Chapter 2: Return to Battle

The Political Decision

(i)

NO inevitable fate but a free Parliament freely choosing between alternatives almost equal in the balance now ruled the destiny of 2 New Zealand Division. It was a choice by democratic process that enabled New Zealand soldiers, returning to Europe after their victorious march along the North African shore, to avenge in Italy the discomfitures of Greece and Crete. The decision to employ the Division in further operations in the Mediterranean theatre rather than to withdraw it for service against the Japanese in the South Pacific issued from an interplay of complex and often conflicting forces – the claims of strategy and politics, of sentiment and the economics of manpower and production, of loyalty towards Great Britain and the United Nations and neighbourliness towards Australia, of ‘logistics’ and humanitarianism.

That in the mid-twentieth century no nation could live unto itself as an island and that the seas which divide also join was the unspoken premise of this resolve. The discussions preceding it displayed both the extent and the limits of New Zealand’s sovereign status – the extent because in her lay the power to hinder, by abrupt disengagement, the execution of far-reaching war plans, and the limits because her choice was conditioned not solely by her own immediate national interests but also by those of fellow members of the British Commonwealth and the United Nations.

It may indeed seem that, in choosing as she did, New Zealand acted not boldly but traditionally. It would be possible to represent New Zealand as still the satellite of Britain, committing her fighting men in the Middle East and Mediterranean because their fathers had fought there, and because there lay a strategic sphere as peculiarly British as the Pacific was peculiarly American. Such an argument might appear to draw further strength from the recent reallocation of strategic responsibilities within the Commonwealth, whereby New Zealand relinquishes duties in the Middle East for duties nearer home. But on the whole this is to suppose that the choice was made in instant and unthinking obedience to a tradition.

Nothing could be less true. It may rather be that the historian of New Zealand will see in the torment and self-examination to which it gave rise one of the great maturing moments of the national life and conclude that never did a New Zealand Parliament make a more difficult, a more adult or a less insular decision.

These reflections, however, are not for the historian of the Division, who must be content to submit brief facts as prologue to the swelling act of the military theme.

(ii)

The security of the Middle East had been the purpose of Churchill’s decision in 1940 to denude the homeland of armoured troops for despatch to Egypt, and it was for the same end that New Zealand had maintained the Division overseas even in the most sombre hour of Japanese success in the Pacific during the first half of 1942. The advance from El Alamein and the Anglo-American landings in North Africa seemed to the New Zealand Government an assurance that the Middle East was now safe and that the Division ought to be recalled to assist either in repelling a further Japanese offensive or in the Allied counter-attack that must soon be mounted. With the impending departure of 3 New Zealand Division to the South Pacific islands and the requirements of naval and air forces there and elsewhere, the troops available for home defence were fewer than the Chiefs of Staff judged wise. The withdrawal of more than 163,000 men and 5000 women from industry was taxing the efforts of the Dominion to provide food and other essential supplies for export and for the use of American forces under the mutual aid agreement of September 1942 with the United States Government. The long absence from home of 2 Division (most of its men had been overseas for more than two years) and its heavy casualties (18,500 of a total of 43,500 sent to the Middle East), together with a natural wish to see these most experienced troops employed in the South Pacific for the defence of New Zealand, were making public opinion restive, or so the Government feared. It was predicted that if the 9th, the last of three Australian divisions in the Middle East, were to be recalled, as the urgent request of the Commonwealth Prime Minister (John Curtin) suggested it would be, the agitation for the return of the Division would become irresistible.

As the Division lay outside Bardia on 19 November 1942, pausing in the pursuit of the enemy that had begun at El Alamein, the Prime Minister (Peter Fraser) addressed these arguments to Churchill, adding the opinion, which was at odds with the assumptions of. Allied strategy, that the conflict with Japan would be long

Organisation, Chain of Command, and War Establishment by Units of 2 New Zealand Division

and difficult, irrespective of success in the war against the two Axis Powers. Twice within a fortnight Churchill telegraphed a friendly objection. It would be regrettable to see the Division ‘quit the scene of its glories’; the possibility of large-scale action in the Eastern Mediterranean in the early spring would compel the replacement of formations withdrawn from the theatre; and, above all, the shipping needed to move the Division could be diverted only at the cost of denying transport to 10,000 men outward from the United Kingdom and 40,000 men across the Atlantic in the accumulation of strength for the invasion of the Continent. The recall of 9 Australian Division, by weakening our armed forces in the Middle East and straining our shipping resources, made it more necessary to retain the New Zealand Division in its place.

In Washington the Combined Chiefs of Staff, with less reticence of language, found ‘every military argument’ against the request of Curtin and Fraser. It would reduce the Allied impact upon the enemy in 1943, and by diverting ships seriously dislocate United Kingdom and United States movements. To Marshall, it appeared that the move would actually enfeeble the immediate defence of the two Dominions by delaying the reinforcement of Burma and the Far East; to others, it would prejudice operations in progress in the Mediterranean and unsettle British and Indian troops whose service there had been longer than that of the New Zealanders and Australians.

While Curtin’s mind was made up and the transfer of the Australian division proceeded, New Zealand proved to be in no need of the involuntary tuition given by the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the entanglement of one ally’s affairs with all the others’. On 3 December, the day before the case was considered at Washington, the House of Representatives in secret session decided, on the strength of Churchill’s plea, to leave the Division in the Middle East for a further period, without prejudice to the revival of the question at a more opportune time. There, except for expressions of gratitude by Churchill and Roosevelt and of implied dissent by Curtin, the matter rested for four months. None but the enemy would contend that the Division could have made better use of the time thus won than it did on the road from Bardia to Tunisia.

(iii)

When the House of Representatives made this temporising decision, Fraser gave a pledge that the Division would not be employed in any other theatre without the approval of the House and promised that its future would be reviewed at the end of the Tunisian campaign. This review was hastened by a proposal of

mid-April to engage the Division in the assault phase of the coming invasion of Sicily. Montgomery wanted to prolong the partnership of the New Zealand and 51 (Highland) Divisions in 30 Corps, which was his most experienced and highly trained and which worked, in Churchill’s words, ‘with unsurpassed cohesion’. The Division would have to be moved at once from Tunisia to Egypt for two months’ amphibious training. The condition of urgency, imperatively necessary since the date for the invasion was less than three months away, caused Churchill’s invitation to be declined. Fraser was reluctant to call an early meeting of the House of Representatives for fear of rousing undue alarm and speculation and for security reasons, nor would he anticipate its attitude to the British request. An offer by the New Zealand War Cabinet to permit the Division to be withdrawn for special training subject to parliamentary approval of its actual employment in Sicily was unacceptable to the planners, since facilities existed for the amphibious training of only one more division, of whose participation they must be certain.

If the Division was not to assault the Sicilian shores, what of the later Mediterranean operations upon which the British had set their hearts? How did their claims compare with those of the Pacific war? The choice between the two theatres was becoming exigent. In the fourth year of war New Zealand could no longer call upon enough men to maintain indefinitely at full strength 2 Division in the Middle East and 3 Division in the South Pacific, as well as meeting her other commitments by land, sea and air, on the farm and in the factory. Though the home defences were now manned by a mere cadre and industry had been combed for ail fit men, the day of decision could hardly be postponed beyond the end of 1943. Three main options would then arise: one of the two divisions could be withdrawn; the establishments of both could be reduced; or one could be reinforced from the other. Many and eminent were the witnesses cited and grave and double-edged the arguments rehearsed when on 20 and 21 May the House of Representatives, behind closed doors, debated the issue.

(iv)

The case for the transference of 2 Division to the Pacific theatre rested principally on political, but partly on strategic and humanitarian, grounds. New Zealand, as a party to the setting up of the Allied command in the South-West Pacific area, had accepted the obligation to act on its directives, and these called for the use of all available resources. The strongest possible British representation among the Allied forces that would soon seize the initiative in the

Pacific was needed to ensure British influence at the peace table; at the existing stage of the war, such representation must largely depend on the exertions of Australia and New Zealand. ‘The Union Jack should fly here as the standard of British interest in the Pacific,’ wrote Curtin, whose views were fully placed before the House.

Australia, whose great bulk had shielded New Zealand from immediate peril of Japanese attack and which had supplied her with munitions, had claims upon the gratitude, or at least the willing co-operation, of the Dominion. Having recalled three divisions from the Middle East to fight in the disease-ridden islands of the Pacific, Australia might feel that the retention of the Division in the more lenient climate of the Mediterranean betrayed scant appreciation of New Zealand’s responsibilities in the Pacific and of the charity that should begin at home, and even, should 3 Division have to suffer reduction, direct defiance of the Commonwealth’s appeal for greater energy and resources in the theatre.

It was also argued, if not exceedingly arguable, that, since a holding war was the object of Allied strategy in the Pacific until the defeat of Germany, by neglecting to replenish the wastage of manpower there, Australia and New Zealand might fail in their assigned role and thus bring about the collapse of the whole strategic plan.

To cease to reinforce 3 Division and allow it gradually to dwindle until its offensive value disappeared would depress the spirits of the men in New Caledonia.

Finally, the move of 2 Division nearer home would conveniently make possible leave, or even relief, for its members who had been long overseas.

(v)

Yet the weight of argument lay on the other side. Strategically, the opinion of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in November had not been outmoded by events in the meantime, and it was now disclosed to the House. So was a more recent expression of the views agreed upon by Churchill and Roosevelt, who were at the time in conference at Washington. They regretted the possible loss of the Division to the Mediterranean theatre and hoped that means would be found for sustaining both divisions in their existing strength and station, failing which they advised accepting the need, as it arose, for lower establishments. This message left no doubt about the serious hindrance the transport of the Division to the Pacific would impose upon the massing of American troops for the continental invasion. Since the United States was heavily committed in both theatres, the President’s preference for the Mediterranean as the right place for

the Division was impressive. It now appeared, since the German capitulation in Tunisia a few days earlier, that operations of great potentiality were imminent in Europe, while in the Pacific the tide of Japanese victory had turned and the threat to New Zealand shores was receding. This was no time to abandon the strategy of ‘Germany first’.

Of prime importance in determining Parliament’s attitude, because it built a bridge between strategic need on the one side and the claims of humanity and the politics of welfare on the other, was the scheme for bringing home on furlough long-service members of the Division. The Minister of Defence (the Hon. F. Jones), who visited the Division in Tunisia in April and May, discussed its future employment and the return of its long-service members with the General Officer Commanding the Division (Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg).1 He reported to the Prime Minister that a period of furlough would be welcomed and that, in his opinion, it would satisfy the men. Arrangements were already in train for the return on furlough of 6000 men of the first three echelons, who would sail from Egypt in June and be replaced by reinforcements leaving New Zealand in July by the same ship. Jones thought that, while many men of the Division would be glad to return to it after furlough, there was no enthusiasm for service in the Solomon Islands. This opinion strengthened the case for retaining the Division in the Mediterranean, because it was now apparent that it would be easier to reinforce the 2nd from the 3rd Division than the 3rd from the 2nd.

The need for training the replacements of men on furlough and for reabsorbing into the Division 4 Armoured Brigade, which had still not received its full complement of tanks, would prevent the Division from taking part in any European operations until at least October, and the request for its employment as a follow-up division in Sicily could not therefore be met. But the repeated applications of Alexander and Montgomery for its services told the House a gratifying tale.

Two other testimonies were heard with the deepest respect. One was volunteered by General Freyberg. Writing on the morrow of the German surrender, when the fruits of the long war in Africa were being gathered, he naturally recalled the trials and triumphs of his Division, the inspiration which it had shed, the repute in which it stood, and the confidence with which it would face the future of a European campaign if called on to do so. Between the lines of this

message the least acute member of Parliament could not fail to read the pride of a general in his veterans and the desire that they should end together what they had begun and pursued through bad times and good

The other message, solicited for the occasion by the Prime Minister, was of Churchill’s composing. As so often before, the British war leader set the magic of his style to the service of a cause. Instructed by a true reading of New Zealand history, he sounded the strain of imperial unity; and to a House the more impressionable from its unfamiliarity with eloquence he addressed sentences resonant with the cadences of Gibbon and ornamented by a reminiscence of Tennyson.

There have been few episodes of the war [he wrote] more remarkable than the ever-famous fighting march of the Desert Army from the battlefields of Alamein, where they shielded Cairo, to the gates of Tunis, whence they menace Italy. The New Zealand Division has always held a shining place in the van of this advance. Foremost, or among the foremost, it has ever been. There could not be any more glorious expression of the links which bind together the British Commonwealth and Empire, and bind in a special manner the hearts of the people of the British and New Zealand isles, than the feats of arms which the New Zealanders, under the leadership of General Freyberg, have performed for the liberation of the African continent from German and Italian power.

There are new tasks awaiting the British, American, and Allied armies in the Mediterranean perimeter. As conquerors, but also as deliverers, they must enter Europe. I earnestly trust that the New Zealand Division will carry on with them.... On military grounds the case is strongly urged by our trusted Generals.

Yet it is not on those grounds that I make this request to the Government and people of New Zealand.... It is the symbolic and historic value of our continued comradeship in arms that moves me. I feel that the intervention of the New Zealand Division on European soil, at a time when the homeland of New Zealand is already so strongly engaged with Japan, will constitute a deed of fame to which many generations of New Zealanders will look back with pride....

The discussion, in secret session of the House, on resolutions adopted by a joint meeting of the Government and War Cabinets, though earnest, was neither acrimonious nor long, and only six or seven members dissented from the general conclusion that the Division could be most effectively used in the Mediterranean area. Without dividing, therefore, the House resolved that the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force should remain in the Middle East and be available for operations in Europe. Both the Mediterranean and the Pacific forces were to be maintained as long as possible with increasingly smaller establishments in accordance with the availability of manpower and, apart from their immediate replacements, no further reinforcements were to be provided until the 6000 men

on furlough in New Zealand again became free for service. In choosing independently to describe the decision as farsighted, Churchill and Freyberg seem likely to have anticipated the verdict of posterity.

II: Rebuilding the Division

(i)

While Parliament debated its future, the Division was making the long eastward journey back from Tunisia to the Delta. The arrival at Maadi Camp, near Cairo, early in June opened a four months’ period of re-equipment, reorganisation and training. The reliefs resulting from the furlough scheme, the return of 4 Brigade as an armoured formation, new equipment and a new mission were the four cornerstones on which the Division was rebuilt.

(ii)

The Nieuw Amsterdam, sailing from Egypt on 15 June with the first furlough draft (ruapehu), removed about three-quarters of the veteran troops of the first three echelons – 200 officers and 5800 men.2 Though few officers above the substantive rank of major accompanied the draft and a high proportion of junior officers, NCOs and technicians had to be retained, an immediate weakening of the Division was inescapable. Fighting units were particularly depleted, since among unmarried other ranks only those with field service were entered in the leave ballot.

By the time the replacements had joined their units at Maadi, the Division, considered as a group of men, had been substantially transformed, gaining in freshness but losing in experience. In a typical infantry battalion, few but the commands and technical posts were filled by original members; most of the older reinforcements

had found their way to administrative duties, leaving the rifle companies with a sprinkling of men of the 4th to 7th Reinforcements, with three years’ to eighteen months’ experience, and, for the rest, with the 8th Reinforcements, who had fought in Tunisia, and the 9th and 10th, who had only recently arrived from New Zealand. Among the gunners and engineers, who had suffered fewer casualties than the infantry, experienced men were still a majority and, for the same reason, they were even more preponderant in New Zealand Army Service Corps and other second-line units.

Continuity of command was well maintained between the Division’s return to Maadi and its departure for Europe. The loss of Freyberg from command of the Division, if not of the Expeditionary Force, was indeed at one time a possibility. As early as April 1943 the New Zealand Government, in its anxiety not to allow his association with the Division to prejudice his well-earned prospects of promotion, had raised the question of his future with the British Government, and in the last stages of the fighting in Tunisia General Montgomery appointed him to temporary command of 10 Corps. Freyberg’s own attitude was straightforward: he was ‘wholly content’ with his existing status, and his personal ambition was to see the war through to its end with the Division he led, though if the wider war effort required him to serve elsewhere he would reconsider the matter in consultation with his Government. An opportunity for personal discussions arose shortly afterwards. In June Freyberg, leaving Brigadier Inglis3 to command in his absence, returned to New Zealand by air, arriving on the 20th and departing again on 10 July. In these three weeks he travelled the country, making many public speeches, as well as conferring with the Government. The result of his consultations was to confirm the status quo. Nor, with two exceptions, was it seriously disturbed elsewhere in the hierarchy of command. Brigadier Parkinson4 took over 6 Infantry Brigade from Brigadier Gentry,5 who returned to

New Zealand to become Deputy Chief of the General Staff, relieving Brigadier Stewart;6 and Brigadier Kippenberger,7 who returned to New Zealand in command of the furlough draft, temporarily relinquished to Brigadier Stewart his command of 5 Infantry Brigade.

(iii)

The conversion of 4 Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Inglis) to an armoured role and its reunion with the Division, however, had effects far beyond its own ranks. After suffering severe casualties in the Ruweisat Ridge action in July 1942, the brigade had been withdrawn for tank training at Maadi. Equipped with 150 Sherman tanks, it was preparing to provide New Zealand infantry for the first time with New Zealand armoured support. The tactical doctrine of the whole Division had to be reviewed in the light of its new mobility and fire-power; infantry and tanks had to be practised in mutual support and to grow together into a reciprocal fidelity; the field artillery had to be attuned to the tempo of armoured advance with its opportunities for prompt observed fire on fleeting targets; the engineers could foresee heavier wear-and-tear upon roads and more frequent summonses to build bridges; signallers would have to lay their telephone lines more securely beyond the callous reach of steel tracks and be prepared to operate a vastly improved and enlarged wireless network; and to the rearward units tanks which had to be transported, recovered, repaired, refuelled and munitioned were more exacting masters than the marching infantry they had supplanted.

Re-equipment was not confined to 4 Brigade. The Honey tanks and Bren carriers of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment were exchanged for Staghounds, armoured cars mounting a 37-millimetre gun, tough and sturdy but of a somewhat conspicuous silhouette. The infantry were given more striking power by the Piat (projector infantry anti-tank) and the 42-inch mortar, and better means of control by the No. 38 wireless set. The Piat, a one-man weapon firing a rocket projectile of great penetration, soon showed its superiority over the Boys anti-tank rifle. The 38 was a portable wireless set of short range designed primarily for communication between

infantry companies and their platoons, and between infantry and supporting arms; despite its limitations where the infantry were dispersed in hilly and wooded country and among buildings, it was a useful aid in the difficult task of keeping touch between and controlling small bodies of infantry, and it gave the platoon a handy means of calling for the help of armour and artillery and of relaying information back to commanders. The 20-pound bomb which the 42-inch mortar fired accurately up to 4200 yards was especially effective against enemy posts in buildings, and was able, with its fast rate of high-angle fire, to reach reverse slopes with heavy concentrations. These weapons were placed at the disposal of the two infantry brigade headquarters. The engineers received additional heavy roadmaking equipment – six bulldozers (where they had previously had two), mechanical shovels, dump trucks and a grader, besides more 3-ton trucks. This material was transferred from 21 Mechanical Equipment Company, which was now disbanded along with the non-divisional railway construction and operating companies.

The bare anatomy of the Division thus reinforced, reorganised and re-equipped may be summarily described. Reconnaissance was the prime function of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment with its armoured cars. There were three brigades, two of infantry and one of armour. Each of the infantry brigades was made up of three battalions and the armoured brigade of three armoured regiments, one motorised infantry battalion, and its own workshops. The divisional Commander Royal Artillery (Brigadier Weir)8 had under his command the seventy-two 25-pounders of the three regiments of field artillery, an anti-tank regiment armed with 17-pounders and 6-pounders, a light anti-aircraft regiment of Bofors guns, and a survey battery. Further direct support for the infantry was given by the Vickers machine-gun battalion. The engineers, under the command of the Commander Royal Engineers (Colonel Hanson),9 were organised into three field companies and a field park company with heavy equipment. The units of the New Zealand Army Service Corps (Brigadier Crump)10 comprised two ammunition companies,

a petrol company, a supply company, two reserve mechanical transport companies, and a tank-transporter company. Three field ambulances, a corps of divisional signals, a divisional workshops, a New Zealand ordnance corps and a divisional provost company completed the establishment.11

Here was potentially a most formidable engine of war, second to no other division in the weight of metal it could throw and the equal in fighting power of any two German divisions then in being. Save in high summer, the sun could rise and set while its four and a half thousand vehicles, carrying more than twenty thousand men, drove past a given point in column of route.12 It was capable of moving fast, of hitting hard while it moved and, as an enemy that forced it to deploy would quickly discover, of hitting harder still when it halted. Its mixed character, neither a purely infantry nor a purely armoured division, fitted it for operations needing adaptability and some measure of independence for, where the terms of battle were at all equal, it possessed within itself the means of breaking into a defensive position, piercing it and exploiting its own success by flooding its armour through the gap. But positional, as distinct from mobile warfare, in which the Division would have to merge its identity into a larger mass, would rob it of these advantages and search out its latent weakness – a shortage of infantry.

(iv)

Without training, the capacities of the Division were potential rather than actual, and training would have to be controlled by its prospective role. Though the date of readiness was changed more than once and proposals to practise outflanking movements by sea were cancelled, Freyberg received guidance from his discussions with Alexander and Montgomery in Sicily early in August, when the employment of the Division as a mobile striking force was agreed upon. Within a few days of the landings in Calabria and at Salerno, Italy was revealed to the Divisional Commander as the destination, and on 24 September he was able to report to the Prime Minister that the deficiencies in the equipment of the Division were being made good – a condition of its committal – and that it would rejoin the Eighth Army.

By this time training was far advanced. Of necessity it had begun at an elementary level within units, rising by way of brigade exercises to divisional manoeuvres. The close, hilly, wooded country

which was expected to await the Division in southern Europe was nowhere to be found in Egypt, and the best choice that could be made, the Gindali region mid-way between Cairo and Suez, offered some experience of hills but none of mud, hard going and thick vegetation. The act of battle can never be faithfully rehearsed but the stage properties at hand in Egypt for the Division’s purpose were more than usually inadequate.

The last of the divisional exercises was carried out at Burg el Arab on the coast west of Alexandria before embarkation. From Maadi, a distance of 100 miles, the entire Division made the longest march on foot in its history – the most gruelling of a series of exertions planned to harden the troops for the rigours of an Italian winter after the languors of an Egyptian summer. In the manoeuvres at Burg el Arab, which culminated in a night attack with live ammunition on 29–30 September, the Division experimented with a technique of its own for forcing a position protected by wire and mines, passing through the armoured brigade and consolidating defensively. An untoward event in an otherwise successful exercise cost the lives of four members of 28 (Maori) Battalion and wounded seven others. Rounds from one gun taking part in the barrage fell short among the advancing infantry of 5 Brigade for a reason which full inquiry failed to establish.

Finally, the safeguarding of health and of secrecy had their place among preparations for the move. The usual precautions against the malaria of the warm season in Italy were ordered before embarkation; and the risk of pestilence during the Italian winter was countered by the issue of warm clothing (two pairs of boots, New Zealand winter underclothing, battle dress and leather jerkins) and bivouac shelters, by inoculation against typhus, and by the provision of mobile laundries and disinfestors. The removal of signs, titles and badges extinguished the most obvious means of identifying the New Zealanders and enforced in the minds of the men the need for security.

A Special Order of the Day signed by the Divisional Commander on 4 October confirmed what rumour had long predicted: the ships lying at anchor in the harbour of Alexandria as they waited for the Division to embark were bound for Italy. This news the troops were forbidden to convey in their letters; and the Division was put on the security list so that its arrival in Italy would not be published. Between 21 and 27 October the censorship was relaxed to allow troops to mention in their letters that they were in Italy; but policy had slumbered, for on the 27th permission was withdrawn. Publication of a despatch written by Freyberg on the same day to the Minister of Defence was delayed for some weeks at the request of

Alexander, and it was not until 23 November that an announcement of the Division’s whereabouts was made in the New Zealand newspapers.

III: Back in Europe

(i)

The main body of troops made the voyage to Taranto in two flights. Each assembled at Ikingi Maryut, near Alexandria, for drafting into ‘ship camps’, between which units were split up so that the loss of a transport should not entail the complete loss of a unit. The first flight of 5827 all ranks (if the records are as reliable as they are precise) sailed on 6 October in the Dunottar Castle and the Reina del Pacifico, reaching Taranto on the 9th; the second, of 8707, on the 18th in five vessels, the Llangibby Castle, Nieuw Holland, Letitia, Aronda and Egra, arriving on the 22nd.

For the soldiers it was a strenuous and uncomfortable mode of travel. As they struggled up the gangways, they were freighted with a blanket roll, winter and summer clothing and personal gear, anti-malaria ointment and tablets, emergency ration, weapon and ammunition, respirator and empty two-gallon water-can, and (between every two men) a bivouac tent. Deposited in the none-too-spacious sleeping quarters, all this impedimenta increased crowding and made men grateful for the fresh air of the open decks and the shortness of the voyage.

Experience in the Dunottar Castle suggests that much of the discomfort and the inconvenience that ensued on arrival could have been avoided had Movement Control applied its rules more flexibly. In the empty holds there was room for vehicles, and these could have been unloaded in the ten or twelve hours of daylight available after arrival at Taranto, which ships aimed to clear before the attacks of night bombers began. As it was, between 14,000 and 15,000 travelled in these seven ships with no more equipment than they could carry on their persons, together with a few cooking utensils, tents, picks and shovels and carpenter’s tools. All the rest of the Division’s mountain of equipment followed at an appreciable interval in its vehicles or as general cargo.

The journey was not only smooth and calm, it was also secure. Over seas still blue in the autumn sun, seas which they had helped to make safe, the men of the Division were escorted in accordance with the promise of Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief of Allied Naval Forces in the theatre, that ‘every care will be taken of our old friends the New Zealand troops on their passage through the Mediterranean’. The first flight had an escort

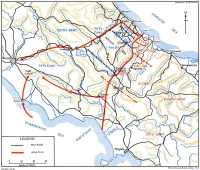

The Italian front on 14 November 1943, showing General Alexander’s plan for breaking the Winter Line

of six destroyers around them and air cover above, and similar protection was given the second.

As the troops of the first flight disembarked on the morning of 9 October, most of them were making their first acquaintance with Europe. The order was to pile heavy gear on the wharves, and then a march of several miles, accompanied by guides lent by 8 Indian Division, to the bivouac area on relatively high ground north of Taranto. Since its arrival ten days before, the divisional advance party, with small means but much help from the Indian division, had worked wonders and no essential arrangements for the reception of the first-flight men had been left unmade. But old soldiers know, and young soldiers soon learn, that the Army rarely excels in welcoming drafts of troops arriving by sea, and that those who step off troopships in far lands often find that the excitement of new scenes is tempered by a deflated sense that something is amiss in the hospitality of the military authorities. The truth is that inconvenience is inseparable from the movement of men en masse. This fact was borne in upon the many New Zealanders who had to spend their first night in Italy sleeping in the open without blankets because there were too few trucks at Taranto to move their gear from the docks to the staging area. By the next night, however, all the bivouac tents had been erected among the olive groves and stone-walled fields – only just in time, for on the 11th the Division experienced its first rainfall since leaving Tunisia nearly five months earlier.

(ii)

The more bracing climate, the stimulus of fresh country and the feeling that the end of the war against Germany was in sight lent zest and exhilaration to these early days in Italy. Leave was taken in Taranto; footballs appeared; and the troops were brought to a pitch of physical fitness by route marches and organised sports. Within the limits set by lack of equipment, training could now be more realistic. It was possible to practise tactics appropriate to close country, movement by night through wooded areas, the employment of snipers, the art of camouflage (no longer against the dun of the desert but against the greens and greys of the Apulian countryside), and the operation of the new portable wireless sets over ground screened by vegetation. The drill of patrolling in this close country and of street and village fighting had also to be mastered. With such ends in view, the infantry carried out section, platoon, company and battalion exercises in the vicinity of the divisional area.

The weather gave fair notice of its inclemency. Frequent showers encouraged units to spend time in constructing tracks and drains

around their camps and the engineers were engaged for some days in roadmaking. The need for drainage was pressed home on the night of 28–29 October, when a heavy thunderstorm in the evening caused widespread local flooding. The drying out or exchanging of soaked blankets and other personal kit occupied much of the next two days. More heavy rain between 5 and 8 November helped to dispel any lingering illusions about the Italian climate. The New Zealanders, indeed, now found themselves ‘with only an exiguous part of the summer left’ but without Caesar’s solace of a retreat to winter quarters.

Meanwhile the Division’s vehicles were following on in the charge of about six thousand men. Camouflaged with disruptive painting and specially prepared for loading, they were divided as equally as possible into four flights in a strict order of priority regulated by the sequence of needs in Italy. They were marshalled in parks at Amiriya for shipment from Alexandria and at Suez, and flights left Suez on 16 and 31 October and Alexandria on 29 October and 3 November. Since at least the first flight of vehicles would be required to move the Division from Taranto, their progress controlled the Division’s immediate future.

It had been expected that the Division would remain at Taranto until at least mid-November for the arrival of all its vehicles, but in mid-October Eighth Army ordered a move forward to a concentration area at Altamura, about 30 miles inland from the port of Bari, for further training in Army reserve. Before the first vehicle convoy reached port to enable the Division to carry out this order, it was superseded by one of 27 October, which directed the Division to the vicinity of Lucera to take up a role in Army reserve protecting the Foggia airfields from the west and guarding against infiltration by the enemy between 5 and 13 Corps.

With the arrival of the first vehicles at Bari on 29 October, it was possible for the leading unit on 1 November to begin the move from Taranto to Lucera along a route marked by the Divisional Provost Company with the familiar diamond signs. For three weeks units steadily moved up to the assembly area among farmlands west of Lucera, most of them breaking the 160-mile journey by staging overnight about 13 miles north-west of Altamura. All this time vehicles were continuing to arrive at Bari in flights, some of which had been split up and delayed en route. The last of them did not arrive until 20 November, one stray transport only appeared on the 28th, and it was the end of the month before the last vehicle was unloaded. By now units were scattered far and wide and drivers in the later transports, setting out from Bari with imperfect instructions, often straggled back to their units in small groups.

The arrival in Italy, therefore, was not a sharp event but a piecemeal process. Nor was deployment much more clearly defined; for as the Division slowly drew up its tail to Lucera, it was ordered to extend its head. On 11 November, before half its fighting strength had reached the concentration area, the Division was ordered up to a concentration area between Furci and Gissi. Eighth Army had changed its plan.

To most New Zealand troops Lucera was thus no more than a stage on the road to the front. The old town stands on the edge of the Tavogliere della Puglia, the Apulian tableland, and it portends the hills; but it derives its chief interest from the past. Here, seven hundred years before, the Emperor Frederick II settled a colony of Saracens to rid his Sicilian kingdom of turbulent subjects and to harry the Pope. Hence Charles of Anjou set out in 1268 on the journey that led to the death of his enemy Conradin, the young grandson of Frederick and the last survivor of the German house of Hohenstaufen.

On 11 November the first elements of the Division, passing through Lucera, turned north towards the German lines.