Chapter 1: The Battle for Rome

I: The Armies Regroup

(i)

THE New Zealand Corps, having failed in its attempt to capture Cassino, was disbanded on 26 March 1944, and in the seven-week pause that ensued, the Allied armies regrouped and assembled a striking force west of the Apennines in preparation for a fresh onslaught on the German Gustav Line.

The exhausted troops were rested, and vitally necessary reinforcements arrived and were absorbed. The front-line positions had to be held in sufficient strength to withstand a possible enemy counter-attack, and owing to the shortage of reserves, most units had to vacate one position and occupy another after only a brief spell out of the line. Also, because the enemy overlooked much of the front and its approaches, it was practically impossible to relieve a group larger than a battalion; in fact many reliefs had to be made at company or even platoon level. To ease the administration of the two armies, United States and American-equipped French formations were retained under the command of Fifth Army, and British-equipped formations (except those in the Allied beachhead at Anzio), including 2 Polish Corps, came under Eighth Army.

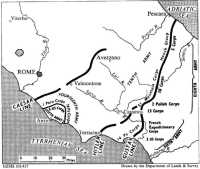

When the regrouping was completed Fifth Army had two corps in the line between the Tyrrhenian Sea and the confluence of the Liri and Gari rivers: the French Expeditionary Corps on the right with four divisions (1 Motorised, 2 Moroccan, 3 Algerian and 4 Moroccan Mountain Divisions) and about 12,000 goumiers (native Moroccans under French officers and NCOs, especially skilled in mountain warfare), 2 US Corps on the left with 85 and 88 US Infantry Divisions, and 36 US Infantry Division in army reserve. At the Anzio beachhead south of Rome 6 Corps, still under Fifth Army,

Dispositions, 11 May 1944

had six divisions (3, 34 and 45 US Infantry, 1 US Armoured, and 1 and 5 British Infantry Divisions) and 1 (Canadian and American) Special Service Force.

In Eighth Army’s sector, which extended from Fifth Army’s right boundary north-eastwards across the mountainous centre of the peninsula, the striking force was concentrated on the left, where 13 Corps held the line from the Liri River to Cassino with four divisions (6 British Armoured, 4 and 78 British Infantry, and 8 Indian Divisions); 1 Canadian Corps (1 Canadian Infantry and 5 Canadian Armoured Divisions) was in reserve in rear, ready when called upon to go into the line or pass through up the Liri valley; 2 Polish Corps (3 Carpathian and 5 Kresowa Divisions) was on the right, poised for the attack on Montecassino. The remainder of Eighth Army’s sector, astride the Apennines, was held by 10 Corps, which comprised 2 New Zealand Division (reinforced from time to time by British, Canadian and South African formations), and an Italian Motor Group about two brigades strong. The 6th South African Armoured Division, not all of which had arrived in Italy, was in Eighth Army reserve. On the Adriatic coast 5 Corps, consisting of 4 and 10 Indian Divisions, was under the direct command of Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy.

(ii)

At Anzio Mr Churchill ‘had hoped that we were hurling a wild cat on to the shore, but all we had got was a stranded while.’1 If the Allied amphibious attack had fallen short of fulfilling the Prime Minister’s hopes, at least it had placed Field Marshal Kesselring’s Army Group C in an awkward, extended, two-fronted position, with Tenth Army (Colonel-General Heinrich von Vietinghoff-Scheel) on the Winter Line across the peninsula and Fourteenth Army (Colonel-General Eberhard von Mackensen) around the beachhead perimeter in rear of the line. Tenth Army’s dispositions resembled those of the Allied armies: on the Adriatic sector Hauck Group (305 and 334 Infantry and 114 Light Divisions), like 5 Corps opposite it, had only a holding role; 51 Mountain Corps (5 Mountain, 1 Parachute and 44 Infantry Divisions) occupied the line across the Apennines to Cassino and the Liri River; 14 Panzer Corps (71 and 94 Infantry Divisions, with 15 Panzer Grenadier Division in reserve) was between the Liri and the Tyrrhenian Sea; 90 Panzer Grenadier Division, between Anzio and the Tiber River, was in army reserve. To contain 6 Corps at Anzio Fourteenth Army disposed 76 Panzer Corps (362 and 715 Infantry Divisions, with 26 Panzer Division in reserve) and 1 Parachute Corps (4 Parachute, 65 Infantry and 3 Panzer Grenadier Divisions – the last partly in the line); 29 Panzer Grenadier and 92 Infantry Divisions, beyond the Tiber, were in army reserve. The Hermann Goering Panzer Division, awaiting transport to France, was at Leghorn – but was later drawn into the Italian battle instead of leaving, as intended, for the western front.

To meet the apparent threat of another seaborne (or an airborne) landing the enemy had spread out his mobile formations well along the west coast. He may have been deceived by an Allied scheme, employing dummy wireless traffic, which was intended to give the impression that an amphibious assault was to be made against the port of Civitavecchia, 40 miles north of the mouth of the Tiber.

To back up the forward position of the Gustav Line the Germans constructed an even stronger alternative defence line, on which an attack might be held after the surrender of the intermediate ground. Known to the Allies as the Hitler Line,2 this was hinged on the main Winter Line at Monte Cairo, crossed the Liri valley about eight miles west of the Gari River, and continued through the

Aurunci Mountains to the coast at Terracina. The Gustav and Hitler lines were designed to block an Allied thrust up the Liri- Sacco valley, but because of the presence of the Allied force in their rear at Anzio, the Germans began to construct yet another defence line to delay the capture of Rome. This, the Caesar Line, was supposed to cross the peninsula from the west coast north of Anzio to the east coast north of Pescara, but was never completed; the most developed portion of it was in the vital area at Valmontone, where Route 6 passed through a gap between the Alban Hills and the Prenestini Mountains.

When the Allies struck at the Gustav Line on 11 May, Kesselring’s mobile reserves were too far away to give immediate help, and because he apparently still expected a seaborne attack, he committed them tardily and piecemeal. General Alexander, therefore, had the disparity in strength he desired, ‘a local superiority of at least three to one’, in the battle area: between Cassino and the sea four German divisions opposed an Allied strength of more than 13 divisions.

II: The Apennine Position

(i)

The transfer of the New Zealand Division from Cassino to the Apennine mountain position was accomplished by a complicated process of disentanglement and rearrangement which took some time. After the disbandment of New Zealand Corps on 26 March, 13 Corps took over the Cassino front with 4 British Division holding the Monte Cairo sector on the right, 78 British Division relieving 4 Indian Division in the centre, and the New Zealand Division on the left in the ruined town and extending its flank as far south as the boundary between Eighth and Fifth Armies, near the confluence of the Gari and Liri rivers.3 The New Zealanders’ sector thus stretched for about five and a half miles, with 6 Infantry Brigade holding the line through the town to a few hundred yards south of the railway station and 5 Infantry Brigade continuing it to the southern boundary.

As the weather improved the German observers on Montecassino enjoyed a clear view of the approaches and the positions in and around the town. All activity, therefore, was screened as much as possible with smoke, while the artillery, mortars, tanks and machine guns fired programmes to neutralise as many of the enemy’s posts as possible and reduce his interference with the reliefs. Despite

these precautions, the withdrawal of 5 and 6 Brigades was not accomplished without casualties.

To get the two New Zealand brigades out of the line, 1 Guards Brigade relieved 5 Brigade, which in turn relieved 6 Brigade; 2 Independent Parachute Brigade relieved the Guards Brigade, which then relieved 5 Brigade. On the night of 7–8 April, when the last of these reliefs was completed, the whole Cassino sector came under the command of 6 British Armoured Division, with the Guards Brigade on the right, the parachute brigade in the centre, and 4 NZ Armoured Brigade on the left.

Fifth Brigade (Brigadier Stewart4) went back down Route 6 to the Mignano locality and later to Isernia, in a peaceful valley east of the upper Volturno River; 6 Brigade (Brigadier Parkinson5 went to the Presenzano area, near the Volturno beyond Mignano. In pleasant surroundings, where the fresh spring growth in woods and fields was in such vivid contrast to the rubble, bomb craters, shattered tree-stumps, mud and water, and the perpetual smoke pall of the Cassino battlefield, the troops relaxed and trained while their units reorganised. Leave parties went to Naples, Bari, Pompeii and elsewhere, and those not on leave were entertained by concerts, films and mule derbies.

Fourth Armoured Brigade (Brigadier Inglis6), still at Cassino, came under the command of 6 British Armoured Division on 8 April, and its 22 (Motor) Battalion relieved 2 NZ Divisional Cavalry two nights later in the sector bordering the inter-army boundary, where the cavalry had been in an infantry role. On this section of the front the ground sloped towards the Gari River and was overlooked by a ridge on the far side. After several clashes with enemy patrols 22 Battalion gained control of the whole of its sector east of the river, and its enterprising patrols, swimming the swift-flowing water or crossing in a rubber boat guided by a rope, penetrated a quarter of a mile into enemy territory on the opposite bank

(where they saw equipment which had been abandoned during the Americans’ bloody repulse in January) and gathered information which would be of value when the Allies launched their final assault over the Gari.

Some of 4 Brigade’s Sherman tanks were retained in the Cassino sector in a defensive or counter-attack role. Eight or nine from 20 Armoured Regiment stayed in the town, three of them in the station area, with the Guards Brigade. Unlike those still east of the Rapido River, where they had better fields of fire and could move from place to place, the tanks in the town were immobile and could do little or no shooting; their cover was gradually whittled away by enemy fire, and smoke had to be used increasingly to screen them from view. This was a wretched and monotonous existence for their crews, who could get out to stretch their cramped limbs only at night.

South of Monte Trocchio, the isolated hill which gave observation over much of the front, 18 Armoured Regiment employed one of its squadrons at a time in an artillery role adopted because ammunition had to be husbanded for the 25-pounder field guns but was more than sufficient for the 75-millimetre tank guns. Among the variety of targets the tanks engaged from their indirect fire positions were enemy guns and buildings, including the front-line village of Sant’ Angelo on the ridge across the Gari River. The Germans’ retaliatory stonks7 damaged two tanks and killed five men and wounded others during the three weeks the regiment was employed on this task before handing over to 19 Armoured Regiment.

The 6th Armoured Division was relieved at Cassino by 8 Indian Division, and when 22 (Motor) Battalion had been replaced by 3/8 Punjab Regiment, 4 Armoured Brigade relinquished command of its sector to 19 Indian Infantry Brigade on 25 April, and withdrew to Pietramelara, 20-odd miles from the front. The relief of 20 Armoured Regiment’s tanks in Cassino by 12 Canadian Armoured Regiment was particularly difficult: one New Zealand tank broke a track on the way out and although ‘smoked’ all the ensuing day was too badly damaged by enemy fire to be of further use; another two tanks, which could not be extricated safely, were left in position for the Canadians.

(ii)

Meanwhile, on 15 April, 2 NZ Division assumed command of the southern sector of 10 Corps’ Apennine position, where the French had originally broken into the Gustav Line. This part of the

front covered the approaches through the mountains to the Volturno and Rapido valleys from Atina, a road junction in the Melfa River valley about 10 miles north of Cassino, but was overlooked from the west by the towering Monte Cairo and from the north by Monte Cifalco, Monte San Croce and other Apennine heights still held by the enemy. Already 6 NZ Infantry Brigade had relieved the Polish 6 Lwow Brigade astride the road at the top of the Rapido valley, on the more easterly of the two routes from Atina, and had come under the temporary command of 5 Kresowa Division.

On Easter Monday (10 April) 25 Battalion had left the Volturno valley near Venafro and motored up the winding road through steep-sided valleys and small villages to a debussing point near Cardito, where stores and equipment were loaded on mules with the assistance of Indian muleteers. Accompanied by Polish guides and troublesome mules, the companies set out on foot in the dark on a track alongside a tributary of the Volturno and after two or three miles began climbing very steep, narrow tracks – exhausting for the heavily laden men – on the northern side of the Cardito – San Biagio section of the road, where they relieved 14 Polish Battalion on the extreme right of the divisional sector. Following much the same procedure, 24 Battalion next night took over positions from 16 Polish Battalion south of the road and facing the 3500-foot Monte San Croce, and 26 Battalion, after being delayed by a thunderstorm, on the following night relieved 18 Polish Battalion on the lower slopes of San Croce and on Colle dell’ Arena, a plateau-like feature farther to the left. C Squadron of Divisional Cavalry and 33 Anti-Tank Battery, both under 6 Brigade’s command, were given infantry tasks to thicken up the defence; and the Vickers guns of two companies of 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion were sited where they could make best use of their long range and give enfilade fire in front of the infantry posts. Also in support were 5 Field Regiment, two batteries of the Royal Artillery, an anti-aircraft battery, and a company of engineers.

Sixth Brigade’s sector was a comparatively quiet one, but as 85 Mountain Rifle Regiment of 5 Division had excellent observation from Monte San Croce and the nearby high ground, it was hazardous to move in the open in daylight. The rugged terrain made a continuous line of defences impossible; wide gaps existed between the defended localities, which were protected by mines and wire entanglements, and between 6 Brigade and the Italian Motor Group in the next sector. Exchanges of fire were not very frequent, but pickets and patrols kept a vigilant watch to prevent enemy patrols from infiltrating through the gaps. The troops enjoyed the spring sunshine and the clear mountain air, the views down the

Rapido valley and across the intervening hills to Montecassino, visible in fine weather, but found the nights cold, especially in posts which gave little shelter. Occasional storms brought high winds, heavy rain, and snow on the ranges.

The central sector of 2 NZ Division’s line in the upper Rapido valley was held by 11 Canadian Infantry Brigade Group, and the Belvedere-Terelle sector, on the left, by 28 Infantry Brigade of 4 British Division. The Canadian group, 7500 strong, stayed on this part of the front from 9 April to 5 May, when it was relieved by 12 South African Motor Brigade. In addition to the three Canadian infantry battalions the group included a motor regiment of 5 Canadian Armoured Brigade, artillery and engineer units, and the Italian Bafile Battalion (composed mainly of 1000 sailors from the Italian Navy who had volunteered for land duty after surrendering their ship at Malta). The Canadians’ sector offered the best opportunity and had the most need of constant patrolling, and sometimes as many as a dozen patrols went out during one night. The Canadians’ most formidable problem, shared by all formations in the Apennines, was getting supplies to troops in isolated, rocky positions.

After just over a week in the line on the Canadians’ right, 6 NZ Infantry Brigade relinquished command of its sector on 20 April to 2 Independent Parachute Brigade (which had been replaced at Cassino by a brigade of 8 Indian Division) and went into divisional reserve in the upper Volturno valley not far from Montaquila. About the same time 5 NZ Infantry Brigade left Isernia to relieve 28 Infantry Brigade on the Canadians’ left.

(iii)

Probably no part of the front was more difficult to reach than the Belvedere-Terelle sector, hardly more than a precarious foothold high up on the western side of the Rapido valley, about half-way along the route from Cassino to Atina. From the lofty slopes of the snow-capped Monte Cairo, rising directly above and overlooking the position, and also from Montecassino to the south and from the mountains to the north, the enemy could observe every access route and direct fire from his guns on it.

Fifth Brigade’s convoys followed the narrow, winding roads and tracks through the hills east of the Rapido valley to a debussing point near the village of Portella. The changeover of each battalion took two nights to complete. The first 5 Brigade troops to arrive, 28 (Maori) Battalion, set off on foot after dark on 19 April on a five-mile march down to the river crossing at Sant’ Elia Fiumerapido and to a lying-up area among trees at the foot of the precipitous

face of Colle Belvedere, where they remained until the following night before taking over from 2/4 Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment. Fifth Brigade assumed command of the sector on the 21st, and during the next two nights 23 Battalion completed the relief of 2 Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, and 21 Battalion that of 2 Battalion, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment. The climb of over 2000 feet to the posts on Colle Belvedere and the adjacent Colle Abate took three to five hours. Laden with their personal gear, arms and ammunition, the men clambered and scrambled over rock faces in the darkness and stumbled and groped along narrow tracks and ridges.

From the village of Cairo in the Rapido valley a road zigzagged around 10 hairpin bends up the almost vertical southern face of Colle Belvedere and then continued onwards and upwards for about two miles to the enemy-occupied village of Terelle, which cleaved to the side of Monte Cairo. Fifth Brigade’s foremost posts, mostly in rock sangars very close to the enemy, were about midway between the top hairpin bend and Terelle: 21 Battalion was astride the road and holding a salient on the reverse slope of Colle Abate, 23 Battalion farther north on Colle Belvedere and facing part of Colle Abate still held by the enemy, most of 28 (Maori) Battalion near the top hairpin bend, and a company of Maoris, 32 Anti-Tank Battery and a squadron of the RAF Regiment (these last two in an infantry role) about half-way down the zigzagging road. It was necessary to hold the flank of the road because there was a gap between the New Zealand sector and the Polish 5 Kresowa Division farther south, in which the terrain precluded the establishment of a permanent junction post. This gap had to be watched constantly – by standing patrols at night – to prevent enemy infiltration across the lines of supply to the New Zealand and Polish sectors.

A company and a half of 27 (Machine Gun) Battalion supported the infantry in the Belvedere–Terelle sector, but for most of the Vickers guns the range was absurdly low. A German band could be seen and heard playing in Terelle, and the enemy also could be seen stripped to the waist and sunbathing, but it was inadvisable for the infantry or machine-gunners to do any shooting in daylight because so much of their position was overlooked from the north, west and south.

Also in 5 Brigade’s sector were seven Sherman tanks, whose crews from 12 Canadian Armoured Regiment had been replaced by men from 18 NZ Armoured Regiment when its A Squadron relieved the Canadian armour in 11 Canadian Infantry Brigade’s sector. A few days later A Squadron in turn was relieved by B Squadron of 19 Armoured Regiment. The changeover at Belvedere

introduced petrol-engined Shermans to the New Zealanders, who were accustomed to the diesel-engined type. The tanks, badly in need of an overhaul, were parked in a bend in the roadway, where there was nothing to see or shoot at without going farther forward. Once or twice a tank did go up to a position from which it could fire into a cave or tunnel on which the artillery, owing to the angle of its entrance, could make no impression.

The artillery was deployed well back, among the tangle of hills and narrow valleys on the other side of the Rapido valley, where the guns might be concealed from enemy observation behind ridges, or dug in and camouflaged in sites – sometimes on the very edge of a road – which gave them sufficient crest clearance for defensive fire when requested by the infantry and for counter-battery and counter-mortar work. The divisional front was covered by 5 Field Regiment and a battery of the 6th in support of 2 Independent Parachute Brigade on the right, 17 Canadian Field Regiment (under New Zealand command) in support of the Canadian brigade group in the centre, and by 4 and 6 Field Regiments (less a. battery of the latter) in support of 5 Brigade on the left. The mediums and heavies of 2 Army Group Royal Artillery were available for the assistance of both 2 NZ Division and the Italian Motor Group.

Both sides fired propaganda leaflets, but while the Allied artillery had the advantage of knowing that those in German could be read by the opposing troops, the enemy had first to identify the occupants of any sector and then ensure that the shells containing the leaflets were correctly addressed, for they had prepared special messages for the Poles, Frenchmen (with separate versions for Moroccans and Algerians), Indians, South Africans, Canadians, Americans, New Zealanders, and the men from the British Isles. The New Zealanders often received leaflets in Urdu or Polish, or addressed to the depressed lower classes of England; on the rare occasions they received those intended for the ‘Kiwis’ it was obvious that the Germans would have done better to have left their shells filled with high explosive. Nor did the British leaflets appear to have much better effect, although a few men of Russian or south-east European origin came into the lines bearing ‘safe pass’ leaflets.

The Germans raided some of the forward posts in the Belvedere- Terelle sector, usually after a preparation of shell, mortar or machine-gun fire, but were driven off with grenades and small-arms fire, and if necessary with artillery and mortar concentrations. During one of several unsuccessful enemy attempts to approach 21 Battalion’s posts on Colle Abate, two men were captured from a unit of 132 Grenadier Regiment of 44 Division, whose sector

extended at that time from Terelle to Monte Cifalco, north of Sant’ Elia. According to a German report ‘all our patrols in the central and southern parts of [44] division’s sector found the enemy in strength holding a continuous line. The positions were most difficult to approach as the enemy was very alert and opened fire at the slightest sound.’

The bringing up of supplies and the relief of posts in the dark ‘bulked very largely in the men’s minds at that time, much more than anything they were called on to do in the way of fighting. ... the most talked of and dreaded business of each day was the nightly walk down to the collecting point for supplies, or to the nearest well (all taped by Jerry) to fill water-cans.’8 After weeks of occupation by troops of different nationalities, some of whom were not particular about hygiene, the positions had become most insanitary. On the reverse slope of Colle Abate a machine-gun platoon was accommodated in sangars which ‘smelt to high heaven & it was difficult to move in darkness without setting up a hell of a clatter among the empty tins that covered the ground. ... The infantry sangars were on the brow of the hill as we saw it [the ground rose again just beyond them]. ... At the foot of the hill in a fairly sheltered position on our right was a group of 3″ mortars. We could almost look down the barrels because of the steepness of the slope.’9

Troops were not expected to spend more than 10 days in the Belvedere-Terelle sector. Sixth Brigade began to relieve the 5th on the night of 29–30 April, when 25 Battalion took over from the 28th, and next night 24 Battalion relieved the 23rd. On the night of 1–2 May, when 6 Brigade assumed command of the sector and while 21 Battalion was still in the line, the enemy attacked the Colle Abate salient. He probably was aware that reliefs were taking place because the opposing lines were so very close, and no doubt wanted to identify the incoming troops. A German patrol, using rifle grenades and flame-throwers, made a determined attempt to break into a house occupied by a section of a platoon of A Company, 25 Battalion, south of the Terelle road, but was repulsed. Shortly afterwards 21 Battalion called for defensive fire to cover its posts on Colle Abate, where the enemy had infiltrated between two platoons of B Company. The platoon on the left was out of communication and seemed to have been overrun. A counter-attack was organised, but the enemy withdrew and contact was restored with the platoon, which reoccupied its posts. The New

The Apennine Mountain Sector, April 1944

Zealanders had about 30 casualties that night. Many of the more seriously wounded who could not be removed before daybreak had to stay in their forward posts until the following night, when 26 Battalion completed the relief of the 21st.

(iv)

The tortuous roads and tracks, by which day-to-day requirements were delivered to the brigades of 2 NZ Division and troops were ferried to and from their mountain sectors, were also used by the heavily laden convoys of 2 Polish Corps dumping ammunition and stores in preparation for the offensive. All movement on each route, therefore, had to be planned in advance, and great care taken to prevent vehicles and troops being found in daylight in the places where the enemy had observation and could concentrate immediate shellfire. With a chain of provost posts linked by telephone and an efficient breakdown service to remove vehicles which blocked the way, the system of traffic control worked remarkably smoothly.

The New Zealand Division and the Poles both used the narrow, two-way road from the Volturno valley (near Venafro) to Acquafondata, which was as far as it was safe to go in daylight. From Acquafondata, in the basin of an old volcanic crater 2700 ft above sea level, two routes, one north and the other south of a ridge, descended westwards to meet again at Hove Dump, near Sant’ Elia Fiumerapido. North Road was the New Zealand Division’s axis and Inferno Track (the southern route) was the Poles’, but in fact they shared both routes.

North Road dropped 2000 feet in 13 miles with so many twists and turns – vehicles had to take two swings to negotiate many of its 21 hairpin bends – that although it was theoretically a two-way route it had to be restricted to one-way traffic. The enemy, in places only a mile or two away, could scan almost its entire length. Only single jeeps and ambulances attempted to use it in daylight; the columns of trucks travelled at night and without lights of any kind – and darkness did not always protect them from shellfire. Not infrequently a vehicle went over a bank. Between dusk and midnight westward-bound columns wormed their way down from Acquafondata to Hove Dump, where they were immediately unloaded; between midnight and dawn they returned to Acquafondata. Jeep convoys, working to a timetable which allowed them on North Road when it was clear of the Acquafondata columns, left Hove Dump with supplies for units reached by the roads branching off to the north and west through Vallerotonda and Sant’ Elia. One of the routes from Sant’ Elia climbed the Terelle ‘Terror Track’ to the upper of two jeepheads serving the Belvedere–Terelle sector, the

farthest point (about 20 miles) from Acquafondata. From the various jeepheads the supplies were distributed by mule and man-pack.

Inferno Track shortened the distance from Acquafondata to Hove Dump by six miles and was much less exposed to the enemy’s view than North Road, but was shelled when daytime traffic raised dust, and was so very narrow and steep, with grades of up to one in four or five, that it was suitable only for one-way traffic and vehicles with four-wheeled drive. A system of control posts, which regulated movement to a bypass area, permitted groups of vehicles to proceed in stages up and down Inferno Track day and night, but it was such a slow and difficult route that some of the Polish transport had to be diverted to North Road each night.

Although located among the artillery gunlines, Hove Dump was considered a safe and convenient harbour for supplies. The ammunition, petrol, rations, and even hay for the mules, were stacked in a clay-walled gully – a dry riverbed said to be an old course of the Rapido – and according to the artillerymen these walls gave immunity from enemy shellfire. Nevertheless, early in May, the Germans managed to land a few shells at the gully’s narrow lower entrance, and set fire to a dump of pyrotechnics placed there by the Poles. This was a portent of the calamity which the Army Service Corps had been assured could not happen.

German artillery activity increased noticeably on 6 May. Heavy calibre guns began to search out gun and mortar positions and laid several heavy concentrations round some of the headquarters positions and on supply roads and tracks. On the 7th, a fine day, shells began to drop into Hove Dump. Eye-witnesses report that ‘a shellburst engulfed a jeep and a huge column of black smoke – probably from a load of petrol – spiralled up into the clear sky, a fine marker for enemy gunners. There was sudden, feverish activity. Drivers jumped to their jeeps and self-starters whirred. Trucks and jeeps, some blackened by fire, streamed out of the gully to safety.’10 Obviously attracted by the smoke, the enemy guns poured shells into the dump, which soon became a blazing inferno, in which whole stores of petrol and ammunition exploded. ‘Viewed from afar by awed onlookers, Hove appeared as a deep gash in the earth from which billowed smoke and flame and with them shuddering explosions. Even stacks of super-heated bully beef were bursting like small-arms fire.’

Hove Dump was finished.11 Stocks of ammunition, petrol, rations, fodder, and many vehicles had been destroyed. The casualties, as far as could be assessed, were about 50, including one New Zealander killed and 26 wounded. Thereafter Acquafondata became the most forward New Zealand dump from which the nightly jeep trains distributed supplies.

(v)

During the five months it had been in action in Italy 2 NZ Division had suffered over 3200 casualties, nearly half of them (1596, including 343 dead) at Cassino between 1 February and 10 April 1944. All its units needed time for training and the absorption of reinforcements who had been arriving in large numbers since the end of the battle at Cassino. A complication was the surplus of senior NCOs, who included those returning from furlough in New Zealand, experienced in desert warfare but strangers to conditions in Italy, and ex-officers who had voluntarily relinquished their Territorial commissions in New Zealand to come overseas, with less combat experience than those who had served in either North Africa or Italy. By this time, also, the 4th Reinforcements, who had been with the Division since 1941, were due for furlough.

The recent reinforcements were sent into the line soon after their arrival. They could get little exercise and no training while confined in cramped shelters in the daytime and standing-to watching for enemy patrols at night; the men who went out on patrol usually were chosen from among the old hands. General Freyberg felt that his infantry had not had sufficient training in mountain warfare and he had no inclination to commit them in a frontal assault in such difficult country. It was preferable, therefore, that the Division should not be part of the striking force and that the main assault by Eighth and Fifth Armies be made elsewhere. The Division’s immediate role was merely to make a series of simulated attacks to contain the enemy on its front, and to provide artillery and mortar support for the Poles, if required, in their attempt to outflank Montecassino from the north. Later, depending on how the battle developed, the Division could expect an exploitation role.

III: The Destruction of the Gustav Line

(i)

General Alexander’s plan for the capture of Rome and an advance of 200 miles up the Italian peninsula was defined in an operation order issued by Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy on 5 May: ‘To destroy the right wing of the German Tenth Army; to drive what remains of it and the German Fourteenth Army North of Rome; and to pursue the enemy to the Rimini–Pisa line inflicting the maximum losses on him in the process.’12

The offensive was to open with a simultaneous frontal attack by the two armies on the Gustav Line on the night of 11–12 May 1944. Eighth Army was to force an entry into the Liri valley and advance up Route 6, and Fifth Army was to drive through the Aurunci Mountains and along an axis parallel to that of Eighth Army but south of the Liri and Sacco valleys. These assaults on the southern front were designed to draw in the enemy’s resources and weaken his forces encircling the Allied beachhead at Anzio. By the time the enemy’s second line of defence, the Hitler Line, had been broken, 6 Corps was expected to be able to break out from Anzio and advance inland to cut Route 6 in the Valmontone area and thus prevent the withdrawal of the troops opposing the advance of Eighth and Fifth Armies. After the capture of Rome Eighth Army was to pursue the enemy on the general axis of Terni-Perugia, and thereafter advance on Ancona and Florence, and Fifth Army was to pursue the enemy north of Rome, capture the Viterbo airfields and the port of Civitavecchia, and thereafter advance on Leghorn.

In Eighth Army 13 Corps (Lieutenant-General S. C. Kirkman) was to make the frontal attack across the Gari River south of Cassino while 2 Polish Corps (Lieutenant-General W. A. Anders) was to strike across the Monte Cairo-Montecassino spur to turn the line from the north; the junction of the two corps on Route 6 was to isolate and ensure the capture of Cassino and the monastery. The role of 1 Canadian Corps (Lieutenant-General E. L. M. Burns), in Eighth Army reserve at the beginning of the offensive, would depend on the progress of 13 Corps. Should 13 Corps succeed in penetrating both the Gustav and Hitler lines, the Canadians were to pass through and exploit up Route 6 to Rome, but if the British corps encountered strong opposition after it had established the initial bridgehead, the Canadians were to cross the Gari and go into action on its left.

Meanwhile 10 Corps (Lieutenant-General McCreery) was to secure Eighth Army’s right flank in the Apennines and also stage

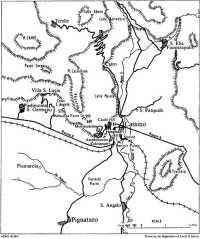

The Cassino Sector

a demonstration in 2 NZ Division’s sector to delude the enemy into expecting an attack against this thinly held part of the line, through which ran the two routes to Atina. On the Adriatic coast 5 Corps, under the command of HQ Allied Armies in Italy, was to hold its front with the minimum of troops and pursue the enemy should he retire.

A scheme was devised in 2 NZ Division to deceive the enemy by simulating a threat along the La Selva – San Biagio section of the road to Atina on 2 Independent Parachute Brigade’s front. The artillery (5 NZ Field Regiment, a South African13 field battery and a South African medium troop) would fire a barrage for 42 minutes, starting at 2 a.m. on 12 May, on Monte San Croce and its western slope, and a troop of heavy anti-aircraft guns would fire on Monte Carella. The 4·2-inch and 3-inch mortars and Vickers machine guns were to cover the right flank of the ‘attack’, and Bren-gunners from one of the parachute battalions were to go forward and engage selected targets on the slopes of Monte San Croce. Two troops of C Squadron, 18 NZ Armoured Regiment’s tanks were to manoeuvre on the road near La Selva. Presuming the enemy would think this ‘attack’ had failed, the Division was to simulate another thrust towards San Biagio on the night of 13–14 May.

For several weeks before the offensive began, the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces,14 taking advantage of a supremacy of nearly 4000 aircraft over the enemy’s 700 (about half of which were based in Yugoslavia or southern France), concentrated on the disruption of the enemy’s road, rail and sea communications in an endeavour to prevent him from accumulating stores to increase his resistance to the forthcoming ground attack. The Allied aircraft hampered and strained the German supply and transport organisation, but did not succeed in isolating the battlefield. In fact, both Tenth and Fourteenth Armies were adequately supplied at the start of the May offensive.

The air forces gave their fullest support during the battle. They bombed headquarters (disrupting HQ Tenth Army and HQ Fourteenth Corps) and command posts, and attacked the German gun positions across the Liri valley and behind Cassino.

(ii)

With a thunderous roar amplified by the mountain echoes, the Allied artillery opened fire at 11p.m. on 11 May against the enemy’s 30-mile front between Atina and the sea. Over 1000 guns were employed by Eighth Army and about 600 by the Fifth. After 40 minutes’ counter-battery fire the bulk of the artillery switched to the corps objectives. Fifth Army began its thrust into the Aurunci Mountains south of the Liri River; in Eighth Army 13 British Corps forced a crossing of the Gari at the mouth of the Liri valley, but 2 Polish Corps failed in its attack on Montecassino.

General Anders’s plan was for 5 Kresowa Division on the right and 3 Carpathian Division on the left to capture part of the ridge about a mile north-west of the monastery, which would give observation over the Liri valley. The Poles’ first objectives included Phantom Ridge and Albaneta Farm, and their second objectives Colle Sant’ Angelo (a ridge beyond Phantom Ridge) and Montecassino.

The benefit of the preliminary 40-minute counter-battery bombardment had been lost when the Poles’ advance began at 1 a.m. on the 12th. The enemy guns and crews were well dug in and the damage done to their communications was quickly repaired. Soon their fire regained almost its full intensity. The Poles captured Phantom Ridge and also Point 593 (less than a mile from the monastery) but were exposed to a ring of artillery and mortar fire, and were repeatedly counter-attacked by the Germans (who were in greater numbers than expected because they were carrying out reliefs in the Cassino sector that night). Weakened by extremely heavy casualties and unable to go on to their final objectives, the Poles were withdrawn to their starting point, where they would need time to reorganise.

The German reaction to this attack was confined at first to the Polish sector; except for some light shelling and mortaring, the adjacent New Zealand sector remained quiet. The only noticeable response to the simulated attack on 2 Independent Parachute Brigade’s front at 2 a.m. was machine-gun fire on fixed lines and shell and mortar fire on likely forming-up points. The tanks from 18 Armoured Regiment trundled up the road to the appointed place near La Selva, fired shells into the darkness ahead, and returned down the road without one retaliatory shot from the enemy.

The artillery of 10 Corps, including some of the New Zealand batteries, and the air force supported the Poles throughout the battle. The New Zealand artillery answered numerous calls for counter-battery and counter-mortar fire on Monte Cairo, Terelle, Belmonte and Atina to lessen the volume of fire the enemy was bringing down on the Polish sector, and also helped to cover the Poles’ withdrawal.

Although the Poles’ attack inflicted correspondingly heavy losses on the enemy (one of whose relieving battalions was believed to have been practically annihilated by shellfire) and divided the attention of the enemy artillery which might otherwise have concentrated on 13 Corps, it made no tactical gains. ‘It is no disparagement of the Poles’ splendid bravery to say that it availed little until successes elsewhere threatened the defenders of

Montecassino with encirclement. ... though the great fortress fell [on 18 May], it was never conquered.’15

(iii)

While the Poles were battling among the hills above Cassino, 13 Corps was struggling to establish a bridgehead across the Gari River south of the town. From this bridgehead General Kirkman planned to turn northwards to cut Route 6 and join up with the Poles and isolate Cassino. The town was to be cleared of the enemy and the road reconstructed through it. Thirteenth Corps then was to advance up the Liri valley south of Route 6 to the Hitler Line.

Starting immediately after the counter-battery fire ceased, 13 Corps (unlike the Poles) at first did not have to contend with shellfire, but the swift-flowing Gari capsized many of its assault boats and swept many downstream, German automatic and small-arms fire caused numerous casualties, and the attackers soon lost the benefit of the supporting artillery barrage. On the right, between the Cassino railway station and Sant’ Angelo, 4 British Division had not completed a bridge before dawn and was unable to do so in daylight, but although lacking support weapons the division clung to a shallow lodgement on the far bank throughout the day. On the left 8 Indian Division succeeded in placing two bridges over the river south of Sant’ Angelo and was joined by tanks of 1 Canadian Armoured Brigade and some anti-tank guns.

Taken by surprise, the enemy made no co-ordinated counter-attack against 13 Corps on 12 May. Instead he threw in his local reserves piecemeal, and hastily assembled in the rear a battle group (including two parachute battalions) at the disposal of 1 Parachute Division, whose command was extended southward over 44 Division’s front in the Liri valley. A regiment of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division was despatched to the Liri valley, but Kesselring, who still expected an Allied landing behind the front, reserved to himself the decision to commit this formation to action.

A bridge was built over the Gari in 4 Division’s sector before dawn on the 13th, and tanks of 26 Armoured Brigade crossed to assist the attack. In the afternoon 8 Indian Division completed the clearing of the enemy from Sant’ Angelo, and 13 Corps’ uneasy foothold across the river was converted into a firm bridgehead. Orders were issued for 78 British Division, reinforced by units from 6 British Armoured Division, to pass through next day and make contact with the Polish Corps (which was to renew its attack)

The Liri Valley

on Route 6 on 15 May. A second bridge over the Gari in 4 Division’s sector was ready for use on the morning of the 14th, and 19 NZ Armoured Regiment, placed under the command of that division, also crossed the river.

The 19th Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel McGaffin16) left the Pietramelara area at short notice, travelled about 30 miles ‘in stygian blackness’17 on the night of 13–14 May, during which two tanks slipped off the road, and was refuelled and ready to go into action at dawn. C Squadron crossed the Gari about 8 a.m. and the other squadrons later in the morning, to take up positions in support of 4 Division, which was to act as a pivot for 78 Division’s wheeling movement to the north and was to be prepared to move against Cassino when it was outflanked.

As 4 Division had not yet cleared the enemy from all of its objectives, the GOC (Major-General A. D. Ward) decided to attack on the southern flank to conform with 8 Indian Division’s line. About 6 p.m. 2/4 Hampshires of 28 Brigade, with B Squadron in support, set out to take Vertechi Farm. The tanks had difficulty in crossing the Pioppeto stream. A scissors bridge, which had been hit during the day, collapsed when the first tank was half-way over; the second tank just failed to jump an eight-foot-wide gap, and the third rolled over on to its side in the run-up on the opposite bank. In another place, however, three tanks managed to cross a temporary bridge, constructed mostly of green willow logs, and reached the objective ahead of the infantry. Supported by these tanks and by fire from tanks still on the other side of the stream, the Hampshires were consolidating on their objective by 6.30 p.m.

A and C Squadrons of 19 Regiment stood by on 15 May in readiness to help 4 Division repulse a counter-attack which was expected at dawn but did not eventuate. B Squadron (less two troops supporting the Hampshires on the southern flank, which was still rather exposed) helped 2 Royal Fusiliers of 12 Brigade clear up a small enemy salient, and claimed the destruction of an ofenrohr18 and its crew and a strongpoint in a house defended by machine guns and mortars, and silenced four machine-gun posts. Tanks from B Squadron accompanied the Royal West Kents of 12 Brigade in an attack beyond Vertechi. One was disabled on a mine, but another scored an unexpected success by discovering and disposing of a Mark IV German tank disguised as a haystack.

By the end of the day 13 Corps had reached the lateral Cassino–Pignataro road, and 8 Indian Division had captured the village of Pignataro.

Meanwhile 78 Division was making slow progress through the bridgehead, where it was delayed by traffic congestion, difficulty in crossing the Gari and Pioppeto, and by shellfire. The enemy was able to direct his guns on targets in the Liri valley because of his undisturbed possession of vantage points on the Montecassino spur, which would have been denied him if the Poles had succeeded in their attack. The Poles intended to renew their attack on 15 May, but unless 13 Corps was within supporting distance, would have little prospect of holding the ridge if they captured it. It was decided, therefore, to postpone the Polish attack until 13 Corps, still advancing under continuous observed fire, was within striking distance of Route 6.

(iv)

While Eighth Army was assaulting the best prepared German defences in the Liri valley and north of Cassino, Fifth Army was making sweeping gains farther south, between the Liri River and the sea, through mountainous country which the enemy had believed impassable for a large force.

Fifth Army could not advance up Route 7 (the Via Appia), which ran along the coast, without controlling the mountain ridges which dominated the road. It was decided, therefore, to strike directly over the mountains. Against the two German divisions south of the Liri, Fifth Army employed the four divisions of the French Expeditionary Corps, composed mostly of Algerians and Moroccans (with French officers) who were experienced and skilled mountain troops, and the two divisions of 2 US Corps in the coastal sector, where 10 British Corps earlier had secured a bridgehead over the Garigliano River.

The French quickly penetrated the Aurunci Mountains. On 13 May 2 Moroccan Division captured the 3000-foot Monte Maio, key to the German defences overlooking the Garigliano River, and then exploited north-westwards towards the Liri. This permitted the French 1 Motorised Division, after clearing the western bank of the Garigliano, to continue along the southern bank of the Liri to San Giorgio, which it reached on the 14th. Farther south 3 Algerian Division next day entered the Ausonia defile, through which the road passes to Pontecorvo, a nodal point of the Hitler Line. Meanwhile 2 US Corps, on the left of the French, crossed the road which runs south from Ausonia to join Route 7 near the coast.

Surprised by the strength and speed of Fifth Army’s advance, the Germans suffered crippling losses in men killed, wounded and captured, and fell back in different directions, 94 Division along the coast and 71 Division to the Esperia defile, through which the road from Ausonia enters the Liri valley. This compelled the enemy to divert to Esperia the formation of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division with which he had intended to reinforce the Liri valley front. It arrived in detail and was defeated in detail – which was to be the fate of all the mobile German divisions. Meanwhile, through the gap in the centre, between the retreating 71 and 94 Divisions, General Juin launched his Mountain Corps, composed of the goumiers and infantry of 4 Mountain Division, with orders to cut the Itri-Pico road, far in the enemy’s rear. Almost unopposed as they crossed the trackless mountain ranges, the French had reached Monte Revole by 16 May, an advance of some 12 miles from the old line near the Garigliano.

Kesselring’s failure to appreciate the strength and momentum of the Allied offensive south of Cassino is evident in a directive he issued to Tenth and Fourteenth Armies in the evening of 15 May, when he ordered that a new line of defence be stabilised from Esperia through Pignataro to Cassino, to permit ‘the continued defence of the Cassino massif.’19 By the morning of the 16th 13 Corps was already holding the road this line was intended to follow. In a telephone conversation early that evening Kesselring and von Vietinghoff discussed the necessity of a further withdrawal and agreed they would have to give up Cassino. The commander of Tenth Army then issued orders for a general withdrawal to the Hitler Line.

(v)

Although 5 Mountain Division, facing 2 NZ Division in the Apennine sector, was one of the formations from which troops were taken, often by companies at a time, to stem Eighth Army’s thrust in the Liri valley, the Germans clearly intended to hold this part of the front, from Cassino northwards, as long as possible.

Acting on evidence from various sources that the enemy was thinning out on the New Zealand front under the cover of strong battle patrols, the Division issued orders for the three brigades to prepare fighting patrols, which were to move out after dark on

the night of 13–14 May, lie up in suitable positions to report on enemy movement, and if possible ambush the enemy patrols to prepare the way for a general advance. Sixth Infantry Brigade, in the Terelle-Belvedere sector, briefed patrols of about platoon strength, one from each battalion, to go out at dusk. The first, from 24 Battalion, attacked a house on the eastern side of Colle Abate, where the enemy had been seen earlier, but came under fire from a number of nearby posts and lost one man killed, seven wounded (one of whom was taken prisoner), and two missing. The Germans laid down defensive fire across the front, through which the patrol withdrew with difficulty. Satisfied that the enemy was still alert and manning his positions, 25 and 26 Battalions disbanded their patrols.

The same night 2 Independent Parachute Brigade repeated, with a modified version, its simulated attack in the vicinity of the road that passes through San Biagio on the way to Atina. Light machine-gun teams went forward under an artillery and mortar barrage on Monte San Croce and Monte Carella. The enemy showed that he was still in position by laying defensive fire in front of his forward posts. A patrol from 12 South African Motor Brigade, in the Division’s central sector, surprised an enemy party of seven men and killed five of them. The dead were identified as being from 1 Battalion, 100 Mountain Regiment, which indicated that this battalion probably had spread out to cover the withdrawal of the other troops previously known to have been there. Nevertheless the Germans in this sector were very alert, constantly firing fixed-line tracer and Very lights, and severed the brigade’s communications with shell and mortar fire.

Late in the afternoon of the 14th the New Zealand artillery laid smoke on an area where the Cassino-Atina road passes through the defile between Monte Belvedere and Monte Cifalco, and in a mixture of smoke and mist the South Africans simulated an attack with machine-gun and mortar fire. Although this brought little immediate response from the enemy, he apparently assumed it presaged a night attack, and after dusk he distributed so much defensive fire of all kinds on the New Zealand front that patrols were greatly hampered and pinned to the ground at times. Enemy aircraft, more in evidence than they had been for some time, bombed Hove Dump and the supply roads during the night and next day (the 15th); they returned the following night to bomb the medium gun areas. As the latter night was very still, sound carried a long way. Enemy mule trains and working parties, which could be heard plainly, were fired on by the artillery and mortars.

IV: The Capture of Cassino

(i)

For Eighth Army’s final assault on Cassino General Leese decided to commit his army reserve (the Canadian Corps) and continue the battle on a three-corps front. To isolate the town and monastery the Polish Corps and 13 Corps were to strike simultaneously on the morning of 17 May, the Poles south-eastwards over the Monte Cairo – Montecassino spur where they had made their previous attempt, and the British north-westwards in the Liri valley to cut Route 6 and link with the Poles. Meanwhile the Canadians were to enter the valley, take over from 8 Indian Division, and continue the westward advance on the left of 13 Corps.

The plan for the second Polish attack on Montecassino was much the same as for the first, but the conditions were more favourable: not only had the enemy lost heavily in the first attack (as had the Poles themselves) but 1 Parachute Division had been compelled to weaken itself further by sending reinforcements to the Liri valley in the vain hope of sealing off the Allied penetrations of the Gustav Line; in addition, the only way of escape from Cassino, along Route 6, was in danger of being blocked.

This time 5 Kresowa Division, attacking in waves of battalion strength, was to capture in turn the northern part of Phantom Ridge, Colle Sant’ Angelo and Point 575 (farther south, overlooking Route 6), and was then to continue the advance downhill and across the highway to meet 78 Division of 13 Corps. Kresowa Division had an unexpected success on the night before the opening of the planned attack. A company, while reconnoitring in force (with supporting fire from 4 and 6 NZ Field Regiments), captured some enemy positions on the northern end of Phantom Ridge, and the remainder of the battalion quickly went forward to exploit this success. The Germans counter-attacked, but were repulsed.

The 17th of May was a day of bitter fighting, much of it hand-to-hand against an enemy who defended his rocky strongholds to the last. In the morning, when the artillery (with the New Zealand guns again participating) fired its programme in support of the attack, a second battalion of Kresowa Division passed through the one already on Phantom Ridge and took Colle Sant’ Angelo, except for some pillboxes on the western side, but came under fire from Passo Corno and Villa Santa Lucia, to the north-west. The Germans counter-attacked from some vineyards under the south-western slopes and were twice repelled; but the Poles were running out of ammunition, and in their third attempt the Germans captured the southern peak of Colle Sant’ Angelo.

Although a third Polish battalion came forward to help restore the losses on Colle Sant’ Angelo, the day’s fighting had cost Kresowa Division so many lives that it could go no farther.

The primary objectives of 3 Carpathian Division, which attacked at the same time as Kresowa Division, were two key positions of the German defences, Albaneta Farm and Point 593 (a few hundred yards to the east). A battalion, accompanied by engineers, advanced to the gorge north of Albaneta Farm to clear it of the enemy and his mines, but as this task took longer than anticipated, Albaneta Farm was brought under neutralising fire while a second battalion was committed to an attack on Point 593, which it captured despite a German counter-attack. This battalion then attempted to reach Point 569, just to the south of 593, but was obstructed by the ruins of an old fort and came under mortar fire from the monastery, about half a mile away, and machine-gun fire from Point 575. Although a third battalion joined in the attack, the Poles were unable to take Point 569, and were halted within 200 yards of Albaneta Farm by fire from steel pillboxes.

The Carpathian Division took up defensive positions for the night, with orders to prevent a German withdrawal along the ridge from Montecassino to Albaneta Farm, and next morning (18 May) finally cleared the enemy from Albaneta Farm and Point 569. A patrol of 12 Podolski Lancers met no resistance from the 30 men, many of them wounded, who still remained in the monastery, where the Polish standard was hoisted over the ruins at 10.20 a.m.

(ii)

The decision to launch the Polish Corps attack on 17 May had been taken the previous evening, when 13 Corps had made sufficient progress in the Liri valley: 78 Division had pushed north-westwards through the last defences of the Gustav Line, while 4 Division had straightened out its line south of Montecassino.

B and C Squadrons of 19 NZ Armoured Regiment co-operated with the infantry of 4 Division on the 16th in an attack across the Pignataro road to reduce a small salient which divided 10 and 12 Brigades. The advance began at 6.30 p.m. B Squadron and the Royal West Kents, on the left, had gone some way towards their objective (a point about 1000 yards south of Route 6) when they met the enemy approaching as if to counter-attack (or perhaps to reoccupy positions vacated earlier), and after some very confused fighting in the failing light – complicated by the infantry’s inexperience in the use of the No. 38 wireless-telephony link to keep in touch with the tanks – halted on the ground they had gained. In this engagement the Englishmen had earned the New Zealanders’

admiration for their ‘sheer guts and unhesitating obedience to orders’.20 The Germans also had fought with great determination. Their ofenrohr crews had lain concealed in the long grass until the tanks were nearly on top of them. B Squadron had two tanks knocked out, two officers killed, and seven men wounded. Next morning 150 enemy dead, all claimed as the victims of tank fire, were counted in the squadron’s sector.

On the right C Squadron gained the line of the Pignataro road about half a mile from its junction with Route 6, but had outdistanced the infantry (the Bedfordshires and Hertfordshires), who had halted in the darkness. A strongpoint in a house was disposed of by tank fire, but a storm of mortar and machine-gun fire caused many casualties. A line was stabilised with the tanks in close support of the infantry.

When the Polish Corps and 13 Corps launched their concerted attack on 17 May, 78 Division, continuing its wheeling movement to the north-west, at first met sharp resistance, but this began to weaken as the attack progressed. The village of Piumarola, about two miles beyond the Pignataro road, was finally captured in the evening after a stiff fight with the garrison of German paratroops.

Meanwhile, on the inner flank, 4 Division conformed with this wheeling movement. In the morning its infantry, supported by tanks of 19 Armoured Regiment, advanced against negligible opposition to reach Route 6 south of Montecassino. B Squadron, having already had several days’ hard fighting, was replaced by a troop of A Squadron, which accompanied the Royal West Kents beyond the objective of the previous night and gained the highway at the foot of the mountainside below the monastery. A troop of C Squadron crossed Route 6 farther to the east and shot up positions near the junction of the road to Pignataro, which allowed the Bedfordshires and Hertfordshires also to reach the highway. A troop of A Squadron covered 2 Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry in an advance which, against light machine-gun fire, reached a point near the railway south of the town. These gains brought 19 Armoured Regiment into the area of the original New Zealand objective for which the regiment had battled unsuccessfully in March.

By this time the escape route from Cassino and the monastery was restricted to the mountainside and, farther west, to the narrow strip of valley between the mountains and the railway running parallel with Route 6. In anticipation of a German attempt to break out that way during the night, Route 6 was patrolled and

the artillery put down harassing fire, but most of the enemy already had slipped away; only 70 prisoners were taken, many of them medical orderlies. It had been necessary for Kesselring personally to order General Richard Heidrich’s 1 Parachute Division to retire, ‘an example,’ he says, ‘of the drawback of having strong personalities as subordinate commanders.’21

On the morning of the 18th 10 Brigade approached Cassino with two battalions supported by tanks from A and C Squadrons, and without meeting any resistance – although a few Germans gave themselves up as prisoners – secured the Baron’s Palace, the Colosseum and the Amphitheatre. The 4th Division then made contact with 1 Guards Brigade in the town and with the Poles. Mines and booby traps were thick on the ground and in the rubble, and great care had to be taken when investigating buildings. The tank crews were warned not to forage among the ruins, and especially not to touch the knocked-out New Zealand tanks still in the town. Having completed its task in the Liri valley, 19 Regiment was released by 4 Division.

Shortly after midday 3 Carpathian Division despatched a patrol down the slopes of Montecassino and made contact with 78 Division on Route 6 below Albaneta Farm. Nevertheless parties of Germans covering the withdrawal from Cassino, and some who had not received orders to withdraw, continued to resist throughout the day, and isolated pillboxes had to be destroyed individually. On 5 Kresowa Division’s front repeated attempts to dislodge the enemy were thwarted by the fire from strongpoints on the southern slopes of Colle Sant’ Angelo and from Point 575. By evening General Anders decided that, rather than incur further casualties,22 it would be better to pin down and exhaust the enemy. A counter-attack from Villa Santa Lucia, farther west, was repulsed, and early next day (the 19th) this place was reported clear; but Passo Corno, at a height of about 3000 feet on the side of Monte Cairo, remained in German hands.

(iii)

While 13 Corps and the Polish Corps were fighting the battle to isolate Cassino, the Canadian Corps, entering the Liri valley on the left of the 13th, struck towards the Hitler Line through country dotted with strongpoints and furrowed by many small streams. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division, after taking over from 8 Indian Division near Pignataro, fought its way to the Forme d’Aquino, a

stream which straggles across the valley through marsh and gully to join the Liri River near San Giorgio. This natural obstacle allowed the enemy to disengage his forces in front of the Canadians on the night of 17–18 May – while farther north he reluctantly retired from Cassino through the gap between 13 Corps and the Poles.

Although the enemy had lost Montecassino, his northern flank was still secured by his retention of positions on the slopes of Monte Cairo, including the small town of Piedimonte San Germano, perched on a spur overlooking Route 6. On his southern flank, however, his misappreciation of General Alexander’s plan and of the Allies’ ability to cross the Aurunci Mountains had resulted in his failure to halt Fifth Army’s drive. The French had taken Esperia by 17 May and were less than four miles from Pontecorvo the following afternoon. Alexander now ordered Eighth Army ‘to use the utmost energy to break through the “Adolf Hitler” line in the Liri valley before the Germans had time to settle down in it’.23 He also directed the Poles to press on to Piedimonte to turn the line from the north, and the French, after reaching Pico (west of Pontecorvo), to encircle the southern flank.

Eighth Army almost broke through the Hitler Line before the enemy ‘had time to settle down in it’. Early in the evening of 18 May the Derbyshire Yeomanry Group from 78 Division, advancing rapidly south of the railway, reached the Aquino airfield, on the edge of the main defences of the line. A few tanks entered the village of Aquino, but were without infantry support so withdrew. An assault was made on Aquino at daybreak on the 19th, but when the sun suddenly dispersed the heavy morning mist, the tanks of 11 Canadian Armoured Regiment, supporting a battalion of 36 British Infantry Brigade, found themselves in the open, some of them within point-blank range of German anti-tank guns. Shell and mortar fire compelled the infantry to retire, but the tanks, protected to some extent by a smokescreen, held their ground throughout the day. When the regiment finally withdrew at dusk, it had lost 13 Sherman tanks, and every tank of its two leading squadrons had received at least one direct hit by high-explosive shells.

On the same day 3 Canadian Infantry Brigade, supported by a battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment, tried to penetrate the defences farther south, between Aquino and Pontecorvo, but after emerging into the open from thick patches of stunted oak trees, the infantry were halted by machine-gun and mortar fire, and the tanks by anti-tank gunfire. By this time it was obvious that a major

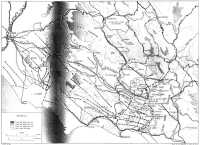

The Advance to Rome, 11 May–4 June 1944

assault would be necessary to break the Hitler Line in the Liri valley.

V: The Breaking of the Hitler Line

(i)

From the hill town of Piedimonte San Germano the Hitler Line ran southwards across the Liri valley to the vicinity of Pontecorvo and, after crossing the river, swung south-westwards over the mountains to Terracina on the coast. Although far from complete, its defences were even more elaborate than those of the Gustav Line; they included armoured pillboxes, reinforced concrete gun emplacements and weapon pits, underground shelters, and minefields and wire to obstruct tanks and infantry. The line’s great weakness, however, was that there were too few troops to man it adequately. The 90th Panzer Grenadier Division, which held the sector in front of the Canadian Corps, had been reduced to little more than a motley collection of units in which men of every arm were intermingled. On its left, opposite 13 Corps, was 1 Parachute Division, and on the right in the Pontecorvo-Pico sector was 26 Panzer Division.

The French captured Pico on 22 May and began to outflank the Hitler Line from the south, but the enemy showed no sign of abandoning it. He defended Pontecorvo that day against a Canadian thrust. Early next morning 1 Canadian Infantry Division, with very heavy artillery support, launched its main assault between Aquino and Pontecorvo and, in a day in which the Canadians experienced their hardest and most costly fighting in Italy,24 succeeded in piercing the line. Nearly 1000 Canadians were killed or wounded, most of them from units on the right flank, which was exposed to fire from Aquino. The German casualties included several hundred killed and over 700 prisoners.

The 5th Canadian Armoured Division passed through the breach on the 24th and exploited to the far bank of the shallow, meandering Melfa River, which crossed the valley about four miles west of Aquino before flowing into the Liri. A battle group from the infantry division pushed along the road from Pontecorvo and next day crossed the Melfa just above the junction of the two rivers. By nightfall on the 25th the Canadians’ bridgehead west of the Melfa extended from the Liri to the railway.

The continued presence of the enemy at Aquino after the breakthrough had prevented 78 Division of 13 Corps from advancing,

as planned, on the right of the Canadians on the 24th. It was decided, therefore, that 6 British Armoured Division should take a route through the Canadian sector south of Aquino, but as 5 Canadian Armoured Division was not yet clear of this route, 13 Corps’ advance was postponed until next day. Early on the 25th patrols found Aquino and also Piedimonte (which 1 Parachute Division had held against the Poles’ attacks) clear of the enemy. Thirteenth Corps then closed up to the Melfa with both 6 Armoured Division and 78 Division, while 8 Indian Division, with 18 NZ Armoured Regiment under command, occupied small towns and villages in the foothills on the northern side of the Liri valley.

(ii)

Led by C Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson25) drove up Route 6 on 25 May to join 8 Indian Division, commanded by Major-General D. Russell. The New Zealanders wondered at the evidence of the recent fighting. ‘For miles the ground was all torn up by shells.’ The Hitler Line ‘looked really wicked. ... The boys had never seen anything quite like it, except photos of the Maginot Line away back in the very early days of the war. Even now that those large, cunningly hidden anti-tank guns were tame, the thought of advancing into their muzzles made you feel sick inside.’26

C Squadron’s tanks followed 6/13 Royal Frontier Force Rifles of 19 Indian Infantry Brigade from Route 6 towards the foothills west of Monte Cairo, where the lower slopes were so closely cultivated and wooded that the tank crews could not see far ahead and at times lost sight of the infantry. Castrocielo was deserted. The civilians had taken refuge in nearby caves. Some of the Indians pushed on beyond the town to take the craggy peak of Madonna Castrocielo. They were fired on by German machine-gunners sheltering behind large boulders, but with the protection of a smokescreen created by the tanks, closed in and killed or drove off the enemy.

A Squadron of 18 Armoured Regiment joined 1 Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of 19 Brigade and set off past Castrocielo towards Roccasecca, a small town near the Melfa River. During the advance one of A Squadron’s tanks fell into a 20-foot well which had been roofed over and covered with earth.27 Another

tank, upon turning a corner of a narrow lane, came face-to-face with a German turretless recovery or maintenance tank, and captured two of its crew. Next morning (26 May) the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders entered Roccasecca unopposed. The last of the Germans were cleared from the Liri valley east of the Melfa River.

(iii)

Meanwhile, on 23 May, 6 Corps (commanded now by Major- General Lucian Truscott) had opened the attack to break out from the Anzio beachhead, and next day 2 US Corps had occupied the coastal town of Terracina. Kesselring had brought the last of his mobile divisions, 29 Panzer Grenadier, from the Civitavecchia area to prevent a breakout from the southern flank of the beachhead and to halt the American drive towards Terracina, but it had not arrived in time to accomplish either task.

If Fifth Army could succeed in blocking Tenth Army’s line of retreat by cutting Route 6 at Valmontone, there was a chance that a rapid advance up the Sacco valley by Eighth Army might achieve the encirclement of 14 Panzer Corps. In the afternoon of 25 May, however, General Clark on his own volition swung the main axis of 6 Corps’ advance to the north-west, away from Valmontone to the Alban Hills, with the result that the town was not captured until 1 June. This decision and Eighth Army’s slow progress sacrificed what may have been an opportunity to cut off and destroy part of Tenth Army.

General Clark himself says, ‘I was determined that the Fifth Army was going to capture Rome and I probably was overly sensitive to indications that practically everybody else was trying to get into the act.’28 Alexander, however, intended that the Americans should enter Rome and that the British and their other allies should bypass it. ‘I had always assured General Clark in conversation that Rome would be entered by his army; and I can only assume that the immediate lure of Rome for its publicity value persuaded him to switch the direction of his advance.’29

Displaying greater defensive capabilities than the Americans had anticipated, the Germans delayed 6 Corps’ advance in the vicinity of the Alban Hills. ‘The greatest irony was that if the VI Corps main effort had continued on the Valmontone axis... Clark could undoubtedly have reached Rome more quickly than he was able to do by the route northwest from Cisterna. ...

Ironically, too, when the Fifth Army finally broke through the last of Fourteenth Army’s defences, it accomplished this by a surprise night infiltration along the eastern side of the Alban Hills between the hills and Valmontone. ...

‘For at least three days German strength in front of Valmontone and westward to the Alban Hills was inadequate to have stopped a strong attack by even a secondary effort; even in subsequent days German strength was not sufficient to have halted the main effort of the VI Corps had it been directed in that direction. For more than a week before the capture of Rome, the rear and right (west) flank of the German Tenth Army, withdrawing slowly toward the Caesar Line, were exposed and threatened with a trap which the German commanders feared would be closed, but which was not.’30

This argument, however, overlooks the fact that Route 6 was not Tenth Army’s only way of escape. As General von Senger und Etterlin says, ‘it must not be concluded that Alexander’s plan to use strong forces from the [Anzio] bridgehead for an attack towards Valmontone would have met with success.’31 Von Senger’s 14 Panzer Corps fell back along a road which left Route 6 at Frosinone – which Eighth Army had not yet reached – and passed through the foothills of the Simbruini Mountains towards Subiaco. Along this road, well to the north of Valmontone, ‘seven divisions were pulled back in five days and nights. This was achieved despite the fact that the road was practically unusable in daylight because of the enemy’s air superiority. ... XIV Panzer Corps could only have been annihilated if the enemy had then also succeeded in pinning it down at Frosinone or alternatively if he had pushed forward beyond Valmontone towards Subiaco, which would have involved him in major difficulties of terrain.’32

Nevertheless, on the eve of the British and American cross- Channel invasion of France, the Allied armies were fulfilling their professed aim in tying down in Italy German troops who otherwise might have been diverted to western Europe. The German High Command had consented on 22 May to the transfer of the Hermann Goering Panzer Division (which had been earmarked for France) from Leghorn to the Rome area, and to its replacement at Leghorn by 20 Luftwaffe Field Division from Denmark. The Hermann Goering Division, travelling in daylight and losing heavily from Allied air attacks as it went, did not go into action until

the 27th, and its units, like those of the other divisions drawn into the battle, were committed piecemeal in small counter-attacks.

VI: The Fall of Rome

(i)

Despite instructions from the German High Command that ‘if at all possible, no withdrawal is to be made without the personal concurrence of the Führer’,33 it was obvious by nightfall on 25 May that a retreat could not be postponed much longer. Plans were made, therefore, for the northern wing of Fourteenth Army to hold firm between Velletri (near the Alban Hills) and the sea while its left wing fell back with the right wing of Tenth Army as slowly and economically as possible to the Caesar Line, which Hitler ordered Kesselring to defend at all costs.

The German forces were to retire to a series of lines of defence and inflict ‘such heavy casualties on the enemy that his fighting potentiality will be broken even before the Caesar line is reached’.34 In Tenth Army’s zone the first of these lines was near Ceprano, where the main Liri valley forked into the valley of the upper Liri, through which Route 82 led northward to Sora and Avezzano, and the valley of the Sacco, through which Route 6 led north-westward towards Rome. The right wing of Tenth Army could use both avenues of escape. On the northern side of the main Liri valley Route 6 entered the narrow Providero defile before joining Route 82 at Arce, and then turned sharply to the south before crossing the upper Liri River by a bridge at Ceprano. Direct access from the Liri valley to the Sacco valley was blocked by the upper Liri River and by the Isoletta Reservoir, formed by a dam below the confluence of the Liri and Sacco rivers. On one route, therefore, Eighth Army would have to force its way through a defile; on the other it would have to cross a difficult water obstacle.

In the first of the three stages of Eighth Army’s advance, 13 Corps on the right and the Canadian Corps on the left were to secure the Arce-Ceprano line at the head of the Liri valley; in the second the Canadians were to advance some 10 miles along secondary roads south of Route 6, and in the third along Route 6 to link up with Fifth Army at Valmontone. In the second and third stages, depending on the strength of the resistance, 13 Corps was to be ready to advance either along Route 6 or on a more northerly

route on either side of the Simbruini Mountains. Tenth Corps was given the task of protecting Eighth Army’s right flank by sealing off the approaches from the east. The Polish Corps, which would be pinched out at Monte Cairo between 10 and 13 Corps, was to be withdrawn because of its heavy casualties and lack of reinforcements. The French Expeditionary Corps of Fifth Army was advancing on Eighth Army’s left flank.

It had been decided that the honour of taking Rome should go to Fifth Army. Eighth Army’s task was to break through the Caesar Line in the Valmontone-Subiaco sector (between the Alban Hills and the Simbruini Mountains) and then exploit northwards along the roads east of Rome.

(ii)