Chapter 11: An Unwelcome Interlude

I: The Origin of DICKENS

(i)

THE failure of operation avenger had consequences both tactical and strategic. Tactically, it forced a reappraisal of what was fast hardening into the ‘Cassino problem’. Scarcely more than an hour after receiving the news that the Maoris had been driven back across the river, General Freyberg was revolving fresh ideas for reducing the fortress; and in assuming that he was not to resign the initiative he anticipated the thinking of the higher Allied command. For the defeat at Cassino, coming almost simultaneously with the enemy defeat at Anzio, displayed again the power of the defensive, called up endless vistas of deadlock and prompted a review of strategy in the Mediterranean theatre and of the way in which it could best serve OVERLORD. The relevant conclusion was that the battle of Cassino must be resumed.

(ii)

On 19 February General Wilson and General Alexander visited the corps front to see the craggy realities for themselves. Three days later Alexander formally addressed to Wilson an exhaustive appreciation of the situation in Italy and his plan for the future conduct of the campaign. His object was ‘to force the enemy to commit the maximum number of divisions to operations in Italy at the time OVERLORD is launched’, and he argued that it would most probably be fulfilled by a major offensive up the Liri valley, designed to link up with the bridgehead. But in order to attain the necessary local superiority of three to one in infantry, he would need another seven and a half divisions by mid-April to reinforce his existing twenty-one divisions, and he also proposed to regroup. Leaving a single corps on the Adriatic side, he would transfer the Eighth Army west of the mountain divide to take over the front as far south as the Liri. Fifth Army would command the sector from the Liri to the sea and the Anzio bridgehead, and would mount offensives from both as the Eighth Army struck up the Liri valley.

The same day, on the strength of these recommendations, Wilson placed his views before the British Chiefs of Staff. He had been under instructions to plan operation anvil (an invasion of Southern France in support of OVERLORD) with an assault landing of at least two divisions. He now contended that it would be unsafe to withdraw forces from the Italian battle until the main front had been joined up with the Anzio bridgehead, and urged concentration on the campaign in Italy, with an amphibious feint, as the best way of keeping the enemy employed. He advised the cancellation of anvil and sought a fresh directive in more general terms ‘to conduct operations with the object of containing the maximum number of German troops in Southern Europe’. Wilson’s plea was opportune. It arrived in time to clinch a compromise to which dissensions over anvil had already given rise.1

On the 26th, therefore, he received a new directive giving the campaign in Italy priority over all other Mediterranean operations until further orders. Alexander’s plan of a great spring offensive had in effect been ratified.

Wilson himself was hopeful that the incessant bombing of the enemy’s communications would compel him within two months to withdraw at least as far as the Pisa-Rimini line, thus limiting the Allied armies to the task of exerting continuous pressure to prevent a cheap disengagement. Alexander, with an eye to the weather, was more reserved about the effect of the air policy. But whether or not the spring offensive became necessary, both commanders were agreed that there must be no appreciable pause in bringing to battle the enemy’s eighteen divisions south of the Rome-Pescara line and, if possible, in drawing in the four and a half in reserve in the north. The longer the delay the stronger the enemy’s prepared defences. Nor could there be much doubt where he must be engaged. On the Adriatic the war was at a standstill. At Anzio 6 Corps, having survived, must now pause to recruit its strength. Only the Rapido-Garigliano front remained. Here the choice narrow ed itself down to the Cassino area. For one thing, Alexander wanted the Cassino spur cleared and a bridgehead established across the Rapido as an exit into the Liri valley when the spring offensive began, if exploitation was not possible earlier. For another, he had in Freyberg a commander on the spot with a plan that his corps was ready to execute.

That four weeks elapsed between its conception and its execution is an example, with a modern twist, of the perennial influence of mud on history – mud, this time, that prevented tanks from leaving the roads and aircraft from leaving the runways. For these four

weeks, until 15 March, the weather tried the New Zealanders and the Indians with a series of frustrating delays that blunted the edge of the enterprise, wasted them with casualties and sickness, drained the nervous energy of infantry at close grips with the enemy and sent all about their duties in fretfulness and wet-footed discomfort.

(iii)

When the third attack on Cassino failed on 18 February Freyberg lost no time in planning another. There was indeed no time to lose, since this was the day of crisis at Anzio. Freyberg’s choice lay among courses almost equally unattractive. Whatever his plan, the stark fact was that he was being asked to launch troops he thought too few on a major offensive at the most difficult time of the year, when river valleys were under water. A mere repetition of the double thrust on the monastery and the railway station would have invited defeat. Two other solutions to the Cassino problem lay open to the corps, the one more, the other less, of a turning movement than operation avenger. The more oblique approach was by a river crossing in the mouth of the Liri valley which might eventually outflank Cassino by uniting with an Indian advance descending into the valley from the hills north-west of the monastery. Though this choice would in fact have caused most alarm to the Germans, it did not appear any more attractive now than when, for various reasons, it had been rejected several days before.2 It had failed at high cost in January. In Freyberg’s mind the roading required to sustain such an attack was alone prohibitive. Kippenberger thought that the operation was feasible and in principle to be preferred to a direct assault on a fortress, but that if it failed it would fail disastrously with the loss of a large part of the Division, whereas failure at Cassino or in the hills above it would be only a repulse, not a disaster.

The town itself, then, would have to be cleared. An attack from the east would be terribly exposed to observation – the bridging would have to be done in the open – it would be hampered by flooding and demolitions, and it would encounter the most carefully prepared defences. The least disadvantageous approach was from the north. Here the Americans had won a footing in the outskirts, from which it would be necessary to advance south through the length of the town before the valley could be opened. The stout buildings of stone and concrete might offer some cover against fire and observation from the hillside on the attackers’ right flank, but they would also be desperately defended by the German parachutists and, in default of a ruinous house-to-house progress, they would have to be devastated by weight of high explosive and rushed before the

defenders could recover. The best way to deliver the high explosive quickly and in sufficient bulk was from the air. On the late afternoon of the 18th Freyberg advocated a careful plan to demolish the town by heavy bombers while the forward troops were withdrawn, and to follow the bombing instantly by infantry assault. Here was the pivot upon which all action turned for the next month.

Nor was action dilatory. After conferring with his own senior commanders Freyberg laid his plan before Clark at Army Headquarters on the night of the 18th. The next day he saw Wilson and Alexander, and that evening he returned from Army to Corps Headquarters with the news that ‘the attack on the village is on’. Having received general approval for his plan, Freyberg hastened to fill in the outlines. Early on the morning of the 20th he gave oral directions to his divisional commanders to start the necessary troop movements and other preparations. On the 21st the air and artillery policies were concerted at a conference attended by representatives of 12 Air Support Command, and late that night the corps’ operation instruction was issued. Briefly,3 operation dickens4 was an attempt to capture Cassino and establish a bridgehead over the Rapido by infantry and tanks attacking through the town after it had been pulverised by bombing aircraft used as siege artillery. Immediately after the air bombardment, the New Zealanders, under cover of maximum artillery support, would advance south from the northern outskirts of the town, with the Indians moving along the eastern face of Montecassino to guard their right flank. On capturing Cassino, they would exploit south to open up Route 6 and east and south-east to clear the enemy between the Gari and Rapido rivers so that crossings might be constructed. The date for the attack would be determined by the air command, but it would not be earlier than 24 February.

The decision to leave the air command to fix the date underlined Freyberg’s reiterated statement that without a full measure of air support the attack would have to be abandoned. The distinctive and indispensable feature of the plan – the use of the heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force in a tactical role – was not without

precedent, but the circumstances in which the weapon was to be tried were unparalleled in the West. Alexander and Freyberg could recall that in Africa concentrated aerial bombardment at Djebel Tebaga had been followed by an immediate break-through on the ground. Clark had noticed earlier in the month how close air support encouraged the troops at Anzio.5 But neither of these attacks was by heavy bombers. Twice previously, it is true, heavy bombers had given direct support to the army in Italy. Once was at Battipaglia, a crossroads village near Salerno, in September 1943, when great damage was done. But the experiment only led the Royal Air Force Review to cite the incident as illustrating the hypothesis that all-out bombing attacks on fortified towns were better suited to aid defence than assault. The other occasion, of course, was the bombardment of the abbey – an impressive demonstration of the power of heavy bombs to wreck massive buildings. But neither Battipaglia nor Montecassino was a true precedent, partly because of the smaller weight of the attack but mainly because ground troops had not followed up immediately. More apposite was the example of Stalingrad, where the Germans, having reduced the city to ruins by bombing, sent in wave after wave of tanks, only to have them halted by stubborn Russian defenders protected by rubble, the shells of buildings and bomb craters. A British War Office survey of this action concluded that it had proved to the hilt that ‘the ruins of a city constitute one of the most formidable types of fortifications in modern war’. Though this survey was published a year before the Cassino battle, it may not have been received or studied at Freyberg’s headquarters in time to be of use.6 Its main finding was, however, a commonplace of the First World War.

The ‘lessons of history’, military or otherwise, are in any event perilously easy to misapply. The idea of bombing a way through Cassino was not a product of diligent search for a precedent, but an urgent response to a practical challenge. It originated with Freyberg, who thought it would open up a new situation, and, with some exceptions, gained a fresh imprimatur at each stage upward in the chain of command. Clark had earlier pondered the use of strategic bombers in close battlefield support at Anzio, since their attacks on the rear areas for the last six months had not prevented the enemy from moving reserves at will.7 Alexander, thinking like Freyberg, welcomed the plan as a means of varying the tactics of assault. Major-General John K. Cannon, commanding the Tactical Air Force, thought that, given good weather and all the air resources

in Italy, it would be possible to ‘whip out Cassino like an old tooth’.8 Air Force officers at the conference on the 21st warned Freyberg that casualties might occur from misdirected bombs: this he accepted as the price of close support. To the further warning that bomb craters and rubble would produce perfect tank traps, he replied that if our troops could not use tanks neither could the enemy; he also thought that bulldozers could speedily clear a path. The final air force verdict at this conference was that a full infantry effort, if generously supported by gunfire and made immediately after the air attack, would have ‘a fair chance’ of taking the town. On the whole, the ground commanders and the air commanders accustomed to working with them viewed the plan experimentally as a possible way of breaking out of the impasse without risking great loss of life. They were in a mood to try anything, provided it cost materials rather than men.

General Eaker was less hopeful, though the plan was being urged from above as well as from below. For it so happened that about this time in Washington General H. H. Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces, was independently coming to the conclusion that the potentialities of mass air assault were not being sufficiently explored in Italy. He quoted Cassino as a place where the concentration of air power might achieve results if the ground forces could take full advantage of it. This suggestion, after being approved by the American and British Chiefs of Staff in turn, was passed on by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to Wilson, who was able to inform them that just such a plan was awaiting execution. Eaker cautioned Arnold not to expect a great victory because he doubted whether the air strike would wholly neutralise the enemy and whether the ground troops could adequately exploit their opportunity.9 The sybil has been less prophetic than this.

(iv)

The New Zealand Corps had several days to regroup for the attack, tentatively fixed for 24 February. The Indians needed a firm base whence to advance along the hillside above the town and check interference with the New Zealanders’ right. The preliminaries required of them, therefore, were the capture of Point 445, about 300 yards north of the monastery, and then the construction of positions along a line from Point 450 through Point 445 and eastwards down the spurs to the edge of Cassino, so that they could cover with fire the western outskirts of the town and the eastern slopes of Montecassino. The New Zealanders were to replace the Americans in the northern part of the town and astride

Route 6 to the east, and so to deploy as to be ready to attack and to engage the enemy with all possible weapons from the east bank of the Rapido. The Americans still in the line north of the Indians were to be relieved by the French Expeditionary Corps. Second United States Corps would then form a new Fifth Army reserve.

In the hills above Cassino the forward Indian infantry kept cheerless vigil in slit trenches and rock sangars that were difficult to improve because of the close proximity of the Germans. For these troops the harassing fire of machine guns and mortars made movement impossible by day and chancy at any time. Though the porters provided by 11 Indian Brigade were reinforced eventually by three Indian pioneer companies, porters as well as mules remained too few to bring up more than meagre supplies of rations over the steep, rugged tracks. Rain and snow further tested the Indians’ fortitude.

The intention to reorganise on a two-brigade front was carried out on the night of 19–20 February, when 5 Indian Brigade took over the eastern half of the sector from 7 Indian Brigade; but the relief had no sooner been completed than the new corps plan of attack foreshadowed its undoing. Operation dickens called for a fresh Indian brigade to be held in readiness to join the New Zealanders in the assault on Cassino. Seventh Indian Brigade was sorely depleted and 11 Brigade was dispersed on various assignments. Fifth Indian Brigade was thus the only one available for the assault and would have to be drawn back into reserve. Meanwhile one of its battalions, 1/9 Gurkha Regiment, essayed the preliminary task of seizing Point 445. Its silent attack on the night of 22–23 February ran into unexpectedly strong resistance and recoiled before punishing mortar fire. Thereafter, Point 445 was resigned to the enemy and 7 Brigade had to adjust the line of the new positions which it now dug and fortified east of Point 450 down the hillside to cover Cassino and Montecassino.

The relief of 5 Indian Brigade was scheduled for the night of 23–24 February in the expectation that the attack would begin on the morning of the 24th, but heavy snow delayed for twenty-four hours the relief of 1/9 Gurkhas by 2/7 Gurkhas. This last battalion and 2 Cameron Highlanders (in reserve), both of which belonged to 11 Indian Brigade, now came under command of 7 Indian Brigade, which resumed responsibility for the division’s sector. With 5 Indian Brigade back in reserve round Cairo village, the Indians had positioned themselves for the corps’ offensive.

For the New Zealand Division the interval between the actual end of avenger and the presumed beginning of dickens was likewise a period of preparatory reliefs and explorations. The main

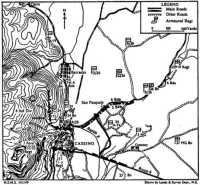

New Zealand dispositions north of Route 6, 24 February 1944

reshuffle was north of Route 6, where 6 Brigade (Brigadier Parkinson) and elements of 5 Brigade (Colonel Hartnell) replaced the Americans. On the right, 6 Brigade took over from 133 United States Regiment a wedge-shaped sector, with the blade of the wedge forming the ‘front’, only about 500 yards broad, among the buildings in the northern part of Cassino. The western or right-hand boundary lay against the hillside, resting on the positions being dug by the Indians. The left-hand boundary ran away north-east from Cassino along Pasquale road, so called because it passed through the hamlet of San Pasquale. Caruso road led almost due north out of the town along the foot of the hill, cutting through a military barracks before trending westward to Cairo village. The course of the Rapido lay beside Caruso road almost as far as the barracks, and east of it again ran Parallel road, which merited its name but for a slight divergence to the north-east.

The battalions of 6 Brigade, moving in under wireless silence on the night of 21–22 February, proved an awkward freightage for the

vehicles of 6 Reserve Mechanical Transport Company, which had to carry them over narrow, muddy, devious lanes to debussing points only hundreds of yards from the front line. Though one loaded truck lurched over a bank and capsized, no harm was done to the occupants, and shortly after midnight the infantrymen had all been delivered safely. For the drivers the journey back over the return stretch of the traffic circuit was a waking nightmare. Gun flashes dazzled the men at the wheel, momentarily dispelling the murk of the night and then leaving it more impenetrable than ever. Overhead, branches clutched at canopies and ripped them. Reserve drivers had to walk ahead to pick out the route. Rough tracks and ditched tanks and trucks reduced progress to a crawl, two miles in the hour.

Meanwhile the infantry of 24 and 25 Battalions (Lieutenant-Colonel Pike and Major Norman) had been met at the barracks by American guides and conducted to their positions. The changeover was completed not long after 3 a.m. The brigade’s forward area, now occupied by four companies, was five or six hundred yards square, with its extremities at Point 175, a knob protruding from the lower slopes of the hillside, and at the eastern edge of the town 100 yards south of the junction of Parallel and Pasquale roads. From the right the positions were held by C and D Companies of 24 Battalion (Major J. W. Reynolds and Captain Ramsay)10 and B and A Companies of 25 Battalion (Captain Hoy11 and Major Sanders).12

The area was sprinkled with buildings which closed up to each other in 25 Battalion’s sector to form part of the town. Here the enemy manned posts a street’s width away. Almost as near in appearance and by no means remote in fact was Point 193, known as Castle Hill from the towered and castellated stone building on its summit. Not so much a hill as the tip of a spur running down from Montecassino, Point 193 showed to the north a cliff face dropping sheer into a deep ravine and hollowed into caves and dugouts where machine guns had been emplaced. The obtrusive tactical strength of this feature ensured sooner or later a deadly game to be king of the castle, but for the time being the Germans held possession and with it command over all 6 Brigade’s forward positions. Walls and roofs saved the New Zealanders from the worst consequences of this surveillance. More active self-defence was the siting of 3-inch and 42-inch mortars and of six-pounder anti-tank guns and the manning of mined road blocks north of the town. The reserve companies in bivouac areas on the slopes of Colle Maiola, being at a safe distance from the German infantry, were continually harassed by the German guns.

The brigade’s reserve battalion, the 26th (Lieutenant-Colonel Richards)13 scattered its companies in the angle of country enclosed by Parallel and Pasquale roads. The tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel McGaffin), now under command of 6 Brigade, moved into the same area ready to give weight to the attack through the town.

On 6 Brigade’s left, between San Pasquale and Route 6, the Americans of 91 Reconnaissance Battalion had already handed over on the night of 20–21 February to New Zealand anti-tank and machine-gunners holding the line as infantry. This improvised force under 27 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel MacDuff)14 formed the right wing of 5 Brigade. With 34 Anti-Tank Battery on the right and 3 Machine Gun Company on the left, it held a ring of outposts set three or four hundred yards back from the Rapido, which in this area on the eastern approaches to Cassino had overflowed its banks and created that most irksome of all military obstacles – a marsh. One of several patrols sent to scout along the river on the night of 22–23 February had to plod through a foot of mud for the last 50 yards and failed to find a crossing.

Another round of reliefs occurred farther south on the front held by 5 Brigade since 6 February. After the Maoris’ withdrawal on the 18th command of the Rapido River sector facing the railway station passed to 24 Battalion, which redisposed its platoons and brought up anti-tank guns to prevent the enemy from pressing home his success by attack along the railway line. A battalion front of more than 5000 yards was almost equally divided between A Company, from Route 6 to the Ascensione stream, and B Company, from the stream south to the boundary with the Divisional Cavalry Regiment. The arrangement was short-lived, for on the night of 19–20 February 24 Battalion was relieved to rejoin its brigade and 23 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. J. Connolly) took over its commitments. The incoming battalion deployed C Company (Lieutenant Coe)15 on the right and D Company (Major Slee)16 on the left of the railway sector and sent B Company (Captain F. C. Irving) to replace 24 Battalion’s C Company, which was guarding the Division’s left flank under command of the Divisional Cavalry.

Though the Germans did not follow up across the river, they showed every intention of holding what they had. A 24 Battalion

patrol found them wiring their defences round the station and the hummock. Heavy shellfire fell forward of Trocchio. Efforts were made to block an attacker’s routes of approach. Concentrated gunfire on the Bailey bridge erected by the New Zealand sappers over the Rapido scored a direct hit and left the bridge sagging, with holes in both ends of the decking and part of the western end blown away. Nevertheless, it was still judged worth protecting, and 23 Battalion continued to cover it nightly by a standing patrol. About the same time, according to German reports, the commander of a 210-millimetre troop personally ranged his guns on the road bridge and destroyed it, though not so thoroughly as to deter an enemy engineer patrol which fought its way to the bridge and set off another demolition. Repairs to the railway embankment were engaged by the always troublesome German mortar crews.

The enterprise of enemy patrols kept the New Zealand infantry on edge and tempted sentries to fire at shadows. One night, in what the Germans justifiably called ‘a bold and skilful assault’, a patrol from I Battalion 129 Panzer Grenadier Regiment ambushed Second-Lieutenant Esson17 and a sergeant of C Company 23 Battalion on their rounds and spirited them away with such silent efficiency that the mystery of their disappearance was only unveiled after the war.

By the 22nd, when 6 Brigade had relieved the Americans north of Cassino, the New Zealand Division was extended to the limit to hold a front that stretched continuously for six miles or more from the slopes of Colle Maiola to the Ladrone stream, the boundary with 10 Corps. It had had to improvise infantrymen to man this length of line. And it was preparing to participate in a major offensive. General Freyberg therefore decided to commit part of his third division on the southern flank of the corps to reduce the New Zealanders’ responsibilities.

This new force was 78 British Division (Major-General C. F. Keightley), the last of five to be transferred in recent weeks from the Eighth to the Fifth Army. It crossed Italy in the first half of February and came under New Zealand command on the 17th. Since it was to be used if possible only for the pursuit, Freyberg assigned it no active part in the coming assault, but it was to be ready with bridging material to cross the Rapido in support of the New Zealanders’ exploitation if required to do so. Meanwhile, on the night of 23–24 February, its 11 Brigade relieved the Divisional Cavalry and B Company 23 Battalion on the Rapido, sending 1 East Surreys forward and keeping the other two battalions (5 Northamptonshire Regiment and 2 Lancashire Fusiliers) in reserve.

II: Waiting For The Weather

(i)

The infantry had now been deployed, the armour was disposed for the assault and break-through, and the artillery had built up the ammunition for its huge programme of supporting fire. All awaited the propitious hour. Such was an hour in which the ground was dry enough at bomber bases as far apart as Foggia and Sardinia to allow the aircraft to take off, the weather ‘flyable’ between these bases and the target, and the Liri valley firm enough to enable tanks to exploit. The last condition necessitated three fine days before the operation, with the promise of two more to follow; and the whole combination was asking a good deal of a February in Latium. But Freyberg was prepared, indeed determined, to wait for it. The 21st and 22nd were fine, bracing days, but the 23rd broke dull and overcast, and soon after midday heavy thunder showers and snow in the high country ruined any prospect that the operation might begin next day. A postponement of twenty-four hours was ordered.

So began the long period of hope deferred, until the code-word dickens became a symbol for heartsick frustration and the operation it signified a mirage receding with the horizon. Day after day for three weeks the delay dragged on, while the corps stood ready to advance at twenty-four hours’ notice. Taihoa (by and by) became the watch-word of Maori and pakeha alike. From the 23rd for the rest of the month and well on into the first week of March the wet, cloudy weather persisted, with only an occasional ‘drying wind’ to give hope a pretext. The 7th was the first of several fine days, but by this time the ground was so saturated that the armoured commanders were unanimous that four days’ drying would be needed for the tanks to deploy and another two for them to exploit. Hints from Army Group that a time limit might have to be set caused Freyberg to meditate a more restricted operation which might at least relieve enemy pressure at Anzio. By the 9th tracks had hardened so well that the prospects for the next day seemed favourable. Then it became known that bad weather had waterlogged the Foggia airfields and that the bombers were earthbound. There was a similar disappointment on the 13th, but the 14th was to be the last day of waiting.

One of the most grievous consequences of the delay was the mood of pessimism that settled down on the corps. None could fail to see that time lost to the attacker was time gained to the defender. The Germans used it to perfect their defences, regroup their forces, and move their best troops into the Cassino sector. But once the plans were laid and the troops in position, the New

Zealand Corps had no preparations upon which to busy itself. A sense of staleness, physical and psychological, was inevitable. On 2 March, when spirits were beginning to droop, Freyberg gathered his divisional, brigade and battalion commanders in conference, explained his plans to them and sent them away with a glow of optimism. At Corps Headquarters so long as General Gruenther’s voice came up on the telephone cheerfulness kept breaking in. His sallies about the weather, his studious helpfulness, his encouraging prediction of how the spadger terrier would fasten upon the German mastiff and make it squeal – all helped to hold gloom at bay. But enforced idleness gave time to dwell on the difficulties of the operation, and these were nowhere disputed from the highest ranks downward. On 23 February Alexander wrote to Freyberg: ‘I put great store by this operation of yours. It must succeed....’ Yet he was obviously doubtful whether exploitation would be possible. On the 28th Clark said that the New Zealand attack had a 50–50 chance. Freyberg himself commented privately on 2 March that he had never been faced in the whole of his military career with so difficult an operation. Kippenberger compiled a list of ‘Blessings’ and ‘Troubles’ and used it to confound the doubters.18 At least one brigadier was worrying a good deal.19 Among the troops the effervescence that bubbled up on the announcement of the bombing programme subsided into flatness.

The promised spectacle was indeed for so long a topic of conversation throughout the corps, in rear areas as well as forward, that security was imperilled. It seemed impossible that warning of the operation should not have reached civilian or even enemy ears. On 2 March an order by 2 New Zealand Division forbade mention of dickens over the telephone. Before this, the wireless silence enjoined by the Division’s operation order had had to be relaxed because of the frequent cutting of telephone lines by shellfire.

The New Zealand Division was losing about ten battle casualties a day. Sickness was on the increase. The number of men evacuated sick in February was 813, against 693 in January, and during the first half of March the rate continued to rise. Four drafts of reinforcements in late February and early March brought about 950 fresh men to fill the gaps in all arms of the service.

One gap was bound to be seriously felt. On the afternoon of 2 March, an hour after leaving General Freyberg’s conference, General Kippenberger was severely wounded in a minefield on Trocchio, to the great distress of all New Zealanders in the field. He was succeeded in command of the Division by Brigadier Parkinson, and Lieutenant-Colonel I. L. Bonifant took over 6 Brigade.

Command of the Divisional Cavalry devolved upon Major Stace.20

The long pause was unvaried by any notable clash of arms. For the most part it was a trial of patience rather than a provocation to élan. Except among the hills north of the monastery and in Cassino town, where close contact was always likely to generate combustion, the front was quiet. Forward areas, gun positions and roads were the main targets in the exchanges of artillery and mortar fire that accounted for most of the daily activity. The deeds of the corps will be most conveniently described sector by sector.

(ii)

On the storm-swept Montecassino spur 7 Indian Brigade suffered most of the torments of a winter war waged against a determined enemy. Joined rather than separated by a no-man’s-land that narrowed down to 100 or 50 yards at places, both sides were quick on the trigger and harried one another with mortar bombs and rifle grenades. The Indians steadily lost about sixty men every day from fire on forward posts, reserve areas and supply tracks, and from sickness due to exposure to snow and rain. The German parachutists made at least three raids on the Indian positions around Point 593 and Point 450, but each was beaten off with the help of gunfire. On the evening of 9 March German rifle grenades ignited a dump of petrol in 2 Camerons’ area, and before it could be put out the fire caused an explosion of ammunition which wounded nine men. The enemy’s ingenuity showed itself more than once. He replied to our own propaganda offensive with shell-borne pamphlets written in Urdu, and on the night of 13–14 March he embarrassed the troops on Point 593 by holding it in the beams of a searchlight believed to be sited at Aquino. The Indian brigade was able to afford some relief to its battalions during this period. 1/2 Gurkha Rifles continued to hold the right flank, but 1 Royal Sussex and 2/7 Gurkha Rifles were gradually replaced in the centre and on the left by 2 Camerons and 4/16 Punjab Regiment respectively.

To counter the chronic shortage of mules, the Indian engineers put in continuous work during February to make the supply track fit for the use of vehicles. Cavendish road, as it was called, was a steep, winding track that rose 800 feet in a mile and a half. On the top of the rise on the north side of Colle Maiola, at a point known as Madras Circus, it came out on to comparatively level ground, and fairly easy foot tracks led from there to the forward areas. Towards the end of February General Freyberg and his chief engineer, Brigadier Hanson, revived an earlier idea of developing the track as an

axis for tanks. If Cavendish road could be made wide enough as far as Madras Circus, tanks might achieve such surprise in this seemingly tank-proof country as to capture Albaneta Farm and exploit to Montecassino. The better-equipped New Zealand engineers were directed to assist the Indians. Daily and all day from 3 to 10 March, save when rain interfered, a party of New Zealand sappers, with their compressors and bulldozers, followed up the Indians working with pick-axes and crowbars, and drilled, blasted and cleared away the rock through which the upper part of the road had to be cut. Exposed stretches of the road were camouflaged with nets in the hope of keeping the tactical secret. By the night of 10–11 March the road was fit for tanks as far as Madras Circus. From that night a force under command of 7 Indian Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron, including 17 Stuart tanks of an American battalion and the 15 Shermans of C Squadron 20 New Zealand Armoured Regiment, stood by to exploit to Albaneta and Montecassino as soon as operation dickens had made some headway. The French Expeditionary Corps, through whose area most of the road ran, readily agreed to allow the Indians to site anti-tank guns along it and to use it for operations if necessary.

Because it was to launch the assault, 6 New Zealand Brigade perhaps chafed more than other formations at the wasteful delay. The infantry companies in the northern parts of Cassino had to listen nightly to the strengthening of defences they hoped soon to attack and were powerless to do more than call down artillery fire – at best a temporary remedy. The period of waiting cost 24 Battalion 28 casualties and 25 Battalion 47 from German fire and many more from sickness. Men in the forward posts led a troglodyte existence under the shelter of stucco, stone and tiles, emerging only at night to stretch their limbs and take a breath of fresh air. Their cramped, insanitary places of refuge and the dank weather threatened an epidemic which only good doctoring and the disinfecting of buildings held in check.

Holding the line inside a town was a new and nerve-racking experience to most of the New Zealanders. The ‘line’ was as artificial as an electoral boundary, merely the forward edge of the buildings held by the Americans when their last attack lost its impetus, buildings whose size and shape acquired sudden military interest and whose dead architects, having designed thus and not otherwise, ruled men’s lives from the grave. Not only from neighbouring buildings but also from the rocky face of Castle Hill German snipers, machine-gunners, and mortar crews watched every movement and fired at every target and every suspicion of one.

Communications with the forward posts of 24 and 25 Battalions

were patchy. Wireless had often to be used while the signallers carried out the uncomfortable and dangerous work of repairing telephone lines. Those bringing up supplies also had to expose themselves at short range. As motor vehicles could not approach within half a mile of the town, large carrying parties from the companies in reserve had to run the gauntlet of fire every night. In fact, the enemy had the northern environs of Cassino so well registered with his weapons that at this time more casualties were suffered on the roads and in the reserve company areas than in the FDLs.

To ease the strain of life in Cassino 25 Battalion made frequent reliefs. B and A Companies formed one pair which alternated in the forward positions every three days with D and C Companies (Major S. M. Hewitt and Major Robertshaw).21 As safety demanded the utmost stealth, companies moved one platoon at a time at long intervals. Being farther from the enemy, 24 Battalion had to relieve only one platoon during this period. Most of the patrolling fell to 24 Battalion, which sent out parties north and south to keep in touch with the Indians and 25 Battalion respectively. The battalion also posted standing patrols and laid mines against infiltration up gullies to the south and west. Twenty-fifth Battalion had more brushes with the enemy. One was occasioned by the unsuccessful attempt of a German fighting patrol to blow down the wall of a house by an explosive charge, and another by the enemy’s too obvious efforts to fortify a nearby school and nunnery. But on the whole both sides in Cassino town agreed that there was little scope for mobile patrolling and contented themselves by firing their weapons from permanent positions.

Meanwhile, 26 Battalion performed the task – in every respect more pedestrian – of securing 6 Brigade’s rear areas with standing and roving patrols and of protecting and assisting the engineers of 7 Field Company. The system of roads was reconnoitred and reported on, swept for mines, drained and repaired. A bridge was replaced, a ford was improved, a track giving emergency access to Cassino was put in order, the demolition of walls by the Rapido was prepared so as to provide an alternative crossing for tanks; elsewhere a gap in the riverbank was sealed to prevent flooding and a river gauge was installed from which the height of the water was reported each morning. Between 6 and 15 March the Rapido dropped nearly a foot. And thanks to the work of the engineers, 6 Brigade’s rear area was in much better shape for the supply and support of the coming attack.

There was little to report from 5 Brigade, which on 28 February passed from the command of Brigadier Hartnell, who left on

furlough, to that of Colonel Burrows.22 Most of the action on this broad front centred on the road and railway crossings of the Rapido east of Cassino. Though the marshy ground in front of 27 Battalion’s sector made patrolling pointless, the blown bridge on Route 6 was inspected, and for the last week of the period 3 Machine Gun Company maintained a listening post each night at the flooded 30-foot demolition. The Germans were also interested in this spot and several skirmishes occurred. The Bailey bridge at the railway crossing was in the sector held by 23 Battalion until the night of 28– 29 February and by the Divisional Cavalry until 5 March, and was finally shared by the two units, with A and B Companies of 23 Battalion on the right and A and B Squadrons of the Divisional Cavalry on the left. On the night of 3 March a Divisional Cavalry patrol led by Second-Lieutenant Kingscote23 shot a German sentry at the bridge, and the next night a listening post was set up in the vicinity. The brisk enemy reaction to probing movements suggests that for nights on end both Germans and New Zealanders had men listening intently on their proper sides of the damaged bridge. Farther south also the Rapido was kept under observation, and the movement of men and vehicles on the far bank was regularly engaged by 23 Battalion and the Divisional Cavalry.

The main engineer work on this front was to bring the railway line into use for vehicles. Reconnaissance by 6 Field Company revealed about twenty demolitions in the five or six thousand yards short of the point where repairs had begun for operation avenger. Many of the demolitions were only blown culverts, but there were so many interruptions on account of the weather, the softness of the ground and enemy shelling, that by 14 March the line had been cleared only for about 2000 yards to the point where it passed round the south-western shoulder of Trocchio.

The southern sector of the corps front was held by 1 East Surreys of 78 Division in country so featureless that its northern boundary was defined as the 17 northing line on the map. The battalion patrolled aggressively but with little luck. Reconnaissance patrols to inspect the river and its approaches, fighting patrols to seek out and strike, engineer patrols to dump bridging material, standing patrols to listen and learn or to protect, ambush patrols to lie in wait, patrols to lift mines, all were sent out but the results were disappointing. Most returned with negative reports and some lost men on

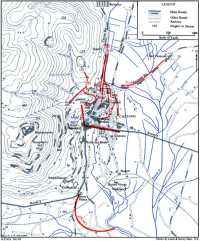

Operation DICKENS, 15 March 1944

mines or to enemy lurkers. Engineers of 78 Division spent the period of waiting in improving and draining roads in the forward areas against the day when the division should be called to exploit.

(iii)

The gunners manning the truly formidable armament of the corps were hardly aware of the existence of a lull. For them nearly every day brought a full day’s work, made the more onerous by the greasy mud that turned gunpits into porridge-pots and access tracks into slippery lanes of penance, negotiable only on foot or by jeep. The gunlayer had to leave his sights and lend a hand to pass the ammunition. All possible gun areas on the corps front were so congested that a troop counted itself lucky to find an alternative position as much as two or three hundred yards away. The many troops and batteries unable to move found that with the constant vehicle and foot traffic of two weeks or more their positions became glutinous lakes, and further that enemy shellfire gained in accuracy.

The guns of the New Zealand Corps had a glutton’s appetite. On two days in late February the New Zealand ammunition point, which catered for all the British field and medium artillery in the corps, temporarily ran out of 25-pounder shells, but for some time thereafter 19,000 rounds came in every day to 1 Ammunition Company. The heavy expenditure of the previous weeks was abruptly curtailed on 8 March, when the field artillery was rationed to twenty-five rounds a gun daily and the medium artillery to twenty. These amounts were ample for holding the line, especially as by this time the corps had clearly demonstrated its massive ascendency in gun power. A measure of its superiority may be guessed from two recollections of Brigadier Weir:

Once while observing from the castle on Mount Trocchio I saw a single German emerge from a hole near the Gari just south of the Baron’s Castle and walk quietly south. He was engaged by a holocaust of fire, including that of 8-inch howitzers. As he heard the shells arriving he ran and escaped into an underground shelter. Another time I plainly saw a three-gun self-propelled battery emerge from Santa Lucia and go into action north of Route 6. I gave no orders but merely watched. In a matter of a few minutes hundreds of shells arrived and smothered the three guns, leaving them blackened skeletons.24

Assembled for a great attack, the artillery at Brigadier Weir’s disposal was more than abundant for routine tasks. To the 216 field guns of the three divisions had to be added more than 150 field and medium guns of 2 AGRA, as well as the medium and heavy artillery of 2 United States Corps. By a rough division of labour, the

harassing fire by night and the observed fire by day were shared among the various groups of guns, most of the defensive fire tasks were allotted to the divisional artillery, and most of the counter-battery work to the corps and army artillery.

The harassing policy was not to scatter the fire widely at any one time but to concentrate guns on vulnerable spots such as crossroads and bridges and localities where the enemy had been seen and to change the targets nightly. Good shooting by the heavier calibres gave the Germans a supply problem in the Liri valley. A direct hit on the bridge at Pontecorvo closed the last crossing of the Liri in the forward area, and later the destruction by shellfire of a bridge on the Pontecorvo–Pignataro road seriously hindered supply traffic north of the Liri. The Germans wryly admired the accuracy of their opponents’ harassing fire but were professionally disdainful, if thankful, for their failure to block Route 6 and their repetitious and fruitless tactic of firing heavy concentrations south of the Abbey-Albaneta ridge. Another form of harassing, of which the Germans leave no official record, was the weekly delivery by gunfire of the Frontpost, a sheet containing all the news most likely to depress its readers.25

Most of the defensive and observed fire fell on Cassino, Montecassino and the country near the Rapido. Defensive fire proper was rarely required because the enemy did not threaten attack. Hardly a night passed, however, without a demand from the infantry for defensive fire tasks upon working parties or the movement of vehicles across the Rapido. This abuse of an emergency call disclosed the defensive fire areas and taught the Germans to avoid them. In Cassino itself gunfire was often requested for work that infantry weapons could have done more effectively.

But the gunners rarely grudged a round, as the lavish, almost improvident, scale of their observed shooting showed. Visibility was frequently poor, and it was because it blinded our own observers as well as the enemy’s that the experiment of screening our gun areas by laying smoke between Trocchio and Porchio was not repeated. But on clear days no enemy movement escaped the eyes of artillery observers. One result was that movement was rarely to be seen and the front looked as uninhabited as an artillery practice range. To this generalisation there was one exception – ambulances showing a red cross frequently moved up and down Route 6. After repeated reports that these vehicles were discharging and loading troops with arms, Headquarters New Zealand Artillery gave permission to fire on them.

Overborne as they were by the volume of gunfire from the New Zealand Corps, the German gunners were an oppressed class. On 20 February 2 AGRA came under command of the corps to direct the counter-battery programme. The result was immediate. On the 22nd, General Baade, commanding 90 Panzer Grenadier Division, wrote:

Worthy of note is the fact that the enemy uses two or three rounds of smoke for ranging. Usually the first round is right on the target. Our gun positions are pin-pointed and usually shelled as soon as they open fire. The shelling of our rear areas by heavy guns is extremely accurate and well organised, leading to the conclusion that the enemy has just detailed a special group of guns to engage long-range targets. The enemy has obviously changed his artillery policy.

The high priority given to counter-battery work, which during the rationing period claimed half the ammunition, paid valuable dividends. Of the four main groups of German artillery – round Vallemaio, Pignataro, Piedimonte San Germano and Atina – the second, being in the Liri valley, felt the full weight of our metal. Their fire varied with the visibility and was aimed principally at crossroads and bridges on Route 6 and at infantry areas and gun positions. Two types of German gun were very elusive. One was the self-propelled gun, which would use the roads, firing each time from a fresh position. The other was the 170-millimetre gun, whose range of 29,000 yards put it beyond the reach of any artillery in the corps.

Most of the German artillery, however, was unprotected by either mobility or distance. It was located by the use of air photographs, ground observation posts, the flash-spotting and sound-ranging of 36 Survey Battery and – most galling of all to the Germans – the air OPs which continually hovered over their gun areas. The commander of 414 Artillery Regiment complained bitterly of the lack of air protection in the Liri valley:

... enemy artillery OP aircraft circle round our positions for hours at a time. ... Some of them fly very low and slowly. ... They often appear unexpectedly, and it is quite a common thing for some of our guns to be caught firing by one of them, and their exact position thus betrayed. The enemy is able to range undisturbed on our guns, bridges and other worthwhile targets. Losses, casualties and supply difficulties arising from destroyed bridges are daily occurrences, while our artillery is hampered not only by the ammunition shortage but also by the lack of cover from view against these aircraft.

This commander found chapter and verse for these complaints in the sufferings experienced by one of his heavy batteries under the plague of air OPs. With two of them overhead, it had taken one troop several hours to range on a Rapido bridge; another troop, observed responding to a call for defensive fire, shortly afterwards lost six men killed and wounded from shellfire and a fighter-bomber raid;

finally, an air OP ranged British heavy guns on battery headquarters, which was forced to move by persistent shellfire.

A document captured about 23 February admitted the accuracy of the counter-battery fire and ordered German gunners to stand by their guns even while they were being shelled. Later, 14 Panzer Corps had a plan to use captured Italian guns for routine work and to move the German guns to positions as yet undiscovered by the enemy, where they would be reserved for emergencies.

The nests of nebelwerfers at Pignataro and Piedimonte San Germano were also severely handled whenever they opened fire. Often they came into action only once or twice a day, usually in the evening when the westering sun hindered observation from the Allied side, and sometimes they were silent for days at a time. On 20 March, during the battle for Cassino, General Senger reported that ‘the whole area round the nebelwerfer positions has been ploughed up and reploughed until it looks like the front lines of the Great War’.

The German mortars were harder to tame, in spite of elaborate programmes for that special purpose. Fifty-five mortars had been claimed as located by 14 March, more than half in the Liri valley and the rest in Cassino and the hills north of Route 6. These last were almost immune from shellfire, though it was during this time that the New Zealand artillery began to practise shooting in the upper register, that is, at angles over 45 degrees, which gave projectiles a high, lobbing trajectory and enabled them to search steep reverse slopes.

(iv)

The Germans were too battle-wise to construe their victory of 18 February as an augury of peace and quiet, but they welcomed the respite as an opportunity to strengthen their defences and to unravel the tangle of their command. On 4 March Field-Marshal Kesselring noted the transfer of the New Zealand, Indian, and 78 Divisions from the Eighth to the Fifth Army and made the obvious deduction that the attempt to force the Liri valley would be renewed. Long before this, on 21 February, 90 Panzer Grenadier Division, as the formation on the spot, foresaw another attack at Cassino and hastened to give depth to its positions. It assembled more assault guns and anti-tank guns just west of Cassino, brought up a fresh field battery to support the troops in the town, and began to replace tired troops by newly-arrived parachutists. By this time Senger was confident that with the paratroop battalions streaming in Cassino could be held, but he was doubtful whether the weakened front of 15 Panzer Grenadier Division could weather a major attack. The

artillery of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division therefore prepared to support its southern neighbour.

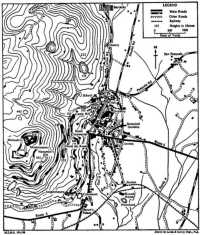

On 25 February 90 Panzer Grenadier Division relinquished its sector to 1 Parachute Division and retired for a well-deserved rest. The new master of Cassino, Lieutenant-General Richard Heidrich, was the aggressive commander of an aggressive division. An officer of machine guns in the First World War, Heidrich had fought against 2 New Zealand Division in Crete as commander of 3 Parachute Regiment and was known to be strict and ambitious. Now he led one of the élite formations of the whole German Army, composed of volunteers, many of whom had made several parachute jumps into enemy territory. As the monks whose abbey they now defended were dedicated to peace, so they were single-mindedly dedicated to war. They were physically and mentally toughened and were trained to perfection. Their steadiness in action was renowned. The division had a ration strength of about 13,000 and a fighting strength of about 6000. It was excellently equipped, particularly with light automatic weapons and anti-tank guns. It at once set to work to construct dugouts in the houses at Cassino, strengthening cellars with concrete, and to fortify the hills above. The defences were deepened by siting heavy machine guns behind the front line, positions were prepared for a line of anti-tank guns, and a reserve of supplies was built up for use by the forward troops should Route 6 be cut behind them.

Growing confidence even induced 14 Panzer Corps to contemplate a pincer movement on Cervaro in order to cut off the enemy north of Cassino; but the plan had to be postponed immediately for lack of troops to carry it out and indefinitely pending the liquidation of the Anzio bridgehead.

The corps made good progress in straightening out its divisions. By 14 March the pattern of command was much tidier. The defenders of the railway station, 211 Regiment, had been sent to join 71 Division on the Garigliano. South of Cassino 104 Panzer Grenadier Regiment resumed command of all three of its battalions and released the remaining units of 129 (now 115) Panzer Grenadier Regiment for service at Anzio. In the Terelle-Belvedere sector to the north, 44 Division now had none but its own regiments.

The parachute division’s sector lay between the mouth of the Ascensione stream on its right and the deep ravine north of Castellone on its left. Its right flank was held by 3 Parachute Regiment (Colonel L. Heilmann), with I Parachute Machine Gun Battalion south of Cassino, II Battalion in the town and III and I Battalions on Montecassino. In the centre was 4 Parachute Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel R. Egger), with II Battalion at Albaneta and III and I Battalions on Colle Sant’ Angelo. Among the hills on the left, I and

II Battalions of 1 Parachute Regiment held Pizzo Corno, facing Castellone, and IV Alpine Battalion was on Monte Cairo. The garrison of Cassino town was estimated at about 500 men.

Although in a general way the German command read the Allied intentions correctly, it went astray in detail. For a reason not yet clear, the New Zealand Division was believed on 8 March to have left the corps front, but the Germans were puzzled and urgently wanted prisoners to confirm the report. Five days later the New Zealanders’ whereabouts was still a subject of anxious speculation, and when General Westphal demanded a prisoner he had to be told that ‘the fish are not biting there at all’. The timing of the coming offensive also escaped the Germans. The long lull gave at least one advantage to the New Zealand Corps – it made last-minute troop movements unnecessary. The German intelligence therefore had no warning by way of regrouping or reinforcement in the forward areas and the patrolling was too light to give any indication of the impending attack.

(v)

The final New Zealand Corps plan of attack did not differ materially from the orders originally issued on 21 February. Before dawn on D-day the Indian and New Zealand troops would withdraw to a safety line 1000 yards from Cassino. The air bombardment of the town would begin at 8.30 a.m. and last until noon. Ten groups of heavy bombers and six groups of mediums, nearly 500 aircraft in all, would drop more than 1000 tons of 1000-pound high-explosive bombs on a target measuring about 1400 yards by 400. The attack would be delivered by relays of medium, heavy and medium bombers in that order, rising to a crescendo as midday approached. Late arrivals would be diverted to targets outside the town. In the afternoon fighter-bombers would be on call for prearranged targets on the southern edge of Cassino.

Zero hour for the ground troops was fixed for midday. At that time 6 Brigade was to advance at the deliberate rate of 100 yards in ten minutes to the capture of Point 193 and the whole of the town north of Route 6. It was to be preceded by a creeping barrage fired by the artillery, escorted by the tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment, supported on the right flank by the fire of 7 Indian Brigade from its prepared positions on the slopes west of the town, and protected from frontal fire by the anti-tank guns and small arms of 5 New Zealand Brigade and Combat Command ‘B’, which were ordered to engage enemy localities in Cassino south of Route 6. A battalion of 5 Indian Brigade was to take over Castle Hill as soon as possible after its capture. It was hoped to complete this first phase (objective quisling) by 2 p.m.

Cassino Town

In the next phase 6 Brigade would continue southward to clear the rest of the town and establish a bridgehead by seizing the road junction near the Baron’s Palace, on the southern outskirts of Cassino, the railway crossing of the Gari, the railway station and hummock and the country to the south. During the advance to this second objective, jockey, 5 Indian Brigade would be exploiting step for step along the eastern slopes of Montecassino and turning uphill to capture Hangman’s Hill (Point 435),26 a knoll just below the

south-eastern crest of the feature. At the same time 7 Indian Brigade was to keep up pressure from the north on the defenders of the monastery ruins. All this, it was hoped, would be accomplished by dusk on D-day.

That night the New Zealand engineers, with American assistance, would bridge the rivers on both the road and railway routes and clear a way through Cassino. The tanks of Task Force B, with 21 New Zealand Battalion under command, would move into the bridgehead ready to exploit and 5 New Zealand Brigade would close up to the river to assume responsibility for the railway station area. The Indian assault on the monastery would be launched the same night, but whether or not it succeeded the exploitation into the Liri valley would open at first light. Task Force B would advance to the first bound, and then 4 New Zealand Armoured Brigade and Task Force A would make the running.

The plan of exploitation was essentially the same as for avenger, but with two additions. The first was to define the role of 78 Division. On the night of D-day the division would build roads to selected crossings of the Rapido in the area of Sant’ Angelo and to the north. On the second night two battalions would cross the river, establish a bridgehead to cover the construction of bridges, and prepare to conform with the New Zealand Division by capturing the high ground west of Sant’ Angelo. The object was to help open a wide front as soon as possible to force the enemy to disperse his artillery effort. The second addition was made possible by the completion of Cavendish road. The armoured force under 7 Indian Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron was to debouch from Madras Circus at first light on the second day of the operation to assault the Albaneta Farm area and to finish off what it was hoped would be the rout of the defenders of Montecassino.

Artillery support was planned on a scale to eclipse all precedent in the history of the New Zealanders. The great variety of the weapons taking part and their occasionally obscure provenance confine us to round figures, but it may be said that during dickens nearly 900 guns would be available, if both direct and indirect support and both major and ancillary operations are counted. These included not only the commoner calibres of British and American field, medium and heavy artillery, but also American anti-aircraft and tank-destroyer guns and even three Italian 160-millimetre railway guns manned by Italians. General Freyberg calculated that in all a quarter of a million shells would be fired. These would weigh between three and four thousand tons.

The actual opening programme would employ more than 600 guns, firing nearly 1200 tons in four hours into the area of the attack. It fell into three parts. In the north the French Expeditionary Corps

would fire a diversionary programme. Beginning fifteen minutes before zero hour, the French would simulate an attack and fire smoke to screen German observation posts on the high ground from the sight of the New Zealanders forming up in Cassino. A counter-battery programme was to be fired by the French and 10 Corps as well as by New Zealand Corps. Every known hostile battery would be engaged when the attack went in, and harassing fire would continue during the afternoon. Finally, there was a programme of close support for 6 Brigade. From zero hour for 130 minutes a barrage by eighty-eight field and medium guns would precede the infantry through Cassino, while well over 200 guns fired concentrations on known enemy defences in the town and on the southern outskirts. The harassing of the southern and eastern slopes of Montecassino by sixty guns would complete the close-support programme.

If the enemy could be blasted into submission, this was the plan to do it. In seven hours and a half bomb-rack and gun-barrel would discharge upon Cassino four or five tons of high explosive for every German in the garrison. And 400 tanks waited to follow up. But all this sound and fury would signify nothing if the infantry failed to win their way through the town, and their difficulties were fully acknowledged. There was the risk that the Germans would reoccupy the northern edge of the town vacated before the bombing. Both the Indians working along the hillside and the New Zealanders in the town had dangerously narrow entries that would prevent them from appearing suddenly in great strength. The whole attack would be overlooked from the hills above Cassino and enfiladed by well-protected weapons on the slopes of those hills. The airmen had warned that the bombed ruins might impede tanks.27 Only the event would show.

(vi)

Though it was fine on the corps front, the weather forecast on 13 March was bad. On the 14th the indications had improved, and at 10.30 that night Fifth Army confirmed that the operation would begin next day. The long-awaited code-word BRADMAN was circulated through the corps. Those who affected sporting language speculated on the state of the wicket; and the historically minded noted that the morrow was the ides of March.