Chapter 3: Advance Into Belgium, 10th May to 15th May, 1940

At General Headquarters in Arras the stillness of a spring night was rudely broke just before daybreak on the morning of the 10th of May, when German aircraft roared over the city and bombed the neighbouring airfields. The raid was part of a general and widespread attack by the Luftwaffe on the Allies’ airfields’, railways, headquarters and key supply points in an effort to cripple air forces and disrupt communications as the opening move of the German western campaign. Except in one or two places it did comparatively little military damage to British installations on the first day, and nothing that affected our plans, but it sounded noisily the call to battle.

Shortly afterwards, at about a quarter to six, a message from French Headquarters was received ordering a complete alerte, and about half an hour later came a further message through the Swayne Mission at General Georges’ headquarters to say that orders had been issued by the Supreme Commander for the immediate execution of Plan D(1)—that is, for the projected move forward to the River Dyle in Belgium (see Map 2). British General Headquarters accordingly sent out the following order:

Plan D.J.1. today. Zero hours 1300 hours. 12L. may cross before zero. Wireless silence cancelled after crossing frontier. Command Post opens 1300 hours. Air recces may commence forthwith.(2)

In untechnical language this meant that ‘Plan D comes into operation today at 1 p.m. 12th Lancers may cross the Franco-Belgian frontier before the. Wireless silence is cancelled after entering Belgium. The Commander-in-Chief’s Command post will open at Wahagnies at 1 p.m. Air reconnaissance may commence forthwith’. The rest of the morning was busy with preparations for the move forward and at one o’clock punctually to time, the armoured cars of the 12th Royal Lancers crossed the western frontier of Belgium. In the early morning the leading German troops had crossed the eastern frontiers of Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg. Without provocation, without warning, without regard for her own honour, Germany’s pledge to respect the neutrality of her neighbours was against treated as but ‘a scrap of paper’, though it had been renewed, unsolicited, only a few months before. Unlike Britain and France who were at

war with Germany, Holland and Belgium had trusted the German promise and were at peace when far more violent air raids than had disturbed Arras shattered the stillness of the night and Belgian and Dutch dreams of undisturbed neutrality.

News of German movements towards the frontier had reached the Belgian Government during the night and a four o’clock in the morning their Foreign Minister, M. Spaak, called on the British Ambassador in Brussels, Sir Lancelot Oliphant, and appealed for British help in resisting the German invasion.(3)

The German zero hour was fixed for 5.35 that morning and troops began the invasion of France, Luxembourg, Belgium and Holland punctually;(4) but a sabotage unit of sixty-four men, organise in five parties, crossed the frontier between Roermond and Maastricht two to three hours before. Three parties wore Dutch steel helmets and great-coats over their German uniforms; the other two wore fitters’ and mechanics’ overalls. Their aim was to capture various bridges but the bridge guards succeeded in blowing most of those attacked. The German XI Corps War Diary contains a report from one of these parties which states that it captured seven Dutch soldiers who, ‘were taken along, some in front and some flanking the detachment, to provide cover against enemy fire’.1(5)

For months the British Expeditionary Force had been deployed along the Franco-Belgian frontier between Halluin and Maulde. A rapid advance across strange country to a position which had indeed been photographed from the air but had not been reconnoitred, involved complex movements and required careful planning if it were to be carried out smoothly and without congestion of traffic on the roads; and the move must take some days to complete. But British plans for an advance to the Dyle had been carefully prepared and rehearsed and as a result all went well. The 12th Lancers arrived first, and the armoured reconnaissance units allocated by General Headquarters to I and II Corps reached the Dyle that night and were eventually deployed across the whole front. These were the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards, the 13th/18th Royal Hussars, the 15th/19th King’s Royal Hussars and the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards—all now mechanised but still fulfilling the old role of a cavalry screen moving ahead of the main force. They and the troops who followed them were greeted warmly by the Belgian people and saw nothing of the fear and confusion which was soon to choke the roads with refugees. One unit of the 3rd Division had a frontier barrier closed against them because they could not show the faithful but ill-informed official in charge ‘a permit to enter Belgium’. But they charged the barrier with a 15-cwt truck and the advance of the division proceeded.

The German Air Force made no serious attempt to interfere, though as Lord Gort had decided to risk moving in daylight as well as by night, the long columns should have been very obvious to the enemy’s reconnaissance aircraft (in spite of good march discipline which maintained wide intervals between vehicles), if they had been able closely to observe the area. As it was, the welcome immunity from the attentions of German aircraft was doubtless due in partly to the protection given by the Royal Air Force Air Component, who flew 161 sorties that day. But two other considerations help to explain the German conduct. In the first place, their air force in this phase of the battle was used mainly against pre-arranged targets or took the place of artillery in support of German ground forces. The opening raids on Belgian airfields had destroyed half the Belgian aircraft before they could leave the ground, and key positions in Holland had been seized by airborne troops following hard in heavy raids. Some of the French airfields and communications had also suffered severely, but only in one instance did the enemy have any considerable success over airfields in British use. At Condé Vraux, the field of No. 114 Squadron, they destroyed completely six of the eighteen Blenheims and rendered unserviceable the remaining twelve, the airfield and offices were severely damaged, and the nearby petrol dump was fired.(7) Thus the whole squadron and the airfield were virtually put out of operation at the start of the battle. The fact that our ground defence brought down more than half the attacking aircraft was poor compensation for such a loss. Elsewhere, however, our defence was more successful and damage not serious. In the second place, the German High Command expected that for both political and military reasons the Allies would advance into Belgium and this being so they were prepared to fight the Allied armies in the north as far forward as possible from the fortified French frontier.(8) It was not, therefore, the aim of the German Air Force to interfere with our advance at this stage.

The new front to which the French and British armies were moving runs from Sedan in the south to Antwerp in the north. Except in one twenty-mile sector it is covered throughout by watercourses which serve as ready-made tank obstacles. From Sedan the front follows the Meuse through Givet and Dinant to the fortress of Namur. From there to the River Dyle at Wavre is the one unprotected sector, known as the Gembloux gap. There an incomplete obstacle had been put by the Belgians. The front is thereafter covered by the Dyle from Wave to Louvain and from there runs behind canalised rivers to Antwerp and the sea.

The French High Command expected the main German effort in the Belgian plan between Namur and Antwerp, so they had concentrated strong forces there. On the right the French First Army

in the Gembloux gap held a front of approximately twenty-five miles with eight infantry divisions and two light armoured divisions of the Cavalry Corps operating out in front. In the centre, the British force holding approximately seventeen miles of the Dyle, from Wavre to Louvain, had nine divisions deployed in depth with three in the front line and with the cavalry mentioned above out ahead of them. On the British left the Belgian Army was falling back to continue the Allied line of defence to the sea. The French Seventh Army advancing to the mouth of the Scheldt had six infantry divisions with a light mechanised division operating out in front. A French military historian, Commandant Pierre Lyet, states that the First and Seventh Armies were mad up for the most part of Active and Series A Units—Active units being Regular troops of high fighting quality and Series A not much inferior though unequally in quality. Five motorised infantry divisions formed part of them, ‘as well as almost the whole of our resources in motor transport, anti-aircraft groups, regiments of tractor-drawn artillery, and battalions of modern tanks. In front of them were the three light armoured divisions, whose armour was the most powerful of the French Army’s mobile formations’.2

On the other hand, in the sector farther south between Longwy, Sedan and Namur, where the Ardennes and the River Meuse were thought by the French Command to make an armoured attack impracticable—where, therefore, they did not expect the main German effort—‘the Ninth and Second Armies were mad up chiefly of Series A and Series B divisions. Reinforcements from units of general reserve were on a smaller scale and those units were equipped with less modern material’. … Elsewhere Lyet writes: ‘The resources at the disposal of the two Series B divisions who were to bear the brunt of the attack were weak. They had almost no Regular officers. They had not been broken into war conditions by being in contact with the enemy on the Lorraine front’.3 The Second Army holding about forty miles had five infantry divisions between Longwy and Sedan with two cavalry divisions and a cavalry brigade in front; the Ninth Army held a front of over fifty miles with seven infantry divisions, two light cavalry divisions composed largely of horsed units with a few light tanks, and a brigade of Spahis out in front.

The French Second, Ninth and First Armies were comprised in the First Group of Armies under command of General Billotte. To the left of this group, sandwiched between the French First Army and the Belgian Army, was the British Expeditionary Force under the direct command of General Georges, commanding the

whole of the French north-east theatre of operations, including also the French Seventh Army with its independent role (page 23). His Second Group of Armies lay to the right of the First Group on the Maginot Line. The general reserve which General Georges had at his disposal was weak, namely thirteen divisions. It was much spread out and unable to act quickly in a counter-stroke. In addition there were four divisions (one Polish) in course of formation. Moreover ‘it must be noted too that the “centre of gravity” of these reserves was in Army Group 2, whereas the army group had not part in the advance into Belgium’.4 Thus the reserve was not placed so as to be easily available where the main German effort was expected.

In the plans of the French High Command there was another miscalculation which contributed to the disaster which followed. It was assumed that the Belgians’ defence of their frontier and the delaying action of the French and British cavalry screen would be enough to prevent the German forces from reaching the new main line of resistance in the north (the Dyle line) before the Allies’ move forward was completed. This assumption proved to be at fault so far as the French Ninth Army was concerned. When battle was joined some of the French Ninth Army were engaged before they were established on the new line; and the small general reserve was so situated that it could not effectively intervene.

During the first phase of the battle, however, the British Expeditionary Force suffered directly from none of these disadvantages. The main German effort was not directed on its front through the Belgian plain, and though the Belgian Army defending the eastern frontier was forced backwards more quickly than was expected the British defence was adequately organised when the enemy eventually reached our sector on the Dyle. Though the actual front line was held by only three divisions (2nd, 1st and 3rd) two were in support (48th and 4th), two were to be in reserve (5th and 50th), and two more were back on the Escaut (42nd and 44th). Lord Gort’s disposition of his divisions in depth was soon proved to be wise (see pages 47 and 48).

The Dyle position in the British sector was a fairly strong one, though three divisions on a front of 30,000 yards meant that the rive-line itself would be somewhat thinly guarded. The river is little more than a wide stream. The fact that its banks are extensively wooded mad infiltration of infantry a continuing risk, but the river and the railway, which for most of the way follows the eastern or enemy bank , are together fairly effective protection against tanks, and near Louvain the Belgians had built a few pill-boxes to strengthen the defences of the town. The low-lying vale through which the Dyle

flows quietly is from 500 to 1,500 yards wide and was in places flooded; the high ground which flanks the valley rises more steeply on the enemy side and from the hill ridge there a wide stretch of country to the west is overlooked. Some of our gunners found it difficult to choose sites which were hidden from German observation, but the artillery was deployed to give the maximum cover and an enemy would have found it expensive to attack successfully between Wavre and Louvain. It was in these two flanking towns, each on important roads and with important bridges, that the chief danger lay. A typical stretch of the Dyle is shown opposite page 68.

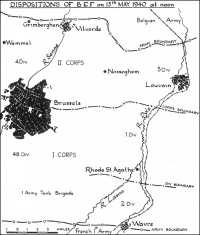

Our leading infantry brigades took up their positions on the river on May the 11th, and by the 15th the front was held as shown on page 47 and in the sketch map on page 48. East of the Dyle the cavalry had made touch with the enemy for the first time on the 13th.

While the British troops had thus been able to occupy their new front without interference, the Dutch, Belgian, and French troops had met the first onslaught of the German armies farther to the east. In Holland use of airborne troops covered by heavy bombing and followed up by tanks had enabled the Germans to get behind defences which had been planned to resist frontal attack. Already by the 13th coherent defence of the country was becoming impossible and it was clear that Holland could not hold out for long.(9)

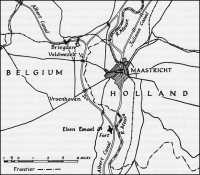

The Belgian plan was to fight a delaying action on the Albert Canal from Antwerp to the Meuse and thence along the Meuse from Liége to Namur, till the Allied forces could reach the Dyle. The Belgian Army was then to withdraw to the left sector of that line, between Louvain and the sea. But early on the opening morning of the campaign, before the German forces reached Maastricht (which is in the tongue of Holland, stretching south towards Liége), the Belgian defence of the Albert Canal front had been gravely prejudiced by the loss of the bridges at Briedgen, Veldwezelt and Vroenhoven, immediately west of Maastricht, and of the nearby frontier fortress of Eben Emael which was designed to protect them. For airborne forces, landed in rear of the bridges and on top of the fort, had seized the former and put the latter out of action almost before the defenders realised that the battle had begun, and although the Belgians won back and destroyed the bridge at Briedgen, the others remained firmly in German hands.5 By the 13th of May the Belgian Army was conducting a fighting withdrawal towards the northern sector of the Allied front.

Further south the position was graver. The Ardennes country was not after all proving to be an effective obstacle to the advance of German armoured divisions. The French outpost screen of horsed

cavalry and light tanks was drawn back as the enemy forces advanced there, and by the night of the 12th all the outposts of the French Ninth Army had retired to the west of the Meuse. On that night advanced German troops crossed the Meuse in rubber dinghies at a number of points and by the 13th of May they had formed small bridgeheads on the western bank near Sedan and Dinant.(10) The ‘strong forces’ which had been stationed by the French High Command where the main attack was expected were already in danger of having their position turned three days after the opening of the battle. For thought the bridgeheads over the Meuse were as yet only small, the advanced German armoured divisions had reached the eastern bank and were ready to cross, while further west the French Ninth Army’s move forward was not yet completed. ‘In view of the imminence of attack the density achieved on the 13th of May in the defensive positions where battle was likely to take place, and the general organisation of resources, were far from satisfactory.6

On May the 13th, while our 48th and 4th Divisions moved eastward to support the divisions of I and II Corps on the Dyle, German armoured divisions away to the south began moving westward over the Meuse.

On May the 12th a momentous meeting had been held at the Chateau Casteau, five miles north-east of Mons.(11) His Majesty the King of the Belgians, who had assumed command of the Belgian Army, and his aide-de-camp and chief military adviser, General Van Overstraeten, represented Belgium. M. Daladier and Generals Georges, Billotte and Champion—the last-named was head of the French Military Mission at the Belgian Army Headquarters—represented France. General Pownall, representing Lord Gort, and Brigadier Swayne, head of the British Military Mission at General Georges’ headquarters, attended from the British Expeditionary Force. The main purpose of the meeting was to secure coordination in the northern theatre of war. The Belgian Army was falling back to a position on the left of the British Expeditionary Force, acting under the independent command of the King. The French First Army, lying on the right of the British Expeditionary Force, was in the French First Group of Armies under General Billotte. The British Expeditionary Force, though under General Georges’ command, was not under General Billotte. It was clearly desirable that the operations of all these forces should be interlocked, and when General Georges asked if the King of the Belgians and Lord Gort would be willing to accept coordination by General Billotte as his representative, the King, and General Pownall speaking for Lord Gort.

From now on therefore Lord Gort must look to General Billotte for orders of the French High Command; after this meeting he would no longer expect to receive direct orders from General Georges. For such an arrangement to be fully effective, the ‘coordinator’ must be able to appreciate to the position of the commanders who look to him, and to translate directives from the High Command into practical orders which they can carry out. On the other hand the commanders whose actions he is to coordinate must have confidence in his judgement and be willing to act on his orders. In this instance the arrangement worked but haltingly, for neither of these conditions was ever wholly fulfilled.

The German break-through on the Meuse determined the whole course of the campaign and in particular the operations of the British Expeditionary Force. It will be well therefore to see how it came about that what was regarded by the French Command as a strong natural position fell so quickly, to understand why the defence failed and the attack succeeded almost without pause.

In the first place the French theory that the Ardennes country was ‘impracticable for tanks and unsuitable for the deployment of any considerable armoured forces’7 was proved to be mistaken. Provided

that there was careful planning and good organisation, the ground offered no serious hindrance to the rapid advance of considerable forces including numerous armoured divisions. Having regard to this fact and to the further fact that a thin screen, largely consisting of horsed cavalry and light tanks, was all the opposition to the enemy’s advance, it is easy to understand how German mechanised forces reached the river so unexpectedly early.

They found there, as has been explained, only weak opposition. Even if the French Ninth Army had had time to complete its move forward it would still have been far weaker than the forces which the enemy could quickly bring against it. But in fact even its leading units were hardly in position when the Germans reached the river. ‘On the left wing of the Ninth Army the manner of the occupying the position was changed several times in two days by the arrival of divisions in echelon and by the juxtaposition of infantry and the cavalry that had withdrawn from the Ardennes. The result was bad liaison, an embryonic state of organisation of the ground, and defective subordination of command.’8

In the Second Army sector the new front was not yet fully organised when the enemy attack west of Sedan. ‘… unfortunately the movement to establish the position still went on, and the battle was to start before staff and troops were familiar with their new tasks.’9 As the Series B divisions involved had ‘almost no Regular officers’ and had not previous contact with the enemy, it is not difficult to understand the failure of the defence.

But the speed and success with which the enemy exploited this weakness and also noteworthy. Vigorous action brought them to the Meuse on the night of the 12th/13th. Infantry using rubber dinghies to cross the river established small bridgeheads in the night, but the first attempt to get armour across was frustrated by the defenders. A full attack was therefore ordered for the following afternoon, the preliminary bombardment being undertaken not by artillery but from the air.(12) It was a new experience for the Allies, and in this case it was completely effective. The defending troops, their artillery positions, and their headquarters were subjected to heavy dive-bombing and its effect on some of the troops was, in the delicate phrase of the French historian, ‘to weaken those reactions necessary for battle’.10 Following quickly, German infantry enlarged the bridgeheads on the western bank and pushed on rapidly the construction of bridges for the armour to cross.

For the main German effort was not being directed through the

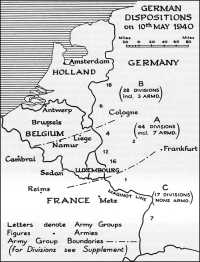

Belgian plain, where the strongest Allied forces in the north had been stationed to meet it, but through the Ardennes, where the weaker Ninth Army was to defend the Meuse. In fact, the German plan had been radically changed after the postponement of the attack originally ordered in January. Up to that date the French appreciation of German intentions had been correct. Now it was completely at fault. German security measures had successfully hidden their changed intentions. The strength of their total forces had been fairly accurately estimated by the Allies, but their new grouping and the changed plan for their deployment had not been discovered. It had not been realised that the main thrust was to be further south. As the adjoining sketch map shows, the German Army Group B (Colonel-General von Bock) facing Holland and the Belgian plain north of Liége had been given only twenty-eight divisions, three of them armoured. But south of Liége Army Group A (Colonel-General von Rundstedt) facing Luxembourg and the Ardennes had forty-four divisions, including seven armoured. Army Group C (Colonel-General Ritter von Leeb) facing the Maginot Line from Longwy to Switzerland had only seventeen divisions and no armour. Behind the attacking army groups, well placed for use where needed, was a reserve of forty-five divisions, three times the size of the ill-placed French reserve.(13) Moreover, cooperating with the two attacking army groups—A and B—were two ‘Fleets’ of the German Air Force, which together had about 3,700 aircraft when the offensive began.(14) The German command as developed during early operations is shown in Appendix III.

The evolution of the new German plan is discussed in a supplement on ‘The Planning and Conduct of the German Campaign’. But neither the change of plan nor the consequential dispositions were known at this time. All that was known was that four days after the battle had been joined a German advance through the Ardennes had so far succeeded that leading units were already across the Meuse. If they were not stopped the Allied position on the Dyle would soon be outflanked, and, while the British forward divisions concentrated their attention on their attention on their immediate front, Lord Gort was already having to look over his right shoulder at what was happening in the south. The news from there went from bad to worse. On the 14th of May, in the words of Commandant Lyet, ‘The Meuse position was forced on a front of about twenty kilometres. To restore the position we worked all day to mount a counter-attack towards Dinant but … the counter-attack could not be launched.’11 ‘The situation was very serious, since the complete disorganisation of our routed divisions seemed to offer no hope of their rehabilitation. Facing the breach, into which about 500 German tanks were pouring, the immediate

German Dispositions on 10th May, 1940

reserves were infinitesimal … as to the reserves which General Georges was sending to the nerve centre, they would not be in a position to intervene for several days.’12

For, as the German attacks on airfields declined, their attacks on the communications behind the Allied front increased in intensity and with significant results. Most of the French Army’s mechanical road transport had been allocated to their First and Seventh Armies; to move reserves which were stationed south of the Aisne they relied

mainly on slow horse-drawn transport or on the railway system. During these first few days the latter had been interrupted at so many crucial points that repairs could not keep pace with damage, and that movement of troops to the battle-zone or for the purpose of counter-attack became a slow, roundabout and precarious business. The Ninth Army and the Second Army sought to maintain touch but ‘this stop-gap front had no cohesion on the morning of the 14th. The units of two armies were intermingled, liaison was bad. No commander coordinated the whole’. And ‘On the south bank of the Meuse the battalions of the Ninth Army’s extreme right were successively “rolled up” from their right.’13

Meanwhile the French Cavalry Corps, out in front of the French First Army astride the Gembloux gap, were heavily engaged and gradually forced back, fighting hard, till the main position held by the infantry was reached. At one point this was indeed penetrated by the enemy, but a counter-attack restored the position. The 12th Lancers and the other cavalry units in front of the British sector withdrew in conformity with the French on their right and during the 14th crossed the Dyle. The infantry outposts on the east bank of the river were at the same time withdrawn and bridges destroyed as the enemy approached our main position. By the afternoon of the 14th we were in contact along our whole front.

The War Diary of Bock’s Army Group B records that the Sixth Army had been told that it was of the greatest importance ‘to break through the enemy position between Louvain and Namur in order to prevent the French and Belgian forces establishing themselves in this position’.14(15) They lost no time in trying but our artillery (which played a large part throughout the campaign) was already disposed in depth and the concentration which they put down in the late afternoon caused the enemy to draw back; at about seven o’clock in the evening, however, they mad the first of a series of attempts to capture Louvain where Major-General B. K. Montgomery’s 3rd Division held the front. The 2nd Royal Ulster Rifles beat them off, but the 1st Grenadier Guards’ forward posts on the east bank were forced to draw back to the line of the river.(16)

Throughout the next, May the 15th, attacks were resumed along the whole British front, the German IV Corps attacking in the 2nd Division’s sector near Wavre and their XI Corps the 3rd Division in action at Louvain. Fighting began on the front of the 2nd Division during the morning, where elements of the German 31st Division mad a small penetration across the Dyle in the sector held by the 6th Brigade.(17) This was cleared up in the afternoon by counter-attack,

Dyle Front

British Dispositions 15th May 1940

(a) Infantry

| Divisional Reserve | Front | ||||

| II Corps | 4 Division | ||||

| 3 Division | 8 Bde | 2nd E. Yorkshire, 4th R. Berkshire, 1st Suffolk | 7 Gds Bde | 1st Coldstream Gds, 2nd Grenadier Gds, 1st Grenadier Gds | |

| 9 Bde | 2nd R. Ulster Rifles, 2nd Lincolnshire, 1st KOSB | ||||

| I Corps | 1 Division | 1 Gds Bde | 2nd Coldstream Gds 2nd Hampshire 3rd Grenadier Gds | 2 Bde | 2nd N. Staffordshire, 6th Gordons, 1st Loyal Regt |

| 3 Bde | 1st Duke of Wellington’s, 2nd Foresters, 1st K. Shropshire LI | ||||

| 2 Division | 5 Bde |

1st Camerons 7th Worcestershire 2nd Dorsetshire |

6 Bde | 1st R. Welch Fusiliers, 1st R. Berkshire, 2nd Durham LI | |

| 4 Bde | 1st/8th Lancs Fusiliers, 2nd R. Norfolk, 1st R. Scots | ||||

| 48 Division |

(b) Royal Armoured Corps, Artillery, & Machine Guns

| GHQ & Corps Troops | Divisional Artillery & Attached Machine Guns | ||

| II Corps | 5th R. Inniskilling Dragoon Gds, 15th/19th King’s R. Hussars, 2nd R. Horse Artillery, 2nd Medium Regt, 53rd Medium Regt, 88th Army Field Regt, 59th Medium Regt, 53rd Lt. Anti-Aircraft Regt, 8th Middlesex (MG), 4th Gordons (MG) | 3 Division | 33rd Field Regt, 7th Field Regt, 76th Field Regt, 20th Anti-Tank Regt, 1st/7th Middlesex (MG), 2nd Middlesex (MG) |

| I Corps | 12th R. Lancers, 13th/18th R. Hussars, 4th/7th R. Dragoon Gds, 1st Army Tank Bde, 1st Medium Regt, 140th Army Field Regt, 3rd Medium Regt, 1st Heavy Regt, 98th Army Field Regt, 5th Medium Regt, 61st Medium Regt, 63rd Medium Regt, 52nd Lt. Anti-Aircraft Regt, 4th Cheshire (MG), 6th Argyll & Sutherland (MG) | 1 Division | 67th Field Regt, 2nd Field Regt, 19th Field Regt, 21st Anti-Tank Regt, 2nd Cheshire (MG) |

| 2 Division | 99th Field Regt, 16th Field Regt, 10th Field Regt, 13th Anti-Tank Regt, 2nd Manchester (MG) |

Dispositions of BEF on 15th May, 1940, at noon

the 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers and the 2nd Durham Light Infantry being chiefly involved in fighting which continued throughout the day. Second-Lieutenant R. W. Annand of the Durham Light Infantry was awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry in this action.(18) A renewed attempt to take Louvain from the 3rd Division had started earlier, prefaced by a two-hour bombardment of the area north of the city held by the 9th Brigade and the 7th Guards Brigade. Here a tangle of railway lines and sidings, goods yards, sheds and warehouses made it a difficult area to preserve inviolate. Units of two German divisions succeeded for a time in pressing back some posts of the 2nd Royal Ulster Rifles, but a counter-attack by the 1st King’s Own Scottish Borderers restored the position and drove the enemy out of the railway yards. North of Louvain the 1st Coldstream Guard were heavily attacked and their right company was for a time forced

back. But here too a counter-attack in which light tanks of the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards took part drove the enemy out and completely re-established the front. All other assaults were successfully driven off. The German Sixth Army reported to Army Group B that they had not succeeded in penetrating the Dyle defences at any point.(19)

In the afternoon it was learned that the French First Army on our immediate right had been heavily engaged and that a 5,000-yard breach had been made in their front where there was no river protection. Lord Gort, who had established his Command Post at Lenneck St Quentin, to the west of Brussels, offered to lend General Billotte a brigade of the 48th Division, then in I Corps reserve, to help in restoring the situation. But the French Commander decided to withdraw the First Army to a line between Châtelet and Ottignies, and the British I Corps had to conform by swinging back its right from Rhode St Agathe along the line of the River Lasne to link up with the French in their new position.(20) The Wavre sector of the Dyle was evacuated on the night of the 15th/16th under cover of remorseless artillery fire on the enemy’s advancing troops.

While this adjustment was taking place in the right or southern sector of our front, II Corps stationed the 4th Division in a defensive position behind our left flank, with two brigades on the road between Nosseghem and Grimberghen and the third in a middle position behind them near Wemmel. The 5th Division in GHQ reserves was moving up to the Senne, having now to stem an almost overwhelming stream of refugees flooding westwards. The 50th Division was on the Dendre: the 42nd and 44th were working on the defences of the Escaut.

In the north, catastrophe had overtaken Holland. The troops which had pierced her frontiers or landed from the skies were not, in truth, numerically greater than those of Holland, but the enemy had two decisive advantages. While the Dutch Army had extensive positions to defend and was to a large extent rendered immobile by the very nature of its task, the enemy was free to concentrate his force at points of his own selections; and he had an air force and armour against which Holland had no effective defence. One position after another was turned and the enemy decided to end the campaign by an overwhelming demonstration of German air power. Rotterdam was accordingly bombed till most of the business heart of the city lay in ruins. The French Seventh Army had carried out the role allotted to it. It moved with all speed across Belgium in an endeavour to support Belgian and Dutch forces at the mouth of the Scheldt. But there it had suffered severe losses, had run short of ammunition and had not succeeded (how could it?) in materially affecting the issue of the fighting in Holland. On the 14th of May the

Commander of the Dutch Army gave orders to cease fire. In five days Holland had been conquered.15

Three days before, a composite battalion, hastily formed from the 2nd Irish Guards and a company of the 2nd Welsh Guards, engaged on training near Camberley, had been sent to The Hook to cooperate with the local commander in operations designed to safeguard the Netherlands Government and restore the position at The Hague; but in event of the Government evacuating The Hague the battalion was to withdraw to The Hook for re-embarkation.(21) They found on arrival that no local operations were in progress and that the position at The Hague was obscure. Until the situation became clearer they took up a defensive position round The Hook. There they were bombed repeatedly and saw parachute troops being landed in the distance but there were no enemy troops in the vicinity. On the 14th of May, when it became clear that Dutch resistance was almost at an end, the battalion was re-embarked on the orders of the Cabinet. The British Military Mission to the Dutch Army Headquarters returned with them.

It would only be necessary to mention thus briefly an episode which had little military significance and no direct influence on the course of the land campaign, if it were not for the fact that its setting was in a series of naval operations of larger purpose, longer duration, and more lasting importance. As early as October 1939, when an attack on the Low Countries was first threatened, the Admiralty had prepared plans for operations off the coasts of Holland and Belgium. Their aim in such an event would be to clear Allied shipping from the threatened ports; to bring home diplomatic staffs and other important personages; to prevent Dutch or Belgian harbours from capture by the enemy with their installations and oil stores intact; and finally to lay a defensive minefield off the Dutch shores in order to hamper coastal movements by enemy surface vessels. Admiral the Hon. Sir Reginald Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, Commander-in-Chief The Nore was to be in charge of all these operations excepting only port demolitions, which would be the responsibility of Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay, Flag Officer Commanding Dover. The operations would involve a considerable number of warships and, although by the time the enemy’s invasion of the Low Countries actually began loss and damage inflicted on the German fleet in the Norwegian campaign had made it unlikely that our ships would be engaged by surface vessels, they were liable to be attacked by U-boats and certain to be attacked from the air. When, therefore, in the first week of May, intelligence pointed to an early offensive in the west, the Nore Command was reinforced by the Galatea and the Arethusa of the

2nd Cruiser Squadron, by the cruiser Birmingham and by eight destroyers of the 2nd and 5th Flotillas. All these were from the Home Fleet and were stationed at Harwich. As it was feared that Holland would not for long be able to withstand a German assault, all was in readiness when the campaign opened on the 10th of May. On that day the minelayer Princess Victoria and the 20th (minelaying) Flotilla sailed to lay the defensive minefield off the Dutch coast; cruisers went to Ijmuiden to bring off (by previous arrangement) the Dutch gold reserves and diamond stocks and to clear the port of merchant shipping; and four destroyers sailed for Ijmuiden, Flushing, The Hook and Antwerp with demolition parties which included military elements to assist in the destruction of large oil stocks in or near those ports. Reinforcements of flotilla vessels were ordered by the Admiralty to the Nore Command and Dover. The British Military Mission to Dutch Army Headquarters was also landed at Flushing.

On the 11th of May the Arethusa and two destroyers escorted to England two merchantmen carrying gold and diamonds. By then it was already clear that the situation land was rapidly getting worse and a Royal Marine guard was hastily sent across in two destroyers to ensure the safety of demolition parties, followed shortly after by the composite Guards battalion whose short stay at The Hook has been recorded above. On the 12th the destroyer leader Codrington fetched the Crown Princess and her family from Ijmuiden and on the 13th the Hereward brought to England Her Majesty Queen Wilhelmina and her suite and Sir Neville Bland, British Minister to the Netherlands. Later in the day members of the Netherlands Government and of Allied Legation staffs sailed in the destroyer Windsor. On the 14th destroyers brought the Guards battalion back.(22)

During these hectic four days, when rumour was rife and news uncertain, the demolition parties which had been landed had a difficult time, for the Dutch authorities on the sport were not at first convinced that the drastic measures we proposed were immediately necessary. Eventually those at Amsterdam, Flushing, Rotterdam and the Hook agreed that the time for the destruction of oil stocks had come and large quantities were destroyed or rendered useless at all four centres. Some demolitions were also effected in the ports, but only Ijmuiden, with the effective cooperation of the Dutch fortress Commandant, was blocked effectively. At other places delays imposed on the starting of preparations prevented the completion of the work, though some ships and shore parties stayed till the 17th—two days after the Dutch cease-fire.

All this time enemy aircraft were busy bombing and sowing mines, and our destroyers and minesweepers carried out their arduous duties in mine-infested waters under almost continuous air attack. Some air cover was afforded by Blenheims and Hurricanes of the

Royal Air Force flown from England, but the former had not speed enough to intercept the enemy dive bombers and the latter could not remain in the air long enough to give protection for more than short periods. The destroyers were almost incessantly in action and as long as they had sea room in which to manoeuvre losses were avoided, but in the narrow approaches and confined waters of the ports self-defence was inevitably handicapped. The destroyers Winchester and Westminster were seriously damaged and the Valentine was lost. When these operations off the Dutch coast were completed, however, it was clear that achievement had well outweighed the cost. Allied shipping which was of great value had been secured; the Dutch Royal Family and Government had been transferred to England; gold reserves and diamonds had been placed beyond the enemy’s reach; large stocks of oil had been denied him; and something had been done to delay his immediate full use of Dutch ports and harbour installations. The only ships of the Royal Netherlands Navy which were stationed in home ports at this time—a cruiser, a destroyer, and two submarines—had also moved safely to English harbours.

Although it was hoped that the enemy’s assault on Belgium could be held, it seemed only prudent to prepare for the possible loss of Antwerp. As soon as the German offensive opened on May the 10th, accordingly, the destroyer Brilliant had sailed for Antwerp with naval and military parties to clear Allied shipping and prepare for demolitions and the destruction of oil. By noon on the 14th twenty-six Allied merchantmen, fifty tugs and six hundred barges, dredgers and floating cranes had been cleared for England. Some demolitions were prepared, but King Leopold forbade execution of the more important until the threatening situation on May 17th brought his consent. Then 150,000 tons of oil were rendered unusable and the entrances to the docks and basins were blocked. But much that would have discomfited the enemy (and was therefore desirable from the British point of view) had to be left undone. Naval operations off the more westerly Belgian coast reached their climax later; it will be better to describe them in their due order as the story of the campaign unfolds.

One unusual form of operation, operation ‘Royal Marine’, had been prepared during the winter. It was designed to damage the heavy traffic of barges and other water transport using some of the main German rivers. Floating mines were to be launched into these rivers (1)1 from tributaries and (2) from the air. The first was a naval operation, carried out by Royal Marines under command of Commander G. R. S. Wellby, RN. It started as soon as the German attack began and by May the 24th over 2,300 floating mines had been streamed into the Rhine, Moselle and Meuse. The second method was only used by the Royal Air Force in the closing days of the campaign

and then on a small scale. There is evidence that damage was inflicted on the enemy but its extent could not be ascertained with accuracy in the circumstances which then existed.(23) later in the war similar methods were used with great effect.

Meanwhile what of the position in the air? The fact that our fighters played an important part in keeping the enemy air forces clear of the area through which the British Expeditionary Force was advancing has been noted already. The fighters of the Air Component, reinforced by two additional squadrons on the first day of the battle and by thirty-two more aircraft and their pilots three days later, flew without resting, as did the three fighter squadrons with the Advanced Air Striking Force. For the latter the first task was to protect airfields we were using and the fact that only one airfield sustained any serious damage (page 37) is evidence of their success in this duty. Their second task was to give fighter cover over targets attacked by our bombers. It will be seen presently what that involved and will be realised how greatly the odds were against them. They had not the requisite strength to be fully successful, yet, undaunted by the enemy’s superior numbers, undeterred by their own fatigue, the fighters of both forces went up again and again to contest for air master over the zones they were committed to defend. They lost heavily—the three Air Striking Force squadrons lost twenty aircraft and the Air Component forty-one in the first six days—but they brought down a large number of the enemy.(24) Our fighter pilots proved to themselves that in skill and in the qualities of the aircraft they flew they were more than match for the German Air Force. Unfortunately many of the detailed records of their deeds were lost during subsequent moves.

Bombers of the Air Component and of the Advanced Air Striking Force had in the same time sustained without hesitation even heavier losses. The detailed account of their actions makes splendid but sad reading. It is only possible to describe them in broad outline, to illustrate them by a few examples, and to estimate their results. In conformity with prearranged plans, these medium bombers were mainly engaged in attacks against enemy columns, concentrations, and communications behind the enemy front. They soon found that such targets were strongly guarded at high level by large number of fighters and at low level by quick-firing anti-aircraft artillery and machine guns. Our fighter forces were not strong enough to contest successfully the enemy’s air mastery over his own positions, so our bombers mostly went in to attack at low level, trusting to speed and surprise to save them from ground defence. But their speed was not great enough and the enemy’s defence was too strong to give them more than an outside chance to return unscathed, if at all, from such sorties.

Thus on May the 10th four waves, each of eight Battles, attacked successively German columns advancing through Luxembourg into France under cover of large fighter forces. Six of our fighters went up in an effort to clear the way while thirty-two Battles of Nos. 12, 103, 105, 142, 150, 218 and 226 Squadrons attacked at low level in spite of heavy fire on the ground. Thirteen were shot down and all the remaining nineteen were damaged. On May the 11th eight Battles of No. 218 Squadron went up to attack an enemy column on the borders of Germany. One returned, badly damaged. He reported that one of his comrades had made a forced landing in France; he knew that two others had been shot down; of the remaining four there was no news at all. On May the 12th one outstanding action was that attack on the bridges near Maastricht, over which the enemy was pressing forward into Belgium. The bridges and the advancing columns had been attacked the day before by both British and French bombers, apparently with little success. It was, of course, an area of prime importance to the enemy, for its was his main gateway to central Belgium; as such it was strongly protected by his fighters and ground defence. Knowing this, Air Marshal Barratt ordered that the crews of the attacking planes should be volunteers. Volunteers were asked for from No. 12 Squadron—and the whole squadron volunteered. So six crews were chosen by lot, though in the end only five were actually employed; for cover they were given two squadrons of fighters from the Air Component and ten Hurricanes from the Advanced Air Striking Force. But these were, of course, no protection from ground defences. The five Battles duly attacked. One returned to badly damaged that the pilot ordered the crew to bale out over Belgium; he alone brought it home. Of the rest nothing more was learned—or has been learned since. The evidence of the surviving pilot and other contemporary records are somewhat vague and a little contradictory. But there is no doubt that these five crews drove knowingly into an inferno of enemy fire and pressed home their suicidal attack to its inevitable end. The pilot and navigator of the aircraft which led the attack, Flying Officer D. E. Garland and Sergeant T. Gray, were each posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross—the first to be awarded in the campaign.(25) The German War Diary of XVI Corps records that on May the 11th the Maastricht bridges and the marching volumes of the 4th Armoured Division ‘are separately attacked by enemy bombers. Considerable delays result from this.’16(26) General Guderian’s XI Corps War Diary notes on the 13th that ‘Enemy fighter activity is exceptionally vigorous; in the evening the enemy carried out repeated air attacks against the crossing -points and in doing so sustains heavy casualties’ and adds

‘Repeated requests for increased fighter protection are without apparent success’.17(27)

On the third day of hostilities French General Headquarters expressed appreciation of our bombs’ attacks on German forces in the Bouillon area and considered that these ‘had checked the German advance and saved a serious situation’.(28) But it was soon clear that, taking our air operations as a while, this was an over-generous estimate. Their effects cannot be measured accurately. Certainly they caused some delay in the early passage of the Meuse, both at Maastricht and further south, but it was insufficient to affect significantly the course of the battle. And whatever value is attached to air operations in the opening days of the campaign, the figures given continued there would soon be no bombers left. But there was to be one more expensive day of desperate effort to stop the German advance in the neighbourhood of Sedan before bomber policy was modified.

In operations on May the 14th, in which the French Air Force also took part, six Blenheims bombed road and rail communications and two enemy columns near Breda in Holland to relieve pressure on the French Seventh Army, fought off an enemy fighter, eluded heavy ground fire, and returned without loss. It seemed at first that luck had turned, for by nine o’clock in the morning ten sorties had also been carried out by bombers of the Advanced Air Striking Force against the enemy’s pontoon bridges near Sedan and all had returned. But by mid-day there was grave news from the same area, where the enemy had greatly enlarged his bridgehead. General Gamelin and General Georges both asked Air Marshal Barratt for the maximum support, and this was promptly given. The Battles and Blenheims of Nos. 71, 75 and 76 Wings attacked in successive waves in spite of strong opposition from the enemy’s fighters and ground defence. The cost of this concentrated effort can best be shown in bald figures.

No. 76 Wing

No. 12 Squadron. Of five Battles sent against enemy columns four were lost.

No. 142 Squadron. Of eight Battles ordered to attack bridges four were lost.

No. 226 Squadron. Of six Battles also attacking bridges three were lost.

No. 71 Wing

No. 105 Squadron. Of eleven Battles which attacked bridges six were lost.

No. 150 Squadron. Of four Battles also attacking bridges four were lost.

No. 114 Squadron. Of two Blenheims which attacked columns one was lost.

No. 139 Squadron. Of six Blenheims (flown by No. 114 Squadron crews) against enemy columns four were lost.

No. 75 Wing

No. 88 Squadron. Of ten Battles which attacked bridges and columns one was lost.

No. 103 Squadron. Of eight Battles sent against bridges three were lost.

No. 218 Squadron. Of eleven Battles attacking bridges and columns ten were lost.(29)

Fifty-six percent of the seventy-one bombers employed were lost in action that afternoon. In such results are hard to determine. Photographic evidence was not obtainable. But the German XIX Corps War Diary’s situation summary at 8 p.m. notes that ‘the completion of the military bridge at Donchery had not yet been carried out owing to heavy flanking artillery fire and long bombing attacks on the bridging point … Throughout the day all three divisions have had to endure constant air attack—especially at the crossing and bridging points. Our fighter cover is inadequate. Requests [for increased fighter protection] are still unsuccessful.’18 And the summary of the Luftwaffe’s operations includes a note of ‘vigorous enemy fighter activity through which our close reconnaissance in particular is severely impeded’.19(30) It is clear from what meagre records remain that such fighter protection as was available was given to our bombers but that this was inadequate to cover seventy-one bombers against the strength of German opposition over the target area. Later in the evening twenty-eight bombers, Blenheims of Bomber Command, attacked with stronger fighter protection. Five were lost and two more made forced landings in France.(31) In all, out of 109 Battles and Blenheims which had attacked enemy columns and communications in the Sedan area, forty-five had been lost, and the impossibility of continuing such attacks by day seemed proved. On May the 15th daylight bombing was cut down. Only twenty-eight aircraft were employed and only four failed to return. But the German XIX Corps War Diary says ‘Corps no longer has at its disposal its own long-range reconnaissance … [Reconnaissance squadrons] are no longer in a position to carry out vigorous, extensive reconnaissance, as, owing to casualties, more than half of their aircraft are not now available’.20(32)

The Lysanders and Blenheims of the Air Component and the

squadron (No. 212) of Spitfires specially equipped for photographic reconnaissance were continuously engaged on both tactical and strategic observation. By May the 15th the density of refugee traffic flooding steadily westwards was a theme which recurred frequently in their reports of enemy movements. At one time, enemy transport on roads twenty to thirty miles east of Louvain and Wavre appeared to be virtually held up by the dense civilian procession.

In view of the heavy daytime losses the Battles of the Advanced Air Striking Force were on May the 15th switched to night bombing in the Sedan area and, although results could be night so effective nor so well observed, the change-over was justified by the fact that all returned safely.

But the night of May the 15th/16th is chiefly memorable in Air Force history as the first on which the Royal Air Force attacked German industrial objectives in the Ruhr(33) Till then the heavy bombers were held back from such targets in Germany by the British Government, partly to conform with French policy but also because they were themselves determined not to risk the infliction of civilian casualties so long as German observed similar restraint. the ruthless bombing of Rotterdam on May the 14th showed, however, that no regard for humanitarian principle influenced German policy. Their action was dictated solely by military convenience, and if this was to be the criterion it was not imperative to divert the Luftwaffe, if possible, from its concentration on France and Belgium. Even though civilian casualties might result, it was calculated that a British attack on vital objectives in the Ruhr would provoke the enemy to transfer some of his attention to this country and so weaken his attack on France and Belgium.

On this first night seventy-eight heavy bombers were directed from England against oil targets, nine against blast furnaces and steel works, and nine against railway marshalling yards; all were given as secondary objectives self-illuminating target such as coke ovens and blast furnaces and, as a last resort, marshalling yards. Sixteen failed to locate any targets and brought their bombs home again; only twenty-four found oil plants, some of which were reported to have been left burning fiercely. The remainder had to be content with marshalling yards. But all returned safely, which augured well for the future and for the vital conservation of British air power.

On May the 14th M. Paul Reynaud appealed for stronger fighter forces, urging that ‘if we are to win this battle, which might be decisive for the whole war, it is necessary to send at once, if possible today, ten more squadrons’. Lord Gort and Air Marshal Barratt made equally urgent appeals for additional squadrons to protect our own bombers, airfields and troops. But in England the expectation

that the German air attacks would shortly be directed against this country reinforced the unshakable opposition of Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding (Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Fighter Command) to the dispatch of further fighter squadrons to France. Already, in his view, so many had been sent that home defence was endangered, and after hearing his argument the War Cabinet decided not to send out additional squadrons at the moment, though they ordered preparatory steps for the early despatch of ten squadrons in case it should be decided to send them later.(34)

Meanwhile the toll of fighters in France continued. In the battle zone our small patrols were contending with enemy forces of twenty to thirty bombers protected by large number of fighters, and the Air Component and the Advanced Air Striking Force on May the 15th lost twenty fighters in the forward areas and on the constantly compelling task of guarding their own airfields, some of which were now threatened by the enemy’s advancing army.(35)

It is not possible to state with certainty the number of enemy aircraft destroyed by the Royal Air Force in these six days. A daily return was issued by the Quartermaster-General of the German Air Ministry. It does not show whether aircraft were lost through the action of the British or French aircraft or from the fire of ground defences, but its totals are likely accurate, for it was on the basis of this return that replacements were claimable. The total German air losses in operations, as shown in the return for these first six days of the campaign, were 539 aircraft destroyed and 137 damaged in operations over France and the Low Countries.

British losses in the same days were 248, including all aircraft which failed to return from operations or were destroyed on the ground, and those damaged and irrecoverable in the circumstances of the campaign.

Just before midnight on May the 15th the most northerly units of the Advanced Air Striking Force were ordered to move to airfields further south, and an hour and a half later Air Marshal Barratt closed his Advanced Headquarters at Chauny and moved back to Main Headquarters at Coulommiers.(36)

On May the 10th Mr Chamberlain’s Government had resigned and a National Government had been formed by Mr Winston Churchill. The Conservative, Liberal and Labour parties were all represented, differences of opinion and conflicting loyalties being, in Mr Churchill’s phrase, ‘all drowned by the cannonade’.(37) In the new Government Mr Churchill was not only Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury, but also Minister of Defence. Mr. A. V. Alexander became First Lord of the Admiralty, Mr Anthony Eden Secretary of State for War, and Sir Archibald Sinclair Secretary of State for Air.