Chapter 12: Breakthrough at Akarit

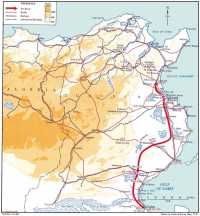

Eighteenth Army Group Plan

WHILE all the turmoil had been going on between Medenine and Gabes, elsewhere Eighteenth Army Group was increasing its activity after the upheaval at the end of February. There have been occasional references in preceding chapters to the action taken by 2 US Corps in attacking towards Maknassy, and this pressure was kept up in early April but without much success. Farther north First Army was now organised into 5 and 9 Corps – which comprised 6 Armoured, 1, 4, 46, and 78 British Divisions – and the French 19 Corps of about two divisions. On this front an Anglo-French force resumed the offensive north of Medjez el Bab on 28 March, and in the course of a few days advanced some 18 miles. It was intended that this offensive should continue and free Medjez from enemy threat.

Alexander by this time had prepared a long-term plan for ending the war in North Africa, of which the first two phases were to be the advance of Eighth Army through the Akarit position and a thrust by 9 Corps towards Kairouan, so threatening the rear of 1 Italian Army. (In the preliminary stage of the second phase, American troops entered Fondouk on 27 March.) By these two offensives Alexander would obtain the use of the coastal plain west and north of Sousse and, in his own words, ‘seize and secure airfields ... from which we can develop the full weight of our great superiority in the air, thereby paralysing the enemy’s supply system’.

Eighth Army Plan

There was still a chance – or perhaps it would be better to say a hope – that 10 Corps might secure the Akarit line without a formal attack. Pressure by 2 NZ Division might enable 1 Armoured Division to pass through. This possibility was discussed by Montgomery with Horrocks and Freyberg at a conference south of Gabes on 30 March, the outcome being that Horrocks was to consider whether or not this was practicable. In the meantime 30 Corps would prepare a plan for a set-piece attack.

Gabes to Enfidaville

The New Zealand Division continued to test the defences on 30 and 31 March, after which Horrocks reported that the line was firmly held, and that 2 NZ Division could not get through without heavy fighting, and resultant heavy losses. This was contrary to Montgomery’s wishes. First, he did not want to incur heavy casualties at a time when the end in North Africa was seen to be inevitable, and when he himself knew that Eighth Army was to be the British component of the Allied forces to invade Sicily. Secondly, he wished to use 2 NZ Division in the exploitation beyond Akarit.

Thus the burden fell on 30 Corps. A first plan was produced in which 51 (Highland) Division would relieve 2 NZ Division and keep up the pressure with a view to attacking later, but only if necessary, for the hope that set-piece action could be avoided still continued. Part of the reason for this lay in the results that would ensue from a successful offensive by 2 US Corps, which at the best would reduce Eighth Army’s part to a follow-up; but this hope proved illusory.

The final decision, therefore, was to launch an attack with three divisions, to open a gap for 2 NZ Division, for 1 Armoured Division to follow through, and for 10 Corps to take up the pursuit with these two divisions. Codename for the operation was SCIPIO, to be launched on 6 April. Montgomery could not wait for the next moon, and this time the attack was to be in the dark, an hour or so before daylight.

There were good reasons for these changes of plan, but the outcome was a rather bewildering number of Army and Corps operation orders and instructions giving many alternatives, changes in responsibility for sectors, and transfers of formations during the battle from one corps to another. The result, however, was a brilliant success, and further evidence that Eighth Army could take such troubles in its stride.

The Terrain

The position now confronting Eighth Army was known to both sides as the ‘Akarit Line’, but was sometimes described by one or the other as Wadi Akarit, the Gabes Line, the Gabes Gap, or the Chotts. Had Rommel had his way, it would have been prepared when the Battle of El Alamein was seen to be decisive and the Allies had landed in Algeria, and there would have been only delaying action between Egypt and Akarit during the withdrawal. Rommel was reinforced in this opinion after inspecting the Mareth Line in January and confirming that it could be outflanked. The outstanding virtue of the Akarit Line from the German standpoint was that it rested on the sea to the east and the Chotts to the west

and could not be outflanked. The western end rested on Sebkret el Hamma (the eastern end of Chott el Fedjadj), which was virtually impassable.

Wadi Akarit itself ends at the coast about ten miles north of Oudref, trends towards its source just south of west for about four miles, and then bends to the south-west for another four miles, at which point it disappears in the low watershed between the coastal slope and the inland descent to Sebkret el Hamma. The wadi banks in the lower reaches are steep. There is a gap of only about one mile between the western end (the source) of Wadi Akarit and the eastern end of Wadi Telman, which drains into the Sebkret. Both wadis are normally dry.

Behind Wadi Akarit and Wadi Telman is a line of hill features, the eastern end of a range north of the Chotts. Starting from the west these are (a) Djebel Zemlet el Beida; (b) Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa, a much higher feature with three separate peaks named from south to north Rass oued ez Zouai, Djebel Mesreb el Alig, and Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa itself, together with a fourth peak to the east of the last-named called Djebel el Meida; and (c), three miles farther east across a marked col, Djebel er Roumana, often known as Point 170. These features completely overlook the country south of Wadi Akarit.1

In the approaches to the Wadi Akarit position the going was difficult off the roads owing to frequent small wadis, marshes, and patches of soft sand.

The enemy made use of Wadi Akarit itself for his main defence line for the first five miles from the sea. From there an anti-tank ditch carried on south of west for a mile and a half and then ran north for half a mile and west for two miles, this last stretch covering the gap between Djebel er Roumana and Djebel el Meida. It was covered by a minefield throughout. Farther west the enemy relied on the naturally broken ground of Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa and Zemlet el Beida, strengthened by some defensive works. There was a second anti-tank ditch resting on the rear (northern) end of Djebel Roumana and running thence south-east to Wadi Akarit. Both sides of all these ditches were staked, and over the whole length of the line there were well dug-in positions. An attempt had been made latterly to dig an anti-tank ditch between the rear slopes of Zemlet el Beida and Sebkret en Noual to the north-west, probably as a precaution against another left hook.

Enemy Dispositions

First Italian Army had to rely mainly on Italians to hold the line, while the Germans laced the position at critical points. The line was held by XX Corps on the east and XXI Corps on the west. XX Corps had Young Fascist Division on the coast, 90 Light Division astride the main road, and Trieste Division as far as Djebel Roumana. XXI Corps had Spezia Division on the east and Pistoia on the west, with one regiment from 90 Light, and with what was left of 164 Light Division as reserve. The 90th Light Division was much concerned about the defence of Djebel er Roumana, which was not in its sector, and did its best to persuade the Italians to strengthen the defences, even to the extent of offering to put a German battalion there. The offer was not accepted, but 90 Light nevertheless directed one of its regiments to reconnoitre routes to Roumana.

The enemy’s transport situation was acute. The 90th Light Division was only 50 per cent mobile, and 164 Light had to march on foot back to its existing position in reserve.

But, as usual, Eighth Army’s greatest interest was the whereabouts of the three panzer divisions. The 15th Panzer Division, with only fifteen runners at this time, was in reserve behind XX Corps, much as at Mareth. The 10th Panzer Division, with fifty tanks, together with a heavy tank battalion of twenty-three tanks and Centauro Battle Group with ten, was opposite the Americans at Maknassy. And 21 Panzer Division with forty tanks was opposing the Americans at El Guettar, 50 miles south-west of Maknassy. The enemy’s armour was thus dispersed, with the greater strength opposite the Americans, but it was all within one night’s travel to any part of the front.

The average strength of the unarmoured divisions, whether German or Italian, was estimated at 4100, and the total unarmoured troops in the Akarit line at 24,500.

However, as with all enemy strength states at this period, the record is insufficient for any degree of certainty. A contemporary estimate for 7 April 1943 puts the strength of 1 Italian Army, including its German element, at 106,000.

2 NZ Division is Relieved

During 31 March reconnaissance of the enemy position continued, patrols from 21 Battalion bringing back reports of defences with outposts in front. The 23rd Battalion was moved forward to strengthen a somewhat nebulous position, and then 5 Infantry Brigade formed a properly co-ordinated gun line near the main road. The 21st Battalion was on the right of the railway line just

west of the road, and 23 Battalion on the left, the general line of the FDLs being some two miles short of Wadi Akarit. The troops and the guns of 5 Field Regiment moved up after nightfall, and 4 and 6 Field Regiments also deployed, although in some places it was difficult to find good positions. Both Sound Ranging and Flash Spotting Troops of 36 Survey Battery found good sites, and Survey Troop was as usual busy with bearing pickets.

The position was occupied without enemy interference, but in the morning of 1 April it was both shelled and mortared. However, during that time the relief officers from 51 (H) Division arrived to reconnoitre the line, and after dark the relief took place. Fifth Infantry Brigade then withdrew to the west of Metouia. Divisional Cavalry patrols were withdrawn, and the whole Division, including 8 Armoured Brigade, but less the divisional artillery, was now in rear areas. The artillery was to support 30 Corps in its attack, and remained in position.

Plans and Orders

At a 30 Corps conference on 1 April, the Corps’ plan was explained for the first time. The New Zealand Division would not take part in the main attack, but would pass through a gap made by 50 Division, and would not advance until the gap was made. The Army’s final objective was the line Sfax-Faid (codename RUM), but at that stage the situation would be reconsidered, as there should by then be a junction with the Americans. Thirtieth Corps was responsible for a sector from the sea up to and including Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa, with 10 Corps west of that point. The objectives of the attacking divisions were:

51 (Highland) Division—Djebel er Roumana

50 (Northumbrian) Division—the pass between Djebel er Roumana and Tebaga Fatnassa, where a gap was to be made for 2 NZ Division

4 Indian Division—Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa

The 7th Armoured Division was in reserve. As 2 NZ Division was to pass through a gap made by 30 Corps, it was under tactical command of that Corps at the outset, but at a suitable time when it was into or through the gap it would revert to the tactical command of 10 Corps.

For the moment 10 Corps was responsible only for the line west of 30 Corps. On the night before ‘D’ day the Corps—in effect 1 Armoured Division and ‘L’ Force—was to make a feint attack by way of deception. The 1st Armoured Division would follow 2 NZ Division, with the latter responsible for armoured car reconnaissance across the whole Corps’ front until 1 Armoured Division could speed up and position itself on the left.

The right boundary of 10 Corps after the breakthrough was a line parallel to but one mile west of the main road for about 20 miles, and thereafter due north. ‘L’ Force was to relieve 1 Armoured Division early on ‘D’ day and would then protect the left flank during 10 Corps’ advance, ranging just as far to the west as terrain and resources would permit. The initial objective for 10 Corps was to be the area round Sebkret en Noual, bounded by the line of the railway from Mahares to Mezzouna.

Both the 30 Corps break-in and the 10 Corps break-out were to be closely supported by the Desert Air Force, as an extension of the air attacks on enemy positions, transport and landing grounds which were already going on relentlessly day and night. For 30 Corps’ attack there would be a fighter screen to protect close and concentrated attacks similar to those at Tebaga. Subsequently 2 NZ Division would have steady air support, on call through four air tentacles. The arrangements included many details for indicating targets and forward defended localities, and for making specified landmarks by letters bulldozed in the sand and blackened with burned petrol tins.

One small point of interest at this time is that the shadow of United States formations falls across Eighth Army, for in many orders, including those of 10 Corps, it was thought better to specify that the British formation was ‘1 British Armoured Division’, as the United States formation round Maknassy was 1 US Armoured Division.

For this operation there was an absolute proliferation of code-names, and one paragraph in a 30 Corps’ instruction reads:

To avoid any risk of duplication or confusion any code names to be used by divs will be restricted to the following types of words:—

HQ 30 Corps – Classical names

CCRA – Birds

7 Armd Div – Biblical names and animals

2 NZ Div – Food names

50 (N) Div – Girl’s names

51 (H) Div – Scotch place names

4 Ind Div – Games and sports

Army Headquarters used names of drinks, e.g., GIN and RUM; 1 Armoured Division used names connected with horses and harness, while ‘L’ Force used colours.

2 NZ Division Orders

The operation instruction for 2 NZ Division (No. 14) was not issued until 5 April, and was as usual the culmination of many conferences, discussions and general activities in the period from 31 March.

The order, after recapitulating the details of Army and Corps instructions, then prescribes the order of march through the gap as:

8 Armd Bde less B2 Ech

2 NZ Div Cav

KDG

Gun Group

5 NZ Inf Bde Gp

Main HQ 2 NZ Div

B2 Ech Gp

2 NZ Div Res Gp

6 NZ Inf Bde Gp

1 NZ Amn Coy

Rear HQ 2 NZ Div

2 NZ Div Adm Gp less 1 NZ Amn Coy

The 8th Armoured Brigade was to form up on the night before ‘D’ day with its head some five miles short of the anti-tank ditch. For the advance through the gap both Divisional Cavalry and King’s Dragoon Guards were to be under the orders of the brigade, and were to form up and move behind it. The gun group would not be able to form up until it had finished firing in support of 30 Corps’ attack. It consisted of 4 Field Regiment (less a troop with KDG), 64 Medium Regiment, RA, 7 NZ Anti-Tank and 14 NZ Anti-Aircraft Regiments (less detached batteries with groups), 36 Survey Battery and Mac Troop. No moves were initially laid down for the remainder of the Division, although 5 Infantry Brigade Group stood prepared to form up on 6 April ready to move forward.

A special ‘task force’ was to move in rear of 50 Division’s attack, and make and mark three gaps in the minefield ready for the passage of 2 NZ Division. It was to consist of:

One platoon of engineers from 8 Field Company

One company of infantry from 6 Infantry Brigade2

Detachment from Divisional Provost Company

and was to be supported by one squadron of Crusader tanks from 8 Armoured Brigade—all under the command of the CRE, Lieutenant-Colonel F. M. H. Hanson.

This special force was given its duties after discussions with 50 Division by the GSO I and the CRE. Both officers came away somewhat perturbed by the method of getting through a minefield adopted by that division. New Zealand infantry had always gone through in extended line closely following the barrage, but 50 Division’s plan was for each infantry company to be led through the minefield in single file by a sapper, using a mine detector, a procedure which occasioned later delays, but which, nevertheless, was based on much experience.

The divisional instruction laid down the axis of advance, and the action to be taken by the leading troops when through the gap, which amounted to reconnaissance to the north and west while the main body of the Division awaited developments. The only new unit was the Greek Squadron of armoured cars, which had been with ‘L’ Force since February. It came under 2 NZ Division on 3 April and was placed with Divisional Cavalry.

The order of march given on page 257 shows, quite unobtrusively, what was claimed as a minor victory for the infantry brigadiers, in that 8 Armoured Brigade was to lead off without its B2 Echelon of transport. It had long been a source of complaint that armoured brigades took their excessively long ‘tail’ with them in close support. It has already been recorded that on occasion the next-following formation was either delayed in moving off, or forced into tactical remoteness.

The only special point in the administrative instructions was that all units would hold rations and water for seven days and petrol for a minimum of 300 miles in first-line vehicles, and rations and water for four days and petrol for 100 miles in second line. There were still two RASC companies with the Division to augment the New Zealand companies. As usual, these simple words cover a great deal of planning by the AA & QMG (Lieutenant-Colonel Barrington), and of hard work by the ASC, ordnance and EME units, to ensure that the Division moved off fully stocked.

Artillery

Because of the vital importance of penetration on this front, 2 NZ Divisional Artillery was to support 50 (Northumbrian) Division in its attack. Two of 50 (N) Division’s three field regiments had been left behind at Mareth to help clear up the battlefield, and only one (124 Field Regiment, RA) was available for the battle. In addition, 2 Regiment of Royal Horse Artillery from 1 Armoured Division would help when not required on other tasks, all regiments being under the direction of the CRA 2 NZ Division. The programme included a barrage by the three New Zealand field regiments, fire on selected targets by the other field regiments and by the New Zealand regiments when not engaged in the barrage, and defensive fire tasks by two medium regiments. The 111th Field Regiment, RA, of 8 Armoured Brigade took no part but remained in immediate readiness to advance with its brigade. On the conclusion of the programme 5 and 6 Field Regiments were to join 5 and 6 Infantry Brigades respectively, while 4 Field Regiment and 64 Medium Regiment, RA, joined the gun group.

After the final objective had been gained, one battery from 6 Field Regiment would fire at intervals along a defined line to mark the bombline for the air force.

For the Ammunition Company it was a period of heavy dumpings – 9000 rounds on 1 April, 9164 on 3 April and 2700 on 4 April; by 6 April it had dumped 300 rounds per gun and kept up full replenishment as well. A second company was obviously needed, but the NZASC had to finish the war in North Africa without it.3

Brigade Plans

The 8th Armoured Brigade decided to advance on a one-regiment front with Staffs Yeomanry in the lead, followed by Tactical Headquarters. But as soon as conditions allowed the brigade would move in ‘A’ formation, with 3 Royal Tanks echeloned back on the left and Notts Yeomanry on the right.

On the day of the attack 5 Infantry Brigade Group was to form up in nine columns on the east side of the tracks (nine in number) which the engineers would prepare from the divisional area to the minefield – all moves to be completed by 11 a.m. The order of march would be:

Advanced Guard as before4

Tac HQ

21 Bn Group

5 Field Regiment

23 Bn Group

28 Bn Group

7 Field Company less dets

Main HQ and B Echelon transport

ADS 5 Field Ambulance

Workshops

There was a degree of decentralisation down to battalions more marked than usual, which led to the use of the term ‘battalion group’. Attachments to each battalion were two troops of anti-tank guns, one section of light anti-aircraft guns, and two platoons of machine guns.

Divisional Activities, 1–6 April

The days preceding the attack were reasonably quiet, except for a little harassing fire on both sides. The 50th Division took over the central sector of 30 Corps ‘ front at 8 a.m. on 4 April, with 69 Infantry Brigade in the line. Responsibility for its artillery support then passed to the CRA 2 NZ Division.

The engineers carried on with their usual multifarious tasks – water supply, repairs to demolitions, maintenance of roads – and there were in addition two special tasks intimately connected with the forthcoming operation. One was the preparation and marking of nine tracks, starting three miles south-west of Metouia and ending on a ridge seven miles farther north, beyond which it was not possible to proceed without coming into view of the enemy. This involved much bulldozing and laying of culverts in wadis that now had water in them. It kept 5 Field Park Company and 6 Field Company pleasantly busy.

The second was to prepare for the task of clearing gaps in the minefield. For this purpose 8 Field Company (Major Pemberton5), less headquarters and inessential transport, assembled south-west of Oudref before dark on 5 April. There it was joined by the tank, infantry and provost components.

For Divisional Cavalry and the infantry the few days from 1 to 5 April were restful on the whole. The cavalry was made up to establishment in Stuart tanks and the Greek Squadron came under its wing. All six infantry battalions carried out the usual activities in a rest period – maintenance, reorganisation, conferences, route marches, tactical exercises, swimming excursions where the sea was near enough – and had some real rest.

Enemy air forces were active in this period, although the bombs dropped were nearly all anti-personnel. The results were negligible.

On the other hand, the activities of the Allied air forces far exceeded those of the enemy and in some directions were devastating. The Desert Air Force attacked landing grounds, enemy positions and transport, and farther behind the battlefront the air forces were dislocating the enemy’s air transport system from Sicily and Italy. At the end of March it was estimated that over 100 transport aircraft were arriving in Tunisia every day, but on 5 April forty were destroyed in the air and 188 on Tunisian and Sicilian airfields, a blow that was well-nigh crippling.

General Montgomery visited 2 NZ Division on 2 April and spoke to all officers and NCOs who could be released from duty; he then moved in turn to Divisional Headquarters, 6 Infantry Brigade, Reserve Group, 5 Infantry Brigade (including KDG and Divisional Cavalry), Divisional Artillery, and 8 Armoured Brigade. On 4 April General Freyberg paid a special visit to 8 Armoured Brigade and spoke to the officers of all three regiments, for he – and others in 2 NZ Division – had much regretted that in press references to the Division the British formations and units under

command had not received their due credit. The visit was much appreciated, for all units gave it a special ‘write-up’ in their war diaries.

The Attack at Akarit

In the 30 Corps ‘ plan of attack 4 Indian Division, probably the body of Allied troops best trained in mountain warfare, planned its own attack within certain specified limits of time and place. To obtain the advantage of surprise the division began by attacking, without artillery support, the southern peak of the Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa massif immediately after dark on 5 April. This peak, the commanding ground, was soon taken, and the division went on to capture both Djebel Mesreb el Alig and Djebel el Meida, a magnificent night’s work that earned both the admiration and the awe of the rest of Eighth Army. By 9.30 a.m. on 6 April the left flank had triumphed and some 3000 prisoners had been taken, nearly all from Spezia and Pistoia Divisions. Two counter-attacks had been beaten off, and the mixed German and Italian troops were never allowed to recover from the audacious and successful assault.

At 4 a.m. on 6 April the artillery throughout 30 Corps began their tasks. All told, there were eighteen field regiments and four medium regiments, a total of 496 guns. From a forward observation post the effect of this weight of artillery was most impressive – overhead a constant sighing as the shells went over, to the rear bright and continuous flashes, to the front a constant crashing of shells, and pervading all the numbing detonation of the guns. The effect on the enemy’s side must have been great.

On the right flank 51 (H) Division reached Djebel er Roumana by 6 a.m., and by 11 a.m. reached the north-west end of the anti-tank ditch beyond, which was a point on the final objective. This

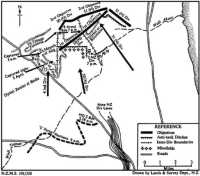

30 Corps’ attack at Wadi Akarit, 5–6 April 1943

was held after a struggle. One battalion from Trieste Division was eliminated, and prisoners were taken from 90 Light Division, one regiment of which counter-attacked at 9 a.m. and for a while held 51 Division, but was in turn driven back.

In the central sector – 50 (N) Division – the minefield and anti-tank ditch formed a genuine obstacle, and the enemy resisted strongly any attempts to cross. By 5.30 a.m. a footing was made towards the seaward end, but further penetration was stopped.

During the rest of the day both 51 and 4 Indian Divisions reached their final objectives. The enemy counter-attacked again at 4 p.m., this time with 15 Panzer Division from reserve, and forced 51 Division back slightly, although not enough to affect the satisfactory position on the right flank. The 4th Indian Division had some hard fighting with yet another regiment from 90 Light, but held all its gains. In his despatch on the campaign General Alexander says of this day that ‘15 Panzer and 90 Light Divisions, fighting perhaps the best battle of their distinguished careers, counter-attacked with great vigour and by their self-sacrifice enabled Messe to stabilise the situation.’ The desperate efforts of these two divisions to stop up

the holes in the front irrespective of where the holes occurred can only excite our admiration. Certainly Montgomery described the fighting as having been ‘heavier and more savage than any we have had since Alamein.’

During the day the Desert Air Force maintained unceasing attacks against transport, gun positions and troop concentrations, but could find few tanks and claimed only one destroyed.

Owing largely to the success of 4 Indian Division in clearing the heights on the left flank and discovering a passable track through the hills so as to avoid the anti-tank ditch which was still delaying 50 (N) Division, Horrocks persuaded the Army Commander to order the advance of 10 Corps. Tanks did in fact move up to the 4 Indian Division area, but guns from the rear of Roumana, firing obliquely, prevented any move forward. But 10 Corps was now taking part in the battle, and 2 NZ Division passed to its command at 11.10 a.m. Until the situation on Roumana, scene of many counter-attacks, was clarified, and the offending guns, probably 88-millimetres, silenced, a further advance depended upon the success of 50 (N) Division.

This division had advanced shortly after 4 a.m. At 5.30 a.m. the gap-making force from 2 NZ Division moved forward some miles and there waited while the CRE and the second-in-command 8 Field Company (Captain Wildey6) went to reconnoitre. When they reached the centre of the position they found that 50 Division was baffled by the minefield and anti-tank ditch and was not taking any special action to overcome the difficulty, but had transferred activity to the ends of the ditch.

The CRE decided to proceed at once with the task of lifting the mines and filling in the ditch, over which two crossings for tanks were to be made. He called forward the supporting tanks and infantry by wireless and ordered the tanks to keep close watch on enemy activities, especially on the mortar and machine-gun posts that covered the ditch. Major Pemberton started his company clearing gaps in the minefield, removing booby traps and trip-wires. D Company, 26 Battalion (Captain Hobbs7), then moved through the minefield, some men taking up positions on the far side of the ditch, while the remainder set to work to fill in the crossings for tanks. It was now about 9.30 a.m. and reports on the state of the work were wirelessed back to Divisional Headquarters. Infantry of 50 Division was now mopping up enemy posts across the ditch and so helping to reduce the volume of fire.

This comparatively slow rate of progress led the GOC to consider taking the Division round the east side of Djebel er Roumana, and up to 11 a.m. he was still undecided. Divisional Cavalry was sent forward on a reconnaissance over the country leading to the east of Roumana, but as the going was not favourable and obvious complications would arise from such a change of axis, it was decided to adhere to the original plan.

One crossing over the ditch was open by 2 p.m. and the second not long after; but there was still considerable opposition from the enemy. It was the generally aggressive attitude of the little gap-making force, the watchfulness of the tanks and infantry and the determination of the engineers that enabled the work to be done at all.

Meanwhile 50 (N) Division, finding enemy resistance strong in the centre, had concentrated on the flanks, and the climax came when infantry supported by tanks from 7 Armoured Division forced their way across near Point 85, the right-hand end of the obstacle, and followed this with an attack westwards along the far side of the ditch.

So one way and another a gap had been made and covered by 50 Division, even though the depth of penetration was shallow and enemy resistance still strong. In the early afternoon 8 Armoured Brigade was ordered forward, and Notts Yeomanry and Staffs Yeomanry moved into the gap, the former using the right-hand crossing just completed, the latter moving at the west end of 50 Division’s sector. Staffs Yeomanry reported at 3 p.m. that they were through. Progress was impeded by fire from defiladed anti-tank guns, but the regiment was jubilant in knocking out a Tiger tank just at the close of day. Notts Yeomanry towards last light moved up on Djebel er Roumana to help 51 (H) Division, which was in difficulty with a combination of 15 Panzer and 90 Light, for until Roumana was fully cleared the gap could not be freely used. The third regiment, 3 Royal Tanks, followed the other two, and KDG closed up to the line of the ditch. But despite the presence of 8 Armoured Brigade within the gap, enemy guns behind the disputed Roumana feature, as well as the commanding positions there, made it impracticable to pass 2 NZ Division through for exploitation.

During the afternoon 4 and 6 Field Regiments moved forward to an area immediately south of the minefield, and were in action there during the evening and night. Fifth Infantry Brigade Group had formed up in mid-morning and finally at 4 p.m. began a move of eight miles, which brought it some five miles short of the

anti-tank ditch. The intention that 21 Battalion should go forward to protect the armour was later cancelled.

Sixth Infantry Brigade Group did not move, but remained at thirty minutes’ notice in its area west of Gabes. There were several air raids on the divisional area, causing small casualties, and at least two aircraft were shot down by Bofors fire.

A new method of ground-to-air control was further improved on at Akarit, having previously been tried out with 2 NZ Division for SUPERCHARGE II. The RAF supplied a small number of armoured cars which controlled aircraft from within visual range of targets. These vehicles remained with 2 NZ Division for the next month. They were the predecessors of what was later called the ‘cabrank’ system, an arrangement by which several fighter-bombers remained overhead at call and were directed individually at a moment’s notice to attack a target, which they could be ‘talked-on’ to.

Position at the End of 6 April

At the end of the day the flanking divisions of 30 Corps had achieved their objectives, although there was still some doubt about the possession of the northern spur of Djebel er Roumana. In the centre progress had been slow. Forward elements of 8 Armoured Brigade were well north of the anti-tank ditch, part of the gun group was forward and in action, and the ditch had been cleared and filled sufficiently for 10 Corps to cross. The 1st Armoured Division had been relieved by ‘L’ Force during the morning and was concentrated south-west of Oudref.

The enemy had in fact prevented a clean break through, but Montgomery clearly had the initiative and therefore decided to launch a ‘blitz’ attack next morning. This was to be made at 9.30 a.m. by 6 NZ Infantry Brigade and 8 Armoured Brigade, with an artillery barrage and extensive air support, from a start line 3000 yards north of the gaps.

Tactical Headquarters of both 2 NZ Division and 8 Armoured Brigade moved forward to the ditch to be in close touch with the forward situation, but for the time being 6 Infantry Brigade did not move. Brigadier Gentry kept himself informed of any developments by visits to General Freyberg and by wireless. The CRA and his staff began preparing barrage tables for the attack.

The Enemy

The 15th Panzer and 90th Light Divisions had done their best to patch up the front. About midday General von Arnim arrived from the north to visit 1 Italian Army; he thought at first that the situation could be retrieved, and even ordered an additional infantry regiment

to be sent down from 5 Panzer Army. Bayerlein was not optimistic. The counter-attack by 15 Panzer against Roumana followed in the afternoon, but despite some measure of success it was the last effort of which the German divisions were capable. All the divisional commanders were then of the one opinion—that the position would be untenable on the following day.

So at 10 p.m. Army Group Headquarters gave the order to withdraw: 90 Light Division was directed to go back astride the main road to the La Skhirra area, 15 Panzer Division to Sidi Mehedeb, and 164 Light Division—still in a bad way with no transport—to the Kat es Satour area. The remnants of Pistoia Division and other Italians were to fall back on the west of 164 Division.

Headquarters 1 Italian Army gave its orders with reference to XX and XXI Corps, which shared the front between them. Bayerlein had been authorised by von Arnim during his visit to give orders direct to all German formations in 1 Italian Army, and for the next week while the withdrawal to Enfidaville was taking place, Bayerlein controlled the German formations as rearguards to the army as a whole.

Advance from Akarit

During the night 6–7 April there were indications that the enemy was withdrawing. By 6.30 a.m. it was clear that the attack by 2 NZ Division was unnecessary, and before 7 a.m. it was established that the enemy had evacuated the Akarit line completely. The battle had thus taken only twenty-four hours, and victory after seven or eight hours had been prevented by the combined efforts of 15 and 90 Divisions, and by the Italian artillery which fought extremely well. The 19th Flak Division, with nine batteries of 88-millimetre guns, from scattered but extremely effective positions, imposed delay quite disproportionate to its numbers.

At 7.20 a.m. the attack by 2 NZ Division was definitely cancelled, leaving the artillery staff to lament some hours of wasted work, and orders were given for the Division to move forward, the passage through the gap being covered by 53 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA, and one troop from 14 NZ Regiment. The armoured cars of King’s Dragoon Guards and the light tanks of Divisional Cavalry led the Division, followed by the heavy tanks of 8 Armoured Brigade. They found a miscellaneous debris of prisoners and enemy material, the prisoners coming from 90 Light and 164 Light Divisions in small numbers and from Italian units more freely. All units in the Allied forces were instructed about this

time that captured enemy artillery equipment was not to be destroyed unless recapture seemed certain. The days when the battlefield swayed violently backwards and forwards were apparently over. The forward elements found no firm rearguard in position, but only a ragged array of infantry, mostly Italian. For once even the Germans had gone back hurriedly, seeming to need a respite in which to recover.

An inspection of the Akarit line served to show how strong it was basically, and also how great was the power of Eighth Army in armour, artillery, and air power when it could overwhelm the defences in one day. During his inspection, the CRA reported that around him he could count twenty-four guns knocked out.

There was no good defensive position between Akarit and Enfidaville, 150 miles farther north, where a mountain range provided a wall for the enemy’s back. The tasks of the opposing forces in these circumstances were, for the enemy, to impose the maximum delay within the power of rearguards without accepting battle; and for Eighth Army, to keep up the momentum of the advance, to do its best to brush rearguards aside without having to deploy, and to capture or occupy landing grounds in a state fit to be used at once. For while the speed of the advance was likely to be much affected by country more enclosed, the air forces were able to range far and wide with ever-increasing intensity, provided they had sufficient landing grounds from which to employ their great superiority in numbers.

For the next six or seven days 2 NZ Division again carried out a pursuit, and while there were compensations, the fact remains that a pursuit is fatiguing, especially as often there appears to be nothing happening at all. To the men in the lorries it meant day after day of start, stop, start, stop, move ahead in low gear, halt for hours, never seeing a glimpse of an enemy. No New Zealand infantry had any fighting during this period, for most units were never deployed. There were one or two scuffles and nothing more. The reconnaissance and armoured forces, however, had a more exciting time, the only serious fighting being carried out by 8 Armoured Brigade, KDG, and Divisional Cavalry, with the first-named the most involved. Soon the supremacy of the tank on the North African battlefield was to pass away—for Eighth Army very soon indeed, only a week ahead—but in this last period, this British formation played its part to the full, and did honour to the New Zealand Division.

Eighth Army had now broken through into an area of country known as the Sahel, a strip of coastal plain varying in width and fertility. It ranged from 20 to 40 miles wide, and became

progressively more mountainous on its western side. Near the coast the ground was fertile, especially so in large areas around Sfax and Sousse. In various spots, mostly about 20 miles inland, there were salt marshes (called Sebkret or Sebkra) which as before were impassable for wheels. While the general trend of the land was flat, the terrain was sufficiently accidented, albeit in a minor way, to make the going often very bad. The fertile areas were much enclosed by cactus and other hedges and intersected by narrow lanes bordered by loose stone walls.

So much for the cold facts; but there was another aspect which had much appeal to the men. It was springtime, and the country was largely cultivated, with areas of olive plantations and occasional palm groves, and with green crops of wheat and barley. And even more attractive were the masses—a veritable carpet—of wild flowers, red, blue, white and yellow, poppies and daisies. Even dandelions and thistles were pleasant to see. To the men of Greece and Crete the olive groves brought back memories of those early days.

The troops were delighted with the change of scene: there was ample water, and everyone knew that the end could not be long delayed. No matter what was said about boring days of travel, it was a relief that the days passed without casualties.

On 7 April, at the outset of the advance, Divisional Cavalry exploited to the north-west behind Djebel Tebaga Fatnassa while King’s Dragoon Guards advanced on both the east and west of Djebel er Roumana. The forward elements of these two regiments reached Wadi er Rmel at 8.45 a.m., meeting only light opposition, and at 11.15 a.m. captured the eastern feature of the low hill Kat Zbara.

This penetration alarmed the enemy, and at noon some Tiger tanks from Army Reserve were placed under 15 Panzer Division with orders to attack the British armour (8 Armoured Brigade) which was close behind the reconnaissance forces. Thus it is not surprising that the advance soon ran up against real opposition and the artillery had to be deployed. The tanks of 8 Armoured Brigade in hull-down positions engaged the enemy, helped not only by 4 Field Regiment but by two guns of Q Troop, 34 Anti-Tank Battery, equipped with the new 17-pounders, which now opened fire for the first time.

This combined effort halted the enemy. By 6 p.m. the enemy tanks, of which some twenty-two had been seen (including the Tigers), were withdrawing, having offered the only serious resistance encountered this day, and having checked progress for some hours. One Tiger at least was knocked out, but other enemy losses are not known.

But while two of the three regiments of 8 Armoured Brigade were held up in the area north of Kat es Satour, 3 Royal Tanks and part of KDG succeeded in pushing forward along the eastern side of Sebkret en Noual, and at 5.30 p.m. cut the road from Mahares to Maknassy and El Guettar at a point east of Rir er Rebaia, and took many prisoners and destroyed much MT. The Division’s advance had in fact cut across the line of retreat of the German forces that had been facing the Americans at El Guettar and Maknassy, and had been too quick for some of the enemy. This advance of 3 Royal Tanks, and the earlier withdrawal of the enemy tanks, had been helped on the left of 2 NZ Division by the arrival of 2 Armoured Brigade from 1 Armoured Division, which, once through the gap at Akarit, had made good going. Its cavalry regiment (12 Lancers) took over part of the front being covered by KDG.

The arrival of this force at Rir er Rebaia alarmed the enemy, and it then transpired that the Italian troops who were intended to fill the gap in the line east of Sebkret en Noual had either never gone there, or were so disorganised as to be useless. So once again a force from 90 Light Division was rushed to that flank, together with elements (probably unarmoured) from 21 Panzer Division, now retiring from El Guettar.

Each day of the campaign in North Africa made history of some kind, but on this day it was something to appeal to the popular imagination, for at 3.30 p.m. while moving forward 12 Lancers made contact with desert patrols of American troops—the first contact between the two armies of Eighteenth Army Group.

On the right of 2 NZ Division 30 Corps pushed north along the coast road with 51 (H) Division and 23 Armoured Brigade, and by last light were just short of Skhirra. Between these forces and 2 NZ Division, 22 Armoured Brigade from 7 Armoured Division advanced on the same level. The whole advance of Eighth Army was closely supported from the air, increasingly so as the day went on and targets became more plentiful. The best targets were found along the road and tracks from El Guettar, where the enemy was in full retreat.

It had been quite a good day for all, but the time had come for 2 NZ Division to establish a firm base for the night, and for this purpose 5 Infantry Brigade came forward and formed a gun line in an arc some four miles to the north-east of Kat Zbara.

The 23rd Battalion was to have been on the left of this arc, but at 6 p.m. the GOC from Tactical Headquarters ordered it to push out well to the north and get astride the Maknassy road at Rir er Rebaia, with a view to blocking the enemy retreat from the west. It

appears that for some reason Headquarters was not aware that 3 Royal Tanks had already cut the road.

Lieutenant-Colonel Romans, in the words of the Brigade Major, ‘took 23 Battalion off like a rocket’, and in the faded light the two rear companies were left behind and had to wait until daylight. As it happened, the country over which the battalion advanced was quite unsuitable for night travel, for the route lay along the shore of Sebkret en Noual, where the marshy ground quickly brought the move to a halt, despite frantic efforts by all ranks to keep vehicles moving. After some hours’ struggle the CO finally decided at 3 a.m. on 8 April to go no farther, and ordered the troops to bed down and wait for daylight.

The other two battalions of 5 Brigade supported by 5 Field Regiment duly took up their positions for the night. At last light (about 7.30 p.m.) 8 Armoured Brigade was concentrating forward on 3 Royal Tanks—the brigade’s tactical headquarters did not reach the laager until after midnight—Divisional Cavalry was north-west of 5 Infantry Brigade, and Tactical Headquarters of the Division was on Kat Zbara. Sixth Infantry Brigade Group kept moving until about midnight it reached Wadi er Rmel.

The Division made a good haul of prisoners during the day, although exact figures are not known, but Divisional Cavalry recorded 15 Italian officers and 1204 other ranks, and 12 German officers and 111 other ranks. Twenty-seven guns of various calibres had been sent back and many vehicles. It was noticeable that while the Italians were weary-looking and ill-clad and only too glad to be quit of the war, the Germans were better-clad, bore themselves well, and were unshaken in morale.

The enemy had done his best during the day, but even his best could delay Eighth Army only temporarily. By the end of the day he was in general retreat to the line Chebket en Nouiges - Sebkret Ouadrene. The conduct of the withdrawal had been rationalised by this time, for all Italian troops were sent straight back to Enfidaville, leaving the German formations to impose delay.

8 April

At first light KDG, Divisional Cavalry and 8 Armoured Brigade moved off again. Notts Yeomanry and 3 Royal Tanks went to the high ground towards Chebket en Nouiges, and there forestalled enemy tanks on the feature, the defenders again being 15 Panzer Division and part of 21 Panzer. There were in fact still some enemy troops, including tanks, to the south of Chebket en Nouiges, and the troop of artillery with KDG had some good shooting, destroying one tank and forcing others to withdraw. But the enemy screen of

tanks combined with anti-tank guns proved quite effective, as so often before, and slowed down the advance of 8 Armoured Brigade. It was not until the afternoon that there were signs that the enemy was again thinning out, for tanks and transport were moving north, probably hastened a little by the pressure of 1 Armoured Division against Mezzouna farther west. Here a reconnaissance group of 3, 33 and Nizza Reconnaissance Units was trying to fill the gap left by the disintegration of the Italians.

Both Divisional Cavalry and KDG had an exhilarating time, the roving movements of the latter giving great scope to their supporting troop of artillery, which finished the day in a position on the railway line well in advance of Chebket en Nouiges.

There was enough enemy resistance for the gun group to be brought into action by 11.30 a.m. from positions behind the Chebket, and here a 17-pounder was used by the Division for the second and last time against tanks in North Africa. A weapon of this special nature with such great hitting power had been long and eagerly awaited by Eighth Army, but it had come so late that it was hardly used or needed.

Meanwhile 23 Battalion extricated itself from the marshes – helped by tanks from 8 Armoured Brigade – and by 6.45 a.m. at last reached the road near Rir er Rebaia. Even at this late stage there was still enemy transport about, and hostile action of various kinds by everyone from the CO downwards resulted in eight vehicles being destroyed and in vehicles and equipment being captured. These came from 10 Panzer Division, lately opposite Maknassy.

The remainder of 5 Infantry Brigade started to move forward at 8 a.m. but found the going difficult. It was halted some three miles south-east of the Rir er Rebaia crossroads, and stayed there during the early part of the afternoon awaiting a move that night. At 2 p.m. its main headquarters and 21 Battalion were attacked by five enemy fighters, and one man was killed and eight wounded, but Bofors shot down one fighter and Spitfires got another.

As all the indications were that the enemy was continuing his withdrawal, Lieutenant-General Horrocks decided to push ahead after dark on an axis running due north. The New Zealand Division would be the spearhead, but 1 Armoured Division and ‘L’ Force still farther west would conform. By late afternoon the enemy had begun to withdraw to a line some 20 miles farther north. The rearguards of 1 Italian Army, namely 90 Light, 164 Light, and 15 Panzer Divisions (the last-named reinforced by part of 21 Panzer Division) now covered a stretch of country – it cannot be called a line – running inland from the coast for about 25 miles. To their

west there was still the reconnaissance group, but now both 10 and 21 Panzer Divisions had joined and were in the area north-east of Maknassy.

It becomes increasingly difficult to pin-point further the various enemy formations and units. Enemy material at divisional level ceases to exist after the end of March, and the war diaries of either Army or Army Group Headquarters are of little assistance in filling in detail. This will serve to explain why sometimes in the days that follow it is not possible to be certain which formation was opposing 2 NZ Division.

However, the general conclusion about the enemy situation at the end of 8 April was that, while there was a fairly continuous line on 1 Italian Army’s front, farther west there were large gaps.

To return to 2 NZ Division – with the object of carrying out a night advance, 8 Armoured Brigade was withdrawn early in the afternoon for a few hours’ rest, while arrangements were made to form a special battle group of 8 Armoured Brigade, KDG, Divisional Cavalry and 5 Brigade Group. The remainder of the Division was to remain at its last-light locations, all south of Chebket en Nouiges. Although progress had not been rapid, more than 500 prisoners had been captured, including the GOC Saharan Group, General Mannerini, and his staff. This last capture gave some excitement to 28 (Maori) Battalion, through the hands of which the prisoners were passed. It compensated for a day in which the battalion had ‘led the brigade column in an advance that was mostly halts.’8

At 5.45 p.m. the battle group moved off with 8 Armoured Brigade leading, followed by 28 Battalion (under command 8 Armoured Brigade), Divisional Cavalry, 5 Brigade, and with KDG for once bringing up the rear. The advance was uneventful, and by 11 p.m. the leading tanks of 8 Armoured Brigade had reached the forward slopes of Toual ech Cheikh, over 20 miles due north from Chebket en Nouiges. The Maori Battalion mounted flank guards on both sides of the axis, and the rest of the column bedded down a few miles farther south – except that, as usual for sappers, part of 7 Field Company spent most of the night working on crossings over watercourses.

9 April—to the Sfax-Faid Road

This advance penetrated into a gap between the right flank of 1 Italian Army (as represented by the German rearguards) and 10 and 21 Panzer Divisions, now collecting themselves after their withdrawal from Maknassy and El Guettar. It took the enemy by

surprise, disrupted his line occupied only the evening before, so that he still had troops wandering about south and east of Toual ech Cheikh.

At first light it had been intended that 28 Battalion should consolidate on the feature, but while Lieutenant-Colonel Bennett was on reconnaissance Brigadier Harvey passed word that the enemy was moving northwards and 8 Armoured Brigade was already pushing on. The 28th Battalion therefore reverted to the command of 5 Infantry Brigade, and rejoined the column.

King’s Dragoon Guards went into the lead, covering the whole front, moved rapidly, and were on the road from Sfax to Faid by 11 a.m., although they could not block it firmly at this time. The 8th Armoured Brigade followed up to the northern slopes of Djebel et Telil, and was on a line from there to the north end of Sebkret Mecheguigue. Tactical Headquarters 2 NZ Division was at this time (midday) just south of Telil. For a while the GOC considered sending part of KDG with extra artillery round the west side of the Sebkret to outflank enemy tanks which could be seen to the north, but about this time 2 Armoured Brigade came up the east side of the Sebkret and prolonged 8 Armoured Brigade’s line to the west.

The gun group—4 Field Regiment and 64 Medium Regiment—was then called forward and deployed on the south and east slopes of Telil, and was there joined by 111 Field Regiment from 8 Armoured Brigade. The gun area was protected by 31 Anti-Tank Battery on both the front and flanks, A Troop being on the left.

About 2 p.m., just as the portées of A Troop had unloaded and were driving away, some thirteen tanks appeared at very short range from a depression to the west, heading straight for the gun positions. For a moment it was thought they were American, but they opened fire on the portées and A Troop went into action. One gun stopped a Mark IV Special before it was put out of action, and the No. 1 of another gun, Bombardier Keating,9 despite casualties to his gun crew, got his gun firing and accounted for two and possibly three tanks, even though for part of the time he had to do all the loading, laying and firing himself. Staffs Yeomanry then appeared and forced the enemy to withdraw. The 4th Field Regiment had adopted ‘tank control’ and was ready to repel boarders, but in the end the enemy did not come close enough. One quad of 111 Field Regiment was destroyed, and damage caused to guns of 31 Anti-Tank Battery. In addition to the tanks knocked out by A Troop, 64 Medium Regiment destroyed two by shellfire, and

Staffs Yeomanry another two. The 2nd Armoured Brigade on the left joined in and helped to drive the enemy away to the north.

Despite all reconnaissance, it appears that the enemy tanks had been bypassed, and had waited until a good target offered. They came either from 21 Panzer Division or from an extra tank battalion with the division. The whole force appears to have had about thirty-seven tanks, of which twenty-five attacked 2 NZ Division, while twelve were on the front of 2 Armoured Brigade. But good anti-tank defence had foiled the attack.

Meanwhile Divisional Cavalry was watching odd enemy vehicles, including tanks, in the area south-east of Telil, some miles behind the 2 NZ Division spearhead. As the day wore on these enemy forces became an embarrassment, and finally 26 Battalion was ordered to send out a mobile patrol of carriers, mortars, anti-tank guns and machine guns. This patrol in the end surprised two enemy tanks, destroyed one and drove the other away, and by this time it was dark.

By last light the enemy was still on the Sfax–Faid road, but his tanks had all moved off to the north. The enemy had now heard the alarming news that First Army had broken through towards Kairouan, so threatening the rear of all his forces facing Eighth Army. Orders were at once given by Army Group Headquarters for 1 Italian Army to go straight back to a line north of Sousse, but a combination of a shortage of petrol and a desire to have a little longer to remove ammunition stocks from Sfax led Bayerlein to lay down a withdrawal to a line running east from Sebkret mta el Rherra, leaving rearguards to cover Sfax. Bayerlein’s words on this date are, ‘The troops (some of them tired out, some of them separated from their units) disengaged from the enemy with great difficulty, and retired to the new line, followed up closely by the enemy.’

Towards last light 2 Armoured Brigade took over from 8 Armoured Brigade on Djebel et Telil, and the latter side-slipped a few miles to the east, with KDG in company and Divisional Cavalry just behind, all in preparation for another night move to the Djebel bou Thadi. The infantry of the Division was by this time well stretched out beyond Djebel Toual ech Cheikh, with 26 Battalion from 6 Brigade slightly displaced to the east as a safety precaution. Practically the whole day’s advance had been through crop lands and olive groves, and the going was heavy.

Poor visibility had limited the operations of the air force, and in any case targets were becoming rare. The enemy made a few raids on 2 NZ Division, but casualties and damage were slight.

First Army Front

On 7 April 9 Corps launched the prepared attack against the pass at Fondouk which led out of the hills. On 8 April it captured Pichon, and on 9 April cleared Fondouk and forced the pass beyond. It was now out of the hills with an open road in front of it and Kairouan only 20 miles away, so that the enemy’s alarm is understandable.

The 2nd US Corps was now squeezed by the ever narrowing front, and by 9 April was on its way to the extreme northern flank of the Allied line next the sea, where it was to join other American units and prepare for its part in the final phase.

10 April – Cross-country Journey

The idea of a night advance, and indeed of any advance due north, was abandoned quite early, and at 3.40 a.m. on 10 April was replaced by an advance by 2 NZ Division to the north-east towards La Hencha (on the main road north of Sfax), with the object of cutting off the troops opposing 30 Corps in Sfax. The 4th Light Armoured Brigade would come up on the left of 2 NZ Division, and farther left would be 1 Armoured Division and ‘L’ Force.

So at 6.30 a.m. the GOC held a conference about the day’s move. King’s Dragoon Guards, Divisional Cavalry and 8 Armoured Brigade were to lead, on an axis via Triaga and La Hencha. The change in plan delayed the start until 9 a.m., and in any case at 8.15 a.m. word was received that Sfax had been entered, almost inevitably, by 11 Hussars of 7 Armoured Division. However, the plan was not altered, and the advance continued, but contacts with the enemy were confined to brushes with the tail of his rearguards. Air reconnaissance discovered little south of Sousse; nevertheless the enemy’s demolition parties were active, and KDG reached La Hencha at 11.30 a.m. just as the main road to the north was blown – and badly blown – where it crossed a marsh. All that could be done was to send a few shells after retreating MT. King’s Dragoon Guards ended the day deployed on an arc from the main road north of La Hencha to the coastal road at Djebiniana, where it was in touch with 7 Armoured Division.

Divisional Cavalry made no contact with the enemy, but managed to penetrate off the roads through the gap between Sebkret mta el Rherra and Sebkret mta el Djem, despite the very enclosed nature of the country. They ended the day at El Djem itself, well in the lead.

Staffs Yeomanry, by dint of much cross-country work, also got through the gap between the two sebkrets, to within seven miles of El Djem, but was then almost out of petrol because wheeled transport was held up at the large ‘blow’ north of La Hencha.

Sappers of 6 and 7 Field Companies worked on this all afternoon, and indeed through the following night. Meanwhile other engineers were sent during the day to report on landing grounds north-east of Telil. The party was bombed just as it was leaving one ground, and two men were killed and eight wounded. This episode showed the importance that both sides attached to advanced landing grounds, we to use them, and the enemy to stop us. It is again an example of the active part played by the engineers.

The gun group was partially deployed south of La Hencha and got off some rounds at straggling enemy transport. Infantry had no action of any kind, and most unit diaries comment on the pleasant move among green crops and wild flowers and under olive trees.10

By the end of the day 10 Corps was in a long arc from Djebiniana through La Hencha, north of Sebkret mta el Rherra, north of Djebel bou Thadi and Djebel Kordj to Kefer Rayat. The only forward element of 30 Corps was 11 Hussars, which in its usual style had a patrol on the coast as far north as Chebba. From now on, however, Eighth Army operated with one corps only, leaving Headquarters 30 Corps planning the next stage, the invasion of Sicily. In any case it was time to give some thought to the administrative position, for the army was still dependent on supplies from Tripoli, now some 300 miles away. It was an urgent matter to get the port of Sfax into order.

The 6th Armoured Division of 9 Corps was now fighting hard at the gates of Kairouan, and this was the enemy’s greatest danger. The 21st Panzer Division had already been moved there and now 15 Panzer Division was sent back to the defile between Sebkra Kelbia and Sebkra de Sidi el Hani, so blocking the direct road from Kairouan to Sousse. Rearguards south of this line were provided by 90 Light Division on the coastal strip and 164 Light Division farther inland. It was commonly remarked that Eighth Army would be chasing ‘90 Light’ to the end of time.

The 15th Panzer Division had supplied the rearguards opposing 2 NZ Division, but had now moved to its new task. Except for some small unarmoured elements, the Division was not again to meet 21 Panzer Division which, with 10 Panzer Division, was transferred to the First Army front.

11 April—Rest and no Rest

The advance of 30 Corps ended at Sfax, but 4 Indian and 50 Divisions were later ordered north from Akarit to join 10 Corps. The 1st Armoured Division was halted and passed to the direct command of Eighth Army, mainly because 6 Armoured Division

was now on the west flank. Troops of these two divisions made contact during 11 April, and for the first time Eighth and First Armies formed a continuous line. The 6th Armoured Division entered Kairouan about the same time.

The enemy had obviously won the race back to Enfidaville and there was no chance of any spectacular round-up, so a little time could be given to rest and reorganisation. At 5.30 a.m. on 11 April 10 Corps advised 2 NZ Division that the advance on Sousse would not take place until 12 April, and all units were told that there would be rest and maintenance for the next twenty-four hours, except for the patrols in contact with the enemy. To hear the word ‘rest’ doubtless sounded most pleasant, but its hearers must have wondered later if they had heard aright.

The first sign of disenchantment came as early as 11 a.m., when the GOC held a conference, and 8 Armoured Brigade and the gun group learnt that they were to move by road that afternoon as soon as the demolition at La Hencha was filled. For one way and another it appeared that movement on the roads would be slow, and the Division was still 50 miles from Sousse. However, the remainder of the Division would not move until 12 April, and would advance across country.

Meanwhile KDG kept touch with the enemy, although it was late afternoon before actual contact was made with light rearguards south of Sousse. There were demolitions on many roads, including a large one on the main road at Wadi Kerker, 14 miles north of El Djem, necessitating another SOS for engineers.

The 8th Armoured Brigade moved forward in the afternoon, making use of more than one road. Units on the main road managed to bypass the Wadi Kerker ‘blow’ and the brigade laagered north and north-east of this, having for once seen nothing of the enemy. The gun group did not in the end move until after 7 p.m.; 4 Field Regiment went on to Wadi Kerker, but the rest of the group halted just clear of La Hencha.

Divisional Cavalry spent the day in the El Djem area, no doubt admiring, as did all the troops, the magnificent ruins of the Roman amphitheatre there.11 At the landing ground just north of the village the enemy’s only attempt to prevent its use was frustrated, for seven fused bombs laid in trenches on the runway were found by engineers and were later blown up. The filling of the La Hencha crater turned out to be a prolonged task, and even by 12.30 p.m. only a single line of traffic could pass, and 6 Field Company had to stand by for continuous maintenance.

At midday disenchantment was complete when the Division was warned to move. Fifth Infantry Brigade had scant time to wind up all the ‘make and mend’ activities and move by 3 p.m. It bypassed La Hencha, covered 25 miles in just over three hours and halted off the road north-west of El Djem. Sixth Infantry Brigade closed up as far as La Hencha.

The GOC attended a conference at 10 Corps at 3 p.m. to hear of future plans. On 12 April 2 NZ Division was to capture Sousse and close up to the Enfidaville line with 4 Light Armoured Brigade, ‘L’ Force and some heavy tanks on its left. The 4th Indian and 50th Divisions would arrive from Akarit about 15 April with the role of the immediate capture of the enemy’s line.

But meanwhile the enemy was moving too fast for the pursuing forces, and early on 11 April had withdrawn from Sousse except for small rearguards. The 90th Light Division retired to high ground about six miles north of Sousse, 164 Light to Sidi bou Ali, and 15 Panzer to the area between Sidi bou Ali and Sebkra Kelbia, with a reconnaissance party on the Enfidaville-Kairouan road at the south-west end of the Sebkra. The enemy was now nearing the end of the forced withdrawal from Akarit, and had behind him a really strong position, where Italian troops had already been working on defences.

12 April—the End of Desert Fighting

After a quiet night 2 NZ Division advanced on Sousse at first light on 12 April, and at 7.45 a.m. the first KDG patrol entered the town. Engineers at once disarmed prepared charges on the traffic bridge over the railway on the northern outskirts of the town. The inhabitants gave the troops an enthusiastic welcome, producing flowers, wine and brandy amidst much hand-clapping and cries of ‘Vive! Victoire!’ They reported that the enemy had left only five minutes before, and at 8.45 a.m. Tactical Air Reconnaissance reported the tail of the rearguard as only four miles north of the town. In fact, not long afterwards Divisional Cavalry patrols ran into the rearguard in position on high ground near Akouda, where it was using a number of guns, together with mines and wire. Prisoners confirmed that it was part of 90 Light Division.

Cavalry patrols were then directed to the west via Kalaa Srira in an effort to turn the enemy position, and during the day, helped by steady artillery support, gradually worked round to the north, although it was slow going. In the late afternoon 8 Armoured Brigade caught up, having pushed on throughout the day although slowed down by various ‘blows’. The brigade bypassed Sousse and also came up against the enemy rearguard. However, pressure was

maintained and towards last light the enemy was obviously thinning out. At 7.30 p.m. the whole position had been turned, and 8 Armoured Brigade went on, Notts Yeomanry finishing up only 3000 yards short of Sidi bou Ali, with Staffs Yeomanry close behind. Divisional Cavalry and King’s Dragoon Guards disengaged and laagered west of Sousse.

The enemy rearguard had achieved its purpose and had delayed the advance for many hours.

For the rest of the Division the day had been one of hard going with no action. Progress across country was difficult, and in most places the ‘going’ was impassable to wheels, so that traffic was confined to the roads, which the enemy had mined in many places. At one critical point north of Msaken, for instance, the road was both mined and cratered heavily, the crater being 64 feet wide. It was 3 p.m. before the engineers had filled it in.

Fifth Infantry Brigade Group moved at 8.15 a.m. in nine columns off the road, but at Wadi Kerker the broken nature of the ground forced it into single column along the road, and at one stage it became badly strung out. By 4.50 p.m. Headquarters and 28 Battalion neared Akouda, having bypassed Sousse, but were then held up while the last of the enemy rearguard was cleared away. This group then passed through Akouda and was at last joined by its two strayed battalions, which had moved through Sousse. The countryside was a mass of narrow lanes among thick cactus hedges and olive groves, and it was very easy to take the wrong turning. The 21st Battalion official history says: ‘On the afternoon of 12 April 21 Battalion passed through Sousse. Again it was at the rear of the column, but it came in for its share of “Vives” from the populace—”Vive les Anglais” and “Vive les Enzed”—which accompanied odd bottles of wine given to the troops and bundles of flowers pressed on the grinning drivers. This was running a war on the right lines, and the battalion hoped to be at the head of the column at the next town.’

By last light the Division was stretched out for 60 miles, from north of Akouda to La Hencha. Maintenance had been normal as usual, but the platoons of Petrol Company were working hard to keep supplies going. Petrol was all that mattered, for rations offered no difficulty, casualties had been slight, and ammunition expenditure negligible.

Despite the check at Akouda it was a useful day on the whole, for landing grounds had been overrun before damage could be done to them, and the little port of Sousse was undamaged and workable. There was no enemy interference all day.

On the west flank 4 Light Armoured Brigade moved round the west of Sebkra de Sidi el Hani and kept touch with 2 NZ Division’s patrols.

Late on 12 April 10 Corps issued a directive about the first approach to the Enfidaville line, saying that it was expected the enemy would hold an outpost position east and west through Enfidaville, with the main position running west from Bou Ficha on the coast. Tenth Corps was to close up to this line, with 2 NZ Division on a front from the coast to west of Takrouna, 4 Indian Division in the centre opposite Djebel Garci, and 7 Armoured Division on the left.12 For the first time for Eighth Army an inter-army boundary was defined—a dividing line between 7 Armoured Division and 19 French Corps, the right-hand formation of First Army.

General Freyberg then decided that the Division must progress a little farther before 13 April, and the outcome of various conferences and orders was that 28 (Maori) Battalion was to occupy Sidi bou Ali, but was to be well clear of the road by first light so as not to block 8 Armoured Brigade, which would be passing through, with 21 Battalion in support.

At midnight 12–13 April 28 Battalion set off, but A Company (Major Porter) debussed short of the town ready to go forward on foot. However, the battalion intelligence officer (Lieutenant Wikiriwhi13) volunteered to reconnoitre by carrier, and in due course reported the village clear. A Company carried on for another four miles, and when almost at the end of its task ran into the 90 Light Division rearguard. In the ensuing skirmish the company destroyed a gun portée, killed two of its crew, wounded two more and took two prisoners. The company had one man killed and two wounded. By 5 a.m. all companies were in areas off the road, where they remained until they rejoined the 5 Brigade column later in the day. There was some slight enemy shelling at first light, but no casualties.

On 13 April 2 NZ Division came up against the outposts of the ‘Enfidaville line’, which lay along the northern limit of the Sahel, for at this point the mountains on the west ran down to the sea, leaving only a very narrow strip of flat land along the water’s edge. The Enfidaville line marked the end of desert fighting for Eighth Army.