Chapter 8: Cassino: The Preliminaries

I: A New Task

(i)

A CHANGE of plan now brought the Division under the eyes of the world and linked for ever the youthful name of New Zealand with the venerable name of Cassino. The task at Orsogna was left unfinished for a new and unexpected mission better suited to a corps de chasse. At the end of December the intention had been to leave the Division in the line for the next month and then to relieve it for a period of training. But at 4 a.m. on 17 January it relinquished command of its sector to 4 Indian Division, newly arrived in Italy. To understand why, it is necessary to ascend once more the Olympus of grand strategy.

It may be recalled that, as the Allied armies felt the stiffening of German resistance across the narrow waist of the Italian peninsula, Alexander superseded his optimistic plan of October by a more carefully deliberated plan of early November. Fifteenth Army Group now envisaged operations for the capture of Rome as developing in three phases. In the first, the Eighth Army on the Adriatic flank was to advance to Pescara and Chieti and then strike left-handed through Avezzano to threaten Rome from the north-east. In the second, the Fifth Army, west of the Apennines, was to drive up the Liri and Sacco valleys to Frosinone, approaching Rome from the south. In the third, a seaborne force landed south of Rome would seize the Alban Hills, whence they would descend on the capital, only a few miles to the north-west. The first part of the plan, as we have seen, miscarried, leaving the Eighth Army arrested between the Sangro and Pescara rivers; and by the time the Fifth Army had fought its way as far as the German winter line guarding the entrance to the Liri valley, the third stage of the plan, the amphibious operation shingle, seemed to have been outmoded by events. The plan to land about 23,000 men at the twin towns of Anzio and Nettuno had presupposed that the Fifth Army would be within supporting distance, but by mid-December it was clear that this condition would not be realised within any predictable

period. Operation shingle had therefore to be either abandoned or recast.

As the principal exponent of the circular strategy, Churchill could not endure the thought of stalemate in the Mediterranean. Convalescence from pneumonia on its southern shores gave him time for inquiry and meditation. He soon made up his mind that ‘the stagnation of the whole campaign on the Italian front is becoming scandalous’;1 no offensive use had been made of the landing craft in the theatre for the last three months. The Mediterranean venture which he had pioneered and protected must not be allowed to grind to a halt in mud-bound deadlock. He was now intent on stirring up fresh devilment for the enemy in Italy. The sudden amphibious strike behind the enemy lines, the ‘cat-claw’, promised alluring rewards – the capture of Rome, the destruction of a large part of the German forces in Italy, favourable reaction in the Balkans, relief for the Russians, further distraction for the Germans, the fullest employment for Allied resources in men and materials and the best possible prelude to OVERLORD.

Wheels began to hum. Churchill won over every high commander who would come to his bedside. He deputed General Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who had been one of his visitors, to influence the British Chiefs of Staff. On Christmas Day at Carthage he gathered about him Eisenhower2 and the Mediterranean commanders-in-chief of all three services and before they broke up shingle had been revived in a greatly expanded form. The force now to be landed at Anzio about 20 January, consisting at first of two assault divisions and eventually of more than 110,000 men, would be strong enough to hold its own in the event of delay in linking up with the main Fifth Army front.

The point of resistance was the shortage of landing craft. The new shingle could not be mounted unless fifty-six LSTs, due to return to the United Kingdom for OVERLORD from 15 January, could be detained until 5 February. Churchill ordered a review of the programme for the fitting out of these vessels for the cross-Channel invasion, with time margins pared to the limit. The result convinced

the British Chiefs of Staff that shingle about 20 January was not incompatible with OVERLORD in May, as promised to Stalin at Teheran. But OVERLORD still meant to the Americans what its code-name implied; and Churchill awaited with tremulous anxiety the outcome of his appeal to Roosevelt. On 28 December the President telegraphed his approval. Churchill received it ‘with joy, not... unmingled with surprise’. ‘I thank God,’ he answered at once, ‘for this fine decision, which engages us once again in wholehearted unity upon a great enterprise’.3

While Churchill steered the enterprise between a few last shoals-problems of build-up on the bridgehead and the need for an airborne force – Alexander4 decided to entrust the assault to one American and one British division under command of 6 United States Corps (Major-General J. P. Lucas).

In order to draw enemy reserves and attention away from Anzio and to burst through the German front on the way to the aid of the seaborne landing, General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army was ordered to make a strong thrust towards Cassino and Frosinone shortly before 22 January, D-day for shingle. Alexander wanted to be sure that the Fifth Army had sufficient strength to exploit up the Liri valley. It was for this reason that he decided to withdraw 2 New Zealand Division from the Eighth Army to the Naples area to form an Army Group reserve with which to influence the battle. The Division received warning notice on 9 January, and on the 12th its role was forecast in an Army Group instruction: ‘The task of this division will depend on the course of the operations, but it is primarily intended for exploitation, for which its long range and mobility are peculiarly suited. It will be placed under command of Fifth Army when a suitable opportunity for its employment can be foreseen.’

(ii)

The relief of the Division by 4 Indian Division went on for about a week from 13 January, the forward posts changing hands by night without worse mishap than the occasional jostling and straying inevitable when large numbers of troops take over strange positions in the dark. The New Zealanders still in action came under command of the Indian division when it assumed control of the sector early on the 17th, but by this time nearly half the Division was on the road back, and by the 20th only a few rear parties remained in the area.

No means were overlooked to confuse the enemy about the Division’s movements. The information given to the troops was incomplete and misleading but plausible enough to discourage rumour. In the warning order for the move, issued on the 11th, San Severo was named as the destination and four weeks’ training as the purpose. All New Zealand insignia were removed from clothing and vehicles, and the Division masqueraded for the time being under the name of SPADGER force. To hide the departure of 4 Armoured Brigade, the exact positions it had vacated in the reserve sub-sector of Castelfrentano were occupied by 101 Royal Tank Regiment, a camouflage unit, and the first stage of the New Zealand tanks’ withdrawal was shielded from prying enemy aircraft by a standing patrol of Spitfires at 20,000 feet. In order to deceive, if concealment should fail, measures were taken to represent the Division as concentrating at Petacciato on the Adriatic coast. Signboards were erected and a wireless traffic and other incidents of the New Zealanders’ presence were simulated while the Division, moving southwards, observed wireless silence. How far these shifts and stratagems would baffle an observant enemy behind the lines is doubtful; and it is also doubtful whether the enemy beyond the lines was deceived. On the 17th, after the capture of twelve men of 1 Royal Sussex Regiment on the notorious spur across the Arielli, the German Tenth Army reported to Army Group C that 4 Indian Division had definitely relieved the New Zealanders. Whatever it was that shook confidence in this intelligence, later thoughts were more cautious: as late as the 23rd 76 Panzer Corps spoke of a relief of the Division as ‘not impossible’.

By this time the Division had almost completed its march to the west. Unit advance parties set out together on the 13th. The 4500 vehicles of the main body followed in eleven groups, ranging in size from nearly 600 to just over 200 vehicles. Each group assembled behind the line and travelled by night the 25 or 30 miles to a staging area near Casalbordino. Thence, after a halt of two or three hours, it resumed its journey by day to San Severo, about 80 miles farther south. The first group, belonging to the Army Service Corps, left Casalbordino shortly before dawn on the 14th, and the last, the armoured workshops group, precisely a week later. San Severo was only a night’s halt, and there the men were let into the secret of their mission. The next day’s journey took each convoy across the Apennine divide and down into the populous Campanian plain to the area of Cancello, about 20 miles east of Naples. From Cancello it was only a short march on the third day to the divisional training area. The hard knocks of the Orsogna campaign had probed the weaknesses in many vehicles, and the recovery trucks that brought up the

rear of each convoy were kept busy in giving first aid to stragglers. The tanks of the Division, strengthened by fifty-two taken over from 5 Corps’ reserve, were meanwhile transported by train from Vasto to Caserta and thence driven to their destination.

The divisional area lay in the prettily wooded valley of the Volturno on the downward slope from the Matese Mountains to the northern banks of the river. Known as Alife from the grubby walled village that was one of the centres of its peasant life, it was, even in winter, a smiling stretch of country where it was easy to relax, to make good arrears of sleep, and to see to the upkeep of vehicles and weapons. Training programmes were not too rigorous - for infantrymen route marches and rifle-shooting, for the armoured brigade tank maintenance, for gunners gun drill and route marches, for engineers practice in river crossings with Bailey and pontoon bridges, rafts and assault boats. Late in the month 4 and 5 Brigades borrowed the assault boats for brigade exercises on the Volturno. To freshen up personal appearances and corporate morale, most of the formations held ceremonial parades, which the General inspected. Sports were played, daily excursions of no excessive solemnity were made to Pompeii, there were concerts and social occasions. Rested and reinforced by the arrival of 600 men, mostly infantry, the Division felt fitter for the trials ahead.

(iii)

All this time the Fifth Army’s winter offensive was developing, but with such setbacks as to make it less likely that the Division would be employed as a pursuit force. On its main front, the Fifth Army was up against the Gustav line,5 the southern section of the German winter line, which traversed the narrowest part of the peninsula from Ortona to Minturno. Here the mountains bar the way from coast to coast, parting only south of Cassino at the mouth of the Liri valley to open a gap six or seven miles wide, through which the Via Casilina (Route 6) passes on its way to Rome, 85 miles distant. Across the mouth of the axial valley of the Liri runs a lateral valley, carrying a stream of waters successively augmented and successively renamed. Fed by the mountains north of Cassino, the Rapido flows past the town, then out across the Liri valley as the Gari, and finally joins the Liri itself to become the

Garigliano, which winds through an alluvial plain to the Gulf of Gaeta. At its junction with that of the Garigliano, the Liri valley is not easily forced, for it is flanked on the north by the hills rising steeply from Cassino to the topmost peaks of the Central Apennines and to the south by the rough Aurunci Mountains, and it is stopped by the waters of the Rapido or Gari. It was a classic battleground over which the Fifth Army now prepared to fight. In 1503 it had witnessed the crushing defeat of the French invaders by the troops of Spain and Naples and the drowning of a Medici heir as he tried to float his cannon down the river; and it was here in 1860 that the Piedmontese scattered the Neapolitans of the Bourbon regime in one of the culminating battles of the Risorgimento.

General Clark’s plan of a turning movement on either side of the Liri valley and a drive down the valley itself opened on 17 January, when 10 British Corps launched itself across the Garigliano and into the Aurunci foothills. On the 20th, when four enemy divisions were fiercely engaged on the left, 2 United States Corps began its assault across the Rapido, and a few hours later the French Expeditionary Corps brought the right into play by attacking through the mountains to outflank the Rapido defences from the north. Every division of the German Tenth Army had been drawn into the task of staving off this threefold offensive when 6 United States Corps landed at Anzio at dawn on the 22nd. Kesselring’s response was calm and prompt. Instead of pulling his forces out of the Gustav line for fear their communications should be cut, he ordered them to stand and proceeded to seal off the Anzio bridgehead with a force hastily assembled from eight different divisions. All four thrusts of the Fifth Army made some progress and were then halted.

To this threat of deadlock Clark reacted by ordering the attack on the Gustav line to continue. Second Corps’ frontal bid across the Rapido having been bloodily repulsed, he decided to envelop the defences from the right. This necessitated fighting in the hills above Cassino in order to capture the ‘Cassino headland’, the massive spur running down from Monte Cairo and having as its southern tip the commanding eminence of Montecassino, sentinel over the mouth of the Liri valley. For six days at the end of January, therefore, the Americans and French against stubborn opposition worked their way slowly through the rugged hills around the village of Cairo, whence they might turn left to battle through broken country, over Montecassino, and at last down into the Liri valley. But this was not to be, and already by the end of the month the strength of the German resistance here and at Anzio made it plain to Alexander that the New Zealand Division would need to be

reinforced if it was to have a chance of success in its task of exploitation. The task, moreover, required a larger organisation than one division could supply. Hence on 30 January he instructed Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese, the new commander of the Eighth Army, to despatch 4 Indian Division without delay to form part of a temporary New Zealand Corps under General Freyberg.

At 10 a.m. on 3 February, while the Indian division was still on its way from the Adriatic coast, the New Zealand Corps officially came into being and passed under command of Fifth Army. The organisation of the corps called for some slight improvisation. The heads of services in 2 New Zealand Division assumed a double role, taking up similar duties in the New Zealand Corps. The only additional appointment made immediately was that of Colonel Queree6 as BGS, New Zealand Corps, while Lieutenant-Colonel L. W. Thornton resumed the appointment of GSO I of 2 New Zealand Division. To form a common corps pool under centralised control, no apportionment of transport and other facilities was made between corps and division. For a week or so from 3 February the Corps’ administrative resources were built up by the attachment of a general transport company, two mobile petrol filling centres and a bulk petrol company, five mule transport companies, a corps ordnance field park company, a provost unit and a pioneer labour company. The artillery was strengthened by 2 Army Group, Royal Artillery, comprising three field regiments (one with self-propelled guns), five medium regiments and a light anti-aircraft battery, and by three American anti-aircraft battalions. In addition to this formidable increase in fire-power, the corps had the heavy and medium artillery of 2 United States Corps available for its support throughout the Cassino operations. The engineers, the medical corps and the armoured services were also reinforced from British and American sources.

Later in the month, when plans were being matured for a breakthrough by the corps, the American Combat Command ‘B’ (part of 1 United States Armoured Division) was added as an exploiting force. It was divided into Task Forces A and B, each composed of two tank battalions, a tank-destroyer battalion,7 and two companies of engineers, and it had four battalions of field artillery in support.

Meanwhile the role of the corps had been the subject of discussion at high levels. In an outline plan drawn up at Alexander’s

request and after reconnaissance, Freyberg put his faith in surprise and weight of metal from aircraft and gun. The clearing of the Cassino headland seemed to him the first condition of success in the valley below. That done, the corps on a two-divisional front should cross the Rapido and punch a passage down Route 6 in the wake of overpowering air and artillery bombardment. The Indian division, experienced in mountain warfare, would operate in the hills north of Route 6 and the New Zealand Division in the Liri valley.

Hopes were still high that the preliminary conquest of the hills above Cassino would be carried out by the troops already fighting there, and 2 US Corps, much weakened and nearing exhaustion after two months of unbroken combat, was now asked for another effort. While one force attacked the town of Cassino from the north, a second would continue to press forward from hill to hill to take Montecassino from the rear. To buttress 34 US Division in its push through the hills 36 US Division, holding the line of the Rapido in the throat of the Liri valley, would have to be relieved south of Route 6, and on 3 February Clark ordered the New Zealand Corps to detail a brigade for this purpose.

It was in these circumstances that 5 Brigade, as the vanguard of the New Zealanders, went into the line before Cassino. The plan was now for the Americans to move forward along the hilltops so that the New Zealanders might establish a bridgehead across the Rapido and pass tanks across. The Indian division was not to be committed immediately but was to await the outcome of the American attack.

The plan for this attack, like the plans that succeeded it, aroused little enthusiasm among senior commanders, least of all among those directly charged with its execution. It was accepted as a necessary duty. Each new strategic move in Italy had involved the Allies in deeper play. Before the New Year there had been no military necessity for aggression against the Gustav line; but, with the force at Anzio first contained and then threatened, the necessity became urgent. So long as the bridgehead was in danger, the pressure for action on the Cassino front, regardless of weather or terrain, was irresistible. It was a portent that on the day when the New Zealand Corps came into existence the Germans launched their first counter-attack towards Anzio. On 8 February Churchill found some consolation for his disappointment in the fact that the enemy was being engaged in such strength so far away from the other battlefields. ‘... we have a great need to keep continually engaging them, and even a battle of attrition is better than standing by and watching the Russians fight’.8 A battle of attrition it was to be.

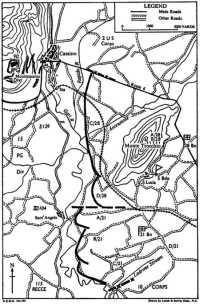

5 Brigade Positions, 8 February 1944

On The Rapido

(i)

The deployment of the corps was a work requiring caution, patience, tact and good humour. The superb command of the enemy over the valley of the Rapido and Garigliano and long stretches of Route 6 confined the movement of convoys in the forward area to the hours of darkness, when drivers had no more luminous guide than the wan beam of undercarriage lighting on the truck ahead. Route 6 was a busy highway running through a rain-sodden and dejected landscape and past the litter of battle and grey stone buildings wasted by war and splashed with mud. It was under the tight control of American military police, models of brisk, or even brusque, efficiency, and the strange driver felt at first like a bucolic drayman plunged into the traffic stream of a metropolis. Owing to congestion on and off the roads, the corps could take forward only essential transport, and this had to be divided into small convoys of not more than thirty-six vehicles each.

Reconnaissance parties were at their wits’ end to find suitable assembly areas, gun positions and the like. Except well forward on the floor of the Rapido valley, the demand for flat ground exceeded the supply, most of it having long since been engrossed by earlier arrivals. As it was necessary to disperse vehicles without delay and impossible to evict existing occupants, late-comers had to fit themselves in as best they could, colonising ill-favoured sites and setting to work to make them tenable by sweeping for mines, forming tracks, and digging drains. Overhead the sky was grey, raining or threatening rain, and in many places pools of water lay on the ground. The diverse nationalities that elbowed and jostled each other along and about Route 6 met on a common footing of mud.

While spare vehicles and the men ‘left out of battle’ (comprising 7½ per cent of the fighting units) remained round Alife, the rest of the Division steadily moved into the battle area between 4 and 7 February, leaving 4 Indian Division to follow later when the result of the contest among the hills above Cassino became clearer. The elements most urgently needed were the infantry of 5 Brigade, who were to relieve 36 Division, and the artillery, whose fire was to hammer the defences resisting 2 US Corps.

First into the line was 21 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel H. M. McElroy). It moved up in the heavy rain of the afternoon and evening of the 4th and by an early hour next morning had taken over a 3000-yard front on the Rapido south-west of Monte Trocchio from 143 US Regiment, the left-flanking formation of 36 US Division. Because of some hitch in the transmission of orders, 28 Battalion

(Lieutenant-Colonel R. R. T. Young) was unable to relieve 141 US Regiment on the right next day as it had hoped. When it arrived, the Americans had received no instructions to hand over and refused to do so, but instructions came to hand about midday on the 6th and by nine o’clock that evening the relief was complete. Although two American battalions had occupied this sector, they had lost heavily in the attempt to cross the Rapido, and one company of Maoris – D Company (Captain J. Matehaere) – was judged sufficient to hold it. Meanwhile, C Company (Captain Wirepa) had replaced 91 Reconnaissance Unit between 141 Regiment and the divisional boundary on Route 6. The brigade’s third battalion, the 23rd (Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. J. Connolly),9 went into reserve behind Monte Porchio, a hill similar in shape to Trocchio but smaller and farther to the rear. With its headquarters established in the lee of Trocchio, 5 Brigade was now in position between the Americans of 2 Corps and the British of 10 Corps.

Restricted in their choice of gun positions by the number of troops already on the ground, the three field regiments spent the whole of the 5th in deploying in muddy and slightly rolling country behind the infantry. The density of American anti-aircraft defences made it unnecessary to bring forward more than one Bofors battery, the 41st, which was sited near Porchio to protect the heavy and medium artillery. The flash-spotters of 36 Survey Battery found an admirable base on the summit of Trocchio.

In accordance with the carefully prepared timings of the Corps’ movement order, the remaining New Zealand convoys left the Alife area between the 5th and the 7th, dispersing themselves around Route 6 for several miles behind the Porchio feature. Immediate administrative needs were served by the opening of two advanced dressing stations and a casualty clearing station, and of ammunition, petrol, and supply issuing points.

Among the busiest of the supply troops were those of 1 Ammunition Company. It was a long journey back over crowded roads to Teano, Capua or even Nola to collect their loads, and the tank transporters had to be called on to lend a hand in the dumping programme. The object was to establish forward dumps of 770 rounds for each 25-pounder gun, 490 for each medium gun, and 300 for each 105-millimetre gun in the corps, and to have on wheels 300 more rounds for each 25-pounder gun and 200 for all others. Since the corps artillery numbered 192 25-pounders, 80 medium guns, and 24 self-propelled 105-millimetre guns, it can be calculated that more than 272,000 shells had to be handled, the lighter in boxes of four, the heavier singly, together with the charges and the

fuses that go to make up the complex unit known as a round. The petrol which the mobility of the corps promised to consume in vast quantities came up by varied means – as far as Sparanise by pipeline, then to a centre near Alife in tank lorries, and finally to the New Zealand petrol point in cans.

With one brigade in the line, with the rest of the New Zealand fighting troops handily disposed and with 4 Indian Division assembling in the rear, the New Zealand Corps, reinforced, fuelled and munitioned, was gathering itself for the break-through and pursuit. At 9 a.m. on 6 February it took over from 2 Corps command of the Rapido line south of Cassino. The northern boundary with 2 Corps was Route 6 and the southern with 10 Corps ran along a lane south-west from Colle Cedro to the Gari. The corps area thus broadened out fanwise towards the enemy to form a front of seven or eight thousand yards along the Rapido where it flows south across the mouth of the Liri valley.

Here at the meeting of the two valleys, 5 Brigade’s immediate surroundings were desolate, but no one could deny a wild grandeur to the wider prospect or miss the sense of portent in its bold architecture, as though it had witnessed great deeds not for the last time. Behind or to the right of the platoons near the river, the long, sharply-ridged, clean-sculptured shape of Monte Trocchio rose abruptly out of the plain and showed an almost sheer western face 1000 feet high towards Cassino. From the foot of Trocchio the ground dropped in gentle undulations and then, as it neared the river, became flat and marshy and covered with reeds and brush. The land had been cultivated but already, after three weeks of battle, the willows looked scarred and the vines and small trees spindly and stunted. The lanes and tracks were thick with mud and the numerous farmhouses were becoming dilapidated in appearance and often in fact. As Route 6 skirted the northern shoulder of Trocchio, so the railway line ran round the southern shoulder and then north across the New Zealanders’ front to a bridge over the Rapido half a mile south of the main road. Beyond the Rapido the rolling country came down almost to the brink of the river, giving the Germans better covered approaches and allowing them to hold posts actually on the riverbank, whereas the New Zealand outposts were set back between 200 and 400 yards. Midway between Montecassino and the village of Sant’ Ambrogio – the two posts, as it were, upon which the double gates of the Liri valley swung – lay the village of Sant’ Angelo, built on a bluff high above the river and commanding the whole width of the gateway.

Looking over greater distances, the New Zealand infantry saw far to their right the snow sprinkled on the summit of Monte Cairo

and, disquietingly close, the white range of abbey buildings set four-square on the southern promontory of the Cairo massif. At the foot of the abbey hill, facing the New Zealanders, were the grey stone buildings of Cassino town; directly in front of them lay the valley that led to Rome; and south of it again, far to the left front, the Aurunci Mountains stretched away, peak on peak, toward the Tyrrhenian Sea.

(ii)

The German troops on the western side of the Apennine divide belonged to 14 Panzer Corps, commanded by General F. von Senger und Etterlin, a man of wide attainments who had been a Rhodes Scholar before the First World War and who was known for a cool and clear-headed soldier. The inland mountain sector was held by 5 Mountain Division and 44 Infantry Division, the latter on Monte Cairo. Between Monte Cairo and the Liri valley 90 Panzer Grenadier Division had just been hurriedly brought into the line to stiffen the defence of a vital sector which embraced Montecassino, the hills north of it and the town itself. It was commanded with dash, imagination, and close knowledge of the ground by the independent-minded Lieutenant-General Ernst Baade.10 South of Route 6, in the Liri valley itself and opposite the New Zealanders, was 15 Panzer Grenadier Division (Lieutenant-General Eberhard Rodt), a formation of fairly high quality, well equipped with infantry weapons and presumably heartened by its success in throwing back, with heavy losses, the attempt of 2 US Corps to cross the river on 20–22 January. The rugged southern sector from the Liri to the sea was committed to a single division, 94 Infantry Division, which, having responsibility also for coastal defence up to Terracina, was stretched to danger point.

The terrain occupied by the enemy was renowned for its natural military strength. In the north the high country inland from Monte Cairo and in the south the Aurunci Mountains – both almost roadless wastes built on a majestic scale – could be held lightly and without elaborate field defences. Defensive effort was concentrated in the centre, where Montecassino dominated the entrance to the Liri valley – ‘a classical example of the control exercised by height over terrain.’11 After years of studying it as a regular tactical exercise, the Italian General Staff believed this position to be all but impregnable even without artificial works. Now the Germans had incorporated it into the Gustav line and for months had been building fortifications.

Nothing that skill could devise or energy execute had been omitted to make it proof against assault. In the summer of 1943 Cassino was the headquarters of 14 Panzer Corps.12 The corps returned there after the withdrawal from Sicily and in September it began to prepare defences in accordance with Kesselring’s intention to stand south of Rome, which Hitler soon confirmed. As the Allied armies drew near work was pressed on by the Todt organisation, assisted by the labour of civilians and prisoners of war.13 From north of Cassino to its confluence with the Liri the line followed the west bank of the Rapido, but the very core of the defences in the Cassino area lay behind the river in the complex of mountains north and west of the town. Here, in rough, bare country furrowed by deep ravines, the Germans held a series of peaks from which defensive posts could give mutual support and sweep all approaches with fire.

From the key height of Montecassino on the tip of the spur observers had an almost uninterrupted panorama over the valleys of the Liri, the Rapido and the Garigliano about 1500 feet below. The Rapido line itself was protected by flooding, notably south-east of Cassino, by the demolition of roads, tracks and bridges forward of the line, and by wire and minefields on both sides of the river. North of the town emplacements were dug into steep slopes across the river and were served by concealed communication trenches. Behind anti-tank obstacles, the narrow streets and stone buildings of Cassino had been easily converted into a fortress. Attackers would be challenged by machine-gun posts strengthened by concrete, steel, and railway ties, by well-armed snipers at doors and windows, and by self-propelled guns and tanks sited to see without being seen.

Southwards across the mouth of the valley strongpoints powerfully supported by field artillery were established at irregular intervals, with the village of Sant’ Angelo as the pivot of the system. All along the line houses had been destroyed and trees felled to clear a field of fire and rob an attack of cover.

(iii)

When the New Zealand Corps assumed command of the Rapido line south of Cassino on 6 February, its future role was shrouded in a mist of contingency. It was still hoped that the Americans would prise open the German defences and allow the New Zealanders to crash through the Rapido line and drive down Route 6. Though these hopes dwindled as each day passed, it would still be

necessary, in any eventuality, for the corps to establish a bridgehead across the Rapido, and Freyberg ordered 5 Brigade to reconnoitre the river thoroughly to find out its depth, width and speed, the height and nature of its banks, covered approaches, suitable crossing places and routes to them, and all other information of value in planning an assault.

Within a few hours of its entry into the line 5 Brigade had begun to amass information, but only, unhappily, by the method of exchange. On the night of 6–7 February each of the two battalions despatched two reconnaissance patrols with instructions to return before dawn, not to cross the river and not to lose prisoners, which would disclose the presence of the Division. In the northern part of the front the two Maori patrols, led respectively by Second-Lieutenants Tomoana14 and Asher,15 spent six hours in unhindered inspection of the river and the approaches to it. They found that, though assault boats could be launched at any of the crossings examined, the tracks leading to the river were soft, muddy or even waterlogged and exposed. Fifth Brigade accordingly advised Divisional Headquarters that bridges could be built across the river provided the engineers cleared the approaches and made them firm.

Farther to the left 21 Battalion spent a less satisfactory night. Both of its patrols clashed with an enemy who in this sector was alert and aggressive. The first, having explored the river near a demolished bridge at the southern entrance to Sant’ Angelo, ran into a German ambush on the way back and left two of its men in German hands. The second, under Second-Lieutenant Fitzgibbon,16 returning from a more southerly stretch of the river, was engaged by about a dozen Germans in a creek bed. The arrival of a party of ten men led by Lieutenant Burton17 from B Company reversed the odds and the enemy withdrew, though Fitzgibbon was wounded and it was nearly an hour before all members of his patrol were reunited at B Company’s forward posts. The Germans were still on the move in the area. B Company, suspecting that they might try to recover wounded comrades believed to be lying in front of its outposts, eventually sent forward a party which brought back two prisoners.

Meanwhile enemy raiders had found a way between the rather scattered section posts and surrounded the house occupied by C Company headquarters. Doors and windows were slammed fast; Major Abbott recalled his forward platoons to deal with the patrol

and telephoned battalion headquarters to fire west of the river. The Germans outside, who overheard the conversation, cheekily summoned him by name to surrender. The invitation was rejected and the Germans faded away towards the river in an exchange of small-arms fire. When calm was restored, one man was found to be missing from outside company headquarters and, after a fruitless search, had to be presumed a prisoner.

The loss of three prisoners overnight made mortifying news for the New Zealand command next morning: the fact that the New Zealanders had joined the Fifth Army, hitherto so carefully concealed, was a revelation of strategic proportions. With a shrug for the irrevocable past and a care for the future, Brigadier Kippenberger ordered Lieutenant-Colonel McElroy to reorganise his battalion into compact company areas and to send out only strong patrols capable of looking after themselves. Now that the secret was out, it was thought safe to allow the Division on the 10th to resume its signs, titles and badges and to drop the pseudonym of spadger force.

Strong patrols of Germans continued to venture across the Rapido on the following nights and to explore the brigade’s territory until, on the 9th, 28 Battalion advanced its outpost line to the bank of the river to control the intruders. Twenty-one section posts were set up at 100-yard intervals and, with help from the reserve companies, were manned nightly until 5.45 a.m. and left empty by day. From time to time the gunners scored successes in answering infantry calls for fire, but one such success was quite inadvertent. On the night of 10–11 February a green flare lit up the Maoris’ front. Whatever it meant in the signal code of the Germans who fired it, to the New Zealanders it meant that the enemy was approaching in overwhelming force. The shellfire that the Germans thus brought down on themselves was severe and found a mark, for the Maoris heard their wounded crying for help.

Twenty-first Battalion, which had suffered no further surprises after adjusting its dispositions, was relieved on this same wet night by the Divisional Cavalry Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel I. L. Bonifant) in its now customary role of line-holding infantry. At the same time the brigade’s fire-power was strengthened by the deployment of 2 Machine Gun Company (Captain Aislabie),18 which opened its programme of harassing Route 6 before it could dig in and paid for its temerity by drawing heavy return fire from the German machine-gunners.

On first going into action, the New Zealand gunners were ordered to refrain from predicted fire as far as possible for fear that their distinctive methods would reveal their presence, but infantry calls

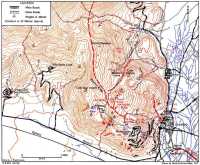

Operation AVENGER, 15–18 February 1944

for defensive fire could not be neglected, and soon, in any case, the precaution was unnecessary. Targets were designated nightly in the Liri valley and by day some of the observed fire was controlled by air OPs, operating from a landing strip just east of Porchio. Counter-battery fire against the numerous enemy nebelwerfers – 15 Panzer Grenadier Division alone had seventy-two – was a chief preoccupation for the artillery. These weapons, which sorely troubled the infantry with the shattering and destructive blast of their bombs, were easy to locate because of their brilliant flash and a shower of sparks but they were hard to destroy. Some may have been dug into banks and run out on rails to fire. Some were certainly manned by crews who, having fired, removed them and bolted for their dugouts before the retaliatory fire came down. To counter these tactics, some New Zealand guns were permanently laid on nebelwerfer positions ready to fire at a word; but the Germans kept one move ahead by shifting the nebelwerfers to a new position each time they fired.

(iv)

To the infantry along the sodden line of the Rapido and to the troops supporting them in more genial surroundings, 11 February was like any other day, but it was in fact decisive. The Division’s future was being decided among the heights above Cassino. It will be remembered that by the beginning of February 2 United States Corps, instructed to maintain the momentum of the winter offensive, had made appreciable gains in a right-about movement of descent upon Montecassino and Cassino town from the north. Though 36 Division on the left was halted in the northern outskirts of the town, 34 Division, after capturing the village of Cairo, wheeled left and attacked uphill to seize the commanding peak of Monte Castellone. Thence the way lay downhill for two miles across very broken country to Montecassino and its monastery, the last great obstacle before dropping down into the Liri valley.

By the 6th sheer dogged fighting had brought the Americans within measurable reach of their goal. They held a line stretching from a point on the eastern slope of the massif just north of Cassino through Point 445 (only 300 yards north of the monastery walls) and north-west to the embattled Point 593, where no one had more than a slippery fingerhold. But farther than this they could not go. Tired from ten weeks of fighting, gravely depleted (some units fell in the end to 25 per cent of their fighting strength) and exposed to dirty weather, they failed in a renewed attack on the 8th, and what was to have been the prelude to a race by the New Zealand armour down the valley towards Rome came to nothing. One final effort was ordered for the 11th.

Reluctant though he was to commit his exploiting force, General Alexander now warned the New Zealand Corps to take over the Americans’ sector in the event of their failure. General Freyberg’s plan of the 9th, drawn up with this contingency in view, was the fruit of long study of the ground and of air photographs, of thorough conference and the careful weighing of alternatives. The plan provided for an attack on the night of 12–13 February. Fourth Indian Division would inherit 34 US Division’s forward positions and its objectives. From the Castellone feature it would seize Monastery Hill (Montecassino), cut Route 6, and capture Cassino from the west. The New Zealand Division would assist the operation with fire and be prepared to cross the Rapido to help the Indians take Cassino. Exploitation towards Pignataro and the construction of crossings over the Rapido on Route 6 would be in the hands of United States Task Force B. Meanwhile, 5 Brigade was ready with plans to follow up an American success above Cassino by forcing the river. But these last plans were to be unnecessary.

Not unexpectedly, the attack on the 11th was repelled, and the larger corps plan rose to the top of the agenda. That evening Major-General A. M. Gruenther, General Clark’s Chief of Staff, spoke to General Freyberg on the telephone. ‘The torch is now thrown to you,’ he said. ‘We have had many torches thrown to us,’ Freyberg commented later, in the full realisation that the latest would not be the lightest.

The progress of the Americans among the hills had in fact caused General Senger great alarm. Each of his divisions committed in the major battle zone was losing the equivalent of one to two battalions daily and their annihilation was only a matter of time. He believed, moreover, that the penetration by the Americans north of Cassino had brought them within sight of Route 6, his indispensable supply line. In these circumstances he proposed, at the risk of his prestige, to withdraw from the Cassino front to the ‘C’ line, a new defensive position behind the Anzio bridgehead. The proposal was rejected.19 These facts might have comforted General Freyberg, had he but known them. As it was, he made a cool estimate of the prospects. Asked at Fifth Army Headquarters what he thought the chances of success would be, he answered ‘Fifty-fifty’, and declined an invitation to improve the odds.20

On the same day as the Americans made their last effort, an instruction from Alexander’s headquarters envisaged the possibility of a pause between the break-in and the break-through. While

anxious for an early advance up the Liri valley, Alexander directed that it should not be attempted until the ground was dry enough to permit the use of armour off the roads and the weather was suitable for effective air support. Nevertheless, there should be no delay in mounting 4 Indian Division’s attack to clear the high ground north and west of Cassino or in establishing a bridgehead over the Rapido near the town. When the New Zealand Corps was committed to an attack, all available resources, including the maximum effort in the air, were to be concentrated in its support. The note of urgency in Alexander’s directive is to be related to the heavy German counter-attacks then developing at the Anzio bridgehead. They must never be forgotten in any assessment of the coming action.

(v)

The New Zealand Corps, then, could no longer hope to pass through a door thrown open for it; it would have to open the door for itself. Preparations to this end were now accelerated. While, as we shall see, the Indian division laboured to install itself in the hills west of Cassino, the New Zealand Division made ready to seize and then to expand a footing across the Rapido. Temporary command of the Division now passed to Brigadier Kippenberger, who relinquished 5 Brigade to Colonel Hartnell.21

Kippenberger gave orders immediately, but it was already found necessary to postpone the attack for twenty-four hours until the night of 13–14 February. Twenty-eighth Battalion was then to cross the Rapido with two companies and capture Cassino railway station to enable the engineers to bridge the river and allow a squadron of 19 Armoured Regiment to cross. These tanks, with the rest of 28 Battalion, would attack Cassino from the south, linking up with the Indians, and 23 Battalion would then pass through to widen 28 Battalion’s bridgehead. The narrowness of the front on which the attack was to be launched was recognised as a weakness in the plan, but it was not to be avoided because of the widespread flooding of the Rapido around Route 6 and the railway line. Indeed, on the 12th, observation from Trocchio and closer reconnaissance left the officers of the two assaulting companies of 28 Battalion pessimistic. Though infantry could cross the river along the railway line, the area was so wet and marshy, with the fields under an inch of water in places, that deployment would be hazardous and, as digging was nowhere possible, supporting troops could not be employed with safety.

The same morning an engineer report to Corps Headquarters stated that even the infantry could not at present go across country south of the railway because of the ponding up of water, which would probably not subside for four or five days. The operation was therefore further postponed, but 28 Battalion was to be ready to attack any night. The two other battalions, the 23rd, which was to extend the bridgehead, and the 21st, which was to exploit under command of Task Force B, were put on six hours’ notice to move.

The Maori Battalion used the respite to build up its ammunition supply, work on its forward battle headquarters, and improve its knowledge of the ground. Of two patrols after dark on the 14th, one under Second-Lieutenant G. Takurua not only probed the enemy’s defences at the railway station, as instructed, but prodded them into vigorous life. Challenged by a sentry near the station, the patrol shot two Germans, whereupon at least six Spandaus opened fire from all quarters and for three minutes a fight was carried on with machine pistols and grenades. The Maoris escaped unharmed under cover of the railway embankment, leaving the defenders for the next hour or so to shoot their Spandaus at shadows. A companion patrol to the hummock, a group of black mounds about 200 yards south of the station, found the ground drier than on the last reconnaissance but remarked on its openness and want of cover. When a party from 21 Battalion saw it the next night, the Rapido was flowing fast, three or four feet deep, between stopbanks eight to ten feet high.

Successive postponements of the attack – on the 13th it was put off again till the 16th – were beginning to tell on the morale of the Maori Battalion, and the two forward companies, destined for a reserve role in the attack, were tiring. On the 16th, therefore, relief was arranged. Coming under 5 Brigade’s command, 24 Battalion (Major Pike)22 deployed A and B Companies (Captain Schofield23 and Major Turnbull),24 allowing the two forward Maori companies to retire to the Trocchio area. C Company of 24 Battalion (Major Reynolds)25 went south to assist the Divisional Cavalry, which, though not hard pressed, had had some brushes with German patrols and was a little anxious about a ragged left flank.

One of the guiding considerations in the choice of the railway station area as an objective of the coming attack was that the railway embankment could be converted into a road for bringing up wheels

and tracks over ground that would otherwise be impassable. But the Germans had not, of course, left the embankment intact, and the large number of bridges and culverts in this lavishly watered countryside had given their sappers scope for imaginative destruction. Equally, the New Zealand sappers had a prospect of highly concentrated repair work within small-arms range of the enemy on the flat and in full observation of the enemy on Monastery Hill, which hung like a hateful tapestry on the wall of the western sky.

Serious engineer reconnaissance began after dark on the 10th. Escorted by a patrol of thirteen men, including minesweepers, from 28 Battalion, Lieutenant Faram26 (5 Field Park Company) examined the railway track as far as the yards, where there was a brief skirmish with grenade-throwing Germans, and returned with a well-documented but doleful tale. In the thousand yards of track short of the station he counted ten demolitions, which he numbered in ascending order towards the enemy. The pithy nature of his report may be judged from a quotation: ‘Demolition 7 (86501933) – bridge over Rapido blown – 78 feet gap 8 feet deep – Messerschmitt 109 in gap – can be forded – hard gravel bottom – doze down each side’. Nearly all the demolitions would need bulldozing and some would need new bridges or culverts, but no mines were found and, except at one point, all rails and sleepers had been removed from the thirty-foot-wide permanent way.

This valuable report supplied the factual basis for the programme outlined by the CRE (Brigadier Hanson) at a conference on the 11th, when it had become probable that the Division would have to make an opposed crossing of the Rapido. The schedule of work then laid down, however, proved difficult to fulfil owing to a variety of hindrances that interrupted the career of the three field companies. One night traffic congestion delayed the engineers’ arrival on the job; another night heavy rain caused a field company to cancel work; undetected mines at Demolition 3 severely damaged two bulldozers; the affray which Takurua’s patrol touched off drove the engineers to cover; the western side of Demolition 5 was too steep for the bulldozers to climb; and enemy gunfire was a continual nuisance. In view of such setbacks and disturbances the engineers made satisfactory progress. Thanks partly to the regular protection of Maori patrols and to the covering noise of New Zealand gunfire, the first four demolitions were repaired by the 16th and a negotiable road existed almost as far forward as the outpost line.

That day, after expectancy had begun to flag, the attack was at last firmly fixed for the night of 17–18 February. In order fully to

understand the delay – and because the story itself encloses a famous episode of war – it is necessary to turn to the doings of the Indian division.

(vi)

Fourth Indian Division, withdrawn from the Eighth Army at the end of January into Fifth Army reserve and then placed under command of the New Zealand Corps, completed its move to the Cassino area by 6 February. Owing to the illness of Major-General F. I. S. Tuker, officiating command of the division – the phrase is Tuker’s – devolved on Brigadier H. W. Dimoline, the divisional CRA. At General Freyberg’s headquarters on the 4th he took part in the first of several conferences on the employment of his division. For some days, while the fortunes of 2 US Corps lay in the balance, no firm decision could be taken, though it was agreed that in any advance up the Liri valley the Indians’ experience of mountain warfare on the North-West Frontier, in East Africa, Syria and Tunisia fitted them to fight among the hills north of Route 6 while the New Zealanders fought on the flat. On the 9th, however, it was decided to commit the New Zealand Corps should the Americans fail to take their objectives by dark on the 12th, and Freyberg warned the Indian division to be prepared to attack immediately after that time. Most of the division was then in its rear assembly area, but 7 Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier O. de T. Lovett), which was to lead the attack on Montecassino, moved up on the 10th and concentrated on the lower slopes of Monte Castellone near Cairo village on the night of 11–12 February, ready to relieve the Americans the next night and to launch its attack the night after.

Final details for the relief of the Americans were arranged between 2 US Corps and the New Zealand Corps on the 12th. It was agreed that 36 US Division should continue to hold the large Castellone feature against counter-attacks from the west while the Indians attacked southwards from Points 593, 450 and 445, the limit of the American advance towards Monastery Hill. Thirty-sixth Division could muster only 600 or 700 men on Castellone and might have to call on the New Zealand Corps for help. Major-General Geoffrey Keyes, the American Corps Commander, wondered how long it could hold on if the Indians did not attack soon. Its boundary with the Indians was a stream running north-east between Castellone and Maiola hills and then bearing east round the northern side of Maiola to join the Rapido near the Cassino barracks. The Indians had as neighbours on their left the Americans of 34 Division, which remained in Cassino town with its right flank on the lower slopes of the Cassino massif along a line from Point 193 (Castle Hill) to Point 175.

A relief that would in the best conditions have been arduous was made doubly so by mischance. The Indians, expecting to take over a sector solidly held, found it a battlefield. For the Germans refused to give up for lost the ground that the Americans had won at such heavy cost. On 5 February 14 Panzer Corps commented that ‘over a long period the present situation would be intolerable, i.e., the enemy occupying positions west of Cassino only two or three kilometres north of the Via Casilina’. Early on the morning of the 12th, just as the leading Indian brigade was assembling near Cairo, 90 Panzer Grenadier Division launched two assault groups of 200 Panzer Grenadier Regiment against Castellone under an unusually heavy barrage. The height fell to the Germans and for a while the American defences were critically disorganised, but all possible troops – cooks and clerks not excepted – were rallied, and the devastating defensive fire of the artillery made the German reconquests quite untenable. By noon the danger was past. Operation MICHAEL and the actions that developed simultaneously in the hills to the south cost the Germans well over 300 casualties and won not an inch of ground. Still, 36 US Division had been further exhausted, and while waiting in the concentration area 7 Indian Brigade was suffering casualties – at the rate of twenty an hour, according to report. Further, the same afternoon Germans began to infiltrate from the area of Terelle and the Indians had to face about and deploy two battalions in support of the Americans on Castellone. This diversion made it impossible to carry out the relief that night, and a twenty-four-hour postponement of the attack (already the second) followed as a matter of course.

The move of 7 Indian Brigade into the forward positions began at nightfall on the 13th, but the Indians’ troubles were not over. From Cairo it was a steep, strenuous climb of nearly four miles over a tortuous mountain track which had become rougher with the weather, and which was exposed to the fire of enemy guns and mortars throughout its length. The bringing up of supplies over battle-swept trails was then, and later, a feat of physical and moral endurance. Everything had to come up by night about five miles across the Rapido valley from the Portella area to Cairo village by tracks so deep in mud that the Indians’ vehicles were often stranded in the sloughs, and the loan of sturdier American trucks became necessary. Near Cairo the loads were transferred to mules; but as the mules were too few (they numbered about nine hundred) and in part ill-trained and unfit, they had to be supplemented by the equivalent of five companies of porters drawn from units in reserve. Then came the exhausting climb up to the front over tracks which an Indian pioneer company on permanent duty hewed out of the rock by hand. The front line could not be approached by day, the

forward posts being overlooked by the enemy from a few yards’ distance.

The relief that began at dusk on the 13th could not be completed overnight and it was 6 a.m. on the 15th when 7 Indian Brigade took over the sector. It deployed 1 Royal Sussex Regiment on Point 593 and 4/16 Punjabis on its left, occupying the ridge of Points 450 and 445.27 After a sustained show of bravery, the Americans were spent with fighting and weak from the frost and snow. Some who had been lying in their holes with frozen feet had to be carried out on stretchers.

(vii)

By this time General Freyberg was beginning to show something less than exasperation but something more than indifference at the continued delays. At Anzio the enemy was obviously on the eve of a maximum effort to destroy the bridgehead. General Alexander’s wish for the earliest possible action at Cassino was unmistakable. Freyberg could not but transmit this pressure. Moreover, there was a question of prestige: his immediate superior was an American and the Americans whom his corps had relieved had not concealed their belief that fresh troops would be able to complete the task the Americans had begun. On the other hand, Freyberg had committed the main attack to an Indian division whose commander was a locum tenens. Brigadier Dimoline’s problem was to find a firm footing from which to lunge forward in attack.

The situation in the hills west of Cassino was much more fluid and the forward posts there were much less secure than had been expected. The Sussex battalion’s hold on Point 593, for example, was decidedly tenuous. The hill had already changed hands more than once and now the Germans not only occupied the western side of the feature but were found to be firmly ensconced in the ruins of an old fort on the summit. Only recently, too, Point 569, 100 yards to the south, had been the scene of bitter hand-to-hand fighting between Germans and Americans. The enemy crossfire was so arranged that the

possession of one of his strongpoints could only be ensured by the possession of others. Each singly was a mere redoubt. Thus, just as the ridge of Points 450 and 445 immediately north of the monastery could be made untenable by enfilade fire from Point 593, so Point 593 was largely open to fire from Albaneta Farm, 400 yards to the west, and from Point 575, about 1200 yards to the north-west.

Dimoline, rightly or wrongly, thought that his difficulties were not fully appreciated. When at his request Kippenberger asked Freyberg to receive both of them together, the reply was a refusal to have ‘any soviet of divisional commanders.’28 Besides his troubles over deployment, though not unconnected with them, Dimoline had the deputy’s natural anxiety to hand back his temporary charge in good shape. He can hardly have failed to know that Tuker, whom he had been consulting, was concerned to avoid all needless casualties.29

After hearing a report from Brigadier Lovett, who had reconnoitred the front, Dimoline was convinced that the attack on Monastery Hill could not succeed until Point 593 was cleared of the enemy. He said so as early as the 12th, before his troops were in the line, and he maintained his opinion in the days that followed. Freyberg recognised the need for a firm base,30 but with the lapse of time he became more urgent for action. As the patience of his superiors waned and as the difficulties of the troops on the heights became increasingly apparent, Dimoline was ground between the upper millstone of strategy and the nether millstone of tactics. But on one point no such tension was felt. Freyberg and Dimoline were at one in considering the abbey on the hill to be a military objective.