Chapter 1: Italy and Her Invaders

The Strategic Prelude

(i)

The Mediterranean Theatre

‘YOU have marked out a great battlefield for the future’. So Ernest Renan addressed Ferdinand de Lesseps in bidding him welcome to the French Academy in 1885.1 It was in defence of the canal which de Lesseps had cut through the isthmus of Suez that British troops crossed the Egyptian frontier into Cyrenaica on 11 June 1940, the day of Italy’s entry into the Second World War. As the raiding Hussars drove their armoured cars across the perimeter wire they opened the longest campaign of the war. It was not to end until, nearly five years later, soldiers from New Zealand picketed the streets of Trieste and Americans bivouacked in the shadow of the Alps.

The war in the Mediterranean fell into three phases of unequal duration. First, for twenty-eight months, there was a struggle to survive, to protect the means to ultimate victory – the base area of Egypt and the Canal, behind it the oil wells of the Middle East, and eventually the southern supply route to Russia – and to prohibit the dreaded junction of the Axis Powers with their Japanese ally. Opened by the battle of El Alamein in late October 1942 and the Allied landings in French North Africa, the second phase had for its grand achievement the clearance of the inland seaway for the unhindered passage of friendly shipping. In less than ten months advances from El Alamein in the east and Casablanca in the west converged in a northward thrust that carried the Allied armies across the Mediterranean and through Sicily to the Straits of Messina. Yet, though the German tyrant’s folly in trying to save Tunisia yielded unexpected profits, the Mediterranean war was still in its main strategic aims a work of rehabilitation. The invasion of the Italian mainland in early September 1943 brought it to a final, openly offensive phase of about twenty months, from the surrender of Italy to the German collapse. The slow amputation of the Italian leg was for the Reich a grievous, if not mortal, letting of blood, and for the Allies one of the most toilsome campaigns of the war. It engaged 2 New Zealand Division for nearly a year and a half

in circumstances very dissimilar from those related in the earlier volumes of this series. For if this last phase resembled the first in its duration and the second in its triumphant issue, it was like neither in the severity of its climate and terrain, in the complexity of the problems it presented to the high command, and in the strategic hesitancy that brooded over its beginning and shadowed its course.

(ii)

The friendship of the British and Italian peoples had political roots as deep as the Risorgimento of the mid-nineteenth century and cultural roots much deeper; and of the songs about liberating Italy, which the realist Cavour complained were too numerous, not a few were written in English. An understanding that rested in large measure upon common respect for parliamentary forms of government was shaken after 1922 when Benito Mussolini grasped power in the Italian State, but an open breach was delayed until 1935. In that year the honourable rejection by the British public of the Hoare-Laval plan for awarding Fascist Italy a portion of Ethiopia, followed by the application of sanctions by the League of Nations, propelled the Duce into the waiting arms of Adolf Hitler, dictator of the other great revisionist Power of Europe. Though the fate of Austria divided the two countries, the Rome–Berlin Axis was made public in November 1936, and after an interval in which they alienated the rest of Europe and deceived each other by a series of unlawful aggressions, this unequal and faithless partnership ripened into the more formal alliance of the ‘Pact of Steel’ (22 May 1939). Despite the obligation of each ally to give full military aid to the other should it go to war, no one was surprised when, upon the German invasion of Poland three months later (1 September 1939), Mussolini, well aware of Italian military unpreparedness, claimed for his country the novel status of non-belligerency.

Nothing in the first few months of the war caused Mussolini to regret a decision that had occasioned him some qualms of honour and some of calculation; but as the sweeping German successes against Norway and Denmark in April 1940 and the overrunning of France and the Low Countries in May threatened to rob him of the emoluments of quick victory, he decided to wait no longer. War he had already resolved upon late in March:2 now he advanced its date. To his chiefs of staff on 29 May he announced Italy’s imminent entry into hostilities. Delay, he explained, would only ‘give the Germans the impression that we were arriving after everything had been finished, when there was no danger. ... We are not in the

habit of hitting a man when he is down’.3 Such was not the world’s judgment when on 10 June Italy formally declared war on France and Britain.

Mussolini had always prided himself on being a tempista and the timing of this stroke was his and his alone. He gambled on an early French collapse and an early British surrender. These expectations were only partly fulfilled, and therefore his plans wholly miscarried. For Italy he purchased a war of less than a fortnight against a prostrate France, but the price he paid was a war of more than three years against the British Commonwealth and the allies that came to its side, and when that war was ended the long devastation of his country by invading armies and their air and naval auxiliaries, the overthrow of the Fascist regime and his own death in ignominy.

(iii)

According to the geopolitics of the three totalitarian Powers, Germany, Italy and Japan, who celebrated their solidarity in the Tripartite Pact of 27 September 1940, Italy’s allowance of the world was to be the Mediterranean. There, in the chosen field of her ambitions, Italy was to be permitted for the time being to pursue her advantages while Germany followed up her victory in the West by the subjugation of England.

In the last quarter of 1940, as it became apparent that the Luftwaffe had lost the Battle of Britain, Hitler’s interest dwelt temporarily upon the Mediterranean, where he contemplated ambitious operations extending from the Levant to Gibraltar and even beyond to the Canary Islands. Such difficulties as the naval hazards, General Franco’s politic coyness and the hard bargaining of Vichy, however, confirmed his preference for the project of an invasion of Russia.

It was therefore defensively, in response to an Italian appeal for aid in Africa and in her hapless venture in Greece, that about the turn of the year Germany intervened in the Mediterranean with air forces based on Calabria and Sicily, the first elements of the Afrika Korps in the desert and the invasion of Greece. Even after the Axis successes of April and May 1941 in the Balkans, Greece, Crete and Libya, the Germans, now deep in their Eastern plans, continued to regard the Mediterranean as primarily an Italian sphere.

(iv)

If to Italy the Mediterranean was a field for conquest and to Germany an area for resuming the offensive only when all others

were closed, to Britain it was a vital buttress to her security in the Middle East. Its loss would imperil Egypt (to Napoleon the most important country in the world), the Suez Canal, the Red Sea and the Levant, and thence, by the contagion of disaster, Turkey and the land bridge between Europe and Asia. Its mastery, on the other hand, would expose a hostile Italy to grave dangers, among them the severance of her supply line to troops in North Africa.

From the beginning of the war these possibilities for good and ill loomed clear in the mind of the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. He insisted, as Nelson had successfully argued in the comparable circumstances of 1798, that the Royal Navy should hold the Mediterranean, even at the risk of crippling losses from air attack and even though it proved necessary for three years after May 1940 for all but some twenty of the most urgent convoys for Malta and Alexandria to take the long and unavoidably wasteful route round the Cape. After the expulsion of the British Expeditionary Force from the Continent, the Mediterranean became the one theatre where British land forces could engage the enemy with some prospect of profit, and Britain’s scanty resources of war materials and shipping were strained to nourish General Sir Archibald Wavell’s Middle East forces, and especially those in Egypt.

Upon the fortunes of this desert army pivoted Churchill’s plan for the general conduct of the war – a plan adapted to the capacities of a maritime State fighting alone against a continental coalition which presented a tender flank to the sallies of sea power. An early hint of its nature was contained in a directive to the Chiefs of Staff Committee of 6 January 1941 to press on with the study of a scheme for the occupation of Sicily, which Churchill saw in October 1941 as ‘the only possible “Second Front” in Europe within our power while we were alone in the West’.4 Soon a definite sequence of operations was being envisaged. After the clearance of Cyrenaica and an advance into Tripolitania, the Eighth Army (as the desert force was now called) would enter French North Africa, with the assistance of the French if it was offered, thus putting the entire North African shore into British or friendly hands; or, as an alternative to the advance into French North Africa, the army might wheel northward to descend upon Sicily.

(v)

The opening phase of this plan was being executed when the Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbour; and two days after the siege of Tobruk had been raised Germany and Italy declared war on the United States (11 December 1941). From this moment the war in the Mediterranean, no less than elsewhere, assumed a new character.

Its strategic direction would now have to satisfy not only three fighting services but also two great Allies.

Early in their partnership these Allies made two paramount decisions, which the student of the Mediterranean war must carefully mark. The first, in logic as in time, was to give precedence to the European theatre and to the defeat of Germany, ‘the prime enemy’.5 It was grounded on the classic principle of concentration and the conviction that the fall of Germany must be followed by the collapse of Italy (if that had not already occurred) and by the defeat of Japan. The second great decision proposed the means. At a London conference in April 1942 Churchill accepted the American view that the principal Allied attack should be delivered in Western Europe across the English Channel, though it was not until the quadrant conference at Quebec in August 1943 that this frontal attack was formally given precedence as ‘the primary United States-British ground and air effort against the Axis in Europe’. Weighty arguments overbore all other solutions – the unrivalled facilities of the United Kingdom as a base; the opportunity, available nowhere else, to employ British metropolitan land, sea and air forces in an offensive role; the directness of the route from the Channel coast to the heart of Germany and the absence of great natural obstacles barring the way; the comparative ease with which preliminary air superiority could be won at the point of assault; and the economy in shipping and naval escorts during the long period of preparation as well as in the actual invasion.6

To the two master principles of ‘Germany first’ and the frontal assault both Allies remained fundamentally faithful, but in the application of these principles there lay scope for conflict of opinion and its reconciliation by compromise. When and in what strength to attack across the Channel, how to engage the enemy until the Channel enterprise was ripe, and at what point subsidiary operations ceased to assist and began to impair the main plan were disputable matters, and disputed they were. Opinion was often divided along professional lines; yet differing conditions of national life and of historic experience tended to foster a distinctively American and a distinctively British view of the place of the Mediterranean in the strategy of the war. Whereas British strategy, moulded by a long tradition of maritime warfare, emphasised

economy of force, the indirect approach and the flexibility of the empiric, the Americans relied rather on overwhelming weight, directness and strict adherence to a single master-plan.7

Whatever indulgence American naval opinion showed towards the Mediterranean approach was likely to be discounted by the frank attraction of the Pacific war; while American military opinion firmly favoured the most direct thrust at German land and industrial power and welcomed the opportunity to deploy the massive product of American war factories, confident that weight of metal, skilfully managed, could crush the enemy. This was the natural policy of a Power conscious of industrial supremacy and material might but without the experience of the human cost of a wide continental war. It was likewise in harmony with American aptitudes for large-scale planning looking to distant ends. By feeding men and machines into an assembly line and by committing the finished product, trained and equipped armies, to a single, scientifically planned stroke at the heart of the enemy, the Americans would give a new content to the old French phrase, ‘organiser of victory’. Any distraction from the Channel invasion was therefore regarded with reserve and sometimes with open misgivings by the highest American military commanders; and when tension existed between the two great Allies, it frequently sprang from American suspicions that the pragmatic British method of waging war meant the dribbling out of resources in a series of ineffectual ‘side-shows’.

The British method was a product of the momentum of the past and the imperious facts of the present. Never able to match her armies alone against the conscript masses of the Continent, Britain was cool towards heavy land commitments in Western Europe. Historic memories cautioned against the drain of human and material wealth by a second war of attrition, another 1914–18. War once being made, the traditional British formula for frustrating the would-be conqueror of Europe had been one of limited, if sometimes decisive, participation in continental warfare, the subsidising of allies whose manpower was greater than their wealth, the weapon of blockade and the exploitation on the periphery of the strategic mobility afforded by command of the seas. The typical expression of this policy was the amphibious outflanking movement, whereby the continental colossus might be wounded in the back and left to bleed.

There is a kind of strategic law of gravity that attracts British effort towards the southern entry into Europe, and in her last three great wars Britain has sought a ‘way round’ through each of the southern peninsulas in turn. Against Napoleon it was in the western or Iberian peninsula that eccentric operations found their classic

field. There for six years, from the late summer of 1808 until the spring of 1814, ranging from the Tagus to Toulouse, British armies under Moore or Wellington so stiffened the fierce patriotism of Spanish and Portuguese as almost fatally to sap the strength of the Napoleonic empire. In the First World War entry was sought through the eastern or Balkan peninsula in the well-conceived but tragically mismanaged Dardanelles expedition, which was intended to open direct sea communication with Russia through the Black Sea, eliminate Turkey, and sway other Balkan States towards the Allied cause.8

So inexorable is the dominion of history and geography over the strategist that no British mind pondering the means of overthrowing Hitler’s Germany could have missed the possibilities of the central or Italian peninsula; for there, as in 1808 and 1915, the Daedalus-wings of sea power offered escape from the labyrinth of continental war, and there too, as in the other peninsulas in the other wars, was the homeland of the weak and reluctant ally or satellite. Britain, observed Admiral Raeder with rueful insight, ‘always attempts to strangle the weaker’.9

Two other facts predisposed the British towards the indirect approach in general. One was their Prime Minister’s refusal to despair. From the superior eminence of the aftermath, it is possible to believe that, at least when the British Commonwealth fought alone, Churchill overrated the capacity of the oppressed peoples of Europe to help themselves. He hoped that the eventual return of British troops to the Continent would be the signal for widespread insurrection. It is this sanguine expectation that seems in part to have led him to contemplate a series of landings in scattered parts of occupied Europe in preference to a single frontal attack. A magnificent illusion which kept Britain free, it left its mark on his strategic thinking when the turn of the war opened safer courses. Secondly, the autonomy of the Royal Air Force encouraged an overestimate of the war-winning potentialities of strategic bombing. In the extreme form of this miscalculation, the task of the army was seen as little more than the occupation of territory and the rounding up of an already stricken enemy. So far as the belief in victory by air power alone was current,10 it undermined the case for husbanding

the British armies for a single dash across the Channel. The naval blockade, strategic bombing, the encouragement of clandestine resistance, the arming of civilians against the day of liberation, though by no means incompatible with the straight onslaught upon the enemy’s strongest defences, tended rather towards the mode of indirect approach.

The Mediterranean was not the only region in which the enemy flank lay open to attack, and Churchill was long an advocate of a landing in northern Norway to clear the Arctic sea route to Russia. Yet the Mediterranean was the most obvious choice. The alarming losses of Allied shipping in 1942 made its reopening as a regular convoy route urgently necessary to save the long haul round the Cape. The Japanese threat to India deepened the British desire to restore the quickest seaway to the East. Scarcely less influential was the investment Britain had already made in the Mediterranean. Since the Dunkirk evacuation, Egypt and Libya had been the scene of Britain’s major war-making by land, and the actions at Taranto and Cape Matapan had established the moral supremacy of the British over the Italian navy in the theatre.11 Moreover, the redeployment of the large British forces and their establishments already committed in the Mediterranean for tasks elsewhere would have been very costly in shipping, and at a time when it was necessary to bring British military power continuously to bear would have given the enemy a welcome respite. With America as a partner, the northward leap across the sea now seemed a still more desirable sequel to the hard-fought desert campaign, which Churchill was reluctant to see expire in a bathos of minor operations. Nor could any other theatre by the end of 1941 offer strategy such a wide array of choices.12

(vi)

The unfolding of the strategy that eventually carried the Allied armies to the Italian mainland was a succession of expedients, and save perhaps in the mind of Churchill, always its great mover, assumes only in retrospect such coherence as it possesses. Once the Allies had decided to embark their main fortunes on the invasion across the Channel, the Mediterranean was always potentially a

subsidiary theatre of effort and it became actually so by the end of 1943, when preparations in Britain for mounting the grand attack moved towards completion. At the Quebec conference in August of that year, it was agreed that in the distribution of scarce resources between OVERLORD and the Mediterranean theatre, the main object should be to ensure the success of OVERLORD. Though chronologically the second front against Germany, the Mediterranean was strategically only a secondary front. This fact Churchill himself underlined by calling it, in a speech to the House of Commons after the invasion of Italy, the Third Front13 – a gesture of reassurance to both his American and Russian allies.

Its importance as a theatre of war from April 1942 lay at the mercy of events external to it and beyond the shaping of those who fought there – the state of the war in the Pacific and in South-East Asia, the progress of the battle against the U-boats, the intensity of Russian pressure for diversionary operations, the range of employments open to Allied troops elsewhere, the turn of politics at Vichy or Madrid or Rome, and especially the preparedness of the armies that were to storm Hitler’s Festung Europa. Until the second front par excellence could be launched, it was better to march forward in the Mediterranean than to mark time at home. The Mediterranean, then, became the place where, at first, surpluses might be spent and, later, economies effected; it was the field for interim measures; strategically, it lived from hand to mouth.

Within a fortnight of the American entry into the war, and within a few hours of his arrival at the White House for the first of the Washington conferences between the two Western leaders and their staffs, the Prime Minister was pressing on the President an expanded version of his earlier Mediterranean projects – a combined Anglo-American expedition to clear the North African coast from the west, while the Eighth Army cleared it from the east, with the aim of restoring free passage through the Mediterranean to the Levant and the Suez Canal. Though the President, like the Prime Minister, was a ‘former naval person’14 and smiled upon the project, the conference broke up without taking a firm decision, and soon heavy misfortunes threw it into jeopardy. In the early months of 1942 blows fell thick and fast upon the Allies. Rommel’s advance to Gazala and Tobruk ended all hope of an early meeting of Allied forces working toward each other along the North African littoral; and spectacular Japanese successes in Malaya, Burma and the Dutch

East Indies caused a diversion of shipping to the East which, with mounting losses at sea, forbade for the time being any large-scale seaborne expedition in Europe.

It was, nevertheless, in April 1942, while these reverses were still in full flood, that Roosevelt, on the advice of his Chiefs of Staff, sought and obtained British assent to the principle of the Channel attack (round-up) as the main Allied effort, which was to be launched, if possible, in the spring or summer of 1943. But what was to be done in the meantime? On visits to London and Washington in May and June, V. M. Molotov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, made strong representations for the early opening of a substantial second front in Western Europe. By now competition was keen among rival plans for filling the interval until round-up could be mounted. Molotov’s visit had not weakened the American preference for the frontal attack on Europe, nor had Churchill’s renewed plea for the North African venture and his fresh plea for the liberation of northern Norway allayed American fears of the fruitless dissipation of power where it could achieve no decisive result. Roosevelt, therefore, at the urging of General George C. Marshall, proposed for the late summer or autumn of 1942 a more limited operation in northern France, perhaps at Brest or Cherbourg, where a permanent lodgment might be effected until in 1943 it could be expanded into a wholesale invasion of the Continent; meanwhile it would draw appreciable air forces from the Russian front. A further, though always remote, possibility was the employment of American troops in Egypt with the British or even farther east in Syria or the Persian Gulf.

The second of the Washington conferences (21–25 June) did little to resolve the issues. It was now mid-summer. No final plans for land operations in the West in 1942 had been laid. Russia, after a year of strenuous defence, was still unrelieved. Churchill’s forebodings about the toll of the French beaches were causing some Americans to wonder how much longer the Second Front would be delayed; and as their thoughts strayed towards the Pacific the strategy of ‘Germany first’ was momentarily endangered. In Britain’s overcrowded and food-rationed islands an American corps waited for work.15 Although the United States had been at war for more than half a year, American soldiers were nowhere at grips with Germans, and in early November the mid-term congressional elections would take place.16 On 1 July Sebastopol fell to the Germans, just as Rommel reached El Alamein and Churchill faced a vote of censure in the House of Commons – another levy upon

fortitude already heavily taxed by the misfortunes of the last six months. Above all, the danger of frustration at home in Britain and the United States and of discouragement in occupied Europe and in Russia made further delay in opening a land offensive hazardous.

(vii)

It was in these circumstances that Roosevelt resolved to break the deadlock. Hopkins, Marshall and Admiral Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Fleet, having failed in London to persuade the British that the Channel sortie was practicable in 1942, the President signalled a request for a date not later than 30 October for the combined landings in North Africa. Thus, at last, American might was to re-enter the Mediterranean, where in Jefferson’s time the United States fought against the Barbary corsairs their first overseas campaign, blockading and raiding ‘the shores of Tripoli’. It has been said that in this choice, largely that of naval minds, Roosevelt, exceptionally, overruled his highest-ranking advisers.17 Churchill himself described the slow emergence of the decision as ‘strategic natural selection’,18 but the historian is at liberty to suppose that the phrase attributes too much to nature.

Apart from the clamant need to seize the initiative, to hit out at the enemy in some direction and to employ and toughen idle troops, the prime strategic objects of torch, as the North African operation was now renamed, were the clearance of the Mediterranean for shipping and the destruction of the Axis army of the desert. It would also forestall (what was now indeed improbable) the German occupation of French North Africa, and when Marshal Stalin was let into the secret by Churchill in Moscow he discerned other strategic advantages – the overawing of Spain, the threat to Italy and the provocation of trouble between French and Germans. A gratuitous gain was the capture of the reinforcements Hitler poured into Tunisia.

On 23 October the Eighth Army, under General B. L. Montgomery, attacked at El Alamein; on 8 November the leading elements of the British First Army and the United States Second Corps, under the supreme command of the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, assaulted the beaches near Casablanca and Rabat, Oran and Algiers; and on 13 May 1943 General Sir Harold Alexander, commanding in the field the armies now united in Tunisia, signalled the Prime Minister: ‘We are masters of the North African shores’.19

(viii)

These shores, the Prime Minister had no doubt, were to be ‘a springboard and not a sofa’.20 Though the possibility had not yet been abandoned, the prolonged enemy resistance in Tunisia rendered more doubtful the mounting of the major invasion of northern France in 1943, and the reinvestment of Mediterranean profits promised richer rewards. The continuing need for relief to Russia could be most economically fulfilled in the Mediterranean, where formidable strength in men and shipping was assembled. It was still necessary to secure the sea line against aircraft based on the northern shore, and it was estimated that the possession of Sicily as well as of the North African coast would release 225 vessels for use elsewhere.21 Unremitting pressure would harry the Fascist regime in Italy and perhaps break the Axis. At Casablanca (14–23 January 1943) Sicily was therefore chosen as the next Anglo-American objective. Americans disturbed by the broadening Mediterranean prospect took consolation by reflecting that Sicily was a small island which could be inexpensively garrisoned and the occupation of which did not commit the Allies to further offensives in the area.

Yet it was hardly to be conceived that the conquest of Sicily would wholly absorb the impetus of Allied exertion. It is true that the third Washington conference (12–25 May) gave notice that henceforth the southern theatre must be strategically ancillary to the western: 1 May 1944 was tentatively fixed as the date for the Channel attack (OVERLORD) and from 1 November 1943 seven divisions were to be withdrawn from the Mediterranean for the purpose. Equally, however, it was made clear that vital work remained to be done there. To eliminate Italy from the war and to contain as many German troops as possible were the two aims set before Eisenhower, as Allied Commander-in-Chief in North Africa, to guide him in planning to exploit success in Sicily. He was to prepare suitable operations, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff would decide which to adopt.

Cogent reasons dictated both the choice of ends and the cautious approach to their realisation. The surrender of Italy would depress Germany and perhaps embolden Turkey to offer the Allies bases from which to bomb the oilfields of Ploesti and clear the Aegean;

it would burden the Wehrmacht with the replacement of between thirty and forty divisions of Italian garrison troops in the Balkans and southern France and probably with the occupation of Italy itself; it would eliminate the Italian fleet. To contain German troops also by active operations would take some of the weight off Russia and would give employment to Anglo-American forces which would otherwise be idle in the long period that was expected to elapse between the conquest of Sicily and the opening of OVERLORD. This last eventuality Churchill considered to be politically and militarily indefensible. Such aims were clear, but a variety of unpredictable factors counselled the utmost flexibility of method. How well the Italians would fight in defence of their own soil, when and in what circumstances they would surrender, how the Germans would respond to the increased threat to Italy, what precautions they would take in Sardinia, Corsica and the Balkans, how well Allied amphibious technique would stand the test of an opposed landing in Sicily and what casualties in men and equipment the invaders would suffer: these were secrets which had to be known but which only time would tell.

Since the United States Government vetoed a Balkan expedition, the choice lay between Sardinia, which had been passed over before in favour of Sicily, and the Italian mainland; and early in June 1943 planning for both alternatives began. Sardinia and Corsica were possible objectives if enemy strength on the mainland forbade invasion with the limited resources available to Alexander,22 commanding 15 Army Group. Their occupation would at least keep the Allied advance moving and destroy bases for air attack on Mediterranean shipping, but it would contain few German troops and would not of itself eliminate Italy from the war. It was to the mainland, then, that eyes, and more especially British eyes, were turned. Both at Washington with the President and later at Algiers with the Allied Commanders-in-Chief, Churchill argued powerfully for Italy as the only objective worthy of crowning the campaign and commensurate with Allied power in the theatre. He even offered a further cut in the British civilian ration to provide the shipping for moving extra divisions to Italian shores.

Facts were more eloquent still. The direct way to strike Italy from the war was an invasion of the peninsula, followed, if necessary, by the capture of Rome. Even if achieved otherwise, Italy’s defection would still require an Allied occupation in order to turn her

resources against Germany. If the menace of attack detained no more than second-class or foreign and satellite troops in the south of France and the Balkans, it was confidently expected that the reality of attack in Italy would draw the best German troops into the peninsula and discharge, far more effectively than any operations against the Tyrrhenian islands, the policy of containment. Divisions despatched to the south would be an earnest, if not of the Fuehrer’s personal loyalty to the Duce, at least of his desire to prop up a kindred political order, and of his habitual determination not to yield ground without a fight; there they would defend German prestige and the war industry of northern Italy; and there they would fight to keep Allied air bases as far away as possible from the south German sky23 and from the oilfields of Ploesti and to deny the Allies access to the Balkans by way of the Adriatic or the Julian Alps. These advantages, it was hoped, would repay an invasion of Italy. Its practicability awaited the verdict of the Sicilian event.

(ix)

The invasion of Sicily by the British Eighth Army and the United States Seventh Army began on 10 July. The early news was encouraging. So faint was the resistance of Italian soldiers, so cordial was the welcome of Italian civilians and so light were the casualties of the landing that Eisenhower almost at once recommended the attack on the mainland. On 20 July planning for Sardinia by the United States Fifth Army was cancelled. By a seemingly irresistible logic war approached Italy. First in May there had been the Allied decision to maintain the pressure in the Mediterranean after the fall of Sicily; now the pressure was to be applied direct to Italy; next would come the decision how to do so. The original intention of a landing in Calabria, with the danger of confinement within the narrow toe through the winter, was seen to be too unenterprising and was to be supplemented by operations against the heel of Italy or Naples.

Into the plain scales of military measurement were now thrown, not unexpectedly, the imponderabilia of politics. Mussolini’s dismissal was announced on 25 July, and though Marshal Pietro Badoglio declared that ‘the war goes on’ few were deceived. To both sides the news was a spur to action. The Allied Commanders-in-Chief interpreted it as authorising greater risks, and two days later General Mark W. Clark was directed to prepare plans for an assault landing by the Fifth Army in the Gulf of Salerno in order to seize the port of Naples as a base for further offensive operations.

Though every day that passed augmented the German strength in Italy, and though the four German divisions engaged in the 38-day campaign in Sicily had by 17 August made good their escape across the Straits of Messina, the Allies persevered with the boldest plan. The main weight was now to be transferred to the more northerly landings. The Eighth Army, with two divisions under the command of 13 Corps, would cross the straits into Calabria between 1 and 4 September, and about the 9th the Fifth Army would land near Salerno, with the United States 6 Corps and the British 10 Corps, commanding for the assault phase three divisions and supporting units.

The opposition to be expected was not then predictable, but it was hoped that Italians would not be among the defenders of Italy. On 15 August, the day before these decisions were finally confirmed, a secret envoy of Badoglio appeared at the British Embassy in Madrid bearing an offer from the Marshal that, upon invasion of the mainland, his Government would quit the German for the Allied side.

The Germans had long before resolved to fight for Italy and for that purpose had begun to make drafts upon divisions re-forming in France after mutilation at Stalingrad. At the thirteenth meeting of the two dictators, which was held at Feltre on 19 July, Hitler, though distrustful of the loyalty of some Italians, offered up to twenty divisions for the defence of the peninsula, but would not promise to post them permanently farther south than a line from Pisa to Rimini. News of Mussolini’s fall less than a week later shocked but did not paralyse the Fuehrer. The immediate reinforcement of Italy was ordered, partly to secure the communications of the German troops fighting in Sicily, partly to command without delay the Po valley and the important railway system of the north. From the end of July German troops poured into Upper Italy and within a month eighteen divisions were available to man the southern ramparts of the Reich. Six divisions south of Rome and two in the general area of the capital comprised the command of Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring. The remaining ten divisions, of which one and a half garrisoned Sardinia and Corsica, formed Army Group B, under Field-Marshal Erwin Rommel, with command of all forces in Italy and Italian-occupied Slovenia north of a line from Grosseto to Rimini.

Although these forces were so disposed as to dispute any likely landing save in Calabria, the Germans had not yet decided how much of the peninsula they would attempt to hold, nor was it until many weeks had passed that Hitler’s vacillating mind came to rest in favour of Kesselring’s advocacy of holding the invaders as far south

as possible. Meanwhile, strategy was fluid. Painful as it was to contemplate yielding without a blow the port facilities of Naples, the airfields of the south and the prestige of occupying the Eternal City, two anxieties troubled the Germans. The resistance, passive or active, of mettlesome civilians, such as the inhabitants of the industrial areas were reputed to be, might tie down so many troops that it would be prudent to restrict German territorial responsibilities to the more vital north, particularly in view of the possibility of the sabotage of transport and other public services. A more acute fear was that the Allies, by a silent sweep of amphibious power, would trap the German formations in the south by landings farther up the coast – a grave risk which Kesselring was, and Rommel was not, prepared to accept.24

German fears were Italian hopes. The slow progress of the armistice negotiations was primarily due to the Italian desire for an assurance that the Allies would land in such overwhelming strength as to guarantee the rapid success of the invasion and far enough north to safeguard a substantial part of Italy and of the Italian army from German reprisals. The preliminary Allied terms were of a military nature. Five or six hours before the main assault the Allied Commander-in-Chief would broadcast the conclusion of the armistice; the Italian Government would simultaneously confirm the announcement, order its forces and people to join the Allies and resist the Germans, despatch its shipping, fleet and air forces to Allied bases and release Allied prisoners. Though the Italian Government made no demur to the terms, it sought an undertaking that at least fifteen divisions would be landed north of Rome. Refusing to disclose their much more modest intentions, the Allied negotiators offered the dropping of an airborne division to assist in the defence of Rome, made known the Allied determination to proceed with the invasion as planned, and set a date for the acceptance or rejection of their new offer.

Italian hopes of the Allies outweighed their fears of the Germans. Late in the afternoon of 3 September, the fourth anniversary of Britain’s entry into the war, the armistice was signed at Alexander’s headquarters near the Sicilian village of Cassibile. Early that morning, under a barrage fired from the southern shore of the straits, the Eighth Army had made an easy landing and was already advancing through Calabria.

On 8 September, as the Fifth Army convoys headed northward into the Tyrrhenian Sea before turning towards the Salerno beaches, one last crisis arose. The public announcement of the armistice, timed to precede the landing by a few hours, was to be made that

evening. Now Badoglio sent a message that strong German forces threatened the three airfields near Rome on which the airborne division was to land. The attempt should not be made and he could not therefore announce the armistice until the seaborne invasion had succeeded. It was just possible to cancel the airborne operation, but to Eisenhower’s sharp reminder of his engagements Badoglio gave no reply. It was thus with doubt as to their efficacy that Eisenhower, at the appointed time of 6.30 p.m., broadcast the announcement of the armistice. At 7.45 Badoglio’s voice confirmed to the Italian people the surrender of their Government.

The next morning upwards of three divisions stormed the Salerno beaches. Though in the end they had to fight bitterly to establish themselves, the invaders were greeted by only one of the eighteen divisions sent to guard Italy.

(x)

The strategy by which war came to Italy is not without interest to every man who fought there. Why men fight is a question not to be answered in military terms; but why they fight here rather than there and at one time rather than another can be explained, as well as history can ever explain, by uncovering the course of strategy, and the campaign in Italy was the conclusion, if not the culmination, of a strategical process that has nothing less than the whole Mediterranean war for its context. In all wise war-making, the strategic purpose of a campaign tyrannises over the way it is fought, as means are subordinate to ends. The place of the Italian campaign in the entire curriculum of Allied conquest dictated in large part the resources allotted to it, the tempo at which it was conducted and even the character of the enemy response; thence the demands imposed upon troops, the objectives they were set, the risks they were ordered to bear, the reliefs and amenities they could be afforded, the casualties they sustained, the relations they established with allies in arms and civilians – in short, most things done and suffered. In the last resort, the determinations of high strategy, gathering ever greater particularity as they filter down, are despatched, ill or well, in the orders of the artillery sergeant to his layer or in the pointed finger and breathless word of the section commander.

Earlier pages have shown how halting and tentative was the strategic prelude to the war in Italy. Opportunism and improvisation led the way. At every successive step, voices were raised in doubt and heads were turned back towards the Channel coast. With the engagement of the enemy and the deployment of Allied power as major aims, the next advance was frequently valued rather as a

Italy

movement than as a movement in a preordained direction. ‘We are off to decide where we shall fight next,’ wrote Hopkins on his way to Casablanca, where Sicily was the choice.25 ‘Where do we go from Sicily?’ asked Roosevelt a few months later when a fresh expedient fell due.26

The decision to enter the Italian mainland was taken only six weeks before the event; and the Fifth Army laid plans for four different courses of action. Though it was correctly supposed that the Germans would defend Italy, no one knew at what point, and no deep study had been given to the implications of a long campaign in the peninsula. It was known, indeed, that troops and landing craft must in future be strictly limited. Seven of the most experienced divisions in the theatre (later raised to eight) were already destined for OVERLORD, and the agreement of the Quebec conference in August on the invasion of the south of France in the summer of 1944 could be expected to deprive the theatre of further seasoned troops. No definite geographical objectives were assigned to the planners of the campaign, and though the port of Naples and the airfields of Foggia were obviously desirable goals, and were often mentioned as such, Churchill himself, the most enthusiastic exponent of the enterprise, had been content to follow the lead of opportunity.27

These facts carry in themselves no censure; they simply suggest the extreme fluidity of the political and military situation. In this vexed sea of incalculables – ranging from the state of the weather to the moods of an Italian marshal – the Allied commanders steered on the compass bearing given them in May: the directive to eliminate Italy from the war and contain the maximum number of German troops.

When the Fifth Army went ashore near Salerno, the first of the two desiderata had been fulfilled: if not positively eliminated from the war, Italy had chosen a seemingly auspicious time to leave it. There was some disappointment that Rome fell so easily to the Germans and that the resistance of what Goebbels was now pleased to call ‘a gypsy people gone to rot’28 was so pusillanimous, but solid achievements remained – the bulk of the Italian fleet rallied to the Allies and, more important, the Germans now had to find substitutes for the lost Italian troops.

The second objective could not by its nature be attained in a single stroke; and it became the continuing purpose of the campaign just beginning, which Alexander was to describe as ‘a great holding

attack’,29 to draw as many German divisions as far away as possible from the decisive theatres – the existing front in Russia and the projected front in northern France. To inflict losses in men and materials and to compel their replacement and the provision of supplies over long, tortuous and vulnerable lines of communication was implicit in this aim. By vigorous action in Italy, the Allies would show their unflagging interest in the Mediterranean, maintain their threat to the German position in southern Europe, and prevent the enemy from relaxing his watch in the south of France and the Balkans. Finally, the waging of war without pause was one of the few means open to the Allies of cheering the spirits of the peoples in the remoter parts of German-occupied Europe.

These were the reasons why the Allies made a battlefield of Italy’s fair and famous land.

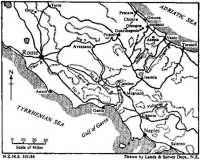

The Land of Italy

(i)

Geography, as Uncle Toby assured Corporal Trim, is ‘of absolute use’ to the soldier. How well did the physical shape of Italy fit it for the strategic purposes that the campaign there was intended to serve? Italy, to all-comers rich in history, is to invaders poor in geography. Especially is this true of those relatively few invaders who, like the armies of Justinian in the sixth century and the Norman adventurers of the eleventh, have had to fight their way from south to north. From a military point of view the most significant geographical features of the peninsula are the extent of its coastline, its narrow, elongated shape, its mountainous contours and its climate.

Segregated from continental Europe in the north by the lofty barrier of the Alps and for the rest by the Mediterranean and its two gulfs of the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas, Italy has, as Mazzini said, her ‘sublime, irrefutable boundary marks’. But the defensive value of these two boundaries, the alpine and the maritime, is very unequal. A water frontier of about 2450 miles gives the Italian mainland the longest coastline of any European State and exposes it dangerously to the thrust of hostile sea power. Except for about 120 miles on either side of Genoa, few considerable natural defences exist to balk an invader, and although their gradients vary and they are in part closely overlooked by hills, numerous beaches, particularly on the west coast, offer suitable landing places. The coasts are too long to be thoroughly fortified and manned, and

except at a few selected strongpoints the defence would have to rely on mobile forces held in reserve for movement to threatened localities rather than on permanent garrison troops. Given a sufficiency of assault equipment and imaginative leadership, an invading army by delivering, or even simulating, seaborne operations behind both flanks of the enemy’s front could compel him to dispose considerable forces in a state of readiness for coastal defence and could, in favourable circumstances, escape from the stalemate which it would be the aim of the enemy to impose.

(ii)

The defender, on the other hand, is favoured by the narrowness of the peninsula, which is nowhere wider than 160 miles and which at one point between Naples and Rome curves inward to a waist only 85 miles across. By stabilising his front at right angles to the north-westerly and south-easterly axis of the peninsula, the defender would effect the maximum economy in troops. In this object he is assisted by the mountain structure. Thrown off from the Maritime Alps in an easterly direction, the chain of the Apennines in north-eastern Tuscany bears to the south and then conforms to the general trend of the peninsula, forming, as it were, a backbone somewhat displaced in central Italy towards the east coast. The spurs and re-entrants running off eastward to the Adriatic from this central spine thus confront the invader with successive ridges and rivers squarely athwart the line of his advance. The rivers draining this massif, both to east and west, are subject to sudden and unexpected flooding, which may disconcert or even thwart the plans of an attacking commander.

The Apennines further ease the problem of defence by effectively closing to the attacker a large proportion of the front from coast to coast. In the Abruzzi, where the peninsula is most mountainous, crests above 3000 feet take in a width of more than half the peninsula. In such tangled country a front of 25 miles can be securely held by a single division. The same mountain barrier, by obstructing lateral movement from east to west, is likely to penalise the attacker more than the defender, since it reduces flexibility and makes it more difficult for the commander to switch the weight of his attack from one part of the front to another. On the other hand, if he achieves surprise and massive superiority at the point of attack, slowness of communication may well double his success by excluding many of the defending troops from the decisive battle. The division of the front into two distinct sectors also presents the high command with the task of co-ordinating the activities of two forces, each of which is tempted to fight an independent battle. Particularly when

The narrow waist of the Italian Peninsula

the boundary between two armies runs along the crests there is a lively danger, not merely of a disjunction of effort, but of actual misunderstanding and dissension. Mutual isolation may easily breed mutual grievance.30

(iii)

The large area of hilly country makes the tank on the whole a less effective weapon than in most parts of Europe, and sets a premium on hardy and skilled infantry trained in mountain warfare. Artillery, while afforded good observation, finds it harder to search broken country where the cover is plentiful, and is likely to see its ammunition expenditure increasing proportionately with the difficulty of supplying it. Though free armoured movement is possible in some areas of rolling country such as that immediately around Rome, visibility is often restricted by olive groves and vineyards; and where the land is quite flat, as in the Po valley, it is intersected by innumerable watercourses and the frequent hamlets

offer positions from which the rapid advance of tanks can be hindered.

As a consequence of its mountainous nature, the peninsula has a communication system that is easily disrupted. While the northern plains are served by an intricate network of railways, there were in 1943 only three lines to ‘stitch the boot of Italy’ from north to south, all of them, because of the large number of bridges, viaducts and tunnels, sensitive to air attack and capable of swift and efficient disablement by a retreating army. The road system, though often the work of resourceful engineers, would be severely strained by the burden of heavy military traffic in addition to that diverted from the railways.

In such a country the roads were bound to dictate the direction of military effort. Though even in Italy all roads do not lead to Rome, the capital is certainly the pivot of communications, and for this reason alone its possession confers great tactical advantage. The roads vary in quality. First in importance – for the autostrade were then too few to be militarily significant – are the great highways (the nineteen principal Strade statali). These are generally wide, easy in gradient and well surfaced, though sometimes very serpentine, and in the event they stood up well to wear-and-tear by army lorries, scarifying by tank tracks, and pitting by shells and bombs. The lesser roads are more liable to break up. They are frequently narrow, steep, or twisting and may run for long distances without affording motor vehicles either turning space or means of access to the surrounding countryside. At the crossing of rivers, valleys and defiles, in mountain passes and at other critical points, all roads are easy to block and some are hard to clear. In rugged country roads are few. In sum, communications are such as to rob a highly mechanised force of much of the advantage to be reaped elsewhere from superiority in machines, and even in certain circumstances to transfer the advantage to the force that moves on hoofs and feet; and the comparative paucity of capacious roads limits the choice of thrust lines and so the versatility of the attacker.

(iv)

The climate tends to the same result. To the summer visitor a land of warm sunshine and bright moonlight, Italy takes on a less hospitable aspect as autumn deepens into winter. The rainfall is abundant, never much below an annual average of 20 inches in the inland south and rising to over 50 inches around Genoa. It is often heaviest in November, and from that month until April the movement of motor transport off roads and other hard surfaces is seriously handicapped. Thick, clogging mud and steep hillsides,

many of which are terraced, not only impede the use of tanks but also slow up the pace of infantry and shorten the objectives that can reasonably be set. Though the lighter field pieces can usually be manhandled into the best position, medium and heavy guns must often be sited for convenience of access to roads rather than to satisfy more technical requirements. The eastern slope is drier and sunnier than the western, but by way of compensation it is steeper and therefore more eroded. Even in the northern plain snow and mud may bring an army almost to a standstill in winter. In some parts low-lying areas flood or become very damp and confine motor vehicles to roads running along the top of embankments, which the enemy can readily breach.

Though the sea is never far away from any part of the peninsula, its moderating effect on the climate is offset by the ribbon of highlands, the peaks of which are snow-covered for several months of the year, and the range of temperature is exceptionally great. The mild, equable Mediterranean climate of tourist literature does not survive the test either of statistics or of experience the year round. Temperatures high in summer become in winter bracing to the point of severity. The spread of temperature between the hottest and coldest months at Alessandria in the northern plain is 43 degrees F. and drops to 26 degrees at Palermo on the north coast of Sicily, but it is always above 25 degrees – a notable amplitude.31 The military implications are clear. Even in static warfare the rigours of the Italian winter make heavy demands on the physical and moral stamina of troops in the field; and much more so when strategic necessity calls on them to sustain a steady attack.

The climate and terrain awaiting the New Zealand Division in Italy were therefore a contrast to those in which they had trained and fought in the desert. In quitting the battlefields of desert Africa for Italy, they were exchanging, at least for the time being, heat for cold, sand for mud, flats or mild undulations for hills and mountains, freedom of movement for road-bound restriction, and an arid waste sparsely peopled for a land where the arts of peace had long flourished and where armies had manoeuvred and met since the infancy of Europe.