Chapter 14: The Final Withdrawal, 29th May, 1940

By the early morning of the 29th German forces were closing up to the Poperinghe–Noordschote line where rear-guards of the 50th and 3rd Divisions covered the eastern flank of the army. To the south of that line the depleted 44th Division was in the Mont des Cats positions and the 48th Division’s 145th Brigade in Cassel still held their isolated post.(1)

Early in the morning the 44th Division were subjected to heavy mortar fire and this was followed later by intense dive-bombing, and enemy tanks and lorried infantry were seen apparently preparing for an attack. Shortly before ten o’clock in the morning the troops moved out in two columns, and though the enemy shelled them they were not molested. Greatly reduced in strength, the remnants of the division reached the beaches for embarkation next day.(2)

Orders to retire on the night of the 28th did not reach the commander of the Cassel garrison till six in the morning of the 29th. By then the town was surrounded and German forces had penetrated deeply on either flank. It was impossible to move out in daylight, and when a little later wireless communication with 48th Divisional Headquarters was re-established, orders were received to hold Cassel till nightfall and then to withdraw. All through the day Cassel was heavily bombarded and at intervals attacks by tanks and infantry were repulsed. In adjacent country patrols sent out by the 1st East Riding Yeomanry met the enemy at a number of points and suffered considerable loss in men and vehicles. From the hill-top on which Cassel stands strong German forces of all arms could be seen moving north-east behind the town, and when night fell and the garrison set out, the enemy was across their line of march. The 4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry formed the advanced guard; then came brigade headquarters, artillery and engineers; next the 2nd Gloucestershire; and finally the combined carrier platoons of the two infantry battalions and what was left of the 1st East Riding Yeomanry formed the rear-guard. The move started at nine-thirty and leading troops soon encountered the enemy. When daylight came a series of fights led to a separation of units and as the day wore on many were killed, wounded or surrounded and captured piecemeal.(3) Only a few got through to reach Dunkirk. So ended a stand of great value to the British Expeditionary Force. Cassel occupies a key

position at the junction of five important roads, including the main route, on this flank, to Dunkirk. Its use by the enemy had been blocked throughout these most critical days, and considerable forces had been compelled to concentrate on a fruitless effort to take the town. By occupying substantial numbers of the enemy throughout the 29th the Cassel garrison helped to weaken his attack on the flank of the army moving back to the coast.

For the planned movements were duly carried out, though other units which constituted the rear-guard also had a hard day’s fighting to make this possible. The elements of the 50th and 3rd Divisions on the Poperinghe–Lizerne line suffered heavily from bombardment throughout the day. The enemy regained contact with the 50th Division rear-guard by midday, and when later the time for withdrawal came, one company of the 8th Durham Light Infantry was cut off. The 3rd Division’s rear-guard on their left (the 8th and 9th Brigades) was vigorously attacked and some units were forced to yield ground. But the enemy made no substantial progress, though fighting continued till the time for further withdrawal, and then the 2nd Lincolnshire carriers had to counter-attack in order to free the battalion.(4) All units suffered severely in the day’s fighting, but their front was unbroken.

Meanwhile the western flank-guard was also hard pressed. Troops of the 48th and 42nd Divisions in the area Bergues, Quaedypre, Wylder, Bambecque, were attacked by tanks and by infantry of the 20th Motorised Division, the motorised Grossdeutschland Regiment and the S.S. Adolf Hitler Regiment.(5) There were inevitably considerable gaps between the places occupied, and although the latter were held till the time ordered for withdrawal, the enemy mad deep penetrations between them and there was much confused fighting. Brigadier Norman’s force of the 1st Light Armoured Reconnaissance Brigade and the 1st Welsh Guards held off a sustained attack till ordered to withdraw. The 8th Worcestershire on the Yser between Wylder and Bambecque also had a perilous day. Deep penetrations had been made on both flanks of the position they held, and after losing heavily they were forced to give some ground.(6) But the enemy was unable to break their resistance and at night they succeeded in withdrawing in accordance with their orders.

Behind the western sector of the upper Yser advanced elements of the German forces reached positions held by the 42nd Division at Rexpoede and Oost Cappel towards evening, but withdrawal, when the time came, was achieved successfully; and on the rest of the Yser line what remained of the 5th Division was not seriously attacked and withdrew to the perimeter in the night. The fighting of the last few days had sadly exhausted its strength. Many of its

battalions, and those of the 143rd Brigade which had fought with it, were reduced by now to the strength of one or two companies. Of the carriers of the 17th Brigade, only six were left. In the 13th Brigade, the 2nd Sherwood Foresters mustered only 156 of all ranks.(7) Battle casualties accounted for most of the losses, but the difficulties of the withdrawal added something to the total. The inevitable difficulties had been immensely increased by the fact that the French Command had been unwilling to coordinate road movements in the final stages or to collaborate in maintaining road discipline. The roads became choked by French and British troops moving on the same routes under differing orders, in motorised and horse-drawn transport and on foot—the British aiming at the eastern and the French at the western sector of the bridgehead, so that their paths crossed. Units were all too easily separated in the turgid stream of traffic, moving often in darkness and sometimes under shellfire. and, though many of these detached parties eventually reached the beaches, their absence while the rear-guard fighting lasted increased the difficulties of those who fought.

The situation maps for these days show how greatly superior in numbers were the German forces which sought to defeat the retiring army. Yet nowhere during the whole withdrawal were they able to make a clean break in our defence; nowhere could they overcome the resistance of rear-guards which stood their ground till they were either destroyed by weight of numbers or ordered to retire. The line of defence had been perilously weak, but the fighting spirit had been too strong for the enemy to break, and now his opportunity was lost.

Many of the British Expeditionary Force had already sailed for England and during the coming night and the following morning the remainder entered the Dunkirk bridgehead; there the journeying of the divisions which had marched so often and so far was practically completed.

The stubbornness of the British resistance by day and the speed of their withdrawal by night had combined to frustrate German plans. On this 29th of May Army Group B War Diary states that three divisions were being moved rapidly westward to join forces with Kleists’s armour at Poperinghe, and from there to wheel against the British flank on the Poeringhe–Lizerne line. During the afternoon the German Sixth Army reported that this wheeling movement had begun ‘in order to cut off the enemy from Poperinghe’ but, as already told, the troops on the Poperinghe–Lizerne line withdrew before the enemy could intercept them. The pincers closed not round the British Expeditionary Force but behind it. Yet the German Diary also states that ‘the attack designed to annihilate the enemy forces still encircled in the area south and south-east of Dunkirk will be

continued with the greatest vigour. An order to this effect is again issued by the Army Group Command.’1

During the morning the enemy had indeed reached the canal on the eastern outskirts of Furnes and the town itself was heavily bombed and mortared. The Germans were in close contact now on the west near Bergues and on the east from Nieuport to the sea, but all their attempts to cross the canal at Bergues were frustrated and they were prevented from enlarging their small hold in Nieuport. With the relief of the improved defence that night by the 4th Division and with the arrival of II Corps, Sir Ronald Adam’s task was completed and he sailed for home next morning.(9)

Lord Gort’s headquarters had arrived at La Panne on the afternoon of the 28th and an order was issued laying down the order of evacuation. III Corps were to go first; II Corps second. I Corps was to have the honour of acting as rear-guard.(10) For belief that perhaps 45,000 troops might be got away had given place to a growing hope that the greater part of the British Expeditionary Force could be evacuated. And in consequence the Navy’s task expanded from the swift evacuation of a part to a sustained attempt to bring the whole force home.

A heartening message was received by Lord Gort from His Majesty the King:

All your countrymen have been following with pride and admiration the courageous resistance of the British Expeditionary Force during the continuous fighting of the last fortnight. Placed by circumstances outside their control in a position of extreme difficulty, they are displaying a gallantry that has never been surpassed in the annals of the British Army. The hearts of every one of us at home are with you and your magnificent troops in this hour of peril.(11)

The message was at once issued to the troops , and Lord Gort replied:

The Commander-in-Chief with humble duty begs leave on behalf of all ranks of the BEF to thank Your Majesty for your message. May I assure Your Majesty that the Army is doing all in its power to live up to its proud tradition and is immensely encouraged at this critical moment by the words of Your Majesty’s telegram.(12)

Late in the evening the Commander-in-Chief received the following personal message from the Prime Minister:

… If you are cut from all communications from us and all evacuation from Dunkirk and beaches had in your judgement been finally prevented after every attempt to reopen it had failed, you would become the sole judge of when it was impossible to inflict further damage upon the enemy. H.M.G. are sure that the repute of the British Army is safe in your hands.(13)

On this afternoon, three days after the British Government’s decision to evacuate as many as possible of the British Expeditionary Force had been notified to the French High Command, General Weygand authorised the evacuation of as many as possible of the French First Army.(14) ‘Operation Dynamo’ had been in progress since the 26th, and over 70,000 British troops had been embarked before the French commander’s decision was taken. Large number of French troops were by then reaching the coast. Four French torpedo boats and two of their mine-sweepers arrived to help with the embarkation of French troops and more of their ships followed in succeeding days.(15)

Organisation on the beaches was being strengthened and improved and the concentration of warships and other vessels was nearing its peak. Their very names conjure up a vision of the assembling fleet of warships, merchantmen, liners and fishing craft, of tugs and lifeboats, barges, sailing yachts and launches. The great and the small were joined in common effort. The Royal Sovereign was there and the Emperor of India and there were several Queens; the Princess Elizabeth and the Princess Maud were there, with the Duchess of Fife, Lord Howard and Lord Howe, the famous Gracie Fields and obscure Polly Johnson. Our Bairns and The Boys were there with Girl Pamela and a Yorkshire Lass. Many towns took part from Canterbury to Bideford, from Worcester to Dundalk, and footballers were represented by Blackburn Rovers and the Spurs. Wakeful, Gallant and Intrepid were there to typify the spirit of them all and, as emblems of the freedom they toiled for and the hope that inspired them, there was a Golden Gift and a Silver Dawn.(16)

But the enemy’s attempt to disrupt operations also increased and the Navy only carried on by facing graver risks and by paying a high price for their achievement. The ships had already braved the fire of land-based guns, bombing and machine-gunning from the air the the hidden menace of magnetic mines. This day began with the revelation of further dangers on the passage to and from the French coast.

A little before midnight the destroyer Wakeful, carrying 650 troops embarked from the beach at Bray, sailed for Dover by the northerly route Y. She had just cleared the North Channel and turned sharply to westward when two torpedo tracks were seen. One torpedo was avoided but the other hit amidships. The Wakeful was broken in half by the explosion; the two halves sank in a few seconds, settling with their midships sections on the shallow bottom while bow and stern projected high above the surface. The troops on board, asleep below, went down with the ship and only a few and the crew on deck floated clear.

Soon after, the drifters Comfort and Nautilus, en route for La Panne,

reached the scene of disaster and started to pick up survivors; later the mine-sweeper Gossamer, bring 420 troops from Dunkirk, joined in the rescue. Then the destroyer Grafton arrived with 800 troops on board and the drifter Lydd came with 300 on their way to England. They too lowered boats to look for survivors from the Wakeful. Two hours had elapsed since the torpedo attack but it was still very dark. A small unlighted vessel was thought by the Grafton to be another drifter and she was signalled to join the search. Within a few seconds the Grafton was torpedoed.

The Comfort, lying nearby, was almost swamped by the force of the explosion and the Captain of the Wakeful, whom she had rescued from the sea, was again washed overboard. Although sinking, the Grafton opened fire on a vessel which in the darkness she took to be an enemy torpedo boat and following the Grafton’s example the Lydd rammed and sank this dimly seen vessel. But in fact it was the Comfort moving in the darkness; only one of her crew and four of the men shed had rescued from the Wakeful were saved. It became known later that the Grafton was sunk by the enemy submarine U-69.

The 800 troops on board the Grafton, some seriously wounded, were taken off by the passenger ship Malines returning from Dunkirk, and before the Grafton went down she sighted an enemy vessel and sank her by gunfire. The Captain of the Wakeful, for the second time was picked up, swimming, five hours after his own ship had been hit.(17) But then it was at last light.

There were other misfortunes on this day. The destroyers Montrose and Mackay were damaged by collision and grounding and the passenger ship Mona’s Queen blew up on one of the magnetic mines which enemy aircraft were now sowing in the approaches to Dover and Dunkirk. Only one other ship was destroyed by this means during the evacuation.(18)

But it was the enemy’s bombing that caused the heaviest damage. The scale on which evacuation was proceeding had been reported by their air reconnaissance formations and ‘the bulk of the German bomber forces were employed to prevent the enemy achieving this and to annihilate him in his present state of collapse’ (sic). In the afternoon ‘the full force of the air attacks was directed against the numerous merchant vessels in the adjacent sea and the warships escorting them’.2(19) The German air fleet cooperating with Army Group A and Army Group B were both employed. Between midday and eight o’clock at night there was hardly a break in the attack and five times it reached major proportions with large concentrations of both bombers and fighters. On two of these occasions our fighter patrols were not at the time over the area: on the

remaining three the enemy were intercepted—once before, once during, and once after their main attack. Our patrols had been doubled in size since their unequal battles of the day before, but intervals between patrols were correspondingly longer and they found that with patrols numbering from twenty-five to forty-four aircraft they were still often outnumbered. On more than one occasion they were wholly engaged with enemy fighters and could not reach the bombers. Sixteen squadrons fought this day. Nineteen fighters were lost and though the squadrons claimed to have brought down a large number of enemy aircraft the Luftwaffe’s reported that day only admitted the loss of eighteen; on the other hand it claimed (mistakenly) to have shot down sixty-eight of our aircraft!(20)

It must always be difficult if not impossible to assess and apportion an enemy’s air losses accurately. More than one aircraft engaged may with good reason claim credit for a kill, and throughout Operation Dynamo anti-aircraft artillery on land and fire from ships in harbour and at sea accounted for some of the enemy destroyed. but losses are not the true criteria by which achievement in action should be measured. The enemy’s attacks this day could not be prevented, for he had far larger forces than the squadrons who fought him. But his attacks were so far interfered with and broken up that he failed in his intention. He could neither weaken the Army’s defences nor stop the Navy’s operations. The fact that he was prevented from realising his aim is the best proof of what the Royal Air Force achieved.

While some who suffered from the enemy bombing complained that our air cover was inadequate, both the Army and the Navy acknowledged gratefully the help they had received. The Army fighting its way to the coast was largely freed from air attack and reported ‘little bombing today’; and the Vice-Admiral Dover signalled Fighter Command: ‘Reports from Senior Naval Officer state your assistance has been invaluable. I am most grateful for your splendid cooperation. It alone has given us a change of success …’(21) This generous message showed an appreciation of the part played by the Royal Air Force which might well have been warped by the day’s happenings.

For the Navy had endured great losses with a fortitude which the enemy’s fury could not shake. The early-morning misfortune has been told to illustrate the dangers faced in darkness and at sea. The even greater danger which ships faced in harbour and in daylight may be illustrated by what happened on this afternoon.

Men who came home from Dunkirk remember most vividly the beaches (if they embarked there), or, if they came from the harbour, the long, narrow, eastern mole, jutting out for 1,600 yards, naked of all defence. It was built as a breakwater, not to provide berthing for

ships, but it was the easiest place for ships to reach and leave and, in order to speed up the pace of evacuation, the Navy continued to use it throughout these operations though it was cruelly exposed. It was often hit but gaps in its planked footway were soon repaired and tens of thousands came home that way.

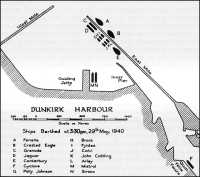

On this afternoon two destroyers, the Grenade and the Jaguar, were laying against the inner side of the mole. Six trawlers were berthed behind them, and the passenger ship Canterbury. Against the outer side of the mole at the same time were the passenger ships Fenella and the Crested Eagle.(22) Their positions are shown on the adjoining sketch.

Dunkirk Harbour

The enemy’s on slaughter from the air began at about half past three in the afternoon and continued until about eight o’clock, rising in a crescendo four times. Of the eleven British ships against the mole the Grenade, Fenella, Crested Eagle, Polly Johnson and Calvi were so damaged that they sank at once or shortly afterwards; the Jaguar and Canterbury, though they reached home, could take no more part in Dynamo. At six o’clock that night the harbour was only occupied by burning and sinking ships. A report reached Admiral Ramsay by burning and sinking ships. A report reached Admiral Ramsay that the entrance was blocked and for a time all ships were directed

to the beaches.(23) But it was a mistaken report, for by strenuous effort all sinking ships had been moved from the fairway.

Meanwhile, equally sustained attacks had been made on the shipping off the beaches and, as evacuation continued in spite of it, losses were heavy. The destroyers Gallant, Greyhound, Intrepid and Saladin and the sloop Bideford were all badly damaged. The passenger ships Normania and Lorina were sunk. The merchantman Clan Macalister, which had carried across from England eight assault landing craft, and the armed boarding vessel King Orry were sunk and many smaller vessels were sunk or damaged.(24) The story of one must serve to illustrate the off-shore conditions under which they worked.

The paddle-minesweeper Gracie Fields, carrying about 750 troops from La Panne beach, was hit amidships by a bomb soon after starting home. Her upper deck was enveloped in clouds of steam; her engine could not be stopped and as her rudder was jammed at an angle she continued to circle at about six knots. Two schuyts nevertheless mad fast alongside and took off as many troops as they could carry. Then the minesweeper Pangbourne arrived. While embarking troops off Bray beach she had already been hold on both side by near misses and thirteen men had been killed and eleven wounded: and her compass had been put out of action. But she went alongside the Gracie Fields and took off a further eighty troops. Then led by another returning vessel, she took the Gracie Fields in tow and started again for England. In the darkness of early morning the Gracie Fields began to sink, so the Pangbourne slipped the tow and took off her crew. There she was abandoned, but her crew and the troops they had brought from the beaches reached England safely in the ships that had gone to her aid.

If the previous records of this day be compared with those of the previous days, three facts stand out clearly. More ships and small craft were in action; they were exposed to heavier bombing attacks and they suffered greater losses: yet they brought away a much larger number of men. This is the measure of the day’s achievement—47,310 men were landed in England by midnight and many more were on their way across the sea.(25)

Situation on the evening of 30th May, 1940

e