Chapter 12: The End of the War

I: The Occupation of Trieste

(i)

THE campaign in Italy ended officially at midday on 2 May, but news of the unconditional surrender of the German Army Group C did not reach Eighth Army until the evening. This surrender did not apply to the German troops east of the Isonzo River; nor did many of those on the other side of the river receive the order to cease fire owing to the disruption of the enemy’s communications. Eighth Army issued an order at 9.40 p.m. that its troops were to cease fire west of the Isonzo unless the enemy committed an overt hostile action, in which case ‘normal operational action’1 would be taken. Throughout 2 May, therefore, Eighth Army continued to advance in north-eastern Italy, with troops from 6 Armoured Division in the mountains north of Udine and with the New Zealanders along the Adriatic coast to Trieste, where the German garrison was still holding out against the Fourth Yugoslav Army.

Ninth New Zealand Brigade set off along Route 14 east of Monfalcone about 8.30 a.m., with the armoured cars of A Squadron of 12 Lancers out in front. A little earlier A Company and some carriers from 22 Battalion had brought in 190 Germans who had been occupying gun positions in and around Duino, on the coast. Accompanied by tanks from B Squadron of 20 Regiment, 22 Battalion led the brigade to Sistiana, about two miles beyond Duino, where the enemy was met again. A small force consisting of 7 Platoon, some tanks and carriers at once went ahead, inflicted a few casualties and took eight prisoners. The tanks also engaged

three enemy boats about five miles offshore, and set one on fire; another was abandoned, but the third escaped.

At Sistiana the highway forks. While 22 Battalion continued along Route 14 by the coast, Divisional Cavalry Battalion took the more hilly inland route through Aurisina, San Croce di Trieste and Prosecco. Shortly after midday B Squadron of 20 Regiment and 22 Battalion halted while the air force bombed enemy positions at Miramare, on a small peninsula about three miles from Trieste When three of the Lancers’ armoured cars and Lieutenant-Colonel Donald in his jeep approached Miramare about 2.30 p.m., they were met by a German coastal artillery commander, who offered to surrender his garrison. ‘He said he had based his surrender on his interpretation of the directive issued by Doenitz.2 He had not received a copy of this directive himself, but his radio operators had picked up the message containing it being sent to Army Gp C. ... He was under the orders of the Naval Commander at Fiume, who had refused to approve his decision and ordered him to fight on. This he refused to do. ...’3 Fifteen officers and 600 men were disarmed and taken prisoner.

As the day wore on it became increasingly apparent that the enemy preferred to surrender to the New Zealand Division rather than to the Yugoslav Army, which was in control of a large part of Trieste. The first risings of the partisans in the city apparently had taken place on the night of 30 April – 1 May, before the New Zealanders had begun their advance from the Piave River. The partisans had been joined in the city on 1 May by Yugoslav tanks. The Germans’ reluctance to resist the New Zealanders was shown by their failure to blow the tunnels through which the road passed near Miramare and to demolish the road itself.

A road block a mile or two beyond Miramare was quickly silenced by some tanks of B Squadron of 20 Regiment, which ‘sprayed the pillboxes with their Brownings and then charged straight through. ... the tanks were ordered to push on and leave their prisoners to be collected later. The drivers then accelerated, the last few miles were covered at a grand pace, and at three o’clock on that sunny and momentous afternoon the regiment’s first tanks, the spearhead of the Division, entered Trieste.’4

Donald reached the city about half an hour later and instructed 22 Battalion by radio to enter, which it did at 4 p.m. It received a tumultuous welcome, mixed with odd bursts of rifle and machine-gun fire which failed to disperse the excited crowds. The Germans

still held many buildings, and snipers were busy. One man in the battalion was wounded. Large numbers of Yugoslav troops and a column of old Stuart tanks paraded the streets. Amid further cheering, Brigadier Gentry, closely followed by General Freyberg, arrived about a quarter past four.

Meanwhile A Squadron of 20 Regiment and Divisional Cavalry Battalion met resistance at Prosecco on the longer, winding inland route. The enemy used mortars and a six-pounder anti-tank gun which had been captured from the battalion the previous evening. The anti-tank portée had developed engine trouble in the afternoon and its crew had set out to rejoin the battalion at dusk, but had driven past it. ‘They had stopped and asked a soldier at the side of the road the inevitable question of the day, “Dove Trieste?”, only to realise too late that it was a German who replied in English: “Trieste is there; and for you the war is over.” That was not quite so. They all escaped the very next day. Two of them seized the first chance, during a dive-bombing raid, and so, in a very short space of time indeed, were able to give valuable information to the leading cars of 12 Lancers which picked them up as they came along. The rest hid up in a house until things had quietened down. ...’5

A Squadron’s tanks engaged some enemy-occupied houses and the infantry took a few prisoners. Divisional Cavalry then proceeded down the road to Trieste, which it entered about 6 p.m., and went through to the southern part of the city.

(ii)

Colonel Donald, accompanied by two German officers, endeavoured to obtain the surrender of the garrison still holding out in the Tribunale (law courts) in Trieste. He also led some armoured cars, tanks, and C Company of 22 Battalion to the 700-year-old fortified castle, the Castello San Giusto, on the hill in the centre of the city, where he left Major Cross6 to accept the surrender of the garrison while he himself returned to the Tribunale.

C Company was greeted at the castle about 5.30 p.m. by much indiscriminate shooting. The Germans fired a bazooka at one of the tanks, but missed. Yugoslav troops threatened to shoot anyone who went into the castle, but C Company passed through the gates and entered the courtyard, where the Germans were waiting. The garrison of 12 officers and 170 men was disarmed, and 13 Platoon took up positions previously occupied by the Germans. The castle was well stocked with ammunition and prepared for siege.

Late in the evening the New Zealanders and Germans shared a meal. ‘From time to time members of Tito’s partisans had called at the castle gate to demand entrance, but in vain. From houses on higher ground partisan snipers had been shooting at movement within the walls. The captured force now suggested with some enthusiasm uniting with the New Zealanders and fighting side by side if the situation grew worse. Major Cross, suddenly immersed in the intricacies and duplicities of peace, replied non-committally. Next morning the garrison, under escort, marched down the road to the waiting three-tonners. Howls of protest and anger rose from the demonstrating partisans and civilians, who demanded the prisoners. The New Zealanders saw the Germans off safely.’7

At the Tribunale Donald could not persuade the garrison commander to surrender; he was an SS officer who ‘was still humbugging undecidedly and was apparently under the influence of alcohol.’8 Donald therefore arranged with the Yugoslav commander that tanks of C Squadron of 19 Regiment and C Squadron of the 20th would surround the building and give it a 20-minute pounding with their guns and Brownings. First the square was cleared of all troops and civilians, and at 7 p.m. 18 tanks at ranges of from 20 to 50 yards blew gaping holes in the walls and through the windows of the Tribunale. The Germans took shelter in the cellars and had few casualties, but the Yugoslavs entered the building and by morning had rounded up some 200.

Headquarters 22 Battalion was established in the Albergo Regina and the companies disposed in the northern part of the city, including C Company at the castle. The 27th Battalion, which entered the city at dusk, dispersed in the vicinity of the docks. Headquarters 9 Brigade was set up in the Grande Albergo della Citta. Divisional Headquarters took over the castle built in 1845–46 for Archduke Maximilian at Miramare. ‘Many pairs of Kiwi eyes goggled – the “poor country lads” had never seen anything like it. But notwithstanding several fine suites of rooms with sunny balconies overlooking the Adriatic the GOC would not budge out of his caravan.’9

About 10 p.m. an Austrian civilian brought a message to Colonel Donald from the German commander of the Trieste and north-western coastal area (Lieutenant-General Linkenbach), who wished to surrender his forces to the British. Donald sent the battalion’s Intelligence officer (Second-Lieutenant Currie10) and a provost sergeant with the Austrian and a white flag to the general’s villa, which

commanded a view of the city and the port from the northern outskirts and was guarded by over 700 men. The general agreed to discuss terms of surrender and, with two of his staff, was brought to the Albergo Regina. Partisans were met on the way, but on learning that the occupants of the jeep were under British escort, did not interfere.

The discussion at Headquarters 22 Battalion was facilitated by a German-Italian interpreter and an Italian-English one. Linkenbach wanted an assurance that his men would not fall into Yugoslav hands. Eventually, after Donald had conferred with General Freyberg, it was decided to remove all the Germans to a British prisoner-of-war camp. Currie took the German general back to his headquarters by jeep, again under a white flag, and D Company arrived at the villa about 4 a.m. to disarm the garrison. At daybreak Currie led the column down the hill: behind his jeep came eight German staff cars containing Linkenbach and his staff, a German truck and motor-cycle, eight D Company trucks carry ing prisoners, and about 300 Germans on foot. Altogether 24 officers and 800 men were safely escorted to the cages near Monfalcone.

About half past eight that morning (3 May), after a message was received from the commander of the 1200-strong German garrison at Villa Opicina, a village a couple of miles north of Trieste, A Company of 22 Battalion and three tanks of A Squadron of 20 Regiment were sent to negotiate the surrender. One of the tanks was ditched on the way, and the infantry three-tonners could not pass a demolition, but the two remaining tanks carried a platoon up the road. Here again the Germans were willing to become prisoners of the New Zealanders but not of the Yugoslavs. While the company commander (Captain Wells11) was negotiating with the Germans, the Yugoslavs opened up with mortars and small arms. A Company came under fire, ‘and to the sorrow and anger of the battalion,’12 Lance-Corporal Russell13 was killed and another man wounded.

A Company joined the Germans. ‘Casualties had been, and continued to be, inflicted on the Germans by Tito’s troops. ... Here we were, among armed Germans who greatly outnumbered us, and subject to the same dangers in a private war which was being prosecuted after the official cessation of hostilities. ... Small groups formed round English-speaking German officers who conversed brightly on the course and ultimate end of the war. Most

were of the opinion that Germany and England should have allied themselves to fight against Russia – and that that day might even come to pass. ...’14

Wells visited the Yugoslav brigade headquarters and what seemed to be a divisional headquarters in an attempt to reach a settlement, and eventually the commander of 20 Yugoslav Division and a British liaison officer from the Yugoslav headquarters were taken to Headquarters 9 Brigade to confer with Brigadier Gentry. It was decided that, rather than risk more lives, A Company should withdraw and the Yugoslavs would be allowed to take the Germans prisoner.

Meanwhile the New Zealand tank commander (Captain Foley15) was attempting to stop the fighting between the Yugoslavs and Germans. ‘With a German colonel and a captain on board, “both very scared”, he took his tank down the road to the German lines, where he found bitter fighting raging. ... His proposal that he was going over to the partisans’ lines to speak to them was considered “verr dangerous” by the colonel, but after some parleying in no-man’s-land with “some Tito men”, carried out in Italian with his gunner’s assistance, “we got them to understand that if they stopped firing the war would be over.”

‘Foley then adopted the role of referee, dashing between the two parties, who had again resumed the fight, “and by much frantic waving, with my heart in my mouth, got them to stop. ... Then proceeded further along the line and the same performance went on. Villa Opicina was taking an awful pasting so decided to go and stop that too.” Negotiations with first a lieutenant, then a major, a brigadier (“a real pirate”), and, last of all, a general only confirmed that the Yugoslavs were determined not to let the Germans – and all their equipment – be surrendered to the New Zealanders.’16

By this time the New Zealanders had been ordered to return to their units, and another troop of tanks arrived to ascertain what was delaying them. Two Austrians on a motor-cycle followed them back to Trieste and were their only prisoners.

The surrender of the Villa Opicina garrison to the Yugoslavs ended hostilities in Trieste and its environs. Although the situation in the city was to remain tense and confused for some time, the Division had fired its last shot in the war.

On the morning of 2 May 6 Brigade was faced with two tasks: the occupation of Gorizia, and the sending of a force to Grado to capture or drive back into the sea the Germans who were landing there while fleeing from the Yugoslavs. The 26th Battalion was to take Gorizia, while 24 Battalion was to go to Grado.

Sixth Brigade’s progress along Route 14 on 1 May had been exasperatingly slow because of the huge volume of traffic and the delay at the Piave River, where the Royal Engineers completed a 340-foot Bailey bridge late that day; 8 Field Company’s Bailey on four barges anchored in the river on piers was not open until next day. It was raining heavily when 26 Battalion, in the lead, crossed the Piave, and it did not reach its dispersal area just short of the Isonzo until 5.30 a.m. on the 2nd. A Company, which had the role of protecting Divisional Headquarters, continued along Route 14 beyond the Isonzo.

Taking the road on the west bank of the Isonzo, 26 Battalion set off about midday in the direction of Gorizia. About 12.45 p.m. B Company, at the head of the column, saw evidence of recent fighting at the outskirts of the town, six miles north of Monfalcone. Groups of Chetniks (Yugoslav royalist partisans) close to the road obviously belonged to a large force in the hills west of the river. Colonel Fairbrother attempted to discuss the situation with one of their officers, but could not do so without an interpreter. The Chetniks were not hostile, however, so he decided to continue into Gorizia. Actually 26 Battalion, without knowing it, had driven through the no-man’s land of a battle between the Chetniks and Tito’s communist forces.

Machine-gun fire could be heard in Gorizia when the New Zealanders debussed and prepared to enter the town. The main bridge over the river had been demolished, but a wooden one was wide enough for jeeps and carriers. The shooting died down as B and C Companies and Tactical Headquarters occupied various buildings. D Company stayed with Battalion Headquarters on the west bank of the river to guard the footbridge and the transport assembled there. Two Chetniks were persuaded to lead the Adjutant (Captain Cox17) to their headquarters a few miles from the Isonzo, where the local commander assured him that his men would not resume hostilities while the New Zealanders were in the Gorizia area if Tito’s forces did not cross the river. Cox also made contact with 6 British Armoured Division, to whom 12,000 Chetniks later surrendered.

Gorizia was held by troops whom Tito had ordered to occupy the territory of Venezia Giulia as far as the Isonzo River. Throughout the afternoon noisy demonstrators paraded the streets, singing, shouting slogans and waving flags and banners. ‘Yugoslav Communist bands carrying red, blue, and white flags with the red star prominent in the centre were shouting “Death to the Fascists. Death to the Italians. Long live Tito. Viva Stalin. Viva the Allies.” Parties of Italians answered them with “Gorizia for the Italians. Viva America. Viva England” and carried the red, white, and green flag of Italy. Both factions carried the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes.’18

Divisional Headquarters ordered 6 Brigade to concentrate two battalions at Gorizia until relieved by 56 Division, which was coming under the command of 13 Corps to occupy the town and the Latisana area but was not expected to arrive before 3 May. Sixth Brigade, therefore, sent 25 Battalion and C Squadron of 18 Regiment to join the 26th. When these reinforcements arrived in the late afternoon of the 2nd, the New Zealanders at Gorizia received a more responsive and attentive hearing from the Yugoslavs.

The 26th Battalion’s transport, which was stranded on the western side of the Isonzo because of the lack of an adequate bridge at Gorizia, was ordered to go back to Route 14 and return by Route 55 (on the eastern side of the river), the road by which 25 Battalion had arrived. While following a Yugoslav car on the way back to Route 14, the New Zealanders’ convoy was fired on by the Chetniks, who may have mistaken their identity, and one man was shot. Next day 167 Brigade of 56 Division relieved 25 and 26 Battalions, which withdrew from Gorizia. The New Zealand tanks stayed a few days longer until they could be replaced by a British unit.

Meanwhile 24 Battalion cleared the enemy who still lingered between Route 14 and the coast west of the Isonzo. Nearly 100 Germans were collected at Belvedere and Grado, and 160-od who had come by sea from Yugoslavia gave themselves up between Grado and the Isonzo.

(iv)

While 21 Battalion completed its task of rounding up the Germans cut off near the Piave River on 1 May, the remainder of 5 Brigade resumed the advance – at a snail’s pace – along Route 14. The 28th Battalion, later joined by A Squadron of 18 Regiment, was despatched on an excursion to the north. Leaving Route 14 at San Giorgio in the morning of the 2nd, the Maoris saw no enemy at

Palmanova or elsewhere, found Udine occupied by troops of 6 Armoured Division, spent the night at Palmanova, and rejoined 5 Brigade next day.

A small party from 23 Battalion on 2 May secured the surrender near Latisana (where Route 14 crosses the Tagliamento) of some 500 Germans who were willing to give themselves up to the New Zealanders but not to the Italian partisans. When 21 Battalion reached Latisana, partisans reported that an enemy force 4000- strong was landing from ships at Lignano, near the mouth of the Tagliamento. Lieutenant-Colonel McPhail obtained permission to deal with this, and despatched B, C and D Companies, B Squadron of 18 Regiment and the battalion’s carriers to Lignano. On the way they met about 200 Germans who were being escorted to Latisana by partisans.

Major Swanson, who went ahead with three carriers to investigate, found a large force of Germans landing from 36 ships of various types at the mouth of the Tagliamento, protected by naval craft holding off three British torpedo boats at a range which prevented them from interfering. The Germans were fleeing from the Yugoslavs and believed they were landing in country still held by their own forces and therefore would be able to make their way into Germany. Swanson saw their commander, who agreed to a truce. The ensuing argument between McPhail, Swanson and the battalion Intelligence officer (Second-Lieutenant Craig19) on one side and three German officers on the other lasted longer than three hours, during which time a large landing barge was beached and vehicles and artillery unloaded. The Germans insisted that they were going back to Germany, but McPhail told them they would have to lay down their arms immediately. Eventually the enemy agreed to surrender. The sight of B Squadron’s tanks in hull-down positions might have influenced this decision.

A prisoner-of-war cage was set up at Latisana and another at Lignano to accommodate the 6000 Germans, most of whom were army and navy men who had been employed on coastal defence and port work in and around Trieste. Next day they began unloading food from their fleet to feed themselves until other arrangements could be made. While they were doing this they set fire to four ships, but after the naval commander was severely reprimanded, there was no further attempt at sabotage. Several days passed before 21 Battalion was able to hand over all its prisoners to the divisional cage and return to 5 Brigade.

Between 30,000 and 40,000 Germans were estimated to have been

taken prisoner by the Division between the River Po and Trieste. A more precise figure could not be calculated because of the numbers handed over by the New Zealanders to the partisans, and thos brought in by the partisans to the Division.

The total German casualties in the last offensive were estimated at 5000 killed, 27,000 wounded and sick, and some 407,000 taken prisoner or accepted as surrendered enemy. The campaign in Italy undoubtedly had drained the enemy’s strength more than the Allies’. Between 10 July 1943, when the invasion of Sicily began, and 9 April 1945, the total German casualties (from figures based on enemy records) were estimated to be 426,339, and the losses to the Allied ground forces in killed, wounded and captured were 304,208. By 2 May the enemy’s losses (excluding those in the final capitulation) had increased to 658,339, and those of the Allies to 320,955.

(v)

This, of course, was not the first time General Freyberg had participated in the final act of a campaign. At the end of the First World War, as a brigadier commanding 88 Brigade of 29 Division in pursuit of the Germans retreating in Belgium, he had been ordered on 11 November 1918 to seize the bridges over the River Dendre at the town of Lessines, 20-odd miles from Brussels. With a detachment of 7 Dragoon Guards Freyberg had galloped on horseback into the town, and in the last minute before 11 a.m., when the Armistice came into force, had prevented the demolition of the main bridge and the escape of more than 100 Germans. For this exploit he was awarded the second bar to his DSO.

By the end of the Second World War Freyberg had spent altogether ten and a half years fighting the Germans. He had conducted long advances in North Africa and Italy. In the last offensive, therefore, he brought an unrivalled background of martial experience to the command of the New Zealand Division, which (while 43 Lorried Indian Infantry Brigade was under command) comprised four infantry brigades and an armoured brigade supported by highly efficient artillery, engineers, and other services.

On 8 May, when the unconditional surrender of all German forces on land and sea and in the air had been announced, Freyberg addressed the Division’s commanding officers and heads of services and praised the work of all arms during the 23 days of the advance from the Senio River to Trieste. First he drew attention to what had been achieved in rear of the Division. The NZASC trucks ‘were often working the clock round for 36 hours on end during our big ammunition dumping periods. ... we functioned as

a mobile division with adequate troop carriers and originally had petrol for 300 miles, food for 12 days and sufficient ammunition for two battles.’ To provide the necessary troop-carrying transport and still maintain the Division over a distance of 200 miles ‘was a truly magnificent performance’. The medical services ‘were constantly stepped up behind us – there were complete surgical teams always available and even nursing sisters were moved up well forward so that our casualties had treatment equivalent to that of a general hospital.’

What the engineers had achieved ‘in crossing seven rivers and various odd canals was really extraordinary – they too often worked the clock round.’ The Division had crossed these water obstacles with ‘over 5,000 vehicles and 20,000 men and 165 tanks at a speed very much faster than most and while the other divisions on parallel axes arrived at their objectives with only a coy of a bn we had all these troops there ... because of the engineering work’ on bridges and rafts.

The plan in the opening battles had been to smash the enemy and not simply to drive him back, the General said. That had necessitated great speed in planning, and the Division had employed the maximum artillery in the shortest possible time. The Intelligence branch of Divisional Headquarters, working in co-operation with the Mediterranean Air Interpretation Unit (West) and the artillery, had kept the most careful intelligence about every position the Division was going to attack. The main outline of the artillery programmes had been settled at the divisional orders group conferences, but all the detailed work in fixing individual targets had to be done during the planning and much movement. ‘You owe the fact that you have had relatively few casualties to the work of the “I” section and the whole set up of the Div Arty.’ The artillery had fired over 500,000 rounds during the 23 days; this included 20,000 rounds by 5 Medium Regiment, half the total it had fired during the whole of the campaign in Africa.

Ninth Infantry Brigade had received ‘its first baptism of fire as a brigade. ... I think that the way in which they worked was in the fine traditions of the other infantry brigades. ...’ The infantry, ‘who after all win the battles’, throughout the advance had done ‘as well as they usually have done’. The armour ‘everybody agrees did very well. Apart from what they did in battle I think great credit is due to the workshop side because of the way the tanks kept going mechanically.’

The General was especially pleased with 12 Lancers’ contribution: ‘We can learn much from them – in particular the collecting and

sending back of information. ... It would have been a risky operation to go 200 miles from the Adige without protective recce. That responsibility was taken from me because for 25 miles on either side of our axis they searched for formed bodies of the enemy. The boldness of our move was due to the fact that it was not carried out blindly and the cavalry were able to save many bridges – or where the bridges had been they were able to recce routes round and to search and find out what the opposition was. ...’20

(vi)

Between 1 April and 3 May 1945, from the time of the Division’s return to the line on the Senio River until the cessation of hostilities at Trieste, its losses were 1381 dead and wounded. This total21 was shared among the formations as follows:

| Dead | Wounded | Total | |

| 4 Armoured Brigade | 24 | 89 | 113 |

| 5 Infantry Brigade | 47 | 279 | 326 |

| 6 Infantry Brigade | 53 | 278 | 331 |

| 9 Infantry Brigade | 86 | 361 | 447 |

| Artillery | 10 | 43 | 53 |

| Engineers | 13 | 57 | *70 |

| Others | 8 | 33 | 41 |

| 241 | 1140 | 1381 |

* The engineers’ casualties include a man who died of wounds on 7 May, one killed in action and another wounded on 19 May.

This brought the Division’s total battle casualties in Italy to 8668.22

II: Confrontation with the Yugoslavs

(i)

After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the First World War, both Italy and the newly created state of Yugoslavia claimed the province of Venezia Giulia, of which the peninsula of Istria, the Slovene littoral and the port of Trieste form part. As the price of her participation in the war on the side of the Allies, Italy was awarded territory which advanced her northern frontier to the Brenner Pass and also gave her Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, northern Dalmatia (except Fiume) and some Adriatic islands. She

relinquished Dalmatia to Yugoslavia in 1920, but annexed Fiume four years later.

Marshal Tito hoped that when the Germans were defeated his Yugoslav Army would be able to seize all of Venezia Giulia east of the Isonzo River. The Western Allies, however, were determined to prevent the settlement of a frontier dispute in this manner; they also intended to secure Trieste as a port from which to supply their future occupation zones in Austria. During a visit to Belgrade in February 1945 Field Marshal Alexander persuaded Tito to agree that the Supreme Allied Commander should be placed in charge of all operations and forces in Venezia Giulia; but he realised that it might be difficult to enforce this arrangement without physical possession of the territory.

The Yugoslav Army, sustained by supplies from the British and Americans, launched its offensive towards Trieste on 20 March, three weeks before the Allied armies began their last offensive in Italy, and made good progress from the start. The Germans, retreating in Italy and before the Russians in Hungary, also pulled back as fast as they could in Yugoslavia. Tito announced on 30 April that his troops had reached the suburbs of Trieste. Already, on the 26th, however, Alexander had proposed to the Chiefs of Staff in London that he should ‘seize those parts of Venezia Giulia which are of importance to my military operations’23 as soon as possible, including Trieste and Pola (at the southern tip of Istria) with their communications to the north, and that he should inform Tito of his intentions. The British Prime Minister and the President of the United States had concurred, and the Supreme Commander had been ordered on 28 April to establish Allied military government over the province, including that part of it already occupied by the partisans. Alexander informed Tito of his intentions on the 30th, but the latter’s reply, while offering facilities in and from Trieste and Pola, showed that, contrary to the Belgrade agreement, the Yugoslavs regarded all the territory east of the Isonzo River as their property. Mr Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff told Alexander to hold firm and, if possible, to concentrate troops in the region with whom he might enforce his authority.

Alexander reported to Churchill on 1 May: ‘Tito’s regular forces are now fighting in Trieste, and have already occupied most of Istria. I am quite certain that he will not withdraw his troops if ordered to do so unless the Russians tell him to.

‘If I am ordered by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to occupy the whole of Venezia Giulia by force if necessary, we shall certainly be committed to a fight with the Yugoslav Army, who will have

at least the moral backing of the Russians. Before we are committed I think it as well to consider the feelings of our own troops in this matter. They have a profound admiration for Tito’s Partisan Army, and a great sympathy for them in their struggle for freedom. We must be very careful therefore before we ask them to turn away from the common enemy to fight an Ally. Of course I should not presume to gauge the reaction of our people at home, whom you know so well.’24

(ii)

As has been related, the first formation of Eighth Army, the New Zealand Division, entered Venezia Giulia on 30 April, met Yugoslav partisan irregulars near Monfalcone next day, and reached Trieste and Gorizia on 2 May. General Freyberg advised the commander of 13 Corps (General Harding) in the evening that Tito’s forces had not captured Trieste. ‘I contacted partisan Town Major and tried [to] find a senior Yugoslav officer but was informed no Yugoslav general would arrive until tomorrow. Have therefore taken over town and harbour and all installations. ...’ But the occupation of Gorizia by Tito’s forces was ‘well organised and complete.’25

Next day (3 May) contact was made for the first time with the commander of the Fourth Yugoslav Army, General Drapsin. At San Pietro, a small town about 20 miles east of Trieste, the commander of 37 Military Mission26 (Lieutenant-Colonel J. Clarke) and the senior New Zealand Intelligence officer (Major Cox) met Drapsin and Tito’s chief of staff (General Jovanovic). The latter protested ‘in the name of Marshal Tito ... against your troops in crossing into our operational zone. ... “I must ask your commander to withdraw his troops at once behind the Isonzo. You are getting in the way of operations we are undertaking to the north, and in Gorizia your tanks have broken up a partisan demonstration and protected local Fascists. You are interfering, too, with our civilian administration.”‘27

Clarke reported to Freyberg that Drapsin claimed that the Allies had not captured Trieste but had merely wiped out certain remaining pockets of resistance, and he therefore could not see the need for such a considerable concentration of forces in the town; he understood that, although the Allies were to have access to the port

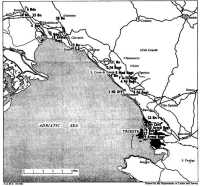

Situation, 4 May 1945

of Trieste, their troops were not to have gone east of the Isonzo, and he did not see what had been gained by fighting troops going so far; he claimed also that the Italian authorities in Trieste had been definitely fascist and therefore a new administration had been installed and was functioning already.

The New Zealand Division was given a copy of a formal protest from Tito to Alexander which said, ‘this moment I have received signal from my 4th Army saying tanks and infantry units of Allied Forces which are under your command have entered Trieste, Gorizia and Monfalcone, cities liberated by the Yugoslav Army. Since I do not know what was meant by that, I wish you would give me your immediate explanation of matters: with respects. Signed J. B. Tito.’28

The chief of staff of the Fourth Yugoslav Army (General Jaksic) issued what was tantamount to a threat of force: ‘In the name

of HQ 4 Army we request Allied troops immediately to withdraw to west bank river Isonzo and that Allied Military authorities do not mix in our internal affairs. After this warning 4 Army will not be responsible for anything that might happen if our request is not met. This is categorical.’29 When this was shown to General Freyberg on 4 May, he told Colonel Clarke to demand an explanation from the Yugoslavs, and to say that ‘we would meet force with force if necessary.’30 Freyberg then conferred with General Harding, who approved of the instructions he had given Clarke, and said that higher authority took the view that Tito was trying a bluff; but Harding agreed that they could not plan on this assumption. The two generals discussed what should be done if their forces had to withdraw to a tactical line.

Clarke reported to Freyberg that he had seen Drapsin, who had assured him there was ‘no question of their ever using force of arms against us – and gave me a long story to the effect that during 1000 years the Jugoslavs had never laid hand on their allies. I said that that was all right, but it was a threatening signal. He said that it was a question of interpreters and the language difficulty. I said that that was not very satisfactory, and suggested that he explain the whole thing to General Harding tomorrow, and place before General Harding any complaints which he might have. He said he would be delighted to do that. I asked him if he could guarantee that he would not attack our troops and pointed out that if he did we would resist most violently. He said there was no question of their ever attacking us – the blood of Jugoslavia and England had flowed together etc. etc. etc. ...’31

(iii)

Already the Yugoslavs had begun to administer Venezia Giulia as an integral part of Yugoslavia. Their military government issued decrees aimed at crushing fascism and securing their grip on Trieste. A curfew was imposed on the civilian population, and demonstrations of national sentiment were forbidden, a restriction which gave authority for the suppression of all pro-Italian activity.

Much depended on the demeanour of the New Zealanders who shared the occupation of Trieste with the Yugoslavs. At a divisional conference on 4 May General Freyberg stressed how important it was to ‘establish very firm touch with the various branches of the community.’ He suggested that games of soccer be arranged with the Yugoslav Army, that race meetings be held, and ‘anything that will help relieve the tension will be to the good. ... In the

meantime we must have a policy of defence. I have arranged that if there is any trouble in Trieste we should withdraw our troops out of it. If we did not it would mean committing the whole Division and there would be most unwelcome casualties and much acrimony.’32 The GOC had decided upon a plan for 5 and 6 Brigades to take up a position west of the city behind which 9 Brigade would withdraw, but this was only a precaution ‘and there is not much likelihood that we shall have to use it.’33

Thirteenth Corps declared that it would continue to occupy the points reached by its leading troops at the time of the German surrender in Italy while negotiations were in progress with the Yugoslav Army for the use of the port of Trieste and the road and railway from it into Austria; thereafter the corps would be responsible for safeguarding these communications. The New Zealand Division was to stay in Trieste and Monfalcone and the intervening coastal belt, 56 Division was to secure the corps’ access on Route 14 westward over the Isonzo River, and 91 US Division was to take over the territory to the north, including Gorizia and Palmanova. All troops were to be ready to defend themselves immediately if attacked, and were ‘to take all possible action short of actually opening fire’34 to prevent conflict between local factions. General Harding’s intention, ‘in the unfortunate event’ of the Yugoslav Army starting hostilities, was to withdraw from Trieste and hold a bridgehead east of the Isonzo River with the New Zealand Division on the right, 56 Division in the centre, and the American division on the left. Meanwhile, ‘minor incidents must be accepted. ...’35

The corps instructions were discussed at a divisional conference in the evening of 4 May. General Freyberg warned that ‘you must be at fairly short notice and keep your people well in hand. Tito has moved a division in NE of our L of C [lines of communication] with Monfalcone. The country is very difficult – we can’t use tanks except on the road. What we have got to be prepared to do if they cut the road is to get some elbow room for ourselves. ... If the situation deteriorates we shall have to be prepared to occupy the positions tomorrow night.’36 An operation order was issued for the action to be taken if this became necessary.

Ninth Brigade was disposed with Divisional Cavalry Battalion in the centre of Trieste (where it took over the castle from 22 Battalion), the 22nd in the northern sector, and the 27th in the

southern, where it was required to prevent interference with the dock installations; tanks of 19 and 20 Regiments were in support. The remainder of the Division was spread out between the city and the Isonzo River.

The New Zealanders and the Yugoslavs both patrolled the streets of Trieste, the latter usually in groups of about a dozen, every man carrying an automatic. The Yugoslavs held parades and pro- Tito demonstrations, with their troops fully armed and their weapons loaded. They swiftly dispersed an unarmed mob of Italians who attempted to stage a counter-demonstration. The Italians ‘came marching along the waterfront carrying a New Zealand flag, an American flag and numbers of Italian flags. As they marched they chanted over and over “Italia” “Italia” and finally halted in front of Bde HQ where they began singing a patriotic song. ... Partisans appeared everywhere and began firing automatics from the hip over the heads of the crowd. No one was hurt in the immediate vicinity. ... The crowd panicked and a large proportion fled to the Albergo Citta overwhelming our two sentries on the door.’37

After parading through the streets 20 Armoured Regiment left Trieste on 5 May to join 6 Brigade in the Monfalcone region, which halved the number of tanks supporting 9 Brigade. Next day, because it had been decided that an international representation of the Allied forces in the city would be preferable to a solely New Zealand one, a battalion from 363 Regiment of 91 US Division and a battalion of the Scots Guards from 56 Division relieved Divisional Cavalry Battalion and 27 Battalion respectively, and the two New Zealand units moved to the Barcola area, near the northern outskirts. Headquarters 9 Brigade remained in operational command.

(iv)

Field Marshal Alexander had reported to Mr Churchill on 5 May that Tito ‘now finds himself in a much stronger military position than he foresaw when I was in Belgrade, and wants to cash in on it. Then he hoped to step into Trieste when finally I stepped out. Now he wants to be installed there and only allow me user’s right.

‘We must bear in mind that since our meeting he has been to Moscow. I believe he will hold to our original agreement if he can be assured that when I no longer require Trieste as a base

for my forces in Austria he will be allowed to incorporate it in his New Yugoslavia.’38

Churchill replied that he was ‘very glad you got into Trieste, Gorizia, and Monfalcone in time to put your foot in the door. Tito, backed by Russia, will push hard, but I do not think that they will dare attack you in your present position. Unless you can make a satisfactory working arrangement with Tito the argument must be taken up by the Governments. There is no question of your making any agreement with him about incorporating Istria, or any part of the pre-war Italy, in his “New Yugoslavia”. The destiny of this part of the world is reserved for the peace table, and you should certainly make him aware of this.’ The Prime Minister added that, ‘to avoid leading Tito or the Yugoslav commanders into any temptation, it would be wise to have a solid mass of troops in this area. ...’39

Alexander sent his chief of staff (Lieutenant-General W. D. Morgan) to Belgrade on 7 May to seek an agreement with Tito that the Yugoslav forces should withdraw behind a line east of Trieste and that the Allied Military Government should take over the administration of the territory west of this line. Tito insisted, however, that the region should remain under the political control of Yugoslavia. Since this was a matter which could be settled only by the Governments, Alexander informed Tito that it had passed out of his hands, but in the meantime he proposed to use the port of Trieste and maintain the lines of communication in north-east Italy and Austria.

The news of Germany’s unconditional surrender was received in the evening of 7 May, and the victory in Europe was celebrated next day – VE Day. But there was little jubilation in Venezia Giulia, where the New Zealanders, British and Americans stood to their arms again; for them the victory had brought an uncertain peace.

The Yugoslav forces continued to move north-westwards through Venezia Giulia, and occupied towns and villages on both sides of the Isonzo River as far north as Caporetto, but later withdrew from the west bank. Eventually an estimated 57,000 were within the Trieste–Monfalcone–Gorizia region, armed with a high proportion of automatic weapons and supported by horse-drawn and some tractor-drawn artillery, including German 88-millimetre, 75-millimetre and 105-millimetre pieces, as well as anti-tank guns and an armoured formation believed to have 52 Stuarts. Their dispositions,

strengths and movements were unobtrusively investigated and reported.

As the international negotiations might be protracted indefinitely and the attitude of the Yugoslavs was unpredictable, 13 Corps issued orders for the security of its forces, which were to be organised for immediate local defence in an emergency, and were to hold in reserve petrol for 100 miles, supplies for seven days, and additional quantities of ammunition. The New Zealand Division concentrated with 5 Brigade in the hills east of Monfalcone, 6 Brigade farther east again, and the artillery in the proximity of the infantry; 9 Brigade continued to hold Trieste with five battalions (including the Scots Guards and Americans) in the city and north of it. For the time being the Yugoslavs controlled the civil administration (but had no jurisdiction over the Allied troops) east of the Isonzo River, and the Allied Military Government exercised the same authority west of the river.

(v)

The tension between the Allied and Yugoslav forces was relaxed in the second week of May, when friendly overtures were made by both sides. A party of British and American officers visited Ljubljana as the guests of General Drapsin, who was hailed as liberator of the city. The Slovene premier, Drapsin and local officials made speeches from the balcony of a university to a crowd who displayed banners, chanted ‘Our Trieste, our Istria’, and applauded any mention of the Allied leaders. A Yugoslav military band advertised, in Slovene, Italian and English a concert at Monfalcone, and played music representative of the different nationalities. At Iamiano, in the hills east of Monfalcone, the Maori Battalion was on friendly terms with the partisans and peasants, who were delighted to discover that some of its men were of Maori- Dalmatian descent, and that the Maoris shared their love of singing.

Except for the Maoris who could overcome the language barrier, however, the New Zealanders did not get to know the Yugoslavs well. They admired Tito’s forces for having tied down many German divisions in the Balkans and for having fought so courageously for so long. ‘But we came up against a barrier of reserve which discouraged any individual mixing in Venezia Giulia. We and the Yugoslavs met on the football field or at other sporting events. We got drunk together at formal dinners. We saluted each other’s officers. But when the matches were over or the dinner done you realised that, though you might know Yugoslavs better, you did

not know any one individual Yugoslav better. There was fraternisation but no friendship, mingling but no meeting. The Tito troops may have had orders to avoid us except on official occasions, or they may have genuinely disliked us as intruders into what they felt was their country. The civilians were either unwilling to mingle with Western troops, and so be singled out as being pro-British or pro-American, or they disliked us too. As a result it was only towards the end of the first month of Yugoslav administration that any real contact developed at all, and then mostly in the villages and outlying areas. In Trieste itself there was never any really close association comparable to that which rapidly grew up between the Italians and the British, American and New Zealand troops.’40

The Italians of Trieste came more than half-way to meet us. Desire for protection, desire for bully beef and the chance to buy a pair of army boots or an old blanket, friendliness for the troops whose arrival had prevented the city passing completely to the Yugoslavs, natural friendliness (there is more than a touch of the Viennese about the Triestini) and calculated designs to influence our opinions may all have entered into this. ...

‘As a result the ordinary soldier heard the Italian case from every angle, and heard very little of the Tito case. He had come, moreover, to regard the Italians as full allies, not, as did the Yugoslavs, as very recent enemies who had invaded their country only four years before.’ The New Zealanders saw that there was an Italian majority in Trieste itself, and that Venezia Giulia was at least mixed in race, ‘and they blamed the Yugoslavs for prolonging the active service period of our armies long beyond the end of the war by claiming the immediate administration of Trieste for Yugoslavia.’41

III: An Agreement Is Reached

(i)

The New Zealand Division could not be employed in hostilities against Yugoslavia without the permission of the Government. On 14 May the Prime Minister, Mr Fraser, who was in San Francisco, consulted with the acting Prime Minister (Mr Walter Nash) and his colleagues in Wellington, and advised Mr Churchill that he was ‘in entire agreement with the proposed action of the United Kingdom and the United States to halt aggression on the part of Yugoslavia, and consider that it is our duty to assist by

making our Division available to Field-Marshal Alexander for that purpose’. Fraser asked for an assurance that the proposed action ‘will be strictly confined to the resistance of aggression and will not involve interference in any way with the purely internal affairs of Yugoslavia, such as the restoration of the monarchy, and that our troops will not be used for that or similar purposes.’42 Churchill replied that ‘the proposed operations will take place, if they do, on Italian not Yugoslav soil and will be in no way concerned with the internal affairs of Yugoslavia, in which we have no desire to interfere.’43

Fraser also asked General Freyberg for an appreciation of the situation in Venezia Giulia. In a comprehensive survey the GOC reported that the situation was ‘not only fraught with political complications but even the risk of armed conflict with the Yugoslav Army. ... the Allies must be prepared to enforce their will if necessary. I consider that with the shortage of troops here, and feeling as you do, full operational control of your Division should be given [to the Allied Supreme Commander].’44

Presumably with the intention of presenting a fait accompli of ostensibly popular government, the Yugoslavs were imposing civil administrations sponsored by themselves in Venezia Giulia. Already they had given authority to the CEAIS (the Italo-Slovene Citizens’ Executive Committee) in Trieste, which was to be ruled as an autonomous city inside the Slovene littoral of a communist Yugoslavia.

Field Marshal Alexander, in a special message on 19 May explaining the issues at stake to all the Allied armed forces in the Mediterranean theatre, declared that apparently Marshal Tito intended to establish his claims to Venezia Giulia and territory around Villach and Klagenfurt in Austria by force of arms and by military occupation. ‘Action of this kind would be all too reminiscent of Hitler, Mussolini and Japan. It is to prevent such actions that we have been fighting this war. ... it is our duty to hold these disputed territories as trustees until their ultimate disposal is settled at the peace conference. ...’

Tito expressed through the Yugoslav News Agency resentment and surprise at Alexander’s statement, and asserted that the presence of Yugoslav troops did not imply conquest. Yugoslavia was prepared to co-operate with the Allies but could not allow herself ‘to be humiliated and tricked out of her rights.’45

The Allied forces prepared for the possibility of the failure of the international negotiations and the start of hostilities. The 2nd

United States Corps (rejoined by 91 Division) came under the command of Eighth Army and occupied a sector between 13 Corps and 5 Corps, which was in Austria. In the New Zealand Division 5 Brigade moved to the Barcola area near Trieste, which enabled Divisional Cavalry Battalion and 27 Battalion to re-enter the city and relieve the Scots Guards and the American battalion, which returned to their own divisions.

General Freyberg thought it necessary to advise Mr Fraser on 20 May that the situation ‘is at the moment most unsatisfactory. There is the makings of trouble both here and in Austria. The Yugoslavs have moved a large force into and around Trieste and Gorizia. We are now following suit. ... I want the New Zealand Government to know the fact that we are sitting at the point of greatest tension and that fighting may break out. If it does we must expect a number of casualties. ...’46

Thirteenth Corps issued instructions on 20 May that, if all negotiations failed, it was to take ‘certain offensive measures’ to secure the port of Trieste and the lines of communication towards Udine so that the Allied forces in Austria could be supplied, and was to establish Allied Military Government with full authority in the region occupied east of the Isonzo River. As the first phase of what was hoped would be a ‘peaceful penetration’ to the east, the New Zealand Division on the right, 56 Division in the centre, and 10 Indian Division on the left were to form a front covering a lateral road and track through Sgonico–Dol Grande–Comeno–Montespino, north-north-west of Trieste. Later the three divisions were to advance by stages to the ‘Blue’ (or Morgan) Line, about 17 miles east of Trieste.

If the Yugoslavs withdrew before the start of the second stage (which was to secure the lateral road and railway through Villa Opicina–San Daniele–Montespino), the Allied troops were to follow up out of contact and complete the whole operation as early as possible; they were to collect bona-fide stragglers and deserters and march them under escort to the nearest Yugoslav unit or to the Morgan Line, and were to apprehend, disarm and evacuate through prisoner-of-war channels Yugoslavs who offered resistance. If it became necessary to ‘mop up’ during this phase, the Yugoslav troops were to be surrounded quickly and unobtrusively, and called on to surrender, while the strongest possible demonstration of strength was made and leaflets printed in Slovene, Serbo-Croat and Italian were distributed. If the Yugoslavs offered resistance, the Allies were to employ naval and artillery bombardment, air

support, tanks and other heavy weapons to achieve their object quickly and with as few casualties as possible.

The Allied forces quietly eased forward to the line north-north- west of Trieste on 22 May. Whatever perturbation this might have caused among the Yugoslav commanders, there was no reaction among their troops in the localities occupied by 6 NZ Infantry Brigade and 20 Armoured Regiment, in very stony, scrub-covered hills in the Sgonico–Sales–Samatorzo area, only a few miles from Trieste. Farther north 56 Division held positions from Dol Grande to Comeno, and 10 Indian Division from Comeno to Montespino.

The Yugoslavs firmly but politely asked the British to withdraw from Comeno, which they wanted as a communications centre, and threatened to establish road blocks behind the forward British positions. Eventually it was agreed, however, that both British and Yugoslav troops should remain where they were until they received orders from higher authority.

Many road blocks appeared in the approaches to Trieste, and at these the Yugoslav sentries demanded both Yugoslav and New Zealand signatures of authority for vehicles to pass, but soon the control of New Zealand traffic was greatly relaxed; there was only one report of a New Zealand vehicle being stopped after 26 May. When a Sherman tank gently pushed over a Yugoslav barricade in rear of the New Zealand forward positions, the sentries did not try to stop it but resignedly cleared the remnants off the road.

Fifth Brigade, which was near the coast between Barcola and Prosecco, found that the Yugoslavs still held Villa Opicina in strength. A patrol from 23 Battalion discovered that a wireless station near Barcola was guarded by about 50 armed men, and while reconnoitring towards Trieste met a group of 150–200 Yugoslavs, who politely but firmly refused permission to go farther. The Yugoslavs set up a road block on the Prosecco – Villa Opicina road, and 28 Battalion retaliated with a traffic post on the same road. When a Yugoslav officer in a car travelling towards Villa Opicina failed to stop, the Maori sentry fired his Bren gun into a rear tyre. The irate officer was escorted to Battalion Headquarters, where he was told he was at fault in not obeying the traffic rules, and was then allowed to proceed on his way.

A mild sensation occurred on the evening of 21 May when about 25 large Russian-type T34 tanks manned by Yugoslavs entered Trieste and passed along the waterfront in the direction of the docks; about half of them went through the city and were not seen again, and after a day or two the remainder withdrew in the direction of Villa Opicina.

Orders were given on the 24th that all social functions were to

cease, but the ban was lifted three days later. A party of Yugoslavs approached 28 Battalion and ‘put up a proposal that they would invite the Maoris to their functions if they, the Maoris, would reciprocate. ... and the battalion put on a dance every night of the week; civilians, Tito’s men, and the troops were soon on the best of terms.’47 Other units, including 9 Brigade’s battalions in Trieste, also held dances. Small parties of Yugoslavs came unarmed into 6 Brigade’s lines and fraternised with the New Zealanders.

(ii)

On 21 May Marshal Tito, in reply to an Allied Note, conceded for the most part the Allied requirements for holding the disputed territory in trusteeship, but made conditions for the retention of Yugoslav troops under the Supreme Allied Commander in the area controlled by the Allied Military Government, and for the continued use by the Allies of the existing civil administration. This volte face might have been dictated by Allied diplomatic pressure, Russian influence, or the Allied preponderance of force in the disputed territory and the obvious firmness of Allied intentions.

General Freyberg was able to advise the New Zealand Government on the 23rd that the situation had eased considerably. ‘The Yugoslav Government has sent a friendly note and, although there are still divergences of opinion which will require adjustment, I believe that the matter will be solved amicably and it will then be possible for the New Zealand Division to be released from its operational role. This may not be until the end of June. ...’48

Sixth Brigade completed the relief of 9 Brigade in Trieste in the afternoon of 1 June, and the 9th occupied the area vacated by the 6th. The troops’ quarters in the city hotels and villas were very luxurious in comparison with bivouacs in the hills. If the negotiations with the Yugoslavs broke down, 6 Brigade was to remain as a firm base in Trieste for 48 hours, during which time the Navy was to put to sea with the non-fighting vessels, and the 2000 men of 55 Area, which operated the port, were to be given a safe passage out of the city.

The many Yugoslav troops who remained in Trieste and the police of the Difesa Popolare (an armed partisan organisation) took ‘a high handed attitude with the people who were alleged to be Fascists. Many incidents of beating up and looting were reported but our troops were not in a position to interfere as Tito’s

Government were administering the city and AMG49 were unable to operate.’50 In case the Yugoslavs might attempt to drive the New Zealanders from the city, a close watch was kept, artillery tasks prepared, and plans drawn up to meet all eventualities.

A demonstration intended to express approval of the Yugoslav-imposed regime took place in the Piazza dell’ Unita in Trieste in the evening of 8 June. All British troops were warned in advance to keep clear, and 6 Brigade ordered its men to be in their billets, where they stood by ready to quell any disturbance. But apparently the demonstration did not meet with the response that had been anticipated: the audience, mostly organised parties of factory workers, moderately applauded some 10 speeches, which seemed to give more emphasis to the advantages of communism than to incorporation with Yugoslavia. An Italian band was greeted with greater enthusiasm.

Next day the New Zealanders held a trotting meeting at the Montebello course, Trieste, which was attended by Generals McCreery, Harding and Freyberg and a large part of the Division. In case there should be trouble with the Yugoslavs, a plan had been prepared beforehand for evacuating the course, and men carried tommy guns or pistols. The meeting was a social and financial success; the totalisator handled over £20,000, and after all expenses had been paid there was a profit of £800.

The same day (9 June) the Yugoslav Government signed an agreement accepting the Allies’ requirements for the withdrawal of Yugoslav troops and administration east of the Morgan Line by 10 a.m. on the 12th. Some 2000 Yugoslavs were to remain in the territory under Allied control.

The Yugoslavs did not go empty-handed: they stripped machinery and accessories from garages, and emptied some barracks, hotels and houses of their contents; the amount of loot seemed to be limited only by the paucity of transport. By the morning of 11 June 16,000 troops on foot, 400 vehicles, 28 guns and over 1000 horses were seen straggling along the roads from Trieste to Fiume; the roads east of the Isonzo River also carried much horse-drawn, motor and foot traffic. The retreating Yugoslavs appeared to be ‘angry and humiliated’.51 The exodus continued throughout the next night, and by the morning of the 12th jubilant crowds were shouting ‘Viva Trieste’ in the streets of the city. The Allied Military Government assumed control and began distributing supplies the same day. The shortage of food had become critical.

Obviously to impede the AMG administration and discredit Allied efficiency, the Difesa Popolare and organised bands, including Yugoslav troops in civilian clothes, conducted a campaign of intimidation. Italian flags were forcibly removed, people visiting the AMG offices were molested, members of the new police force (volunteers in civilian clothes with armbands) had to be accompanied by military police for their own protection, and the Guardia del Popolo (an arm of the Difesa Popolare), although ordered to cease its activities, made many arrests. Demonstrators acclaimed communism and advocated local control – without directly challenging the assumption of Allied control. About 25,000 attended such a demonstration in Trieste on 15 June.

Meanwhile the New Zealand, British and Indian troops followed up the Yugoslav forces withdrawing to the Morgan Line. In 5 NZ Brigade’s sector 28 Battalion occupied Villa Opicina on 12 June, but 21 Battalion did not secure the wireless station near Barcola until the departure two days later of a detachment of Difesa Popolare. On the Muggia peninsula south of Trieste 23 Battalion was involved in a dispute with the Yugoslavs about the exact location of the Morgan Line. The Yugoslavs set up road blocks behind some of the New Zealand positions and temporarily severed their communications, but a few days later adjustments were made by both sides, and 23 Battalion kept road blocks where the Morgan Line crossed Route 15 and other roads.

Ninth Brigade found the Yugoslavs reluctant to go from the sector east of Trieste. A Yugoslav brigade 1500 strong did not leave Basovizza, on Route 14, until the evening of 13 June, and a battalion lingered until the 15th at San Dorligo, south of the highway. The civilians in this region were obviously sympathetic towards the Yugoslav Army. In some villages the New Zealanders were aware of an atmosphere of hostility.

(iii)

Because the establishment of Allied Military Government in the Anglo-American sector of Venezia Giulia and the return to a normal way of life for the civilian population were being impeded by the activities of the Difesa Popolare, it was decided to disarm and disband this force. Its members were to be called upon to parade and hand in their arms on 24 June; or if they preferred, they were to be escorted to the east of the Morgan Line with their arms. If the parades were not well attended, 13 Corps would order the cordoning of the barracks and billets of the Difesa Popolare while the police, assisted by troops if necessary, went in and arrested all

the men, who were to be taken to a camp east of the Isonzo River.

At the specified time, 2 p.m., 1435 members of the Difesa Popolare paraded at the Trieste infantry barracks in an orderly manner and with their own band. Fifty-five of them chose to be taken to the Yugoslav side of the Morgan Line, and 620 volunteered for the new police force under AMG control; the remainder were allowed to go home next morning, when 6 Brigade had taken over the barracks and posts which the Difesa Popolare had held. About 20 truckloads of arms and ammunition were collected.

The Difesa Popolare co-operated elsewhere in the Division’s sector: men paraded as requested and weapons and ammunition were collected. Altogether some 2280 members of the organisation paraded for 13 Corps, and of these 792 volunteered for police duty and 97 chose to be escorted across the line. No resistance was offered, and the whole procedure was conducted without incident.

A strike on 25 June, evidently instigated by the communists as a protest against disarming the Difesa Popolare, affected Trieste’s trams, buses, shipbuilders, shops, post offices and dock workers. Fourth Armoured Brigade supplied working parties to assist with the operating of the public services and the docks. Next day, however, the city returned to normal. Apparently the majority of those who had taken part in the strike had done so because of the fear of reprisals.

The Yugoslav News Agency claimed in a press report on 27 June that the Trieste trade unions had sent cables to the British, Russian, French, and Italian trade union organisations protesting that the British and American military government was confiscating and requisitioning trade union property. The New Zealanders were said to have searched the Slovene Home of Culture in Trieste and made arrests.

These allegations prompted the New Zealand Government to ask General Freyberg for the facts and his comments, and also to inquire about the operational employment of the Division and the immediate prospects. In his reply, despatched on 3 July, the General said that the incident of the trade union cables appeared to be part of a general Yugoslav press and radio campaign to discredit the Allied Military Government in the occupation zone of Venezia Giulia. He gave an account of the disbandment of the Difesa Popolare, and said that the ‘so-called Slovene Home of Culture was, in fact, the former Italian Fascist headquarters in Trieste and is now in use as Allied Military Government offices. It was one of the buildings searched without incident by the Allied military police on 24 June.’

‘In these difficult and often aggravating circumstances the conduct of the New Zealand troops was at all times exemplary.’52

The General also advised the Government that the situation in Trieste and Venezia Giulia had improved. The Yugoslav forces had moved out of the immediate Trieste-Gorizia area and the original line of communication had been made safe for the Allied forces occupying Austria. ‘I consider that we could now be relieved from our present operational role whenever our move is necessary. It is doubtful, however, if we will be relieved until the policy of the New Zealand Government as to future employment is finally announced. ...’53

(iv)

The Peace Treaty between Italy and the Allied and Associated Powers in 1947 provided for the creation of the Free Port of Trieste, ‘wherein all nations would enjoy freedom of transit and be exempt from customs charges’,54 but another seven years elapsed before the occupying powers were relieved of responsibility in Venezia Giulia. Trieste continued to be ‘a bone of contention in international politics’; it even proved impossible for the United Nations Security Council to agree upon a governor. ‘The Allied Powers and Italy long found themselves at odds on every issue with Yugoslavia, which was supported, until the deterioration of relations between the two communist powers, by the Soviet Union.’55 When it became clear that the original plan would not work, the United States and Britain sought unsuccessfully to obtain agreement for the return of the Free Territory to Italy. Finally, in 1954, Britain, the United States, Italy and Yugoslavia signed an agreement whereby the zone garrisoned by the Yugoslav troops and a small section of the Anglo-American zone were ceded to Yugoslavia, and the remainder of the Anglo-American zone, including the city of Trieste, was given to Italy.

It is conceivable that the destiny of Trieste might have been different had the New Zealand Division not arrived there – as Mr Churchill told Field Marshal Alexander – ‘in time to put your foot in the door.’ The occupation of all the territory east of the Isonzo River, which no doubt his forces could have accomplished, would have strengthened Tito’s hand, especially if supported by Russia, when the time came for the settlement at the peace table.

IV: The Division Retires

(i)

The New Zealand Division continued to perform garrison duties in Venezia Giulia until late in July. Fifth Brigade took over from 6 Brigade on the 7th the responsibility for the vital points in Trieste, where 21 Battalion provided guards and pickets until relieved by 28 Battalion a week later. Sixth Brigade concentrated north-east of the city, with its battalions astride the roads between Villa Opicina and Basovizza. Ninth Brigade was still covering Route 14 east of the city, and 23 Battalion was in the Muggia area to the south; other troops, including artillery and armour, were in the vicinity of Villa Opicina or farther to the north-west.

The behaviour of New Zealanders in Trieste and Villa Opicina caused concern. As a disciplinary measure all leave was cancelled in 21 Battalion for almost a week; all social activities were suspended, and every man was to perform a minimum of eight hours’ work or duty each day. Similar measures were adopted in 28 Battalion. Lieutenant-Colonel Henare56 spoke to his men after a church parade on the subject of bad behaviour, and emphasized that reports of incidents between New Zealand troops and civilians were being broadcast by the Yugoslav radio. Wharf and guard duties in Trieste, controlling check posts on roads, sport and social activities were ‘not enough to keep the Maoris busy and the adage about Satan finding mischief for idle hands to do was countered to some extent by putting all vino bars out of bounds, restricting leave for all junior officers, and by the institution of a tough training programme.’57

One group of New Zealanders was kept very busy until the middle of the month: the NZASC transport worked the docks on a 24-hour schedule with all the vehicles available. Twelve platoons were employed at the one time, and altogether they carried 60,000 tons.

Meanwhile 9 Brigade settled down in its sector ‘to a life of comparative indolence’,58 its only operational duties being the maintenance of three road blocks, the manning of which was taken over by 27 Battalion from Divisional Cavalry. Night after night telephone lines were cut deliberately, but despite vigilant patrolling, the offenders were not apprehended. Similar but less determined line-cutting was reported by 23 Battalion in the Muggia sector.

On the whole these last few weeks were peaceful and pleasant,

especially for the troops in the hills above Trieste, where the hot weather caused little discomfort. Men went on short sightseeing tours in Austria and northern Italy, stayed at rest camps, an alpine leave centre at Madonna di Campiglio in the southern Dolomites, or at the Forces Club in Venice. They participated in a wide range of sport – cricket, athletics, swimming, water polo, rowing, yachting, tennis and boxing. Divisional athletic and swimming championships and a rowing regatta were held. New Zealanders won all 12 events at a 13 Corps track and field meeting in Trieste, and eight of 13 events at an Eighth Army meeting at Udine.

‘TRIESTE is as good almost as a dream, no one will mind remaining,’ wrote a unit diarist. ‘We have swimming, good company in our comrades and many beautiful women. Leave is not greatly sought after as TRIESTE is so very handy with its many iced drinks, opera, pictures and trotting race meetings. ... Weather almost monotonously pleasant. ...’59 On the other hand, the period the Division spent in Venezia Giulia was marred by the highest incidence of venereal disease in its history, and by the number of men killed and injured and vehicles damaged in road accidents.60

(ii)

General Freyberg had advised Field Marshal Alexander on 6 May that the redeployment of New Zealand forces in the Pacific was under consideration by the New Zealand Government. He understood that the Division was not to take part in any garrison duties in Europe, and therefore suggested that it should give up its garrison role in Venezia Giulia and withdraw to an area from which the long-service men could be sent home.

Alexander had indicated that the Division would be released in the second half of June, and it had been assumed for the purpose of planning – including the provision of shipping for the repatriation of long-service men – that the Division might leave Venezia Giulia about 20 June. This assumption, however, was wrong. A month later, after the New Zealand Government had expressed concern to the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs about the delay, orders were received for the Division’s relief by 56 Division and withdrawal to central Italy, in the vicinity of Lake Trasimene. Its departure coincided with the redesignation (on 29 July) of

Headquarters Eighth Army as Headquarters British Troops in Austria. The New Zealand Division was the only original formation of Eighth Army still with it when it ceased to exist.61

Flattering farewell messages were published by the Italian newspaper La Voce Libera when the Division left Trieste. One concluded: ‘Goodbye, our New Zealand brothers, we are fond of you and you know it, but – perhaps because we are so fond of you – we are pleased that you are leaving us to return to your healthy country and that you are going away from this old and sick place which is called Europe, and which, if you had to stay here, would infect you all with its evil. How it has corrupted us all, we Europeans!’62

Not a few New Zealanders were sorry to go. ‘It was with genuine regret on all sides that the departure was made. Many close friendships had been formed and the hospitality and good times enjoyed here will undoubtedly be one of the pleasantest memories of ITALY.’63

The first formation to move, 9 Brigade, set off on 22 July on the 400-mile journey. From the Basovizza area its 370-odd vehicles (not including the carriers, which went by rail) passed through Trieste and along Route 14 to Mestre, the first staging area. During the next three days the brigade motored along Route 11 to Padua and Routes 16 and 64 to the next staging area near Bologna, where the troops were given leave; then along Route 9 across the familiar Romagna plain to Rimini, by Route 16 down the coast and Route 76 inland to the Fabriano staging area, and along Route 3 to Foligno and the destination near Perugia. The other formations, the last leaving on 31 July, followed the same route and stopped overnight at the same places.

Before leaving for central Italy 4 Armoured Brigade and 28 Assault Squadron despatched most of their tracked vehicles and scout cars to Udine; 74 Sherman tanks, 13 Stuart tanks, 15 Humber scout cars and three armoured recovery vehicles were retained for training the armoured regiment of a force which might be formed to serve in South-East Asia or the Pacific. A rear party, comprising 20 Armoured Regiment and men of 18 and 19 Regiments, 28 Assault Squadron, the brigade workshops and other detachments, spent a month in barracks at Villa Opicina awaiting instructions for the disposal or movement of these vehicles. During the last week of August the tanks were transported by rail to Bologna. The rear

party left Trieste on the 31st, reached Bologna next day and, after disposing of the tanks (but still retaining the scout cars), rejoined 4 Brigade on 7 September.

(iii)

The war against Japan ended abruptly. On 6 August an American B-29 bomber dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima; two days later the USSR declared war on Japan; on the 9th the Americans released an atomic bomb on Nagasaki; on the 14th Japan accepted the Allied terms of unconditional surrender, and next day all hostilities ceased.

This sudden and bewildering plunge into the atomic age, with the introduction of a weapon capable of incalculable destruction and harm to mankind, has dominated politics, military planning and international relations ever since. But in August 1945 the consequences of these momentous events were scarcely uppermost in the minds of the troops in Italy; they were glad that the war had finished in the Pacific as well as in Europe, and they thought about going home.

The Division spent two months in the vicinity of Lake Trasimene. Divisional Headquarters was at Villa Pischiella, on the northern side of the lake, the engineers and army service corps on the eastern side, 6 Brigade and the medical units on the southern side, 5 Brigade and the artillery on the western side, 9 Brigade just east of Perugia, and 4 Brigade about midway between Perugia and Assisi. The countryside was dry and dusty and in places bare and shadeless; the troops found much to complain about: ‘As hot as hades and no shade. ... Place alive with millions of insects. ... Men very restless with heat and insects.’64 ‘There has been no rain in the area for 5 months. ... altogether the men were rather “browned off” as they can see no apparent reason for putting the Division in such an isolated and waterless area. The consumption of wine will no doubt increase as other recreations are lacking.’65

Because the local population’s supply was very meagre, the troops were warned not to draw water which might be needed by civilians, and because of the risk of typhoid they were not to use any source which had not been approved by a medical officer. The engineers tried to improve the supply by experimenting with the filtering of lake water and excavating a ground reservoir into which water seeped from the lake, but this ‘turned out not so good’.66 It was necessary, therefore, to transport 18,000 gallons daily from Foligno.