Chapter 6: Orsogna Unconquered

I: Operation FLORENCE

(i)

THE fascination which in static warfare a fortress often exerts over the attacker might well have tempted General Freyberg once more to pit his strength against Orsogna. The town had twice defied him, and among commanders he was the last to allow a contretemps to harden into checkmate; but he wisely refused to assault it again from the front. Not Orsogna but a way around Orsogna was the objective of the coming attack.

The divisional orders for operation Florence issued on 14 December proposed a renewal of the advance from the Sfasciata salient to cut the Ortona road and to prevent 26 Panzer Division from moving towards the coast to oppose 5 Corps’ drive. The main task fell to 5 Brigade. Of its three battalions, the 21st was to attack north-west across the ravine north of Sfasciata and seize the ridge beyond, some distance short of the main road; 23 Battalion, advancing more speedily over less broken ground, was directed west along Sfasciata to capture a mile of the road north of the cemetery; and 28 Battalion was to remain in reserve. Once on their objectives, the assaulting battalions were to have the help of the tanks of 18 Regiment in organising against counter-attack and were to seize any opportunity to exploit to the west.

In support of this dash for a bridgehead across the road, 17 Brigade was to move forward south of Poggiofiorito and 6 Brigade was to guard the left flank, with 26 Battalion on Brecciarola and 25 Battalion on Pascuccio joining up with 23 Battalion at the cemetery. Barrages, timed concentrations and counter-battery fire by the artillery during and immediately after the attack, and air bombardment of approaches to the battlefield at dawn, were to help the infantry to reach and hold their objectives. Supporting fire was also ordered from 27 Machine Gun Battalion, whose platoons were reshuffled for the purpose, and the Maoris were to man 5 Brigade’s 4·2-inch mortars.

(ii)

Over 160 guns – heavy, medium and field – opened up at 1 a.m. on the 15th and soon afterwards the infantry moved forward in confusing gloom, for the full moon was obscured by cloud. Bitter cold and showers of rain made the night miserable as well as menacing. On the right, 21 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel McElroy) gained its objectives against appreciable but neither fierce nor very costly resistance. The stormiest passage was on the right, where D Company (Major Bailey) was twice held up by the fire of German posts and had trouble in keeping touch on its flanks. In the centre, A Company (Major Tanner) reached the road, swung right, and captured several enemy posts before digging in at Point 332, where the road topped a rise. Loss of direction and brushes with German machine-gunners delayed B Company (Major Hawkesby)1 for a while, but by about 3.30 it was settled in across the road on A Company’s left.

In its westerly attack along Sfasciata 23 Battalion paid heavier penalties. No sooner had it crossed the start line than it lost men from shellfire, and then it ran into the belt of defensive fire on the narrow neck of land which formed the only route for vehicles on to the road. Casualties were so many that the supply of stretchers gave out and some of the wounded had to wait for more to be brought up. Meanwhile the companies pushed on. First to reach its goal across the road was D Company (Major Ross),2 which was joined in turn by A Company (Second-Lieutenant Edgar)3 on its left, and on its right by B Company (now, since Captain Kirk4 had been wounded, under command of Second-Lieutenant Irving).5 It was a weakened and disorganised battalion that now settled on its objective. In the dark men had strayed from their own platoons and companies; pockets of the enemy overrun on the way forward now started into vicious life by opening fire from the rear and it was hard to tell friend from foe. Before the battalion could consolidate, it had to drive off repeated enemy efforts to breach D Company’s front, and it was under continuous shellfire. Moreover, anxiety was felt for the safety of its left flank. Having lost about 40 per cent of its assaulting strength, the battalion could not extend its left as far as the cemetery and was out of touch with 25 Battalion. A tentative

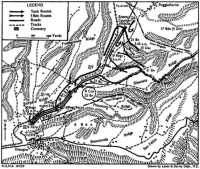

Operation FLORENCE: 5 Brigade’s Attack on 15 December

contact was made after daylight, but it was not until 23 Battalion committed its reserve (C Company) in the area in mid-afternoon that it was possible to stabilise the line near the cemetery.

But ‘at the other side of the hill’ there was no less perturbation. Lieutenant-General Lüttwitz, commanding 26 Panzer Division, was a worried man. He had four battalions in the line between Poggiofiorito and Orsogna, but his one reserve battalion had been withdrawn to stem 5 Corps on the coastal sector and his last tanks had also been ordered east, so that when the New Zealanders attacked he had none between Arielli and Orsogna and had to rely on a strong line of anti-tank guns just behind his forward troops. Nor was the first news very reassuring as it filtered in over severely disrupted communications. The full shock of 5 Brigade’s attack fell on the three companies of II Battalion 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which were walled in by gunfire and then, fighting to the last in a tumult, were almost wiped out by the infantry who followed up. The forward German anti-tank and infantry guns and their crews were badly shaken by the bombardment.

Nevertheless, the enemy responded with such reserves as he could find. A few tanks, called up from Arielli, according to the German

estimate ‘did not go too well in the dark’, but they caused some alarm to the New Zealand infantry as they bore down along the road from the north-east. D Company 21 Battalion was partly scattered, A Company retreated 300 yards behind the road, and most of B Company was temporarily cut off as the tanks moved along the road behind it, firing freely. As yet without anti-tank guns or tank support of their own, the New Zealand infantrymen lay open to the German armour, which swept the forward area with fire until nearly six o’clock, when it withdrew at leisure – and with discreet timing, as it proved, for shortly afterwards the first of 18 Regiment’s tanks appeared. So sustained, the infantry companies used the respite to rally and reoccupy their forward positions. Two or three hours later D Company was again disturbed by a second wave of enemy tanks rumbling down from the north-east, but this time 18 Regiment’s tanks were there to counter-attack, destroy one and drive the rest back.

The arrival of the tanks in close support of the infantry was an important stage in the unfolding of the New Zealand battle plan. It was, too, a victory for perseverance and ingenuity; for memories of Ruweisat and El Mreir completed the determination of the men of 4 Armoured Brigade never to fail the New Zealand infantry. Within an hour of the opening of the attack the twenty-eight tanks of 18 Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Pleasants),6 hitherto concealed on Sfasciata, were struggling painfully in single file along the spur towards the main road. Ahead of them a party of engineers from 7 Field Company cleared mines from the muddy track and each commander guided his tank on foot. The misadventures of C Squadron (Captain Deans),7 which was in the lead, were only too typical of the mingled hazards of enemy interference and of rough, confined ground made treacherous by rain. Of its nine tanks, only one reached the road. One slid off the track where it ran along the brink of a steep hillside; two burned out their clutches; three immobilised themselves in churned mud; two missed the track in the confusion caused by enemy fire. The sole survivor of this luckless cavalcade eventually joined B Company 21 Battalion. A Squadron (Major Dickinson) and B Squadron (Captain K. L. Brown)8 were somewhat more fortunate, though not scatheless. The substantial result of the regiment’s effort was that shortly after dawn each infantry battalion had five tanks in close support and two troops were

in reserve, with perhaps two tanks in the cemetery on the left flank of the bridgehead.

Still, the regiment was now too weak to undertake unaided the task of exploitation towards Orsogna. At 8.30 a.m., therefore, 20 Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel McKergow)9 was ordered to send a squadron to 5 Brigade. The route presented two difficulties which 18 Regiment, having set out from Sfasciata, did not have to overcome. One was the deterioration of the track above the Moro crossing; it was steep and slippery, but the bulldozer at the ford could and did keep it open. The other was that the approach road, especially at the descriptively named ‘Hellfire Corner’, was exposed to enemy observation from Orsogna and Poggiofiorito. These two points had to be blinded by the smoke shells of New Zealand guns, and it was mid-morning before C Squadron (Major Barton),10 fourteen tanks strong, moved off. The smoke cover gave the squadron untroubled passage. Soon after 1 p.m. its two forward troops were on the road with 23 Battalion. By this time the rest of the regiment (less B Squadron), with nineteen tanks, was on the way forward to reinforce the exploitation, masked by smoke already so dense that the gunners had no need to thicken it. Of the thirty-three tanks with which 20 Regiment set out, all but five reached the forward area. So much surer was the going by day.

Insecurity at the boundaries of the two New Zealand brigades was one reason why 18 Regiment had been unable to exploit earlier, as planned. But with the strengthening of this sector and a perceptible slackening of the German fire, Kippenberger at eleven o’clock gave 18 Regiment the command to begin the exploitation with a reconnaissance in force past the cemetery to the western exit from Orsogna. He hoped to catch the Germans off balance while they were still reeling from their losses and before they could mend the gaps in their line; but he urged caution, directing the tanks to avoid heavy fighting. On arrival at the Ortona road, 20 Regiment was to pass through the 18th for the main exploitation, supported, if possible, by two companies of 28 Battalion, which was being brought up from reserve at Castelfrentano. The object was to block the western exit from Orsogna and then to advance south-west to the Melone road fork. Orsogna was not to be directly assaulted unless its defences caved in, but should 20 Regiment enter it from the west 6 Brigade was to be ready to occupy it from the east, and 4 Brigade farther south was to hold itself in readiness

to move at an hour’s notice on Guardiagrele and San Martino.

While the New Zealand command anticipated a loosening up of the defences and a mobile phase of battle, the Germans strove desperately to repair the damage done overnight. By midday the foremost German troops north of the cemetery had withdrawn across the first gully north of the road and were clinging to the next ridge. Holes, one of them a kilometre wide, between the remnants of II Battalion 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment and its two neighbours, had been filled by troops hastily scraped together, and the bending back of the line had enabled a continuous, if none too solid, front to be restored. The Corps Commander himself was on the spot, hustling all possible anti-tank guns up from the rear to fight the troublesome New Zealand tanks on the road.

Such, in brief, was the situation when, in the early afternoon, Major Dickinson set out with six of 18 Regiment’s tanks along the road towards the cemetery. A few track-lengths beyond it, the leading tank was set aflame by a direct hit from an anti-tank gun. The road forward, save where it dipped into a shallow valley, was open to fire from Orsogna as well as from guns dug in among the olive trees on the right. The remaining tanks therefore took cover behind the high stucco walls that bounded the cemetery, where they replied in kind to the German machine-gun fire.

The main exploitation, by 20 Regiment, began about two hours later under cover of a smoke screen, with C Squadron leading the way. As soon as the first three tanks moved clear of the cemetery they fell to the same anti-tank gun that had already destroyed the 18 Regiment tank, two of them catching fire and one losing a track. The rest of the squadron continued to advance along an avenue of anti-tank and infantry posts, most of them sited in olive groves north of the road. When they reached the crest of the road several hundred yards due north of Orsogna, having broken through the right wing of II Battalion 146 Regiment, they were halted by the frontal fire of three German Mark IV tanks. Two of these were knocked out, but C Squadron lost another of its own in the encounter and a fifth which became stuck in trying to cross the railway line and had to be abandoned. With only eight tanks left, with no immediate prospect of the much-needed infantry support and with failing light to hinder it, the squadron was allowed to pull back to the cemetery. The withdrawal cost yet another tank, damaged by shellfire and abandoned. Fifty men from 23 Battalion, organised by Captain Grant,11 gave prompt infantry protection to the tank laager.

The party was relieved by the first of the Maoris to arrive. Twenty-eighth Battalion had marched in stages the weary, muddy miles from well beyond the Moro ford. B and C Companies on arrival threw an arc of defensive posts around the cemetery, while A and D Companies, coming up before midnight, dug in below the road east of the cemetery, ready to exploit westwards next morning.

(iii)

At this point, with Fairbrother and McKergow planning the morrow’s attack, we may pause to take stock. Fifth Brigade, securely established across the main road for a mile of its length, had driven a shallow salient into the enemy’s FDLs. Its right flank, though not wholly firm, was buttressed by 17 Brigade, which had battalions investing Poggiofiorito from both north and south. After the confused scrimmage of the morning, when 23 and 25 Battalions failed to link up satisfactorily and Germans and New Zealanders were intermingled in errant groups, the brigade’s left flank was held by a connected line of troops. In the sector round the cemetery both sides had been at sixes and sevens. Thirty-six mobile tanks were in support – 13 of 18 Regiment in the north, ready to exploit towards Arielli and Poggiofiorito, and 23 of 20 Regiment in the cemetery area, under orders to advance again towards Orsogna in the morning. A semi-circle of defensive fire tasks gave further protection. Communications were working well. At the Moro the bulldozer – the most important single vehicle in the Division – was dragging more six-pounders across the ford, as well as speeding the transit of ammunition, supply and medical vehicles. More than a hundred prisoners had been taken. Three of the enemy’s none-too-numerous tanks had been put out of action and five of his anti-tank guns captured.

On the other hand, the brigade had exhausted nearly all its reserves. In fact, two platoons of 21 Battalion were the only infantry not in the line or about to be committed. The tanks were running short of fuel and ammunition, for the state of the tracks made it impossible to maintain reserve supplies on Sfasciata, and there was concern over ammunition for the 25-pounders. Moreover, casualties in men and machines had been punitive, though not prohibitive. Twenty-third Battalion, about 130 under establishment when the battle began, had lost another hundred in killed and wounded, and 21 Battalion, hardly less under strength, had lost about thirty. Since these losses were almost entirely in the rifle companies, fighting strength was more than proportionately diminished. Enemy fire or ground hazards had put twenty-five Shermans out of the fight,

though three were to be recovered the next day. The two armoured regiments had also lost nearly thirty men killed and wounded. Among the casualties were two commanding officers – Lieutenant-Colonel Pleasants of the 18th (wounded) and Lieutenant-Colonel Romans of the 23rd, who died of wounds.

Despite these setbacks hopes were buoyant at Divisional Headquarters that night. The enemy was believed to be groggy and about to depart. Freyberg had a cheerful appreciation for Montgomery: Orsogna seemed ripe to fall and then the chase would be on towards Filetto and San Martino. For this purpose 6 Brigade was detailed as advance guard.

Such thoughts were far from the mind of the German command. There was no disposition to underrate the bitterness of the fighting. Lieutenant-Colonel Berger, commanding 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, left this record of the day:

15 December had seen the regiment committed to the very last man. It had lost heavily in men and equipment. A large number of men were missing and it was considered that the vast majority must be killed or wounded, as they had stuck to their guns for hours under terrible shellfire and had shot away all their ammunition. We had no men to pick up the dead and wounded, even if the fire had permitted it. ...

The presence of the New Zealand tanks on the Ortona road roused alarm at all levels up to the highest, bringing Kesselring himself to the telephone with exhortations to employ every possible gun against the armour. Local counter-moves included the transfer of a company of mountain troops from 65 Division and of engineers to help seal off the New Zealand penetration; but this was not enough. Since 26 Panzer Division’s plight was now officially pronounced worse than that of its neighbouring division on the coast, it was given first claim on the services of 6 Parachute Regiment, coming up from Army reserve.

Long before the paratroops could arrive the armoured thrust towards Orsogna had been beaten off and the Germans considered they had survived the crisis. The time had come, in fact, for a counter-attack, for Herr was adamant that it must not be delayed until next day, lest the New Zealanders should expand their bridgehead in both directions, north and south. To throw the paratroops into the counter-attack at the end of a long journey was not ideal and their committal would use up the Corps’ last reserves, but these were disadvantages that had to be accepted. Orders were therefore issued for an attack from the southern edge of Arielli not later than 11 p.m. to restore 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment’s old line. Eleven o’clock had come and gone when the first troops of 6 Parachute Regiment arrived after a long, tiring journey over wretched roads, and the attack could not be launched until 3.15 a.m. on the 16th.

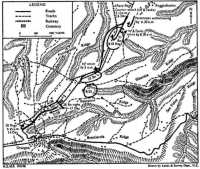

Operation FLORENCE: Attacks and Counter-Attacks on 16 December

(iv)

At that hour two battalions of paratroops, one on each side of the road, advanced with an escort of four Mark IV or Mark IV Special tanks, five or possibly more Mark III flame-throwers and three Italian assault guns, and under an umbrella of heavy artillery fire. For a while they went unchallenged, though the New Zealanders had notice of their approach in the noise of troop movement and simultaneous shelling and machine-gunning. The right-hand battalion, crossing 21 Battalion’s front, closed to within a few hundred yards of the cemetery before encountering 23 Battalion’s right. In the ensuing fighting the attackers, unaided by tanks, could make no headway against the fire of infantry weapons, the machine guns of 20 Regiment’s tanks and the artillery concentrations. By 5 a.m. 23 Battalion, with three killed and three wounded, had cleared its front.

On 21 Battalion’s front the engagement was fiercer, more spectacular and more prolonged. At first the German paratroops and tanks co-operated well. From the Arielli turn-off they advanced a kilometre or more, but as soon as they touched off the waiting

opposition chaos ruled the scene. As the tanks approached A Company’s position firing vigorously, the New Zealand weapons opened up. The two leading Mark IV tanks were hit and left blocking the road. The flame-throwing tanks, following up, were brought to a standstill and sought escape from the inferno of close-range tank and infantry fire either by withdrawing or by plunging south off the road among the lanes and farm buildings, where they shot curling billows of flame and smoke at likely targets.

There was now no pretence of cohesion in the German attack: the infantry had to fend for themselves and the tanks were exposed to the darting tactics of tank-hunting parties. The defensive fire of the New Zealand artillery, renewed and re-renewed almost a score of times, made terrible massacre among the paratroops. The tanks of 18 Regiment sprayed the area with machine-gun fire and when the Germans tried to infiltrate between A and D Companies, and later between the battalion’s right flank and 17 Brigade, they were sent to ground or dispersed in disorder by artillery, tank and small-arms fire. Though at the peak of the fighting, when the infantry were at close grips, 21 Battalion urgently asked 18 Regiment to send more tanks, those already in support were masters of the field and had broken the back of the counter-attack before the reinforcements appeared. The approach over the rise at Point 332 favoured tanks sited defensively, and in the bright moonlight the gunners could see a target with comparative ease at 300 yards.

In the face of such spirited defence, the enemy’s effort gradually flagged. As light began to break a second armoured thrust came in down the road, but the leading tank was again destroyed and blocked the road, and the improvised covering party of engineers melted away to safer places, while the regular infantry stayed in their holes. Before 6.30 a.m. the paratroops had admitted defeat. They were withdrawing, with their wounded, towards Poggiofiorito under a hail of fire. So far from restoring the old line, as they at first claimed, they had to be content to fall back as reinforcements on the new, makeshift line of 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment. At 8.30 the last of the tank commanders gave the order to retire to Arielli in small groups at long intervals.

While the action cost 21 Battalion five killed and fifteen wounded, the Germans left nearly fifty dead behind, some of them only a few yards from the battalion’s positions. Among the four German tanks destroyed, two were flame-throwers. These weapons had proved of dubious value to the attackers. One German subaltern wrote for senior eyes a romancing report of enemy infantry scorched out of their trenches and of enemy tanks stalked, surprised and set ablaze, but the happily prosaic fact is that the 150 roaring orange

jets of flame of which he boasted were one and all misdirected and harmless.

(v)

As the enemy’s hostility spent itself and his pressure on the right wing of the New Zealand salient relaxed, the hour came for the drive to the left towards Orsogna and Melone which, it was hoped, would release the coiled energies of 6 Brigade. The detailed plans for this attack had been laid the night before by Fairbrother and McKergow in the discomfort of the battle-swept cemetery. Two squadrons of 20 Regiment’s tanks were to advance at 7 a.m. on either side of the road – A Squadron (Major Phillips)12 on the right, C Squadron (Major Barton) on the left – followed at an interval of three or four hundred yards by 28 Battalion’s A Company and D Company respectively. The other infantry companies were to give covering fire. The German counter-attacks during the night enabled the nineteen tanks at the cemetery to move on to firmer ground in comparative stealth but also raised doubts whether the attack should go on. Kippenberger, confident that the German effort would be beaten off, gave the word to proceed. Hence for a while attack and counter-attack overlapped, with New Zealanders and Germans a few hundred yards apart, both attempting to advance south-west along the Ortona road.

Once out of the shelter of the cemetery, the New Zealand armour was in sore trouble. The road to Orsogna suddenly became a bubbling, steaming cauldron of shellbursts, throwing up lethal fountains; overhead the sky was pocked with the grey puffs of air-bursting shells and rang with the wicked crack of their explosions as they rained down hot metal; and the strengthened line of German anti-tank guns fired furiously. The infantry, driven to cover, lost touch with the tanks and never regained it during the action. C Squadron moved on unaccompanied, strung out in line ahead along the road. North of the road German anti-tank gunners, concealed among the olives, had the squadron in enfilade, and as the tanks neared Orsogna they came within range of weapons in the town. Raked by this double fire, they could do little, and though they fought back at the anti-tank guns they offered a target rather than a threat. Two were hit and set on fire just beyond the cemetery. Another went up in flames farther along the road and a fourth had to be abandoned after being hit twice. The crews of the last two fell captive in trying to make their way back to the cemetery on foot.

No kinder fate awaited A Squadron, part of which, advancing on the right along the railway line, made a bid to take the anti-tank

defences in the flank or from the rear. The leaders were thrown into such confusion that no concerted effort was possible and, since the incessant shellfire forbade successful reconnaissance, the anti-tank guns could not be located. The tale of tanks destroyed mounted – one, two, three, and finally four. The Maoris of A and D Companies tried, in support of A Squadron, to close with the German gunners, but they were thwarted both by enemy observation and covering fire and by the skilful camouflaging of the guns, and the platoons were scattered in the attempt.

One tank managed to run the gauntlet as far as a bend in the road only two or three hundred yards north-west of Orsogna: the gesture was magnificent, but it was not effective war. It was necessary to reunite tanks and infantry, and since the infantry could not come forward the tanks had to go back. At ten o’clock Kippenberger gave the order for such a reunion, but on second thoughts instructed the tanks to withdraw right behind 28 Battalion, for it was now obvious that few gains were to be made west of the cemetery. The two squadrons turned and made their way back before the prearranged smoke screen could be laid and the withdrawal cost another tank. By noon the two forward infantry companies had straggled back to battalion headquarters area, leaving B and C Companies dug in round the cemetery, which was steadily and destructively shelled all day. Though ordered to do so by day if possible, B and C Companies had to wait for the merciful dusk before retiring a few hundred yards behind the cemetery to positions on the railway line and astride the road and in touch with 23 and 25 Battalions on the flanks.

(vi)

Once again a plan to exploit success had gone amiss. The New Zealanders’ attack broke on the same rock as that which had destroyed the Germans’ – the failure of the men on tracks and the men on foot to think as one, to act in close mutual support and to strike with united force. Liaison was made difficult by the breakdown of the wireless link and perhaps by the absence of an artillery barrage to protect the follow-up of the infantry: the tank commander had not wanted one and 25-pounder ammunition was scarce. The tanks were unable to manoeuvre freely; the anti-tank defences had been thickened up at the urgent behest of the higher German command and they were sturdily manned. Between them the two units had lost ten killed, over thirty wounded, and four prisoners. With ten casualties that morning, 20 Regiment left behind fifteen tanks destroyed or damaged to give practice to the German gunners, who systematically shelled them until they were beyond repair.

Yet all was not debit in the account of operation Florence. The enemy, never flush in men and equipment, had suffered heavily in both, and he had given ground on a defensive line that had always wanted depth. Dented by the armoured thrust, his line, while still embracing Orsogna, had been pulled back north of it to the next ridge beyond the main road, and the New Zealanders’ firm grasp of the road gave them a jumping-off point for further attempts to turn Orsogna from the north. The German Corps Commander, indeed, was already contemplating a fighting retreat to the line of the Foro River, five miles to the rear; but at the same time he was instructing his divisions to remain in the existing line until forced out of it, to contest every inch of ground, and not to withdraw without imposing such delay and taking such forfeits from the enemy that he would have to pause before assaulting the Foro. Meanwhile, he was confident enough to announce no more counter-attacks. And the truth was that for the time being the New Zealanders had been fought to a standstill. Late on the 16th, 26 Panzer Division made an accurate appreciation: ‘The enemy’s success yesterday and to-day in the Orsogna area had cost him heavily, and so he was not expected to attack again in the meantime, even though our withdrawal had left the road open for him’.

(vii)

It was a pause of several days that preceded the next and (as it proved) the last major effort by the Division at Orsogna – but it was hardly a lull. For while readjustment and recuperation were necessary, relaxation was not possible. A first readjustment – one of command – occurred in the midst of the battle. At 6 a.m. on the 15th the Division passed from Army to 13 Corps, which, with 5 British Division also under command, assumed responsibility for the sector from Orsogna eastwards. Consequently, Corps took over command of 6 Army Group, Royal Artillery, from the New Zealanders. Fifth Division completed its move into the line on the New Zealanders’ right on the night of 15–16 December and as soon as the German counter-attacks that night had died down 17 Brigade reverted to its own division. The New Zealand Division, however, preserved something of the international flavour that was typical of the Allied cause in Italy, since it retained command of a brigade of British paratroops, a regiment of British field gunners, three squadrons of Canadian sappers and a company of Italian muleteers.

For the hard-pressed 23 Battalion, now tired and dangerously depleted, rest was imperative. On the evening of the 16th its companies left the line for the Castelfrentano area, and 28 Battalion relieved it by extending D Company to the right to link up with

21 Battalion. Of the two armoured regiments forward with the infantry, the 18th was now to support 21 Battalion and the 20th 28 Battalion. Using tanks and carriers as load vehicles, the two regiments replenished their fuel and ammunition. The track from the Moro crossing to the crest of Sfasciata remained a weak link in the chain of supply; it needed the constant attention of bulldozers and its use had to be severely restricted. The arrival of 37,000 rounds of 25-pounder and 4000 of medium ammunition lifted a worry from the minds of the gunners and permitted them to replace the heavy expenditure of the two previous days.

Though the Divisional Commander did not plan an immediate return to the offensive, neither did he expect a stalemate. He was still hopeful that the enemy would fall back from a sense of prudence, and on the 17th thought it a matter of hours before the enemy quitted Orsogna, but he would not risk heavy casualties in the meantime. The German command, on the other hand, while preparing a line of last resort on the Foro, was content to fight stiff delaying actions on its existing line and to remain there if allowed. The Germans were thus willing to sell ground, but only at a price the New Zealanders were not willing to pay. The discovery of this fact gives tactical meaning to the operations of the Division in the following few days, which must now be summarised.

(viii)

For the two forward battalions of 5 Brigade, the night of 16–17 December was disturbed by the sound of enemy movement and digging and by the defensive artillery fire that was brought down on likely enemy forming-up places; but the real cause of the alarm was probably the relief of 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment by 6 Parachute Regiment. Reports next morning suggested a general German withdrawal. British troops were out of touch with the enemy on certain parts of the Corps’ front; reconnaissance patrols of 21 Battalion found the area empty for 500 yards forward of their line; and 2 Battalion Northamptonshire Regiment, the flanking unit of 5 Division, believed that the Germans had left Poggiofiorito. All along the Division’s front, then, the 17th brought probing movements to ‘test the market’. They were to show that it was as firm as ever.

On the right, a reconnaissance force of 18 Regiment’s tanks and a platoon of 21 Battalion was diverted from Poggiofiorito, which had already been peacefully occupied by men of the Northamptonshire Regiment, to explore the road to Arielli with instructions not to go beyond the village or to persist against opposition. In a sharp encounter on the outskirts of Arielli the leading tank stirred up a hornets’ nest. From an exchange of fire with an anti-tank post

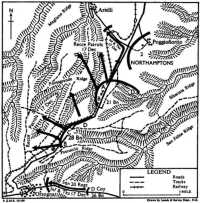

5 Brigade Patrols, 17 December

among the houses they returned minus two tanks, which had been bogged, with a third hit but recovered by the driver, and with the satisfaction of having destroyed the chief trouble-maker, an 88-millimetre gun. The evidence of patrols that the enemy had withdrawn beyond the Arielli stream, 800 or 1000 yards west of the main road, on 21 Battalion’s front seemed to be confirmed farther south by the findings of patrols sent out by the Maoris. Four Maori patrols west of the main road went unaccosted, but two which were sent out in the evening to harass the movement of traffic were sent home by mortar and machine-gun fire before they could reach their destination.

One more trial of the German strength in the town of Orsogna was made on the 17th. That it was lightly held was a reasonable inference from the reports of overnight patrols; but the hostile reception accorded that day to two platoons of 26 Battalion and two troops of 20 Regiment which tried to enter the town reversed

expectations. Approaching from the east along the causeway of the Lanciano road, the attackers soon lost contact and cohesion and the attack momentum. While the infantry worked forward towards Orsogna, the tanks halted at the demolition for fear of mines and the engineers were hampered by shellfire in trying to sweep a path. One mischance followed another. The platoons stumbled into a thick minefield; the commander of the leading troop, separated from the sappers, pushed on to the outskirts of the town, where one of his tank tracks was blown off; later, after the tank had been hit, the crew were machine-gunned as they climbed out and the rescuing tank had itself to be recovered from a bog by the third tank of the troop. The fire from Orsogna was too violent for the infantry to hope for further progress and it was decided to retire at nightfall. The tanks stayed forward to bring back the wounded, but in doing so one was set on fire by a mortar bomb. During the night the two derelict tanks were blown up by the Germans before New Zealand patrols could picket them.

Farther west, 4 Armoured Brigade and 2 Parachute Brigade were put on the alert to take advantage of any German weakening. A warning order to 19 Regiment and 22 Battalion to advance towards Guardiagrele along the northern lateral road was cancelled when it became obvious that the bid for Orsogna had failed. The Divisional Cavalry, given their first task for a week, patrolled the southern lateral, which they found blown at one point and from which they saw enemy movement. Confirmation that the enemy was still anxious to defend the approaches to Guardiagrele was forthcoming from the paratroops: a platoon of them sent to the road junction at Melone recoiled before heavy fire.

Ahead of 5 Brigade lay a closely cultivated area known as Fontegrande, flat to the distant glance but in fact wrinkled into a succession of ridges by the headwater gullies of the Arielli stream. These spurs, running parallel with the Ortona road, formed, as it were, the north-eastern spokes of the wheel that had high Orsogna as its hub. As we have seen, it was thought that the enemy had withdrawn to the second of the ridges, which lay behind the stream, but daylight patrols by the two battalions on the foggy morning of the 18th, all three of which drew a brisk fusillade from the wide-awake defenders, indicated that the Germans were holding ground forward of the main stream on the first ridge, with their FDLs probably on a track leading along it to the village of Arielli.

Against the protests of Brigadier Kippenberger, who rightly suspected that the feature was tenanted by fresh and ardent paratroops, General Dempsey, on a visit from Corps, maintained his opinion that it could be occupied without fighting and ordered an

attempt to be made that night. The task was given to three patrols, each twelve strong, who were to advance silently without artillery preparation to establish a line of pickets on the ridge, after which they would be reinforced. The right-hand patrol, from C Company 21 Battalion, made its objective safely, only to find three enemy machine guns sited less than 100 yards away. Calling down gunfire to block the Germans’ retreat, the patrol moved to the attack, but the Germans were lying in wait and opened fire, wounding the officer. The route back was found to be held also by enemy posts, and the patrol, now without either officer or sergeant, had to fight its way home. The centre patrol, from the Maoris’ D Company, was no sooner on the track running along the ridge than it became the target for at least four machine guns dug in around it. Hand grenades were thrown in the fracas that followed, but there was no question of dislodging the enemy, who, on the contrary, hunted the patrol back to its own lines after wounding several members of it. The other Maori patrol, from C Company, was lucky enough to avoid being surrounded. While still short of its objective, it was fired on and it fell back before the all-too-obvious strength of the defence.

This ill-judged enterprise cost one officer killed, one sergeant wounded and missing, and seven other ranks killed, wounded or missing, and gave the enemy the maps and papers found on the dead officer. It served only to show that the Germans were in fact where they had been expected and to deepen the suspicion (not confirmed until Christmas Eve) that in this sector the New Zealanders were opposed by paratroops.

(ix)

After a month’s battle experience some concern was being felt in the Division at the rate of casualties among the tanks. On the 17th it was reported to Divisional Headquarters that the Division had forty-six tanks out of action through mechanical defects or bogging but still recoverable, and that of those actually lost only ten had been replaced. ‘We are losing tanks in every action,’ commented Brigadier Stewart. ‘Well,’ replied the General, ‘it is a desperate show’. With its tanks badly in need of maintenance and not fit for much movement, the apprehensions of 18 Regiment were by no means allayed by the General’s decision to make its thirteen mobile tanks available to 17 Brigade in a stationary anti-tank role covering its new positions on the Ortona road. Twentieth Regiment was also affected, having to despatch five tanks to 21 Battalion to replace those of the 18th. After a few uneventful days under command of 5 Division, 18 Regiment’s task was taken over by anti-tank

guns and the regiment reverted to 4 Brigade’s command and began to reorganise near Castelfrentano. It was also possible, by strengthening the anti-tank guns forward with the infantry and by laying minefields, to give relief to one squadron and regimental headquarters of 20 Regiment. Some measure of relief was secured for the infantry of 6 Brigade. As the first move in a scheme to give each battalion six days in the line and three days’ rest at Castelfrentano, 24 Battalion relieved 26 Battalion as the brigade’s forward unit on the 18th and 25 Battalion rearranged itself in the San Felice area to give added depth to the brigade’s defences.

During these dull, overcast days the burden of the offensive on the Army’s front was borne by the Indians and Canadians of 5 Corps, who by a series of premeditated blows were slowly drawing near to Ortona. It was no part of the Division’s policy to let the enemy take his ease, but for the time being there were limited ways of keeping him disturbed. Low cloud saved Orsogna and the enemy gun positions from the full malice of our bombers, but raids were made on most days and on the 22nd bombs caused heavy casualties in a newly-arrived battalion defending the town. The Germans wrote in professional admiration of the perfect co-operation of artillery and air force. The guns fired green smoke just forward of the German positions, and the smoke was followed immediately by the raiders, who dropped their bombs accurately on the defences. On the ground the spasmodic play of artillery harassed the enemy, and infantry patrols continued to probe to the line of resistance. Reports that Arielli had been evacuated were shown to be premature, and a Divisional Cavalry thrust in that direction had to be cut short. Patrols of 5 Brigade prowled and listened, but were unable to discover any German withdrawal. By a kind of tacit agreement the cemetery was left vacant by both sides; being marked on the map, it was especially liable to predicted shellfire. Sixth Brigade trailed its coat before Orsogna, eliciting fire and the information that the town was still held. All this time 2 Parachute Brigade had been patrolling actively in the wide, open spaces on the left flank, where its comings and goings were occasionally varied by clashes with small parties of Germans. One night the paratroops found Melone road fork clear, but when a troop of the Divisional Cavalry’s Staghounds reconnoitred to within a hundred yards of the fork next morning the outing was curtailed by a prompt burst of shelling and machine-gunning.

With bitter fighting in the streets of Ortona and Villa Grande farther east, the stubbornness of the enemy was now made manifest. It was obvious (to use language that passed muster with Montgomery’s men) that the Germans, so far from declaring their innings closed on the Ortona–Orsogna line, had every intention of

batting on – particularly since the weather could be confidently expected to handicap the attack more and more. It is true that as late as the 20th General Freyberg was still hopeful that Orsogna would fall without a push; but it was necessary to proceed on the assumption that it would not, and Freyberg’s continued preference was for a circling move ‘north about’ with the Division’s right. This in turn called for the construction of a route ‘to take up the wheels to maintain two brigades’.

From the 18th, therefore, 7 Field Company worked with a will, not merely on improving the track on the 5 Brigade axis but on converting it into a metalled two-way road for use in any weather. The stretch from Spaccarelli village to the Moro became ‘Armstrong’s Road’, and thence up the steep face of Sfasciata and along the spur to the Ortona road ran ‘Duncan’s Road’. Between them, to span the Moro beside Askin bridge, the engineers erected a Class 30 Bailey bridge, first named Tiko Tiko and then Hongi to avoid confusion with Tiki bridge. Reinforcements of Canadian sappers were sent up as well as detachments of infantry to wield pick and shovel, all the available bulldozers were engaged and double shifts were worked. At the height of activity 1000 tons of gravel were being scooped from the quarry, transported, and laid on the road each day. The Divisional Commander took a keen and well-rewarded interest in the road, which he hoped eventually to push through to Arielli. He looked to it to save hundreds of lives by allowing Orsogna to be by-passed.

II: Operation ULYSSES

(i)

‘If you can make roads like that, they can’t stop you,’ Dempsey told Freyberg. But pressure could not be relaxed while the road was being completed. No doubt the original Allied plan of a converging movement on Rome, with the Fifth Army approaching from the south and the Eighth Army along the passes from the north-east, was now incapable of fulfilment as the Italian winter deepened. But the need was as pressing as ever to employ Italy – Churchill’s ‘Third Front’ – as a magnet to draw away forces from the First Front in Russia and the Second Front, which was already a strategic reality, if not a military fact, in the West. Translated into tactical terms of time and place, this need meant that the Eighth Army, already jabbing strongly with its right, would have to bring its left into play again as soon as possible, though skies were murky and the legs of tired infantrymen leaden in the clogging mud.

The fortunes of the mere platoon, often (it may seem) thrown senselessly into battle, must be continually refocused against a background of grand strategy – a task much easier in the retrospect of the historian than it was to the men who, half-blind to the higher issues, fought from the habit of discipline and self-respect and builded better than they knew.

Montgomery planned to reach the Arielli stream throughout its length by 24 December. The policy of 13 Corps, as stated by Dempsey on the 21st, was to clear Arielli with 5 Division so that the New Zealand Division, with a secure right flank, might turn south-west to roll up the German defences. A corps operation order of the 22nd fixed 5 Division’s attack for next afternoon and the New Zealanders’ for 4 a.m. on the 24th. The tactical purpose of operation ULYSSES was to split the enemy at the boundary between 26 Panzer Division and 65 Infantry Division and to turn the Orsogna defences from the north.

The assault was again entrusted to 5 Brigade, which, strengthened by 26 Battalion, was to advance with three battalions from the Ortona road to seize both ridges in the Fontegrande area. Thence it was to exploit with tanks and infantry north-west and west for a mile or more across another system of watercourses to the two ridges known as Feuduccio and San Basile. Twenty-first Battalion on the right and 26th in the centre were both given stretches of the first and second Fontegrande ridges as intermediate and final objectives respectively, whereas 28 Battalion was to take its objective, the important ridge junction north of Orsogna, in one bound.

Artillery support was on a lavish scale – 272 guns, including those of 5 Division and 6 Army Group, Royal Artillery, for 3500 yards of front, or a gun for every 12 or 13 yards. The field guns were to fire a creeping barrage, finishing with smoke to screen the exploitation, while the mediums were to bring down concentrations ahead of the objectives. After dawn Orsogna and the approach roads would be bombed. From its position on Brecciarola 6 Brigade was to help with the fire of its Vickers machine guns and mortars and was to be prepared to send a battalion into Orsogna if the Germans left the town.

The role of the armour was partly protection, partly exploitation. Twentieth Regiment, under command of 5 Brigade, allocated one squadron to 21 and 26 Battalions and another to 28 Battalion, with orders to support the infantry on their objectives and drive beyond them if possible. Should 5 Brigade succeed and the battle become mobile, the break-through would be carried out mainly by an armoured force of 19 Regiment and part of 22 Battalion, directed either through or around Orsogna to Filetto and beyond, and south to

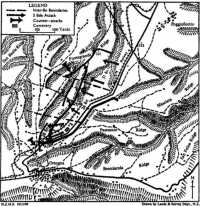

Operation ULYSSES: 5 Brigade Attack on 24 December

link up with the British paratroops at Melone as one stage on the road to Guardiagrele. These paratroops would be assisted by a squadron of 18 Regiment, and they and the Divisional Cavalry were to be ready to lend weight to the exploitation to Filetto.

Such plans time showed to be superfluous, for operation ULYSSES began in doubt and ended in deadlock. The opening circumstances were far from happy. Though not exactly in low spirits, many of the troops were jaded after more than a month of hard and comfortless fighting with few and short periods of rest, and there was some bewilderment among officers as well as men that the offensive was being pressed so relentlessly when the common-sense course seemed to be to settle down for the winter. Regrouping for the attack necessitated some fatiguing moves by night, in particular that of 26 Battalion, which had an arduous approach march of several miles. It arrived weary to attack in the dark under a strange command

over ground it had never seen. The night itself was cold, wet and misty and was not made any more cheerful by the thought that it was Christmas Eve. Though four or five hundred reinforcements had reached the Division a few days before, all three assaulting battalions were seriously under strength, the Maoris having only about 630 men out of an establishment of 800 and no battalion more than 670. In 21 Battalion, when zero hour drew near, fifteen men of one platoon refused to heed the call to action – a grim example of indiscipline without precedent in the Division’s history.

There were also tactical worries. Since 21 Battalion’s right flank was bent back, the barrage had to wheel slightly to the left and the infantry commanders’ task of keeping up behind it was more difficult than usual. The two battalions on the right had a more northerly axis of advance than the Maoris, so that paths diverged. The 21st was concerned about a rough gully that lay across its advance and was disturbed about its right flank. The British division’s attack on the afternoon of the 23rd was reported to have taken all its objectives – Arielli was found that night to be deserted – but its left wing had not come forward, as arranged, to the stream bed on 21 Battalion’s right, and the battalion went into battle with one eye cast anxiously over its shoulder.

(ii)

The unfamiliarity of some of the troops with the ground, its broken nature and the need to make detours, as well as the proximity in some strength of the defenders, made the attack unusually confused. D Company (Major Bailey), one of 21 Battalion’s leading companies, clambered across a gully in the wake of the barrage, clearing German infantry posts en route to its objective, Point 331, on the first ridge, which it reached in little more than an hour. A Company (Major Tanner), going in on the left to share the first objective, was thrown into disorder on the start line by short rounds in the barrage and was more than an hour late in going forward. When it did so, it lost direction in crossing the gully, veering to the right; and when it had gained the ridge beside D Company, it had to work its way back south-west against frontal fire from German posts in houses as well as fire from the north across the Arielli. However, it made its ground on the first ridge and there dug in. The capture of the second ridge had been the assignment of B and C Companies (Majors Hawkesby and Abbott13), but B Company was held back temporarily to cover the tender right flank. C Company, instead of plunging straight across the troublesome

gully in front of it, was sent round its head through 26 Battalion on the left. Hence it crossed the Arielli stream and made a lodgment on a spur beyond. Attempts to clear the spur failed, for the crest was swept by machine-gun fire, and the company had to dig in on the reverse slope. The first objective, slightly to the rear, was not very securely held, but B Company sent up two platoons which, after straying somewhat, eventually came in to bolster the line between D and A Companies. The battalion now had three companies side by side on the first objective, and the fourth with a foothold on the final objective but without much prospect of further advance.

Twenty-sixth Battalion’s plan also provided for a two-company attack on the first objective, with the other two companies to pass through to the second. D and C Companies (Major Molineaux14 and Captain J. R. Williams15), leading the way, became separated in the dark, but both reached the track which was their destination and there managed to assemble most of their men. B and A Companies (Major Smith16 and Captain Piper17) set off behind the leaders but were soon ‘out of the picture’ because of faulty wireless communication. A Company appears to have swung to the left of the route followed by C Company. When it was finally halted by machine-gun and shellfire and consolidated, it found itself on the same ridge and to the left. How B Company found its way forward remains, like much else in this action, wrapped in obscurity. For two hours and a half it was out of touch with the rest of the battalion, and when it regained touch with battalion headquarters it had lost its commander, was digging in on the reverse slope of the same spur as that occupied by C Company 21 Battalion, and was uncertain where it was. The one certainty was the unremitting hostility of the enemy machine-gunners. Before 8 a.m. the two companies of New Zealanders were in contact on this fire-swept and all-but-beleaguered slope, which alone had been wrung from the defenders of the final objective.

A hard, slogging effort by the Maoris of 28 Battalion (Major Young)18 on the left won a considerable success in the task of seizing the tableland, north of Orsogna and south-west of the cemetery, formed by the junction of the gullies. At least partial command of this plateau was tactically indispensable because it gave access to the tracks leading northward along the Fontegrande spurs,

where the infantry listened hopefully for the clatter of approaching Shermans.

D Company (Captain Matehaere),19 with the dual role of right-flank guard and mopping-up company, had to fight its way forward, clearing German infantry posts from its path. Before it could cross the head of the Arielli to reach its objective, it was held up and dug in along the line of the stream beside 26 Battalion’s left-hand company. Meanwhile, in the centre of the Maori Battalion, the progress of B Company (Major Sorensen) was being hotly disputed among the olive groves a few hundred yards west of the cemetery. It, too, found itself checked as it reached the edge of the stream. On the left A Company (Captain Henare) had to battle its way slowly down the main road and the railway line. It succeeded in capturing the junction of the road with the track leading along the first Fontegrande ridge, but just failed to reach a second turn-off leading to Arielli by way of the second ridge and the feature known as Magliano. Indeed, the later stages of the company’s advance were made possible only by the fire of all available arms – artillery, mortars (including 24 Battalion’s) and Vickers guns – on to German resistance north-west of Orsogna, and smoke had to be fired to screen the company while it dug in.

The Maoris had thus worked their two right-hand companies, firmly linked, to within 300 yards of their objectives, and A Company, though still disorganised, was only 150 yards short of its goal on the left. At all points the battalion was hard up against the enemy defences.

For the infantry entrenched along the first ridge, even more for the eighty or so men thrust forward beyond the Arielli in the lee of the second, armoured help could not come too soon. The tanks of A Squadron 20 Regiment lost no time in following 28 Battalion into the area west of the cemetery, and though gunfire, mines and mud disabled four of them, the squadron manned all its tanks (disabled or not) in helping the Maoris to consolidate. The half of B Squadron under Captain Abbott,20 ordered to assist 21 and 26 Battalions, made a successful foray along the ridge, and by noon seven of its tanks were deployed in lively support of the two battalions. Their dash gave a heartening touch to a day that was dour and cheerless.

For the hopes of carrying out the plan of exploitation by 4 Brigade gradually ebbed away. About daylight it was decided that bad weather and the insecurity of the infantry forbade an immediate armoured advance, but in the meantime 19 Regiment was ordered

forward to a laager in a handy position on Sfasciata, and 24 Battalion was to be ready at half an hour’s notice for its part in the exploitation. General Freyberg pondered alternative uses for 19 Regiment – it might, under smoke and harassing fire, complete the occupation of the final objective on the right, or, leaving the first phase of his plan unfinished, he might switch to the second and send the regiment through in a bold sweep north of Orsogna to Filetto to shatter the German defences. But neither course would be followed unless the enemy showed signs of crumbling; he would not risk his armoured reserve in a tight battle, throwing it upon an undefeated gunline.

By early afternoon, it was clear that the battle remained tight and the enemy unbudging. ‘It is not a question of further advance,’ remarked the General. ‘It is a question of holding on to what we have got’. He had already issued instructions for the relief of the battered 21 Battalion by 25 Battalion that night and for 6 Brigade Headquarters to take over operational command from 5 Brigade Headquarters, with 28 Battalion under command. The two battalions on the first Fontegrande ridge were at close grips with the enemy, a training battalion of 6 Parachute Regiment, throughout the day, and though they had managed to make a solid line they were thankful for the help of 20 Regiment’s tanks and for all the supporting fire possible.

The troops across the Arielli stream were precariously placed. The bridgehead was held by 27 men of C Company, 21 Battalion, and 58 of B Company, 26 Battalion, and their attempts to expand it were speedily suppressed. During the morning the men of 26 Battalion joined those of 21 Battalion in a cleft near the north-eastern end of the spur to form a composite company under 26 Battalion’s command. Only 200 yards from enemy positions, they were at the mercy of German mortar fire. As casualties grew, Brigadier Kippenberger and both battalion commanders became convinced that the cost of holding the position outweighed any advantage it was likely to yield and orders were given to withdraw across the stream; but Freyberg, having listened to these opinions, reversed the orders and instructed the troops to hold firm until night, when 25 Battalion would relieve them. After a long approach march over muddy tracks, 25 Battalion (Major Norman)21 carried out the relief as planned, posting its D Company (Captain Hewitt)22 in the salient with orders to retire if attacked.

For the Maoris on the left flank, the 24th was a day of danger and discomfort. Since the stream only took its rise on their right

front, they were for the most part deprived of the natural protection it afforded the other two battalions; immediately before them, swarming with Germans, was a fairly level stretch of country which gave little cover from observation and exposed the battalion to counter-attack. Several times during the day threatening motions, which might have been the prelude to counter-attacks, were checked by urgent fire. From the steady drizzle of German hostility B Company suffered most heavily. For a while in the afternoon its command devolved upon Sergeant Crapp23 after Major Sorensen and all his platoon commanders had been wounded. By dark the company had been reduced to 38 men and it had to be relieved by C Company as part of a general consolidation of the line.

Christmas Day came in quietly along the whole front. It brought the replacement of 5 Brigade by 6 Brigade in operational command and, as the event was to show, a new phase, in which mid-winter struck the offensive from the hands of men.

(iii)

The name ULYSSES, with its overtones of far-travelled prowess, was a name that the results of the operation belied. For the Division never conquered its initial difficulties. The troops had lost their freshness and their first élan had been blunted. The weather was wretched during the attack, miserably cold, with low clouds and frequent rainstorms. The mischance which no planning can eliminate showed its hand in minor ways – one battalion lost the use of a wireless set when a mule fell into the Moro and another had to share its frequency with a commercial radio station. Twenty-first Battalion was distracted by concern for its right flank. In their assault the Maoris were troubled by the arrangement of the barrage: when it paused between two bounds on 26 Battalion’s front they were exposed to devastating fire from their open right flank. On their left, the dominant buildings of Orsogna housed strong, well-armed detachments of Germans.

The Division gained the whole of its first objective, the Fontegrande ridge east of the Arielli, which had formed the outpost line of the training battalion of paratroops and of II Battalion 146 Regiment; but it had only a foothold on the final objective, and the Germans’ main line of defence in the area was unbroken. The Germans had been expecting an attack, and in spite of a momentary incursion, which was thrown back from the crest of the salient, and some anxiety about roving New Zealand tanks, both battalions rallied quickly and held their prepared positions without exhausting their

reserves. Their success left the opposing infantry localities only about 300 yards apart – an uncomfortable proximity which earned notoriety as ‘Jittery Ridge’ for the first of the Fontegrande ridges, now firmly in the New Zealanders’ possession.

The Division’s casualties in the attack numbered 119 – 22 killed and 97 wounded – about half of them in 28 Battalion. The figures are high, considering that none of the infantry battalions had more than 250 men in its rifle companies when the attack began. The enemy lost 38 prisoners, but the two German divisions admitted only eleven men missing in the evening report of 76 Panzer Corps on 24 December. It seems likely that the casualties reported at the same time – 5 killed and 32 wounded – understate their losses. They put five New Zealand tanks out of action at a cost of three anti-tank guns destroyed.

If territorially the operation was a disappointment, tactically it was a portent. Since the Division first launched itself at Orsogna three weeks before, it had discarded as impracticable a southerly outflanking drive and a frontal assault; it had gradually come to develop a movement ‘north about’, with the infantry penetrating or disconcerting the defences for the armour to exploit. But now the infantry had been brought to a halt with no more than slight gains; and perhaps more significantly, the plan of armoured exploitation had early to be jettisoned. In three weeks winter had closed in; snow, already lying on the heights, could be expected on the battlefield; ways were foul and the sky was being emptied of aircraft. After Christmas the Division, led, trained and equipped for mobility, had to reconcile itself to a static war of emplacement.