Chapter 5: Three Island Actions

I: Vella Lavella

IMPENDING operations were discussed by Barrowclough on 10 September with Rear-Admiral T. S. Wilkinson, commander of Task Force 31,1 the naval organisation responsible for getting all units ashore in amphibious operations and their protection en route, and Major-General Barrett,2 commander of the First Marine Amphibious Corps, at their headquarters on Guadalcanal, and at the same time tactfully ended their tendency to plan forward moves without consulting him about his own formations. The following day he flew to Munda to confer with Major-General O. W. Griswold, 14 US Corps Commander, whose troops, exhausted by three island operations, were to be relieved on Vella Lavella. Potter and Brooke accompanied him and continued the journey to Vella, remaining there until the force came forward. Meanwhile, valuable information was being gathered by a party from 14 Brigade consisting of Lieutenant D. G. Graham, Sergeants H. B. Brereton, L. V. Stenhouse and M. McRae,3 who had gone forward on 28 August with Major C. W. H. Tripp and Captain D. E. Williams,4 of the South Pacific Scouts (Fijian), to work with patrols in Japanese-held territory until the brigade took over from the Americans, after which the Fijian scouts were withdrawn and returned to Guadalcanal. Twenty-one officers representing all units of 14 Brigade, who moved north via Munda on 13 September as an advanced party to select bivouac areas, had their first practice in evasive tactics when their open craft was attacked by enemy dive-bombers off

Maravari Beach two days later. Barrowclough went north on 17 September, travelling by air to Munda and completing the journey late that night by motor torpedo boat from Rendova, the operational base for those craft, which have a speed of 40 knots. Duff, the CRA, Burns of Signals, and Bennett, AA and QMG, accompanied him and all were on the beach the following morning to meet the landing craft.

As the division moved on to Guadalcanal in September, formations of Griswold's 14 Corps were driving the last of the Japanese from Arundel and Vaaga Islands and sites along the north coast of New Georgia, forcing them to retreat to Kolombangara, a few miles north. Munda airfield, finally secured after protracted and stub-born fighting two days less than a year after the landing on Guadalcanal, was in operation, though subject to nightly bombing raids. Plans to attack Kolombangara were discarded by the South Pacific Command on 12 July in favour of by-passing that island and landing on the more lightly held Vella Lavella, where suitable territory existed behind Barakoma Beach for the construction of an airfield to aid in the next thrust forward. This had been surveyed by a party of American specialists, who landed under cover of darkness and spent several days there before being taken off again. An American force 4600 strong, consisting of 35 Infantry Regiment, 4 Marine Defence Battalion, and one battalion of 145 Infantry Regiment (a later reinforcement) landed on Vella on 15 August and drove the Japanese garrison into the north of the island, where they were holding out and awaiting relief along the coastal region between Paraso Bay and Mundi Mundi. An American engineer construction battalion, the 58th, known as CBs (units for which the New Zealanders developed profound admiration) immediately began clearing a swampy area of jungle for the airfield, and a naval base had been established at Biloa, on the southern tip of the island, where the only remaining evidence of a former mission station consisted of pieces of concrete foundations and a few flowering shrubs. A motor torpedo boat base was operating from an unsatisfactory site off Laipari Island, opposite Biloa. Night-raiding aircraft hindered the construction of the airfield, and attempted to destroy petrol dumps and the torpedo boats which were harrying Japanese barge traffic at night round Kolombangara and smaller islands. Sites at Kimbolia for a radar station and at Lambu Lambu for a more effective motor torpedo boat base were urgently required on the northern coast to assist in the next operations—the capture of the Treasury Group and a beach-head on Bougainville—and for this reason Vella Lavella was to be made secure.

The main Japanese force had been established in this region in defensive positions at Horoniu and Boko, but had been driven out by the Americans on 14 September. It consisted of remnants of several units, including 290 army and 100 navy personnel, who landed at Horoniu on the morning of 19 August after eluding an action in which their covering destroyers were attacked by an American naval force in Vella Gulf on the night of 17 August (two days after the American landing farther south) and approximately 190 army and 120 navy survivors from naval engagements on the night of 6–7 August, when three Japanese destroyers were sunk in almost as many minutes. These were joined by others from observation posts and staging barge bases on the island, and scattered survivors from barges sunk on 25 September, but there was no co-ordinated command as an officer detailed to take charge of the Japanese garrison never arrived. When the main position at Horoniu was overwhelmed they scattered to the north. Patrols of Fijian scouts, accompanied by 14 Brigade non-commissioned officers, had been through the northern region observing the Japanese but with orders not to attack them. Estimates of enemy strength ranged from 500 to 700, established in small groups at Timbala Bay, their radio station and lookout post, Warambari Bay, Tambama and Varuasi, and armed with mortars, machine guns, rifles, and grenades. These patrols received valuable assistance and information from a coastwatcher, Lieutenant H. E. Josselyn, RANVR, who had been hidden on the island for several weeks.

Approximately 3700 troops of the division, principally 14 Brigade units and elements of headquarters, disembarked on the beaches soon after dawn on 18 September. After loading and practising disembarkation for two days at Kukum and Kokumbona beaches, they travelled north in a convoy of six APDs, six LSTs, and six LCIs, escorted by eleven destroyers. During the brief voyage troops voted in the New Zealand Parliamentary elections and watched from blacked-out ships the fiery spectacle of a Japanese air raid on Munda.

With only a limited time in which to clear the ships, disembarkation began with speed at Barakoma, Maravari, and Uzamba beaches as Japanese lookouts on Kolombangara, only thirteen miles across the water, could observe the landing. High overhead in the clear sunshine an umbrella of aircraft circled in anticipation of attack as men and ships went ashore to a disciplined schedule. As the ramps of the massive LSTs clattered down, trucks, bulldozers, and guns rolled out and bumped into the jungle and mud. Bulldozers tore down palms and trees, gathering them into their shining blades to form causeways to the ramps of the heavier craft which remained

in water too deep for vehicles to negotiate. Waist deep in the water, men passed crated stores and equipment from ship to shore, stacking them out of sight among the trees. Petrol, oil, and ammunition also disappeared into the jungle, which grew almost to the water's edge. The APDs, lying in deeper water, were cleared in half an hour. By noon the Japanese air attack developed, but by that time the valuable landing craft, which were never over plentiful, lay far from the shore, herded together by the destroyers in readiness for the return journey. Seven of the Japanese aircraft were brought down in a dogfight which ended as quickly as it began, but no damage was done to troops or equipment.

Divisional Headquarters was established in tents deep in the jungle behind Barakoma Beach, and over the primitive road which gave access to this gloomy site trucks pushed heavily laden jeeps

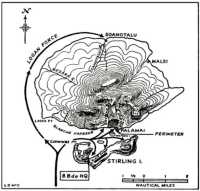

The heavily wooded island of Vella Lavella, scene of 3 division's first action in the Solomons. Flat-bottomed landing craft carried units of 14 Brigade from bay to bay round the coast.

out of the evil-smelling mud all day long. Fourteenth Brigade moved farther up the coast and opened its headquarters on high ground overlooking the deserted native village of Joroveto in the less enclosed spaces of Gill's Plantation, with the 35 and 37 Battalions and brigade units spaced on either side between the Joroveto and Mumia Rivers, and all concealed without difficulty from the air. The only access to the plantation area was a rough track, feet deep in mud, which skirted the coast among the trees, but by sundown most of the essential equipment had been transported over it. When night came down bivouacs had been erected, foxholes constructed or shelters made among the spreading roots of the trees, where the men lived on packeted C and K rations until routine was established. Air raids gave them little sleep that night, or for long afterwards.

Except for a few coconut plantations on the more level areas, Vella Lavella is clothed with dense jungle from high-water mark to the crests of mountains in the interior. Visibility ends only a few yards away in a barrier made up of fleshy leaves, vines and creepers, shrubs and tree trunks, as this mass of vegetation fights upwards to the sun. Large trees, whose massive boles sprawl out like flying buttresses several feet above the ground, are matted together with vines and a variety of barbed climbing palm to form an impenetrable canopy overhead. The earth is never dry and never free from the heavy odour of decay. Mildew grows overnight on anything damp. Growth is so swift that a rain of leaves falls in a gentle whisper. By day the jungle is comparatively quiet, except for the chatter of parrots and parakeets and the harsh shrill of myriads of cicadas, which begin and end their crude orchestra as abruptly as though working to a signal. One moment the air is vibrating with the din of a sawmill; the next all is silent. Brilliant butterflies with inches of wingspread hover among the vegetation; grotesque spiders swing their huge webs among palms and trees, and lizards, large and small, rustle among the carpet of dead leaves.

When night falls, swiftly with the setting sun, the jungle comes to life and bedlam reigns until dawn. Millions of small frogs croak and whistle, night birds screech and chatter, and cicadas join sudden bursts of sound to this disturbing clamour. Fireflies flicker like showers of sparks in the velvet gloom, and in the phosphorescent light from the chips of one tree a newspaper may be read with ease. Among the dead and fallen leaves every creeping and crawling thing finds a home—ants by the million, millipedes, slugs, crabs and lizards, including the iguana. To this exotic land thunder-storms of great violence, coming almost daily, bring torrents of

rain, adding to the discomfort and depression born of a sense of imprisonment in the perpetual half-light. The only open spaces were in the coconut plantations, though these had become dense thickets where fallen nuts had taken root and grown during the war years.

That was the setting for 14 Brigade's first action and, with few exceptions, a background for all action in the Solomons. The most spectacular part of jungle fighting is the jungle itself and the beach landings. The more common conceptions of warfare, with bursting shells, tanks, guns, and men in violent action on a vast battlefield have no place here; nature dwarfs and conceals them all.

Barrowclough took over command of Vella Lavella and all American units on 18 September and became commanding general of these composite formations, New Zealand and American, grouped by 14 Corps under the title of the Northern Landing Force. From that day all island administration—supplies, transport, signals, medical and engineering—passed to the corresponding branches of 3 Division Headquarters. Operational instructions to 14 Brigade to relieve American combat troops and clear the island of Japanese were issued the following day. Potter's plan for these operations, timed to begin on 21 September, entailed the use of two of his combat teams, built round Seaward's5 35 Battalion and Sugden's 37th. The 30th Battalion, command of which passed to Lieutenant-Colonel F. C. Cornwall, MC,6 when McNamara was evacuated sick, before leaving Guadalcanal, was held in reserve in the south of the island, where it arrived on 24 September as the other teams moved to their assembly points in the north.

The brigade commander planned a pincer movement employing Seaward's 35 Battalion combat team on the left flank and Sugden's 37th team on the right, designed to drive the enemy garrison into a trap when the two battalions met in the extreme north of the island. His teams consisted of the following units:

35 Battalion:

12 Field Battery (Maj L. J. Fahey)

C Troop, 207 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery (Lt J. C. Hutchison)

C Troop, 53 Anti-Tank Battery (Lt D. Taylor)

Detachment of 20 Field Company Engineers (2 Lt A. R. I. Garry)

Detachment of 16 MT Company ASC (Capt T. P. Revell)

A Company, 22 Field Ambulance (Capt D. G. Simpson)

2 Platoon, 14 Brigade MMG Company (Lt R. B. Lockett)

K Section Signals (Lt E. G. Harris)

35 Battalion:

35 Field Battery (Maj A. G. Coulam)

A Troop, 207 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery (Lt O. W. MacDonald)

A Troop, 53 Anti-Tank Battery (Lt C. E. G. Kerr)

Detachment of 20 Field Company Engineers (Lt R. W. Syme)

Detachment of 16 MT Company ASC (Capt J. F. B. Wilson)

Headquarters Company, 22 Field Ambulance (Capt B. W. Clouston)

3 Platoon, 14 Brigade MMG Company (Lt K. A. Wills)

E Section Signals (Lt L. C. Stewart)

Potter planned to complete the task in fourteen days; but it took only ten. After establishing advanced bases, battalion commanders were instructed to move from bay to bay in bounds, first clearing selected areas by overland patrols before bringing their main forces forward by small landing craft after beach-heads were secure. Eight such craft were allotted to each combat team, but breakdowns kept the 37th so short that at one stage it was reduced to two and borrowed replacements from the 35th pool. Supplies were maintained from Maravari, the main base, by a daily barge service to each team's headquarters as it moved forward. Dress for action was drill jungle suits with soft linen hats and waterproof capes or groundsheets, and individual equipment was made lighter by discarding steel helmets (except for anti-aircraft teams) and gas respirators. This was in accordance with Barrowclough's earlier instruction that assault troops were to go into action as lightly equipped as possible. The men carried their packaged jungle rations, atebrin tablets, mosquito repellent lotion, and water chlorinating tablets. In addition to full water bottles, a two-gallon tin of fresh water was carried for every five men.

Combat teams, which fought as self-contained units, began moving round the coast from Maravari Beach on 21 September and were established in forward areas four days later—35 Battalion at Matu Soroto because of the unsuitability of Mundi Mundi, and 37 Battalion at Boro, on Doveli Cove, after picking up a stray prisoner at Paraso Bay, which was also abandoned as a forward operational base. Once established ashore patrols fanned out like the extended fingers of a hand through dense jungle and swampy mangrove and banyan thickets, searching every yard of ground to a depth of 2000 yards inland. Progress was slow, never more than a few hundred yards a day along the narrow coastal belt, which in places was only one hundred yards wide before it rose abruptly in heavily timbered mountain slopes. Rivers and streams impeded the patrols and their native guides, who moved along the narrow tracks in single file as they paved the way for the advance.

Any use of tanks was out of the question. Field guns were dragged ashore by manpower under the most exhausting conditions. Beachheads were dictated by openings through the coral reef, some of them so shallow they prevented the passage of landing craft, and others non-existent on inaccurate maps. Conditions from the day active operations began on 25 September were harsh and difficult. Rain fell in torrents, soaking the men, hampering movement, and turning the dank jungle into a bog. Despite correct information that the Japanese were poorly armed and led, their cunningly concealed machine-gun nests and pockets of resistance sited among splaying roots and fallen logs were eradicated only with difficulty, as were snipers often hidden among the leafy branches overhead, for in the jungle the advantage is always with the defender. Hand grenades bounced off trunks and vines unless thrown with extreme care. At night patrols withdrew and formed perimeters, from which no man moved out of the cross-shaped foxholes, each containing four men, until dawn.

For the first few days action resolved itself into individual skirmishes, in which small resolute groups proved their ability to meet and defeat an equally resolute enemy camouflaged against a mottled wall of green and brown and occasional blobs of light. There was no definite lane of advance, as in open country. Patrols, thrown on their own initiative, fought individual actions among the enclosing growth, sometimes without seeing their adversaries. This was characteristic of the whole operation. By 27 September 35 Battalion patrols, which encountered the enemy much sooner than the 37th, had advanced through Pakoi Bay and stubbornly fought their way overland to the heavily timbered country round Timbala Bay, beyond which the main Japanese garrison was concentrating as it fell back from both flanks.

On 26 September a strong patrol, consisting of 14 Platoon under Lieutenant J. S. Albon,7 and the carrier platoon, working as infantry and led by Lieutenant J. W. Beaumont,8 was despatched to block trails leading into Marquana Bay and the interior, with instructions to await the arrival of the main force, but both platoons were ambushed and lost to the battalion for six days. A, B, and C Companies were established at the head of Timbala on the morning of 27 September, in readiness for an attack the following morning when, after an artillery concentration, they moved forward slowly, C on the left with its left flank on the coast, B in the middle, and

A on the right. Platoons led by Lieutenant R. Sinclair9 and Lieutenant W. J. McNeight10 took the brunt of the fighting.

Meanwhile, two platoons under Major K. Haslett11 were sent forward to contact the force blocking the inland tracks, but when nearing Marquana Bay they ran against opposition, only 100 yards from where the force they were seeking had been ambushed, yet such was the density of the jungle they were unaware of it. Haslett returned after avoiding an ambush of his own force. Torrential rain fell all this time, disrupting communications. Wireless was useless under the tall trees and land lines broke continuously. Foxholes became beds of slime which the men shared each night with crabs and crawling insects.

By 29 September it was obvious that the battalion had come up against the main Japanese force contained in the narrow neck of land dividing Timbala Bay from Marquana Bay, and it was ordered not to make any large-scale attack but to await the arrival of 37 Battalion which, hindered by a shortage of landing craft, was covering longer distances along the deeply indented right flank. A Company was held up in Machine-gun Gully, the strongest point of resistance, and ordered to form a perimeter for the night with B and C Companies. That night, also, Private D. W. T. Evans12 reached headquarters with information that the two platoons sent out on 26 September had been ambushed, but it was vague and useless. Private W. F. A. Bickley,13 who had also escaped, was picked up the following day but he was equally vague. Next day Umomo Island, a wooded dot 40 yards off the northern end of Timbala Bay, was occupied by patrols and used as a site for enfilading enemy positions along the coast. B Company continued the move down the left flank of Machine-gun Gully while A Company took the right, both calling for artillery support when their patrols were held up.

Throughout two dreary days patrols felt their way through the jungle, clearing the fully, and the two ambushed platoons rejoined the battalion. They had fought a gallant action and, as it so happened, contained a considerable enemy force deep in the jungle while the two battalions drove the Japanese in from the flanks. Not till they returned was their story known. Night fell before they reached their objective on 26 September, but they pressed on the next morning and were within reach of the main track when

a native guide reported forty Japanese moving along it to the coast. Beaumont took two sections forward to reconnoitre the position and cover the track, which he crossed to give his machine guns a better site. This was completed by 11.30 a. m., after which small parties of Japanese were observed moving towards Marquana Bay, followed by 96 others, all well armed.

Because the parties were separated, Beaumont thought it unwise to attack. Two hours later, when this enemy traffic ceased, Beaumont began to move back to the main party, but as he did so bursts of machine-gun fire shattered the silence. A few seconds later the main party under Albon, which was surprised while having a meal, rushed along the track and passed through Beaumont's men, under whose fire the Japanese melted into the jungle. Beaumont took command and formed a rough perimeter with his own platoon at one end and Albon's at the other. He instructed the men to hold fire until they saw a target. Scurrying from tree to tree the Japanese attacked, sometimes shouting in English as they hurled grenades. Again and again the New Zealanders held off the attackers until night fell, by which time three of the garrison had been killed and four wounded, including Signaller R. J. Park,14 when a burst of machine-gun fire wrecked the wireless set on which he was attempting to communicate with headquarters.

The little force was short of food, water, and equipment, most of which had been abandoned by Albon's party when the Japanese attacked them, and completely out of touch with the main force. What little food remained was rationed among the men; rain-water was trapped in capes and groundsheets. For three more days repeated Japanese attacks were held off with determination. Although morale was high, the men were growing weak for want of food. Albon spoke to Beaumont on 29 September of attempting to reach headquarters to bring help. He slipped away the following morning, taking two men with him, but when he reached headquarters his information was too vague to be of use. That morning Corporal R. G. Waldman,15 with three men, attempted to reach the abandoned rations but was driven back into the perimeter.

On the fifth day under that dense jungle canopy, Beaumont decided to fight his way out to the beach. The wounded were suffering acutely from exposure and lack of attention. After burying the dead, he cut poles with which to make stretchers for the wounded, lashing them with vines and branches, but they were discarded as too unwieldy. Beaumont's small force then set off

at ten o'clock on the morning of 1 October. Private R. J. Fitzgerald16 led the wounded, himself one of them. Beaumont and six men covered the party as it crept through the jungle. Four and a half hours later they reached the beach, only 1000 yards away, but 49 men, including all the wounded, had been saved. A passing barge sighted Beaumont and his men inside their beach perimeter late that afternoon and advised headquarters, which immediately despatched a reconnaissance party in a landing craft with the object of making an overland advance to relieve them. When the craft moved in towards the shore Private R. Davis17 swam out to it, though fired on by machine guns from either flank of the perimeter. Private C. T. J. Beckham18 crept through the undergrowth at dusk and destroyed one of them. That night, after immediate rescue was abandoned, the hungry garrison retrieved a bag of Japanese rations dropped by parachute, killing the enemy who were searching for it.

Next day, 2 October, two barge parties, the first under 2 Lieutenant C. D. Griffiths,19 and another, which arrived later, under Lieutenant D. G. Graham, moved in as far as the coral growth would allow and men attempted to swim ashore with rations. Sharks were held off with tommy guns. Japanese snipers killed Lieutenant M. M. Ormsby20 in the water and wounded an American sailor, D. H. Stevens. Sergeant W. Q. McGhie21 reached the shore but lost food and medical supplies in the water. A second daylight attempt ended disastrously. Griffiths, Warrant Officer R. A. Roche, Private S. Hislop, Private W. M. Pratt,22 and Graham spaced themselves in the water and attempted to get a line ashore to Beaumont. It caught in the jagged coral with maddening consistency, hindering the swimmers. All were killed except Graham. Fitzgerald, who had endured the agony of the perimeter, was killed on the barge and the rescue was abandoned until nightfall. A party of strong swimmers, all volunteers, arrived from headquarters at Graham's request and, led by Corporal M. H. Cotterell,23 they swam ashore in the gathering dusk with a rubber boat and a native canoe. By eleven o'clock that night the last men

were transported to the waiting barges. Beaumont and his party had accounted for forty Japanese killed and an unknown number wounded. They themselves had lost six killed and eight wounded.

On the day of the rescue Major J. A. Burden, a Japanese interpreter from the American command, came forward with a proposal to distribute leaflets among the enemy informing them that they would be honourably treated if they surrendered, but nothing came of this. That day, also, 41 enemy planes attacked Matu Soroto but were driven off by Hutchison's guns, most of the bombs falling into the sea. By 3 October, after another artillery bombardment, A and B Companies finally cleared Machine-gun Gully, where most of the casualties occurred, and by nightfall were joined by C and D Companies. The battalion was then half way to Marquana Bay.

Meanwhile, away on the right flank, 37 Battalion had advanced to Tambana Bay against light opposition. Here a patrol led by Captain R. T. J. Adams24 captured a large Japanese barge which, well camouflaged with greenery, entered the lagoon and anchored off the beach among the mangroves. When the crew went ashore, one platoon boarded the barge and manned its several machine guns while, another, led by Lieutenant S. J. Bartos,25 hid in the undergrowth. Fourteen of the Japanese crew were killed when they attempted to return to their boat. The shore party located the remainder in a tangle of mangrove and banyan roots and destroyed them. The battalion named the barge Confident and used it as a transport after the removal of a valuable collection of papers and equipment. Next day the battalion began its next leap some miles forward to Varuasi and then pushed on to Susu Bay, after which it was instructed to concentrate in Warambari Bay by the evening of 4 October.

With landing craft borrowed from 35 Battalion's pool and ferried round the coast, 37 Battalion patrols landed on the south-west coast of Warambari Bay on the morning of 5 October against determined opposition. Lieutenant D. M. Shirley26 was pinned down between two machine-gun nests and snipers, but ultimately dealt with them. After a day of hard fighting, during which patrols killed twenty Japanese, the battalion established its beach-head and after an artillery bombardment next morning began another day of eradicating enemy posts. One patrol led by Lieutenant D. J. Law27 accounted for the first machine-gun opposition. He and his men did not rejoin their unit until the following day. Two of many

acts of bravery were recorded during those two days before Warambari was secured—the first when Private A. McCullough,28 although wounded in both hands and one leg, tossed one of their own grenades back among an enemy patrol before it exploded; the second when Corporal L. N. Dunlea29 and Lance-Corporal J. W. Barbour30 retrieved the body of Lieutenant O. Nicholls31 after he had been killed.

By nightfall on 6 October both battalions were in range of each other, with the Japanese trapped in a neck of land dividing Warambari Bay from Marquana Bay, towards which 35 Batallion had inched forward at 300 to 600 yards a day, finally losing contact with the enemy on 5 October. A prisoner taken that day stated that about 500 well organised troops were trapped. They were short of food, evidence of which were the broken coconuts found in deserted bivouacs, and wished to surrender, but were prevented from doing so by their officers. Potter, who had conducted the operation from advanced headquarters at Matu Soroto, decided to close the gap. Both the covering batteries were tied in on a common grid and came under regimental control.

By four o'clock on the afternoon of 6 October, 35 Battalion reached the coast of Marquana Bay, finding many dead Japanese and much abandoned equipment in their former bivouac area. The 37 the Battalion pushed through the jungle against opposition and by dusk and reached as far as Mende Point, narrowing the gap between the two combat teams. That night artillery and mortar concentrations were ordered over the are in which the Japanese were enclosed round Marziana Point, but because of low-flying aircraft they ceased early in the evening for fear of revealing their positions. This lack of aggression undoubtedly enabled the enemy to escape. The noise of barges scraping on the coral and the chatter of high-pitched voices could be heard by men lying in the sodden jungle, but the New Zealand guns and mortars remained silent. Next morning, after an artillery barrage, patrols from both battalions combed the area without opposition. The only event of importance that day was the rescue of seven American airmen from a raft which floated into Tambama Bay after their machine had been shot down At. 10.33 a. m. patrols from A Company of 35 Battalion joined 37 Battalion patrols from B Company at the Kazo River, but further search of the are revealed

only abandoned equipment and some dead. At 10 a. m. on 9 October Potter declared the completion of the brigade's task.

Casualties were not heavy and, despite appalling conditions, the sickness rate was low. The brigade lost three officers and 28 other ranks killed; one officer died of wounds, and one officer and 31 other ranks were wounded. Uncertain estimates of enemy killed ranged from 200 to 300, but the Japanese always attempted to hide their losses by burying their dead and removing the wounded. Their naval records, examined in Tokyo, revealed that on the night of 6–7 October, when aircraft silenced the brigade's artillery, 589 military and naval personnel were taken off the island from Maraziana Point, while destroyers sent to cover the operation were engaged by an American naval force north of the island. This operation, planned by 17 Japanese Army, included a transport force of three destroyers and a pick-up unit of five submarine-chasers and three motor torpedo boats to screen the barges transferring men from shore to ship. Six destroyers to protect this force left Rabaul on 6 October and were observed by American reconnaissance aircraft north of Buka Passage, causing the commander to death two of his destroyers to join the three transport destroyer at a rendezvous in Bougainville Strait before proceeding to Vella Lavella. Late the same afternoon the pick-up craft departed from Buin, on Bougainville, skirting the Treasury Group to pick up the destroyer screen. As the Japanese force entered waters north of Vella Lavella it was engaged by three American destroyers—Chevalier, Selfridge, and O'Bannon—which triumphed in a sharp and bitter engagement but only after being severely mauled. Selfridge had her bow sheared off, Chevalier was torpedoed and sunk, and O'Bannon damaged herself in a collision with Selfridge. A Japanese destroyer Yugomo and several small craft were sunk, but under cover of this engagement the pick-up force moved into Maraziana Point, embarked the garrison between 11.10 p. m. and 1.5 a. m. and departed for Buin, where it arrived safely. Three other American destroyers bringing a convoy from Guadalcanal to Vella Lavella were ordered to the scene of the engagement but arrived too late to take part. Next day 78 naval ratings from the Yugomo were rescued by naval patrols.

Units emerged from their first action with high morale but a healthy respect for a tenacious adversary. Men in action had not tasted hot food for almost a month, nor had a change of clothing been possible. Combat battalions lost one man killed for every man wounded, and all arms of the service, working as a team, overcame equipment problems, arduously tested by experience. There had been a tendency by commanders of combat teams to

establish separate combat headquarters, in addition to battalion headquarters, instead of absorbing the extra attached units into their battalions. This was frowned on by Barrowclough and did not happen again during the remainder of the division's service in the Solomons.

Jungle conditions made immense demands on both artillery and signals. Guns were barged from bay to bay and hauled ashore by manpower over coral and tree-roots to their selected sites on beach or headland, on one occasion taking three days to do so. Working through the night, trees and undergrowth were cleared to give arcs of fire. Ammunition was manpowered from barge to gun site. Ranging on enemy targets with accuracy was impeded by the blanket of forest, and air observations was practically useless as the smoke from ranging shells never rose above the trees. Again and again the observation officers, Captain P. M. Blundell32 and Captain R. E. Williams,33 went forward with infantry patrols to report where the shells fell, laying 25 to 50 yards from the bursts. With his remarkable sense of locality Sergeant T. J. Walsh,34 of 35 Battalion, also assisted by pin-pointing enemy machine-gun posts so that fire could be directed on them. This was the only answer to the use of artillery in the jungle.

Communication difficulties were not easily overcome. Seeping moisture, continual rain, and violent electrical storms played havoc with No. 11 and No. 12 wireless sets. Even the sets in use were not sufficiently strong to overcome the effect of the heavy mat of jungle overhead. Forward units were frequently out of touch with rear formations, particularly at night, when conditions, were at their worst. Field telephones were finally used in the forward areas and the more reliable runner when all else failed. During operations signals officers experimented with wireless aerials in trees and palms in an effort to overcome problems in such thickly wooded country. Wire-lying parties, transporting their heavy and noisy equipment through territory not cleared of Japanese, were protected by armed guards. Such was the state of country that on one occasion nine miles of wire were required between two points only three miles apart. A moisture-proof New Zealand-made wireless set, known as the ZC1, some of which came forward during operations, proved to be most suitable for jungle warfare. Finally, after most exhaustive work, a telephone circuit using seventy miles of wire was laid round most of the island, linking units, radar stations, motor torpedo boat bases, airfield and anti-aircraft defences.

Supplies during the operational period were maintained by 10 Motor Transport Company by breaking them down at Maravari and barging them round the coast to beach-heads, a journey of four to five hours, after which carrying parties took rations forward into the jungle. A field bakery detachment35 reached Vella Lavella on 9 October and, by the time the operations ended, fresh bread was delivered by landing craft to all units round the island every third day. Wounded and sick returned by the battalion supply barges to the field hospital established in Gill's Plantation, where any immediate surgical work was done by Major P. C. E. Brunette,36 1 Field Surgical Unit, after which the more serious cases were evacuated to Guadalcanal by air, the remainder travelling by boat.

While the combat teams cleared the jungle in the north, organisation and construction continued in the south. Barrowclough moved his headquarters to a less restricted and more congenial site among the palms of Gill's Plantation on 2 October, some of the trucks and jeeps taking six hours to bump their way over seven miles of mud and coconut logs of the only possible track. Regular flights of landing craft arrived from Guadalcanal, bringing forward remaining units and rear parties and immense quantities of stores, ammunition, petrol, and oil for a garrison which, by 25 October, reached 17,000 New Zealanders and Americans, these last including three battalions and ancillary units of the First Marine Amphibious Corps, a battalion of the United States Marine Corps, and operational staffs for the airfield, naval base, and motor torpedo boat base.

Two of the flights were caught on the beach by Japanese aircraft—the first on 25 September when seventeen Americans were killed, and another on 1 October when low-flying bombers came out of the sun and caught two landing craft while they were unloading.

Fifty-two men were killed and many wounded in this attack. The first bomb scored a direct hit on one of 209 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery's guns, killing Sergeant M. J. Healy,37 of M Troop, and fifteen of his detachment, and destroying the LST by fire. Another bomb failed to explode, and a third grazed the rail to explode in the water.

Once more the engineers, with increased but still limited heavy equipment, set about the primary task of transforming a rough jungle track into a two-way all-weather road from Biloa to the motor torpedo boat base at Lambu Lambu, halfway up the island, and linking all units and service installations and depots along the coast. The 26th Field Company, which became a heavy equipment company, was brought forward from Guadalcanal and shared this project with McKay's 20 Field Company. The road was finished in weeks, during which several substantial bridges were built using heavy timber from the neighbouring jungle and coconut logs for decking. Other roads were then constructed to water points and petrol dumps, known as ‘tank fields’. Two months after the division was established on Vella Lavella, speed restrictions were imposed on the main highway, the surface of which survived even the torrential rain.

Soon after fighting ceased, reconnaissance patrols were despatched to neighbouring islands on which stray Japanese might still be in hiding. Gizo Island was searched on 10 October by two platoons from 30 Battalion under Captain F. R. M Watson,38 and Ganongga Island on 19 October by a 4 Field Security patrol under Lieutenant D. Lawford,39 whose men had worked with 14 Brigade during operations and later assisted with the rescue of Beaumont's men from the beach. Both found evidence of former Japanese occupation, but the garrisons had been withdrawn on the night of 21 September. Natives reported that 67 dead Japanese had been washed ashore on Ganongga. A goodwill trip was also made to Simbo Island where, as on every island, the natives were given medical treatment by New Zealand medical officers.

A message from Griswold to Barrowclough at the conclusion of the Vella Lavella operations echoed in spirit others which came at the conclusion of each succeeding action from Halsey, Harmon, and senior American commanders in the Pacific. It ran:

Please convey to all elements of your excellent command my thanks and heartiest congratulations for the despatch with which enemy forces were driven from Vella Lavella. The prompt action of your division to make

secure the island's vital installations was accomplished with the smoothness and efficiency which mark a well-trained and determined organisation. Your own cordial co-operation and willingness to accommodate your requirements to limitations of transportation and other inconveniences which the situation required is fully appreciated. We have shown our readiness and ability to work together as Allies, and it is with the greatest confidence that I look forward to future operations with the Third New Zealand Division.

Although military operations were only of secondary importance, the conquest of Vella Lavella was a significant phase in the Solomons campaign. The island was secured at a cost of only 150 killed, New Zealanders and Americans, and the value of by-passing strategy conclusively proved. The airfield, construction of which began on 16 August, was in operation by 26 September and by 18 October in daily operational use by a squadron of Corsairs. A few days later sixty aircraft were using Barakoma. Moreover, 22 airmen had been saved either from the sea or by crash-landing on the partially constructed field. From the new motor torpedo boat base at Lambu Lambu powerful little craft emerged each night to hunt and disrupt enemy barge traffic round the Shortlands and Choiseul. Aircraft stationed at Barakoma joined those operating from Munda and Guadalcanal to pound enemy strongholds on and around Bougainville and Rabaul. Flights of 100 or more, droning north, became familiar sights. Thus the capture of Vella Lavella paved the way for the next thrust forward—the occupation of the Treasury Group, 73 miles away, and the landing on Bougainville.

II: The Treasuries

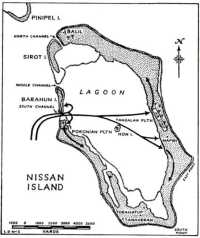

As 14 Brigade settled down to a period of routine duty after securing Vella Lavella, 8 Brigade embarked on the division's second task in the campaign—the capture of the Treasury Islands, a small group lying 300 miles north of Guadalcanal and only 18 miles from the Shortland Islands, where the Japanese were strongly entrenched round a series of airfields and naval bases covering their last defence system in the Solomons. The Treasury Group, consisting of Mono and Stirling Islands, with the deep, sheltered waters of Blanche Harbour dividing them, was urgently required to continue the by-passing strategy so successfully developed on Vella Lavella and to assist with a large-scale landing by Vandegrift's United States Marine Corps at Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville, the next thrust in the enveloping movement designed to reduce Rabaul and isolate the remaining Japanese garrison, estimated at 24,000, holding Bougainville and neighbouring islands to the south.

A radar station was an imperative accessory to the Bougainville landing to give warning of approaching enemy air and surface

craft, and a site for it was tentatively selected on the northern coast of Mono Island, a densely wooded cone seven miles by three, rising to a height of 1100 feet. Blanche Harbour, as beautiful as any in the Solomons, with tiny, palm-clad islands breaking its surface, fulfilled all requirements as a staging base for naval and barge traffic; and on flat, irregularly shaped Stirling Island, three and a half miles long by anything from 300 to 1500 yards wide, there was an excellent site for an airfield after the removal of its covering of dense forest.

Tactical and supply considerations and the adequacy of air support from existing airfields dictated the landings on both the Treasury Islands and Empress Augusts Bay, and then only after the alternatives of Choiseul, Kahili, and the Shortland Islands had been abandoned because they were too strongly defended. An assault on those two objectives was also considered the best possible method of meeting the Joint Chiefs of Staff directives concerning the Solomons offensive and the subjection of Rabaul, but they were selected only after long discussions by the planning staffs of both MacArthur's and Halsey's headquarters. Most of the information which assisted the planners in arriving at their decision was obtained from reconnaissance parties, which went ashore at night from submarines and landing craft and spent days hiding in the jungle, interrogating natives and observing Japanese defences and movement of garrisons.

Barrowclough was informed of this task on 20 September, when he discussed with Wilkinson various phases of the campaign, following his arrival on Guadalcanal. He allotted it to 8 Brigade, since 14 Brigade was already committed to Vella Lavella, to which it had departed three days after the arrival of 8 Brigade. From the time of its arrival on Guadalcanal, 8 Brigade lost no time in practising with fervour all phases of jungle warfare through the wooded gullies of the Matanikau River and over the grassy ridges radiating from the slopes of Mount Austen—country which had been most bitterly contested by the Japanese in the battle for Guadalcanal. Typical of this thorough training was the despatch of small groups to spend the night bivouacking in the jungle to make themselves familiar with the fantasy of noises and unusual conditions. Combined manoeuvres were also held with the Tank Squadron, then camped on the banks of the Lunga River. Tanks were allotted to battalions for field days—Troops one and four with 29 Battalion, two and five with 34 Battalion, and three with 36 Battalion. Although they never worked in combat with 8 Brigade, the exacting experience gained from these exercises was

invaluable in the jungle on Green Island, where the tanks later worked with 14 Brigade.

There was one diversion from training which was typical of warfare in the Solomons, where small units frequently operated in Japanese-held territory to which they moved by submarine, motor torpedo boat or aircraft, and where they were secured against discovery by loyal and co-operative natives. From 30 September until 12 October, a fighting patrol from 29 Battalion under Sergeant G. G. McLeod40 protected a group of four American technicians who were taking astronomical observations on the island of Choiseul, in order to correct irregularities on the existing maps of the Solomons. The patrol was flown from Halavo, an American seaplane base established on the coast of Florida, in a Catalina which also flew them back via Rendova, in the New Georgia Group, at the end of their mission. Friendly natives, to whom McLeod and his men carried gifts of tobacco, food, and clothing, guided the party as it carried out its mission, moving by canoe at night along the coast from village to village without interference. The only excitement during the execution of this valuable task was the failure of the seaplane to rendezvous at the appointed time, causing the party to spend an extra night on the island.

For the assault on the Treasury Group, 8 Brigade came under command of the First Marine Amphibious Corps, command of which passed to Vandegrift on 15 September following the accidental death of Barrett. The whole operation was again under Wilkinson, of Task Force 31. Such naval planning, the work of a United States staff, had been improved after long and often bitter experience since the August landing. Row commanded all land forces, New Zealand and American. He held his first conference on 30 September, the day after receipt of the Corps Commander's letter of instruction, when he explained to his unit commanders the broad outline of the impending operation.

Planning this first opposed landing by New Zealand troops since Gallipoli required the most precise attention to detail so that troops, guns, ammunition, rations, petrol, oil, vehicles, and technical equipment could be disembarked from the proper landing craft in their appointed wave and time on the beach for which they were intended. Row's task was far from easy, as shortages of landing craft still hampered all amphibious operations. Only the barest minimum of such craft was available for this operation and losses seriously jeopardised any future operations. It was impossible, with the craft available, to take more than a minimum number of the troops and supplies forward for the initial landing. Of his total

available force of 6574 all ranks (4608 New Zealanders and 1966 Americans), only 3795 could be accommodated for the assault, leaving the remainder to go forward in four successive flights, one every five days. Battalion strengths were reduced to 600 each and their transport to two 30-cwt. trucks and four jeeps. The assault force required to take with it 1785 tons of supplies and equipment, leaving several thousand tons to go forward with succeeding flights. In planning this action men, supplies, and equipment were distributed over thirty-one different landing craft of six different types, transported 300 miles north and, within a few hours, landed in successive waves against opposition on beaches familiar only from air photographs. Landing craft speeds ranged from six to 35 knots, and as much as three days elapsed between the despatch of the first and last convoys from Guadalcanal. All craft of the first flight were tactically loaded, with men and supplies so distributed that if one boat was lost the whole operation would not be imperilled.

Brigade Headquarters was expanded to deal with the increased work such planning demanded, not only for the actual assault but for the loading and equipment tables of every landing craft of succeeding flights. Not a foot of space was wasted; the loading tables were meticulously detailed. Major J. G. S. Bracewell was brought up from Base in New Caledonia and appointed AA and QMG, Captain B. M. Silk was attached as staff captain movements, and Captain R. S. Lawrence, of 36 Battalion, as staff captain A to assist the normal staff of the brigade which, once ashore, would constitute an island command. Captain John Merrill, an interpreter of Japanese from 14 Corps Headquarters, also joined the brigade to translate captured documents and interrogate prisoners of war. Lieutenant-Colonel J. Brooke-White41 was appointed New Zealand liaison officer on Corps Headquarters during the planning period, which required the precise co-ordination of all navy, army, and air elements. He and others soon discovered that the service language of the two peoples differed greatly as, for example, when New Zealand ‘unit equipment’ became American ‘impedimenta’.

Only one area in the Treasuries was suitable for a landing by heavy LSTs carrying earth-moving equipment, unit transport, guns and weighty stores—the sandy beaches of a small promontory at Falamai, on the coast of Mono, two miles from the western entrance to Blanche Harbour, and close beside the headquarters of the Japanese garrison. Row decided to make his principal assault there,

using two battalions, the 29th on the right flank and the 36th on the left, at the same time moving 34 Battalion on to Stirling Island to establish a perimeter wherein the artillery was to be sited along the inner shore in support of troops in action across the water on Mono Island. Guns, both field and anti-aircraft, were to be ferried across Blanche Harbour from the Falamai beach-head and emplaced with the utmost urgency.

While this main assault was in progress, a small separate force was to be landed at Soanotalu, a narrow bay on the north coast of Mono, to install a radar station which would look directly into Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville. Topographical information concerning these islands was reasonably good. It was assembled from most excellent air photographs taken, with great thoroughness, by American reconnaissance units and known as ‘hasty terrain’ maps; the personal observations of a naval and marine patrol which landed from a submarine and spent six days on Mono Island in August; and from talks with American airmen who had been rescued from the island after spending some time there when their machine was shot down. From all available sources the brigade intelligence section constructed a twelve feet square sand model for more complete comprehension of Row's plan of attack, which he set about completing with energy and perspicacity.

Twenty miles of primitive roads and a faulty telephone system separated Row from Corps and Task Force Headquarters, and delays in obtaining information and decisions frequently hampered planning, all of which was dictated by the amount of shipping available. The arrival at the last moment of some of the more hastily assembled American units, and the lack of knowledge of their particular tasks also delayed completion of final loading tables, as they were unable to furnish such vital information as the amount of shipping space required and the number of men they were taking forward in the first flight. As the tactical loading and equipment tables were completed ten days before departure, this often led to wasteful and hasty rearrangement.

Only meagre information was available concerning the strength of the enemy and his dispositions in the Treasury Group. In order to overcome this deficiency, Sergeant W. A. Cowan,42 a member of the brigade intelligence section who really measured up to the requirements of that organisation, made two trips to the island before the landing took place. In company with Corporal J. Nash, an Australian coastwatcher, and two members of the British Solomon Islands Defence Force, Warrant Officer F. Wickham and Sergeant

Ilala, Cowan spent twelve hours on Mono Island, landing there at midnight on 22 October by canoe from a motor torpedo boat. When he and his party returned the following night, they brought with them three American airmen whose machine had been shot down off the island, and six natives who were to act as guides on the day of the landing. Their return was another comment on this island warfare. After boarding the motor torpedo boat in the darkness off Mono, they sped to Vella Lavella where a waiting aircraft flew the party to Guadalcanal; the natives, emerging from the jungle for the first time in their lives, were pop-eyed with excitement as they marvelled at the wonders of travel war had brought to them. Cowan produced a valuable report, information from which was quickly disseminated to units ready to depart, though the slower-moving craft had already gone. The Japanese garrison, reinforced by 50 men a few days before his arrival on the island, was estimated at 225, with headquarters near the Saveke River, strongposts and the main garrison covering Falamai Beach, and observation posts at Laifa Point and other sites round the coast. Stirling. Island was free of Japanese. Cowan returned to Mono by motor torpedo boat on the night of 26 October, taking with him Corporal W. Gilfillan, Private C. Rusden, and Private J. Lempriere,43 all of 29 Battalion, to organise native patrols, known as ‘blokes’, and cut the Japanese telephone line between Laifa Point and headquarters on the morning of the landing.

The original plan for a simultaneous assault on the Treasury Islands and Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November was discarded by the South Pacific Command on 12 October in favour of sending Row's brigade into the Treasuries on 27 October, five days before the establishment of the Bougainville beach-head, in order to have a radar station in operation on Mono. On the night of 27 October, also, a realistic diversionary raid by 2 US Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel V. H. Krulak was to be made on the island of Choiseul. Krulak was to be prepared to remain there for an indefinite period, which he did, remaining at Voza until the night of 3–4 November, and baffling the Japanese command by concealing the exact locality of the next Allied thrust.

Row issued his first administration order for the Treasury operation on 11 October and his first operational order on the 21st, by which time all details were completed by the planning committee. The administration order set out minutely the beach organisation, working parties for unloading, the pooling of transport to facilitate

unloading, and all details for succeeding flights. From 14 to 17 October the brigade rehearsed the landing on Tumuligohm Beach, on Florida Island, using four APDs and eight LCIs with which to practise embarkation and disembarkation, loading and unloading equipment, and the quartering of personnel. No detail was forgotten in making these practice landings as realistic as possible.

On 23, 24, and 25 October the slower craft were loaded and despatched from Guadalcanal, staging north via the Russell Islands and Rendova, their movements co-ordinated, under destroyer protection commanded by Rear-Admiral G. H. Fort, so that they would rendezvous off Blanche Harbour on the morning of 27 October. Finally, the faster APDs carrying the assault troops left Guadalcanal on 26 October, the Brigadier and his staff travelling in USS Stringham. The whole force bore a farewell message of the kind to which American commanders were addicted. It concluded: ‘Shoot calmly, shoot fast, and shoot straight’. The men each carried two days' rations, and in their equipment was half a ‘pup’ tent, to be joined with another and set up as one in the bivouac area ashore. They wore steel helmets but carried soft jungle hats in their haversacks. Gas respirators were discarded. The assault troops wore camouflaged jungle uniforms of drill to make them less distinguishable in the jungle; some daubed their hands and faces with stain. The journey to the Treasuries was uneventful. Some men slept on deck in the hot night, for there was no moon.

The following units of the brigade made the landing on Treasury:

29 Battalion (Lt-Col F. L. H. Davis)

34 Battalion (Lt-Col R. J. Eyre)

36 Battalion (Lt-Col K. B. McKenzie-Muirson, MC)

38 Field Regiment (Lt-Col W. A. Bryden)—only one battery made the original landing.

29 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Lt-Col W. S. McKinnon)—two batteries made the original landing.

54 Anti-Tank Battery (Maj R. M. Foreman)

8 Brigade MMG Company (Maj G. W. Logan)

23 Field Company Engineers (Maj A. H. Johnston)

4 Motor Transport Company ASC (Maj R. Gapes)

7 Field Ambulance (Lt-Col S. Hunter)

2 Field Surgical Unit (Maj G. E. Waterworth)

Malaria Control Section (2 Lt R. D. Dick)

J Section Signals (Capt G. M. Parkhouse)

10 Mobile Dental Section (Capt J. H. Neville)

Brigade details.

American units included 198 Coast Artillery Anti-Aircraft Regiment (less one battalion) with sixteen 90-millimetre and thirty-two 37-millimetre guns and twenty searchlights; a company of 87 Naval Construction Battalion (the CBs), and technical personnel to

operate air support, radar station, advanced naval base, a boat pool and a signals unit, totalling 1966 all ranks, 60 per cent of whom landed with the first assault troops.

Zero hour for the landing was set for six minutes past six on the morning of 27 October, but because of the late arrival of the APDs it was delayed for twenty minutes and the radio silence broken by its dissemination to vessels of the convoy. In the grey light of breaking day, and wrapped in a drizzle of warm rain, the convoy lay off the western entrance to Blanche Harbour—eight APDs, eight LCIs, two LSTs and three LCTs, protected by a screen of six American destroyers. Overhead circled a fighter cover of 32 aircraft, including New Zealanders of Nos. 15 and 18 Squadrons, RNZAF, which patrolled from first light. Rain squalls came down as the assault troops descended the rope ladders into the landing craft, which rose and fell below them on the lazy swell, in readiness for the two miles dash up the harbour. Above them, out of

Arrows indicate the move of 8 brigade units for the capture of the Treasury Group. The opposed landing was at Falamai, on Mono Island.

the mist, rose the grey mushroom of Mono and, on the right, the dim shape of trees on Stirling. Moving sluggishly off the islands lay the large landing craft, waiting their turn to enter the harbour and beach after the way had been paved by the assault troops.

Promptly at 5.45 a.m. the guns of two American destroyers, Pringle and Philip, cracked in the morning stillness as they bombarded Falamai and its environs, though many of the shells caught the crest of an island in the harbour and failed to reach their objective. By six o'clock, as the light revealed the scene in detail, the first wave was on its way to the beaches in an atmosphere of noise, rain, and excitement. Because destroyers were unable to manoeuvre in the harbour, newly converted LCI gunboats, recently arrived from Nouméa and used experimentally for the first time, moved on the left flank of the assaulting waves, pouring streams of tracer like coloured water from a hose into the undergrowth along the shore. They undoubtedly reduced the number of casualties, though by tarrying a little too long off Falamai they did hold up an assault battalion after it landed.

Two minutes after the naval bombardment ceased the first wave of assault troops leaped ashore at 6.26 a.m. from the landing craft, as though on a well-executed manoeuvre. As these craft emptied and withdrew, succeeding waves followed at thirty-minute intervals until the last and heavier craft arrived at 9.20 a.m. B and C Companies of 29 Battalion moved quickly through the village of Falamai, with A Company coming in on their left flank to sweep across the whole battalion sector from Cutler's Creek, on the extreme left flank, to the Kolehe River on the extreme right. A and B Companies of 36 Battalion disappeared into dense undergrowth between the Saveke River and Cutler's Creek, A Company under Captain K. E. Louden44 being temporarily held up by the gunboat's stream of tracer, though it went in later to rout out Japanese headquarters 500 yards west of the Saveke River.

There was little opposition to the immediate landing and initial casualties were light. Unexpectedly, landing craft were fired on from Cumming's point on Stirling Island, though no enemy was ever found there. The Japanese garrison (their official time was always different) ceased communication with its headquarters in Rabaul with a message ‘Enemy landing commenced at 0540 hours. We have engaged them.’ before Louden's men drove them up the hillside.

In the first rush from the beaches some enemy strongposts were overrun and the garrisons went to earth, emerging again to take the landing troops from the rear. One of these posts was demolished

by Private E. V. Owen45 (a man over forty with a son serving in the RNZAF) and Private E. C. Banks,46 using hand grenades. Then, as the large LSTs beached at half past seven, another enemy strongpost 20 yards from the shore came to life, pouring machine-gun fire into the craft as the ramp was lowered. It created considerable damage before it was silenced by a resourceful American, Carpenter's Mate 1st Class Aurillo Tassone, of the CBs, who, using a bulldozer as a tank and its shining blade as a shield, crushed the garrison and buried the 24 Japanese occupants in one operation. He was awarded the Silver Star. A party of anti-aircraft gunners, landing with the second wave, attempted to liquidate this strongpoint, and Gunner M. J. Compton47 disposed of some of the occupants before the bulldozer arrived. Captain H. H. Grey,48 also a gunner, collected a party and played an infantry role by seeking enemy strongposts.

Activity on the beaches was frequently more intense than in the jungle. Sapper J. K. Duncan,49 of 23 Field Company, never left his bulldozer, but kept tracks open from the landing craft to the dump areas, despite exploding mortar bombs.

By 7.35 a.m. the Japanese garrison had reorganised itself and laid down concentrated and accurate mortar and machine-gun fire on the beaches, where the LSTs were unloading heavy supplies, guns, and equipment. Direct hits set two of them on fire, but unloading parties quickly extinguished the outbreaks. Unit parties organising dumps of equipment on the beaches and sorting out gear as it came ashore were caught in the Japanese bombardment. One American 90-millimetre anti-aircraft gun and one New Zealand Bofors gun were destroyed; one 25-pounder gun of 38 Field Regiment was badly damaged and large quantities of ammunition and medical stores were lost. An artillery jeep and truck were both hit and much valuable equipment destroyed; another truck belonging to 4 Company ASC, loaded with ammunition, received a direct hit and blew up, pieces of the truck wrapping themselves round a palm trunk forty feet away. Just before midday a Japanese ammunition dump was hit and blew up, setting fire to the remaining huts of the village, where smoke and flames added to the unholy orchestra. Exploding ammunition caused LST 399 to retract from the beach and move farther along the shore.

Because of the difficult country—dense forest cut by deep water-courses—the site of the enemy guns was difficult to pinpoint. At

ten o'clock two platoons of 36 Battalion were ordered to search the high country above the old Japanese headquarters. One of these, under Second-Lieutenant L. T. G. Booth,50 quickly achieved its objective and stopped the beach bombardment. Scrambling up the hillside through the densest undergrowth, Booth and his men located and rushed the first enemy position and captured two 75-millimetre mountain guns, the barrels of which were still hot. Then, guided by the sound of a mortar in action, Booth led a section of his men 500 yards farther up the hill and captured a 90-millimetre mortar. Ten members of the crew were killed; the remainder fled. All enemy resistance in the immediate vicinity of the landing was overcome soon after midday and battalions dug in along their perimeters from 400 to 600 yards in the jungle, which was much thicker than information had led them to believe.

The Stirling landing was unopposed and accomplished with ease; as troops cleared Falamai, boats carrying 34 Battalion swung right and went ashore. Two sections of 3-inch mortars were established on Watson Island to cover the perimeter on Mono. Brigade Headquarters, landing in the second wave, moved into a small bay on the inner shore of Stirling and was soon in wireless communication with units scattered over the two islands. During the day guns of 29 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment and 38 Field Regiment were landed from LSTs at Falamai and ferried across Blanche Harbour. Late that afternoon they were dragged ashore over the coral and sited along the northern shore of Stirling, from which they covered the whole of Mono Island and both entrances to the harbour. One battery of anti-aircraft guns was temporarily sited on Watson Island. Incredible quantities of coconut palms and vegetation were felled that day to give the guns arcs of fire.

Activity on the beach, though hindered temporarily by exploding ammunition, proceeded with only one hitch. Typical of the speed in unloading the earlier craft was the record of LCI 330, which discharged 299 men and 15 tons of cargo in 14 minutes. Only a few tons of cargo were returned to Guadalcanal in one of the LSTs, because of some misunderstanding of the respective functions of the crew of the craft and the New Zealand unloading parties. After the trucks and jeeps on LST 399 were driven ashore, work on this craft almost ceased and the American commander reported that unloading became ‘inexcusably slow’. The commander of the LST could not convince the troops that unloading was a troops responsibility, and there was some disorganisation of beach parties because of casualties. Otherwise all arrangements, despite the temporary hold-up because of exploding ammunition, went according

to Row's well-conceived plan, and by nightfall most of the landing craft were on their way back to Guadalcanal, there to load the second flight.51

When darkness came, bringing with it more torrential rain, the two battalion perimeters were established, the men sharing without complaint their dank cruciform foxholes with centipedes and other insects repulsive to a degree. During the day a few snipers were shot out of trees inside the perimeter, and under cover of darkness the Japanese attempted to reach their ration dump, which was outside the 36 Battalion perimeter and could not be moved during the day. However, no determined attack developed. From the high country the Japanese dropped occasional mortar bombs into the beach area and swept it periodically with bursts of machinegun fire. A nervous reaction to the night noises and the events of the day caused some indiscriminate shooting, which revealed the position of the men and their posts, but there were actually fewer snipers than was indicated by the excitement they caused. On one occasion, to prove that a tree did not contain snipers, it was ordered to be felled, but nothing unusual spilled out of the branches.

Row had every reason to congratulate himself on his accurate and exhaustive planning. No call was necessary on his reserve—30 Battalion, waiting on Vella Lavella—though he employed the additional anti-aircraft units placed at his disposal by Barrowclough. Capture and consolidation of the Treasury Group on 27 October was accomplished with the loss of 30 killed (21 New Zealanders; 9 Americans) and 85 wounded (70 New Zealanders; 15 Americans), though Japanese aircraft came in after dark that night, spilling their bombs haphazardly over the Falamai and Saveke area, killing and wounding some men of 36 Battalion. But there was no counter-attack from the Shortland Islands, though Row was gravely concerned that such might develop. Had it done so ample warning would have been given by a squadron of motor torpedo boats which, under Lieutenant-Commander R. B. Kelly, US Navy, moved out of Blanche Harbour in the deepening dusk and maintained a constant night patrol of the waters between Shortland Islands and the Treasuries. Both entrances to the harbour were covered by detachments of guns of 54 Anti-Tank Battery, and the guns of both 38 Field Regiment and 29 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment were given secondary roles of firing on surface craft. The day following the landing, and for some days afterwards, patrols from 29 and 36 Battalions moved beyond their strengthened perimeters without meeting resistance, though they found traces of

the enemy, who had picked up his dead and wounded and retired to the northern coast of Mono Island. Hit-and-run bomber raids were made over the Falamai area the first few nights only, after which they diminished.

Although the landing was observed by the Japanese, little action was taken because of pressure by Australian and American forces in New Guinea, where the battle at Lae, Salamaua, and Finschhafen was adversely affecting them. A reconnaissance aircraft, known as a ‘snooper’, picked up the convoy at 4.20 a.m. as it approached Mono and signalled the information to Rabaul. The commander of the South East Area Fleet immediately ordered an air attack and directed submarine RO-105 to the Treasury Group to report on Allied activity. This craft was sighted from Soanotalu by members of Loganforce as it lay off the island. An air attack by 39 Zeros and 10 carrier bombers from the Shortlands did little damage until nightfall.

During the day enemy aircraft were held off by No. 15 Squadron RNZAF, under Squadron Leader M. J. Herrick,52 and No. 18 Squadron under Squadron Leader J. A. Oldfield,53 which, with American aircraft working from Vella Lavella, maintained an effective cover only rarely broken by the enemy, four of whom were shot down. Although Japanese reports made extravagant claims of sinking two American transports and two cruisers, they did little damage, their only target being the US destroyer Cony, on which they dropped two bombs. A night raid on Mono, built round the light cruiser Nagara and ten destroyers then at Rabaul, was planned by the Japanese area commander but was cancelled the following day because of the rapidly deteriorating situation in New Guinea.

Meanwhile, as Falamai was cleared and consolidated, Loganforce, named after its commander, Major G. W. Logan,54 went about its appointed task on the other side of Mono, and wrote a gallant little page of history in doing so. Covered by the American destroyer McKean, Logan disembarked his small force of 200 all ranks at dawn on 27 October without opposition and established a perimeter round the tiny 40-yards-wide beach, overhung with trees, at the mouth of the Soanotalu River, above which rose forest-clad cliffs in a verdant semi-circle. This force consisted of D Company, 34 Battalion, under Captain Ian Graham;55 one section of the MMG

Company under Sergeant T. J. Phipps;56 an artillery observer, Captain D. J. S. Millar,57 of 52 Battery; a field ambulance detachment under Captain C. C. Foote;58 a detachment of the United States naval construction battalion under Lieutenant C. E. Turnbull, and a detachment of American radar technicians. By midday patrols reconnoitred the surrounding country without finding any trace of the enemy, the American technicians sought out and recommended sites for radar, and during the afternoon engineers began forming a road up the rising ground from the beach in readiness for the equipment, which was barged round from Falamai and arrived the following day. Late that afternoon natives arrived in the perimeter with Flight Sergeant George Luoni,59 a New Zealand airman whose machine had been shot down off Mono a month previously. He had been hidden and protected by natives until he was discovered in a hut by members of Cowan's patrol, the night before the landing.

Each day patrols from Graham's company worked out to a depth of 1000 yards through the jungle and along the coast, and by 29 October ran against small parties of Japanese filtering through from Falamai. The first serious attempt was made to reach the beach late that afternoon, when a party of twenty Japanese attacked the perimeter but were driven back by No. 14 Platoon under Lieutenant R. M. Martin,60 leaving five dead. That night guns of 38 Field Regiment emplaced along the harbour coast of Stirling Island, six miles away, registered outside the Loganforce perimeter, lobbing their shells over the crown of Mono. Clashes with the enemy halted neither the construction of the road nor the installation of the urgently required radar, the first of which was in operation two days after landing at Soanotalu. There was difficulty in restraining the enthusiasm of the American technicians, both radar and engineer, who frequently assisted the New Zealand patrols instead of concentrating on their construction work.

By 30 October, when it was obvious that the Japanese refugees were concentrating round Soanotalu, as Barrowclough had anticipated when he approved the original plans, Row despatched reinforcements from 34 Battalion,61 consisting of C Company headquarters and one platoon and the carrier platoon (used as infantry)

under Major J. C. Braithwaite.62 These were disposed round the second radar site, equipment for which was dragged up the hillside from the beach and emplaced on higher ground the following day. It was operating on 31 October with the radius of 107 to 124 miles, and fulfilled its mission by being ready for the Empress Augusta Bay landing on 1 November.

Meanwhile, increasing patrol clashes indicated growing Japanese strength, though the enemy made no attempt no reach the radar and was unaware of its existence. A small patrol under Lieutenant J. A. H. Dowell63 encountered a strong enemy force 1500 yards beyond the perimeter on 1 November and withdrew after inflicting damage, as Dowell feared an ambush in such close country. With the arrival of reinforcements Logan divided his force, using Braithwaite's group to guard the radar station high above the beach and the remainder to guard the original perimeter round headquarters and a second station. Closer to the beach, inside the perimeter in a strongpoint covering a barge drawn up on the sand, was a small force of nine men, six New Zealanders and the three American members of the barge crew, under Captain L. J. Kirk.64

Late on the night of 1 November, between sixty and ninety Japanese attacked the west perimeter, using grenades, mortars, and machine guns in an attempt to reach the landing barge. Before midnight the field telephones joining strongpoints with the commander had been put out of action by grenades, and the groups fought independently of each other. Japanese infiltrated through the perimeter and attempted to break Kirk's small garrison, which was armed with hand grenades, one tommy gun, and two machine guns taken off the barge. The first assault came at 1.30 a. m., killing Staff-Sergeant D. O. Hannafin65 and wounding Kirk, whose skull was creased with a bullet. He recovered and continued directing the defence. When the machine guns were hit and put out of action, Kirk and his men held off the Japanese with hand grenades. A suggestion to abandon the strongpost and withdraw to the main defence position was discarded in favour of holding out until day-light. Soon afterwards Kirk was again wounded, this time fatally, though he survived until next day. Command of the little garrison passed to Private C. H. Sherson66 and, when he was wounded as the Japanese pressed their attack, to the company cook, Private

J. E. Smith,67 who led the defenders until dawn, after which the Japanese melted away into the jungle. When daylight came a patrol was despatched from Logan's headquarters to investigate the state of the beach post, shooting a sniper on the way. Twenty-six Japanese dead lay round Kirk's strongpost. Some of them had reached the barge and were killed beside it. Most of Kirk's garrison were wounded, including one of the Americans and Smith himself who, in the midst of the grim scene, was busily preparing breakfast.

Platoons on the west perimeter fought off the attackers without loss. Fifty Japanese dead were counted that morning by patrols, but as on every other occasion, the wounded had been removed. Captured enemy equipment included five knee mortars, four light machine guns, several dozen rifles and one sword. During the day Logan reorganised his defences in readiness for attacks which came on the two following nights, though with decreasing violence, from desperate refugees who represented the last Japanese resistance on Mono. Patrols afterwards fanned out from the perimeter, picked up a few stragglers, and drove the remainder into hiding. D Company was relieved by A Company under Captain A. G. Steele68 on 5 November, but the Loganforce garrison was never again attacked.