brought an answer, timed 5.20 a.m., to the message sent by 5 Brigade the preceding evening:

We were informed yesterday by Comd Raft [Creforce] that operations for the withdrawal fwd units were under comd Maj Gen Weston and NOT us owing to difficulty communications. Impossible despatch Tp Arty now. We have arranged for 4 Inf Bde to move to ASKIPLIO PLAIN for protection against airborne landings and to hold northern exit to plain where there is strong posn but 4 Inf Bde very weak and dispersed partly against parachutists. Understand amn and rations also supplied to you from DID south of STYLOS. Major Leggat has only 30 men and has joined 4 Inf Bde. Location remainder 4 Inf Bde unknown. All other tps moving through here have been ordered to SPAKIA. As soon as light enough establishing an HQ close to southern exit ASKIPLIO PLAIN.16

Brigadier Hargest answered at once:

Received your note at 0735 hrs. My position is now serious.

We held line yesterday subjected to heavy bombing and heavy ground attack which we repulsed.

Extracted ourselves last night arrived here before dawn. Left two companies at top of pass at Beritiana but owing to infiltration from the right they are cut off.

No other tps except 19 Aust Bde are of any use to us.

We will endeavour to hold small position here today and move back tonight but owing to exhausted state of tps this will be very difficult.

We will do our damndest but look to you to give us all the assistance you can.

We would still like you to send up the guns.

Reported that great number of Italian prisoners moving along road from rear towards us – estimated 1000.17

The column of Italian prisoners referred to in this message added a touch of painful farce to the situation. They were troubled by mortar fire from the Germans and at the same time got very unfriendly looks from the New Zealanders. Eventually Hargest let them through because of their nuisance value. Trigger fingers itched as they passed on and finally disappeared with loud shouts towards the enemy front.

Meanwhile Brigadier Vasey had come forward in answer to Hargest’s message. He had already seen General Weston about four o’clock that morning and told him that the two brigades intended to lie up that day and go on after dark. Weston does not seem to have been able to improve on this programme but took the opportunity to enlighten Vasey on the role and organisation of Layforce.

After the two brigadiers had conferred, the battalion commanders were called together about 9 a.m.:

At 9 we met. The alternatives were simple. Would we risk staying and becoming engaged in battle and so surrounded or would we march out in daylight in view of the Hun planes and their ground strafers.

The COs were divided. Vasey was for marching.

I put the question to each in turn.

Can you fight all day and march all night tonight if we can extricate ourselves?

The answer was, ‘No.’

Well, we’ll march at 10.

Vasey agreed to cooperate. His troops were well on the way there. He would hold a side road.18

Lieutenant-Colonel Dittmer indeed had objected. ‘OC 28 because of two of his Coys being at junct of the coast and STILOS rds stated at Conference that the remainder of his Bn would take a dim view of pulling out and leaving A and B Coys high and dry.’19 But Hargest said they were cut off in any case and he was trying to get a message through to them.

This message went off by despatch rider at 9.15 a.m.:

You will withdraw forthwith moving back under as much cover as possible on both sides of road. Move back via main STYLOS Rd if possible to rejoin parent unit. Parent unit is moving back from STYLOS via main road some time today.20

According to both Brigadier Hargest and Captain Dawson, some carriers and a tank were also sent off about this time to try and relieve the rearguard; and the despatch rider probably went with

Them.21 This attempt to get through to Beritiana failed, not surprisingly since the enemy now had many troops and guns along the road.

Meanwhile arrangements went ahead for the withdrawal of 5 Brigade. The 2/7 Battalion, from its positions south of Stilos, was to cover the rear of the withdrawal while 2/8 Battalion went south from Neon Khorion to strengthen D Battalion at Babali Hani. While 2/8 Battalion was getting into position 5 Brigade HQ would hold the Babali Hani crossroads in front. The 5th Brigade units would pass through this screen and reassemble behind 2/8 Battalion; 2/7 Battalion would then follow.

Although his men were exhausted, Hargest had good hopes that if he could get them clear they would be able to march as far as Vrises and hide up there before the heat of the afternoon set in. At 10 a.m. Brigade HQ moved off, passed through 2/7 Battalion and then Layforce, and reached the crossroads. The battalions followed at intervals, 21 Battalion Group covering them until they had passed through 22 Battalion and then itself following. Just before withdrawal began 23 Battalion sources report that the enemy again began to attack and it was thought that a counter-attack would have to be launched. But at the critical moment ‘shouts, hakas and yells were heard from the rear of the Germans who suddenly ceased attacking and withdrew in some confusion.’22 According to this account the new arrivals were a strong party from Captain Royal’s detachment who had been sent back with the wounded. Royal, however, says that he had told the escort and the wounded to throw away their weapons. We must assume either that they had acquired fresh weapons on the way or that they had been joined by parties from A Battalion or by men who had had to fall out on the march but who were now ready to make a further bid for freedom.

In spite of the difficulties of getting the companies back from their deployed positions, all went well and soon the column was on the march, the troops marching in single file on each side of the road with the sections well spread. Hargest rode up and down in a Bren carrier to see that all was going well. He then went on ahead to the crossroads and waited:

At last they came, fast but together, keeping to the sides of the road – thirsty, almost exhausted, but they kept on – they knew the issue. We spelled

Babali Hani, 28 May

them at water points and the promise of a long rest heartened them. They were magnificent.23

After a brief rest south of the crossroads the battalions moved on towards Vrises. The last to arrive was 21 Battalion Group which passed the control post at the crossroads at 1.40 p.m. Then 2/7 Battalion came back and 5 Brigade HQ was relieved by 2/8 Battalion, which had been assembled about a mile to the south and now came forward to assist Layforce.

The road thus sealed behind them, 2/7 Battalion and 5 Brigade marched on towards Vrises. The feeling among the men was beginning to spread that this day and march were also to be long ones. ‘We are tired and our feet are sore but by now we realise that this is going to be some job and nobody talks much but settle down doggedly to conserve energy and keep up with the party.’24 the stragglers from the parties which had gone on before were grim enough evidence that the going would be hard.

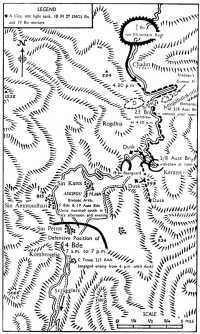

Layforce’s D Battalion was disposed just north of the Babali Hani crossroads. There were no digging tools and the men had to make sangars for themselves out of stones taken from the walls thereabouts. Owing to the absence of the Spanish Company (E Company), Lieutenant-Colonel Young had only four companies

to cover a front of 2500 yards – the width of the valley which he was trying to block. Even stretching his front as far as possible he could cover only about 1000 yards. He therefore put A and D Companies on the right of the road, with a front of about 500 yards and the right flank fairly secure because it rested on rising ground. B and C Companies he put to cover about 500 yards on the left of the road, with their left flank more or less open. In reserve he put a troop of A Battalion which Colonel Laycock had put under his command that morning, together with one of the I tanks.25 the 2/8 Battalion was in reserve.

From midday onwards there was a good deal of mortar fire, and then, about half past one, after the withdrawing troops had passed through, came the first attack. It fell on C Company, the company just west of the road. For half an hour the enemy tried to break through and everywhere he was repulsed. Then the fighting died down again. About half past three heavy mortar and machine-gun fire heralded a second attempt, again on the left flank but threatening to move round it as well. Young used every man he could to extend his flank and asked 2/8 Battalion to assist with its two companies. These, a counter-attack by B Company, and the I tank which kept making sorties up the road, enabled the line to hold. It had been touch and go; for now that the Australians were committed Young had only the troop from A Battalion in reserve.

The first enemy attack had come from the joint force of Wittmann Battle Group and II Battalion, 85 Mountain Regiment failure forced the committal of the whole Wittman Battle Group in the second attack. ‘the enemy’s actions pointed to his intending to hold his positions at all costs at least until the evening and then withdrawing under cover of darkness. He even made small counter-attacks from time to time, and often the fighting came to close quarters. Observation was too poor for our artillery to be effective, and our tanks had not yet arrived, and so we had to desist from attacking, as it would have been too costly under the circumstances.’26

The enemy now planned a two-battalion attack by 85 Mountain Regiment at dusk. But the attack arrived too late. For during the afternoon the defence had received its orders to withdraw at dark and about 9.15 p.m. The battalions began to pull out. Their stubborn stand had made the withdrawal of 2/7 Battalion and 5 Brigade a much less hazardous affair than it would otherwise have been.

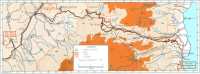

Babali Hani was the last engagement fought on 28 May and the last defensive position to be held north of the White Mountains. But to the troops making for the south coast these mountains were an obstacle so formidable as almost to rank as a second enemy. From Stilos to the Askifou Plain – the next main halting place – is a distance of only about 15 miles by road. But a glance at the map will show that that road leads upwards all the way; from less than 300 feet above sea level round Stilos it climbs until it passes, by constantly more tortuous zigzags, hairpin bends and serpentines, through mountains which are not the highest of the range but which are, at the crown of the pass, over 3000 feet.

For fresh men even in peacetime to cross this barrier would have been an exacting march. It came now as a cruel culmination to a battle which had ended in defeat; and not to be able to cross it was to become a prisoner. For two days and two nights men had been streaming over it, some crammed into the few vehicles that were still functioning, the rest marching, stumbling, and at times reduced to crawling on hands and knees. The natural savage grandeur of the mountain road was overprinted with the chaos of war. Every yard of the road carried its tale of disaster, personal and military. The verges were strewn with abandoned equipment, packs cast aside when the galling weight had proved too much for chafed skin and exhausted shoulders; empty water bottles; suitcases and officers’ valises gaping their glimpses of khaki linen and pullovers knitted by laborious love in homes that the owners might not live to see again; steel helmets half buried in the dust; all the grotesque and unpredictable bric-a-brac of withdrawal, the personal property treasured till it became an impediment and then discarded so that its owner could keep up with his desperate urge for life.

Every here and there, too, were trucks which had gone on as long as they could, heavily overloaded, and then had broken down for lack of petrol, leaving their occupants to bundle out and, without their packs, trudge upward on foot. Other trucks had crashed over steep cliffs in the dark and lay on their backs below the road, wheels in the air like the legs of tumbled beetles. Others again, their metal scored and scarred, lay at the side of the road where they had been pushed after the bomb or the bullets had struck them.

These things were the commonplaces of the withdrawal, scarcely calling for a glance from the men who trudged by, heads down and shoulders stooped, each one intent on enduring the thirst that tormented every mile of the march, on eluding the enemy aircraft

that swooped from time to time and raked the road, and above all on climbing the vast range with its interminable series of disappointing false crests that were crossed only to reveal a further and higher ridge above. From each individual purgatory of parched mouth, panting lungs, straining back and raw feet there were few who could look out with more than apathy at the occasional corpse that from beside the stony path looked up at the sky with unclosed eyes, at last resting.

By day the road was not so crowded. The need for sleep and the fear of enemy aircraft kept many prostrate in the olive groves or whatever shelter could be afforded by rocks and scrub. Only a few knots and bunches of men, whose anxiety to reach the sea was greater than their fear of bombs, kept climbing in the sweat and dust of the day. At dusk, however, the troops, some in organised groups and taking pride from one another’s company, others alone or in twos and threes, their units lost and themselves reduced to the anarchy of isolation, stirred from their shelters and made their way to the road. And as the night wore on an occasional flare from an enemy aircraft would reveal, as far as an eye could reach, the long column winding like the road from darkness into darkness and at such a moment stationary, waiting to see whether a bomb would follow and where it would fall.

In such a time men revert to what their natures have kept below their training. Trucks would pass ruthlessly along the column, ignoring the appeals of wounded men who would not fall out while their legs assured them that they might still be free. Or sometimes a truck would stop and one of its occupants would gruffly get out to make room for a man on foot whose condition was so bad that the passenger could not bear to ride while he walked. And of those who marched some went stonily on, ignoring the appeals of companions who could go no further; while others showed an awareness of something greater than their own exhaustion and did their best to struggle forwards, a wounded companion slung on a blanket or a broken stretcher between them. And time and again the sight of a man stumbling along with an arm round the neck of each of two comrades who took turns carrying his rifle stressed its echo of Calvary.

Over this terrible pass on the night of 27 May 4 Brigade and the various units of the Composite Battalion had gone on already, men like Lieutenant-Colonel Gray of 18 Battalion – with that stamina which owes its strength to concern for others – marching back and forth along the column of their units, infusing strength by example and somehow carrying their men forward as a unit still, ready if the need came to throw off weariness yet again and

fight as an organised force.27 the 20th Battalion, too, had been like itself: ‘ ... along came the 20 Bn with Kip marching under extreme difficulties at the head of them. It was really good to see a unit still under perfect control, retiring in an orderly and well organised manner thanks to Kip’s good discipline (no rabble or rafferty rules about this outfit).’28

The men of the Composite Battalion did not have the advantage that the infantry battalions possessed; for their unit had been formed only for the defensive action at Galatas and they were not trained infantry. At the beginning of the march the battalion had virtually broken up into its component groups. But the officers and the NCOs who led these groups behaved with great devotion, and the men under them stuck loyally to the road even when the supreme test of the White Mountains loomed before them. Thus Major Veale, sending the men with bad feet on in front, collected the rest of his group and before starting told them: ‘Tonight you’re going to march as you’ve never marched before. I’ll set the pace and you’ve got to keep up.’ When they reached the top of the pass at 2.30 a.m. on 28 May they had marched for more than seven hours, stopping five minutes in each half hour.

In much the same way the gunners also crossed, having disabled and abandoned their guns at the foot of the pass. Here again individuals like Major Bull, to mention only one, showed the resolution of the good commander in adversity and succeeded in keeping the pattern of discipline that in such times dissolves so quickly and leaves the breeding ground for panic.

Towards this terrible crossing, after they left Stilos, the men of 5 Brigade were headed. Few of them had any idea of the distance that still lay between them and the sea or of the demands that the White Mountains had yet to make on them. Their minds were set rather on the immediate problems: whether they would get the promised rest at Vrises, whether there would be a chance to fill

Their water bottles, whether and how soon they might have to fight again.

On they went, past men who had fallen out and now sat on the verges of the road with head in hands or lay sprawled a little to the side. For all their weariness the units kept together, marching briskly and passing small groups less inured than themselves but still struggling to get on. About 3 p.m. They came to Vrises – ‘a row of brickdust’, as Captain Snadden describes it, after days of bombing. There they were able to drink all they could drink and fill the water bottles that had to be so carefully nursed along the march. There, too, the enemy aircraft which had not troubled them so far that day appeared and kept them alert as they lay wherever there was grass and shelter.

But the rest was not to be for long. At half past five Brigadier Hargest issued a new movement order. Brigade HQ, 19 and 23 Battalions were to leave at 6 p.m., 28 Battalion at 6.15, 21 and 22 Battalions at 6.30. On reaching Amigdhalokorfi, at the top of the pass over the White Mountains, 23 Battalion was to take up a line through which the other units would pass. It would hold that line till further orders. The two Australian battalions would also be passing through and ultimately British troops would probably take over. Meanwhile every effort would be made that night to get the head of the brigade to Sin Ammoudhari.

Of all the troops who crossed the White Mountains none had a more gruelling time than 5 Brigade. Few men in it could say they had had anything like a night’s sleep since the battle began nine days before. Almost the whole of the brigade had been engaged in the fighting on 26 May, 23 Battalion on 25 May as well. The night of 26 May had been spent on the march back to 42nd Street, the day of 27 May in the fighting there. Then they had marched all night, only to find themselves fighting again on the morning of the 28th. Since then, apart from the rest at Vrises, they had been marching again. And now before them lay the White Mountains. To men in the last stages of exhaustion, sleepless and weary from fighting and marching, marching and fighting, it was to be a supreme test of endurance.

We pass all sorts and conditions of folk. Among some Greek airmen a very pretty blonde, a Greek nurse, looking strangely incongruous in all this wild assemblage. The road gets worse and it is little more than a cart track. We are near the summit of the foothills but it is not till dusk that we reach the foot of the Pass. Halts are infrequent. There is still a trail of littered equipment, arms and vehicles and occasionally a ‘stiff ‘un’. We seem to be standing in a treadmill and the world goes past us. We are senseless to all feeling.29

In these days of grim withdrawal after withdrawal and forever being brought to bay, Brigadier Hargest had found in himself resources of energy which he lavished in care and concern for his men. The night of this march was one which he would not easily forget.

Never will I forget it. As the sun fell the men struggled upwards lame and sleepy even after their rest but the road surfaces were galling them. Near Vrises there is a huge incline, steep and ending in a pass – near it was a rocky eminence which had been prepared for demolition by the RE. Just after we passed some fool ordered its explosion and up went the road in front of our tired troops and the Aust.30

No doubt the road was blown by one of those errors that are explicable enough in the haste and confusion of withdrawal – a time too rigidly adhered to, a mistaken belief that all the troops to come have crossed. But to the troops on whom it forced a serious detour it was a maddening exasperation; for by now each man was reckoning his stamina in terms of yards, of the next large rock, or the top of the next rise, or the next halt at which he had promised himself a pull from his water bottle. And here, by what would seem the act of a lunatic, were hundreds of yards of difficult extra going thrust upon them. Thus 21 Battalion Group, which reached the demolition at 9.45 p.m., had not finished getting round it till half past eleven. Moreover the demolition, besides adding hours to the agony of the marching men, meant that no more vehicles could cross. From now on they would have to be destroyed at the foot of the pass.

Here at the foot of the pass was the last well until the other side was reached. For all the troops who had already passed, the few wells had been prayed for long before they were reached. And at them the observer could soon have seen whether the troops there were units still under discipline or men broken into a mere aggregate of individuals. There had been ugly scenes at times where the latter was the case. If the original lifting device – a long pole – was still in place things were not so bad. Water bottles could be filled quickly and a turn could be had without waiting too long. But in many wells the pole was absent and men had to fill their bottles by lowering them on equipment straps or pull-throughs tied together, a clumsy and slow operation. The circumference of the well mouth would be crowded with parched troops and others pressing behind them for a place; and the water often would hardly have reached the rim when overeagerness or a jostling rival would have spilt it.

With organised units like those now passing, however, it was different, and there were officers and NCOs to see that each man had his turn, especially as this well was the last.

The water here is dirty and tastes of petrol, giving us all the hiccoughs. We drink and fill our bottles. We rest for half an hour and then start our climb. It seems endless. We have been warned that our bottles must last for the whole of the next day. The average is half a bottle per man and we are to spend the next day at the top of the pass as rearguard. The going is rough. At one halt a man lights a cigarette and a Sgt. gives him the sharp end of a tin hat over the ear. He curses as his smoke is knocked out and over into the gorge. We climb up and up and below us spreads the country we have traversed at such speed. At some forgotten hour in the night we are halted.31

The responsibility of battalion officers and NCOs in this march lay heavy on them. They had the advantage that they had to keep themselves going in order to give an example to their men and so had little time for the debilitating luxuries of self-pity. But they had also to be, as it were, simultaneously at the head of their men to set the pace and at the rear to see that no straggler was lost through lack of incitement to go on. And going up and down the columns they had to support the sight of the terrible condition of the men who had fought under them so enduringly in the long days and nights that lay behind. How harrowing this was may be gathered from the description by Lieutenant Cockerill:

Unfortunately during this march many men dropped by the wayside. For a time the troops helped their comrades along who were too weak to make the grade but it was quite obvious that this would prove to be impossible for the distance and they were made as comfortable as they could be on the side of the road with one or two water bottles. I have no doubt that most of these were picked up although some did escape into the hills. Lots of the men, through not having been able to bathe and wash their clothes, found that the chafing was becoming very serious and, in very many cases, we could see the humour in soldiers walking along with arms over their shoulders and no trousers on. ... It was pitiful in some cases to see the men come in, especially in one or two cases, more or less on their hands and knees.

Eventually, after many weary hours, discipline and determination conquered. Each battalion in turn reached the top of the pass. The 23rd Battalion left the column and took up a defensive position as best it could in the dark, with D Company on the left of the road, Headquarters Company, A Company, and the detachment of gunners under the indefatigable Captain Snadden on the right. ‘We have never slept on such boulders but it might as well be a feather bed; it makes no difference.’

The other units marched on through the night and down the other side of the pass, reaching the Askifou Plain at dawn, the Maori Battalion impressing all who were there to see it with the untroubled unison of its march.

Fourth Brigade’s units had taken until midday of 28 May to forgather in the Askifou Plain and take up their anti-paratroop role. The light tanks arrived there shortly after daylight. During the morning Division warned Brigadier Inglis that his battalions were to guard the northern entrance to the plain and might have to go on doing so as late as darkness on 30 May. The 18th Battalion was therefore put into position at the north end. Fourth Brigade at 4.40 p.m. issued a formal order to 18 and 20 Battalions. The brigade was to remain in position until 5 Brigade had passed through. It was expected to begin doing so that night. The main body of 18 Battalion was to remain near Sin Kares, but a detachment of about fifty men was to be sent after dark to hold the head of the pass about a mile west of Kerates. This detachment would remain there until ordered to move by 4 Brigade HQ. From 11 p.m. it would have a light tank under command. The 20th Battalion was also to remain in its present positions but was to reconnoitre the southern exit from the plain and be ready to move there on getting orders from Brigade HQ.

An order to the commander of C Squadron was also sent at 5.8 p.m. covering his part in the rear detachment. One of the remaining four light tanks was duly sent but, presumably because of a change in orders, neither the 18 Battalion detachment nor the tank went out until dawn next morning.

Creforce HQ had established a control post at the south end of the plain, and here officers were trying to break the continuous stream of stragglers into groups of about fifty. So far as was possible the officers of the former Composite Battalion were still trying to keep their men together, a task of almost superhuman difficulty with so many men on the road and all the confusion of many mixed troops withdrawing in various stages of exhaustion. Darkness very often broke up the groups that were formed by day but none the less they kept some semblance of unity, Majors Bull and Bliss being prominent among the officers; and other groups like 5 Field Park Company, the RMT, the Petrol Company, and the Supply Column also managed more or less to keep together.

The only guns by now were those of C Troop 2/3 Regiment RAA which had been got as far as the Askifou Plain and were put under command of 4 Brigade. Those of F Troop 28 Battery had had to be put out of action at the foot of the White Mountains, there

being practically no ammunition to make it worthwhile towing them farther. From the time they had overshot the forward brigades at 42nd Street, there would have been little hope of getting them back against the stream of retreat even had the ammunition been available or communications permitted the passage of orders.

The New Zealand medical units which had moved to Kalivia during the night of 26 May had had to move again on the night of the 27th in order to get as far as possible on the road towards Sfakia. The trucks carrying stretcher cases went straight through to Imvros, where a main dressing station was established by 3 p.m. on 28 May and under Lieutenant-Colonel Twhigg’s32 able direction soon became a very efficient unit.33 Two walking wounded collecting posts were also set up: one about a mile south of Imvros under Captain Lomas,34 and the other under Captain A. C. Rumsey of 189 Field Ambulance at the end of the formed road. Both were staffed from 5 and 6 Field Ambulances.

The trucks passing along the roads had improvised Red Cross flags from red and white hospital blankets and these were respected by enemy aircraft. But when they attempted to go back over the pass and collect more wounded from Lieutenant-Colonel Bull’s dressing station at Neon Khorion, they found that they were unable to do so because of the demolition already mentioned. Even had they been able to get back, however, they would have been too late; for Bull, his small staff, and some thirty seriously wounded men were captured during the afternoon.

The walking wounded who kept filtering across the pass all night and day were mostly scattered in the hills at the northern end of the Askifou Plain, though there were some sheltering under trees at many points between there and Imvros.

Meanwhile arrangements were going ahead for the evacuation of wounded that night, when Creforce had decided that they and medical staffs should have priority. Preliminary arrangements were made by Major Fisher with Lieutenant-Colonel Strutt and Lieutenant-Colonel W. E. Cremor, now in charge of embarkation, while Major

Christie and Major Palmer35 reconnoitred the beach – it could be reached only by a precipitous goat track from Komitadhes – and found that Creforce HQ had arranged for an assembly area about two miles from the embarkation point and that 189 Field Ambulance had established an RAP there.

When he reached Sin Ammoudhari on the morning of 28 May Brigadier Puttick’s first concern had been for 5 Brigade. But there was nothing he could do to provide them with the guns they needed and little he could do to help in any other way.

Late in the morning the operational directive which Creforce had drawn up the day before36 was received, and no doubt it was as a result of this that 4 Brigade was given its orders to hold the north of the pass.

The first reliable news of 5 Brigade seems to have come from General Weston, who visited Division at 3 p.m. and reported that 5 Brigade was making a daylight withdrawal to Vrises. Puttick was able to inform him in return of 4 Brigade’s dispositions and also to offer him any help in his power, including the loan of his staff. Weston took advantage of this offer only so far as to borrow Lieutenant-Colonel Strutt to organise dispersal areas on the hills above Sfakia and the despatch of parties to the beach.

At 9 p.m. Division moved farther south and just below Imvros. Before the move a further discussion was held at which it was decided that both 18 and 20 Battalions would move next morning to the south end of the plain and cover the further withdrawal of 5 Brigade. But the plan of leaving a rear detachment of 18 Battalion was adhered to.

General Weston had been able to force his way upstream against the traffic as far as Brigadier Vasey’s HQ at Neon Khorion very early on the morning of 28 May, and was there given a picture of the general situation as then known and the plans of the two forward brigadiers.

There was little Weston could now do but rejoin his HQ, which had gone on to Sin Ammoudhari and had arrived there at 7 a.m. During the day it moved on to Imvros, attending among other things to the extemporisation of a battalion of Royal Marines to

carry out the tasks laid down in Creforce’s operational directive which Weston no doubt received on his return. Now that the brigades were coming back into a single area there was for the first time a prospect of his being able to carry out the role of co-ordination assigned to him when withdrawal began; and it was in preparation for this that he visited Brigadier Puttick’s HQ during the late afternoon.

At three o’clock in the morning of 28 May Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell’s Australians at Retimo had once more attacked Perivolia. In spite of the fact that the Greek troops helping to cover the two companies of 2/11 Battalion opened fire against orders and thus gave the enemy the alarm, the attack went well and the Australians fought their way right through the village, killing about eighty enemy and destroying a number of machine-gun posts. But all the officers of D Company except one became casualties and the company withdrew. B Company, the other company engaged, was thus left isolated and was forced to withdraw also.

Meanwhile General Freyberg had discovered with chagrin that Lieutenant Haig had left the night before, too soon for the message about evacuation to reach him.37 At 8.25 on the morning of 28 May, therefore, he signalled General Wavell that the orders had not got through and that there was no cipher by which so important an instruction could be passed by wireless. He asked that his message of the day before, of which he gave Wavell the text, be dropped to the garrison, preferably by day, together with £1000 in drachmae in case they should be useful. He also explained that, as his own HQ had moved to Sfakia, he was not yet in wireless contact with Retimo and was not certain that he would be able to establish it and be able to send messages even in the garbled code that was safe enough for less important signals. And so he asked that Middle East should also relay by wireless in this code a

further message to the effect that an aeroplane would be dropping something at 1.2 p.m.38

When the wireless at Sfakia was working Freyberg also had the code message sent out to Retimo from there. But from the time of the break in communication the night before, Retimo was unable to pick up any further signals from Creforce, perhaps because of the mountain barrier that lay between the two.39

Wavell meanwhile had received Freyberg’s signal and replied that he would pass it on to Retimo together with the money, but that nothing could be done till early next morning. Wireless contact between Middle East and Retimo was now re-established and the second code message passed with the comment that it was probably too late since the time was by now 6 p.m. Wavell therefore asked Freyberg to prepare another code message by which Retimo could be warned that messages and money would be dropped before seven o’clock next morning.

In a second message General Wavell sent a code which could be used in clear for messages between Creforce and Retimo and a copy of which would be dropped to Retimo with the other messages next morning. Acting on the first of these two instructions – which must have reached Creforce very late since the reply is dated 29 May – Creforce replied in guarded language with a message for Retimo to the effect that messages were being dropped before breakfast. Retimo was asked to acknowledge receipt of the message to Middle East.40

This message was not received at Retimo, and the result was that the garrison still had no news of the evacuation or their part in it.

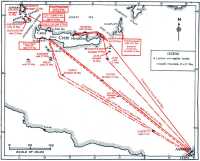

At Heraklion on 28 May Brigadier Chappel held a conference and gave his orders for the evacuation so that his officers could get on with their preparations. These included aggressive patrols to blind the enemy to what was afoot.

The orders to go had been none too soon. The enemy flew in a substantial number of reinforcements during the morning, dropped more supplies, and showed signs of offensive intentions. No doubt he was well posted with news of the victories elsewhere on the

island and was preparing an attempt to show the expected relieving troops that he had not been idle either.

According to plan Chappel’s troops began to withdraw through an inner perimeter held by 2 Leicesters at 10 p.m. Unfortunately the presence of strong enemy forces between the British and the Greeks prevented news of the withdrawal being got through to the latter. It is doubtful whether any Greek troops could have been taken off, however, as the shipping programme allowed for only 4000 and there were 4200 British troops.

Orion, Ajax, Dido and six destroyers had been on their way from Alexandria since morning and had run into air attack from five o’clock in the afternoon. Ajax received some damage and was ordered back to Alexandria after dark, but the rest of the ships were off Heraklion at half past eleven. The destroyers then entered the harbour and ferried troops to the cruisers. By 3 a.m. all were aboard, except for the wounded who had to be left behind and a detachment guarding a road block, and the convoy sailed.

Early on 28 May General Freyberg’s staff on Creforce issued the formal evacuation order, addressed to General Weston with copies to the other parties affected. It confirmed that all troops were under Weston’s command for operational purposes while it assigned to Creforce HQ responsibility for evacuation arrangements. It laid down the evacuation programme already sent to Admiral Cunningham: 1000 to be taken off that night; 6000 the following night; 3000 on the night of 30 May; and 3000 on the night of the 31st.

The order assumed that 5 and 19 Brigades, both probably exhausted, would with Layforce withdraw through the Askifou Plain area now occupied by 4 Brigade; and it therefore stated that they should be withdrawn straight to the assembly area if the tactical situation allowed. In preparation for this Weston’s Royal Marines were to be put into a defensive position south of the plain and Layforce, or part of it, should be put under command of 4 Brigade.

The enemy could be expected to make contact with 4 Brigade in the afternoon of 29 May. The brigade would therefore hold him off till dark that night and then it was hoped that, with Layforce, it could withdraw straight to the beaches, where Layforce would revert to Weston’s direct command. This forecast would have to be reviewed as the situation developed.

The enemy was expected to follow up 4 Brigade’s withdrawal and so bump against the Royal Marine positions at the south end

of the plain on 30 May. The Marines would have to hold him off till dark that night. As that same night was the night when it was hoped to embark 5 and 19 Brigades, the Marines and Layforce would also have to hold a delaying position on 31 May. They would disengage after dark and be embarked that night.

It had been laid down that fighting troops would embark first and that the wounded and those who had fought longest would have priority. There was a chance that the programme might be expedited and the need for a delaying position between the south end of the plain and the sea not arise.41

On the same day the DA & QMG of Creforce, Brigadier G. S. Brunskill, issued an instruction on embarkation arrangements. By this General Weston was made responsible for the flow of troops to the beach and for the establishment of a suitable assembly area. It laid down that only organised parties travelling from the assembly area by a specified route were to be embarked and that parties given particular tasks on any one night should have priority of embarkation the following night. It allotted numbers for that night’s embarkation: 200 wounded, 10 seamen, 100 RAF, 50 Cypriots, 640 Coast Defence AA, and fighting troops not required for defence – all in that order of priority. And it concluded with some administrative arrangements about transport and walking wounded.

While his staff were issuing these orders General Freyberg and Brigadier Stewart were still on their way towards Sfakia, which Freyberg was very anxious to reach so as to use the RAF wireless there for contact with General Wavell. He reached the advanced HQ which had been set up by Colonel Frowen in a cave some time during the morning.

There was a worrying time at first. The RAF wireless was short of batteries and the naval and military sets still surviving had not yet arrived. No contact could be made with Middle East. Eventually, however, messages could be got through, and the first to be sent dealt with the problem of getting orders to Retimo.

By midday enough news from the front had filtered through for Freyberg to be able to report on the tactical situation. He explained that it had been impossible to disengage completely and it seemed unlikely that they would be able to hold out until the night of 31 May. Only the New Zealand and Australian infantry were able to form military bodies capable of fighting; and an optimistic view of their numbers would be under 2000, with three guns (limited to 140 rounds of ammunition) and three light tanks to support them. There were large numbers of unarmed stragglers,

but he proposed to concentrate on embarking armed troops next night – which he feared might be the last night possible. Any left over he would tell to make their way west towards Porto Loutro and Franco Kastelli (Frangokasterion). He asked that everything possible should be done to expedite the embarkation.42

In the evening General Freyberg dictated a message which Lieutenant White,43 his Personal Assistant, was to take off that night. In this message Freyberg stressed the role of the enemy’s aircraft in the defeat of the defence. It had thwarted all counter-attacks, broken up defence positions, and made tanks incapable of effecting anything. The ground troops of the enemy and his parachutists had all been dealt with effectively enough, but the enemy’s strength in aircraft prevented any permanent result. General Freyberg’s own troops were disorganised on arrival from Greece and the Greeks had been without adequate equipment. But the troops had fought well and could not be blamed for the failure. The difficulty was now that of the evacuation and Creforce was hampered by lack of transport, communications, and staff.

Having dictated this message Freyberg set off in the closing stages of the evening to visit General Weston and Brigadier Puttick.

On the beach itself preparations were being made for the embarkation of the 1000 men. There were to be four destroyers – Napier, Nizam, Kelvin and Kandahar – and these arrived about 10 p.m., bringing extra boats to help with the embarkation and a supply of rations. All walking wounded in the assembly area – some who had walked right across the island in spite of severe wounds – were got forward, about 300 in all. There was some scrimmaging and jockeying for place by the stragglers who had managed to evade the control posts, but all the wounded except about seventy were got on board, together with 800 men from the Suda Area, including the RAF contingent. At 3 a.m. The destroyers sailed.

Behind them there was still work to do. Not all of the rations brought were of much use – there were cases of matches and bags of flour – but everything had to be moved under cover before daylight brought the enemy reconnaissance aircraft. This took time; but when dawn came the beach was clear once more.

Withdrawal Routes to Sfakia

The Tenth Day: 29 May

The rearguards had been lucky to disengage successfully at Stilos and Babali Hani on 28 May. For, apart from the fact that 85 Mountain Regiment and Wittmann’s advance guard were preparing to encircle the latter position, 141 Mountain Regiment reached Vamos during the afternoon and sent a company south through Vrises to take the Babali Hani position in the right flank; and 100 Mountain Regiment was also now arriving. It was fortunate for 5 Brigade, 19 Brigade, and D Battalion that they were clear on the other side of the White Mountains by next morning.44

The relative peace from air attack on 28 May was also something to be grateful for and may be attributed largely to the causes which had already been diminishing the enemy air effort for a day or so, though in part to General Ringel’s infatuation with Retimo. For on 29 May Ringel’s forces were ordered to continue carrying through the orders issued on the night of the 27th. The advance guard, 85 Mountain Regiment, and 141 Mountain Regiment were therefore to go no farther south but to push east and then north towards Retimo. Only 100 Mountain Regiment was spared for operations in the south where the true opportunity for frustrating evacuation lay.

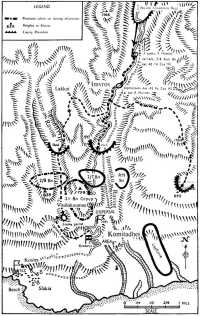

With 23 Battalion covering the road in a strong natural position at Amigdhalokorfi and the two Australian battalions to the immediate rear, there was no immediate danger on the morning of 29 May that the enemy might rush the Askifou Plain. As a further precaution A Company of 18 Battalion, supported by one of C Squadron’s light tanks, had been sent to cover the entrance to the plain about a mile west of Kerates. From here it would also be able to aid the withdrawal of 23 Battalion when the time came.

For the first time since the withdrawal began the various commanders were now able to meet and confer about plans for the final stages. The main conference, at which General Weston, the three brigade commanders and Brigadier Stewart were all present, took place in the early afternoon. Here it was decided that 4 Brigade should concentrate at the southern exit from the plain and hold it till nightfall, when it would retire to the beaches;

5 Brigade would also concentrate and move to a dispersal area near Komitadhes; Layforce – D Battalion and remains of A Battalion – would take up a defensive position near Komitadhes and cover the exit from the Imvrotiko Ravine; 19 Brigade with its three guns would move into a rearguard position near Vitsilokoumos and be there by nightfall, the Royal Marine battalion, the tanks of 3 Hussars, and the last three Bren carriers of 2/8 Battalion all coming under command.

A timed programme was issued. Fourth Brigade would march to the beach at 11 p.m.; 5 Brigade, except for 23 Battalion, would trickle forward from 1 p.m. to 7 p.m. in small parties widely spaced; 19 Brigade would begin the march to its new area at 9 p.m.; the Royal Marine battalion (and presumably Layforce) would move from its position near Kombroselia at 10 p.m.

The orders also stated that General Weston’s HQ and Brigadier Puttick’s would both move that night to the beaches west of General Freyberg’s HQ. And it was specified that the orders assumed that embarkation would be completed on the night of 30 May. Should another night be required, 19 Brigade and the Royal Marines must be prepared to hold the rear for another twenty-four hours.

Fifth Brigade expected no difficulty in carrying out these orders, unless in extricating 23 Battalion – the unit farthest from the beaches and likely to become engaged during the day. Indeed, already at 7.15 a.m. The battalion had reported enemy in the distance, no doubt the forward patrols of I Battalion, 100 Mountain Regiment. This news was confirmed by Captain Dawson when he returned from 23 Battalion late in the morning; for, indefatigable as ever, and concerned for the shortage of water in the pass, he had collected every water bottle and container he could lay hands on in Sin Kares, filled them, borrowed a truck and delivered them to 23 Battalion.

At 12.30 p.m. Brigadier Hargest reported (still to Division, so strong was habit) that he had ordered 23 Battalion to begin trickling small parties to Sin Kares at half past five and was sending Dawson forward again at 4 p.m. Probably about the same time he sent further orders to Major Thomason who now commanded the battalion: he informed him of the whereabouts and role of the 18 Battalion detachment, predicted that demolitions would prevent a heavy attack that day, and ordered him to begin thinning out ‘about 3 or 4 o’clock’ but to keep his forward companies in position till just before dark.

Dawson duly went up again about half past four and found that Thomason would have to be evacuated because of bomb blast and that the command had passed to Lieutenant Bond,45 the senior of the six remaining officers. The orders Dawson then wrote out were for immediate withdrawal to conform with the arrangements made at General Weston’s conference. The companies were to move out in sections as covertly as possible and go to Sin Ammoudhari, where the wounded and sick – many had dysentery – would be left to wait for transport. The others would go on till met by guides.

The orders were welcome. It was very hot for the weary troops, unable to escape the sun in the baking rocky gorge. Rations were few and water very short. Enemy aircraft had been over and the prospect of bombs among the splintering rocks was not pleasant. And the enemy, about two companies strong, had begun probing, encouraged perhaps by supplies which his aircraft dropped in front of where D Company, with 16 men, held the high ground of Rogdhia.

Headquarters Company in the centre was able to begin pulling out almost at once. For the flanks it was less easy. D Company on the left lost a man killed. On the right A Company and Captain Snadden’s gunners, who had the farthest to go, also came under fire.

We have to run the gauntlet for about fifty yards to a protecting bluff. I send the party off in irregular groups and we all get across but not without some ‘hurry up’. We pick up a trail of blood leading to a goat track that will shorten our march. Our lungs are bursting and our feet aching and burning after our long rest. The bullets are still singing past but now we hear a new sound. There is an Aussie Bren detachment in action ahead of us and without much trouble we cross the divide and are on our way down towards the sea covered with their protective fire. Going up was bad but coming down was ten times worse. New muscles ached and the soles of our feet seemed to slip and slide inside our boots. Our sox were full of holes. Many of us wrapped our feet in first field dressings.46

Nevertheless, thus aided by covering fire from 2/7 Battalion, the 23 Battalion men were able to get safely down and through Sin Kares, where they found some Royal Marine trucks which took them on south.

While 23 Battalion was making this withdrawal the rest of 5 Brigade had been marching back to its dispersal area.47 This was

reached at 11 p.m., A Company being retrieved by 20 Battalion on the way and Major Leggat’s party finding its way back to 22 Battalion at the halt. The dispersal area itself was rocky and the only shelter a little scrub. ‘the place was literally swarming with men of all sorts and nearly all units who had straggled and were now at a loose end eating up rations and using water that fighting troops needed – down below on the plain (sea coast) it was supposed to be worse.’48

Fourth Brigade had begun the day with its units still scattered. The 18th Battalion was at the northern end of the plain, while 20 Battalion and Brigade HQ were at the western edge near Sin Ammoudhari; 19 Battalion was out of touch with 5 Brigade, having overshot its area during the night and – after some confusion which is reflected in 5 Brigade’s orders for the day – returned to 4 Brigade command. And the 19 Battalion RSM, who had assumed command of the mortar platoon and had lost touch with the unit, after attaching himself to 18 Battalion, had taken the platoon north with A Company of that unit when it set off to strengthen the rearguard west of Kerates.

The 20th Battalion moved at 7 a.m. to a position at the south exit from the plain. Here it was followed later by the remaining companies of 18 Battalion, by 19 Battalion, and by 19 Army Troops. These units were placed on either side of the road so as to cover the approaches from the plain. Thus the whole brigade was now together and there was only A Company of 18 Battalion still to come.

This company, meanwhile, was waiting for 23 Battalion to pass through from the top of the pass. For so small a force the danger of being outflanked was considerable and it became more so once 23 Battalion was on the move. Accordingly, at 6 p.m., Brigadier Inglis called for the support of the three guns of 2/3 Australian Regiment.

Once the last of 23 Battalion came through the enemy were not long in following, and A Company was kept busy engaging them until dusk. With so few men – about fifty – it was not an easy front to defend, and although Major Lynch moved his sections about and managed to produce a counter at first for every enemy threat, an enemy machine gun eventually got in behind him and covered the road leading down to the plain. The Australians with

Withdrawal, 29 May

Their ancient Italian 75s were directed on to the machine gun by Brigadier Inglis, and Lieutenant-Colonel Gray acted as spotter. ‘It was the first time I had ever spotted for artillery and Geoff Kirk and I sat on the rocks above the road directing the fire and calling out corrections to the guns. The range, by trial and error, was 3200 yards and they literally rocked it in, firing, I believe, all the 40 rounds which was all they possessed.’49

This sturdy little action and the approach of night persuaded the enemy to prudence. At half past eight the 3 Hussars tank withdrew together with the rest of the rearguard, and lower down the road Gray was waiting with trucks for the infantry. In this exploit the company, weak as it was, a single mortar, a handful of machine-gunners from 27 MG Battalion, and the supporting three guns, had held up at least two fresh German companies.

With A Company of 18 Battalion thus successfully disengaged and darkness come, 4 Brigade was ready to carry out its orders and head for the bivouac area allotted to it among the rocks and scrub west of the end of the road. The move began at 9 p.m. with 20 Battalion and Brigade HQ leading, 19 Battalion and 19 Army Troops following, and 18 Battalion bringing up the rear. The march was arduous and a way had to be forced through the stragglers who thronged the road. It was near daylight before the units reached the spot where the formed road ended and the steep goat track down to the beaches began. At this point the men lay down to seek what comfort weariness could give them among the stones.

To Brigadier Vasey fell the grim task of organising the last rearguard. Besides his own two battalions he had under command the Royal Marine battalion, the three guns, a platoon of 2/1 MG Battalion with two guns, the four tanks of 3 Hussars,50 and three Australian Bren carriers. The tanks and carriers were to delay the enemy as long as possible in front of the defence line and then fall back, the sappers of 42 Field Company RE blowing the road behind them.51

Responsibility for the defence of the new position was not expected to mean fighting until next morning; but there was much

to be done meanwhile. The line had to be reconnoitred and the two Australian battalions withdrawn from the north end of the plain. Accordingly, orders were sent to them both to be clear of Sin Ammoudhari by 9 p.m. Battalion reconnaissance parties left earlier to study their new positions.

The withdrawal from the north was safely carried through, though 2/8 Battalion at least could see enemy trucks and motor cycles coming down the pass towards them from Kerates as they moved out. The move to the new positions was greatly hampered by the stragglers on the road who, ironically enough, suspected that these men who were to cover the final stages of withdrawal were stealing a march to get to the boats. It was after three in the morning before they could occupy their positions, with 2/7 Battalion forward, 2/8 Battalion guarding the deep wadi on the left of the road, and the Royal Marines in reserve.

By the morning of 29 May the greater part of the New Zealand artillery and other components of the Composite Battalion who had managed to get across the mountains were scattered along the road from the Askifou Plain southwards. Many – indeed most – of them were organised in small groups under their officers or NCOs; but they were directionless and without orders and threatened to be a serious impediment to the movement of the larger units. To Major Bull belongs the main share of credit for ending this state of affairs. On his own initiative he soon had an organisation going by which the men were got off the roads, sorted into manageable parties, and assembled under fairly good control in the ravine by Komitadhes. There he arranged pickets and got the officers to prepare nominal rolls. Ultimately all sorts of units were represented and the numbers rose to over 3000. The problem of finding rations for such large numbers was not easy but was tackled, and eventually an issue of bully beef from rations dumped on the beach was arranged – three tins per group of fifty men.

Apart from the MDS at Imvros – which handled 94 of the serious cases in the 24 hours that it was open – there were by now several collecting posts for walking wounded, and British, Australian, and New Zealand medical officers and orderlies had their hands full with the problems of caring for patients, finding rations, and organising the onward transmission of wounded to the collecting post at the end of the road. But by nightfall most of the collecting posts

along the road had been cleared and the majority of the 500-odd patients were moving towards or already at the point where they were being concentrated for the final move to the ships. With each party of fifty wounded went a medical officer and five orderlies. Even this turned out to be not enough, so hard and painful was the track.

The preoccupations of General Weston’s HQ and Brigadier Puttick’s are implicit in what has already been said about the conferences held and the orders issued on this day. Both were much taken up with the superintendence of the various moves of large masses of men in a space continually more confined; and in addition there was much to be done in connection with the arrangements for that night’s embarkation.

For Divisional HQ something more was involved. Now that all the forces of the rearguard were close enough together to be susceptible of control and Weston was able for the first time to exercise the authority he had been given when withdrawal was first ordered, there was nothing further for Puttick and his staff to do, and General Freyberg thought it pointless for them to remain. He therefore sent orders during the day for Puttick to report to Creforce HQ and for Divisional HQ to embark that night.

In obedience to this order the senior officers set off at 5 p.m. Puttick and Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry went straight to Force HQ and reported there at 7.45. Major Davis,52 the GSO 2, and General Puttick’s ADC waited at the control point on top of the escarpment to meet the marching troops of the HQ who did not leave till 7 p.m.

By a quarter to nine this marching party had reached the control point. There they found that the delay caused by the attentions of enemy aircraft and the crowds of stragglers had cost them their passage that night. Those already on the beach and organised for embarkation made up the quota the ships could take. There was nothing for it but to go to the Imvrotiko Ravine and join there the crowds of troops whom Major Bull and the officers with him were still struggling to organise.

Puttick and Gentry meanwhile had stayed at Creforce HQ until 9 p.m. and then gone down to the beach with several officers from Creforce staff. When the time came to embark they did so, all unaware that their own marching party had been delayed and had failed to get aboard.

For the garrison at Retimo this was a sombre day. About 8 a.m. The naval detachment which had been operating the wireless reported that both Canea and Heraklion had gone off the air and, although contact was gained during the day with Alexandria, there was no information to be had, presumably because of security difficulties and the absence of ciphers. The few cases of ammunition and chocolate dropped by aircraft from Egypt at first light were of little help – especially as they were mostly smashed in landing.53

In the evening parties of enemy were seen. At half past nine the Greeks reported about a thousand Germans closing in on the right flank and rear. Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell ordered them to hold on, but against this opposition they were unable to do so and by 11 p.m. had had to withdraw. The 2/11 Battalion was then ordered east to replace them, leaving a company in its old positions, and was on the move till dawn. Midnight brought further reports that about 300 enemy on motor cycles had entered Retimo from the west during the afternoon. Rations were due to run out next day. No message or supplies had come from Heraklion although the road was thought to have been clear during the earlier part of the day. There was no communication with Creforce. Signals made to sea in the hope that naval forces might appear brought no result. The prospect for the next day was grim.

Less than half an hour after the convoy of ships evacuating the Heraklion garrison had put to sea there was a failure in the steering gear of the Imperial, caused no doubt by a near miss from a bomb the day before. The commander of the squadron decided that the only chance was to have Hotspur take off her troops and sink her, if the squadron was to get as far south as possible before daylight. By 4.45 a.m. this had been done and just after daylight Hotspur, with 900 men on board, rejoined the squadron.

The squadron was now an hour and a half behind time and it was sunrise before it could turn south through the Kaso Strait. At 6 a.m. The air attacks began. They were not to stop till 3 p.m., when the squadron was only 100 miles from Alexandria.

In the middle of the Kaso Strait Hereward was hit and lost speed. The commander of the squadron decided he must leave

her. She was last seen making for Crete, the enemy aircraft about her like wasps and the ship’s guns replying.

Arrangements had been made for fighter cover from the Kaso Strait onward and the time had been corrected to allow for the delay. But though the fighters appear to have come at the right time they did not find the ships.

By 7 a.m. Decoy and Orion had both been damaged and the speed of the squadron reduced to 21 knots. At last at noon two naval Fulmar fighters found it. But already the damage was serious. The captain of the Orion had been mortally wounded. Dido and Orion had both been hit, Orion twice. Both had a turret out of action and Orion’s lower conning tower was also gone; and there had been heavy casualties among the packed troops on board.

Other attacks followed in the afternoon but none so dangerous. And at 8 p.m. The ships reached Alexandria, Orion with only ten tons of fuel left and two rounds of 6-inch HE ammunition.

At Creforce HQ the Retimo garrison was still causing General Freyberg great anxiety. During the morning Middle East reported that it had so far been unable to get contact with Retimo but that it was dropping a message by air. This message began by explaining that it was too dangerous to send anything in clear and it then lapsed into code, of which the effect was probably that the garrison should go south to Plaka Bay. Creforce was asked to relay this, if possible, to make assurance doubly sure.

To this Freyberg replied that he had no communications with Retimo and that he doubted if this message would be understood. He suggested that another aircraft be sent to reconnoitre for the force and drop another message. He then gave a code version of a suitable message to the effect that a warship would arrive for them on 31 May.54

This message was indeed sent by Hurricane. The Hurricane did not return and so it was not known whether or not the message had been received. It had not. Freyberg’s worry is reflected in his report that day on the recent developments. After describing the loss of Force Reserve, the defence of 42nd Street and the subsequent withdrawal actions, and reckoning the effective strength of his brigades at less than 700, he went on: ‘Am anxious regarding Retimo garrison and will be grateful if you can assure me if orders for their withdrawal have reached them from GHQ ME. Also would welcome ME information regarding Heraklion.’55

That evening Freyberg received orders for his own evacuation. ‘You yourself will return to Egypt first opportunity.’56 As he had not yet made his plans to hand over to General Weston and was anxious not to leave his men until the last possible moment, he decided not to take this too literally. He would wait till next day.

In Egypt there were conflicting views about how many men were still to be taken off and how much risk should be taken in the attempt. Captain Morse had signalled from Creforce on 28 May that anything up to 10,000 troops would be ready to embark on the night of 29–30 May. From this and from Freyberg’s message about the tactical situation – the one saying that an optimistic view of the number of fighting troops he had would be 2000 – it wa finally inferred that 10,000 would still have to be embarked and that only 2000 of these would be in organised parties.57

The other question was graver. During the day Admiral Cunningham, Air Marshal Tedder and General Blamey conferred and concluded that the danger was too great for more Glen ships or cruisers to be risked but that destroyers would keep on trying till the night of 30 May. They would send or try to send four destroyers that night. But it would be the last.58