Chapter 13: The March Attack: Encounter

I: 17 March

(i)

THE sun that brought in a fine day on 17 March rose about 6.20 on a scene which, confused and uncertain as it was, gave the New Zealand Corps some encouragement and the Germans some concern; but when it set twelve hours later after a day of close and bitter fighting both hopes and fears were shown to have been exaggerated. Though the Indians reinforced their garrison on Hangman’s Hill and the New Zealanders made a thousand yards of good ground by pushing south to the railway station and the hummock, the German stronghold in the south-west of the town held out as doggedly as ever, and the eastern face of Montecassino remained to both sides a place of peril. The enemy survived a testing day. The 17th brought us fresh territorial gains, but to all intents and purposes it also defined their limits.

(ii)

Overnight the main actions had been fought on the hillside. Once more 5 Indian Brigade sent elements of two battalions up the slope. From Point 165 two companies of 1/6 Rajputana Rifles assaulted Point 236, the knob above the next hairpin bend in the road, and seized and held it against counter-attacks until about dawn, when, their ammunition spent, they had to fall back on their starting point. Point 165 itself now changed hands but the Indians won it back and held it during the day in none too firm a grip. The two other companies of 1/6 Rajputana Rifles made good their objective, Point 202, and defended it under fire for the rest of the day. Their advance had been made beside three companies of 1/9 Gurkha Rifles, who were to press on to reinforce Lieutenant Drinkhall’s all-but-beleaguered company on Hangman’s Hill. It took the Gurkhas eight hours or more to weave through the enemy defences. They arrived not a minute too soon. Their comrades on Point 435 were hard pressed: the Germans had counter-attacked, gained a foothold on the knoll and had been barely kept at bay by the

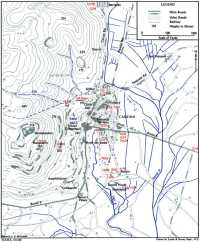

Operation DICKENS, position on night 17–18 March 1944

courage of Lieutenant Drinkhall, who, with one leg broken, had propped himself against a rock, fired his pistol at the enemy and inspired his men to hold on. They did, and when the three companies reached them the Germans were put to flight. Still closely hemmed in, the battalion threw a small circle of posts round its position and prepared for a feat of endurance. Drinkhall insisted on retaining command of his company and he did not abandon it until he was evacuated the next day. His bravery, skill and leadership earned him the DSO.*

On the morning of the 17th, then, Point 435 was securely garrisoned by 1/9 Gurkha Rifles, and below them Point 202 was in the hands of two companies of 1/6 Rajputana Rifles. There was only shaky contact between these two posts, and with the troops below them none at all. The rest of 1/6 Rajputana Rifles clung precariously to Point 165, which was besieged by enemy posts, but on Castle Hill 1/4 Essex were more comfortable though still troubled by fire from above and below. At Point 236 the enemy not only interposed himself between the Gurkhas and their base but dominated Castle Hill and Point 165, held at least a prohibitive command over the road to the monastery and swept with his fire wide areas of the hillside. So long as this situation was not mended the abbey looked safe from any threat based on Point 435, and the garrison there was like an arrow without a bow. But since a reliable route upwards from Castle Hill could not be established while Cassino was uncleared, the New Zealand infantry came under an urgent incentive to finish the job in the town. Freyberg pressed Parkinson to ‘put great energy into clearing it up on a broad front’. ‘It is essential that we should push through to the Gurkhas tonight,’ he added. ‘Anywhere you can push in tanks, do so’.

(iii)

These instructions were given about 8.30 a.m. By this time 6 Brigade was well launched on the day’s work. During the night the troops in the town had got themselves into better shape. Twenty-sixth Battalion, for example, had set up a Regimental Aid Post, received food and replenished its ammunition. The day’s programme began with an effort by 25 Battalion, with B Company 24 Battalion under command and 5 Troop 19 Armoured Regiment in support, to crush the stubborn opposition at the south-west corner of QUISLING. The attackers moved west at 6.45, preceded by the fire of tank guns and covered by small arms. The tanks, under Second-Lieutenant P. G. Brown,1 led off towards the Botanical Gardens, using their

* In the original 1957 publication it was stated that Lieutenant M. R. Drinkhall, 1/9 Gurkha Rifles, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his ‘bravery, skill and leadership’ throughout the battle for Hangman's Hill at Cassino. Lieutenant Drinkhall was in fact recommended for a VC but received the DSO. Unfortunately the award finally granted was omitted from the copy of the citation on the War History Branch file.

75-millimetre guns and Brownings at point-blank range against dugouts and emplacements to blast a path for the infantry. Visibility was poor and resistance strong, and three tanks were stopped by mud or broken tracks; yet stationary or mobile, their fire began to tell. The infantry fought their way forward under heavy shelling and in some confusion, 25 Battalion probably along the line of the northern Route 6 and B Company 24 Battalion across the gardens. On the right the advance was halted by Spandau nests manned by Germans who had sifted back into the town and dug themselves in under Castle Hill. On the left the 24 Battalion company, much under strength, came under tornadoes of fire from all quarters, but especially from the Continental Hotel, the very penetralia of the German defences, which stood at the T-junction where Route 6 turned south and commanded three stretches of road. The New Zealanders worked forward across the gardens, clearing buildings as they went, to within two hundred yards of the Continental. Here they took refuge in a house south of Route 6 and near its junction with a sunken road that ran towards the station. Four hundred yards ahead of them, as far as the foot of the hill, lay an uninviting arena – a stretch of ground bomb-torn, waterlogged, denuded of cover.

A pause ensued. But the attack had forced open the door far enough to allow 26 Battalion to pass through towards the second objective. Before 9 a.m. Bonifant reported that he now had enough room to work on both fronts at once. Freyberg, who had already that day withstood Clark’s pressure for more infantry, had words of exhortation: ‘Push on, you must go hard. Task Force B must go through as soon as possible. The limit is the roof – push hard’. Five minutes later he confided to Clark his hopes of ‘a certain amount of movement’.

(iv)

The launching of the southward thrust was a rough and ragged affair. The failure of communications kept the companies of 26 Battalion in ignorance of details of timings and routes, and they were in part engrossed in supporting 25 Battalion on their right. On brigade orders the artillery concentration opened at 11 a.m., and ten minutes later 4 Troop (Lieutenant Furness)2 led tanks of A Squadron out of the crypt of the convent and headed for the station, followed by 2 Troop (Lieutenant Beswick).3 The infantry, however, were not all aware that the advance had begun. Lieutenant-Colonel

Richards and his adjutant (Major Barnett)4 came up in a tank to spread the word and despatched C Company (Major Williams) on its way. Runners were sent to summon the other companies from the centre of the town.

Their forming up on some sort of start line was a frantic and bloody manoeuvre. They had to rush distances of a hundred or two hundred yards under the muzzles of German rifles and spandaus to reach Tactical Headquarters in the convent and the road to the station. The later platoons had to cross ground where they had seen their comrades struck down. Some slipped through almost unharmed by swinging left to shelter behind the stumps of buildings. Others, those of D Company, chose less wisely in veering to the right into full view of the waiting enemy and reached the convent in utter disorder. About twenty-five soldiers of A Company, including Major Fraser,5 failed to get there at all. One who did described his ordeal.

... those in the Municipal Buildings knew that their chances of gaining Tactical Headquarters were slim. Not only did the enemy have a sniper watching the only entrance to the building but the ground which the whole company would have to cross was under heavy fire. Enemy snipers and machine gunners had a clear view of the route and each man in the company knew what to expect when he started running. ... Nevertheless, section by section the men raced over the open ground. Most of them had only little more than a hundred yards to go, but the enemy snipers on roof tops were waiting and they showed no mercy. Most of those in the building got out safely only to be shot in the back as they ran toward the Nunnery [Convent] entrance. One after another they dropped. The wounded crawled to shell craters, others paused to help, only to be hit themselves. Other wounded stumbled, half-crawled towards shelter only to be laid low by another bullet. ... The wounded were lying everywhere. Mortar bombs were bursting amongst them. Those who reached the temporary haven of the Nunnery were badly shaken.

For twenty minutes Major Borrie,6 24 Battalion’s medical officer, assisted by Lieutenant Neale7 and Sergeant Maze8 of B Company, worked in the open to succour the wounded till mortar bombs at last drove them to cover.

Within the roofless, barn-like crypt bands of dazed soldiers who had raced to safety began to collect. They threw themselves down in exhaustion or stood doubled up, panting for breath; they swallowed tots of rum and dressed one another’s wounds. Those fit to go on gathered themselves into military order for the thousand-yard

advance to the station, while officers went round calling for volunteers to fill empty places of command.

Meanwhile the attack had gone forward. Between Route 6 and the railway line lay two roads forming a St. Andrew’s cross. In spite of an earlier reconnaissance, Lieutenant Furness could now rediscover neither of the two northern arms of the cross, so deep lay the rubble. By exploring on foot, he found a way round the blockage and led his tanks south under fire, with machine-gun bullets ‘rattling like hailstones’ on their steel walls. About the crossroads half-way to the station a belt of mines caused a hold-up. Furness himself and Corporal Forbes9 cleared the field while the other tanks covered them with the smoke of shells aimed into nearby piles of debris. Gaining the embanked road which formed the south-east arm of the cross, the tanks brought their guns to bear convincingly on pillboxes and machine-gun posts and all was going well until in quick succession two tanks of 2 Troop were set aflame by an enemy anti-tank gun. The crews made the most of their involuntary infantry role by wading through water waist-deep to capture a house from which machine-gun and mortar fire had been troubling them. From this building and another enemy post they combed out about sixteen prisoners. The tanks of 4 Troop pressed on towards the station and by noon two tanks were there ready to usher in the infantry. Within an hour they were joined by two tanks of 3 Troop (Lieutenant Griggs),10 the survivors of an adventurous journey from the Bailey bridge over Route 6.

The infantry made their ground much more slowly and arrived at the station not in a single sweep but in driblets, scrambling home like weary runners at the end of a long and deadly steeplechase. At the crossroads C Company, being in the lead, momentarily caught up with the tanks. Thereafter even the semblance of cohesion was lost. From the house near the crossroads where the dismounted tank crews had taken shelter the C Company platoons, already thinned out by shelling and mortaring, made their several ways towards the station. Some sections found a safe passage through a long, wet tunnel running beside a road, and then emerged on to the embankment to face bursting shells and a spray of machine-gun bullets. Some crossed the embankment and worked in an arc across the flat to the west. Others went farther west still to seek the protection of the sunken road. Eventually, perhaps by 1 p.m., the leading platoons were reunited near the station. They learned from the two tank

crews that the station was ours, though the area of the yards was not quite clear of the enemy.

When Major Williams arrived he found that his company had dwindled to about forty men, but he decided to seize the propitious moment and to order the capture of the hummock. This rocky hillock lay 200 yards farther on. To reach it the Round House had first to be taken. It fell without much trouble to Lieutenant Quartermain’s11 14 Platoon, which found it empty; but when 13 Platoon passed through to the final goal, opposition started up until Lieutenant Hay12 silenced two posts. He then led his men on to capture the hummock which had defied the Maoris a month earlier, along with six prisoners. The eastern slope was occupied and a post was sited on the forward slope to look across the flooded Gari towards the Baron’s Palace and the Colosseum, the origin of so much of the fire that had challenged the advance to the station area and now continued to harass its captors.

The progress of the other companies towards the station was similarly checkered by mishaps and loss and redeemed by the initiative of junior commanders and the doggedness of those who followed them. A few episodes are recorded, and they must do duty for all. Behind C Company came the remnants of A. Second-Lieutenant Lowry,13 who had taken over command, followed the tunnel route with fatal consequences, for by now the enemy was covering the exit with machine guns. Sergeant O’Reilly,14 at the head of two platoons, moved out across the mudflats over ground creased with deep ditches full of muddy water and bespattered with smoke canisters. He searched boldly for C Company and, brushing aside resistance, led the fourteen men still with him to the Round House and thence to the hummock. B Company (Major Harvey)15 made its wav to the station along with the survivors of D Company, now reduced to about platoon strength. They found the embanked road still raked by machine guns and infested by riflemen and when they plunged off it on to the flat the going, in knee-deep water, was slower and only a little less exposed.

On arriving at the station, Major Harvey conferred with Major Williams. The battalion was now too tired and too depleted to expand its gains to the limits of objective JOCKEY, and the decision was to consolidate on a line behind the Gari and its inundations, extending

as far north as possible. The two tanks retired a short way to a supporting position from which their guns could at once defend the station and hummock area and annoy more distant enemy posts. Meanwhile the answering fire from the Baron’s Palace did not slacken. The left flank rested firmly enough on a plain that was thickly mined and under the protective machine guns of 27 Battalion across the Rapido as well as being dominated by the three platoons holding the hummock. The rest of C Company defended the Round House and B Company disposed its platoons north of the station so as to cover it and Route 6 in the region of the Baron’s Palace. The remnants of A and D Companies went into reserve around the built-up road. Behind B Company the machine-gun section trained its guns along the railway line to the south-west, using blankets to conceal the flash.

By dusk the New Zealand infantry in the station area numbered about a hundred, and a few stragglers were still drifting in. Not all those missing were casualties – some were badly shaken and had turned back, some had stopped to tend the wounded, some were lying low until dark. But when the cost came to be counted, the battalion’s casualties during the afternoon were found to be 33 killed and 58 wounded.

(v)

The capture of the railway station and hummock was to have been the cue for 24 Battalion (less B Company) to essay the even more ambitious task of rolling up the vital stretch of Route 6 at the foot of the hill between the Continental and the Colosseum. Its failure might have been forecast from the day’s reverses in the town. At 9 a.m. Freyberg had canvassed the idea of sending tanks to work both ways from the T-junction of Route 6, south towards the Colosseum and north towards the centre of the town. In the event the infantry in Cassino spent the day gallantly but vainly battering themselves against the granite defences in the western fringes of the town and along the foot of the mountain, 25 Battalion under Castle Hill, B Company 24 Battalion at the approaches to the Continental. Consequently, when in the early afternoon 24 Battalion received the order to advance from the quarry area north of the town, the direct route to its objective was a fiercely contested battlefield.

A and D Companies, leaving C Company beyond the barracks, found Cassino, which they now entered for the first time, a perplexing and dangerous shambles. A Company (Captain Schofield) was pressed out to its left by hostility under the hill, but the pace could not be quickened and it was after nightfall when the company reached the convent. By now it was out of touch with D Company

(Captain Ramsay). The centre of the town had proved too much for Ramsay’s men also. After being shot at by well-hidden riflemen in a narrow defile where the use of smoke was not feasible, the company probed for another route but in the end pulled back to the northern entrance to the town and thence set out in the dark for the convent by way of the eastern outskirts, arriving about 8.30 p.m. Shortly after nine o’clock A Company made contact with B Company. Major Turnbull’s account of his company’s repeated repulses by ‘the heaviest fire I’ve ever seen’ and his insistence on the need for an adequately prepared attack with armoured support persuaded Schofield to turn back from his objective. D Company likewise paused for the night south of the convent. Thus the two companies inserted themselves between 26 Battalion in the south and 25 Battalion in the centre of the town; but the plugging of this hole seemed to have been a result of accident rather than design. Twenty-fourth Battalion’s coming made no real impact on the battle.

By night the roading programme went ahead smoothly on the outskirts of Cassino, but within the town, as always, successes were slight and hard-won. The northern approach along Pasquale road was repaired and the ford over the Rapido opened, but enemy fire forbade work on the eastern boundary road and so prevented the junction with Route 6. The Americans almost completed an alternative bridge over the Rapido on Route 6, but farther west in the town the New Zealand engineers with mechanical equipment could clear a route only as far as the Botanical Gardens, so that between an aggressive tank and its most desirable target – the Continental Hotel – three hundred yards of impenetrable wreckage still intervened. Though pitted with craters, barred by demolitions and liberally mined, the railway route was easier to work. By the morning of the 18th it was open to tanks and jeeps up to the station and to all traffic nearly as far.

(vi)

At dusk on the 17th the situation of the New Zealand Corps was ominous but not yet hopeless. It had profited from this day of opportunity, when the enemy resistance was at its lowest ebb, to advance as far as the hummock in the south – a success which gave more room for applying its superior numbers, stretched the German defences and widened the range of tactical choice. The air was almost entirely ours for observation or attack (over 400 sorties were flown this day) and the Germans had good grounds for their complaints about the consequences for their artillery, nebelwerfers and supply routes. The expenditure of our artillery remained vast. From dawn to dusk smoke was being fired or otherwise generated.

Three battalions of infantry were fighting in the town with the support of a regiment of tanks, three more on the hillside. But no irreparable damage had been done to the enemy.

By the test of original expectations, the work of a few hours was still incomplete after more than two days. On the slope of Montecassino, where there were two battalion groups rather than three battalions, the garrison of Point 435 was poised precariously at the end of a limb which the Germans milling round Castle Hill were already threatening to sever at the trunk. Below them neither of the first two objectives was wholly in New Zealand hands. Thanks to the tenacious defence of the western edges of the town, quisling was only partly taken. Whereas the line of jockey was a semi-circle swinging south from the Baron’s Palace and then north to the station, no bridgehead had been established there and indeed not a single New Zealander stood west of the Gari.

Judged even by that morning’s plans, the day’s operations had failed: it had not proved possible to ‘mop up the village’ and clear the zigzag road as far as Hangman’s Hill to relieve the Gurkhas. Communications were undependable. Enemy shelling seemed to have increased. Casualties in men and material were mounting. The Indians were finding the slopes above the town very expensive to hold and on the 17th the New Zealanders lost about 130 all ranks in killed and wounded. Of the fifty or so tanks in the town, the German claim to have destroyed thirteen was exaggerated. At least twelve, it is true, were unserviceable, but the great majority were capable of repair or merely needed to be released from the grip of mud or rubble.

In the conduct of the battle two problems in particular exercised the generals and provoked brisk exchanges of opinion between Freyberg and the commanders above and below him. The first was whether the time had come to commit fresh infantry in Cassino. Early in the morning Freyberg contemplated the alternatives of reconstituting 5 Brigade to occupy the station and help in clearing Cassino and the calling in of a brigade of 78 Division. Since 5 Brigade was being held for the pursuit, the first course implied some weakening of the intention or hope of exploiting up the Liri valley, and this Freyberg was yet unwilling to admit. Nor, for similar reasons, did he like the second course. His decision not to reinforce 6 Brigade in the town was fully in accordance with the views of Parkinson and Bonifant, but both Clark and Galloway dissented.

A second disagreement concerned the timing of the assault on the monastery. Clark pressed strongly and repeatedly to close the pincers as soon as possible, with an assault on the monastery from Point 435

to be accompanied or closely followed by a tank-supported advance from the hills to the north and north-west. Freyberg doubted whether the armoured right hook would achieve much until the monastery could be powerfully attacked from the south and east. As with the Anzio landing (‘nobody knows this better than you’), the diversion would succeed only when the main front had begun to crumble. To spring the trap too soon would only be to sacrifice surprise; and the monastery could not be attacked frontally, as Galloway insisted, until the supply route to Point 435 was secure. It was Galloway’s reiterated conviction that it would not be secure until Cassino was clear. Hence Freyberg’s pressure on 6 Brigade. This, like so many Cassino arguments, came round in a circle. The two controverted problems were one and indivisible.

(vii)

At 14 Panzer Corps headquarters an early alarm gave way during the 17th to rising confidence. In the early stages of the battle news had come in slowly owing to shattered communications, and when the intelligence map was brought more nearly up to date on the morning of the 17th the sight was found disconcerting. Reports of an orderly officer who had returned to 1 Parachute Division headquarters showed the Allied gains to be more extensive than at first thought, even though they were still short of the truth and were nearly all post-dated. At 10 a.m. Tenth Army confessed to Army Group C that ‘things are not too splendid here’, expressed anxiety lest the attack should be covering another operation elsewhere, perhaps along the coast, and rested the outcome of the battle on the day’s events. The disposition at corps and division was to estimate the threat along the railway line more seriously than that on the hillside, where shellfire would prevent the Allies from forming up in any strength, and the assault on the railway station was correctly forecast. The Germans recognised that the Allied possession of the station and Point 435 exposed them to the danger of an outflanking movement, but when the station fell later in the day they took reassurance from their continued occupation of the western parts of the town and the monastery ruins. Their reports say that paratroops abandoned nothing but heaps of ruins in the town; and the station is said to have yielded only after hand-to-hand fighting, of which the New Zealand records afford no corroboration.

By night-time, Heidrich, always in the thick of the fight, was cheerful enough to be quite vexed not to have scored a decisive victory, but to console him he had the Fuehrer’s personal approbation and – a more substantial comforter – reinforcements. In the town losses had been critically heavy. One company had sunk to a fighting

strength of eight men; 1 Parachute Regiment was in a bad way. Corps therefore placed two further battalions of 115 Panzer Grenadier Regiment at the disposal of the division on the understanding that they should relieve paratroops in the quieter neighbouring sectors. The paratroops hoped to share the honours of Cassino with none.

II: 18 March

(i)

The clearing of Cassino continued to engross the New Zealand Corps on 18 March, another day of fine weather. The Indians on the hillside, supplied overnight after more than one setback, could do little but hang on. The New Zealanders held their ground round the station, but the defence retained the upper hand also in the western fringes of the town, where the Germans threw back assaults from east and west. While the enemy infiltrated back into the town, the view still prevailed at New Zealand Corps, though with mounting doubt, that the three battalions already committed were equal to their task. They fought hard through the day without reinforcement but at the end had little to show for their efforts. By then a fourth battalion was on its way forward, the forerunner of a fresh brigade.

The tactics of the enemy and of our own troops on the 18th may be briefly compared before their almost uniform failure is described. The Germans had sufficiently regained their aplomb to be feeling their way towards a general counter-attack. They had planned for the night of 17–18 March to recapture the three points of a triangle which all but enclosed the battlefield – Point 193, Point 435 and the railway station area. As it happened, the first two attacks had to be abandoned, and the third failed; but the design was significant. If Castle Hill could be retaken, the danger to the monastery from Hangman’s Hill would wilt away of its own accord. Further, a base would exist from which to drive the New Zealanders out of the town. The railway station was to be seized for the same purpose. Besides, so long as it was in New Zealand hands the fear of being bypassed in Cassino would persist.

The New Zealand Corps plan was in essence the converse of this reasoning. It may be likened to an attempt to close a door with its hinge in the north-west corner of Cassino, its handle at the hummock and its jamb at Hangman’s Hill. If the door could be closed Cassino and the hillside would be sealed against infiltration, and the assault on the monastery from Hangman’s Hill could be mounted with a weight befitting its importance and conjointly with

the armoured hook over the hills. On the 18th the three battalions pressing against the door in order from the right were the 25th, the 24th and the 26th. Most force was being exerted near the hinge, and we might picture C Company 24 Battalion as sallying out in front of the door to remove, from the area of the Hotel Continental, an obdurate wedge that was keeping it open.

(ii)

Twenty-fifth Battalion was once more instructed to root out the enemy who had established themselves in two blocks of about six houses each at the foot of Castle Hill. These Germans were in a narrow salient from which they directed their fire into the centre of the town and, even more seriously, up the hillside. They succeeded in restricting the deployment of troops on Monastery Hill to the single channel of a well-registered postern in the castle, through which only one man at a time could pass. C Company laboured all the day and into the night to reduce the resistance. From their eyrie on Hangman’s Hill, where they were themselves the cynosure of New Zealand eyes, the Gurkhas looked down on the stubborn work in the town. Their commander, Major Nangle, wrote:

We watched, in one interval in the smoke, the New Zealanders below clearing one of the streets of Cassino. From our detached viewpoint we could appreciate the subtleties of the technique of both sides. The careful approach of the tanks, the searching for them by the German mediums, the blasting of each house in turn, the withdrawal of the Germans from house to house always covered by fire from another or from the street, the quick dashes of the supporting New Zealand infantry and the use of smoke by both sides.16

C Company’s perseverance was not unrewarded. At the last of three sorties from different directions, the company succeeded in clearing one troublesome strongpoint, killing 14 Germans and capturing three for the loss of 3 killed and 14 wounded. They were efficiently backed up by the fire of 19 Regiment tanks, mainly those of C Squadron, whose guns, it was claimed, completed the ruin of five or six houses. In such a scrimmage misadventure was not always avoidable: through bad marksmanship or ricochet some of the solid shot from the tank guns brought a wall in the castle tumbling down on some of the Essex battalion’s garrison and caused casualties.

Other companies of 25 Battalion nearer the centre of the town seem to have been less active, but they were subjected to the same merciless mortaring and small-arms fire as they reorganised and looked after their wounded. Though late that night Bonifant thought that the Germans were being worn down and that the town would be cleared next day, the fact was that the nuisance under Castle Hill was barely abated.

Farther south, 24 Battalion’s three companies were holding a line from the Botanical Gardens along the sunken road as far as the right wing of 26 Battalion. They faced, at a respectful distance, the Hotel Continental and its neighbouring bastion, the Hotel des Roses, 200 yards to the south. But B Company early lost two men shot from the rear by Germans who had presumably crept back during the night. Sniping from Monastery Hill made movement in the open suicidal. Nevertheless, having rested his men, Major Turnbull was planning another bid for the southward stretch of Route 6 when half his company were rudely disturbed by the collapse of the ceiling of the room where they were sheltering. By the time the men had dusted themselves, patched their wounds and disinterred their weapons, a dive-bombing raid had begun and it was then too late to attack. Such combined dangers and discomforts were the daily bread of the infantryman in Cassino, a ration more regular than any the quartermaster could send up.

Late on the 17th it was decided to vary the head-on assaults upon the defences at the foot of Montecassino by an attempt to come in by the back door while the Germans had their attention fixed towards the Rapido. The plan was for C Company 24 Battalion (Major Reynolds), still in reserve, to come forward through Castle Hill to Point 165 and thence to attack south to Point 202 to link up with the Rajputs who held that point. While 14 Platoon worked uphill to keep touch with the Gurkhas on Hangman’s Hill, the other two platoons from a firm base on Point 202 were to sweep down towards the town to clear the area between Point 202 and Route 6, with 13 Platoon on the right directed on the Hotel des Roses and 15 Platoon on the left on the Continental. Tanks in the town were to give the support of their guns.

Arriving at Point 165 on time at 5 a.m. on the 18th, the three platoons had to fight for a start line amid spandau bursts and in thick smoke, but the first stage of the attack went fairly well. A junction was made with the Indians on Point 202 and even with the Gurkhas on the ledge above. But the plunge towards the town failed. The open hillside, swept by machine guns dug in on the slope or mounted at crumbling casements on the edge of the town, craved wary walking. The two platoons’ lines of advance crossed: 15 Platoon found itself pinned to earth by fire from a pink house before it could close on the Hotel des Roses, and 13 Platoon could make as little headway. Two troops of A Squadron battered down some pillboxes, but they could not break the deadlock. Lieutenant Klaus17 succeeded in leading 13 Platoon as far as Route 6, only to be killed outside the Hotel des Roses.

Towards the end of the day the company, with six killed and five wounded, consolidated on the slope above the town in the rough area of Points 202 and 146. Major Reynolds was ordered to remain in place, partly to protect the flank of the Gurkhas on Point 435 and partly to interrupt as far as possible the flow of enemy supplies and reinforcements up Route 6. But the essential purpose of the action was unfulfilled. The paratroops were no more to be dislodged by the stiletto in the back than by the club in the face.

On the left flank of the Division, 26 Battalion beat off the strongest counter-attack yet attempted on the flat. For the men round the station a night made cheerless by shelling and the want of coats and blankets was succeeded by a cold, grey dawn, and with the dawn came the Germans. About sixty strong, they belonged to the motorcycle company attached to the Parachute Machine Gun Company. Their orders were to recapture the station and hummock and then to push north to the crossroads half-way to Route 6. Their coming was heralded by some ill-aimed artillery and nebelwerfer concentrations. Trying to pass themselves off as Indians, they approached across the mudflat and passed between the hummock and the Round House. Though some Germans managed to enter the Round House, the New Zealanders lying in wait opened such a fusillade, notably from the vantage-point of the hummock, that the attack was not pressed. The enemy withdrew under smoke, leaving behind at least ten casualties and perhaps more.

Their defensive success earned the men of 26 Battalion little respite. Sniping, mortars, artillery – the enemy employed the full repertory of harassment against them all day. To make life still less pleasant, our own 25-pounder smoke shells ‘were hissing overhead and bursting above [the battalion] area with a sharp crack [and] sending their canisters humming down to bowl madly all over the place’, while bombs dropped by the Luftwaffe burst in the flooded fields in front of the battalion and showered the men in their dugouts. That night there were more welcome visitors with greatcoats and blankets, and before midnight stretcher-bearers brought up a hot meal along the railway line. Since the ambulance jeeps used Route 6, casualties could be evacuated only by a difficult carry of half a mile or more to the convent.

By day the smoke screen was still an important charge on 5 Brigade, the Divisional Cavalry and the artillery. The supply of smoke shells was being consumed at an alarming rate. On this day alone 21,700 rounds were issued to regiments and stocks at Mignano were only saved from exhaustion by a timely journey to Nola by trucks of the Petrol Company. High-explosive shelling was supplemented as usual by aerial bombing, but the plight of the Indians

on Point 435 made an unusual call on the services of the fighter-bombers. Porterage on the mountainside was absorbing good troops, it was costly in casualties and it was unreliable in results. General Galloway was anxious to try the dropping of supplies by air, though it was realised that because of the steep slope some were sure to fall wide. During the afternoon forty-eight aircraft, each carrying two containers, made the delivery. Guided by coloured smoke, they came in slickly at about 200 feet. Suddenly the air blossomed into parachutes of many colours. Some of the canisters bounced out of reach down the hill, but the men on Point 435 retrieved enough food, water and ammunition to survive by hard living and to defend themselves.

(iii)

The Germans’ story of the 18th had a ring of confidence:

The enemy’s fierce assaults continued all day, but the paratroops held firm and kept command of all their positions. The town’s battle commandant, Captain Foltin, distinguished himself particularly ... by personal gallantry and sound leadership. The ... artillery again played a great part in the success of the defence, bringing perceptible relief to the hard-pressed infantry with destructive concentrations on the enemy’s forming up places.

Fresh reserves were brought up to strengthen the very weak garrison of the town.

Now that the day of crisis had been overcome, General Heidrich was full of confidence for the future.

The Germans were congratulating themselves on having survived the 17th when, without reserves, the handful of troops in Cassino had held off ‘a vastly superior enemy force’. Now the garrison had restored a continuous defensive line and was firmly under control. From the observed approach of Allied reinforcements the enemy concluded that the attack was losing its dash. The validity of this deduction may be tested against the tactical thinking in New Zealand Corps.

(iv)

On this disappointing day the debate on the sufficiency of the infantry in Cassino continued. Having seen the New Zealanders in the town, General Galloway again suggested that their difficulties were due to shortage of men. General Freyberg seemed now inclined to agree. He thought first of committing another battalion; by 7.30 he had almost made up his mind to put in 5 Brigade; but when an hour later General Parkinson repeated that he had enough troops, Freyberg deferred, rather dubiously, to his Divisional Commander. ‘You must remember,’ he said, ‘that the whole operation is being paralysed until Cassino is cleared up’. The slow progress

in the west of the town was the final argument. At 4.15 p.m. the decision was taken to commit 28 Battalion to mop up the rest of the town. The Maoris, under command of 6 Brigade and with the support of 25 Battalion, were to attack at 3 a.m. the next morning to capture the Continental and the buildings at the base of Castle Hill, including a towered watch-house which had been conspicuously troublesome.

Meanwhile plans had been laid for the capture of the monastery itself by a concerted assault. The unfinished state of the battle, whether in the town or on the hillside, was not allowed to act as a deterrent. The Maoris, it was hoped, would have snuffed out the last flame of resistance in the town before dawn. The Indians on Hangman’s Hill were considered to be fit to deliver the final stroke against the monastery, both because of the partial success of the supply missions by foot overnight and by air that afternoon and because 5 Indian Brigade had been able to reorganise – 4/6 Rajputana Rifles, having been relieved of their portering duties, had been amalgamated with 1/6 Rajputana Rifles to form a battalion of full strength. While the Maoris distracted or dislodged the Germans under Point 193, the Essex battalion was to climb the hillside to join 1/9 Gurkha Rifles on Point 435, and together at dawn the two battalions were to storm the monastery. At the same time 7 Indian Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron, reinforced by New Zealand tanks, was to make its diversion in the rear. The corps was doing its best to hasten the battle to a climax. Who held the monastery, it had always been thought, held the road to Rome. If the great prize could be seized on the 19th, the fifth day of the battle, the chase might still be possible. Three hundred and fifty clean tanks and two fresh New Zealand battalions were ready to exploit.

III: 19 March

(i)

The promise of the 19th withered early. First, the Germans in the west of Cassino refused to leave, even at the urging of the fresh Maori Battalion. Next, they turned to throttle the attack on the monastery before it could fairly begin by striking at the Indians’ vulnerable lifeline to Hangman’s Hill. Finally, the tanks which surprised the monastery garrison by appearing over the north-western hills, being left unaided, ended in discomfiture a sortie that deserved a better fate. Before the full tale of the day’s misfortunes could be told the Corps Commander had resolved on a reorganisation that marked the half-way point in the battle because it assigned to the conquest of Cassino infantry who had been destined to exploit far beyond.

(ii)

At three o’clock on the morning of the 19th 25 Battalion renewed the onslaught against the enemy ensconced beneath Castle Hill. A and B Companies at once ran into a tempest of mortar fire, for which our shelling of known positions was a retaliation rather than a remedy. Still, while the darkness lasted almost satisfactory progress was made, but when daylight came the advance flagged and soon ceased. The total achievement was a little ground gained, a ‘tidying up’ of our positions and a slightly clearer picture of the enemy’s defensive scheme.

On the left, C and D Companies of 28 Battalion (Captains Reedy18 and Matehaere), the only Maori companies sent forward, advanced between the two arms of Route 6 towards the Continental area. The Maoris were in good heart and though the battle raged fiercely and D Company, in the lead, had fourteen casualties, including their commander, they began to make inroads into the defences. The Germans fought from entrenchments under the hill along Route 6 and its northern extension, with the efficient support of two tanks hull-down in or about the hotel ruins. The enemy infantry were for the most part invisible, but the muzzles of their weapons protruded through slits and crannies made by the fall of slabs of masonry, bricks and beams of steel and wood. The tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment could approach no nearer than two or three hundred yards for rubble and craters, but from that distance they could do some execution and before nightfall they claimed the destruction of the two enemy tanks. A few men of D Company actually reached the foot of Monastery Hill, only to find that they had outrun their fellows and that they were surrounded. In the afternoon the Maoris went to work clearing the area north of the Continental, and from a building farther south they took a good haul of prisoners, prodding their first captives in the ribs and persuading them to call on their comrades to surrender. These successes were won against the enemy’s outworks only. The main centres of resistance could not be reduced, and indeed it was guessed that under cover of darkness and the distractions of mortar and shell they were reinforced that night to their original strength.

Between Route 6 and the station 24 Battalion’s three companies had a passive role until about an hour after dusk, when D Company repelled the first of several counter-attacks that disturbed the night of 19–20 March on that part of the front. Intended to regain ground and not merely as raids, these forays seem to have been made in no great strength and all were beaten off without serious trouble, though not without casualties.

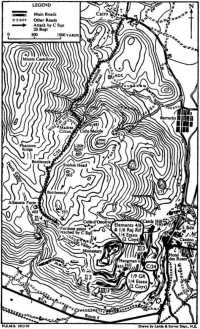

Operation REVENGE, 19 March

Both 26 Battalion round the station and C Company 24 Battalion on the hillside occupied areas whose tactical importance invited enemy fire, and both spent most of the 19th with their heads down. The: 24 Battalion men had better opportunities to retaliate – for example, on Point 165 and the yellow house near it, which was a nest of troublemakers – but by compensation they had to suffer from our own loosely aimed shells and from flying smoke canisters, shell cases and base plugs, and only on the rare occasions when wireless communication was open did they shed the sense of isolation and ignorance. The patrol that set off down the hill that night to keep an appointment with the Maoris about Route 6 made no friendly meetings, and, overtaken by daybreak, had to shelter throughout the 20th close to the Hotel des Roses.

(iii)

Even before the ruins of the monastery showed dusty white again in the dawn of the 19th, the two claws of operation revenge were beginning to close upon them. To the north tanks were making the stiff ascent up Cavendish road from Cairo village; and above Cassino town two companies of the Essex battalion had started out from Castle Hill across the hillside to clear a way for the rest of the battalion to Hangman’s Hill, whence with the Gurkhas they would make their dash for the crest. About 5.30 as two Rajput companies were relieving the Englishmen at Point 165 and Point 193, the enemy broke in upon these preparations.

Announced by a sharp bout of gunfire and mortaring, a battalion of paratroops (I Battalion 4 Parachute Regiment) swept down from the summit of Montecassino, engulfed the defenders of the lower hairpin bend and pressed on to the castle. The garrison, numbering about 150, manned the battlements and fought back their assailants, first with their own arms and then with the help of the gunners, who dropped a barrier of shells between the castle and the enemy. Again and again the Germans came on. They had to be shot down as they tried to clamber up the walls. By 8 a.m. the first fury of the assault was dying down, but only three officers and sixty men remained on their feet in the castle. ‘Machine gunners had fired more than 8000 rounds and the Essex mortars more than 1500 bombs. Mortar barrels had grown red hot, had curled and bent’. At nine o’clock the attack was renewed from the east. The paratroops savagely machine-gunned the castle from the buildings on the fringe of the town, but when they mounted the slope the defensive fire was so deadly that they sued for a truce to pick up their wounded and for thirty minutes there was peace. During the afternoon an audacious party of Germans blew a charge under a buttress of the

northern rampart but as they swarmed through the breach they fell beneath a hail of bullets. This was the last crisis. Point 165 had been lost but the castle was held (though the German headquarters believed otherwise), and if a parachutist who gave himself up was telling the truth, only 40 of the 200 men in the first assault were still fit to fight.19

The Essex companies already on their way to Hangman’s Hill when the counter-attack began reached their goal about 10.15 a.m. Their journey of five hours, almost entirely by daylight, left them so weak, and the line of supply and reinforcement was now so insecure, that the attack on the monastery, planned to take place at 6 a.m., was postponed.

(iv)

But if the enemy had dashed the initiative from our hands in one place, he lost it in another. The tank thrust at the monastery from the rear, for which Cavendish road had been developed,20 was a stroke long meditated, and had originally been timed for the second day of the battle. The armour had been intended merely to complete the rout of an enemy already beaten by an infantry assault from the front. The circumstances of the 19th were much less favourable.

The armoured hook over the hills was to be delivered by a force under command of 7 Indian Brigade comprising seventeen Honey tanks of the brigade’s reconnaissance squadron and from 760 United States Tank Battalion, three 105-millimetre self-propelled guns from Combat Command ‘B’ and the Shermans of C Squadron 20 Armoured Regiment (Major Barton). A reconnaissance on the 18th stripped Barton of any illusions that the going might be easy; he was burdened with a difficult task of liaison with the Goums of the French Expeditionary Corps on Monte Cairo; his squadron was a small detail in a mixed force directed on to a somewhat vague objective under command of a British artillery colonel without tank experience; and he was so concerned at the total lack of infantry support that he made representations to Corps, but fruitlessly since the Indian brigade, steadily drained of men by weeks of fighting and exposure in the hills, could spare no infantry for the operation.

It was after 7 a.m. on the 19th when the force left its rendezvous at Madras Circus, west of Colle Maiola, and began to rattle along the track leading south-west to Albaneta Farm. At this time the outcome of the contretemps round Castle Hill was still obscure

but General Galloway did not despair of the infantry assault on the monastery. In fact, having hastened the two Essex companies on their way, he ordered the Gurkhas to attack as soon as they were ready. It was accepted that the planned sequence of the operation would be reversed, with the armoured jab preceding instead of following the onset of the infantry.

On the first stage of their filibuster it was the going that gave the tank commanders their chief worries. They found the trail itself negotiable, but elsewhere the ground was sometimes treacherously soft in spite of the recent fine weather or harsh and rocky. Consequently, some tanks were bogged and others lost their tracks. They passed through one defile without trouble but beyond a second, four or five hundred yards north of the stone farmhouse of Albaneta, opposition rapidly became warmer. The sudden apparition of tanks in this rugged country took the enemy off his balance and agitated wireless messages were overheard. But the men of 111 Battalion 4 Parachute Regiment rallied quickly. Lacking anti-tank guns, they called down reiterated salvoes from the artillery, threw in the vicious deterrent of mortar bombs and, above all, used their small arms with such accuracy and persistence from the cover of scrub and boulders that it was death for the tank commanders to show their heads for more than a moment above the turrets of their tanks. Thus, half-blinded, several tanks trundled into difficulties. Some stranded by mud or mechanical failure were later stalked by aggressive tank-hunters.

The Shermans meanwhile had burst through the thin defensive line and thrust a way between Albaneta Farm and the rock-strewn slopes of Point 593, pounding at the blockhouse with their guns. While other New Zealand tanks engaged the enemy infantry, Lieutenant Renall21 led his troop on round the southern shoulder of Point 593 towards the monastery ruins. The Liri valley was in full view on their right, and the leading crews won to a sight of their goal. The way to the monastery, they reported later, lay open over a good cobbled road, but they had no infantry to go with them. One by one they came to grief, hit or stuck in the mud; and when the lighter tanks intruded into the arena they drew a storm of fire on themselves. Solid shot and high-explosive shells were pumped into Albaneta house to set up a dust and under its cover two American Honey tanks raced in and rescued some of the crew of a wrecked Sherman. The gallant Renall was killed.

By now it was clear that the day’s dash was over. With only about five tanks still running, Major Barton was opposed to further efforts to reach the monastery. The commander of the reconnaissance

squadron, who could count losses as heavy, shared his opinion. Since no infantry would now be launched against the abbey, further diversion would serve no tactical purpose. The German infantry, sheltering behind sangars or in dugouts on the hillsides, were all but invulnerable to the tanks. When night fell they would take the upper hand. Indeed, the signs were that a counter-attack was already brewing in the Phantom Ridge area, which could seriously embarrass the withdrawal. Much earlier, about 1.30 p.m., Galloway had recognised that the thrust had reached its limit–the track forward, he thought, needed the attention of sappers – but it was late afternoon before the last of the tanks were recalled. Speeded by a parting demonstration by German bazookas, the armoured column limped back to laager behind the Indian FDLs at Madras Circus.

Losses had been appreciable. Of the New Zealand tanks alone nine or more were immobilised, and damaged radiators and bogeys made others unfit for battle. Casualties in C Squadron numbered two officers and three other ranks killed and one officer and about eight other ranks wounded. Most of these were inflicted by rifle and bazooka fire.

General Galloway made a just estimate of this enterprise when he said that it had been as successful as he could have expected. To get tanks behind Point 593, in the heart of the enemy’s mountain fastness, was a feat of uncommon skill and determination. Psychologically, it was a victory; materially, hardly so, even though it may have prevented the Germans from thinning out in that area to find reserves for the main battle.22 From the moment that the attack became a principal instead of a subsidiary operation, it was extravagant to hope that the armour would put the monastery defenders to rout; and if the tactical situation made the issue dubious, the going and the lack of infantry support put failure beyond all question. For it was the going rather than hostile fire that immobilised most of the tanks and together with the configuration of the ground enabled the Germans to defend themselves without tanks or anti-tank guns of their own and with few, if any, minefields. If the tanks had been escorted by infantry, the raid (for such it was) would have been less costly and more destructive, but it would still have been only a raid.23 By the time it was firmly decided to cancel the attack from Hangman’s Hill, the tanks had gone too far to be called back. But it was a pity to expend the surprise for such

a small result and, not for the first time at Cassino, to close one arm of a pincer on empty air.

(v)

The engineers’ day retraced the now familiar pattern – on the outskirts of the town a workmanlike job could be done, but inside the town it was impossible. In the morning and again in the evening fifty men from 5 Field Park Company tried to clear Route 6 behind the Maoris, but roadmending in the thick of the battle was shown on both occasions to be visionary. Reconnaissance alone cost two officers wounded. Improvements to the railway embankment and to the lateral road from Route 6 now gave two quite good routes to the railway station, and American engineers on the night of 19–20 March completed the alternative bridge over the main highway.

The artillery duel grew in intensity on the 19th. Besides firing in direct support of the troops in the town and on the slopes of Montecassino, the corps guns had recently played with increasing severity on the area around the Colosseum, whence tanks and mortars were believed to be harassing our infantry between the station and the hummock. The Colosseum area merited attention for other reasons: it would certainly act as a dyke to contain any attempt to flow round the cape into the Liri valley, it commanded Route 6 south of the Hotel des Roses and it would hold in enfilade any drive by our troops to cross this reach of road in order to link up with Points 202 and 435. Though still outgunned in the proportion of about three to one, the Germans were bringing up more batteries and it was estimated that they now disposed 9 heavy, 50 medium, 120 field and 60 88-millimetre pieces.

If their guns fired aggressively and with considerable immunity, it was not because of negligence by our counter-battery organisation, which was unusually alert and inventive. It was rather that the German guns enjoyed exceptional protection from the terrain and the layout of the battlefield. Three of the main enemy gun areas gave good flash cover – the valleys round Piedimonte San Germano, the valleys south of the Liri in the neighbourhood of San Giorgio and the northern hill country of Belmonte and Atina. The last two lay almost in prolongation of the line of Monte Trocchio, the New Zealand flash-spotters’ base, so that effective triangulation was impossible, and all three profited from the hill echoes which baffled our sound-rangers. Even when gun positions were accurately located, it was therefore not simple to detect which batteries were active at any given time. And even when the active batteries were correctly reported, they were by no means automatically silenced, because they were dug in on reverse slopes where

only a direct hit would do much harm. The fourth group of guns, on the flat of the Liri valley round Pignataro, were the most vulnerable. Though they seemed to be using flashless powder, they were constantly worried by our air OPs, and the crews had to get what comfort they could from dugouts. By keeping some guns laid on active positions, the corps counter-battery staff managed to bully the nebelwerfers in the Liri valley into a more respectful silence.

(vi)

The armoured hook once stopped, the enemy viewed the day’s events with composure, though not with complacency. Fourteenth Panzer Corps believed that the counter-attack on Point 193 had isolated Hangman’s Hill and that this pocket could be cleared out as a preliminary to tiring the enemy and pushing him out of the town step by step. But any general counter-attack, it was thought, would be madness. The New Zealand tanks were admitted to be ‘getting through the craters not badly’ and their fire was causing fairly heavy casualties. If the Germans had a real anxiety, it was less for Montecassino than for the area of the station – the sole worthy object of a weighty counter-stroke.

For some time General Freyberg had been inclined towards a strengthening and regrouping of his infantry in Cassino. News of the trouble at Point 193 turned an inclination into a decision. On reporting his setback General Galloway complained that the two battalions in the town were two battalions too few and flatly declared it to be ‘a glaring fact’ that his division could do little more until the town was cleared. It was agreed that the enemy was stronger in Cassino than had been thought. Some of the assaults on Point 193 had come in from the town side, and the New Zealanders were finding that houses cleared once were apt to be re-occupied by the enemy a few hours later. Though Colonel Hanson thought that there was ‘an underground Cassino’ and common speculation honeycombed the town with an elaborate system of tunnels,24 it had to be assumed that the Germans were filtering back by more orthodox means – in particular, by the southern stretch of Route 6 and by the steep gully that ran down from Point 445 to Point 193.

Freyberg therefore resolved on measures first to garrison the town against interlopers from the south and north-west and then to sweep it clean once and for all north of a line from the station to Point 435. To do this, recourse to 78 Division was unavoidable. The Indian Division, reinforced by 6 Battalion Royal West Kent

Regiment from 78 Division, was to establish itself firmly on Point 193 and recapture Point 165. The New Zealand Division was to regroup in greater strength on a narrower front. Fifth Brigade would come into the line in the northern section of the town, bringing with it 23 Battalion and assuming command of 25 and 28 Battalions and 19 Armoured Regiment (less C Squadron), while 78 Division closed up on the left to take over some of the Division’s responsibilities in the south. It would be the task of 5 Brigade to comb out the rest of the town and open up Route 6 to the south, so that the posts on Points 435 and 202 should be no longer isolated.

Having made these dispositions, the Corps Commander felt more cheerful, but he did not disguise his sense that time was running out. The Gurkhas and the New Zealanders below them on Point 202 could not hang on in mid-air for ever. In fact, henceforth their supplies and ammunition were dropped by aircraft.

(vii)

Lively enemy gunfire disturbed but did not dislocate the reorganisation on the night of 19–20 March. Among the New Zealanders in the town the relief occasioned much abstruse shuffling of places and there was some marching and counter-marching, but when the 20th dawned a picture of tolerable clarity emerged. The Royal West Kents had taken over Castle Hill, allowing the half-battalion of the Essex Regiment to go into reserve. East of Castle Hill in the northern part of the town 23 Battalion was holding the old FDLs of 25 Battalion, one company of which remained in the town on the northern flank, with the other three back in a rest area along Pasquale road or on the way there. The Maoris remained in position roughly between the two arms of Route 6, but to the south there were new dispositions. Twenty-fourth Battalion, reinforced by a company of the 23rd on the sunken road, continued the line, but it had sent one of its companies to reinforce 26 Battalion round the station. Finally, on the Division’s left flank, 23 Battalion’s sector had been occupied by the Divisional Cavalry, which in its turn had been relieved by two companies of 2 Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers from 78 Division’s 11 Brigade. The inter-divisional boundary now ran along the Ascensione stream from its junction with the Gari, across the railway as far as the 19 northing grid line on the map and thence due east to Route 6.