Chapter 22: Capture of Ruweisat Ridge

THE Division was in good heart as the leading companies of the four forward battalions, followed closely by the reserve companies and the reserve battalions, crossed the start line at the appointed hour, 11 p.m. Perhaps the keen edge of enthusiasm for battle had been dulled a little. The thrill, excitement, and eager anticipation inspired by the call from the desert and the forced marches from Syria to Matruh had given way to the enervating routine that is the greatest part of war. The New Zealand Division of the First World War had had a similar experience when it plugged the gap in the line on the Ancre in March 1918.

But as the start line for Ruweisat was crossed, no man doubted that the Division was about to fight a winning battle. In any case, it was a relief to be again up and doing, to move from an area subjected to too much shelling and bombing without apparent effective retaliation. These enemy attentions were now to be repaid, with interest.

The night was still, quiet, cold and dark. From the start line, roughly on the 75-metre contour, the ground in the darkness fell away almost imperceptibly by one in 300 to a shallow depression enclosed by the 50-metre contour about five miles away at the foot of Ruweisat Ridge. Except for a lone palm three-quarters of a mile ahead of the start line, the western of the Alamein-Munassib tracks, a patch near the ridge marked on the maps ‘very stony ground’, and the water pipeline and track between Alamein and Kaponga, there were no easily recognised features on which to check distance and plot positions. The ridge was only 35 to 45 feet above the depression, the angle of ascent varying between one in 40 and one in 60. As the ground further north also fell away gradually, the top of the ridge was far from being clearly defined in the dark. Ruweisat was not a long finger descending evenly on both sides and to the west as the map contour lines suggested.

These factors compelled resort to an advance on the Pole Star and a compass bearing, 320 degrees, with a rough equivalent of a mariner’s dead reckoning for estimating distances traversed. The

Division had been trained in such marches and the system had proved satisfactory in 4 Brigade’s advance to Mungar Wahla. In 20 Battalion the intelligence officer, Captain Sullivan, reduced the distance between start and objective to paces and kept the tally on his rosary beads.

Thirteenth Corps’ orders said the Division was to time its movements ‘to make contact with the enemy at 1 a.m. at selected points on the enemy line 882278–875275.’ This line was three and a half miles from the start line. The Division, however, knew the enemy posts were much closer. Consequently, there was no surprise when, shortly after midnight and after about two and a half miles had been paced, minefields were encountered over most of the front. The advance slowed as the fields were investigated. Almost immediately, the enemy put up flares and opened fire, mostly with machine guns on fixed lines. The volume of fire and its pattern suggested awareness or apprehension in the forward posts of a major attack rather than an affair of patrols.

Guided by the lines of the tracer bullets, the leading troops deployed from sections in file to sections in line and moved at the double towards the nearest centres of resistance. With bullet, bayonet, and grenade they cleared a way through the posts, their primary task. Mopping up was to be done by the reserve battalions. Anything these left would be dealt with by the tanks as they came through. The spirited conduct of the infantry in this initial encounter caused them surprisingly few casualties. But, unfortunately, it caused them to lose cohesion and control.

These matters, however, were of relatively little moment. It was much more important that, at this time and point, when only a little more than an hour from the start line and less than halfway to the objective, the Division began to suffer from the faults in planning.

Had the 13 Corps’ divisions been supplied with air photographs when they were first lined up for the contemplated battle on the 11th, they would have known that these enemy posts were not merely the forward defence localities. They formed the main line of resistance. The photographs would have revealed that there was little, if anything, between the strongpoints and the ridge. The Division was to pay a heavy price for the omission and the lesson. In their rapid clearance of passages through the enemy posts and in pressing on to their objectives, the infantry battalions left behind them as much as, possibly more than, they subdued. This was of more fateful consequence than the loss of cohesion and control, as the remaining enemy posts prevented the advance of the support weapons and left the infantry on the ridge naked

and exposed to the counter-attacks of the German tanks, armoured cars and artillery.1

On the Division’s right flank, 23 Battalion had a comparatively easy passage through the enemy. Posts in the gap between New Zealand Division and 5 Indian Division fired on the battalion, and B Company swung to the right to deal with them. The company commander, Captain Begg,2 was killed and the platoons split. Some of the sections continued to engage the posts on the flank and others carried on the advance in small groups under the section and platoon commanders. Most of these were rallied by the battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel C. N. Watson, and taken by him to the battalion objective.

D Company, on the battalion’s left flank, also separated. Some of the men on the company’s right endeavoured to keep in contact with B Company, others carried on independently, and one large group under the company commander, Captain Ironside,3 maintained touch with its left-hand neighbour, A Company of 21 Battalion. The reserve company, A Company commanded by Captain Norris,4 had little trouble from the enemy and in advancing on the correct bearing, but near the objective it saw some tanks on the move.

These tanks belonged to 8 Panzer Regiment and were then probably the most eastern of the enemy armour on the ridge. The regiment had been ordered just before midnight to move to an area three to four miles north-west of Alam Nayil. There it was to fill a gap between 15 Panzer Division and Ariete Division (the latter then being south-west of Alam Nayil), and cover Ariete’s flank and rear and the positions about Kaponga. As the regiment was required to pass through the Kaponga minefield at 5.30 a.m., the most distant troops were likely to be starting the move when they were sighted by A Company about three o’clock.

Captain Norris decided about half an hour later that he had reached his company’s objective. While he was disposing his company he was joined by Lieutenant-Colonel Watson, who added a mixed party from B Company and Headquarters Company to the defence scheme and set up his own headquarters some 600 yards in rear. Later, Brigadier Kippenberger arrived, bringing with him K Troop of 33 Anti-Tank Battery under Lieutenant Ollivier5 with the troop’s four six-pounders.

It was then about five o’clock. The battalion had halted short of the crest of the ridge. Because of the approach of daylight it was decided not to move further on but to get the troops and guns dug in at once. There 23 Battalion, intact and confident of the outcome, may be left in the meantime.

On 5 Brigade’s left 21 Battalion, deployed and advancing on its front of 1000 yards, was too dispersed for effective control. It encountered the enemy at the same time as 23 Battalion. But instead of fire mainly from a flank, it ran into an extended defended position, called by the enemy Strongpoint No. 2, held by Germans and Italians. No undue difficulty was experienced in dealing with the enemy posts and in cutting passages through them. Behind the strongpoint, however, the battalion ran into more of 8 Panzer Regiment’s tanks.

It is a moot point whether the enemy’s dispersion in his wide strongpoint was an advantage or disadvantage to 21 Battalion. The dispersed enemy in his small posts quickly fell under the resolute assaults of the sections with bullet, bayonet, and grenade. Many of the Italians fled. But the series of section fights against unevenly spaced posts, first in front and then to the right and left, caused sections to lose contact with their platoons and platoons with their companies. Further, the pace of the assault led to differences of opinion on the time consumed. Later, this factor was decisive in discussions on the ridge concerning whether the battalion had reached its objective or had further to go.

A Company’s platoons and sections maintained reasonable contact, but when the commander, Captain Butcher,6 reorganised after the assault, he found he had with him a number of groups from D Company of 23 Battalion on his right and from his own battalion’s B Company on his left. He put them with his platoons and resumed the advance.

Some distance further on, the company ran into the enemy tanks. These opened fire with their machine guns and attempted to move away. Such, however, was the spirit of the infantrymen that they attacked the tanks. One was set afire with a sticky bomb placed by a 23 Battalion man who cannot be more definitely identified than as Private Clark. Two more tanks fell to Sergeant Lord,7 of 21 Battalion, who, after shooting the commanders standing in the open turrets, climbed aboard and killed the other occupants with his tommy gun and grenades. But during the encounter Captain Butcher’s left platoon lost contact with the company in following up a retreating tank.

An Italian field battery astride the line of advance was the next obstacle. The gun crews quickly surrendered under assault with the bayonet and were sent to the rear. This enterprise cost the company another platoon which lost contact in the dark and in the excitement.

The battalion’s left-flank troops, B Company under Captain Marshall,8 moved level with A Company through the first opposition but became badly scattered on meeting the tanks. Some groups joined A Company, some waited and joined the reserve company under Captain Wallace,9 and the remainder went on with Marshall to overrun an Italian headquarters and capture a colonel, several other officers, and a number of men who were sent to the rear under the escort of one man.

Marshall’s group had been joined by Lieutenant-Colonel Lynch10 and some of the headquarters of 18 Battalion from the left. They advanced together until about two o’clock when they met a single tank which, although eventually set alight, caused the men to break into small groups and scatter. Marshall was left with about ten of his own men and some stragglers whom he took forward until he met A Company of 23 Battalion digging in. He fired a success signal and added his men to Captain Norris’s defence scheme.

C Company also became dispersed when it followed close behind the leading companies into the confused fighting among the enemy posts. When he emerged on the far side of the defences, Captain Wallace found himself with only one platoon and his headquarters. Wallace had several further encounters with machine-gun posts and transport, until at length he found 19 Battalion reasonably organised about Point 63. Men from other battalions who had joined the group were sent to their own units, and Wallace took up a position near 19 Battalion’s eastern flank.

The picture of 21 Battalion from about two o’clock is of about ten separate platoon, company, and headquarters groups comprising their own men and parties and individual stragglers from other units, all searching for the objective and for each other. Some of these groups were to confound and confuse the enemy and to perform valorous deeds. But from shortly after that hour, 21 Battalion as a unit was lost to 5 Brigade. As the subsequent operations of the most substantial groups were beyond the scope of the brigade and divisional plan, they are recorded separately in a later chapter in order to preserve the thread of the main narrative.

Fifth Brigade’s reserve battalion, the 22nd commanded by Major Hanton,11 crossed the start line about 1500 yards behind the leading troops. It advanced steadily along the given bearing without encountering direct opposition or finding much mopping-up to do. The brigade commander, however, caught up with the battalion as it was passing through the enemy defences and told Hanton that the ground was not being searched thoroughly for further enemy posts. The battalion appears to have struck gaps cut by the leading units and to have passed through them on a compact front with the companies keeping good formation.

As it pushed on, the battalion closed the distance separating it from the forward units. It collected numerous prisoners from posts which had been bypassed and sent these and others taken by the leading troops to the rear. It also collected groups and individuals from the brigade’s other battalions and from 18 Battalion and took them forward. The scene is well described by a rifleman of the battalion:

We could hear tanks beginning to rumble back. We could hear shouts of Italians crying ‘Mamma mia – Mamma mia’. ... Mortar commenced to fall around us. There were some slight casualties. ... There seemed to be some of our tanks on the right flank.12 I saw two tanks apparently bumped into each other fire short vicious bursts directly at each other. The tracer ricochetted off each turret and the tanks hurriedly withdrew.

The scene before and around us was a mad and weird pattern of coloured tracer. There was the hoarse shouting of our men using the bayonet and the frightened ‘Mamma mia’ of the Italians. We were moving forward in slow easy stages spending waiting time on our stomachs while mortar landed about us. ...

Shortly after crossing the Alamein-Munassib track, Hanton thought the battalion had covered the prescribed distance. Brigade headquarters, however, ordered him to resume the advance until he joined the leading units on the ridge. He was then to set his men in position immediately to their rear.

As the march continued, heavy enemy machine-gun fire developed on the right flank. An investigating section reported that it came from a tank which it had been unable to approach. Hanton thereupon endeavoured to report to Brigade the proximity of enemy tanks, with a request that the anti-tank guns should be hurried forward. But by this time the batteries in the wireless set were failing and communication could not be established. A runner who never arrived was then sent back with the message and request.

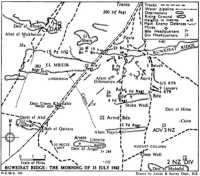

Ruweisat Ridge: the morning of 15 July 1942

Major Hanton took the battalion forward until he reached the southern slope of the ridge. Here he was again met by Brigadier Kippenberger, who ordered him to lay out defences on a 1200 yards front covering rising ground ahead and to make contact with 23 Battalion and the Indian troops expected to be up on the eastern flank. After visiting 23 Battalion and placing K Troop between the two battalions, Kippenberger set off in his carrier for brigade headquarters.

Little was then known of the situation of 21 Battalion, but as numerous bodies of prisoners had appeared from its sector, it was thought the battalion was on the ridge some distance to the west. Lieutenant-Colonel Watson visited 22 Battalion a few minutes after the brigade commander had left. He and Major Hanton agreed that their battalions were on the objective and that the situation generally appeared to be satisfactory. It would be made secure as soon as the supporting arms arrived. The time was about half past five.

In the meantime, 5 Brigade Headquarters, with supporting arms and the A echelon or fighting transport of the units, was making its way forward. The column included, as ordered, the Brigade

Defence Platoon, the detachments of 7 Field Company and K Section signallers, three platoons of No. 4 Machine Gun Company, the Bren and mortar carriers, the trucks carrying the No. 11 wireless sets, and some ambulance cars.

The anti-tank position was not satisfactory. The infantry two-pounders on portée joined the column instead of travelling with 22 Battalion as they had been instructed. Of 33 Battery’s four troops, only one, M Troop in brigade reserve, was in its correct place. The other three troops had been ordered to move behind 22 Battalion. Only Lieutenant Ollivier had his K Troop on the start line before 22 Battalion moved. He waited some time for the other two troops, and when they failed to appear he went on independently until he met Brigadier Kippenberger and was taken forward to the ridge. The other two troops, J and L, missed the start line and were led into 4 Brigade’s line of advance by the liaison officer detailed as their guide. They did not rejoin 5 Brigade until some hours later.

These errors were to have fateful consequences. Had the antitank guns been in their correct positions, that is with and hard on the heels of 22 Battalion in its quick and comparatively easy advance to the ridge, they would have been on hand to deal with the enemy tanks which wrought havoc on the ridge about first light. At the time, however, the advance of the brigade appeared to be proceeding in orderly fashion. Brigade headquarters was in touch with 22 Battalion, which reported that it was not meeting with any direct resistance and that it had not received any requests for assistance from the forward battalions. The disarray of the anti-tank guns was annoying, but there was nothing to suggest it would place the operation in danger.

What was more annoying and more disturbing was the breakdown in communications that followed soon afterwards. The No. 9 wireless set connecting the brigade with Divisional Headquarters developed a fault and then the truck carrying the set broke down. Communication was re-established only by using the emergency control on a No. 11 set to the CRA’s office at Divisional Headquarters, where the messages had to be sent on by runner in the dark to the ‘G’ office some hundreds of yards away.

Then wireless contact within the brigade was lost. The risks inherent in the limited range and known defects in the No. 18 set had been accepted. The new batteries supplied for the operation proved so defective that they ran down shortly after being put into use. Communication with 23 Battalion failed soon after the first opposition was encountered, and with 22 Battalion when it reached the ridge. The 21st Battalion remained on the air until the

brigade major, Major Fairbrother.

... discovered to my consternation that the wireless operator was not with Sam Allen or the battalion headquarters but had gone to ground away back behind us and didn’t know where he was, what direction his unit had taken, or where to go.

Sympathy might be spared for the unfortunate signaller who, while packing a No. 18 set, would have some difficulty in keeping pace with a spirited advance let alone keep close contact with a commanding officer, an adjutant and an intelligence officer, all of whom went different ways. Nor in the circumstances was he likely to assimilate the lesson on how to find the Pole Star which the brigade major tried to give him ‘over the blower.’

Finally, the planned line communication forward and to the rear broke down. When a cable party laying a line from brigade headquarters to the start line found a fault, the officer in command went back to locate it. He became lost. The rest of the party awaited his return until about half past four when another signals officer, following the line from Divisional Headquarters, picked them up and took them on to brigade headquarters. Later the cable was broken several times by traffic in the rear area.

The K Section detachment detailed to carry a line forward of brigade headquarters put down two and a quarter miles and then halted to await further supplies to be furnished by another detachment reeling in the line behind the headquarters as it advanced. Ill luck dogged these detachments. A mechanical fault in the equipment delayed the second detachment near the start line. By the time it caught up with the first detachment, the battalions were well ahead. Consequently there was no line for them to tap into at halts as had been arranged. Moreover, brigade headquarters, moving independently on its own reading of the compass, deviated from the line of the cable and did not meet the laying detachments.

The headquarters and vehicle column reached its allotted area at Point 6513 on the Alamein-Munassib track about four o’clock. Several wounded Italians crying for help were found as well as a number of enemy and New Zealand dead. The sounds of battle had died down but shortly afterwards fire broke out afresh, especially from the neighbourhood of Strongpoint No. 1 on the headquarters’ right. Some of the two-pounders were deployed to cover the flank and the defence platoon was despatched to deal with any enemy posts it might find. The platoon was not heard of again for some hours.

From this area Brigadier Kippenberger, taking K Troop with him, visited the forward area. He had some brushes with the enemy on the way and he ordered Major Hanton to send a platoon to clean out the posts. After noting the positions on the ridge, the brigade

commander set out for his headquarters to speed the advance of the supporting arms against the near approach of dawn and the danger it might be expected to bring.

Thus between five and six o’clock 5 Brigade was consolidating most of its objective on Ruweisat. On the right 23 Battalion, consisting of A Company, elements of B, D and Headquarters Companies and two parties from 21 Battalion, was holding the crest of the ridge about 1000 yards east of Point 62. A few hundred yards to the south and below the crest, 22 Battalion in full strength was preparing to dig in. K Troop, with its four six-pounders, was between the two battalions. Between 22 Battalion’s left flank and 4 Brigade’s defensive sector there was an unprotected gap of more than a mile. The 21st Battalion was thought to be in this area. Brigade headquarters had reached its area but was still under fire.

The general impression was that the attack had gone well. Certainly some confusion was apparent, but the objective had been reached in quick time with surprisingly few casualties. With the speedy arrival of the supporting weapons and the British tanks, the ground won could be secured and the units made tidy against any action the enemy might take.

As 4 Brigade crossed the start line, also promptly on time, there was no thought that this would be the last action it would fight in North Africa. And if the brigade was more fortunate than the 5th in arriving on the objective in greater strength, it was more exposed to the enemy’s counter-thrusts and thus riper for the kill. The 15th July was to be another sad day for the Division’s senior brigade.

Some important changes in the disposition of the brigade had been made after the issue of the written orders for the battle. As finally arranged, 18 Battalion advanced on the right, 19 Battalion a little to its left rear, and 20 Battalion in reserve behind the 18th. Brigadier Burrows had his advanced brigade headquarters behind 20 Battalion, and he was followed by the A echelon vehicles in three columns under Major Reid,14 6 Field Company, who had with him a party of sappers and two trucks of mines.

The main vehicle column came next. Its principal constituents were three troops of 31 Anti-Tank Battery and detachments of the infantry two-pounder platoons, the Brigade Defence Platoon, Nos. 4 and 5 Platoons of No. 2 Machine Gun Company, and two American Field Service ambulance cars. One carrier, the brigadier’s,

started the advance but was sent back early because it made too much noise. The other Bren carriers, the three-inch mortar carriers, No. 6 Machine Gun Platoon, and a party of 6 Field Company sappers were held near B echelon to await orders to join the assaulting troops.

The brigade artillery group, comprising 4 Field Regiment, 41 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, A Troop of 31 Anti-Tank Battery, part of No. 3 Section 6 Field Company, and the remainder of the two-pounder platoons, were held on Alam Nayil under orders to be ready to advance when called upon.

To 18 Battalion, the fire and then the conflict in the enemy’s Strongpoint No. 2 and subsidiary posts proved irresistible magnets. D Company, on the right on the brigade boundary, turned to confront the resistance and was followed by B Company. Thus almost as soon as contact was made with the enemy, both of the leading companies veered half-right off the course. Then, as other enemy posts ahead and on the flank opened fire, sections and platoons assaulted with such dash and spirit that little attention was given to direction and formation. Consequently, in a short time the two leading companies became widely spread and mingled. In spite of the efforts of Lieutenant-Colonel Lynch, the commander, and other officers, the battalion did not regain its formation during the battle. Major Brett,15 commanding D Company, brought part of the company together but found himself on the battalion’s left flank next to 19 Battalion, with which he carried on the advance. Lieutenant Bush,16 with part of his platoon, eventually reached the objective in company with the reserve battalion. Sergeant Aitken,17 of 18 Platoon, kept two of his sections together, and after clearing some machine-gun posts found he had a number of prisoners but only eight of his own men left. He handed over the prisoners to three 21 Battalion men who were guarding prisoners of their own, and then led his small party through several more skirmishes until, with only three men, he joined Major Brett on the objective. There he was placed in charge of about 150 captive Italians.

The dispersion of B Company was even greater. From their positions on the battalion’s left flank, some men moved across the front to become mingled with D Company and scattered parties from 21 Battalion. Others moved to the left and joined 19 Battalion’s advance. Still others were caught up by 20 Battalion as it came forward in reserve. One platoon, under Lieutenant

Burridge,18 advanced independently, gathering 19 Battalion stragglers, until it joined the battalion’s reserve company near the objective.

By contrast, the advance of C Company under Captain Sutton19 was a model of orderliness and firm control. Keeping to the correct course, the company soon encountered enemy posts missed by the leading companies. Sutton dealt with these by co-ordinated fire and movement, the Bren gunners giving frontal fire while the riflemen attacked the posts from the flanks. Prisoners were collected and taken forward.

When fire developed on the left flank, Sutton despatched Lieutenant de Costa20 and his platoon to deal with it. The fire, however, came from a tank which the platoon was unable to assault successfully. Ahead of the main body of the company, a burning vehicle illuminated the desert and, according to Captain Sutton:

Into the scene came two tanks firing machine guns at all and sundry. We moved out of the way of this well-lit area but the tanks moved too and so down we went. They seemed to come straight for us but they stopped. I looked up and saw someone with head and shoulders above the hatch and behind the tank there were three or four figures, one with a tommy gun. The gun was lifted and the German took the whole burst.

The company moved past the tanks and crossed an area pitted with slit trenches in which were lying the bodies of many bayoneted Italians. It then came under heavy mortar fire. Sutton’s account continues:

We used these trenches and our Italian prisoners who were still with us had to flop down beside them [i.e., their dead compatriots]. I decided we must be off our line of advance and turned half-left, eventually meeting a provost sergeant of 19th Battalion who had more prisoners than he could handle. I asked him to take mine and he said he had thousands already. I gave him mine and left him still protesting. Moved on, hearing terrific screams on our right. There was a queer lull or hush at the time so we made off in the direction of the noise.

Before a tank there was a soldier of 18th Battalion with two Germans pinned against the side. He had his bayonet and was saying ‘What about Belhamed?’ and the Germans were screaming. ...

The company eventually reached the ridge accompanied by Lieutenant Burridge’s platoon. Guided by a success signal, it rallied on Major Brett and the adjutant, Captain Batty.21 The group was then to the east of 19 Battalion with which were found most of Brett’s D Company, as well as other men from 18 Battalion.

The two companies and part of battalion headquarters were reorganised under Brett’s command and, by arrangement with 19 Battalion, took over the defence of the eastern flank of that battalion’s position. Nearby was Captain Wallace’s group from 21 Battalion.

Although 18 Battalion lost cohesion, the isolated small parties, sections and platoons, like those of 21 Battalion, carried on the fight. When Lieutenant-Colonel Lynch saw that his leading companies were deviating from their course he hurried forward, but by the time he reached them the fighting had spread over too wide a front. Lynch was then compelled to lead the few men he could rally in successive attacks on machine-gunners who continued in action after the leading troops had passed them. When these had been dealt with the small party found itself on the left of Captain Marshall’s group from 21 Battalion, with whom the advance was continued. The groups separated in the confusion following an encounter with a tank. Lynch then moved on to the objective. As he did not find any considerable body of his battalion there he turned back in the hope of meeting the reserve company and eventually reached the advanced headquarters of 4 Field Regiment, where he organised an attempt to take the supporting arms forward.

Lieutenant de Costa’s platoon, after its unavailing effort against a tank, found that the rest of the company had gone on. The platoon thereupon advanced independently. It had several successful encounters with enemy posts until, on meeting stiff resistance from enemy gun crews and failing to find supporting troops to assist, the platoon withdrew in the belief that it had overshot the objective. With about a dozen prisoners, the platoon joined 20 Battalion and accompanied it to the objective.

The disintegration of 18 Battalion in the battle’s early stages may be compared with that of 21 Battalion. It appears to be indisputable that 21 Battalion’s dispersion over a front of 1000 yards in the dark and on terrain devoid of landmarks contributed largely to the loss of cohesion. On the other hand, 18 Battalion attacked on a narrow front of about 200 yards, its share of the brigade front of 400 yards. Thus it was compact when it crossed the start line and encountered the enemy. The battalion, however, had ample room on both of its flanks in which the platoons and sections had freedom of manoeuvre.

The common factor was the spirit of the men in both battalions. Collectively and, in many cases, individually they attacked the enemy wherever he showed fight. Direction and cohesion were subordinated to the task of subduing the enemy posts as they revealed themselves in front, half-right, half-left, full-right, full-left and often behind. It is true that the officers and men had been

told that the most important task was the cutting of gaps through the defences and gaining the ridge, and that mopping-up would be done by the reserve companies and battalions. Both units cut their gaps and gained the ridge with few casualties, but not on the precise frontages at which they had aimed. They were also without considerable numbers of their men who had lost touch during the advance and did not rejoin until some time after daylight.

On 4 Brigade’s left, 19 Battalion kept good formation and, although it had several encounters with the enemy, arrived on the objective almost intact. However, 18 Battalion’s dispersion and the activity in that battalion’s area caused the 19th to concentrate on the resistance on its right flank, with the result that it gradually moved over to the right and reached the ridge in the area prescribed for the 21st.

After dealing with several enemy outposts, the battalion reached an extensive Italian position in a slight depression to the right of its line of advance and to the left rear of Strongpoint No. 2. Lieutenant-Colonel Hartnell laid on a controlled attack. He sent his left company, D, around the left flank, Major Brett with his D Company of 18 Battalion around the right, and, keeping A Company still in reserve, led B Company in frontal attack. The Italian resistance collapsed rapidly under this pressure and a number of trucks, 20-millimetre Breda guns, and about 150 prisoners were taken.

The battalion had a few more skirmishes before it reached the southern slope of the ridge shortly before dawn. The first troops over the ridge were met by heavy small-arms fire, most likely from Germans guarding 15 Panzer Division’s artillery, and suffered a number of casualties. From the forward slope facing north, the leading companies engaged an enemy convoy passing from east to west and destroyed several trucks. A body in the leading vehicle was later identified as that of the German liaison officer with Pavia Division. The German accounts suggest he was on his way to headquarters to report on the events of the night.

Hartnell fired a success signal to proclaim his arrival on the ridge. As wireless communication had failed and no other troops appeared, he decided to take up a position for all-round defence where he was, although in the brigade plan he was to guard the western flank. In the chosen position, the battalion’s left flank rested against Point 63 with B Company facing north, D northwest, A west and south, and D Company of 18 Battalion facing east. The area contained numerous deep dugouts, and battalion headquarters was set up within a small field of scattered mines.

At first light 20 Battalion, with some more of 18 Battalion’s men and Advanced Brigade Headquarters, arrived on the battalion’s

left flank. Their advance had also been well co-ordinated and controlled. Under Brigadier Burrows’ direction, Major I. O. Manson, in command, had halted the battalion and the A echelon transport while the leading battalions dealt with the first opposition. The column waited half an hour, during which enemy shells from the west caused a few casualties, until Burrows returned from a reconnaissance with orders to resume the advance.

About a mile further on, D Company on the right found a defensive position consisting of a network of weapon pits and dugouts. The position appears to have been missed by 19 Battalion through its deviation to the right. Captain Maxwell22 and his men quickly closed on the enemy with the bayonet and rounded up 300 Italians, who were sent to the rear under the escort of a single infantryman. D Company had only minor opposition once past this area. It picked up 21 Battalion’s anti-tank platoon, which was instructed to join the brigade’s A echelon, and then Lieutenant Bush and his platoon from 18 Battalion who were taken under command.

Captain Upham had C Company on the left flank. At the first halt the brigade commander, concerned about the delay and the lack of definite news from the leading battalions, ordered him to send someone forward to learn what was happening. Upham undertook the mission himself in the brigade liaison officer’s jeep. When he came under fire, he set up an enemy machine gun on the jeep and returned the fire while the driver picked a way forward. Of his reconnaissance, Upham said:

... I could not find 19th Battalion when going forward and 18th and 21st were in confusion. So were the Germans. They were getting trucks out, pulling guns back by hand. All this went on under cover of fire by tanks which in groups of three were covering the withdrawal. It was a very colourful show with flares going up, tanks firing red tracer bullets from machine guns. Two German tanks were put out by 18th Battalion with sticky bombs. They went up close to me. The German troops were being badly cut up while the Italians were surrendering in hundreds. They were out of all proportion to our people and really broke up the attacks with their crowds. ... All the time this was going on, and even before it, there was a rumble of tanks on our exposed left flank. We thought it came from our tanks which were supposed to be there.

The detail shows that Upham covered a considerable area. He reached 19 Battalion when it was near its objective and then made his way back to report to the brigadier before resuming command of his company and taking it forward.

Near the objective, C Company came under heavy machine-gun fire from the left flank. As the company breasted a slight rise it

saw a force of guns, trucks, and troops in some confusion. Upham ordered an attack, and with one accord the men made a bayonet charge for about half a mile down the slope into the depression. Major Manson directed Captain Maxwell to assist, and 18 Platoon was detached to take part in the charge. At the same time A Company, under Captain Washbourn,23 having caught up with the leading troops from reserve, was ordered to support.

The enemy comprised German artillery, including two of the formidable 88-millimetre triple-purpose guns, which were deployed a little to the east of 15 Panzer Division’s headquarters. There were also, as D Company’s platoon reported, ‘odd men on foot, machinegun posts and several snipers.’ All were overrun in the bayonet assault. When the battalion consolidated in the area, it found itself possessed of two German officers, forty to fifty German other ranks, and well over a hundred Italians. Upham was wounded in the arm, and while the injury was being dressed, Captain Sullivan, the Brigade IO, took command of the company and directed its consolidation.

By dawn the whole of 20 Battalion was on the objective in good shape but in the area that should have been occupied by 18 Battalion. D Company faced north on the forward slope to the north of Point 63. C Company held the west front of the area on a rather exposed forward slope and under tank fire from the west. On the reverse slope to the south-east of C Company, A Company held the southwest part of the area. It also was under tank fire.

Advanced Brigade Headquarters reached the ridge with 20 Battalion. The A echelon vehicles, in their three columns under Major Reid, arrived at the southern slope hard on the heels of the battalion shortly before first light. As 20 Battalion made its bayonet attack the vehicles were fired on from the west. Reid directed them to turn half-right into cover over the crest of the ridge which, by this time, was showing clearly in the dawn light. Barbed wire, suspected to mark a minefield, held up several of the trucks, which remained on the exposed slope until a gap was found. Most of the anti-tank portées reached the reverse slope and quickly go into positions from which they could fire at the enemy.

This dash over the ridge is graphically described by Sergeant Robinson24 of 20 Battalion’s anti-tank platoon:

... The dawn was well on the way as we came in sight of the ridge and also in sight of some Huns who must have come in on our [western] flank. Get a picture in your mind of about 100 guns and trucks in three columns moving slowly up the ridge. ... and all of a sudden hell breaking loose among them. ... Gay Fawkes night is not a patch on the noise that was going on, nor of the different colour tracer and anti-tank shots he

[the enemy] was using. The dash to the ridge was made in great style and once over the top we were only a matter of seconds getting our guns into action.

Although the signals communications within the battalions broke down chiefly because of defects in the batteries of the No. 18 wireless sets, the brigade signal plan for the advance functioned satisfactorily, the only breaks being due to the normal hazards of battle. No. 11 sets carried by the battalions in trucks provided links with Advanced Brigade Headquarters and with 4 Field Regiment in the rear, but 19 Battalion lost its link when the signals truck was damaged by enemy fire early in the advance. J Section, Divisional Signals, maintained communication direct with Divisional Headquarters with a No. 9 set. Another link was provided by the artillery liaison officers through their battery and regimental headquarters to Rear Brigade Headquarters. Line communication would also have been established from the ridge had not a cable-laying party been captured by Italians when awaiting fresh supplies of cable about half a mile from the ridge.

By dawn 4 Brigade was on the objective in reasonably good shape. Two of the battalions were practically intact and there were parts of the third. The brigade commander and his advanced headquarters were up and were in communication by wireless or runner with the battalions, the artillery and Division. There were three troops of six-pounder anti-tank guns, and a number of two-pounders and two platoons of Vickers machine guns. Although liaison had not been established with 5 Brigade to the east and the brigade was still in contact with the enemy on the north, west and south-west, the situation was considered satisfactory. The British tanks were expected shortly, and the artillery would soon be up to give close support and deal with the enemy threatening the communications.