Chapter 8: The Canal Line, 23rd May, 1940

The canal line and the Ypres front

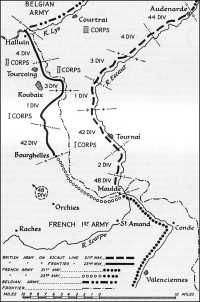

During the 23rd the moves necessary to effect the new disposition of the British Expeditionary Force continued. On their completion the shortened front, which followed the frontier defences from Bourghelles to Halluin on the Lys, would be held by four divisions—on the right I Corps with the 42 and 1st Divisions; on the left II Corps with the 3rd and 4th Divisions. The new dispositions are shown on the sketch map overleaf. Of the divisions thus freed, the 2nd and 48th were to assemble in the area south-west of Lille for employment in defence of the Canal Line on the west; the 44th Division was for the moment to be held in General Headquarters reserve; the 5th and 50th were still, as Frankforce, holding the Arras salient. Some of the consequent reliefs and movements could not be carried out till the night of the 23rd/24th. So, as the enemy pressure round Arras and the threat to the Canal Line near Béthune and La Bassée increased, the 2nd and 48th Divisions were each ordered to find a small force to move in advance of the divisions to the threatened sector. These advance forces, consisting of artillery, machine guns and infantry, were ‘X’ Force under Brigadier the Hon. E. F. Lawson, Commanding Royal Artillery, the 48th Division, and ‘Y’ Force under Brigadier C. B. Findlay, Commanding Royal Artillery, the 2nd Division.(1)

The full significance of the Canal Line stretching from Gravelines on the coast through St Omer, Béthune and La Bassée, can be clear seen on the adjoining map and on the German situation map for May the 24th, which is enclosed at the end of this book. It followed approximately the old line of fortified towns which played so important a role in French military history. Gravelines, Aire, St Venant, and Béthune were among the key places selected by Vauban for the exercise of his genius; Aire, St Venant, and Béthune were among the towns which Marlborough found it necessary to take in 1710 as a preliminary to his campaign in the following year. These places stood them on important rivers—today they are linked together by an unbroken line of canalised rivers or canals, and this Canal Line was the only natural barrier that could hinder the armoured divisions of the German Army Group A from driving into the rear of the British Expeditionary Force as the latter faced the pressure of Army Group B from the east. Lord Gort had taken the first steps towards the

British Dispositions on the Escaut and Frontier Lines

defence of this line on the 20th, when Polforce had been constituted to defend it from Aire to Pont Maudit. On that date the line was continued by Macforce, but by the 23rd the concentration of the French First Army had made the defence of this southern sector by British troops unnecessary, and most of Macforce was ordered to move to a more northerly sector of the Canal Line in the Nieppe Forest area. Only the 139th Brigade of the 46th Division (now in Macforce) was left in position between Carvin and Raches, where it joined up with the French when Macforce moved north. The 139th Brigade then came under the command of Polforce, whose responsibility was temporarily increased by this extension of its left flank and also be an extension of its right frm Air to St Momelin.(2) Between St Momelin and Gravelines, where there were also elements of a French division, miscellaneous British troops in the area were now grouped under the command of Colonel C. M. Usher and were known as ‘Usherforce’/ On the 20th Colonel J. M. D. Wood had begun to organise a garrison for Hazebrouck—‘Woodforce’.(3) By the 23rd, therefore, starting at the northern extremity the troops were disposed along the Canal Line with Usherforce on the right and Polforce on the left. Macforce was moving up towards the Forest of Nieppe and the advanced forces of the 2nd and 48th Divisions were moving to the Aire–La Bassée front.(4) the positions of British forces by the evening of the following day (the 24th) have been superimposed on the German situation map for the 24th, inside the back cover. How thin were the defences, how great was the need for the stiffening which the 2nd, 44th and 48th Divisions could give now that that they were freed from the main front, can be judged from the fact that although French troops had by then taken over the northern sector Polforce was still spread out over 40 odd miles.

The formation of these improvised ‘forces’ is a feature of Lord Gort’s conduct of the campaign which has sometimes been criticised. Such ‘forces’, hastily organised from miscellaneous and sometimes ill-equipped units, could have little time or opportunity to make sound administrative arrangements, or to ensure an effective system of communications. There were obvious disadvantages inherent in their constitution. On the other hand what was the alternative? Till the main British Expeditionary Force retired from the Escaut to the frontier the regularly organised and equipped infantry divisions were fully committed: none, till then, could be freed for the protection of the flank and rear. But behind the main front, organising for a sustained campaign as the British Expeditionary Force had been doing, until the German break-through at Sedan, were considerable numbers of men who in the present predicament must be used if possible to make up the deficiency in fighting divisions. ‘Don Details’ in Polforce, for instance, were officers and men of the 2nd Division

who had been on leave when their fighting began and were waiting in an assembly camp to rejoin their units when they were formed into this six-company battalion which helped to hold the Canal Line during critical days. There were, too, considerable numbers of Royal Engineers who had been engaged on work behind the front—construction companies, tunnelling companies, chemical warfare companies. There were the staffs of training and supply depots and men of the Royal Army Service Corps and Royal Army Ordnance Corps from various establishments. What Lord Gort did was to ensure that these scattered groups should as far as possible be gathered into ‘forces’; and to each he added as much artillery as could be spared and such infantry as could be found without weakening seriously the divisions fighting on the main front.(5) The only infantry available at first were the 25th Brigade, which had been an independent formation under GHQ orders before it joined the 50th Division; the 46th Division, the third of the partially equipped Territorial divisions which had been brought to France for labour duties and to continue their training; and what remained of the 23rd Division, whose fight near Arras on the 20th has been described. The ‘forces’ were thus, in the main, supplementary to the regularly constituted divisions, whose composition was not seriously affected. Their formation, under commanders who could act on their own initiative once they had been given a general directive, secured a measure of organisation and of fighting value where otherwise these rearward units would have been uncoordinated and wholly ineffective for defence purposes. It is difficult to see what better arrangement could have been made for their use at this time. The defence which they put up was at least sufficient to persuade Rundstedt that the Canal Line was being held and to make him hesitate to use his armour against it. It will be seen later that in the time thus gained Lord Gort was able to bring stronger forces up for its defence.

On the morning of the 23rd no orders or instructions for the projected Anglo-French counter-attack having reached him, Lord Gort sent a telegram to the Secretary of State urging that ‘coordination on this front is essential with the armies of three different nations’;(6) later in the morning General Blanchard arrived at the Command Post. A discussion followed as to the part which British troops could play in the implementation of the Weygand plan. Knowing what a comparatively small force he could make available and what General Billotte had said of the condition of the French First Army, Lord Gort made it clear that in his view the attack from the north could not be more than a strong sortie; if the gap was to be closed the main effort must come from the south. Accordingly he proposed that the northern attack should be made by two British divisions, one French division, and what remained of the French Cavalry Corps, and that it should

take place on the 26th if this would fit in with plans for the complementary attack from the south. Of the latter, Lord Gort had no information; he had received no details or timings for it, nor, indeed, had he any knowledge of the strength or situation of the French forces south of the Somme. He suggested May the 26th because he knew that reliefs then in progress made any earlier date impossible. General Blanchard concurred in these proposals and undertook to submit them to the High Command.(7) It is noteworthy that he did not feel able to decide without reference to French Headquarters.

In a message to the Secretary of State for War Lord Gort had also expressed his view that only a limited part could be played by the northern armies:

My view is that any advance by us will be in the nature of a sortie and relief must come from the south as we have not, repeat not, ammunition for serious attack.(8)

It is clear now that General Weygand held an opposite view:

To ease the task allotted to the Northern Group of Armies I had decided that the forces in position on the Somme should attack simultaneously in order to join up with them. I was too well aware of the weakness of the numbers at my disposal … to allow myself to indulge in any illusions regarding the strength of this thrust from the south—that is, from the neighbourhood of Amiens. But I calculated that however feeble it might be, it would at least create an additional threat to the German flank and thus increase the chances of success for the northern offensive.1

Explanation of these divergent views may perhaps be found in their authors’ differing appreciations of the strength and situation of the French First Army. General Weygand says that when he took over on the 20th May there were, to the north of the breach and in the 1st Army Group, forty-five divisions, consisting of the Belgian Army of twenty divisions, nine divisions of the British Army (already heavily engaged) and sixteen French divisions which included their best motorised units.2 He must have been counting largely on the French divisions when he attended the Paris meeting on the 22nd which decided that eight of the Allied divisions should attack southwards on the 23rd (page 111) for he seems to have expected that the French First Army could contribute five or six divisions to the attacking force.(9) Lord Gort, on the other hand, realise that the French First Army was in no condition to do anything of the kind. In addition to what was left of the Cavalry Corps, it had but eight divisions. Many of these had had desperate fighting before they reached the salient they now held, and although this was small in area, the front running through Condé, Valenciennes, and Douai measured over forty miles.

the depleted and battle-weary French troops were only with difficulty holding this salient (had not General Billotte said at the Ypres meeting that the First Army was barely capable of defending itself?) and since it held the bottom of the pocket in which the northern armies were now being contained, the position of the Allies would have been desperate indeed had the French troops failed to hold it intact. Too little credit has been given to the unspectacular but vitally important role which was plated successfully by the French First Army in this phase of the campaign.

On the morning of the 23rd General Georges issued Special Order 105 which read:

I. It has been decided:

1. That the joining-up operation in progress between the right of the First Army Group and the Third Army Group shall continue so as to close the return route of the German armoured divisions which have ventured towards the west.

2. That the enemy shall be hemmed in by the simultaneous construction of defences on the Somme from Amiens to the sea, on the sea-coast and on the southern flank of the First Army Group.

II. For the Third Army Group this will entail closing up of the Somme from Péronne to Amiens, and fighting back towards the north-east in the general direction of Albert–Bapaume.

III. Pending the completion of the formation of the Altmayer Cavalry Group to the left of the Seventh Army, it is vital that the Evans armoured Division with the forces it has available at present should immediately undertake a mopping-up operation directed at all speed towards Abbeville. Later this operation should be directed towards St Pol so as to cover the right of the British Corps in action from the Arras area towards the south.3(10)

It may be well to explain that General Robert Altmayer commanded a cavalry group of three divisions, now with the Seventh Army south of the Somme. It was his brother, General René Altmayer, who commanded V Corps with the French First Army Group in the north. The ‘Evans armoured Division’ meant the British 1st Armoured Division, recently landed at Cherbourg, whose movements are described in later chapters dealing with the fighting south of the Somme. It was never able to join the British Expeditionary Force or take part in the fighting north of the Somme. It will be realised that while General Georges’s order notes the importance of constructing defences on the Somme, on the coast, and on the southern flank of the First Army Group, the importance of the Canal Line, of a defence line between the German armoured divisions and the rear of the Allied armies which faced eastwards, does not seem to be recognised. General Georges’s reference to the

southern flank may have been meant to include this or he may not have known how far north the German armour had already penetrated.

Copies of two further orders were received by Lord Gort during the afternoon. The first, No. 18, was from General Weygand.

I. The German armoured divisions have ventured towards the sea in rear of our lines. It is to be expected that they will try to reopen their path eastwards by attacking on the right flank of the First Army Group while the latter is fighting on its left.

II. It is of primary importance to continue the manoeuvre which is in progress, to join up the First and Third Army Groups and to form a solid barrier which will prevent the withdrawal of the armoured divisions to their rear.

III. Simultaneously with the joining up of our forces facing east, every means must be used to block the enemy and paralyse the action of the armoured divisions on the flanks and in the rear.

Defence zones must be organised immediately and simultaneously on the Somme (Altmayer Detachment), on the right flank of the First Army Group (area of Boulogne, Béthune, and further south) and on the coast (naval action).

IV. The armoured divisions which have ventured thus far must perish there.

Signed: WEYGAND.4(11)

This recognised the need ‘to block the enemy’ on the flanks and in the rear of the main front, though the fact that Boulogne was now closely invested and German armoured divisions were between it and Béthune does not appear to be appreciated.

The second order was received by telegram (No. 1698):

General Weygand thus lays down the imperative task of General Blanchard. Shut off the route to the sea from German attack; re-establish touch with the main body of the French forces, so as to regain control of the British lines of communication through Amiens; held, and then beat, the German Army by counter-attacks. To this end, secure the necessary means from First Army and by moving the British Army to the right after the Belgian Army has been extended southwards. Seventh Army is responsible for the retaking of the Somme crossings.

Signed: GEORGES.5(12)

General Blanchard, seeking approval for the proposed Anglo-French attack on the 26th, can hardly have been enlightened by any of this and especially by being told that he should ‘hold and then beat the German army by counter-attacks’.

In a personal telegram to Lord Gort, General Weygand expressed his regret that they had not met, said that the attack from the south in the direction of Albert ‘is in very good shape’ and asked Lord Gort

to continue the move in which he was combining with General Blanchard ‘with confidence and with the energy of a tiger’.(13)

General Weygand’s mistaken belief that a manoeuvre to join up the First and Third Army Groups was ‘in progress’ and that the attack from the south was ‘in very good shape’, was further underlined when the Prime Minister spoke to him and M. Reynaud on the telephone. General Weygand then told Mr. Churchill that the French Seventh Army (which was south of the Somme) was advancing northwards and had already recaptured Péronne, Albert and Amiens.(14) This was mistaken information; in reality they had not even succeeded in reaching the Somme, where the enemy now held the river line firmly, with infantry divisions in position and with a number of well-establish bridgeheads. Further messages which the Prime Minister addressed to Lord Gort were doubtless based on General Weygand’s mistaken report, but the Secretary of State’s faith in the Weygand Plan showed signs of wavering. A message from Mr. Eden concluded by arrusing Lord Gort that:

Should, however, situation on your communications make this at any time impossible you should inform us so that we can inform French and make naval and air arrangements to assist you should you have to withdraw on the northern coast.(15)

Later in the day he sent Lord Gort a message on behalf of the Cabinet:

Need not assure you that we are all following your action with utmost sympathy for your almost overwhelming difficulties and with complete confidence in your fortitude and resource.(16)

While these affairs were occupying part of the attention of the Commander-in-Chief he was also concerned by what was happening on the Canal Line and at Arras. The first German armour and infantry had reached the Canal Line opposite St Omer during the night of the 22nd/23rd. A part of the 58th Chemical Warfare Company, Royal Engineers, sent to demolish the main brigade found the enemy clear a road block at its western approach. They push a truck-load of explosives on to the middle of the bridge under fire and there blew it up, but the bridge was not wholly destroyed.(17) A platoon of ‘Don Details’ and some gunners defending it were gradually drive back and eventually withdrew to fresh positions at Hazebrouck, while German troops occupied St Omer (which lies on the enemy side of the canal) and began to form a bridgehead.(18) At other crossings in the sector, detachments of 392nd Battery, 98th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, fought gamely with single guns.

A brief account of what they did may be given, simply as an illustration of the part played by such small detachments of artillery,

infantry, sappers and men of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps at this time, when the enemy sought to enlarge their bridgehead east of the canal and no British divisions were yet in position to oppose them.

On the 22nd two troops of the 392nd Battery of the 98th Field Regiment Royal Artillery were hastily sent up to form part of the defence between St Momelin and Wittes. They had only seven guns, for one was being repaired in workshops. One gun with its detachment was therefore sent to cover each of the bridges at St Momelin, St Omer, Arques, Renescure, Wardrecques, Blaringhem and Wittes. This, briefly, is what happened when the Germans attacked.

The gun at St Momelin. Enemy-occupied houses and mortar positions across the bridge were destroyed by gunfire and the gun and detachment, being well dug in, survived retaliation and repulse attempts to cross till they were relieved by French troops on the 25th.

The gun at Hazebrouck. On its way to St Omer (which was already in enemy hands) the gun detachment was ordered to defend Hazebrouck. It was sited to cover the road from St Omer and fifteen minutes after digging in it stopped an enemy column advancing down the road, the leading vehicles being knocked out. Eleven enemy tanks than attacked the gun. One (probably two) tanks were put out of action. Then four shells from the enemy tanks brought disaster. The first disabled the layer and Sergeant Mordin took over. The second wounded Sergeant Mordin in the eye but although in great pain he carried on. The third killed Lance-Sergeant Woolven, the gun’s No. 1, and badly wounded the remaining member of the detachment. The fourth hit and exploded the gun’s ammunition trailer. The gun, being now useless, was somehow withdrawn with its wounded detachment.

The gun at Arques. Sappers were blowing the bridge when the gun arrived. A position was taken up about a mile to the east. Advancing enemy troops were fired on but were nearing the gun position when the 12th Lancers arrived (page 130) and, under cover of their fire, the gun was withdrawn.

The gun at Renescure. Enemy-held houses across the bridge were destroyed by gunfire, and though two of the detachment were wounded by gun remained in action till the late afternoon. An enemy attack then developed from the flank. One enemy tank was knocked out but accurate mortar fire was put down on the gun position and under cover of this the enemy closed in. It was decided that the gun must be saved, but as it was limbering up the tractor was put out of action. Before anything could be done the position was over-run.

The gun at Wardrecques. The gun was placed under the command of an officer with a party of French infantry. Houses opposite were destroyed and an enemy machine gun silenced, but heavy retaliation killed the French officer and caused a temporary withdrawal of his men. The gun remained in action, but was destroyed by a direct hit shortly afterwards.

The gun at Blaringhem. This gun also covered parties of French and British troops. An attack at half past eight in the morning was repulsed and an enemy tank and two armoured troop carriers were hit. A second attack came in two hours later and the troops were forced back, but the gun remained in action and had fired 130 rounds when the enemy closed in. It was then limbered up and was being withdrawn when a shell from a German tank broke the connection and the gun had to be abandoned.

The gun at Wittes. This gun was got into position during the night of the 22nd. 23rd. Nothing further was heard of it, though later it became known that the detachment was captured.(19)

Thus at seven crossing detachments with a single guns played a part in delaying the enemy advance for longer or shorter times. Clearly they could have done no more.

Early in the morning of the 23rd A Squadron, 12th Lancers—by now only five armoured cars—was sent forward to reconnoitre the St Omer area.(20) They arrived in time to cover the 392nd Battery’s withdrawal of their gun from Arques to Morbecque, extricated a party of Royal Engineers under fire of enemy tanks, engaged with good effect enemy infantry on the ridge near Lynde, and had an encounter with enemy tanks astride the road from St Omer to Cassel near La Cross. But they found no British troops in the area St Omer–Renescure–Lynde or between Renescure and Hazebrouck.

By the end of this day’s fighting the enemy had a fair-sized bridgehead here, and the units of Polforce in this sector had taken up fresh covering positions at Morbecque, Steenbecque and Boeseghem. Some detachments on the Canal Line were, however, overrun and failed to get away. During the day the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, with a squadron of the 15th/19th Hussars (from H.G.Q. Troops) under their command, were sent to strengthen the position; and at Morbecque, Blaringhem and Boeseghem they were in action with enemy forces in some strength.(21) From St Omer through Aire to Robecq the Germans had now won the canal crossings, our small detachments being either driven back or overcome by the enemy. From Robecq to Gines, and south of Hinges, through Béthune and La Bassée, the Canal Line was unbroken.

Fifteen miles away to the south of the Canal Line, Arras still held out. When the morning of the 23rd dawned, the advanced elements of the German 5th and 7th Armoured Divisions had crossed the Scarpe to the west of the town(22) but then 17th Brigade (5th Division) still held Maroeuil and tanks of the French Cavalry Corps were still at Mont St Eloy. Bitter fighting ensued, and both places were lost and retaken during the day. Gradually, however, weight of numbers told and our troops were forced back. By nightfall the French cavalry had withdrawn north of Souchez while the 17th Brigade held precariously

a line from Berthonval Farm to Ste Catherine, with the 151st Brigade (50th Division) in a defensive position behind their right rear between Souchez and Vimy. Tanks of the 1st Army Tank Brigade in action with the enemy’s armoured divisions had covered first Carency and then Souchez and had fought advanced units which reached the high ground above Carency: but when night fell they were ordered to really behind the Canal Line and they withdrew to the neighbourhood of Carvin.(23)

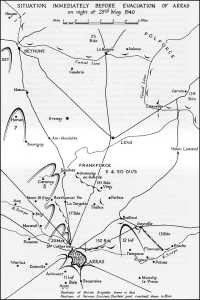

Meanwhile to the east of Arras the enemy attacked persistently and after two hours preparation with artillery and mortar fire succeeded in getting across the river at the junction of the 150th and 13th Brigades. The left battalion of the former—the 4th Green Howards—lost heavily and finally stopped the enemy only a little short of Brigade headquarters at Bailleul. Of the 13th Brigade the 2nd Wiltshire fought off a number of desperate attempts by the enemy to cross the river Scarpe in assault boats. The German infantry advanced to the river in waves and suffered extremely heavily casualties and a bridging team moving up was destroyed by our artillery. But the attack persisted and about eight o’clock in the evening a crossing was effected at Roueux and the 2nd Wiltshire with part of the 9th Manchester’s machine guns were withdrawn to hold a defensive flank between Bailleul, Gavrelle and Plouvain.(24) From there the 13th Brigade front still followed the line of the Scarpe to Biache. The position at the end of the fighting is shown on the accompanying map from which the desperate situation of the troops in the Arras salient is apparent.

In Arras itself the garrison had a hard day. The 11th German Motorised Brigade tried on three sides to penetrate the town, roadblocks and barriers at the exits being subjected to heavy dive-bombing before their attacks began.(25) But everywhere the garrison held them at bay, and when night fell the enemy had mad no gains here.

At about seven o’clock in the evening, Major-General Franklyn received Lord Gort’s order that the town was to be held ‘to the last man and the last round’.(26) The map shows clearly how hopeless its position had become. The troops of the 5th and 50th Divisions were being pressed back by the weight and numbers of the enemy—three divisions and motorised brigade.(27) The town was closely invested on three side and less than five miles now separated the enemy’s forces on the north-east and north-west of the town. The 17th Brigade and the 150th Brigade could not hope to maintain their positions for long with the German armour working round their right flank and already before Béthune. That evening the Arras garrison barricaded the northern exits in preparation for a final siege. But later in the evening Lord Gort decided that as it was now impossible to hold the high ground to the north of Arras, the Béthune–La Bassée Canal Line

must be his southern line of defence; no good purpose would therefore be served by leaving to their fate the Arras garrison and the forces covering the town. Major-General Franklyn was ordered to withdraw his whole force (including the garrison) behind the Canal Line. Orders reached units al ittle before midnight, and most of the covering forces managed to withdraw during darkness without serious interference. But the garrison and units of the 150th Brigade could not all get clear before daybreak. They had been ordered to retire via Douai, but the enemy were actually astride the main road leading there from Arras through Gavrelle and some units had to fight their way out. Lieutenant The Hon. Christopher Furness, of the 1st Welsh Guards who formed the rear-guard, was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallantry in this fighting.(28)

In the words of Lord Gort’s despatch the defence of Arras ‘had been carried out by a small garison, hastily assembled but well commanded, and determined to fighting. It had imposed a valuable delay on a greatly superior enemy force against which it had blocked a vital road centre.6

From the 19th to midnight of the 23rd/24th Arras had indeed troubled the enemy. Rommel had been ordered to take it on the 20th, but failed to do so.(29) Our counter-attack on the 21st upset German plans still further and delayed the enemy’s advance northwards. On the 22nd the German Fourht Army commander reported to Army Group A that Arras would be attacked that afternoon from three sides. He asked whether Kleist Group should push on to Boulogne and Calais as ordered, or await clarification of the situation at Arras. Rundstedt decided ‘ first to clear up the situation at Arras and only then to push on to Calais and Boulogne’.7(30)

When darkness fell on the 23rd it was still not cleared up but, as will be seen later. Kleist had been allowed to move against the Channel ports. If the holding of Arras was of such importance, its evacuation had corresponding significance. It left the French First Army deployed in a quadrilateral Maulde, Condé, Valenciennes, Douai in an uncomfortably narrow salient. None the less, the evacuation of the Arras salient is not open to criticism. With the enemy pressing in on both flanks it could not have served as jumping-off ground for an attack. It could not have been held much longer unless altogether stronger forces could have been spared for the purpose. And in fact there were none to spare—either French or British—at this time, though this was the day on which, according to the decisions of the Paris meeting on the 22nd, the British Army and the French First Army should attack south-west with eight divisions.

Air reconnaissance from England penetrated, for the first time in two days, to the main British front, the reconnoitring planes being given fighter support. Doubtless their information was useful to the Air Ministry, but the divorce of the Air Component from the British Expeditionary Force and the growing difficulty of communications greatly limited any value it might have had to those engaged in the battle. The one slender wireless link between England and Lord Gort’s headquarters was overloaded with traffic and there seems to have been little or no interchange of information regarding air operations except in daily situation reports. Day bombing was confined to the Boulogne area, for the one attack ordered in the Arras area was unable to locate the target owing to low cloud. Fighters were again active, providing cover for reconnaissance planes, escorting transport aircraft, and conducting offensive patrols over Arras, Cambrai, Lille, St Omer, and the Channel ports and coastal area. In all, 250 fighter sorties were flown and a number of enemy aircraft were destroyed. And at night 161 bombers attacked the enemy’s communications in France and Belgium.(31)

Situation immediately before evacuation of Arras on night of 23rd May, 1940

Blank page