Chapter 15: The End in North Africa

THE three weeks following the capture of Takrouna were some of the most irritating and frustrating ever to befall 2 NZ Division. There was a consciousness that the campaign could not be brought to an end on the front of Eighth Army, and that further efforts to effect this would be pointless. The final disappointment was to miss participating in the spectacular advance farther north, by remaining on the holding front while others had the immense exhilaration arising from a triumphant and speedy victory.

After ORATION, there was briefly some doubt in the minds of both the Army and Corps Commanders how best to implement the Army Group plan, for the result of attacking into the hills head-on had not been encouraging. Late on 21 April in a telephone conversation with General Freyberg, General Horrocks said that the Army Commander thought the best thing to do would be to advance astride the coast road for four or five thousand yards, and then swing westwards into the hills – still of course with the intention of getting to Bou Ficha and Hammamet. But this policy was not adopted. There was, however, no intention of persisting with ORATION, and the basic policy for the immediate future finally became that of enlarging the entrance into the coastal strip north of Enfidaville, then to enlarge this encroachment farther north by pushing to the west in a series of piecemeal operations. Small wonder, however, that no one liked this scheme, for the configuration of the ground was such that Eighth Army, with diminishing forces, would be hard put to it not to finish up in a complete bottleneck, where it would be no better placed to act as anvil to First Army’s blows than at Enfidaville. There was so far little sign that the Eighth Army had drawn enemy troops from the western face, indeed quite the reverse, for on 24 April the armour of 15 Panzer Division was identified in the north.

General Montgomery was still concerned with the planning for Sicily. When it was clear that ORATION had failed, he left Eighth Army to extend its positions at Enfidaville while he visited Cairo, where, since 13 April, he had been represented at the planning conferences by his Chief of Staff, de Guingand. Montgomery was

away between 23 and 26 April1 and the responsibility for the activities and planning within Eighth Army for this period was carried by General Horrocks. Headquarters 30 Corps was being rested prior to the Sicily campaign, and General Leese was in Egypt.

2 NZ Division after Takrouna

When, on 21 April, General Freyberg heard Horrocks’s account of the Army Commander’s intentions, he said that his own appreciation had been the same that morning, but he now wondered if it would not be better to thrust north-west from Takrouna. Fifth Infantry Brigade would try to complete its objective within the next twenty-four hours, and after that it would depend on where the best gun positions could be found. However, during the night of 21–22 April, 25 Battalion made a special reconnaissance of those parts of Cherachir not yet occupied, with the idea of later making a silent attack by one company to secure the whole feature. But the information brought back led Lieutenant-Colonel Morten to think that the attack could not succeed, and after discussion with Brigadier Kippenberger it was cancelled. After this no attempt to capture Cherachir, far less Froukr, was made by 2 NZ Division.

During the night engineers from 7 Field Company cleared mines in 28 Battalion area, and also on the road from Takrouna village to the Zaghouan road, so enabling supporting arms to be sent up to Captain Roach on Takrouna.

On 22 April there was little activity on the part of 2 NZ Division, except for some artillery fire on known enemy positions. Very little observed shooting was done owing to poor visibility, which not even the Air OP could overcome. The main air offensive was crippled this day by bad weather. Enemy artillery and mortars were very active, the bulk of the fire being against Cherachir and Takrouna. The 25th Battalion was severely shelled from time to time during the day, and had five killed and nine wounded, and fire on Takrouna was continuous. Altogether the shelling on 5 Brigade’s front was the heaviest yet experienced.

On this day 8 Armoured Brigade was withdrawn for rest and maintenance. In the morning the GOC conferred with the commanders of 5 and 6 Brigades, and decided that 6 Brigade should take over the whole divisional front on the following night, but in the evening this move was cancelled, and 5 Brigade stayed in the line for another twenty-four hours, at the end of which time it was in any case to be relieved by a brigade of 51 (H) Division.

This was Brigadier Parkinson’s first day in command of 6 Infantry Brigade. The 28th (Maori) Battalion also had a new commander, for Major Keiha2 arrived from the LOB camp near Tripoli and took over.

During the night of 22–23 April 6 Infantry Brigade sent out patrols as preliminaries to a proposed operation to capture the Srafi feature, north of Djebel el Hamaid. Some reorganisation took place within 5 Infantry Brigade where 25 Battalion relieved 21 Battalion on Takrouna, and at the same time bowed to the inevitable, gave up the position on Cherachir, and withdrew to the northern slopes of Djebel Bir and Takrouna. The shelling on Cherachir had been too intense, Kippenberger considered, to be suffered a second day to no good purpose.

The 10 Corps programme of reliefs started this night with the relief of 4 Indian Division by 51 (Highland) Division. Next day, 23 April, representatives from 152 Brigade of 51 (H) Division arrived to prepare for the relief of 5 Infantry Brigade, which was carried out after dark. The 25th Battalion suffered casualties from mines and booby traps still in the area, but 21 and 28 Battalions were relieved without loss, and the whole changeover was complete by 3 a.m., 24 April. The 25th Battalion then reverted to 6 Infantry Brigade, while 5 Brigade assembled in a rest area about seven miles south of Enfidaville. It had experienced one of its most difficult assignments, had been only partly successful, but had produced in the capture of Takrouna a feat which had caught the attention of the whole army.

There had also been a change on the east flank of 2 NZ Division, where 56 (London) Division took over from 50 (Northumbrian) Division. The 201st Guards Brigade of 50 (N) Division remained in the line, however, passing to the command of the London Division. This last formation had come all the way from Iraq direct into action, travelling 3223 miles in 30 days, probably a record in approach marches. The division was now seeing operational service for the first time.

After the relief of 5 Brigade the frontage of 2 NZ Division was that of 6 Brigade only, with its forward defences unchanged, running in a semicircle from Point 63 (east of Hamaid en Nakrla) to the Zaghouan road north-east of Djebel Bir.

In the evening of 22 April General Freyberg had agreed to push forward the 6 Brigade line, first for 2000 yards on the night 23–24 April, and then for an unspecified distance on the night 24–25

April, both advances to be without armoured or artillery support in the hope that such ‘peaceful penetrations’ would be successful. This was not considered too venturesome, for a marked enemy map captured on Takrouna had shown that the enemy’s main line was still some distance to the north.3 The GOC said beforehand that it was not likely that much opposition would be met on the first advance, but that the second might be a greater problem. He was right.

These advances were in fact the first measures in the new policy of widening the ‘throat’ of the coastal strip, and were to be followed by similar attacks. The object was to obtain a position from which to attack the main enemy line in the Kef Ateya – Sidi Cherif area.

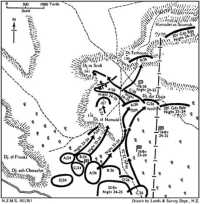

The objectives given to battalions for the first night’s advance were, for 26 Battalion, Djebel dar Djaje, and for 24 Battalion, Djebel el Hamaid. Both battalions were to dig in deeply on their objectives, and 24 Battalion was to be sited with a view to repelling attacks from the north-west. The axis of advance was now running almost parallel to the enemy’s front, and 24 Battalion was in effect open to being ‘raked’ from its left flank. Each battalion was to have an additional platoon of machine guns. Two squadrons of tanks from Staffs Yeomanry were to take up positions about a mile south-east of the new line ready in case of an immediate enemy counter-attack. The 201st Guards Brigade would also be advancing on the right.

At 10 p.m. the two battalions advanced, each with two companies only, and occupied their objectives without opposition. Supporting arms were in position before 1 a.m. on 24 April. The 24th Battalion exploited forwards to Point 107, and had a short exchange of fire with an enemy patrol during which one man was wounded, the only casualty in either unit. Junction with 201 Guards Brigade was made by 26 Battalion just to the east of Djebel Djaje, and the tanks were in their appointed position.

Little movement was seen after daylight, but enemy shelling and mortaring were severe, for good use was made of Djebel el Froukr for observation purposes, as it overlooked the 6 Brigade salient. The feature was first ‘stonked’ several times, but the summit was razor-edged and a difficult target. At 2.15 p.m. the CRA fired a concentration from fourteen regiments, which brought heavy retaliation directed on Takrouna. Lieutenant-General Horrocks observed this concentration from a vantage point on Takrouna, which he was visiting, and was pinned to the ground by the enemy’s shellfire.

During the day Notts Yeomanry moved out north-east of Enfidaville in support of 201 Guards Brigade, and in the course of the operation its commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel J. D. Player, who had done much in the support of 5 Brigade, was killed.

At 9.30 a.m. a conference was held at Headquarters 2 NZ Division, attended also by the GOC 56 (L) Division and his brigadiers. This decided that the second advance by 201 Guards Brigade and 6 Brigade should again be silent, but the artillery was to be ready to support the advance with concentrations and to bring down defensive fire later. The objectives for 6 Brigade were first Djebel Terhouna, including a spur running to the north, and then Djebel es Srafi, both to be taken by 26 Battalion, which alone was to advance. On the right 201 Guards Brigade would conform. The 25th Battalion was to move up to the rear of 26 Battalion to strengthen the defence facing north-west, for by the end of the

Djebel Terhouna and Djebel Es Srafi. Night Attacks on 23 and 24 April

operation the brigade line would run nearly north and south. The 24th Battalion would not move, but the ‘hinge’ of the line just east of Djebel Bir was strengthened by several anti-tank guns, including two 17-pounders.

A final decision about artillery support was to be made at 6 p.m., but the divisional intelligence summary issued at that hour caused some concern as it stated that the enemy was in occupation of part of the objective, in particular the west end of Djebel es Srafi. There was further consultation between brigade and divisional headquarters, and a decision was not reached until 9 p.m. This was to adhere to the silent attack, as the case was held to be not proven, but events proved that the summary was substantially correct.

At 10 p.m. 26 Battalion, with B Company (Major L. G. Smith4) on the right, and A Company (Captain F. M. Ollivier) on the left, moved off to their objectives, Terhouna and Srafi respectively. B Company almost reached Terhouna but then met shell and mortar fire, and two platoons were held up. The company commander called for an artillery concentration at 3 a.m., and this was fired fifteen minutes later; but the enemy’s fire intensified, and Major Smith was mortally wounded. The CSM, Warrant Officer Lock ,5 sited the two platoons, helped in the evacuation of the wounded, and then guided up the supporting arms, which were all in position on Terhouna before dawn. The enemy made no attempt to counterattack, but kept the feature under heavy fire.

A Company met strong opposition on Srafi. During its approach heavy fire came from the feature itself, and as the ground was broken and the going difficult little progress was made, and the company went to ground on the southern slopes. Captain Ollivier went back to report to Lieutenant-Colonel Fountaine, who decided that another attempt must be made, and arranged for C Company (Captain J. J. D. Sinclair) to assist. C Company was directed to the east end of Srafi and A to the west. Arrangements were made for the artillery to fire concentrations on Point 141, a feature just beyond Srafi, and for the battalion mortars joined by others from 24 Battalion to bombard Srafi and then Point 141.

At 3.30 a.m. the mortars fired from behind Djebel el Hamaid, and as soon as they had switched to Point 141 C Company advanced from south-east of Srafi. The fighting was severe, as the enemy troops – all Italian from Young Fascist Division – were well dug-in and well armed, and their pits had to be cleared out by hand grenades and bayonets. While the rest of the company was fighting

on Srafi, 13 Platoon (Lieutenant Thomas6) went on to attack Point 141 and even induced the enemy to surrender, but by that time was reduced to the OC and three other ranks. The prisoners managed to regain their positions, and the opposition was too strong for the small party, which had to withdraw to Srafi, and even here the company had in the end to be content with digging in on the southern slopes. It was now only 27 strong.

A Company’s experience on the western end of Srafi was much the same, and the fighting soon became a series of section and individual actions among a maze of occupied trenches. Bit by bit the company, now only between twenty-five and thirty strong, became lodged on the western end and was in touch with C Company, but as it had not been possible to clear Point 141, it had to keep below the crest.

At daylight on 25 April (Anzac Day) an enemy attempt to clear Srafi was defeated, but he continued to hold weapon pits on the highest point, and our companies could not advance farther. There was persistent sniping, mortaring and shelling, and movement from the trenches was impossible. But no further attack developed and the companies retained their somewhat uneasy gains.

B Company on Terhouna was likewise pinned to its trenches during daylight, but made contact between all three platoons and was reasonably secure. It was in touch with neither 201 Guards Brigade on Hamadet es Sourrah nor with C Company on Srafi, although the gaps were covered by fire.

Headquarters 6 Brigade had made arrangements for a further attack on Srafi should 26 Battalion not succeed, and for this purpose moved A Company of 25 Battalion (now on Hamaid en Nakrla) to a point near Headquarters 26 Battalion behind Djebel dar Djaje, intending that it should be used as part of a force for which 3 Royal Tanks was to provide armour. When at 5.40 a.m. it was reported that Srafi had been captured, this plan was cancelled, but when a little later 26 Battalion reported that its companies had reached only the southern slopes, 3 Royal Tanks was instructed to move up to occupy the feature. Unfortunately the plan to incorporate infantry was not revived. Tanks from B Squadron, 3 Royal Tanks, swept over the top of Srafi at 9 a.m. and destroyed some guns, then withdrew to the foot of the hill owing to shelling. Again at 1 p.m. they moved over the top, this time as far as Point 141, reporting that they thought infantry could get there if the tanks removed themselves to avoid drawing fire. But while part of C Company succeeded in clearing the eastern end of Srafi and

consolidating there, no infantry was available to follow up the tank attack, and the tanks promptly called for infantry support. However, the companies on Srafi were too weak to do any more, and the tank attack remained a rather disjointed operation. Enemy infantry, which seems to have remained in concealment during the armoured sweeps, was not permanently dislodged. At 2.15 p.m. Fountaine reported that he could hold Srafi but could not both capture and hold Point 141.

Evacuation of the wounded from Srafi was a continuing problem. Walking wounded as usual made their own way back, but one of the tragic hazards of war occurred when some of these, still with their arms, appeared from the enemy side of Point 114, held by 24 Battalion. They were fired on, and one was killed and two wounded again before their identity was established. The casualties in 26 Battalion up to the end of 25 April were six killed and twenty-seven wounded, with six missing.

For 24 Battalion the day was one of constant shelling and restricted movement. At one stage, seeing enemy troops on Srafi, the OC B Company, Major Andrews, took forward two carriers with heavy machine guns and opened fire from about 1400 yards. The enemy troops scattered, but 88-millimetre guns soon opened up on the carriers, which were obviously under direct observation, and they had to withdraw.

On Djebel Terhouna and Djebel es Srafi enemy fire died down towards evening, and after dusk meals were taken up to the forward companies. B Company extended its line to the east and made junction with 201 Guards Brigade, and our artillery fired three heavy concentrations on Point 141 during the night to discourage any idea the enemy might have of counter-attacking. The situation, however, had steadied down into uneasy stalemate.

The opposing enemy comprised Young Fascists interspersed with men from 90 Light. There was also a report of tanks some distance back but it was a doubtful one. It is unlikely that there were any German tanks hereabouts at this time, as 15 Panzer Division was already away in the north.

That the enemy had accepted the position was shown on 26 April, when his shelling greatly decreased and our troops had a comparatively quiet day. It was their last action for a while, as 25 and 26 Battalions were relieved that night by 169 Infantry Brigade of 56 (L) Division, and 24 Battalion by 152 Infantry Brigade of 51 (H) Division, the boundaries between these two divisions being adjusted accordingly. Despite a little harassing fire the relief was complete by 2.30 a.m. on 27 April, without incident.

The 4th Indian Division was withdrawn from the line at much the same time, and Eighth Army’s front was held by 56 (L) Division on the right from the coast to Djebel dar Djaje: 51 (H) Division in the centre as far as the western side of Djebel Garci: and 7 Armoured Division on the west flank, soon to be replaced by 4 Light Armoured Brigade and ‘L’ Force. The French 19 Corps, one division of which was under Eighth Army, was on the left.

The New Zealand Division, including 8 Armoured Brigade, but less the artillery and engineers, concentrated in a rest area a few miles west and north-west of Sidi bou Ali. The duties of the artillery and engineers will be described later.

The General Situation up to 26 April

It will be remembered that the attack by First Army and 2 US Corps was to commence on 22 April. The enemy knew or deduced enough of the Allied intentions to stage one last spoiling attack, and ‘beat First Army to the draw’ by attacking near Medjez el Bab on the night 20–21 April – the evening that ORATION started. But while there was some slight dislocation, the results of the enemy attack were not great, and the First Army offensive was only slightly delayed.

The Allied attack was in three thrusts – 9 British Corps (1 Armoured, 6 Armoured and 46 Infantry Divisions) round the Sebkret el Kourzia salt marshes directed on Tunis: 5 British Corps (1, 4, and 78 Infantry Divisions) astride the Medjerda River east of Medjez: and 2 US Corps (1 and 9 US Divisions) between Beja and Sedjenane directed on Mateur.

All three thrusts were strongly opposed. South of the Medjerda River 9 and 5 Corps were ultimately opposed by the three panzer divisions – 10, 15 and 21 – in addition to German infantry.

In four days’ severe fighting, 9 Corps, employing its three divisions, had advanced to an area north-east of the marshes, but here the enemy stabilised his front for the time being. Fifth Corps attacked with 1 and 4 British Divisions south of the Medjerda and 78 Division to the north. On the south they reached a point just short of Djebel bou Aoukaz, and on the north bank cleared Djebel Ahmera, which as ‘Longstop Hill’ had been a thorn in the flesh since the early days of the campaign.7 But here again the enemy managed to establish a defensive line, and still showed good fighting spirit. The United States Corps had heavy fighting in mountainous country, and had in the end also to employ 34 and 1 US Armoured Divisions, but was gradually working its way towards Mateur.

Thus none of the thrusts effected a breakthrough, but the enemy was becoming badly stretched, and it was probable that another heavy blow would be decisive. A pause was necessary, however, and on 26 April First Army was ordered to check the offensive. Eighteenth Army Group then began the preparation of its final plan, which was to concentrate for a continued offensive. This would include moving 1 and 6 Armoured Divisions from 9 Corps to 5 Corps in the Medjerda valley, where the main effort would be made. Eighth Army would continue its pressure towards Hammamet, to prevent any more forces moving across to oppose First Army. By this time, however, the last available enemy formation ( 15 Panzer Division) had gone, and the most that could now be achieved would be to keep the enemy occupied all along the front and never relax the strain on his Higher Command. The enemy had the advantage of working on short interior lines of communication and did, in fact, early in May, move a battalion from 90 Light Division to 5 Panzer Army.

Eighth Army Plans

The push towards Hammamet was now to be effected in a series of operations, of which the readjustment of the Army line completed on 26–27 April was a preliminary. These operations never got beyond the early stages, and as 2 NZ Division prepared no orders and took no part in those activities which did take place, it is unnecessary to give full details, but the stages were to be as follows:

Night 26–27 April: 2 NZ Division to be relieved by 56 (L) and 51 (H) Divisions.

Night 28–29 April: 56 (L) Division to complete the capture of Point 130 (on Terhouna) and to capture Point 141. About this time 4 Indian Division was to move north of Enfidaville.

Night 29–30 April: 56 (L) Division on the right and 4 Indian Division on the left to capture a line running from the coast to Djebel et Tebaga (Operation CHOLERA).8

Night 30 April–1 May: 56 (L) Division to relieve 4 Indian Division and take over the whole operational front; 7 Armoured and 2 NZ Divisions to concentrate for the final phase.

Night 1–2 May: 4 Indian Division to capture Djebel Chabet el Akam; 2 NZ Division to break through between this point and Sebkra Sidi Kralifa; 7 Armoured Division to pass through the gap and exploit towards Hammamet. Very heavy air support was to be available.

This culminating operation was known as ACCOMPLISH, which name was sometimes applied to the whole group of operations.

The plans for this series of operations had been in the process of formulation since it became clear that ORATION would not succeed. Unlike ORATION, however, they did not have the support of the generals who were to carry them out. General Horrocks has since written, ‘I always look back on the time when we were planning this operation as probably the most difficult period of the war. I disliked the battle and realised that casualties would be high. Generals Freiburg [sic] and Tewker [sic] also hated it, and I have always felt that it was extremely public-spirited of the former to undertake the main role in this operation. I know that he was under fire as regards New Zealand casualties,9 and these might have been considerable. When Field Marshal Montgomery returned from Cairo (where he had been examining the plan for the invasion of Sicily) I pointed out the difficulties of the forthcoming battle. I said “we will break through but I doubt whether at the end there will be very much left of the 8th Army”.’10

Horrocks also felt certain that Montgomery did not like the operation. Yet Montgomery insisted that ‘the big issues are so vital that we have got to force this through here.’11 But Horrocks believed that the operation was ‘contingent on success in the North’,12 in which case a success by First Army would render redundant a costly victory by Eighth Army. Moreover, when the operation failed, Alexander was able to write in his despatch that this made no difference to the plans that he was making for the final offensive, and, indeed, it was 28 April, the eve of the operation, when Montgomery informed Alexander that it was his intention ‘to establish three divisions and later four divisions in area Hammamet – Bou Ficha –Marie du Zit and then to operate as situation demands.’13 Thus it seems inescapable to conclude that Montgomery was still anxious to employ Eighth Army in a role which resources and terrain combined to render impracticable, and which was not in itself essential to the Army Group plan.

That Montgomery was determined that Eighth Army should fight its way through the bottleneck north of Enfidaville, in spite of the objections of his generals, and at the same time give Horrocks the impression that he was not happy about the proposed operation,

may well reflect lack of confidence that First Army would be able to achieve decisive results in time to maintain the timetable for the invasion of Sicily. Or it may indicate the continued existence of the earlier divergence in the tactical appreciations of Alexander and Montgomery. Yet this ignores the fact that Alexander included in his Army Group directive the instruction that Eighth Army should advance to Tunis via Hammamet, either on his own or on Montgomery’s initiative. A further complication is that Horrocks has recorded the statement that after ORATION Montgomery considered that the best policy would be for Eighth Army to further reinforce First Army, but that this was impossible for administrative reasons.14 In this maze of contradictions the historian might be pardoned if he overlooked the more simple possibility that, although it was probable that a degree of misunderstanding existed between Alexander and Montgomery, the Eighth Army, personified by its commander, did not, after its long and victorious march from Alamein, have any intention of stopping until victory was in its grasp.

For Freyberg this difficult planning period was complicated by his dual responsibilities: to the Army for the operation and to the New Zealand Government for the wise use of the Division. When his objections were met by the repeated assurance that the operation was vital to the Army Group plan, he finally, on 27 April, agreed. As it is not now possible to regard the operation in this light, it is a case for reflection whether the plight of a general officer with Freyberg ‘s high sense of duty, and dual responsibility, could have been avoided.

However, during the week of planning Freyberg carefully explored the tactical implications of the task ahead, and as early as 22 April exhorted his senior officers not to get depressed. He told them the story of the Turk who accepted a large sum of money from the Sultan as a fee for teaching a donkey to talk. The Grand Vizier said to him, ‘You are a rash young man. You know what will happen to you if you fail?’ The young man replied: ‘It will take three years, and a lot may happen in that time. The Sultan may be dead: I may be dead: or the donkey may be dead!’ Although it must have seemed to Freyberg during the period between the 22nd, when he related it, and the 27th, when he finally gave his decision, that the donkey was not going to die, the wisdom of this fable was soon to be proved.

On the night 28–29 April 56 (L) Division duly captured Points 130 and 141, but the enemy recaptured Point 141 in the morning of the 29th. In the ensuing alarm, 2 NZ Divisional Artillery, which

had deployed north of Enfidaville, found it advisable to post all available light machine guns and riflemen round the gun positions, in order to deal with any enemy penetration. Although none occurred, the stand-down was not given for twenty-four hours. At 4.45 p.m. on 29 April, 2 NZ Division was advised by 10 Corps that the operation set down for the coming night would not take place, and at 6 p.m. that all future operations had been postponed. Later in the evening Horrocks phoned Freyberg to say that all plans were to be recast, and that future moves would be known by midday on 30 April.

It transpired that after the check to 56 (L) Division Montgomery had advised Alexander that the division had little fighting value at the moment,15 and that in any case he was not at all happy about the ‘present plan for finishing off this business’. He asked if Alexander could come and see him on 30 April.

Change of Plan

On 29 April Eighteenth Army Group had in fact issued another directive to First Army for the continuation of the offensive, which was to be pursued with the formations already under command, but this was held back when Montgomery’s message was received, and after the discussion on 30 April it was cancelled.

At this meeting Montgomery repeated that he could now see no good purpose in going on with his offensive up the coast, and the whole tactical position was discussed. The first decision was that Eighth Army was to adopt a purely holding role. The next, the earlier ‘administrative difficulties’ evidently overcome, was that the best formations that could be spared from Eighth Army were to be moved across at once to First Army. It is clear that while General Alexander had been quite prepared to plan the First Army attack with its existing strength, he was more than willing to accept the transfer of troops now that Montgomery was willing to give them up. He was in any case becoming anxious about further delays, as in the background was the invasion of Sicily, which would take some time to prepare.

The speed with which the new plan was made is indicated by the fact that, although Alexander did not arrive at Headquarters Eighth Army until 7.30 a.m., the orders for 4 Indian Division and other formations to move were sent out at 9 a.m., only an hour and a half later.

The prospects for First Army now changed from a continuation of a slogging match to the delivery of a smashing blow. The new plan put overwhelming strength at the decisive point, and made full use of the power of the Allied forces. Perhaps the decision to transfer troops was a little belated.

Montgomery selected 7 Armoured Division, 4 Indian Division, and 201 Guards Brigade for transfer and there was a very good reason for the choice of these formations. They were the nucleus of the original Western Desert Force of 1940, from which Eighth Army had evolved. (The 201st Guards Brigade was at that time numbered 22.) The 7th Armoured Division and 4 Indian Division had taken part in the first offensive at Sidi Barrani in December 1940, and it was fitting that they should take part in the final victory. To quote from General Alexander’s despatch:

The Enfidaville line thus marked the culmination of Eighth Army’s great advance across Africa . ...In six months they had advanced eighteen hundred miles and fought numerous battles in which they were always successful. This would be an astonishing rate of progress even in a civilised country with all the modern facilities of transport – the equivalent of an advance from London to two hundred miles east of Moscow – but in a desert it was even more remarkable.

In the First Army the commander of 9 Corps had been accidentally wounded, and Lieutenant-General Horrocks was sent from 10 Corps to take over 9 Corps, which was to be the spearhead of the final attack. Lieutenant-General Freyberg was then appointed to take temporary command of 10 Corps.

The task of Eighth Army now became a holding one on the existing line and to maintain pressure by limited attacks with the forces available. These were now 2 NZ, 51 (H), 56 (L), and 1 Free French Divisions, and 4 Light Armoured and 8 Armoured Brigades. Montgomery decided to hold the line with 56 (L) and 1 Free French Divisions, to keep 51 (H) in reserve where it could begin training for Sicily, and to move 2 NZ Division and 8 Armoured Brigade to the western flank for an operation against Saouaf – an operation which was designed to assist the French formations, due to attack on 3 May. All these formations, except 51 (H) Division in Army Reserve, formed part of 10 Corps.

Lieutenant-General Freyberg took over the Corps at 4 p.m. on 30 April, and at the same time Brigadier Kippenberger took command of 2 NZ Division, Lieutenant-Colonel R. W. Harding took over 5 Infantry Brigade and Major M. C. Fairbrother went to command 21 Battalion.

During these last few days the Hon. F. Jones, New Zealand Minister of Defence, visited the Division. He arrived at Headquarters on 27 April and remained until 1 May, visiting many of the units not in the line. He also had discussions with Lieutenant-General Freyberg regarding the General’s future, and on proposals for a furlough scheme for long-service personnel.

2 NZ Division from 27 April to 3 May

It has already been recorded that 2 NZ Divisional Artillery and Engineers remained in the forward area when the infantry was withdrawn on 26 April, for it was intended that they should support the attack on 29–30 April and subsequently. Relief was given to one-third of a regiment at a time, the guns remaining in position but the men going back for a rest. On the night 27–28 April, after due reconnaissance and survey work, all three New Zealand regiments and 111 Field Regiment, RA, moved through Enfidaville and, despite the brief time before daylight and what the CRA called the ‘tightness’ of the deployment, were in position north of the town by first light on the 28th.

There was little activity on 28 and 29 April, and as the attack set down for the night 29–30 April did not eventuate, they were mostly left to their own devices for a few days. In fact the CRA has since said, ‘I was always puzzled whose orders we were under during this stage. I don’t remember getting any orders from anybody, so mostly made up our own.’16

The CRA conducted one or two exercises on barrages on 1 May. Unfortunately the second exercise created some ‘alarm and despondency’ in 56 (London) Division, as the enemy reacted very quickly with defensive fire, which covered an advanced observation post occupied at the time by the GOC 56 Division and some of his staff, who were spectators of Weir’s target.

After dark on 1 May, 4 and 5 NZ Regiments and 111 Regiment, RA, were withdrawn for rest, but 6 Field Regiment remained in position under command of 56 (L) Division, this role lasting until 10 May.

Between 25 and 29 April the Divisional Engineers worked steadily on the construction of tracks from the south of Wadi el Boul to the Zaghouan road west of Enfidaville, to make easier the approach marches of the troops destined for ACCOMPLISH, Like so much work at this time, it was in the end to no purpose.

Meanwhile the infantry brigades were having a well-earned rest, including visits to the beach. On 3 May Brigadier Harding moved 5 Brigade farther back to a new area south-west of Sidi bou Ali.

Units had only just arrived there when orders came that 5 Brigade was to prepare for an operational role in the Djebibina area, where the Division would be moving on 4 May.

The Last Plan

The move of 2 NZ Division to the left flank of 10 Corps was a minor one in the last stage of the offensive in Tunisia. By 3 May Eighteenth Army Group’s final plan was ready, and the directive reads:

INTENTION

1. The Allied Forces of 18 Army Group will take the offensive to destroy or capture the enemy forces remaining in Tunisia.

METHOD

2. First Army will attack and capture Tunis. Eighth Army and 2 US Corps will co-operate by exercising the maximum pressure in order to prevent the enemy transferring troops to oppose the attack of First Army.

3. [Details of grouping]

4. After the capture of Tunis, First Army will, in order of priority: –

( a) Exploit rapidly eastwards and south-east from the Tunis area to prevent the enemy establishing himself in the Cap Bon Peninsula.

Eighth Army will co-operate in this phase by pressing forward to the Hammamet area from the south.

( b) Co-operate with 2 US Corps by an advance from the south to capture Bizerta.

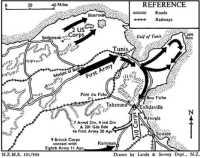

General Alexander’s fresh plan was to strike an overwhelming blow along the direct road from Medjez el Bab to Tunis on 6 May. This would be done by 9 Corps under Lieutenant-General Horrocks, with four divisions under command. Two divisions, 4 British and 4 Indian, on a front of only 3000 yards, were to breach the enemy defences, and 6 and 7 Armoured Divisions were to breack out through the gap, directed on Tunis. The 1st Armoured Division was held in First Army reserve to reinforce this attack if required.

The plan for 9 Corps was much influenced by that for SUPERCHARGE on 26 March, in that it was to be on a narrow front preceded by an all-out air blitz. Horrocks put into good effect the experience gained from the earlier battle.

After the capture of Tunis, 7 Armoured Division was to turn northwards towards Bizerta, and 6 Armoured Division was to advance east and south across the base of the Cape Bon peninsula towards Hammamet, driving the enemy up against Eighth Army and preventing a last stand in the tip of the peninsula. The Royal Navy was waiting gleefully to deal with any forces attempting to escape by sea.

Fifth British Corps was to pave the way on 5 May by capturing Djebel bou Aoukaz, south of the Medjerda, to remove the threat to the left flank of 9 Corps. Second US Corps had been maintaining pressure throughout, and was to continue towards Bizerta and form the northern jaw of the pincers of which 7 Armoured Division would form the southern.

Army Group Headquarters stressed that Eighth Army was to do all it could to prevent the transfer of enemy troops from the south to the west face, and even before the issue of his directive Alexander asked Montgomery for an outline of local operations and deceptions that could reasonably be carried out. He was anxious that among these there should be some action to hearten 19 French Corps, whose task it was to attack Djebel Zaghouan on 3 May and so open the Pont du Fahs defile. Montgomery replied on 1 May that he would carry out local operations south of Saouaf on the early morning of 4 May, and would increase the pressure on 5 and 6 May. He would begin at once a system of artillery concentrations on known enemy areas and sensitive points, together with active patrolling.

The task of assisting the French became that of 2 NZ Division, which was to mount local attacks south of Saouaf to support the French flank, prevent the enemy from reinforcing his front opposite the French, and stand in readiness to advance should 19 French Corps be successful.

The possibility of this role had been known since 1 May, and the commander of 10 Corps (Lieutenant-General Freyberg) had examined the area with the commander of 4 Light Armoured Brigade, who was responsible for the sector. For a brief time it was intended to use 8 Armoured Brigade for exploitation, but the final plan was for the Division to use only its two infantry brigades supported by 5 Army Group Royal Artillery, consisting of three field regiments and one medium regiment, one light anti-aircraft and one heavy anti-aircraft battery, in addition to 4 and 5 NZ Field Regiments.

Initially the Division would advance north-east through the line occupied by 4 Light Armoured Brigade, and establish itself in the hills parallel to but some 2500 yards short of the road from Enfidaville to Saouaf, but no major operation was to be carried out, and the advance was to be a mixture of penetration during darkness and exploitation by patrolling. The boundaries with 51 (H) Division on the right and 19 French Corps on the left gave a frontage of about five miles.

On 3 May the French duly attacked Djebel Zaghouan and penetrated to a depth of four miles.

The Division moved by road to its new sector on 4 and 5 May in its usual groups. Divisional Cavalry made the first reconnaissance on 4 May, ready to take over the patrol line from 4 Light Armoured Brigade early next morning, followed by 5 Brigade Group. When the leading unit, 21 Battalion, reached Djebibina it was bombed by machines of the USAAF, and one other rank was killed and other damage done. The column was delayed for fifteen minutes, but by 9.50 a.m. the group was dispersed without further incident. The 7th Field Company went to work at once clearing mines, which were thickly sown in the proposed field of operations.

Divisional Headquarters and the artillery, less 6 Field Regiment, moved without incident. The units of 5 AGRA were already in position in the area. The 5th Field Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Glasgow) commenced deployment during the afternoon, but the first battery in action was heavily shelled and was later found to be almost in the very thinly manned FDLs. One battery of 4 Field Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Philp17) was detached to support the French division on the left and was soon in action. The enemy 170-millimetre gun was also used in this area against the crossroads at Pont du Fahs. It ended its active service on this duty.

On 5 May 6 Brigade Group moved and dispersed near Djebibina. It remained in reserve during the operations which followed. Many administrative units did not move at all.

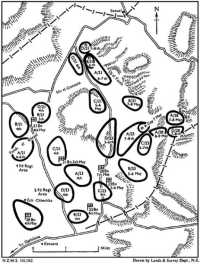

Operations Around Djebibina

Between 4 and 9 May the total casualties in 2 NZ Division were some fifteen killed and thirty-six wounded. All the operations in this period were of a minor nature as the policy was that no major operation would be carried out, but that some degree of penetration would be effected whenever possible during darkness. Successes obtained in such a way were to be exploited on subsequent nights by vigorous patrolling. General Freyberg did not expect any notable results, and believed that the more the enemy was stretched in this area, the more firmly he would hold the coastal sector.

Not a great deal was known of the enemy troops nor of their exact position on the ground, but the main line appeared to be immediately to the north of the road running through Saouaf, with advanced posts farther south. The whole area was heavily mined.

5 Brigade operations north-east of Djebibina, 4–8 May

While there seem to have been elements of regiments from other divisions, it is sufficiently accurate to say that opposite 2 NZ Division there was now the unarmoured portion of 21 Panzer Division, and a mixture of 164 Light Division and Pistoia (or Superga) Divisions.

On 4 May the French attack against Djebel Zaghouan went no farther, and 19 French Corps merely consolidated its gains.

That night 23 Battalion, on the right, and 21 on the left advanced silently and settled down by 10 p.m. without incident about four miles north-east of Djebibina on a front of five to six thousand yards. Thick minefields were discovered, indicating that the enemy’s main positions lay farther ahead. The 28th Battalion remained in reserve.

Divisional Cavalry reconnoitred forward for about another 2000 yards on 5 May, drew fire, but was held up by mines. Patrols sent out by the battalions brought back the same tale, but it appeared that the line could still go forward without difficulty, and Major-General Kippenberger gave instructions accordingly for a further advance of from 1500 to 3000 yards.

At 3.30 p.m. eight enemy aircraft dropped a few bombs in a hit-and-run raid over the artillery area, but caused no damage. As far as is known, this was the last raid by the Luftwaffe against 2 NZ Division in North Africa.

The two battalions duly went forward after dark, again without artillery support. The forward platoon on the left came in touch with enemy troops and exchanged fire, but as instructions were to avoid close action, the platoon withdrew. The line of 21 Battalion was advanced under cover of fog on 6 May, by which time the FDLs faced nearly due east.

During the night 5–6 May our artillery fired concentrations at targets on the front of 19 French Corps and later received thanks from the divisional commander, although the French had not been able to achieve decisive results.

Sappers of 7 Field Company were kept hard at work clearing mines, which were considered to be more thickly sown than ever before in the experience of the Division. But while the minefields caused much delay, they caused little damage, for the enemy no longer covered them by observation or fire, and they could be cleared at leisure.

The activities of the next few days were much the same as previously, to push forward as far as possible without becoming involved in a major operation. The Division had ample artillery support, and engendered great excitement in senior officers of 19 Corps by offering the support of up to 200 guns, but despite some French exuberance there was no sign that the support would be wanted. On 6 May General Freyberg directed that the operations should aim at pinching out Djebel Garci, which still loomed unconquered on the right front. But it was soon discovered that limited operations were insufficient to capture the feature.

The End in Tunisia, April–May 1943

On the night 6–7 May 23 and 21 Battalions advanced another 1000 yards or so. There were a few minor clashes, and a handful of prisoners were taken. The limit of ‘peaceful penetration’ had almost been reached.

Meanwhile, away to the north the last battle had started. Fifth Corps captured Djebel bou Aoukaz by nightfall on 5 May, enabling 9 Corps to form up. At 3.30 a.m. on 6 May, 4 British and 4 Indian Divisions moved forward, and aided by massed artillery and by the greatest air effort in the war up to that time – over 2000 sorties – made a gap by midday. The armour and armoured cars of 6 and 7 Armoured Divisions then passed through and by nightfall were halfway to Tunis. On the American front resistance showed signs of crumbling also, and the advance was fast.

On 7 May, 6 and 7 Armoured Divisions moved forward at first light, stormed down the road to Tunis, and at 2.45 p.m. entered the town. At 4.15 p.m. American troops entered Bizerta. The first stage had been a brilliant success, and it now remained to round up the enemy troops and prevent any last-ditch stand.

The same day the French also occupied Pont du Fahs, which had long been an objective.

It is small wonder that when these stirring events came to the ears of 2 NZ Division there was a feeling of disappointment that it had not shared them. But in the meantime, like good soldiers, they had to carry on with more mundane tasks. By the evening of 8 May the divisional FDLs ran parallel to the Saouaf road and some 2500 yards short of it, a total advance since 4 May of some 6000 yards. The 21st Battalion was on the left throughout, but latterly 28 Battalion had in effect passed through 23 Battalion, and was now in a rather exposed position and having some casualties from shell and mortar fire. The various posts were scattered and were not linked up on the ground, showing the effects of the policy of penetration where possible, as opposed to a set-piece advance.

In the north on 8 May, 6 and 7 Armoured Divisions fanned out as intended. The 7th Armoured Division was fast closing its half of the net towards Bizerta, and had almost met 1 US Armoured Division coming south from that port. The 6th Armoured Division came up against the defile between the hills and the sea at Hammam Lif, ten miles east of Tunis. It was closely supported by 1 Armoured Division and 4 British Division, but had run into strong defences, well supplied with 88-millimetre guns, and was there temporarily held up.

General Freyberg now decided so to dispose 10 Corps that, in accordance with the plan for Eighth Army, it could advance quickly up the coast towards Hammamet. It was arranged therefore that 56 (L) Division would attack during the night 8–9 May, and 5 AGRA was to leave 2 NZ Division during 8 May and move across to provide additional support. Moreover, 2 NZ Division less 5 Infantry Brigade Group was also to move to Enfidaville in the early hours of darkness on 8 May, leaving 5 Brigade to continue exerting pressure to turn Djebel Garci. But later in the day instructions were received that present positions were to be consolidated, and that on the night 9–10 May the area was to be handed back to 4 Light Armoured Brigade. Fifth Infantry Brigade Group would then rejoin the Division. When this relief was complete the 10 Corps line from east to west would be held by 56 (L) Division, 1 Free French Division (which had relieved 51 (H) Division), ‘L’ Force, and 4 Light Armoured Brigade.

Instructions in 5 Brigade for the night 8–9 May were that there would be no patrolling, and that a passive attitude was to be maintained. But the enemy suddenly became aggressive, worked round one company of 28 Battalion and showed every sign of surrounding it. So dangerous did the position become that the company commander – wisely in the circumstances – withdrew. It

seemed that the point had been reached when the enemy had decided that something must be done to stop the infiltration of his line. It may have also been a last attempt to keep up morale.

However, activity died down and a patrol from 28 Battalion made things even by rounding up twenty-five prisoners and some machine guns during daylight on 9 May. The relief of 5 Brigade took place without incident that night, and on the morning of 10 May the group moved back to the Enfidaville area.

The Campaign Ends

While 2 NZ Division was still at Djebibina or being relieved there, other formations in 10 Corps were carrying out the operations decided upon by General Freyberg to advance towards Hammamet. On the night 8–9 May 56 (L) Division attacked and reached a line five miles north of Enfidaville. It was intended that on the next night it should advance to Djebel bou Rhabrouba, two miles farther on, and that on the same night 6 Brigade of 2 NZ Division should relieve 169 Brigade, its left-hand brigade. Then on the night 10–11 May 56 (L) Division would capture Djebel Chabet, yet another mile north, and 2 NZ Division was to be prepared for exploitation to Hammamet.

The 25th Battalion therefore relieved 169 Brigade, and shortly after midnight on 9–10 May was in position on a line from Djebel Hamadet es Sourrah to Djebel Ogla, with three companies forward and one in reserve.

The attack by 56 (L) Division on this night was supported by 5 AGRA, 111 Field Regiment, RA, and 4 and 6 Field Regiments, NZA. It did not succeed, mainly owing to enemy fire from Djebel et Tebaga and Kef Ateya, and the troops returned to their starting positions. This was the last attempt by 10 Corps to advance. Active patrolling was prescribed for the future, combined with a free use of the large artillery resources.

Meanwhile, farther north, 6 Armoured Division, after being held up for forty-eight hours at Hammam Lif, on that very morning of 10 May at last broke through and careered down the road towards Hammamet. The noose had already closed between Tunis and Bizerta, and what was left of three enemy divisions – including 15 Panzer Division and the armour of 21 Panzer – had been captured, together with von Vaerst, the commander of 5 Panzer Army. The task remained of gathering in what was left, now fast being compressed between First and Eighth Armies. The Navy was ready with a plan to deal with any attempted evacuation by sea, the ‘Intention’ paragraph reading: ‘All Axis forces crossing the Sicilian Narrows will be drowned’.18

By nightfall on 10 May, 6 Armoured Division reached Hammamet, and advancing south on its right (i.e., west) were three other British and Indian divisions, directed along the roads from Tunis to Zaghouan and Ste Marie du Zit. The ring round the remaining Axis forces was complete.

On 10 May activity on 10 Corps ‘ front was almost entirely confined to artillery fire from both sides. It was a quiet day, with a quietness that was strange when contrasted with the violent activity not many miles away. In the afternoon Lieutenant-General Freyberg sent a message to Major-General Graf von Sponeck of 90 Light Division, by a German prisoner under a white flag, inviting him to surrender, but at the end of the day there was no response.

During the night patrols from 25 Battalion found that enemy troops were still on Djebel Mengoub, and even on Point 141, the scene of earlier operations.

At 6 a.m. on 11 May, 1 Free French Division attacked northwards from Takrouna, capturing Djebel el Froukr and exploiting north-west. By evening a platoon from the reserve company of 25 Battalion made junction with the French between Djebel el Hamaid and Djebel Froukr. This move was the last alteration of 2 NZ Division’s operational dispositions in North Africa.

The Free French division captured some 300 prisoners, mostly German from 164 Light Division. On the rest of the front there were vigorous exchanges between the opposing artillery. Enemy fire was very fierce, and guns and mortars sprayed the countryside in a way suggesting that the enemy was getting rid of his stocks of ammunition. Kippenberger says that ‘shells pitched at random in a most disconcerting fashion’. Tenth Corps’ artillery replied with the biggest counter-battery programme yet fired in the campaign, thirtyone hostile batteries being engaged in a four-hour period.

There were still occasional casualties in 25 Battalion and among the gunners, all very distressing at this stage of the campaign.

During the day further attempts were made to induce the enemy to surrender. At 9.30 a.m. all guns on Eighth Army front stopped firing while two officers, one from 56 (L) Division and one from 1 Free French Division, were sent out with messages asking for unconditional surrender. Again there was no clear reply, but there were fires and demolitions along the whole front, and indiscriminate artillery fire remained heavy.

On this day, 11 May, 4 British Division swept right round the Cape Bon peninsula, capturing many prisoners. At last light 6 Armoured Division was just to the north of Bou Ficha, close enough to 10 Corps for the artillery of 2 NZ Division to fire in

support of 6 Armoured Division at targets in the Ain Hallouf – Bou Ficha area. The 4th Indian Division reached Ste Marie du Zit, and was in the hills north of Zaghouan. The French Corps had some fighting during the day, but at the end all enemy troops opposing them, including parts of 21 Panzer Division, agreed to surrender next morning.

But there were still some last pockets of resistance, and of these the greatest was in the area west of Hammamet, north of Enfidaville and east of Zaghouan, the most difficult to penetrate. On this day it became known that the Young Fascist Division had been rechristened ‘Bersaglieri d’ Africa ‘, the reason given by some unkind commentator being that they were now neither young nor Fascist.

The night 11–12 May was quiet. Two patrols went out from 25 Battalion to Point 141 and Djebel et Tebaga and found the enemy still there. During the night General Messe made contact with Headquarters 56 (L) Division, but was told that he must get in touch with 10 Corps, and that in any case only unconditional surrender would be considered.

On 12 May the quiet continued until about 9 a.m., when enemy fire from artillery and mortars reached the same intensity as on the previous day, again with no set targets and no co-ordination. Our own artillery was vigorous in reply, and 4 Field Regiment records that over 7000 rounds were fired. Nebelwerfers were active, and a concentration on the headquarters of 111 Field Regiment, RA, killed the CO, Lieutenant-Colonel W. P. Hobbs, who had been associated with 2 NZ Division on many occasions.

Our own air forces had, needless to say, played a large part in the disorganisation of the enemy, and now helped to decide the issue locally, for at 3.30 p.m. three formations each of eighteen medium bombers attacked the coastal area and for some miles inland, as a prelude to the further advance of 6 Armoured Division to link up with 56 (L) Division. When 6 Armoured Division moved on after the bombing, white flags appeared on many positions, and advancing tanks were not fired on. After an attempt at getting terms, 90 Light Division finally surrendered unconditionally. By 8 p.m. the surrender of all troops between 6 Armoured and 56 (L) Divisions was complete. Graf von Sponeck of 90 Light Division surrendered initially to Major-General Keightley of 6 Armoured Division. Later Lieutenant-General Freyberg went forward through 56 (L) Division and met von Sponeck, who is believed to have repeated his words of surrender, for many members of 90 Light said that they were glad to surrender to their old foe, 2 NZ Division. Von Sponeck was interrogated by General Freyberg, but there were no other courtesies. When a little later this surrender became known

throughout the Division, only dimly, amidst the drama of the enemy’s collapse, did men realise that the chase of 90 Light ‘to the end of time’ was over.

Farther west 4 Indian Division captured General von Arnim, the Supreme Commander in Tunisia. He was taken to General Alexander’s headquarters, where, says Alexander, ‘he still seemed surprised by the suddenness of the disaster’.

There remained, however, the rest of 1 Italian Army under Messe, comprising the troops in pockets in the hills and including what was left of 164 Light, and Trieste and Young Fascist Divisions. This still held from north of Saouaf to north and north-west of 25 Battalion, and even showed signs of fight, but its activities were foiled by 10 Corps ‘ artillery fire. Up to darkness on 12 May there was no sign of surrender, and patrols found Point 141 still occupied.

But during the afternoon Messe had apparently been trying to get in touch with some British headquarters. The message was picked up by 2 NZ Divisional Signals, which soon established good communication with the enemy headquarters. At 8.30 p.m. Divisional Signals was instructed to transmit the following message:

Commander First Italian Army from Commander 10 Corps. Hostilities will not cease until all troops lay down their arms and surrender to the nearest Allied unit.

At 10.33 p.m. a reply was received:

From Italian First Army to 10 Corps Eighth Army. Reference your message our representatives have left to meet yours at 10 p.m. your time. We have nothing further to add.

In the early hours of 13 May there was still some confusion over representatives, and it appeared that Messe was hoping for terms. Finally, at 8.30 a.m. the Italian envoys arrived at Headquarters 10 Corps. General Freyberg refused to discuss any terms and sent them back with the message:

You will now issue orders to your troops as follows:

| 1. | To lay down their arms and surrender to the nearest Allied troops immediately. |

| 2. | To destroy no equipment. |

| 3. | To furnish plans of all known minefields in your areas to the nearest Allied unit. |

Hostilities will continue until you have complied with these orders. Compliance must be immediate and you will inform me by wireless and by messenger at what time your troops will surrender.

At the same time a wireless message was sent to Headquarters 1 Italian Army saying:

Your representatives with a British officer carrying instructions have left for your headquarters. I have ordered my troops to cease fire pending your acceptance of these terms by 1230 hours today.

At 11.45 a.m. 1 Italian Army surrendered. A wireless message from Messe said:

As my proposals for a truce to give time to my representatives to carry out their orders has not been accepted and your troops are still carrying out their attack in the Saouaf area and considering the fact that my representatives sent out at 9 p.m. yesterday to First British Army have not yet returned I have ordered my troops to lay down their arms.

It was signed ‘Field-Marshal Messe’, his promotion having just been announced over the Italian Radio.

Later Marshal Messe, accompanied by Major-General von Liebenstein of 164 Light Division, surrendered in person to General Freyberg at Headquarters 10 Corps. Messe’s last messages to the Comando Supremo in Rome read somewhat grandiloquently, but are not without dignity. He was in fact the last to surrender.

At 2.45 p.m. on 13 May General Alexander signalled to Mr Churchill:

Sir, it is my duty to report that the Tunisian campaign is over. All enemy resistance has ceased. We are masters of the North African shores.

The last word about the surrender may be left to a British narrator, who says, speaking of the 210,000 prisoners captured between 6 and 13 May, that they were ‘as pretty a baby as any G has passed to the A/Q staff in the campaign’.

2 NZ Division after the Surrender

Prisoners began to stream in from about 10 a.m. on 13 May, including many from 90 Light Division. The guns of 4 and 6 Field Regiments were in action until midday, but did not fire, and the war just faded away.

For 2 NZ Division the ‘fading away’ was perhaps somewhat more marked than with other formations. Since about 22 April it had become apparent that the Division would not be in at the kill, but was to operate in a minor way while others participated in the rapid and spectacular victory. Moreover, the majority of men in the Division were not even in action on the day of surrender, and knew little of what was happening from hour to hour. There was no exhilaration, no excitement, no cheering, and it can only be said that the campaign came to an end very quietly. No written cease-fire order was issued.

There was, of course, also the fact that the troops were tired – not just the tiredness of a few nights without sleep, but the gradual insidious tiredness that comes from weeks and months of movement and strain and fighting, sustained only with the urge to keep on with a job that had to be done. It is little wonder that when the

task was finished the reaction was equally great. After all, the Division had not been out of the theatre of war since arriving in the Western Desert from Syria towards the end of June 1942, ten months and more previously, and even if one were to disregard the several crises of those summer months of 1942, the mere length of time was enough to leave its mark.

So 13 May was something of an anti-climax, and the Division had to wait for two years before sharing in a final overwhelming victory.

Back to Egypt

It has already been recorded why the New Zealand Government could not give approval for the Division to take part in the invasion of Sicily, or at least could not give a decision within the time limits involved. First Army was now to take over from Eighth Army, and the formations of the latter were to move back, some to prepare for the Sicily operations. In the circumstances, there was no point in holding 2 NZ Division anywhere in the forward area. For some time it had been understood that when it did move, the Division would return to Egypt. Furthermore, concurrently with the recent operations, there had been discussions between the United Kingdom Government, the New Zealand Government, and 2 NZEF overseas about the commencement of a furlough scheme, sufficient agreement by the two governments being reached towards the end of the campaign. It was now the responsibility of 2 NZ Division to get back to its main base as soon as possible, in order that the furlough scheme might be implemented.19

Arrangements for the return journey had been under discussion since 11 May, and it suited all concerned that the Division should move promptly. As a first step 56 (L) Division relieved 6 Infantry Brigade by 3 p.m. on 13 May, and the whole Division assembled in areas south of Enfidaville, groupings being ended and units reverting to their parent corps.

At this point the association with 8 Armoured Brigade ended, to the regret of all. General Freyberg later sent units of the brigade a copy of his despatch to the New Zealand Government on the recent campaign, in which the services of the brigade were recognised.

On 14 May Lieutenant-General Horrocks returned to 10 Corps, Lieutenant-General Freyberg reassumed command of 2 NZ Division, Brigadier Kippenberger of 5 Brigade, and Lieutenant-Colonel Harding of 21 Battalion. Lieutenant-Colonel Fairbrother assumed command of 23 Battalion in place of Lieutenant-Colonel Connolly.20

There was a daily quota for leave to Tunis, the very small one of 200 all ranks, but it is certain that many more, one way or another, managed to visit the city. However, the journey to Egypt was to start on 15 and 16 May, so that there was little time for sightseeing. Large parties risked the mines and booby traps on Takrouna to visit that already historic feature, and others searched areas for as yet unburied bodies. Most formations had thanksgiving services, including one in which for the first time all units of Divisional Artillery paraded together from a common laager area. The NZASC staged a ‘donkey derby’ with the animals of the Mule Pack Company, so providing much enjoyment for some thousands of men. And everyone collected souvenirs from among the accumulations of enemy equipment, in direct proportion to the opportunities for concealment, for there were strict orders that all enemy equipment was to be handed in.

Some interest was found also in watching the thousands of healthy-looking German prisoners who came out of the hills to give themselves up. They had been well-fed and well-equipped up to the last, and given the chance could have resisted for many days and even weeks ahead. But the blitzkrieg had overcome its inventors.

There was no doubt in anyone’s mind about the most desirable destination in Egypt. In fact there was unanimity that somehow or other the Division must squeeze into Maadi Camp, and a squeeze it would be, for there were 12,800 extra personnel with their 3100 vehicles to be accommodated. To allow for this, most of the troops already in the camp – training depots and reinforcements – were moved out to Mena camp near the Pyramids.

For the move to Egypt the Division was divided into five serials, each with its due proportion of troop-carrying vehicles, maintenance units, medical units and provost. The serials were:

| 1. | NZASC less detachments with other serials. |

| 2. | HQ 2 NZ Division Divisional Signals Provost Company less detachments. |

| 3. | 5 Infantry Brigade NZ Engineers NZ Medical Corps less detachments. |

| 4. | 6 Infantry Brigade Divisional Cavalry 27 MG Battalion NZ Ordnance Corps NZ Electrical and Mechanical Engineers less detachments. |

| 5. | NZ Artillery. |

The serials were then grouped into flights, the first three constituting Flight ‘A’, and the last two Flight ‘B’. Tanks were handed in to a British tank reception depot. Bren carriers went back to Egypt on transporters or by sea under separate arrangements.

Flight ‘A’ left Enfidaville on 15 May, staged at Wadi Akarit and Ben Gardane, and arrived at Suani Ben Adem near Tripoli in the evening of 17 May. Flight ‘B’ followed one day later at each stage. Flights halted for a day at Suani, and then, still moving a day apart, staged at Misurata, Buerat, Nofilia, and Agedabia, and arrived at Benghazi on 23 and 24 May. Again after a day’s pause, flights continued on 25 and 26 May, staged at Lamluda, El Adem, Buq Buq, Mersa Matruh, El Daba, and Amiriya, and arrived in Maadi on 31 May and 1 June. Administration for the move had worked smoothly throughout, and there were no difficulties over replenishment. The age of the vehicles and the supply of tyres presented the only trouble, but the LADs worked hard and kept the vehicles moving. Only thirteen were evacuated, and only fourteen arrived on tow, out of a total of 3100.

The troops enjoyed the journey, for the stages were easy and the places they passed through had associations with the many movements of the Division in the past. Mobile cinemas and the Kiwi Concert Party provided entertainment at intervals. National Patriotic Fund parcels were distributed and beer was issued from time to time. And when they arrived in Maadi, units were told that up to 40 per cent of each unit at a time would be given the opportunity of a fortnight’s leave in Cairo or Alexandria.

But what was even more heartening was the news that a furlough scheme to New Zealand was to be put into effect at once. For a while at least the war was over, and the future shone bright.