Chapter 3: Approach to the Sangro

I: The State of the Campaign

THE Eighth Army had come far and fast in the seventy days since its landing in Italy. From the tip of the Calabrian toe to the heights that overlook the Sangro River from the south, the direct distance across sea, plain and mountain measures 300 miles, a figure that would be almost doubled in the itinerary of a mechanised army making an opposed march. But when, on 8 November, British patrols first saw the Sangro flowing towards the Adriatic in the broad, gravelly bed of its lower reaches, the days of rapid advance were over for a season. Aided by the terrain (ahead lay the Abruzzi) and by the weather (snow was reported on the heights on 10 November), a stubborn enemy was preparing to hold the peninsula from sea to sea.

By this time strategic uncertainty had expired, but it had bequeathed a legacy of tactical troubles. The German intentions in Italy remain concealed, and indeed undetermined, until October. For a month the Eighth Army encountered no serious resistance. Progress through Calabria, Lucania and most of Apulia was hindered mainly by demolitions, difficulties of supply and the need to transfer base facilities from the toe to the heel of Italy, where the three ports of Taranto, Brindisi and Bari were quickly occupied after a landing at Taranto on 9 September. Foggia admitted troops of 13 Corps on 27 September and by the middle of October the Eighth Army was disposed along a line Termoli–Campobasso–Vinchiaturo, with 5 Corps in the coastal sector and 13 Corps among the mountains on the left. The last stages of the advance to this line had been sharply contested: hot counter-attack flared up after the landing of commandos and a brigade of 78 Division at Termoli, and the German defenders exacted forfeits from 1 Canadian Division before yielding the important road junction of Vinchiaturo.

From the Fifth Army’s front came corroboration of the enemy’s hardening purpose. The effort to throw the invaders back into the sea at Salerno had failed by the end of the first week, when the Eighth Army’s approach forced the enemy to break his encirclement of the bridgehead and seek safety to the north. With the fall of Naples on 1 October, four days after the capture of Foggia, the

Allies had gained their first chief geographical objectives, the indispensable port and the highly desirable airfields. The Germans withdrew from Naples in order to defend the line of the Volturno River. Here the American 6 Corps and the British 10 Corps effected a crossing only with difficulty, and the month was well advanced before these two corps could feel themselves secure north of the river.

As the allegro of September gave way to the slow movement of October, the Allies for the first time had really to face the implications of their presence in Italy. They could no longer improvise upon the strength of an unopposed advance. The invasion of Italy, as we have seen, was the last of a series of ad hoc decisions on Mediterranean strategy. Geographical objectives had been left an open question. On the day of the Salerno landings Churchill wrote to Roosevelt that, after the fall of Naples, ‘we are, I presume, agreed to march northwards up the Italian peninsula until we come up against the main German positions’.1 On 21 September Alexander set his armies four successive objectives for the winter, the last as far north as Arezzo, Florence and Leghorn. But in fact, lacking a long-term plan when they invaded Italy, the Allies had made insufficient provision for a rapid pursuit which might have hustled the enemy up the length of the peninsula while he was still shaken by the Italian surrender. Irrespective of enemy interference, the Eighth Army in October had to pause because it had outrun its administrative services.

The German intentions were as opportunist as the Allies’. The enemy had been prepared to fall back even as far as the line of the Po and at best had not contemplated a stand farther south than a line across central Italy from Grosseto to Ancona. But as time passed, confidence flowed back into his strategic thinking and gave weight to Kesselring’s plea to hold Rome. Despite the failure at Salerno, he had extricated his forces from the south in good order. The Italian civilians were proving more docile and the Allied soldiers less numerous than he had feared. He was now ready to accept the risk of seaborne outflanking operations – a risk increased by his evacuation of Sardinia and Corsica but diminished, had he known it, by the loss to other theatres of most of the Allied assault craft.

He had much to gain from a southward stand. From the northern plain, pacified with satisfactory ease, he could spare divisions to reinforce the south, where the line was shorter; he could also release armour to the eastern front, where it was urgently needed, in exchange for infantry; he would win time to perfect successive defensive lines; he would buoy up morale by halting a retreat that

had begun at El Alamein; he would preserve Rome as a capital for the Neo-Fascist Republic and deny its airfields to the Allies. These were no chimerical hopes but strictly practical possibilities, for the approaching winter would impede offensive manoeuvre and go far to neutralise the Allied mastery of the air; and, above all, the lie of the land south of Rome offered spectacular advantage to the defender.

From the Gulf of Gaeta to Vasto the peninsula is no more than 85 miles wide and here it happens to raise a barrier of immense natural strength. So long as its western hinge is held firm, the door may be allowed to swing back for some distance in the east, where the seaward slopes of the Apennines undulate in a series of rivers and ridges which can be defended one by one. The western bastion is formed by the Aurunci Mountains, moated to the south by the Garigliano River and falling away inland to the one stretch of flat ground in the whole line. But this stretch, the mouth of the Liri valley, which leads to Rome, is itself closed by the Garigliano and Rapido and commanded by Montecassino on its northern angle. Thence, farther inland, rise mountains of heights and contours that are militarily prohibitive until, within a few miles of the east coast, they descend in the spurs that monotonously confront the army working north. Such was the belt, the Winterstellung, defensible in great depth, upon which the Fuehrer in directives of 4 and 10 October ordered his Italian command to detain the Allies throughout the winter. The significance of the lively enemy reaction at Termoli and on the Volturno lay in showing that the two Allied armies had run against its southern abutments.

By the second half of October the Allied command appreciated the fact. The shortcomings inherent in the strategy of the Italian venture now became apparent. Eleven Allied divisions faced nine German divisions in southern Italy, but reserves in the north raised the German strength to twenty-five divisions. The Allied build-up was going slowly and was doubly burdened by the order to return seven experienced divisions to the United Kingdom for OVERLORD by the end of November and by the decision, which consumed a great deal of shipping space, to transfer strategic bombers to the Foggia airfields. Alexander dared not rule out the possibility of a German counter-attack, and neither the Foggia airfields nor the port of Naples could be secure until protected in greater depth. And he was operating under the overriding instruction to maintain maximum pressure on the enemy as far away as possible from the eastern and the potential western front. Rome, which was the hub of Italian communications and whose possession meant prestige, was the obvious objective; but, assuming a shortage of landing craft for

an adequate amphibious attack, Alexander concluded that Rome could be won only by ‘a long and costly advance, a slogging match’.

Nevertheless, emboldened perhaps by a knowledge of Churchill’s enthusiasm for ‘amphibious scoops’, he included a seaborne attack in his revised plan for the winter. This plan, given final form in a directive of 8 November, was that the Eighth Army, having secured the high ground north of Pescara after crossing the Trigno, Sangro and Pescara rivers, should swing south-west along the route to Avezzano, whence it might threaten the enemy communications. The Fifth Army, having regrouped after breaking into the western end of the winter position before Cassino, would then take up the initiative in an endeavour to complete the breach in the enemy’s main defences and press on up the Liri valley. When both armies were poised within striking distance of Rome, a seaborne force landed south of the Tiber would make a dash for the Alban Hills.

Meanwhile it was necessary to edge forward through the outlying defences on both fronts to establish a springboard for the major attacks. Though early in November the Fifth Army reached the Garigliano near the sea, on the right its exhausted divisions were halted in pitiless weather among the heights that block the approach to the river, and by the middle of the month Clark had to order a pause, with his army still only on the fringe of the main defences.

The Eighth Army, which was to deliver the first blow for Rome, was able to close up more quickly to the eastern flank of the Winterstellung. The first formidable natural outwork was the River Trigno and the hills behind it. The right-hand division of 5 Corps won a foothold north of the river on the night of 22–23 October but heavy rain delayed the attack on the high ground beyond until the early morning of 3 November. By the 5th both divisions of the corps had confirmed their hold on the ridges over the river, and in four days an advance of 20 miles brought the vanguard of the army to the south bank of the Sangro near the mouth. The army now stood with its right wing advanced, resting on the mouth of the Sangro, and its centre and left echeloned back in a line running almost north and south as far inland as Isernia. Of the two divisions of 5 Corps, the 78th was on the right in the coastal sector and on the left 8 Indian Division was still probing forward among the hills south of the river. Further south in mountainous country, 13 Corps had 1 Canadian Division on its right and 5 Division, which had occupied Isernia, in contact with the right flank of the Fifth Army.

As he manoeuvred the Eighth Army towards the Sangro, Montgomery planned to rush the defences and appear on the lateral

road from Pescara to Avezzano before the weather broke and the enemy could reinforce the winter line, still lightly held. Of three possible routes, he chose the coastal road to Pescara, though it was the least direct and the most heavily defended, because it alone could support a thrust in strength and because it afforded better opportunities for air and naval bombardment. His four infantry divisions, now tired and weakened by casualties, were unequal, in his judgment, to breaking the winter line unaided.

II: The Division Moves Up

(i)

It was in these circumstances that Montgomery ordered 2 New Zealand Division forward to concentrate in an area between Furci and Gissi. Relinquishing its sector to the New Zealanders, 8 Indian Division would sidestep to the right so as to concentrate 5 Corps more powerfully for the main drive in the coastal area. For the time being, however, 19 Indian Brigade would mask the advent of a fresh division by continuing to hold the New Zealand sector. As another phase of an elaborate plan to deceive the enemy as to the direction of the impending attack, the Division was forbidden to open wireless communication, the tanks of 4 Armoured Brigade were to be camouflaged in the forward areas and, where possible, units were to move up by night.

These orders found the Division widely dispersed, with some units at Lucera and others still at Taranto awaiting the arrival of their vehicles. The later units, on their way to the front, staged at Lucera to collect the stores they had grounded before leaving Egypt. Every day between 11 and 22 November units left the staging camp for the forward area, travelling by way of Serracapriola and Termoli over roads that made movement strictly an operation of war. The discipline of mechanised march was put to the test not by the enemy but by steep gradients, dangerously winding routes, narrow verges (or none at all) on which to pull vehicles off the road, and improvised detours where bridges had been destroyed and where now lines of traffic, in mutual frustration, bunched in slow knots which convoy leaders and military police, shouting above reverberant engines, strove to unravel. The roads and deviations were most troublesome to the tanks, and eventually they had to be routed separately by way of minor roads as far as possible. Even so, they slithered across greasy surfaces into ditches and straggled in to their destination of Furci singly or in casual groups.

Nearer the front traffic control became even more difficult, notably at a deviation and ford over the River Osento, about three miles

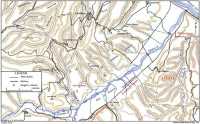

The Sangro front, November 1943

east of Atessa on the Division’s main axis. Here, on the afternoon of 18 November, 6 Brigade arrived to complicate an existing blockage and for a while movement came to a standstill; it was twelve hours before the brigade got clear of the crossing. The next day at the same spot the passage of divisional artillery was slowed up by interloping units, moving the provosts to despair of speeding the traffic through ‘short of giving them wings’. On the 17th (to cite a final illustration of the vexations of travel), as a result of congestion and demolitions on both sides of Casalanguida, 4 Field Regiment took eight hours to move seven miles to a new gun position.

Such delays elicited special instructions on road discipline from Divisional Headquarters, including an order permitting the use of trucks on the roads only on essential business. Off the roads, trucks were of limited utility on any business, essential or incidental, for they would sink with spinning wheels into the mud of the fields. Since gun positions were hard to find, the artillery was given priority in occupying bivouac areas. As he struggled across miry hillsides or along choked roads, many an old soldier must have spared a wistful thought for the dry footholds and the vast vacuities of the desert.

The leaders in this unavoidably ragged deployment were Divisional Headquarters, which established itself on 14 November south of Gissi. Support of 19 Indian Brigade was an important motive, and high up in the order of arrival were 2 Divisional Cavalry Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Bonifant)2, 4 and 5 Field Regiments (Lieutenant-Colonels Philp3 and Thornton4 respectively), batteries of 14 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Kensington)5 and units of the engineers and of the medical corps. Close behind came 4 Armoured Brigade, and among the last arrivals were the two brigades of infantry.

At 10 a.m. on 14 November, when most units were still far to the rear, the Division assumed responsibility for its sector between 5 Corps and 13 Corps, with command of 19 Indian Brigade and 3 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. In this hilly country, veined with

numerous streams and watercourses but with few and tortuous roads, the enemy was able to take his time in retiring upon his winter defences behind the Sangro. The line was fluid and ill-defined but conformed roughly to the trend of the river which, in this region, flows north until its junction with the Aventino, where it bends to the north-east in its final fall to the sea. Nineteenth Indian Brigade was pressing outward with patrols north and north-west of the village of Atessa and westward to Tornareccio. On the right 78 Division, which had patrols across the river near the coast, extended its line to the area of Monte Calvo, but there was no contact on the left with 1 Canadian Division, reported at Agnone, and the protection of this flank was confided to the Divisional Cavalry Regiment.

The enemy on this front was not then impressive. The sector from the coast to the confluence of the Sangro and Aventino rivers, in which the Eighth Army was assembling three divisions, was held, though precariously as the event was to show, by 65 Infantry Division, an unseasoned and ill-equipped formation of mixed nationalities, which had recently been brought down from the north. On its right, south of the Aventino, was the stronger and completely mechanised 16 Panzer Division, with fifteen to twenty Mark IV tanks and twenty self-propelled guns in addition to the normal field artillery and two regiments of lorried infantry.

(ii)

The million small deeds by which a military formation moves and has its being are like the separate strokes of the painter’s brush, which compose themselves into intelligible purpose and design only when observed from a distance as parts of a total picture. The little strokes of effort that were applied in the first fortnight of the Division’s fighting in Italy arrange themselves into a picture of preparation for the crossing of the Sangro in strength. Four preliminary tasks had to be completed. The enemy had to be evicted from the area south and east of the river; the high ground in the angle formed by the junction of the Sangro and the Aventino, commanding the stretch of river across which the attack was to be launched, had to be cleared; the river itself and the enemy territory immediately beyond it had to be reconnoitred for the most convenient fords and bridge sites, for minefields and strongpoints; and the roads and tracks leading to the river had to be cleared of mines, repaired, maintained and even, occasionally, built.

The timetable for the discharge of these tasks lay at the mercy of the weather, inland because a downpour among the mountains would cause the river to rise with disconcerting rapidity and locally

because muddy roads and sodden ground almost immobilised the armour and made the movement of supporting arms chancy and unreliable. The weather was already breaking when the first elements of the Division moved into the line, with snow on the peaks and widespread rain and mist, and the original plan for rolling up the eastern flank of the winter position before winter came had to be postponed and finally conceived afresh. It was a time, in the old parlance of the horse gunner, of ‘rugs on, rugs off’. As the scowling skies opened and the rivers rose in flood, the hopes faded of a stolen march, of a comparatively dry-shod dash by tanks to the lateral road from Pescara to Rome. Expectations had to be revised, objectives shortened and methods made more deliberate.

By 20 November the enemy opposite the New Zealanders was back across the river and patrolling across it was in full swing; by the 25th the menacing ‘hump’ between the rivers on the Division’s left was occupied by the Indian brigade and the two New Zealand infantry brigades were in the line; and on the night of 27–28 November the weather had so far relented as to permit a crossing of the river by the two New Zealand brigades and then, with all the meditated force and fraud of a battle by the book, a drive up the slope into the bony knuckles of the Sangro ridge, where the Germans proposed to spend the winter. By 3 December the Germans had abandoned this ridge and that morning a company of New Zealand infantry made a brief incursion into the town of Orsogna, which the enemy had hurriedly adopted as a fortress. Such are the events which will engage our attention in this chapter and in the next.

III: The First Contacts

(i)

It fell to the artillery to receive and deliver the first blows of the Division in Italy. The 28th Battery of 5 Field Regiment opened fire in support of the Indian brigade on the afternoon of 14 November and a few men of a sister battery, the 27th, deploying the same afternoon, were slightly wounded by shellfire. Fourth Field Regiment, like the 5th, was allotted a gun area north of Casalanguida, and on the 15th 14 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment sited guns at the crossing of the Sinello and Osento rivers and in the country between, though for several days they had no employment. The fluidity of the front was demonstrated by the orders to a troop of B Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment to patrol the roads south of the New Zealand area as far as Castiglione Messer Marino, over ten miles from the left flank, in the hope of meeting the Canadians; and further by the attack of an enemy patrol during

the night of 14–15 November on the bridge over the Sinello on the Division’s main axis. This bridge was the only one in the area left unblown by the enemy in his retreat – an oversight which he tried to rectify not only by gunfire but also by infiltrating demolition parties, so that A Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment had to be detailed to guard it.

As units assembled in the forward area over roads roughened by a growing congestion of traffic and by intermittent rain, the Indian brigade’s infantry was edging towards the river with New Zealand support. On the evening of 15 November the guns of 5 Field Regiment by two prearranged bombardments helped the 6/13 Royal Frontier Force Rifles to a quiet occupation of the hilltop hamlet of San Marco. The 16th Panzer Division, however, was still in possession of Tornareccio, Archi and Perano, which lay on a road running along the crest of a ridge to the Sangro, parallel with and west of the Division’s axis. To release it for a further advance, 1/5 Essex Regiment was relieved on 18 November from the task of protecting from the west the all-important road from Casalanguida to Atessa by B Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment and then, after a few hours, by the vanguard of 4 Armoured Brigade – 22 Motor Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell.6 The Indians had by now seized hills north and north-west of Atessa overlooking the Sangro and conveniently placed for attacks on Perano and Archi.

(ii)

At short notice on the 18th an afternoon attack on Perano by tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel McGaffin)7 and infantry of 3/8 Punjab Regiment was ordered. Success would curtail serious resistance south of the river by compelling the enemy to blow the Sangro bridge behind the village after withdrawing his heavy equipment. Since Perano was only a German outpost and was believed to be undefended by anti-tank guns, the infantry was to be preceded by the tanks, consisting of four troops under the command of Major Everist8 – A Squadron plus one troop of C Squadron. The remaining three troops of C Squadron by direct fire were to thicken up the artillery support provided by the British and the two New Zealand field regiments – smoke for twenty minutes to blind,

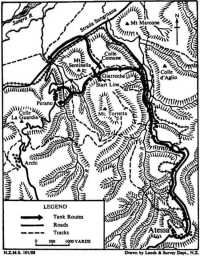

19 Regiment’s Attack on Perano, 18 November 1943

followed by high explosive for an hour to neutralise, the enemy in Perano.

Hastily called up from Atessa, the assaulting tanks formed up on the saddle between Monte Torretta and Monte Sentinella, two hills forming a ridge running roughly north and south and parallel with the more westerly ridge crowned by the roadside houses of Perano. Hence, at 3.30, while the smoke canisters of air-bursting shells bounced on the slopes east of the objective, trailing white streamers of smoke through the air, the fourteen Shermans, followed

by infantry from the Punjab, advanced to the first tank action ever fought by New Zealanders. The attack was double-pronged. While two troops drove across country to gain the road and enter Perano from the south, the other two, in a small right hook, were directed round behind Monte Sentinella to the riverside road called the Strada Sangritana, from which branches off southward the road winding up the ridge to Perano. The plan was thus to attack the village simultaneously from the south-east and the north.

Perano was a stiff objective, being defended by the panzer troops with greater determination and resources than report had suggested. Continuous shellfire harried the advance. The two right-hand troops of tanks, emerging from behind the lee of Sentinella, one still on the low hills overlooking the Strada Sangritana and the other across the road in thick olive groves, ran into murderous fire at short range, probably from self-propelled guns sited near the turn-off to Perano. At least four tanks were put out of action, seven of their crews killed and five wounded; and among the Indians on foot losses were heavy. The attack on Perano from the northern flank had to be abandoned. The approach from the south and east across country fared better. Here the tanks were troubled chiefly by the terrain. The mile-long route westwards from the start line to the objective was a rough, winding track softened by rain. The tanks had to cross a gully, climb a spur, drop down to ford a stream, and deploy in troops for the actual assault up a steep, wooded hill. Neither these obstacles nor the spite of machine-guns and mortars could prevent four of them from reaching the hilltop. Two tanks of headquarters troop, taking a more northerly route up the hill, were the first into Perano, entering the town from the north at 4.40 in time to see other tanks approach from the south. Half an hour later the Indian infantry arrived and with workmanlike expedition, which the New Zealanders admired, consolidated the capture. The Germans, who had escaped before the arrival of our tanks, held on in a cluster of houses about a thousand yards east of the Sangro bridge, perhaps fearing an attempt to rush it. Later in the evening, after an escaped British prisoner of war had seen five German tanks, two self-propelled guns, and two anti-tank guns retire hurriedly across the bridge, the charge was blown. Before this broader object of their attack had been achieved, the New Zealand tanks had withdrawn from Perano, leaving the Indians in possession.

Success in this action was plucked out of unusual difficulties. The tanks had been on the road for four days previously and the time for preparation was so short that they were not properly stripped for action, nor was much reconnaissance possible; the plan was founded on faulty information about the enemy; the going was

bad; and the control of manoeuvre during the assault was gravely handicapped and the assault probably made more costly by wireless silence and the need to communicate under fire by hand signals. Had the identity of the New Zealanders remained hidden from the enemy, the action would still have published to him the skilful leadership of the opposing commander of tanks and the resourcefulness of crews that were yet novices in armoured warfare. But their identity was in fact revealed by papers belonging to C Squadron found by enemy infantry in one of the knocked-out tanks after our other tanks had withdrawn, though several days elapsed before the Germans confirmed the presence, not merely of a brigade, but of a whole division of New Zealanders.

The Perano fight implied that the end of resistance south and east of the river on the Division’s front was in sight, and it was followed that night by the withdrawal of the enemy’s heavy weapons and transport from Archi, the last enemy observation point south of the river, higher up the same ridge; but there was a last sharp clash there between the Indians and an enemy rearguard consisting of a company of infantry and a platoon of engineers with orders to hold the town as long as possible. The Indian attack on 19 November was to have been supported by a troop of New Zealand tanks with direct fire, but the fire plan had to be abandoned early because of thick mist. The Indians spent a day and a night in hard and confused fighting in Archi before the Germans retired, the last enemy troops in the sector to fight with their backs to the river.

On the right, the hills sloping down into the Sangro valley were found clear on the 18th, and on the 20th the Divisional Cavalry Regiment assumed responsibility for this flank; in the centre the Indians dominated the riverbank on either side of the blown bridge and patrolled across the river; and on the left a patrol of 22 Battalion, entering Tornareccio on the morning of the 19th, found mines and booby traps laid by departing Germans a few hours before. Finally, far to the south at the very extremity of the Division’s responsibilities, the troop of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment sent to Castiglione to make contact with the Canadians found them at Agnone.

(iii)

It was now possible to close up to the Sangro line for the attack, which was still scheduled for the night of 20–21 November. As part of the general forward movement, 36 Survey Battery posted its flash-spotters and sound-rangers on an arc of vantage points overlooking the river valley, the better to locate by sight and sound the guns of the enemy, and all three New Zealand field regiments, including for the first time in Italy the 6th (Lieutenant-Colonel

Walter),9 deployed along the bed of the Appello, a tributary stream of the Sangro.

New Zealand infantry now appeared in the line, 6 Brigade coming forward to occupy the right-hand half of the Indian brigade’s sector, between the round hill of Monte Marcone on the right and the river junction on the left – the front upon which the Division’s assault on the winter position was to be made. The brigade was ordered to put standing patrols on the south bank of the river and to send patrols across on the night of 19–20 November. A ten-mile march on foot, broken by lying up from dawn to dusk on the 19th north of Atessa, was a tiring preliminary, especially for the support platoons carrying 3-inch mortars and machine guns. Before midnight the battalions were in position along the line of the Strada Sangritana, occupying a front of less than a mile between the Appello and Pianello streams, with 26 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Fountaine)10 on the right, the 25th (Lieutenant-Colonel Morten)11 in the centre, and the 24th (Lieutenant-Colonel Conolly)12 on the left and with forward companies on the road. Drenching rain sent the troops to the shelter of buildings and even of the bivouac tents so much regretted during the embarkation at Alexandria.

When the new day lighted up the scene, it revealed to the men of 6 Brigade a landscape not wholly strange to New Zealand eyes. From their posts at the foot of the hills on its southern edge, the floor of the valley extended before them for nearly two miles – first, for almost half the distance, a heavily cultivated alluvial plainland (the Piani di Piazzano), then three or four hundred yards of riverbed, and finally a narrow flat of marshy land cut by irrigation ditches. The valley ends in an escarpment, and the gaze of our men fell upon two conspicuous grey bluffs, rising abruptly thirty or forty feet. Behind them a country of olive groves and cream-coloured farmhouses, threaded by winding roads and lanes, climbs brokenly 1200 feet to the skyline five or six miles distant – the Sangro ridge, where lay the tough core of the German defences. For most of the year a pretty enough rural scene for traveller or contadino, in winter it bears to the eye of the assaulting soldier a more forbidding aspect. The upward slope from the river valley is, indeed, of no homeric grandeur. The grandeur of this region belongs to the bare, rocky bulk of the Montagna della Majella, a brooding omnipresence

against the skyline, behind which the sun slides in late afternoon. Compared with this 9000-foot eminence, the Sangro slope appears almost gentle; but as a military obstacle it is, conservatively speaking, troublesome.

The Sangro itself, running in several channels between banks of gravel and water-worn boulders, reminded some of our men of the rivers that flow eastwards from the Southern Alps across the Canterbury Plains. Knee-deep in dry weather, as it was when 78 Division arrived on its southern bank, this baffling river may rise five or six feet in a day after autumn rain and fill the whole riverbed with a flood swirling along at 25 knots. So sudden and incalculable are these changes of mood that a patrol which has waded across with ease may find its return barred by a current too swift to be breasted by the strongest swimmer. Though the stony bed of the river is firm enough to support an improvised roadway, the approaches to it lie across soft, friable soil which is apt to crumble under the weight of motor vehicles. This was the capricious stream that New Zealand infantry patrols were to explore in the coming week, while the attack was deferred, modified and finally recast.

(iv)

Infantry patrols are primarily the antennae of an army, feeling sensitively forward to flash signals, sometimes of danger, sometimes of opportunity, to the brain; but they serve purposes other than short-range reconnaissance. They may enable a force to grasp and hold the moral and material mastery of no-man’s-land; they may be used to keep alive the aggressive spirit, which stagnates so easily in a war of static emplacement; they may, by swift and silent apparition, inflict casualties on the enemy, unnerve him, tire him by the need for vigilance, derange his projects or destroy dumps and installations; they may be employed to mislead him as to the direction of an imminent thrust or to force him to broaden his front; they may protect other troops on specialised missions in areas exposed or disputed; and those patrols also serve that only stand and wait, observing by eye and ear and ready to counter the patrols of the other side. Many of these aims were exemplified in the patrolling of the Division between the night of 19–20 November, when 6 Brigade moved into the line, and the night of 27–28 November, when the Sangro was crossed and the heights behind it assaulted.

In addition to the standing patrols, the Division sent out during this period forty-four patrols, ranging in strength from two men to a platoon, all but two of them by night. Of this number twenty-six succeeded in crossing the river, five made no attempt to cross, and thirteen tried but failed. Few failed for want of grit and determination:

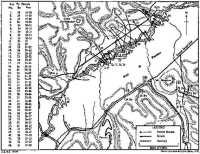

New Zealand patrols on the Sangro, November 1943

one patrol tried at eight different places before returning cold, wet and frustrated; the officer leading another struggled alone to an island in mid-river, only to see movement on the northern bank that compelled him to rejoin his men on the southern; a third patrol crossed two streams but was foiled in four attempts on the northernmost channel, losing for a few hours one man whom the current swept over to the German side. On different nights the water varied in level from knee- to neck-high, but all the patrols that made the crossing found it necessary to link hands for mutual support, stretching out like the impatient souls in the vestibule of Virgil’s hell ‘with longing for the farther shore’. Some floundered under the weight of soaking equipment in the quagmire of irrigation ditches north of the river. Only a quarter of the patrols located any enemy by sight or sound, and of this eleven no more than four exchanged fire. The casualties of eight days of patrolling were 13 – five killed, six wounded and two taken prisoner; but six of these casualties occurred in a minefield south of the river and another six in the only two daylight patrols. That is to say, from the twenty-four patrols that prowled the northern bank by night, all members returned unharmed except one wounded officer.

As soon as 6 Brigade was in position on the night of 19–20 November, 26 Battalion established a standing patrol on the riverbank

and other battalions followed this example, so that finally there were five such permanently manned posts. The tasks of their occupants, who were relieved at least daily, were to observe movement and locate positions across the river, prevent German patrols from crossing, report on the state of the river and provide starting points for reconnaissance and fighting patrols crossing to the northern bank. Nor was there any delay in setting mobile patrols to work. On the night of their arrival, 24 and 26 Battalions each sent out two. Those of 24 Battalion were the first New Zealanders to cross the river; they found the water three or four feet deep and reported the lateral road on the north bank to be in fair condition. Since the attack was due to begin within twenty-four hours, the 26 Battalion patrols reconnoitred approaches to the south bank and a patrol from 25 Battalion gave cover to engineers of 6 Field Company sweeping for mines on the Piazzano plainland.

When the weather forced the Army Commander to postpone the offensive, he ordered vigorous patrolling in the New Zealand sector to increase pressure on the enemy while 5 Corps, on the right, expanded its existing bridgehead across the river to accommodate the substantial strength needed to launch a more deliberate operation. The risk of sacrificing surprise was accepted. As if in pursuance of this policy, patrolling on the night of 20–21 November was eventful. One party from B Company 25 Battalion climbed the northern cliffs and penetrated to a group of buildings a mile beyond the river, where Germans were located. A fighting patrol from 24 Battalion disturbed two enemy parties laying mines across the river and fired on them from the southern bank, and a second fighting patrol had a brush with an enemy outpost on a steep knoll north of the confluence, inflicting casualties. The officer in command himself returned wounded at 6.45 next morning, having been out nearly twelve hours. On the same night of 20–21 November a patrol from A Company 24 Battalion, while protecting engineers clearing mines from our side of the river, lost three men killed and three wounded in a minefield.

On the next day, the 21st, patrols were despatched for the first and last time by day. Whether or not under the eyes of the enemy, they crossed unmolested but ran into enemy positions and had to fight their way out. Of the six members of the patrol from D Company 26 Battalion, only one was unscathed. One was killed, two were captured and two were wounded, including the leader (Second-Lieutenant Lawrence),13 who, having cut a stick for support, made his way back to the northern bank, whence he was brought

back across the river on the 22nd by the battalion’s standing patrol. The other patrol, supplied by 24 Battalion, comprised three men from A Company, of whom the leader was killed. As a result of these heavy penalties, Freyberg forbade the crossing of the Sangro by day.

The level of the river steadily rose and patrols on the three following nights encountered increasing hazards, until on the night of 23–24 November Sangro’s pomp of waters was unwithstood; two patrols turned back from a current which in places foamed neck-high and swept men off their feet. Though the standing patrols reported a drop of a foot in the river level on the 24th, only one of three fighting patrols that night – 18 men from C Company 26 Battalion – reached the far side. There they searched two houses and drew fire from a third. A three-man reconnaissance patrol farther upstream battled for three hours before getting across.

The Sangro appeared to be at its most obstructive on the night of 25–26 November. It proved too much for each of six parties, including three from 21 and 23 Battalions of 5 Brigade, which had now come in on the right of 6 Brigade. The speed of the current made it impossible to stand in water up to the hips, and it became clear that ropes would be needed for a full-scale crossing. The only passage of the river that night was made by Major Bailey,14 accompanied by two men of D Company 21 Battalion.

Fine weather was followed by a fall in the river and by redoubled activity after dark on the 26th. Every battalion sent out patrols to test crossings and routes up the cliffs, and in all nine parties visited the northern bank, some of them probing deeply. Second-Lieutenant McGregor15 and a companion from C Company 21 Battalion, exploring for about ten hours, made a wide circuit between two hills where they found buildings occupied by Germans, and another far-ranging patrol from B Company, led by Second-Lieutenant Swainson,16 discovered barbed wire and a trip-wire along the top of the cliffs farther east. Of three reconnaissance patrols sent out by 6 Brigade, that of 26 Battalion was guided by an Italian civilian to a shallow ford. The same battalion provided an escort while Second-Lieutenant Farnell17 and men from 8 Field Company reconnoitred a route from the proposed Bailey bridge site to the lateral road north of the river.

By now the patrols had done their work. By exerting pressure on the enemy, they had indirectly helped 5 Corps to gather a strong

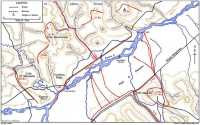

The Crossing of the Sangro, 27–28 November 1943

force in an extensive bridgehead across the river; they had found suitable fords, mineswept approaches and forming-up places and bridge sites; they had shown the need for ropes to assist the infantry to cross, the impassability of the river to wheeled vehicles, and the probability that even tracked vehicles would come to grief on the banks leading down to the water; they had made known that the northern bluffs, though steep and slippery, could be climbed by resolute troops; they had revealed that the enemy was holding the foothills near the river in no great strength; and they had leavened the assaulting battalions with officers and men who knew something of the wiles of the Sangro and had roamed its northern banks.

(v)

Early planning had provided for the capture of the hilly ground in the angle of the Aventino and Sangro rivers as an essential part of the major offensive, since a force occupying this ground would enfilade troops crossing in the reach below the river junction. The Divisional Commander seized on the delay imposed by the weather to order the Indian brigade to carry out this preparatory task, involving the capture of the two hilltop villages of Sant’ Angelo and Altino and a feature called Il Calvario.

When, after crossing the river, the 1/5 Essex Regiment and the 3/8 Punjab Regiment closed in for the assault at 4.15 on the morning of 23 November, they were supported by the fire of the three New Zealand field regiments and 3 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. Under this cover the Essex battalion reached the top of the Sant’ Angelo spur and occupied the village in the early afternoon; but it was only two companies strong, the rest of the battalion having been prevented from crossing in the dark by a sudden rise in the river, and thereafter by enemy fire which pinned them to the ground south of the river. On the left, the Punjabis, having crossed by a ropeway bridge, were established on Il Calvario by 7.30, but the bridge by this time had been washed away. Without hope, therefore, of immediate reinforcements or supplies, the two battalions faced vigorous counter-attacks by troops of 16 Panzer Division and of 1 Parachute Division, who were carrying out a relief at the time. The Indians had to give up Il Calvario in the early afternoon, when it appears to have become untenable by either side after having changed hands three times, and they were pressed into a narrow bridgehead against the river. That night men trying to swim the flooded river were drowned; some New Zealand engineers attempted but failed to replace the rope bridge and others were equally unlucky with a folding boat. Eventually, the next night supplies were

sent over by an improvised way across the ruined road bridge, which 5 Field Park Company made passable by lashing ladders to the broken masonry.

Persistence was rewarded, for on the night of 23–24 November the Germans withdrew across the Rio Secco, a small tributary of the Aventino, towards Casoli; and on the 25th all objectives were firmly in the hands of the Indian brigade. This success was won against miserable weather, a swollen river, steep country and a tenacious and well-sited enemy; and it ensured that the New Zealanders would begin their attack (to borrow a phrase from a different context) with ‘no enemies on the left’.

(vi)

The movement of a mechanised army against mechanically contrived obstructions throws a heavy burden on its engineers, and on the Sangro in these days of deepening winter it was very much an engineers’ war. Everyone respects a sapper, for the sapper is everyone’s friend, a succouring ubiquity, clearing a track through minefields for the infantryman, tidying up after tanks, passing an accurate orientation to surveyors of the artillery, running a railway, building a bridge, patching a road for supply units or dragging the erring driver from the ditch of his choice. Whether operating a theodolite or a shovel, a bulldozer or a mine detector, the engineer needs most of the soldierly qualities in generous measure – coolness under fire, high technical skill, industry, cheerfulness and infinite patience to do again what has been undone by the force of nature, the malevolence of the enemy, or even the negligence of his own troops. In the fortnight before the attack the engineers of the Division found full employment upon roads, minesweeping and bridge-building.

The repair and maintenance of roads in the Division’s area was a continuous labour. The surfaces were damaged at the outset by demolitions and shell holes and then by streaming rain and incessant traffic, which churned wet roads into mud and scarred them with deep ruts, especially at the many bends; heavy steel-shod tanks were harsh abrasives, and under their weight and that of ditched trucks the edges crumbled. At all times working parties had to stand by with pick and shovel to make minor repairs on the spot. Though men from other units not engaged in operations shared in this work and civilian labour was recruited from the villages, most of it fell to the engineers. Attention was given first to the supply road in the rear of the Division’s sector, but when the last of the three field companies arrived on 19 November it was possible to set both 6 Field Company

and 8 Field Company to work in the Sangro valley, with 7 Field Company (between Gissi and Atessa) occasionally sending parties to help the forward companies.

It was at detours where the Germans had demolished bridges and culverts that road maintenance was most arduous. The deviations were made by bulldozers, but thereafter (since bulldozers were much in demand) they had to be kept in order mainly by manual toil. So long as they remained unbridged on the Division’s routes work on them was never finished. Often steep, uneven and soft, they were danger spots where a single mismanaged truck might halt the flow of traffic, and they were always capable of improvement by levelling, widening, metalling and the filling-in of ruts. The detour over the Osento stream, where so much delay occurred, continued to occupy large parties of sappers until 23 November, when 7 Field Company built a 150-foot Bailey bridge over it. The demolition of the bridge over the Pianello stream on the Strada Sangritana, being in full view of the enemy, had to be worked on by night but the noise of the bulldozers infallibly brought down gunfire, so that the only protection afforded by the darkness arose from the circumstance that predicted shooting is commonly less accurate than observed. All such work done on the Strada Sangritana incurred the hostile interest of German gunners.

Roads and tracks had to be made as well as maintained. Sites for bridges across the Sangro were selected after reconnaissance on the night of 20–21 November; one was rather less than a mile downstream of the confluence and the other was a mile and a half farther to the right. Both lay at the end of existing tracks across the Piazzano; but the tracks had to be almost totally reconstructed to bear heavy traffic. The task progressed slowly night by night, often in pitch darkness and in stinging rain squalls that blinded the drivers bringing up equipment and made their journeys a nightmare of anxiety. Engineers cut logs to provide corduroy for laying on the tracks and every night repair materials were brought up to a dump on the Strada Sangritana. So the work went on. When the time came to attack, the left-hand route was still no more than an assault track, but on the right there was a firm, wide road, fit for use in almost all weathers.

To make movement not only possible but safe from mines was another aim of the sappers. From 18 November until the eve of the offensive, they swept the road from Atessa to the Strada Sangritana, the Strada Sangritana itself, the tracks across the Piazzano, the Perano–Archi road and the north bank of the river, as well as removing unexploded charges from several bridges and culverts – work done sometimes by day under fire.

The standard Bailey bridging equipment for a single division proved woefully insufficient for the needs of the divisional engineers, and by steady increments they finally accumulated five complete sets. With this material they built six bridges between the 21st and 27th, one over the Osento and the other five over demolitions along the Strada Sangritana. This bulky bridging material was brought into the Division’s area by the spacious floats of 18 Tank Transporter Company and thence moved to the sites by 5 Field Park Company. This latter company was the custodian of the engineers’ heavy equipment – the bulldozers which moved lesser mountains in filling craters and pushing through detours, the recovery vehicles, and the mechanical shovels which dug the shingle for roads.

No part of the Division was more dependent upon the roadmaking of the engineers than the Army Service Corps. To sustain the flow of supplies to the field maintenance centre south of Gissi, whence the fighting units drew rations, ammunition and petrol, was no trivial or easy assignment. Drivers using a supply line that stretched back as far as Altamura and San Severo found the way long and rough; the weather was foul and many vehicles were late in arriving from Egypt; but no one went short of essentials. For the coming attack ammunition companies began on the 15th a dumping programme which had made available 700 rounds of 25-pounder ammunition for each gun within a week – 500 on gun positions and 200 in dumps. Between 22 and 30 November the Division handled 795 rounds a gun, a total of more than 76,000.

For the first time since May in Tunisia, the New Zealanders were disposed as a division in the field. In a posture of attack, they awaited only the word to go forward.