Chapter 7: The Battle for the Solomons

I: Japanese Plans Defeated

MOBILISATION orders to General Juichi Terauchi's South Army, elements of which ultimately reached the Solomons, were issued by Japanese Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo on 6 November 1941, a month before the attack on Pearl Harbour, and the areas to be seized were decided on 20 November while British and American diplomats were negotiating in an attempt to avoid a conflict with Japan. Operations were to begin simultaneously with those of the Combined Japanese Fleet, and the areas to be seized were clearly defined in the following order:

1. The seizure of Malaya, British Borneo, the Philippines, and North Sumatra.

2. The seizure of Java.

3. Cleaning up Burma.

Two paragraphs disposed of the objective:

(a) The objective of this operation is to destroy and seize enemy strongholds of Britain, the United States, and the Netherlands;

(b) The sectors to be seized by the South Army are the Philippines, British Malaya, Java, Sumatra, Borneo and Timor, &c. (‘etcetera’ presumably meaning all the intervening island groups).

This operation was the fulfilment of secret plans contained in an ‘Outline of Japanese Foreign Policy’, dated 28 September 1940, and issued by the Japanese Foreign Office, in which the establishment of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere was definitely defined:

In the regions including French Indo-China, the Dutch East Indies, Straits Settlements, British Malaya, Thailand, the Philippine Islands, British Borneo and Burma, with Japan, Manchukuo and China as the centre, we should construct a sphere in which the politics, economy, and culture of those countries and regions are combined.

(a) French Indo-China and the Dutch East Indies: We must, in the first place, endeavour to conclude a comprehensive economic agreement (including the distribution of resources, trade adjustment in and out of the Co-prosperity Sphere, currency and exchange agreements, &c.), while planning such political coalitions as the recognition of independence, the conclusion of mutual assistance pacts, &c.

(b) Thailand: We should strive to strengthen mutual assistance and coalition in political, economic, and military affairs.

On 4 October 1940 a tentative plan for policy towards the southern regions was secretly drawn up, the first paragraph of which gives the clue to Japan's aggressive attack: ‘Although the objective of Japan's penetration into the southern regions covers, in its first stage, the whole area to the west of Hawaii (excluding for the time being the Philippines and Guam), French Indo-China, the Dutch East Indies, British Burma and the Straits Settlements are the areas which we should first control. Then we should gradually advance into the other areas. However, depending on the attitude of the United States Government, the Philippines and Guam will be included.’

In detailing this plan an independence movement, which would cause France to renounce her sovereign right, was to be manoeuvred in French Indo-China, every attempt was to be made to reach an understanding with Chiang Kai-shek in China, and the army of Thailand left to control Cambodia. These actions were to be governed by Japan's liaison with Germany (with whom she had complete diplomatic understanding), and the success of the German military operations to land in Britain.

By the first week in May 1942 elements of Terauchi's army had reached as far south as Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Solomons, and east to Tarawa in the Northern Gilbert Group. Only one corner of New Guinea of all the island territory north, north-east, and north-west of Australia remained to the Allies and there, in valleys behind Port Moresby, Australian forces were concentrated and airfields established as quickly as the machinery could make them available for use by aircraft, most of which were coming from America. Only the Owen Stanley Ranges separated them from the Japanese forces which were established along the northern coast at Lae and Salamaua. Burma, Malaya, the Nicobar and Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean, Java, Sumatra, Timor, the Philippines, Borneo, New Britain and New Ireland, and most of New Guinea itself were held by the Japanese, according to the plans drawn up in Tokyo in 1940.

This swift and unexpected success in overrunning Allied territory, which contributed to her ultimate undoing, encouraged the Japanese High Command to attack the Dutch East Indies sooner than the

provisions of the original plan intended, and then to push farther south beyond the Solomons. In March Terauchi was instructed to complete mopping-up in the captured areas as quickly as possible and to secure a strong defence which would withstand a long period of resistance. Two months later tentative plans were issued for an attack on Port Moresby, Fiji, New Caledonia and Samoa, the occupation of which, in the light of previous successes, was to ‘accelerate the termination of the war’. Those three island groups, and the Northern Gilberts, were to constitute the outer rim of the Japanese defence line in the Pacific. Established in them, and holding Port Moresby to cover the Rabaul arsenal and control the Coral Sea, she aimed to sever all sea routes between America and Australia and New Zealand, thus preventing the concentration in those two countries of forces sufficiently strong for a decisive counter-attack. From aerodromes and naval bases in New Guinea, New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa, ports and bases in the north of New Zealand and on the mainland of Australia were to be bombed into impotence and Japan's inner fortress line, swinging on Rabaul, Truk and Palau, was to have been made impregnable, while behind it she built up her Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. Before this rosy plan could be accomplished, however, the situation was changed, and units were quickly withdrawn from Java and the Philippines and despatched to bolster elements of 17 Japanese Army attempting to retake and hold the Solomons after the American landing there on 7 August.

Japan's advance south had been as swift as it was previously thought impossible before the fall of Singapore. By 3 May a seaplane base had been established at Tulagi, former headquarters of the British administration in the Solomons, and by early August an aerodrome on Lunga Point, Guadalcanal, had been completed. These were in readiness for the contemplated attack on Port Moresby to ensure security on the Japanese left flank. When the first attack on Port Moresby was turned back by the Coral Sea battle, fought out on waters between the Solomons and the Louisiade Archipelago between 6 and 8 May, orders were issued to the 17 Army Commander, Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake, on 18 May to attack New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa, and to continue the attack on Port Moresby overland. The main body of his army, which was created from elements of the South Army after it had completed its original mission, was drawn from 5, 18, and 56 Divisions, the principal units of which were concentrated at Davao, in the Southern Philippines, with others in Java and Rabaul. Hyakutake moved his headquarters and the main force to Truk and elements to Rabaul and Palau from the end of June to the

beginning of July, when the attack on the island groups was to be developed.

The Fiji defences, with which 3 New Zealand Division was so long and arduously concerned, were never tested, though the island itself was vital to the ultimate success of the Pacific war. If the Japanese attack had come in early July as originally planned, it is doubtful whether they would have held for any length of time against the weight of the naval and air support under which the Japanese proposed to put their land forces ashore At that time the anti-aircraft defences of Fiji had been strengthened by the arrival of American units, as plans were in preparation for the relief of 3 Division. Considerable American strength was also being built up in New Caledonia and Samoa.

The attacking force under Hyakutake which was designed for the conquest of the three island groups was a strong one, with overwhelming naval support from the Second Fleet under Vice-Admiral Nobutake Kondo, consisting of 13 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 24 destroyers, and the First Air Fleet under Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, with seven aircraft carriers and eleven destroyers as well as auxiliary supply ships. This whole invasion force was to be protected by Vice-Admiral Gunichi Mikawa's fleet, which included the four battleships Hiyei, Kirishima, Kongo, and Haruna. Although the three island invasion forces never got beyond the planning stage, many of the units taking part had been moved to Rabaul from Davao and Java. Major-General Kiyotake Kawaguchi commanded a force of 9126 all ranks assigned to attack Fiji. This consisted of 35 Infantry Brigade (from 35 Japanese Army in the Philippines) with the following units attached: two battalions of 41 Infantry Regiment; 45 Field Anti-Aircraft Battalion and two independent anti-tank companies; 20 Independent Mountain Artillery Battalion; 15 Independent Engineer Regiment, with an engineer company attached for heavy bridging; a motor transport company; a hospital; strong signals units equipped with field wireless; and a water supply unit. The South Seas Detachment of 5549 all ranks, under Major-General Tomitara Horii, was assigned for the invasion of New Caledonia and was built round 55 Infantry Brigade Group, 144 Infantry Regiment, and 47 Field Anti-Aircraft Battalion and ancilliary units from 55 Brigade. A force of 1215 all ranks, commanded by Colonel Kiyomi Yazawa and built round a battalion of 41 Infantry Regiment, with a land combat battalion and supporting units from 14 and 17 Armies, was assigned to take Samoa.

Each of these three landing forces contained elements of 17 Army and was particularly strong in communications units—all eight

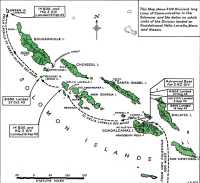

This Map shows 3 NZ Division's long lines of communication in the Solomons and the dates on which units of the Division landed on Guadalcanal, Vella Lavella, Mono and Nissan.

radio platoons and an independent company being equipped with motorised vehicles. These three expeditions, timed to begin simultaneous attacks in order to divert and cause the dispersal of any relief forces, were disastrously affected by the Battle of the Coral Sea, which halted their preparations, and then by the Battle of Midway, which forced their cancellation, as many of the naval and air units destined for them were destroyed or damaged.

The first tests of American aggression, which ultimately led to these two sea battles, developed from audacious raids on Japanese targets in the Caroline and Marshall Islands on 31 January 1942, and on Wake Island on 24 February, by naval units commanded by Halsey, who later succeeded Ghormley as commander of the South Pacific area and whose pugnacious character was reflected in his directives and strategy for the Solomons campaign. These tests demonstrated that air power and air superiority were necessary in all naval engagements. This had been a potent factor in all early Japanese successes, and was proved again and again when the Pacific campaign began and Allied air power gradually reduced the Japanese and finally drove them from the skies.

The battles of the Coral Sea and Midway preceded the landings at Tulagi and on Guadalcanal and turned the tide in the Pacific. They decisively halted the Japanese drive south and restored the balance of sea power until it swung in favour of the Allies. The first, the battle of the Coral Sea, from 6 to 8 May 1942, turned back the Japanese Fourth Fleet, commanded by Vice-Admiral Inouye, which was protecting a large convoy carrying a force commanded by Lieutenant-General Momotake intended for the assault on Port Moresby from the sea, and caused postponement of the projected attack on New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa. Not a single shot was exchanged between the surface ships of the opposing forces and, for the first time in history, a decisive naval battle was fought exclusively between carrier-borne and land-based aircraft. The Allied naval force, commanded by Rear-Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, included the Australian cruisers Australia and Hobart and the American carriers Lexington and Yorktown, with six heavy and light cruisers, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Astoria, Chester, Portland and Chicago, with their protective destroyer screens. They caught the Japanese force before it turned north in the Coral Sea and joined battle on 7 May. The Japanese aircraft carrier Ryukaku was sunk by aircraft from the Lexington and Yorktown with the loss of only one American dive-bomber, and the Shokaku was put out of action the following day and withdrawn. Both the American

carriers were damaged, the Lexington so severely that she was abandoned and sunk by her own people. The United States destroyer Sims and a tanker and 66 aircraft were also lost during the battle, but the Japanese force was so severely mauled that it turned back to Rabaul with the invasion force. On 4 May, before this action began, the Yorktown's aircraft inflicted severe and unexpected damage on 19 Japanese Seaplane Tender Division which had occupied Tulagi and Gavutu, off Florida Island, to protect the flank and assist with the assault on Port Moresby.1

A lull followed the Coral Sea battle, and American carriers and supporting craft were recalled from the South Pacific in readiness for another move. Naval patrols were established to the west of Midway Island, which lies north-west of the Hawaii Group, as American intelligence, obtained from such a reliable source as decoded Japanese naval signals, estimated that an attack was imminent against that island outpost. The total United States forces available in the Central Pacific were three aircraft carriers, the Enterprise, Hornet (which was returning from a raid on Tokyo on 18 April), and Yorktown (which had been patched up after the Coral Sea battle), seven heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, 14 destroyers and 20 submarines, divided into two task forces under Fletcher and Rear-Admiral R. A. Spruance. The Japanese Combined Fleet, under Admiral Yamamoto, was sighted on the morning of 3 June, some hundreds of miles south-west of Midway, moving east. Its arrival within reach of Midway was co-ordinated with a Japanese move into the Aleutians, where enemy forces landed on Kiska and Attu that same day. In the afternoon of 3 June Yamamoto's fleet was attacked by heavy bombers from Hawaii which inflicted the initial damage. The following morning two enemy carriers and the main force were picked up and attacked by aircraft from the Midway garrison. The United States fleet's carriers then entered the battle with conspicuous success but great loss. A torpedo squadron from the Hornet, without protection, attacked the four Japanese carriers. Every aircraft was shot down and only one American pilot survived. Torpedo squadrons from the Enterprise and the Yorktown then attacked, losing heavily but registering hits on the Japanese carriers. By the end of the day two Japanese carriers were on fire and out of action, a third damaged and later sunk

by submarine, and a Japanese battleship and cruiser badly damaged. A furious air battle continued throughout 5 June, during which American aviators maintained their initiative, but poor visibility prevented conclusive action. On 6 June aircraft from the Hornet sought out units of the dispersing Japanese fleet, scoring hits on cruisers and destroyers. The remainder, denuded of their air support, scattered and fled.

The Japanese had suffered their first decisive naval defeat since 1592, when a Korean admiral routed a Japanese fleet under Hideyoshi. At Midway they lost four aircraft carriers—the Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga and Soryu; the heavy cruiser Mikuma and two battleships, four cruisers, and three destroyers were damaged. The American forces also lost heavily in men and aircraft. The Yorktown was hit by two torpedoes on 5 June and sank the following day, and the destroyer Hammann, which had gone alongside to assist the aircraft carrier, was also torpedoed and sunk. Other vessels were damaged.

The Battle of Midway was one of the decisive battles in the Pacific war and one of the great naval battles of history. It removed the threat to Hawaii and confined future naval operations to the South Pacific; it caused the cancellation of the Japanese move to secure island bases in New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, and it forced the Japanese to waste their strength on two land battles—an attempt to take Port Moresby by crossing the Owen Stanley Ranges and the reckless and disastrous attempt to reinforce and hold Guadalcanal. The Japanese never regained the initiative after the Battle of Midway, and their superiority in the air began to wane from that time. But it was the loss of naval craft, aircraft, and men in the futile attempt to drive the Americans from Guadalcanal which lost them the Solomons and finally, with their equally wasteful battle to hold New Guinea, Rabaul. Despite the fanatical bravery of her fighting men, the Japanese High Command was outmanoeuvred by superior strategy, aided by those twin scourges, malaria and dysentery. Guadalcanal is a horrible example of the wanton disregard of the Japanese for human life, and adherence to an ideal, based on Emperor worship, of implicit obedience to authority in the face of overwhelming adversity.

There is no evidence to prove that Japan ever intended to invade either New Zealand or the mainland of Australia, though her plans did include an enforced acceptance of her predominant direction and role in all Pacific affairs. Before General Tojo went to his death on 23 December 1948 at the conclusion of the International War Trials in Tokyo, quite happily and in the

belief that he would be the future hero of Japan, he gave a final interview at Sugamo prison, where he was confined during the trials. Typed copies of this interview were afterwards submitted to Tojo and his solicitor, Mr. George Blewett, an American who had defended him, and approved by them both. In answer to specific questions regarding Japanese policy and any contemplated invasion of New Zealand and Australia, Tojo replied: ‘We never had enough troops to do so. We had already far out-stretched our lines of communication. We did not have the armed strength or the supply facilities to mount such a terrific extension of our already over-strained and too thinly spread forces. We expected to occupy all New Guinea, to maintain Rabaul as a holding base, and to raid Northern Australia by air. But actual physical invasion—no, at no time.’ Tojo also expressed the opinion that politically Japan lost the war on Guadalcanal, but that he had his first doubts about its outcome after the Battle of Midway. This is supported by extracts from a report in September 1943 by Imperial General Headquarters on the progress of the war after the failure of Japanese arms to retake Guadalcanal:

The fighting power of our naval and air forces had been whittled away in successive operations, particularly at Midway, and recovery was painfully slow. Enemy submarines were a menace to our sea lanes; our shipping losses mounted so that new construction could not match losses. We found it increasingly difficult to provide our vast operational areas with the desired quantities of supplies. Like it or not, our forces, their initiative lost, were now forced into a defensive position. We maintained a longer fighting front than our national resources could justify.

II: The Turning Point

All Japanese naval, military, and economic opinion agreed that Guadalcanal was the turning point in the Pacific war, but the island was held and finally won for the Allies only at great cost, particularly of American naval forces and aircraft. Her navy suffered unmercifully in a series of surface engagements, though never once did the Japanese High Command realise how grievously American strength had been wounded. Although losses on land were less severe, the American Marines who bore the brunt of the early fighting were tested for the first time against a cunning enemy who was as aggressive as the conditions. Handicapped by lack of previous battle experience and by territory which was even more terrifying than his foes, the American soldier gained his bitter experience from hour to hour and day to day. Not a single complete or accurate map existed of Guadalcanal or the other islands, and the outdated hydrographic charts were little

better. Invaluable information was obtained from coastwatchers who, organised by the Australian naval authorities, had secreted themselves and their wireless sets in the jungle when the Japanese arrived. A little more was added by observation from the air, but only by personal observation after landing was any really reliable and accurate detail possible. The invasion force worked from hastily prepared mosaics photographed from the air and assembled with speed.

This is not the place for a detailed account of the land, sea, and air battles which enabled the American command to hold, overwhelm, and finally force the Japanese to give up the struggle for Guadalcanal, and afterwards to continue driving them from island to island until the Solomons were retaken, but these are of such importance to the outcome of the campaign that no account of New Zealand's part in them would be complete without some broad reference to the more crucial engagements. More particularly does this apply to the New Zealand naval and air force units which, because their numbers were more limited than those of the army, operated for the most part as components of larger American formations, whereas army units undertook separate missions, all of which are detailed elsewhere.

On 7 August elements of 1 American Marine Division, under Major-General A. A. Vandegrift, went ashore unopposed on Guadalcanal, but other units under Brigadier-General W. H. Rupertus lost heavily in capturing the islands of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo, where the Japanese had strongly entrenched themselves to protect the seaplane base they had established in sheltered waters among these islands off the coast of Florida, opposite the northern coast of Guadalcanal. The first echelon of these Marines reached Wellington on 4 June 1942 and the second on 11 July. Working day and night in atrocious weather, ships, not loaded for a combat operation, were reloaded with such haste that the convoy of twelve transports and cargo ships was able to depart on 22 July for Fiji to meet the remainder of the invasion force coming down from Hawaii.2 There, in less tempestuous conditions, an armada of 80 ships held a rehearsal of the landing on the beaches of Koro Island between 28 and 31 July. Nothing went right, but no further practices were possible because of the time limit. Under cover of bomber aircraft from three carriers, Wasp, Saratoga and Enterprise, the American invasion force approached round the north point of the island, taking the Japanese garrison in such surprise that those on Guadalcanal fled to the hills, and 11,000 Marines,

with so much equipment that the beaches became congested beyond measure, went ashore the first day.

On Tulagi and the neighbouring small islands, however, resistance was determined and the invaders lost heavily, particularly in the honey-combed hillocks of Gavutu and Tanambogo, which were not subdued for three days. Once established on Guadalcanal, the American forces discovered a useful collection of machinery and equipment on and around the newly constructed airfield opposite Lunga Point, and immediately put it all into operation.3

Because Imperial Japanese Headquarters believed that the result of the battle for the Solomons would decide the fate of the Greater Far East Asia war, orders were issued on 13 August that Guadalcanal must be retaken. Units were haphazardly assembled from the Kwantung Army, the China Expeditionary Force, 38 Division in Sumatra, 2 Division in Java and units from the home front in Japan itself, and thrown into the battle, and the commander of 17 Army, Hyakutake, given the task of driving the American forces from the island. All units of 17 Army already in New Guinea were also withdrawn and despatched to Guadalcanal, and a new command, Eighth Area Army, under Lieutenant-General Imamura, was created with headquarters at Rabaul. This new command incorporated 17 Army and 18 Army, which was commanded by Lieutenant-General Futogo Adachi.

Although ground action on Guadalcanal was fierce and prolonged, the decisive battles were fought between naval units, for the whole of the battle for the Solomons was predominantly naval, with strong support from the air forces. For the first six months after 7 August, these battles were almost continuous on land, sea, and air. Beginning two days after the American landing, a series of violent naval actions was fought at night, usually in rain storms, with star shells and searchlights illuminating scenes made most dramatic and spectacular by burning ships and drifting smoke. Those who witnessed the first of these actions from the high country behind the Guadalcanal beaches speak of them as fantastic theatrical displays on the grandest scale. The first of these sea battles was fought on the night of 8–9 August, on a triangle of water bounded by the north coast of Guadalcanal and the islands of Savo and Florida. Several other naval battles of greater and lesser intensity were fought out in this same region until the battle for Guadalcanal was ended. As soon as the American landing on 7 August was

reported, Mikawa, commander of the Eighth Fleet, decided to attack with every ship at his disposal, and the Seventh Cruiser Division and three destroyer divisions were recalled from duty in the Indian Ocean to join and strengthen him. The American naval force protecting the disembarking combat units and their transports was taken by surprise through not being fully prepared, and suffered disastrously. Between the hour of a quarter to two and a quarter past on the morning of 9 August, with smoke and burning ships obscuring visibility made worse by storms of rain, they lost four cruisers—HMAS Canberra, which sank the following day, and the American cruisers Astoria, Vincennes, and Quincy. Another, the Chicago, was so badly damaged as to be useless in action. American ships almost collided during the action and the Chicago's star shells failed to function. Although the Americans lost heavily, they saved their aircraft carriers which were ordered to leave the area. Fortunately an eight-inch shell destroyed the operations room on Mikawa's flagship, the Chokai, which was partly responsible for a rapid withdrawal from the area without fully appreciating the damage which had been done.

Again and again, following their first attempt to land on the night of 23–24 August, the Japanese tried to reinforce and strengthen the garrison in accordance with instructions received from Imperial General Headquarters that all key positions in the Solomons must be recaptured. Men and supplies, under cover of strong naval protection, were despatched in destroyers to Guadalcanal from concentrations in the Shortland Islands and at Rabaul, their departure so timed to stage in daylight down ‘the Slot’, a name given by the Americans to the waters between the islands of Choiseul, Santa Isabel, and the New Georgia Group, disembark under cover of darkness on the Guadalcanal beaches between Point Cruz and Cape Esperance, and retire by daylight. These nightly operations became known as the running of the ‘Tokyo Express’, which the American command was unable to disrupt until Japanese naval strength had been reduced by several battles of great violence. By October 20,000 Japanese had been landed, including 2 Division, a regiment of 38 Division, and strong artillery and engineer units. American strength had been increased to 23,000 but malaria, because of the lack of precautions so successfully instituted later, was already taking toll of the Marines, 1960 of whom were in hospital.

Because American naval strength had been so grievously reduced in the first clash on the night of 8–9 August, Japanese naval vessels approached Guadalcanal during hours of darkness and bombarded Henderson Field and American service installations with impunity, creating great loss. Ships and aircraft were also

required to protect the vital sea lanes between Guadalcanal and the New Hebrides and New Caledonia and, in lesser degree, to New Zealand and Fiji. Actions almost daily whittled down the husbanded strength of the American commands, and by 15 September only one aircraft carrier, the Hornet, remained undamaged in the whole of the South Pacific. The other three had been put out of action in various engagements—the Saratoga, though she was able to reach Tonga after being torpedoed, the Enterprise, which eventually reached Pearl Harbour for repairs, and the Wasp, which had cost 21 million dollars, and was sunk while escorting supply ships to Guadalcanal on 15 September. Earlier in the war she had ferried aircraft reinforcements to Malta. The valuable battleship North Carolina was also out of action.

In the battle of the Eastern Solomons, fought out on 23–24 August to the east of Malaita and Florida between carrier-based aircraft without surface craft firing a shot, the Japanese losses included the carrier Ryujo sunk and another one damaged by Vice-Admiral F. J. Fletcher's force, but the enemy succeeded in landing about 1500 men a few days later on the Guadalcanal beaches. Meanwhile, air and coastwatching intelligence reported a concentration of shipping at Rabaul, evidence that another large-scale landing was imminent. This was planned for the night of 11 October, and from it developed the Battle of Cape Esperance in which American forces under Rear-Admiral Norman Scott defeated a strong enemy force designed to cover a troop landing. Two Japanese destroyers were sunk and the Japanese commander, Rear-Admiral Goto, was killed when his flagship, the Aoba, was damaged. Two more destroyers were sunk the following day while trying to rescue men from the water. A Japanese naval report of this battle recorded that ‘the enemy used radar which enabled them to fire effectively from the first round without the use of searchlights. The future looked bleak for our surface forces, whose forte was night warfare.’

Two nights later, under cover of darkness and rain storms, the Japanese attempted to put Henderson Field out of operation. From close inshore two battleships, the Haruna and the Kongo, poured 918 rounds of armour-piercing and high explosive shells in and around the field while aircraft overhead dropped guiding flares. The following morning, 15 October, only one American bomber and ten fighter aircraft were fit to take the air, and then only after sufficient drums of petrol had been collected from the nearby jungle into which they had been tossed by the bombardment. Only 400 drums could be found. Meanwhile five Japanese transports, protected by eleven warships, could be

seen discharging men and materials at Tassafaronga, ten miles away, and although valiant efforts were made to bomb the ships later in the day, after further supplies of both machines and petrol had been flown in from the New Hebrides, the Japanese succeeded in landing between 3000 and 4000 troops.

This was a critical period for the American command, both on land and sea, for their ground forces were not sufficiently strong to attack on land and naval strength was reduced to one aircraft carrier, one battleship, and a bare complement of destroyers and cruisers. Repairs to the Enterprise were rushed at Pearl Harbour and she was ready for action again by 16 October. Halsey took over command of the South Pacific two days later, at the time when the Japanese were preparing a combined attack on both land and sea. Fortunately this miscarried. The Japanese ground forces attacked along the Matanikau River, where a critical battle raged for some days and culminated in an assault which broke the American line on the night of 23–24 October. It was restored by counter-attack on the 27th and never again broken.

The two opposing fleets joined action on 26 October, 350 miles north-east of Guadalcanal in the Battle of Santa Cruz, in which a Japanese force under Vice-Admiral Nagumo, who had led the attack on Pearl Harbour, met an American task force under Vice-Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, in the carrier Enterprise, who had under command another group commanded by Rear-Admiral G. D. Murray and built round the carrier Hornet. Superior strength lay with the Japanese, whose combined forces included four aircraft carriers, three of which were seriously damaged, four heavy cruisers, four battleships, nine light cruisers and 28 destroyers, operating in three groups, and covering troop and supply transports intended for Guadalcanal.

Although the Japanese did not lose a ship, they withdrew when their carriers were put out of action with the loss of 100 aircraft. The Americans lost their carrier Hornet, sunk after great damage by enemy suicide pilots who crashed their machines into her stack, and the Enterprise was again damaged. During the progress of the battle, which lasted through to 27 October, fourteen enemy submarines patrolled the sea routes between the Santa Cruz, New Hebrides, and the Fiji Groups, hoping to destroy reinforcements of both men and ships.

III: Crucial Action

Although it left the Americans with only one damaged aircraft carrier in the South Pacific, the Battle of Santa Cruz, which the Japanese always insisted in calling ‘Santa Claus’,

definitely affected future operations in the Solomons, for the enemy losses undoubtedly weakened them for the most crucial of all naval battles, the Battle of Guadalcanal, which developed from their last major attempt to reinforce and hold the island. It raged from 11 to 15 November, and on it hung the fate of the Solomons campaign. Had the American navy been defeated Guadalcanal would have been lost, thus altering the whole course of the Pacific war and jeopardising the Allied position in the South Pacific, perhaps for years. Rear-Admiral R. K. Turner reported after the battle on the night of 12–13 November, ‘This desperately fought action ... has few parallels in naval history.... Had this battle not been fought and won, our hold on Guadalcanal would have been gravely endangered.’

While daily air reconnaissance reported the concentration of Japanese naval and transport craft in Rabaul and the anchorages of Southern Bougainville (where more than sixty transport and cargo ships of a vast fleet were assembled), American troops on Guadalcanal, supported by bombardment from surface craft, pressed the enemy back beyond the Matanikau River and off the high features they held inland; but Vandegrift, although strengthened by the arrival of artillery units during the first week of November, urgently required still more men to replace units exhausted by excessive heat and antagonistic country. The decision to send 3 New Zealand Division to New Caledonia to relieve the American Division provided the men required for Guadalcanal. While Halsey was planning to send in these troops, as well as extra supplies, Hyakutake, the Japanese commander, was similarly planning the landing of his 38 Division under strong naval protection, using troop transports instead of the usual destroyers of the Tokyo Express, the schedule of which had been disrupted by 24 United States submarines patrolling along the route. Hyakutake also planned to bombard Henderson Field into impotence so that his disembarkation could proceed without air interference. Halsey's total naval force was still outnumbered by the Japanese, but his air strength was greater. The American command made the first move.

A force commanded by Rear-Admiral Turner, charged by Halsey with the dual task of getting men and supplies ashore and protecting Guadalcanal from expected Japanese attacks, was divided into three groups, one of which he commanded personally. Rear-Admiral Scott and Rear-Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan commanded the other two. A force at Nouméa under Kinkaid, and built round the carrier Enterprise and two battleships, was to support Turner. Scott's group of three transports, one cruiser, and four

destroyers reached Guadalcanal and began unloading men and supplies on 11 November under cover of Callaghan's five cruisers and ten destroyers. Raiding Japanese aircraft interrupted the operations, but they were continued next day when Turner's own group of transports arrived from Nouméa with the American Division. Again the Japanese attacked, but 30 of the 31 attacking aircraft were shot down, though not before the cruiser San Francisco was damaged seriously. These were only the preliminaries of the battle, but they enabled the Americans to get 6000 men ashore and valuable heavy supplies and munitions before the transport and cargo ships retired.

The battle increased in violence in the early hours of the morning of 13 November, when the main forces met as the Japanese battle-ships Hiyei and Kirishima moved inshore to try to bombard Henderson Field. This developed into one of the most furious of all naval engagements of the war, fought out on waters enclosed by Guadalcanal, Savo and Florida Islands, scene of the first naval encounters in the Solomons and surely one of the greatest of all naval graveyards.4 The battle began soon after midnight, when Callaghan's weaker force of 6-inch and 8-inch cruisers joined with Japanese battleships mounting 14-inch guns. In the intense darkness the ships almost collided before a shot was fired, and in the confusion both American and Japanese ships fired on each other. Twelve of the thirteen American ships were either sunk or damaged in the first fifteen minutes, but the American ships concentrated on the Hiyei, which they hit 85 times. She was scuttled next day. Admirals Callaghan and Scott were both killed during the action, but the lighter American ships saved Henderson Field—and the Solomons.

The Japanese withdrew at three o'clock in the morning without firing on the airfield they hoped to destroy. The fact that they

carried high explosive shells for the airfield instead of armour-piercing shells probably saved the situation for the Americans. But this battle was not yet ended.

Despite the fact that Henderson Field was still operating and its strength increased by aeroplanes flown in from the carrier Enterprise, which Kinkaid had brought forward with the battleships Washington and South Dakota, the Japanese still attempted to bring in their transports with men and supplies. These had been sheltering off New Georgia, protected by twelve destroyers, awaiting news of the battle. There were eleven of them carrying 10,000 men of 38 Division, a naval force of between 1000 and 3000, and 10,000 tons of supplies. They were picked up by aircraft 150 miles north of Guadalcanal when they began moving south in the early morning. All that day and until night came down aircraft from Henderson Field bombed up, attacked the transports, and flew back for more bombs to maintain a relentless attack. Aircraft were refuelled by hand and ground crews serviced the planes by rolling bombs across the muddy runways.

By nightfall the invasion fleet had been cut to pieces. Seven of the Japanese transports had been sunk, including the Canberra Maru and the Brisbane Maru. Under cover of darkness that night, however, the four remaining ships continued to the Guadalcanal beaches. Meanwhile Halsey had detached the battleships South Dakota and Washington, and four destroyers from Kinkaid's force, and sent them into the battle under Rear-Admiral Willis A. Lee. Sixteen minutes after midnight, on the morning of 15 November, they joined battle with the Japanese battleship Kirishima, which had returned to the area with cruisers and destroyers to cover the landing of the four remaining transports. An hour later one of the few engagements between battleships in the war ended in favour of the American navy. The heavily damaged Kirishima was scuttled by her crew.

When morning broke clear the four remaining Japanese transports were beached near Tassafaronga Point and were destroyed by aircraft and field artillery. Japanese and American reports estimated that only about 4000 troops reached the shore; 3000 were drowned but some thousands were rescued from the water by Japanese destroyers. Only five tons of supplies reached the shore. In the four-day battle the Japanese lost two battleships, one heavy cruiser, and three destroyers sunk, as well as their eleven transports; two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and six destroyers had been damaged. American losses were serious—one light cruiser, two light anti-aircraft cruisers, and seven destroyers sunk, and one battleship, two heavy cruisers, and four

destroyers damaged, but the American forces on Guadalcanal were never again seriously threatened, and relief troops and supplies were afterwards landed without danger or loss. By the end of November Vandegrift's ground forces numbered 39,416 all ranks.

In one last major action on the night of 30 November, off Tassafaronga, when the Japanese tried to run in six transports under destroyer protection, an American force commanded by Rear-Admiral C. H. Wright suffered grievous loss. Limited visibility was made worse by a completely overcast sky, but in the first phase of the engagement, which began about an hour before midnight, Wright's force had all the advantage, sinking four of the Japanese ships and damaging others. In the second phase the remaining enemy ships launched a devastating torpedo attack before they turned and fled, and in 21 minutes sank the heavy cruiser Northampton and seriously damaged three others—the Minneapolis, Pensacola, and New Orleans—fortunately without realising the great damage they had done.

Minor clashes occurred almost daily between these major engagements, and at times the South Pacific naval forces were reduced to the narrowest margin of safety. At one time in November, Halsey had only four undamaged cargo ships at his disposal to maintain supplies to the battlefront. The situation in New Caledonia was also worrying. Men and supplies poured into that vast base in such quantity that congestion became a problem in itself. At the end of November and in early December, as 3 Division moved in to replace the American Division, there were 91 ships carrying 180,000 tons of cargo waiting to be unloaded in Nouméa Harbour.

Nevertheless, the forces on Guadalcanal were built up, and the Marines who had endured the initial fighting were relieved and sent to New Zealand and Australia to recuperate. On 9 December Major-General Alexander M. Patch took over command from Vandegrift, and soon afterwards all American infantry units were welded into 14 Corps, with which New Zealand ground forces were associated during the Solomons campaign. By that time there were between 40,000 and 45,000 men on the island, and Patch set about planning his offensive to drive the Japanese from such dominating hill features as Mount Austen, the ‘Galloping Horse’, and Gifu strongpoint. The campaign went slowly, due in many instances to the mistaken belief, current during the whole campaign among New Zealanders as well as Americans, that all Japanese snipers fired from treetops, which they did only rarely.

While major clashes at sea held off a Japanese invasion in any strength, small numbers of men and limited quantities of supplies

were wastefully put ashore from submarines at night in what the Japanese called ‘rat’ landings. The garrison in the jungle, reduced by malaria and dysentery, was desperately short of food, but even so resisted stubbornly as the Americans drove them along the coast in an effort to surround them. (See Appendix XII.)

In a miserably conceived plan to get supplies ashore, the Japanese cased their food, ammunition, and materials in drums, lashed them together in rafts and threw them overboard, trusting to the tides to carry them to the beaches, but most of these either stuck to rocks or reefs or were shot up by air and surface craft. By 25 December 1942, of the 6000 Japanese combat troops on Guadalcanal, only 2500 were available as fighting troops, and 30 per cent of those who were capable of walking were employed transporting rations, but the Americans were never certain of enemy dispositions and consequently hesitated in forcing a battle which would have gone in their favour. A report on the campaign by the 17 Japanese Army commander stated that many of the garrison were mentally unfit and that medical treatment was well nigh impossible. By December front-line troops were reduced to an average of .5 ‘go’ of food a day—one ‘go’ being equal to .318 of a pint. Some of the soldiers had no food for a week and were reduced to eating grass, coconuts, and ferns.

America: Four heavy cruisers—Northampton, Astoria, Quincy, Vincennes.

Two anti-aircraft cruisers—Atlanta, Juneau.

Ten destroyers—Jarvis, Barton, Cushing, Laffey, Monsson, Preston, De Haven, Benham, Walke, Duncan.

Australia: One cruiser—Canberra.

New Zealand: One corvette—Moa.

Japan: Two battleships—Hiyei, Kirishima.

Two heavy cruisers—Kurutaka, Kinugasa.

Eight destroyers—Yudachi, Takanami, Natsugomo, Makigumo, Kitusuki, Ayanami, Fubaki, Akatsuki;

as well as an unspecified number of cargo and transport vessels, including four beached at Tassafaronga, and numbers of torpedo boats, landing craft, and aircraft.

The United States forces also lost a number of motor torpedo boats, landing craft, and several cargo boats in this area.

IV: The Japanese Move Back

The growing strength of American naval, ground, and air forces and the withering losses of the campaign, ultimately forced the Japanese High Command to order the evacuation of the island and establish a line which included New Georgia, Kolombangara, Vella Lavella and intervening islands, with Munda as a central pivot. Imperial General Headquarters made the decision on 31 December and issued orders for the evacuation on 4 January 1943 to Hyakutake, who remained on Guadalcanal until early February. Destroyers were employed for the evacuation, with 80 large barges, 100 small barges, and 300 collapsible boats to uplift men and materials from the shore. The first units of 38 Division left the island on the night of 1 February from beaches round Cape Esperance—site of the Japanese base, 25 miles along the coast from Henderson Field; the evacuation was completed by 8 February, by which time 12,000 army and about 1000 naval personnel were moved to concentration areas in Southern Bougainville and the Shortland Islands. According to Japanese records, 3500 of these went into hospital suffering from beri-beri, dysentery, and malaria; 600 of them died.

American intelligence failed to appreciate the Japanese evacuation which, because of the concentration of shipping in anchorages to the north, was mistaken for another attempt to land reinforcements on a large scale. A report made on 17 April 1943 by the American Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet confessed that ‘Not until after all (Japanese) organised forces had been evacuated on 8 February did we realise the purpose of their air and naval dispositions; otherwise, with the strong forces available to us ashore on Guadalcanal and our powerful fleet in the South Pacific, we might have converted the withdrawal into a disastrous rout’. The cautiousness of commanding officers in action for the first time may have been partly responsible for a certain lack of aggressiveness among the men fighting the jungle as well as the Japanese.

Guadalcanal cost the Japanese at least 24,000 officers and men killed in action and lost in sunken ships. Figures gathered from both American and Japanese sources, which are as accurate as any figures of this campaign can be, since most of the enemy records were either lost or destroyed, state that between 36,000 and 37,000 Japanese fought on Guadalcanal between August and the end of December 1942; 14,800 were killed or missing and 9000 died of disease. Of these, 4346 were drowned at sea; 1000 were taken prisoner. Only 2516 of 7648 officers and men from 38 Division who landed on the island returned to bivouac areas in the Shortland Islands. Six hundred aircraft and their pilots were also lost in attempting to hold the island.

The Japanese at first did not appreciate the necessity for a series of intermediate air bases through the Solomons, beginning them hastily only when losses on the 600-mile journey between Rabaul and Guadalcanal weakened their air power. Weather conditions changed so swiftly during this flight that operations were hampered and required drastic changes from the original plans. A seaplane base was therefore established at Rekata, on Santa Isabel; an airfield at Buin, in Southern Bougainville, was ready by 7 October; Munda, in New Georgia, by the end of December; and Vila, on Kolombangara, also in December. By that time, of course, the fate of Guadalcanal was sealed. Ten destroyers used in running the Tokyo Express were sunk and 19 damaged. By comparison American army losses in manpower were light—1752 killed and missing out of a total of 6111 casualties. Navy losses were much more severe. Throughout the whole campaign the Japanese made excessive claims of sinking and damaging American naval craft and of destroying aircraft.

Following the retreat from Guadalcanal to the Central Solomons line, 17 Japanese Army was given the task of defending Bougainville in support of a new line swinging on Munda, where, in February, Rear-Admiral Ota established his headquarters and took command of 5500 navy and army personnel. Ota, who was commander of 8 Fleet Special Unit, was made responsible for all Central Solomons operations, but he had great difficulty in controlling navy and army units, since Army refused to send in any more men. Differences of opinion between army and navy commanders after the withdrawal to New Georgia weakened the Japanese defence plans, and the continual cancellation and reissue of orders by 8 Area Army, which was formed at Rabaul to direct the whole of the Solomons and New Guinea campaigns, produced confusion which destroyed any unity of command.

In March, also, Japanese morale suffered a blow by the loss of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of their Combined Fleet, who was the dominating mind in Japanese naval strategy and originator of the attack on Pearl Harbour. On 18 March he left Rabaul by special aircraft, accompanied by his chief of staff and several senior staff officers and escorted by nine fighters. While on their way to Buin, in the south of Bougainville, where Yamamoto was to inspect both army and navy units and inspire them to further effort, the flight was intercepted by American fighters and the two planes carrying the Commander-in-Chief and his senior staff officers were shot down. Yamamoto was killed when his machine crashed into the jungle; the other machine fell into the sea, injuring all the occupants. Vice-Admiral Kondo took over command of the Combined Fleet until the arrival of Admiral Mineichi Koga, commander of the China Fleet. Through the following months Ota's garrison was increased until, by the end of June, there were 10,500 men in the New Georgia and Kolombangara areas deployed to protect airfields and fleet anchorages, and another 3400 round Rekata seaplane base on Santa Isabel. Early that month he was relieved by Rear-Admiral Noboru Sasaki, whose instructions were to unify and command naval and army forces in all land operations.

Meanwhile American strength was increasing in readiness for an advance into the New Georgia area, with Munda as the next objective. Throughout June, action on sea and in the air paved the way for the landing at Rendova on 30 June. On that and the following day 125 Japanese aircraft were shot down, heartening proof of Allied air superiority. Although the Japanese put up a stout resistance and prolonged the battle for New Georgia for six weeks against 14 Corps, which was forced to commit its three

divisions, the commander of the garrison reported ‘we were overwhelmed by the enemy's material and military strength’. By this time the Americans had reduced disembarkation to a speed which baffled the Japanese, and from then on until the end of the campaign the Japanese were outmanoeuvred. ‘Our losses in men and planes were beyond our estimation’, the Southern Army commander, Terauchi, reported to Tokyo in June.

The Japanese were never able to anticipate the next Allied thrust in the Solomons. After the fall of Guadalcanal, they did not expect the attack to continue to the next objective for at least a year. Although land action in the jungle was slow and laborious, the pressure of naval action at sea was maintained without ceasing. Through the months of preparation by the land forces, strong naval units bombarded at night the Munda and Vila airfields and Japanese installations throughout the area, and shot up barge traffic known to be running between the islands.

The Japanese lost as heavily in attempting to hold and reinforce their garrisons in the New Georgia Group as they did in finally evacuating troops from islands to which they had been driven as Griswold's corps closed round Munda, which fell on 5 August. Fighting, however, continued for another fortnight on adjoining islands of the group. Small groups of reinforcements had reached New Georgia in barges, torpedo boats, and submarine chasers, running in under cover of darkness, and when Munda fell efforts were made to strengthen Kolombangara so that any remaining island garrisons could be maintained from that base.

The final attempt to reinforce Kolombangara on the night of 6–7 August, anniversary of the opening battle for Guadalcanal, ended in complete disaster. Units of 6 and 38 Divisions were despatched from Southern Bougainville under the protection of four destroyers. As they passed into Vella Gulf they were intercepted and taken completely by surprise by an American task force, commanded by Commander Frederick Moosbrugger, which had been ordered to sweep the gulf to disrupt such traffic. In a few minutes three of the enemy destroyers were sunk and the fourth heavily damaged. Most of the reinforcements were drowned—820 army and 700 navy personnel; 190 army and 120 navy survivors reached the shores of Vella Lavella on rafts or by swimming and joined the garrison which had been sent there previously to organise staging bases and lookouts.

That same night Admiral Sasaki, the Munda commander, moved his headquarters back to Vanga Island, and the following night to Kolombangara. On 14 August he was instructed to withdraw

all the Munda garrison, and the following day American forces landed on Vella Lavella. This was the beginning of the by-passing strategy which was continued during the remainder of the Solomons campaign. Remnants of the Japanese forces from New Georgia had concentrated on Arundel and Gizo Islands by 16 August, but as Griswold's forces closed round them they moved piecemeal to Kolombangara by barge, the last units leaving Gizo on the night of 21 September, the day on which 14 Brigade of 3 New Zealand Division began operations to clear Vella Lavella of the enemy.

The loss of Munda and Vella Lavella seriously menaced the Japanese forces on Kolombangara, who were now outflanked, with all their supply routes severed, and Sasaki was instructed to continue his withdrawal to Bougainville, moving via staging bases on Choiseul. On the night of 28–29 September, while 3 New Zealand Division units were forcing the Vella Lavella garrison into the north of the island, 2115 Japanese sick and wounded were uplifted from Kolombangara in three destroyers and taken direct to Rabaul. Small parties continued the evacuation, making their escape at night in barges and torpedo boats, and on the nights of 1–2–3 October the last of the garrison departed—5400 moving in 136 barges and other small craft and 4000 in six destroyers. Twenty-nine barges and torpedo boats were destroyed by American destroyers and motor torpedo boats, but the Japanese records, from which the above figures were taken, state that 12,435 all ranks from Kolombangara and Choiseul reached Buin and Erventa in Bougainville. On the night of 6–7 October the last of the Vella Lavella garrison was uplifted under cover of a naval engagement, which is recorded here merely to emphasise the Japanese propensity for making excessive claims of damage. During this action, fought in the midnight hours north of Vella Lavella in violent rain storms, they claimed to have sunk two American cruisers and three destroyers, whereas only three American destroyers opposed them. (See Chapter 5.)

The loss of New Georgia and Vella Lavella created further strife among Navy and Army leaders concerning future defence strategy and caused the Japanese High Command to modify their Z plan, which was conceived by Yamamoto, and withdraw their vital defence line to the Kurile-Mariana-Caroline Groups. This Z plan originally established an unyielding line for the defence of the Japanese mainland running from the Aleutians through Wake Island, the Marshalls, the Gilberts, Nauru and Ocean Islands, and the Northern Solomons to the Bismarck Group, with the Combined Fleet retained as a mobile reserve to attack any invading force at any place in or on that line. Further modifications became necessary

as this line was broken by successive actions through 1943 and 1944. After the fall of Vella Lavella the Japanese were given no respite. As soon as an airfield was ready at Barakoma, a further thrust was made into the Treasury Group by units of 3 Division supported by American formations. This and a diversionary raid on Choiseul paved the way for a large-scale landing at Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville on 1 November 1943.

Unable to anticipate the next Allied thrust, the Japanese concentrated their main force in areas in Southern Bougainville, with 17 Army Headquarters established near Buin, but despite their numerical strength, in the descriptive language of the soldier, they were never able ‘to take a trick’ during the remainder of the campaign. Ground strength numbered 15,000 troops, mostly from 6 Division, and there were also 6800 base personnel who were employed for the defence of loading installations and the two airfields outside Buin, where Mikawa, commander of 8 Japanese Fleet, also had his headquarters. The airfield on Ballale Island, in Shortland Bay, was also defended by naval units. About 5000 men of 4 South Sea Garrison Unit and a formidable force of coastal and anti-aircraft artillery units were deployed on Shortland Island, only about eighteen miles across the water from Mono Island, where 8 Brigade of 3 New Zealand Division was securely established. There were between 2000 and 3000 troops and naval lookouts in the Gazelle area and another 4000 to 6000 army and 200 navy personnel stationed in the Kieta area, midway along the north-east coast of Bougainville. All these were by-passed when Griswold's 14 Corps landed at Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November, against little opposition but in territory which almost bogged down the landing forces.

Later, in March, when the Japanese moved a strong force through the mountains and launched a determined attack on the perimeter, they were driven off with severe loss. With the occupation of the Green Islands Group by 3 New Zealand Division in February 1944, enemy forces on Bougainville were completely isolated, so that they were forced to maintain themselves by growing their own food or by using native foods. Rice cultivated in large areas was one of the objectives of Allied aircraft operating from the Empress Augusta Bay airfields and they sought daily to destroy it with oil spray and incendiary bombs. The capture of Green Islands on 15 February and of Emirau Island on 20 March 1944 ended the Solomons campaign. New Zealand ground forces were then withdrawn from the forward areas, but air force units remained under American and later Australian command until the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945.

This translated extract from an 8 Area Army order, issued to the commander of 17 Army at the time 3 New Zealand Division occupied Green Islands, is a typical example of the fanaticism which prompted Japanese resistance, though it was not frequently exercised:

If supply should be stopped and there is no alternative but to starve, the troops will charge into the enemy before they are entirely exhausted and, obtaining food from the enemy sources, they will continue fighting up to the very last.

Five days after 3 Division landed on Green Islands, 8 Area Army reported that not one single moveable aeroplane remained to the Japanese command in the South Pacific area; 70 per cent of the remaining ground forces were living in unhealthy conditions in caves to which they were driven by the fury and accuracy of Allied bombing, and 8 Fleet had lost all its ships except a few landing barges. Japanese records compiled by former service staff officers from information available to them and from their own personal documents, gave the following losses of 8 Area Army:

From December 1942 to July 1944: killed in action and died of injuries, 52,684, including 12,679 drowned in sunken ships; died of sickness, 8216; seriously injured, 43,234. At the time of the surrender deaths in action were estimated at 55,379 and deaths from sickness 15,936.

From October 1943 few medical supplies reached elements of the army stationed beyond Rabaul, and when the war ended 17.3 per cent of the total strength was ill, 11.5 per cent of them suffering from malaria.