Chapter 20: The Dwindling Threat (The German Air Offensive 1942–1943)*

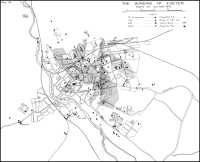

Map 28: The Bombing of Exeter, Night of 3rd May 1942

IN THE last two chapters we have watched the effect on the home defences of the attacks on sea communications near the British Isles which overlapped and followed the main air offensive against United Kingdom cities. We have seen that the number of ships sunk by air attack in coastal waters rose alarmingly in the spring and early summer of 1941, but afterwards declined as counter-measures took effect. We have seen, too, how the fear of invasion persisted for about two years after the crisis of 1940, but by the autumn of 1942 was so far overcome that the Chiefs of Staff discounted a landing in the following year; and how by the autumn of 1943 the danger seemed so slight that they then agreed to a substantial reduction of the coast defences. The story of German air operations against the United Kingdom was, however, carried only to the end of 1941 and must now be continued from that point.

Within six months of the opening of the campaign in Russia the few German bomber units remaining in the west had fallen on hard times. Their aircraft were far from numerous and—like the German bomber force in general—were no longer in the forefront of design. Attacks on coastal shipping had paid well for a time, but ultimately heavy losses in daylight made even night attacks seem less attractive, especially as the bomber was plainly losing its former immunity from interference by the night defences. Perceiving perhaps more clearly than their superiors that Britain’s weak spot was her dependence on sea communications, the officers immediately responsible were still eager to continue minelaying and attacks on ports and shipping; but only meagre support could be expected from a High Command preoccupied with other theatres. For Hitler, whose energies were largely absorbed by the campaign in Russia, the Western Front had become a sideshow. Moreover, while the British Bomber Command remained outwardly content with relatively light attacks and while Luftflotte 3 was incapable of striking crippling blows, he was reluctant to provoke reprisals by ordering resumption of major raids.1

* For statistical summaries, see Appendices 37-39.

On the other hand, the fighter force in France and the Low-Countries was fairly strong. Recovering quickly from losses sustained at the height of the British day offensive, by the autumn of 1941 it had a higher proportion of serviceable aircraft to actual strength than in the early summer.2 Its pilots knew or guessed that British claims were far too sanguine; for the most part its leaders were undismayed by minor damage done to French factories and power-stations in daylight raids. Moreover the new Focke-Wulf 190, although not entirely satisfactory or outstandingly successful when it first appeared, was in many ways a better fighter than anything the British Fighter Command could yet put into the air. New versions of the Messerschmitt 109, considered by some German critics superior to the Focke-Wulf 190, were also in production or on the way.

On Christmas Day two German fighters flew low across the Channel to the neighbourhood of Hastings, opened fire on some buildings a few miles to the east, and then made off. Much the same thing happened on Boxing Day, on the first day of the New Year and on several other occasions in January. These operations foreshadowed a growing tendency to call in the fighter to atone for the absence of the fast, self-sufficient bomber towards which German strategic thought had always leaned.3 In the early months of 1942 a fighter-bomber unit—soon expanded to two squadrons—was added to Luftflotte 3’s resources.4 Unlike the occasional fighter-bomber pilots of 1940 and 1941, who had dropped their bombs from great heights with little attempt at accuracy, its men were trained to fly low so as to baffle the defences and to bomb specific targets with some care. A few months earlier the Royal Air Force had adopted the fighter-bomber as an anti-shipping weapon; both sides were exploring its effectiveness against armoured fighting vehicles and other battlefield targets. Meanwhile, for the German air force in the west it proved a useful weapon against seaside towns, where well-defined objectives like gasometers, rather than purely residential districts, were the usual points of aim in 1942.

From the end of March the sudden appearance of small formations of fast-moving aircraft which dropped a few bombs before retreating became a familiar hazard in such places as Brighton, Worthing and Torquay. In late March and early April raids by fighter-bombers were made at the rate of two or three a week. At night, minelaying expeditions to the Thames and Humber were interspersed with small attacks by the depleted bomber force on Dover, Portland and Weymouth. To the defences the day raids were a nuisance, the night attacks in no way remarkable. Indeed such night attacks, coupled with armed reconnaissance of shipping, had been a commonplace occurrence for months past. Neither by day nor at night did the bombing do much damage, and in March not more than about a

score of civilians were killed by air raids in the whole of the United Kingdom. Similarly the British air force had barely got into its stride, so that to many people both in England and in Germany the war in the air appeared to have settled down to an exchange of minor blows.

These illusions were shattered on the night of 28th March, when Bomber Command sent 234 aircraft to the Hanseatic port of Lübeck to try out a new system of fire-raising. The beautiful old city, almost undefended, burned like matchwood. The incident caused much resentment in Germany and seems to have made a deep impression on the Fuhrer. Abandoning his policy of non-provocation, he ordered that air warfare against England should be given a more aggressive stamp.5 On 14th April he sanctioned raids on targets where attacks were likely to have the greatest possible effect on civilian life and called them frankly ‘terror-attacks (Terrorangriffe) of a retaliatory nature’.* At the request of the German Naval Staff the original plan of substituting such raids for attacks on ports and shipping was modified and minelaying was sacrificed instead. Later Hitler conceded that minelaying might continue when it did not conflict with the main programme.6 But as raids of any size could be undertaken only if both anti-shipping and minelaying units took part in them, neither concession was worth much in practice.

When the new order was promulgated the fighter-bomber force mustered rather more than thirty aircraft, of which about five-sixths were serviceable.7 The bomber force, with the help of anti-shipping, minelaying and reserve training units and by dint of double sorties, succeeded on one night towards the end of April in (carrying more than two hundred tons of bombs across the Channel.8 Reinforced a few days later by two Gruppen withdrawn from Sicily—a significant move at the height of the attack on Malta—it was able in May and June to aim some 1,500 tons at places chosen largely for their aesthetic interest and their lack of strong local defences.

The ‘Baedeker’ raids, as both sides soon learned to call them, began on the night of 23rd April with a modest effort by units diverted, as the Fuhrer had decreed, from their usual task of laying mines. The primary target was Exeter, but few crews found their way to it and only one stick of bombs fell within the bounds of the city. A second attack the next night was rather more successful; but only about a sixth of the tonnage which German crews supposed they had aimed at Exeter on the two nights found its mark. The moon was up and there was no balloon barrage to hamper low flying, although guns

* The German text of the order is given with a translation in Appendix 36. Contrary to the general belief, the term Terrorangriffe seems not to have been applied, at any rate officially, to earlier raids on Warsaw and Rotterdam, which were at least ostensibly regarded by the Germans as operations in support of troops.

and fighters were in action; yet most crews bombed cautiously from heights between 5,000 and 15,000 feet.

Attacks on the next two nights were notably heavier and far more destructive. Bath was the primary target on both occasions, although on the first night about ten tons of bombs hit Bristol. The German effort—about two hundred and fifty sorties all told—was small by the standards of 1940–1941, but no inconsiderable achievement in the circumstances. Unprotected by balloons or heavy anti-aircraft batteries and lying in a hollow which aggravated the effects of blast, the place made an easy and rewarding target. Crews came low in the bright moonlight, sometimes to 600 feet or so, and dropped their bombs at leisure. According to eye-witnesses, some crews hampered Civil Defence workers by opening fire with machine-guns. Early on the first night a direct hit set fire to the gasworks; to add to the difficulties of the defenders, the Civil Defence Control Room was also hit. On the second night a high wind and low water-pressure created a grave problem. In the outcome damage by fire was less severe than at one time seemed likely, mainly because few incendiaries struck the most vulnerable part of the old town; but high-explosive bombs and the blast they caused blew many gaps in rows of Regency houses, agreeable to the eye but not very solidly constructed. Authorities in London drew attention to an apparent improvement in the German aim since 1941, but pointed out that the success of the two raids was manifestly due largely, if not entirely, to the choice of target.

Similar methods at Norwich, York and again at Norwich on the next three nights brought even better results (from the German viewpoint) in terms of the proportion of the tonnage aimed which hit the target. At both places, but especially at York, incendiaries played a more effective part than at Bath. In the first raid on Norwich an acute shortage of water followed early hits on mains: thereafter twenty factories and many other buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged. At York dense clusters of incendiaries fell north and south of the Minster and straddled railway lines to north and northwest; high-explosive bombs, of which about fifty tons were counted within the city, were closely concentrated in the central and northern quarters.

Statistically the attack on York was the most accurate of the whole ‘Baedeker’ series; the first attack on Norwich was a close second. But the most devastating of the raids had yet to come. On the night of 3rd May the Luftwaffe returned to finish the job half done at Exeter; and this time no mistake was made. (See Map 28.) The night was fine and almost cloudless; in clear moonlight visibility was excellent. Arriving over their objective about two hours after midnight, the leading bombers marked the target with flares and a shower of incendiaries, all dropped in the space of about ten minutes. In the next

three-quarters of an hour further waves dropped on the city some fifty tons of high-explosive and many thousands of incendiaries, weighing about twelve tons. Other crews, more cautious or less skilful, released a substantial load outside its borders. For forty minutes, beginning about half an hour after the arrival of the leading bombers, aircraft of No. 10 Group patrolled in layers over Exeter, but neither they nor the guns which opened fire earlier could prevent the enemy from coming low to bomb at point-blank range. The outcome was bound to be disastrous to a city whose layout made it particularly vulnerable. With its core of mediaeval buildings, its narrow streets of shops stocked with highly combustible materials, the centre of Exeter was regarded by experts as more susceptible to fire than any other urban area in the country, except possibly Chester and a small part of the City of London which had succumbed in 1940. Within a short time a great part of it was gutted by a conflagration with which the fire services could not cope. The cathedral, with many other buildings, was seriously damaged.

Fortunately the Germans did not repeat the success achieved in April and on Exeter’s unhappy night in early May. On 4th May an attack on Cowes—apparently chosen for its factories and shipyards rather than its appeal to the tourist—was reasonably successful; thereafter almost everything went wrong for the attackers. An ill-advised attempt to complete the discomfiture of Norwich on the 8th without the aid of moonlight failed badly. At the beginning of the raid a flare dropped near a decoy-site well outside the city kindled a fire which acted as a beacon for many crews, so that roughly half the load intended for Norwich fell in that neighbourhood, fortunately without disaster to a radar-station close by. Less than two tons fell inside the boundary and none in the built-up portion of the city. A balloon-barrage installed since the end of April had little chance to prove its worth, although probably at least one bomber collided with it.

The next few raids were only slightly more successful. Hull was saved on 19th May by a fire kindled by incendiaries on an antiaircraft site outside the city boundary; at Poole a few nights later a decoy-fire lit by the defences was notably successful. Indeed, so well did it play its part that many crews came low to bomb it without detecting the imposture. And at Grimsby on the 29th rain and thick clouds so confused the enemy that not one bomb hit the target.

The month closed with an attack on Canterbury, intended as a reply to Bomber Command’s big raid on Cologne the night before. But whereas more than a thousand British aircraft had been sent to bomb Cologne, the Luftwaffe mustered only some eighty or ninety crews for their reprisal. German reports of a later raid on Canterbury, when crews claimed ‘two direct hits on the cathedral and

one near miss’, suggest that on this occasion, too, some crews may have aimed deliberately at a building wholly unconnected with Canterbury’s position as the strong garrison town and grain-marketing centre’ of the German communique. Some windows of the cathedral were damaged by blast; eight small incendiary-bombs went through the roof but burned out harmlessly on the floor below. The old quarter of the city with its mediaeval buildings suffered heavily, though less disastrously than its counterpart at Exeter, in a conflagration covering about six acres.

The ‘Baedeker’ offensive was now almost over. By choosing easy targets and making the best use of a few experienced crews to blaze the trail for the rest, the Luftwaffe had achieved on six or seven nights a relatively better concentration of bombs than in the summer of 1941. The attackers had, however, lost some forty aircraft in the fourteen notable operations undertaken since the first raid on Exeter. Many of their losses were due to inexperience; in particular, reserve training units had suffered heavily. Göring and his staff may well have wondered whether the price was not too great for an offensive which served no clear strategic purpose. At any rate, Luftflotte 3 soon modified the scale and direction of its attack, devoting more of its effort to places of some industrial or maritime value and less to those of purely aesthetic interest. Ipswich, Poole, Southampton, Birmingham and Middlesbrough were the chief targets for the next eight weeks; Canterbury, attacked twice in June, and Norwich, also attacked again although the Germans claimed to have reduced it to an ‘enormous heap of ruins’ in their unsuccessful May attack, drew much smaller forces than those used earlier.

By this change of emphasis the Luftwaffe may have satisfied its critics, but clearly did nothing to improve its chances. Southampton and Birmingham were well-defended targets; and a Midland city was not as easily found as Bath or Exeter. Hampered by bad weather, the crews despatched to Birmingham on 24th June went far astray, so that not one bomb hit the city; Southampton received about one-fifth of the load intended for it. Poole was saved largely by heath fires kindled by flares and incendiaries, which drew much of the attack; at Norwich the recently-installed balloon-barrage helped to spread the bombing by limiting the enemy to a safe height of about 8,000 feet. At Canterbury a barrage had been installed immediately after the first raid; the Germans seem not to have known that it was there, but even so their two attacks in early June were not very well concentrated. Ipswich, like Poole, was much helped by heath fires, while at Weston-super-Mare, where balloons guarded the premises of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, no very serious damage was done by the thirty to forty tons of high-explosive and incendiaries which went home on two successive nights.

Plate 22. The Guildhall, York, during the ‘Baedeker’ Raid on the night of 28th April 1942.

Plate 23. Air Marshal R. M. (later Sir Roderic) Hill, Air Marshal Commanding, Air Defence of Great Britain 1943–1944, and Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Fighter Command 1944–1945.

Plate 24. Lieutenant-General (later General) Sir Frederick Pile, Bt., General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Anti-Aircraft Command 1939–1945.

As if seduced by their own communiques, which claimed a spectacular success at Poole and good results elsewhere, the Germans were not deterred by substantial losses in June from assailing fairly well defended targets in July. A series of minor raids on Middlesbrough was followed at the end of the month by three attacks on Birmingham and one on Hull. The last four raids accomplished little—only three tons fell on Hull and thirty-four on Birmingham—and cost the attackers twenty-seven aircraft. Thereafter, with one exception soon to be discussed, the Luftwaffe made no more night raids of any consequence in 1942.*

The fighter-bomber force continued its day raids throughout the spring and summer, but never mustered more than about thirty serviceable aircraft and seldom more than twenty. In July its Messerschmitt 109’s were replaced by Focke-Wulf 190’s. By flying just above the sea, fighter-bomber pilots succeeded as often as not in eluding the radar chain, thus setting a difficult problem for the defences; but their limited numbers and small bomb-load—each aircraft carried about half a ton—kept the menace within bounds. The loss of only five fighter-bombers in May and two in August, despite almost daily operations in both months, shows, however, that the Luftwaffe had found at least one way of conducting a continuous offensive at small cost. At first the aircraft flew mostly in twos or fours, but formations of eight were sometimes used in later months.

‘Pirate’ raids by single bombers or small formations on aircraft factories and similar targets—a form of daylight attack which had caused the Ministry of Aircraft Production and the air defences some anxiety in 1941—had also much to commend them to a force with limited resources. Picked crews who had carefully rehearsed their roles with the help of maps, models, photographs and sketches could reasonably expect, by taking advantage of cloud-cover and of natural features likely to hamper observation from the ground, to reach well-chosen objectives with little risk of interception and, having bombed them, to reap the reward of their daring by escaping before effective fire could be brought to bear on them. Skies often veiled by dense clouds interspersed with ample breaks which helped the attackers to check their whereabouts were a perfect setting for such tactics. On one day in July when the clouds were low and there was much rain about, as many as thirty ‘pirate’ raiders visited the country with scarcely any interference from guns or fighters, bombing and damaging four factories, two aerodromes and four railway targets of some importance. Fortunately a scarcity of crews experienced enough to undertake such ventures limited an effort which might otherwise have done much harm.

* See pp. 310-11.

Towards the end of August the German high-altitude bomber-reconnaissance machine expected since 1941 (and already seen in the Mediterranean theatre) appeared at last. Despite the elaborate preparations made for its reception it proved extremely hard to catch. But a climate which favoured ‘pirate’ bombers gave little scope for reconnaissance at great heights, so that the six high-altitude machines which figured in the establishment of the German Air Staff’s strategic reconnaissance unit found little employment over England. About a dozen flights at heights in the neighbourhood of 30,000 to 40,000 feet were made before the innovation ceased to trouble the defences. About the same time another new reconnaissance machine—the Messerschmitt 210, designed to function also as a fast bomber and twin-engined fighter—was introduced, but proved a failure. On 6th September Typhoons—a type developed from the Hurricane—met two of the new machines at a great height over Yorkshire and destroyed them both. After two more had been shot down, Göring told representatives of the German aircraft industry that the words ‘He would have lived longer if the Messerschmitt 210 had not been produced’ would be his epitaph.

In October the Luftwaffe, encouraged by the success of recent fighter-bomber operations, planned a bigger raid by fighter-bombers than any they had yet attempted. The target was Canterbury, the time chosen the afternoon of the last day in the month. The two regular fighter-bomber squadrons mustered only nineteen serviceable aircraft, but machines from ordinary fighter units brought the number equipped with bomb-racks to sixty-eight. Another sixty-two fighters were detailed to escort the striking force and six more to make a diversionary sweep. The leaders crossed the coast near Deal and flew to their target with disconcerting swiftness. Consequently the balloons installed at Canterbury five months earlier had risen to only 700 feet when the attack began. Nevertheless they took the Germans by surprise and caused some pilots to drop their bombs too soon. Of forty-eight bombs aimed at Canterbury, thirty-one struck various parts of the city. One straddled the infantry and artillery barracks three-quarters of a mile from the cathedral, two fell close to the power-station; the cathedral itself and the railway station escaped unharmed. Engaged at first by light anti-aircraft guns and afterwards by fighters, the attackers lost two aircraft to the defences and a third in an accidental crash.

That night the enemy made a further attack on Canterbury. The raid was in two phases separated by an interval of about four hours. The first blow was notably unsuccessful, perhaps partly because of cloudy weather, still more because a haystack ignited by a chance hit attracted a good many crews to a neighbourhood about five miles

from the city. The second, delivered when the weather was improving, was rather more effective. The haystack was still alight and drew some bombs, as did a decoy fire kindled for the purpose; but eleven tons of high-explosive and incendiaries fell on Canterbury. Nevertheless the bombing was not well concentrated, so that on the whole it brought the Germans little to set against the loss of seven bombers. In a somewhat highly-coloured account of the day’s and night’s events the Germans claimed, with equal pride in their intelligence service and their marksmanship, that a bomb had fallen ‘only a few yards away from a house which was visited by Mrs. Roosevelt last Friday’.

On that note of modest triumph the 1942 offensive came virtually to a close. A few days later Anglo-American landings in North Africa caused such apprehensions that German troops entered the former Unoccupied Zone of France and half the fighter-bombers recently employed against the United Kingdom were temporarily absorbed into a special unit posted to Provence. And although they afterwards moved north again, their operations and those of the bomber force remained for the rest of the year too inconsiderable to call for notice.

In the context of the whole war the 1942 offensive scarcely seems important. The bomb-load dropped in the course of the year—about 6,500 tons, of which a sixth was dropped by day—was only the equivalent of one month’s bombing in the winter of 1940–1941. But the experience was not without its lessons for both sides. According to a naval liaison officer attached to the German Air Staff, it suggested that the bomber force on the Western Front, manned largely by men whose previous experience had been gained solely in Russia, where objectives were near and fighters few, was scarcely fit for operations against England;9 according to the Air Warfare Analysis Section of our own Ministry of Aircraft Production, that the results of German night attacks had come to be governed largely by the extent to which local conditions left crews free to fly low over their objectives.10 The German critic might perhaps have added that the bombers had in fact done quite well while they remained content with easy targets, reasonably accessible and not too well protected. And certainly the moral justly drawn in London and at Stanmore was that, notwithstanding the great progress made by night-fighters since 1940, balloons and guns were still essential, not so much to bring the enemy down as to keep him up so that point-blank bombing was impossible and the task of the Civil Defences was not made too difficult.

(ii)

In the spring of 1942 the Air Ministry, not without misgivings, had authorised resumption of the day offensive which had cost Fighter Command such heavy casualties in 1941. In 1943 day raids on targets within reach of the fighter force continued as a minor contribution to the ‘round-the-clock’ offensive against Germany. At the same time Fighter Command became the pool from which the fighter squadrons needed to support a landing in France would come in 1944. Thus Air Marshal Leigh-Mallory, who had succeeded Air Marshal Douglas at Stanmore towards the end of 1942, was able to retain much larger forces than were needed for home defence alone. The air defences also profited in 1942 and 1943 by the introduction of fast day-fighters like the Typhoon and new versions of the Spitfire, of new night-fighters like the fighter version of the Mosquito, and of improved radar equipment and more efficient methods of control. Controllers, once recruited from grounded or superannuated pilots, were now a corps of experts highly trained in the use of ingenious devices moulded by several years of practical experience. Necessity may be the mother of invention; but its period of gestation is a long one and its scientific offspring do not quickly reach maturity. Thus the air defences were able to meet the relatively light attacks of 1943 not only with more and better weapons than those of 1940–1941, but with accessories infinitely superior to the crude G.L. sets and immature airborne radar of that era.

No comparable progress had been made in the German bomber force. The German bombers of early 1943 were modified versions of those used in 1940, somewhat faster and offering a little more protection to their crews, but still incapable of carrying big bomb-loads on long journeys. The Luftwaffe had no heavy bomber like the Lancaster, no fast light bomber like the Mosquito, no bomber designed expressly for use at night. In the summer of 1942 a number of new bombs—the 40-kilogram phosphorus bomb, the thermite ‘fire-pot’ and a combined incendiary and high-explosive bomb—had made their appearance, but they were no substitute for an aircraft capable of reaching distant targets with a heavy load. Deploring his lack of such a weapon, Göring said frankly that it was ‘enough to make him scream’ and that the four-engined British and American bombers, which he regarded with ‘terrific envy’, were ‘far, far ahead’ of anything at his disposal.11

Göring blamed the aircraft industry for these deficiencies, but the weakness of the bomber force extended to spheres with which makers of aeroplanes were not concerned. The facts were that German policy after the Spanish Civil War had put the emphasis on

army-support bombers and that the triumphs of the French campaign had created an atmosphere in which foresight did not flourish.12 For those reasons, and perhaps also because conditions on the Eastern Front did not encourage a high standard of ability, the training of crews for long-range bomber sorties, had been neglected quite as much as the provision of new aircraft.13 Confronted with an unfamiliar task, the crews of 1940–1941 had acquitted themselves well; but since that time the training organisation had proved incapable of replacing by newcomers of like ability men killed or transferred to other duties.14 Apart from a few veterans, the pilots and navigators serving on the Western Front in 1943 were not, and doubtless would not have claimed to be, the equals of those who had made life precarious for Londoners and Midlanders two years before. Finally, by the early part of 1943 the threat of a fuel shortage had already begun to cause concern and even to curtail flying by units based in Norway.15 An actual shortage would involve more widespread economies which would certainly affect the general level of experience.16

On the night of 17th January 1943, the Luftwaffe replied to an attack on Berlin by making the first major raid on London since 1941. Double sorties and contributions from reserve training units brought the night’s effort—which included minelaying in the Thames Estuary and Humber—to well over a hundred sorties. According to prisoners of war a unit on the point of leaving for the Eastern Front was held back to take part in the raid. The night was cloudy, especially before midnight, when the first stage of the attack was made, and many crews, perhaps deceived by searchlights, dropped their bombs well short of the target. Less than two-fifths of the load intended for the capital fell on the huge expanse of the London Civil Defence Region; the attackers lost six aircraft. Nearly sixty fires were reported, but none was large, and the only serious incident occurred at Greenwich, where a power station suffered rather heavy damage.

The offensive continued on the 20th with a daylight raid on London by twenty-eight fighter-bombers escorted by single-engined fighters. Diversionary forces made demonstrations off the Kent coast and over the Isle of Wight. The London balloon-barrage was grounded immediately before the raid, but was ordered to 6,500 feet about six minutes after the time when the fighter-bombers were reported as having crossed the coast in the neighbourhood of Beachy Head. When in fact they reached the inner suburbs only a minute or so after the order had been given, some balloons had risen to five hundred feet while others were still grounded. The time was half-past twelve, and the busy quarter south of the Thames near Greenwich Reach was thronged with people. Approaching ‘at roof-top height’ according to eyewitnesses, and certainly below a thousand

feet, the fast-flying Focke-Wulf 190’s arrived at their target so swiftly that light anti-aircraft gunners at outlying sites had little chance of engaging them on their inward course. Eight bombs at Lewisham, two at Poplar and twelve at Deptford, Bermondsey and Greenwich caused heavy civilian casualties and seriously damaged a large warehouse at Surrey Docks. The suddenness of the attack gave some members of the public a disagreeable sense of insecurity. But if the defences incurred reproaches which no excuses could quite repel, they did much to atone; for the enemy paid for his success with the loss of three fighter-bombers and six fighters.

After two small and remarkably unsuccessful raids on Plymouth and Swansea in February, the Luftwaffe plumbed new depths of inefficiency in early March. On the third night of the month about a hundred tons of high-explosive were carried by aircraft sent to London, but only twelve tons hit the mark. Again the attackers lost six aircraft. Although few crews admitted that they had failed to find so huge a target, the German High Command were sufficiently well informed to know, or at least suspect, that the attack had failed. On 5th March the Führer complained that the offensive against England was being mishandled; when told that the Japanese believed that Europe would be the main theatre of war throughout the year he said significantly that the prospect was ‘not very pleasing’.17 Later he drew a number of scathing contrasts between British attacks on German cities and the feeble attempts of the German air force to retaliate. He pointed out that, whereas apparently British bombers with new navigational equipment could fly hundreds of miles and then hit a target measuring about five hundred by two hundred and fifty yards, the Luftwaffe was unable to find London, an objective thirty miles across and only ninety miles from the French coast.18 Unless that state of things was remedied, the German people would ‘go mad’ when they learned, as finally they must, that their confidence had been misplaced. Remarking on one occasion that the poor performance of the bomber crews was ‘scandalous’ and that he would tell Göring so, he asked repeatedly, ‘Why isn’t the Reichsmarschall here?’ But if the Reichsmarschall had been there, what could he have said except that he felt like screaming?

The remedy proposed by Hitler recalls Admiral Fisher’s dictum, ‘We need one man!’ He ordered the Luftwaffe to charge a suitable officer with the sole task of directing air warfare against England. After several names had been put forward the choice fell on Dietrich Peltz, a young and energetic regular officer who had commanded dive-bomber and bomber units in the Polish campaign and in the offensive against the United Kingdom in 1940–1941. After organising dive-bombing courses in Italy and commanding a bomber unit at the time of the Allied invasion of North Africa, he had held since

the end of 1942 a staff appointment concerned with the inspection of bombers and the organisation of the bomber arm. A major in the summer of 1942, he had since been promoted lieutenant-colonel, was now made a colonel and a few months later, at the age of 29, became a major-general.

Peltz took up his new appointment as Angriffsführer England towards the end of March. The Führer’s intention was soon partially defeated, for in the summer a crisis in the Mediterranean theatre caused Peltz to be charged with an additional role. His influence on the subsequent conduct of the offensive is difficult to trace, but at least part of the task he set himself seems to have been the preparation of a substantial bomber force for use in the early part of 1944.19 A month after his appointment his resources comprised sixteen reconnaissance aircraft (of which six were serviceable), a hundred and thirty-five bombers (one hundred and seven serviceable), and a substantial force of fighter-bombers, now called fast bombers and organised as a Geschwader of four Gruppen, one of which was in the Mediterranean theatre. Ninety-seven of the one hundred and twenty-three fighter-bombers in France were serviceable at the end of April.* An important addition which took effect in May was a special ‘pathfinder’ unit (I/KG. 66) whose crews were trained—not very successfully—to find a given target and guide others to it by means of flares.

Raids on Southampton and Newcastle on 7th and 11th March, for which Peltz was not responsible, were both utter failures, no bombs falling on either target; the attackers lost eight aircraft out of less than ninety. Norwich was attacked on two nights later in the month, but on the first occasion only a few bombs hit the city, on the second none. In daylight fighter-bombers attacked Eastbourne, Hastings and Ashford (Kent) with some success and made a further raid on London. This time the barrage was at 1,500 feet when the enemy appeared, and was ordered to 5,000 feet. Sixteen bombs fell at Ilford and Barking, but no important objectives were affected.

In the first half of April another fighter-bomber raid on Eastbourne was followed on the night of the 14th by an attack on Chelmsford. Of the seventy-seven tons which crews claimed to have carried to the target, nine fell within the borough boundary, fifteen near two wheat-stacks ignited by incendiaries early in the raid. The attackers lost six aircraft, but succeeded in hitting an important ball-bearing factory and damaging about 25,000 bearings stored in readiness for delivery to service users.

An innovation with which Peltz is popularly (but perhaps unjustly) debited came two nights later, when fighter-bombers fitted

* For details, see Appendix 40.

with supplementary fuel tanks were sent to London after dark. Thirty sorties were flown and twenty-seven pilots were believed by the Germans to have attacked the target. In reality their navigation was so hopelessly at fault that only two bombs fell within the London Civil Defence Region. Three pilots landed at West Malling aerodrome, near Maidstone, under the impression that they had reached France, and a fourth crashed near it. Altogether the enemy lost six aircraft. Similar and almost equally ineffective raids were made on many nights thereafter.

Unusual tactics paid much better a few nights later, when some thirty bombers sent to a forward base in Norway for the purpose made a dusk attack on Aberdeen. Flying low over the sea and avoiding the harbour on their inward route by crossing the coast some little distance from the town, they turned south over the target and escaped with scarcely any interference and no losses. Substantially the whole of their load came down on land, although only about two-thirds of it hit Aberdeen itself.

In May the results of night attacks on Norwich, Chelmsford, Sunderland and Cardiff showed only a small improvement over those achieved in March and April, despite a lavish use of marker-flares. Losses continued to be heavy. Constrained to tortuous courses by fear of Fighter Command’s night-fighters, deceived by decoys and other counter-measures and harried by General Pile’s guns whenever they approached a target of importance, the German bomber crews led a precarious existence. According to a lecturer at the Luftwaffe Staff College, their average life was somewhere between thirteen and eighteen sorties. Moreover, they could not be reckoned experienced until at least a third of it was spent.20

Day attacks by fighter-bombers, on the other hand, were reasonably successful, largely because they often took the defences by surprise. On several occasions bombs were aimed expressly at residential districts; sometimes German pilots admitted opening fire on pedestrians. In the early part of the year the attackers were seldom engaged before they had dropped their bombs, and sometimes arrived unheralded by the ‘warbling note’ of the air-raid sirens. On 7th May twelve aircraft bound for Lowestoft were turned back by fighters; but such occurrences were rare. Strenuous efforts by the defences to improve matters included a careful watch by radar stations with recently-installed equipment capable, at least in theory, of detecting aircraft flying only just above the water; the greatest possible vigilance by anti-aircraft gunners; and standing patrols by fighters in areas where attacks were frequent. Success came on 25th May, when the radar chain detected a formation of fighter-bombers bound for Folkestone when it was on the far side of the Straits. Pilots about to land after a standing patrol were warned

accordingly, met the attackers over the Channel, forced fifteen of them to turn away and harassed the remaining four so much that three of them dropped their bombs in the sea and the other in a swimming-pool. Five days later light anti-aircraft and anti-aircraft machine-gun crews at Torquay saw twenty-two fighter-bombers flying towards them just as independent warning of an impending raid arrived. All but four of the attackers managed to reach and bomb the town, but the whole batch were so warmly received by the gunners, and by fighters which joined in, that five of them failed to get back to their base. A week later the threat to southern Europe arising from the Allied conquest of Tunisia led to the withdrawal to the Southern Front of the fighter-bomber units responsible for day attacks.

Thereafter the Luftwaffe found any kind of daylight sortie over the United Kingdom increasingly difficult and was ultimately forced to do essential reconnaissance at night.21 In the last three months of 1943 probably not more than a dozen German aircraft flew over the United Kingdom by day; and the High Command was soon at its wits’ end to get photographic cover of the ports, assembly areas and aerodromes from which an Allied invasion of the European mainland might be launched. Night attacks continued on a small scale and generally with poor results. In the summer a new fast bomber, the Messerschmitt 410, made its appearance; in the autumn the Junkers 188, an improved version of the Junkers 88. These accessions, coupled with a careful timing of raids to coincide with the return of British bombers from Germany, helped crews to escape interception on the way to their targets and sometimes to reach them before the alert had sounded, but did nothing to improve their marksmanship or navigation. On the night of 25th July, when some fifty crews were sent with seventy tons of bombs to Hull, not one bomb hit the target; much the same thing happened in later months at the same place and at Lincoln, Norwich and Chelmsford. In the autumn the Germans, having noticed in July that aircraft of Bomber Command were dropping strips of metal foil to confuse their radar system, began to use a similar device themselves. But by that time their general performance was so poor that the additional burden placed on the defences—a drawback foreseen when the British decision to use the strips was taken—could have no decisive influence.

Meanwhile conflicting opinions had arisen among the Germans about the aims and conduct of the air offensive. Hitler, declaring that ‘Terror is broken with terror, and by no other means’, insisted that Bomber Command’s onslaught could be countered only by smashing British cities.22 The German Air Staff, knowing only too well that they had insufficient forces in the west for such a programme, were more inclined to put their effort into ‘intruder’ sorties against

returning British bombers and their bases. Their case was strong, but not strong enough to withstand the Führer, although even he could not make five hundred aircraft out of fifty. They pointed out, quite rightly, that ‘intruder’ raids were cheap and difficult to counter, and were at least potentially capable of causing Bomber Command a good deal of embarrassment.

Yet another opinion, warmly championed by anti-shipping experts within the Luftwaffe and somewhat half-heartedly endorsed by the Naval Staff, was that any course of action, including reprisal raids, which did not directly advance the campaign against Britain’s sea-communications was ipso facto a mistake. General Kessler, who had for some time commanded the force mainly responsible for air operations against shipping in United Kingdom waters with only grudging support from his superiors, put the matter very strongly in a letter written early in September.23 Addressing General Jeschonnek, the Chief of Air Staff—who incidentally had expressed his own opinion of the outlook by committing suicide a few days earlier—he pointed out that attacks on United Kingdom cities, backed by all the resources of the Luftwaffe, had failed to shake the British in 1940–1941, and were not likely to succeed now that only meagre forces were available. Describing shipping as the Achilles’ heel of the British Empire and shipping-space as ‘the deciding factor in the war’, he declared that if Germany could sink 100,000 gross registered tons of shipping a month ‘we should not need to worry about the industrial potential of England and America’. His conclusion was that the campaign against shipping should be ‘the sole task’ of the Luftwaffe’s striking forces in the west.

In the outcome these objections failed to turn the Führer from his purpose, and perhaps their only effect was to ensure that whatever the Luftwaffe did in the west would be done with less than its full might. A few ‘intruder’ operations in the autumn and early winter caused British authorities some anxiety, but left them amazed that efforts which might well have gone to swell such operations should be wasted on scattered ‘nuisance’ and reprisal raids. Similarly, the meagre contribution of the Luftwaffe to the war at sea in the Atlantic theatre served chiefly to remind the Allies of the dangers they were escaping. And night attacks on towns and cities failed, as we have seen, because the attackers were too few, too inexperienced, too weakly led and too poorly equipped to get the better of defences which had drawn strength from their early setbacks and assurance from a mounting tally of success accumulated since the turning of the tide in 1941.

By the end of the year the authorities responsible for home defence could thus contemplate a prospect utterly transformed since the perilous days of 1940. The spectre of invasion had retreated before the

reality of German failure in Russia and Anglo-American success in Africa. Within the last nine months new methods and weapons, coupled since September with the use of bases in the Azores, had cleared a path across the sea for a mighty flow of men and material from North America to the United Kingdom. In British coastal waters, and wherever convoy-routes came within reach of the vast array of German bases extending from the North Cape to the Pyrenees, shipping which served the Allied cause was still open to direct attack by airmen now trained to use torpedoes and other missiles of ingenious design; but units capable of such attacks were few, while technical squabbles and administrative blunders had combined to keep them short of the aircraft and weapons which would have extended their range and striking-power. At home the air war had followed the undulating course which we have traced. The air defences, after their triumph in the summer of 1940, had suffered the frustrations of the following winter before achieving some degree of control over the night-bomber. Meanwhile an air offensive at first British and later Anglo-American had carried the struggle forward over Europe. By the closing months of 1943 air supremacy over the United Kingdom seemed clearly within reach; and the further task that faced the Western Allies in the European theatre was to extend it to the Continent.

Blank page