Chapter 4: The Crossing of the Sangro

I: Over The River and Up The Hill

(i)

WHILE all these preparations were advancing, the weather was making a mock of tactical planning. The Division was collecting its strength to strike a blow, but when would the blow be struck and what was to be its nature?

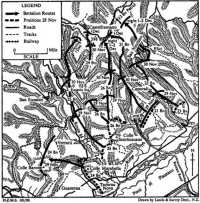

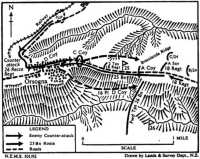

Proposed when the weather was dry, the river low and the German defences lightly held, the bold armoured dash by the Eighth Army for the Pescara–Chieti lateral was to begin on the night of 20–21 November. Simultaneously with 5 Corps on the right, the New Zealanders were to attack across the Sangro with 6 Brigade, which was ordered to capture heights north of the river and astride the axis road. At the same time the Indian brigade would seize the dominating ground between the two rivers on the left. It was intended that the tanks of 4 Armoured Brigade should exploit success.

Having issued these orders on the morning of the 20th, Main Divisional Headquarters moved forward to a position east of Atessa. Rain that day and a rise in the river forced a postponement of forty-eight hours on both 5 Corps and the Division. Fresh instructions from the Army Commander on the 22nd imposed a second delay until early on the morning of the 24th, but during the 23rd the Sangro was in spate – and the deluge bore with it a new tactical conception.

The frisk to Pescara by the armour gave way to a more methodical, step-by-step operation, making opportunist use (in the words of Lieutenant-General C. W. Allfrey of 5 Corps) of ‘whatever clubs were in the bag’. For the Division this meant the cancellation of 6 Brigade’s attack in its old form and a pause for adjustment while the initiative was retained by intensified patrolling and the bombing of the towns of Lanciano, Castelfrentano and Casoli, and of German gun positions. In place of a stealthy advance by a single infantry brigade, followed by deep armoured exploitation, it was now necessary to plan a more massive and deliberate opening assault, powerfully protected by gunfire and designed to control the five

miles of main road running north to the lateral road from Castelfrentano to Guardiagrele.

One of the first requirements of the new plan was to bring 5 Brigade into the line. The brigade moved into its sector on the right of the Appello stream in two stages. On the night of the 24th, 21 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel McElroy)1 occupied the high ground south of the Strada Sangritana, with the right-hand company on the forward slopes of Colle Sant’ Angelo and the others on and behind Monte Marcone. Standing patrols were at once posted on the riverbank. The next night 23 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Romans)2 came in on the left, establishing itself on the reverse slopes of Monte Marcone. With the return of Kippenberger, who resumed command from Stewart,3 the early completion of the signals layout and the sending out of patrols, the brigade quickly settled down to prepare for the attack that was now only hours away.

(ii)

The new orders for the crossing of the Sangro on the night of 27–28 November, issued by the Divisional Commander on the afternoon of the 26th, appeared in more favourable circumstances than the earlier. Two days of fine weather had caused the river level to fall and on the 26th all three bridges of 5 Corps were again in use. The ground was hardening. The sky was open to Allied aircraft. They flew four hundred sorties on the 26th and 483 on the 27th, the vast majority on 5 Corps’ front. Opposite the Division, however, attacks by medium bombers and fighter-bombers on German gun areas reduced hostile shelling which of late had been vexing. Of the enemy aircraft that appeared over the sector on both of these days, one engaged in photographic reconnaissance paid the penalty. Shot down into the bed of the Sangro early in the afternoon of the 26th, its crew was taken prisoner by a standing patrol of 21 Battalion.

During these two days mild aggressive flourishes were made on both flanks of the divisional sector. On the left, between the two rivers, the Indian brigade occupied Altino without meeting resistance and pushed patrols forward to Casoli. On the right, two 17-pounders of Q Troop, 7 Anti-Tank Regiment, from exposed positions on the flat west of Monte Marcone, fired 130 rounds of solid shot across the river at farm buildings suspected of housing Germans who

might hold up our assaulting infantry. They caused minor damage to the buildings and gave two escaped prisoners of war, who came running towards the guns, an urgent motive for rejoining the Allies.

Among other preparations for the attack were the establishment of a Tactical Divisional Headquarters in the now populous area behind Monte Marcone, the final disposition of the machine-gun companies between the two infantry brigades, and the setting up of advanced dressing stations. When darkness fell on the 27th, the Division roused itself like a giant going on night shift and made busy on tasks that had had to wait until the last moment. Brigade signallers laid telephone lines and transported wireless sets to the proposed bridge sites, and parties of infantry, wading unmolested through the river at the chosen places, stretched ropes across to the farther side to guide and support their battalions.

The Division was to strike simultaneously with 5 Corps, which was ordered to advance from its already considerable bridgehead - the plainland lay north of the Sangro in its sector – to seize the villages of Fossacesia, Mozzagrogna and Santa Maria, nestling in the hills about three miles beyond the river. Unlike 5 Corps, the New Zealanders had a double assignment – first to establish themselves in strength across the river and then to exploit north and west, as far as possible step by step with 5 Corps, to force an entry into the glacis of the enemy’s winter position, preparatory to breaking through the position itself. The first task, it was anticipated, could be carried out silently without enemy interference, and Freyberg’s orders appointed as the infantry start line the lateral road north of the Sangro and, on the left for a few hundred yards, the south bank of the river.

The essence of the plan was a break-in of the infantry, preceded and protected by heavy artillery bombardment and followed by tanks ready to repel counter-attack. Advancing at the rate of 100 yards in five minutes, each of the two infantry brigades was set successive groups of objectives. Fifth Brigade was to take first Point 208, a round hill on the right, and a mile away to the south-west across a valley, Point 217, steep towards the summit; and, second, two heights a mile or so forward of Point 217 on the same feature. The objectives of 6 Brigade were arranged in three stages – first, heights on the lower slopes of Colle Scorticacane, about a thousand yards beyond the river, and the ground enclosed by the river, Route 84 and the lateral road, including an area known as Taverna Nova; then three points on or near the crest of Scorticacane and Colle Marabella overlooking Route 84; and finally Point 217, which lay forward along the Scorticacane ridge. Thence the brigade was to exploit still farther along the ridge to Point 207 and on the left

from Marabella to Colle Barone, a prominent hill dominating the high ground west of Route 84. It was also to prevent the enemy from destroying bridges across this road and the lateral road. The deepest of the objectives, lying about a mile and a half from the start line, would be reached only after a scramble up the cliffs or up the gullies between them and then an arduous climb in clothing and equipment heavy from the river crossing.

Five battalions were to make the assault. Of 5 Brigade’s objectives, Point 208 was allotted to 23 Battalion and the rest to 21 Battalion; 28 (Maori) Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Fairbrother)4 in reserve, was left rather far back at Atessa. In 6 Brigade, 26 Battalion was directed to the main Scorticacane feature, 25 Battalion to its western slopes, and 24 Battalion to Marabella. The third infantry brigade under New Zealand command, the Indian brigade, while taking no part in the actual advance, was to assist by firing on the enemy west of Route 84 after zero hour.

Weapons of many types and calibres were to supply fire support. One hundred guns – those of the three New Zealand field regiments, 3 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, and a troop of 80 Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery – were to fire 250 rounds each in a bombardment lasting three hours and a half. Timed concentrations, lifting by prearranged stages on to deeper targets, with 15-minute pauses to indicate successive objectives, were aimed to neutralise enemy fire from areas such as those commanding the more obvious routes between the cliffs. The tracer shells of 14 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment were to guide the infantry between their boundary lines on to their objectives. A Squadron 18 Armoured Regiment was to fire its 75-millimetre tank guns. One of the four Vickers machine-gun companies was allocated to 5 Brigade, two to 6 Brigade and the other to the Indian brigade, so that each New Zealand battalion might be accompanied over the river by a machine-gun platoon as well as its 3-inch mortars.

After fording the river on the right of the Division’s front as soon as the infantry had left the start line, the tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment were to mop up and support the infantry on their objectives. Meanwhile, the armoured cars of the Divisional Cavalry would exploit towards La Cerralina on the right flank.

It was recognised that to keep up the momentum of the attack and even to hold gains supporting weapons would have to be got across the river without delay, whatever the weather, and the engineers were ordered to begin bridging as soon as possible. On the

right 5 Brigade was to be served by a Bailey bridge and, on the left, 6 Brigade by a folding-boat bridge. The engineers were also to clear mines north of the river. The wireless silence which had been maintained since arrival in the line was to be broken at zero hour, fixed in supplementary orders for 2.45 a.m. on the 28th. By that time the infantry were to be over the river and assembled on the start line. They were to carry rations for twenty-four hours, and as a precaution against the failure of the bridging plans a company of Italian muleteers stood by on the south bank to pack supplies across to the far side. All except operational traffic was kept strictly clear of the forward area and even operational vehicles were forbidden forward of the Strada Sangritana until their allotted bridges were ready, whereupon supporting arms would have precedence.

(iii)

The defences that would meet the New Zealanders as they toiled upwards from the floor of the valley had, as air photographs showed, been under construction for weeks past. In the Adriatic sector the German winter line (locally known as the Siegfried line) ran along the Sangro ridge from Fossacesia through Lanciano to Castelfrentano, along the road to Guardiagrele, and thence south and south-west along the foot of the Majella massif. The continuous system of trenches near the coast gave way in the New Zealand sector to more scattered strongpoints. These were most formidable along the road from Castelfrentano to Guardiagrele, where one heavily manned zone guarded the south-eastern approach to Castelfrentano and two others the two main road junctions – a hint of the impending struggle for control of the roads. A belt of wire along the road line linking the three zones was covered by machine-gun and infantry posts and guns had been sited and ditches excavated to defeat tanks. These defences, well dug in and camouflaged, were sited in depth (up to three kilometres in places) so as to prevent penetration at a single stroke and to expose assaulting troops, halted in their midst, to counter-attack. The approach to the main zone by way of Route 84 as it ran north from the Sangro was straddled by weapon pits on either side of the road. Ahead of them again were outposts close to the river, consisting of scattered trenches and weapon pits, many of them at the top of the cliffs, and mines were laid on the northern bank.

The potential strength of this elaborate defensive system, however, was never realised for want of troops to man it effectively, and eventually the line so long prepared had to be abandoned for one hurriedly improvised and by nature less strong but held with greater skill and stamina, and in weather more helpful to the defenders.

Whipped along by Lieutenant-General G. H. von Ziehlberg’s fierce energy, 65 Division had dug not as gardeners dig but with the intenser zeal of men whose continued welfare must be sought, if at all, below the level of the ground. Kesselring himself, who showed both his foresight and his solicitude by visiting the sector only a few hours before it was attacked, came away feeling that von Ziehlberg had prepared his positions wonderfully well and that everything humanly possible had been done to defeat an attack on 76 Panzer Corps. Von Ziehlberg himself thought well of his fortifications, and told Kesselring that he had greater confidence in them than in his men. But, as Nicias reminded his Athenians in their ultimate hour in Sicily long ago, it is men and not walls that make the city.

The four thousand front-line troops of 65 Division, which had been formed in Holland in 1942, were still raw and virtually untried in battle. Many of them were Poles, Lorrainers and other non-Germans; and it is probable that the 65th, like similar divisions, suffered in morale from complaints in the letters which the non-Germans received from home of ill-treatment by Nazi party agents. The division’s equipment was scanty and it relied wholly on horse-drawn transport. It had only two regiments, the 145th between the coast and Castelfrentano and the 146th to the west.

On its right as the New Zealanders assembled for the attack, 16 Panzer Division was being relieved by Berger Battle Group, an ad hoc formation taking its name from the commander of its nucleus, 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the first arrival of 26 Panzer Division (Lieutenant-General Smilo Freiherr von Lüttwitz). This last division, one of the corps d’élite of the German army in Italy, was being switched from the defences before Cassino and was arriving in small groups at long intervals.

These moves did not imply that the enemy was innocent of Allied intentions but rather that he was hastening to frustrate them. Kesselring substantially penetrated the strategic design, predicting an Eighth Army drive on Pescara to force the German Tenth Army to withdraw reserves from the western sector as a prelude to the advance on Rome of the Fifth Army. At least as early as the 24th, when the presence of a whole division of New Zealanders was suspected, Lieutenant-General Traugott Herr, commanding 76 Panzer Corps, was apprehensive of a three-division attack between the sea and the mountains, and on the evening of the 27th he appreciated that an attack was ‘very imminent’. This was a conclusion hardly to be avoided in respect of the 5 Corps front at least, in view of the obvious closing up of tanks and infantry towards the forward defended localities, the intensified air bombardment of Lanciano, the unusually heavy road traffic and the temporary lifting of the bad

weather. Fifth Corps did not, therefore, attain tactical surprise. It is possible that the New Zealand tactics of a silent appearance north of the river in strength caught the Germans unawares; but since they knew that the New Zealanders were present in divisional strength and armed with tanks, and since three new bridges were suddenly to be observed on the Strada Sangritana in the Division’s sector on the morning of the 27th, the probabilities are otherwise.

(iv)

Like many operations of war, the Division’s actual crossing of the Sangro held greater discomfort than danger. Eight men of 21 Battalion were killed or wounded by a mine south of the river, but the enemy, perhaps ignorant of the New Zealanders’ quiet approach, made no challenge.

Before midnight the battalions filed out over the Strada Sangritana and along tracks leading across the Piazzano to the riverbank. Ahead went the reserve companies, whose mission it was to prevent enemy interference at the start line. Then followed the assaulting companies and their attached Vickers gun platoons. At 25 Battalion’s crossing the wire snapped and another route was hastily reconnoitred nearby; otherwise no mischance occurred. Some men had cut staves for support against the turbulence of the river; some formed a chain, each man grasping the muzzle of the next man’s rifle; others clung to the taut wire. Thus, weighed down with arms and equipment, two thousand New Zealanders waded through the chilly, waist-deep waters of the Sangro and silently formed up along the lateral road on the northern bank. Thence, at 2.45 a.m., they advanced under the shielding fire of artillery and machine gun. The German defensive fire came down promptly but harmlessly in the riverbed. The attack by 5 Corps had begun some hours earlier, on the left the Indian brigade made a demonstration, and now the gun flashes, shell explosions, and slow curves of tracer illuminated the valley from the Aventino to the sea. The advance went well. The climb up the bluffs was slow but it was not until they had gained the heights that the infantry came under the scattered fire of mortars and small arms.

On the right, 23 Battalion, brushing aside unconvincing opposition, was so promptly in possession of its goal, Point 208, that artillery concentrations on this hill had to be hurriedly cancelled. Before daylight three companies were dug in, with one in reserve, an observation post had been established in a church on the hilltop, the Vickers guns and two 3-inch mortars had been brought forward and nine prisoners had been taken – all at the cost of six wounded.

The second battalion of 5 Brigade, the 21st, advancing on the left of the 23rd, was more stubbornly resisted, and at one stage the battalion asked that 23 Battalion should be ordered to send help, which the Brigade Commander refused to do. B and C Companies were unopposed in seizing the first objectives, Points 217 and 200 respectively, through which D and A Companies were to pass on their way to the final objectives, but the enemy was tenacious and two platoons of C Company, moving up a gully between the two heights, were held up by wire and small-arms fire from a machine-gun post skilfully sited in the cliff-face at the head of the gully. Captain Horrocks,5 commanding C Company, lost his life in trying to silence the machine gun from close range. Coming up under Major Tanner,6 A Company helped to break the deadlock. After a plucky solo reconnaissance, Corporal Perry7 located the Germans and directed two platoons along the gully and over the wire to a sharp encounter which cleared the way for a renewal of the advance. A Company then pushed on along the high ground to its objective. Meanwhile, on the right D Company had passed through B Company and was within 200 yards of its destination when fire from the front forced it to swerve from its course and made it glad of the assistance of a B Company platoon. In the darkness D Company had become dispersed, but when day broke the Germans on the final objective, finding themselves surrounded, gave themselves up. Five other enemy posts, bypassed during the night, were eliminated by B Company and a few remaining Germans in houses between the forward companies were taken prisoner. Six men of 21 Battalion were killed and 27 wounded, but its tally of prisoners was 74.

The right-hand battalion of 6 Brigade, the 26th, had a deep final objective on the high ground prolonging the Scorticacane feature. One company made its objective on the southern slopes without trouble, but the two companies which passed through it failed to carry out their tasks. C Company, aiming to capture the peak of the hill and then a second height 600 yards to the north-east, progressed to within 300 yards of its first objective, only to be checked when it attacked at dawn. The battalion had 5 killed and 14 wounded and took 32 prisoners. To the left of 26 Battalion, the companies of 25 Battalion set out by two devious but finally converging routes to take possession of the Castellata feature south of Scorticacane. A Company, advancing north from the road in order to skirt the cliffs, approached its objective from the east by following up a

gully, whence it climbed Castellata, searching farmhouses as it went. It was overtaken, as planned, by C Company, which went on to consolidate on its allotted heights. D Company went straight along the road to occupy Point 122, between the road and the river. From here, after 24 Battalion had passed through, it swung north-west to capture the ridge between Castellata and the Gogna stream, while B Company succeeded it on Point 122. All the battalion’s companies were thus safely on their objectives by first light. Mines caused more than half the battalion’s casualties of 5 killed and 28 wounded.

Like 25 Battalion, the 24th, on the left flank of the attack, made a successful double thrust. Waiting until Point 122 was firmly in the hands of 25 Battalion, two companies, of the 24th passed through, A Company on the road working westward and D Company south of it. After silencing a machine-gun post covering the road bridge over the Gogna stream, A Company continued along the road and then turned north to climb Marabella, a hill in the angle between the lateral road and Route 84. The defenders, having satisfied their military consciences by a formal display of ragged small-arms fire, capitulated as the infantry drew near. One platoon was left to hold Marabella while the rest of the company descended without delay to Route 84, in time to disconnect the charges beneath a road bridge and two culverts. Here the platoons dug in and threw back a small enemy counter-attack, evidently intended to blow the bridge. On the left D Company, followed by C Company, easily occupied Taverna Nova, the area bounded by the two roads and the Sangro, where enemy troops surrendered without a fight. The battalion took 106 prisoners at the cost of 4 killed and 12 wounded.

By dawn the effort by the infantry had put them on all their final objectives except that of 26 Battalion among the hills in the middle of the Division’s front. Enemy resistance had been at best sporadic: the young troops of 65 Division showed but little stomach for the fight. Unnerved by the severity of the bombardment, with their wire defences smashed and some of their mines exploded by shellfire, many of them surrendered as soon as the New Zealanders got to close quarters. First Battalion of 146 Regiment, which had had to face the assault of five New Zealand battalions, was reported to have lost half its fighting strength in casualties.

The fortuitous advantage of feckless opposition does not diminish the merit of the night’s work by the New Zealand battalions, which contained many men fighting their first action. Wet-shod and chilled from the Sangro, they executed almost to the letter a plan of some complexity, finding their way in the dark over steep, difficult and unfamiliar country and rapidly organising to hold their gains against

counter-attack. As Lemelsen, commanding the Tenth Army, confessed, they had ‘got in amazingly soon’. But could the break-in be capitalised into a break-through? The answer to this question depended in large part upon the speed and effect with which supporting arms could be brought to bear in aiding the infantry.

(v)

Most welcome to the tired New Zealanders north of the Sangro would be armoured reinforcement, and the tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment were on the move towards the river within a few minutes of the opening of the divisional artillery bombardment. But between the men in their tanks on one side of the Sangro and the men in their slit trenches on the other lay the frustrations of mud and water.

An anxious passage in the dark over the soft soil of the Piazzano ended for the leading tanks of A Squadron when they entered the water shortly after 5 a.m. Of the squadron’s tanks, all but one, which was stranded in the first stream, reached the northern side with the help of 5 Field Park Company’s bulldozer, but only three forged a way through to the lateral road that morning. When daylight came eleven tanks were bemired in the ploughlands north of the river, and the bulldozer itself, like a doctor stricken with his patents’ disease, rested helpless in the mud. Even the three tanks that reached the road were pursued by ill-luck; they were delayed by demolitions and that night had still not reached the forward troops of 23 Battalion.

Tanks of the other squadrons, with their commanders reconnoitring a route on foot, found a less treacherous access to the road farther upstream. At 8 a.m., by gingerly and patient manoeuvring, C Squadron had gathered six tanks on the road; they drove westward as far as Point 122 and then up over the hill of Castellata to 25 Battalion’s forward positions, where they disposed themselves to fire on the enemy to the north. B Squadron also contrived, though not until the early afternoon, to get tanks forward to protect 26 Battalion on Scorticacane and 24 Battalion on Marabella – an enterprise made hazardous not only by the steep, slippery going but also by minefields, through which infantry guides picked a safe way. The armoured cars of C Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment found the ford even less negotiable than the tanks. After all but one of the first troop had become stuck in the riverbed, the rest of the squadron was ordered to remain on the south bank.

The attempt to bring armour rapidly forward to enable the infantry to exploit the night’s advance was defeated by mud - normally a more difficult obstacle to an army than water. By daylight not a single tank was present in close support of the

infantry; by nightfall about fifteen were up with the leading battalions of 6 Brigade, but on the 5 Brigade front none had joined the forward troops. The large element of failure was inherent in the armoured weapon operating in such terrain at the end of a European November; the not negligible element of success was won by persistence and initiative. What stalwart effort could do had been done, and for the first time that day New Zealand infantry lay under the guardian guns of New Zealand tanks.

The 3-inch mortars accompanied, and the Vickers machine guns closely followed, the river crossing and the advance of the infantry battalions, and these weapons were ready for action at daybreak. Anti-tank guns and support vehicles, however, had to await the bridging of the river. As in the days of preparation, so now in the day of assault, the role of the engineers was pivotal. Their task and that of the infantry were mutually dependent – for whereas the engineers had to rely on the infantry to provide them with room to work in and to deny the enemy, as far as possible, a sight of that work, the infantry could not advance far until traffic coursed freely over the river. The fine margin by which Masséna and Lannes staved off disaster at Aspern and Essling with their backs to the Danube stands as a caution to all forces attacking in front of a river insecurely bridged.

At zero hour the working parties of engineers were waiting at the two bridge sites for the sixty trucks loaded with bridging equipment to approach along the taped and lighted tracks. On 5 Brigade’s front, 8 Field Company set to work with a will about 4.30 a.m. and when, three hours later, German observers peered across the river through the lifting shadows of dawn, there was the bridge and traffic was passing over it. Planned to span 90 feet, this Class 9 Bailey bridge was found on being pushed out to be from 10 to 15 feet short, but ramps erected on the north side filled the gap satisfactorily. Yet no bridge is more useful than its approaches, and the soft and as yet unmetalled track to the lateral road beyond the river robbed this one of much of its value; all heavy trucks had to be winched or towed through the mud, and the rate of traffic across the bridge fell to eight vehicles an hour. From Colle Barone on the left the enemy could direct accurate shellfire on to the bridge and the fact gave stress to the name HEARTBEAT with which it had been endowed before birth. In spite of casualties to men and vehicles, most of 5 Brigade’s support vehicles were over by 11 a.m. and with their battalions by the afternoon.

Misfortune befell the platoon of 6 Field Company detailed to build the folding-boat bridge for 6 Brigade. The recovery of trucks that ran off the track south of the river and the need for towing

trucks through the loose gravel of the riverbed cost time and delayed bridge-building until 6.30 a.m., and the work had to go on in the embarrassment of full daylight. At 8 a.m., when only one bay had to be completed, a direct hit by shellfire sank several boats and killed nine and wounded thirteen of the working party. The task was abandoned until nightfall. By 9.15 that night LOBE bridge was open to light traffic. Meanwhile a few vehicles of 6 Brigade had been diverted across HEARTBEAT bridge.

For all that the engineers could accomplish many men had still to wade through the waters of the Sangro and tramp its stony floor. Though the lightly wounded were treated in regimental aid posts north of the river until they could be evacuated by ambulance or jeep, the more urgent cases had to be carried across by stretcher-bearers, who were stationed in teams at the riverbank. The one bridge could not be spared for the traffic in supplies on the 28th, and they were entrusted to the company of Italian muleteers. Reserve rations and ammunition for twenty-four hours, transferred from Army Service Corps trucks, crossed the river by mule train when darkness fell, and at the same time carrying parties bore to the forward troops containers heavy with the hot food that cheers. So much had to be committed to the continued good graces of the Sangro.

(vi)

The enemy’s reaction to the overnight offensive was less vigorous than had been expected. The fact was that the Germans, though not surprised, were still unprepared, in that their troop dispositions had been forestalled, and their resources were unequal to the mounting of a co-ordinated counter-attack. A fighting and disciplined withdrawal to the Sangro ridge, punctuated by spoiling jabs to slow down the pursuit, was the most that they could hope to achieve until fresh troops could be rushed forward to restore stability. Even if the communications of 65 Division had not been disrupted and if its infantry had been more numerous and less easily panicked, its endeavours to form up for a counter-attack would still have been frustrated by the weight of bomb and shell. Even if the German gunners had not been rationed for ammunition, and if the German tanks had been able to manoeuvre freely on the muddy hillsides, they would still have been largely silenced or immobilised by our aircraft and artillery. ‘We simply can’t do a thing against his shellfire and aircraft,’ reported the Chief of Staff of Tenth Army to General Siegfried Westphal, Chief of Staff to Kesselring.

The German plight was made the more serious by the severe wounding that afternoon of Ziehlberg, ‘the heart and soul of the

whole enterprise’, as he was called by Kesselring, who said later that had he not become a casualty his division would have stood up to the battering it received. Its recovery certainly proved too much for his successor, Colonel Ernst Baade, to effect, even though he was one of the most dashing German commanders on the Italian front. During the day, therefore, 65 Division pulled back three or four thousand yards up the ridge towards the heart of the winter position, and the New Zealand infantrymen were able to consolidate with little distraction, save from local gestures of defiance.

Infantry activity was most marked in 23 Battalion’s sector on the Division’s right flank. While our forward troops watched enemy movement round buildings to the north, a party of German raiders, in a bold sally made under the cover of a convenient gully, surprised and killed at their posts three men of the battalion holding the defiladed approach. They then suddenly appeared on the forward slopes of Point 208, above and on the flank of thirteen men of a machine-gun platoon, whom they marched off to captivity before a hand could be lifted in protest. Farther west, the men of C Company 26 Battalion were again involved in scuffles for a final objective which continued to elude them; well-aimed machine-gun fire sent them to earth for long periods and about 1 p.m. the artillery was called upon to cover with smoke and high explosive the withdrawal of nine of our men cut off in a house. On the left 24 Battalion also found work for New Zealand gunners. At daybreak enemy infantry debussing on Route 84 were scattered by shellfire and several times during the day concentrations were fired on a height west of the road and on Colle Barone, still farther west, both of which overlooked 24 Battalion’s positions.

Compared with the active counter-battery and harassing fire of our own gunners, the German gunfire was light, except on the river crossings. Nor did any enemy tanks appear. For the first time, however, enemy aircraft attacked in the Division’s sector but, whether directed against the tanks or the bridge, the three raids of the day were fruitless.

They did not disturb our forward troops in their work of reorganising and preparing measures against counter-attack. Except at the inter-brigade boundary – a stream flowing in a deep gully - where 21 and 26 Battalions were in sight of each other without having actual contact, a continuous divisional front was established, and on the right 23 Battalion was in touch with 6 Lancers, who were patrolling the gap between the Division and 21 Indian Infantry Brigade, the left-flank formation of 5 Corps.

As darkness fell on the 28th, the Division was secure on all but one of its objectives and presented a well-knit front to the enemy;

behind it one bridge spanned the Sangro and another was nearing completion; a few tanks were forward with the infantry, the forerunners of many to come, and supporting arms and supplies were not lacking; the outposts of the German winter line had been partly overrun and the enemy, weakened by substantial casualties and stunned by the ferocity of our bombing and gunfire, was reeling back to his main defences on the Sangro ridge. In the twenty hours since the first battalion moved off towards the river, the Division had suffered about 150 casualties and had captured well over 200 prisoners, all from 65 Division.

(vii)

Patrols from four battalions on the night of 28–29 November having probed forward unopposed, it was possible on the 29th to contemplate limited advances, though the reinforcement of the existing bridgehead with tanks, anti-tank guns and armoured cars remained a first claim on the Division’s energies. The Bailey bridge, though under intermittent shellfire, gave passage to anti-tank guns, but the now too-familiar alliance of mud and gradient delayed their arrival with the battalions, some of which waited until nightfall for their reassuring presence. Typically, a bulldozer towed the guns over the last stages of the journey to 21 Battalion, which meanwhile had manned a captured 50-millimetre anti-tank gun and an 81-millimetre mortar. By early afternoon C Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment, by will and skill, had mustered all three troops on the lateral road, but demolitions checked it on its assignment of protecting the Division’s right flank and maintaining liaison with 8 Indian Division. Air support was lavish but, in the well-grounded opinion of our troops, undiscriminating; for although towns, road junctions and enemy gun positions were named as targets for the day, bombs fell also among our own men on Colle Barone, and twice during the afternoon American fighter aircraft sprayed bullets at the Sangro bridge and on gun areas and roads south of the river.

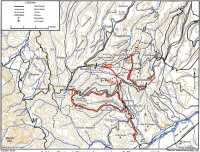

The main advance of the day, on the left flank, was essentially precautionary. Just as the clearing of the delta of high ground between the Sangro and the Aventino was a necessary preliminary to the river crossing, so the capture of Colle Barone, a feature west of Route 84, which commanded the Sangro bridges, was an indispensable condition of progress up the slope north of the river. The fatigue of the infantry, the lack of armoured and anti-tank support, and reports that the hill was still held in some strength caused the attack to be postponed from the 28th to the 29th. At 12.30 p.m. three field regiments began their fire plan, in the shelter of which three troops of B Squadron 19 Armoured Regiment, each followed

Advance to Castelfrentano, 28 November–2 December 1943

2 New Zealand Division’s Operations, 2 December 1943

by a platoon of B Company 24 Battalion, crossed Route 84 to occupy Colle Barone and two objectives north and south of it. Within little more than an hour the tanks and infantry had completed their tasks, in the face of only shell and mortar fire and the usual impediment of soft ground, in which some of the tanks had bellied down.

On this occasion, it could hardly be said that the Division fought ‘not as one that beateth the air’. As suspected, the artillery support was a waste of effort and ammunition, for the Germans had abandoned the area the night before, leaving behind only a few stragglers who needed no such incentive to surrender. So slight was the contact that the enemy believed the hill to have been captured by 8 Indian Division. This hill was, indeed, the guiltless cause of much misapprehension, for the false report that it had earlier fallen to the enemy prompted the commander of Berger Battle Group to withdraw his outposts more smartly than he would otherwise have done.

The other battalions made less demonstrative but useful advances in the afternoon and during the night. Preceded by patrols which reported the way clear, they moved forward distances of more than a mile on 6 Brigade’s front and somewhat less on 5 Brigade’s, so that when the advance halted in the early hours of the 30th the line ran roughly in a crescent from the outskirts of the village of Caporali on the right, across country to the junction of the railway line with Route 84, and thence to Colle Barone.

(viii)

The 30th was another day of quiet advances during which the infantry often found the upward lie of the land, the clogging mud and the mines sown in it more vexatious than the opposition of Germans. A tiring uphill slog brought the New Zealanders within striking distance of the main defences, into which 65 Division on the right was hastily, and 26 Panzer Division on the left more deliberately, withdrawing. Twenty-second Motor Battalion, moving in to hold the left flank, released 24 and 25 Battalions for a main thrust directly towards Castelfrentano by 6 Brigade. The brigade’s axis, thus deflected slightly to the right, would leave the north-south stretch of Route 84 free for a diversionary attack westward by 18 Armoured Regiment and 22 Battalion. Fifth Brigade would support the Castelfrentano drive from the right, 19 Armoured Regiment would follow up, and the Divisional Cavalry Regiment would patrol as usual on the right.

In accordance with this general plan, the infantry battalions, accompanied by tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment, closed up towards the Sangro ridge. A northerly advance of a mile by 26 Battalion was virtually unchallenged, but 25 Battalion had to fight for San Eusanio railway station and a height north-east of it. Patrols had to clear both places before the companies could occupy them, the clash on the hilltop bringing in twenty prisoners at a cost of two killed.

The longest march of the day fell to 24 Battalion. It was withdrawn from its positions west of Route 84 and directed up the eastern bank of the Gogna stream to the lower slopes of Point 398, a hill overlooking Castelfrentano from the south and within a hundred yards of its outlying dwellings. The march of several miles up steep slopes and over sodden ploughlands ended soon after nightfall, when the leading company settled in across the Guardiagrele–Lanciano railway line where it runs round the spur of Point 398. A patrol found the crest of the hill wired and heard enemy movement. Signs that this part of the main (or Siegfried) line was manned – trip-wires, machine-gun fire, flares and the

sound of military movement – were also reported by patrols of 26 Battalion exploring towards the main road east of Castelfrentano.

While 6 Brigade poised itself to begin a break-through of the winter line, 21 and 23 Battalions after dusk advanced the 5 Brigade front on the right in the steps of patrols that had reconnoitred well forward during the day without meeting the enemy. On the two wings of the Division vigilance was maintained, on the right by the armoured cars and on the left, far to the south-west in a quieter sector, by 2 Machine Gun Company, the successors in that area of 19 Indian Brigade.

Meanwhile, supporting arms steadily accumulated in a bridgehead that was by now outgrowing the name. This reinforcement was hastened by the opening on 30 November, beside HEARTBEAT bridge, of a Class 24 Bailey bridge (TIKI) strong enough for the use of tanks. Raised high above the waters by bulldozed approaches, the new bridge gave proof of its robustness on 4 December, when it was the only one on the Eighth Army front to survive the flooding of the river. All traffic going forward had to cross it and return, first by HEARTBEAT bridge and later by LOBE bridge. In spite of this one-way circuit, convoys still jammed at the crossing and made painful progress through the well-churned mud on the northern bank. Nevertheless, within a few hours of its opening an armoured regiment and the whole of the divisional field artillery had crossed the bridge and rearward communications were secure enough to give no logistic worries to those directing the operations four miles away on the lip of the Sangro ridge. To those embattled heights it is time to turn again.

II: Castelfrentano and Beyond

(i)

December was only a few hours old when the first infantrymen stood on the crest of the ridge and in the heart of the prepared defences. Starting at 8.45 a.m. from its overnight position about 500 yards from the hilltop, D Company of 24 Battalion led the attack on Point 398. The men of 17 Platoon, working towards the north-east round the side of the hill and up a gully to Route 84, were harassed throughout the day by heavy fire and only one section reached the road, where, like the others, it had to lie low; but the enemy also found movement uncomfortable in this area, failing in four attempts to infiltrate down the gully.

The other leading platoon, No. 16, advanced directly uphill. On the way it disposed of two German posts, of which civilians had given warning, and on reaching the brow of the hill saw and

occupied a large building near the main road and on the eastern edge of Castelfrentano. Since the approach to the town was swept by mortar and small-arms fire, the platoon was ordered to hold the building, which proved to be a hotel, as a fortress. Two prompt enemy attempts to gain admission were repulsed, but the little garrison, thinned by casualties, needed help. Help it received from 18 Platoon, dashing in under fire. Under Sergeant Kane,8 this force beat off a third and last counter-attack early in the afternoon. Thereafter until dusk the hotel became a target for the German artillery whose many hits on the building forced our men to abandon the vista of the upper stories for the ground floor. Between dusk and one o’clock the next morning machine-gunners of the German rearguard took up the ‘hate’. D Company lost three men killed and twelve wounded.

While 24 Battalion fought an action that was the presage of a more gruelling future, the rest of the infantry, closing in on Route 84, began the investment of Castelfrentano from the south. Coming up uneventfully on 24 Battalion’s left, 25 Battalion posted its foremost platoons in a position to threaten Route 84 west of Castelfrentano and only 400 yards below the town itself, and between 24 Battalion and 5 Brigade 26 Battalion during the night of 1–2 December approached the railway station 1000 yards south-east of the town.

The success of 24 Battalion in getting a foothold on the ridge promised so well that soon after midday on the 1st the Divisional Commander cancelled a plan for a set-piece night assault on Castelfrentano with artillery support. The decision was justified not only by the German failure to dislodge the dogged defenders of the hilltop hotel and by the stealthy progress of the other 6 Brigade battalions, but also by the shock administered to the Germans by 5 Brigade’s night advance, which expedited the enemy’s withdrawal from Castelfrentano.

Ordered to seize the dominating plateau east of Route 84 where it trends to the north towards Lanciano, the two battalions were held up by machine-gun fire about dusk on a precipitous slope half-way to their objective, and resumed their climb after nightfall. The right-flanking battalion, the 23rd, made its ground with little incident, but the leading platoon of the 21st, straying somewhat at large over this rugged country, stumbled into enemy machine-gun nests, attacked them and, aided perhaps by the studiously boisterous approach of two other platoons drawn up by the noise of the affray, captured thirty prisoners. These last two

platoons of A Company 21 Battalion, however, had not yet done with the night. As they leapfrogged forward by platoons one of them was fired on from the right, whereupon the other worked round behind the enemy’s position, rushed it, and closed in, giving the enemy the impression, in the darkness, of being encircled. Another sixty Germans gave themselves up.

The success of the infantry brigades, backed up by the Divisional Cavalry Regiment, which kept pace on the right, had been made easier by the subsidiary thrust on the left, where the efficacy of armour as a magnet for shellfire was abundantly demonstrated. Eighteenth Armoured Regiment and 22 Battalion were despatched from the south up Route 84 on 1 December to the junction with the main road from Guardiagrele. The tanks were stopped nearly two miles short, however, by shellfire and mines and deployed near the junction with the minor road leading through San Eusanio to bring fire on to their objective. There they took considerable punishment from the artillery of 26 Panzer Division – eight tanks were put out of action – and no further advance up Route 84 was attempted that day. After dark a patrol of infantry and engineers found the road a mile from the main junction blocked by a demolished house, with trip-wires to signal for fire on the junction itself. Behind these delaying devices the right wing of 65 Division was preparing to withdraw.

By the morning of 2 December the omens were propitious. On the right, the two New Zealand infantry brigades imperilled the German hold on a long stretch of Route 84 on both sides of Castelfrentano, itself a bastion of the main defence line; on the left the diversionary attack was drawing near to the same line; and the Division appeared on the verge of hustling a much-perturbed enemy out of its sector of the Winterstellung.

Had the sore straits of the German command on this front been known to the Division, its expectations would have been more and not less roseate. The tattered 65 Division, stretched out from the coast to an area west of Castelfrentano, was in disgrace; one of its regiments had by this time yielded a thousand prisoners, both had had high weapon losses, and the Tenth Army commander was soon to order a court-martial inquiry into its conduct. Further, it had permitted 5 Corps on the New Zealanders’ right to penetrate the Siegfried defences.

To this threat of collapse the German response, reduced to its simplest elements, was twofold. First, the front had to be reinforced. It was possible for Herr to do this partly from his own means by gradually transferring fresh and mettlesome parachute units from the relatively impenetrable sector among the mountains of the

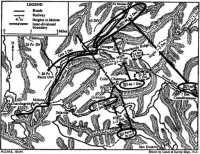

Withdrawal of German Units, 1 and 2 December

Majella massif to more decisive sectors nearer the coast; and this redistribution was already proceeding when the storm broke and gave it greater urgency. Command of a battalion of paratroops was inherited on the 29th by the experienced but numerically weak 26 Panzer Division when it assumed control of the sector on 65 Division’s right and opposite the New Zealanders’ left flank. Herr also built up a mobile reserve of infantry and tanks, withholding a large part of 26 Panzer Division for the purpose. But, as Kesselring recognised, outside help could not be stinted, and he made available 90 Panzer Grenadier Division, a reincarnation of the Division’s old desert foe, 90 Light, which took over the sector on 65 Division’s left in the first days of December.

Secondly, an alternative had to be found for the original winter line running along the Sangro ridge, which could no longer be held in its entirety. The pith of Herr’s plan was to stand firm on the Siegfried line in the mountainous sector west of Melone, a road junction a mile east of Guardiagrele, and on that pivot to swing back, holding the line of the Orsogna-Ortona road to the sea, behind the obstacle of the Moro River. Normally such a manoeuvre, even under pressure from troops elated by their capture of long-prepared positions, would not have been fraught with great peril;

but the circumstances were not quite normal. To retract the line safely, it would be necessary to concert the withdrawal of the two formations holding it – one of them, 65 Division, gravely depleted, partly demoralised and thankful to fall back; the other, 26 Panzer Division, far less roughly handled, unbeaten and determined to retire in good order upon tactical necessity alone.

In the event, the withdrawal was not smoothly concerted. Confusion was thickened by the simultaneous effort of 76 Panzer Corps to shorten 65 Division’s front by introducing 90 Panzer Grenadier Division and by side-slipping 26 Panzer Division to its left as it came back. The manipulation of slender and fluid resources was deemed to entail a copious flow of instructions from corps to the divisions. At a delicate phase of the operation, continual boundary changes and untimely reliefs unsettled the troops and provoked from divisional staffs a rumble of discontent which the war diaries echo. A study of these documents, it must be said, suggests the inexorable military sequence – order, counter-order, disorder.

The worst disorder occurred on the boundary between the two ill-matched divisions. It is now apparent that, by the night of 30 November–1 December, if not earlier, they were out of step in their withdrawal. That night, conforming with the rest of 65 Division, 146 Regiment pulled back into the Siegfried line where it ran through Castelfrentano, and it was II Battalion of this regiment that resisted the New Zealanders on the eastern outskirts of the town next day. The corresponding withdrawal of 26 Panzer Division’s infantry – 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment and II Battalion 1 Parachute Regiment – brought the bulk of its forces into an intermediate position forward of the Siegfried line, with only about a third of them manning the main defences in continuation of the line already occupied by 146 Regiment. The panzer division, expecting a few days’ comparative respite until the New Zealanders closed up to the Siegfried fortifications, was perhaps not unduly dismayed to learn, early on the morning of the 1st, that the paratroops in the advanced positions could find no neighbours on their left, but corps promptly ordered a retirement that night to the Siegfried line so as to regain contact with 65 Division.

The day’s orders from corps included instructions for a further withdrawal the same night to the final line from Orsogna to Ortona by 65 Division and for a leftward shift in the inter-divisional boundary; 65 Division’s right wing was to rest on Point 341 on Colle Chiamato, and the paratroops manning the Siegfried defences round the village of Graniero were to extend their left to keep touch. These confusing orders, retiring the infantry division upon a new defensive line and the panzer division upon an intact part of the old

(between Melone and Graniero), overstrained the junction of the two divisions. Here, on the morrow, 2 December, a grave fissure was to open, through which the New Zealanders might pass in pursuit of a fleeting opportunity.

(ii)

Even in ignorance of their enemy’s tribulations, our troops had cause to begin the 2nd in good heart, and the day’s events, to right and to left, quickened their hopes. The capture of Castelfrentano was the first event in two days of decision. Heralded by strafing attacks from the air, troops of 24 Battalion entered the town at 7 a.m. They were too late to trap the Germans, who had slipped out overnight, quitting the comfort of billets and the safety of commodious dugouts for the bleaker hills east of Orsogna; but they were not too early to be greeted by the inhabitants with manifestations of joy and with the festive wines and pasta customarily pressed upon the liberators of Italian towns.

There was little time to savour the pleasures of minor conquest, for more significant conquests now seemed to lie within the Division’s grasp. The palpable crumbling of the main winter line along the road from Guardiagrele to Castelfrentano and the tame evacuation of Castelfrentano itself were a spur to the instant follow-up that might tear an irreparable hole in whatever defensive system the enemy could improvise to the rear. The New Zealanders in the last four days had waded through the Sangro without having so much as a rifle-shot fired at them; they had brushed aside or into the prisoner-of-war cage a cowed enemy in their climb to the top of the ridge; and now the bastion town of Castelfrentano had dropped like a ripe fruit into their hands. In an exultant mood engendered by this retrospect, Montgomery and Freyberg agreed that the Division would be in Chieti in a couple of days. Orsogna–San Martino–Chieti was the axis of advance defined in the divisional orders that morning of the 2nd.

The main task of the day was allotted to 6 Brigade, with armoured support. While 5 Brigade consolidated in the area of Castelfrentano, 6 Brigade was directed to exploit on the right concurrently with 4 Armoured Brigade’s diversionary thrust on the left. After a forward reconnaissance, Freyberg was urgent for a swift drive into what was, in fact, the enemy’s final defence line. Parkinson, for 6 Brigade, was ordered to push on day and night to Orsogna, and Stewart, for 4 Brigade, to make with all speed for Guardiagrele and San Martino.

The tanks of C Squadron 19 Armoured Regiment were under 6 Brigade’s command. Having dexterously gained Route 84 after a night spent struggling up greasy, narrow lanes, they were despatched

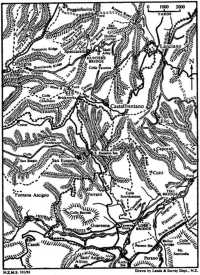

Roads and Landmarks in New Zealand Division’s Area

on the right flank to follow a rough track running north to the Lanciano–Orsogna road and thence westward to Orsogna. Twenty-fourth Battalion was sent straight across country along the hypotenuse of the triangle to cut the Lanciano road a mile east of Orsogna, and 25 Battalion was to advance westward down Route 84 to meet 4 Brigade’s tanks and infantry coming up from the south.

Since 4 Brigade’s force was divided into two columns, the Division was pointing five aggressive fingers at the Germans’ last line of resistance – a column of tanks and two battalions of infantry making for Orsogna from the east, and two mixed columns of tanks and infantry heading towards the vital road junction of Melone, whence they might threaten Orsogna from the south and Guardiagrele from the east. The simultaneity of their actions and of the actions of the enemy opposing them baffles the art of the historian, who, while he unfolds the battle in one part of the field, must stop the clock and freeze the fight in all the others.

For the tanks of C Squadron 19 Regiment, operating on the right flank, it was a day of promise never quite redeemed, and their influence on the day’s events, like their physical position, was peripheral. Leaving Castelfrentano by the northern road shortly after eleven o’clock, they were checked about a mile out of the town by machine-gun fire. The stronger force then haled forward by the reconnaissance troop overran several enemy posts, but in the absence of infantry the rounding up of the victims was incomplete and some escaped. During the afternoon, however, our tanks and carriers tidied up the area west of the road. Meanwhile the squadron, firing merrily as it went, hurried north to the Lanciano–Orsogna road and then west through the village of Spaccarelli, but its career was abruptly halted a few hundred yards beyond the village by the demolition of a bridge across the Moro stream. Unable to find a way over or round the obstacle, the squadron had no choice but to prepare a laager for the night; it played no further part in the ensuing action except to subtract from the strength of the infantry, since a company of 25 Battalion was detached to protect it overnight.

The men on their feet advanced with less hindrance. Following the Roman road north-west from Castelfrentano, 24 Battalion descended the steep gully in which the Moro flows, crossed the stream, climbed to the Lanciano–Orsogna road and by mid-afternoon took up positions north of it, with the forward company hardly a mile from the eastern edge of Orsogna. A section sent out immediately to reconnoitre drew fire from light anti-aircraft guns on the outskirts of the town; it withdrew, leaving behind two observers. At 4.30 they reported that about seventy Germans appeared to be forming up for a counter-attack. Of this no more was heard. About half an hour later, towards dusk, the defenders of Orsogna were again called on to fire, this time against a working party of 25 Battalion. Moving to the left of the 24th along Route 84, 25 Battalion had dug in west of the road where it bears south, and at 4.30 had sent out a patrol to reconnoitre a route for vehicles to Orsogna across Colle Chiamato. It was the working party following this patrol that

occasioned the second burst of fire as it approached Orsogna from the south-east. Its reaction was to send forward a fighting patrol, which returned unscathed with five prisoners.

These exploratory actions were more significant than the men of the two battalions realised. Interpreted as unsuccessful efforts to force an entry into Orsogna by surprise, the two slight skirmishes outside the town rang bells of alarm in the ears of an enemy already disconcerted by the day’s developments. At 26 Panzer Division headquarters Lieutenant-General von Lüttwitz had spent an anxious morning. From ten o’clock onwards his infantry in the Siegfried line running east from Melone were periodically reporting the minatory movements of 4 Brigade’s forces, but an even more acute worry arose from the old trouble on his left flank. There his parachute battalion again reported itself as out of touch with 65 Division’s right wing; he himself went to Point 341, the agreed point of contact, where 65 Division asserted it had troops, but he could find none, for they had left (so it was reported) at 9.30 without informing their neighbours.

With tanks and infantry battering away towards Melone in his front and with his left wing suspended in mid-air, Lüttwitz became concerned for the security of the final defensive line from Melone to Orsogna, and at 12.45 he received permission from corps to call 26 Panzer Reconnaissance Unit from reserve to man the line as far as Orsogna, where it was to link up with 65 Division, until his infantry should be able to make an orderly withdrawal to the new positions. The summons to his reconnaissance unit went out promptly, but it took time to answer, and in the interval the menace to his left wing loomed larger. At 1.20 the panzer division’s war diarist wrote: ‘All efforts by the division and corps to establish contact on the left ... failed. A gap remained between the division and 65 Division, whose right wing could not be located’. Shortly after three o’clock the paratroops reported the enemy pushing round their left shoulder. ‘The enemy,’ says the diary, ‘had evidently found the gap and was taking full advantage of it. If the fire of our three batteries could not halt the enemy, it was likely that the left wing of the division would be outflanked’.

It was the men of 25 Battalion who thus happened upon the rift in the line; but on their right 24 Battalion had likewise found it, and it was the desultory cannonade before Orsogna about four o’clock that brought home to the panzer division the extent of its envelopment and steeled Lüttwitz’s chief staff officer, in the commander’s absence, to issue at five o’clock an order for withdrawal to a ridge in front of the Melone–Orsogna road and to instruct the division’s reconnaissance unit to take command of Orsogna and hold the

town at all costs. But it was not until 6.30, long after dark, that the unit’s first company reached Orsogna. There it assumed control from the remnants of II Battalion 146 Regiment who had observed the approaching New Zealanders before nightfall, marvelling perhaps, and certainly thankful, that they had not made more audacious use of their advantage.

(iii)

By this time, as its dispositions showed, 26 Panzer Division was awake to the New Zealand Division’s tactics of masking its main blow on the right by a feint, or rather a diversionary attack, on the left; the fact had been sufficiently announced during the afternoon. Yet until that time the progress of 4 Brigade might have appeared to the Germans as the most disquieting of hostile activities, and even later they appreciated the threat to the pivotal road junction of Melone, where the new defensive line joined the unbreached part of the old.

In its advance towards this point 4 Brigade was offered a choice of routes. Two lateral roads branched westward off Route 84, one a section of the direct road from Castelfrentano to Melone and the other leaving Route 84 two miles farther south, passing through San Eusanio, and converging with the first about a mile east of Melone. Resuming the previous day’s advance from the southern of the two road junctions, B Squadron 18 Armoured Regiment, closely supported by B Company 22 Battalion, reached the northern junction by 10 a.m., just as 25 Battalion was setting out from Castelfrentano for this rendezvous. Opposition was confined to shellfire and a ditch across the road, which a bridging tank expeditiously filled in.

When he received his instructions to hasten on to Guardiagrele and San Martino, Stewart sent 22 Battalion, with B Squadron under command, westward along the northern road from this junction, and a second column comprising 18 Regiment headquarters and C Squadron, with 1 Motor Company under command, along the southern road through San Eusanio. Both columns were preceded by armoured cars of the Divisional Cavalry Regiment.

The German engineers had prepared four demolitions along the northern road, but it was not until they were half-way to Melone that the tanks, though under frequent shellfire, were delayed by cratering. It was by then nightfall, and the Germans who had held the line of the road during the day were falling back. Our own infantry followed hard on the heels of the German rearguards, who stalled off pursuit by a second demolition, by small-arms fire from the cover of village buildings along the way, and by blowing up in the middle of the road a lame tank which had been towed back

from the main road junction. Near the village of Salarola three Germans tarried too long and fell prisoner. One of them, coolly directing the retreat of his rearguard, was the 27-year-old commander of I Battalion 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, by reputation ‘the most capable and bravest’ battalion commander of 26 Panzer Division. Still the men of 2 Motor Company pressed on in the darkness and they were nearing the junction of the two lateral roads when a third demolition was blown in their faces, making a hole about forty feet across. This in turn they skirted, only to find the enemy covering the road from posts sited in the prearranged delaying line before the Melone–Orsogna road. Not until next morning, the 3rd, did the company confirm the enemy’s withdrawal from this position – a hurried withdrawal, it appeared, from the amount of abandoned equipment left scattered about.

By this time the two columns were reunited. The southern road had proved to be poor and steep, but it was not defended by infantry and the principal impediments were shellfire and a cavernous anti-tank ditch. The German artillery was eventually silenced by fighter-bombers called up to assist, and the ditch was eventually made passable by a bridging tank.

Stewart’s force was now able to resume its drive for the next road junction. A few straggling roadside houses, hardly worth the cartographer’s notice, gave it the name of Melone; a steep bluff behind it gave it defensive strength; and its position on the new line mid-way between Guardiagrele and Orsogna gave it tactical importance. It was a key to the Orsogna ridge, and here, if anywhere, the Germans, who had been spending ground lavishly since 28 November, must stand and fight.

An hour after daylight on the 3rd 3 Motor Company advanced to the assault on the Melone road fork while New Zealand artillery bombarded the objective for three-quarters of an hour. The sanguine temper of the New Zealand command at the time is manifested by Stewart’s orders to a squadron of armoured cars to push through to the road fork on the right flank and then to exploit northwards to meet 6 Brigade emerging from Orsogna. These expectations died at once and on the spot. Heavily shelled as they approached along the road, the attacking infantry were discouraged from the outset, and the support of tanks which climbed a hill south of the road could not abate the fury of fire that started up in Melone as some of our men came within sight of it. An hour after their setting out they were recalled from the attack; they were now to hold a firm base for a fresh attempt that night. About midday instructions were issued to occupy the road junction when hostile fire slackened or after dark, and to exploit to Guardiagrele. In the late afternoon the

battalion was ordered to occupy the position; otherwise no attack would take place. The waters of optimism were evaporating. That night a patrol ascertained that Melone was indeed defended, and more strongly than by day. The attack was therefore cancelled. On the left at least, affairs had reached a temporary deadlock, and one phase was ended.

(iv)

Though falling back hastily, the enemy on the left had not been taken off guard; on the right it had been otherwise, and there the fortune of the day swayed uncertainly. During the night of 2–3 December both sides prepared to dispute possession of Orsogna. Dug in a mile outside the town, 24 Battalion was providing the base from which an attack might be launched on the morrow. By 10 p.m. it was strengthened by the arrival of its mortars and anti-tank guns, brought manfully up despite the difficulties of the Roman road, which crossed the Moro in a deep defile. The improvement of this road, which the Germans, with more realism, if less historical sense, called a cart track, was the task of a party from 26 Battalion, which set out after dark. It was a task well worth doing, since on the right our tanks were held up by the demolition beyond Spaccarelli and on the left they were soon to be stayed before Melone.

Between nine and ten o’clock, while these preparations were going on, Parkinson ordered 25 Battalion to attack at dawn through Orsogna. To him the town appeared at most as an intermediate objective, to be overrun in the course of a drive to the final objective, a track a mile to the west, whence the battalion was to exploit to San Martino. Thus at this time Orsogna was to Parkinson what Melone was to Stewart – an early stage of an advance that was expected to sweep far beyond it.

The intentions of these two commanders could not have been stated more succinctly than they were by Lüttwitz, who a few hours earlier had made his appreciation: ‘Now that the enemy’s flanking attack had succeeded in digging the division out of its positions in the Melone–Graniero line, he was expected to attack on 3 December, with main thrusts on Melone and Orsogna, in an attempt to force a break-through at one of these places and prevent us from forming a new line.’ His plan, therefore, was to withdraw to the Melone–Orsogna line and occupy Orsogna in strength.

Even so, no great strength was mustered there overnight, and the report that the New Zealanders were bringing more and more troops into the gullies east and south-east of the town and that tracked vehicles were heard moving about can have been no sedative to the commander of 26 Panzer Division, who understood, as our commanders

25 Battalion Attack on Orsogna, 3 December 1943

did not, how much turned upon the action that the morning would surely bring. By midnight his reconnaissance unit had completed its move into Orsogna. While the survivors of the battalion of 146 Regiment took post outside, the town itself was defended by the reconnaissance unit less one company, together with a company of tanks (including a few flame-thrower tanks) and two 20-millimetre four-barrelled anti-aircraft guns.

Such was the opposition against which 25 Battalion advanced on the morning of 3 December. Leaving its positions at 1.30 a.m., it marched on foot along the Roman road and joined the Lanciano– Orsogna road on Brecciarola ridge, passing through 24 Battalion’s forward positions. At 3.15 Lieutenant-Colonel Morten halted battalion headquarters half a mile from the eastern outskirts of Orsogna and ordered A Company into reserve to dig in. The two remaining companies, in wireless touch with battalion headquarters, deployed on both sides of the road and moved on slowly.

The road into Orsogna (to the military eye) was paved with premonitions, for at every step the defensive possibilities of the town were further unfolded. Brecciarola ridge, dotted with olive trees, vines and grey farm buildings, has a crest which is nowhere wide and which narrows as it climbs towards the town. Here the gentle,

rounded slopes that rise from the Sangro give way to country more deeply gashed by valleys and ravines. To the left of the road, as our men advanced, was a place of plunging gullies, so steep near the town that the buildings appeared to hang on the brink of a precipice. To the right the land fell away less sharply, but the enemy, it was later discovered, had sown it thickly with mines. Manoeuvre was made more difficult by the fact that the houses of the town huddled together on the flat top of the ridge and barely stood aside to allow the road a furtive entry. In this narrow frontal approach lay much of Orsogna’s strength.

By 6.15 the two companies had reached the edge of the town without awakening resistance. Here C Company disposed itself for all-round defence while D Company pushed on through the narrow gateway. No. 17 Platoon on the right and 18 on the left were directed straight through the town, and 16 Platoon was left to clear the enemy out of the buildings.

The leading platoons were more than half-way through the town before battle broke loose. They were then attacked from the rear by an armoured car that drove down the main street into the main square. In attempting to work round the southern side of the town, they came under heavy fire from infantry posts and took refuge in buildings. Here they were trapped by tanks and infantry coming into the town from the west and both platoons were captured complete. This counter-stroke was delivered by a company of tanks and a company and a half of infantry which formed up for attack in spite of shellfire from a troop of our tanks firing at long range. Then, just as three miles away to the south-west the New Zealand infantry attack on Melone had been abandoned, they swept into the town.

In the expectation that our own tanks would arrive, 16 Platoon was instructed to hold on in Orsogna; since they did not arrive, the seven survivors of the platoon chose to make good their escape as the German armour approached. Fired on at short range as they ran, they bolted down a street, threw themselves over a bank at the town’s edge and scrambled down a gully to safety. C Company, having covered this breathless disengagement, itself had to scatter down another gully north of the town, and the crews of three supporting Bren carriers had to abandon them in their haste. By eleven o’clock both of the assaulting companies had withdrawn through 24 Battalion. Twenty-fifth Battalion’s casualties totalled 83 – 4 killed, 26 wounded, and 53 missing, most of the last being prisoners.

Only now, two hours too late, did the first New Zealand tank make an appearance among the forward infantry. As soon as he heard of the unexpected trouble at Orsogna at seven o’clock,

Parkinson, in the absence of other artillery, called on a troop of C Squadron 19 Armoured Regiment to fire in support, and from a position outside Castelfrentano three tanks engaged the Germans approaching Orsogna with their 75-millimetre guns. At the same time, the commander of A Squadron 18 Armoured Regiment was urgently ordered forward. The previous night he had been told not to expect orders before 7.45 on the 3rd, by which time 25 Battalion would be well inside Orsogna. His tanks, harbouring near Route 84 only a few hundred yards north of the Sangro, were eight miles or more from the scene of action, and they arrived to find Orsogna already in the triumphant grip of ardent panzer troops, with German tanks venturing out of the town towards them. One of these they were able to damage and the other to repel.

This was an inessential epilogue; for the contest of manoeuvre had been won and lost. Both at Melone and at Orsogna the Division had been sharply informed that it was no longer possible to scamper through the German defences. Again we may turn for prophecy to the war diary of 26 Panzer Division, under 3 December: ‘Intentions: Fortify and hold positions....’

(v)

In the perspective of the long, grim and futile campaign that followed, the events of 2 and 3 December in and before Orsogna have a wistful significance. They provoke questions. Was an opportunity missed? If so, why was it missed, and what were the consequences?

The facts suggest very strongly that Orsogna might have been taken cheaply at any time between dusk and midnight on 2 December. One battalion, the 25th, was within two miles and a half of Orsogna by three o’clock in the afternoon. Though wet and tired from the Sangro crossing and the climb to Castelfrentano, it had not been in heavy fighting, it had not set out until ten o’clock that morning, and it might reasonably have been asked to advance on Orsogna and put in an attack by dusk or dark. But the battalion was left to dig in, and it was only at ten o’clock that night that it received orders to attack at dawn.

Twenty-fourth Battalion, astride Brecciarola ridge scarcely a mile from the town, was within even closer striking distance as early as 3.30 p.m. Lieutenant-Colonel Conolly was confident that the enemy had been caught off balance and that Orsogna would fall as easily as Castelfrentano. His opinion was confirmed when a German officer that afternoon rode a horse down the road from Orsogna, blissfully unaware that he was among enemies until a New Zealand

rifleman fired at him, whereupon he departed rapidly uphill on foot. Conolly pressed Parkinson to allow the battalion to continue on to the capture of Orsogna, but he was instructed to dig in to provide a firm base for 25 Battalion. Even had it waited for the arrival of its support weapons, 24 Battalion might have been at the gates of Orsogna well before midnight. At any time before midnight, when the last elements of the German reconnaissance unit reached Orsogna, the attacker must have found the defences weak and unorganised. It is highly unlikely that prepared field defences then existed in any strength in and about the town. The spade-work of preceding weeks had been spent upon the Siegfried line, now an object of curious inspection by New Zealand troops.

No one can predict the outcome of a hypothetical attack, but if 25 Battalion (or 24 Battalion) had struck twelve or even seven hours earlier, it seems probable that they could have carried the town and established themselves on its western perimeter. Thence, with artillery support, they would have had excellent command over the counter-attack, and might have proved as difficult to evict as the Germans did once they had taken full possession.

If one opportunity was missed on the 2nd from lateness, was another missed on the 3rd from lack of weight in the attack? Three points are involved. The actual assault on Orsogna was entrusted to a single company of infantry. It was made without armoured support: tanks arrived too late to influence the action. It was made without artillery support: no field guns fired at the call of the infantry in the town. But whether these deficiencies meant the difference between success and failure is a question on which speculation must be very reserved. It is doubtful whether Orsogna, in the grasp of determined defenders, would have fallen to frontal attack by a battalion, even supported by armour and artillery – and no stronger bid could have been made at the time. If there is to be a verdict on the lost opportunity, it is ‘too late’ rather than ‘too little’.

Explanation must begin with a reminder of the buoyant spirits of the main actors. The New Zealand commanders believed the Germans to be on the run. They were quite correct in assuming that the defences which they had overrun around Castelfrentano were part of the enemy’s main winter line; and if he did not stand in them, why should he stand immediately behind, where there was no natural depth and little or no artificial preparation? But the tactics of approaching a town by daylight, sitting down before it all night, and attacking it with inadequate support at dawn next morning could not be repeated with success. Having hit the enemy for six (in the Army Commander’s phrase) at Castelfrentano, the New Zealanders played the same stroke at Orsogna – to a different ball.