Chapter 3: Maritime Defence, 1918–1939

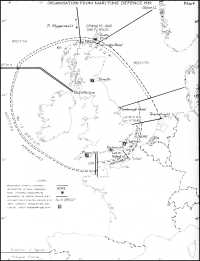

Map 4: Organisation from Maritime Defence 1939

(i)

IN THE last two chapters we have seen that an unfinished scheme of air defence was the only home defence measure of positive importance undertaken during the period of retrenchment which followed the First World War; and that, when rearmament began in 1934, the government of the day rejected a balanced programme in order to make the air defences outwardly impressive. The fact remained that, while air attack was an unpleasant prospect, the British Isles could be effectively occupied only by seaborne troops. The way to military occupation might indeed be opened by air attack; but perhaps a greater danger was severance of the country’s sea communications. Ultimately, as in the First World War, the submarine proved the biggest menace. But for some years the risk of underwater attack was under-estimated, partly because of the success achieved by the convoy system in the last year of the First World War, partly because too much reliance was placed on the device called asdic. Invented in 1917 and in some respects akin to radar, asdic was an apparatus emitting supersonic waves which travelled under water and were reflected by submerged objects such as submarines, whose presence was thus revealed to commanders of escort vessels or shore defences. In the outcome submarine commanders were able to reduce its effectiveness by skilful tactics.

For many years before and even after the First World War the defence of seaborne trade seems to have been generally regarded as a matter of interest only to naval experts. Thus it received little attention outside the Admiralty except on rare occasions when the whole fabric of national and Imperial defence was called in question. On the other hand the prospects of invasion, and measures calculated to avert the danger, were widely canvassed in governmental and official circles during the early part of the present century.1 Discussion revealed many differences on points of detail, but substantial agreement on broader issues. The fundamentals of the problem were found to have changed little since long-range guns were first installed in warships. In the sixteenth century when Spain was the adversary,

two centuries later in the Napoleonic Wars, and again when German naval expansion seemed to threaten invasion across the North Sea, British strategists agreed that the first line of defence must be the main fleet waiting at its war base, or cruising off the enemy’s, to intercept his big ships if they put to sea. The advantages of a counter-offensive against his shore installations or fleets in harbour were admitted, but the circumstances which enabled Drake to ‘singe the King of Spain’s beard’ in 1587 might not be repeated. On all three of the occasions cited, a subsidiary fleet was provided to engage the enemy’s transports and any escort, short of the main fleet, which might sail with them. Again, on all three occasions a second line of defence was present in the shape of the coast defences, comprising on the one hand artillery on shore, on the other such local naval defences as the ‘great Chayne for guarding of the Navye Royall’ installed in 1588 at Upnor below Chatham, and the auxiliary patrols, antisubmarine booms and defensive minefields of modern times. The third fine was the army, normally divided into forward elements stationed near the coast and a strategic reserve to be thrown in when the enemy had shown his hand. During the Napoleonic Wars and later the need for a third line of defence was sometimes questioned; but the arguments on the other side were strong. The case for the third fine was well put by the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1908, when they pointed out that, even though naval supremacy could be assumed, the troops on shore must be sufficient in numbers and organisation not only to repel small raids, but to compel an enemy who contemplated invasion to come with so substantial a force as would make it impossible for him to evade our fleets.2

In a broad sense, the defeat of Germany in 1918 did nothing to invalidate these principles. Conquest of the British Isles by airborne troops alone was perhaps conceivable as a distant prospect; but at least in the near future an invader would still need to bring the bulk of his men and gear by sea. The composition of his transport fleet would depend on the distance he had to come, and to some extent on the season chosen for the venture. In favourable conditions he might make the voyage with special landing-craft of shallow draught, either towed or self-propelled. These, however, would probably need to be followed by normal transports bringing the supplies required to consolidate the landing. An innovation particularly suitable for minor raids or diversionary attacks across the Narrow Waters might take the form of fast motor-boats, also of shallow draught, which would be difficult to intercept. On the other hand new weapons, including torpedo-bomber aircraft and improved warning devices, would doubtless be available to the defenders.

Accordingly there appeared good reason to hope that the well-tried system which had survived the technical advances of the

nineteenth century, if progressively modified to keep pace with new methods of attack, would suffice for many years to come. Developments in naval armament and armour since the beginning of the First World War would call for stronger fixed defences at important harbours liable to bombardment by armoured ships, new measures might be needed to deal with fast motor-boats, and aircraft—which had figured in coast-defence schemes for some years past—might be expected to occupy a more important place in future plans. Moreover, ports considered worth defending against attack from the sea would probably have to be defended against bombing also. But the old principle of three lines of defence seemed likely to hold good, if not for ever, then at least for many years.

Yet in the outcome the reshaping of the country’s maritime defences made little progress before the middle of the 1930s. We have seen that in 1921 a suggestion that the air force should assume the chief responsibility for defence against invasion was soon dropped. Accordingly the burden continued to rest primarily on the navy, although there was no doubt that in war the other services would be expected to assist them. But whereas the army’s task would clearly be to provide a home defence force, including guards for vulnerable points, and to equip and man the fixed defences and certain components of air defence, the contribution likely to be demanded of the air force had yet to be defined. Apart from the responsibility which it assumed in 1922 for air defence, the Air Ministry had the duty of providing squadrons needed for direct co-operation with the army, and for many years provided also those required by the Admiralty for service with the fleet. The Air Staff did not dispute the navy’s claim to such assistance; but the means adopted for the purpose led to some dissatisfaction. While the issues thus called in question remained unsettled, it was perhaps inevitable that little practical attention should be paid to the important problem of the contribution that could be made to maritime defence by shore-based squadrons. Preoccupation with the air defence scheme may also have diverted attention from the matter.

But meanwhile a lack of shore-based squadrons for maritime defence did not prevent their theoretical potentialities from serving as a pretext for the neglect of other weapons. Soon after the Treaty of Washington had modified the relative naval strengths of the powers, the Admiralty drew up a new list of ports at home and abroad which ought, in their opinion, to be protected against a variety of dangers.3 Among the methods of attack to be guarded against were bombardment by capital ships and other warships; penetration or close approach by submarines, light surface craft, blockships and minelayers; air attack; assaults by landing-parties; and bombardment by cross-Channel guns. The list was not based

solely on the hypothesis of war with France, but envisaged the possibility of attack by any one of the four major naval powers. Besides upwards of forty places abroad it included some thirty in the United Kingdom and the Channel Islands, among them the principal naval bases at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Rosyth.

The views of the Admiralty were forthwith considered by a subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Observing that more powerful weapons than the old g-2-inch coast-defence gun would be needed at places liable to long-range bombardment by armoured ships ‘unless or until this function can be relegated to aircraft or some other provision of a permanent nature can be made’, the sub-committee recommended a variety of fixed defences, ranging from guns with a calibre of 12 or 15 inches and firing armour-piercing shells to a range of 40,000 yards, to light automatics capable of dealing with fast motor-boats.4 They also advocated local air defences, particularly against low-flying aircraft; infantry garrisons and mobile reserves to round up landing-parties; and measures of local naval defence, including offshore patrols by submarines and trawlers, mine-sweeping, booms, nets, detecting devices, smoke-screens, and an organisation for regulating traffic into defended ports, the whole supported by aircraft for reconnaissance and local counter-attack. Aircraft would be needed also as spotters for the fixed defences, but might be supplemented or in some cases replaced in that capacity by kite-balloons.

Outwardly at least, these recommendations embodied the agreed views of the experts nominated by their respective services, and could therefore be expected to command assent from all three of the ministries concerned. But in fact the memorandum which contained them had a stormy passage. Early in March 1923, the Standing Defence Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence dictated minor alterations which stressed the difficulty of laying down any general rule as to the need for long-range guns at places liable to bombardment by armoured ships.5 A few months later the Admiralty suggested two further amendments, one emphasising the limitations of the submarine as a defensive weapon, the other accepting a diminished standard of security at some ports liable to attack by cruisers.6 With the approval of the Standing Sub-Committee, these changes were incorporated in July. But the War Office, faced with a restricted budget, shrank from the prospect of heavy expenditure on the fixed defences, while the Air Staff were still not satisfied that the case for replacing guns by aircraft had been sympathetically considered. Accordingly, in December the newly-created Chiefs of Staff Committee asked the Committee of Imperial Defence to agree that the whole matter should be reopened in order that the respective staffs might consider what economies could be made by revising the

fist of ports to be defended, and either altering the scales of defence at certain places or postponing their completion until a crisis became imminent.7 The Chiefs of Staff asked, too, that where home ports were concerned account should be taken of the help which might be given by such units of the home defence air force as happened to be stationed near them. Despite some obvious objections—for the home defence air force had responsibilities of its own, and neither aircraft which might be needed for other duties, nor paper schemes which promised security at the eleventh hour, were proper substitutes for the ‘permanent works, established in quiet moments on sound principles’ of Mahan’s dictum—the Committee of Imperial Defence agreed in January 1924, that further consideration should be given to these questions.8

The effect was to postpone for many years an issue which might have been faced in 1922. In November 1927, a fresh sub-committee, pointing out that ‘air units will not normally be located specifically for the defence of ports’ and that no special type of aircraft for maritime reconnaissance was in view, reported that fixed defences and measures of local naval defence and air defence on the lines suggested five years earlier were still required.9 In the same month they made detailed recommendations for the local defence of fifteen home ports on the hypothesis of war with France, and mentioned another twelve which either would or might be needed as naval harbours in time of war.10 Of the twenty-seven places listed, twenty-three seemed sufficiently important to justify the installation of ‘adequate defences’ in time of peace; for the other four only paper schemes were thought necessary until war broke out. As the outcome showed, with few exceptions adequate defences at the places proposed would be at least equally valuable if the potential enemy were not France but Germany.

In the circumstances envisaged, home ports seemed unlikely to be bombarded at long range by armoured ships. Accordingly no guns larger than 9-2-inch were recommended. The fixed defences proposed at the fifteen ports considered in the first instance, as compared with those existing, totalled:

| Existing Totals | Proposed Totals | |

| 12-inch guns | 4 | – |

| 9.2-inch guns | 55 | 35 |

| 6-inch guns | 109 | 78 |

| 4-7-inch guns | 4.1 | 13 |

| 4-inch guns | 16 | – |

| 12-pounder guns | 96 | – |

| 6-pounder guns | – | 27 |

| Lights | 179 | 122 |

Thus the proposals involved a net decrease of no less than 168 guns, including 55 of 6-inch calibre or larger, and 57 lights. Nevertheless their financial implications were not such as to command ready support from authorities eager to save money. The initial cost of re-siting and modifying the guns was estimated at more than a million and a quarter pounds, and local naval defences would absorb the best part of another million. Against these figures could be set such sums as might accrue from the sale of abandoned sites and surplus armament. During the next twenty-seven months consideration of the needs of the remaining ports on the list brought the number of schemes to twenty-six and the estimated cost to rather more than two-and-a-half million pounds, these figures including about a million for local naval defences.*

These schemes were only part of a more comprehensive series covering the Empire as a whole. In the aggregate the financial implications were formidable, especially as some ports abroad were liable to heavier attacks than those at home and therefore needed more far-reaching systems of defence. A notable example was Singapore, where the programme approved in 1928 included three 15-inch, four 9.2-inch and four 6-inch guns.11 Other obstacles were the assumption that there would be no major war for ten years, and the perennial controversy about the respective merits of aircraft and big guns.12 For all these reasons little was done within the next few years to implement the schemes. When the Shanghai incident of 1932 revealed the bankruptcy of a Far Eastern strategy not backed by secure bases, the Ministerial Committee appointed to examine the whole problem of coast defence were thus forced to acknowledge that ‘the whole of the coast defences of the Empire at home and abroad are obsolete and out-ranged by the guns of a modern cruiser armed with 6-inch ordnance.13 The plight of the home ports was substantially no better two years later, when the Defence Requirements Committee, naming Germany as the potential enemy, observed that the coast defences at home were ‘completely out of date’ and would have to be revised as Germany developed her sea-power.14

* The places considered were:

1927: Berehaven; Portsmouth and Southampton; Plymouth; Harwich; the Thames; the Medway; the Forth; Milford Haven; the Mersey; the Humber; the Clyde; the Tyne; the Tees and Hartlepool; Lough Swilly; Queenstown. (Schemers 1-15.)

1929: Portland; Dover; Belfast; Swansea; Barry; Cardiff; Avonmouth and Newport. (Schemes 16-22.)

1930: Falmouth; Newhaven; Barrow-in-Furness; Scapa Flow. The needs of the Tay and Aberdeen were also considered, but no defences were recommended. (Schemes 23-26 and Scheme 27.)

(ii)

When the Joint Oversea and Home Defence Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence remarked in 1927 that air units would not ‘normally be located specifically for the defence of ports’, they were thinking mainly of attack from the air. But the observation was equally true of defence against attack by sea. Despite the claims advanced for aircraft as weapons of maritime defence, the air force was in no position to make a major contribution to that branch of strategy, except insofar as it provided a few squadrons for service with the navy.* Theoretically, the bomber force was equally capable of attacking objectives on sea or land; in practice, it was not adequately trained or organised for war at sea, and in any case was likely to be fully occupied with the offensive aspect of air defence and in providing such bomber-support as might be needed by the army. Moreover the air force lacked means of maritime reconnaissance from shore bases, and thus the power of locating hostile naval forces as an essential preliminary to their engagement by shore-based bombers. In 1934 the only shore-based flying units at the disposal of the command called Coastal Area—whose main task was the administration and training of Fleet Air Arm units—were four squadrons equipped with flying-boats.15 These might be used for maritime reconnaissance. But as radiolocation had not yet been invented, they were likely to be needed also for giving warning of impending air raids.

Expansion Scheme A, adopted in that year, proposed the addition of four general-purpose (later called general-reconnaissance) squadrons to the home-based air force; but the precise role of the new squadrons had yet to be determined. Under Expansion Scheme C, which followed in 1935, as also under Scheme F of 1936, the number rose to seven. With six flying-boat squadrons instead of four, the new Coastal Command which replaced Coastal Area in the latter year would thus have thirteen shore-based squadrons of its own. Two shore-based torpedo-bomber squadrons were also included in its establishment, but at that time were intended to go under Bomber Command in time of war. For the time being Coastal Command retained its predecessor’s responsibilities towards the Fleet Air Arm, whose strength was fixed under the respective expansion schemes at 16½, 16½ and 26 squadrons, rising to 40 squadrons by 1942.

* When rearmament began in 1934 the Fleet Air Arm, as it was then called, comprised six fleet reconnaissance, fighter and torpedo-bomber squadrons in the carriers Courageous and Glorious, one torpedo-bomber squadron disembarked at Gosport, and four flights divided equally between the capital-ships and cruisers of the Home Fleet and cruisers based on overseas stations.

But much ground had yet to be covered before the organisation and functions of the new command were settled. An early scheme envisaged devolution to three groups responsible respectively for flying-boats, general-reconnaissance squadrons and training, besides the equivalent of a fourth group concerned with the Fleet Air Arm. A serious objection to such a purely functional arrangement was that, if either the flying-boats or the general-reconnaissance squadrons, or both, were used for maritime defence, the authorities in charge of them would need to be in close touch, and preferably in physical proximity, with the home commands of the navy at Plymouth, Portsmouth, Chatham and Rosyth.

For some time, however, the Air Ministry were unwilling to agree that maritime defence should necessarily have first call on the coastal squadrons.16 The strategic argument for their case was that, while in certain circumstances maritime defence might be the right task for the squadrons, in others they might be needed to swell the effort of the bomber force. Another reason for the Air Staff’s attitude was that, as long as the status of the Fleet Air Arm remained a controversial issue, they were wary of concessions which might pave the way to annexation of the new command by another service.17

As the threat of war with Germany took shape, the Air Staff’s case became less tenable. Attempted invasion seemed unlikely, but attacks on seaborne trade were almost certain. That trade-defence would call for shore-based aircraft in substantial numbers, no matter how other phases of the air war might develop, could scarcely be denied. Somewhat paradoxically, the difficulty became less troublesome in the summer of 1937 when the Government, on the advice of the Minister for Co-ordination of Defence, decided to transfer the Fleet Air Arm, lock, stock and barrel, to the Admiralty.18 Apparently satisfied that their loss of what had long been a bone of contention would at least ensure their continued control of the coastal shore-based squadrons, the Air Staff had henceforward less reason to stand on principle, and grew more amenable to arguments founded on necessity. Thereafter understanding between Coastal Command and the navy became so close that when, in 1941, the course of the war required that the Admiralty should take operational control of the command, the change did little more than recognise an existing situation which had grown up with the active concurrence of both partners.

At the beginning of December 1937, the Air Ministry agreed at last that the primary role of Coastal Command in war should be ‘trade-protection, reconnaissance and co-operation with the Royal Navy.19 Progress thereafter was reasonably rapid. Study of the problems likely to arise in a war with Germany, especially in the light of an exercise held that summer, showed that practical needs could best be met by organising the command on a geographical basis and

locating its group headquarters at places where naval, air and possibly also army commanders could control their respective forces from joint operations rooms with the help of integrated staffs. Apart from the Home Fleet and its ancillary forces, the naval organisation for maritime defence in home waters would consist of four commands. These were the Western Approaches Command (headquarters Plymouth) ; the Portsmouth Command (headquarters Portsmouth); the Nore Command (headquarters Chatham); and the Coast of Scotland or Rosyth Command (headquarters Rosyth).* The obvious locations for the headquarters of the three coastal groups at present contemplated were Plymouth, Chatham and Rosyth. The headquarters of the army Commanders-in-Chief—in time of war responsible to the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces—could not conveniently be moved to the coast, but ultimately it was found sufficient that they should be represented by liaison officers. The name Area Combined Headquarters was coined for the joint centres ultimately set up.

The new system was tried out in a combined coast-defence and trade-protection exercise held in the summer of 1938. Temporary combined headquarters at Rosyth were shared by the local naval Commander-in-Chief and the Air Officer Commanding No. 18 Group—a future coastal group whose formation was anticipated for the purpose. Similarly at Chatham the Commander-in-Chief, The Nore, shared temporary combined headquarters with the Air Officer Commanding No. 16 Group—a coastal group already formed but based normally at Lee-on-Solent. Fortress Combined Headquarters (later called Combined Defence Headquarters) were established at the Forth, the Tyne, Harwich and the Thames and Medway to control the local defences at those places. For the purpose of the exercise, Headquarters, Coastal Command (in fact located also at Lee-on-Solent) were deemed to be ‘near London’, and Air Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, issued orders to his groups from the Admiralty War Room in Whitehall. Naval and air forces which took part on the defending side included two cruisers and four destroyers (representing nine capital ships, fifteen six-inch cruisers and eight destroyer flotillas) under the ultimate control of the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff; eight general-reconnaissance squadrons (this category now including flying-boats) and two torpedo-bomber squadrons under Coastal Command; four fighter squadrons controlled by No. 11 (Fighter) Group at Uxbridge; and six coast-artillery co-operation aircraft for artillery reconnaissance. The attacking force comprised the bulk of the Home Fleet and the Fleet Air Arm. The exercise confirmed the usefulness of the integrated system, and Area Combined Headquarters were accordingly

* See Map 4. The map shows also the Orkney and Shetland Sub-Command (under a Flag Officer responsible to the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet).

established at Mount Batten (Plymouth), Chatham and Donibristle (Rosyth).20 Nos. 16 and 18 Group moved to Chatham and Donibristle respectively in November; in the following summer No. 15 Group, formed later than the others, took up its position at Mount Batten. Headquarters, Coastal Command, moved in August 1939, from Lee-on-Solent to Northwood in Middlesex. As ‘chief adviser to the Admiralty and Air Ministry on all home air operations involving naval co-operation’, the Commander-in-Chief occupied a position of exceptional responsibility towards his own service and towards the navy.

Meanwhile detailed plans were taking shape. In devising them the Naval and Air Staffs had to reckon with two alternatives, namely war with Japan and Germany at the same time, or war with Germany alone. Here only the second need be considered. In the Admiralty’s opinion Germany, with her small surface fleet, was unlikely to attempt invasion (though the risk of small raids could never be entirely excluded), but extremely likely to attack the seaborne trade on which the British Isles depended for a great part of their sustenance.21 Apart from the risk of air attack and mining, attacks on seaborne trade might be made by submarines or surface raiders, or by both, and might or might not be restricted by considerations of humanity and international law. The Naval Staff believed that submarines were the lesser danger, for a system of convoys escorted by aircraft and by ships equipped with asdic was expected to go far to make them ineffective. If unrestricted attacks by submarines began, such a system would be at once put into force. Ships bound for the United Kingdom would be formed into groups at distant ports, and on entering the danger area would be met by escorts. Outgoing traffic would leave in convoy, but the convoys would break up south of Ireland. In addition, local convoys would be run between United Kingdom ports. In 1937 the forces needed for convoy escort were estimated at seven special anti-aircraft vessels, 107 escort vessels of various kinds and 165 shore-based aircraft.22 Before the introduction of the convoy system, or if it proved unnecessary, the aircraft would co-operate with ships in a general offensive against submarines.

The Admiralty’s biggest fear, however, was lest surface raiders, which might be either warships or converted merchantmen, should break out of the Narrow Waters.23 Having once gained the Atlantic, they could be rounded up only by an extravagant dispersal of naval effort, and meanwhile might do an immense amount of damage. Accordingly the Naval and Air Staffs were much exercised by the problem of preventing such excursions. The main features of the system they devised were a minefield and a system of naval patrols covering the southern exit from the North Sea through the Straits of Dover, coupled with measures designed to block the wider exit to the

north. For the second and more difficult task they relied mainly on air reconnaissance, supplemented by submarine patrols to cover an area which existing general-reconnaissance aircraft could not reach.

The number of shore-based aircraft needed to maintain daylight patrols over the North Sea between Scotland and Norway was estimated at 84, and another twelve were required for co-operation with the naval Northern Patrol designed to control the passage of contraband through the waters between Iceland and the Faeroes.24 The total number of shore-based aircraft needed for maritime defence was thus 261. The nominal establishment of Coastal Command on the eve of the war (including torpedo-bomber squadrons) was only three short of that figure, although in practice the average number available for active use during the first fortnight of hostilities was about 170.25 And a substantial deficiency in escort vessels could be expected in the early stages of the war if the convoy system was put into effect at once.

An easily foreseeable weakness of the scheme was the short range of the Anson aircraft with which most of the general-reconnaissance squadrons were equipped. In many ways an admirable machine, the Anson was limited to an effective radius of about 250 miles, and could carry only a small bomb-load. The more modern aircraft intended to replace it were not yet ready. In the summer of 1938 the Air Ministry found a substitute with about twice the effective range and five times the bomb-load of the Anson in the American Lockheed B.14, known in the United Kingdom as the Hudson. Re-equipment of the general-reconnaissance squadrons with the Hudson began in 1939, but by September only one of them had its new aircraft.26 Hence some time was likely to elapse before the submarines temporarily included in the system of North Sea reconnaissance could be replaced by aircraft. In the flying-boat squadrons, too, the modern Sunderland was only just beginning to replace the older London and Stranraer; while the shore-based torpedo-bomber squadrons had nothing but the Vildebeeste IV, an obsolescent aircraft with a cruising-speed of only eighty knots.

In due course experience revealed other weaknesses in the maritime defences; but most of them will be more conveniently discussed in later chapters. One important shortcoming was, however, evident well before the outbreak of war and calls accordingly for mention here. This was the absence of adequate protection for merchant shipping against air attack. By diverting a proportion of traffic from the East Coast to the West, where German bombers were less likely to penetrate, the Admiralty hoped to reduce the danger. But complete diversion was impossible. Even if all ocean traffic were taken to the West Coast, local coastwise traffic to the East Coast ports, including

London, would still be necessary to avoid an intolerable strain on the railways. Anti-aircraft fire from escort vessels, although a method much favoured by the Admiralty, could never give complete protection; while aircraft of Coastal Command assigned to convoy-escort would be busy searching for submarines ahead of the ships they were guarding and could not be expected to deal with bombers too. If convoy was not in force, machines engaged in a general offensive against submarines would be in a still less favourable position to guard individual vessels from air attack. Arming of all merchant ships with short-range anti-aircraft weapons was an ideal which could not be realised until many more such weapons had been produced, and even then would not protect them against high-level bombing. An inter-service committee appointed to consider a rather different aspect of bombing at sea thus pointed to a very real danger when they warned the Government early in 1939 that the problem of defending merchant shipping was still unsolved.27

The Committee of Imperial Defence responded by suggesting more drastic diversion of traffic to West Coast ports; but about a month before the outbreak of war they went further by sanctioning the formation of four long-range fighter squadrons for the express purpose of escorting shipping in particularly dangerous areas between Southampton and the Forth.28 On grounds of expediency rather than of principle, the Air Ministry proposed to allot them, not to Coastal Command as the air formation normally concerned with shipping, but to Fighter Command as that concerned with fighters. The innovation was unlikely to appeal to Fighter Command, whose organisation and methods of control were largely designed for the very purpose of avoiding the standing patrols which shipping escort would entail. The ‘trade-protection squadrons’, as they were called, were not expected to be ready before 1940. In practice the seriousness of the threat to shipping forced the Air Ministry to form them in October, 1939. They were equipped with Blenheims.

A radical weakness of the trade-protection squadrons was that they were inadequate in numbers and equipment for the task in view. When war began, experience soon showed that by far the most acceptable safeguard for ships in coastal waters was that given by single-engined fighters, whose employment for such a purpose had not at first been seriously contemplated. Originally Fighter Command’s province ended some five miles from the coast, for beyond that distance pilots could not count on hearing orders from the stations which normally controlled their movements. In 1939 and 1940 the gradual replacement of existing radio equipment by new sets of longer range extended the distance to. about forty miles. We shall see in later chapters that, as the war went on, the fighter force found itself charged with an unlooked-for and by no means welcome

responsibility towards shipping within that limit, often in defiance of its cherished principle that standing patrols were to be avoided.

(iii)

Meanwhile the naming of Germany as the ‘ultimate potential enemy’ had aroused the long-dormant problem of the coast defences. Observing in 1934 that, with few exceptions, ‘the gun defences of the Empire have not been modernised for nearly thirty years’, the Defence Requirements Committee put the sum required to make the fixed defences of home ports reasonably efficient at approximately four million pounds—more than twice the estimates of 1927–1930.29 In view of Germany’s small surface strength they did not suggest that the whole amount should be spent at once, but recommended a modest annual expenditure of a hundred thousand pounds for the next five years. In their opinion the first essential was to make the existing armament fit for war and to complete the close defence of the main naval ports and the Thames. More drastic changes, designed to furnish North Sea ports with effective counter-bombardment weapons, could follow later. On the other hand they attached great importance to the early provision of local naval defences, particularly against submarines. Their view was that ‘as regards our home ports, it would be folly, in view of a probable development of the German navy, to leave places of such immense importance without any seaward defences whatever and completely open to submarine attack’. To meet this need at fifteen of the most important places at home and abroad they proposed an annual expenditure of £125,000 for the next five years.

In the outcome, financial limitations mutilated these proposals, and led in 1940 to improvisations undertaken in conditions far removed from the studious atmosphere conducive to prudent investment in weapons designed to serve a long-term purpose. On the advice of the Ministerial Committee which examined the Defence Requirement Committee’s report the allotment to the fixed defences was cut down by three-quarters.30 Consequently the efforts of the authorities concerned with coast defence were largely devoted, during the remaining years of peace, to the preparation of local naval defence schemes and the provision—within the means available—of equipment needed to give effect to them. Little could be done for the fixed defences except to put them into a position to fight with their existing armament, and if necessary with old-fashioned ammunition.

When the Defence Requirements Committee made their report in 1934, preparation of a new series of schemes, superseding those of 1927–1930 had recently begun. The process continued up to and

after the outbreak of war In August 1939, the ports at which defences were considered necessary numbered twenty-eight, as compared with the twenty-six of 192 7-1930; but a number in Eire were no longer included in the list, the right to fortify and use them having been renounced. At nineteen of the twenty-eight, installation of the defences in time of peace was planned at least in theory; at the other nine—of which four might not have to be defended—installation after the outbreak of war was deemed sufficient.31 The unlikelihood that local seaward defences could in fact be perfected in peacetime was acknowledged; it was recognised that practical considerations would probably prevent the finishing touches from being given at most places until war was declared.32 Before discussing the outcome, we must turn to the progress made meanwhile in other branches of home defence.